I

This article revisits the history and the accounting of Italian war debts in the inter-war period against the rancorous international context that made it difficult to resolve simultaneously reparations imposed on Germany at Versailles and inter-Allied war debts. Italy, part of the Alliance, was burdened with a large foreign debt, an experience shared by other European countries such as France, Germany and the UK. A reduction of Italian public debt came in the mid 1920s following two restructuring agreements, one with the US in November 1925 and the other with the UK in January 1926. These two agreements wiped more than 80 percent of Italian war debts (Toniolo Reference Toniolo1980, pp. 105–7; Salvemini and Zamagni Reference Salvemini and Zamagni1993, p. 153). According to Salvemini and Zamagni (Reference Salvemini and Zamagni1993, p. 152) and Francese and Pace (F&P for short, Reference Francese and Pace2008, p. 17), the remaining portion of war debts was eliminated at the Lausanne agreement of 1932. Italy, instead, defaulted de jure in 1934 against the US, two years after Lausanne. We reconstruct the Italian foreign debt series to conform to the new dating. Our values are much lower than F&P's starting in 1926. The reason is that F&P do not take into account the large haircut Finance Minister Volpi extracted from the London debt accord of 1926. Then, beginning in 1932, the values of our series exceed F&P's because we date the formal exit date of the US war debt to 1934, whereas F&P date it to 1932, at Lausanne.

The literature on Italian war debts can be divided in two groups. The first consists of quantitative works whose objective is to reconstruct total public debt and, in the process, to deal also with its foreign component, mostly war debts. In this group, we include: Ministero del Tesoro (1988, p. 89), which presents data on foreign debt as a ratio of GDP and concludes that this debt was eliminated in 1925; Spinelli (Reference Spinelli and Spinelli1989), who, in his treatment of domestic debt for the years 1861–1985, has an appendix on foreign debt for the years 1917–60; Salvemini and Zamagni (Reference Salvemini and Zamagni1993) and F&P (Reference Francese and Pace2008), who offer an extensive discussion of foreign debt.Footnote 1 The latter paper presents the latest available foreign debt series used by the literature. The second group is qualitative and includes authors whose main task is to discuss fascist economics and, in the process, touch upon the issue of war debts. For example, De Felice (Reference de Felice1968, pp. 225–6), in his massive historical work on Mussolini, dedicates two pages to Italian foreign debt restructuring; Romano (Reference Romano1997, pp. 131–41), in his biography of Volpi, has an entire chapter on war debts; Migone (Reference Migone1980, pp. 99–151) includes a chapter on foreign debt as part of his treatise on diplomatic and economic relationships between the US and Italy during the fascist period; and Asso (Reference Asso1993) reconstructs the history of Italian foreign borrowing and lending from 1919 to 1931.

Yet, the existing literature, as a whole, does not give a comprehensive account of the Italian default on foreign debt after World War I and a reconstruction of the corresponding time series in a manner consistent with the unfolding of relevant historical events. The qualitative literature, on the one hand, is vague and incomplete on the treatment of Italian war debt and the developments of the actual default. The quantitative literature, on the other hand, with the significant exception of Reinhart and Trebesch (Reference Reinhart and Trebesch2014),Footnote 2 overplays the success assigned to the Lausanne conference and concurs that Lausanne represents the final act of both war reparations and war debts. But this conference was more a forum, where participating countries argued the case for debt cancellation, than an act of forgiveness of war debts by creditor countries. The US, the major creditor country, was not present at Lausanne, reflecting in part the American public's mood of opposing any form of international cooperation. An isolationist climate permeated the country, even though, after Lausanne, several unsuccessful attempts were made by the debtor countries to renegotiate the terms of their debts. The French, with an overwhelming vote of their Chamber of Deputies, repudiated war debts on 14 December 1932, approximately six months after Lausanne. The British, in the certain knowledge that they would receive no further payments from their own debtors, decided to suspend all debt payments on 15 June 1934, a year and half after Lausanne. The Italians followed the French and the British with a de jure default in December 1934, two years after Lausanne. All other debtor countries, with the exception of one, followed suit in good order.Footnote 3 It should be noted that the Italian default is scarcely known in the literature. Even as recent a book as Cottarelli's (Reference Cottarelli2018, p. 75) argues that Italy, despite its long history of high public debt, has never defaulted since political unification.

We make three contributions in the article. First, we provide a careful and documented treatment of Italian war debts, drawing not only from new archival Italian government documents, but also from American and British foreign policy documents. Second, we construct a new series of Italian foreign debt from 1925 to 1934. We compare our series with F&P's, which is the current standard in the literature (e.g. Jordà, Schularick and Taylor Reference Jordà, Schularick, Taylor, Eichenbaum and Parker2017; Reinhart and Trebesch Reference Reinhart and Trebesch2014). Our foreign debt series, as we have already indicated, differs significantly from F&P's. Furthermore, for F&P Lausanne represents the cancellation date of US and UK war debts. For us, instead, US debt cancellation occurs in June 1934, the date of Italy's formal default. For the UK debt, the story is more complex because there was no formal default but rather a de facto debt suspension. The UK government, for political reasons, did not agree on ‘debt forgiveness’ at Lausanne, but at the same time it never pushed for the resumption of full payments with its own debtors. The reason is that a resumption request by the UK would have strengthened a corresponding demand by the US on the UK. Therefore, the Lausanne conference can be reasonably considered as the terminal date of the Italian debt vis-à-vis the UK. Third, our account of the restructuring of the war debt with the US in 1925 can be interpreted as an excusable partial default.Footnote 4 The Americans granted Italy a very deep haircut because they recognized that the country had fallen into a state of decline and did not have the capacity to repay. The US decision was facilitated by geopolitical considerations, namely that Mussolini could ensure social stability at home and facilitate US economic expansion in Europe.

The structure of the article is as follows. Sections ii discusses war reparations and war debts, the dominant issues at the Lausanne conference, and the relationship between the US and the UK and France with respect to debt forgiveness. Section iii deals with the treatment of Italian war debts. Section iv looks at the data and compares our reconstruction of the foreign debt time series with that by F&P. Section v, in addition to summarizing the main results of the article, advances a different interpretation from the literature on war debt cancellation and provides an assessment of the transparency of official data on Italian foreign debt between the two world wars. The Appendix includes official Italian, French and British documents pertaining to default or debt suspension, and additional data.

II

After World War I, the Versailles outcome set the stage for a bitter and self-defeating economic climate that debilitated international cooperation and slowed economic growth (Keynes Reference Keynes1919). The issue of war reparations and inter-Allied debts moved to center stage immediately after the end of hostilities and remained there for almost a decade and a half.

Numerous international conferences and meetings were organized on war reparations: first to hear exaggerated claims of what Germany should pay; then to determine what Germany could pay, which led to the creation of the Dawes Plan of 1924 and the Young Plan of 1929, and finally to a planned settlement with the Lausanne conference of 1932.Footnote 5 According to the Dawes Plan, Germany would have had to pay approximately 12.5 billion marks, an amount later reduced by the Young Plan. In reality, from 1 September 1924 (the start of the Dawes Plan) to 30 June 1931 (the start of the Hoover Moratorium), Germany paid 11,159 million marks of war reparations.Footnote 6 In Lausanne, as we will see below, the position of all Allied powers, except the US, was that reparations and debt payments were to be linked (Moulton and Pasvolsky Reference Moulton and Pasvolsky1932; Kent Reference Kent1989).

In the bitter history of war debts and war reparations, a central point was the Hoover Moratorium, a one-year interruption on payments, officially proposed by US President Herbert Hoover on 20 June 1931. Allied countries had borrowed from the United States under the Liberty Loan Act of 1917: bonds were sold in the United States at an interest rate of 5 percent against which Allied powers signed certificates of indebtedness with the same terms as the Liberty securities. From 1917 to 1922 total borrowings amounted to $9,387 million, of which $4,137 million by the UK, $2,933 million by France and $1,648 million by Italy. These three countries accounted for 93 percent of total dollar war debts (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen1987, table 5). By 1934, with arrears, total dollar war debts had grown to $11,734 million (Table 1).

Table 1. Unpaid war debts owed to the US and the UK in summer 1934

Source: Reinhart and Trebesch (Reference Reinhart and Trebesch2014, p. 20). The original source of the first column is US Treasury (1935, p. 391).

Initially, the moratorium was well received by the US public and by the financial markets, based on an expectation that it could boost a languishing American trade (Lippmann Reference Lippmann1933, p. 5). But, a few months later, in the very midst of the Great Depression, the public's mood turned sour and opposed any form of international cooperation. Symptomatic of the rising isolationist mood in the country, Representative Cross of Texas declared: ‘Let Europe run her own affairs’ (Lippmann Reference Lippmann1933, p. 9). The moratorium was eventually ratified by the Congress (December 1931), but a joint Congressional resolution clearly expressed the American position against the cancellation of war debts.Footnote 7

The upcoming Lausanne conference, held from 16 June to 9 July 1932, had as its main goal to provide a definitive settlement on war reparations, although the widespread sentiment across governments was that the critical issues were broader than reparations and consisted of inter-Allied war debts and the balance of power between European States and the United States. The final Lausanne agreement reached three conclusions (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 1932, pp. 334–50): (a) a final payment by Germany of 3,000 million Reichsmarks ($714 million), to be placed in a general fund for European reconstruction; (b) the floating of 5 percent bonds, guaranteed by the Reich, to cover this amount; and (c) the deposit of these bonds with the Bank for International Settlements and their eventual sale only when Germany's economic situation made it practicable.

On the surface, the Lausanne agreement seemed to have put an end to German war reparations and inter-Allied war debts; it did not do so for three fundamental reasons. The first is that the agreement was actually never ratified (Toniolo Reference Toniolo2005, p. 131), leaving war reparations and war debts in a state of limbo. The second is that a side agreement among the representatives of Belgium, France, Italy and the UK made the ratification of the Lausanne agreement conditional on a satisfactory settlement of war debts between these four countries and their creditors, essentially the US (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 1932, p. 347).Footnote 8 The third is that the US, the major creditor country, was not present in Lausanne. In sum, the conference should be seen as a forum for debt cancellation rather than as an explicit or implicit act of forgiveness of war debts by creditor countries.

It should also be mentioned that the publication of the four-country side agreement prompted a public outcry in the United States, where it was widely interpreted as an attempt by the European debtors to create a ‘united front’ against the American creditor. The climate of suspicion underlying Lausanne was so strong that it induced President Hoover to make public a private letter in which he had said that ‘the United States has not been consulted regarding any of the agreements reported by the press to have been concluded recently at Lausanne and that of course it is not a party to, nor in any way committed to, any such agreements’ (Lippmann Reference Reinhart and Trebesch1933, pp. 145–6). While the agitation in the US did not last long, the issue of war debts kept festering among the public and the politicians.

Several attempts were made to renegotiate the terms of the war debts. The first occurred in November 1932 when the British requested to suspend the payment due on 15 December. The British request was quickly followed by similar actions by France, Belgium, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Latvia and Lithuania (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen1992, p. 319). When the US government denied the requests, the UK decided to make a timely payment ($95,550,000 in gold), whereas France deferred payment and thus entered in default (Lippmann Reference Reinhart and Trebesch1933, pp. 170–5). When the next payment fell due in June 1933, the governments of the UK, Czechoslovakia, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania made token payments (Reinhart and Trebesch Reference Reinhart and Trebesch2014, p. 24). In September 1933, the UK resumed negotiations on war debts with the US, while making token payments on interest.Footnote 9 The negotiations failed again. According to Self (Reference Self2006, p. 179), ‘the British were handicapped in their planning for the forthcoming talks by an astonishing degree of uncertainty about what the Americans actually wanted’. In fact, in reading the diplomatic documents on British foreign policy, one has the impression that President Roosevelt was sympathetic to a revision of British war debts, but he was also fully aware that US voters and the majority of Congress were not.Footnote 10 The American electorate and their representatives were much more isolationist than the leaders who privately acknowledged that war debt repayments were an obstacle to the resumption of economic growth in the world.Footnote 11 According to Sir Frederick William Leith-Ross, chief economic adviser to the UK government, who met Roosevelt on 1 November 1933, ‘[the President] can get anything he likes through Congress, but … he is evidently not disposed to take any risk … while he could get a settlement through Congress he would lose a good number of tail feathers which he can ill afford to do … I do not believe that he cares about the actual money except so far as an increased offer [from the UK] could facilitate his handling of Congress’ (Self Reference Self2006, p. 187). Without a settlement, the UK made the last partial payment of $7,500,000 dollars on 15 December 1933.

The isolationist and protectionist temper of the US Congress reached its apex on 13 April 1934 with the Johnson Act, sponsored by Senator Hiram Johnson and signed by President Roosevelt (Dewitt Reference Dewitt1974). The Act prohibited the issue of loans or bonds in the US by those foreign governments that had defaulted on debts owed to the US government. It also prohibited the US President from accepting token payments on war debts in satisfaction of the original claim.Footnote 12

The Johnson Act was the tipping point in the UK decision not to make a token payment on the June 1934 deadline.Footnote 13 The official decision, taken on 4 June 1934, stressed that further payments on war debts were suspended until it became possible to discuss an ultimate settlement with a reasonable prospect of agreement (Shepardson and Scroggs Reference Shepardson and Scroggs1935, p. 72). Furthermore, the British position argued that war debts were fundamentally different from self-liquidating commercial debts raised for productive purposes. War debts had been neither productive nor self-liquidating for the debtor (Self Reference Self2006, pp. 119–20; Shepardson and Scroggs Reference Shepardson and Scroggs1935, pp. 77–8), whereas they had fostered growth in American industry. Virtually at the same time, the German Reich announced that after 30 June 1934 it would discontinue payments under the Dawes and Young loans (Toniolo Reference Toniolo2005, p. 154). In the certain knowledge that it would receive no further repayments from its own debtors, the UK finally agreed to suspend all debt payments (Self Reference Self2006, pp. 193–4). In the words of Foreign Secretary Sir John Simon:Footnote 14

The resumption of full payments … would recreate the conditions which existed prior to the world crisis and were in large measure responsible for it. Such a procedure would throw a bombshell into the European arena … and would postpone indefinitely the chances of world recovery. Accordingly His Majesty's Government are reluctantly compelled to take the only other course open to them.

Stronger language about the righteousness of the British default was expressed by Prime Minister Ramsey MacDonald: ‘we have to take upon ourselves the thankless task of putting an end to the folly of continuing to pay’ (Self Reference Self2007, p. 286).

France, the second largest debtor, had refused to meet its obligations earlier than the British decision. In fact, after having ratified a debt agreement with the United States in 1929, the French Chamber of Deputies repudiated the agreement a day before the 15 December 1932 payment deadline. The vote was overwhelmingly in favor of repudiation and called for an international conference aimed at a complete revision of all international payments (Florinsky Reference Florinsky1934, p. 344). A formal letter dated 15 December 1933 by the French ambassador to the United States De Laboulaye to the Acting Secretary of State confirms the legislative outcome; see the document in the Appendix.

The French and British defaults were not isolated cases; indeed, following the Johnson Act, all European debtors except one fell in default.Footnote 15 Table 1, from Reinhart and Trebesch (Reference Reinhart and Trebesch2014, p. 20), lists 18 countries that, as of 1934, owed debt to the US and the UK. Australia, New Zealand and Portugal only owed debt to the UK. Finland, which successfully renegotiated the terms of war debts and met payments in full, was the only country that honored its war debt obligations to the US. Lausanne, in brief, did not provide a resolution of the war debts. A series of unilateral decisions, occurring after Lausanne, led to a repudiation of US war debts. Next, we discuss in some detail how Italy arrived at its decision to default.

III

We revisit the Italian case because the literature does not offer a satisfactory account of the Italian default and an accurate reconstruction of foreign debt that is consistent with the underlying historical events.

Two significant dates for war debt restructuring were 14 November 1925 and 27 January 1926. On the first, the Italians reached an agreement with the Americans, and on the second they reached an agreement with the British. Both negotiations were conducted for Italy by Finance Minister Giuseppe Volpi. The US debt restructuring spread payments of the Italian debt over 62 years and reduced the undiscounted value of debt from $2,148 million to $2,042 million; see Table A3 in the Appendix. While the nominal values did not change materially, the present value of repayments did in a big way. The present value of the renegotiated debt, using a discount rate of 5 percent, was $360 million; see Section iv and Appendix. For the first five years, no interest was charged; then the interest rose gradually up to 2 percent for the final seven years (Volpi di Misurata Reference Volpi di Misurata1929, pp. 42–4; De Cecco Reference de Cecco1993, pp. 613–14). The British restructuring set the undiscounted sum of payments at £276.75 million, spread also over 62 years. The present value of repayments, using again a discount rate of 5 percent, was £84 million.Footnote 16

With the two debt agreements Italy obtained an average haircut of 84 percent. The country was treated particularly well in comparison to other countries that also reached foreign debt agreements with the US. For example, the UK received a haircut of 30 percent, Belgium of 50 percent, and France of 60 percent (Migone Reference Migone1980, pp. 72–3; Schmitz Reference Schmitz1988, p. 95). Debt renegotiations occurred at a time when US financial markets were overflowing with funds and the macroeconomic fundamentals justified capital outflows. Europe was a natural outlet for these outflows (Fratianni and Giri Reference Fratianni and Giri2017). The United States also sought a settlement to prevent the formation of an unwilling-to-pay bloc of former allies, and the debt settlement with Italy was the cornerstone of this policy (Schmitz Reference Schmitz1988, p. 85). Loans and investments were seen as the ideal mechanism for influencing domestic politics in Italy and elsewhere. As to the favorable treatment accorded to Italy, it should be noted that Mussolini was well regarded abroad as a leader who could ensure social stability, a condition that would have facilitated US economic expansion in Europe (Migone Reference Migone1980, pp. 72–3). Fascist nationalism appeared an attractive system to support: it was vehemently anti-Bolshevik, open to foreign trade and investment, and not threatened by any opposition from the left. On the other hand, American loans would work to prevent an Italian aggressive international policy and would help to maintain the status quo (Schmitz Reference Schmitz1988, pp. 96, 102).

The Washington agreement was based on the Italian capacity to pay. A delegation of Italian economists and statisticians, led by the well-known Corrado Gini, was sent to the US to argue the case that victory in World War I had left Italy ‘mutilated’ (Prévost Reference Prévost2015, p. 67). The assembled statistical documentation was convincing and had a material impact on the outcome of the negotiations with the Americans (Prévost and Beaud Reference Prévost, Beaud, Prévost and Beaud2012, p. 149).Footnote 17 In contrast, the British could not get the same deal as Italy because Britain was deemed to have a higher capacity to pay (Schmitz Reference Schmitz1988, p. 85).

The general climate for a return to the gold standard also helped the fortunes of Italy. Soon after the Washington agreement, J. P. Morgan lent the Italian government $100 million (Kingdom of Italy 7 percent), with the main objective of stabilizing the lira in the exchange markets.Footnote 18 It was one of the most important financial transactions on behalf of a foreign government made in the US market in 1925 (Asso Reference Asso1993, p. 240). After the debt agreement and the Morgan loan, American capital began to flow to Italy: from virtually zero in 1925 the cumulative capital inflow had grown by 1930 to over $460 million (Schmitz Reference Schmitz1988, pp. 96, 109).Footnote 19

The debt concessions of the 1920s were ‘sold’ to the US electorate as debt restructuring rather than debt forgiveness, even though one implied the other. In fact, US public opinion remained strongly opposed to forgiveness, a sentiment that led the US War Debts Commission to renegotiate debt agreements by lengthening the time horizon of the repayment of the capital sums and/or by reducing the rate of interest. The unsophisticated public would have noticed that the nominal value of the debt had remained unchanged, although the discounted present value of the renegotiated payments had been reduced.Footnote 20 Opposition to the agreement emerged quickly also in Congress: debt agreement was considered a US endorsement of fascism (Schmitz Reference Schmitz1988, p. 99), while the Washington and London agreements constituted undoubtedly a financial and political success for Italy. Together, these events provided Mussolini's government, which had recently been shaken by the murder of Matteotti and by the currency crisis, with a foreign policy success (Prévost and Beaud Reference Prévost, Beaud, Prévost and Beaud2012, p. 149). Volpi, on his return to Rome, was welcomed with great honors and celebrations (Romano Reference Romano1997, p. 141).

There is an important aspect of debt restructuring that was never officially recognized by the creditors, namely that the flow of German reparations to Italy played a critical role. Almost immediately after the US and UK agreements, the Cassa autonoma di ammortamento per i debiti di guerra (hereinafter, Cassa) was created with the purpose of using the proceeds from war reparations to repay war debts; it started operations in March 1926 as an autonomous administration outside the state budget. The Cassa received a start-up capital of 150 million lire in the fiscal year 1924–5. The Dawes Plan, which initially set the reparation receipts, lasted five years with relatively trouble-free reparation payments, but was unable to set the new amount of total reparations. These were fixed by the Young Plan and approved at the Hague Conferences of August 1929 and January 1930, according to which Germany would pay an undiscounted sum of 121 billion Reichsmarks, spread over 59 annuities; the value of each annuity was set ‘to match payments to the United States by Germany's creditors’ (Toniolo Reference Toniolo2005, p. 39). Reparation payments and transfer of funds would be handled by a newly created international organization, the Bank for International Settlements (Fratianni and Pattison Reference Fratianni and Pattison2001). The Young Plan reversed the design of the Dawes Plan and precipitated first a sudden capital stop in 1928 and then a capital flight and a debt crisis (Ritschl Reference Ritschl2012).Footnote 21 By 1929–30 Germany was in a recession, which later spread, through the constraints of the gold standard, to much of the world in the virulent form of a Great Depression (Eichengreen and Sachs Reference Eichengreen and Sachs1985; Temin Reference Temin1989; Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen1992; Fratianni and Giri Reference Fratianni and Giri2017). In the following year, 1931, President Hoover proposed the one-year moratorium.

At the Lausanne Conference of 1932, the Italian delegation, led by Foreign Minister Dino Grandi and Alberto Beneduce, stressed the principle that war reparations had to be linked to war debt payments.Footnote 22 The Italian position was that an extension of the Hoover Moratorium would not solve the fundamental problem of excessive war reparations. These had to be canceled and their cancellation had to be made conditional on the cancellation of war debts owed to the UK and the US.Footnote 23 Italian diplomacy had a two-stage strategy to achieve the twin cancellation. In the first stage, the European states would jointly ‘forgive’ Germany; in the second stage, they would seek debt forgiveness from the US. During the conference (and even after) there was no awareness by the Italian side that an agreement on reparations in Lausanne would have led to a permanent solution of the war debts problem, as it transpires from the diplomatic delegation.Footnote 24

After Lausanne, Italy made a token payment to the US of $1,000,020 in June 1933 against the full amount of $13,545,437 (US Treasury 1933, p. 28)Footnote 25 and $1 million in December 1933 (Ministero delle Finanze 1938, p. 86).Footnote 26 On 15 June 1934, after having considered a token payment of $1 million, Italy followed the UK example and paid nothing. That decision was contained in a letter by the Italian Ambassador, Augusto Rosso, to the Acting Secretary of State (see Appendix); the letter appeared also in the Italian press.Footnote 27 Three factors influenced the Italian decision. The first is that the government was worried that another payment would raise excessive expectations of future payments to the US. The second is the difficulty of ‘selling’ to Italian public opinion a payment on foreign debt when other countries had opted for not paying. The third is that an Italian payment would have created difficulties with the UK: British inability to pay the US stemmed from the failure of its own debtors, including Italy, to meet their obligations.Footnote 28

The bitter and complex matter of reparations and war debts was taking place while the open trade system in the 1930s fell victim to the fixed exchange rate and the consequent absence of monetary sovereignty (Eichengreen and Irwin Reference Eichengreen and Irwin2010). The deflationary bias of the gold exchange standard differed across countries. Those countries that remained on the standard the longest (members of the gold bloc) experienced the deepest economic depression. France was a leading member of the gold bloc; the level of its industrial production in 1935 was 28 percent below the level of 1929. In contrast, those countries that went off gold early did much better. In the UK, which went off gold in 1931, the level of industrial production in 1935 was 13 percent higher than the level in 1929 (Fratianni and Giri Reference Fratianni and Giri2017, pp. 13–14).

Trade restrictions, measured by tariff increases, positively correlated with the degree of the deflationary bias of the gold exchange standard (Eichengreen and Irwin Reference Eichengreen and Irwin2010, figure 1). The US played a big role in this process. After having been the largest foreign lender in the 1920s, the US first engineered a sudden capital-flow reversal in 1928 and then, two years later, passed the very protectionist Smoot-Hawley Act. The combination of a capital reversal and protectionism dealt a heavy blow to the open trade system. Foreign resentment to this shock took the form of retaliation and further implosion of trade relations. The World Economic Conference of 1933 in London fully reflected this uncooperative environment. The Roosevelt Administration managed to expunge the settlement of war debts from the Conference's agenda. Furthermore, the US decision to come off the gold standard in April 1933 sharpened the clash between fixed-exchange-rate countries and floaters. The French did not want to discuss protectionism and the British made the decision to give preferential trade treatment to the Commonwealth countries.

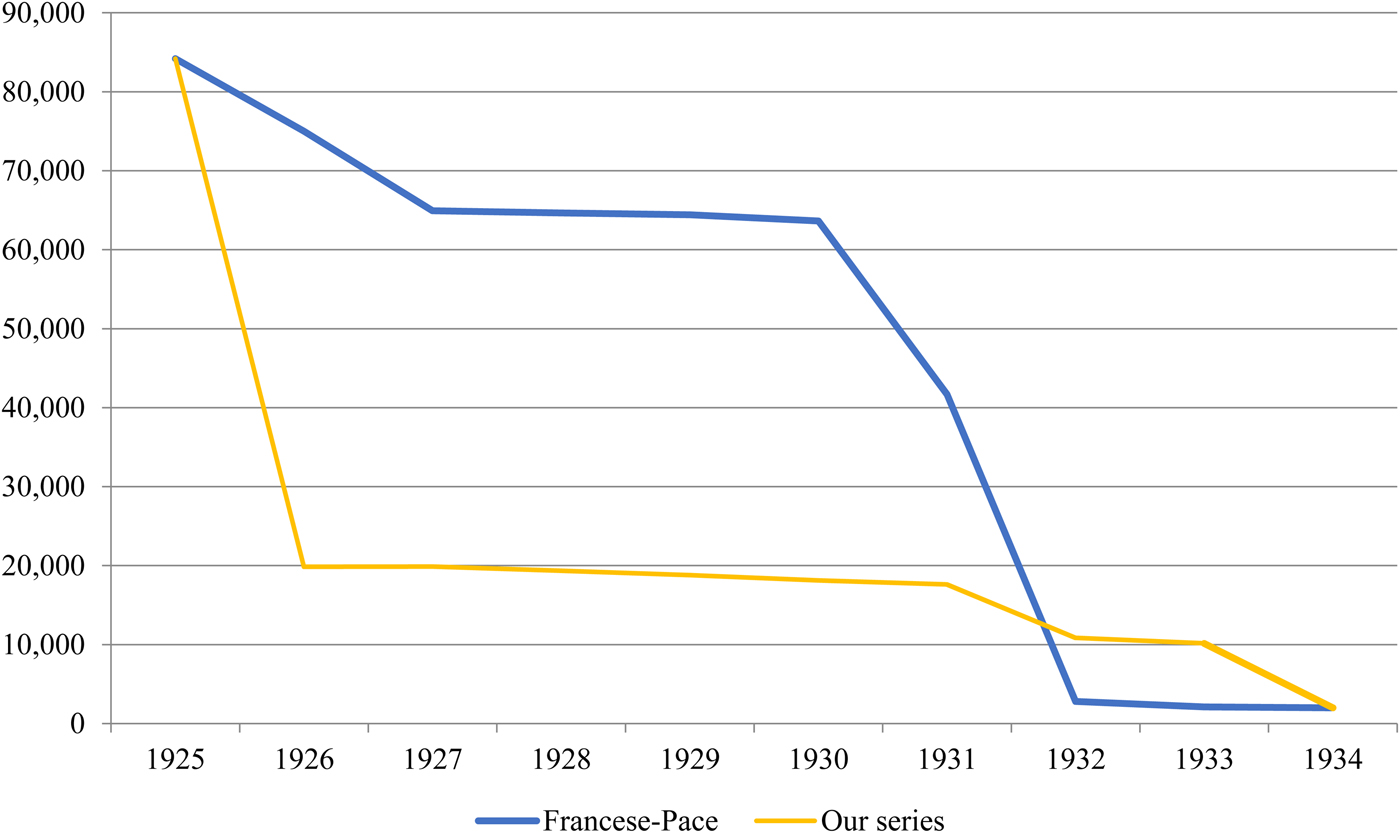

Figure 1. Foreign and total government debt as a percentage of GDP, 1919–39

The trade reorientation of the 1930s ran in parallel with a broad revision of the legislation on exchange controls affecting a vast number of nations (Eichengreen and Sachs Reference Eichengreen and Sachs1985, table 1). Italy introduced tighter currency controls in May 1934, and in December the Istituto Nazionale con l'estero was created to manage the exchange monopoly (Astore Reference Astore2014, p. 54). Controls on imports and on gold were soon implemented; the driving force underlying these measures was the depletion of official reserves between 1928 and 1934 (Banca d’Italia 1935, p. 12). The alternative of a devaluation was not contemplated because of the country's commitment to the gold bloc. The overvaluation of the Italian lira led to large purchases of Italian foreign debt, both public and private (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1987). After that, Italy defaulted on its war debt against the US. In sum, the economic environment in the 1930s was too unfavorable and embittered to facilitate the settlement of war debts.

In this scenario, Italy defaulted in December 1934. An attempt to renegotiate a settlement of Italian debt was tried in June 1936, but it was very feeble. Public opinion and the Congress in the US, as we have already indicated, remained quite hostile about forgiving or reducing war debts, despite the fact that a few proposals were discussed in the Congress to alleviate the burden on debtor countries.Footnote 29

In addition to war debts, Italy owed non-war debts to the US. In 1947, Italian ‘non-war’ debts of $136.3 million were rescheduled (Asso and De Cecco Reference Asso and de Cecco1994, table 14). Furthermore, from 1925 to 1933, loans for $370 million issued to Italian firms were placed mainly in the US market. Italy defaulted on these in 1941, but resumed debt service under the ‘Lombardo Plan’ that went into effect on 22 December 1947. The Lombardo Plan followed the diplomatic mission of Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi in the US in January 1947, a key turning point in post-war US–Italian relations (Mistry Reference Mistry2014, p. 48). The plan provided for the floating of new Italian Republic bonds (1 percent to 3 percent, 1947–77) replacing the ‘Republic of Italy’ loan that had consolidated all previous debt contracts, including the J. P. Morgan loan.

As to the settlement of German reparations, in June 1951 the Allied powers began negotiating a plan that arrived at a final agreement with the London Debt Agreement (LDA) of 1953, whereby half of German external debt was wiped out while for the other half there were generous repayment conditions based on export growth. The LDA was part of the wider European Recovery Programme, better known as the Marshall Plan (1948–51), which signaled the keen US interest in European reconstruction and in containing the spread of Communism (Galofré-Vilà et al. Reference Galofré-Vilà, Meissner, Mckee and Stuckler2018). The Marshall Plan mobilized a total of $13 billion from 1948 to 1951, aimed at rebuilding and stabilizing Europe's war-ravaged economies (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen2010). According to Kindleberger (Reference Kindleberger1989), the US was determined not to repeat after World War II the failed policies that followed World War I.

As to the British debt, Italy stopped payments after the Hoover Moratorium. Italian Foreign Minister Grandi reported that, in a private talk at the Lausanne conference, Prime Minister MacDonald gave his word of honor that the UK would have not required Italian payments on British debt so long as the Lausanne agreement was in force. But for the sake of political expediency the British could not make such an explicit statement.Footnote 30 The statement, however, was confirmed by MacDonald in December 1932, although not publicly.Footnote 31

At the start of 1933, there was virtual certainty in Italy, as well as in France, that no further payments would have been made to the UK.Footnote 32 The inference was that the UK, despite the fact that they had not formally agreed on debt forgiveness in Lausanne for political expediency, actually had reached a tacit agreement of forgiveness with its own debtors. It should be recalled that the UK was simultaneously a creditor and debtor nation, a position that justified focusing its diplomatic efforts on debt relief with the US. Had the UK pushed for the resumption of full payments with its own debtors, it might have strengthened a corresponding demand by the US. In conclusion, with respect to the UK, Italy benefited from a de facto debt suspension.

IV

In this section, we examine and compare two time series of Italian foreign debt: the series by F&P and our own. For an overview of the relevance of foreign debt (war debts being the biggest part of foreign debt), see Figure 1, which shows total government debt and its foreign debt component according to F&P (Reference Francese and Pace2008). These authors follow the methodology of the Maastricht Treaty on Government Deficit and Debt, and assign government debt statistics to the activity of the general government sector as defined in national accounts (Eurostat 2016). The general government sector is divided into four subsectors: central, state and local governments and social security funds (p. 11). The measurement of general government debt is defined in Section viii of the same document: ‘for a debt security, the nominal value is equal to the issue price … plus any interest that has accrued but has not yet been paid’ (p. 415).

Soon after the war, foreign debt exceeded 80 percent of Italian GDP and was approximately half of the total government debt. A significant reduction of foreign debt occurred in 1926, in concomitance with the two debt restructurings discussed above. Total debt, as a percentage of GDP, fell accordingly. By 1932, according to F&P, the ratio of foreign debt to total debt had fallen virtually to zero; see the first column of Table 2.

Table 2. Comparison of foreign debt series by Francese and Pace (Reference Francese and Pace2008) and our own, 1925–34, million lire

The F&P series draws from the Italian treasury's Conto riassuntivo del Tesoro (simply Conto). Italian documents make no distinction between domestic and foreign debt until 1923.Footnote 33 The distinction appears for the first time in the Conto of 1924, but the information is limited to a recitation of the nominal value of the debt; in addition, it is not clearly stated that values are expressed in gold lire. The Conto of 1925 offers more explanations, a point to which we will return below. Then, with the creation of the Cassa in March 1926, war debt accounting moved from the Conto to this autonomous administration.Footnote 34

We now present our estimates of Italian war debts. Critical in this reconstruction is the debt restructurings with the US of November 1925 and the UK of January 1926. In his report to Parliament, Finance Minister Volpi (Reference Volpi di Misurata1929, p. 48) stated that the two agreements reduced Italian foreign debt from 130 to 18 billion lire, the latter figure being the present value of future payments using a discount rate of 5 percent.Footnote 35 The resulting 84 percent ‘haircut’ on debt amounted to 64 percent of Italian GDP.

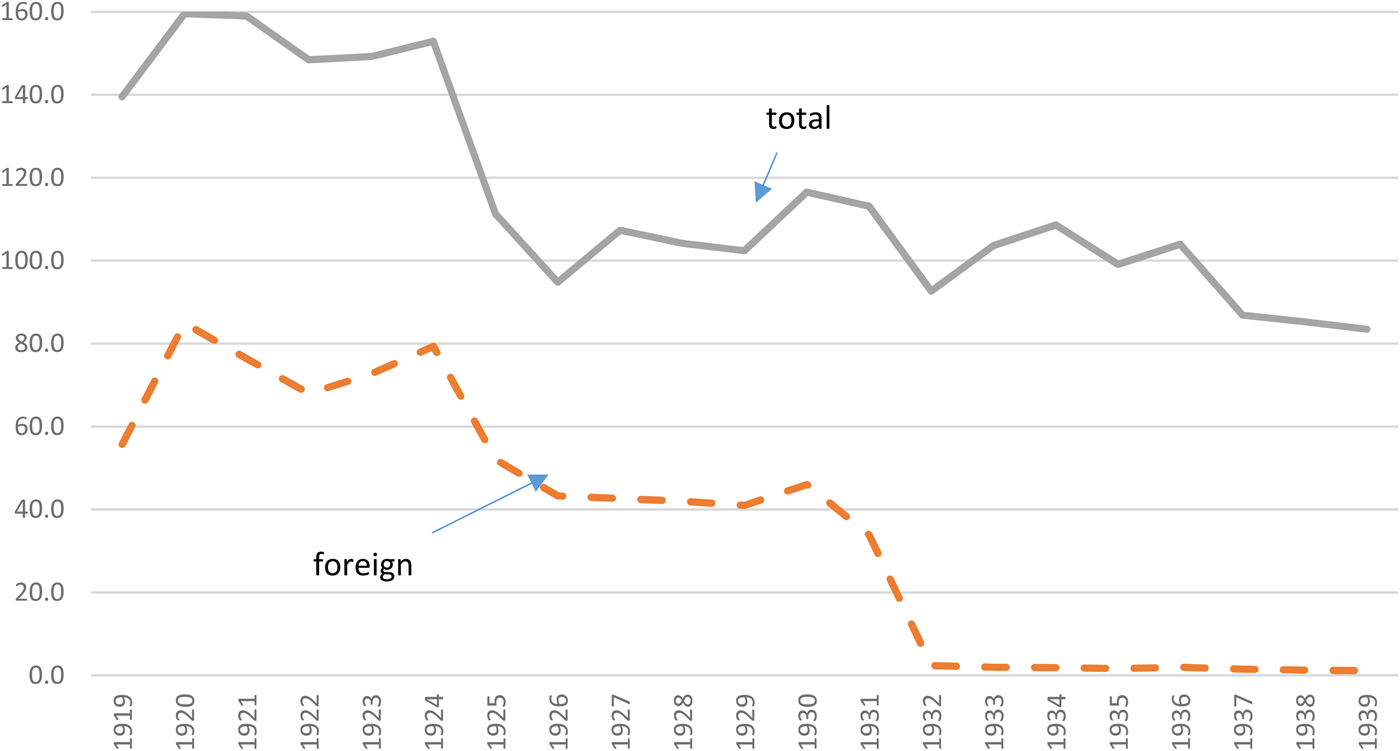

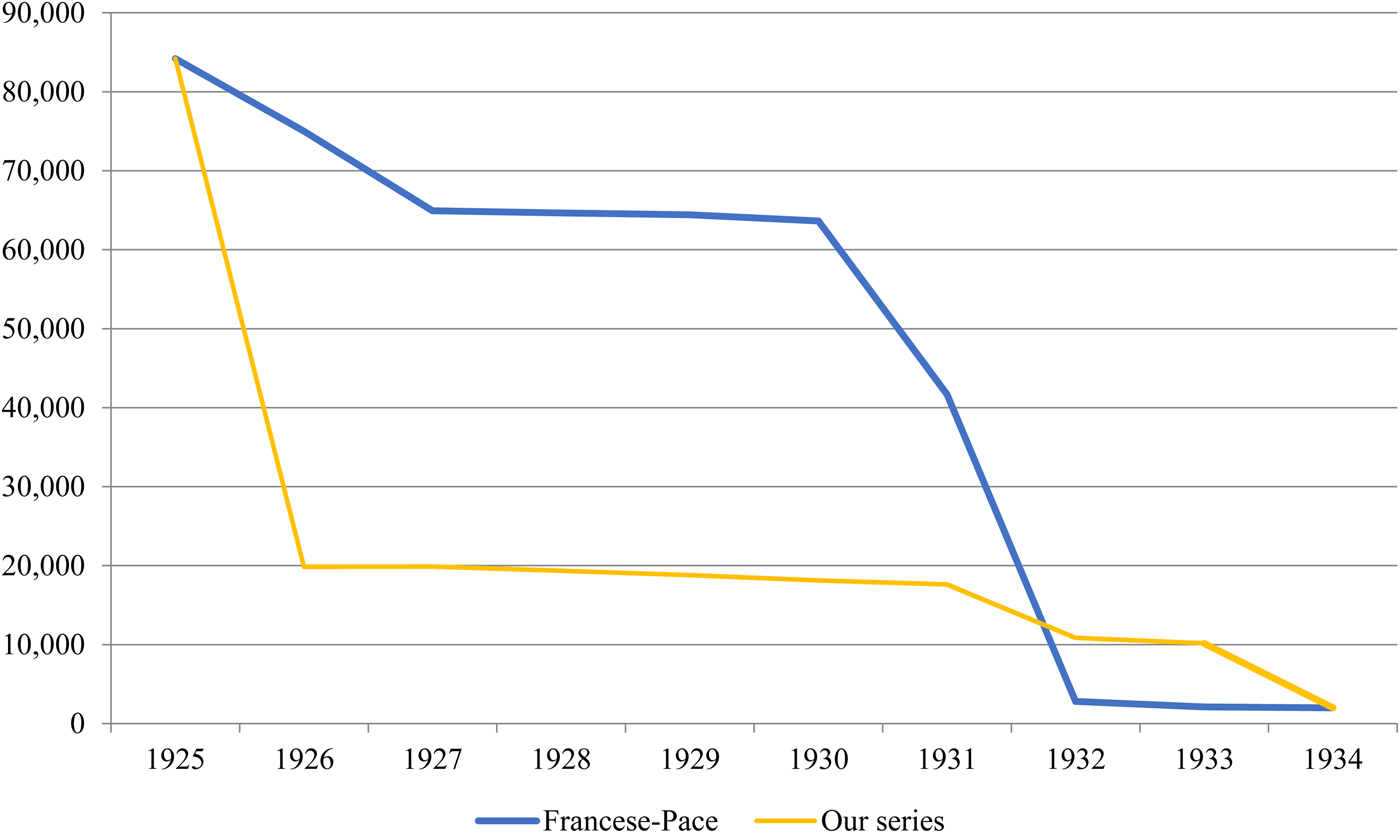

Table 2 and Figure 2 below compare our series with the F&P series. We start by using the same methodology and the same source as F&P (the Conto). Our data coincide with theirs in 1925. After 1925, our series differs substantially from theirs. Our reconstruction process starts in 1925, the year of the Washington agreement, for which the Conto (1926, pp. 14–15) reports the accounting of war debts as of 31 December 1925, plus the Morgan loan of $100 million.Footnote 36 Since the Washington agreement was concluded on 24 November 1925, the Conto of 1925 reports the net present value of debt resulting from the renegotiation. The debts are expressed in gold lire and are transformed in 1925 lire by multiplying the gold lire value by the ratio of the 31 December 1925 exchange rates to pre-war exchange rates. This yields a foreign debt for the year 1925 of lire 84,196 million (Table 2, last column). For consistency, in 1926, the year of the London agreement, we compute the UK foreign debt as the present value of the scheduled payments of the restructured debt. We then subtract from the present value capital repayments made in 1926 by Italy to the US and the UK. For subsequent years, the value of debt at time t is equal to the value of debt at time t-1 minus the payments made at time t. So, war debts owed to the US are reported from the beginning at their present value because they were restructured in 1925. For the UK, debt in 1925 is reported at its official value (the one recognized as the starting debt from the London agreement); starting in 1926, the value of the debt is the restructured one. In 1927, the cities of Milan and Rome contracted foreign loans for $30 million each (Asso Reference Asso1993, p. 340). In conformity with the Maastricht definition of public debt, we add the city-level foreign liabilities to our national series: we convert the $60 million dollars into lire from which we then subtract the repayment sums made by the cities.Footnote 37

Figure 2. The two series on Italian foreign debt, 1925–34, million lire

Significant differences emerge between our series and F&P's. Ours is much lower than F&P's from 1926 to 1931, but higher from 1932 to 1934. Two factors account for these differences. The first is quantitative in nature. In 1926, the F&P series shows a foreign debt value that is 55 billion lire higher than our series (Table 2). One reason for this large difference is that F&P have not properly taken into account the considerable haircut Finance Minister Volpi extracted in the London accord. The oversight, we surmise, could have occurred by following the accounting in the Conto. Having transferred in 1926 war debts to the Cassa, which falls outside the definition of the central government, the Conto reports from 1926 onwards only the value of the Morgan loan, while the Cassa reports the flow of reparation receipts and of war debt payments, without mentioning, however, the stock value of war debts. This incomplete reporting is rendered more opaque by the fact that no reference is made of the London 1926 restructuring agreement that reduces debt from £583 million to £84 million. In sum, by following the sources consulted by F&P – the Conto and the accounting of the Cassa that only shows debt payments – one may reasonably run the risk of overlooking the very large debt reduction achieved by Italy with the 1926 London agreement. The second difference stems from our historical reconstruction that shows 1934 as the year of the formal exit date of the US war debt, while 1932 is the exit date of the UK war debt. F&P, instead, use 1932 as the exit date for both US and UK war debts because they interpret, incorrectly, Lausanne as the final settlement of war reparations and war debts (F&P Reference Francese and Pace2008, p. 17).

V

Three essential points need to be stressed. First, Italy defaulted on its war debts. The Lausanne conference of mid 1932 did not put an end to inter-Allied war debts, as it is often interpreted in the literature. Apart from the fact that the US was not present in Lausanne, France repudiated US war debts on 14 December 1932, the UK suspended debt payments to the US on 15 June 1934, and Italy declared a de jure default on US debt in December 1934. All other debtor countries, with the exception of Finland, followed the example of the three largest debtor countries. Concerning the Italian debt owed to the UK, matters are less clear-cut because there was no formal default. Italy, together with other debtor countries, benefited from a de facto debt suspension, which can be reasonably dated to Lausanne. The new dating of French and Italian defaults and the known dating of British suspension of all debt payments do not diminish the importance of the Lausanne Conference in the long search for a settlement of war reparations and war debts. The evidence marshaled in our article simply suggests that the search for settlement must be stretched to include critical policy decisions taken after Lausanne.

Second, the strong antagonism to foreign debt forgiveness by the US public in the 1930s stands in sharp contrast with the significant concessions obtained by major debtor countries in the 1920s. Italy was treated particularly favorably in its debt agreements, obtaining a haircut of 82 percent from the US in 1925 and 86 percent from the UK in 1926. The concessions were ‘sold’ to the US electorate as debt restructuring and not debt forgiveness, even though one implies the other. Our account of the events suggests that the Americans granted Italy a very deep haircut because they recognized that the country had fallen into decline and did not have the capacity to repay. The US decision was facilitated by geopolitical considerations, namely that the Fascist regime was a solid bloc against the spread of Bolshevism.

Third, our account of relevant historical events has required a reconstruction of the Italian foreign debt series. Our series differs substantially from the F&P series (Reference Francese and Pace2008), the current standard in the literature. Differences are due primarily to the treatment of the 1926 UK debt restructuring. In addition, according to F&P, foreign debt, measured as a ratio of total debt, falls to zero because they interpreted the Lausanne conference as an act of debt forgiveness, which it was not. As to the UK debt, Italy defaulted de facto in June 1932. Our data reconstruction was complicated by the opaqueness of government accounting. Had we relied on the financial statements in the Conto Riassuntivo del Tesoro without the benefit of the historical reconstruction and new archival documents, we would have not succeeded in our effort.

APPENDIX

The Italian default of 1934

Text of the letter by Italian Ambassador, Augusto Rosso, to the US Acting Secretary of State, dated 14 June 1934:[1]

SIR:

With reference to your note of May 28th, containing a statement of the amount due from Italy under the provisions of the debt agreement of November 14th, 1925, and the moratorium agreement of June 3, 1932, my Government has instructed me to address to you the following communication:

‘By the token payments made on the 15th of June and on the 15th of December 1933 the Italian Government has shown its goodwill and at the same time, the limitations imposed upon it by the actual situation.

This situation, both in the economic and financial fields, not only has not improved since then but has become even worse. In fact, while tariff barriers and other hindrances to the exchange of goods, which is the chief source of international transfers, have further increased, there is practically no hope that Italy may be able again to collect those payments from German reparations which in 1925 have been taken as a basis for determining Italy's ability to put aside and transfer the amounts indicated by the debt agreement of November 14th, 1925.

The Italian Government, which has always been and is still willing to acknowledge its obligation in view of a final settlement, would have been prepared to reaffirm its goodwill by another token payment. It has been informed, however, that, under a law recently enacted, the nations which do not make full payment of the amounts due on the 15th of June will be considered as being in default.

In these circumstances and since, for the reasons mentioned above, the payment and transfer of the full amount due on the said date cannot be effected the Italian Government regrets to have to abandon the intention of making a token payment.

The Italian Government feels confident that, when the question might be reexamined by the two Governments, the very foundations of the settlement of November 1925 will, in the light of the new situation which has developed since then, help to bring about a satisfactory solution’.

I avail myself [etc.].

Rosso

The French default of 1933

Text of the letter by French Ambassador, De Laboulaye, to the Acting Secretary of State, dated 15 December 1933 (Foreign Relations of the United States, Diplomatic Papers, 1933, General, vol. i, document 722, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1933v01/d722):

[Translation]

Mr. Secretary of State: I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of November 28 last, and in reply to transmit herewith the following communication from my Government:

‘Inasmuch as no new factor has developed with respect to war debts since the resolution voted by the Chamber of Deputies on December 13, 1932, the French Government regrets that it is not in a position usefully to initiate a new debate on the question, and is obliged to postpone the payments due December 15 next.

Nevertheless, in order to remove any possibility of misunderstanding, it desires to recall the tenor of this resolution.

The French Chamber has never contemplated the unilateral violation of undertakings freely entered into, which would have been contrary to the invariable traditions of France. But it judged that the decisions which were taken on both sides in 1931 and 1932 in the hopes of facilitating the economic recovery of the world had modified conditions which formerly existed, and justify new arrangements which take into account the changes thus brought about.

The French Government cannot, of course, fail to recognize the difficulties which the achievement of such a new arrangement would involve. Nevertheless, it hopes that such difficulties may be overcome and that in the near future a solution to the problem of war debts acceptable to both countries may be anticipated.

For its part, it will consider it a duty not to neglect any of the possibilities which may arise in order to attain this end.’

The British default of 1934 (DBFP 195, document no. 594, p. 935)

Sir J. Simon to Sir L. Lindsay (Washington)

Foreign Office, May 30, 1934

In their note of November 6 last His Majesty's Government expressed their readiness to resume negotiations on the general questions whenever after consultation with the President it might appear that this could usefully be done. Unfortunately, recent events have shown that discussions on the whole questions with a view to a final settlement cannot a present usefully be renewed. In these circumstances His Majesty's government would have been quite prepared to make a further payment on June 15 next in acknowledgement of the debt and without prejudice to their right again to present the case for its readjustment, on the assumption that they would again have received the President's declaration that he would not consider them in default. They understand, however, that in consequence of recent legislation no such declaration would now be possible and if this is the case […]

‘His Majesty's government feel that they could not assume the responsibility of adopting a course which would revive the whole system of intergovernmental war debts payments. […] The resumption of full payments to the United States of America would necessitate a corresponding demand by His's Majesty government from their own war debtors. It would recreate the conditions which existed prior to the world crisis and were in large measure responsible for it. Such a procedure would throw a bombshell into the European arena which would have financial and economic repercussions over all the five continents and would postpone indefinitely the chances of world recovery. Accordingly, His Majesty's Government are reluctantly compelled to take the only other course open to them. But they wish to reiterate that while suspending further payments until it becomes possible to discuss the ultimate settlement of intergovernmental war debt with a reasonable prospect of agreement they no intention of repudiating their obligations and will be prepared to enter upon further discussion of the subject at any time when in the opinion of the President such discussion would be likely to produce results of value.

Table A1. War reparations received by Italy, 1919–33

Table A2. War debts paid by Italy, 1925–33

Table A3. Schedule of payments of the US and UK debts following restructuring

Table A4. Foreign debt in gold lire and current exchange rates at the end of 1925

Receipts from war reparations and payments for war debts