What is the relationship between Area Studies (AS) and International Relations (IR) knowledge production? This is a question that has been asked by scholars of the two disciplines throughout their interrelated development, due to the ‘intuitive’ overlap and complementarity of the study of ‘the international’ and ‘area’.Footnote 1 Indeed, this question continues to hold resonance for at least two contemporary IR debates: on how to counteract IR's Western-centralism and on the disciplinary status of IR vis-à-vis the other social sciences.

Over recent decades, an important and wide-ranging research agenda has critiqued IR's variously Western-, Euro-, and Anglo-centric practices of producing knowledge about the world.Footnote 2 One commonly suggested route by which IR may counteract this Western-centric bias is to enhance its a priori knowledge about other parts of the international. To this end, a variety of scholars advocate greater engagement with AS scholarship.Footnote 3 In spite of these prescriptive calls, however, it remains an open question how and to what extent contemporary IR interacts with AS. This is because although some studies have examined the overarching logics governing the relationship,Footnote 4 there have been few attempts to map practices of knowledge exchange between the two disciplines. And, thus to consider whether AS plays a meaningful role in counteracting shortfalls in IR's a priori knowledge of other worlds of IR.

Although it features in the debate about how to ‘deprovincialize’ IR, the IR–AS relationship has largely been neglected within the discussions about IR's position within the social sciences.Footnote 5 Among these scholarships, the predominant focus is on whether IR is a distinct discipline to, or subfield of, Political Science,Footnote 6 and IR's subordinate standing in its relationship to the ‘master’ social sciences.Footnote 7 Indeed, some scholars have argued that IR has an ‘inferiority complex’ in its relationship to other social science disciplines.Footnote 8 The absence of IR's relationship to AS in these debates is pertinent, because it represents an interesting counterpoint to these other interdisciplinary relationships, as one in which IR has been described as the first-order discipline.Footnote 9 The IR–AS relationship, therefore, offers a subtly different vantage point on the debate about IR's standing within, and approach to, the disciplinary-politics of the social sciences. Taking this into account, this paper considers whether IR seeks to reproduce its own experience as a subordinate to the ‘master’ social sciences or seeks to engage with AS in a less hierarchical and more reciprocal exchange of knowledge?

In light of its relevance to the above IR debates, this paper provides a macro-sociological analysis of the contemporary practices of IR–AS knowledge exchange, by way of mapping citation exchange between journals. In this way, it seeks to move beyond ‘black boxed’ accounts of the IR–AS relationship as homogeneous disciplines wholes. The disciplinary labels IR and AS both conceal divergent groupings of scholarship. The ‘fragmentation’ debate has called attention to the different ‘sects’,Footnote 10 ‘campfires’,Footnote 11 or ‘paradigms’,Footnote 12 that compose disciplinary IR whereas AS is a disciplinary umbrella identity for a collection of distinct scholarships on particular ‘areas’ (e.g. Middle East, Latin America, Africa, and so on). Nonetheless, most existent scholarship considers the IR–AS relationship in the context of ‘mainstream’ US IR scholarship and a particular ‘area’ scholarship, most commonly Middle Eastern studies. By contrast, this paper maps citation exchange between a variety of IR and AS journals. This enables the differentiated knowledge exchange practices between different ‘fragments’ of IR and the various ‘area’ scholarships of AS to be traced. In so doing, it asks which parts of the much-discussed ‘divided discipline’ of IR are most and least active in exchanging knowledge with AS? And, whether AS scholarship on certain areas are more influential upon, some types of, IR scholarship than others?

The paper, first, outlines the disciplinary-politics of the IR–AS knowledge exchange relationship. Second, it sets-out its framework of citation analysis. Third, it examines the citation relations between IR and AS journals. Fourth, it discusses the implications for the questions set out above. Fifth, and finally, it reaches a conclusion about these questions.

Disciplinary-politics and the IR–AS relationship

Over recent decades, there has been a lively debate about IR's relationship and standing vis-à-vis other disciplines.Footnote 13 However, IR's relationship to AS has been largely neglected. This is somewhat surprising, because there are notable similarities and complementarities in the historical development, scholarly focus, and academic standing of the two disciplines. As Morgenthau noted in the early 1950s: ‘Area studies, both historically and analytically, form a part of that field of knowledge which is called international relations’.Footnote 14 This statement can be interpreted as referring to the ‘whole-part’ relationship between the two disciplines' objects of studyFootnote 15: the ‘international’ as a whole made up of ‘area’ component parts.Footnote 16 In light of this mutually-implicated focus, Valbjørn states that ‘at an intuitive level, it would be natural to expect a long history of intense and fertile cross-disciplinary exchange’.Footnote 17 Indeed, this logic informs the calls by IR scholars for greater engagement with AS as a way to counteract IR's tendency to universalize knowledge based solely on the particular historical experiences of Europe and the USA.Footnote 18

However, as Teti outlines, IR and AS ‘seem historically unable to build interdisciplinary bridges’.Footnote 19 This is not to suggest that there are no ties between scholars or that no scholarship from one had influenced the other. The extent, however, would seem to be less than one might ‘intuitively’ expect, given the similarities and overlaps outlined above. Indeed, scholars have noted that IR and AS function in relative isolation from one another in ‘two different scholarly worlds’, with their respective journals ‘rarely having the same contributors, or even appealing to the same readers’.Footnote 20 For example, Korany highlights the near absence of references to the ‘third world’ contexts in IR textbooks.Footnote 21 Brand also suggests that to make a career in IR, one should test theory on empirical developments that are relevant to the USA and Western Europe, rather than the ‘difficult cases’ of (non-Western) areas.Footnote 22 As a result, Fawcett notes any scholar ‘brave enough’ to transverse the divide between IR and AS will find that they are ‘obliged to wear “two hats”’, one each ‘to suit different fora and publics’.Footnote 23

This paper sets out to map knowledge exchange between IR and AS, in order to evaluate whether such characterizations are borne out by research practice. To frame this analysis, it is posited that a common barrier to exchange between disciplines is the politics of such interdisciplinary relationships and the wider context in which they are embedded. Taking this into account, this section provides an account of (1) how disciplinary-politics impacts the relationship between disciplines, (2) the disciplinary-politics animating both AS and IR, and (3) how this impacts the relationship and exchange of knowledge between them.

Disciplinary-politics

The ‘discipline’ remains the predominant organizing principle and source of social capital within the academy.Footnote 24 As well as dictating institutional arrangements and identities,Footnote 25 the value, relevance, and legitimacy of academic knowledge is considered as corollary to disciplinary practices: iterative internal disciplinary debates about a particular object of study.Footnote 26 As a result, there are significant stakes at play in maintaining a strong disciplinary identity, which can be differentiated from the practice and debate of others disciplines.Footnote 27

At the same time, a successful and healthy discipline is widely regarded as one that engages with other disciplines, in order to avoid ‘intellectual autism’ by introducing new ideas into its knowledge production.Footnote 28 Furthermore, a discipline's status is also a function of its capacity to produce ‘tradeable [academic] “goods”, such as theories, concepts, methods, and empirical data’ that go on to influence other disciplines.Footnote 29 In other words, disciplines interact with one another in a social field – for example, the social sciences – with these relations structured by the same dynamics active in all social fields, including contestation over hierarchies, identities, legitimacy, and boundaries.

In this way, disciplinary-politics is characterized by the efforts to manage disciplinary closure and interaction with other disciplines. The capacity of a discipline to do so is strongly conditioned by the context in which it operates. Namely, the wider university, academy, and extra-academy structures within and through which a discipline develops.Footnote 30 As a result, each discipline is a product of a particular variation in disciplinary-politics. This manifests itself, one, in the intradisciplinary composition of a discipline. Thereby, some are seen as highly coherent and others as ‘chaotic’ collections of scholars that compete over subject matter, methods and what comes to be collectively viewed as legitimate disciplinary knowledge production.Footnote 31 And, two, in a discipline's position vis-à-vis other disciplines. Thereby, some come to be regarded as ‘masters’ that set the standards of what academic knowledge should be and others as ‘derivative’ to these ‘master’ disciplines.Footnote 32 Against this background, disciplinary-politics invariably has a significant influence on the relationship between two disciplines, irrespective of the extent to which their subject matters and knowledge production overlap with or are complimentary to one another.

Area studies and disciplinary-politics

Contemporary AS has been strongly shaped by the post-WWII US academy. Due to the expectation that the USA would play a greater role in more parts of the world, significant governmental, and private funding was made available for the development of ‘area’ specialists post-1945, aimed at addressing a national shortfall of knowledge about the non-West.Footnote 33 The wider relevance of AS scholarship within US academia was further boosted by the emergence of the Cold War logic of bipolar competition, with AS centres claiming to contribute to the goals of ‘knowing the enemy’,Footnote 34 or informing government and international organizations' policies to ensure that distant countries followed a path consistent with a US-centred capitalist global system.

This support came, first, from the schemes of private foundations, such as Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Ford,Footnote 35 and second, the ‘Title VI’ government research funding made available to universities from 1958 onwards. The availability of these resources led to what van Schendel characterizes as a ‘scramble for area’ within US universities. As a result, ‘area’ scholarships – such as Soviet, Middle Eastern, African, East, Southeast and South Asian, and Latin American AS – very quickly took on the characteristics of academic disciplines, becoming ‘firmly established within the university setting’ and a component part of the wider system of social sciences.Footnote 36

Aside from the national interest justification, AS centres were also set up in accordance with a wider vision about the contribution that ‘area’ scholarship should make to the social sciences. First, by offering a ‘multidisciplinary’ approach, which would ‘integrate’ the separated knowledges of the social sciences to produce ‘truly interdisciplinary knowledge’ about a particular ‘area’.Footnote 37 Second, it was anticipated that this holistic AS knowledge would be fed back into the other disciplines, to test and refine their theories and hypothesis towards the goal of universal social knowledge. This remains the dominant interpretation of AS's role in the social sciences.Footnote 38

This dynamic is conditioned by the particular organizational system of US universities.Footnote 39 It centres on a clear set of institutional and conceptual divisions between the social sciences, each orientated towards the study of a distinct and abstract thematic sphere of social practices.Footnote 40 Hence, Economists, Political Scientists, and Sociologists should produce knowledge on the economy, the political system and society, respectively. However, not all would-be disciplines are framed on such seemingly clear-cut thematic objects of study. Notably, IR, AS, and geography are said to be investigating the social practices of demarcated spatial objects of study, namely the international, an area and spatial relations in general. In the disciplinary-politics of the USA, and thus largely the Western, academy, the former set of disciplines are commonly regarded as the ‘master’ disciplines of the social sciences, to which the latter are subordinate.Footnote 41

This hierarchical distinction between AS and the so-called ‘master’ social sciences is further sharpened by the ‘logic’ and ‘sort of scholarship’ that follow from their differing types of object of study.Footnote 42 According to several AS scholars, the thematic social sciences, in general, aim to produce universal scientific laws to explain the practice of political systems, the economy and society.Footnote 43 By contrast, AS scholarship seeks to account for the peculiarity of the political, economic, or societal practice in an ‘area’, often by reference to its unique history and culture that is said to shape its particularity.Footnote 44 In this way, the US social science system developed ‘based on the separation of universalist and abstract “Disciplines” from “Areas” concerned with the particular and the empirical’.Footnote 45 In other words, the former are considered as producing ‘theoretical’ knowledge and the latter as applied ‘empirical’ knowledge.

Indeed, the so-called ‘Area Studies controversy’ of the 1990s illustrates this divergence. Against a backdrop of a turn to rationalist epistemologies and behavioural theories,Footnote 46 the very validity of AS as a discipline and mode of scholarship was brought into question. Tessler et al. suggest that this debate ultimately centred on ‘an important disagreement about social science epistemology’.Footnote 47 According to this interpretation, the behaviourist-infused rationalism prevalent in most US social science disciplines during the 1980s and 1990s viewed the cultural-infused interpretivism of AS scholarship as anathema to what they held as the single goal of social research: universally applicable and valid theories and hypotheses. In the context of US disciplinary-politics, AS's function has thus developed as one in which it produces empirical data on a particular ‘area’, which can then be exchanged for the theory and universal laws of the thematic disciplines.Footnote 48 In this way, Jørgensen and Valbjørn outline that AS's role is as ‘a “gas station”, the primary function of which is to provide “local empirical data” to be used in the testing of (grand) theories developed within the superior disciplines’.Footnote 49 This exchange of academic ‘tradeable goods’ is not viewed as one of equivalent value, with thematic theory considered as having greater academic currency than area empirics. This exchange-rate has left AS in a permanent ‘sense of “crisis”’.Footnote 50

The relationship between AS and the social sciences within the US context has, largely, been transposed onto English-language European academia. There are, nonetheless, certain distinctions.Footnote 51 ‘Area’ scholarship in much of Western Europe predated its development in the USA.Footnote 52 This pre-WWII ‘area’ scholarship was more associated with the classical humanities disciplines, than the social sciences have been in the USA.Footnote 53 Thus, its initial geopolitical relevance was framed by its own problematic history of being implicated with the discredited practices of imperial domination, rather than the bipolar competition of the Cold War.Footnote 54 At the same time, contemporary US-style AS centres were gradually established in Europe during the Cold War period, albeit within a different university context.Footnote 55 For example, the emphasis on the division of academia into mutually exclusive thematic social sciences was less prevalent in Europe than in the USA, and the drive to establish universal laws of the social world was less hegemonic.

In this way, European universities were relatively less influenced by the rational-choice wave of behavioural theorizing in the 1970s and 1980s. They were, however, impacted upon more by the countervailing trend of the reflectivist turn that came to prominence from the 1980s onwards. From an opposing epistemological starting point, this paradigm refuted the possibility of universal knowledge, and instead emphasized the contextually-situated and self-reflexive nature of all knowledge. This reflectivist turn brought a new critique of AS scholarship to the fore, which was exemplified by the ‘Orientalist’ critique, associated with Edward Said.Footnote 56 Reflectivist scholarship has suggested that AS scholars fail to recognize that the unique ‘culture’ that they use as a causal variable to explain behaviour is not so much derived from the behaviour of actors in the ‘area’, as their own interpretation of this culture and area as exotic and deviant in comparison with their perceptions of the ideals of the West.Footnote 57 In this context, the relationship between AS and other disciplines developed according to a different form of contestation among some sections of European disciplinary scholarship, as compared to the USA academy.

IR and disciplinary-politics

Similar to AS, IR's claim to disciplinary status has been widely debated during recent decades.Footnote 58 In contrast to AS, however, this debate has been centred less directly on its relations to other disciplines and more on its intradisciplinary divisions, particularly along the lines of the so-called ‘great debates’. Indeed, Kristensen outlines that most of this ‘state of the discipline’ scholarship concludes that IR is a ‘more fragmented discipline today’,Footnote 59 and often self-diagnoses IR as a ‘dividing discipline’,Footnote 60 composed of distinct ‘sects’,Footnote 61 ‘campfires’,Footnote 62 or ‘paradigms’ being.Footnote 63 Among the lines of fragmentation commonly highlighted, arguably the most prominent is that between IR scholarship based on the differing epistemological commitments of rationalism and reflectivism: the so-called fourth great debate.Footnote 64 This macro-epistemological divide is also often mapped onto a geographical divide between a ‘rational choice and quantitative’ American-based/orientated, and a ‘generally more constructivist, postmodernist’ European-based/orientated IR scholarship.Footnote 65

With respect to this geographic divide, the well-known statement that ‘IR is an American Science’ is symbolic of the view that, since at least the 1960s, IR has been a discipline strongly shaped by the US-academic context.Footnote 66 Indeed, US IR scholarship generally holds a greater status than other national IR scholarships: the most prestigious ‘international journals’ are based at US institutions and publish mostly US scholars and ‘US-style’ articles.Footnote 67

At the same time, IR is not a monolithically US-centric discipline. Recent decades have seen a more distinctive European-orientated IR scholarship gain in significance and prominence, establishing its own journals, professional associations, and schools of thought and theories.Footnote 68 Indeed, since the 1980s, this scholarship has critiqued the US-centric nature of IR scholarship, including by advancing reflectivist-infused perspectives as a counterpoint to the predominantly rationalist grounding of ‘the omnipresence of US-style IR all over the world’.Footnote 69 Although such a binary division – rationalist/US and reflectivist/European – greatly oversimplifies the broad spectrum of IR scholarship, this paper posits that it serves as a useful heuristic shorthand for characterizing an important line of distinction within IR's internal disciplinary-politics.

However, the fragmentation debate cannot be considered in isolation from IR's external relations to the other social sciences. Indeed, it has been suggested that IR's intradisciplinary handwringing derives from its own ‘inferiority complex’ about whether it holds the status of a standalone discipline or a sub-field of Political Science.Footnote 70 Another line of enquiry has highlighted that IR does not export big ideas to, but rather imports them from the ‘master’ social sciences, leaving it confined to the role of a second order discipline.Footnote 71

As with AS, a major source of both concerns stem from the nature of IR's object of study. IR is most commonly understood as the investigation of ‘the international’.Footnote 72 Albert and Buzan note that this may be considered either as the study of a specific realm of the social world in its own right as ‘international politics’ or as ‘everything in the social world’ at the ‘macro’-scale of ‘the international’.Footnote 73 The former position is more generally associated with US and rationalist IR scholarship, the latter is more characterized by European IR's reflectivist scholarship.

If interpreted as the study of ‘international politics’, IR appears as a sub-field of Political Science,Footnote 74 in line with the common interpretation within US academia that IR represents a ‘discipline within a discipline’.Footnote 75 Within this context, a thinner line of differentiation can be drawn between scholarship that is distinctively or primarily ‘IR’ and that which spans the divide to other subfields of Political Science. Comparative Politics arguably has the most overlap with, at least some, IR scholarship. In contrast to IR, it tends to be ‘heavily oriented toward empirics’,Footnote 76 and ‘driven by efforts to explain puzzles or questions rather than by the need to test a particular theoretical model’.Footnote 77 This informs distinctions drawn by some scholars between the development of unique IR theory and more ‘problem-orientated’ IR scholarship.Footnote 78

If depicted as the study of everything ‘international’, then IR is envisioned as a multi-, pluri-, or inter-disciplinary construct.Footnote 79 This interpretation of IR is more common among reflectivist and European-orientated IR scholarship, reflecting the ‘multidisciplinary’ origins of IR in a European context.

Against the background of the wider disciplinary-politics of the social sciences in which thematic knowledge is valued higher than spatial knowledge, both interpretations of its object of study potentially position IR in a subordinate position vis-à-vis the ‘master’ social sciences.Footnote 80

Disciplinary-politics of the IR–AS relationship

According to existent accounts, IR's engagements with AS operate very differently to its subordinate role in its relationship with the ‘master’ social science. The few scholars that have specifically examined the IR–AS relationship tend to argue that it is governed by a hierarchical mode of dialogue,Footnote 81 similar to that between AS and the ‘master’ social sciences. In other words, that AS is positioned as a subservient supplier of empirical data for the refinement of IR theory, and in return receives IR theory to inform its empirical scholarship.

Teti traces the development of Middle Eastern Studies in relation to mainstream US-orientated IR, noting that epistemic differences between the former's particularistic interpretivism and latter's universalist rationalism underpins this division of disciplinary labour.Footnote 82 Other scholars have noted that a similar dynamic between European-orientated reflectivist IR scholarship and AS. Jorgensen and Valbjorn note that such scholarship gives credit to ‘area specialists “on whose work we have drawn heavily”’, but nonetheless positions AS ‘as owners of local empirical data that can be purchased and appropriated for a substantially unaltered general theoretical framework’.Footnote 83 Such accounts, thus, depict an interdisciplinary relationship that is the polar opposite to that between IR and other social sciences. It, therefore, offers a different vantage point on how IR practices disciplinary-politics.

Although the aforementioned studies provide valuable macro-characterizations of the IR–AS relationship, they have not been accompanied by any analysis tracing how such logics play out in the concrete practices of knowledge-exchange between IR and AS. As such, it is an open question whether, to what extent and in what ways IR is engaged in knowledge-exchange practices with AS scholarship? This is in part due to the framing of the relationship as one between two ‘black-boxed’ disciplines. In other words, each is represented as a singular homogeneous whole. However, as the above accounts of the internal disciplinary-politics of both IR and AS indicate, it is illusory to suggest that there is one form of either's scholarship.

By the very nature of the AS project, there is no single discipline of AS. As outlined, it is broken up into a series of ‘Area Studies’ orientated around a particular ‘area’ (e.g. East Asia, Middle East, or Latin America). Furthermore, all ‘multidisciplinary’ area scholarships ‘have their dominant disciplines, dominant theories, dominant centres of excellence and so on’.Footnote 84 As a result, they tend to hold differing relations to the other social science disciplines.

What is more, the interest of other disciplines in particular ‘area’ scholarship is impacted by their current ‘claims to geopolitical relevance’, with respect to policy practitioners, wider public debates and the grand narratives of the national context in which are embedded.Footnote 85 Very often, this manifests in terms of a discourse of threat or danger to the West, whereby, for example, Soviet AS received disproportionately high levels of funding, attention, and importance during the Cold War.Footnote 86 Therefore, one may expect IR to show greater interest in AS scholarship focused on an ‘area’ seen as having greater geopolitical relevance to Western interests and ‘global’ discourses.

Equally, as outlined above, IR scholarship is divergent along a number of intradisciplinary lines of distinction. This paper has foregrounded those between different points on ‘the rationalism–reflectivism axis’,Footnote 87 with such differences broadly corresponding to a distinction between US-orientated and European-orientated IR scholarship.Footnote 88 To these distinctions, one can add the difference between IR's topical speciality literatures, which include Security Studies, Conflict Studies, International Organization, most of which are often represented by their own debates and journals.

This intradisciplinary differentiation, in turn, may result in some fragments of IR engaging with AS scholarships in ways that diverge from others. For example, a number of scholars have suggested that the growth of reflectivist IR scholarship since the 1990s ‘affords a possible environment’ for greater convergence between IR and AS, because reflectivist IR scholarship is more compatible with the interpretivist and inductive approach of most ‘area’ scholarship than rationalist IR scholarship.Footnote 89 Indeed, the critique of IR's ‘parochialism’, upon which the calls by IR scholars for greater engagement with AS scholarship are based, has come mainly from reflectivist IR scholarship.Footnote 90

In sum, this paper suggests that to examine and analyse an interdisciplinary relationship, it is necessary to also consider each discipline's respective intradisciplinary fragmentation. From this perspective, the IR–AS relationship is composed of a diverse and uneven set of knowledge-exchange practices between some fragments of each discipline, but not others. Therefore, this paper's mapping of citation practice will ask whether rationalist/reflectivist, US-based/European-based or topically-differentiated versions of IR hold similar or distinct relationships to ‘area’ scholarship? And, whether these IR scholarships engage with the knowledge produced by AS scholarship on certain ‘areas’, but not others? In this way, it aims to provide a more nuanced account of whether and to what extent the disciplines of IR and AS engage in knowledge-exchange with one another.

Scientometrics: mapping interdisciplinary practice

Scientometrics aims to trace and make visible the latent structures of academic practice. To this end, publication is foregrounded as a key practice. Due to the academic conventions of peer-review and citation, Leydesdorff and Milojević suggest that publications represent ‘validated’ artefacts that are ‘admitted to the archive of published, and thus authenticated scholarship on which future work can be built’.Footnote 91 As such, publications circulate around, and thus animate, scholarly communities (such as disciplines), and act as the primary ‘token’ of value, legitimacy and status to be exchanged among its membership. For example, the citation of an AS article by an IR article may be seen as a claim that this piece of IR knowledge-production is informed by authenticated knowledge about a (non-Western) ‘area’.

Furthermore, publications, and especially journal articles, are viewed by scientometricans as an equivalent, and hence comparable, practice that is evident throughout academia. And, thus as an appropriate measure with which to map macro-level structural practices within and between disciplines. To this end, scientometrics techniques have been previously used to examine the ‘structural properties of IR communication’,Footnote 92 highlighting its paradigmatic divisions,Footnote 93 geographic stratification,Footnote 94 and gender citation gap.Footnote 95

Citation analysis is the most commonly used scientometrics tool for investigating the exchange of knowledge between ostensibly distinct disciplines.Footnote 96 The social convention within the academy is to acknowledge the sources that form the knowledge base on which your publications are built, by way of citation. Therefore, citation flows from articles/journals deemed as representing one discipline to those of another is commonly viewed as indicative of interdisciplinary knowledge exchange.Footnote 97

However, the giving and receiving of citations cannot be unproblematically assumed to communicate an expression of intellectual inspiration and debt. As Wyatt et al. argue, ‘[c]itations can be a form of strategic behaviour, or reflect a cognitive debt, and they may also be a reflection of a social hierarchy within the scientific community’.Footnote 98 Hence, interdisciplinary citation exchange does not necessarily represent a significant import of new concepts, methods, or empirics from one discipline into another (intellectual debt). It may also indicate a rhetorical move, aimed at capitalizing on the current high-value currency of interdisciplinary research (strategic), a social hierarchy among disciplines or a practice of ‘handwaving’ at another discipline by symbolically citing a high-profile author or work as ‘a shorthand for a specific argument, theory, method, or school’.Footnote 99

What we can say, however, is that the act of citation establishes an observable and traceable public academic relation between two publications. Against this background, citation analysis represents a practice that can be heuristically mapped to consider the extent to which IR and AS publications draw on each other's knowledge production to construct their own.

Demarcating IR and AS by journals, data assembly and network maps

As outlined by Waever, the ‘sociology of science from Merton to Whitley has pointed to journals as the crucial institution of modern sciences’, and hence to journals being ‘the most direct measure of the discipline itself’.Footnote 100 Therefore, this paper focuses on the journal level to examine citation exchange between IR and AS. In so doing, it notes that it is important to remember that ‘scientometric constructs remain grounded in discursive decisions about how to best represent latent structures in the data’.Footnote 101 In other words, the decisions by the analyst to include or exclude journals as representing a discipline impact on the picture of interdisciplinary citation that is produced. Therefore, this paper seeks to be as open and clear as possible in detailing how it represents both IR and AS by its selection of journals.Footnote 102

Thomson's Journal Citation Reports (JCR) database was used for selecting, gathering, and organizing journal data for further analysis.Footnote 103 However, the ‘disciplinary’ categories of the JCR are widely questioned and the criteria for composing these disciplinary categories are not publically available.Footnote 104 Therefore, rather than taking the full set of journals listed within these categories, a smaller sample of journals was selected based on their ranking in terms of ‘5 year impact factor’ and the author's own judgement on whether journals are important to disciplinary communication. Twenty IR and 29 AS were selected (see below).Footnote 105 This choice was made to include a selection that is broad enough to ‘capture the diversity’ of a discipline, but also restrict the sample to a ‘small number of journals that are best representative’, in order to facilitate meaningful visual analysis of the citation networks.Footnote 106

20 IR journals:

• British Journal of Politics International Relations (BJPIR)

• Conflict Management and Peace Science (CMPS)

• Cooperation and Conflict (CC)

• European Journal of International Relations (EJIR)

• Global Governance (GG)

• International Affairs (IA)

• International Organization (IO)

• International Political Sociology (IPS)

• International Security (IS)

• International Studies Quarterly (ISQ)

• International Studies Review (ISR)

• International Theory (IT)

• Journal of Conflict Resolution (JCR)

• Journal of Peace Research (JPR)

• Journal of Strategic Studies (JSS)

• Millennium: Journal of International Studies (MJIS)

• Review of International Organization (RIO)

• Security Dialogue (SD)

• Security Studies (SS)

• World Politics (WP)

The 20 IR journals, listed above, are representative of a version of IR that encompasses the different classificatory short-hand divisions of disciplinary IR, as outlined above.Footnote 107 Hence, it includes journals focusing on different topical areas;Footnote 108 a mix of predominantly epistemologically rationalist-orientatedFootnote 109 and reflectivist-orientatedFootnote 110 journals; journals that can characterized as mainly US-based/orientated,Footnote 111 and mainly European-based/orientated,Footnote 112 according to their institutional-base and the make-up of their editorial boards; and journals that are more orientated towards IR theoryFootnote 113 and more towards comparative and ‘problem-orientated’ analysis.Footnote 114

29 AS journals:

African Area Studies:

• Africa Spectrum (AS)

• African Affairs (AA)

• African Studies Review (ASR)

• Journal of Eastern African Studies (JEAS)

• Journal of Modern African Studies (JMAS)

• Journal of Southern African Studies (JSAS)

Chinese Area Studies:

• China Journal (CJ)

• China Quarterly (CQ)

• Journal of Contemporary China (JCC)

East Asian Area Studies:

• Critical Asian Studies (CAS)

• Journal of Asian Studies (JAS)

• Journal of Contemporary Asia (JCA)

• Journal of East Asian Studies (JEAS)

• Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (JSEAS)

• Pacific Affairs (PA)

East European Area Studies:

• East European Politics and Societies (EEPS)

• Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies (JBNES)

• Journal of Baltic Studies (JBS)

• Southeast European and Black Sea Studies (SEBSS)

Latin American Area Studies:

• Journal of Latin American Studies (JLAS)

• Latin American Perspectives (LAP)

• Latin American Research Review (LARR)

Middle Eastern Area Studies:

• British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (BJMES)

• International Journal of Middle East Studies (IJMES)

• Middle East Journal (MEJ)

• Middle Eastern Studies (MES)

Post-Soviet Area Studies:

• Europe Asia Studies (EAS)

• Post-Soviet Affairs (PSA)

• Slavic Review (SR)

Demarcating ‘AS’ as a disciplinary set of journals is fraught with difficulty, because it is an umbrella disciplinary identity under which there are multiple discrete and distinct ‘AS’ fields.Footnote 115 The 29 AS journals, listed above, demarcate several distinct ‘area’ sets of journals, namely: African, Chinese, East Asian, East European, Latin American, Middle Eastern, and post-Soviet AS. The journals comprising these distinct AS scholarships all include journals that are institutionally based in both the US and Europe, with the editorial boards of many AS journals made up of a mix of scholars based on both sides of the Atlantic.

Dataset and analytical parameters

To analyse citation exchange between the 20 IR and 29 AS journals, this paper takes a ‘snapshot’ timeframe approach, whereby articles published in two 3-year periods are analysed: 2014–16 and 1997–99. In the scientometrics literature, different longitudinal methods are used to examine different research questions. Although extended periods enable analysis of the historical development of the intellectual base of a field. Shorter ‘snapshots’ are taken to assess ‘research fronts’,Footnote 116 understood as an emergent set of research practices. This paper follows the latter approach, because such snapshots provide a more meaningful account of research-in-practice. At the same time, a second snapshot allows comparison between a recent and an older period, enabling the analyst to assess, one, the long-term validity of any patterns in publication practice that are identified, and two, if there are any changes in such patterns over time. The period 1997–99 is chosen for pragmatic reasons, as these are the first years for which the Web of Science's ‘Journal Citation Report’ data are available.

Taken together, the articles published in these 20 IR and 29 AS journals during 2014–16 represent a data set of 4923 articles, comprising 2055 ‘IR’ and 2868 ‘AS’ articles. Of these journals, only 14 IR and 18 AS journals were also published during the 1997–99 snapshot. These journals published 2055 articles, made up of 890 IR and 1165 AS articles.

Using Thomson's JCR, the citations given by each article to all other journals under study for the periods 2014–16 and 1997–99 were harvested.Footnote 117 From these data, a full directed adjacency matrix was constructed for each period. In other words, a matrix detailing all citation communications between the 20 IR and 29 AS journals, both sending and receiving. To adjust the data for the variance in the number of articles published by each journal, the absolute number of citations given (links) by a journal to all others journals (nodes) were normalized, by dividing this number by the total number of articles published by a journal. In this way, the matrix is composed of the average number of citations given by a journal to another journal per article they publish.

An established scientometrics method of investigating citation communication is the visual analysis of network maps. Citation network maps enable the analyst to view the wider context of citation relations between journals. The network visualization programme Pajek was used to produce network maps for each period under study. The Kamada–Kawai energy algorithm was used to ‘force’ relations in the network into a map form, in which the significance and relationality of the nodes – journals – are expressed in terms of their positionality within the whole network – central or peripheral – and their relationality to all other nodes – closeness via the distance separating them.Footnote 118 This facilitates visual analysis of both the broader structural citation relations between all the journals under study (which journals are of central/peripheral importance), and the relative directionality and strength/weakness of citation exchange between pairs, triplets, or larger clusters of specific journals.

As the focus of this paper is on interdisciplinary knowledge-exchange between IR and AS, the network maps include only interdisciplinary citations (from a journal designated in one discipline to a journal designated as in the other discipline), To enable parsimonious visual analysis, thresholds limits on the inclusion of ties between nodes were set.Footnote 119 The aim is to avoid networks maps that are too congested to distinguish latent macro and micro structures, while also including as many ties as possible, so that the fullest picture of the complex relations can be considered.Footnote 120 A threshold of 0.1 citation is used for the 2014–16 network map. In other words, only citation links between IR and AS journals that are more frequent than an average citation rate of one every 10 articles, in either direction, are included. (IR-to-AS or AS-to-IR). A threshold of 0.05 citation is used for the 1997–99 network map.

Analysis: tracing the practice of IR–AS knowledge exchange

This section outlines the results of the paper's network mapping of citation communication between the 20 IR and 29 AS journals under study. This citation exchange is assessed at three degrees of granularity: discipline-to-discipline, journal-to-discipline, and journal-to-journal.

Discipline-to-discipline

As suggested above, much of the debate about interdisciplinary relations, in general, and the IR–AS relationship, in particular, tends to assume that the relationship is between two homogeneous disciplinary constructs. The value of such perspectives is that they inform analysis of the macro-disciplinary politics of knowledge production in the academy. It is suggestive of whether one discipline is important to another in its production of new knowledge, or whether one discipline's knowledge production is derivative or constitutive of another's. With this in mind, Figure 1 illustrates the average number of citations given by an IR journal to any of the AS journals under investigation, and likewise, the average number of citations given by an AS journal to any of the IR journals, for both periods of analysis.

Figure 1. Interdisciplinary citation flows between IR and AS.

First, it would seem that the significance of the knowledge produced by either discipline for the other's construction of new knowledge is limited. In both directions of citation flow, on average less than one in two articles cited an article in the other discipline between 2014 and 2016. This can be contrasted with the average of 10 citations per article given by an article in an IR journal to another in an IR journal, excluding journal self-references. From this perspective, although citation communication between IR and AS is not negligible, it is also not very influential.

By contrasting interdisciplinary communication between 1997 and 1999 with that between 2014 and 2016, we can see that the absolute number of citations given by an average IR article to an AS journal publication has doubled. Although, vice versa, the increase was slightly more than double. This increase in absolute number is, however, in line with a generalized increase in citation behaviour between the two periods, as the number of intra-IR citations also more than doubled.

Figure 1 also enables a comparison between the directionality of the citation flow. In both periods of investigation, IR articles cited fewer AS articles than the other way around. The difference being 1.38 (2014–16) and 1.37 (1997–99) citations of IR articles by AS journals for every citation of an AS journal by an IR journal. Hence, there has been a consistent disparity in the directional flow of communication since at least 1997. In other words, the exchange of citations between IR and AS is not reciprocal in nature, and thus not indicative of a perfectly balanced ‘gas station’ exchange of theory-for-empirics.

Journal-to-discipline

A singular discipline-to-discipline perspective reveals little about which parts of each discipline cites articles from the other. Therefore, this sub-section details how particular journals and clusters of journals in IR and AS communicate with those in the other discipline (Table 1).

Table 1. Average citations per IR article to and from all AS journals

Table 1 outlines the average number of citations per article received from and given to AS journals by each IR journal under study. It highlights that World Politics (WP) and International Security (IS) are by far the most likely to cite an article from an AS journal, in both periods under study. In general, WP has the most active exchange relation by an order of magnitude, both giving and receiving the most citations. WP is also twice as likely as any other IR journal to be cited by an AS journal, with International Organization (IO) being the next most likely. Indeed, IO is the journal with the greatest directional disparity in citation flows vis-à-vis AS journals, being cited relatively often by AS journals, but hardly ever citing AS scholarship in return.

One of the most prominent journals in ‘Conflict Studies’, the Journal of Conflict Resolution (JCR) also holds an unbalanced exchange relations to AS journals, citing one AS journal for every five times it is cited by an AS journal. The lack of citation communication between AS journals and what are described by this paper as ‘reflectivist’ and ‘European’ IR journals is notable. Among these journals, the European Journal of International Relations (EJIR), Security Dialogue (SD), and Cooperation and Conflict (CC) cite AS journals most frequently. However, this rate of citation is seven times less than WP and 4.5 times less than IS. However, it is the same as several other prominent US and mostly rationalist IR journals, namely IO, JCR, and ISQ (Table 2).

Table 2. Average citations per ‘area’ set of articles to and from IR journals

Table 2 outlines the average number of citations per article received from and given to the IR journals by the different ‘area’ clusters of AS. It highlights a significant disparity among the ‘area’ scholarships cited by IR journals, with certain ‘areas’ much more prominent than others. The journals focused on ‘Africa’ are most commonly cited by IR journals, followed by Chinese AS journals. The journals characterized as East Asian, East European, and Latin American AS are comparatively rarely cited by IR journals, with Middle Eastern and post-Soviet AS slightly more frequently cited. Between 1997–99 and 2014–16, there was an increase in both the absolute and relative citation flow from Middle Eastern and African AS journals to IR journals, and a relative decline in flows from East Asian and post-Soviet journals. Also noteworthy is that East Asian, East European, and post-Soviet AS all hold a significant disparity between outward citation of and inward citation by IR journals, in favour of the former.

Journal-to-journal

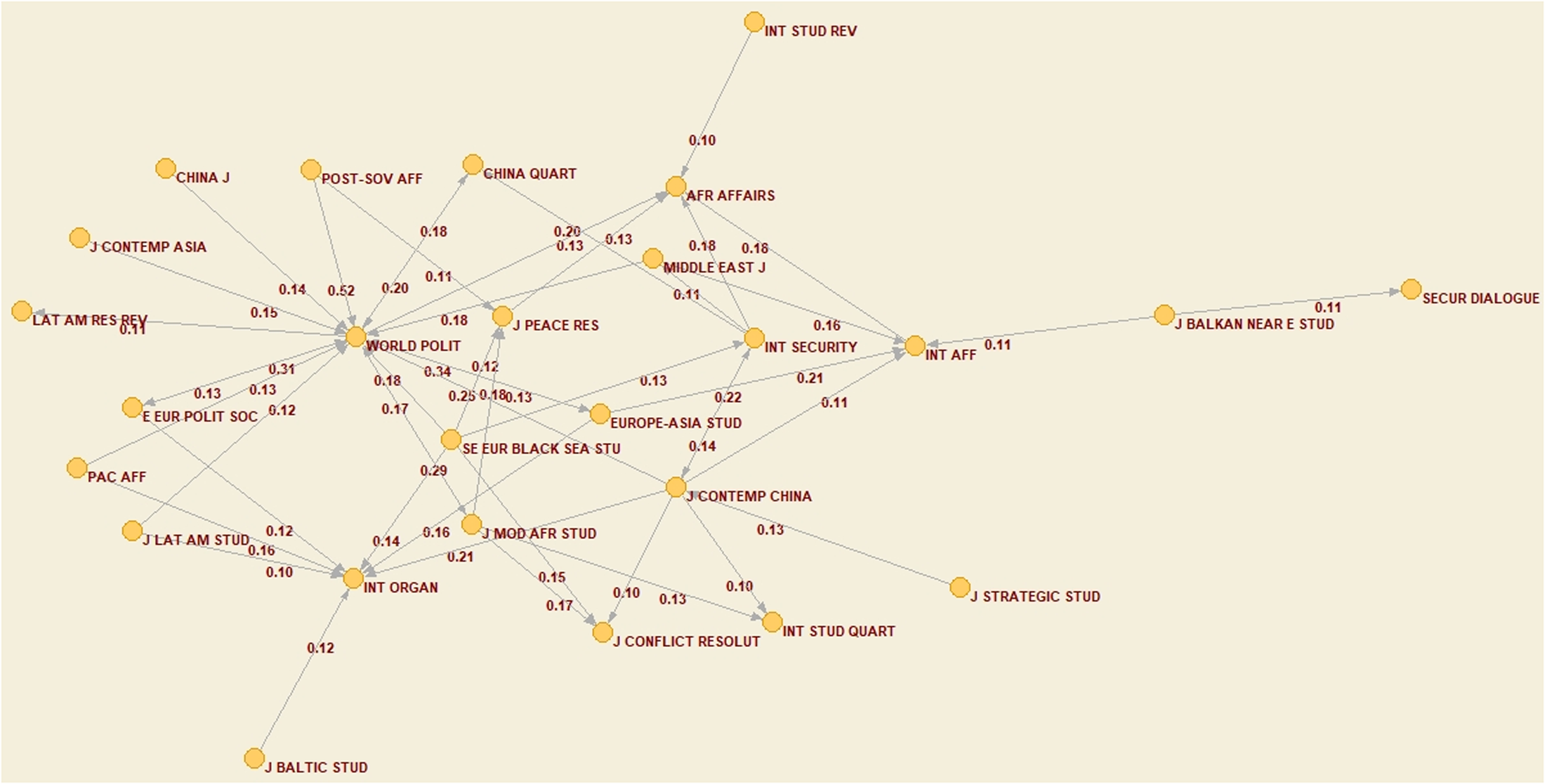

Although point-to-point perspectives are insightful for understanding particular relationships between disciplines or journals, a more established scientometrics approach to investigating citation communication is by visual analysis of citation network maps. Citation network maps enable the analyst to view the wider context of citation relations between journals, and thus to pick out more nuanced relations and patterns in interdisciplinary exchange. Following the specifications outlined in the previous section, the two interdisciplinary IR–AS citation networks – 2014–16 and 1997–99 – are displayed in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2. Interdisciplinary IR–AS citation network, 2014–16. Threshold limit of 0.1 average citations per article. This reduced the number of links in the network from 283 to the 53 strongest. The network includes 26 nodes (journals), but excludes 23 nodes (journals) that neither send, nor receive citation links more than 0.1 average citation per article.

Figure 3. Interdisciplinary IR–AS citation network, 1997–99. Threshold limit of 0.05 average citations per article. This reduced the number of links in the network from 68 to the 34 strongest. The network includes 18 nodes (journals), but excludes 14 nodes (journals) that neither send, nor receive citation links more than 0.05 average citation per article.

The network maps highlight that citation communication is dominated by AS journals citing high-ranked (according to Web of Science's impact factor metric) IR journals. In 2014–16, nine of the 10 strongest citation links are AS journals citing IR ones. Although four of the six strongest citation links between 1997 and 1999 are AS journals citing IR journals. WP is the most central and connected node in both periods. In 2014–16, it was involved in six of the seven strongest citation flows, and in five of these it is the cited journal. Although, in 1997–99, it was involved in four of the six strongest citation flows, and in three of these it is the cited journal. Indeed, if WP is excluded from the 2014–16 map, only nine of the 53 strongest citation relationships in the network are from an IR to an AS journal.

As the metric of degree centrality confirms, WP is the IR journal that is connected to the most AS journals in both periods, being cited by and citing journals from all the ‘areas’ under study. This stands in contrast to the other IR journals in the networks that only have limited links to certain ‘areas’. In both periods, traditional security studies journals – IS and JSS – cite Chinese AS journals, while IS also cites African and Middle Eastern AS journals. In 2014–16, Conflict Studies journals – JPR and CMP – both cite African AS journals, as does International Affairs (IA) and International Studies Review (ISR). Hence, among IR journals excluding WP, there is a strong bias towards citing African and Chinese AS journals, compared to AS knowledge production on other ‘areas’.

The second most commonly cited IR journal in the network, IO holds a less diverse set of cited links to different ‘areas’ compared with WP: IO, is cited by East Asian, China, post-Soviet, and Latin American AS journals in both periods. In 2014–16, IS is cited by Chinese and an East European AS journals, but not by the Middle Eastern and African AS journals that it cites most frequently. Hence, it could be said that although IS deems Africa and the Middle East as important ‘areas’ to know about for its production of knowledge, the relevance of IS's knowledge production is not equally valued by these ‘area’ scholarships.

International Affairs (IA), a more policy-focused journal is cited by journals from Chinese, post-Soviet, and Middle Eastern AS during 2014–16. Additionally, Conflict Studies journals are also cited by AS journals: JPR is cited by African, East Asian, East European, and post-Soviet journals, and JCR by China and African AS journals in 2014–16. However, neither JCR, nor JPR hold a citing or cited link to an AS journal in 1997–99.

The sole journal that could be said to represent ‘reflectivist’ or ‘European’ IR that was cited by more than one in 10 articles in an AS journal during 2014–16 is Security Dialogue (SD). During 1997–99, no ‘reflectivist’ or ‘European’ IR journals were cited by more than one in 20 articles in an AS journal. The low level of citation of ‘reflectivist’ and/or ‘European’ IR journals by AS journals suggests that there is little evidence of IR knowledge having been transferred from these journals to ‘area’ scholars.

Indeed, it is the US-based and rationalist WP, IO, and IS that have the most discernible citation influence on most, some and a few AS journals, respectively. At the same time, the citation networks suggest that there is no clear discernible distinction between US- and European-based AS journals in both their propensity to cite IR journals, or the regularity with which they are cited by IR journals.

Hence, as is discussed in detail in the next section, the citation network maps suggest that there is a clear divergence in whether IR journals act as suppliers of ‘theory’ to AS scholarship. Conversely, there is a much greater propensity among IR journals to cite AS journals on certain areas, but not others.

Discussion: the disciplinary-politics of knowledge-exchange between IR and AS

Citation analysis suggests that there is an exchange of knowledge between IR and AS. This exchange, however, is neither significant across the full spectrum of both disciplines, nor balanced: IR cites AS less than vice versa, in both periods under study. Indeed, citation exchange is strongly dependent on the IR journal and ‘area’ scholarship in question. Moreover, the strongest and weakest cases of IR–AS citation exchange divide along the main lines of distinction within disciplinary IR and AS, as set out above.

Notably, rationalist and US-based IR journals are more likely to be cited by AS scholarship, than reflectivist-orientated and European-based IR journals. The significantly greater rate at which AS journals cite WP, IS, and IO, in comparison with the other IR journals under study, suggests that the IR theory being consumed by AS is predominantly rationalist, either the neo-institutionalist perspectives common in IO and ISQ or the neorealist/realist frameworks in IS and SS. The flow of citations from IR into AS journals would thus seem to be at odds with those scholars that have posited that the interpretivist and qualitative nature of AS scholarship should find a more natural overlap and convergence with reflectivist European IR scholarship, rather than rationalist US scholarship.Footnote 121

This begs the question as to why? Citation analysis is unable to provide a substantive account of why certain journals cite one another and other do not, only that that they do. However, the conceptual framing of this paper and existent literature allows for some speculative explanation, based on the patterns that citation analysis brings to the surface.

What is notable about the difference between US-based and European-based IR journals is that the former tend to be considered as more prestigious and higher status. In this way, the preference for citing the former IR journals by AS scholars may possibly be attributed not to a coincidence of epistemological assumptions, but the disciplinary-politics of status with the academy. Rationalist US-based journals are both perceived by the wider scholarly community and ranked by citation metrics as the highest-status IR journals.Footnote 122 Within the disciplinary-politics of the academy, this means that the scholars of other disciplines will likely associate IR scholarship with these journals, almost exclusively. As such, this disciplinary-status acts as a further factor driving the universalization of rationalist and US-centric IR scholarship across other national academies,Footnote 123 as these most well-known journals are often cited symbolically to represent the whole of the IR discipline. Thus, although the more rationalist and large-N scholarship that is prevalent among some of the highest-ranked IR journals may be at odds with the more interpretative and cultural–contextual research ethos of AS, their social status as the most important and influential IR journals leads them to be cited more frequently by AS journals, than any other IR journals.Footnote 124

This interpretation emphasizes the performative power of academic hierarchies in general and their expression via the greater value attributed to theory development than other modes of knowledge production in particular. It, thus, suggests that epistemological and topical similarity may not be the only factor governing interdisciplinary exchange, at least in terms of the IR–AS relationship. The social hierarchy within, as well as between, disciplines is also an important consideration. In this way, although IR theory may hold greater exchange value than AS empirics, it is only IR theory with high-social standing that performs this role.

Conversely, the reciprocally low citation of AS journals by the highest status, rationalist and US-based IR theory journals is an indication that they do not consider AS scholarship as holding high enough disciplinary-status to regularly and substantially engage with its scholarship. According to the symbolic theory of citations,Footnote 125 citations, and especially interdisciplinary citations, may be interpreted as ‘concept-symbols’,Footnote 126 whereby the giving of an interdisciplinary citation represents an act of handwaving at a literature as a whole, without meaningful engagement with it. Thereby, the low-level of citation of AS journals by IR theory journals could suggest a form of symbolic handwaving at AS scholarship in general, rather than sustained engagement with it.

Indeed, another distinction evident in the paper's citation analysis is a difference between those rationalist and US journals citing AS as part of more substantive engagement and those potentially practicing symbolic handwaving at ‘area’ knowledge. The IR journals that most frequently cite AS scholarship tend to publish articles that are less focused on developing uniquely ‘IR’ theory and more concerned with solving empirical and conceptual puzzles, often via comparative case analysis. Indeed, WP is both the most frequent citer of AS scholarship and the journal that ‘most clearly integrates comparative politics scholarship with the subject matter more traditionally associated with international relations in the United States’.Footnote 127 This indicates a more sustained engagement between ‘comparative politics’-like approaches and ‘area’ scholarship, compared to more theory-driven IR journals.

Indeed, this distinction may also account for another dynamic within the citation maps. Conflict Studies journals cite AS journals more frequently than many of the more theory-driven IR journals, both rationalist and reflectivist. The articles in Conflict Studies journals are arguably more akin to those in Comparative Politics, than are the theory-driven IR journals. Articles in the former IR journals are often based on large-N studies using a comparative perspective, and which draw their empirics from datasets that include instances of conflicts, peace processes and mediation from across the globe.Footnote 128 By contrast, the articles in both ‘mainstream’ rationalist US IR theory and reflectivist-orientated IR scholarship tend to emphasize theoretical scholarship or favour single-case analysis. Hence, the cross-case worldwide perspective common to articles in Conflict Studies journals may lead to a wider range of ‘area’ scholarship being deemed relevant a priori knowledge, whereas US and European theory journals produce abstract knowledge that is drawn from, and which is only applied to cases in, the US and European context. In addition to WP and Conflict Studies journals, the third and fourth most frequent citers of AS scholarship, IA and SS, may also be regarded as less orientated towards the production of IR theory. These journals are more orientated to questions of contemporary policy analysis, and thus can be differentiated to the production of distinctive theoretical IR knowledge.

One possible interpretation of these citation patterns is that AS is perceived as a producer of empirical knowledge and that theory is held to be the more valuable academic ‘tradable good’. Following this logic, IR theorists seek to import theory as the more valuable good from the ‘master’ social sciences, viewing the knowledge produced by AS as less relevant to the production of IR theory and thus only ‘handwave’ at its literatures. Whereas more comparativist, ‘problem-orientated’ and policy IR scholarship is less concerned with producing ‘high-value’ theory knowledge, and is thus more open to substantive engagement with the knowledge produced by AS scholarship.

This interpretation, however, does not provide a satisfactory explanation as to why reflectivist and European-based IR journals are less likely to cite AS journals, than rationalist and US-based ones, albeit that neither cite AS scholarship to a significant extent. On the one hand, this could be seen as indicative of a greater inward-orientation and provincialism within European ‘reflectivist’ IR compared to US ‘rationalist’ IR. To a certain extent, this jars with the criticism outlined by some articles in these journals about the parochial nature of rationalist and US-centred knowledge production, including its neglect of the experience, worldviews, and standpoints of ‘other’ worlds of IR. It should be noted, however, that AS knowledge-production is, in most respects, vulnerable to the same epistemological, normative, perspectival, and core-periphery critiques of Eurocentrism, as those reflectivist IR scholars have expressed about rationalist IR. In this respect, reflectivist IR's lack of engagement with AS scholarship is consistent with such a critique. Nonetheless, AS scholarship does offer a resource on (non-Western) ‘areas’ that reflectivist and/or European-based IR knowledge production does not tend to draw on in informing their production of knowledge about the international. And, to this extent, the differing levels of engagement with AS scholarship between US and European IR scholarship seems to reinforce the epistemological and geoinstitutional dividing line between them.

With regards to the import of AS knowledge production into IR, the citation networks suggest that a different form of academic currency is at play in shaping which ‘area’ scholarships hold most value to IR. In general, IR journals are most likely to cite Chinese, Middle Eastern, and African AS journals. Conversely, articles from AS journals focused on East Asian (excluding China journals), Eastern Europe, Latin American and, to a lesser extent, post-Soviet AS are rarely cited by IR journals. IR's selective citation of ‘area’ scholarships seems to correlate with the claim by scholars that the visibility and status of different AS fields at any given time is directly related to their ‘area's’ geopolitical resonance, in terms of national and elite discourses in the USA and Europe.Footnote 129 Generalized narratives about both a ‘rising China’ and ‘rising Africa’, as well as a discourse of danger with respect to the ‘Middle East’ around the notion of Islamic terrorism and extremism, may partially account for IR journals greater citation of these AS publications. There were significant increases in the frequency that IR journals cited Chinese, African, and Middle Eastern AS journals between 1997–99 and 2014–16.

In this way, the extent to which IR engages with a particular ‘area’ scholarship is strongly influenced by whether it is an ‘area’ that is on trend, in much the same way that theories and theorists are considered as in and out of fashion. In other words, the contemporary relevance of an ‘area’ to wider elite and news discourses impacts IR's choice to engage with AS’ knowledge produced on this ‘area’. To this extent, the role of social status in terms of intra-disciplinary hierarchies and ‘impact factor’ ranking seems to be of less importance than the value of ‘geopolitical relevance’, as perceived by Western political elites and media. The result being that there are ‘area’ blind spots among those IR journals engaged with AS scholarship.

Conclusion

Taken as a whole, this paper's citation analysis of the IR–AS relationship conforms to wider characterizations of the academy as divided by strong social dynamics centred on the construct of the discipline, and the politics of relations between disciplines. It has been posited that IR's relationship to AS offers a different perspective on IR's interdisciplinarity, due to the presumed inverse hierarchical positionality of IR in this exchange as compared to that with the ‘master’ social sciences. The flow of citations between IR and AS journals indicates that the characterization of their interdisciplinary relationship as one in which IR is the dominant partner is a valid one.

IR's position as a net importer in its citation exchange relationship with AS chimes with accounts of disciplinary-politics that emphasize that (disciplinary) theoretical knowledge holds greater value than empirical knowledge in scholarly exchange.Footnote 130 However, this dynamic does not play out as a one-to-one exchange between two ‘black-boxed’ disciplines. IR and AS are both constituted by intradisciplinary divergences that lead to variations in the extents and reciprocity of the knowledge exchange between different IR and AS journals, within the wider context of the disciplinary-politics outlined above.

In spite of the widely-noted overlap in their objects of study, only distinct parts of IR make use of AS knowledge production to inform their analysis of the international. The main journals producing both rationalist and reflectivist IR theory do not cite AS scholarship on any ‘area’ with significant regularity. IR journals that are more orientated towards Comparative Politics approaches and policy analysis tend to cite AS scholarship more frequently. This further supports the existent literature that claims that the other social science disciplines perceive AS scholarship as not very relevant to their production of theory. Indeed, even in the case of less-theoretically orientated IR scholarship, the usage of AS scholarship is mostly restricted to knowledge produced on certain ‘areas’, leaving other significant ‘area’ blind spots. IR's interest in some areas over others correlates with wider perceptions about their geopolitical relevance.

In this way, the citation practice of IR journals indicates that those scholars that advocate a greater usage of AS scholarship to counteract IR's parochialism are correct in claiming that IR scholarship does not draw significantly on ‘area’ scholarship. Indeed, the most pointed critique has been that IR theory is presented as universal in composition and application, whereas in practice it has been constructed exclusively on US and European experience, assumptions and agendas. If citation is viewed as an acknowledgement of intellectual-debt, then IR theory is indeed built on the exclusion of (non-Western) academic knowledge production on, either all or most, other ‘areas’ of IR.

It is noteworthy that AS journals tend to cite some IR theory journals relatively frequently, in spite of their lack of reciprocal citation practice. AS scholarship is, however, selective in its practice of citing IR theory: US-orientated rationalist IR theory is cited much more frequently than Europe-orientated reflectivist IR theory. This confounds the expectation that there are more conducive epistemological, methodological, and topical grounds for engagement between AS's interpretivist approach and reflectivist IR scholarship. However, it reflects the role of status in the politics of exchange between disciplines, whereby those parts of a discipline seen as first-order or dominant – in the case of IR, US-orientated rationalist IR theory – are more likely to be cited by the scholars of other disciplines, than those parts seeking to challenge the mainstream of a discipline.

As the above highlights, IR–AS citation practice points to the exceptionalism of IR's knowledge exchange with AS vis-à-vis its other interdisciplinary relationships, in which it is second-order discipline. Some IR scholars express concern and insecurity about their discipline's lower-order status in its relationships to the ‘master’ social sciences and the way that the latter practices hierarchical interdisciplinary exchange. Nonetheless and in spite of AS scholarship being proclaimed as a natural dialogue partner for studying the ‘international’, most IR scholarship adopts the same dominant position and practices a similar mode of hierarchical exchange in its engagement with AS: exporting theory citations, but importing few area citations in return. This applies especially to IR theory scholarship, encompassing both US-orientated IR theory and its emphasis on IR's tight relationship to Political Science and Europe-orientated IR theory that considers IR as a more pluri-disciplinary field of study. In other words, most IR scholars of all persuasions, by and large, buy into the disciplinary framework in which theory-disciplinary knowledge is of a higher order than other forms of knowledge. In this way, the exchange of citations between IR and AS journals would suggest that the relationship between the two disciplines is governed more by considerations of disciplinary-politics, than an embrace of their overlapping subject matter.