The present article is an examination of the link between studies of Southeast Asia written by early modern Chinese scholars and the activities of Chinese sailors and merchants in that region. It proposes that the early modern sources illustrate the extent and structure of China's maritime trading network in Southeast Asia during different periods, both by their contents and by their lacunae. Beginning in the sixteenth century, some scholars began gathering up-to-date information on Southeast Asia from mariners in order to give their readers contemporary descriptions without relying on accounts that had been written centuries earlier. However, this strategy was limited by the geographic extent of the trading networks that existed at the time of the scholars’ research. Chinese mariners could usually only offer detailed information on the Southeast Asian subregions that their ships had actually sailed to. Subregions that lay beyond the trading network would usually receive no more than a passing mention, if the names of specific states and ports were included at all. These early modern sources derived from the experiences of contemporary mariners therefore reflect the changing dimensions of the Chinese trading network in Southeast Asia. As well, the Chinese sources, when examined alongside current scholarship on Southeast Asian economic history, can help us understand how the interaction of Chinese, European, and indigenous commercial systems restructured trade in Southeast Asia and produced new shared networks that functioned in ways distinct to their historical moment.

The first part of this article examines several Ming and Qing scholarly studies of Southeast Asia and then compares their contents to navigational rutters and maps created during the same periods. Following a number of recent historical mapping projects,Footnote 1 the article also uses geographic information system technologies to plot both the destinations and sailing routes described in the sources onto modern maps, visually reproducing their geographic information. This allows for the visualisations of the geography of Southeast Asia and the maritime trading system within it as it was understood by early modern Chinese writers and cartographers. These visualisations in turn allow comparisons of the geographic representations at the same scale. Consequently, the modern maps we have produced from both the textual sources and traditional maps show how the imagined geography of Southeast Asia changed over the course of the tortuous historical transition from the Ming to Qing dynasties.Footnote 2

Our analysis reveals changes in the depth and limits of Chinese geographic knowledge of Southeast Asia during the late Ming period (roughly 1500 to 1644) and the early Qing period after the dynasty's legalisation of maritime trade (1684 to about 1740). Perhaps surprisingly, during the late Ming the authors of the various sources seem to have had a more extensive geographic knowledge of Southeast Asia than later scholars. In the early Qing period the textual studies, rutters, and maps seem to have had up-to-date information on a handful of specific subregions and ports, including Siam, Luzon, western Java, and the Trinh and Nguyen domains in what is now modern Vietnam. Other areas that the Ming authors and cartographers had included, especially ports in eastern Java, the Lesser Sunda Islands, Sumatra, and the Straits of Melaka, are largely absent in the early Qing-era sources.

The reason for this divergence in the depth and breadth of information in the sources is most obvious in their descriptions of sailing routes. Before the collapse of the Ming dynasty, the textual sources, rutters, and maps that describe Southeast Asia all include routes that linked China not only to the relatively near ports of Luzon and Indochina, but also to ports in Sumatra, the southern Malay Peninsula, eastern Java, and the Lesser Sunda Islands. In the Qing sources, ports in these subregions are sometimes mentioned, but with a few obvious exceptions, such as Johor and Palembang, they are not linked to China or other ports by explicit routes. The implication is that Chinese ships had sailed to ports in these subregions during the late Ming period, but were not doing so in the early Qing.

The final section of this article will attempt to offer some explanations for how larger changes within the trading worlds of Southeast Asia had brought about this reshaping of the Chinese network after the end of the Ming dynasty. Anthony Reid's well-known ‘age of commerce’ theory proposes a general economic decline in Southeast Asia during the mid-seventeenth century thanks to a number of factors, most importantly a cooler global climate, a weakening of global trade, and the monopolistic policies of the Dutch Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC).Footnote 3 Consequently, according to Reid, many previously important port emporia withdrew from the region's commercial world, leaving a larger and larger share of trading activity concentrated in a handful of centres, but most especially the European enclaves.Footnote 4

At first blush it appears that the less extensive Qing-era trading network and consequently more restricted geographic knowledge of Chinese writers and cartographers supports Reid's hypothesis. But on closer examination, only some of the changes to the geographic scope of the trading network can be easily attributed to the factors he cites. The northern coast of Java and the Lesser Sunda Islands were areas where Chinese geographic knowledge contracted between the late Ming and early Qing periods. In this case the contraction was certainly a result of the expansion of Dutch power along Java's pasisir in the 1670s and 1680s, and the company's insistence thereafter that China-based ships restrict their Javanese trade to Batavia. However, along the northern littoral of the Java Sea, the early Qing-era sources suggest that Banjarmasin on the south coast of Borneo became the terminus for most China-based shipping, and this was likely not because of a decline or a retreat from commerce by other ports in the eastern archipelago. Instead, more recent scholarship by Jennifer Gaynor and others has shown that despite the VOC's 1669 conquest of Makassar, southern Sulawesi's most important port in the seventeenth-century, a healthy trading system continued in eastern Southeast Asia dominated by Bugis traders and other independent indigenous groups.Footnote 5 Similarly, in the Straits of Melaka subregion, the lack of accurate detail about most port centres except Johor in Qing sources may reflect the deepening state-integration that J. Kathirithamby-Wells has described. As state power in major centres grew during the seventeenth century, merchants based in those centres were increasingly able to penetrate the production sites of export goods bypassing smaller centres, thus increasing the predominance of their own bases as shipping hubs.Footnote 6

To make these arguments, this article focuses solely on the handful of early modern Chinese sources concerning Southeast Asia whose authors attempted to provide contemporary descriptions of the region. Though a variety of books that discussed Southeast Asia were written in the late Ming period, and to a lesser degree the early Qing, many of them relied primarily on older materials dating back to Zheng He's 鄭和 voyages in the early fifteenth century or earlier. The first effort to write about the region using up-to-date information appears to have been the very short Hai yu 海語 (Sea talks), written by the scholar Huang Zhong 黄衷 in the early sixteenth century.Footnote 7 Huang was followed in the early seventeenth century by Zhang Xie 張燮, the author of the celebrated Dong xi yang kao 東西洋考 (Record of the eastern and western oceans).Footnote 8 In the Qing period, only a decade or so after the 1684 legalisation of maritime trade the travel-writer Yu Yonghe 郁永河 added an appendix to his Pi hai ji you 裨海紀遊 (The small seas travel record), which offered a brief overview of overseas geography, meaning mostly Southeast Asia, which he based on the accounts of other travellers.Footnote 9 About thirty years later, Chen Lunjiong 陳倫炯 wrote a much more extensive account of the world's geography in his Hai guo wen jian lu 海國聞見錄 (A record of what is known of the ocean countries), which he also based largely on the accounts of mariners.Footnote 10

The article will compare these textual studies to contemporary navigational rutters and maps that offer descriptions of sailing routes in Southeast Asia. The rutters, the Ming-era Shun feng xiang song 順風相送 (Fair winds for escort) and the early Qing Zhi nan zheng fa 指南正法 (General compass-bearing sailing directions), were written as guidebooks for navigators. They describe routes that ships could take from Chinese ports to destinations in Southeast Asia by guiding them step-by-step from landmark to landmark with directions and distances. Similarly, the Selden Map of China, created in the late Ming period, and the map of Southeast Asia that the military official Shi Shipiao 施世驃 commissioned in the 1710s both describe the sailing routes directly with clear lines drawn between China and the ships’ Southeast Asian destinations.

A final note on terminology and the categorisation of geographic space is necessary here. The present study takes the argument of Martin Lewis and Kären Wigen's Myth of continents to heart.Footnote 11 Despite using the term ‘Southeast Asia’ throughout, we do not assume that this space as a region objectively exists or possesses an internal coherence. Rather, it is a convenient modern translation for the arena of maritime activity that Zhang Xie referred to as the dong yang and xi yang (western and eastern oceans) and that Chen Lunjiong referred to as the dong nan yang and nan yang (southeastern and southern oceans).Footnote 12 Essentially, the term here refers to the area from Vietnam to Luzon and the northern tip of Sumatra to Timor and the Maluku Islands, the effective sailing limit of Chinese ships between about 1500 and 1800.

Scholarship on foreign geography in early modern China

There is a rich literature on Ming and Qing-era perceptions of China's maritime frontier and its overseas neighbours. To date, the majority of it has been focused on answering questions concerning the actions and attitudes of China's late imperial states and therefore relatively little has been said about the origins and structure of knowledge related to overseas regions, or about the possession of knowledge by actors outside of the state.Footnote 13 However, there is also a tradition of research on early modern navigational sources, including maps and rutters.Footnote 14 Because the navigational sources were created for mariners and probably in most cases by mariners, their contents are naturally direct descriptions of contemporary sailing patterns, a type of information that usually did not concern China's imperial governments. The present article is more closely related to these studies of navigational sources, and argues the textual studies that relied on the accounts of mariners are also necessarily descriptions of the sailing and trading systems that existed in Southeast Asia, albeit indirect and partly unintentional ones.

Two scholars have recently tackled the question of late imperial Chinese knowledge of foreign geography head-on, and their findings are particularly relevant to the present study. The first is Matthew Mosca's work on Qing China's understanding of India and Indian geography, one of the most imaginative and incisive recent examinations of early modern Chinese intelligence on foreign states. According to Mosca, the Qing perception of India (both within the government and within scholarly circles) was the product of an approach he refers to as ‘geographic agnosticism’. Rather than attempting to formulate a single unified geographic vision in which data could be fit without contradiction as contemporary European scholars were doing, Chinese geographers treated their various contradictory sources as a range of possibilities that were all worthy of consideration. Thus the geographers would quote medieval Buddhist texts alongside more modern Muslim and Jesuit descriptions of India, prioritising the presentation of a plurality of information over the determination of a single conclusive statement.Footnote 15 Even more recently, Elke Papelitzky has closely examined seven late Ming ‘world histories’, and has come to essentially the same conclusion as Mosca. The descriptions of foreign countries in these texts relied primarily on ‘a patchwork of previous sources’ synthesised uncritically.Footnote 16 Most of the authors therefore evince the same sort of agnosticism towards the veracity of their texts as the ones from the Qing period that Mosca studies, and most make no effort to seek out up-to-date information for their descriptions. The only exception that Papelitzky identifies is in the Si yi guan kao 四夷館考 (Record of the foreigners’ institute), in which the author cites an interview with a contemporary Siamese envoy.Footnote 17

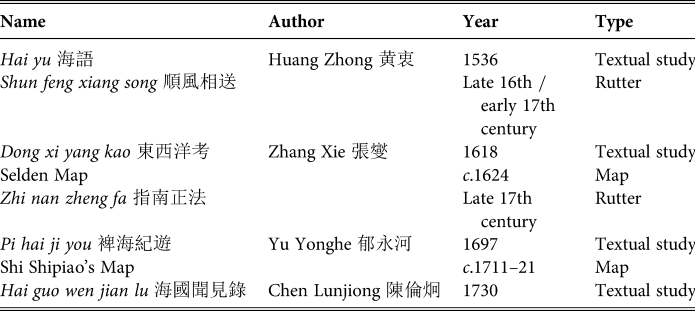

The texts examined in the present study (table 1) are therefore not representative of the typical methods used by scholars studying foreign countries in the late Ming and early Qing periods. The focus here is on a particular strain of scholarship on Southeast Asia that prioritised first-hand information. Some geographic agnosticism is evident, especially in the sections on foreign customs, but in each case the primary source of information the authors relied on were reports given by contemporary Chinese mariners who had actually visited the countries described in the texts. This study therefore does not dispute any of Mosca's or Papelitzky's conclusions, but it does attempt to show that there were texts that did privilege first-hand accounts over a synthesis of older works, and these provide a particularly useful window onto Chinese activity in Southeast Asia and onto the region's larger trading world as well.

Table 1. Early modern Chinese sources discussed in this study

Late Ming geographies, 1500–1644

The majority of Ming Chinese geographers who wrote about Southeast Asia during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries offered their readers little in the way of up-to-date information on the geopolitics of the region. This was perhaps because most of them were scholars and officials who had little connection to China's coastal regions, and whose primary interest in foreign geography was the security of China's land frontiers. Their works relied primarily on geographic information contained in books published during earlier dynasties, on the works produced by authors who accompanied Zheng He to Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean in the early fifteenth century, and sometimes on government records related to tribute embassies sent to China.Footnote 18 These types of sources were able to speak in general terms about the cultures, local products, and political systems of Southeast Asian states, but they had very little information about any recent developments beyond China's shores.

However, during the latter half of the Ming dynasty there were at least two authors who did attempt to use more current sources of information in their writings on Southeast Asia. Collecting information directly from mariners seems to have been an approach pioneered by the scholar Huang Zhong in his Hai yu.Footnote 19 The Hai yu, published in 1536, is a very short work that covers only Siam and Melaka in detail. Its novelty though was that the author, according to his preface, interviewed Chinese mariners rather than relying on older works.Footnote 20 The advantage of this approach is quite apparent even in Huang's short text. Its description of Melaka ends with an account of an attack on the city by the Portuguese (the Folangji 佛朗機, or Franks), which occurred in 1511, just 25 years before. The basic fact of Melaka's capture was also known by the Ming court within a decade or so after it occurred, but Huang's account is far more detailed than the one preserved in the Ming shi lu 明實錄.Footnote 21

Huang does not include specific names or dates, but his general outline is quite precise. He recounts an initial attempt by Portuguese ships to trade at Melaka that ended in the imprisonment of several men, followed by another Portuguese fleet's capture of the town. He ends by saying that after the Portuguese looted the town, they departed and the Melakan sultan returned. This claim is not quite accurate of course, but Huang may have been extrapolating from information he had collected concerning the aftermath of the city's capture. The Portuguese did not depart, but their commander, Afonso de Albuquerque, did return to India the following year, and although Mahmud, Melaka's former sultan, never did recover his city, he made several attempts to do so and established a new residence near the city in 1518.Footnote 22

Although the Hai yu was read and cited throughout the remainder of the sixteenth century,Footnote 23 no author appears to have adopted Huang's approach to geographic research on Southeast Asia until about eighty years later. Huang's lack of followers may have been in part the result of changes to the trading system beginning around the time of his book's publication. Huang's home district and the centre for his research was Guangdong's Nanhai County 南海縣.Footnote 24 Most of the mariners and merchants he met were likely those who had accompanied tribute embassies coming to Guangzhou, and by his lifetime the tributary trading system had already begun to decline. This fact helps explain the limited geographic scope of his book and lack of any immediate follow-up scholarship using his approach.Footnote 25 The centre of China's maritime trade was shifting towards southern Fujian, and unlike Guangzhou's trade with merchants who had come with tribute embassies, the mid-sixteenth century maritime trade through Fujian was primarily a smuggling business. Smugglers would naturally have been harder to recruit as informants for another project like Huang's, so this was probably why it was not until after the partial lifting of the prohibition in 1567 that Fujianese merchants began contributing to China's knowledge of Southeast Asia.Footnote 26

The author who became Huang Zhong's truest successor was the Fujianese scholar Zhang Xie, although he does not seem to have consulted Huang's book. Zhang's work, the famous 1618 Dong xi yang kao, was unsurpassed until the nineteenth century in its breadth, accuracy, and the currentness of its information on Southeast Asia. Zhang made use of older sources, but like the Hai yu, the real value of the Dong xi yang kao comes from the information Zhang personally gathered from mariners.Footnote 27 Zhang uses this information to write in detail about virtually all of Southeast Asia, from Luzon to Timor in the east and from the Vietnamese Trinh domain to Aceh in Sumatra in the west. Most impressive is the information it provides on the political geography of the parts of Southeast Asia that had very little formal contact with Ming China through tribute embassies, particularly the Indonesian archipelago east of western Java.

A few examples will suffice to demonstrate this. The clearest ones are the instances related to the presence of Europeans in Southeast Asia because of the detailed records they left that can be used for comparison and verification. One of the most impressive passages is Zhang's account of the Spanish–Dutch conflict in the distant Maluku Islands, which had begun in 1606. Though Zhang does not seem to have had a clear understanding of the rival monarchies of Tidore and Ternate, he did understand the European presence, as he accurately describes how both the Dutch and Spanish occupied ports on Ternate (Wanlaogao shan 萬老高山).Footnote 28 In the part of his book devoted to the ‘needle routes’ (zhen lu 針路) that give directions for Chinese ships sailing across Southeast Asia, Zhang also notes that the island of Solor (Sulu shan 蘇律山) on the route to Timor was occupied by the Dutch (whom he calls red-haired foreigners, hong mao yi 紅毛夷, in this section). The Dutch took the island from the Portuguese in 1613, so in this case Zhang's information is current to within five years.Footnote 29

Zhang's knowledge of the political situations in different parts of Asia was not limited to the activity of Europeans. In the case of eastern Java, a subregion that his followers in the early Qing dynasty seem to have had very little knowledge of, he apparently had access to rumours concerning the political and religious situation. Zhang describes a region called Sijigang 思吉港, which he says is an error for Sujidan 蘇吉丹. This probably refers to Surabaya, which at the beginning of the seventeenth century was the most powerful state on Java's northeastern coast.Footnote 30 Zhang states that the main settlement was an inland centre called Jilishi 吉力石, and that the city had a ruler who was over a hundred years old and who was capable of knowing fate (‘neng zhi ji xiong 能知吉凶’).Footnote 31 This passage almost certainly refers to the settlement of Giri and its priestly ruler, the Sunan Giri, who, though not the lord of Surabaya, still had enormous spiritual authority in the region.Footnote 32

The other aspect of Zhang's book that demonstrates the breadth of his knowledge of Southeast Asia are the aforementioned needle routes. These routes describe the paths that Chinese ships would take from China's coast to different parts of the region. Zhang's routes are similar in their scope to those in the probably roughly contemporary Chinese rutter Shun feng xiang song, discussed in more detail below. Zhang gives routes from China's coast to destinations as far away as Aceh, eastward across the Indonesian archipelago as far as Timor, and to Brunei, the Sulu Islands, and the Maluku Islands.Footnote 33 Precise landmarks are noted in each case, and in some instances information about the landmark is given, such as the Dutch occupation of Solor mentioned above. Especially in the case of the routes in the eastern Indonesian archipelago, the coverage of the Dong xi yang kao was far broader than that of its counterparts written in the early Qing period (see fig. 1), as the following section will attempt to show.

Figure 1. Dong xi yang kao 東西洋考, 1618

Early Qing geographies, 1684–1740

Twenty-six years after Zhang's Dong xi yang kao was published, the Ming dynasty collapsed and China was invaded by the armies of the new Manchu Qing state. A period of intermittent warfare lasting from 1644 to 1684 followed, during which the Qing attempted to block private trade between China and the rest of maritime Asia. Thanks to persistent resistance from the maritime-mercantile Zheng 鄭 family, the Qing state was mostly unsuccessful at preventing maritime trade, but its illegality does seem to have brought a temporary halt to research and writing on Southeast Asia within China. It was only after the Zheng regime's base on Taiwan was occupied in 1683 and the Qing government legalised maritime trade the following year that new writing on Southeast Asia began to appear.Footnote 34

At least two Qing-era scholars interested in Southeast Asia after 1684 willingly adopted the approach used by their Ming predecessors, Huang Zhong and Zhang Xie. They took advantage of the rapid growth in commercial traffic between China and Southeast Asia and set about interviewing mariners who had visited Southeast Asian ports. However, none of them came close to achieving the breadth of detail that the Dong xi yang kao had. The important ports and states relatively close to China, such as Spanish Luzon, the two Vietnamese domains, and Siam were well described, and some of the important more distant ports, including Batavia, Johor, Melaka, and Banjarmasin, were at least mentioned, but other areas, especially the eastern Indonesian archipelago, seem to have been practically unknown to early Qing authors.

The first post-1684 book written by a private scholar that attempts something approaching a comprehensive overview of contemporary Southeast Asia is Yu Yonghe's 1697 Pi hai ji you. The Pi hai ji you is primarily an account of Yu's travels in Taiwan, but his work also includes several appendices on other topics. The last of these he titles rather grandly ‘Yu nei xing shi’ 宇內形勢 (The terrain within the universe). Within it, he describes the geography of a number of Southeast Asian countries, as well as Japan, Korea, the Ryukyu Islands, the Netherlands, and England, arranging them along simplified sailing routes. To explain the source of his information, he states, ‘The above countries are all visited by merchant ships coming and going to trade, [so] their terrain, routes, scenery, people, and products can all be well-known.’ Yu does not cite any older works in regards to Southeast Asia, so it was evidently the mariners aboard these merchant ships who supplied him with his information.Footnote 35

For some of the locations he discusses, Yu's informants served him well. For example, he correctly states that in Aceh women could succeed to the throne and at the time he was writing there was indeed a female ruler in power.Footnote 36 He also recognises that the most important change to the geopolitical landscape of Southeast Asia since the days of Zhang Xie was the rising power of the Dutch VOC. His understanding of how the VOC's commercial empire operated is limited; he accuses the Dutch of being primarily pirates.Footnote 37 However, he does correctly describe how the VOC had occupied the port of Jakarta (Yaoliuba  ), which they renamed Batavia, on the island of Java.Footnote 38

), which they renamed Batavia, on the island of Java.Footnote 38

There are some gaping omissions and mistakes in the Pi hai ji you's descriptions of Southeast Asia though (see fig. 2). The mistakes are mainly the relative geographic locations of different ports. Yu thinks Banten (Wandan 萬丹) and Banjarmasin (Mashen 馬神) were south of Batavia for example. The Pi hai ji you's coverage of the region is also severely limited. In the eastern part of Southeast Asia, the major ports that Yu lists are Luzon (meaning Manila), the Sulu Islands (Sulu 蘇祿), and Brunei (Wenlai 文萊). He makes no mention of the Maluku Islands, which in the Dong xi yang kao had been the furthest destination along the eastern routes, or any of the Philippine Islands south of Mindoro. For the western route the Pi hai ji you includes both Vietnamese domains, Cambodia, Siam, Ligor (Liukun 六昆), Pattani (Danian 大年), Johor (Roufo 柔佛), Melaka, Aceh, Banten, Banjarmasin, and Batavia. However, east of Batavia no ports in Java or the Lesser Sunda Islands are mentioned at all.

Figure 2. Pi hai ji you 裨海紀遊, 1697

The section of Yu's work that discusses Southeast Asia is just a short appendix and when he wrote it in the mid-1690s the new Qing maritime trading network had only just begun to develop. From the late 1690s until the late 1710s, the Chinese trading network in the region appears to have matured and expanded in terms of the volume of trade.Footnote 39 Unfortunately no surviving studies of Southeast Asia were written in China during these two decades. Between 1717 and 1722, there was a short hiatus in trade because of a ban the Kangxi emperor placed on China-based merchant vessels trading with Southeast Asia. After the emperor's death in 1722, the ban remained officially in place for another five years, but was not rigorously enforced, allowing Chinese ships to return to Southeast Asian ports.Footnote 40

In 1730, three years after the ban on trade with Southeast Asia was officially lifted, the military official Chen Lunjiong completed the Hai guo wen jian lu. Chen claims that his investigation is based on accounts given to him by his father, who had also been a military official involved in coastal defence, a map that the Kangxi emperor had shown him, and information collected from interviews with mariners during his time stationed in Taiwan and Guangdong.Footnote 41 His book describes the coast of China, as well as countries and ports in maritime East Asia, Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, and the Atlantic Ocean (primarily Europe). The sections describing Southeast Asia are considerably fuller than those in the Pi hai ji you.

The strongest parts of Chen's descriptions of Southeast Asia are within his section on the region's eastern half (the ‘dong nan yang’ 東南洋 in the section's title), which includes today's Philippine Islands, Borneo, and some of the smaller islands around them. However, there is an obvious unevenness to the level of detail that he provides. Like the Dong xi yang kao, the Hai guo wen jian lu begins with Luzon and offers a long account of its Spanish government. Then the text moves on to briefly mention Lucena (Lizaifa 利仔發), Camarines Sur (Qimali 其馬力), and a number of other places farther south within the Philippine Islands. Chen only mentions that each of the places was connected economically to Luzon by Chinese merchant residents of Manila and that there was a demand for cloth in their markets.Footnote 42 In the case of Borneo and the islands closest to it, the book also identifies a number of destinations for Chinese ships, including the Sulu Islands, Brunei, Sukadanda (Zhugejiaola 朱葛礁喇), Banjarmasin, an unidentified place called ‘Jiliwen 吉里問’ somewhere to the east of Brunei in northern Borneo, and Sulawesi (Mangjiashi da shan 芒佳虱大山). However, the only one of these that Chen describes in detail is Banjarmasin, recounting the VOC's attempts to control the harbour and the gem trade there.Footnote 43 Similarly, although Chen mentions the Maluku Islands of Ternate (Wanlaogao 萬老高) and Dingjiyi 丁機宜 (probably Tidore), he says only that they were similar to the Philippine Islands. He does not mention the VOC's presence or the islands’ connection with spice production and distribution.

In the western half of Southeast Asia (the ‘nan yang’ 南洋), Chen does not offer much more than Yu, and significantly less than Zhang in terms of his coverage. The Hai guo wen jian lu includes long descriptions of the Vietnamese domains, Siam, and some of the surrounding states. Some details on the current political situations are offered, notably the struggle between Siam and the Nguyen domain in central Vietnam for influence over Cambodia.Footnote 44 For locations further south though, Chen apparently had less luck gathering information. He gives a list of Malay port cities, but offers no more than a blanket statement claiming that they were all tributaries of Siam, a list of their trade goods, and an unfavourable evaluation of their level of cultural attainment.Footnote 45

In the Straits of Melaka, Johor, Melaka, and Aceh all get a few sentences, but only Johor's seems to be reasonably accurate. Chen tells us that trade goods were more abundant in Johor than elsewhere in the Malay Peninsula and that the port could support three or four large ships per year. However, Chen confuses the political status of Melaka and Aceh, claiming that the former was independent while the latter was occupied by the Dutch. He goes on to mention Bengkulu (Wangulu 萬古屢) on the west coast of Sumatra, but only to say that it is southeast of Aceh. He also mentions Banten and a port called Xiagang 下港, which probably refers to Palembang, but the only information that the reader receives is that both places produced pepper.Footnote 46 For comparison, besides Aceh, Melaka, and Johor, the Dong xi yang kao includes full sections on Banten, Palembang (舊港), and Indragiri (Dingjiyi 丁機宜).Footnote 47

Batavia is the final place in Southeast Asia to receive a significant amount of description; Chen writes about the city's Dutch castle and harbour, its importance as a trade hub, and its large Chinese population. The most historically current piece of information his book gives regarding the city is that the VOC was attempting to stem the flood of new Chinese immigrants landing in Batavia, which tragically foreshadowed the rebellion of the Chinese in Java and the massacre of Batavia's Chinese population in 1740.Footnote 48 East of Batavia in the Indonesian archipelago, only Timor (Chiwen 池問) is identified, and the text only tells the reader that it produced pepper and sandalwood. As well, no sailing routes for Timor or anywhere else among the Lesser Sunda Islands are supplied.

Thus, as valuable as the Hai guo wen jian lu is for the information it contains on the politics and societies of some parts of Southeast Asia, its content is inferior to the Dong xi yang kao's portrait of the region in the early seventeenth century. Like the Dong xi yang kao, the Hai guo wen jian lu introduces the reader to major trading regions close to China, including the Vietnamese domains, Siam, and Luzon. It also gives the reader some detailed information on Batavia and Banjarmasin, which became important destinations for Chinese ships in the seventeenth century (see fig. 3). However, where the Dong xi yang kao was able to describe the beginnings of the VOC's attempt at becoming a maritime hegemon within the Indonesian archipelago by pointing to some of its earliest establishments in the Maluku and Lesser Sunda Islands, the Hai guo wen jian lu leaves these areas of the region almost unacknowledged, offering only slightly more information than Yu Yonghe's short section in the Pi hai ji you.

Figure 3. Hai guo wen jian lu 海國聞見錄, 1730

Other types of sources on Southeast Asian geography

The difference between the late Ming and early Qing trading systems is also evident when the scholarly studies discussed above are compared to the contents of contemporary navigational sources. Two obvious types of these sources are available for this discussion, rutters and maps. The present study will begin with the two famous rutters, the late Ming Shun feng xiang song and the early Qing Zhi nan zheng fa, both held by the Bodleian Libraries of the University of Oxford.Footnote 49

Unlike the scholarly studies, the rutters were not produced by writers recording information for the benefit of the reading public; rather they were navigational aids probably created by mariners themselves to guide their ships across Asia's seas. Both rutters have been extensively studied, but there has been little discussion of the reasons behind the difference in their respective scopes.Footnote 50A graphic comparison between the contents of the two rutters, accomplished by mapping out the routes they describe in their texts, quickly reveals that they follow the same pattern as the scholarly studies. The Shun feng xiang song, which appears to have been compiled in the late sixteenth century or the beginning of the seventeenth,Footnote 51 presents a map of the trading routes across Southeast Asia that looks much like that given by Zhang's Dong xi yang kao (compare fig. 1 above with fig. 4 below). In the east, it guides the navigator first to Luzon. From there, the text offers further routes to take him onto Brunei, the Sulu Islands, and Mindanao.Footnote 52 Curiously, the Maluku Islands, which are included in most of the other sources discussed here, are absent in the Shun feng xiang song. In the west, it includes detailed routes from China's coast to Aceh, two ports in western Sumatra,Footnote 53 and several places in the Indian Ocean beyond. For central and eastern Java and the Lesser Sunda Islands, it gives the navigator two options. They may sail south from China along the coast of modern Vietnam, across the mouth of the Gulf of Thailand to Pulo (Pulau) Tioman, and then to Banten, from where ships could set out eastward along Java's northern coast to Cirebon, Demak, and Tuban. The second option is to sail south from the coast of modern Vietnam to western Borneo, then follow its coast southward, cross the Java Sea, and arrive at Tuban. Beyond Tuban, the route continues to nearby Gresik in eastern Java and as far as Timor.

Figure 4. Shun feng xiang song 順風相送, late 16th to early 17th century

The Shun feng xiang song's Qing-era counterpart, the Zhi nan zheng fa, describes a far less extensive trading system. This may have been in part because its compilation probably occurred in the late seventeenth century, making it a product of the early years of the new trading system, similar to the Pi hai ji you.Footnote 54 However, the overall shape of the trading system in Southeast Asia that it provides looks much like the descriptions in both the Pi hai ji you and Hai guo wen jian lu. Once again, the eastern sailing routes are more complete than the western ones. The rutter leads ships past Luzon to Brunei, the Sulu Islands, Mindanao (Wangjinjiaolao 綱巾礁荖), and the Maluku Islands. The western routes in the Zhi nan zheng fa (fig. 5) are again stunted compared to those described in the Shun feng xiang song (fig. 4) and the Dong xi yang kao (fig. 1). The rutter offers routes to Vietnamese harbours, Cambodia (meaning the Mekong Delta), Siam, and various ports along the eastern coast of the Malay Peninsula. Further south though, the rutter's compiler only bothered to include three destinations, Melaka, Palembang, and Batavia. Johor is not mentioned at all, suggesting that the work may have been completed during the late 1680s when that sultanate was in political chaos.Footnote 55 Banjarmasin is also absent, and no other place in Borneo is included, save Brunei.

Figure 5. Zhi nan zheng fa 指南正法, late 17th century

Maps that trace shipping lanes are the other type of source on Southeast Asian geography that lend themselves to a comparison with the scholarly studies. In the late Ming period the most obvious candidate is the famous Selden Map, which was rediscovered in the Bodleian Libraries in 2008.Footnote 56 Historians have already studied the map extensively, and from their work we know that it entered the library in 1659, and was probably created around 1624, making it a close contemporary of the Dong xi yang kao.Footnote 57 The map does not fit perfectly into the analysis of the current article because unlike the other sources it was likely produced somewhere in Southeast Asia, perhaps Aceh, rather than in China.Footnote 58 However, the cartographer was still probably from southern Fujian, and was probably affiliated with some part of the late Ming dynasty's maritime merchant community.Footnote 59 If he was, he would have come from the same class of people as Zhang Xie's informants and likely the compiler of the Shun feng xiang song as well.

The cartographer of the Selden Map traced a series of sailing routes onto the map that all begin in southern Fujian or Guangdong, much like all the other sources. However, perhaps because he was based in Southeast Asia and may have had access to European maps, his vision of the Southeast Asian trading system was in some respects more complete than the other Ming sources as our modern remapping of locations and sailing routes in fig. 6 demonstrates. For the eastern part of Southeast Asia, the Selden Map shows the same pattern of routes connecting Manila to a number of other places within the Philippine Islands, to Brunei, to the Sulu Islands, and to Mindanao. The most southern destination in the east is Ternate once again, and like the Dong xi yang kao, the map recognises the presence of the VOC; on the island there is a circle labelled ‘hong mao zhu 紅毛住’ (‘controlled by the red-haired ones’). Along the western routes the map includes a number of locations in central and eastern Java and in the Lesser Sunda Islands, including Tuban (Zhuman 豬蠻), Gresik (Raodong 饒洞), Bali (Mali 磨厘), and Timor (Chiwen池汶). However, it also includes a sailing route not present in either the Dong xi yang kao or Shun feng xiang song. The route begins in Banjarmasin and heads eastward, connecting Makassar (Bangjiashi 傍伽虱), Kota Ambon (Anwen 唵汶), and Banda (Yuandan 援丹).

Figure 6. Selden Map of China, early 17th century

The Selden Map's early Qing counterparts were two very similar maps of Southeast Asia that were created in the late Kangxi reign. These maps were commissioned by the Qing officials Shi Shipiao 施世驃, the Fujian shui shi ti du 福建水師提督 (Fujian naval commander), and Gioro Manbo 覺羅滿保, the Fujian xun fu 福建巡撫 (Fujian governor). The precise dates of their creation are unknown, but the officials submitted them to the Kangxi emperor sometime between 1711 and 1721. Both maps have labelled place names, but Shi's includes lines connecting port cities that represent trade routes just as the Selden Map does.Footnote 60 When Shi's map's locations and sailing routes are remapped, the geographic extent of the trading system it depicts looks much like that of all the other Qing-era sources discussed here (fig. 7). The eastern routes take trade ships to Manila, Brunei, the Sulu Islands, and Cebu. Ternate is marked on the map, but, unlike the Hai guo wen jian lu and the Zhi nan zheng fa, there is no sailing route to the Maluku Islands. Along the western routes, the destinations are the two Vietnamese domains, Siam, Chaiya, Ligor, Songkhla, Pattani, Trengganu, Pahang, Johor, Melaka, Palembang, Batavia, and Banjarmasin. No route goes farther eastward in the Indonesian archipelago than Batavia, and the Lesser Sunda Islands, along with eastern Java, have been cropped out of the map altogether.

Figure 7. Shi Shipao's map, c.1711–21

Shi Shipao's and Gioro Manbo's maps do however show a greater awareness of the basic geography of the Indonesian archipelago than any previous Qing-era work. For example, three cities on the north-central coast of Java, Cirebon (Jingliwen 井里問), Jepara (Erbona 二泊那), and Semarang (Sanbalong 三把籠), are identified on the maps. So are a number of smaller centres in Borneo, and the island of Sulawesi (Mangjiashi da shan 芒加虱大山, meaning ‘Makassar Island’) is included as well. However, none of these locations are connected to the trade routes that the map's creator traced between China and the ports listed above.

The trading worlds of Southeast Asia

Why were these early Qing studies, rutters, and maps so geographically uneven in their coverage of Southeast Asia compared to their late Ming counterparts? Yu's Pi hai ji you was just a brief appendix, and was written only a decade or so after the Qing dynasty's legalisation of maritime trade. We can speculate that because the trading system was still developing, in the 1690s Yu had difficulty finding informants who had travelled to the farthest reaches of the region. The Zhi nan zheng fa appears to have been compiled around the same time as the Pi hai ji you, and thus may also reflect the trading system in its infancy. However, by 1730 when Chen completed the Hai guo wen jian lu, the new Qing Chinese trading network in Southeast Asia had been operating for almost half a century, excluding the brief hiatus caused by the trade ban late in the Kangxi emperor's reign. Had Chen done his research in southern Fujian (as Zhang had), he might have had a larger pool of informants to draw upon because Xiamen was then the main port for Chinese merchant ships that sailed to Southeast Asia. However, he was stationed in coastal Taiwan and Guangdong when he collected his information, and both places were well integrated into the Xiamen-centred coastal trading network, so finding informants should still not have been that difficult. He did, after all, manage to collect extensive descriptions of Luzon, Siam, and the two Vietnamese domains, and had current information regarding Batavia and Banjarmasin. Shi Shipiao, as the Fujian shui shi ti du, was stationed in Xiamen, and as the province's most senior naval commander he would have been in an even better position to help his anonymous cartographer collect the most current information available from Chinese mariners.

The most probable explanation for the comparative weakness of the Qing sources is that the trading systems that existed at the beginning of the seventeenth century differed substantially from the one that emerged in the early Qing dynasty. The most visible change was the VOC's much larger presence in Southeast Asia at the end of the century. In Zhang Xie's time, the Dutch company had only just begun to penetrate some Southeast Asian markets, and were only a factor for Chinese merchants in a handful of places in the eastern peninsula. By the end of the century the company had established a new headquarters, in Batavia, Java, and had gained suzerainty or direct control over many of the formerly important port centres in the Indonesian archipelago, including Melaka, Makassar, Semarang, Cirebon, and Banten.Footnote 61

The rise of the company's power probably had the greatest impact on Chinese trade on the route that followed the southern littoral of the Java Sea, running eastward from Banten or Batavia along the northern coast of Java's pasisir and the Lesser Sunda Islands and usually terminating in Timor. This route, which was also described by Portuguese merchants in the sixteenth century, was a prominent feature of the late-Ming Dong xi yang kao, Shun feng xiang song, and Selden Map.Footnote 62 The company's wars in eastern Java during the 1670s and 1680s ended up giving the company control over trade in most of the pasisir's important ports just before the Qing government lifted its prohibition on maritime trade. The company's goal was to channel long-distance trade towards Batavia, and consequently the pasisir ports to the east were no longer viable destinations for ships sailing directly from China.Footnote 63 Chinese immigrants to Java who settled in the pasisir's ports gradually became important participants in commerce within the archipelago, but they did not directly take part in the trade between Southeast Asia and China.Footnote 64 Chinese immigrants and sojourners in central and eastern Java were likely the indirect source of information that Shi Shipiao's cartographer used to add Cirebon, Jepara, and Semarang to his map, but the lack of direct connections explains why the Java Sea's southern littoral route did not appear in any of the Qing-era sources discussed in this article.

The route running along the northern littoral of the Java Sea, from the southern coast of Borneo, past Sulawesi, and then onto the Maluku Islands, was the most important west–east branch of their trading network for the Chinese merchants in the Qing period. However, only the Selden Map and the Hai guo wen jian lu describe this sailing route continuing east of Borneo. The likely reason for the exclusion of this route from the other sources was that although it supplied valuable commodities from the eastern archipelago (spices, trepang, and sea turtle shell, among other things), the Chinese themselves rarely sailed it in either Ming or Qing times. Jennifer Gaynor's study of the Sama people in southern Sulawesi and their relationship with other groups highlights the role the Sama, Bugis, and Makassar peoples played in connecting the eastern Indonesian archipelago to transhipment points on Borneo beginning in the Ming dynasty.Footnote 65 In the early Qing period, the Hai guo wen jian lu's relatively long description of Banjarmasin suggests that that riverine port had become the main hub for Chinese merchants seeking access to the northern Java Sea littoral trading system, which was still dominated by merchants based in southern Sulawesi.Footnote 66 Shi Shipiao's map and the Pi hai ji you also show the northern littoral route terminating in Banjarmasin, supporting the hypothesis that that port had become the most important node connecting the Chinese and eastern archipelago trading systems.

In the western part of Southeast Asia, the main discrepancy between the Ming and Qing sources was eastern Sumatra and the Straits of Melaka subregion. During the late Ming period, when Melaka was under Portuguese control, there was no single dominant trading centre; the Portuguese had intended to make Melaka the emporium of the entire subregion, but competition from neighbouring Johor, Banten, and Aceh prevented this.Footnote 67 The Portuguese also undermined their own position with unfavourable treatment of long-distance merchants. Some of these even began avoiding the Straits of Melaka by sailing through the Straits of Sunda and along the west coast of Sumatra,Footnote 68 and this is likely at least part of the reason that the Ming-era Shun feng xiang song uniquely includes two western Sumatran ports among its destinations (see fig. 4).

After 1641, when the VOC captured Melaka with help from its ally Johor, the situation began to change. The Dutch company wished to focus their Southeast Asian trading activity as much as possible on Batavia, so did not attempt to turn Melaka into a major emporium within its empire. However, Johor, which continued to act as the company's ally well into the eighteenth century, was allowed to develop as a trading hub largely without the company's interference. In fact the company facilitated Johor's ascent as the subregion's predominant commercial centre both by eliminating Banten as a competing trading centre in 1682 and by granting passes to Johor-based ships, allowing them to sail through the straits safe from harassment by company patrols.Footnote 69 This is likely why Chen Lunjiong, writing in the 1720s, was only able to offer reasonably accurate descriptions of Johor and Batavia and had little to say about anywhere else in the subregion.

Kathirithamby-Wells has described the other important factor in the consolidation of trade in Johor and other major ports in western Southeast Asia. By the mid-seventeenth century state integration and economic activity had intensified to the point where local rulers of small coastal or riverine centres that had previously served as collection points between production sites and the major subregional emporia were losing their control over trade. Merchants based in the emporia, such as Johor, Batavia, and (until 1682) Banten, were bypassing these smaller collection areas and transporting goods directly to their home ports.Footnote 70 This trend would have encouraged the consolidation of long-distance trade in Johor, and consequently smaller centres on the coast of Sumatra, such as Jambi and Indragiri, would have received far fewer visits from ships based in China, and consequently there would have been far less news available about the current state of these areas for Chen and other scholars who collected information about foreign countries.

Conclusion

This article has attempted to show how knowledge within China of Southeast Asia developed from the sixteenth century to the mid-eighteenth and why. The most basic finding is that the last decades of the Ming dynasty were a high point for Chinese scholarship on the region. Zhang Xie's 1618 Dong xi yang kao provided the most complete picture of contemporary Southeast Asia written in China since the time of the voyages of Zheng He in the early fifteenth century. The unique characteristic of Zhang's work was that it was neither the result of a state-sponsored voyage, as the works produced by the writers who had accompanied Zheng He were, or a geographically agnostic synthesis of older and foreign sources, as many other studies of foreign lands published in the Ming and Qing dynasty had been. The Dong xi yang kao follows the short but path-breaking work of Huang Zhong by relying primarily on the accounts of contemporary Chinese mariners for its information, and is therefore able to provide an array of facts about different ports that were current at the time of its composition.

After the collapse of the Ming dynasty in the mid-seventeenth century and the consolidation of the new Qing state from the 1640s to the 1680s, Chinese scholars began to write about Southeast Asia once again. Some, notably Yu Yonghe in the 1690s and Chen Lunjiong in the 1720s, followed the approach taken by Zhang and produced works based primarily on the observations of contemporary mariners. However, an examination of their writing shows that their descriptions of Southeast Asia were clearly less extensive than Zhang's had been. Many ports were excluded and some areas, especially eastern Java and the Lesser Sunda Islands, were altogether absent.

A reasonable objection to this comparison could be that because the sample size of extant geographic studies using information collected from mariners is so small, it might be that Yu and Chen were simply inferior scholars to Zhang. But when the other available geographic sources, namely rutters and maps, are examined, the same pattern appears in all of them. Ming-era sources describe a much broader geographic vision of Southeast Asia than their early Qing counterparts. In Indochina and the Philippine Islands, the coverage is broadly equal, but the Qing sources have little to say about anywhere in Java or the Lesser Sunda Islands east of Batavia. And in the Straits of Melaka and eastern Sumatra, Johor is identified as the most important centre while other ports are merely noted or are excluded altogether.

The article's final offering is a tentative explanation for the apparent dearth of information in the early Qing sources. The most obvious reason is that the Chinese trading system in Southeast Asia had changed. Because Yu and Chen were relying on interviews with mariners, they could only collect information about places ships were actually travelling to with sufficient regularity. But why were Chinese ships not sailing to anywhere on Java's pasisir or the ports in eastern Sumatra and the Straits of Melaka other than Johor?

In the case of the ports on Java east of Batavia and in the Lesser Sunda Islands, the Dutch VOC seems to have been mostly successful at persuading ships coming from China to stop in Batavia and sail no farther east. The Chinese merchants who wanted access to the eastern archipelago had the option of sailing to another port, Banjarmasin, though. In Banjarmasin, they were able to tap into the expanding trading systems of the Bugis and other groups from Sulawesi at this time, so there was likely no need to risk the Dutch company's ire by attempting to sail the route that ran along the southern littoral of the Java Sea.

In the case of the Straits of Melaka subregion, one possible explanation for the lower number of ports mentioned is Anthony Reid's claim that in about 1680 Southeast Asia's age of commerce came to an end, leading to a decline in engagement with international trade throughout the region. This claim may partly explain the smaller number of ports identified in Qing sources, but an even more compelling hypothesis has been offered by J. Kathirithamby-Wells, who argues that after the VOC's conquest of Melaka, state integration intensified and this resulted in the consolidation of control over the subregional trading network by merchants based in major emporia, allowing them to bypass smaller collection points. By the 1690s, it appears that most of the subregional trade in and around the southern end of the Straits of Melaka was dominated by merchants from Johor and Batavia, so these were the ports to which Chinese ships sailed.