1. Introduction

Nigerian English (NigE) is a second language (L2) variety of English which has been domesticated, acculturated, and indigenised (Taiwo, Reference Taiwo2009: 7; Jowitt, Reference Jowitt2019: 26), due to its co-existence with about five hundred indigenous Nigerian languages (see Eberhard, Simons & Fennig, Reference Eberhard, Simons and Fennig2019). It is the language of education, governance, law, the media, and formal financial transactions in Nigeria. Based on Schneider's (Reference Schneider2003: 271) Dynamic Model of the evolution of the New Englishes, NigE can be located at the late stage of nativisation, while recent studies show that it is on the verge of entering endonormative stabilisation (Gut, Reference Gut2012: 3; Unuabonah & Gut, Reference Unuabonah and Gut2018: 210). Although NigE is an L2, there is a growing number of young people who speak it as a first language (L1; see Jowitt, Reference Jowitt2019: 16; Onabamiro & Oladipupo, Reference Onabamiro and Oladipupo2019). NigE includes sub-varieties which are classified based on different factors such as region/ethnicity, and educational attainment (Banjo, Reference Banjo1971; Jibril, Reference Jibril1986; Udofot, Reference Udofot2003). Although Udofot (Reference Udofot2003: 204) suggests that the sub-variety used by Nigerians who have been educated in tertiary institutions should be taken as the standard variety, Jowitt (Reference Jowitt1991: 47) opines ‘that the usage of every Nigerian user is a mixture of Standard forms’ and non-standard forms. The data used in this paper are a mix of both standard and non-standard forms.

Previous studies have discussed the features of NigE at different linguistic levels, including the phonological (e.g. Jamakovic & Fuchs, Reference Jamakovic and Fuchs2019; Akinola & Oladipupo, Reference Akinola and Oladipupo2021), lexico-semantic (e.g. Owolabi, Reference Owolabi2012; Umar, Reference Umar2018), morphosyntactic (e.g. Werner & Fuchs, Reference Werner and Fuchs2017; Akinlotan & Akande, Reference Akinlotan and Akande2020), and discourse-pragmatic (e.g. Fuchs, Gut & Soneye, Reference Fuchs, Gut and Soneye2013; Unuabonah, Reference Gut, Unuabonah, Esimaje, Gut and Antia2019). At the discourse-pragmatic plane, scholars have examined pragmatic markers (Gut, Fuchs & Soneye, Reference Fuchs, Gut and Soneye2013; Oladipupo & Unuabonah, Reference Oladipupo and Unuabonah2020), stance markers (e.g. Gut & Unuabonah, Reference Gut, Unuabonah, Esimaje, Gut and Antia2019), and interjections (e.g. Unuabonah, Reference Unuabonah2020; Unuabonah & Daniel, Reference Unuabonah and Daniel2020), from a corpus-linguistic perspective. This study extends the scholarship on discourse-pragmatic features of NigE by examining an emotive interjection, mehn, which has not received scholarly attention in NigE studies. Mehn appears to be an adaptation of African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) pronunciation of man as an interjection. Although man can be used as an interjection (see Norrick, Reference Norrick, Aijmer and Ruhlemann2015: 260), a random sampling of 100 tokens of man in the Nigerian component of the Global Web-based English corpus (henceforth, GloWbE-Nig) did not yield the use of man as an interjection. In AAVE, the <a> in man is pronounced as /æ/ but this sounds like /e/ to the NigE user. Hence, a number of NigE speakers appropriate the sound as /e/ and pronounce the word as /men/. This pronunciation may have led NigE users, in written online texts, to change the spelling of man to mehn in order to differentiate it from men. An investigation of the frequency of this term in the Global Web-based English (GloWbE) corpus shows that out of 217 instances of mehn in GloWbE, 198 appear in GloWbE-Nig.Footnote 1 Two examples of the use of mehn in GloWbE-Nig are cited in (1) and (2):

(1) I am old fashion/out of touch. I could care less! # Mehn! This wins the award for best article. I've never had more fun (GloWbE 34)

(2) do nt u fink 5 or 10 years will do? Mehn! This is life imprisonment… (GloWbE 22)

Hence, this study examines mehn in NigE, from a discourse-pragmatic perspective, with a view to investigating its source, spelling adaptation, frequency, syntactic features, collocational patterns, and discourse-pragmatic functions.

2. Interjections: A discourse-pragmatic framework

Generally, interjections such as ah and oh are exclamations through which speakers and writers express their emotional and mental state of mind in interaction (see Norrick, Reference Norrick, Aijmer and Ruhlemann2015: 255; Stange, Reference Stange2016). They are culture specific and are used to achieve diverse discourse-pragmatic functions such as expressing emotions and calling attention (Stange, Reference Stange2016: 11). Interjections are largely viewed from two major perspectives, which include the views of formalists and conceptualists (Wharton, Reference Wharton2003:174; Unuabonah, Reference Unuabonah2020: 154). Formalists such as Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 74) and Crystal (Reference Crystal1995) opine that interjections are non-linguistic items that express emotions and are not part of syntactic structures at all. Conceptualists, such as Ameka (Reference Ameka1992a) and Wilkins (Reference Wilkins1992), on the other hand, opine that interjections are purely linguistic items through which language users express their feelings and thoughts in relation to the situation in which they find themselves. In this paper, interjections are viewed from a functional/pragmatic perspective, and are defined as syntactically independent, context-bound, and meaningful semi-automatic exclamations which provide insight into a speaker's emotional and mental state, and assist in the management of discourse (see Norrick, Reference Norrick, Aijmer and Ruhlemann2015: 254–257; Stange, Reference Stange2016: 20). Generally, interjections are classified based on both form and function. Based on form, they are grouped into primary and secondary interjections (see Norrick, Reference Norrick, Aijmer and Ruhlemann2015; Stange, Reference Stange2016: 8–14). Primary interjections are words such as ah and ugh, whose basic function is to serve as interjections (Norrick, Reference Norrick, Aijmer and Ruhlemann2015), while secondary interjections are interjections which primarily belong to other word classes such as nouns and verbs, but which may also be used to express the emotional and mental state of the user when they occur alone (see Ameka, Reference Ameka1992a). Examples of such interjections include examples such as boy, hell, and man.

Based on function, interjections are grouped into emotive, cognitive, conative, and phatic interjections. Emotive interjections (e.g. ouch and yuck) indicate the emotional state of the user while cognitive interjections (e.g. ah and oh) project the speaker's state of knowledge and thought at the time of utterance (see Ameka, Reference Ameka1992a; Stange, Reference Stange2016). Conative interjections (e.g. shh and psst), which may sometimes express emotions, are used to get someone's attention or demand a response from someone (Stange, Reference Stange2016: 11). Phatic interjections (e.g. mhm and eh) are employed to establish and maintain contact in communication by providing backchannels and feedbacks in ongoing discourses (Ameka, Reference Ameka1992b: 245; Stange, Reference Stange2016). Scholars have noted that some interjections may serve dual purposes depending on the context (Ameka, Reference Ameka1992b; Stange, Reference Stange2016). For instance, phatic interjections can also be emotive or cognitive. In addition, some interjections such as eh can also function as pragmatic markers (PMs) (see Montes, Reference Montes1999: 1289).

Previous accounts have investigated interjections in different varieties of English. For example, working on American English (AmE), Norrick (Reference Norrick, Aijmer and Ruhlemann2015: 257) investigates the most frequent interjections in the Longman Spoken and Written English corpus and reports that yeah is the most frequent interjection followed by well and oh, which are primary interjections. He also indentifies boy, God, and man as the most frequent secondary interjections that have developed from other parts of speech. Stange (Reference Stange2016) explores interjections used in children-adult conversations in British English, using the Manchester Corpus and the British National Corpus, while Thompson (Reference Thompson2019) investigates the use of tweaa, an Akan interjection in Ghanaian online political comments which are mainly written in English. In NigE, Olateju (Reference Olateju2006) and Omotunde and Agbeleoba (Reference Omotunde and Agbeleoba2019) explore the frequencies and functions of interjections such as oh and ah in Nigerian literary texts. Furthermore, Unuabonah (Reference Unuabonah2020) investigates different types of bilingual interjections such as na wa, ehn, ehen, and shikena in the GloWbE corpus while Unuabonah and Daniel (Reference Unuabonah and Daniel2020) examine five emotive bilingual interjections: haba, kai, chei, chai, and mtchew which are borrowed from indigenous Nigerian languages into NigE. Although mehn appears in the sub-corpus of 50 U.S.-Nigerians in the Nairaland 2 corpus used by Honkanen (Reference Honkanen2020), she does not describe the interjection in her study. Hence, there is limited knowledge and understanding of the frequency, syntactic patterns, and functional usage of mehn in NigE. Thus, this study seeks to answer the following questions:

(1) What are the source, spelling adaptation, and frequency of mehn in NigE?

(2) What are the syntactic features, collocational patterns and discourse-pragmatic functions of mehn in NigE?

3. Data and method

The data for this study were extracted from GloWbE-Nig, which contains 42,646,098 words, collected from different Nigerian websites and pages, such as discussion forums, blogs, and online newspaper reports (Davies & Fuchs, Reference Davies and Fuchs2015). GloWbE itself contains about 1.9 billion words, comprising English language usage from 20 countries where English is used as an L1 or L2. This allows a researcher to compare the frequency of an item across the different national varieties. GloWbE (with each of its sub-components) comprises 60% of informal blogs and newspaper commentaries which are contexts in which interjections are likely to be used, and in which writers are likely to use words innovatively. As noted also by Norrick (Reference Norrick, Aijmer and Ruhlemann2015: 249), interjections appear mainly in dialogues, and these informal blogs and newspaper commentaries provide platforms for online users to make comments which involve polylogues among different writers and bloggers (see Bondi, Reference Bondi2018). The remaining 40% generally contains formal texts such as newspaper reports, where the use of interjections will likely be limited. Although scholars have suggested that writers from other countries may post comments on websites that belong to a different country (see Nelson, Reference Nelson2015), the high concentration of the tokens of mehn in GloWbE-Nig indicates that it is largely used by Nigerians in online-based writing.

GloWbE was searched using the analysis software on its website (see Davies, Reference Davies2013). The items, mehn, menh, and mhen were initially identified by the author, based on familiarity with these words in GloWbE-Nig. Based on this, the corpus was searched using mehn*, menh*, and mhen*, in order to retrieve other spelling variants. This yielded variants in which the last letters <n> or <h> were replicated, as exemplified in (3) and (4), respectively, as well as cases in which there was no space between the full stop after mehn and the succeeding word, as cited in (5):

(3) I don't kw but as for femi Adebayo's children, mehnnnn I salute d guy 4 dat (GloWbE 1)

(4) two horns with 4 sons won this election,, and become there president, menhhhh, (GloWbE 1)

(5) U better think before u post comments mehn. I think ur the one who doesn't understand (GloWbE 1)

The retrieved data were manually searched in order to remove cases in which mehn appeared in utterances made in Nigerian Pidgin (NigP), as indicated in (6), indigenous Nigerian languages, as shown in (7), and repetition of posts due to the copying of posts by other users, as depicted in (8). Other cases where mehn was not used as interjections were also removed, such as when it referred to names of things, as exemplified in (9).

(6) I cant wait to move home' bla bla.... but omo mehn plenty tins dey wen I go miss oo.... (GloWbE-Nig 61)

(7) there is something wrong wit it period. # Nna mehn... egwu na atuzim badddd!!! (GloWbE-Nig 8)

(8) Enjoy o November 28, 2012, 01:59:37 PM # Dr.MaxkDAVT: Mhen! Its been a long time I stepped into this hood... (GloWbE 10)

(9) is Brian Merriman (1747 -- 1805) author of the frequently translated Cirt an Mhen Oche (Midnight court). (GloWbE 85)

The extracted data underwent both quantitative and qualitative analysis.

4. Results

As earlier indicated, mehn in NigE appears to be an adaptation of AAVE's pronunciation of man as an interjection. It is largely written as mehn (164 tokens), as cited in (1). On few occasions, it is written as mhen (10 tokens), mehnn (7 tokens), mehnnn (6 tokens) and menh (5 tokens). Other variants appear only once or twice, which indicates that mehn is the preferred spelling for mehn. Thus, altogether, there are 204 tokens of mehn in GloWbE-Nig. Its normalised frequency calculated at per million words (pmw) is displayed in Table 1. The syntactic features, collocational patterns, and discourse-pragmatic functions of mehn are discussed in the following sub-sections.

Table 1: Frequency and syntactic position of mehn in GloWbE-NigE

4.1 Grammatical features and collocation patterns of mehn in NigE

Mehn can appear at clause-initial, clause-medial and clause-final positions, as indicated in (10), (11), and (12), respectively. As shown in Table 1, mehn is most frequent at clause-initial position, followed by clause-final position, but rarely occurs at clause-medial position. This indicates that it prefers clause-initial position.

(10) Enjoy o November 28, 2012, 01:59:37 PM # Dr.MaxkDAVT: Mhen! Its been a long time I stepped into this hood… (GloWbE 1)

(11) “Whatever it's gon na take mehn to keep moving, we do it. That's what's up (GloWbE 161)

(12) Abeg, the rest of the musicians are just as good mehnn and some are even better than Tuface (GloWbE 11)

In addition, mehn occurs with declaratives (N = 175), imperatives (N = 13), exclamatives (N = 9), and interrogatives (N = 7), as shown in (12), (13), (14), and (15), respectively. This indicates that it occurs more with declaratives than other clause types.

(13) go out there represent this f*****g world menh, u fake guys should better wake up, (GloWbE 7)

(14) doesn't agree with u is a fhool a gay, an idiiot etc. Mehn, what a place to live in. Well mr no name, if u (GloWbE 139)

(15) this one is just out there the biggest of them all.. mehn are you tone deaf or something tonto, (GloWbE 147)

As a discourse-pragmatic item, mehn collocates with other discourse-pragmatic features such as interjections (e.g. lol and shit), as seen in (16) and (17), and discourse markers (e.g. and and but), as shown in (18) and (19).

(16) and sure nothing happened to them. But I'm yet to bell that cat mehn. Lol # (GloWbE 86)

(17) Because I was still struggling. Still thinking: " Shit mehn, I'm an R &B; artiste, (GloWbE 153)

(18) ‘m disappointed in this guy, he's joined the band wagon. " And mehn we just kept pushing (GloWbE 154)

(19) do nt want to sound self righteous o, because times have changed, but mehn, with this repairs of the 3rd mainland bridge, things will worsen. (GloWbE 70)

Mehn also co-occurs with address terms such as personal names, and kinship/solidarity terms such as omo, as depicted in (20) and (21), respectively. Omo is the Yoruba term for a ‘child’; however, it is increasingly used as an address term to indicate solidarity among peers.

(20) Ghana (well they are originally from Ghana.) # mehn Ginika, wtf did u jst type? did u X proof read b4 posting? (GloWbE 190)

(21) the differrence was so clear lyrically # Omo mehnn, this guys are trying it isn't easy (GloWbE 2)

4.2 Discourse-pragmatic functions of mehn in NigE

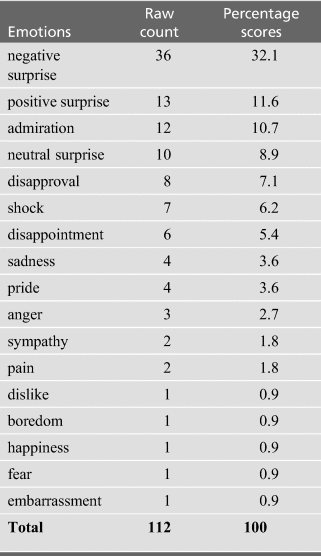

Mehn functions as a secondary emotive interjection (N = 112; 54.9%), and sometimes, it also performs emphatic functions (N = 92; 45.1%). As an emotive interjection, it is used to express surprise, admiration, pride, boredom, sympathy, pain, fear, sadness, disappointment, and shock. The distribution of these different emotions is presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Distribution of emotions expressed by mehn in GloWbE-Nig

Mehn can be used to express feelings of surprise, which can be positive, negative or neutral (see Stange Reference Stange2016: 68), as exemplified in (22), (23), and (24), respectively:

(22) … Im proud of them… They lost yh but mehn!!!! they did play good and US shld better be watchful (GloWbE 76)

(23) the morning and taught of how to change the name of an institution… omo mehn.. that man has to be taken to a psychiatric hospital… Nigeria worst president (GloWbE 65)

(24) and wants me pregnant ASAP? If possible b4 the wedding sef. Mehn see someone planning your life for you, while you look like a spectator (GloWbE 88)

In (22), the writer uses mehn to indicate positive surprise at a football team that s/he was proud of, and that s/he believed had played a good game, even though the team had lost a game. In (23), the strong surprise expressed by the writer is negative as s/he opined that the President was the worst one ever because the President suddenly thought of changing the name of an institution (that is, the University of Lagos). In (24), the surprise expressed is neutral as the writer simply marvels at another netizen for making plans for the writer.

Mehn can also be used to indicate feelings of admiration, pride, and sadness, as exemplified in (25), (26), and (27), respectively.

(25) There were a few times that I had to blush because mehn… They were soo cute. Knowing how to dance is such a blessing. (GloWbE 100)

(26) The healing process had begun! # Mehn! Was I proud of myself! (GloWbE 2)

(27) # Mehn sometimes i feel bad becos of wat niger is turning into, bribery and (GloWbE 37)

In (25), mehn is used to express feelings of admiration that the writer feels towards some third parties, as they consider them to be very cute. In (26), the writer exclaims that s/he is proud of himself or herself and uses mehn to indicate the feeling of pride, while in (27), the writer employs mehn to indicate feelings of sadness, as s/he states that s/he feels bad about the situation of things in Nigeria.

Mehn can also be used to indicate feelings of disapproval, disappointment, and shock, as illustrated in (28), (29), and (30), respectively.

(28) Did you say Adam lived 930years. Mehn, you are worse than a slowpoke to believe such an exaggeration (GloWbe 107)

(29) # Mehn, dt bitch called Muna really dissapointed me, I used to like dt bitch (GloWbE 40)

(30) u abandon such good man for a Married Man??????Mehn, words fails me! May God grant Emeka strength to go thru the heartbreak (GloWbe 6)

In (28), mehn is used to express feelings of disapproval at the words of another person who stated that Adam had lived for 930 years, while in (29), mehn is used to convey disappointment, due to the actions of a friend. In (30), the writer is shocked at the actions of a lady who jilted a man, and uses mehn to express this shock.

In some cases, in addition to expressing emotion, mehn is used to emphasise the proposition contained in an utterance, and in this way, it shares similar meanings with emphasis PMs, such as really and indeed. The distribution of the propositions/speech acts emphasised by mehn is presented in Table 3. Some examples are also discussed.

Table 3: Distribution of speech acts emphasised by mehn in GloWbE-Nig

Mehn can be used to emphasise assertion, evaluation, and advice, as cited in (31), (32), and (33), respectively:

(31) Like her or hate her woman is balling nd making money mehn, as for d one saying jamaica tiny rock? (GloWbE 16)

(32) Do you play chess? Menh work these days is hectic, how do you unwind? (GloWbE 4)

(33) date sumone better than him n don't hesitate to rob it on his face mehn. # Naaaaaah, Riri dnt hate, (GloWbE 21)

In (31), the writer uses mehn to emphasise his/her assertion that a particular woman is prospering financially. In (32), the writer utilises mehn to emphasise his/her evaluation of how hectic the days have become, while in (33), the writer employs mehn to emphasise the advice s/he is offering.

Mehn can also be used to emphasise desire/wishes and quotations, as exemplified in (34), and (35) respectively:

(34) God shuld just help us mehn that every1's prayer for this Nigeria (GloWbE 189)

(35) And I was like mehn, " I can't imagine a professor in my state, Imo state worrying (GloWbE 113)

In 34, the writer employs mehn in order to emphasise his/her desire or wishes that God would help Nigeria, which s/he believes is the prayer or desire of every Nigerian. In (35), the writer uses mehn to emphasise the upcoming quotation. In all three examples where mehn is used to emphasise quotations, mehn is preceded by the new quotative, be like (see Ogoanah & Adeyanju, Reference Ogoanah and Adeyanju2013: 49).

5. Discussion

This paper set out to explore the source, spelling stability, frequency, position, collocational patterns as well as discourse-pragmatic functions of mehn in NigE. In relation to its source, the adaptation of AAVE's use of man as an interjection may be due to the influence of popular culture as Nigerians watch a lot of American films, and some model the accent or speech styles of some American actors (see Igboanusi, Reference Igboanusi2003: 601). In a number of cases, such speech styles are used in Nigerian movies to model Americans or Nigerians who have lived abroad for a very long time, and who might have just returned to the country, a situation which occurs in the Nigerian socio-cultural context, where a number of Nigerians travel to the United States, in order to seek greener pastures. Some return to the country to stay or visit their families. In a number of cases, the speech styles of such Nigerians do change, and these often influence the speech styles of their interactants, especially the young ones who admire these returnees. As Sauciuc (Reference Sauciuc2006: 269) notes, interjections are easily adopted by speakers in a short period of time, and young Nigerians, in particular, would have adopted the AAVE's use of man as an interjection. This further confirms the influence of general AmE and AAVE on NigE (Awonusi, Reference Awonusi1994; Igboanusi, Reference Igboanusi2003; Honkanen, Reference Honkanen2020; Akinola & Oladipupo, Reference Akinola and Oladipupo2021). As Igboanusi (Reference Igboanusi2003: 603) opines, Nigerians have a positive attitude towards Americanisms, as there is ‘the rising popularity of AmE accents and usages’ in NigE. In addition, other kinds of words from AAVE occur in NigE, such as beef (a conflict) and homeboy (a friend), (see Honkanen, Reference Honkanen2020: 178).

In relation to spelling stability and adaptation, the spelling reflects the NigE distinctive pronunciation of AAVE man. As it has been noted, the internet provides the space for innovative use of language (Honkanen, Reference Honkanen2020: 267), and one of the techniques of Nigerian internet users is to write words as they are pronounced. The insertion of <h> in men might be an extension of one of the processes of anglicisation in NigE, where young people, in particular, insert <h> in Nigerian names (see Faleye & Adegoju, Reference Faleye and Adegoju2012: 15). Although the word men is already an English word, writers may have adopted this process in order to create a new spelling for the interjection, which will distinguish it from men. This is a situation that also affects interjections that are borrowed from indigenous Nigerian languages into NigE, as some of the interjections are anglicised by adding <h> to the interjections, as seen in bilingual interjections such as ehn, shikenah, and na wah (see Unuabonah, Reference Unuabonah2020: 172). Also, the orthography of mehn may have been influenced by internet sites where users have the freedom to spell words in new ways without correction. Such spelling variants may become fossilised at some points. In addition, the mehn spelling is fairly stable since only a few tokens are spelt as mhen or menh. Moreover, the innovative respelling of words to capture phonological changes peculiar to NigE adds to the credence that NigE is on the verge of entering the stage of endonormative stabilisation (Schneider, Reference Schneider2007; Gut, Reference Gut2012: 3).

Based on the frequencies of mehn both in GloWbE and in GloWbE-Nig, it is evident that the use of mehn as an interjection is peculiar to NigE. However, with a few scattered tokens in other varieties in GloWbE, especially in the Ghanaian component of GloWbE, there might be a gradual increase in the use of mehn in other varieties, especially Ghanaian English, which shares close social ties with NigE. Although the frequency of mehn is quite low compared to other high frequency interjections such as oh or ah in GloWbE-Nig, mehn occurs more than a number of interjections such as aw or ow which share relatively similar functions with mehn in NigE. Mehn also occurs more than several bilingual interjections earlier studied except mtchew and haba (see Unuabonah & Daniel, Reference Unuabonah and Daniel2020: 69). This might also be the case as mehn expresses negative, neutral and positive emotions. The frequency and peculiarity of mehn to NigE has implications for the codification and standardisation processes of NigE, as such a word may be included in NigE dictionaries.

In relation to syntactic features, mehn's preference for clause-initial position is largely linked to its exclamatory (semi-automatic) function (see Stange, Reference Stange2016: 20), while mehn's occurrence at clause-final position is largely linked to its emphatic function. As it has been noted elsewhere, the clause-final position is the preferred position for other NigE emphatic PMs such as o, jare and fa (Unuabonah & Oladipupo, Reference Unuabonah and Gut2018, Reference Oladipupo and Unuabonah2020). In addition, mehn occurs with all clause types, and its co-occurrence with exclamations foregrounds its exclamatory functions.

As regards collocational patterns, mehn co-occurs with a wide range of other discourse pragmatic features, such as discourse markers, interjections, and address terms, and this is largely linked, not only to its function as an emotive interjection, but to its preference for clause-initial position. It is noted that mehn rarely collocates with other discourse-pragmatic features at clause-final position. This confirms the findings of Unuabonah (Reference Unuabonah2020: 172) that function and syntactic positioning influence collocational patterns of NigE interjections.

With regard to discourse-pragmatic functions, it is evident that mehn is quite multifunctional as it can be used to express different kinds of emotions such as surprise, pride, sadness, sympathy, pain and shock. Thus, it is unlike a number of NigE interjections that only express positive or only negative emotions. Apart from expressing emotions, it performs emphatic functions like emphasis PMs, such as really or indeed. As noted by Montes (Reference Montes1999: 1289), interjections can also function as PMs, and this is also evident in some NigE interjections, such as ehn and ehen (see Unuabonah, Reference Unuabonah2020). One interesting function is the use of mehn to emphasise quotations, as shown in (35). In this case, mehn behaves like some discourse-pragmatic features, such as oh and look, which are used to introduce and emphasise quotations, and which ‘anchor the utterance to the original situation’ (Holt, Reference Holt1996: 237; Brinton, Reference Brinton2008). Mehn's multifunctional roles foreground the meaning potential of discourse-pragmatic features, indicated by Aijmer (Reference Aijmer2013) and Norrick (Reference Norrick, Aijmer and Ruhlemann2015).

6. Conclusion

This study has examined the source, spelling adaptation, frequency, syntactic features, collocational patterns, and discourse-pragmatic functions of mehn in NigE. The results show that mehn is a secondary emotive interjection, which may have developed from the use of man as an interjection, especially in AAVE. The results, thus, foreground the continuous influence of AmE (in this case, AAVE) on NigE, as well as the influence of the internet on language usage. Mehn largely occurs in informal texts such as online commentaries which mirror spoken dialogues. The results also show that mehn expresses negative, positive, and neutral emotions, such as surprise, admiration, sympathy, pain, and shock; mehn also performs emphatic roles. In all, this study has contributed to the discourse-pragmatic features of NigE, an area that has been largely neglected by NigE scholars (see Jowitt, Reference Jowitt2019: 107). Scholars have noted that NigE may influence other varieties, especially other West African varieties of English, due to a number of reasons including the influence of the Nigerian film industry, Nollywood, whose films are shown on the internet and across Africa through cable television (see Unuabonah & Oladipupo, Reference Oladipupo and Unuabonah2020: 14). Future studies may, thus, address other discourse-pragmatic items that have developed in NigE or the possible spread of mehn to other second language varieties of English.

Acknowledgements

The author appreciates the insightful comments of the journal editor and two anonymous reviewers. The author also appreciates the critical comments of Dr Rotimi Oladipupo of Redeemer's University as well as colleagues who were present during the presentation of parts of this paper at the 1st African Pragmatics Conference, held at the University of Ghana, Legon, in February, 2020.

FOLUKE OLAYINKA UNUABONAH obtained her PhD from the University of Ibadan, Nigeria, and lectures at the Department of English, Redeemer's University, Nigeria. Her areas of research include (multimodal) discourse analysis, and (corpus) pragmatics. She has published articles in Discourse & Society, English Text Construction, Pragmatics & Society, Pragmatics, Text & Talk, Journal of Argumentation in Context, and Corpus Pragmatics. Together with colleagues, she is compiling a historical corpus of English in Nigeria. Email: unuabonahf@run.edu.ng

FOLUKE OLAYINKA UNUABONAH obtained her PhD from the University of Ibadan, Nigeria, and lectures at the Department of English, Redeemer's University, Nigeria. Her areas of research include (multimodal) discourse analysis, and (corpus) pragmatics. She has published articles in Discourse & Society, English Text Construction, Pragmatics & Society, Pragmatics, Text & Talk, Journal of Argumentation in Context, and Corpus Pragmatics. Together with colleagues, she is compiling a historical corpus of English in Nigeria. Email: unuabonahf@run.edu.ng