President Woodrow Wilson idealized the concept of self-government and believed that individuals had an inherent right to direct public affairs. To make it possible for everyday citizens to hold government accountable, he highlighted the importance of the free flow of information on the one hand, and the corrupting influence of secrecy on the other: “Publicity is one of the purifying elements of politics… Nothing checks all the bad practices of politics like public exposure” (Wilson Reference Wilson1913, 115–116). Transparency is a social good for effective democratic governance. One way for the public to exercise their right-to-know is by petitioning the government to release specific public records through open records laws. These laws exist at all levels of government to enable citizens, interest groups, and members of the media to gain access to information which otherwise would not be in the public light.

Open records requests have played an essential role in citizens’ ability to gain information with which to hold elected officials accountable. In recent years, local government officials have faced legal battles about their reluctance to release emails deemed in the public’s interest. For example, the City of Chicago has fought to keep email communication between the mayor and others out of the public’s eye. Only after a court order did the City release emails depicting a potentially problematic relationship between the mayor and requests for city services by big political donors (Felsenthal Reference Felsenthal2016). New York City’s mayor has also been embroiled in an open records request controversy. Emails by Mayor Bill de Blasio gave the public an inside look into the debates on funding public projects and the management style of a leader who controls one of the largest local bureaucracies in the country (Goodman and Mays Reference Goodman and Mays2018).

Mayoral offices are a perfect setting to test the theories of social pressure and responsiveness. Mayors lead local bureaucracies that oversee a full range of public services from zoning restrictions to trash-pickup to authorizing business licenses. These offices are tasked with being responsive under budget and time constraints. Two sequential steps exist under open records laws: (1) respond to the request and (2) comply with the request. I study the first stage in this process. Mayors and their offices have a considerable amount of discretion (legal or extra-legal) in the extent to which they are responsive to requests. Footnote 1 Knowing this, I ask: can priming social pressures improve responsiveness? Footnote 2

To explore this question, I conduct a large-scale non-deceptive correspondence experiment requesting 3 months of non-private government emails from more than 1400 mayors in 50 U.S. states. In the emails, I attempt to blend institutional motivations for mayoral responsiveness with messages traditionally developed by behavioralists. I examine two theories of social pressure: (1) the norm of transparency and the duty of elites to be responsive to the public, and (2) peer effects through accountability. The first prime builds on previous work which indicates that elected officials and their bureaucrats have built-in norms to respond to the public’s wishes (Key Reference Key1961; Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974; Saltzstein Reference Saltzstein1992). The message is crafted to acknowledge a norm of transparency and the fact that the public believes the local government has not met expectations. Thus, I hypothesize that priming the duty to respond to a request for transparency will increase responsiveness to such requests. The second prime incorporates the idea of peer effects as a social norm that elected officials, like ordinary individuals, change their behavior in the presence of peer expectations (Gerber, Green, and Larimer Reference Gerber, Green and Larimer2008; March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1989, Reference March and Olsen1995; Scott Reference Scott and Dowdle2006). I expect that notifying mayors that their peers received the same request and that a report will be sent to them will induce responsiveness through the potential for “naming and shaming.”

Analyzing the 729 replies, I find that mayors do not respond in differential ways to messages about their duty. Contrary to expectations, I find that peer effects decrease the likelihood of receiving a response, which suggests a “backfire effect.” This paper contributes to the growing literature on local government responsiveness and improves our understandings of the potential disadvantages of peer effects.

Theories of responsiveness to open records requests

Sunshine laws were created to foster a mechanism through which citizens could hold public officials accountable. If these laws were effective, there should be no variation in responsiveness and compliance. Yet, there exists wide variation within and between states on their compliance with open records requests. Scholars have noted that government entities routinely fail to fulfill such requests (Geraghty and Velez Reference Geraghty and Velez2011). Footnote 3

Many researchers have used open records requests as an avenue to answer questions about responsiveness, compliance with laws, and the impact of controversial requests (Ben-Aaron et al. Reference Ben-Aaron, Denny, Desmarais and Wallach2017; Cuillier and Davis Reference Cuillier and Davis2010; Lowande Reference Lowande2018, Reference Lowande2019; Wood and Lewis Reference Wood and Lewis2017). While Ben-Aaron et al. (Reference Ben-Aaron, Denny, Desmarais and Wallach2017) found that local governments are more likely to fulfill open records requests when they know peer governments have also fulfilled similar requests, Cuillier and Davis (Reference Cuillier and Davis2010) found that non-threatening requests were more likely to be fulfilled.

I build on these previous works to examine the extent to which social pressures may induce responsiveness to transparency requests. I lay out two theories that could influence responsiveness. One approach is based on the duty of elected officials to respond to the public’s requests. The other is derived from the idea that peer group monitoring influences behavior.

Responsiveness as a duty to the public

Dahl (Reference Dahl1971) argues that transparency or the free flow of information is a fundamental aspect of democratic regimes. Without it, he suggests, representation can never truly exist. Open records laws establish the norm of transparency at the state and local government levels. Scholars and the general public widely believe that elected officials also have the duty to be responsive to the public’s concerns. Key (Reference Key1961) best articulates this duty: “Governments must concern themselves with the opinions of their citizens” (7). Enforcement among elites may occur in two ways: (1) the electoral incentive, and (2) the internal sense of duty to the public. A sizable literature from scholars of institutions has confirmed that elected officials and bureaucrats indeed follow public opinion (Arnold Reference Arnold1990; Bartels Reference Bartels1991; Guisinger Reference Guisinger2009; Kousser, Lewis, and Masket Reference Kousser, Lewis and Masket2007; Saltzstein Reference Saltzstein1992; Wlezien Reference Wlezien1995).

Beyond electoral accountability, political elites may have an internal sense of duty to respond to the public. Scholarship on voter mobilization has found that informing citizens of their duty or obligation to vote is a potential positive form of social pressure (Gerber, Green, and Larimer Reference Gerber, Green and Larimer2008; Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2008). Reminding mayors that a norm of governmental transparency exists may heighten officials’ awareness of and lead to an increase in responsiveness to open records requests. This scholarship leads to my first hypothesis.

H1 City government executives will be more responsive to requests for transparency when primed with their civic duty to uphold norms of sharing information.

Peer effects

Growing literature by social scientists suggests that political elites can be affected by their peers (Harmon, Fisman, and Kamenica Reference Harmon, Fisman and Kamenica2019; Holden, Keane, and Lilley Reference Holden, Keane and Lilley2019; Masket Reference Masket2008). According to Goodin (Reference Goodin2003, 378), peer accountability is “based on mutual monitoring of one another’s performance within a network of groups.” Peer accountability occurs when political entities are accountable to their professional community. In many cases, this accountability lacks formal sanctions. March and Olsen (Reference March and Olsen1989) suggest that the influence of conduct is driven by a logic of appropriateness or an internalized professional norm of appropriate actions. Under this theory, “actors seek to fulfill the obligations encapsulated in a role, an identity, a membership in a political community or group, and the ethos, practices and expectations of its institution” (March and Olsen Reference March, Olsen and Goodin2011). These types of peer ejects are inherently social and “soft” in the sense that they do not rely on formal/legalistic rules that punish behavior. Scott (Reference Scott and Dowdle2006) argues that the fear of “naming and shaming” or the loss of reputation drives the accountability effect.

City executives belong to an ever-growing peer network and routinely interact with their fellow executives (Einstein and Glick Reference Einstein and Glick2017). These connections leave officials susceptible to reputational pressures. I expect the potential for “naming and shaming” will increase responsiveness to open records requests.

H2 City government executives will be more responsive to requests for transparency when primed with a message about peer accountability.

Design and methods

To determine whether social pressures drive the behavior of local officials, I contacted a sample of mayors with open records requests via email. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, 2,098 cities have a population over 20,000. To generate a subset of mayors to contact, I retrieved email addresses from individual municipal websites and the United States Conference of Mayors (USCM). Though the USCM primarily represents cities with a population over 30,000, they still serve some mayors and city executives from cities with smaller populations. Footnote 4 I made every effort to include individual addresses that go directly to the office of the mayor, instead of to the general or city council accounts. My sample contained 1,409 city government executives across all 50 U.S. states. Footnote 5

Correspondence experiments are routinely used to test theories of responsiveness. Submitting open records requests through direct messages to individual record holders resembles how private citizen and news entities request public records in reality. As shown in Figure 1, I crafted an email that included both the necessary elements of the open records request and the primes. Footnote 6 I asked for 3 months of non-private governmental emails archived from the inbox and outbox of the mayor. Mayoral emails fall under the definition of public records, and the level of political risk involved in producing such records lead officials toward discretion (see Appendix D in the supplementary material for a further discussion about email records and ethics surrounding this study).

Figure 1 Treatment Email.

Table 1 Treatment Conditions

To effectively prime social pressure, I follow a two-step process: (1) establish the norm (or type of pressure) and (2) trigger its application. Footnote 7 Table 1 shows the language used in each condition. For the duty prime, I establish the norm by explicitly stating there exists a duty to share information. Second, I triggered the application of the norm implicitly by paraphrasing a Pew Research Center poll published in 2015 that discussed Americans’ views about open governmental data. I use the poll to raise awareness that the public is concerned with the lack of transparency.

To test the peer effects hypothesis, I lay out two Footnote 8 necessary elements: (1) acknowledge a peer group; (2) establish a potential for surveillance and enforcement. Because mayors are the actors to be studied, I first identify that the request was sent to other city government executives that serve as their comparison group. Next, I establish the potential for surveillance and accountability by stating that I will create a report and send it to the peer group. Upon receiving this peer accountability prime, one mayor in the largest city of a midwestern state asked “[are you] ranking us to others?” This provides some evidence that the peer prime raises awareness that others will know if and how they responded to the request. I also undertook three post-experiment interviews where I sent mayors in the control condition the two treatment primes and asked them to detail their thoughts about the wording. The mayors interviewed collectively saw the peer effects prime as a tool to shame them into complying with the request and the duty prime as a tool to spur thinking about the legal and public obligations to respond to the request. Footnote 9

I define responsiveness (Initial Response) as an indicator of whether any public official responded. The majority of the initial responses acknowledged their receipt of the email or stated that they forwarded it to a staff member. I use two estimators: intent-to-treat (ITT) and complier average treatment effect (CACE). The ITT estimator corresponds to the average response rate by each treatment group. This approach, however, assumes all of the emails were received and opened. Using an instrumental variables approach, the CACE will overcome the potential bias in differing open rates among the treatment groups (Gerber and Green Reference Gerber and Green2012; Sovey and Green Reference Sovey and Green2011). Footnote 10 I use an indicator of whether the email was opened as an instrument for receiving the intended treatment message.

Results

The total open rate for the experiment is 78%. Footnote 11 Out of 1409 emails sent, the overall response rate is 51%. Footnote 12 Conditional on being opened, the response rate is 66%. The control condition, which cites the open records law with no further treatment message, has a response rate of 53.5%. The descriptive evidence in Table 2 indicates that social pressure, as encapsulated by the Duty prime, increased responsiveness by 1.5 percentage points (55–53.5%). The Peer Effect prime decreased responsiveness by 6.8 percentage points (46.7–53.5%).

Table 2 Response Rates by Treatment Condition

Note: This table reflects the raw number of responses and the response rates by experiment condition.

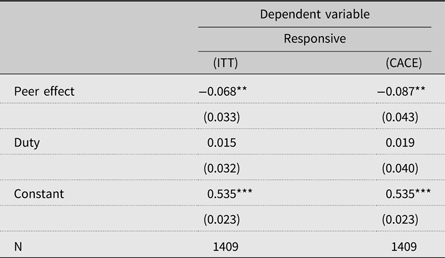

I next examine whether response rates differ by social pressure using a regression framework, which allows the construction of reliable estimates and standard errors. The first model in Table 3 shows the ITT with robust standard errors. The Duty treatment increases responsiveness by approximately 1.5 percentage points; however, the estimate is not statistically significant. The Peer Effects treatment decreases responsiveness by 6.8 percentage points with a p value of less than 0.05.

Table 3 The Effect of Social Pressure on Responsiveness

Note: *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01. Robust standard errors are used across all models in the parentheses. I correct p values for multiple comparisons in Appendix G in the supplementary material.

The second model shows the estimated treatment effects under the instrumental variable approach. The Duty condition continues to show a non-distinguishable impact, while the Peer Effects condition shows a stronger effect by decreasing responsiveness by 8.7 percentage points. In short, I find no support for hypothesis 1 and find evidence counter to hypothesis 2. I explore heterogeneous effects in Appendix F in the supplementary material. I find no substantive results when examining institutional or personal characteristics of the city and the mayor.

Discussion

Having conducted an open records experiment on U.S. mayoral offices, I fail to find strong evidence that social pressures affect city executives in intended ways. A message crafted to remind mayors of their civic duty to respond to requests did not significantly increase the probability of responding to such requests. Contrary to expectations, I find evidence that priming peer accountability decreased the likelihood of responding to the request for transparency. This suggests a “backfire” effect.

One reason the duty prime failed was that the language might not have been strong enough. A survey conducted after the experiment revealed that only 43% of mayors were more likely to respond after knowing the public’s belief about transparency (see Appendix H in the supplementary material). Another reason the duty prime could have failed to show a distinguishable increase is the professionalization of local bureaucrats. Mladenka (Reference Mladenka1981) suggests that having a process routinizes certain services that leave little room for discretion. For example, once emails are received, the mayor (and their staff) filter emails based on importance and decide which ones require a response. Under this scenario, open records requests – since already required by law – should have an institutionalized process by which they respond. This process leaves little discretion in the extent to which requests will receive a response.

I expected the peer effects prime to yield an increase in responsiveness. Empirical research has traditionally found positive effects of monitoring or threat of surveillance (Gerber, Green, and Larimer Reference Gerber, Green and Larimer2008; Panagopoulos Reference Panagopoulos2014 a,b). This paper suggests the opposite. The results point to a “backfire” effect. Literature in social psychology finds that under strong pressures, individuals may devalue actions being promoted or blatantly refuse to submit to pressures. Others (Ringold Reference Ringold2002) call this theory of reactance the “boomerang[ing] effect.” Footnote 13 This negative pattern has also been observed, unintentionally, in other audit experiments that use negative social pressure (Terechshenko et al. Reference Terechshenko, Crabtree, Eck and Fariss2019). Mayors seem to be divided on whether the peer language would increase or decrease their likelihood of responding (see Appendix H in the supplementary material for further discussion).

In the context of this experiment, the message about other mayors and accountability might be seen as a heavy-handed way to get compliance. Gerber, Green, and Larimer (Reference Gerber, Green and Larimer2008) theorized that appeals to neighbors through implied accountability are a stronger social pressure than appealing to civic duties. Under the same framework, appeals to duty are a mild form of social pressure, while the appeal to peers and publication applies the maximal social pressure. The negative effect of peer pressure may have shown mayors’ adverse reaction to overt pressure. Future experiments designed to distinguish positive versus negative theories of social pressure are needed to achieve greater certainty about the mechanism.

Conclusion

Open records laws enable individuals to peek into the black box of governmental deliberation and decision-making. Though many see open records request as purely part of the administrative process, city executives exercise discretion in both the responsiveness and compliance with the laws. This paper sought to explore the extent to which social pressures may influence how city government officials respond to request for transparency.

I induced social pressure in two ways: (1) norms and transparency and duty to respond, and (2) peer accountability. I find no evidence that priming duty impacts responsiveness. Contrary to expectations, the peer effects treatment causes a lower response rate. The psychological theory of reactance may explain this counterintuitive result. Mayors react negatively to strong social appeals that heighten awareness of their peers. My finding necessitates future research on how theories of negative social pressure, which we already know affects individuals, might also generalize to political elites.

Finally, in their requests for greater governmental transparency, citizens, the media, and researchers must be cautious about how they request information because the language might cause unintended consequences.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.22.