Following the conquest by the emperor Justinian's troops in the mid-6th c. CE, Carthago Spartaria (modern Cartagena) became, together with Malaca (Málaga) and Septem (Ceuta), one of the most important cities in Byzantine Hispania (Fig. 1).Footnote 1 The city appears to be a good candidate for the provincial capital (a question that the written accounts do not settle), due to its strategic position on the southeast coast of Spain, linked along maritime routes to other Byzantine strongholds and emporia in the western Mediterranean: Africa, the Balearic Islands, and Italy. In fact, Cartagena preserves the only Byzantine commemorative inscription found in Spain (CIL II 3420). It was part of the town's old rampart, which was restored in 589/90 CE by the magister militum Spaniae, Comentiolus: missus a Mauric(i)o Aug(usto) contra hostes barbaro[s] (“sent by the emperor Maurice against barbarian enemies”).Footnote 2 The emphatic tone in which the text was written has traditionally influenced the study of this period. Thus historiography has frequently been tempted to see Byzantine Carthago Spartaria as another of the reborn capitals of the Western provinces reconquered during the Renovatio Imperii.

Fig. 1. Cartagena and the Mediterranean after Justininan's conquests. (Map by J. Vizcaíno.)

Far away from the splendor of Ravenna or Carthage, Cartagena has instead revealed a different picture of Early Byzantine occupation in the western Mediterranean. Excavations since the 1980s have unearthed private dwellings and storehouses, as well as some pieces of Byzantine military equipment, such as lamellar armor.Footnote 3 The city has become a reference for the study of many aspects of material culture. Among them is the wide range of tableware, amphorae, and cooking wares found there, which highlight strong links with Byzantine Africa.Footnote 4

The cast bronze ewer studied in the following pages conveys new information about the nature and connectivity of Early Byzantine material culture in the western Mediterranean. It was recently excavated in a dump at Cerro del Molinete (Polybius's Arx Hasdrubalis: 10.10.7–11), one of the hills that surrounds the small peninsula where ancient Cartagena was founded. This article not only discusses the reconstruction of the trade networks outlined by bronze vessels around 600 CE but also provides a comprehensive view of the economic developments revealed by the production and circulation of these objects. A major aim is to show that cast bronze vessels can strongly contribute to an outline of the major economic transformations of the Roman world during Late Antiquity. The Cartagena ewer with its associated context is a key find in this respect. The paper is divided into three main parts: first, a discussion of the Late Antique city and the new find; second, the macroeconomic implications (e.g., long-distance trade); and third, the microeconomic and regional implications (e.g., consumption and use), bringing further categories of finds (e.g., thuribles, pottery, glassware) into the discussion. These three aspects are tightly interwoven and mutually complementary.

From Qart Hadast to Carthago Spartaria: the archaeological project Arx Hasdrubalis

As in other historical cities inhabited for a long time, one cannot understand the Byzantine occupation of Cartagena without mentioning its past and, in particular, the deep transformations to which its Carthaginian and Roman urban fabric was subjected. Cartagena was founded in 229/228 BCE by the Carthaginian general Hasdrubal, as a twin city of his motherland, Carthage. Protected by a deep bay, Qart Hadast (“new city” in Punic) became the capital of the Iberian territories controlled by the Carthaginians. It was conquered in 209 BCE by Scipio, becoming Carthago Nova, one of the most important cities of Hispania Citerior within the ancient conventus Carthaginiensis. Its natural harbor, oriented toward northern Africa and benefiting from a nearly impregnable defensive position, its famous lead and silver mines, and its location in a productive fishing area and in a part of Spain rich in esparto grass are all factors that explain this privileged position.

The town was founded on a small, well-protected peninsula – around 40 ha in size – surrounded by a belt of five hills of varying height and importance. Cerro del Molinete is one of them, and is located in the western sector of the site, between the harbor and an interior lagoon (Fig. 2a). The top of the hill and its southeastern slope are nowadays a protected archaeological domain, approximately 26,000 m2 in area (Fig. 2b).Footnote 5 The archaeological complex preserves a sequence that extends from the 3rd c. BCE to the 20th c. CE.Footnote 6

Fig. 2. Late Antique and Byzantine Cartagena: (a) general plan of the city; (b) detail of the archaeological area at Cerro del Molinete. (Archaeological project Arx Hasdrubalis.)

At the foot of the acropolis, the exposed Roman Forum district is a clear example of an exceptional process of urban and architectural refurbishment during the Cesarean–Augustan period.Footnote 7 The archaeological area includes four insulae built within a typical orthogonal street grid of cardines and decumani that ran at different heights. The so-called Insula I contained a bath complex, the “Harbor Baths,”Footnote 8 and a monumental building with banquet halls, the “Atrium Building.”Footnote 9 In Insula II, a sanctuary has been identified; judging from the archaeological and epigraphic evidence, it was dedicated to Isis and Serapis.Footnote 10 It is possible that the Atrium Building and the sanctuary – built jointly between the reigns of Nero and Vespasian – formed a single functional and religious unit managed by a collegium.Footnote 11

The Forum is adjacent to Insula IV to the east. The preserved archaeological evidence reveals the existence of a visual program aimed at honoring the imperial family and local patrons.Footnote 12 However, information about the Forum's architectural program is still incomplete.Footnote 13 In recent decades, archaeological fieldwork has been carried out mainly on the northern side of this monumental area, where the main temple of the city stands. It is located on the top terrace of the Forum, gradually leading from the foot of the hill to this civic square (Fig. 2b).Footnote 14 The temple was possibly built in Tiberian times, and could perhaps be identified as the sanctuary dedicated to the Deified Augustus, known from records on coins issued at the beginning of Tiberius's reign.Footnote 15 This monumental temple, however, was completely dismantled by the building of a Renaissance fortification and, centuries later, by the emergence of a populous suburb, inhabited until a few decades ago. Only the frontal wall of its lower platform, made of opus caementicium and lined with opus vittatum, has remained almost intact (Fig. 3a).Footnote 16 Archaeological excavations have exposed the preceding phases of the Roman temple: this zone was originally occupied by a Punic and Roman Republican quarter.Footnote 17 The Late Antique deposit examined in the present paper was recovered from a pit dug into a room belonging to this ancient quarter.

Fig. 3. Cartagena, Forum temple with the location of US 40516, shown at an earlier (a) and a later (b) phase of excavation. (Archaeological project Arx Hasdrubalis.)

If one takes into account both the collapse of the nearby curia or Collegium Augustalium and the abandonment and later reoccupation of the Roman Forum district,Footnote 18 it seems reasonable to infer that this temple was also affected by the same dynamics of obliteration on display from the 3rd c. CE onward.Footnote 19 In all likelihood, in Late Antiquity, the Forum temple was forced to adapt to the city's needs. In this respect, one must remember the laws of the 4th-c. Theodosian Code forbidding pagan sacrifices or the cult of idols (Cod. Theod. 16.10). The imperial administration tried to preserve these buildings as symbols of Roman identity, but most of them were eventually abandoned and reoccupied, and their building materials were used for other purposes.Footnote 20

Occupation of this building in Late Antiquity was perhaps similar to that of other temples of Carthago Nova. At Cerro del Molinete, none of the Roman temples appears to have preserved its original character beyond the 3rd c. CE. An eloquent example of the whole process is the Iseion, very close to this area. Following the 3rd-c. collapse, it was transformed during the 4th c. into an active manufacturing area.Footnote 21 The 6th and 7th c. accentuated these changes, since the remains of the Iseion became almost totally buried and barely visible beneath the new constructions.Footnote 22 A domestic and craft quarter developed on three terraces that concealed the last remains of the former sacred area. Some rooms made use of the old podium, and one of them (no. 50) was even built directly on top of it. The eastern corner of the old temenos was reused as a warehouse. Its abandonment layer contained an important pottery assemblage from the first half of the 7th c.Footnote 23

This Early Byzantine neighborhood was protected by a new wall at the top of the hill.Footnote 24 Inside the walled enclosure, the quarter had a street layout completely different from the ancient orthogonal grid. Despite a significant rise in the floor level, some of the old monumental building's substantial walls were still visible and were used as foundations for the construction of private dwellings or storehouses. A smithy was built over the old Atrium Building, which also included a motley domestic complex, the dumps of which can be dated to the first quarter of the 7th c.Footnote 25 Early Byzantine occupation was further marked by more complex urban interventions, such as a retaining wall made of reused blocks in opus africanum.Footnote 26

Due to the partial destruction of this sector in modern and contemporary times, one can only just hypothesize the Late Antique archaeological sequence at the Forum temple. The pit dug into its platform reflects presumed domestic occupation during the 6th and 7th c.; it seems to be similar to several deep pits or trenches recorded in the Byzantine neighborhood.

The 7th-c. pit

This pit, US 40516, was initially dug to access and extract architectural elements to be reused in new settlement structures in the vicinity, and it eventually became a dump connected to a nearby domestic assemblage. It was dug into Room 3A of a house of the Roman Republican period, sealed to build the main temple in the Forum (Fig. 3). This Republican phase (phase 3.1) has been dated to the 2nd c. BCE. The lowest part of the pit cut through the floor of this room, the exact plan of which remains unknown. Despite its small size, the pit contained an exceptional assemblage consisting of a bronze ewer, pottery (finewares, amphorae, and coarsewares), glass vessels, and animal bones (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Selected finds from US 40516. 1–2: Fulford coarseware closed form 4 / Bonifay commune type 62 jugs; 3: Fulford mortar Carthage class 1 / Bonifay commune type 11; 4: coarseware mortar; 5: Tunisian flanged bowl; 6: local coarseware bowl; 7: Werner A2 cast bronze ewer; 8–12: local cookware pots; 13–15: local cookware casseroles (CT 11, CT 12.1) and lid (CT 14); 16: local coarseware basin; 17–18: eastern Mediterranean amphorae; 19–20: regional/local amphorae. (Drawings by L. Suárez. Archaeological project Arx Hasdrubalis.)

Pottery is by far the most abundant category of find recorded in the pit. The only fineware is a sherd of African Red Slip Ware (ARS). Although the fragment did not have a preserved rim, we believe that the shape could be a flanged bowl of type Hayes 91, due to its low foot or flat base with feather-rouletting on the inside.

Notable among coarse North African pottery is a Fulford mortar Carthage class 1 / Bonifay commune type 11. These mortaria, usual in Early Byzantine contexts at Carthago Spartaria, are dated to ca. 575–675.Footnote 27 In addition, two jugs of common cream-surfaced Tunisian ware were recovered. They are one-handled jugs with a round rim, an apparently globular body and decoration of pronounced horizontal grooves and flat bottoms. They belong to Fulford coarseware closed form 4 / Bonifay commune type 62, dated to between the 5th and 7th c.Footnote 28 The range of Tunisian amphorae is restricted to spatheia Keay 26 G / Bonifay type 3; only one vessel preserved its characteristic elongated base. Due to the absence of any rim, a more exact classification is not possible. These small-sized containers are found in great abundance in Byzantine settlements in the late 6th–7th c.Footnote 29 At Carthago Spartaria, they manifest a close relationship with North Africa.Footnote 30

The supply of imported amphorae included eastern Mediterranean products. Unfortunately, only some non-diagnostic sherds were documented, and their classification is therefore hypothetical. We think that the containers belong mainly to Late Roman Amphora 1, one of the best-known Byzantine Levantine types of amphora. At Carthago Spartaria, LRA 1 is clearly the predominant eastern Mediterranean form.Footnote 31 Production sites of LRA 1 have been identified along the coasts of the provinces of Cilicia and Cyprus. The amphora type appeared in the 4th c. CE and was produced into the 7th c.; its content was principally wine, but it could also be filled with olive oil and even non-liquid goods.Footnote 32 Another sherd could belong to type LRA 2, a Byzantine globular amphora from the area of the Aegean.

The pit also included a regional/local amphora, the morphology of which is close to LRA 1. Although the associated pottery workshop has not yet been found, petrographic analyses support a local origin.Footnote 33 These containers show many inclusions of phyllites and quartzites, and the neck or shoulder was incised with a wavy-line decoration.

Finally for ceramics, the deposit contained a similar amount of coarse cooking ware manufactured in the area of Cartagena.Footnote 34 This local production was identified on the basis of both archaeological and archaeometric analyses, and through the examination of its textural aspect.Footnote 35 It is characterized by wheel-made wares using centripetal force and it presents many inclusions of local phyllites and quartzites. Throughout Late Antiquity, these local vessels were also strongly linked to the Balearic Islands.Footnote 36 Among the attested forms are pots (types CT 1.2, 3.2, 4.2, 4.3), large casseroles (types CT 11, 12.1), lids (type CT 14), and one sherd of a basin, of which only its handle and a fragment of its wall, displaying incised wavy-line decoration, were preserved. These local vessels were especially frequent during the 6th and 7th c., although some forms also occurred earlier.

As shown, ceramic vessels almost monopolize this assemblage. Other categories of finds are of great interest, however. For instance, a fragmentary glass vessel, with only its rim and neck preserved, has been recovered. The glass is dark green, translucent, and bubbly. Unfortunately, its precarious state of conservation prevented it being drawn. However, the rim permits its identification as a flask of type Dussart B X 3241–3242, which can be dated to the 6th or 7th c.Footnote 37

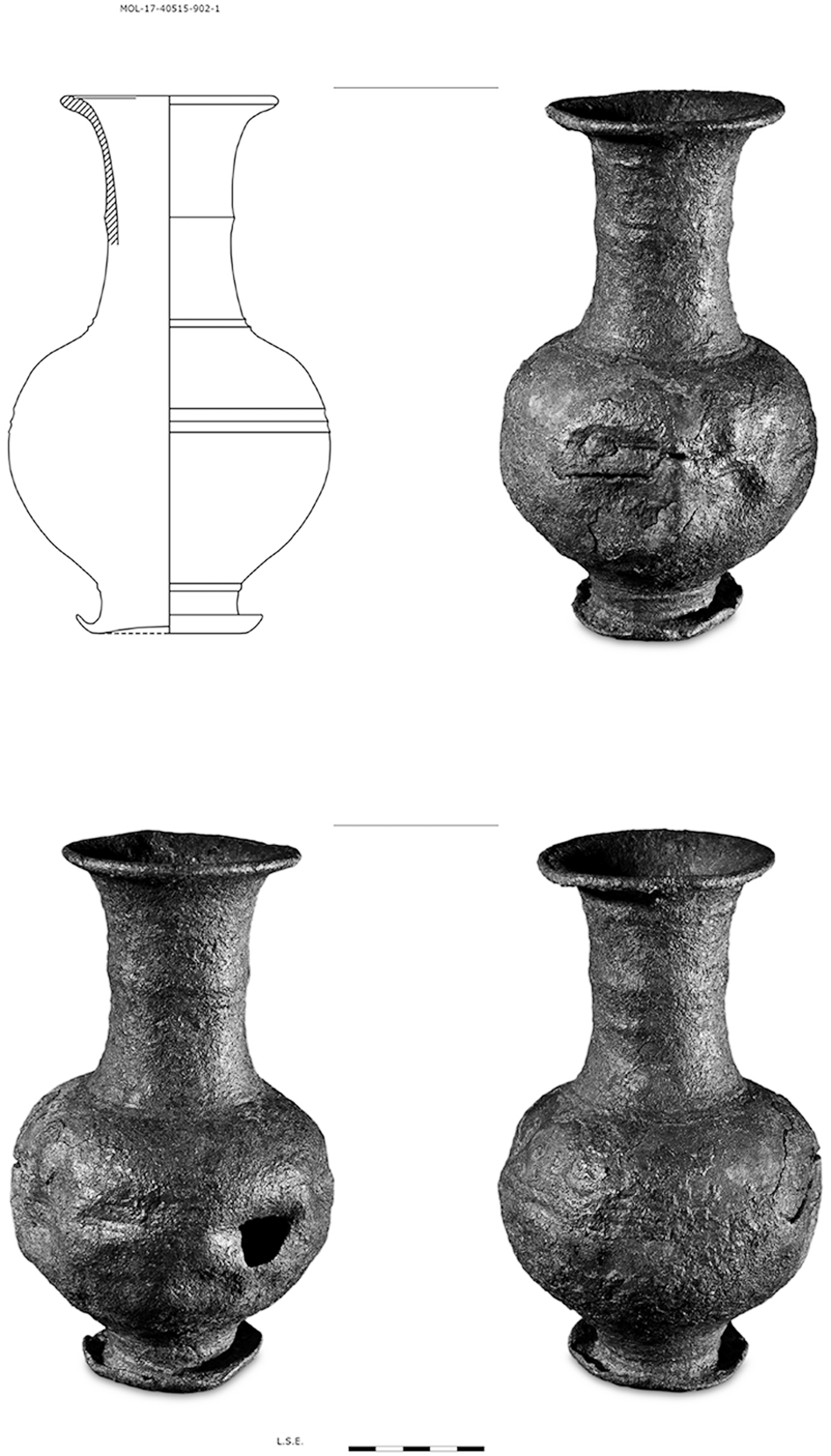

What appears to have been less common is the cast bronze ewer of type Werner A2 (Fig. 5), displaying a long neck and globular body; the missing handle may have been riveted to the ewer's neck and body. There are a dozen examples recorded in the Mediterranean region and central Europe. The most reliable contexts for dating, corresponding to burials containing combinations of several objects, suggest that the deposition of these ewers began around 600 CE and continued through the entire first third of the 7th c., although some examples can be dated to the decades immediately after (see the next section). The find from Cartagena is the only A2 ewer ever recorded in a stratigraphic context other than a grave. As noted above, the associated materials suggest a slightly later deposition than the time span 580/90–630/40 CE suggested by most of the grave finds.

Fig. 5. Bronze ewer from US 40516. (Photo by J. Martínez Conde. Drawings by L. Suárez. Archaeological project Arx Hasdrubalis.)

Last, one should mention the presence of animal bones. A preliminary analysis revealed the predominance of caprines and bovines killed in full adulthood.

The various categories of artifacts recorded inside US 40516 outline a quite coherent chronological framework, which corresponds to the 6th–7th c. The materials providing the narrowest time spans (spatheia Keay 26G, Fulford mortar Carthage class 1, and Werner A2 ewer) suggest a date between ca. 575 and ca. 675 CE. Generally speaking, typical local products from the second half of the 7th c. are absent from the pit: a deposition not later than 650 CE therefore appears plausible.Footnote 38 The event would thus have taken place at a time close to the destruction recorded by written sources (Suinthila's sack in 625 CE: Isid. Etym. 15.1.67–68); possible traces of this destruction horizon have been identified in the Byzantine quarter built over the Augustan theater.Footnote 39 Be that as it may, the filling of the pit might attest also to a possible continuity of occupation at the site beyond the alleged desolatio of the city after its capture by the Visigoth army.

Werner A2 ewers and their macroeconomic implications: production center(s) and distribution patterns

The composition of the assemblage at Cerro del Molinete ushers in the issue of trade networks connecting Cartagena with other Mediterranean territories. In addition to local and regional forms, the ceramic repertoire gives a clear indication of the commercial prevalence of African – mainly northern Tunisian – imports. The same can be said regarding the glass flask, which belongs to a form well attested in Carthage.Footnote 40 As for LRA amphorae, some authors have suggested that Eastern “exports” may have reached Cartagena indirectly, having been offloaded at and redistributed from Carthage.Footnote 41 It seems relevant that only Eastern amphorae and Late Roman unguentaria (LRU) from Asia Minor are recorded in the Early Byzantine contexts of Cartagena, whereas Eastern fine wares (Phocean Late Roman C or Cypriot Late Roman D) are quite scarce.Footnote 42

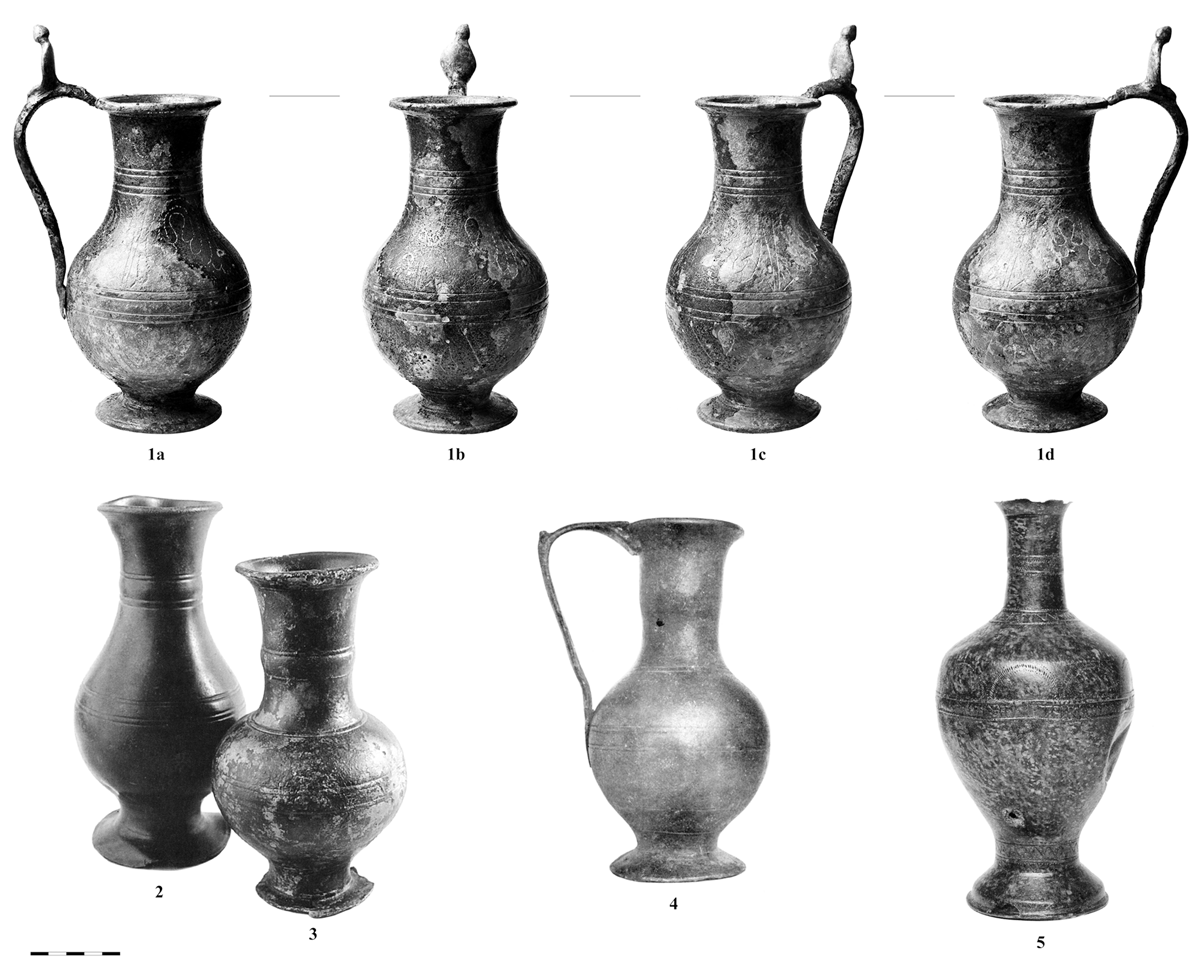

In this context, the bronze ewer appears to be an important piece of evidence related to mid- or long-distance trade connections. As the only example of an A2 ewer recorded in a stratigraphic context in the westernmost Mediterranean (from the Tyrrhenian coast to the Strait of Gibraltar), it is a precious sample of the period (early to mid-7th c. CE) and place (a relevant maritime trade center) in which this kind of object circulated. As a matter of fact, A2 ewers are a particularly problematic group of cast bronze ewers. Determining the location of the workshop(s) responsible for their production is no easy task, since no consistent candidate has yet been exposed in archaeological fieldwork, nor do the written sources elaborate on the matter. In addition, inferring the workshop's location from the geographical distribution of its products does not conclusively settle the issue in this case. On the one hand, A2 ewers appear to be one of the most heterogeneous types of early medieval cast bronze vessels, as regards both morphological and decorative features (Fig. 6).Footnote 43 On the other, they belong to a particularly problematic horizon when it comes to the production of cast bronze vessels, a sort of transitional period in which both Eastern and Western products were available in the western Mediterranean markets.Footnote 44

Fig. 6. Examples of A2 ewers. 1: Ittenheim; 2–3: Salona, unspecified findspot; 4: Spain, unspecified findspot; 5: Thierhaupten–Oberbaar. (1: courtesy of the Musée Archéologique de la Ville de Strasbourg; 2–3: after Marin Reference Marin1994, 309; 4: after Palol Reference de Palol1950a, pl. XIX; 5: after Daim Reference Daim2012, 368).

Central Italian finds form the most coherent group as regards both their chronology and their deposition: the ewers from Nocera Umbra and Montale were found in two female graves dating from ca. 590–610 CE.Footnote 45 Yet, in the upper Rhine valley, the use of such ewers seems to have lasted somewhat longer: the graves at Ittenheim–Neuziel Straße and Pfahlheim–“Brühl” were two male burials, the chronology of which stretches from the late 6th/early 7th c. (Ittenheim) to the mid-7th c. (Pfahlheim).Footnote 46 The ewer from Thierhaupten–Oberbaar appears to have been deposited somewhat later, since it was a surface find retrieved in a funerary area dating from the last third of the 7th c. or the beginning of the 8th c.Footnote 47 Another related ewer was found further east, in Avarian Pannonia: the grave at Budakalász contained a female burial dating from the second third of the 7th c.Footnote 48

As mentioned above, the main regional clusters of A2 ewers (Fig. 7) are observed in the upper Adriatic (four examples) and southwest Germany and Alsace (another four examples). The diachronic trends of their distribution show that the earliest depositions are located in northern central Italy (Montale and Nocera Umbra) and the Rhine valley (Ittenheim). In southwestern Germany, the chronology of the deposits follows a clear pattern: the further from the Rhine valley the deposit is, the later its date. One can thus follow in a quite orderly manner a route going from west to east, outlined by the consecutive Ittenheim, Pfahlheim, and Oberbaar burials.

Fig. 7. Distribution map of selected cast bronze vessels and related artifacts, ca. 525–625 CE. The lists of finds can be consulted in Beghelli and Pinar Reference Beghelli and Gil2019a and Reference Beghelli and Gil2019b. ![]() Prepotto type;

Prepotto type; ![]() Werner A2 type, forerunner;

Werner A2 type, forerunner; ![]() Werner A2 type;

Werner A2 type; ![]() Spilamberto type;

Spilamberto type; ![]() Volubilis type;

Volubilis type; ![]() Werner A1 type;

Werner A1 type; ![]() Evison IV type with arched decoration. Uncertain provenances are represented by empty icons with a dot. (Map by J. Pinar. Images after Arena et al. Reference Arena, Delogu, Paroli, Ricci, Saguì and Vendittelli2001, 422; Vida Reference Vida2006, fig. 2; Ahumada Reference Ahumada Silva2010, pl. 129; Palol and Pladevall Reference de Palol and Pladevall1999, 319; Roffia Reference Roffia and Breda2010, 72.)

Evison IV type with arched decoration. Uncertain provenances are represented by empty icons with a dot. (Map by J. Pinar. Images after Arena et al. Reference Arena, Delogu, Paroli, Ricci, Saguì and Vendittelli2001, 422; Vida Reference Vida2006, fig. 2; Ahumada Reference Ahumada Silva2010, pl. 129; Palol and Pladevall Reference de Palol and Pladevall1999, 319; Roffia Reference Roffia and Breda2010, 72.)

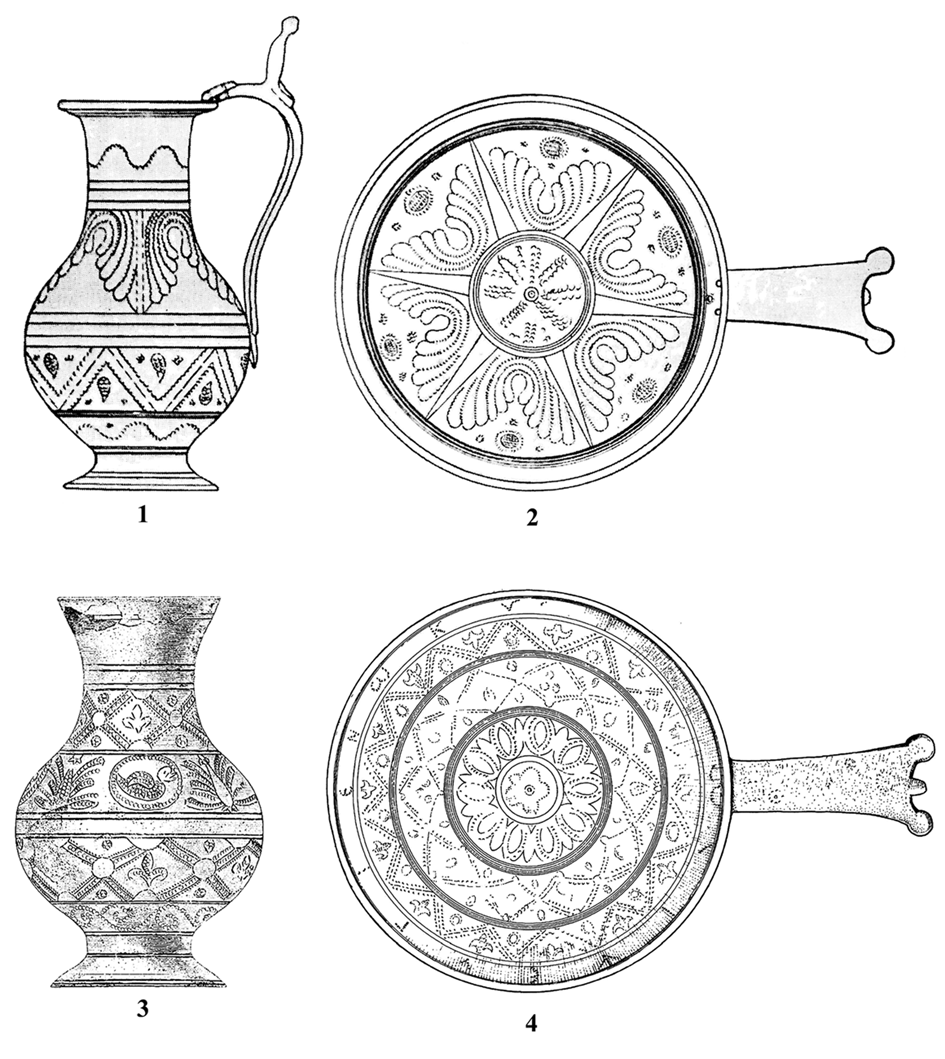

The fact that this pattern of distribution is not a random result of the current state of research is confirmed by its close correlation with the spread of similar objects belonging to the same period. This is the case of Werner's A1 pans and Spilamberto ewers.Footnote 49 The latter are found in northeastern Italy and the lower Rhine valley, whereas A1 pans cluster in northeastern Italy, the Rhine valley, and southwestern Germany (Fig. 8). Much like the A2 ewers, the A1 pans (about 600 CE) were first deposited either in northeastern Italy (Cividale–San Mauro) or close to the Rhine (Ittenheim and Güttingen);Footnote 50 further east, they were buried as grave goods around the mid-7th c. (probably a local variant, attested at Wittislingen).Footnote 51 The fact that at least some of the A1 and A2 vessels are to be connected to the same production center(s) is further confirmed by the closely related decorations of the items found at Ittenheim (a drinking set consisting of ewer and pan), on the one hand, and at Montale, Bonn, Pfahlheim, and Cividale–San Mauro, on the other (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8. Examples of decorated vessels of Werner A1 and A2 types. Not to scale. 1–2: Ittenheim; 3: Bonn, unspecified findspot; 4: Cividale–San Mauro, gr. 21. (1–3 are after Werner Reference Werner and Crome1938, pls. 27–28; 4 is after Ahumada Reference Ahumada Silva2010, pl. 12.)

Fig. 9. Distribution of cast bronze vessels in the Spanish Levant, ca. 500–700 CE. The lists of finds can be consulted in Beghelli and Pinar Reference Beghelli and Gil2019a and Reference Beghelli and Gil2019b. ![]() Prepotto type;

Prepotto type; ![]() Werner A2 type;

Werner A2 type; ![]() Grammichele type;

Grammichele type; ![]() Pupput type;

Pupput type; ![]() cast trulla?;

cast trulla?; ![]() Werner B3 type;

Werner B3 type; ![]() Mañaria type;

Mañaria type; ![]() Volubilis type;

Volubilis type; ![]() Las Pesqueras type;

Las Pesqueras type; ![]() Werner B2 type. (Map by J. Pinar. Images after Arena et al. Reference Arena, Delogu, Paroli, Ricci, Saguì and Vendittelli2001, 422; Palol Reference de Palol1950b, pls. I and IV; Emery Reference Emery1938, pl. 82; Palol and Pladevall Reference de Palol and Pladevall1999, 310 and 319; Arbeiter and Noack-Haley Reference Arbeiter and Noack-Haley1999, pl. 6; Wamser and Zahlhaas Reference Wamser and Zahlhaas1998, 58.)

Werner B2 type. (Map by J. Pinar. Images after Arena et al. Reference Arena, Delogu, Paroli, Ricci, Saguì and Vendittelli2001, 422; Palol Reference de Palol1950b, pls. I and IV; Emery Reference Emery1938, pl. 82; Palol and Pladevall Reference de Palol and Pladevall1999, 310 and 319; Arbeiter and Noack-Haley Reference Arbeiter and Noack-Haley1999, pl. 6; Wamser and Zahlhaas Reference Wamser and Zahlhaas1998, 58.)

The dissemination of the earliest documented examples shows a major clustering in the territories neighboring Byzantine dominions in the northern Adriatic (Cividale, Reggio Emilia, Montale, Nocera Umbra). Spilamberto ewers, attested in about 600 CE at Cividale and Spilamberto, exactly mirror the same pattern;Footnote 52 the comparable locations of Spilamberto and Nocera Umbra in two Byzantine–Lombard borderlands are eloquent cases. There is little doubt that the upper Adriatic coast was the gateway of these vessels into central Europe. It is likely that from this area, probably after following the Po Valley westward, they reached the upper Rhine through western Alpine passes, as Joachim Werner suggested.Footnote 53 From there, the vessels would have spread during subsequent decades throughout southern Germany. Judging from the chronology of the depositions, they were kept for a long time before being buried, or they changed ownership a few times.

The geographical distribution of the A2 and Spilamberto ewers clearly suggests that the northern Adriatic was their area of production.Footnote 54 While Spilamberto ewers are completely absent east of the Adriatic, the unusual examples of A2 forms recorded in the East display particular details suggesting that they were not produced in the same workshops as those discovered in Europe.Footnote 55 The three-footed base of a ewer found at Amathus in Cyprus illustrates this observation quite well.Footnote 56 Many scholars are instead inclined to attribute a Levantine/Egyptian origin to all these objects, in the light of the eastern Mediterranean parallels of A1 pans and the frequent presence of Greek inscriptions on them.Footnote 57

The “Eastern connection” of these pans, however, may be weaker than it seems. Only two of the alleged Eastern A1 pans are related to precise geographical areas (Egypt and Israel),Footnote 58 whereas the provenance of the examples preserved at Washington and Oxford is completely unknown.Footnote 59 In addition, the Egyptian and Levantine pans show particular morphological features not attested in any of the western find spots: a beaded rim, a zoomorphic handle ending, and a foot with nodus.Footnote 60 In such a context, the presence of Greek inscriptions is probably not reason enough to attribute the whole type to an eastern Mediterranean production center. Instead, the dissemination of closely related inscriptions from Cividale–San Mauro (Fig. 8: 4) and Reggio EmiliaFootnote 61 fits well with a northern Adriatic workshop, perhaps based in a Greek-speaking environment; the largely bilingual metropolis of Ravenna of the late 6th c. may be one of the likeliest locations.Footnote 62 This was also the most probable production center for A2 and Spilamberto ewers: the Latin inscription on the A2 ewer from Thierhaupten–Oberbaar (Fig. 6: 5) supports our hypothesis of a bilingual milieu of origin.

As for the ewer from Cerro del Molinete, its best parallels, displaying similar forms and decorations formed by pairs of parallel grooves (Fig. 6: 3–4), have been identified at unspecified spots in Salona and elsewhere in Spain.Footnote 63 This fact renders likely the Adriatic origin of the Spanish finds and contributes to the definition of a circulation axis going from east to west. In particular, the finds in Cartagena and Salona outline a likely seaborne distribution, linking the Spanish Levant with the production center(s) in the northern Adriatic. As for the richly decorated examples of A1 and A2 vessels, they best outline the south–north route connecting the Po valley with the Rhineland. Some undecorated vessels were also discovered along this axis, as clearly shown by the ewers from Spilamberto, Wijchen, and Welsrijp.

The Mediterranean route is foreshadowed by some earlier finds of bronze cast vessels (Fig. 7). For example, the “western” Prepotto ewers show a very similar distribution pattern that includes Prepotto on the northern Adriatic coastline, Rome, and Tarragona.Footnote 64 This supports the hypothesis of a seaborne circulation of cast bronze vessels between the northern Adriatic and the Spanish Levant. The only example from a proper stratigraphic context is from a grave located in the cloister of Tarragona cathedral, dug after 590/600 CE.Footnote 65 It thus seems likely that the western European variant of these ewers was circulating during the mid- and late 6th c., if not earlier. A similar chronology can be attributed, on a morphological basis, to two cast ewers in the Vatican and Bardo museums, which can be interpreted as precursors of Spilamberto and A2 ewers.Footnote 66 Although data on provenance is lacking, it seems likely that they were found in Italy and Tunisia, hence outlining a distribution pattern quite similar to both the “western” Prepotto and A2 ewers. The 6th-c. assemblage of bronze implements recorded at Pupput in northern Tunisia, reflecting close relations with Italy and the Mediterranean Levant, fits into this pattern well.Footnote 67

The distribution of early cast bronze vessels in North Africa and easternmost Spain thus paints a picture compatible with evidence for other categories of imports (e.g., pottery and glassware) recorded at Cartagena, suggesting that Carthage functioned as a redistributive center for Tunisian, eastern Mediterranean, and central Mediterranean manufactured goods reaching the Spanish Levant. A glass drinking horn retrieved in the Byzantine layers of Cartagena's Augustan theater seems to testify to the existence of this same route,Footnote 68 although, to the best of our knowledge, this type of object has not been recorded so far in North Africa. The object belongs to type Evison IV, a variant with decoration in the shape of an arch;Footnote 69 it is an item widely interpreted as an Italian product. This type of horn belongs to the same cultural sphere and chronological period (late 6th‒early 7th c.) as the ewer from Cerro del Molinete. Only one similar drinking horn is known in Spain: it was found in Segobriga, another Roman city located in the southeast that was ancestrally linked with Cartagena. Although only the horn's base is preserved, it can be attributed to Italian workshops on the basis of a few morphological features and decorative motifs.Footnote 70

Evison IV drinking horns show the same dissemination pattern (northern Adriatic, Po valley, Rome, and southeastern Spain)Footnote 71 as A2, Spilamberto, and western Prepotto ewers (Fig. 7). The distribution and use of these specific types of horns and ewers appear to be mutually interwoven: they occur together not only at several locations and archaeological sites but even in the same deposits (for instance, the aforementioned Nocera Umbra gr. 17 and also Spilamberto gr. 62Footnote 72), as components of drinking sets that are somewhat heterogeneous. It seems very likely, therefore, that both the A2 ewer and the drinking horn found in Cartagena traveled west from Italy, probably via Carthage: the tight commercial links between Adriatic Italy and Carthage in the 6th–7th c. are clearly mirrored by the pottery contexts recorded at Classe.Footnote 73

The occurrence of cast bronze ewers between the mid-6th and early 7th c. is proof indeed of a tight correlation with Byzantine trading places in the western Mediterranean: Salona, Rome, Cartagena, and, possibly, Carthage, are all eloquent examples. When considering that the production center of at least some of these vessels was located in the northern Adriatic, it seems fair to label them “Byzantine,” but one needs to bear in mind that they were explicitly “Western Byzantine”: they were produced and distributed exclusively in the West. Some regional differences in their patterns of use suggest, though, that the frequency of their circulation was not uniform throughout the whole Western network. Much as in the territories of southern Germany, which were not primarily connected to the commercial route following the Rhine northward, the data from Late Antique levels in Tarragona and perhaps also in Cartagena (if one agrees with a date of deposition close to the mid-7th c.) suggest that in Spain these objects were used for quite long periods of time before being deposited or dumped. That might mirror the peripheral situation of the westernmost Mediterranean with regard to the trade in bronze cast vessels around 600 CE, as indeed is suggested by the scarcity of finds from that time. In addition to the three examples recorded in Spain, only one ewer has been found in North Africa, and no examples have been spotted so far in the western Mediterranean islands or in the coastal regions of southern France.

Cast bronze vessels in the Iberian peninsula: microeconomic and regional implications

With 20 cast vessels belonging to 10 different types attested between the late 5th and the early 8th c. CE (Fig. 9), eastern Spain provides a consistent sample of the overall tendencies in the evolution of the production, distribution, and consumption of cast bronze vessels. This is unparalleled in the rest of Europe and the western Mediterranean; no other region shows comparable concentrations of finds, varied typological repertoires, and long-term chronological sequences. In this context, the new discovery at Cerro del Molinete has helped clarify the general picture: the trade networks supplying the Spanish Levant with imported items and the pace of their diffusion can be now outlined in a more precise way. The earliest cast bronze ewers were introduced as a result of long-distance seaborne trade, with, in the case of Spain, ships leaving peninsular Italy and traveling first to Carthage, the last stopover on this commercial route. Apparently, the arrival of these “exotic” objects in the 6th and early 7th c. laid the foundations for the emergence of local productions, as suggested by the new typological repertoire, attested as early as the mid-7th c. This tendency grew stronger during the late 7th and 8th c., since strictly regional products became dominant throughout the Iberian peninsula, and evidence for interregional contacts (Italy and, perhaps, Gaul) decreased significantly.Footnote 74

In easternmost Spain, the evolution of these economic trends can easily be followed by looking at the map, on the basis of the diachronic distribution of the different types of cast bronze vessels (Fig. 9). The early imports from Italy (“western” Prepotto and Werner A2 ewers, Grammichele and Volubilis thuribles) and from the eastern Mediterranean (Pupput thuribles, trullae) are recorded almost exclusively along the coastline. In both cases, available evidence suggests that they may have reached Spain from Carthage.Footnote 75 On Iberian soil, they occur in both the Byzantine and Visigothic areas of influence. As already mentioned, it is plausible that the arrival of cast vessels in Spain at first followed the network of Byzantine trading outposts. From there, they spread into the surrounding territories, regardless of the geopolitical situation; a similar phenomenon was identified in Italy, where A2 vessels occurred in the “Lombardic” territories surrounding Byzantine emporia, seaborne routes, and strongholds (in Friuli, Emilia, Umbria).

It is probably no coincidence that the first vessels connected to Spanish local productions (e.g., “tripartite” variants of Werner B3 ewers) are mainly clustered in and around the earliest areas where imports are found, namely Murcia (Mula), the Balearic Islands (Son Peretó), and Catalonia (La Grassa, El Bovalar, Collet de Sant Antoni).Footnote 76 In our view, the workshop(s) producing these vessels were probably located somewhere in the Spanish Levant. There is no clear evidence that these workshops were still active after 650 CE. From that time on, ewers derived from the B3 form (type Mañaria), are clustered further west, in central and northern Spain. In all likelihood, their production center(s) were located in that area, and they held a much weaker connection with the Mediterranean trade networks. This tendency is further strengthened over time, as suggested by the distribution of late 7th-c. and 8th-c. cast bronze ewers (Las Pesqueras and Morbello types), also a product of central or northern Spanish workshops.Footnote 77

The evolution of long-distance trade networks can be framed even more precisely by examining a handful of thuribles discovered in the Spanish Levant (Fig. 9). The items from El Bovalar and an as yet undetermined spot in the Almería province belong to the Volubilis type, known exclusively in the western Mediterranean.Footnote 78 The dating contexts suggest that they were in use during the 8th c.Footnote 79 Since their distribution pattern largely coincides with that of “western” Prepotto and A2 ewers (Fig. 7), it is, however, plausible that they arrived in Spain much earlier, around 600 CE. A Grammichele type thurible found at Aubenya in Majorca may also be related to the trade routes bringing Italian cast vessels to the Spanish Levant in the late 6th and early 7th c., as it was probably produced in Sicily.Footnote 80

The picture prior to 600 CE, on the other hand, may be manifested by Pupput type thuribles, recorded both in Catalonia (Lladó) and the province of Almería. Unlike the Volubilis type specimens, they have many parallels in Egypt, the Levant, and the Aegean, and can safely be considered as imported goods from the eastern Mediterranean.Footnote 81 The composition of the already mentioned assemblage from Pupput, where one such thurible was associated with a 6th-c. cast bronze ewer, suggests that the Eastern objects may be from a period older than their Western counterparts.Footnote 82 The available data thus suggest that eastern Mediterranean vessels vanished from Spanish ports before the end of the 6th c., whereas Italian imports may have been still available until the first decades of the 7th c. The commercial flow bringing this category of Eastern metalwork to Spain is also illustrated by finds from the Favàritx shipwreck in Minorca:Footnote 83 its cargo contained a consistent assemblage of bronze liturgical implements, including the likely fragments of a trulla, with parallels from late 5th-c. and early 6th-c. Egypt.Footnote 84

Thus, the evolution of the production and distribution of cast bronze vessels in the Iberian peninsula faithfully mirrors the overall Mediterranean trend:Footnote 85 long-distance chains of supply gradually contracted throughout the late 6th c. and the 7th c., and this decline was partially mitigated by the rise of middle- and short-distance networks linking the productions of several local workshops. A singular phenomenon can nevertheless be observed in Spain: at the beginning of the sequence, the Iberian peninsula appears to have been an importer of Italian/Adriatic and even “Eastern” vessels, whereas at its end, it is proven to be an exporter to westernmost Italy. The number of cases, however, is too limited to permit inferring any quantitative economic data. Throughout the 6th–8th c. CE, however, the mapping of the find spots suggests that the mid- and long-distance distribution of cast bronze vessels followed maritime trade routes.

Another important aspect put forward by the ewer from Cerro del Molinete concerns the patterns of use of this kind of object. The deposits at Cartagena and Tarragona suggest that imported ewers were still in use at least 40–50 years after their presumable time of production. A similar phenomenon has been recorded in central Europe (Pfahlheim in Germany, Budakalász in Hungary), in findspots located far from the main trade axis (see the preceding section). These examples suggest that there might have been an inverse correlation between the availability of bronze ewers in the local markets and the average length of their use, and hence they support our previous observations on the limited circulation of cast bronze vessels west of the Italian islands. However, intrinsic production costs of the objects may also have played a role in the length of their useful life: for instance, the standard lifetime of the lavishly decorated thuribles with openwork lids of Volubilis type may have been longer than that of the ewers, as is suggested by the examples from Bovalar (associated with a mid-7th-c. ewer) and Morbello (associated with an 8th-c. one).Footnote 86

The pit recorded at Cerro del Molinete brings forward one last aspect of cast bronze vessels: the recurring problem of determining their original function. The Iberian peninsula is one of the Mediterranean regions with the most evidence for the liturgical use of cast bronze vessels: almost every recorded type shows at least one clear connection to Christian liturgy. The B3 and Las Pesqueras ewers have thus been recorded as part of the liturgical furnishings of churches of Late Antiquity;Footnote 87 both types have also been recognized in assemblages with very similar compositions, which can therefore be acknowledged as liturgical sets.Footnote 88 As for Mañaria ewers, one example presumably belonged to a liturgical set,Footnote 89 while another displays an explicit liturgical inscription.Footnote 90 Other types attested in Spain are indirectly connected to liturgical activities by finds recorded elsewhere: the Morbello ewers have been recorded both as a part of a probable liturgical set,Footnote 91 and in depictions showing them being used during the celebration of Mass;Footnote 92 an A2 ewer (Fig. 6: 5) is carved with an unambiguously liturgical inscription.Footnote 93

The sacral use of a significant part of the ewers recorded in Spain is thus noteworthy, but it is not possible to quantify precisely how many of them had such a function, and at which time in their lives. The examination of all the evidence on a Mediterranean-wide level demonstrates that there was in fact no correlation between the typological features of the cast bronze vessels and the archaeological contexts where they were uncovered: the items found in graves, concealed deposits, shipwrecks, and churches were all alike. With this in mind, it does not seem possible to categorize purchasers and users of the vessels as being either laypeople or clergy.Footnote 94

Conclusions

Like many other cities in the western Mediterranean, Carthago Spartaria underwent deep transformations between the 4th c. and the 7th c. Its older monumental buildings went through intensive changes as the city contracted in size: the area of the Forum, for instance, became a residential and craft quarter during the Byzantine period, as well as serving as a quarry for building material. The dumped fill of a deep pit contained an important assemblage of pottery, glass, and metalware, which mirrors the evolution of trade networks connecting the city with the Mediterranean in the 7th c.

The bronze cast ewer of Werner A2 type is an important piece of evidence allowing scholars to understand where and how this type of artifact was produced, and how it was distributed throughout the western Mediterranean. In all likelihood, these ewers were manufactured in the northern Adriatic (probably in Ravenna) and exported to both the western Mediterranean and central Europe. In coastal regions, their spread follows major Byzantine emporia; it is not by chance that an example was found in Cartagena, an important Byzantine center in southeastern Spain. The overall background of imports in Cartagena around 600–650 CE makes it very likely that the ewer reached Spain from Carthage, which in the 6th c. and part of the 7th c. may have played the part of a major redistribution center re-exporting African, Eastern, and Italian manufactured goods to the Spanish Levant.

This new ewer is nevertheless a further piece of evidence for connections between Italy and Byzantine Spania in the 6th–7th c., which are much better known from written accounts than from material remains. The close relationships between Pope Gregory the Great and several Hispanic bishops have been studied in depth.Footnote 95 Gregory I dedicated to Leander of Seville his Moralia in Job; it is established that a copy of Gregory's monumental study was brought to Licinianus of Cartagena by Leander himself, on his way back from Constantinople. Licinianus, for his part, wrote a very interesting letter to the pope. One must highlight, moreover, the correspondence between Gregory and one of his legal representatives, the defensor John (Registrum Epistolarum 13.47–50), sent to Spain in August 603 in response to the deposition and exile of two local bishops by the magister militum Spaniae, Comentiolus.Footnote 96 A few inscriptions found in the Spanish Levant also mirror the arrival of people from Byzantine Italy. Eutyches and Sambatios may have belonged to this group: in an epitaph located not far from Cartagena, Eutyches is mentioned as γρικóς, an ethnonym used in Italy to designate Greek people.Footnote 97

Frequent correspondence, the transportation of bulky books, travelers, and, of course, trade flows: all this evidence points to a renovatio, a renewal of the links between Italy and Spain at the turn of the 6th and 7th c. CE, taking place along seaborne routes in which Carthage, Cartagena, and the Balearic Islands played important roles. The arrival of A2 ewers in Spain was therefore tightly connected with new operational commercial networks resulting from Justinian's expansion in the western Mediterranean. Yet the circulation of cast bronze vessels long preceded Justinian's time: examples dated between the late 5th and the mid-6th c. (e.g., Pupput in North Africa, Favàritx in the Balearic Islands, probably Rome and Prepotto in Italy) are evidence of a trade network already connecting Egypt, Italy, Tunisia, and the Spanish Levant.Footnote 98

The spread of cast bronze vessels in the West faithfully mirrors the major economic trends of the 6th–8th c. The first objects belonging to this category seem to have been reintroduced in the West around 500 CE.Footnote 99 In all likelihood, at least some were originally manufactured in the eastern Mediterranean and transported by sea. These early imports gave birth rather rapidly to the first Western derivatives of Eastern products. During the course of the 6th c., however, contacts with the East became less frequent: by 600 CE, only a rather limited amount of cast bronze vessels significantly resembled their Eastern counterparts, while several indigenous types of vessels developed. This tendency became clearer throughout the 7th and 8th c.: as early as 630 CE, almost no cast ewer found in the West displayed clear connections with lands to the east; after 650 CE, the bulk of these objects were only regionally produced and distributed.Footnote 100 This was probably also the case of pansFootnote 101 and thuribles, as suggested by examples from Spain. Evidence of cast bronze vessels thus fits well with the overall picture given by pottery, finds from shipwrecks, and many written sources, all of which suggest a contraction in Mediterranean trade, the emergence of a multiplicity of local and regional production centers, and a rapid decrease in goods traveling long distances.Footnote 102 Just like African and Levantine pottery, the circulation of cast bronze vessels clearly points to the 7th c. as the turning point when ancient trade structures gradually, and yet definitively, vanished.Footnote 103