Campaigns don't harness civil society; the state employs administrative force to create a government movement. Leading cadres use inspections, assessments, and competition between officials; there's [color] and movement as propaganda starts up; and the results are announced with fanfare. At the end, everything is wonderful on the surface, with lessons learned and breakthroughs achieved … But in reality, it's either a formalistic breeze, with “documents implementing documents” and “meetings implementing meetings,” or a forceful campaign that leaves scars.

S.K. Zhao (quoted in Smith)Footnote 1In an unpublished working paper, Kristin Michelitch and Stephen Utych argue that scholars fail to examine fluctuations in party identification between election seasons and their off-cycles in democratic regimes, theorizing that, in fact, “the electoral cycle is a major determinant of citizen partisanship.”Footnote 2 While such a debate is ongoing, it also raises questions for nondemocracies: might authoritarian one-party systems also experience something akin to party identification – defined as affective proximity to the Party – that waxes and wanes over time? Such cycles would not hinge on elections, of course, but on the politics of succession, new policy initiatives and ad hoc housecleaning, and their focus would be on officials within the system as opposed to the electorate outside it. In this article, I argue that a key mechanism animating such variation in “party identification” among Chinese Communist Party (CCP) cadres lies within the recurring rectification efforts seeking to temper these individuals and make them more submissive to the larger political goals of the Party centre. Such priming of cadres is largely an in-house phenomenon, over time taking place progressively deeper within the CCP apparatus. This process involves an extensive arsenal of institutional mechanisms that combine into an especially big “stick” and within which pressures to comply can be uncomfortable, even excruciating. The normative elements of these movements – the language and substantive written materials used during study, analysis and self-criticism – are predominantly in the service of enhancing the sheer domineering quality of the Party vis-à-vis the individuals that make up its ranks.

This has larger implications for our understanding of China. First, intra-Party rectification is not something that can simply be dismissed as a product of the Mao era, and devoid of a post-1978 shelf life. By the same token, it also complicates the notion that Xi Jinping's 习近平 intra-Party anti-corruption measures and enhancement of Party dominance over state institutions represent a break from, rather than a linking-up with, past practices. Even as scholars like Anne-Marie Brady provide persuasive, extraordinarily fine-grained analyses on how the substance and even some of the institutions of the outward-looking propaganda system have shifted over time, the overall principles guiding intra-Party rectification have remained consistent.Footnote 3 Finally, the largely descriptive and empirical analysis that follows allows us to peer into the inner workings of intra-Party rectification and provides a fly-on-the-wall glimpse into some of the mid-level mechanisms in the service of political succession in China, which still remains among the blackest of black boxes.

In this article, I provide a close examination of an obscure political campaign that was anything but peripheral to the thousands of cadres at the chu 处 level and above who took part in it: the “three stresses” or san jiang 三讲. In so doing, I situate an extended, descriptive analysis within a broader analytical comparison with similar campaigns to help track changes and continuities over time.

The Three Stresses in Brief

Launched at the end of 1998, the “three stresses” (hereafter, 3S) initially appeared as yet another in an ongoing series of anti-corruption drives, in this case led by the National Audit Office (Zhonghua renmin gongheguo shenjishu 中伡人共和国审计署) with the goal of retrieving billions of yuan misappropriated by cadres throughout the system. However, the 3S movement soon revealed itself to be far more ambitious than that. It was nothing less than an attempt to extend soon-to-retire Party secretary Jiang Zemin's 江泽民 political influence over the incoming Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 leadership: “Jiang's most concerted attempt to stem the damage [from corruption] and to establish himself on a par with Mao Zedong” through “a Maoist-style political exercise based on criticism and self-criticism.”Footnote 4 And, like Maoist-style campaigns, there was a strong coercive element to it. Chinese Communications Bank president Wang Mingquan 王明权 wrote of being compelled to attend “dozens of group meetings in which [Party committee members] criticized their own and each other's personal failings [and attending] nearly 100 one-on-one political sessions with senior bank staff.” During the movement, each Party committee member was forced “to write an average of five drafts of a lengthy document detailing his political shortcomings” while “the committee produced seven drafts of another document about its political failings as a group.”Footnote 5

Inevitably, elements of the 3S entered the rumour-laden popular culture and the vernacular, long before the advent of social media, Weibo 微博, Weixin 微信, the wumao dang 五毛党, or the renrou sousuo 人肉搜索 (human flesh search engine). Some of these elements took the form of bawdy or gallows humour typical of citizens trapped in socialist systems. Lurid stories of uncertain provenance emerged of cadre excesses (with sometimes fatal consequences) in the context of the campaign, thus deepening rather than mitigating the movement's sinister underbelly.Footnote 6 Nor were foreign actors immune. When Princeton professor C.P. Chou visited Beijing in March 2000 to renew a summer language programme with Beijing Normal University, he was surprised to find himself on the defensive for “infiltrating American ideology into Chinese language teaching” and was warned that the teaching materials had to be modified extensively – and some dropped altogether – if the programme had any hope of being salvaged. Chou attributed this frigid political environment to the 3S.Footnote 7

Ultimately, Jiang's efforts appear to have had mixed success. There was a relatively institutionalized transfer of civilian power in 2002 (followed by a slightly bumpier one with the transfer of military authority the next year), with Jiang getting much of what he wanted, albeit with less post-16th Party Congress durability than he had sought. For cadres who had taken part in the 3S, it was a reminder that intra-Party rectification was not going the way of the planned economy or the work unit system. It remains part of the very fabric of reform-era governance.

Reform-era “Rectification” Movements

Much of the literature on campaigns in China focuses, not surprisingly, on the Mao era.Footnote 8 Some observers might note a touch of cognitive dissonance between the notion of campaigns in reform-era China to cultivate a “new socialist man” on the one hand, and the gleaming skyscrapers, shopping malls and globalization on the other. To students of China, however, such an apparent contradiction is nothing out of the ordinary. It has long been a governing imperative in China for the leadership to not simply seek to maintain its power, but to consistently and conscientiously endeavour to transform society. Unlike the Soviet Union, which became – as Mao mercilessly reminded its leaders in the 1960s – increasingly ossified and bureaucratized over time, pre-reform China found itself torn asunder by the centrifugal forces embedded in the Maoist contradiction between effective governance and radical Party-building. China's post-1978 reforms have not discontinued such preoccupations with societal transformation; they have simply moderated and complicated them.

Daniel Lynch has rightly argued that by the mid-1990s, commercial impulses and incentives had penetrated the traditional propaganda bureaucracies,Footnote 9 but “thought work” remains a key component of China's governance.Footnote 10 In their study on the effectiveness of policy implementation in China, Anna Ahlers and Gunter Schubert identify the “generation of ideological coherence by cadre training and ‘thought work’ (tongyi sixiang 统一思想)” as a way of maintaining a degree of smoothness in creating and enforcing local initiatives under the national banner of the “new socialist countryside.”Footnote 11 Yanhua Deng and Kevin O'Brien raise this issue in what they call “relational repression,” whereby local authorities threaten family members of those most likely to engage in protest with the loss of livelihood and other sanctions, forcing these relatives to act as agents to deter their kin from protesting and thus effectively injecting the state's “thought work” functions into the family unit.Footnote 12 Most recently, Haifeng Huang has argued persuasively that:

propaganda is often not used for indoctrination, but rather to signal the government's strength in maintaining social control and political order. More specifically, by being able to afford significant resources to present a unified propaganda message and impose it on citizens, a government that has a strong capacity in maintaining social control and political order can send a credible signal about this capacity and distinguish itself from a weak government … In other words, such propaganda is not meant to “brainwash” people with its specific content about how good the government is, but to forewarn the society about how strong it is via the act of the propaganda itself.Footnote 13

My argument is consistent with Huang's; however, my focus is not on outward-oriented propaganda but on intra-Party institutional processes. I also diverge from Huang in that I make more explicit the suggestion that such a response by the target can be affective as well as rational. The substantive content of propaganda may have some residual effects that, while a far cry from the “brainwashing” of the Manchurian Candidate, can nonetheless affect the targets of such movements and make them vulnerable to state messages by knocking those targets psychologically off-balance.Footnote 14

Finally, Elizabeth Perry's work on the durability of campaigns is relevant here as an indication of the wider phenomenon of historical continuity of state activism as well as to differentiate between the phenomena that she and I are discussing, respectively. Perry argues that the continuities between Maoist campaigns and contemporary movements have been overlooked by those who argue that Chinese leaders have become more technocratic over time, thus presumably eschewing the more mass-based or affective normative campaigns. She looks at Mao- and reform-era mass campaigns, with their emphasis on mass mobilization, while I look at intra-Party rectification. Contemporary campaigns, writes Perry, “are unabashedly pragmatic, searching for workable models wherever they may be found.”Footnote 15 Looking at the content and the process of the 3S, we see something that is more of a musty throwback to Maoism than the “new socialist countryside” movement analysed by Perry and others.Footnote 16

Views from the Inside

In the case of the intra-Party contemporary rectification of the 3S, it is challenging to define exactly what a contemporary “education and ideological movement” is. Can they legitimately be called “campaigns”? And if not, how do they differ? One reason it is difficult for outsiders to make sense of this is because the insiders themselves seem unable to fully square the circle. One particularly thoughtful cadre charged with implementing the 3S in his unit drew a precise distinction between “campaigns” (yundong 运动) and “movements” (huodong 活动). In his view, campaigns are comprised of two elements. The first serves to educate people about a given problem or problems to be solved. He noted that while there is nothing inherently negative about this, there is an inherent “tendency to overdo it” (guotou, guoji de fangshi 过头, 过激的方式) and push outcomes into negative, critical territory. The second element is that of “rectifying people” (zheng ren 整人), a mechanism employed to change people's outlook. Like the educational component, he regarded the rectification dimension as generally positive when it was used in a “rational” (heli 合理) sense; that is, if the targets were legitimate ones (daji de duixiang shi yinggai de 打击的对象是应该的) and the rectification was employed, as he noted, in the service of education.

Like many, he drew from Yan'an 延安 to give an example of when rectification (zhengfeng 整风) was used in a positive, effective manner, but pointed to the “anti-rightist” campaign of 1957–1958 as the point when this rectification element began to be abused and started getting out of hand (luan de zhengzhuang 乱的症状), in large part because the campaigns themselves “had become too big” (kuangdahua 圹大化) and had consequently become unmanageable and ripe for abuse.Footnote 17

He went on to say that movements differed from campaigns in that while both contained an educational component, reform-era movements do not have the elements of rectification. If the misbehaviour uncovered is deemed to be serious enough, it is handled, at least in the case of the 3S, by the legal-security system including the public security bureaus and the people's procuracy, while the majority of offences, which are small, are handled in-house within the work unit (danwei 单位) in question.Footnote 18 When placed along a continuum bookended by the 1983 “rectification” movement and Xi's “anti-corruption” campaign, the trend suggests more rather than less embeddedness within the Party over time, as we will see below.

Another cadre intimately involved with the 3S had more difficulty fully extricating contemporary movements from traditional campaigns. He asserted that movements went out of their way to demonstrate that they were not the “rectification” campaigns of old in that while they evoked the “spirit” of rectification, they substantially shifted the emphasis away from traditional methods or eschewed them altogether. He also brought up Yan'an, noting that while rectification in the 1940s worked quite well, the contemporary spirit of these movements is more “objective,” with less of an emphasis on punishment and more of a benevolent focus on improvement and narrowing the gap between one's performance and the ideal of how one should perform one's job, using self-reflection (as distinct from criticism or, more accurately, the way criticism has been abused in the past) as a way to help oneself “get things right.” Above all else, contemporary movements were orderly (bu luan fanzheng 不乱反政).Footnote 19

Still another cadre made no such distinction: he used “movement” and “campaign” interchangeably throughout our interviews, pointing out that nobody uses the word “campaign” anymore – that term having been supplanted by “movement” – even as he dismissed this modern usage as simply a matter of semantics.Footnote 20 This is consistent with Joseph Fewsmith, who not only finds little analytical support for such a distinction but also suggests that the “rectification” element remains very much in play, as he notes with reference to the movement to “maintain the advanced nature of Chinese Communist Party members,” which

marks the third “rectification” campaign undertaken by the CCP since the death of Mao (party people in Beijing referred to it as a “rectification” campaign even though it is officially being called “educational activities”). In 1983, the party launched a rectification movement to root out those who continued to support the goals of the Cultural Revolution and the Gang of Four. In 1998, the CCP launched the “three stress” (sanjiang) campaign – stress study, stress politics, and stress righteousness (jiang xuexi, jiang zhengzhi, jiang zhengqi). Not coincidentally, those two previous campaigns were closely associated with the consolidation of the “lines” of Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin, respectively.Footnote 21

The conclusion to be drawn from analysing these insiders' views and recent scholarship on the subject is that contemporary educational and ideological movements represent neither a break with traditional Maoist-style campaigns, nor are they simply a diluted version of them. Both are, rather, points along an evolving trajectory of Party norms, structures and procedures, responding to the perceived challenges faced by the CCP, specific to the times in which they are adopted. Their aggregate effect is to demonstrate directly to Party cadres the state's continued dominance over them, which is the subject of the next section.

Framework for Analysis

Referring back to the beginning of this article and comparisons with party association in democratic systems, it might seem pedantic to state the obvious: that China's is a system in which political turnover is not determined by elections but by internal institutional mechanisms. But doing so helps us to link intra-Party rectification with the larger political goal of revitalizing the Party (at least as stipulated by CCP elites), or, the authoritarian equivalent of “throwing the bums out.” Generational replacement is too long a time horizon and the probability of unanticipated outcomes is too risky for any leader or group in the position of recasting the Party in its own image to rely upon. Rather, intra-Party rectification provides the mechanism for these leaders to establish their preferred political trajectory by “tempering” the rank-and-file into greater complacency with the political process; that is, intimidating any potential opponents or foot-draggers through a demonstration of the sheer power and scope of the CCP. The effect is not to mobilize cadres in the traditional Maoist fashion, but to wear them down, to emasculate them in full view of the Party (and their colleagues within it). This has extended into Chinese living rooms with televised images of cadres targeted by Xi on corruption charges being rounded up, publicly shamed, and relieved of their posts while others nervously await their fate.Footnote 22

The normative dimension of such intra-Party rectification also serves to enhance the power of the CCP: opponents are not only in disagreement with the Party, they are wrong. And, not only are they wrong but, in the inexorable forward movement of Marxism, they have placed themselves on the wrong side of history.Footnote 23 Unlike the carrots used by parties in democratic systems to get their constituents to the polls, this is a stick, and a considerable one at that. It engenders precisely the opposite dynamic that Kevin O'Brien and Lianjiang Li find among peasants expressing “campaign nostalgia.”Footnote 24 It is something that cadres often dread or at the very least resent as a very real distraction. Diverging somewhat from Christian Sorace, who argues that language is critical to understanding Party behaviour, I concentrate here on the delivery systems of such language, the institutional structures and processes that set the parameters of these movements,Footnote 25 which serve the same purpose as that which Hung Chang-tai assigns to aesthetic forms in Maoist China: ploys of domination.Footnote 26

The two cases I draw upon to place the 3S within a larger comparative context are the 1983 “rectification” movement and the currently unfolding anti-corruption campaign of Xi Jinping. The two main conceptual reasons for selecting these cases are, first, that they are clearly concerned with intra-Party rectification, and, second, that the broader time frame they encompass as a group helps tease out temporal continuities that otherwise might be imperceptible. Temporally, the 3S is the least likely case to invoke Maoist-style rectification, occurring as it did late in the Jiang Zemin era, as distinct from the hardscrabble early 1980s or the retrogressive Thermidorian reaction to reform unfolding under Xi. My analytical framework focuses more on procedure than on causality,Footnote 27 and my empirical focus is on the 3S precisely because it is the least studied of the three.

It is challenging to situate the 3S in a satisfying comparative context for several reasons. First, very little information is available on the inner workings of this type of political phenomenon, and so one must stray outside one's comfort zone to lean a bit more on inferential analysis. Second, the movements themselves are composed of many moving parts that simultaneously underscore similarities as well as dimensions which defy easy comparison. Third, they take place in the context of contemporaneous political events that can profoundly affect the substantive and the procedural features of these movements.Footnote 28 Finally, given the pre-Xi reform era leaders' reluctance to invoke Mao too baldly, these campaigns were often deliberately couched in terms that conceal what they really are: intra-Party rectification.

All of these movements are somehow in the service of political succession, broadly defined. This might refer to the mechanism of placing emerging leaders on a more solid footing regarding Party legitimacy (Hu Jintao, Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 on behalf of Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦). They could be an attempt by a leader to enshrine his own personal legacy through leveraging the potential Party selectorate to accept that leader's protégés into key positions after that leader steps down (Jiang Zemin).Footnote 29 Or they might be associated with a larger political movement that will forever be associated with that leader (Jiang Zemin, Xi Jinping).

The very existence of the 1983 “rectification” movement is often obscured because of its hijacking by the “anti-spiritual pollution” campaign, and the subsequent inaccurate conflation of the two, as Thomas Gold cogently points out. Although the content – “restructuring Party-state–society relations, democratizing political life, and subordinating Party and non-Party activities to the rule of law”Footnote 30 – was significantly different from the 3S and Xi Jinping's anti-corruption drive, the process was similar along key dimensions. The political goal of the 1983 “rectification” movement was the removal of CCP cadres who had risen through the ranks as supporters of the Gang of Four and the Lin Biao 林彪 “cliques,” and replacing them with more forward-looking pragmatic officials. Like the 3S, it was conspicuously not referred to as “rectification” (zhengfeng 整风) as used in a Maoist context but instead employed the slightly less sinister sounding term zhengdun 整顿, which Gold points out was inaccurately translated, perhaps even deliberately so as to mask its Maoist connotations, as “consolidation.” It was originally scheduled to take place over three years (a similar time frame to the 3S, when subnational units are taken into account). Also, like the 3S, “rectification [was to] proceed in an orderly manner, from the top down, relying on the study of required texts and criticism–self-criticism.”Footnote 31 Equally important from a comparative perspective, “on no account should the past erroneous practice of ‘letting the masses consolidate the Party’ or letting non-Party members decide issues in the Party be repeated”: this was the CCP of Liu Shaoqi 刘少奇, in which rectification was to be undertaken “in house,” without mobilizing extra-state actors.Footnote 32

Xi Jinping's anti-corruption campaign poses more of a challenge for at least two reasons. First, the relative lack of constraints on Xi's ability to manoeuvre makes it appear qualitatively different from the other two (after all, Deng had Chen Yun 陈云 to provide ballast). Second, it is currently unfolding in real time, and thus does not provide us with an endpoint from which to look back. That said, Xi's anti-corruption drive can be broadly understood as a rectification campaign in that its fundamental aim is the targeting of misbehaving cadres for intra-Party punishment. At the same time, it departs from traditional rectification doctrine (which demonstrates more parallels with the 3S) and approximates instead the ratcheting-up and subsequent debasement of rectification in the later stages at Yan'an and in the People's Republic of China (PRC) after 1957. This intensification of rectification signalled a shift away from the traditional Maoist notion of “curing the sickness to save the patient” and towards the Soviet analogy of “ridding the machine of parts that no longer work.”Footnote 33

Another key dimension upon which to compare the present day with earlier movements has to do with the in-house nature of cadre rectification. As we will see, the trend seems to be moving very much in the direction of more, rather than less, Party oversight. While the 3S turned over certain errant cadres to the government judicial apparatus, Xi has instead relied heavily on the CCP's Central Discipline Inspection Commission (Zhongguo gongchandang zhongyang jilü jiancha weiyuanhui 中国共产党中央纪律检查委员会). This is consistent with Xi's ambitions for expanding the Party's reach, through a set of complex and powerful CCP leadership small groups, into a number of functions traditionally or more recently associated with the government.Footnote 34

Finally, there is a strong affective element to this campaign, in which such cadre evaluation goes beyond simply being a human resources or even a legal issue to being one of genuine existential crisis. The most dramatic manifestation of this is the dozens of cadre suicides (euphemistically referred to as “unnatural deaths”) since 2013.Footnote 35 The message to those who are on the sharp end of this campaign as well as to those who have been spared (so far) is twofold: specifically, to refrain from corruption, and to “keep the Party very much in mind as you undertake decisions affecting work.”

All these movements demonstrate similarities with earlier campaigns. These include the use of self-criticisms, high-pressure group sessions, pressures towards conforming to a stated set of political norms, study sessions, and an apparent disregard for the opportunity costs on the predictable, rational, policy-based functioning of the ship of state while such a movement is taking place. Consistent with Perry's findings:

Like their Maoist forerunners, managed campaigns posit a close connection between subjective consciousness and objective … gains. Intensive political propaganda, intended to arouse emotional enthusiasm and enlist widespread engagement, remains a central element. So, too, does a call for struggle and sacrifice in service to a larger cause.Footnote 36

A consequence of this is the considerable degree of anxiety and stress that such a contemporary educational and ideological movement introduces into a cadre's professional experience. Quite apart from the trauma of being targeted in such a movement, the loss of time and other opportunities to the exigencies of the movement creates an environment in which a cadre must accomplish more tasks in less time while under the enhanced scrutiny of his superiors, at least for the duration of the movement but also in anticipation of the next one. This stress can be used to knock cadres off their game and make them vulnerable (and more malleable) to the goals of the movement. Xi's comment that officials “should not have the wrong idea that they have passed the test just because the sessions are over” perfectly captures this.Footnote 37 All of these points become clearer as one traces the actual structure and process of the aptly-named “three stresses.”

The “Three Stresses”: Structure and Process

In the summer of 1999, Beijing was one big construction site consumed with preparations for the 50th anniversary celebrations of the PRC. While the media was consumed with the anti-Falun Gong crackdown, cadres were being pulled out of their offices en masse to participate in what remains today an obscure movement to people outside of it but one that has left political bruises and scars for many who participated in it. The scope conditions for the movement were established at the centre by Jiang Zemin, with Hu Jintao playing an important supporting role, and were to involve all cadres at the director/county (chu) rank and above, all the way down to the county level (see Figure 1). As rumours circulated indicating that a new movement was coming down the pike, and even as the 3S movement was taking shape, CCP cadres did what they always do: they asked themselves what were the real reasons, the real issues behind the movement?

Figure 1: Rank and Authority Relations in China

One participant mused that it had to do with Jiang's desire to “have something inscribed on his tombstone” to establish his historical legacy, a political struggle, perhaps setting up a “frame” to facilitate succession politics, or perhaps it was yet another ineffective anti-corruption campaign.Footnote 38 In fact, it could be any or all of these, but even as Party instructions were passed down and as the 3S became more clearly defined, the official pronouncements bombarding these targets were always slightly different from those they experienced “from the inside.” Substantively, in summary form, they included the following.

-

■ Stress Study (jiang xuexi 讲学习): this emphasized the study of certain texts by Mao Zedong 毛泽东, Deng Xiaoping and, especially, Jiang Zemin, that were deemed important to the movement's goals. This differed somewhat from the official line, which was that “education should be everybody's lifelong goal.” Rather, it helped set the historical resonance of the movement and the stakes for those caught up within it.

-

■ Stress Politics (jiang zhengzhi 讲政治): this was more straightforward; that is, to follow the goals and objectives of the Party. The specific overarching political theme here was to sacrifice one's own individual self-interest in favour of the interests of the CCP.

-

■ Stress Righteousness (jiang zhengqi 讲正气): this did not refer to mainstream justice within society in the general sense, but rather emphasized what was “correct” vis-à-vis the Party. There was extensive use of model workers to establish what constituted the “right” behaviour and outlook in various professional settings.

The ostensible goal of the 3S was to unite everybody's thought with the Party centre's ideas and ideological orientation of the time. The meta-level goal was even more clear and unambiguous: to intimately underscore to CCP cadres that simply by virtue of being able to launch the 3S (and other rectification movements), the Party was in full control of the political system, trumping with extreme prejudice any power its individual members may have accumulated over time.Footnote 39

In a national-level ministry, the movement would begin with an assembly of up to 1,000 employees during which the minister – who had already been briefed extensively – would read a document that one source described as different from a normal “report” (rather, he called it “propaganda,” something specifically that initiates a movement). Drawing from this document, the minister would sketch out the parameters of the movement and how long it would last (in this case, roughly two to three years). He would also underscore that the Party has a tradition of rethinking problems and learning from experience and that this movement falls into a pattern. From movement to movement, the nature of this announcement is largely the same, differing only in the particulars.

My source said that the minister would invariably note that “this movement will not affect work,” but that, in fact, it would “dialectically” (bianzhengfa 辩证法) benefit work and make it more efficient. This would be followed, equally invariably, by an inaudible collective groan among the audience because nobody believed this to be true. Based on ample prior experience, these movements do indeed cut into and beyond work time and make everybody's job even more frantic. In fact, the stress involved in such doubling-up of responsibilities is one of the key mechanisms used by the movement to reach its goals. The minister would continue with exhortations to the staff to plan their work and study well, and then finish with a statement that there would be an evaluative period at the end of the movement.Footnote 40

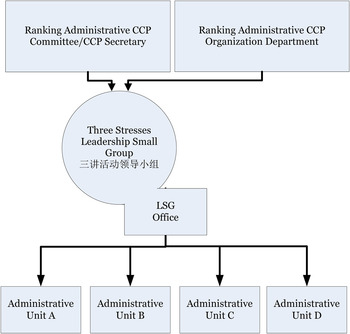

As soon as a given unit was put on notice in this way, the person responsible for managing the movement (dongyuan 动员) at a given administrative level, usually the secretary of the Party organization department, would begin preparations by establishing the institutional mechanisms. At the provincial level, the organizational landscape for the movement could get quite complicated. Three stresses leadership small groups (sanjiang lingdao xiaozu 三讲领导小组, hereafter LSG) were established and managed by the provincial Party committee secretary and the provincial CCP organization department. Members might also include the provincial governor, CCP secretary, their immediate subordinates and others such as leaders of the provincial people's congress. Altogether, an LSG comprised several dozen members. The LSG administrative office, or ban 办, was divided into four different divisions, each of which had its own 3S work supervision group (sanjiang huodong gongzuo dudao xiaozu 三讲活动工作督导小组). Figure 2 illustrates the organizational structure of the LSG.

Figure 2: The Three Stresses Leadership Small Group Structure

Functionally, at the bureau (or ting 厅/ju 局, below simply referred to as ju) level, and at geographically defined units of the chu level and higher (i.e. the di zhou shi 地州市), 3S LSGs were also established. At the di zhou shi level, there was a 3S LSG, which represented the CCP organization department, to investigate heads of county governments and Party committees.Footnote 41

Rank and Authority Relations

Above the chu level, the examinations would involve other configurations of power and authority. For example, provincial governors, vice-governors, and provincial CCP secretaries would be evaluated by officials from the centre as well as by equal-ranking officials from other provinces convening the meetings for the ranking provincial-level cadres. At the bureau level and higher, the director, vice-director, and bureau CCP secretary were evaluated by bureau-level officials from other bureaus, and one of these Party cadres (from a bureau not undergoing meetings at the same stage of the movement) acted as a facilitator and as a representative of the provincial-level organization department. A municipal-level ranking official could also undertake this facilitating role if they (i.e. their municipality) had the same rank (ju) as a bureau. For prefectural- (and vice-prefectural-) level government and Party cadres, their group leaders were either their peers from other municipalities within the province or bureau-level officials from a bureau within the provincial government.Footnote 42

Stage One

Stage one of the process of the movement was relatively straightforward. From the centre on down, the first step was a meeting to which the unit's CCP secretary would summon all the officials at the chu level and higher.Footnote 43 He or she would give a report about the 3S, stating the aims (zongzhi 宗旨) of the movement, what the targets (mudi 目的) were, and what the major stages or steps (zhuyao de buzhou 主要的步骤) would be. After this initial meeting, there was a period of study for up to three months. This stage is referred to, alternatively, as “thought mobilization” (sixiang fandong 思想发动) or “grasping the spirit of the upper echelons” (linghui shangji jingshen 领会上级精神). During this stage of the movement, one day (or two half-days) a week were devoted to studying the materials prepared for the movement. These materials included the following:

-

■ The report of the 15th CCP Party Congress and the Party Constitution;

-

■ Relevant writings for the “three stresses” drawn from Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, and Jiang Zemin;

-

■ Interim Regulations on the Selection and Appointment of Leading Party and Government Cadres (1995), No. 4 (Dang zheng lingdao ganbu xuanba renyong gongzuo zhanxing tiaoli [zhongfa] 4 hao 党政领导干部选拔任用工作暂行条例 [中发] (1995) 4 号);

-

■ Several Criteria for Political Honesty among Chinese Communist Party Members and Leading Cadres [Provisional] (1997) No. 9 (Zhongguo gongchandang dangyuan lingdao ganbu lianjie congzheng ruogan zhunze (shixing) [zhongfa] (1997) 9 hao 中国共产党党员领导干部廉洁从政若干准则 (试行)[中发] (1997) 9 号).

Movement participants were expected to take these materials home with them to study after working hours. During the workday, time would also be set aside for co-workers to discuss the materials and the movement amongst themselves.Footnote 44

Stage Two

After this initial phase was completed, participants prepared for stage two. Here they were told to start preparing materials for their “self-analysis and opinion sharing” (ziwo poxi, tingqu yijian 自我破析, 听取意见) reports. The central feature that drove these reports was the identification of ideological inconsistencies (fansi 反思) between the ways in which one approaches one's own work and the ideals and expectations of the 3S movement.Footnote 45 One cadre involved in the process recalled that as people prepared their “self-analysis materials,” they were told explicitly not to include any positive examples and to focus only on the negatives.Footnote 46 Another said that “you would be asked to raise your opinions, but ‘opinions’ in a negative sense, about oneself, one's peers and one's supervisor. There were attempts to make these criticisms harmless, vague and pro forma: ‘need to work harder … need to study more … etc’.”Footnote 47 But this could, and did, vary.

After writing a self-criticism, the individual was expected to appear in front of a group (that could be as large as several dozen people at the national levelFootnote 48 ) within their organization. At the provincial level, bureaus might have five to seven departments (chu), and a meeting would comprise each of the chu-level officials and the bureau director. In this meeting, each of the chu-level officials had to give an oral report of their self-analysis.Footnote 49 This was usually handled fairly rapidly, often within a week, as while all of this was fresh in people's minds (and while they were still vulnerable), stage three would begin.

Stage Three

If the group concluded that an individual's self-examination was accurate and complete, it would move forward to the next stage. If not – for example, if the “offences” that were uncovered were minor – the person would go back to stage two and revise his or her self-examination. If what was uncovered was sufficiently “serious” (fanzui 犯罪), the case would be referred to the legal-security system which, in the case of the 3S, included the public security xitong 系统 and the people's procuracy.Footnote 50 This appears to be an important difference with Xi Jinping's current emphasis on handling everything within the CCP's Central Discipline Inspection Commission.

If revised self-examinations did not pass muster (and charges did not warrant prosecution), the subject was required to “earnestly rectify, and consolidate one's achievements” (renzhen zhenggai, gonggu chengguo 认真整改, 巩固成果) by “sending them down to the masses.” What this means in its post-Mao context is that the individual would be sent to the “street-level” administrative rung of the policy area in which they worked, after which their work would centre on precisely the area in which their self-examination was found to be wanting. One cadre used an analogy to illustrate this process:

If you were ultimately responsible for a market being well-stocked (even if that was not something you ordinarily handled directly, or even indirectly) but it was lacking in food (and that this could be traced back to your below-par performance in the self-analysis), you went down and spoke with the people involved in the day-to-day operations of that market to find a way to improve things. And you stayed.

After an appropriate measure of time, the cadre would then be reviewed by “the masses” (subordinates) in the work unit, and if an absolute majority approved, the cadre was eligible to “pass” (tongguo 通过).Footnote 51 If the cadre subsequently demonstrated a tendency to slide back again into old work habits, more institutionalized measures would be brought to bear.Footnote 52 Figure 3 provides an overview of the stages involved in the whole process.

Figure 3: The Procedure of the Three Stresses Movement

There was some regional variation in terms of how this final stage was implemented. Officials in Shaanxi province identified problems to be solved through “reflection by the masses” (qunzhong fanying qianglie 群众反映强烈), such as arbitrary fees for school tuition. Provincial government and CCP committees demanded that primary and middle schools at all administrative levels publish and execute to the letter the provincial education commission's directive regarding the standards of payment for primary and middle school tuition. If they found instances of such arbitrary levies, regardless of the cause, the head of the school was removed on the spot. Investigated counties and urban districts which passed muster amounted to about 95 per cent, with the other five per cent of education bureau directors removed from office and the responsible county governors given a warning that there would be a year-end assessment to see if the practice was still in place. If within a municipality or prefecture there were three or more counties in which the standard was insufficient, the municipal education bureau director was removed from office and his/her superior (i.e. the mayor) was also called to account. Altogether 27,119 schools (or three-quarters of the total) were investigated, and 983 were ordered to pay back the arbitrary fees they had levied.

In Gansu, the campaign was directed towards the still-existing problems with CCP cadres' work style and honest governance, concentrating on prosecuting seven high-profile cases in which four prefecture-level directors (chuzhang 处长) and two dozen county magistrates were engaged in corrupt activity. The authorities found that the biggest problem was the misappropriation of property by leading cadres, involving more than 1,629 apartments costing a total of 51 million yuan. The campaign was also directed at the imposition of inordinate burdens on the peasantry, including some 71 projects and 254 individual cases, and lightening the burdens on the peasantry by some 230 million yuan.

In Shandong, the focus was on serious discipline problems. By January 2000, throughout the entire province, 232 ju-level cadres and 15,801 cadres at the chu level (and below) were forced to give up some 15,926 dubiously-acquired houses.Footnote 53

This part of the 3S movement seems to have been the most involved as well as the most challenging, and depended a great deal on how much top-down pressure was unleashed. For the most part, the criticisms that were levelled were verbal, although sometimes they were written down and in some instances anonymously provided in mailboxes established specifically for that purpose. Various chu-level officials, around five to seven in number, would have a meeting to discuss their ju-level superior. This superior official would not be present at the meeting; rather, the meeting would be led by a representative of the ju-level 3S LSG. The information gleaned from this meeting would then be combined with the self-analysis materials of the official in question. The data contained in these exchanges obviously had lasting consequences. How people fared in the 3S was germane to their chances for promotion. If people performed well, they were reinstated and eventually moved up in the system; if they did not, but their shortcomings were not actionable, they were demoted or left behind during promotion cycles. Finally, another, bottom-up style of criticism took place that was less common than the top-down variety, but it may nonetheless have led to an undermining of the cadres' power vis-à-vis their subordinates: a tacit agreement that the superiors would avoid “sending people down” if subordinates kept their criticisms of their superiors in check, and a general feeling of unease that surrounded the whole exercise, as superiors and subordinates alike found themselves vulnerable.

Conclusion

In Maoist China, officials could lose their livelihoods, freedoms and even their lives if they ran afoul of the Party. Nowadays, these same officials might lose their livelihoods and, if their transgressions are suitably egregious, their freedom as well. Mass campaigns have been replaced by in-house measures that are not only inward-looking but, to varying degrees, fairly invisible to those on the outside looking in. The 3S movement represents an example of reform-era rectification that, when taken in comparative context, suggests some larger trends that might also help observers make sense of what is unfolding in China today.

First, the stakes of these movements remain extremely high: they revolve around issues of job security, promotion, status, and even, as noted, the loss of livelihood. These are non-trivial matters and they force participants into taking the consequences – and thus the processes – very seriously. These movements are different from benign professional “retreats,” conferences or workshops. They encompass the possibilities of future employment, not simply professional development. Moreover, if a cadre is determined to have erred in a particularly problematic way, whether espousing ultra-leftist views in the early 1980s or engaging in corrupt behaviour today, it no longer becomes a question of retaining a pay cheque; it raises the very real possibility of incarceration.

Second, in terms of the approach I have employed here, the substance of these movements is important insofar as it underscores the extraordinary power asymmetries of an individual cadre participating in them vis-à-vis the dominating Party apparatus within which he or she works. This asymmetry makes clear to the cadre in question just how insignificant he or she is in the face of the full historical force of the CCP, all the more so once the cadre has been professionally isolated from everything else but the Party during the course of the movement in question. This places the cadre in an uncomfortably intimate degree of affective proximity to the CCP, and leaves that official particularly vulnerable to Party dictates.

Finally, over time, supervision and ownership of a given movement seem to have become increasingly placed within the hands of the Party itself. If one of the goals in 1983 was “subordinating Party and non-Party activities to the rule of law,”Footnote 54 this has changed dramatically today as Xi Jinping constructs an ever-increasing web of Party-based leading small groups in charge of policy areas hitherto squarely within the realm of the government. Indeed, the reliance on the CCP Central Discipline Inspection system not only impedes government-based “law and order” functions as seen in the 3S, it reverses trends going back to, and articulated by, the 1983 “rectification” movement. If this long-term trajectory continues, the implications for prospects of political liberalization in China are significant and sobering.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Lane Lan for her extraordinary research assistance and to Cole DeVoy for his editorial help. I also thank Carl Minzner, Maria Repnikova, Vivienne Shue, and three anonymous reviewers for extremely helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article. Any remaining errors are mine.

Biographical note

Andrew Mertha is professor of government at Cornell University. He is the author of The Politics of Piracy: Intellectual Property in Contemporary China (Cornell University Press, 2005), China's Water Warriors: Citizen Action and Policy Change (Cornell University Press, 2008), and Brothers in Arms: Chinese Aid to the Khmer Rouge, 1975–1979 (Cornell University Press, 2014).