Part I Historical overview of the genre

2 The Viennese symphony 1750 to 1827

Mozart, recently dismissed from the service of the Archbishop of Salzburg, wrote optimistically to his father on 4 April 1781, claiming that Vienna was the best place in the world for someone of his profession.1 It is understandable that he should have formed this impression of the Austrian capital. It had an abundant infrastructure for musical production and consumption. In the main, this was a result of both the Hapsburg dynasty, for whom Vienna already had been the principal residency for over a century, and of the Holy Roman Empire.2Together, the monarchy (Maria Theresa from 1740 to 1780; Joseph II from 1780 to 1790, Leopold II from 1790 to 1792 and Francis II from 1792 to 1835), and the Holy Roman Emperors (successively Francis I, Maria Theresa’s husband until 1765, thereafter Joseph II, Leopold II and Francis II, until the Empire’s abolition in 1806) brought in train a bureaucracy numbering, by Mozart’s time, at least 10,000. Vienna was a hive of political and cultural activity and acted as a magnet for many thousands of affluent nobles resident in the city or else more-or-less loosely inhabiting its peripheries. One such was Prince Joseph Friedrich von Sachsen-Hildburghausen, whose musical establishment was among the finest in Vienna, in which the twelve-year-old Carl Ditters (later, 1773, von Dittersdorf) received his musical instruction and a first taste of orchestral playing. Diversity of opportunity acted as a powerful generator for the city’s rich and varied musical life. It is against this background that the hundreds of musicians employed in court establishments such as the Hofkapelle worked. Successive Kapellmeisters Georg von Reutter (1751–72), Florian Leopold Gassmann (1772–4), Giuseppe Bonno (1774–88) and Antonio Salieri (1788–1825) were, in effect, civil servants whose positions were assured for life. Others enjoyed a more precarious living as singers, players and teachers.

While Vienna’s public concert life does not look so active as, say, London’s at the same time,3 that impression hides the fact that ‘public’ does not necessarily mean an event in a dedicated concert hall with tickets on sale to the ‘public-at-large’. True, in Mozart’s Vienna, there was a dearth of what might pass for ‘concert halls’, but he managed to give, as a soloist and part-promoter, over seventy concerts there in the first five years following his arrival in 1781. Concert series were supported by the Vienna Tonkünstlersocietät from 1772, and subsequently by the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (from 1814). Venues for concerts were diverse, and included theatres such as the Kärntnertortheater (originally built in 1709, burned down and rebuilt in 1761 from which point it was managed by the court as a centre for German-language comedies), and the Burgtheater (where Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice had received its premiere in 1762 and later established as a National Theatre by the future Joseph II in 1776), the Augarten (a royal park, opened to the public by Joseph), the Mehlgrube dance hall, Jahn’s restaurant, the Trattnerhof, masonic lodges (especially during the early 1780s), and in the palaces of the aristocracy (Prince Auersperg’s, for instance) as well as in the homes of, for instance, Baron Gottfried van Swieten, Joseph II’s education minister. Many concerts are known to have taken place in the homes of Vienna’s nobility. Not all these locations supported symphonic repertoire, though Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony received its first performance in the palace of Prince Lobkowitz in 1804 (it was rehearsed by the Prince’s own orchestra).

Increasingly at the turn of the century the royal and imperial court was overtaken as a source of patronage by the nobility, most especially in the field of instrumental music. Beethoven, who made Vienna his home from 1792, was supported almost wholly by the aristocracy, to whom he dedicated many works and who seem to have perceived in his instrumental output an expressive voice whose originality and universality of appeal sat uncomfortably with past arenas of patronage in which a musician was a mere servant. To a degree his output, including his symphonic output, shaped the taste of the high aristocracy, rather than vice versa. Allied to the aristocratic engagement with a developing aesthetic of instrumental music and its possible meanings was an emerging civic musical scene in which a freshly liberated genre such as the symphony might find a stage for its representation to an inquisitive public. While it is undoubtedly true that the political repression of the Metternich era restricted the growth of public musical concerts in Vienna (from 1815 large public gatherings were systematically forbidden within what was effectively a police state), music itself was not a focus of censorship. Starting in 1819, Franz Xavier Gebauer and Eduard von Lannoy promoted the Viennese ‘concerts spirituels’ – public events given by an amateur orchestra, and featuring symphonies by Haydn (who, from 1790 until his death had been resident in Vienna, though his later symphonies were written for London’s, not Vienna’s concert life), Mozart and Beethoven. Professional performances of instrumental repertoire, however, tended on the whole to take place in aristocratic and affluent bourgeois homes in the Viennese suburbs, rather than in large public spaces. Nevertheless, these gatherings were a species of what we would call concerts and provided a space in which the symphony might enter into a dialogue with its listeners; this would affect its generic boundaries while simultaneously catalysing the musical appreciation of those listeners. Presentation of a symphony in the context of a concert affected the composer’s organisation of his material. Since the audience was there on purpose, and actually listening to the music, it was essential that the musical material displayed some degree of logic in its construction; that it engaged the senses and perhaps also the minds of those listeners; that it emphasised points of departure and arrival, as well as contrasts of theme, key and texture; that it deployed the orchestral forces in an exciting way. In a direct sense the concert context dictated the manner in which the symphony proclaimed itself to the audience. That relationship between the symphony and the audience manifested itself in various ways, for instance in terms of continuity: a symphony was performed as a whole in such settings – albeit with applause, or even other compositions in other genres as quasi-entr’actes between movements – which inevitably focussed attention on the relative qualities, scorings, lengths, affekt or thematic interrelations between movements, including overtly cyclic ones as in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. This situation defines the symphony generically as something existing in relation to a perceiver who is challenged in a particular representation to form an impression of it on, for example, an emotional level, or in constructional terms, and perhaps in relation to other, similar works. In other words, its generic identity emerges through its particular usage, and a concert representation was in contrast to the usage sometimes made of individual symphonic movements in the mid eighteenth century at the Gradual or Offertory in celebrations of Mass, either within large Viennese churches or in nearby monasteries. The diary of Beda Hübner, Librarian at St Peter’s Benedictine Monastery in Salzburg, records that on 8 December in Salzburg Cathedral one of the infant Mozart ’s symphonies was performed at Mass to the great delight of all the assembled musicians. Likewise, some symphonies by Karl von Ordonez (1734–86) were evidently intended for such situations; manuscript copies are found in the monastery of Göttweig (copies of Haydn’s symphonies are likewise preserved in monastery libraries).

Public representation of a symphony to a paying audience from different social classes, which has come together for a concert representation of orchestral music at a particular time and place, is a different matter to its representation by liveried musician-servants with polished shoe-buckles before an Empress and her retinue in between the courses of a banquet. Even when such performances were notionally ‘concerts’, they were primarily social occasions at which there was also music (to judge from the diaries of aristocrats such as Count Karl Zinzendorf). The arena in which the symphonies of Beethoven were presented to the Viennese of the early nineteenth century and that in which the symphonies of Georg Christoph Wagenseil (1715–77; Wagenseil was Maria Theresa’s music teacher) were produced are different creatures indeed, and mark out the approximate boundaries of the journey of the Viennese symphony to be explored below.

Beginnings

The influence of the Hapsburgs stretched far and wide, geographically as well as culturally. Vienna was a cultural crossroads and acted as a magnet for composers from parts of Germany, the Czech lands, present-day Slovenia and northern Italy. In the eighteenth century the region of Lombardy was a Hapsburg dominion and this goes some way towards explaining the early stylistic development of the symphony in Vienna, which owes much to the three-movement operatic overture of the type found in the work of Leo, Sammartini, Jommelli and Galuppi (this repertoire is considered in more detail in chapters 3 and 6). Their overtures during the 1740s and 1750s typically feature in their opening movements a clearly coordinated approach to thematic and tonal statement, contrast and return in which uniformity of baroque rhythmic patterning has been sacrificed for an overall symmetry of four- and eight-bar phrase and cadence schemes delineated by relatively slow and regular harmonic rhythms and an almost stereotypical functional hierarchy within the orchestration (leading melodies stated by the upper strings, perhaps reinforced by a pair of oboes, to which an energetic bass line of lower strings – perhaps with bassoon, though not necessarily a sixteen-foot string bass – acted as a counter-pole with a harmonic filler often supplied by long notes in the horns, doubled, with a dash of rhythmic activity, by the violas). While binary designs in the first movements of Italian opera overtures are still numerically in the minority (behind ritornello forms) by mid-century, such traits made no small impact on contemporary Viennese symphonists.

Contrast between two principal themes is particularly common in the work of the Italian-trained Georg Christoph Wagenseil, whose early career in Vienna was substantially as an operatic composer.4 Almost all of Wagenseil’s symphonies are in three movements, and the fact that many were published widely (both in France and England) shows that their appeal transcended the local circumstances of their production for the court of Maria Theresa. Among such works are his Six Simphonies a Quatre Parties Avec les Cors de Chasses Ad libitum . . . Oeuvre III . . . (Paris, c. 1760). At the foot of the title page is the comment ‘On vend les Cors de Chasses séparément’ – a token of the relative hierarchy within the orchestral texture that was to remain fundamental to the conception of the Viennese symphony for some years to come. Perhaps their popularity rested partly on their relatively slight, yet convincingly proportioned dimensions, especially in respect of thematic recapitulation, partly on the catchy and unpretentious minuet finales with which many conclude.

Wagenseil, court composer from 1739 until his death, was a crucial figure in the development of the symphony.5 He composed over seventy such works, the majority of which are in three movements: fast–slow–fast (typically a 3/8 time or 3/4 time minuet). In terms of formal organisation, he favoured full, rather than curtailed, recapitulations, allowing space for thematic and tonal contrast sometimes featuring subdominant recapitulations and digressions to the minor mode. That suggests a forward-looking mindset (along with his adoption of a galant idiom, especially within the central slow movements), which had consigned the undifferentiated surface and harmonic rhythms of baroque ritornello practice to the past. Ultimately, Wagenseil achieved a convincing level of segmentation within his movement forms that was to bear further fruit in the symphonies of later Viennese generations.

Wagenseil’s Viennese contemporary Georg Matthias Monn (1717–50) was perhaps less influential, both internationally and locally.6 None of his symphonies was published during his lifetime, though that is not a reflection of their general quality, which is comparable with Wagenseil, especially in the design of first movements, which frequently have two clearly defined and contrasting themes, a clear sense of periodic phrasing and tonal logic (including, as in Wagenseil, excursions to the minor mode) and full recapitulations. Monn’s first-movement forms arguably feature a more strongly defined developmental purpose to the material immediately following the central dominant or equivalent cadence than those of his contemporary. Monn is credited with composing the earliest-known four-movement symphony (in which the minuet comes in third place). This work in D major, dating from 1740, is however the only four-movement symphony in Monn’s surviving output of sixteen and although it survives in autograph, the designation ‘sinfonia’ is in a later hand. It must therefore be regarded as atypical, and while many of the emergent features of what may loosely be termed the ‘Viennese classical style’ are to be found in the symphonies of Monn and Wagenseil, the four-movement model apparently arose in Mannheim, where it was gradually established in the symphonies of Johann Stamitz between 1740 and 1750,7 works widely circulated in print across musical Europe and ultimately influential on Viennese composers too.

Developments

So far the contribution of what may be termed the ‘first-generation’ Viennese symphonists has been investigated through an assessment of constructional features, especially first movements, the organisation of which may be read in part as a record of advancing coordination in the handling of internal elements, and in part as a record of transmission of material between different genres (opera overture, but equally church sonata and partita, to symphony). That complex generic trace reflects something of the relationship of the composer with his material, either on a point-to-point scale or on a broader sweep of (usually three) successive movements. But whether constructional features such as the separation of thematic presentation into two contrasting aspects, or the coordination of thematic return with tonal return were dictated in any sense by the circumstances of their presentation in court, chamber or church we may doubt. At this stage in its development, performance settings for the Viennese symphony did not determine it compositionally to a strong degree. That is to say, for the earliest Viennese symphonists, no stable tradition of listening determined in advance their manipulation of musical materials as a response. By contrast, effects such as Haydn’s use of high horns in his Symphony No. 60, the shocking fortissimo chords in the Andante of the ‘Surprise’ Symphony, No. 94, Mozart’s theatrical late recapitulation of the opening theme (premier coup d’archet) in the first movement of the ‘Paris’ Symphony, K 297, Beethoven’s exhilarating recapitulation of the main theme over a dominant pedal in the first movement of the Symphony No. 7 – all of these are rhetorical elements of classical symphonic language and derive from usage in a concert situation in which rhetoric was expected by attentive listeners. In 1760 that was still not really the case. On the title page of Wagenseil’s Op. 3 symphonies of c. 1760 referred to above, the four (string) parts are sufficient on their own without the two horns, whose parts could be purchased separately and therefore optionally. Clearly in such a context the contribution of the horns is not so essential to the effect as it was some forty years later in the first-movement recapitulation of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony. Wagenseil’s musical materials do not exist in an essential relation with their representation in sound; in Beethoven’s they most assuredly do. That observation is an interesting marker of generic difference (and distance travelled).

What we may establish as generic traits of the symphony in Vienna by c. 1760 include:

1. A tendency to derive first-movement structures from binary form models, rather than ritornellos, usually involving at least two contrasting themes, both of which are recapitulated, and negligible ‘development’ of material immediately after the central double-bar.

2. An emerging recognition of the importance of key contrast and the vital role of cadential punctuation in achieving this; clear separation between different kinds of thematic functionality, contained within a steadily moving harmonic rhythm; symmetry and proportion as regulative elements of the structure, which operates in an interconnected way on the levels of local phrase, sentence and paragraph. Contrast, rather than uniformity, became a key element of coherence.

3. A succession of three (fast–slow–fast) rather than four movements, the third (final) movement often resembling a minuet: short, unpretentious and generally in binary form.

4. A presumed hierarchy of orchestral functions, in which winds are secondary to strings, and in which horn parts are often dispensable. At this stage, details that were soon to become relatively standard, such as the four-part string basis (the bass part comprising cello, string bass and potentially a bassoon), supplemented by a pair of oboes (or flutes), and a pair of horns, were still in flux; Wagenseil’s published symphonies include his Op. 2 (1756) entitled ‘trios en symphonie’ (i.e. trio-symphonies for two violins and bass).

At this point in its development, the Viennese symphony as a genre exists somewhere between internally conceived constructional boundaries on the one hand and a plethora of contrasting performance contexts on the other. The former are emerging into quite clear patterns. By contrast, the latter must surely have detracted from the establishment of a clear generic focus. There was, as yet, no single institutional context for its presentation, and what we may call the ‘practice of public reception’ counts for a lot in this regard. While the expressive rhetoric of the later Viennese symphony was significantly shaped in the concert hall, presentations of the works of Monn or Wagenseil and their contemporaries within courtly, and primarily social, contexts tended to diminish recognition of an independent generic value. For instance, in a performance of a symphony as a kind of background music at a Viennese banquet, any guests who were paying careful attention, however fleetingly, to the symphony would probably have related what they heard to their existing social experience of music, and the likeliest connection would have been with the opera overture. Thus, their reception perspective is not likely to have exerted any strong generic impetus upon symphonic development. Likewise, the performance of symphonies – for example, the four extant Sinfonie Pastorale of Leopold Hofmann (1738–93), or his small-scale B-flat symphony of c. 1763 (Badley B♭1)8 – within Catholic liturgical contexts (in which the focus is on the celebration of the Eucharist, to which, momentarily, the music is a background) will not have assisted the symphony’s generic separation from the church sonata, from which, in formal terms, Viennese symphonies trace some of their material ingredients. Moreover, performance practice impinges strongly on reception: surviving (usually single) sets of manuscript playing parts, for instance in monastery libraries, repeatedly hint that the numbers of strings involved in performances of symphonies in such contexts were small (sometimes even one to a part), suggesting that there was no strong distinction to be made between a symphony and other genres of predominantly string chamber music. For example, when he first joined the musical establishment at Esterhaza (1761), Haydn’s orchestral complement amounted to a total of thirteen to fifteen players: six violins, one viola, one cello, one bass, two oboes, two horns and a bassoon (some flexibility existed within this scheme, since most of the players could offer more than one instrument: a flute, for instance is employed in Symphony No. 6, Le Matin). Subsequently, during the 1770s, the size of the Esterhaza band increased, and there are documented performances of symphonies in Vienna by the Tonkünstlersocietät (founded 1771) with sizeable numbers of performers. But the link between the symphony genre and chamber music persisted remarkably long. At the end of the century, Haydn’s ‘London’ symphonies were subsequently issued in various chamber-music arrangements by Johann Peter Salomon (most popularly for flute, string quartet and piano ad libitum). The difference between this situation (in which Haydn’s symphonies could still be a chamber-music experience) and the looser generic situation of the 1750s was that these were clearly adaptations for domestic purposes of something originally experienced in a public concert setting and whose expressive parameters were decisively dictated by that original setting. In the case of the early Viennese symphony it is not so clear from the music that there was any or much difference between a domestic and any other imaginable forum of presentation in the first place.

All of this prompts the realisation that we must look elsewhere for reception stimuli impinging upon the development of the Viennese symphonic genre. Arguably, this is to be found in an examination of influence. The institutional framework for musical instruction in eighteenth-century Vienna revolved around the choir schools (for instance, at St Stephen’s Cathedral, or the Michaelerkirche) and, ultimately, it was centred on the personnel of the Hofkapelle. Among the more important connections are these: Fux (1660–1741) was Wagenseil’s teacher; in turn Wagenseil taught at least one member of a later generation of Viennese symphonists, Leopold Hofmann; Dittersdorf’s (1739–99) teacher was the Imperial Kapellmeister, Giuseppe Bonno (1711–88); Dittersdorf is said to have contributed to Johann Vaňhal’s (1739–1813) musical training after the latter had moved to Vienna in 1760–1; Josef Leopold Eybler (1765–1846) trained initially at St Stephen’s, and subsequently with Johann Georg Albrechtsberger (1736–1809), who had received his training in the choir school of the Augustinian monastery at Klosterneuburg and subsequently as a pupil of Monn; Albrechtsberger (revered by Mozart as an organist) became a colleague of Hofmann, succeeding him as Kapellmeister at St Stephen’s in 1793; his most famous pupil was Beethoven (from 1794, his previous teacher, Haydn, having left Vienna temporarily for his second London visit). In such a close-knit environment, it is understandable that the generic hallmarks of the Viennese symphony might to a large extent have been determined internally, in a progressive, influential dialogue between professionals working with the materials of their symphonic craft and defining the genre constructionally from within. That ongoing dialogue bore fruit in the increasing sophistication with which segmented formal functions within movements (especially first movements) are handled in the work of, for instance, Hofmann, Ordonez, Vaňhal and Dittersdorf. This ultimately led to a less casual relation between the different movements, in particular to a balanced conception in which the finale was regarded as providing a firm sense of closure to the three- (or four-) movement work, a kind of counterpole to the opening movement. As a result, the finale was now far less frequently in binary form, longer, and tending towards rondo structure, or, from the 1770s, sonata-rondo (in which sonata form maps onto the tonal logic of the refrains and episodes), and occasionally fugal types or even themes and variations.

Understanding this journey is not without its frustrations, principally because the surviving sources do not allow us to piece together a reliable chronology. Almost half of Leopold Hofmann’s fifty symphonies – a significant number of which may have been primarily intended for liturgical use, to judge from the quantity of sources surviving in monasteries such as Göttweig – have four (not three) movements; he was among the earliest of Viennese composers to adopt this expanded outline (though we should remember that some of these are in a slow–fast–slow–fast sequence and that others are effectively three-movement works with slow introductions).9 More contemporary sources survive for Hofmann’s symphonies than for any other composer of the era save Haydn and Pleyel (like those of his teacher, Wagenseil, Hofmann’s symphonies appeared in print in Paris; four were published there by Sieber in 1760, for example). But a chronology for his symphonies is not easy to establish with certainty, and it is not safe to assume that, for instance, his three-movement works were superseded by four-movement ones. Perhaps the innovatory aspect of a four-movement plan contributed to their popularity, but it is perhaps their sure command of texture and form that guaranteed their wide appeal. Concertante elements are occasionally found, for example in the F major symphony of c. 1760 (Badley F2), a three-movement work whose second-placed minuet features a central trio specifically for solo viola, cello and bass, contrasting with surrounding tuttis (strings and oboes). Similar concertante elements are found elsewhere within the emergent Viennese symphonic tradition, notably in Haydn’s slightly later programmatic set, Le Matin, Le Midi and Le Soir (c. 1761–2) and subsequently in such works as the Larghetto of Dittersdorf’s four-movement A minor Symphony (Grave a1, c. 1770–5),10 which features prominent cello solos along with punctuating interjections for a pair of horns, and the Adagio molto of Vaňhal’s D major Symphony (Bryan D17)11 of 1779 (in three, not four, movements), which may as well be the slow movement of an oboe concerto. Hofmann also preceded Haydn in the employment of a slow introduction to first movements, for example in the D major symphony of c. 1762 (Badley D4), in which the relatively lightweight and pithy character of the extremely economical Allegro molto is contextualised by a preceding Adagio of considerable gravitas. The main Allegro molto discriminates effectively between its primary, secondary, connective and cadential materials. Interestingly, there are quite clear resemblances between the second-movement Andante and the opening Adagio introduction. Interrelations between thematic elements is likewise a characteristic of the symphonies of Florian Leopold Gassmann (whose position as Imperial Kapellmeister Hofmann failed to secure on Gassmann’s death in 1774),12 though here the references are typically between the successive themes within an exposition in a quasi-organic succession as the tonal narrative away from the opening tonic unfolds.

For the Viennese symphony emergent between c. 1760 and 1780 (the period spanned by the production of symphonies by Dittersdorf and his contemporary, Vaňhal), growing confidence in the coordination and proportioning of theme, rhythm, harmony, tonality and texture contributes substantially to the impression of an overall trend towards a narrative whose unfolding features emerge as a logical succession of elements specifically designed to be noticed by listeners: Vaňhal’s C major Sinfonia Comista (Bryan C11, c. 1775–8) affords a clear example. In the concertante Larghetto of Dittersdorf’s A minor Symphony, mentioned above, repeating cadential refrains supplied by the two horns are not simply an attractive colouristic device, contrasting with the solo cello’s episodes, but are precisely coordinated with the arrival of moments of tonal articulation upon which the overall form depends. Both sound and structure are surely meant to be recognised by a listener; an element of meaning derives from dialogue between the abstract musical conception and a listener paying attention to it in real time. That listener would also have noted the currency of Dittersdorf’s opening Vivace (which employs three horns), which is firmly in the tempestuous Sturm-und-Drang idiom that was sweeping Viennese music in the early 1770s. Sturm und Drang is a feature too of some symphonies by Vaňhal from this period. His G minor Symphony (Bryan g1), published in Paris in 1773–4, but perhaps dating from the late 1760s, is a case in point. It makes prominent use of tone colour (notably two pairs of horns tuned in G and high B flat, and concertante parts for violin and viola in the second of its four movements, Andante cantabile) in addition to the expressive harmonic colours obtainable from the minor mode, its driving syncopations and sudden dramatic contrasts of dynamic, register, texture and accentuation, reminiscent in character of more famous symphonies in G minor by Haydn (Hob. I:39) and Mozart (K 183). Moreover, Vaňhal’s orchestration is pioneering. In a D minor Symphony (Bryan d2), one of five symphonies of his advertised for sale by Breitkopf in Supplement XII (1778) of their Thematic Catalogue, he uses no fewer than five horns (in two pairs, crooked in F and D, with an additional one in A), giving him a wide range of notes and once again allowing the horns’ full participation in the exploitation of expressive harmonic potential. And several symphonies (among them Bryan D17 and C11, mentioned above, and C3, D2 and A9) use pairs of clarino trumpets.

Conclusions

Vaňhal’s output marks an important point of arrival in the development of the Viennese symphony. His are works of considerable individuality, technically assured, inventive, substantial in length and also in intellectual concentration, requiring, indeed, a certain degree of concentration on the part of the listener if they are to be satisfactorily realised. His symphony Bryan D2 (c. 1763–5) has, in its first movement, a genuine development section, which introduces a new theme during its course. Symphony A9, of uncertain date, is a single-movement symphony in three sections (fast–slow–fast), though its dimensions and expressive range far exceed those of the Italian opera overtures that were once a prototype for the earlier Viennese symphony; its opening and closing sections include unmistakable cross-references, the Finale’s closing material returning to the opening bars of the work. The majority are in four movements, a scheme within which there is purposeful regard for the overall proportions, the finales sometimes being considerably extended and typically in rondo, sonata-rondo or sonata form. They may well have been known to Haydn (ten of Vaňhal’s symphonies are preserved in the Esterházy archives) and also to Mozart (who played chamber music with Vaňhal); certainly the 62-bar slow introduction (in the minor mode) to Vaňhal’s D major symphony (Bryan D17) has strong similarities both to the introduction of the ‘Linz’ Symphony, K 425 and to that of the ‘Prague’ Symphony, K 504.

While the symphonies of Vaňhal may, in sum, be claimed to represent a maturity in the development of the Viennese classical symphony that served as a platform from which were launched the final achievements of the genre’s four greatest exponents, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert, that claim requires substantial qualification. First, Vaňhal’s symphonies are exemplary of an achievement stemming from an environment of fairly loose, intertextual progress among Viennese composers generally towards mastery of technique allied to form, rather than the product of a single, paradigm-shifting individual. Secondly, an agenda of progress towards Haydn and Mozart, followed by Beethoven and Schubert and their lesser adjuncts, Czerny, Ries, Spohr, Cherubini, Gyrowetz, et al., is one whose motives (originating perhaps in a conflation of nineteenth-century political, aesthetic and especially nationalist debates) are highly questionable. Such debates redefined the symphonic genre in an act of retrospective Rezeptionsgeschichte that was bound up with the invention of a Viennese classical canon supported by institutions such as the professional concert, the complete edition, the founding of conservatoires, the discipline of musical Formenlehre and the rapid rise of serious musical criticism. As a consequence, the Viennese symphony at the turn of the nineteenth century assumed what would remain its destiny as the most prestigious among instrumental genres. Within this species of Rezeptionsgeschichte, the symphony was expected to be individual, to possess inherently dramatic qualities, to encapsulate in addition to mere technical control of its materials an aesthetic of progress beyond ‘absolute music’. In Beethoven’s symphonies, which played a pivotal role in launching the Viennese symphony into this exciting uncharted territory, the genre is once more redefined as a public demonstration – celebration, even – of topics such as the sublime (for example, the first movement of the Eroica, which at nearly 700 bars, is the longest symphonic movement Beethoven ever composed); of overarching unity in diversity, expressed cyclically in the Fifth Symphony through thematic transformation of theme, through the linking of different movements and, indeed, through the dissolution of boundaries separating movements, as the Scherzo gives way to the culminating finale; of ‘fate’ and ‘strife-to-victory’ (exemplified in some readings of the same symphony); of the naturalistic as a retreat from the dehumanising perspectives of war and industrialisation in the ‘Pastoral’ Symphony; and, in the Ninth’s Finale, the transformation of the genre through the medium of the human voice singing of an imagined redemption attainable only beyond the material realm.13 Poetic ideas, to be sure; and such was now expected of the symphony. Crucially, the baritone addresses the audience as ‘Friends’, directly inviting their involvement, for it is within that shared framework of endeavour that Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony must have its meaning if all men are to be brothers, rejecting past agendas (as Beethoven, metaphorically, has just rejected his previous themes in turn) and striding confidently forth into joy. This moment is a turning point in the symphonic genre; the symphony as civic agency has remained a powerful reception metaphor ever since (this event is considered below in chapters 8 and 9).

One casualty of this historiographical agenda was Schubert, whose symphonies were eclipsed throughout the nineteenth century and beyond by the mighty achievement of his idol, Beethoven. Like Beethoven’s nine symphonies, Schubert’s eight travel a path away from late eighteenth-century classical purity, symmetry and elegance towards the frontier of transcendence articulated in the writings of the German Romantics, Wackenroder, Tieck, E. T. A. Hoffmann and the Schlegels. But Schubert’s ‘Beyond’ arguably lay deep within himself. His ‘Unfinished’ and ‘Great’ C major symphonies conform uneasily to early nineteenth-century expectations of the symphonic genre, and this may be a contributory cause to their painfully slow acceptance into the canon (they were only even premiered in 1839 and 1865 respectively), for they trace a path not towards the attainment of a public and civic spiritual brotherhood of all mankind, but a private and interior world of half-lights and self-doubts whose technical musical language is often not far removed from the lied. While there are no voices in Schubert’s symphonies, the vocality of his personal symphonic genre is unmistakable. In his hands, as in Beethoven’s, the Viennese symphony had travelled far.

Notes

1 For Mozart’s letter, see , ed., The Letters of Mozart and His Family, 3rd rev. edn, ed. and (London and Basingstoke, 1985), no. 396. See also , Mozart: A Documentary Biography, trans. , and (London, 1990), , Mozart: the Golden Years (London, 1989) and , Mozart: The ‘Jupiter’ Symphony (Cambridge, 1993).

2 For an overview of life and society in Hapsburg Vienna, seen against the backdrop of the Enlightenment, see , Enlightenment and Reform in Eighteenth-Century Europe (London and New York, 2005). The musical picture is painted in , Haydn, Mozart and the Viennese School 1740–1780 (New York and London, 1995).

3 See, for instance, and , eds., Concert Life in Eighteenth-CenturyBritain (Aldershot, 2004) and , Concert Life in Haydn’s Vienna: Aspects of a Developing Musical and Social Tradition (Stuyvesant:, 1989).

4 Eighteenth-century sources of Wagenseil’s symphonies survive in numerous locations, among them the Bibliothèque du Conservatoire, Brussels, the Národní Muzeum, Prague, the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde and Nationalbibliothek, Vienna and the Library of Congress, Washington DC.

5 See John Kucaba, ‘The Symphonies of Georg Christoph Wagenseil’ (Ph.D. diss., University of Boston, Reference Kucaba1967). Subsequent references to Wagenseil’s symphonies draw on the editions ed. in , gen. ed., The Symphony, 1720–1840, Series B, vol. III: Georg Christoph Wagenseil: Fifteen Symphonies, D1, D9, C8, C3, C4, G1, E♭2, C7, F1, B♭2, D2, G2, G3, E3, B♭4 (New York and London, 1981).

6 See Kenneth E. Rudolf, ‘The Symphonies of Georg Mathias Monn (1715–1750)’ (Ph.D. diss., University of Washington, Reference Rudolf1982). Works consulted can be found in , gen. ed., The Symphony, 1720–1840, Series B, vol. I: Georg Matthias Monn: Five Symphonies, Thematic Index D-5, E♭-1, A-2, B♭-1, B♭-2 (New York and London, 1985).

7 , The Symphonies of Johann Stamitz: A Study in the Formation of the Classic Style (Utrecht, 1981).

8 Numbers for Hofmann’s symphonies throughout refer to Artaria Editions AE022, 24 and 26, ed. Alan Badley (Wellington, 1995). On Hofmann’s symphonies, see G. C. Kimball, ‘The Symphonies of Leopold Hofmann (1738–1793)’ (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, Reference Kimball1985).

9 A handful of the seventy symphonies of Karl von Ordonez (1734–86) are in four movements, and very occasionally there are slow introductions; see D. Young, ‘The Symphonies of Karl von Ordonez (1734–1786)’ (Ph.D. diss., University of Liverpool, Reference Young1980). For editions of Ordonez’s symphonies, see Barry S. Brook, gen. ed., The Symphony, 1720–1840, Series B, vol. IV: Carlos d’Ordoñez: Seven Symphonies, C1, F11, A8, C9, C14 minor, G1, B♭ 4, ed. with the assistance of (New York and London, 1979).

10 Editions of Dittersdorf’s symphonies consulted are Dittersdorf a1 (k95), ed. , Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Österreich, lxxxi, Jg.xliii/2 (Vienna, 1936) and also , gen. ed., The Symphony, 1720–1840, Series B, vol. I: Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Six Symphonies, Thematic Index e1, E♭3, E2, A10, D9, C14, ed. , thematic index by (New York and London, 1985). On Dittersdorf’s symphonies, see also Margaret H. Grave, ‘Dittersdorf’s First-Movement Form as a Measure of his Symphonic Development’ (Ph.D. diss., New York University, Reference Grave1977).

11 Editions of Vaňhal’s symphonies consulted are: Vaňhal g1, ed. , Diletto musicale38 (Vienna and Munich, 1965); Vaňhal C11, ed. Alan Badley (Wellington, 1996); Vaňhal d2, ed. Alan Badley (Wellington, 1996); Vaňhal C3, ed. Alan Badley (Wellington, 1997); Vaňhal A9, ed. Alan Badley (Wellington, 1997); Vaňhal D2, ed. Alan Badley (Wellington, 1998). On Vaňhal’s symphonies, see , Johann Wanhal, Viennese Symphonist: His Life, and His Musical Environment (Stuyvesant:,1997).

12 See George R. Hill, ‘The Concert Symphonies of Florian Leopold Gassmann (1729–1774)’ (Ph.D. diss., New York University, Reference Hill1975). Editions of Gassmann’s symphonies can be found in , gen. ed., The Symphony, 1720–1840, Series B, vol. X: Florian Leopold Gassmann: Seven Symphonies: 23, 26, 62, 64, 85, 86, 120, ed. (New York and London:, 1981).

13 See, in this respect, , Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 (Cambridge, 1993).

3 Other classical repertories

It is symptomatic of our perception of the eighteenth-century symphony that this part of the volume has been divided into ‘The Viennese Symphony 1750 to 1827’ and ‘Other Classical Repertories’, a division that reflects our preoccupation with the path the eighteenth-century symphony took en route to Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. Although no one will quarrel with the Viennese trinity’s pre-eminence as symphony composers, the focus on their roots and influences has done scant justice to the symphonic cornucopia that the century produced.1Estimates of the number of symphonies composed during the century range up to 20,000, and even a brief sampling reveals an almost bewildering variety of formats (from one up to seven or more movements), textures (ranging from fugal to completely homophonic), orchestration (from three-part strings on up) and formal procedures. Moreover, we have mostly paid attention to the ‘concert symphony’, a designation not used until the late eighteenth century, and have tended to define the ‘real’ or ‘mature’ symphony as a serious, four-movement work for an orchestra of strings and winds, a definition that excludes or marginalises much of the repertoire. This repertoire reflects the eighteenth century’s conception of the symphony as an instrumental work that could be used in the theatre (to precede an opera), in church (as Gradual music in the Catholic mass, for example), or in the chamber, where it generally served to open a concert. Although certain characteristics were typically associated with particular functions (i.e. forte, tutti openings for opera sinfonie), the fact remains that opera sinfonie frequently appeared in concerts, and ‘chamber’ symphonies (or movements of them) often served as Gradual music. For the eighteenth century, a sinfonia was a sinfonia, so if we wish to explore the genre fully, we would do well to consider all of its manifestations.2

What follows might be described as a ‘socialist’ history of the symphony. It identifies no ‘major figures’; it does not trace influence or connections; it does not chronicle innovations or attempt to identify who did what first. Instead, it views symphonic composition as a collective enterprise in which thousands of composers participated; by taking this approach, I hope to expand the slender standard narrative thread into a complex tapestry of colours and patterns. Because of space limitations I have narrowed my focus and have concentrated on form, structure and expression, and the ways they interact with texture and orchestration.3 I do not claim that my narrative is better than the standard one; merely that it shows us different things and perhaps makes us ask different questions.

Regions of composition

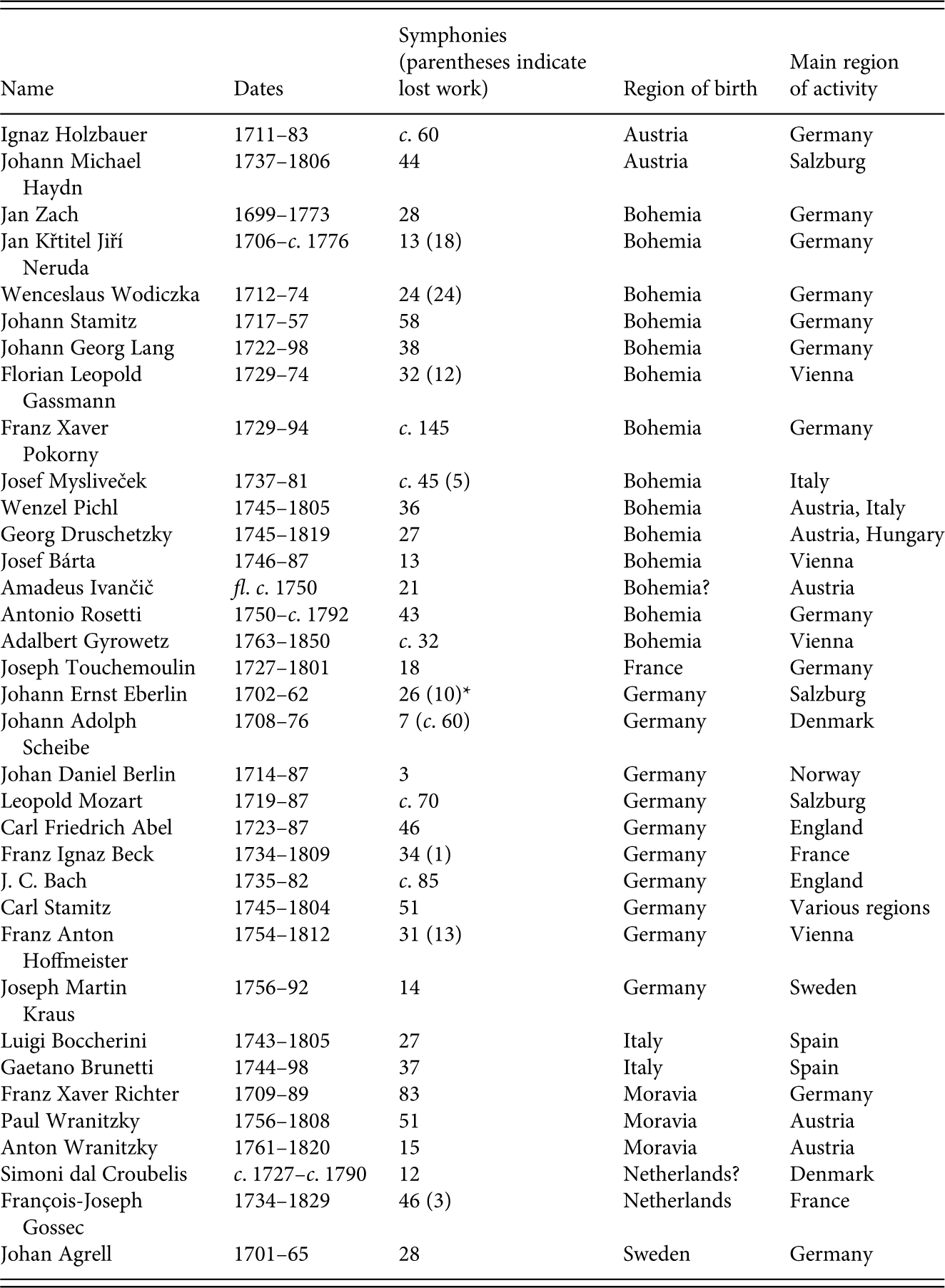

The symphony was found all over Europe as well as in lands where European culture was imported, and the composers themselves were a peripatetic lot. Italians and Bohemians, and to a lesser extent musicians from the German states, could be found everywhere (see Table 3.1). Luigi Boccherini (1742–1805) and Gaetano Brunetti (1744–98) both abandoned their native Italy for service in Spain; the Bohemian Josef Mysliveček (1737–81) spent much of his career in Italy; and his compatriot Johann Stamitz (1717–57) established his reputation in the palatinate of Mannheim, in southern Germany. The Mannheim-born Franz Beck (1734–1809) was active in France; the Swedish-born Johan Agrell (1701–65) in Kassel and Nuremberg; and the Scotsman Alexander Reinagle (1756–1809), of Austrian descent, immigrated to Philadelphia, in the newly formed United States. Such travels make a narrowly focussed study of ethnic or regional characteristics in symphonic composition tricky and perhaps of questionable value, although some differences in regional preferences and patterns of cultivation can be identified.

It is useful to distinguish between the composition and the cultivation of the symphony. For most of the century, composition was done by resident composers at courts or aristocratic households and thus occurred in relatively few places. These composers wrote for a specific orchestra and often for a specific occasion, even though their symphonies might later travel to other places in manuscript copies or in prints (often pirated). Cultivation was done by the thousands of institutions (including courts with resident composers) who purchased or otherwise acquired symphonies for performance at their concerts or celebrations or theatres or church services. These places created the demand that sparked the century’s symphonic fecundity. In the early part of the century, most symphonies were distributed in manuscript parts, often acquired during the course of travel. After the middle of the century, distribution channels increasingly ran through music publishers and music sellers, most of whom offered both manuscript and printed parts and were eager to sell works that would have a wide market, a point to which I shall return later.

Table 3.1 Selected immigrant composers of symphonies

In Italy, the opera sinfonia – generally in three movements until the one-movement form emerged in the late 1770s – remained a major outlet for Italian symphonic creativity for most of the century. Opera sinfonie by composers like Niccolò Jommelli (1714–74) can be found in eighteenth-century symphony collections throughout the continent. The three-movement form, well established by the 1730s, favoured first movements with a noisy primary theme using tutti strings and winds leading to transitions with tremolos and crescendos, quieter contrasting second themes and bustling closing sections. The melody-based slow movements, often in the parallel minor, gave way to quick and lively finales, frequently in triple meter. The ceremonial function of the opera sinfonia meant that it was not – and indeed should not – be tied to the operatic subject (something never understood or acknowledged by eighteenth-century German writers), an approach that meant it could easily be transferred to the chamber, or even to the church. Early Italian sinfonie originally intended for chamber or church settings tended to call for three- or four-part strings and boasted a more flexible texture and structure than the opera sinfonia. During the 1740s and 1750s, wind parts became more common in chamber symphonies: nearly one third of Giovanni Battista Sammartini’s (1700/01–75) sixty-eight symphonies, many from before 1760, add two horns or trumpets to the string choir.4 Although Italian composers wrote for larger ensembles as the century progressed, wind instruments do not appear to have played as significant a role in Italy as they did in Northern Europe, perhaps because the instruments themselves were harder to find.5The imaginative use of the winds by the Italian emigrants Gaetano Brunetti and Luigi Boccherini clearly demonstrates that with the proper resources, Italians could easily hold their own in the area of orchestration.

The impact of Italian symphonies was widely felt, particularly in the first half of the century. In the lands of the Hapsburg monarchy, the impact was both direct – with the presence in Vienna of figures like Bartolomeo Conti (1682–1732), Antonio Caldara (c. 1670–1736) and later Antonio Salieri (1750–1825) – and indirect (with the importation of Sammartini’s symphonies by the Count Harrach and the acquisition of Italian symphonies by the Esterházy family, documented in the Esterházy catalogues from 1740 and 1759–62).6Outside of Vienna, the symphony was composed and cultivated not only in cities like Pressburg and Prague, but also on the private estates of the nobility and in the numerous monasteries and convents. During the first half of the century, a strong fugal tradition threaded through Austrian symphonic composition and the liking for counterpoint never completely died out, although increasingly it was incorporated into a more homophonic style. As early as the 1760s, Austrian composers chose three- and four-movement formats with about the same frequency, but later turned to the four-movement F–S–M/T–F format with a sustained intensity not found in other regions of Europe. Perhaps because of the strong Bohemian wind tradition, works for strings alone were in the minority – even in the early part of the century – and disappeared almost entirely from the 1760s.

Much of the symphonic composition in southern Germany stemmed from its courts – the efforts of Johan Agrell in the free city of Nuremberg notwithstanding – particularly those in Mannheim, Wallerstein, Munich, Mainz, Trier and Cologne. Their musical establishments not only employed local composers, but also absorbed a whole flotilla of Bohemians, including Johann Stamitz (1717–57) and Antonio Rosetti (c. 1750–92), both known for their imaginative and varied use of the wind instruments. Stamitz and his colleagues in Mannheim made effective use of Italian techniques – including string tremolos and crescendos – using winds both for sonic and harmonic reinforcement and for melody. Rosetti had a particular knack for orchestration, often enriching the string texture by dividing the violas and using the winds with delicacy and finesse. Both composers had access to excellent orchestras (at the courts in Mannheim and Wallerstein, respectively), a fact that no doubt helped to stimulate their orchestral imaginations. (As Niccolò Jommelli observed, if you have a good orchestra, you must keep them busy or they will start to give you trouble.) The later Mannheim composers, for example Christian Cannabich (1731–98), Carl Joseph Toeschi (1731–88) and Franz Fränzl (1736–1811), have sometimes been accused of merely dabbling in colourful orchestral effects, but such comments belie the importance of such effects. In fact, particularly with composers like Rosetti, the skilful use of the orchestra to delineate structural function and create tension often goes hand in hand with the simple delight in the play of sonorities.

In northern Germany, the courts and aristocratic patrons sponsored most symphonic composition, although free cities like Hamburg and Leipzig certainly contributed to publication and performance. The Italian opera sinfonia had its effect here as well, but the north-German repertoire, particularly in the first two thirds of the century, showed great diversity in terms of movement structure. In the 1730s and 1740s Johann Gottlob Harrer (1703–55) composed a number of three-movement quasi-programmatic symphonies (some with large wind sections) intended for specific occasions, weaving hunting calls and well-known dance tunes into a mostly homophonic compositional fabric. At the court of Hessen-Darmstadt, Johann Christoph Graupner (1683–1760) and Johann Samuel Endler (1694–1762) showed a preference for symphonies with four or more movements (such large-scale works make up nearly half of Graupner’s 113 symphonies), often with very large ensembles sometimes requiring three trumpets.7 Much of the symphonic activity here appears to have taken place in the first part of the century, with the rate of production dropping sharply after around 1770.

France and Britain had more in common with each other than with the rest of Europe in terms of the cultivation of the symphony. For both, the centre of symphony composition, performance and publication was in their capital cities, though their smaller cities could also boast of musical societies that required symphonies for concerts. In the first two thirds of the century, the sheer number of music publishers in Paris and London completely dwarfed that of all competing cities except, perhaps, for Amsterdam. Paris and London also had a flourishing concert life – both public and private – and eagerly welcomed musical immigrants into their midst. Native composers like Simon Le Duc (1742–77) and the French-speaking immigrant from the Netherlands François-Joseph Gossec (1734–1829) grafted the metric patterns of the French language onto the Italian opera sinfonia style to create symphonic ‘Frenchness’. In the later part of the century, French composers showed a definite preference for the grand and brilliant, particularly with regard to orchestration.8 British taste favoured tuneful, diatonic melodies with lively dance-like rhythms,9 but audiences were also not unmindful of the charms of well-placed counterpoint, preferences that help to explain the popularity of the immigrant J. C. Bach (1735–82) and the adulation that greeted the symphonies of Joseph Haydn.

Areas on the geographical periphery of Europe and those on other continents participated in both the composition and the cultivation of symphonies, though the latter was more frequent than the former. Even if immigrant composers dominated the compositional scene (as did Luigi Boccherini and Gaetano Brunetti in Spain), native-born talents also participated (as with the group of Catelonian composers active around Barcelona after about 1770).10 Lands with music-loving monarchs and established musical institutions, such as Sweden, produced their own local symphony composers even early in the century – for example Johan Helmich Roman (1694–1758) and Johan Agrell – but other places, particularly in the colonial world, did so only towards the century’s close. Immigrant composers completely dominated the musical world of the North-American colonies and the young United States; in South America, the only known symphony by a native-born Brazilian, for example, was written by José Maurício Nunes Garcia (1767–1830) in 1790.11

Symphonic style and form

Any attempt to describe general (as opposed to composer-specific) patterns and trends in eighteenth-century symphonic composition is in some ways a foolhardy undertaking, given the number of works involved and the fact that so many of them have never been studied. What follows can thus not be considered definitive, but is offered as a possible narrative framework for understanding and interpreting the symphonic data that we do have. Briefly stated, the first half of the century witnessed a variety of approaches – on every level of composition – to works labelled ‘symphony’. Although a few patterns can be identified, particularly locally, the differences in everything from number of movements to texture to formal procedures were considerable. By the end of the 1750s, recognisable patterns and conventions common across all the regions of composition had begun to coalesce, giving the genre a more definite shape. These conventions proved advantageous both to composers and listeners; the best composers were those who could exploit them by playing on the expectations they created. Whereas we have tended to view conventional patterns as straight-jackets for the imagination (a sign of our continuing attachment to nineteenth-century aesthetic values), for eighteenth-century composers they appear to have functioned as a stimulus, providing a basic framework upon which they could construct endless delightful and subtle variations.

Early eighteenth-century approaches

From the beginning, most composers chose the three-movement, F–S–F format commonly found in the Italian opera sinfonia for the overwhelming majority of their works, although one- and two-movement works remained a strong second choice. (It should be noted that many of the latter had two-tempo movements, so that they could also be heard as having three or four connected movements.) Four-movement symphonies were less common before the 1750s and can be found in a variety of patterns (not just F–S–M/T–F), as seen in the sampling given in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2 Examples of four-movement plans before 1760

North-German composers, as indicated above, had a particular fondness for works in four or more movements, sometimes with programmatic titles. Graupner’s Symphony in E flat (Nagel 64 from c. 1747–50) features five quick movements: Vivace, Poco Allegro, Allegro, Poco Allegro, Tempo di Gavotte. Endler’s Symphony in E flat (E♭4 from 1757) has both dance and programmatic components: Allegro molto; Menuet I and II, Marche, Contentement, Bourrée I and II, Le bon vivant I and II. For interior slow movements, composers seem to have preferred the tonic or relative minor – a choice that maintained tonal unity and was potentially less jarring to the sensibilities when the movements were very brief – but occasionally chose the subdominant or dominant.

During this period, strings in an a 3 (two violins and basso) or a 4 (two violins, viola and basso) configuration formed the core of performance forces, although a 3 works became rarer by the 1740s. When available, wind instruments (most commonly horns, oboes or trumpets) could join this core string group, particularly in Italian opera sinfonie and for ceremonial occasions at court or in church. For example, the Symphony in C by Georg Reutter the Younger (1708–72) calls for a 4 strings, organ and two brass choirs, each with two clarini, two trombe and timpani.12 Endler’s Symphony in D (D4), written for a New Year’s Day celebration in 1750, requires a 3 strings, oboe, two horns, three clarini and timpani. The use of winds in more ordinary circumstances increased gradually throughout the period, although instrumentation often remained flexible: the title page of Jean-Férry Rebel’s 1737 Symphony, Les eléments, announces that ‘This symphony is engraved in such a way that it can be played in concert by two violins, two flutes, and one bass’, adding that a harpsichord could also play it alone. Moreover, the score itself indicates a number of places where other instruments – specifically two violas, basso continuo, piccolos (petites flutes), oboes, horns and bassoons – could be added.13 Although Rebel’s work is unusual in the extent of its suggested alternatives, flexibility with regard to wind parts was widespread. Published works often had ad libitum wind parts to make them more marketable and – conversely – trumpet or horn parts could be added to make a work more festive or to cater for a patron’s wishes.14

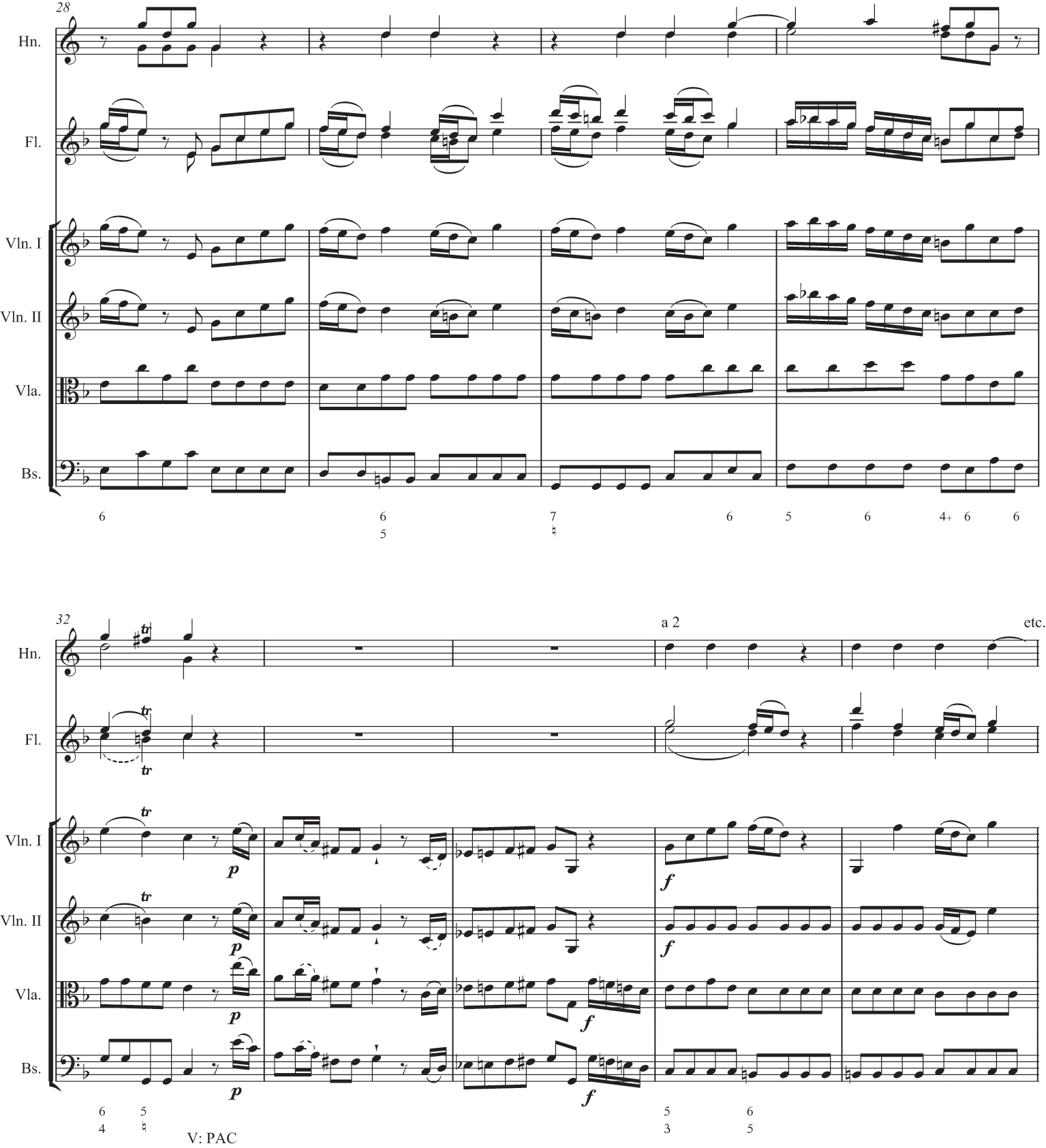

Although wind instruments in this repertoire tend to play either colla parte with the strings or to reinforce the harmony, we should not discount the effect that they had on the listener’s sonic experience. Moreover, composers often highlighted the wind instruments or used them in a more subtle interplay. In Johann David Heinichen’s (1683–1729) Symphony in D (written after 1717), pairs of flutes and oboes play colla parte with the strings, but the two horns have occasional solos. Agrell’s woodwinds usually play colla parte with the strings, but in his Symphony in C major (from the early 1740s), he makes sophisticated use of their penetrating sonority, with the oboes reinforcing the syncopated harmonic shifts made by the strings and the horns entering in alternation with punctuation that drives to the downbeat (Example 3.1). Rightly known for his imaginative orchestral effects, Johann Stamitz frequently used winds as solo instruments in secondary themes, temporarily relegating the normally dominant strings to an accompaniment role. During this period, wind instruments often dropped out for middle slow movements, thus creating a sonic contrast with the surrounding tutti fast ones, although sometimes, as in Giovanni Battista Lampugnani’s (c. 1708–c. 1788) Symphony in D (D6, c. 1750) and some of Graupner’s early works, the horns continue the harmonic supporting role evident in the outer movements.

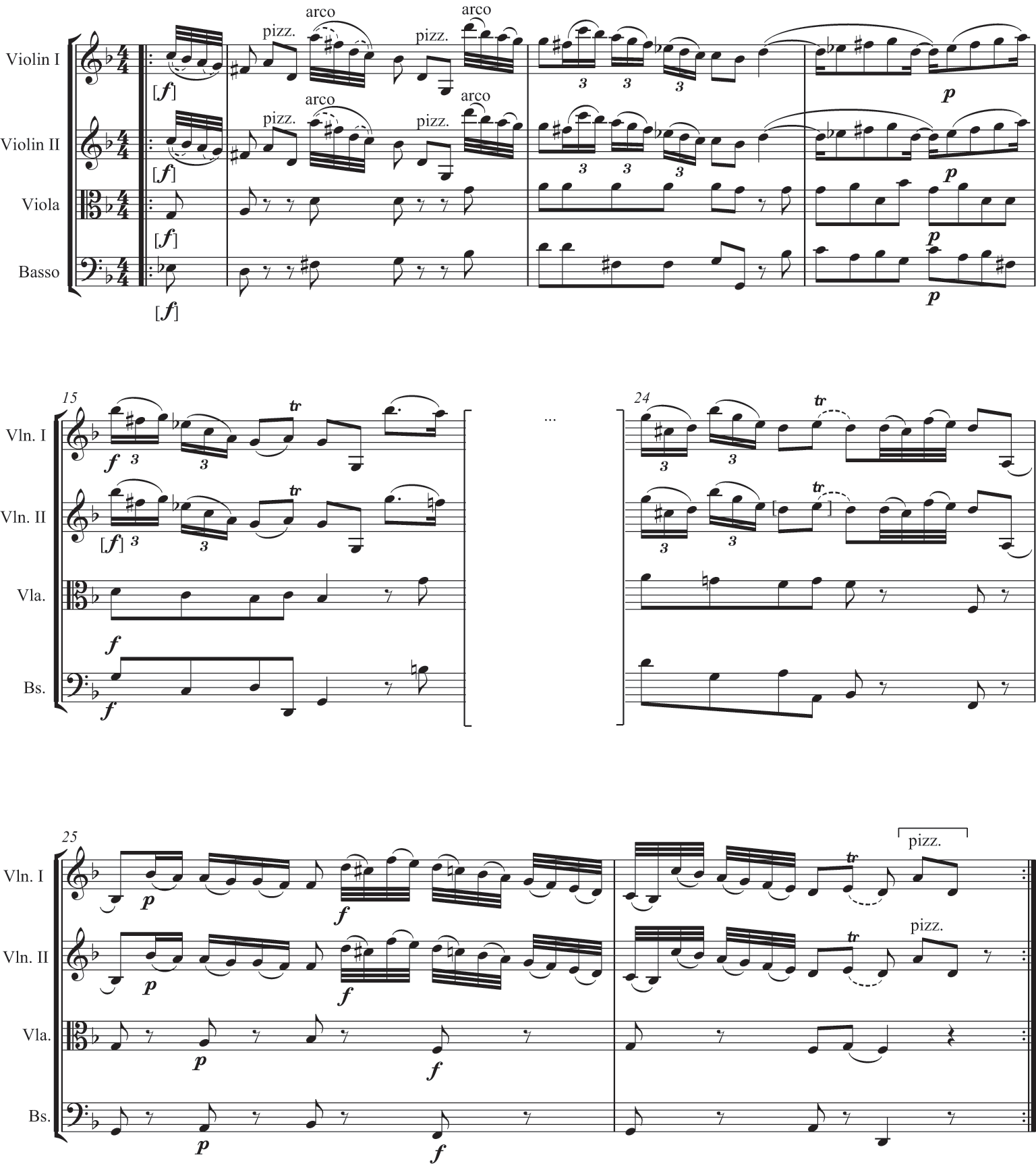

Example 3.1 Johan Agrell, Symphony in C major, I, bars 15–23.

Early symphonies exploited a wide variety of textures, from strictly fugal to essentially contrapuntal to purely homophonic. The preference for fugues in instrumental composition has been associated with Vienna; however the technique can be found across the continent. The Swedish composer Ferdinand Zellbell, Jr (1719–80) opened his D minor Symphony with a first movement slow introduction leading to a fugue followed by a sarabande and gigue, and several composers in England – Francesco Barsanti (1690–1772), Thomas Arne (1710–88), Maurice Green (1696–1755) – incorporated fugal movements in their symphonies from the 1740s and 1750s. (Interestingly, Padre Giovanni Battista Martini (1706–84), famous all over Europe for his counterpoint treatise, did not include any fugal movements in his twenty-four symphonies.) Although arrangements like Zellbell’s follow the pattern of the French overture and suite, with slow dotted openings leading to fugues followed by dance movements, not all fugal movements fall into that category: Wenzel Birck’s (1718–63) Sinfonia No. 9 has a 107-bar Presto before its fugue,15and most of Franz Xaver Richter’s (1709–89) symphonic fugues appear in finales.16 Even in the early part of the century, fugues and fugal textures appear in only a tiny fraction of all symphony movements; I have considered them at some length here because their persistent presence in the repertoire helps to explain the continuing importance of counterpoint in later eighteenth-century works.

The predominant symphonic texture was of course homophony, both in the unison/massed sound and the melody-with-accompaniment varieties. Throughout the first half of the century, however, composers consistently mixed a soupçon of counterpoint into their symphonies, often to articulate structural functions. Antonio Brioschi (fl. c. 1725–c. 1750) commonly turned contrapuntal in his development sections, while Sammartini often used contrapuntal transitions that contrast with the unison or homophonic primary and closing sections. By way of contrast, Agrell often distinguished his secondary themes by introducing counterpoint, along with reduced orchestration and dynamics. These examples show that fugal and contrapuntal techniques were quickly absorbed into the newer formal procedures that began to dot the symphonic landscape.

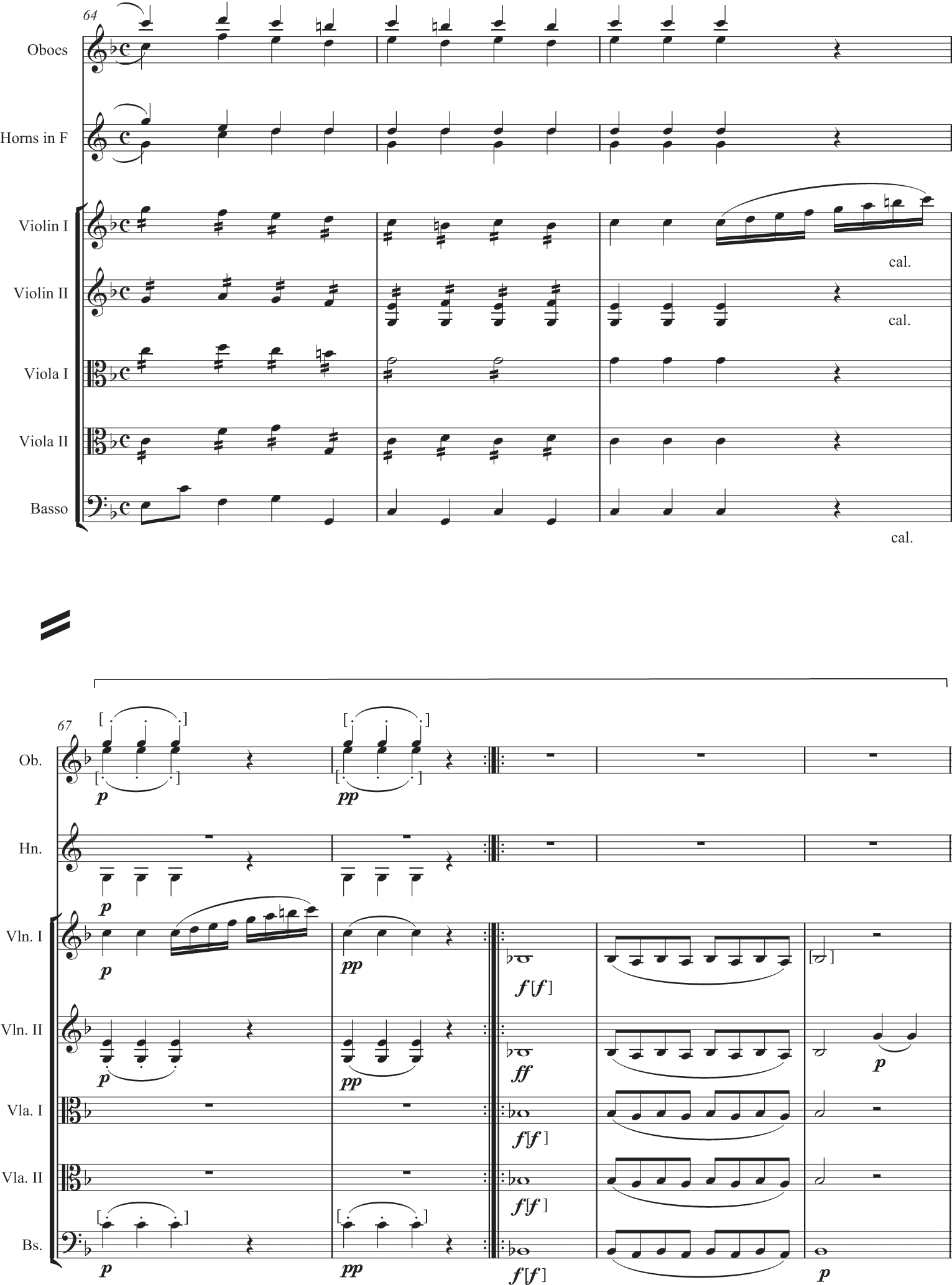

In terms of formal structure, most early first movements fell somewhere along the continuum of binary to sonata forms (mostly the latter), but some are ritornello-based and others blend aspects of ritornello and sonata construction. Slow movements and other fast movements rarely made use of ritornello techniques and mostly fall towards the binary end of the continuum. Conventions for delineating the sections of sonata movements were just beginning to emerge, but the first three basic sonata types described by James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy for the later eighteenth century can easily be identified in this repertoire as well.17 In general, composers of this period were establishing the rules of the game (à la Leonard Meyer) with great vitality and spirit, exploring possibilities for generating tension and excitement (tremolos, crescendos, rising lines, etc.) and for expressivity.18 Often, the expressive centre of the work was in the (frequently) minor-mode slow movement, which habitually featured nuanced dynamic contrast, sighing appoggiaturas and cantabile melodies. Georg Benda (1722–95) makes the most of the sonic possibilities of the strings in the slow movement his Sinfonia I in F major by juxtaposing pizzicato and arco motives, ending with a delightfully quizzical pizzicato weak-beat afterthought (Example 3.2).19

Example 3.2 Georg Benda, Sinfonia No. 1 in F major, I, bars 12–15; 24–6.

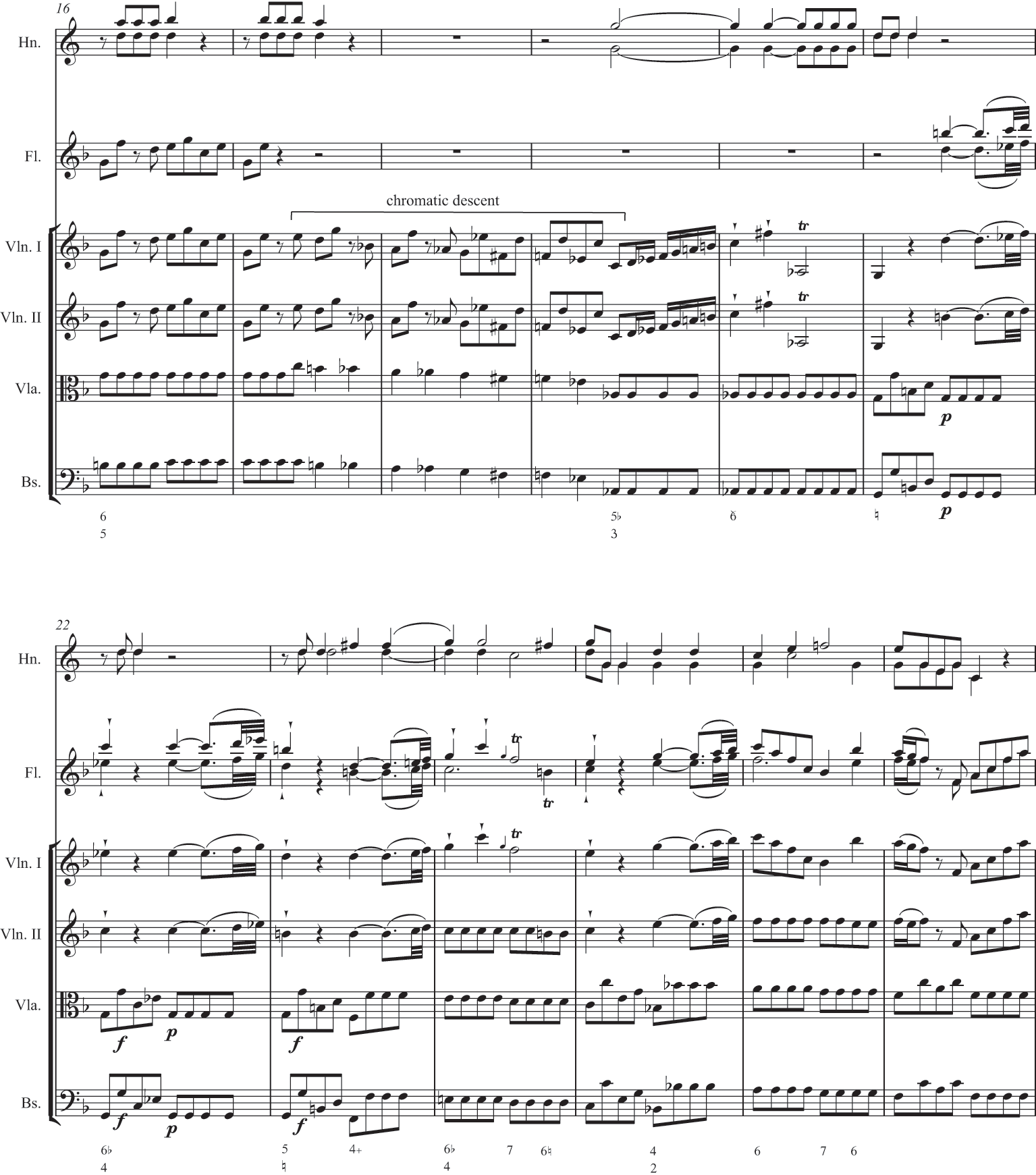

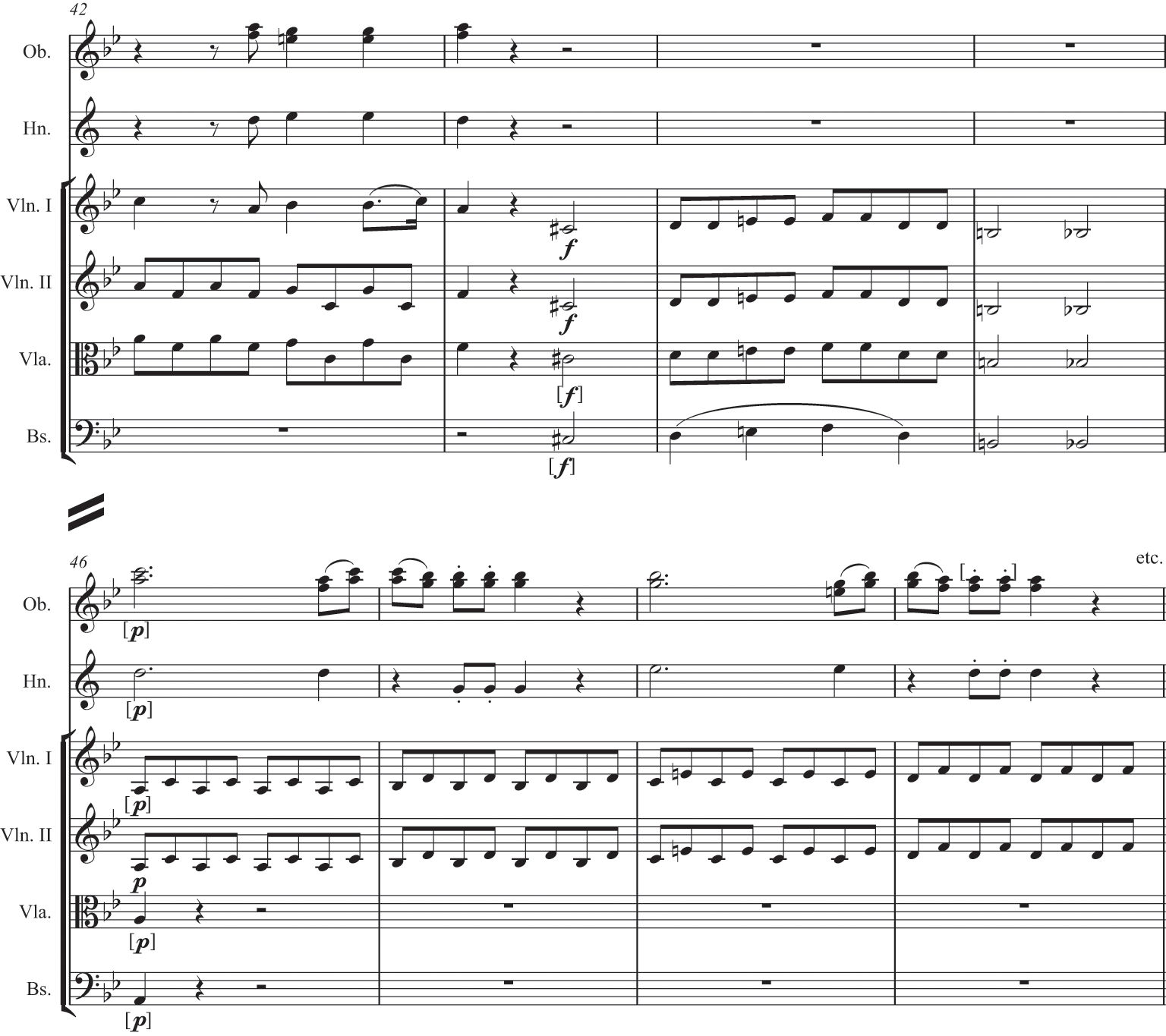

Expressive choices, however, were not limited to the slow movement. Opening major-mode movements often featured diversions to the minor dominant in S (the subordinate theme), a tactic particularly popular in Italian opera sinfonie of the 1730s as seen in Leonardo Leo’s Amor vuol sofferenza from 1736 (Example 3.3a and b). Similar techniques are employed by such diverse composers as Agrell, Harrer, Leopold Mozart (1719–87) and Georg Wagenseil (1715–77). The long primary section of Sammartini’s Symphony No. 10 in F major even encompasses a plaintive contrasting section in the tonic minor. Development sections frequently traverse minor-mode areas, often with a strong cadence to the relative minor just before the recapitulation. In many cases, this expressivity relies on local-level contrast, nowhere more strongly than in the symphonies of C. P. E. Bach (1714–88). In his Symphony in F of 1755 (Wq 175) rests, chromatic excursions and dynamic contrasts enhanced by changes of orchestration all combine to create local-level drama and structural-level tension. The piano trills in bar 7 give way in the next measure to a minor-mode variant of bar 6, which is followed by a forte outburst on V7/V to begin the transition. Its path to V, however, is continually derailed by further chromatic diversions and piano interpolations, delaying the cadence in the dominant until bar 32 (Example 3.4).

Example 3.3a Leonardo Leo, Overture to Amor vuol sofferenza, I, bars 1–5.

Example 3.3b Leonardo Leo, Overture to Amor vuol sofferenza, I, bars 12–17.

Example 3.4 C. P. E. Bach, Symphony in F major, Wq 175, I, bars 1–36.

Bach’s symphonies, like many others from the first part of the century, derive their energy from such local-level contrasts, together with lively and engaging motives, a consistent quaver pulse and a forward trajectory that minimises sectional and functional delineation. Such techniques, particularly when used skilfully, work very well in shorter movements; for more extended compositions, other organisational strategies needed to be devised. Many of the formal conventions we associate with sonata form emerged as composers began to incorporate these local contrasts into a larger compositional trajectory in which the various sections of the movement assumed particular functional responsibilities. The trajectory was created in large part by the creation of expectations, which could then be fulfilled, deflected, or even subverted. This approach became the defining feature of late eighteenth-century symphonic style.

Late eighteenth-century conventions

By the 1760s, conventional practices in all elements of symphonic composition had coalesced into patterns discernible throughout the European continent. The three-movement F–S–F pattern continued as the most common movement format, with the four-movement scheme (mostly, though not always, F–S–M/T–F) the strong second choice. Only at the very end of the century did the F–S–M/T–F format start to dominate, and even then some composers who had flirted with the four-movement pattern early in their careers chose the three-movement variety in their later works, among them Cannabich, Toeschi and Ignaz Pleyel (1757–1831). Rather than seeing their choice as a ‘reversion’ to an outdated practice (as has generally been the case), we might more profitably ask what advantages or disadvantages the two options might have had. Composers like Joseph Haydn took advantage of the minuet’s compact and absolutely predictable form to stretch and play with musical parameters like rhythm and texture. For others, the inclusion of the minuet might simply have expanded the symphony beyond a usable length, especially given the increasing length and complexity of the other movements (something that probably explains the nearly complete disappearance of symphonies in more than four movements). One- and two-movement symphonies still maintained a presence in the repertoire in France, the Austrian lands and especially in Italy, where they continued to be of importance in church settings. For example, twenty-four of the Franciscan priest Stanislao Mattei’s (1750–1825) twenty-seven symphonies are single-movement works intended for church performances in Bologna.20

In the area of orchestration, the a 8 configuration (a 4 strings plus two oboes and two horns) emerged as the overwhelming favourite. This particular convention may well have been driven by market forces: music publishers and dealers clearly preferred symphonies with instrumental requirements that most ensembles could cover. Although strings-only symphonies continued to appear well into the second half of the century, by the 1790s the theorist Heinrich Christoph Koch could state that audiences generally expected to hear winds in symphonies.21 Works requiring large wind ensembles still tended to come from courts with substantial orchestras (e.g. Mannheim and Wallerstein), and some evidence suggests that such large-scale pieces were much less likely to see publication. The Cannabich symphonies published by Götz in the 1770s call for the standard a 8 orchestra, but those written just for the Mannheim court often add two clarinets, and the unpublished No. 44 is for a double orchestra.22 Nonetheless, a number of Cannabich’s unpublished symphonies require only the a 8 ensemble, perhaps because of its practicality or because it was the most effective choice for relatively small spaces. Separate parts for flutes, bassoons and cellos became increasingly common (clarinet parts remained rare), and trumpets and timpani still seem to have been reserved for works intended to convey ceremony and splendour. In fact, although instrumental requirements grew steadily, a ‘full’ wind complement of pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns and trumpets did not become a standard choice until the early nineteenth century.

The variety of formal approaches found in the early part of the century had by now coalesced into the sonata types described by Hepokoski and Darcy, particularly for opening fast movements. Sonata forms also predominate in slow movements and finales, though rondos or other part forms, and occasionally simple binaries, can be found as well. Although the Type 3 sonata (having a recapitulation beginning with P in the tonic) seems to have been increasingly preferred, the Type 2 (in which the return to the tonic coincides with post-P materials) was also very common. It would be anachronistic to assume (as has often been done) that the Type 2 was ‘more primitive’ than the ‘full’ Type 3, since a single symphony could easily have both, and neither individually nor collectively did composers ‘progress’ from Type 2s to Type 3s. One suspects, in fact, that the choice of a Type 2 might have been practical as well as aesthetic, keeping the performance time manageable as movement length increased.

Sonata form proved to be the ideal solution to the organisational challenge of longer movements, providing both the framework and flexibility for creating works that were both immediately understandable as types yet distinctly different as pieces. In the exposition, for example, the two main patterns (two-part and continuous) described by Hepokoski and Darcy are ubiquitous. Many composers, like J. C. Bach, preferred the two-part approach with its clearly delineated secondary theme articulated by a strong medial caesura, dynamic and textural changes (often to piano and reduced orchestra) and sometimes contrasting material. This pattern (which incorporated the local contrasts described above into a larger structure) provided aural guidance to listeners but nonetheless allowed for the small yet piquant variations so essential to the style. The C minor slow movement of Bach’s Op. 6, No. 5 reaches a v:HC medial caesura in bar 14, but instead of a second theme in v, we hear one in III.23 The frequency with which transition material led to a medial caesura made it possible for composers (particularly Joseph Haydn) to subvert this expected pattern with a continuous exposition that avoided a secondary theme entirely. These continuous expositions typically have a very different sound and trajectory from the continuity described above in the C. P. E. Bach symphony because their transitions, which continue past the temporal point where a secondary theme would normally have appeared, have a relentlessness that creates an ever greater need for the tonal closure the exposition requires. Here too, the techniques for creating this tension (crescendos, addition of instruments, motivic shortening, sequences, deceptive cadences, etc.) could be combined in an infinite variety of ways, so that each work could provide a new listening experience. All parts of the sonata structure could be manipulated in this fashion: ‘development’ sections could present new material; ‘recapitulations’ could undertake further development. Procedures found in Gossec’s recapitulations, for example, range from more-or-less exact repetitions to those that reorder the exposition themes, or incorporate new material that had been introduced in the development, or involve considerable recomposition.24 In creating these variations on the sonata theme, individual composers differed widely both in degree and techniques, but all except the worst usually managed to devise an unexpected twist or an artfully different sound to delight both the ear and the mind.

Orchestration often played a significant role in this manipulation of conventions and in the overall success of the work. Many first-movement primary themes are noisy, exciting, triadic affairs played by the full ensemble, but the first movement of Cannabich’s Symphony No. 57 in E flat opens with violins and clarinets sustaining an E♭ over the moving bass line; by bar 7, the clarinet has taken over the melody, while the violins and basso line punctuate with turn figures. At any point in the movement, this configuration would be arresting, but it is particularly so for an opening. Like Cannabich, Rosetti had a knack for configuring the orchestra in unexpected ways and using the winds at exactly the right moment. His D major Symphony from c. 1788 opens with a single noise-killing chord before the violas, cellos, basses and bassoons enter with the theme, punctuated by the violins and upper winds. The third movements of Brunetti’s four-movement symphonies – all dances but not all minuets – use a wind quintet for the A section and strings for the second, an inversion of the often-used procedure of featuring winds in the B section (or trio) of the minuet. In the Symphony No. 9 in D, the Allegro Minuetto first section, scored for two oboes, two horns and bassoon, leads to a B section for strings and timpani.

In the late eighteenth century, texture was closely related to orchestration and wind usage, because subtle use of instrumentation could create variety in an essentially homophonic texture. Purely fugal movements are relatively rare and tend to call attention to themselves. Luigi Borghi’s rondo Finale to his Op. 6, No. 6, published in 1787, dissolves into a fugue, as if to defy conventional expectations.25Joseph Martin Kraus’s 1789 one-movement Sinfonia per la chiesa, written for the blessing of the parliament in Sweden, opens with a slow introduction followed by a fugue, albeit one in two sections (the first repeated!), ending with a substantial section presenting the fugue theme homophonically. More commonly, composers wove counterpoint and a variety of textures into the fabric of formal procedures, using the differences and shadings to delineate formal areas (just as earlier composers had done), but also to complicate them. In the first movement of his F major Symphony (Mennicke 97 from before 1762), Johann Gottlieb Graun (1702/3–71) introduces a brief contrapuntal interchange just at the point when a secondary theme seems to be emerging (bar 30) to convert from a two-part to a continuous exposition (Example 3.5). The transition in the first movement of Cannabich’s Symphony No. 73 in C moves noisily and homophonically towards V as expected, but at the moment when V/V arrives and S should appear, he switches to the minor mode and reduces the texture to piano contrapuntal lines, in effect derailing the transitional train and stretching the tension over another 20 bars (Example 3.6). The contrapuntal minuets that turn up in the symphonies of Joseph Haydn, W. A. Mozart, Wenzel Pichl (1741–1805), Gossec and Brunetti count as sly tweaks to convention in their conflation of the most learned of musical styles with the most courtly and galant of dances.

Example 3.5 Johann Gottlieb Graun, Symphony in F major (Mennicke 97), I, bars 24–42.

Example 3.6 Christian Cannabich, Symphony No. 73 in C major, I, bars 31–66.

The increasing length of individual movements and the variety of textures and styles they incorporated meant that composers needed to develop new strategies for creating unity even beyond the trajectory provided by sonata form. Perhaps the most common technique was the derivation of transition and closing materials from the opening primary material, a practice so ubiquitous it is found even in melody-rich compositions like those of W. A. Mozart. Composers as disparate as Karl d’Ordonez (1734–86) and Gossec were fond of constructing intricate motivic connections among seemingly contrasting themes. Although Pichl’s slow introduction to the first movement of his Op. 1, No. 5 has no motivic connection to the material that begins in bar 67, the slow, regular quaver motion, the restricted range, the legato markings and piano dynamic level call up the aural memory from earlier in an even more compelling way than a motivic recurrence could have done (Example 3.7a and b). Sometimes such techniques connected movements as well. Nearly all of Michael Haydn’s (1737–1806) late symphonies share motives among all the movements, a procedure also found in the works of Pichl and Adalbert Gyrowetz (1763–1850) among others. Although sometimes the shared motives can seem too generic to be convincing as cyclic links, when used in combination with parallels of texture and articulation, they signal a clear connective intention on the part of the composer.26Beginning as early as 1771, Boccherini explored even more extreme manifestations of unity, sometimes reprising large sections of earlier movements in the later ones. The Finale of his Symphony No. 21 (G. 496) comprises a complete repetition of the first movement’s recapitulation.27These instances should put the often cited cyclic aspects of some of Haydn’s and Beethoven’s symphonies in perspective. Such techniques were part of a new set of symphonic conventions just beginning to emerge at the end of the century.

Example 3.7a Wenzel Pichl, Symphony in F major, Op. 1/5, I, bars 1–8.

Example 3.7b Wenzel Pichl, Symphony in F major, Op. 1/5, I, bars 67–79.