Notebooks written by students at the Litchfield Law School are among the primary sources for understanding the influence of English law in this country. The notebooks provide rich documentation of how the common law and elements of English law were presented, explained, and compared with American law in a formal classroom setting during the Early Republic. The digitization project described here, the first large-scale digitization initiative undertaken at the Lillian Goldman Law Library at Yale Law School, with the cooperation of the Litchfield Historical Society, is intended to organize, describe, and analyze those notebooks with a web site containing a database, bibliography, inventory, and links to images. The Litchfield student notebook project was intended not only to create digital surrogates of important historical sources, but also to inform future digital legal history projects at the Lillian Goldman Law Library.

One of the most impressive facts about these notebooks is the number that have survived. During the 59 years (1774–1833) that Tapping Reeve and James Gould were lecturing their students—there are more than 900 men on the list of students at the Litchfield Historical Society web site—280 volumes are known, representing the efforts, mostly diligent, but occasionally erratic, of approximately 80 students. The earliest notebooks date from 1790, the latest from 1830. In most cases, a student will have filled more than one notebook. The notebooks are densely packed with information. In addition to lectures by Reeve and Gould, there are citations to English reports, essays by Reeve, references to English treatises, tables of comparison, illustrative examples of the workings of the law of descent, legal maxims, questions for debate in Moot Hall, comments on a Connecticut case that went to the Supreme Court, notes on attendance at the court in Litchfield, digressions on English history, anecdotes, and doggerel. Two determined students drew up useful charts, one of the reigns of kings of England, beginning with Egbert in 827, the other a chronological chart of reporters of cases adjudged in the courts of law and equity in England.

There are numerous difficulties, however; first in locating the notebooks, and second in finding information on specific topics within these manuscript notes. The surviving notebooks are known to be held in thirty-six different repositories, with the largest collections at Yale, Harvard, and the Litchfield Historical Society. University libraries, state libraries, and local historical societies hold the remainder. Although there have been many attempts to list and describe notebooks in the past, no list has been comprehensive, and, with the discovery of more notebooks, previous bibliographies are out of date. The second difficulty stems from internal organization of contents. Students took notes for their own use and often failed to provide the usual guides one expects, such as topical headers, tables of contents, subject indexes, and even page numbers. Some students recorded whether Reeve or Gould was lecturer, along with the date, whereas others would omit those important details. Without organizational cues, it requires much effort to seek and find lectures on a certain legal title. The difficulty is compounded by scattered locations of notebooks. Three valuable early notebooks all dating from 1794 are in three different libraries: the Connecticut State Library in Hartford, the New York State Library in Albany, and the Ingram Library of the Litchfield Historical Society. It is nearly impossible to make meaningful comparisons of these items when the most desirable solution is to view them side by side.

The authors of this article, with the support of John Langbein, Sterling Professor Emeritus of Law and Legal History and Professorial Lecturer in Law at Yale Law School, and the William Nelson Cromwell Foundation, have spent the past 3 years engaged in a project to work through the complexity of locating, describing, and making accessible the Litchfield notebooks. We have found that the most important component to making these resources available to researchers is metadata. Metadata (literally data about data) is crucial in making historical collections accessible in both print and digital formats.

The purpose of this article is to introduce readers to some of the considerations required to make historical collections accessible online through the use of metadata, and to the role it plays in digitization and digital tools. We provide an in-depth case study of the role metadata played in how we researched existing Litchfield Law School notebooks, created a new web portal to gather information about the notebooks, and digitized and made publicly available 142 notebooks. We will also discuss our future plans for using digital tools to enhance the description of and access to these resources. This work will make previously unrecognized and inaccessible Litchfield notebook resources available to researchers.

First, we will define metadata and describe how metadata makes historical collections discoverable. Second, we will discuss our creation of the Litchfield Law School Sources web portal, and how the web portal enhances researcher access to the Litchfield student notebooks. Third, we will discuss our digitization of the Litchfield notebooks and how we use digital images to provide access to these previously inaccessible notebooks. Finally, we will examine the research implications of our efforts for the future study of the Litchfield notebooks and online legal history generally.

I. Metadata

Sufficient metadata is needed to ensure accessibility to historical and digitized collections. Catalogers must accurately describe the title of the work, the extent of the work, and the people or entities involved in the creation and dissemination of the materials. For digitized collections, it is especially important to include information about where, when, and how digital materials were created to ensure access should the digital file and its metadata become separated. It is also important to include as much metadata as possible, as long as it is affordable to do so. Such information may be useful in the future. For example, metadata describing the particular technology used during scanning allows for easier accommodation to newer systems as they develop.Footnote 1 First, we must understand the different types of metadata and how they are used to make historical collections available online.

Metadata creation and curation, historically known as cataloging, is a library service that provides researchers with tools to discover and access all kinds of materials by describing resources in logical and consistent ways. By following local and international standards, catalogers create and maintain databases of metadata that are often accessible to researchers around the world.Footnote 2 As more collections emerge in digital media, it is more important than ever before to apply standardized metadata as a way to ensure access to those collections and connect them to other sources.

Metadata is typically separated into three categories: descriptive, structural, or administrative.Footnote 3 Descriptive metadata is used for discovery by including access points to the title, author, and subject, for example. A traditional catalog card contained mostly descriptive metadata. Structural metadata describes the complexity of a digital object, such as whether a digital book has various chapters.Footnote 4 Unlike a physical book, which can be thumbed through to find the various chapters or index, a digital book requires the structural metadata to help the user navigate the resource, a sort of digital thumbing through the chapters.Footnote 5

Figure 1 shows the display of Volume 1 of William Stutson Andrews' student notebook displayed in Harvard's Digital Library.Footnote 6 Structural metadata allows users to navigate the contents of the notebook on the left side of the screen.

Figure 1. Volume 1 of William Stutson Andrews' student notebook displayed in Harvard's Digital Library.

Administrative metadata refers to the management of the resource, such as the file type, when it was created, who can access it, and other technical information.Footnote 7

Preservation metadata is also important to include in digital metadata projects. Some definitions place preservation metadata under the umbrella of administrative metadata,Footnote 8 whereas others describe it as spanning all three categories. “[T]he scope of preservation metadata is best understood not so much on the basis of the detailed function of the metadata—i.e., to describe, to structure, to administer—but instead on the process, or larger purpose that the metadata is intended to support. And this is where a definition of preservation metadata begins: it is metadata that supports the process of long-term digital preservation.”Footnote 9

Many libraries and institutions have added descriptive metadata about their Litchfield notebooks through their library catalogs and through archival finding aids. Library online public access catalogs (OPACs) and finding aids are essential digital tools for searching metadata to discover historical collections.

The fundamental problem with manuscripts, such as the Litchfield notes, is that unique qualities of any manuscript elude uniform description, meaning that catalog records of these notes in thirty-six different libraries show great variation in documentation. In planning for the web site, one challenge has been to determine descriptive metadata that can be applied across the range of notebooks in a standard way to ensure consistent access by any researcher.

For example, the Yale Law Library has cataloged every Litchfield notebook held in the MORRIS online library catalog. Each Litchfield Law School student is entered as an author, and each notebook or set of notebooks has a title. Any notebook lacking a title was supplied one by a cataloger, clearly identifying it as a Litchfield Law School student notebook. The physical description of the notebooks is given, including number of volumes and height in centimeters. Where available, page counts have been added. The catalog entries usually have the same standardized subject applied to them, such as Litchfield Law School—Students, and the genre of the notebooks, Lecture Notes—Connecticut—Litchfield. Each catalog entry also describes any additional important notes about the notebooks. The notes for Frederick Chittenden's notebooks, for example, describe title pages that are elaborately decorated in pen and ink.Footnote 10 The catalog entries also add call numbers, shelf marks, or some other identifying location so that the physical material can be located within the library or institution.

Figure 2 shows the Yale Law Library catalog record for Frederick Chittenden's notebook. Standard metadata such as author, physical description, and subject appear on the record.Footnote 11 The subjects and genre/form metadata are represented as clickable links so that researchers can easily link to similar resources.

Figure 2. Yale Law Library catalog record for Frederick Chittenden's notebook.

These metadata ideally would be standardized across all libraries that have cataloged their Litchfield notebooks. WorldCat, a network of libraries sharing content and services,Footnote 12 allows researchers to search its collection of metadata from libraries around the world. Unfortunately, some libraries have not made their metadata about Litchfield notebooks available to WorldCat, and not all libraries, museums, and archival institutions are members. Consequently, there may be Litchfield notebooks and other collections that are unavailable to researchers.

An advance in metadata description for archival material has helped make Litchfield notebooks more accessible. At the Yale Law Library, each notebook is cataloged as an individual item within the library catalog. By contrast, at institutions where notebooks are considered to be part of an archival collection, notebooks may not be cataloged at all.

The encoded archival description (EAD) metadata standard allows archivists to describe the content and arrangement of archives in a standardized way, making those collections and individual items within those collections more discoverable. For notebooks that are not cataloged as items within a library but rather considered part of an archival collection, they can be described in a finding aid using EAD. Databases such as ArchiveGrid make these EAD finding aids searchable across multiple institutions.

Because some libraries have used EAD to make their archival collections searchable, our research has uncovered previously unknown notebooks. For example, the Rhode Island Archival and Manuscript Collection Online (RIAMCO) includes online finding aids in EAD. One of the archives described and searchable is the Theodore Francis Green Papers. According to the finding aid for this archive, Box 72 houses a set of Litchfield student notebooks.

Figure 3 shows the description of Box 72 from the EAD finding aid from the Theodore Francis Green Papers.Footnote 13 The description notes the author of the notebooks, and how many volumes are in the collection. However, unlike a catalog record, descriptions of the dimensions, page count, and other descriptions of the volumes are absent.

Figure 3. Description of Box 72 from the encoded archival description (EAD) finding aid from the Theodore Francis Green Papers.

These notebooks constitute a large collection of previously unknown materials. Although the Theodore Francis Green papers are located in the John Hay Library at Brown University, that library has made the metadata searchable in other databases outside their library catalog, thus enabling us to locate the Burgess notebooks. Because the Litchfield notebooks for our project are cataloged individually, we do not have or need an EAD finding aid for them; however, it is important that institutions with notebooks in archival collections use EAD finding aids to make the contents of those collections discoverable, particularly in the cross-institutional metadata repositories described later in this article.

Generally, catalog records are used as a way for researchers to find published material, whereas finding aids are used to describe archival collections of manuscripts, papers, and other unpublished material. Because the Yale University Library's Manuscripts and Archives division maintains Yale Law School's archives, the Yale Law Library does not have an in-house archivist. The manuscripts and other unpublished materials that the Yale Law Library maintains are processed by catalogers using the similar metadata standards as published materials. Both the Yale University Library and the Yale Law Library often use both catalog records and finding aids together for large collections. These two methods of describing collections are not mutually exclusive. Instead, catalog records describing archival collections and “finding aids are intended to work together as parts of a hierarchical archival access and navigation model.”Footnote 14 Therefore, the law library catalog may contain records describing an archival collection and links to finding aids describing the individual contents of the larger collection.

For our digitization of Litchfield notebooks, we created derivative catalog records for the digital objects. For cataloging purposes, the notebooks fell into two categories: those owned by the Litchfield Historical Society and those owned by the Yale Law Library. The Yale Law Library notebooks already had separate records, which were cataloged over several decades by different librarians and using different standards in place at the time. We did minimal updating before copying the records and adding digital metadata fields to create separate cataloging records for the digital versions. For example, the records for the digitized notebooks indicate that the latter are available online.

The notebooks from the Litchfield Historical Society required more extensive record creation because they did not have catalog records for each notebook. Instead, the Litchfield Historical Society provided us with two finding aids upon which to derive metadata for new catalog records. The catalog librarian at the Yale Law Library created new digital records for each Litchfield Historical Society notebook author.

We made the decision to add subject headings Litchfield Law School—Students and Law Students—Connecticut—Litchfield at the request of the rare book librarian at the Yale Law Library, who thought that those would be best for researchers. In general, subject headings should describe the content of the material, rather than the authors or the location in which the material was created. In this case, that would mean subject headings such as Criminal Law—United States, or whatever specific topics were covered in the individual notebooks. We felt that researchers interested in notebooks such as these would be more interested in the context than the content of the materials. Wherever possible, however, we added content notes that provide keyword access to those subjects.

In addition to the subject headings, we also added the genre/form term Lecture Notes to provide controlled vocabulary access to the type of material described. Genre/form terms describe what a work is, rather than what the work is about. In this case, the notebooks were original or transcribed notes of lectures taken down by students during their lecture-style law classes at the Litchfield Law School. The materials do not describe what lecture notes are, but rather that they are lecture notes in their form. This type of access point allows scholars to find and compare different kinds of lecture notes, perhaps narrowing to certain geographic areas or time periods as well.

Although advances in metadata standards and technology have greatly enhanced our knowledge of archival collections such as the Litchfield notebooks, we still have the same inaccuracies in descriptions, and, therefore, our access to the notebooks is also limited.

Previous bibliographies have also not always accounted for notebooks for which the student was unknown. In 1946, Samuel Fisher, Yale Law School graduate and one-time president of the Litchfield Historical Society, published Litchfield Law School 1774–1833: Biographical Catalogue of Students. The Catalogue includes names and whatever biographical information was available, and briefly described any notebooks authored by those students that were known to exist, and where they were held. Because this was a catalog of students rather than a bibliography of notebooks, there is not much detail given for the notebooks listed here. The information listed usually only consisted of the number of volumes and the institution or person in possession of the notebooks. No notebooks with unknown authorship are listed; therefore, this cannot be considered a comprehensive list of extant Litchfield notebooks.

The most descriptive and comprehensive bibliography of Litchfield Law School student notebooks was written by Karen Beck, Director of Historical and Special Collections in the Harvard Law Library.Footnote 15 In the article, Beck discussed the research value of law student notebooks and included a bibliography of student notebooks from many early law schools, including the Litchfield Law School. This extensive, fully indexed article and bibliography included detailed bibliographic descriptions such as the extent of archival papers, the size of notebooks, and the cataloger's descriptions of the notebooks themselves. Beck's bibliography also identifies notebooks with unknown authors, dates, and provenance.

This review of Litchfield student notebook metadata provides an important background for the context in which our project was completed. Differing metadata standards, levels of description, and historical practices necessitated the need to better describe the extant notebooks. Using the different types of metadata outlined here has helped us discover new notebooks and make existing notebooks more accessible to researchers.

II. Litchfield Law School Sources Web Portal

Because information about the Litchfield student notebooks varies so widely, the first step in our project was to create a portal to collect information about the Litchfield student notebooks. The Litchfield Law School Sources portalFootnote 16 was developed in 2012 as part of a plan to enhance access to the Litchfield notebooks. The project was initiated by Yale Law School professor John Langbein, and funded by The William Nelson Cromwell Foundation. The web portal is part of the Yale Law Library's Documents Collection Center. The Documents Collection Center was developed to provide access to primary source documents, synthesized research, and data created in support of Yale Law School student and faculty research. The Litchfield Law School Sources web portal naturally fit into the Documents Collections Center's mission and helped make these resources more widely accessible.

The Litchfield Law School Sources portal serves the dual purpose of assisting Whitney Bagnall, former Special Collections Librarian at Columbia Law School, in collecting and organizing her research as well as disseminating that research online. Over the past several years, Bagnall has been travelling to many law libraries recording important metadata about the Litchfield Law School student notebooks. She has been verifying the accuracy of metadata, recording additional information about provenance of the notebooks, recording metadata about the contents of each notebook by applying subject terms to notebook sections, and transcribing opening lines of lectures.

One important feature of the web site is its database describing the contents of each notebook by distinguishing different legal titles such as Baron and Feme, Real Property, and Powers of Chancery. The database lists each student whose notebooks have been located and examined for this project. We also have future plans for creating a definitive bibliography of extant notebooks, which we will discuss later in the article. The database records contents of notebooks, pages in which those contents are discussed, and opening lines of lectures and subheads.

Figure 4 shows a list of contents from Asa Bacon's notebook from the Litchfield Law School Sources web site.Footnote 17 Although this is not in a standardized form, this is metadata that we hope to apply to digitized notebooks in the future.

Figure 4. List of contents from Asa Bacon's notebook from the Litchfield Law School Sources web site.

Researchers can see a list of all the notebooks consulted for this project, a survey of notebook contents for each student with clickable subject terms, and additional links and information for each student and notebook.

Figure 5 shows some of the linked sources available from the Litchfield Law School Sources web site.Footnote 18

Figure 5. Linked sources available from the Litchfield Law School Sources web site.

Researchers can also browse through data about students who attended lectures on specific subject matters by date. Clicking on the term “Municipal Law,” for example, allows a researcher to see all of the lecture notes on that topic, as well as opening lines from notebook sections. For example, researchers will see that Tapping Reeve delivered a lecture on municipal law on November 4, 1794, and three student notebooks include notes from this date. Researchers can compare each student's notes from the lecture, as well as seeing how the subject of municipal law changed over time.Footnote 19

Figure 6 shows the names of three students who attended the same lecture on the topic of municipal law on November 4, 1794 at the Litchfield Law School, and the differences in the opening lines transcribed from each notebook.Footnote 20

Figure 6. Names of three students who attended the same lecture on the topic of municipal law on November 4, 1794 at the Litchfield Law School, and the differences in the opening lines transcribed from each notebook.

Although some legal titles forming the curriculum remained constant—contracts, for example, was a fixture—the curriculum expanded over the years with additional titles. Lectures on private wrongs, for example, are first recorded in 1798 in notebooks of Daniel Sheldon, Jr.

The web site now includes additional features to aid researchers interested in the history of legal education at Litchfield. There are outlines of curricula from different periods, when Reeve alone was teaching (before 1798)Footnote 21 and when both Reeve and Gould were lecturing (1799–1820).Footnote 22 Another curriculum will be added to include Gould's order of lectures, based on his presentation of 48 legal titles (1820–33). On the strength of lectures with dates, it was possible to construct a chronology to show that certain students were attending and recording lectures at the same time. These overlapping lectures would benefit from close comparison, something difficult to do when the volumes are in separate collections. With digital images as part of the web site, including a list of all known digitized notebooks regardless of institution,Footnote 23 this obstacle can be eliminated.

Collecting all the information about the Litchfield student notebooks in one place has already enhanced our understanding of these materials. For the first time, researchers can compare information about notebooks among institutions using a single interface. Further work is needed to standardize these metadata. However, the web portal represents an important first step in pulling together information about the disparate collections of notebooks. “By comparing Litchfield notebooks across the decades, it should be possible to form a fairly detailed view of the Americanization of the common law.”Footnote 24

III. Digitizing All Notebooks at Yale Law Library and Litchfield Historical Society

After creating a web portal for collecting information about the Litchfield notebooks, digitizing our collection was the next logical step. As part of the Litchfield Law School Sources web portal project, the William Nelson Cromwell Foundation provided a grant to digitize the collection of notebooks held by the Yale Law Library and the Litchfield Historical Society. In total, the Yale Law Library digitized 142 notebooks composed of more than 60,000 individual page images. However, the true cost of digitization extends beyond this initial investment. The act of digitization raises important, ongoing questions about how we create, preserve and provide access to digital images.

Digital preservation specialists have long ago recognized that access to knowledge in the digital realm requires the preservation of access. Paul Conway, former Head of Preservation at Yale University Library, discerns the distinction between preservation and access: “In the digital world, preservation is the action and access is the thing—the act of preserving access.”Footnote 25 It follows that “In the digital world, preservation is the creation of digital products worth maintaining over time.”Footnote 26 Articulating these distinctions provides context for digitization of the Litchfield Law School student notebooks.

Beyond recognizing the historical value of these notebooks, there are three distinct but interrelated considerations that drive a digital conversion program: 1) purposes that the digital products will serve, 2) source document characteristics, and 3) technological capabilities brought to bear during the conversion process.Footnote 27 Conway observes that reformatting serves the purposes of “protecting the originals,” “representing the originals,” and “transcending the originals.” Digitizing the Litchfield notebooks can help limit handling of the original source material while simultaneously expanding access to its content. Accurate representation of the original provides an acceptable surrogate for research and discovery. The notion of transcending the originals provides possibilities for new and unforeseen usage, anticipations that are beyond the scope of this initial project but that can be addressed in future plans. The latter two considerations for digital conversion, source document characteristics and technology, drive decisions for scanning specifications, the selection of access methods, and ongoing maintenance.

The goals we set for longevity in the digital world are predicated upon the recognition that digital longevity “is not a physical attribute of digital reproductions, but an assigned lifespan that is backed up by the recognition that today's decisions regarding digital quality and functionality will need to be supported [in the long-term].”Footnote 28 Therefore, to ensure the preservation of access, we had to articulate these principles at the outset: to create digitized images that can and should be preserved, with the understanding that maintaining digital objects over time requires ongoing institutional commitment. Therefore, the provision of sustainable access required initial decisions for digitization that included technical specifications for image capture and retention, ensuring integrity of the digital objects, specifications for image quality control, and a sustainability plan to transition the digital objects and metadata into the Yale University Library preservation program.

We have taken multiple approaches to providing access to the digitized notebooks, ensuring that they are freely available, open, and discoverable in as many different places as possible. To begin with, we uploaded the original, high-resolution digital images of each notebook (more than 60,000 images in total) to the Internet Archive. The Internet Archive bills itself as an “Internet library,” with the purpose of “offering permanent access for researchers, historians, scholars, people with disabilities, and the general public to historical collections that exist in digital format.”Footnote 29 The list of digitized notebooks on the Litchfield Law Sources web site links to the Internet Archive version of the notebooks digitized for this project.Footnote 30

The Internet Archive offers several advantages as an option for providing access to our digitized notebooks. First, it is free for libraries and institutions and users alike. The Internet Archive also allows users to access the notebooks in multiple formats. For example, it automatically converts the high-resolution images into low-resolution PDFs that can easily be downloaded in a reasonable amount of time by most Internet connections. In some instances, the PDF document will be good enough for researchers; however, when the physical notebooks were in poor condition, the PDF document may not be clear enough for transcription or in-depth research. In those cases, researchers can view high-resolution images online, or even download the high-resolution images to their own computers.

Figure 7 shows Volume 1 of Aaron Burr Reeve's notebooks on the Internet Archive.Footnote 31 The notebook can be viewed online using page-turning software; metadata appears below the digitized notebook. On the Internet Archive, each notebook has its own web page with options for viewing or downloading that notebook.

Figure 7. Volume 1 of Aaron Burr Reeve's notebooks on the Internet Archive.

The Internet Archive's page-turning software allows users to view the digitized pages of the notebooks in this high-resolution format. The page turner can also be embedded in other web pages, so that we could easily add an actual page-turner view of these digitized pages to our Litchfield Law School portal or other web sites as desired.

We have also uploaded a PDF version of the notebooks to the Yale Law Library's eYLS Scholarship Repository. The Scholarship Repository is an online repository of Yale Law School scholarship by students and faculty, as well as some scanned historical documents.Footnote 32 The Litchfield notebooks are part of the historical collection. Although this would seem duplicative, uploading the notebooks to the Scholarship Repository and elsewhere helps make the notebooks even more widely available to scholars all over the world, and creates redundancies in case web sites or digital copies are lost, corrupted, or otherwise unavailable.Footnote 33

Figure 8 shows William Whiting Boardman's notebooks in the Yale Law Library Scholarship Repository.Footnote 34 Although there is no page-turning software, PDFs of all the notebooks are collected together under the same student's name and are available for download from a single web page.

Figure 8. William Whiting Boardman's notebooks in the Yale Law Library Scholarship Repository.

The process of digitizing the Litchfield notebooks raised many issues about how we preserve and provide access to digitized historical collections. These decisions have direct bearing on the ease with which researchers can both locate and interact with the notebooks now and in the future.

IV. Future Developments and Research Implications

Our review of and research into existing metadata, digitization, and our own efforts have made clear that there are significant questions, gaps, errors, and inconsistencies in our knowledge of extant Litchfield Law School student notebooks. We have three primary goals for moving forward with this project: to use our existing web site and research to create a comprehensive and definitive bibliography of extant notebooks, to leverage our metadata work to share access to and enhance study of the Litchfield notebooks through a variety of research platforms, and to use the Litchfield Law School Sources project as a model for making the Yale Law Library's historical treasures more widely available to researchers around the world.

We have already begun research into creating a new comprehensive bibliography of the Litchfield notebooks. We have discovered a number of new notebooks, such as the notebooks of Welcome Arnold Burges at Brown University. We have also raised questions about our knowledge of previously described notebooks that must be answered by researchers to improve our understanding of early American legal education and history.

However, our bibliography will also be different from previous efforts. The bibliography will list and number notebooks individually. Whereas previous bibliographies numbered students or student authors or provided an unnumbered list of students, our bibliography will have a separate entry for each notebook. This has the benefit of allowing researchers and libraries to keep better track of notebooks that change location or have had vague or confusing provenance, as well as allowing us to easily add or incorporate newly discovered notebooks, assigning each new notebook a number in the bibliography. We will be able to provide improved direct access to notebooks that have been digitized and any notebooks that may be digitized in the future. Each individual notebook that has been digitized can include a link to its corresponding digital reproduction.

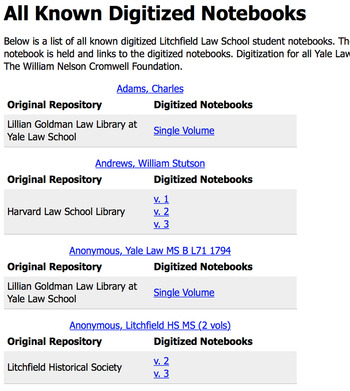

Figure 9 shows our current list of known digitized notebooks.Footnote 35 Each entry lists the original repository where the physical notebook is held and a link to its digital surrogate. A future bibliography, building on this concept, would list and number each notebook, and include links to catalog records, finding aids, or other appropriate metadata entry where digital surrogates were unavailable.

Figure 9. Our current list of known digitized notebooks.

We are also investigating the use of stable URLs to ensure that researchers never receive an error when searching for a notebook. Persistent uniform resource locators (PURLs),Footnote 36 digital object identifiers (DOIs),Footnote 37 and handlesFootnote 38 are the most likely solutions we will pursue for creating stable unique URLs for each notebook. Using these stable URLs might help us keep track of any digitized notebooks whose location changes. Then, if the links at the Internet Archive or Yale repositories change we can simply change the location to which the stable URL points. In other words, the stable URLs will always work and direct the researcher to the correct location if the final destination of the digitized notebook changes. Such permanence for the digitized Litchfield notebooks would be very important to researchers for use of the material and citation. This will also be important if new notebooks are digitized. Stable URLs for nondigitized notebooks could point to catalog records or finding aids before a notebook is digitized, but point to the digitized notebook afterwards.

Additionally, libraries can incorporate these assigned bibliography numbers and permanent URLs into their own catalog or metadata. As a result, a researcher looking for Litchfield notebooks in the Harvard library catalog or the George Washington University Law Library catalog would not only find those library's locally held notebooks but might also find links to other notebooks that have been digitized. Researchers would also be able to identify those locally held notebooks within the larger context of the comprehensive Litchfield notebook bibliography.

Next, we will try to leverage our technology and metadata work to enhance access to and study of the notebooks. The most important metadata work is to ensure that it is standardized and, therefore, can be easily shared across multiple discovery systems. For example, the Internet Archive allows us to export metadata from our catalog to the Internet Archive in a standardized XML-based format known as MARCXML.Footnote 39 Many other libraries are also sharing their digitized objects and standardized MARCXML metadata records with the Internet Archive to make them more accessible. Searching the Internet Archive for the Litchfield Law School brings up the notebooks from the Yale Law Library and the Litchfield Historical Society, and also brings up additional digital objects related to the Litchfield Law School available to researchers in the Internet Archive.Footnote 40

Having standardized metadata in the Internet Archive has the added benefit of allowing that metadata to be shared with other research platforms. For example, the Internet Archive is a content hub for the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA).Footnote 41 The DPLA is a portal that ingests metadata from hubs all over the United States to make them discoverable in one location.Footnote 42 Content hubs are usually large institutions such as libraries, museums, or collections, such as the Internet Archive, that share their metadata with the DPLA. Once shared with the DPLA, the items become discoverable, and anyone searching the DPLA for Litchfield Law School on the DPLA portal would be able to find the notebooks. The DPLA would then link users from the metadata to the storage location at the Internet Archive.

Figure 10 shows search results for the Litchfield Law School in the DPLA.Footnote 43 Contributing institutions and partners are listed on the left side of the screen. The harvested metadata are displayed in the search results with links to where the digitized “object” is available.

Figure 10. Search results for the Litchfield Law School in the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA).

There are additional DPLA hubs that we may also partner with that would not only ensure that the Litchfield notebooks are discoverable in the DPLA, but would also make them easily discoverable by researchers in many different locations. For example, the HathiTrust is a partnership among various research institutions to preserve the cultural record. Their digital library includes digitized material from many different libraries, and they also serve as a content hub for the DPLA. Yale University is a partner in the HathiTrust, and we are currently working with the Yale University Library to ensure that the Litchfield Notebooks are available in the HathiTrust.

The Connecticut Digital Archive (CTDA)Footnote 44 is also a service hub for the DPLA. Sharing our metadata with the CTDA would also have the added benefit of partnering with local, Connecticut institutions on a project of important local history.

Sharing our metadata and making the Litchfield notebooks as well as any future digital objects available through multiple digital platforms and the DPLA would be beneficial for researchers. Historians can use the DPLA to search across the digitized collections of multiple institutions all at the same time, using a standardized set of metadata. It would not matter where the collection was digitized: historians could simply find all digital objects by date, subject, or another metadata field, and the DPLA would direct them to the actual digital object. This will help ensure that the Litchfield notebooks are discoverable for researchers without their having to know the original repository.

The Internet Archive is also important because it makes digital images available through the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF).Footnote 45 A post from the Internet Archive Blogs on October 23, 2015 describes some of the ways that IIIF can improve the study of digitized images.Footnote 46 For example, through the Internet Archive IIIF, scholars can compare multiple books from the same time period side by side in great detail. The possibilities opened up by these types of software tools combined with the appropriate metadata could open up a world of possibilities for historical research.

Figure 11 shows two digitized Litchfield student notebooks side by side using Mirador,Footnote 47 an IIIF viewer. The notebook on the left is Volume 1 of Samuel Cheever's notebook, located at the Harvard Law Library and hosted by Harvard Digital Library.Footnote 48 The notebook on the right is Volume 1 of Nathaniel Mather's notebook, located at the Litchfield Historical Society and hosted by the Internet Archive.Footnote 49 As shown in Figure 12, we know from the Litchfield Law School Sources web site that both students attended lectures on Municipal Law at the same time.Footnote 50 Now, because of the IIIF, standard researchers can compare these notebooks side by side despite the fact that they are held by two different institutions and that the digital surrogates are hosted on two separate web sites.

Figure 11. Two digitized Litchfield student notebooks side by side using Mirador.

Figure 12. From the Litchfield Law School Sources web site, it can be seen that both students attended lectures on Municipal Law at the same time.

These tools also open up the possibility of other uses of technology, such as crowdsourcing transcription. Crowdsourcing involves the use of large groups of people, particularly online, to complete a task.Footnote 51 In this instance, online users could be asked to transcribe individual page images or pieces of a notebook. Researchers could then compare the language of lecture notes on a particular subject from the same years, but from different student authors, or compare one subject across many years to see how the lectures evolved over time.

These tools have important implications for the study of the Litchfield notebooks and other historical collections. The ability to share metadata across multiple digital libraries and even to directly compare and contrast digital images from different repositories represents a major leap forward for historical research.

V. Conclusion

This case study describes the process by which the Yale Law Library used metadata to create a web portal and digitize and provide access to the disparate collections of Litchfield student notebooks. The lessons learned have already informed the Yale Law Library's plans for future projects. We have emphasized the importance of using standardized metadata to describe historical collections before, during, and after the digitization process to ensure proper preservation and access of digitized items.

Incorporating standardized metadata and workflows into the law library's digital infrastructure is the key to making our collections available to researchers around the world. Using the techniques described in this article, the law library hopes to help contribute to digital tools used for historical research.

Finally, we see the Litchfield Law School Sources project as a model for future digital projects involving historical legal collections. The combination of primary source research, web site tools and database, digitization, and standardized metadata have the potential to unlock previously unknown, unusable, or inaccessible resources for study. We hope that the Litchfield Law School Sources web site and associated web sites, databases, and resources and future projects can have a wide-ranging impact on legal history research in the years to come.