Assyriological studies on food offerings have shown that meat played an important role in the banquet for the gods, although it is not clear what the practical or cultic reasons were which determined the choice of the animal to be sacrificed.Footnote 1 What is clear is that a large variety of meat was a common element of the god's and the king's meal, and that the presence of oxen, sheep and birds at the divine table represented whole animals, meat cuts, and meat-based dishes the participation of a part of the living world to the act of feeding the gods.Footnote 2 A reconsideration of Assyrian attestations concerning the meat offerings may help complement our knowledge of Assyrian food practices in a cultic context. Although, as Lambert observed, no specific term is used for meat offerings in Akkadian,Footnote 3 meat occurs in different ways in the ritual dynamics of Assyrian cultic ceremonies; accordingly, we shall study not only the types of meat offering employed in the rituals, but also the way in which they were prepared and presented to the Assyrian gods. In particular, we shall investigate the cooking procedure applied to meat offerings and the specific cultic occasions: culinary treatment is one of the most significant actions executed by the ritual performer on the victim's body in the sacrificial procedure,Footnote 4 although Mesopotamian thought was more interested in the act of presenting of the offering food to the god than in the actual processing of the victim's body.Footnote 5 Problems concerning the management, preparation and consumption of meat in the context of the temple cult and the sacrificial economy in first-millennium bce Mesopotamia have already been treated by scholars dealing with Neo- and Late Babylonian texts.Footnote 6 The study which follows will try to evaluate meat offerings in the temple cult in the light of the Neo-Assyrian sources.

The management of large amounts of meat, especially ovine and bovine meat, for religious ceremonies celebrated in the Temple of Aššur in Assur (modern Qal‘at Širqāṭ) was one of the main tasks for the central administration of the Assyrian State in its dealings with cultic affairs. Moreover, the territorial expansion and the administrative consolidation of the Assyrian State during the ninth–seventh centuries bce corresponded to an increase in the political and religious relevance of the Aššur Temple, for it was the seat of the national god of Assyria and the place where Assyrian kingship was periodically reaffirmed during state cult ceremonies. In the administrative documents of the royal archives of Nineveh (modern Qūyunǧiq) and in the Assur texts concerning royal rituals to be celebrated in the Aššur Temple, as well as in other sanctuaries, we find valuable information not only on the sacrificial animals destined for the temple ceremonies and the types of meat cuts, but also on the way meat entered the composition of the offerings and its culinary treatment for the gods’ meal.

Meat offerings in the Middle Assyrian period: the Assur and Kār-Tukultī-Ninurta records of sacrificial animals

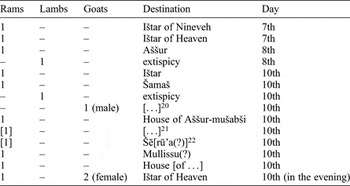

Sheep and calves were the animals regularly presented in Assyrian sacrifices.Footnote 7 This can be seen if we enlarge our inquiry to the Middle Assyrian texts from Assur and Kār-Tukultī-Ninurta (modern Tulūl al-‘Aqir). In Ninurta-tukul-Aššur's age (1133? bce), for instance, rams and goats were allocated to the temple offeringsFootnote 8 and to various rituals,Footnote 9 especially those involving purification.Footnote 10 Rams and goats also occur in a list of offerings to be presented on given days from the seventh to the tenth day of the month of Muḫur-ilāni to various deities and sanctuaries:Footnote 11 among these, there are male lambs (puḫādu) for the extispicy (ana bā’erûti) of the eighth and tenth days (see Table 1).Footnote 12

Table 1. Offerings from the seventh to the tenth days of Muḫur-ilāni

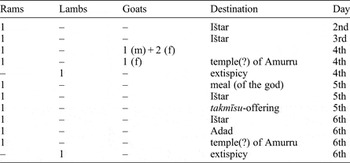

Another document records sheep allocated for the extispicy and as offerings to Ištar of the Heaven (Ištar ša šamê): for the diviner's activity of the 29th day of the month Ša-kēnāte is assigned one spring lamb (ḫurāpu),Footnote 13 while for the offering of the goddess of the first day of Muḫur-ilāni we have two rams and two young she-goats.Footnote 14 The same sacrificial animals, namely rams, goats and spring lambs (ḫurāpu), are attested in Table 2, referring to the offerings from the second to the sixth day of Muḫur-ilāni.Footnote 15

Table 2. Offerings from the second to the sixth day of Muḫur-ilāni

Sheep and goats for a divine banquet, perhaps to be celebrated in the temple of Sîn, are also recorded in a text from Tell Ṣabī Abyaḍ.Footnote 16 In documents coming from Urad-Šērū’a's archive and dealing with the assignment of sheep for various purposes there are also sheep for the cultic meal (tākultu) of Nineveh,Footnote 17 for the sacrifices before Nabû,Footnote 18 and for the pandugāni-ceremony.Footnote 19 In texts of this period we find very few details about the anatomic characteristics of the animals destined to be slaughtered in cult. In a prayer of Aššurnaṣirpal I’ to Ištar, for instance, we read about a calf with large horns which occurs in association with sheep as a sacrificial animal.Footnote 23 A fragmentary section of what probably represented a long Middle Assyrian ritual textFootnote 24 from Kār-Tukultī-Ninurta lists a number of sacrificial animals which were destined for various deities of the pantheon of Assur. Since the offerings are presented by the king himself,Footnote 25 it must have been a royal ritual. The group of animals includes a calf, which was assigned to Aššur and another god, perhaps to be identified with Mullissu,Footnote 26 and seven rams, each of which was assigned to pairs and groups of gods:Footnote 27 the divine recipients of such rams, whose names are preserved in the text, are Anu,Footnote 28 Bēr,Footnote 29 Nusku and Ninurta,Footnote 30 and two manifestations of the goddess Ištar, namely the Assyrian Ištar (Ištar aššurītu) and Ištar of Heaven (Ištar ša šamê).Footnote 31 Finally, the seventh ram is assigned to the gods, the divine Destinies (dŠīmāti), and the goddesses.Footnote 32 From this overview of the Middle Assyrian administrative texts, we can see that information on meat offerings is limited to the quantification of whole animals and their respective destination, while indications on meat cuts are absent, except for a few occurrences in a fragmentary account from Ṭābētu (modern Tall Ṭābān)Footnote 33 and a reference contained in a list of foodstuffs for a royal meal from Assur.Footnote 34 As we shall see in detail below, a different picture emerges if we move to the textual evidence of the first millennium imperial archives.

Meat offerings in the Neo-Assyrian cultic ceremonies at the Aššur temple

Meat offerings during the Šabāṭu-Addāru festive cycle

For the Neo-Assyrian period, we are able to combine the data provided in the Nineveh offering lists with those recorded in texts describing royal rituals celebrated in Assur on particular occasions during the Assyrian religious year. A special religious occasion was constituted by the festive cycle of the months Šabāṭu and Addāru in the Aššur Temple at Assur, which also included the quršu-ceremony of Mullissu.Footnote 35 The same cultic period seems to be referred to in the offerings of varieties of foods and beverages which are recorded in a group of administrative lists from the royal archives of Nineveh. From what we read in texts describing rituals in which the Assyrian king takes part as the principal cultic performer, we can reconstruct various moments of such a period of intense religious activity in Assur. On the 18th day of this month, the king enters the Temple of Aššur. Here, after performing several types of offering and purification ritual, he makes a libation and a funerary offering.Footnote 36 Then, a sheep offering is performed.Footnote 37 The offering, however, is not limited to sheep. Two calves were conducted into the area where the offering was presented, but the sacrifice of these animals is not mentioned in the text.Footnote 38 After that, the text continues by mentioning the offering of a calf horn, tendons or muscles of sheep, and combustible substances on the censers, followed by the burning of oil and honey.Footnote 39 A second stage of the ritual is held in the palace and in the chapel of Dagan at Aššur on the days following: here the animals are ranked and presented for the offering.Footnote 40 A similar text describes the rituals for the same days and shows that sheep sacrifice also occurred on 19thFootnote 41 and 20th days,Footnote 42 while on the 21st day the sacrificial animal is a calf: in fact, a calf for the chapel of Dagan is presented and inspected by the king in order to be sacrificed the next day before the god Aššur in the main Assyrian temple.Footnote 43 Another text reports on the rituals to be celebrated from the 23rd to the 25th day of Šabāṭu: the offerings concern the “regular offerings” (dariu) and the libations. The offering of meat, performed each day before Aššur and Mullissu, includes both (whole and uncooked) sheep and boiled meat (salqu).Footnote 44 In a fragmentary text, presumably related to Šabāṭu rituals, this type of offering is supplemented by the burning of a young she-goat (unīqu) and the opening of the ḫariu-vat.Footnote 45 For a tentative reconstruction of the sequence of the several moments characterizing these royal rituals, a report on the rituals of Šabāṭu and Addāru is of some help. According to this report, on the 18th day, after the entry of (the divine statues of) Šērū’a, Kippat-māti, and Tašmētu into the chapel of Dagan on the 16th day took place, meat offerings are presented on the censers by the king.Footnote 46 After that, offerings of sheep are given to various deities: Ninurta and Nusku, the gods of the “House of the God” (bēt ili), that is to say, the Aššur Temple, and the “Conquerors” (kāšidūti).Footnote 47 In another text referring to the rituals of Šabāṭu, the list of gods who receive the offerings of the 18th day also includes the “Golden Chariot” (mugirru ḫurāṣi), Bēl and Nabû.Footnote 48 Similar offerings must have been contemplated for other gods, too. We know, for instance, that such offerings were provided (on the 19th day?) in connection with the procession of the (statues of the) gods to the Anu temple;Footnote 49 on the 20th day, in the Aššur Temple in front of both Aššur and Mullissu and after Šērū’a and Kippat-māti have been seated at the “Gate of the Product of the Lands” (bāb ḫiṣib mātāti);Footnote 50 on the third day of Addāru, on the occasion of the installation of the god Aššur in his seat, after another divine procession to the sanctuary of Anu,Footnote 51 and on the eighth of the same month, concurrently with libations.Footnote 52 The offerings of the 20th and 23rd days of Šabāṭu and the third day of Addāru also include boiled meat.Footnote 53 The roasting of female goat-kids takes place on the third of Addāru and completes a similar offering of goats of the 23rd day of Šabāṭu,Footnote 54 as witnessed by a text cited above. On a day prior to the ninth of Addāru, which cannot be defined accurately because of a break in the text, the king's offering includes, as well as the sacrificial sheep, a bowl of soup (itqūru ša akussi).Footnote 55 In the Middle Assyrian coronation ritual, still in use in the Neo-Assyrian age, the regular offerings (dariāte) of meat concern one ox and six sheep for Aššur and four sheep to be distributed among other gods (Šērū’a, Nusku, Kippat-māti and Mullissu).Footnote 56 The same number of sacrificial animals which were assigned to Aššur also characterizes the offering for Marduk, while other deities receive a sheep each.Footnote 57 In this Middle Assyrian text we may observe that the offerings are composed of whole animals, presumably uncooked, and boiled meat (cuts). In fact, at a certain point in the ceremony, the king presents the tiara to the gods, which is destined to the god Aššur, and salqu.Footnote 58 Later, after having raised and placed the tiara of Aššur and the weapons of Mullissu on the throne, another sheep offering is executed.Footnote 59

Other contexts for meat offerings in the Aššur Temple: brazier rituals, Nisannu celebrations, rituals of Ištar and other royal rituals

The cooking of meat on censers and braziers is not limited to the royal rituals of the Šabāṭu-Addāru festive cycle. In another ritual, unfortunately in a fragmentary condition, the context of the ritual action is still that of the Aššur Temple.Footnote 60 Here, on the night of the 16th day of a month whose name is not indicated, on a brazier lit in front of the god (kanūnu ina pān Aššūr)Footnote 61 a ram is burned.Footnote 62 In Assyrian theological speculation, sacrificed animals are often equated with mythological figures and events. Thus, in a theological commentary, the ram thrown on the brazier which is lit before the goddess Mullissu is equated with the monster Qingu, the consort of Tiamat, while being devoured by the flames.Footnote 63 Similarly, another commentary identifies an ox and sheep, roasted and thrown to the ground, with Qingu and his seven children at the time of their defeat.Footnote 64 Another context in which meat offerings are used in royal rituals is the ritual of Nisannu at the bēt akīti. On the seventh and eighth days of the month, in addition to the regular offerings of sheep,Footnote 65 there is the presentation of boiled meatFootnote 66 and the roasting of a female goat-kid.Footnote 67 In one case, the setting for the sacrifice is a spring; here, the offering involves the pouring of the sacrificed animals’ blood into the spring, along with other liquids.Footnote 68 The blood as a libation liquid is also included later on in the ritual and is poured with water, beer, wine and milk on the heads of the offered sheep.Footnote 69 The presentation of an offering of sheep, boiled meat and roasted female goat-kids by the king is also required in the event of a dispatch from a military campaign arriving at Assur.Footnote 70 Instead, on the seventh day of Nisannu, the king sacrifices kimru-sheep both in front of the royal statue and in the temple of Adad.Footnote 71 From a text describing the arrangement of a series of offerings for a ritual, we learn that the kimru-sheep were heaped on the offertory table (ina muḫḫi paššūri).Footnote 72 It is interesting to observe that the Nineveh offering lists include this type of sheep among the offerings for the Aššur Temple.Footnote 73 The same kind of sheep offering is recorded in an account of sheep for the temple:Footnote 74 according to this document, the kimru-sheep were consigned on the tenth day and were part of a total offering of 23 sheep. In addition, sheep for the kimru-offering (immeru ana kimri) are mentioned in a decree of Adad-nerari III (810–783 bce) among contributions for regular offerings (ginû) in favour of the Aššur Temple from various cities of the country.Footnote 75 Therefore, it is clear that in the Neo-Assyrian period kimru refers to a type of offering and a sacrificial sheep. In this regard, it is interesting to draw attention to a Middle Assyrian list which mentions, among different kinds of raw foodstuffs and culinary preparations for offerings to the gods of Aššur, a culinary product called kimirtu. Like the Neo-Assyrian lists of offerings for the Aššur Temple, this list too mentions the saplišḫu-dish: both the kimirtu and the saplišḫu occur as the contents of kallu-bowls.Footnote 76 In administrative documents from Nineveh,Footnote 77 the saplišḫu occurs as a designation possibly referring to a type of offering to which the sheep were destinedFootnote 78 as well as a dish served in siḫḫāru-platters.Footnote 79 In any case, in the above-mentioned Aššur Temple offering lists the saplišḫu-dish is recorded at the end of the section concerning ovine meat and before that of birds,Footnote 80 or it is included within it.Footnote 81 The consumption of this dish, which we may define as a meat-based preparation,Footnote 82 is a characteristic of the royal banquet. Evidence for this is given, for the Middle Assyrian period, by the occurrence of the “saplišḫu of the king” in a Tell Billa fragmentary document dealing with sheep,Footnote 83 and by the 60 kallu-bowls of such a dish which, as we learn from an Assur list, were served on the occasion of an analogous palatine ceremony.Footnote 84 As regards the Middle Assyrian term kimirtu, it could reasonably refer to a meat-based preparation resulting from the sacrificial sheep which in Late Assyrian times were denoted by the term kimru.Footnote 85

Returning to the text of the rituals of the akītu-temple in Nisannu, we observe that the offering of boiled meat may be accompanied by the strewing of salt on it: this is required for the offering of the 20th day before Bēlat-dunāni.Footnote 86 The action of strewing salt on the silqu-meat before this goddess is also registered in a text containing ritual instructions for Assyrian temples.Footnote 87 Differently, a text for the ritual dedicated to the “Lady of the Mountain” (Šarrat-šadê), an aspect of the goddess Ištar, refers to the strewing of salt on a cut of rib (ṣēlu) to be presented in front of the god Sibitti.Footnote 88 In addition to salt, the meat offered could also be strewn with flour. This is documented in a Middle Assyrian ritual, according to which the king had to scatter the content of three kallu-bowls filled with maṣḫatu-flour on the sacrificial lamb (ina muḫḫi puḫādi).Footnote 89

Rituals of Ištar of the bēt ēqi also include the supply of meat for combustion offerings. Apart from goats,Footnote 90 the burning offering also includes cuts of meat (nisḫu) on the censers.Footnote 91 The text also mentions a brazier,Footnote 92 probably used for the combustion of the offered meat. The offering includes “hot boiled meat” (silqu ḫanṭu)Footnote 93 and two bulls.Footnote 94 It is evident that from these bulls were extracted the meat cuts needed for the offerings, but the text is unclear at this point.Footnote 95 To these rituals of the bēt ēqi were destined also the 26 ēqūtu-sheep mentioned in an administrative document from Nineveh relating to meat offerings entering the composition of dishes for royal banquets:Footnote 96 the 26 sheep in question derived from the burnt offerings which presumably took place in the bēt ēqi. We find additional evidence for hot boiled meat in a Nimrud report on cultic events which took place in the Aššur Temple during the eponymate of Issār-dūri, governor of Arrapḫa (modern Kirkuk) in 714 bce.Footnote 97 According to this document, the sacrificial ram which was slaughtered on the altar (iābilu naksu ša muḫḫi maškitte), once submitted to the god was to be thrown into the river.Footnote 98 At the beginning of the text there are references to animals, probably to be identified as rams, which were transported in large carts (qirsī dannūti) from the governor's residence to the place of sacrifice and slaughtered on the altar on the 21st day of a month whose name is not preserved in the text.Footnote 99 Interestingly, we are also informed about the transport of sacrificial animals through two Nineveh offering lists: these texts show that the transport of offerings for the temple in Assur was made by means of chariots (mugirru).Footnote 100 Of the meat presented in the ceremony, the boiled meat offered to Šamaš is assigned to the royal scribe,Footnote 101 while the intestines constitute the cook's allowance.Footnote 102 The practice of throwing previously offered meat cuts to bodies of water is also documented in iconography: one of the bronze bands of the gates of the temple of Imgur-Ellil (modern Balawāt) shows an offering scene which appears to be associated to the installation of a stele in one of the mountain regions reached by Shalmaneser III (858–824 bce) during his campaigns.Footnote 103 The long procession of people taking part in the ceremony includes a priest who takes two calves and four rams to the place of sacrifice. The actual action of sacrifice is not illustrated,Footnote 104 but we see that two soldiers are depicted in the act of throwing some meat cuts resulting from the sacrifice of the calves and the sheep to the fish and a strange creature of Lake Urmia.

It is well known that the sacrifice of ovines was common practice in Assyrian royal rituals. To quote just a few additional instances, sheep offerings were performed before Nabû, Bēlat-šarri, Bēr, Uraš and Kutatāti in the temple of the Assyrian Ištar in Nisannu;Footnote 105 in a victory ritual involving the triumphal entry of the king into the camp and the qirsu place;Footnote 106 in the nāṭu-ritual for Ištar, during which the sheep offering for Aššur is accompanied by the feeding of the ṣīpu before the goddess or the bed (maiālu);Footnote 107 and in the tākultu-ritual performed by the king before the stars.Footnote 108 Sacrificial sheep were also presented on the occasion of ritual ablutions. In one text we find a description of a ritual bath (rinku);Footnote 109 once the ablution is performed, a sheep is sacrificed.Footnote 110 Although this text designates the sacrificial sheep with the term niqiu, “sacrifice, offering”, it is reasonable to think that they are to be identified with the ablution sheep (immeru rimku) of the Aššur Temple offering lists.Footnote 111 However, no indications can be found concerning the sacrifice of pigs, if we exclude a reference in the composition called “the Marduk Ordeal”. According to this text, which would, however, reflect Babylonian religious practices,Footnote 112 a pig was slaughtered before the “Lady of Babylon” (Bēlet Bābili) on the eigth day of Nisannu.Footnote 113 In the same text, marinated roasted meat (šubê labakti) was presented to Bēl.Footnote 114

Culinary treatment, presentation, and manipulation of the sacrificial meat

The relationship between cooking procedures and recipients of the offerings: boiled and roasted meat cuts

Some attestations in Assyrian ritual texts show that a distinction between different ways of cooking sacrificial meat (salāqu, “to boil”,Footnote 115vs. šamû, “to roast”Footnote 116) was at work in cultic practice. Further, this custom was deep-rooted in other religious traditions of the Ancient Near East. In Anatolia, for instance, sacrificial meat cuts were offered by boiling them in a pot or by roasting them with direct exposure to the fire.Footnote 117 Unlike Assyrian texts, Hittite texts specify which meat cuts were usually boiled and which were roasted.Footnote 118 In this regard, it has been suggested that the cooking procedure was probably determined by the anatomic nature of the meat cuts,Footnote 119 but a look at Assyrian religious evidence shows that the destination of the meat offering was a decisive element in choosing the appropriate cooking procedure in the majority of cases. In rituals for Ištar, for example, the offering of meat differs according to the recipients: boiled meat (silqu/salqu) is presented to Aššur, while roasted meat (šubê/šumê) is placed in front of IštarFootnote 120 or another female deity (e.g. Šarrat-šadê).Footnote 121 In the nāṭu-ritual for Kulili (or Kulittu?),Footnote 122 the king's offering is executed in the “bedroom”Footnote 123 and consists not only of sheep, but also boiled and roasted meat cuts; the boiled meat is for Aššur, the roasted meat for Ištar and the bed.Footnote 124 In the preceding lines of the same passage, the bed is mentioned as the place in front of which the king feeds the ṣīpu, presumably through the meat of the sheep offered.Footnote 125 The bed as the place of rituals occurs in another text concerning the cult of Ištar,Footnote 126 as well as in a text describing a ritual for the “Daughter of the River” (Mar'at nāri).Footnote 127 It is not clear what was indicated by the word ṣīpu,Footnote 128 but we cannot rule out the possibility that it is a divinized object which needed to be fed and honoured by the presentation of offerings. From what we see from the rituals for Ištar, the feeding of the ṣīpu takes place before the goddessFootnote 129 or the bed.Footnote 130 In Mesopotamia, beds of the gods were considered divine entities themselves, since they form a part of the nature of the divine couple with which they are associated. Some temples had special rooms equipped with beds for divine couples, as in the case of the “bedroom” (bēt erši) of Nabû and Tašmētu in the Nabû temple at Kalḫu (modern Nimrud). An Urdu-Nabû's letter reminds the king of the entry of Nabû and Tašmētu into the bedroom on the fourth day of Ayyāru, and the offerings to be performed in that place.Footnote 131 It is possible that the food substances that the author of this letter intends to bring to the bedroomFootnote 132 and present as offerings for the ritual of the sacred marriage for the benefit of members of the king's family were destined not only for the divine couple, but also for the actual bed of the two gods. Moreover, during Middle and Neo-Assyrian times the Ancient Mesopotamian custom of the creation and donation of beds to the gods from the kings is well attested in Assyria, as witnessed by the donation of beds from Aššurnaṣirpal I to Ištar, Sennacherib to Aššur, and Assurbanipal to Marduk.Footnote 133 That the beds of the gods were considered to be divine in nature, and that they should be honoured with the food offerings which were commonly destined to the gods is also evident from a letter of Ṭāb-šār-Aššur to Sargon II, in which the state treasurer informs the king of the execution of regular offerings (dariu) of sheep in front of a bed belonging to a Babylonian god which he was transporting by river in the direction of Assur.Footnote 134

Returning to the distinction of the meat offered according to the type of cooking, what we observed above about the offering of roasted meat to Ištar in the ritual for Ištar and Kulili is confirmed in an administrative text from Nineveh, where meat cuts destined for several deities are enumerated. From the preserved lines of the tablet, we see that the roasted meat was destined for Ištar, while the (raw or boiled?) breast was the part due to Aššur, Mullissu and another deity.Footnote 135 Instead, the data provided by the Nineveh lists of offerings for the Šabāṭu-Addāru cultic period show a different picture, since the rēšāti offerings also included breasts (irtu) of roasted sheep.Footnote 136 In the ritual for Ištar and Kulili, the opposition is not only between boiled meat and roasted meat, but also between boiled meat, presumably intended for Assur, and the rib cut (ṣēlu).Footnote 137 If the parallel with the salqu vs. šubê opposition is accepted, the rib cut too, which we suppose to have been the offering for the goddess, was probably treated through roasting procedure.

In a second moment of the ritual, we see another case of manipulation of the offering meat. The offering of roasted meat made by the king consists of the front part of a neck cut (pānāt kišādi), that the king pierces with an iron knife and offers to Lisikutu, while the singer intones the cultic song “Let them eat the roasted meat, the roasted meat, the roasted meat!”.Footnote 138 The animal from which this cut derived is not stated in the text. From a schedule for the distribution of offered meat cuts, we see that the front part of the neck was a cut of bovine meat,Footnote 139 but a list enumerating qinnītu-offerings of the queen for the month of Du’ūzu informs us that the god (Li)sikutu received both calves and sheep.Footnote 140 After the feeding of Lisikutu, the king throws the pierced neck cut into a pit (apu),Footnote 141 where he had previously poured blood, honey, oil, beer, and wine.Footnote 142 The ritual also requires the presentation of a francolin (tatidūtu),Footnote 143 but it is not clear whether it entered the composition of the offerings or, alternatively, the meal which was served to the king on the occasion of this ritual.Footnote 144 The last offering of meat with which the king feeds Lisikutu, consists of a foreleg (durā’u), presumably of a sheep. This meat cut is presented to the god upon the bread on the table.Footnote 145 In this case, the offering is accompanied by a song; when the song reaches its conclusion, the king lifts the meat cut, throws it into the pit, and pours libation liquids on it.Footnote 146 In another ritual for Ištar, the offering of meat to the goddess requires the presentation of specific meat cuts upon the ḫuḫḫurtu-bread, namely the head, the feet and the shoulder,Footnote 147 in all likelihood taken from the sacrificed sheep.Footnote 148 Other cuts offered derive from ribs,Footnote 149 nine of which are cut and placed upon the terrace,Footnote 150 roasted meat,Footnote 151 and fetlocks (kursinnu).Footnote 152 The practice of presenting meat upon bread characterizes other Assyrian rituals, as we shall see below. In the ritual for the “Lady of the Mountain”, two rams are sacrificed, one to Aššur(?), the other to the “Lady of the Mountain”.Footnote 153 Then, meat is distributed depending on the type of cooking: the boiled meat to Aššur, the roasted to the goddess.Footnote 154 In this case, however, the goddess also receives boiled meat.Footnote 155 As regards boiled meat, it is interesting to note that a text concerning a ritual for the singers mentions the offering of salqāni:Footnote 156 the plural form is never used with the term silqu/salqu and in this case the single cuts of the boiled meat were certainly intended by salqāni. In both the ritual for the Šarrat-šadê and that for Ištar discussed above, the meat offering consists of the presentation of ribs on the terrace: in fact, a rib is placed in this place before the god Sibitti.Footnote 157 It is useful to remind readers that in one of the prophetic texts relating to Aššur's covenant with Esarhaddon, the offering for the gods consists of a cut or a slice placed on the terrace located immediately outside the cellar of Aššur.Footnote 158 Although the name of the substance appears broken on the tablet, the association of ḫirṣu with the terrace leads us to suppose that with the term ḫirṣu we mean a type of meat cut which was analogous to those reported in the rituals cited above. Other attestations about the offering of ribs along with other meat cuts may be found in the ritual for the “Daughter of the River”, in which the penitent(?) (bēl palluḫi)Footnote 159 presents boiled meat, a left shoulder (šumēlu), and a rib.Footnote 160

A few texts mention another kind of meat offering called qiršu: this designation indicated a type of meat cut and an offering.Footnote 161 According to a ritual text for singers, it was served in kallu-bowls.Footnote 162 The offering of qiršu, a small amount corresponding to three litres, is mentioned along with sheep meat in Adad-nerari III's decree in favour of the Aššur Temple: the association with sheep seems to indicate that the qiršu was a cut of sheep meat.Footnote 163 Another occurrence of the word is attested in a fragmentary list of offerings which also mentions mutton.Footnote 164 For the offering of qiršu, kallu-containers were used as well as the kappu-bowls, as is evident from an inventory text from Nimrud listing vessels and utensils for cultic use.Footnote 165 It is interesting to observe that in this text the kappu-bowls are also associated with generic meat cuts (nisḫāni).Footnote 166

Another interesting example of the offering of roasted meat may be found in the ceremony for the banquet of Gula. The first meat offering of the ritual consists of a grilled ram (iābilu gabbubu), which was placed on a basket of oil-bread on an offertory table.Footnote 167 Unlike the other attestations of roasted meat, here the term used to qualify the ram is not šubê, but gabbubu. The word occurs only in association with sheep meat and is generally connected to the verb gabbubu, “to grill” (D), which is derived from g/kabābu “to burn” (G).Footnote 168 In the offering lists from Nineveh, the term used to designate the roasted meat of sheep is always šubê, not gabbubu. The attestations of the word gabbubu in administrative texts of the Neo-Assyrian age appear to be limited to three lists of foods, two of which concern dishes served in palatine banquets, while the third one lists food contributions delivered by state officials for temple offerings. In all of these attestations, the designation gabbubu occurs in sections dealing with ovine meat.Footnote 169 The animals slaughtered for the divine banquet are one ox and three rams,Footnote 170 but the entire meat offering comprises four spring lambs and five ducks (iṣṣūru rabiu) which had to be presented along with bread, cakes and fruit in the Gula temple in the morning.Footnote 171 Finally, another culinary preparation which is mentioned in the ritual consists of parched grain which had to be added to the bouillon (mê-šīri).Footnote 172 In another text concerning the arrangement of a ritual, the offering consists of roasted meatFootnote 173 and one kimru-sheep.Footnote 174 The ceremony also requires a combustion offering, but the animal to be sacrificed varies according to the social status of the donor: in case of a prince, the offering consists of a turtledove (sukanninu), in case of a poor man it is limited to the heart of a ram (libbi iābili).Footnote 175

Birds in meat offerings

The evidence presented above clearly shows that the meat offerings for Assyrian cultic practice consisted principally of sheep and calves. However, birds (geese, ducks and turtledoves) are also recorded in the Nineveh lists of offerings for the Aššur Temple.Footnote 176 A further list of offerings, probably of Neo-Assyrian origin,Footnote 177 confirms this. The meat offering consists of birds, sheep and bulls;Footnote 178 these animals were assigned to various deities according to the schema shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Distribution of various sacrificial animals among deities

Unlike the divine couple Nabû and Tašmētu, all gods received birds as offerings; the gods Bēr, Bēl-šarri, Ištar of Arbela, Bēlet-balāṭi, Šamaš, Bēlet-parṣē and Bānītu receive one bird each. The obverse of the tablet is only partly readable, but we presume that other birds were listed in this part of the text, since the total given on the reverse corresponds to fifteen birds.Footnote 179 This total includes the four(?) birds presumably destined for Mullissu.

Boiled and roasted cuts, meat with bread, and meat-based soups: types of cuts and occasions of ritual consumption

The picture concerning meat offerings of the Neo-Assyrian period may be completed by the data provided from a long record of ritual practices and offerings, possibly dating back to the reign of Assurbanipal (668–631? bce).Footnote 180 On the 13th day of Ayyāru, the king performed sheep sacrifices, presented boiled meat and a fattened sheep (takbāru), and burned a young she-goat.Footnote 181 After a ritual song, two neck cuts (of the sacrificed sheep) are placed on the bread offered.Footnote 182 The mention of takbāru-sheep in the context of the akītu-celebrations shows that the sacrifice of such a category of ovines was not limited to the Šabāṭu-Addāru offerings.Footnote 183 The association of cooked meat and bread requires some consideration. The meat cuts which were presented along with bread in Assyrian ritual practice are: the forelegs;Footnote 184 the head and the feet;Footnote 185 the shoulder, the head and the feet;Footnote 186 neck cuts (of sheep);Footnote 187 and unspecified cuts of sheep.Footnote 188 The bread used in the case of the offering of head, feet, shoulder and for ovine meat in general is the ḫuḫḫurtu variety.Footnote 189 To these attestations we may also add one referring to a grilled ram placed in a basket containing loaves of oil-bread (aklī ša šamni).Footnote 190 This way of presenting cooked meat parts may also have characterized the secular meals commonly served in the palatine banquets.Footnote 191 Evidence for the association of bread with cooked meat may also be found in Middle Assyrian texts: a document recording amounts of wheat bread, some of which appear to be associated to temple offerings, explicitly mentions a quantity of bread in connection with boiled meat (ana salqi).Footnote 192 Further evidence may be found on the iconographical level. In a scene of the relief D, room S’, of the North Palace in Nineveh we see Assurbanipal in the act of libating over some lions killed during a royal hunt.Footnote 193 The food offering requires the presentation of flat bread and meat cuts on a table. According to the interpretations of the scholars, the meat cuts, which are contained in a large flat-based bowl, are to be identified with a shoulder, fatty tissue and roasted meat,Footnote 194 or with the jaw and the leg of a ram.Footnote 195 The representation of a ram's meat cut on a bundle of flatbread may be observed in a relief from Nineveh from the age of Sennacherib.Footnote 196

Let us now return to our record of religious practices and offerings. This text records the queries addressed to the god and the relevant responses about the execution of given ritual actions. Regarding the offering of calves and sheep on the brazier of the Aššur Temple, to be performed along with the sheep offerings of the months of Šabāṭu and Addāru, the response to the query is not favourable and, consequently, this meat has to be presented in the offering of the evening with the boiled meat.Footnote 197 A different query, not preserved in the text, must be intended in a passage concerning the presentation to Aššur of an ox tail which had not been submerged (lā ṣīpu) in the bouillon, and which was presumably prepared in a temple cauldron.Footnote 198 Other queries concern various (meat-based?) culinary preparations, as well as the burnt offerings on the censers of Aššur, Mullissu, and Šērū’a.Footnote 199 Unlike what we observed above on boiled meat destined for Aššur, the goddess Šērū’a too could receive the offering of salqu.Footnote 200 Another extispicy, whose response is favourable, concerns the omission of the offering of boiled meat from sacrifices made by the king.Footnote 201 A section of the text is devoted to the treatment of the censers used in celebrations in the akītu-temple.Footnote 202 The censers in question are those of Aššur, Mullissu, Šērū’a, Sîn, Šamaš, Anu and Adad. The disposition of the censers is precisely regulated: the censer of Mullissu goes in front of that of Aššur, that of Šērū’a beside that of Mullissu, and those of the other gods behind the fumigation censer of Aššur.Footnote 203 Only for the god Aššur are two censers used: one for roasting meat cuts (nisḫāni) and the other for burning aromatic substances.Footnote 204 The final section of the text includes a list of foods used as offerings. As far as meat is concerned, the list mentions the intestines, the stomach, the liver, the qarrurtu-organ, the head of a bull, bull tail joints and other cuts.Footnote 205 These meat parts are qualified at the end of the list as being “whole (offerings) of the king's sons”.Footnote 206 Another meat offering, consisting of five cuts of ovine meat,Footnote 207 follows the listing part dealing with the offerings for the quršu of Mullissu. The presence of the internal organs of a bull, e.g. stomach and liver, also characterizes the composition of the rēšāti-offerings recorded in the Nineveh offering lists.Footnote 208 Further, both this record of religious practices and offerings and the Nineveh offering lists document the quršu-ceremony of the goddess Mullissu. At the end of the account of religious events, it mentions another important moment in the festive cycle of the eleventh and twelfth months of the Assyrian religious year: the entry of the god Aššur into the chapel of Dagan on the twenty-second day of Šabāṭu, and that of the chariot of the supreme Assyrian god on the following day.Footnote 209 These two days are an integral part of the celebrations of the 22nd–26th days of Šabāṭu, during which the god Aššur visited the chapel of Dagan.Footnote 210 The 23rd day coincides with the event known as the “releasing of the feet” (pašār ša šēpē). Although the significance of this event in the frame of the Šabāṭu-Addāru celebrations is not understood, it is important to note that the same expression is used in Nergal-šarrāni's letter about the celebration of the sacred marriage of Nabû and Tašmētu. From the words of Nergal-šarrāni to the king we learn that on the eleventh day of Ayyāru the god Nabû left his bedchamber and stretched his legs in order to go to the game park to hunt wild oxen.Footnote 211 In all probability, this event corresponded to the “race of Nabû” (lismu ša Nabû) mentioned in a hymn of blessing for the city of Assur.Footnote 212 A similar exiting the bedchamber, with analogous stretching of the legs and subsequent royal hunt, must also have taken place in Šabāṭu: in fact, we know that the celebration of the quršu of Mullissu in Assur in the same month, and that of the sacred marriage of Nabû and his divine spouse in the Nabû temple of Kalḫu in Ayyāru were strictly connected. These two events served to establish the kingship and transfer the gods’ favour and support to the Assyrian king.Footnote 213 A text similar to that discussed aboveFootnote 214 describes the entry of Aššur's chariot into the akītu-temple. The event takes place on the second day of Nisannu and comprises an offering of boiled meat to Aššur from the king and the entry of the chariot into the sanctuary, along with ritual songs, sacrifices and processions of (the statues of) the gods.Footnote 215 A second important moment described in the text concerns the quršu of Mullissu: more precisely, it mentions a bed and seven gods who visit the chapel of Dagan on the 22nd day of Šabāṭu.Footnote 216 It seems that for each of the days of this period of celebration a calf (būru) and a spring lamb (ḫurāpu) were sacrificed.Footnote 217 The sacrifice of an animal per day may be evaluated in the light of the Aššur Temple offerings of the Nineveh lists, according to which the offerings for the chapel of Dagan for the 4th, 22nd, 24th, and 25th days (of Šabāṭu) required the presentation of one ox per day; from this ox two cuts of shoulder were then taken.Footnote 218 On the same days the thigh (pēmu), the shoulder (imittu), and outer cuts (nisḫāni) of an unspecified number of other oxen were also presented.Footnote 219 On the occasion of the quršu-ceremony of Mullissu the offering also required one ox per day; this can be seen in the case of the 22nd and subsequent days of the month.Footnote 220 On the same days, Mullissu also received the offering of a whole sheep (immeru šalmu) per day.Footnote 221 Finally, the duplicate of the above-mentioned record of cultic events and offerings includes the description of a series of sacrifices, regular offerings (dariu), and divine processions which were accompanied by kettledrums.Footnote 222 At the end of the singing part of the ceremony, an offering of boiled meat was made at the Aššur Temple.Footnote 223 In addition, much of the meat destined for temple offerings was converted into culinary preparations of liquid consistency, such as soups and bouillons. We know, for example, that soups which were served at the divine meal on the occasion of the wedding night of Šarrat-nipḫa at Assur were prepared by adding boiled meat and the uncooked wings of an unknown bird (goose, duck, or turtledove?) to a cauldron.Footnote 224 Soups and bouillons, which are documented in some of the royal rituals discussed above, were also peculiar to the temple offerings of the Middle Assyrian period. In fact, in an Assur list cited above, which enumerates various foods for the Assyrian gods, there are also kallu-bowls holding ukultu, the equivalent of the akussu-preparation of some centuries later.Footnote 225 This substance is mentioned in sections of the text dealing with different culinary products, among which we also find the saplišḫu-dish discussed above.Footnote 226 The names of the gods who received the saplišḫu-dish and the ukultu-soup are not preserved, except for that of the goddess Šērū’a.Footnote 227 In any case, the association of the two substances, namely the soup and the saplišḫu, must have been a peculiarity to the divine meal, since they also occur together in a cultic text of the Late Assyrian period.Footnote 228

Conclusion

From our investigation of meat offerings in Assyrian state religion we observe that details of meat cuts are poorly represented in the Middle Assyrian evidence. However, from later texts we can form a more complete idea on the sacrificial animals and the various meat cuts which composed the god's meal. The most interesting element to emerge from the analysis concerns the differentiation in the cooking procedure (boiling vs. roasting) of the sacrificial meat in relationship to the divine recipient. After slaughter, the parts into which the sacrificial animal was cut were processed differently. Where more gods are involved, boiled meat is destined for Aššur (and other deities), while roasted parts go to Ištar (or to her manifestations). Roasting, carried out on braziers or censers, usually applied to young she-goats, rams, and various cuts, generally of ovine meat. However, we note that boiled meat was not presented exclusively to male deities, since it was also offered to Gula, Šērū’a and the “Lady of the Mountain”. We do not know which religious concepts formed the basis of such a differentiation in cooking method, but it suffices here to say that the different treatment of the sacrificial meat was a factor in cases where there was the presence of a plurality of gods at the divine meal; in addition, it seems that the female character (of the goddess receiving the roasted offering and the animal which was roasted) seems to have played a role, albeit not in every ritual context: in the ritual of the bēt ēqi at least, we have observed that young she-goats for the goddess were regularly roasted on censers. Offerings of goat-kids are also attested in the royal rituals of Šabāṭu-Addāru and Nisannu, but the broken parts of the texts do not allow us to learn more about the divine recipients. Interestingly, elements which are peculiar to the goddess were associated with the offering of roasted meat, as witnessed by the offering performed in front of the bed. This differentiation of cooking method probably functioned also on a redistributive level: in light of roasted meats being mentioned among the cuts assigned as prebends to the priest of Šarrat-nipḫa and the priest of the bēt ēqi in an Assyrian decree for the temple of Šarrat-nipḫa,Footnote 229 we may suppose that the difference in cooking procedure was strictly linked to the hierarchical system governing the redistribution of sacrificial meat cuts among the temple personnel and other people taking part in the ceremony. In addition, it is known that roasted meat deriving from the sheep offerings presented in Assur was then incorporated, in the form of “leftovers”, into the royal meals in Nineveh.Footnote 230 The second point of interest concerns the presentation of the offering meat on bread: this way of presenting meat to the god included pieces of ovine meat (head, neck cuts, shoulder, forelegs, feet and unspecified cuts). Interestingly, no hint is given in the texts on the culinary treatment of these pieces, but it is clear that both types of offerings, i.e. the meat and the bread, consisted of products that required human activity in preparation for consumption; in fact, the slaughtering and butchering of the animal may be considered the equivalent of processing cereals into bread.

Abbreviations

Abbreviations not included in this list follow Wolfram von Soden. 1965. Akkadisches Handwörterbuch. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

AEAD = Simo Parpola and Robert M. Whiting. 2007. Assyrian–English–Assyrian Dictionary. Helsinki and Winona Lake: The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project.

CDA = Jeremy Black, Andrew George, and Nicholas Postgate. 20002. A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian. (Santag. Arbeiten und Untersuchungen zur Keilschriftkunde 5.) Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

MARV I = Helmut Freydank. 1976. Mittelassyrische Rechtsurkunden und Verwaltungstexte, I. Vorderasiatische Schriftdenkmäler der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin 19, Neue Folge 3. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

MARV II = Helmut Freydank. 1982. Mittelassyrische Rechtsurkunden und Verwaltungstexte, II. Vorderasiatische Schriftdenkmäler der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin 21, Neue Folge 5. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

MARV III = Helmut Freydank. 1994. Mittelassyrische Rechtsurkunden und Verwaltungstexte, III. Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 92. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag.

MARV IV = Helmut Freydank and Claudia Fischer. 2001. Mittelassyrische Rechtsurkunden und Verwaltungstexte, IV: Tafeln aus Kār-Tukultī-Ninurta. Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 99. Saarbrücken: Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag.

SAA 3 = Alasdair Livingstone. 1989. Court Poetry and Literary Miscellanea. State Archives of Assyria 3. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

SAA 7 = Frederick M. Fales and J. Nicholas Postgate. 1992. Imperial Administrative Records, Part I: Palace and Temple Administration. State Archives of Assyria 7. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

SAA 9 = Simo Parpola. 1997. Assyrian Prophecies. State Archives of Assyria 9. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

SAA 11 = Frederick M. Fales and J. Nicholas Postgate. 1995. Imperial Administrative Records, Part II: Provincial and Military Administration. State Archives of Assyria 11. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

SAA 12 = Laura Kataja and Robert Whiting. 1995. Grants, Decrees and Gifts of the Neo-Assyrian Period. State Archives of Assyria 12. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

SAA 13 = Steven W. Cole and Peter Machinist. 1998. Letters from Priests to the Kings Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal. State Archives of Assyria 13. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.