This book is about a daily global puzzle. How do vulnerable people facing droughts, floods, or pollution make water choices each day? They are the people at the very sharp end of the climate crisis compounded by economic instability, weak governance, and public health shocks. They often feature in the news as disaster strikes as homes and livelihoods are brutally washed away, local rivers brim with disease and rubbish, or rain fails to fall for months and months on end. With limited resources and assistance, over two billion marginalised people have to make daily choices to find and use water for drinking, cooking, washing, cleaning, hygiene, or watering livestock. We believe by better understanding these daily water choices that we can design and shape better policy and interventions to help improve water security for hundreds of millions of people in Africa and Asia.

As two researchers who have conducted many households surveys, interviews, and focus group discussions over two decades in more than a dozen countries, we know the strengths and limits of existing research methods. We have been inspired by new ideas and approaches, such as the compelling book, Portfolios of the Poor, which charted the daily expenditure of people earning less than USD 2 per day in Bangladesh, India, and South Africa. The findings revealed the incredible sophistication of 250 families managing their limited and variable income based on fortnightly interviews. The insights provided clear and actionable evidence for better policy and practice that has been taken up widely since. It gave us a framework to see how these methods might be adapted and advanced to create a suitable water diary method.

Water diaries are not a new idea. Researchers have previously implemented the diary method to monitor water behaviour in resource-poor settings. However, limited resources constrained the scope and ambition of these earlier studies. We were fortunate to be in a long-term and well-funded research programme that could allow us to be more ambitious and document a full year of the daily water choices of hundreds of families in multiple countries.

However, it was not only intellectual curiosity that started the diary work. Our research programme faced a major headache. The REACH Programme was committed to improving water security for 10 million poor people by understanding how climate and hydrological systems interact with water needs for drinking water, irrigation, industry, and the environment. The idea of water security is precisely about these interactions between water resources and water services and the distribution of impacts for different people across space and time. Our interdisciplinary research depended on bringing together ideas, methods, and data to examine water insecurity in different geographies facing significant but uncertain threats. While our climate colleagues could roll out hourly data on temperature, rainfall, and more, the social scientists struggled to rustle up one household survey in a year. The water diaries provided a bridge across the data gap.

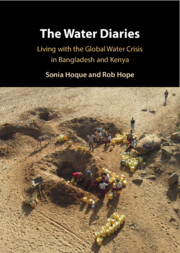

In 2017, we started the water diary work in Kenya. We had worked there for many years in a remote and rural location about 160 km east of Nairobi. Hot, dry, and dusty, it was a good place to pilot the method and develop our plans with good local partners. Over the next two years, we rolled out the diaries in three other locations in Bangladesh and Kenya. The choice of countries reflected our interests, expertise, and local partner networks, as well as providing a diversity of water insecurity challenges from river pollution in Dhaka to cyclonic storms in coastal Bangladesh, and the drought cycles of rural Kenya. There is no claim that these locations represent water security globally, though the geographies capture many common and growing challenges around the world.

The methods we developed may be of interest to researchers and students. As teaching staff at the University of Oxford, we share and discuss these methods as part of our teaching on research methods for our postgraduate students. We have written a methodological chapter that some readers may wish to turn to first to better understand how the data were generated. The method has generated wider interest with UNICEF applying the method in refugee camps in Ethiopia. Other groups may find the approach to be applicable to their work on tracking water collection, use, and expenditure in a simple and relatively low-cost fashion.

For the policy community, the book poses questions on current practices and future strategies. Monitoring water security is a difficult process. The Water Diaries reveals how daily practices are more nuanced and variable than standard data from household surveys. The progress in global monitoring of drinking water security is to be applauded, but there are limitations, particularly with the complex synergies between seasonal and sub-seasonal rainfall patterns and daily water use. As the climate crisis unfolds, this is a major policy gap to credibly and effectively direct climate finance to the most vulnerable. The slippery slope of pedestrian policy is to focus on valuing what we measure, rather than measuring what we value. The Water Diaries provides unique access to daily water practices that contributes to a deeper understanding of social and cultural practices that do not neatly align to policy imposed from above.

We hope this book provides ideas and insights to understand and respond more effectively to the hundreds of millions of people living through a daily water crisis across the world. The positive news is much can be done to improve people’s lives. New initiatives and investments have emerged in response to the partnerships we have shared with governments and donors in the geographies where we work. We sincerely hope that more can be scaled up fairly and quickly to improve and sustain water security for everyone.