1. Introduction

The variant unit in Matt 16.2b–3 is the lengthiest in Matthew in the apparatus of the current major critical editions of the Greek New Testament. In the NA28 Matt 16.1–4 reads:

Καὶ προσελθόντες οἱ Φαρισαῖοι καὶ Σαδδουκαῖοι πειράζοντες ἐπηρώτησαν αὐτὸν σημεῖον ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ ἐπιδεῖξαι αὐτοῖς. ὁ δὲ ἀποκριθεὶς εἶπεν αὐτοῖς· [ὀψίας γενομένης λέγετε· εὐδία, πυρράζει γὰρ ὁ οὐρανός· καὶ πρωΐ· σήμερον χειμών, πυρράζει γὰρ στυγνάζων ὁ οὐρανός. τὸ μὲν πρόσωπον τοῦ οὐρανοῦ γινώσκετε διακρίνειν, τὰ δὲ σημεῖα τῶν καιρῶν οὐ δύνασθε;] γενεὰ πονηρὰ καὶ μοιχαλὶς σημεῖον ἐπιζητεῖ, καὶ σημεῖον οὐ δοθήσεται αὐτῇ εἰ μὴ τὸ σημεῖον Ἰωνᾶ. καὶ καταλιπὼν αὐτοὺς ἀπῆλθεν.

The major variants for this unit are the ‘shorter reading’, which omits Matt 16.2b–3, and the ‘longer reading’, which includes 16.2b–3. Although most scholars agree in their assessment of the more sizeable variants in Mark 16.9–20 and John 7.53–8.11, no consensus on this variant unit in Matthew has emerged in either the critical editions of the Greek New Testament or in recent major critical commentaries.

The most thorough previous treatment of the textual question was the essay by the late Toshio Hirunuma.Footnote 1 However, no other extensive research on the question has been published in the nearly four decades since Hirunuma's helpful research. This essay goes beyond Hirunuma's work by exploring the current state of research, assembling significantly more manuscript data, carefully considering the evidence of the Eusebian apparatus in various early manuscripts, and thoroughly scrutinising various proposals for the causes of variation.

2. Current State of Research

F. B. Westcott and F. J. A. Hort as well as Kurt and Barbara Aland expressed certainty that the longer reading was an early scribal interpolation.Footnote 2 Constantin von Tischendorf, NA28 and UBS5 enclose the longer reading in square brackets in the main text.Footnote 3 The brackets in the NA28 indicate that the variant is the ‘preference of the editors’ even though ‘textual critics today are not completely convinced of the authenticity of the enclosed words’.Footnote 4 These brackets ‘always reflect a great degree of difficulty in determining the text’.Footnote 5 The UBS5 placed a C rating on the bracketed text.

Although Bruce M. Metzger was probably correct when he noted in 1994 that ‘most scholars regard the passage [Matt 16.2b–3] as a later insertion’,Footnote 6 examinations by both editors of the Greek New Testament and commentators over the last three decades have often led to different conclusions. The SBLGNT and the Tyndale House Greek New Testament print the longer reading as the main text. Of the twenty-six major commentaries treated in Table 1, ten argue that Matt 16.2b–3 was probably original, ten see the variant as a scribal interpolation, and six were unable to make a decision based on the evidence currently available.Footnote 7 Each of these commentators attempted to establish the original text through an approach that falls within the broad category of reasoned eclecticism.

Table 1. Critical Commentaries in English and German Published since 1968

This brief survey of the current state of research shows that whatever consensus may have existed in the late twentieth century has unravelled over the last few decades. The present article will offer a fresh appraisal of this perplexing variant unit.

3. External Evidence

Tables 2 and 3 show evidence from continuous text Greek manuscripts for the longer and shorter readings of Matt 16.2, assigning these manuscripts to the five major categories of texts utilised by Kurt and Barbara Aland and categorised by century.Footnote 8 Unfortunately, all of the early papyri currently published that contain portions of Matthew (𝔓1 𝔓19 𝔓21 𝔓25 𝔓35 𝔓37 𝔓44 𝔓45 𝔓53 𝔓62 𝔓64–67 𝔓70 𝔓71 𝔓73 𝔓77 𝔓83 𝔓86 𝔓96 𝔓101 𝔓102 𝔓103 𝔓104 𝔓105 𝔓110) are lacunose at this point.

Table 2. Manuscripts Supporting the Shorter Reading

Table 3. Manuscripts Supporting the Longer Reading

3.1 Sigla

Important features of several of the manuscripts betray an awareness of the different readings. Although Codex E has the longer version of the text, this text is marked with asterisks which show that a scribe or reader doubted this longer reading was original.Footnote 9 Minuscules 566 and 1424 also contain the longer reading but mark it with asterisks.

3.2 Misplacement

Although minuscule 579 is listed in NA28 as a witness to the shorter reading, it preserves the longer reading also. However, the scribe replaced the ἐλάβετε at the end of Matt 16.10 with ἐλάβεται (in agreement with W and 2) and inserted the longer reading (16.2b–3) between 16.10 and 11 (a singular reading).

3.3 Commentary

Although Codex X omits 16.2b–3, the accompanying commentary treats the omitted material, showing that both the longer and shorter readings were known to the scribe. A careful comparison of the commentary with Chrysostom's homilies on Matthew confirms F. H. A. Scrivener's claim that the commentary was derived from Chrysostom.Footnote 10 The commentary in X agrees almost verbatim with 102 out of 118 words of Chrysostom's homily in the order in which they appear in Chrysostom.

3.4 Eusebian Apparatus

Matt 16.2b–3 was clearly present in the Greek text utilised by Eusebius in the early fourth century in the development of his section and canon numbers. Eusebius assigned to these verses the section number 162 (ρξβ) and the canon number 5 (ε), indicating that the verses had a parallel in section 161 of Luke (12.54–6).

An examination of the Eusebian apparatus in dozens of manuscripts shows that manuscripts that have the shorter reading typically exhibit confusion in the canon and section numbers. Although the apparatus is remarkably consistent in manuscripts with the longer reading, scribes whose manuscripts have the shorter reading do not know quite what to do with the Eusebian section numbers. Some manuscripts bump the section number earlier and others later. Some completely skip the section number that originally accompanied the longer reading. Some assign two different section numbers to a single verse and even a single line. Careful examination shows that several of these manuscripts have erasures and reassignments in the Eusebian apparatus. Furthermore, the manuscripts with the shorter reading often assign incorrect canon numbers to their reordered sections. Scribes were clearly changing the Eusebian system and they lacked the skill that Eusebius himself displayed in developing the original form of the apparatus.

Codex Sinaiticus contains these Eusebian section and canon numbers but omits 16.2b–3. Consequently, each subsequent section number is mistakenly reduced by one. Although 16.4 should be section number 163, 16.4 is treated together with 16.2a as part of section 162. Although 16.6 and 16.7 should be 164 and 165 respectively, they are marked as 163 and 164 respectively.

One may wonder if the scribe who inserted the section and canon numbers was familiar with an earlier system of Eusebian sections that was based on a text that lacked 16.2b–3. Two pieces of evidence make this view highly improbable. First, the canon numbers assigned in א are correct for 16.6 (2) and 16.7 (4). However, the canon number assigned to 16.2 (5) is incorrect. Since Sinaiticus lacks 16.2b–3, the canon number should be 6 as in E and Y, indicating that 16.4, which constitutes the bulk of this section, is paralleled by Mark 8.12.Footnote 11 The use of canon number 5 seems to be influenced by an apparatus based on the inclusion of 16.2b–3.

Second, Dirk Jongkind has noted that the scribe made a correction at his section 163 (Matt 16.6) by changing an initial canon number 6 (ϛ) to 2 (β). The scribe erased the upper right portion of the stigma (though traces of the stigma are still clearly visible upon close inspection of the codex) and incorporated the remaining portion into the beta. This modification suggests that the scribe was using an exemplar in which section 163 marked 16.4. The canon number 6 indicated that the section was paralleled by section 78 of Mark (Mark 8.12). But since the scribe now moved the section number 163 to Matt 16.6 (which is paralleled by Mark 8.15 and Luke 12.1), he or she necessarily corrected the canon number to 2 to identify the different parallel texts. Based on this evidence, Jongkind concluded, ‘The confusion suggests that the Eusebian apparatus of Sinaiticus is taken from a manuscript that included verses 2b–3.’Footnote 12

Other manuscripts that contain the shorter reading are similarly characterised by confusion in the Eusebian apparatus, as Table 4 illustrates. The inconsistency in the Eusebian apparatus in the early section of Matt 16 in the manuscripts that contain the shorter reading does not appear to be characteristic of the apparatus as a whole in these manuscripts. The manuscripts with the shorter reading that have anomalies in the Eusebian apparatus in the first few verses of Matt 16 show remarkable consistency elsewhere. For example, almost all (V Y 124 157 174 788 1045) agree in assigning the number 183 to Matt 18.15 and all of the manuscripts that include the canon number (V 124 174 788) agree in assigning the text to canon 5 (ε). Only Γ departs from this group by assigning 184 to 18.15. Similar results emerge from an examination of Matt 12.38. Almost all (Y Γ 124 174 788) agree in assigning 127 to the sectionFootnote 13 and the manuscripts that assign canon numbers (V Y Γ 124 174 788) agree without exception in assigning the section to canon 5. Codex V departs from this group by assigning 126 to this section and apparently skipping section 127 entirely, and 157 differs by assigning 128 to the section.

Table 4. Anomalies in the Eusebian Apparatus with the Shorter Reading

* If one limits §162 to Matt 16.2a, the section has exact parallels in Mark 6.37; 10.3; Luke 8.21; 10.27; 15.29; and many other close parallels (Mark 11.14; 14.48; Luke 4.8, 12; 5.22, 31; 6.3; 7.22, 40; 10.41; 13.42; 14.3; 19.40; 20.3).

With the exception of D, manuscripts with the longer reading are remarkably consistent in assigning the section number 162 to Matthew 16.2. These include G L M S U Θ Π Ωvid 1 3 22vid 118 150 209 233 566 1110 1230 1338 1340vid 1341 1342 1343 1421 1424 1500 1514 1602 1675 2193 2372 2546. Majuscule Η and minuscules 1333 2786 assign the section number 163.Footnote 14 The vast majority of these manuscripts assign the canon number 5 to the section. These include G L M S U Π 3 118 150 233 566 1110vid 1230 1343 1346 1421 1424 1500 1514 2193. Codex E assigned the canon number 6 (ϛ), but this is a careless error since the scribe correctly identified Luke 12.54–6 as the parallel in a note in the bottom margin.

The modifications to the Eusebian apparatus in the manuscripts that contain the shorter reading lead to several important conclusions. First, the agreement of the two earliest extant majuscules on the shorter reading is mitigated by the realisation than an exemplar of א must have contained the longer reading. Thus, as far as one can tell from the evidence of the Greek manuscripts, the two readings are of approximately equal antiquity. Second, the very inconsistent modifications to the Eusebian apparatus in the manuscripts that contain the shorter reading suggest that copyists were utilising exemplars that contained the longer reading, choosing to omit the longer reading, and then independently revising the Eusebian apparatus to accommodate this loss. If early manuscripts that contained the apparatus preserved the shorter reading, one would expect greater consistency among these manuscripts in the modifications of the apparatus. Consequently, the shorter reading is a result of the scribe's conscious decision to omit the longer reading.

3.5 Versions

The longer reading is supported by old Latin texts (a, aur, b, c, d, e, f, ff1, ff2, g1, l, q), the Vulgate, Syriac texts (both Peshitta and Harklensis),Footnote 15 some Bohairic Coptic texts, and the Ethiopic, Georgian and Slavonic versions. The shorter reading is supported by old Syriac (c and s), and Sahidic, Middle EgyptianFootnote 16 and some Boharic Coptic texts.

Alexander Souter claimed that Tatian's Diatessaron supported the longer reading.Footnote 17 However, this is far from certain. The Arabic harmony leaps from Matt 16.1a to 16.4b but inserts 16.2b–4a between Luke 12.55 and Matt 12.22.Footnote 18 Ephrem's Commentary on the Diatessaron does not treat 16.2b–3, nor is the passage mentioned in his Hymns.Footnote 19 However, this does not necessarily mean that Ephrem's copy of the Diatessaron did not contain the longer reading since he does not comment on any portion of Matt 16.1–12 in his commentary.Footnote 20 The one possible allusion to Matt 16.1–4 is in Ephrem's first hymn on Jonah that refers to Matt 12.38–41 or 16.4, ‘The servant [Jonah] bore the symbols of his Lord in his conception and his birth and in his raising to life.’Footnote 21 The one potentially helpful Western witness to the Diatessaron, Codex Fuldensis, begins chapter 90 with Matt 16.4. It lacks Matt 16.1–3 and Luke 12.54–5. The presently available evidence conflicts and is insufficient to determine the reading of the Diatessaron. The editors of the UBS text were wise to drop appeal to the Diatessaron as a witness to the longer reading.Footnote 22

3.6 References in Early Christian Literature

Since none of the early papyri contain this portion of Matthew, potential witnesses to the state of the text in the second and third centuries may be especially important. Unfortunately, the Apostolic Fathers make no reference to Matthew 16.1–4.Footnote 23 However, scholars have identified three other potential sources of information that may be helpful for reconstructing the early history of transmission.

Subscriptions in thirty-eight Gospel manuscripts from the ninth to the thirteenth century refer to a work called τὸ Ἰουδαϊκόν (Jewish Gospel).Footnote 24 Five gospel manuscripts preserve thirteen different readings from the Judaikon in notes in the margin of Matthew. Minuscule 1424 (ninth or tenth century) contains the largest number of references to the Judaikon, ten of the known references. This manuscript marks Matt 16.2b–3 with asterisks and adds the marginal note: τὰ σεσημειομένα διὰ τοῦ ἀστερίσκου ἐν ἑτέροις οὐκ ἐμφέρεται οὐτε ἐν τῷ Ἰουδαϊκῷ (‘The things marked by use of the asterisk are not contained in other manuscripts nor in the Jewish Gospel’). The Judaikon was apparently based on the Greek Matthew and is a potentially early witness to the text. Unfortunately, the presently available evidence is not sufficient to establish a firm date of composition for the Judaikon. Furthermore, absence of the content of Matt 16.2b–3 from the Judaikon does not necessarily attest to the absence of these verses from the copy of Matthew known to the author of the Judaikon since the Judaikon was clearly a revision of Greek Matthew and may have abridged Matthew at many points.

In the mid-second century, Justin Martyr (Dial. 107.1) refers to Matthew 16.1–4. Justin's quotation leaps from a paraphrase of 16.1–2a to 16.4 and could be regarded as evidence against the inclusion of vv. 2–3. However, this is uncertain.Footnote 25 Justin paraphrases Matthew 16.1–2a in a manner that gives no indication that he intended to include a strict quotation of the passage until 16.4. Until 16.4, only two words, σημεῖον and αὐτοῖς, are taken directly from Matt 16. More importantly, the context demonstrates that Justin's purpose was to demonstrate that Jesus’ resurrection was predicted in the Scriptures and a quotation of 16.2b–3 would not have contributed to this defence of the resurrection.

Tischendorf's apparatus identified Theophilus of Antioch as a witness to the longer reading.Footnote 26 Theophilus’ only extant work is Ad Autolycum, which he wrote in the late second century. However, no efforts to locate a reference to Matt 16.1–4 by translators of Theophilus’ work have been successful.Footnote 27 Thus Tischendorf appears to have been in error.Footnote 28

In the mid-third century (ca. 246–8), Origen's commentary on Matt 16.1–5 (12.1–4) shows no knowledge of the longer reading. Origen's silence is generally regarded as the earliest witness to the shorter reading.Footnote 29 Such a conclusion is questionable, however, since Origen omits words, clauses and whole verses in the Scripture citations in the Matthew commentary.Footnote 30 Furthermore, a detailed study of the nature of Origen's text of Matthew has confirmed Hort's theory that Codex 1 most closely resembled Origen's text and discovered that 1582 was also remarkably similar.Footnote 31 Yet both of these manuscripts contain the longer reading. This raises the possibility, perhaps even the probability, that Origen's text contained the longer reading but he simply did not deem the details of the reading worthy of further comment.

In the fourth century, several writers allude to or comment on Matt 16.2b–3, including the Spanish poet Juvencus (Evangelicae historiae 3.224–30), Hilary of Poitiers (Commentary on Matthew), Basil of Caesarea (Hexaemeron 6.4), and John Chrysostom (Hom. Matt. 53.3). None of these writers mention manuscripts that lack 16.2b–3. However, in the early fifth century, Jerome's Comm. Matt. 3.16 (16.2f.) claims that the verses were absent in most manuscripts available to him (hoc in plerisque codicibus non habetur).Footnote 32 Augustine's Quaestiones in evangelium Matthaei focuses question 20 on the meaning of 16.2b–3 thereby confirming that his text contained the longer reading, even though his commentary on the harmony of the Gospels skipped from Matt 15.39 to 16.4.Footnote 33

The evidence from early Christian literature is of limited value for establishing the earliest recoverable text. On one hand, the statement by Jerome seems to be corroborated by the fourth-century majuscules ℵ and B. Yet the literature mitigates this evidence to some extent by demonstrating that manuscripts with the longer reading had a wide geographical distribution by the fourth century.

4. Internal Evidence

4.1 Intrinsic Probability

4.1.1 Presence of Mattheanisms

Robert Gundry argued persuasively that Matt 16.2b–3 contains Mattheanisms that suggest that the longer reading was original. First, the discussion of the meteorological signs in Matthew was characterised by extensive parallelism such as the parallel between evening and morning, fair weather and stormy weather and discerning the face of the sky but not the signs of the times. Such parallelism ‘typifies Matthew's style’. Second, the differences between Matt 16.2b–3 and Luke 12.54–6 exhibit diction characteristic of Matthew. The genitive absolute ὀψίας γενομένης not only occurs three times in double tradition material, but is also found twice as an insertion by Matthew and once in his unique material. Other features such as the absence of the recitative ὁτι and εὐθέως and the use of favourite terms such as οὐρανός and σήμερον exhibit Matthean preferences. Although Matt 16.3 and Luke 12.56 have the same basic sense, the version in Matthew reflects his favourite vocabulary. Luke's δοκιμάζειν is matched by Matthew's διακρίνειν. Matthew inserts words from the κρι- word group eleven times in the paralleled material in his Gospel. Finally, the version in Matthew mentions evening before morning, which seems to reflect the Jewish view of the day in which the day begins in the evening.Footnote 34 A later scribe would probably not have been capable of imitating Matthew's style so well.

4.1.2 Unusual Stylistic Features

Theodor Zahn, A. H. McNeile and Erich Klostermann pointed to one stylistic feature that seemed inconsistent with the authenticity of the longer reading.Footnote 35 Matt 16.3 is the only text in Matthew or the New Testament that uses γινώσκω with the complementary infinitive to mean ‘to know how to …’ However, in Matt 7.11 the verb οἶδα with the infinitive was used in this same sense, and Matthew uses γινώσκω in instances in which parallel texts use οἶδα (compare Matt 7.23 and Luke 6.27; Matt 22.18 and Mark 12.15). Since Matthew seems to treat the two verbs as synonyms and use them interchangeably, the construction in 16.3 is not inconsistent with Matthean composition.

4.1.3 Presence of Rare Vocabulary

Some scholars have suggested that the presence of rare and potentially late vocabulary in the longer reading supports the view that the longer reading is a scribal interpolation. Hirunuma claimed that, outside Matt 16.2, πυρράζω appears only in Byzantine writers.Footnote 36 Matthew would have been expected to use the related term πυρρίζω that appears in the Septuagint and Philo.Footnote 37

Several lines of evidence suggest that Matthew may have coined the term. First, the external evidence (C D W) confirms that the term appeared in texts of Matthew prior to the fifth century, and the evidence from Eusebius pushes the terminus ad quem for the origin of the term to the late third century. Second, Hellenistic Greek writers often converted adjectives ending in -ος into intransitive verbs by adding the -αζω suffix.Footnote 38 Third, Matthew possibly coined the term παρομοιάζω in 23.27 since this passage contains the first documented usage of it.Footnote 39 If Matthew used the -αζω suffix to create this verb from παρόμοιος (an adjective used by Herodotus and Thucydides), he could just as easily have created the verb πυρράζω.

Some scholars have objected to the longer reading on the grounds that in the Septuagint and New Testament the verb στυγνάζω is used of human emotion rather than a description of overcast skies.Footnote 40 This argument fails to consider that the related noun στυγνότης is used as early as the second century bce by Polybius to describe the gloomy appearance of the sky (ψυχρότητα καὶ στυγνότητα, ‘cold and gloomy atmospheric conditions’).Footnote 41 The related adjective στυγνός was used to describe a gloomy night in the Septuagint (Wis 17.5). The meaning of the related noun and adjective in works written prior to the composition of Matthew's Gospel demonstrates the plausibility of a first-century author using the verb στυγνάζω to refer to cloudy skies.

4.1.4 Relationship to Context

Several scholars have supported the shorter reading because the longer ending is believed to fit awkwardly with the surrounding context or have internal tensions. R. T. France argued that the shift from the second person plural in 16.2b–3 to the third person singular in 16.4 suggested that the longer reading was an interpolation.Footnote 42 However, such shifts in person and number occur elsewhere in Matthew and in contexts without any significant textual variation. Matt 12.36–7 shifts from the second person plural to the third person plural and then again to the second person singular. More importantly, in Matt 23.35–6 Jesus described the scribes and Pharisees using the second person plural and then describes them as ‘this generation’ (τὴν γενεὰν ταύτην) in a manner comparable to the shift from the longer reading to Matt 16.4.

On the surface, the shift from the request for a ‘sign from heaven’ (Matt 16.1) to a discussion of the ‘signs of the times’ (Matt 16.3) might seem to be an abrupt change in topic raising suspicions that the latter phrase is part of an insertion. However, in Matt 24.3 the disciples pose a question about τὸ σημεῖον τῆς σῆς παρουσίας καὶ συντελείας τοῦ αἰῶνος which Jesus appears to identify later as τὸ σημεῖον τοῦ υἱοῦ τοῦ ἀνθρώποῦ ἐν οὐρανῷ (Matt 24.30). Since Jesus elsewhere identifies an eschatological sign as a sign ‘in heaven’, the association of a request for a sign ‘from heaven’ with ‘signs of the times’ seems fully consistent with Matthean style.

Some scholars have argued that the use of the verb πυρράζω as both a sign of fair weather and a storm creates an internal tension in the longer reading and have proposed emending the text to remove this tension.Footnote 43 One could argue that the tension is an indication that the longer reading is an interpolation. Although the tension might be only imagined since the longer reading refers to the colour of the sky at different times of the day, this explanation is not fully satisfactory, since R. Pappa described the sun (and thus the sky) as ordinarily red at both sunrise and sunset.Footnote 44 However, the fact that the second use of πυρράζω is accompanied by the participle στυγνάζων (‘be gloomy, overcast’) distinguishes it sharply from the earlier usage. Some scholars have objected that the sky cannot be red and overcast at the same time. However, Aratus also stated that a rising sun draped by both black and red was a sign of impending rain and high winds.Footnote 45 Any apparent tension is also eased if the participle denotes the early stage of a process, ‘The sky is red and is becoming overcast.’

4.2 Transcriptional Probability

4.2.1 Unintentional Change

Few scholars have suggested that the variant was caused by an unintentional scribal change. John Nolland posited that the omission of the longer reading may have resulted from haplography due to parablepsis. The eyes of the scribe leapt from the γεν in γενομένης 16.2b to the γεν in γενεά: [ὀψίας γενομένης λέγετε· εὐδία, ……] γενεὰ πονηρὰ.

This explanation is complicated by the placement of the ὀψίας before γενομένης. Since the omission includes ὀψίας, the scribe would probably have initially written ὀψίας, then jumped accidentally to γενέα, then recognised that ὀψίας now made no sense and decided to erase it without consulting his exemplar. It seems much more probable that a scribe who committed haplography in this instance (or his corrector) would have consulted his exemplar rather than casually erasing the dangling ὀψίας.

4.2.2 Intentional Change

It is more likely that a scribe intentionally interpolated the longer reading from another source or intentionally deleted the longer reading.

4.2.2.1 Assimilation to Luke 12.54–6

Scholars have suggested that early scribes inserted the reference to meteorological signs to assimilate Matthew to Luke 12.54–6. Although the two passages agree verbatim in five words (λέγετε, τὸ πρόσωπον … τοῦ οὐρανοῦ), the two passages have far more differences than similarities. Jesus’ words in Matthew are addressed to the scribes and Pharisees, but in Luke they are addressed to the crowds. In Matthew the meteorological signs are related to the colour of the sky at different times of day, but in Luke they are related to cloud formation and wind direction.Footnote 46 To argue that the early scribe who assimilated Matthew to Luke also adapted the Lucan passage to better conform to meteorological conditions known by his readers would be unpersuasive, since no trace of similar adaptations in Luke's Gospel are preserved in extant witnesses.

Since the longer reading is not likely the result of an assimilation to Luke and since it contains important traces of Matthew's style which an early scribe would not like have been capable of mimicking so well, intentional omission is more likely. Scholars have suggested two possible motivations for an intentional omission.

4.2.2.2 Inapplicable Meteorological Signs

Davies and Allison, Blomberg, Gundry, Keener, Nolland, Osborne and Carson have followed earlier scholars such as Scrivener in arguing that scribes omitted 16.2b–3 because the meteorological signs did not apply to their climate. Some scribes may have thought the omission necessary to prevent readers from wrongly dismissing Jesus’ perfect knowledge and infallibility that extends even to his description of weather indicators.

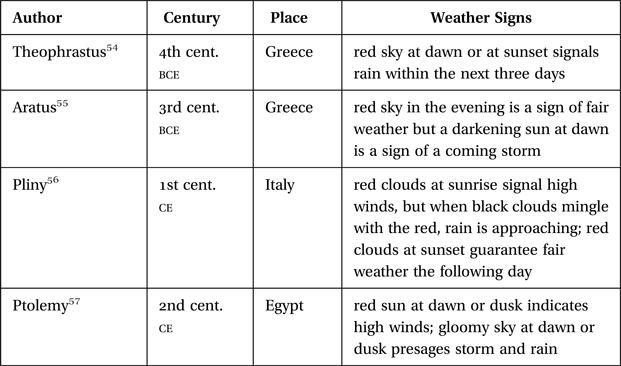

The signs in Matt 16.2b–3 belong to the system of ancient weather prediction known as Theophrastan meteorology. A brief survey of similar statements from classical antiquity (see Table 5) is necessary if one is to judge how the longer reading might have been viewed in the broader Mediterranean world.Footnote 47

Table 5. Ancient Statements of Weather Prediction

Although the weather signs in the longer reading were widely accepted,Footnote 48 the survey in Table 5 shows that they were not universally accepted or obvious. The weather signs in Matt 16.2b–3 agree with those discussed by Aratus and by Pliny. However, the reference to a red evening sky as a sign of fair weather clearly contradicts the signs discussed by Theophrastus (though Theophrastus admitted that the sign was not entirely reliable) and possibly also the sign described by Ptolemy. Ancient scribes familiar with Theophrastus’ influential treatise or Ptolemy's work or those who had independently made similar observations might have chosen to omit the reference to the meteorological signs due to real or perceived conflicts with these sources or observations. Both Theophrastus and Ptolemy pointed out that the specific location of an observer played a crucial role in the interpretation of weather signs and that principles of weather prediction could not be applied universally.Footnote 49

Although this explanation is initially persuasive, further investigation raises serious doubt. The meteorological indicators in Matt 16.2b–3 are more widely applicable than those in Luke 12.54–6, since those in Luke assume a location directly to the east of the Mediterranean Sea.Footnote 50 However, no manuscripts omitted the Lucan passage or significantly revised it in a manner that would universalise the meteorological signs.

Plausible explanations for the textual stability of Luke 12.54–6 in contrast to the omission in Matt 16.2b–3 can be offered. For example, the wider distribution of the very popular Gospel of Matthew at an earlier period may have resulted in modifications to the Matthean text that Luke's text did not experience. Yet the apparent acceptance of Luke's reference to meteorological signs even though they were specific to Palestine poses serious difficulties for the commonly held view that the longer reading in Matthew was deleted out of meteorological concerns in regions remote from Palestine.

4.2.2.3 Assimilation to Matt 12.39 or Mark 8.11–13

Davies and Allison, Blomberg, Gundry and Osborne have argued that some scribes omitted 16.2b–3 in order to assimilate 16.1–4 to Mark 8.11–13.Footnote 51 Scrivener, Tregelles and Weiss argued that the longer reading was omitted in order to conform 16.1–4 to Matt 12.38–39.Footnote 52Table 6 shows the similarities between these parallels.

Table 6. Matthew 16.2a, 4 and Synoptic Parallels

Of these two options, Scrivener's hypothesis is more probable. Matt 16.2a, 4 shares 21 words in common with Matt 12.39 in a shared order without any deviation and differs only by the absence of τοῦ προφήτου. It shares only six words in common with Mark 8.11–13 (71 per cent less than Matt 12.39) and thirteen with Luke 11.29 (38 per cent less than Matt 12.39). Thus the omission of the longer reading brought Matt 16.1–4 into nearly perfect agreement with the passage already familiar to the scribe from his copying of the earlier portions of the Gospel.

5. Conclusion

The difficulty of evaluating the variants in Matt 16.2–3 was summarised well by Joachim Gnilka, who referred to the unit as ‘ein fast nicht lösbares Problem’.Footnote 53 However, this investigation has led to several discoveries that support the longer reading. Since Origen is not the clear witness to the shorter reading he has been generally assumed to be, the earliest witness to this reading is Vaticanus. Yet Sinaiticus used an exemplar that contained the longer ending and this exemplar was likely either contemporary with or even earlier than Vaticanus. As far as one can tell from the manuscript evidence, the two readings are of equal antiquity.

The longer reading is not likely to be an insertion by an early Christian scribe since it contains features of Matthean composition which few scribes would have been able to imitate. Furthermore, the adjustments made to the Eusebian apparatus in manuscripts with the shorter reading suggest that the scribes who produced these manuscripts had exemplars with the longer reading and yet chose to remove or omit it. They then independently revised the Eusebian apparatus in inconsistent ways in order to accommodate this change. The intentional removal of the longer reading probably had one of two motivations: (1) these scribes had access to another exemplar that contained the shorter reading or (2) they chose to remove the longer reading due to other concerns. The most plausible motivation for removal is assimilation to Matt 12.39.