Introduction

The text edited in this paper (IM 183624)Footnote 1 was acquired by the Iraq Museum in 2002.Footnote 2 This fragment, from the large incantation series Udug-hul = Utukkū Lemnūtu (meaning “Evil Demons”) measures (7.2 × 6–7.5 × 1 cm) and originally belonged to a much larger tablet. The fragment represents the end of the second column and a very small part from the third column.

Fig. 1 Reconstruction of fragment's position on original tablet.

This text is the only fragment from Udug-hul Tablet 3 to be found in the Iraq Museum until now.Footnote 3 Duplicates in the British Museum (K 224+; K 4665+; BM 38594; BM 47852; BM 35611+) were previously published (CT 16, plates 1–8), with new copies and an edition and translation by M. J. Geller.Footnote 4 The text is dated to the Late Babylonian period, judging from the sign forms, but there is no possibility of a join with published tablets.

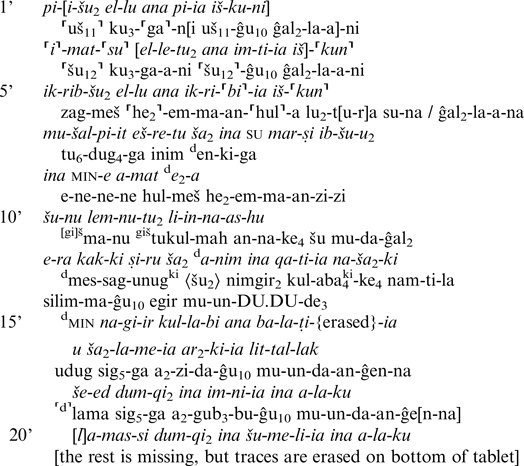

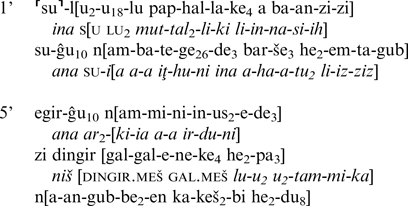

Transliteration of IM 183624

Coll. ii (Udug-hul 3 ll. 60–69)

Coll. iii (Udug-hul 3 ll. 94–98)

Translation

Coll. ii = lines 60–69

- 1’

[He (Ea) superimposed his pure] mouth [upon mine],

- 2’–3’

he superimposed [his pure] spittle [upon mine],

- 4’–5’

he superimposed his pure prayer upon mine.

- 6’–7’

Since a (demon) attacking limbs is (already) in the patient's body,

- 8’–

through an effective incantation – the word of Ea –

- 9’–10’

may those evil ones be uprooted.

- 11’–12’

I hold Anu's exalted e'ru-wood scepter in my hand.

- 13’–16’

May Mes-sanga-unug, Kullab's herald, go behind me for my own health and well-being.

- 17’–18’

In order for the good spirit to go on my right,

- 19’–20’

and for the good genius to go on my left,

Coll. iii = lines 94–98

- 1’–2’

[(May the demons) be removed from the distraught] man's body.

- 3’–4’

[May they not approach] my body [(as well) but stand aside]

- 5’–6’

[nor may they follow] behind me.

- 7’–8’

[I adjure you by] the great gods [that you may go away].

- 9’

[May they not be detained but let their bond be broken!].

Commentary

Col. ii

4’. The signs are clearer on the copy than on the photograph, which shows considerable damage to the surface of this line.

6’. Geller Reference Geller2016: 103, l. 63, should read zag-meš (not zag.meš).

9’–10’. This new manuscript deviates from other duplicates in the verbal form /zi-zi/ corresponding to Akk. nasāhu, in contrast to other variants with more a conventional verb /bu(r)/ in this position. One other manuscript (CBS 13905) has the variant /su3/, which is in a similar phonetic range to /zi/, but all three of these Sumerian forms can correlate with Akk. nasāhu.

11’. Geller Reference Geller2016: 103, l. 65, should read šu-nu (not šu 2-nu).

12’. The reading šu mu-da-ĝal2 (corresponding to ina qa-ti-ia na-ša2-ku) is a variant from the more usual reading, šu-ĝu10 mu-un-da-an-ĝal2 ('I hold in my hand'), but lacking the possessive suffix or dimensional infixes.

14’. Variants to this line all read: egir-ĝu10 DU.DU-de3 // arkiya littallak, “may GN go behind me.” The scribe misunderstands the Sum. as a finite verbal form (mu-un-DU.DU-de3), although the Akk. translation conforms to other duplicates.

Col. iii

4’–5’. The sigla for these lines in Geller Reference Geller2016: 109, ll. 95–96 should read hh and not ii.

Fig. 2 copy of IM 183624 by Munther Ali

Fig. 3 Photo of IM 183624

General comments

This manuscript fragment from Udug-hul, one of the longest and important bilingual incantation series from Mesopotamia, comes from Tablet 3, probably the first tablet of Udug-hul known from Old Babylonian libraries. Since this section may well have been the original beginning of the composition, it deals with the āšipu-incantation priest speaking on his own behalf, in the first person, asking the gods to protect him even before he tries to heal the patient. This may be because of the recognized dangers of visiting a sick person and coming into possible contact with demons, or simply because the exorcist had to first demonstrate that he himself was pure and free of disease or demonic attack, in order to be able to heal someone else. In order to do this, the exorcist had to claim that he was the representative of the gods of exorcism, Ea and Marduk, and that he was sent by them, so that whatever spells the exorcist recited were actually coming from the gods, rather than from himself.Footnote 5 For this reason, according to our tablet, the healing god had placed his mouth, spittle and words into the exorcist's mouth, so that whatever incantation the āšipu recited came directly from healing gods. The question is how unusual or exceptional this may be, since other incantations occasionally use a formulaic expression, kīam iqabbi, “he should say thus,” meaning that the client rather than the exorcist should recite the incantation.Footnote 6 In this tablet of Udug-hul, however, it seems that the exorcist is speaking rather than the patient.

The question is whether one finds any parallels in other incantations, and the obvious place to look is Maqlû, the text of which has recently been published by Tzvi AbuschFootnote 7 and Daniel Schwemer.Footnote 8 Maqlû incantations are predominantly in the first person, but who is speaking, the exorcist or patient? According to Abusch, the speaker is not an āšipu but actually “a member of the laity, not a priest”, who acts as if he is a messenger of the gods and claims to be so.Footnote 9 Here is a sample text of the speaker in Maqlû I 61:

Incantation. I have been sent and I will go; I have been commissioned and I will speak. Asalluhi, lord of exorcism, has sent me against my warlock and witch. (Translation T. Abusch).

The incantation goes on to explain that the witches have “seized my mouth, made my neck tremble, pressed against my chest, bent my spine, weakened my heart, taken away my sexual drive, made me turn anger against myself, sapped my strength” (Maqlû I 97–100, translation Abusch). Abusch argues that it is the client or victim who makes these statements, and just as he claims to be suffering from witches, the patient also claims to be sent by Marduk (like an āšipu). Evidence supporting this point of view comes from Old Babylonian Sumerian incantations, known by the rubric ka-inim-ma e-sír-dib-bé-da-kam, “incantations for passing along the street”, and these incantations were collected and copied by scribes together with Old Babylonian Udug-hul incantations, although not incorporated into the late bilingual Udug-hul Series. The passage cited by Abusch follows the well-known ‘Enki-Asalluhi dialogue’, and reads as follows:

It would be correct to surmise that this passage is not unusual, in that the victim who walks along the street at night (always a dangerous thing to do because of demons) has to recite a special incantation, in order to keep the demons away (and probably keep his spirits up). However, it seems that this Esirdibbeda incantation advises the victim to mimic a standard type of incantation, in which he declares that he – the patient – is Enki's emissary, in effect pretending to be an āšipu. This reflects Udug-hul Tablet 3, in which the āšipu speaks directly to the demons and declares, “I hold Anu's exalted e'ru-wood scepter in my hand;”Footnote 11 in other words, claiming that he (the speaker) is a personal representative of the gods. Nevertheless, the logic behind the Esirdibbeda magic is that in order to frighten off the demons at night, the victim should recite this type of incantation as if he were an incantation priest and had the power to chase away demons. This deviates from Udug-hul incantations normally meant to be recited by the āšipu in order to protect himself, when he goes to see the patient or victim; healing can be dangerous, just as was walking in the streets at night.Footnote 12

This brings us back to the question of Maqlû incantations and who was reciting them. Who is “I” in these incantations? This question is similar to the problem of identifying the “you” addressed in medical recipes, when the text says, “you take, you grind up, you crush”, etc. We assume this “you” to refer to the professional healer, the asû, and not the patient himself, and by analogy the “I” in Maqlû incantations could potentially refer to the professional healer, in this case the āšipu.

There is some evidence in Maqlû incantations to support the idea that it is the āšipu himself who is to be identified with the speaker. In Maqlû Tablet 2, 170–171 we find an interesting variant. The text reads:

anāku ina qibīt dmarduk bēl nubatti u dasalluhi bēl āšipūti Footnote 13

I (am) under the command of Marduk, lord of the evening offering, and Asalluhi lord of exorcism.

One significant variant manuscript from Aššur (VAT 10009 = KAL 4 No. 26) inserts a proper name, reading:

ana-ku maš-šur-šá-liṭ ina qí-bit dAMAR.UTU …

I, Mr. Assur-šāliţ, am under the command of Marduk ….

This is surprising, since Maqlû incantations do not normally refer to specific individuals by name, and this personal reference contrasts with the standard pattern of three other manuscripts from Nineveh and Sultantepe (K 24555+, K 2947+, SU 52/38). Two other intriguing references to this same Aššur-šāliṭ appear in the same Maqlû Tablet 2 manuscript (VAT 10009). The first mention occurs in an incantation to Girra, god of the torch, which has the incipit, én dgirra āriru bukur danim, “Spell. Blazing Girra, first born of Anu”.Footnote 14 After praising this god as capable of countering the effects of witchcraft, incantation soon introduces the intended object of the witchcraft:Footnote 15

anāku [annanna mār annan]na ša ilšu annanna dištaršu annannītu Footnote 16

I am [N.N. son of] N.N., whose personal god is N.N., whose personal goddess is N.N.

At first glance, this looks like the standard designation of a victim or patient, since it follows the pattern found in Udug-hul incantations, which refer to the patient as lu2-ulu3 dumu dingir-ra-na / amēlu mār ilišu, “a man son of his god”.Footnote 17 However, the same Aššur manuscript of Maqlû (VAT 10009) varies the text of the entire line as follows:

anāku mAššuršāliṭ mār ilišu dNabû ša ištaršu dTašmētu Footnote 18

I am Aššur-šālit, whose personal god is Nabû, whose personal goddess is Tašmētu.

The same manuscript again takes the opportunity to identify the first-person protagonist as Mr. Aššur-šāliṭ, further giving the names of his personal or favoured god and goddess, rather than the general designation of being “man son of his god”.

An intrusion occurs once more in Maqlû Tablet 2, 98–100, in a passage which reads:

dGirra šarḫu ṣīru ša ilī / kāšid lemni u ayyābi kušussunūtima anāku (var. maššur-šāliṭ) lā aḫḫabbil / anāku aradka lubluṭ lušlimma maḫarka luzziz Footnote 19

Resplendent Girra, august among the gods, vanquisher of evil and enemies, vanquish them that I (var. Aššur-šāliṭ) not come to harm that I, your servant, should live and be safe and stand before you.

The Aššur scribe of VAT 10009 has again inserted the name Aššur-šāliṭ into the text of l. 99, after anāku, “I”, in the standard edition.

The pressing question, then, is who this Mr. Assur-šāliţ is likely to be. One possibility is that he would be a client or patient, since we know that such persons can be referred to in other witchcraft incantations by a general designation of “N.N. son of N.N.” (annanna mār annanna). The second question is why this particular scribe would insert a proper name into the text. Was this manuscript of Maqlû Tablet 2 personalized for some reason, in contrast to all other manuscripts of Maqlû which are known to us? An alternative possibility is that whoever wrote this Aššur tablet (probably an āšipu) took the initiative to insert his own name, to afford himself the protection offered by the relevant incantations.

If this were the only case of a personal name being inserted in place of the usual anonymous reference to ‘N.N. son of N.N.’, there would be little grounds for choosing between the two options, i.e. the proper name designating either the patient or the scribe. Fortunately, there are several other cases, exclusively from Aššur, of personal names being inserted into a similar genre of incantation-prayers, and these offer precise comparisons with the inserted name Aššur-šāliṭ in Maqlû Tablet 2. The first of these insertions in another Aššur manuscript is found in a Šuilla prayer to Nabû (CMAwR 2 No. 9.7: 14),Footnote 20 which has the same structure as many other Šuilla texts.Footnote 21 The prayer offers praise to Nabû, ending with the pious wish, liktarrabāka gimir tenēšēti, ‘may all the population keep praying to you' (l. 13). The following line (14), based on a Nineveh manuscript from Assurbanipal's Library (K 6644), reads:

[anāku annanna mār] annanna ša ilšu annanna ištaršu annannītu Footnote 22

I am N.N. son of N.N., whose personal god is N.N. and personal goddess is N.N.

Crucially, one Assur duplicate (A 138 = LKA 40a) has a variant reading for this entire line, which corresponds verbatim (except for the proper name) to Maqlû II 86 cited above:

ana-ku mba-la-si dumu dingir-šu 2 ša 2 dingir-šu 2 dpa d15-šu 2 d⸢papnun⸣

I am Balassi son of his god, whose god is Nabû, whose goddess is Tašmētu

The correspondence between this phrase and Maqlû II 86 can hardly be coincidental, especially since the proper name is again associated with the god Nabû and his spouse Tašmētu. The fact that Nabû was a patron god of scribal arts lends credence to the suggestion that the proper name inserted here, Balassi, refers to an Assur āšipu or scribe who actually wrote this tablet (A 138). Abusch and Schwemer comment on Balassi, that since several Aššur individuals are known by this name, we cannot be certain of the identity of this person.Footnote 23 It is true that Balassi was popular at Aššur. Nevertheless, among the references to the name Balassi at Aššur associated with various professions (see PNA I / II 254–256), there are also clear references to a court ummānu and astrologer by this name, which raises the possibility that the name could refer to the scribe who copied this Maqlû tablet. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the Aššur tablet containing Balassi's name (A 138) was found in Aššur's Haus des Beschwörungs priesters,Footnote 24 which might be relevant information, as we will see shortly.

This is not the only case in which the proper name Balassi is inserted into a Šuilla prayer, but this second case is more difficult to track down, since key information has been omitted from the edition of the text. The prayer is addressed to Marduk's spouse Zarpanitu, first edited in 1896 (BMS 9 rev.),Footnote 25 with a partial duplicate published later from Aššur (VAT 13487 = LKA 48).Footnote 26 The Assur manuscript includes lines of text not found in BMS 9, which contain the following reference on the reverse of the tablet (cf. Ebeling Reference Ebeling1953: 72a: line 11) now possible to reconstructed fully, based on parallels:

[ana-ku m]ba-la-si a dingir-šu 2 š[a 2! dingir-šu 2 dpa d15-šú dpapnun]

[I am] Balasi son of his god, [whose personal god is Nabû, whose personal goddess is Tašmētu].

Confirmation of this restoration can be found on the obverse of this same tablet, which duplicates the Nineveh manuscripts edited in BMS 9, although two relevant lines were omitted in Ebeling's edition of the tablet (1953: 68), which can be seen clearly on LKA 48 obv. 8–9.Footnote 27 The lines read:

[ana-ku m]ba-la-si dumu dingir-šu 2 [ša 2 dingir-šu 2 d]pa d15-šu 2 dpapnun

[I am] Balassi son of his personal god, [whose personal god] is Nabû, whose personal goddess is Tašmētu.

Once again, it appears that a Šuilla prayer has inserted a proper name into the text which cannot be found in the Nineveh duplicate. Moreover, this Aššur manuscript (like others cited above) was found in the Haus des Beschwörungspriesters in Aššur.Footnote 28

A similar case of intrusion of a personal name in an Aššur manuscript occurs in a Šuilla prayer to Nuska,Footnote 29 the god who lights up the night with his lamp, thematically resembling the God Girra and his torch in Maqlû Tablet 2. The same pattern appears among the four known manuscripts of this prayer, two from Nineveh and two from Aššur, namely that a proper name appears in an Aššur duplicate in place of the usual reference to “Somebody son of Somebody” at Nineveh. The relevant lines occur in a prayer with the incipit, én dnuska šurbû ilitti Duranki, “Sublime Nuska, offspring of Duranki”.Footnote 30 The first seven lines of this prayer praise Nuska as beloved of Enlil, without whom Anu and Enlil cannot offer proper advice.Footnote 31 The petition to the god which follows this section begins with the standard formulation, attested in two manuscripts from Nineveh and one from Aššur:Footnote 32

anāku annanna mār annanna ša ilšu annanna dištaršu annannītu Footnote 33

I am N.N. son of N.N., whose personal god is N.N., whose personal goddess is N.N.

However, a second Aššur manuscript (VAT 13632) inserts several new lines into this section, beginning with a variant for the above passage reading:

anāku Aššur-mudammiq mār ilišu [ša] ilšu Nabû ištaršu Tašmētu Footnote 34

I am Aššur-mudammiq son of his god, whose personal god is Nabû, whose personal goddess is Tašmētu

Again, the personal name – this time Mr. Aššur-mudammiq – replaces the usual formulaic expression, but with a difference. The colophon of this Aššur tablet adds the important detail that the tablet was written on the 19th day of Ayyār, done at night-time, by Mr. Aššur-mudammiq himself.Footnote 35 This is the first known case that the name inserted into the text matches the name of the tablet's scribe, reinforcing the idea that the scribe sought the protection of the incantation-prayer for himself, and that he was identical with the suffering client or patient referred to in the text. Moreover, we are relatively well informed about Mr. Aššur-mudammiq's career. His father, Mr. Nabû-mušēṣi, was known as a scribe of the Aššur Temple,Footnote 36 as was his grandfather and other members of his family.Footnote 37 His son Nabû-eṭiranni was mentioned as being an apprentice exorcist,Footnote 38 and it is likely that Aššur-mudammiq was himself an āšipu, which was why he wrote the tablet incorporating his name.Footnote 39 Moreover, as in the other examples cited above, the Aššur tablet with Aššur-mudammiq's name (VAT 13632) was also found in the Haus des Beschwörungspriesters.Footnote 40 Finally, Mr. Aššur-mudammiq's name appears in the colophon of a mukallimtu astrological commentary (K 872), probably written in Assur but found in Nineveh, now edited by the Yale Cuneiform Commentaries Project, CCP 3.1.u83 (see https://ccp.yale.edu/P393842).

The obvious inference to be drawn from this evidence is that all these manuscripts from Aššur, containing Maqlû or Šuilla incantation-prayers, reflect the exclusive practice of Aššur scribes to insert their own names into a text where one usually finds reference to “Somebody son of Somebody”. The personal names inserted follow the same pattern in all cases: proper names have no patronymic but take the traditional form known from Udug-hul incantations, designating the prospective client as “man son of his god” (lu2-ulu3 dumu dingir-ra-na). Furthermore, all cases from Aššur associate the proper names with the god and goddess Nabû and Tašmētu, suitable patron gods for scribes. The likelihood, therefore is that in all cases cited above, the names inserted into the text also identify the scribe who copied the tablet.Footnote 41

What justification would there be for a scribe or an āšipu to do this? The unique character of Maqlû is that this was actually a ceremony to be performed on a certain night of the year, according to Abusch.Footnote 42 If this is the case, who would be performing this ceremony? Would it be the patient, as Abusch believes, acting like an āšipu, or would it be the incantation-priest himself, reciting the Maqlû incantations, e.g. Mr. Aššur-šāliţ, Mr. Balassi, or Mr. Aššur-mudammiq? And if the latter, why would the incantation-priest claim to be bewitched and behexed and troubled by demons?

The answer may be quite straightforward. In a Maqlû-like ceremony, the priest recites prayers – even for himself – which are also meant for anyone present who is listening. An incantation-priest, like everyone else, is just as likely to get ill or be attacked by demons, or even be behexed by a witch. Like in Udug-hul incantations, the āšipu had to protect himself in the same way that he protects his patients. So it seems more likely that Maqlû incantations were not recited by a patient acting like a messenger of the gods, but rather by the āšipu himself, with his own personal worries and troubles, including fear of witchcraft. In fact, as we know from Udug-hul incantations, the usual role of the incantation-priest acting in a ceremonial capacity was first to recite the incantations on behalf of himself and by extension for anyone else also present.Footnote 43

We can find other later evidence to support the idea that the speaker in magical texts may have been the exorcist rather than the patient. Interesting parallels can be found in later Syriac incantation bowls from Mesopotamia, which frequently refer to someone ‘speaking’ in these spells in the first person. The client is usually mentioned by name as the object of the demonic attack, but in the course of his duty to protect the client, the exorcist speaks directly to the demons in the first person. Here are a few citations from Syriac bowls (published by M. Moriggi, with bowl citations): “I am speaking” (ʾn’ ‘mrn’, no. 22.4) or “I declare” (ʾn’ qryn’, no. 14: 24), or “I will show you” (lkwn mhwyn’ no. 10.6), and to remove any doubt, in one case the bowl reads, “I wrote (it) but God heals” (ʾn’ ktbty ʾlh’ nʾs’, no. 28: 13).Footnote 44 In these spells, the speaker is none other than the writer or performer of the incantation, not the client mentioned in the bowls.

In conclusion, this small fragment of a tablet from the Iraq Museum raises interesting questions, simply by making us think about the larger framework into which this tablet fits. The idea that the incantation priest himself is subject to possible attack by demons is of central importance, since he must protect and heal himself before he can do so for others. This means that the incantation priest himself was not thought of as blameless or perfect or even worthy to act on behalf of others, and therefore he was entitled to ask for the same protection and divine favor as for his clients. But the āšipu had an advantage over ordinary individuals, since he knew the rituals and the incantations and he could act as Marduk's messenger, because of his priestly status and training. It is likely, therefore, that just as Udug-hul incantations began with a request to protect the āšipu who was reciting the text, in a similar way the speaker of Maqlû incantations was this very same āšipu, who was now acting out his role as messenger of the gods, on his own behalf and on behalf of everyone else who may have been present at the Maqlû ceremony.

Acknowledgements

Munther Ali would like to thank Prof. Dr. Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum for hosting several research visits to the Institut für Altorientalistik of the Freie Universität, Berlin, and to the Topoi Excellence Cluster for financial support for these visits, and to Prof. Dr. Stefan Maul for advice and help. The authors would like to thank Dr. Ahmed Kamel Muhammed for allowing access to this text and for permission to publish it, and to thank Mark Weeden for editing and corrections.