I. INTRODUCTION

From 1759 to 1762, François Quesnay regularly appealed to Charles Richard de Butré (1725–1805) when he had to make numerical estimates or perform non-elementary computations (Charles and Théré Reference Charles and Théré2008). Although hardly mentioned in the secondary literature, Butré was indeed an important collaborator of Quesnay’s. The present article gives a detailed account of Butré’s contribution to Physiocracy by concentrating on the period from 1766 to 1768, when Quesnay conceived and published his last versions of the Tableau économique.

The oblivion into which Butré has fallen may be attributed to the fact that several of his most interesting writings have never been published. This is the case for two texts written at the end of 1766 and the beginning of 1767, which constitute the foundation of our argument for reassessing Butré’s contribution to Physiocracy. The first of these two works is a short text that Butré submitted to the famous prize competition on the subject of indirect taxes, which Anne Robert Jacques Turgot held in Limoges in 1766. The original copy has been lost, but we have been able to find a nearly complete draft version in Butré’s own hand. The draft sheds light on the development of his economic thinking in relation to that of François Quesnay. The second work that we will discuss is a short but very ambitious treatise—Elémens d’oeconomie politique (Elements of political economy)—which he wrote in order to detail the theoretical model on which his contribution to the Limoges prize was conceived.

In these two works, Butré set himself to the task of expanding on Quesnay’s political economy. Although he was the only Physiocrat aside from Quesnay who mastered the Tableau économique, he chose to develop his own analytical devices. In order to provide a more satisfactory presentation of the doctrine of the exclusive productivity of agriculture, Butré significantly modified the social classification adopted by Quesnay and all the other Physiocrats. In the end, he conceived of and drafted a theoretical system for public accounting that would measure and account for all kinds of economic activities, including those Quesnay had left out in his Tableau économique, such as external trade. As Butré worked on these texts when Quesnay was developing and applying the mature version of the Tableau known as the “Arithmetical formula,” we argue that the study of his work offers us a fascinating vantage point for broadening our understanding of the nature and the history of Physiocratic political economy. Although the historiography of Physiocracy tends to belittle Quesnay’s disciples by denying that there was hardly anything genuine in their texts, we claim that this was not true for Butré and that these two texts developed Quesnay’s economic theory in a creative way. These two texts are important also because they constitute one of the earliest cases of systematically applying algebra to economics: this specific aspect of Butré’s rich contribution to the history of political economy is detailed in a companion article that will be published in a forthcoming issue of this journal (Charles and Théré Reference Charles and Théré2016).

In the second section, we provide a short intellectual biography of Charles Richard de Butré. In the third section we detail the context in which Butré developed his main contribution to Physiocratic analysis in the 1760s. In the fourth section, we focus on the analysis of Elements of Political Economy and his contribution to Physiocratic social analysis. In the fifth section, we present a rational reconstruction of Butré’s economic theory in order to provide a systematic comparison of the economic analysis of Quesnay’s Tableau économique and Butré’s Elements, which is the subject of the sixth and last section of our article.

II. BUTRÉ: A SHORT INTELLECTUAL BIOGRAPHY

The nineteenth-century archivist and local historian Rodolphe Reuss wrote a full-length biography on Butré. He based his book almost exclusively on a set of papers he discovered, now deposited in the Médiathèque André Malraux of Strasbourg. Footnote 1 Although many of Butré’s papers have been lost, our research uncovered three other sets of papers in addition to the Strasbourg’s collection. First, there are several documents among Victor Riqueti Mirabeau’s papers at the French National Archives that were written partially or entirely by Butré. Footnote 2 A second collection is among the Margrave of Baden’s family papers in the state archives of Baden-Württemberg (Generallandesarchiv, Karlsruhe). Footnote 3 A third set of papers is composed of a single box from the Archives Départementales (AD in the following) of Indre-et-Loire. Footnote 4 The box includes documents written by Butré during the 1760s and 1770s. Among this last set of papers, there are several new and important pieces. Footnote 5 These sources allow us to outline in some detail the life and intellectual activities of Charles Richard de Butré before the French Revolution.

Charles Richard was born March 22, 1725, in Pressac, a village situated at the crossroads of Limousin and Poitou. Footnote 6 He was the first child of François Richard, lord and owner of the estates of La Jarige and La Tour, and of Lady Elisabeth Garnier de Butré. The godfather of the newborn was Charles Garnier, Lord of Butré, a title the child would carry throughout his long life. Footnote 7 Richard de Butré was sent to a college at the age of seven. Footnote 8 Being the first son of a local noble and well-off family, he probably went to the Royal College of Saint-Marthe in Poitiers, which was managed by the Jesuit order. In effect, it was an educational institution privileged by the Poitou gentry (Favreau Reference Favreau1988, p. 178). Footnote 9 Saint-Marthe was a wealthy college with a nice library. It maintained a chair in mathematics from 1690 onward (Dainville Reference Dainville1954a, pp. 10–11, and Reference Dainville1954b, p. 113; Delattre Reference Delattre1956, pp. 27–28; Delfour Reference Delfour1901, p. 269). At the time that Butré attended the college, the chair was occupied by Father François Lanauve (1686–1744) from 1732 to his death in 1744 (Dainville Reference Dainville1954b, p. 113; Fischer Reference Fischer1983, p. 63). Footnote 10 The students were introduced to mathematics during the final two-year phase called philosophie (Brockliss Reference Brockliss1987, p. 386). The founding of mathematical chairs in Jesuit colleges provided an initiation to pure mathematics as well as to “one of the most powerful agents of legitimation of applied mathematics” (Harris Reference Harris and Giard1995, p. 243). The usual mathematical program in French Jesuit colleges comprised, among other things: “arithmetic, algebra, geometry and elementary trigonometry” (Dainville Reference Dainville and Taton1964, p. 52; see also Harris Reference Harris and Giard1995, p. 242).

After completing his degree, Butré left his family for Versailles and the king’s army. On December 26, 1743, aged eighteen, he enrolled in the third company of the king’s bodyguards, commanded by the Duc d’Harcourt, a prominent courtier. Footnote 11 From this moment on, he was at the court (each of the four bodyguard companies performed a trimester of duty in Versailles), in Paris, or in the western part of Ile de France where his company was assigned to any of the following cities: Poissy, Vernon, Mantes, or Pontoise. When the Duc d’Harcourt died in 1750, his company went to the Marshall of Luxembourg, a relative of the Duc de Villeroy, who was one of François Quesnay’s main patrons (Charles and Théré Reference Charles, Théré, Forget and Weintraub2007). Throughout this period, Butré returned sporadically to Pressac, usually for some family event such as a birth, marriage, or a death.

Sometime in the 1750s, Butré met Madame de Pompadour’s physician, Quesnay, who liked to surround himself with agronomists. Footnote 12 In 1756, Butré’s father died, leaving him a significant estate in Poitou and Limousin. Butré inherited several land estates that he sold over the next few years. He seemed to have had little care for material wealth and distributed most of the product of these sales to his siblings, keeping for himself only a relatively modest sum. Having settled the inheritance of his father, Butré terminated his military career and left Versailles for a medium-sized estate (ten arpents) that he bought for 9,500 livres near Tours. Footnote 13 Meanwhile, he began to work with François Quesnay and, to a lesser extent, the Marquis de Mirabeau by contributing anonymously to several of their published works (Charles and Théré Reference Charles and Théré2008, pp. 10–11, 18–22, and 27–28). Butré also developed a significant interest in husbandry and became one of the founding members of the Royal Agricultural Society of Paris. Footnote 14

After his departure from Versailles, Butré divided his time between attending to his estate near Tours and traveling across France and abroad to collect agricultural accounts as well as data on cultivation and its returns throughout Europe. Footnote 15 The lack of sources impedes drawing up a precise listing of his travels during the 1760s and early 1770s. However, we can provide a general pattern and even specific information on a few episodes. From 1762 to the beginning of 1767, Butré traveled throughout the central and western part of France. In his 1767 introduction to the series of four articles he published in the Physiocratic journal, the Éphémérides du citoyen, Butré stated that he “went all over a large part of the provinces of Touraine, Poitou, of Limo[u]sin, of the Marche, of Berry, of the Xaintonge [sic], of the Angoumois,” and that he had surveyed “several estates” during his travels (Butré Reference Butré1767b, VIII, p. 8). Footnote 16 Furthermore, Butré was also invested in other intellectual projects in 1766 and 1767. In particular, he submitted an essay to a competition on the effects of indirect tax, which was held by the Limoges Royal Agricultural Society. In parallel, Butré wrote Elémens d’œconomie politique, a small treatise in which he synthesized his Physiocratic researches (see below, and Charles and Théré Reference Charles and Théré2016).

In the second half of 1767, Butré discontinued his theoretical research in order to undertake a journey in Russia on behalf of Pierre-Paul Le Mercier de la Rivière. The Russian empress Catherine II recruited Le Mercier as an economic and legal expert, and he departed from France with several aides and secretaries in the second half of July 1767. Footnote 17 The Physiocrats believed—wrongly, as history has shown—that Catherine had the intention of introducing Physiocracy in Russia, and they commissioned a few groups of sympathizers to spread the “new science.” Butré was one of the men Le Mercier took with him, probably with the idea of using the former’s mathematical and accounting skills. They both came back in May 1768. A few weeks after his return, Butré exposed “the sorrow state of agriculture in Russia and the northern states where laborers are overburdened by indirect taxes” in a session of the Agricultural Society of Orléans (Fauchon Reference Fauchon1927, p. 47). However, Butré did not resume the research program he initiated in 1766 and early 1767. All his subsequent writings on political economy would be more traditional, combining husbandry and Physiocracy with some arithmetical computations in the same manner as the articles he published in the Éphémérides.

Exactly what Butré did in the following years is more difficult to describe with precision. He seems to have followed Voltaire’s dictum “to cultivate one’s garden” on his estate. Footnote 18 He published nothing, and all we know is that he wrote to the contrôleur général, Terray, at the end of 1769 and again in early 1770. He also spent some time in his native Poitou, visiting his family in 1770 and 1773. He also kept in contact with Quesnay, with whom he exchanged a few letters on metaphysics in early 1772. Footnote 19 Butré resurfaced in the second half of 1774 and early 1775 when he journeyed to Baden for the first time, probably hoping to get an appointment in the service of the Margraven, who wanted to implement Physiocratic tax reform in his territory. The Physiocrat returned to France in the late spring of 1775. After his return, Butré hastily composed a booklet on taxes, which contained a long eulogy of the Margrave of Baden; it was part of Butré’s campaign to get a permanent position from the latter. Footnote 20 During the summer of 1775, he exchanged letters with the new contrôleur général and sympathizer of the Physiocrats, Turgot, promising to furnish him with memorandums on the method for evaluating the income of the French kingdom, but nothing came of that. In 1776, he again sent an essay, “Mémoire sur les revenus des biens fonds,” to another literary competition held by the Royal Agricultural Society of Limoges. In each case, his initiative failed to return anything tangible for Butré. Footnote 21

Fortune finally smiled on Butré when he obtained an important position in the economic administration of the Margrave of Baden, thanks to a warm recommendation by the Marquis de Mirabeau. Butré was to help the Margrave to implement his plan of tax reform. Footnote 22 He left France in 1776 to settle in Baden. Boosted by his more secure position, Butré worked quite actively during this period. He produced several books, including Loix naturelles de l’agriculture et de l’ordre social, his most significant work from this period, printed in Switzerland in 1781. Throughout all these years, Butré maintained correspondence with his patron, Mirabeau, and traveled extensively in Switzerland, France, the German states, and even Spain, amassing more materials that mainly concerned agricultural accounts. Some of these were collected in a German publication, Handbuch für Ackersleute und Beherrscher, literally Manual for Peasants and Rulers. Footnote 23 Sometime during the 1770s, Butré became fond of mysticism and mesmerism and published a booklet on the subject in 1777. Footnote 24 His private papers attested that his interest in these matters continued to the end of his life. Around 1789, Butré began to travel more often in France, producing a very short piece on French finances and, in 1794, a last publication on the cultivation of fruit trees, which summed up his Baden experiences on that subject. This last work was released by Du Pont’s printing press. It shows that—even with the geographical gap—Butré had maintained contact with some Physiocrats throughout this period. Footnote 25 At the end of the 1790s, Butré finally left Baden to establish himself as a gardener in Strasbourg, where he died at the age of eighty on January 18, 1805. Footnote 26

III. BUTRÉ AND PHYSIOCRACY: 1760–1767

From the end of the 1750s, Butré, a king’s bodyguard by trade, dedicated a significant part of his time to the study of political economy. Up to 1762, he participated in several texts Quesnay wrote with the Marquis de Mirabeau. Richard de Butré’s contribution concentrated on the accounting and computations contained in these works. Footnote 27 Accounts and calculations as well as short texts from Butré’s hand appeared in the drafts of Quesnay’s and Mirabeau’s works from the early 1760s: the Tableau oeconomique avec ses explications, Théorie de l’impôt, and Philosophie rurale. In the first, Butré did most of the computations necessary for drawing up several new Tableaux économiques (Quesnay Reference Quesnay, Théré, Charles and Perrot2005, I, p. XXIV). In the Théorie de l’impôt, Butré was one of the three calculateurs (computers) that Quesnay employed to provide data on the French agriculture and tax incomes and to verify the several computations he made (Quesnay Reference Quesnay, Théré, Charles and Perrot2005, I, p. 1185). In the making of Philosophie rurale, Quesnay relied heavily on Butré in the preparation and verification of the numerous computations that were contained in this work. Butré also provided the three agricultural accounts that were inserted in the final text (Mirabeau and Quesnay [1763] Reference Mirabeau, Quesnay, Dupuy and Masne2014, pp. 425–432, 452–454).

In parallel to his work as an aid to Quesnay and Mirabeau, Butré began to develop his own contributions to Physiocratic political economy. In 1761, he presented one memorandum to the Royal Agricultural Society of Paris. Footnote 28 In 1762 or 1763, Butré wrote the interesting Mémoire sur la liberté du commerce des grains for an agricultural society, probably that of Paris. Footnote 29 After he left Versailles, the Physiocrat stayed in touch with François Quesnay, who encouraged him to collect agricultural accountings. The latter believed that Butré would be able to provide a solid empirical basis for Physiocratic theory. A few years later, Mirabeau would describe Butré as one of the most valuable Physiocrats, a “direct pupil of the venerable doctor Quesnay, and this commendable old man saw him as unique in his kind and the most useful of all.” Furthermore, “The inventories of cultivation, published in the first volumes of the former Éphémérides, are from him.” Footnote 30 In another letter, Mirabeau emphasized that, besides Quesnay, Butré was the only Physiocrat who could claim to have mastered the Tableau économique. Footnote 31

Quesnay’s initial suggestion to systematically collect agricultural accounts was partially fulfilled in the mid-1760s as a consequence of the debate on the notions of grande and petite culture. The discussion took place in several economic periodicals, such as the Gazette du commerce (later Gazette de l’agriculture, du commerce et des finances), the Journal oeconomique, and the Journal de l’agriculture, du commerce et des finances. It was also echoed in sessions of the dozen agricultural societies that were founded from 1761 to 1763, and it was discussed in several agronomic and economic publications from this same period. Footnote 32 It is in this context that Butré published his first piece, a letter on the “grande et la petite culture,” in the September 1766 issue of the Journal de l’agriculture. In this short text, the Physiocrat explained the principles of agricultural accounting. He pointed out the necessity to establish rigorous microeconomic categories in the accounting of individual farms, in order to use them as material for economic discussions (Butré Reference Butré1766a). At the end of the letter, Editor-in-Chief Du Pont advertised that Butré was conducting a project for systematically collecting and compiling agricultural accounts, and he announced its imminent publication.

It took almost a year for Butré to publish the results of his research in the Éphémérides du citoyen. In a series of four articles, Butré elaborated a macroeconomic analysis of French agriculture based on a dozen detailed agricultural accounts. In the first two texts from the series, the Physiocrat offered a nuanced view of the distinction between grande and petite culture. Instead of sticking strictly to the binary opposition established by Quesnay and disseminated by Du Pont, Butré chose to break down each of these two categories into three sub-categories—or “types”—of agricultural production units. Footnote 33 In contradistinction to his predecessors, Butré detailed the technologies used by different kinds of cultivation—something that was commonly done in the husbandry manuals but not in the Physiocratic literature. Footnote 34 He related this discussion to the argument that a lack of capital invested in production was the main cause of low economic returns. For example, Butré argued that the plowing technology used in petite culture for sowing saved seeds and required lower investment, but at the expense of using much more labor as well as providing much lower returns. Hence, it was on the whole less productive; that is, its rate of return for capital invested was lower than that of the plowing technology used in the grande culture (Butré Reference Butré1767b, XI, pp. 71–81). In the third article from the series, the Physiocrat averaged the values of rent and taxes that he obtained from his several farm accounts in order to provide a general estimate of the proportional amounts of net product to taxes collected by the state. In it, he used his microeconomic measurements to provide macro estimates of agricultural income and taxes. Footnote 35

Butré stands out among Quesnay’s followers as the one who was willing and able to link together these two levels of analyzing (agricultural) production. He went beyond a purely empirical inquiry and analyzed the articulation between theory and measurement. In order to tighten up the link between the micro and macro levels, Butré developed new tools such as algebra to aid in developing and testing his arithmetical model of the economy. Footnote 36 The Physiocrat first used this new approach in an essay submitted to a literary competition on the consequences of indirect taxation. Footnote 37 The competition held by the Limoges Royal Agricultural Society on behalf of Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, then the provincial intendant, was advertised in January 1766 in several periodicals. Footnote 38 The essay by Butré arrived in December 1766, but it did not win the prize. It did not even obtain a mention by the jury. Footnote 39 In fact, Turgot did not like Butré’s text (Turgot Reference Turgot and Schelle1766, p. 520). The form of Butré’s dissertation was clearly at odds with the current rules of the genre of academic dissertation: Footnote 40 it was of short length and full of algebra with only minimal comments. It did not appeal to the members of the Limoges society, either.

Butré had modeled his submission to the Limoges contest upon the blueprint of the Problème économique, which Quesnay had published a few months earlier in the Journal d’agriculture, de commerce et des finances. Indeed, after a brief presentation of his economic principles and analytical apparatus, Butré rephrased the prize competition subject as a “problem.” There is a sequence that runs from the publication of Quesnay’s Problème économique in August 1766, to Butré’s dissertation presented to the Limoges society in December of that same year, to Quesnay’s second Problème économique—which was included in the collected volume Physiocratie and published at the end of 1767. In his first Problème économique, Quesnay adhered to a form of presentation that was completely new for works on political economy: a presentation he had borrowed from the contemporary mathematical manuals. Footnote 41 When compared with the plan of Quesnay’s text, the only significant variant introduced by Butré was to provide an outline of his theory before stating the problem with a question. Footnote 42 In his “Second Economic Problem,” Quesnay began with a set of preliminaries and tables, in the same manner as Butré did in his dissertation (Quesnay Reference Quesnay, Théré, Charles and Perrot2005, I, pp. 620–625). The parallel between the two texts goes even further since, in his second problem, Quesnay proposed his own answer to the issue set by the Limoges society; i.e., “the difference between the consequences of indirect and direct taxation.” Footnote 43 This evidence strongly suggests that Butré and Quesnay kept each other informed of their respective works and even worked in parallel on the same issues during this period. Footnote 44

Even if the two texts share the same formal structure, they develop alternate means to estimate losses due to indirect taxation. While Quesnay used his Tableau économique and arithmetical computations, Butré created something completely different. First, he developed his own kind of tables. Footnote 45 Since Butré did master the complexities of the Tableau, we must assume that he was not satisfied with Quesnay’s method of exposition. The choice he made might be explained by the fact that he later calculated several ratios using algebra. This task would have been much more complex and clumsy if he had used Quesnay’s Tableau, which is not as easy to translate into a set of linear equations (Charles Reference Charles, Durlauf and Blume2008).

IV. THE ELÉMENS D’OECONOMIE POLITIQUE AND PHYSIOCRATIC ANALYSIS

When preparing his Limoges essay, Butré felt the need to provide a theoretical blueprint of it. In the latter, he wrote at one point that “in my Elémens d’oeconomie politique, I will detail further the reciprocal effects of taxation on the productive and sterile parts [i.e., sectors] (Butré Reference Butré1766b, p. 11; italics in the original). In his papers there is a draft of a small treatise on political economy, which bears the name Elémens d’oeconomie politique. This fits this description exactly. In what remains of Butré’s papers in the Archives Départementales of Indre-et-Loire, the different parts of the draft of Elémens d’oeconomie politique are dispersed. We were able to reconstitute the entire document, which is made up of five sections. Four of them are subtitled “1er cayer,” “2e cayer,” “3e cayer,” and “4e cayer” (“first notebook,” etc.). The last document has no title and consists mostly of seventeen tables that abstract the calculations made in the notebooks and their results. This was the continuation of the second notebook. Footnote 46 According to the plan for the work Butré established in the introduction, the manuscript we have recovered and reconstructed is complete. Footnote 47

Butré conceived of Elémens d’oeconomie politique as an advanced manual intended for economic experts, or “calculateurs” (literally “computers”), as he called them. In that respect, Butré was faithfully following the intent of his old master, Quesnay, who concentrated on economic theory. This contrasts with the intentions of the other Physiocrats, who were more interested in writing for a wider public. According to Butré, his work would be of great help for enlightened rulers and their administrations: it would provide them with a method for establishing accurate public accounts and for measuring the economic consequences of policies (Butré Reference Butré1767a, notebook 1, f. 3). Strangely enough, the Physiocrat undertook this very ambitious program of research in the quiet of his provincial estate while having very little contact—except for his privileged relationship with Quesnay—with the outside world. Footnote 48

Butré began the Elémens with an exposition of the principles and definitions he uses throughout his text. The “second notebook” begins with “A brief inventory and distribution of the annual productions of a territory and their preparation for the annual consumption of the nation and foreign [trade].” It includes seven tables in total, which are—like Quesnay’s Tableau économique—based on fictitious data. We have reproduced them an online appendix to this article (Butré [Reference Butré, Charles and Théré1767c] 2016). According to Butré, the real point of his treatise was in the general method it provided; hence, it was not necessary to use real data. Footnote 49 Indeed, Butré filled the Elémens with all the main theoretical ratios one needed to implement the Physiocratic art of government in the real world. A Physiocratic government needed only to collect empirical observations and put them in place of the hypothetical figures in Butré’s blueprint. The Physiocrat invited (somewhat grandly) “our calculators to turn their research in this direction in order to deepen our knowledge of a subject-matter so fundamental to the happiness of nations” (Butré Reference Butré1767a, notebook 1, f. 3).

The Elémens d’oeconomie politique can be considered a long-term result of the work Butré had undertaken for Quesnay in the early 1760s. In effect, his new work shared significant features with one section in the ninth chapter of Philosophie rurale, in which the authors provided a method for constructing the Tableau économique and for calculating their data according to the different prices of wheat that may confront a government (Mirabeau and Quesnay Reference Mirabeau, Quesnay, Dupuy and Masne1763, pp. 384–407). Footnote 50 However, Butré did not blindly follow the Philosophie rurale and the theoretical principles of Quesnay; rather, he developed his own interpretation of these principles. At the general level, Butré did not focus on the creation of net product, as his master did, but instead investigated the detailed workings of the “economic machine.” Footnote 51 In Quesnay’s Tableau économique, the “advances” (capital investments) and the exchanges between each class take center stage. By contrast, the intra-sectorial flows were not detailed and are mentioned only in the comments of the Tableau; sometimes they are even left completely out of the picture (literally). In the Elémens, Butré was less concerned with the role of capital advances in the economy. In the introduction, he gave only short definitions of the different types of investment categories invented by Quesnay, avances primitives and avances annuelles. Conversely, he detailed the intra-sectorial expenditures for each sector in his tables and produced new and interesting insights in this regard (see section V and the online Appendix [Butré (Reference Butré, Charles and Théré1767c) 2016].)

Even if Quesnay was aware of the possible applications of his theory, one aspect that sets Butré’s work apart from his is that Butré showed a very keen interest in making his analysis as realistic as possible. Butré stressed that the figures included in his tables should not be taken at face value, but should be reworked in order to fit the data provided by an extensive survey of the wealth of the nation. Footnote 52 According to Butré, each state should organize the data collected into two synthetic documents. First, it should establish what Butré called an état constitutif; that is, “a general inventory of the annual productions of an agricultural kingdom” and of their distribution. This état constitutif uses the categories created by Quesnay and explained in the Philosophie rurale. These categories are: “the income or net product of land properties,” “the annual advances of the productive sector,” “the return of these advances,” and “the payments of all types of agricultural undertakings made on all types of lands.” This état is therefore a detailed inventory of the wealth created annually by the productive sector (agriculture). Footnote 53 This general inventory is to be completed with what Butré called the “political map of the nation”: the trade flows between different sectors of the economy, on the one hand, and the international trade of the nation, on the other. There is no equivalent to this “map” in the writings of Quesnay and his other disciples. Indeed, Quesnay did not provide a set of complete and coherent remarks on the role of international trade and, as commentators pointed out, he seemed to have changed his mind on cross-industry as well as on international trade. Footnote 54 For Quesnay, these issues had little significance as long as they did not impact the reproduction of wealth (net product). Butré had a different opinion and, as we will see in the following discussion, he believed that the level of net product was not the only variable to consider if one wanted to realize the “full potentialities” of the “economic machine” (Butré Reference Butré1767a, notebook 1, f. 8).

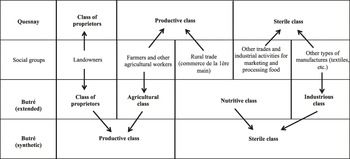

Further comparison with Quesnay’s theory shows that Butré modified one essential point: the number and composition of social classes. As we have shown in Figure 1 below, Butré did not completely rule out the functional classification proposed by Quesnay, but recombined it by moving the boundary between productive and unproductive activities. First, Butré redefined the “productive class” (classe productive). For Quesnay, this class comprised the people who worked not only in agricultural production (including the agricultural entrepreneurs or farmers), but also (and this is a point often missed by commentators) in rural trade (commerce de la première main). In other words, he included the traders who carry the agricultural goods from the location where they are produced to the market where they are first sold (Quesnay Reference Quesnay, Théré, Charles and Perrot2005, I, pp. 669–670). Footnote 55 As Marie-France Piguet (Reference Piguet1996, pp. 46–50) has shown, Quesnay’s writings define classes and their frontiers by the position each social group occupies in the circulation and production of income. Footnote 56 Hence, rural trade was productive, according to Quesnay, because it was an essential component in the valorization of agricultural production and in the creation of a net product; for, without trade, agricultural products would have no price and create no value. However, the choice of including rural trade in the productive class was controversial, since trade—like manufacturing—is a sterile activity, as the Physiocrats repeated ad nauseam. Quesnay’s solution in the Philosophie rurale was to classify rural trade under the productive sector, but at the same time he wanted to reassert that it produced no net product by itself. Footnote 57

Figure 1. Social classes according to Quesnay and Butré.

Butré’s solution is both different and interesting. Quesnay’s has two sectors, each producing different kinds of goods (agricultural for the productive sector and manufactured for the “sterile” sector), and three classes. Butré’s social theory is based on four classes instead of the three outlined in Quesnay’s Tableau économique, and he distinguishes three economic sectors, or “commerces” (trades), that produce three types of goods. Footnote 58 He disassociated rural trade from the productive class and reunited it with the other agents that process, prepare, and market foodstuffs by placing them in a new “nutritive class” (classe nutritive). Moreover, he redefined the productive class as comprising not only those who work the land, but also those who possess it, and he contrasted them to the sterile class, which includes the workers, traders, and entrepreneurs who use agricultural goods as inputs for their own economic activities (Butré Reference Butré1767a, notebook 1, f. 4–5). In moving the rural trade from the productive to the sterile class, Butré tried to overcome Quesnay’s ambiguity by erasing all the non-agricultural activities from the productive class. Moreover, by reuniting the class of landowners with the productive class, his segmentation also acquires greater political clarity. In Butré’s Elémens d’economie politique, the divide between people living on agriculture (whether from their work or from their rents) Footnote 59 and people earning their living by transforming these agricultural products into something else (either food or manufactured goods) is made self-evident. However, he also made an important change to Quesnay’s economic theory, which considers the “productive” classification as comprising only the social groups who cooperated directly in the creation of net product; and this is not the case for the landowners.

Butré also introduced a completely new idea: the products of the agricultural class cannot be directly consumed by the people; they first need to be transformed into consumption goods. Hence, agricultural goods are used as intermediary consumptions by two other classes/sectors: the “nutritive class,” which produces finished subsistence goods, and the “industrious class,” which produces manufactured goods. These two classes together form the “sterile class.” Footnote 60 The first sector is called either “productive” or “property trade” (commerce de propriété), and it produces primary goods only. The second sector, the food trade (commerce comestible), transforms raw subsistence into food fit for consumption. Footnote 61 The third sector is the industry (commerce d’industrie), which transforms raw materials into manufactured ones. Only the agricultural sector yields a net product or income that is distributed in the form of rent, tithes, and taxes (Butré Reference Butré1767a, notebook 1, f. 4–7). Like in the Philosophie rurale, the advances are made by entrepreneurs who perceive a payment as well as interest on their advances. Two final points are worth emphasizing. In the first place, although Butré evoked and defined the “primitive advances” in his text, they did not appear in the economic categories used in his tables. Footnote 62 In the second place, the return of annual advances—which were supposed to be 100% in the generic case of the Tableau économique (the so-called state of bliss)—are fixed in the Elémens at five-sevenths, which is slightly more than 70% (Butré Reference Butré1767a, notebook 2, f. 1 and 3). Therefore, Butré’s economic model introduces new features when compared with the one used by Quesnay.

V. BUTRÉ’S ECONOMIC MODEL IN MODERN GUISE

It is somewhat difficult to grasp all the meaningful aspects of Butré’s theoretical work because of the complexity of his text (to say nothing of his style of writing) and the fact that he modified Quesnay’s economic and social vocabulary. Therefore, we have decided to rewrite his general presentation on the functioning of the economy in modern economic language. In this way, we will be able to isolate more easily its salient elements and results, as well as compare them more systematically with those of Quesnay. We have based our rational reconstruction on the numerical presentation Butré gave in the “Short statement and distribution of the annual productions …” and have reproduced it in the online Appendix [Butré (Reference Butré, Charles and Théré1767c) 2016]. Through no less than seven generic tables, Butré detailed the value produced by the three sectors of an economy and their costs of production. We used these tables as a blueprint for creating a very simplified national accounting system of expenditure and income for the economy. Moreover, and for the sake of comparison with Quesnay’s analysis, our presentation of Butré’s economic model is inspired by Walter Eltis’s presentation of the Tableau économique (Eltis Reference Eltis1975).

First, Butré detailed the functioning of the productive sector in the first two tables of his second notebook online Appendix [Butré (Reference Butré, Charles and Théré1767c) 2016]. From these tables, we can write two equations that summarize the production and demand functions of the productive sector (agriculture).

Let Y p be the total income of the productive sector (1500). It is equal to the annual advances, I, which comprise non-monetary advances in subsistence, AC (food given to animals and men, which is 300); wages paid to servants and day-laborers, W p (280); and fixed capital spending, K (120), to which is added interest on the advances and the profit made by the agricultural entrepreneurs, P p (300). Finally, we have the net income (produit net) R (500).

The productive sector produces two goods: raw food and subsistence goods, SG; and primary goods, PG . Both of these are used as intermediate goods by the other two sectors, or they are exported. We add to them the part that is paid in kind for subsistence, AC. Hence, we can write the demand function for the productive sector as:

The third and fourth tables are likewise used to write the production and demand functions of the food trade (or sector). The output of the food sector is equal to the inputs in raw food, SG f , and the cost of preparation of these goods, C f , which comprise the costs of production and transportation, interest on the advances, and the profit of the entrepreneurs in this sector. The production technique is fixed, and such that each two units of raw goods used produce three units of food. The returns are constant. Finally, raw goods may be imported. Therefore SG f equals SG only if the external trade balance of the food sector is 0.

The demand for food is equal to one-half of the net income and the cost of the food and industrial sectors, and to five-sevenths of spending on servants and day-laborers. Footnote 63 To this, we must add a variable that gives the net balance of external trade in food. This variable does not figure in the tables, since the “state of bliss” corresponds to the case where the net balance of trade for all sectors is equal to 0.

We now use the fifth and sixth tables to write the production and demand function of the industry. The product of the industrial sector is equal to the sum of inputs (primary goods), PG i , and the cost of production, C i (wages, transportation, interest of the advances, and entrepreneurs’ profit). The production technique used is fixed, and such that each unit of input produces three units of manufactured goods. The returns are constant. Primary goods may be imported and, therefore, SG i is equal to PG only when the balance of trade of this sector is 0.

The demand for manufactured goods is equal to one-half of the net income and the cost of the food and industrial sectors, and to two-sevenths of spending on servants and day-laborers. Advances in fixed capital in the productive sector are spent entirely on manufactured goods. Exports and imports of manufactured goods should also be included, since the balance of trade may be positive (or negative).

Butré added another relation to this set of equations: spending on goods produced by the food and industrial sectors is always identical in the economy. Therefore, in the case of disequilibrium between the values of the goods produced by these two sectors, only variations in the external trade in manufactured goods can provide corrections that allow the economy to stay in equilibrium. Hence:

Finally, one last equation is necessary: that of the balance of trade.

A few more remarks: first, the total product of the productive sector and the structure of its costs remain identical throughout. This means that the net product is always equal to 500 in each of the economic cases that Butré considered in the Elémens d’oeconomie politique. Second, because the production technique is fixed, the output of the food and industrial sectors can be explained as a multiplier of their inputs. Hence, we can simplify the equations in this way (equations (7) and (8) are not modified) in order to reconstruct Butré’s complete economic model.

VI. GENERAL DISCUSSION

In the Elémens, Butré is not concerned with the problem of reproducing the economy per se: as mentioned above, he makes the assumption that the net product is fixed at 500 and keeps that amount throughout the whole essay. He thus sets aside the two main issues that feature in the Tableau économique; i.e., the roles of spending realized by the landowner class and of the advances realized by farmers and agricultural entrepreneurs in creating and reproducing wealth. Footnote 64 Effectively, Butré discussed neither one nor the other, since the Elémens supposes landowner spending as well as net product to be constant. Butré is interested in another set of issues that have to do with the role played by demand for raw primary goods: the size of the industrial sector and external trade. Footnote 65

The Physiocrat discussed these points throughout the nine economic problems that formed the third notebook (or chapter) and the seventeen tables he gave at the end of the second notebook. While it is impossible and, to some extent, uninteresting to detail all the cases considered by Butré, it is useful to go through the results of the first three problems in order to underscore his contribution to Physiocracy and to the history of political economy. In the first problem, which Butré labeled as “fundamental,” he calculated that the simple reproduction of his system is ensured whenever the productive sector produces twice as many subsistence goods (SG=800) as primary goods (PG=400). With this ratio, the economy reproduces itself with no external trade, as one can verify with our set of equations above. It is these two necessary conditions that make it “the fundamental ratio”: any other ratio between the two goods, SG and PG, produced by the productive sector creates disequilibrium in the economy, which can be corrected only through external trade.

This is what Butré goes on to show through the other “problems” he solved in the Elémens. Let us just consider the symmetrical cases illustrated by problems two and three, where he supposed that the ratio between the production of subsistence and primary goods diverge from its “fundamental” value, 2, that Butré found in the first problem. In the second problem, Butré hypothesizes that the productive sector produces more than one-third in primary goods, while in the third problem he makes the opposite conjecture. Butré did not try to provide general solutions to these problems: he simply adds the value of 100 livres to balance the value of primary goods (400) in the second problem; he subtracts 100 livres in the third; and he then computes the new production values for the two sectors. In the second problem, where the productive sector produces 500 livres of raw materials and 700 of raw subsistence goods, the product of the food and industrial sectors (respectively, 1050 and 825) are less than what they are in the equilibrium situation (1200 for each). Conversely, in the third problem, where the raw materials represent less than one-third of the output of the productive sector, the two outputs are more than in the equilibrium situation (respectively, 1350 and 1575). In each case the industrial sector reacts more than the food sector. This is due to the fact that the production technique of the industrial sector is more efficient—compare equations (3) and (5). Hence, the economy reaches a higher equilibrium point when it proportionally produces more manufactured goods, of which some can be exchanged against raw materials. Footnote 66 This result can be generalized as such: the more raw subsistence goods that compose the productive sector output, the higher level of production of the two transforming sectors, the limit case being the one where the productive sector produces only raw subsistence. Footnote 67

This result is not commented on by Butré but is very interesting. In effect, Quesnay had emphasized many times that the wealth of industrial nations was ephemeral and artificial, yet he was never really able (or willing) to provide a rigorous analytical demonstration of this point, most notably in the Tableau économique (Meek Reference Meek1962, pp. 282–283; Herlitz Reference Herlitz1996, pp. 5–7, 16). Butré offered such a demonstration in the Elémens. He showed that an economy could, through a process of industrialization, increase its total income to a very significant degree. Footnote 68 In the limit case mentioned in footnote 67, the value of goods produced in the industrial sector (2700) more than doubles when compared with what it produces in the state of bliss (1200), and the value of the food sector increases by one-half (1800 against 1200). This result is obtained without any rise in the net product or income produced by the economy, which depends solely on the advances made in the productive (agricultural) sector. Thus, a nation may be able to increase its population and general (monetary) wealth through industrialization, but this significant increase is more apparent than real. Because there is no increase in net product, the state is not able to raise taxes in accordance with its gross product. Hence, being unable to draw more resources from its land, it will lack funds or see the level of its debt rocket, the latter being in the case of a war with another state. Moreover, whenever the neighboring nations change their policies—for example, by prohibiting the import of manufactured goods or the export of primary goods—the fragility of the economy will be exposed and its gross product will dive. It is for this reason that Butré qualified the case of no external trade as the “maximum de constitution”—which can be translated as the maximum permitted by the economic constitution of the nation (Butré Reference Butré1767b, notebook 2, f. 3).

With the exception of some significant variations, Butré’s Elémens on the whole shared several of the traits of Quesnay’s economic system. Like Quesnay’s, his economic model had a strong normative component. For Butré, his work was to be a sort of universal toolkit that each government could use to analyze its economy. He wished, for example, to analyze cases where the expenditures of the nation in manufactured products and food are not identical, which is similar to those cases explored by Quesnay in the Tableau économique. Footnote 69 Although there is no trace of such developments in the draft that is kept at Tours, and it is probable that he never realized his initial project to its full extent, these remarks show that Butré’s ultimate goal was to complete Quesnay’s theory. For instance, Butré made it clear that:

the division of the two components of the production is susceptible of infinite variations which should make as many records of manufactures and external trade; we will develop these aspects in the three ratios that we will establish between raw food and raw materials and under which one can reunite the different variations” (Butré Reference Butré1767a, notebook 2, f. 3)

His demonstration in the second and third problems was not intended to criticize Quesnay’s theory, but to complete it in order to strengthen Quesnay’s statement that industrial wealth was fragile.

The text of Butré casts an interesting light on the oft-discussed issue of sterile activities in the Physiocratic system. Butré’s tables show that the food and industrial sectors produce wealth, wealth that in turn pays for the cost of producing manufactured goods, including the interest on advances and the remuneration of entrepreneurs. Interestingly, the industrial sector appears to be a very ‘productive’ sector. Indeed, its production technique uses less input for the same gross product than in both the food sector and the productive sector. The only specificity of the productive sector is that it creates net income that is totally disposable; i.e., it is not allocated to the payment of any aspect of production cost. In this, Butré was completely in line with his master. Footnote 70 However, his definition of the “productive trade” is different from Quesnay's: not only does he exclude transportation services from the production location to the market, but he also considers it to be unproductive to transform raw food into foodstuffs that can be consumed by the people. The consequence is that one of the fundamental issues for Quesnay—the distribution of the landowner expenditures—is secondary for Butré: whether landowners consume food or manufactured goods, they are both products of the sterile class.