Peru is replete with geoglyphs produced over the last 4,000 years (Guffroy Reference Guffroy1999; Hostnig Reference Hostnig2003) depicting anthropomorphic, zoomorphic, and geometric figures created either through subtractive or additive techniques or by combining both methods. The subtractive technique produces the desired motif by clearing the ground of rocks and exposing the underlying lighter-colored soil. The additive technique rearranges rocks to outline the motif and highlight specific features (Gálvez Mora et al. Reference Gálvez Mora, Castañeda Murga, Runcio, Espinoza Córdova, de Haro, Rocchietti, Runcio, de Lara and Fernández2012). The Nasca Lines in southern Peru are some of the best known and most studied prehispanic geoglyphs. They have been linked to ritual practices, water resources, and celestial bodies (Masini et al. Reference Masini, Orefici, Rojas, Lasaponara, Masini and Orefici2016). Fewer geoglyphs are known from other parts of the Andean region, and relatively little is known about this art form in northern Peru (Alva and Meneses de Alva Reference Alva and de Alva1982; Corcuera Cueva and Echevarría López Reference Corcuera Cueva and López2010, Reference Corcuera Cueva and López2011; Gálvez Mora et al. Reference Gálvez Mora, Castañeda Murga, Runcio, Espinoza Córdova, de Haro, Rocchietti, Runcio, de Lara and Fernández2012; Hostnig Reference Hostnig2003:195–216; Wilson Reference Wilson1988). This report focuses on a group of five geoglyphs identified as part of an archaeological survey in the Carabamba Valley in northern Peru.

The Carabamba Valley

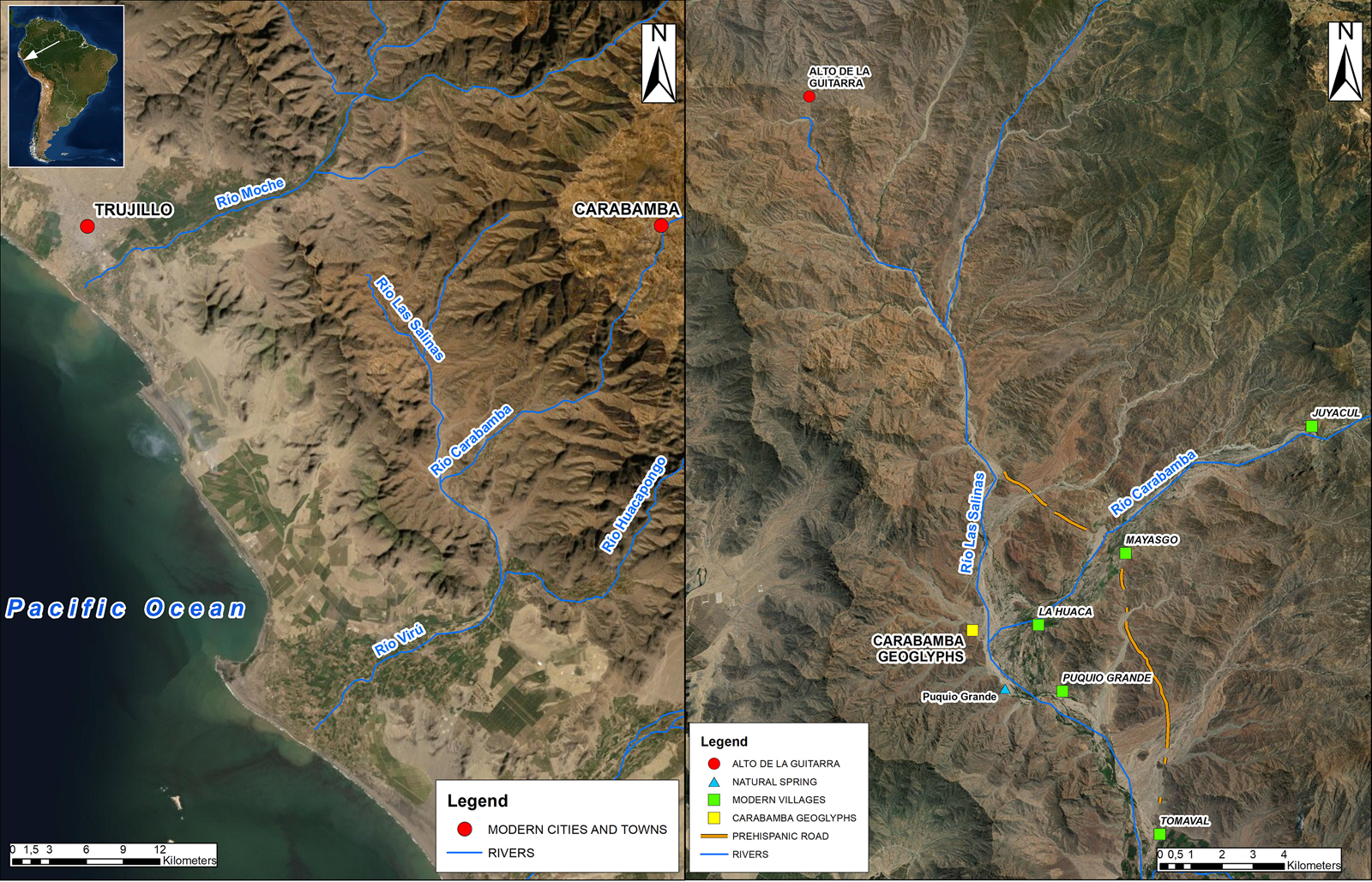

The Carabamba Valley originates near the modern town of Carabamba (3,325 m asl, province of Julcán in the department of La Libertad) and eventually merges with the Huacapongo Valley near the village of Tomaval (150 m asl, province of Virú in the department of La Libertad) to form the Virú Valley (Figure 1). The area located between 150 and 1,000 m asl is arid, and rainwater flows intermittently on the riverbed during the austral summer (December to March). Between 1,000 and 3,000 m asl, the climate is slightly more humid, sustaining bushes and trees. Above this zone extends the extensively farmed Carabamba Plateau (Oficina Nacional de Evaluación de Recursos Naturales 1973). The Carabamba Valley is a natural corridor that has connected the coast to the highlands and the people who inhabited these lands for millennia.

Figure 1. Left, location of the Carabamba River valley; right, location of the geoglyphs (Province of Virú) and of the other features mentioned in the text (maps made by Amedeo Sghinolfi on ESRI ArcGIS). (Color online)

Despite its key role during prehispanic times, very little research has been carried out in this area (Briceño and Fuchs Reference Briceño and Fuchs2009; Topic and Topic Reference Topic and Topic1982; but see studies of petroglyphs near the caseríos of Mayasgo and Juyacul: Castillo Benitez and Barrau Reference Castillo Benitez and Barrau2016; Van Hoek Reference Van Hoek2017, Reference Van Hoek2018). A survey of the area was carried out by the authors between April and December 2019 to identify and map archaeological sites, reconstruct settlement patterns, and document interactions between ancient human groups. We identified five unreported geoglyphs near the villages of La Huaca, Puquio Grande, and Mayasgo that shed light on the Formative period occupation of the area.

The Five New Geoglyphs

This group of geoglyphs extends over an area of 0.1 km2 at the confluence of the Carabamba and Las Salinas Rivers (290 m asl) on the eastern slope of Cerro Misia (Figure 2a). Las Salinas is a seasonal river that connects this part of the Virú basin to the middle Moche Valley through a stretch of land known as Alto de la Guitarra, where several petroglyphs have been identified (Castillo Benitez and Barrau Reference Castillo Benitez and Barrau2014; Disselhoff Reference Disselhoff, Disselhoff and Krieger1955). The geoglyphs were mapped using a lightweight drone (DJI Mavic Pro Platinum) that captured high-resolution pictures (12.35 megapixels; 26 mm focal length) from a range of altitudes (15–90 m). Vertical (90°) photographs were taken at regular time intervals (2 seconds) to ensure enough overlap (75% forward, 60% side overlap). High-quality georeferenced orthophotos and 3D models were subsequently created using Agisoft Metashape and MeshLab software.

Figure 2. (a) Place where the Carabamba (on the right) and the Las Salinas (on the left) Rivers meet; (b) the ravine that features Geoglyphs 2–5 (photographs by Amedeo Sghinolfi). (Color online)

Geoglyph 1 is located on an eastern-facing slope, 150 m from the confluence of the Las Salinas and Carabamba Rivers, and faces the highlands (Figure 3). The geoglyph (52 × 58 m) includes different motifs made with additive and subtractive techniques. The main figure is a warrior who faces a spotted cat, perhaps a jaguar (Panthera onca). Outlined with rocks, the warrior wears a long braid and holds a sacrificial knife (tumi) and a war mace (porra) or spear. Two ornaments hang from a waistband, one of which possibly represents a snake (right). Two barely visible anthropomorphic figures can also be seen: one (13 × 7 m) below the feline and the other (6.80 × 2.75 m) next to the warrior's forehead. The site also features a small, rounded structure (diameter, 3.75 m) 10 m northeast of the warrior, as well as others 150 m south of the geoglyph.

Figure 3. (a) Photograph of Geoglyph 1; (b) drawing of Geoglyph 1 (photograph by Amedeo Sghinolfi, drawing by Jeisen Navarro Vega). (Color online)

Geoglyphs 2 through 5 are located in a narrow canyon (quebrada) 560 m south of Geoglyph 1 (Figure 2b) and 280 m southwest of the river. Geoglyph 2 (8.5 × 1.0 m) is on a flat area, was made with additive (head and part of the tail) and subtractive (end of the tail) techniques, and features a snake or a tadpole facing the highlands (Figure 4). Geoglyph 3 is located on an eastern-facing slope 550 m southwest of the river. It was made using the subtractive technique and is the largest (88 × 45 m) geoglyph of the group (Figure 5). It includes a bird-like motif and a head or half-moon design, as well as horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines (heavily eroded). Originally, this geoglyph would have stood out in this isolated quebrada, acting as the focal point of this sacred landscape. Geoglyphs 4 and 5, made with the subtractive technique, are located on the bottom of the quebrada between Geoglyphs 2 and 3 (Figure 6). Geoglyph 4 (11.5 × 9.5 m) depicts a camelid, whereas Geoglyph 5 (13.0 × 7.5 m) features a spiral motif. The tip of the spiral points toward a nearby hill, while the head of the camelid faces the confluence of the Las Salinas and Carabamba Rivers. Remnants of possible geoglyphs are also visible on a hillslope located 290 m to the southeast, but the area is heavily disturbed by modern path making (Figure 7).

Figure 4. (a) Photograph of Geoglyph 2; (b) drawing of Geoglyph 2 (photograph by Amedeo Sghinolfi, drawing by Jeisen Navarro Vega). (Color online)

Figure 5. (a) Photograph of Geoglyph 3; (b) drawing of Geoglyph 3 (photograph by Amedeo Sghinolfi, drawing by Jeisen Navarro Vega). (Color online)

Figure 6. (a) Photograph of Geoglyph 4 (right) and 5 (left); (b) drawing of Geoglyph 4 (right) and 5 (left) (photograph by Amedeo Sghinolfi, drawing by Jeisen Navarro Vega). (Color online)

Figure 7. Possible geoglyphs located southeast of Geoglyphs 4 and 5 (photograph by Amedeo Sghinolfi). (Color online)

Discussion

We found no ceramic sherds on the surface of those prehispanic sites, which makes dating difficult. However, the warrior depicted in Geoglyph 1 is clearly associated with Formative period iconography. The warrior shows striking similarities with the human figures carved on the stelae from the Chavín heartland (Burger Reference Burger1982; Lumbreras Reference Lumbreras1977), with rock paintings and petroglyphs from Poro Poro in the department of Cajamarca (del Carpio Perla et al. Reference del Carpio Perla, Fulle and Gamarra2001) and Huaca Partida in the Nepeña Valley (Shibata Reference Shibata2017), and with petroglyphs from Alto de la Guitarra in the middle Moche Valley (Castillo Benitez and Barrau Reference Castillo Benitez and Barrau2014; Disselhoff Reference Disselhoff, Disselhoff and Krieger1955) and Palamenco in the Lacramarca Valley (Guffroy Reference Guffroy1999:100). The warrior also resembles the Sechín Alto Complex stone carvings (Bischof Reference Bischof1994:Figure 7). The other geoglyphs are harder to date. They could date from earlier times or from a later period when the area close to the river started to be occupied more intensively (ca. 400 BC). According to Corcuera Cueva and Echevarría López (Reference Corcuera Cueva and López2010:44–46), the later geoglyphs in the Quebrada Santo Domingo (Moche Valley) were made with the subtractive technique and featured geometric motifs, whereas earliest geoglyphs were made with the additive technique. It is unclear whether a similar chronology exists in the Carabamba Valley (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Location of the sites mentioned in the text (map made by Amedeo Sghinolfi on ESRI ArcGIS). (Color online)

The geoglyphs may have been associated with an inland north–south road running from the Moche to the Chao Valley, which likely started to be used during the Formative period (Beck Reference Beck1979; Van Hoek Reference Van Hoek2018; see also Gálvez Mora et al. Reference Gálvez Mora, Castañeda Murga, Runcio, Espinoza Córdova, de Haro, Rocchietti, Runcio, de Lara and Fernández2012:101–104, Figure 8). However, they are also associated with the east–west communication route that connected the coast to the highlands along the Carabamba River. Our survey yielded coastal and highland ceramics on numerous sites (highland textiles and ceramics were also found in the lower Virú Valley [Downey Reference Downey2015; Millaire Reference Millaire, Quilter and Castillo Butters2010; Szpak et al. Reference Szpak, Millaire, White, Lau, Surette and Longstaffe2015:457–458]), many of which were also littered with camelid bones. The presence of camelid remains is suggestive of the importance of herding and caravaning in the area, which played a key role in moving goods and ideas across valleys and between the highlands and the coast throughout prehispanic times (Wilson Reference Wilson1988). The camelid featured in Geoglyph 4 may thus have been intended as a celebration of the importance of this animal at a time when long-distance travel was booming in the region.

The geoglyphs presented in this article could therefore have marked the location of an important place for travelers. Geoglyphs 2 to 5 are in a secluded quebrada that would have channeled people toward the largest geoglyph (Geoglyph 3), which is located below one of Cerro Misia's peaks that features yellow-colored rocks and stands out in the surrounding landscape. This would have been an ideal location for travelers to perform rituals before continuing their journey (for a description of such rituals, see Bikoulis et al. Reference Bikoulis, Gonzalez-Macqueen, Spence-Morrow, Bautista, Alvarez and Jennings2018:1387–1388).

Other clues suggest possible connections with fertility. The geoglyphs are located where the Carabamba River meets the Las Salinas River, a place where a natural spring called Puquio Grande also originates. Interestingly, the geoglyphs face the highlands, the source of all waters, and many iconographic elements refer to water and fertility. For example, Geoglyph 1 features a jaguar and a snake, which are often related to fertility in Andean iconography (Bischof Reference Bischof1994:217; Burger Reference Burger1992:153; Guffroy Reference Guffroy1999:112; Hocquenghem Reference Hocquenghem1983:61–63; Venturoli Reference Venturoli2005:73). Geoglyph 2 features a tadpole, an amphibious creature related to earth, water, and fertility (Venturoli Reference Venturoli2005:74). Geoglyph 5 features a spiral motif, which Masini and colleagues (Reference Masini, Orefici, Rojas, Lasaponara, Masini and Orefici2016:277) argue can be linked to water. The spiral may also represent a land snail (Scutalus sp.), which reproduces during the rainy season and was consumed by locals throughout prehispanic times (Gálvez Mora et al. Reference Gálvez Mora, Castañeda Murga, Becerra Urteaga and Olivas1996). The possible bird in Geoglyph 3 may represent the sky, yet another source of water (Burger Reference Burger1992:107). If those geoglyphs were indeed related to fertility, one could argue that they were made by people who lived in this arid stretch of land to perform propitiatory fertility-related rituals.

More work is needed in this part of the valley to identify the extent of this ritual site and to understand the relationship among the geoglyphs, the landscape, and the human groups that inhabited the lower Carabamba Valley. However, it is important to note that this stretch of land is presently under threat not only from erosion caused by natural phenomena but also, and more importantly, from illegal modern mining, quarrying, and looting activities that will inevitably thwart future archaeological research on prehispanic geoglyphs in the Northern Andes.

Acknowledgments

The Proyecto de Prospección Arqueológica en el Valle del Río Carabamba was conducted by the authors with the help of Kayla Golay Lausanne. The survey was conducted with a permit from the Ministerio de Cultura del Perú (Resolución Directoral N° 163-2019/DGPA/lVMPCIC/MC). This research was supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council Canada (435-2016-739).

Data Availability Statement

Georeferenced orthophotos of geoglyphs are stored at Western University, London, Ontario, Canada.