Introduction

In August 2019, Narvie J. Harris Elementary School in Decatur, Georgia posted a display of appropriate and inappropriate hairstyles for all students to see (Vigdor Reference Vigdor2019). Each picture was that of a Black child. The only hairstyles labeled as appropriate for boys were variations of short (also known as low cut) styles. There were no pictures of styles “appropriate” for girls. However, “inappropriate” hairstyles were those most commonly associated with Black identities such as high-tops, box-braids, and twists. When challenged, the school district contended that the display of appropriate and inappropriate hair was a miscommunication of the school dress school policy (Vigdor Reference Vigdor2019). However, these kinds of “miscommunication” reflect racialized biases and stigma associated with Black hairstyles and the way that schools actively engage in practices that suppress Blackness while normalizing Whiteness.

The literature on race and discipline in schooling primarily focuses on the school-to-prison pipeline (Heitzeg Reference Heitzeg2009; Hirschfield Reference Hirschfield2008; Rios Reference Rios2011; Wolf and Kupchik, Reference Wolf and Kupchik2017) and the harms of suspensions and expulsions that are disproportionately meted out to students of color (Annamma et al., Reference Annamma, Morrison and Jackson2014; Fine Reference Fine1991; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Simonsen, Betsy McCoach, Sugai, Lombardi and Horner2015; Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Skiba and Noguera2010; Heitzeg Reference Heitzeg2009; Hines-Datiri and Andrews, Reference Hines-Datiri and Carter Andrews2017; Meiners Reference Meiners2011; Monroe Reference Monroe2005; Noguera Reference Noguera and Mica2008; Noltemeyer et al., Reference Noltemeyer, Ward and Mcloughlin2015; Smith and Harper, Reference Smith and Harper2015; Welch and Payne, Reference Welch and Payne2011). While providing important insight, scholars in this literature spend less time engaging in conversation and theoretical inquiry about how seemingly minor policies, like dress codes, and minor forms of punishment, like loss of privileges, are created and the consequences they have for children.

In this paper, I conceptualize schools as sites that seek to reproduce Whiteness and further racialize Blackness as a subordinate racial category in the social development of Black children. The possibility of being disciplined is a constant threat in the lives of Black students (Annamma et al., Reference Annamma, Morrison and Jackson2014; Fine Reference Fine1991; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Simonsen, Betsy McCoach, Sugai, Lombardi and Horner2015; Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Skiba and Noguera2010; Heitzeg Reference Heitzeg2009; Hines-Datiri and Andrews, Reference Hines-Datiri and Carter Andrews2017; Meiners Reference Meiners2011; Monroe Reference Monroe2005; Noguera Reference Noguera and Mica2008; Noltemeyer et al., Reference Noltemeyer, Ward and Mcloughlin2015; Smith and Harper, Reference Smith and Harper2015; Welch and Payne, Reference Welch and Payne2011). Scholars who analyze dress code and school discipline primarily focus on the racial trauma Black students experience due to such policies (Mbilishaka and Apugo, Reference Mbilishaka and Apugo2020) and how schools reproduce various inequalities for minority students (Morris Reference Morris2005). However, the primary focus of this paper seeks to understand how Whiteness is maintained and reproduced and how Blackness becomes further conceptually racialized in the school setting. Such a position centers on how White supremacy is an overarching political system (Mills Reference Mills2014) that is maintained through dress codes via hegemonic practices (Gaventa Reference Gaventa1982; Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971) and how racialized norms become imposed upon low-income minority children, particularly Black children (Byrd and Tharps, Reference Byrd and Tharps2014a; Harris Reference Harris2014; May and Chaplin, Reference May and Chaplin2008; Mele Reference Mele2017; Morris Reference Morris2005; Murphy Reference Murphy1990; Patton Reference Patton2006; Peterson and Kern, Reference Peterson and Kern1996; Wallace Reference Wallace1978).

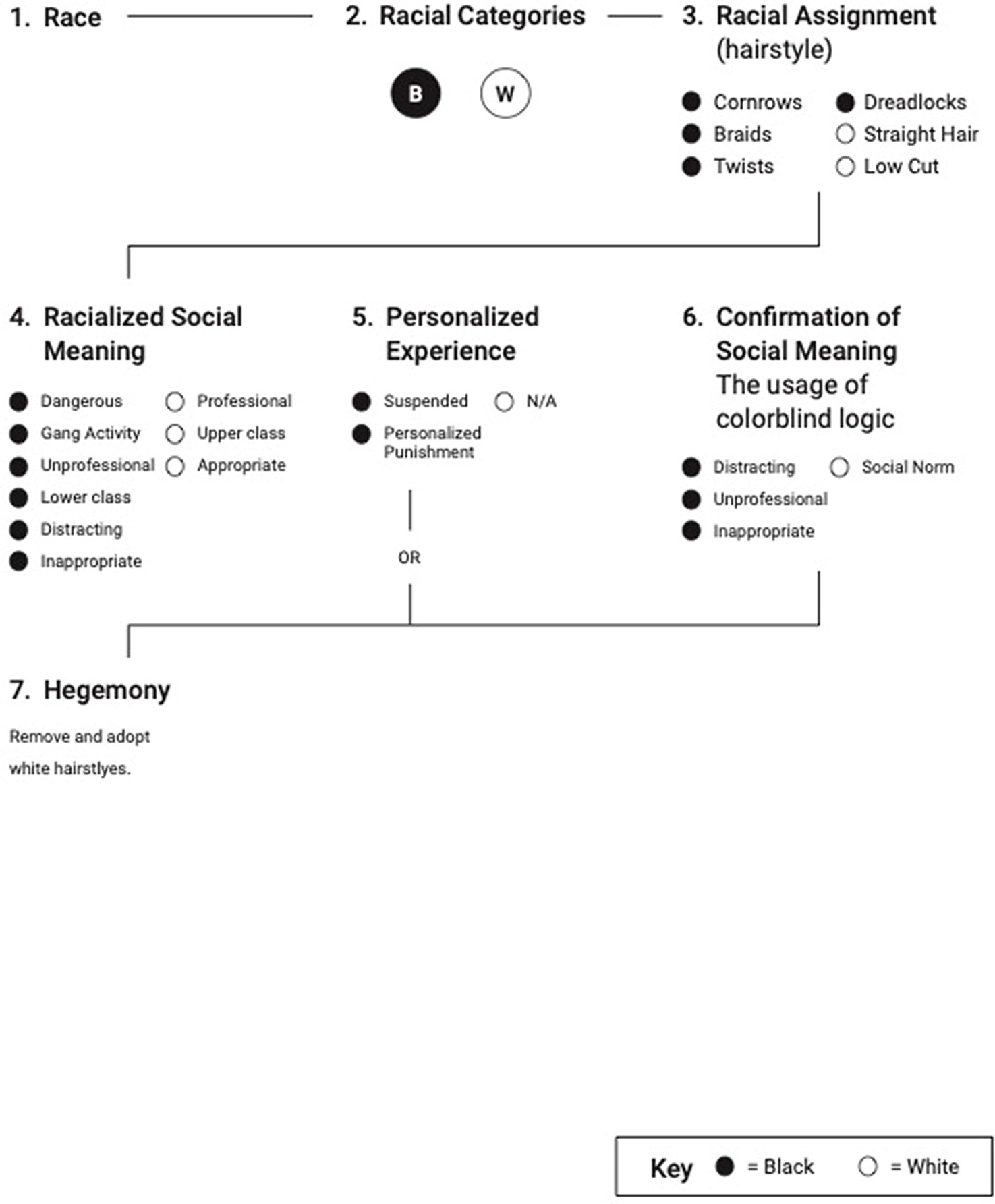

Therefore, I adopt Antonio Gramsci’s (Reference Gramsci1971) and John Gaventa’s (Reference Gaventa1982) theoretical framework of hegemony. Hegemony is broadly understood through the various ways in which those in power engage in distinct forms of domination and coercion to force subordinate groups to adopt particular practices. Hegemonic forces explain how teachers and administrators utilize hairstyle dress code policies across the United States to enforce a particular physical aesthetic that corresponds to Whiteness. Next, I offer an adaptation of David Simson’s (Reference Simson2013) critical race model of racial disparities to conceptually show what Black students might encounter if teachers or administrators deem their hairstyle to be a distraction, inappropriate, or unprofessional. Using polymorphous engagement (Gusterson Reference Gusterson1997), multiple real-life cases captured in various news articles across the United States are highlighted in the step-by-step model. In all, I show how White supremacy is maintained through hegemony (Gaventa Reference Gaventa1982; Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971) when it comes to hair. My hope is that the conceptual model will aid future scholars in understanding and researching the role that seemingly minor school policies like dress code play in reinforcing Whiteness and how teachers and administrators both use hegemony (Gaventa Reference Gaventa1982; Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971) to reinforce the idea that Blackness is incommensurate by deeming particular physical aesthetics that correspond with Blackness as unacceptable.

Black Hairstyles in the Context of Whiteness

Black people view their hairstyles as an expression of their Blackness and cultural identity (Banks Reference Banks2000). From the fade to the box braids, Black peoples’ careful and sometimes elaborate hairstyles symbolize self-worth and love for one’s racial and ethnic identity (Mercer Reference Mercer1987; Thompson Reference Thompson2008, Reference Thompson2009). Against White standards of beauty that validate straight hair, Black folks use the curl, nap, and twist on their head to tell a story of who they are in this world and the genealogical lineage of their ancestors. Essentially, “[H]air is a physical manifestation of our being that becomes loaded with social and cultural meaning” (Banks Reference Banks2000, p. 26). Hence, Black folks’ hairstyles are a part of the intricate fabric through which they understand themselves; hair is one of many ways they showcase what makes them beautiful, even under the gaze of Whiteness.

Hairstyles code the body in a unique way that highlights how people feel about themselves outside the bounds of social norms (Banks Reference Banks2000; Gwalthney Reference Gwaltney1980; Mercer Reference Mercer1987; Thompson Reference Thompson2008, Reference Thompson2009). However, in a society that seeks to maintain Whiteness, Black hairstyles not only have cultural meaning but are also political (Byrd and Tharps, Reference Byrd and Tharps2014a; Patton Reference Patton2006; Robinson Reference Robinson2011). Hence, Black people utilize their hair as a form of symbolic resistance to the power structures that validate White beauty and aesthetic standards. Unwilling to conform to societal standards of hair and beauty, Black people use their hair and hair accessories, such as durags and hair wraps, as an engagement with self-expression rooted in their Black identity (Banks Reference Banks2000).

However, Whiteness is the normalized aesthetic within U.S. society; thus, beauty and professionalism are defined and validated through hairstyles and hair textures that are closely associated with White people (Patton Reference Patton2006; Robinson Reference Robinson2011). It is the straight and curly hair embodied by Whites that is labeled beautiful in magazines, television, and movies. So, although Black hairstyles are a form of resistance and expression, Black people frequently find themselves chemically straightening or cutting their hair in order to be accepted by White people (Patton Reference Patton2006). Additionally, the constant subjection to a normalized standard of beauty and professionalism found within Whiteness unconsciously or consciously induces some Black people to transform their hair in order to feel beautiful.

The practice of straightening one’s hair is a class performative act. Nappy and kinky hair textures are historically linked to Black slavery (Patton Reference Patton2006) because the social organization of those enslaved was determined by physical features. Light-skinned Black people with wavy or straight hair were usually granted higher status and more privileges as “house slaves.” At the same time, darker skin enslaved people with nappy and kinky hair textures were subject to harsher treatment and conditions because they were seen as ugly and expendable (Patton Reference Patton2006). This phenotypical sorting meant that White beauty standards were engraved in the enslaved collective consciousness and ultimately passed through generations. From these roots, Black people have adopted White beauty standards and accept these standards as a way to gain access to better spaces and treatment. Furthermore, this relationship between enslaved people and citizens meant that straight hair was a symbol of higher-class (owner) status (Patton Reference Patton2006; Wallace Reference Wallace1978). Therefore, transforming one’s hair was and is a class performance, and because White class performance is normalized practice, Black people find themselves transforming their hair for the sake of trying to compete for earnings (Patton Reference Patton2006; Wallace Reference Wallace1978) within racialized organizations (Ray Reference Ray2019).

The Enforcement of Whiteness through Hairstyles

Frequently, dress code policies at school and work reflect a White understanding of professionalism that unconsciously pushes Black presentation of self to the periphery of civil society (May and Chaplin, Reference May and Chaplin2008). For example, in March 2014, the U.S. Army updated its policy around appearance and grooming (AR 670-1). The policy stated that hairstyles like cornrows, braids, twists, and dreadlocks were not allowed (or allowed within narrow limits) because they were a distraction (Byrd and Tharps, Reference Byrd and Tharps2014b). In 2017 the policy was revoked, but during the three years in which it was enacted, many people, including prominent African American politicians, found it necessary to educate military officials about the differences between Black and White hair textures (Mele Reference Mele2017). Generally, Black hair grows out and up, not down like White people’s hair; therefore, hairstyles such as cornrows, braids, twists, and dreadlocks are used to tame Black hair, just as buns (permitted for women under AR 670-1) tame White hair (Mele Reference Mele2017).

School dress codes, similarly, frequently reflect a lack of understanding of Black styles. Black dress—or what is often referred to as “urban wear”—is connected in many White minds to gang activity (Murphy Reference Murphy1990) or the lower class (May and Chaplin, Reference May and Chaplin2008; Peterson and Kern, Reference Peterson and Kern1996). This presumed interrelationship intrinsically leads to school policies that label Black hairstyles as a distraction or a gateway to gang activity (Byrd and Tharps, Reference Byrd and Tharps2014a; Mele Reference Mele2017). For example, in 2016, Butler Traditional High School in Kentucky introduced a new policy banning twists, dreadlocks, afros, and cornrows because they were “distracting” (Wilson Reference Wilson2016). In February 2019, students at John Muir High School in Pasadena, California walked out in protest of a new school policy that banned wearing durags. The rationale for the ban was that administrators associated durags with gangs and did not understand that students were wearing durags to help preserve a hairstyle known most commonly as waves (Johnson Reference Johnson2019). These racializing beliefs by some White teachers and administrators that connect urban wear and hairstyles to gang activity, or label Black styles as distracting, stem from media portrayals of Black bodies and the inability to disconnect Blackness from deviant behavior and culturally prescribed class performances (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2014; Emmer Reference Emmer1994; Kearney et al., Reference Kearney, Plax, Sorensen and Smith1988; Townsend Reference Townsend2000).

Moreover, the association between Black hairstyles and gang activity is also rooted in class as Black styles are seen by some White teachers and administrators to jeopardize Black children’s ability to be successful and experience upward mobility in their lifetime (Harris Reference Harris2014). This position stems from the belief that White presentation of dress is more closely related to wealth, and Black presentations are not (May and Chaplin, Reference May and Chaplin2008; Peterson and Kern, Reference Peterson and Kern1996). Therefore, to ensure Black children subscribe to more “professional” physical appearances, schools enact dress code policies to help normalize particular presentations, assuming that such socialization is preparing students for later success (Murphy Reference Murphy1990; Woods and Ogletree, Reference Woods and Ogletree1992; Workman and Studak, Reference Workman and Studak2008). Thus, under a White racial frame of promoting professionalism, reducing differences, and discouraging deviant behavior (Feagin Reference Feagin2010), dress code policies are the perfect example of colorblind racism (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2002; Reference Bonilla-Silva2014): the policies are racist without making specific reference to race.

An insidious outcome of requiring that Black students adopt Whiteness as a presentation is to further enlarge the school-to-prison pipeline, as school dress code policies that favor Whiteness are being implemented in the context of zero-tolerance disciplinary policies. The power and protection granted by zero-tolerance disciplinary policies allow Black students to face punishment at the hands of teachers and administrators who no longer bear the “burden” of making discretionary decisions. Today, schools are already disproportionately punishing Black students more than White students for the same infractions even in supposed “zero-tolerance” environments that are supposed to ensure equality (Annamma et al., Reference Annamma, Morrison and Jackson2014; Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Skiba and Noguera2010; Heitzeg Reference Heitzeg2009; Hines-Datiri and Andrews, Reference Hines-Datiri and Carter Andrews2017; Meiners Reference Meiners2011; Monroe Reference Monroe2005; Noguera Reference Noguera and Mica2008; Skiba et al., Reference Skiba, Michael, Nardo and Peterson2002; Welch and Payne, Reference Welch and Payne2011; Witt Reference Witt2007). Adding a dress code that “criminalizes” Blackness ensures that the racial punishment gap grows even wider; now Black students are being punished simply for wearing common and traditional Black hairstyles. Students who get labeled as habitual offenders at an early age can expect an early childhood of detention and suspension, which frequently leads to expulsion and ultimately, frequent contact with the criminal justice system as they reach adolescence (Rios Reference Rios2011). Dress codes that forbid Black hairstyles add Blackness to a list of habitual offenses (Mbilishaka and Apugo, Reference Mbilishaka and Apugo2020) within the school setting, further enlarging the space in which racialization and punishment (Brewer and Heitzeg, Reference Brewer and Heitzeg2008; Morris Reference Morris2005) is implemented upon Black bodies (Rios Reference Rios2011).

White Hegemony as Dress Codes

Hegemony exists in a duality. The first part is domination, where a ruling class exercises control of subordinate groups through the production of intellect, moral beliefs, and leadership (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971). The ruling class sets the standards that all other groups must follow as it pertains to their livelihood within the state. This is done by ensuring all people adopt a particular cognitive disposition that reinforces the concept that the ruling class is superior in all social and political discourses (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971). Such action ensures that subordinate groups remain within their assigned social, political, and economic strata with little room for mobility.

The second part of hegemony is coercion, where the ruling class seeks to induce subordinate groups to actively engage within parameters set by the state either by enticing them or by using force. For hegemony to operate effectively, a unique kind of ideological rhetoric must be internalized by all subordinate groups (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971). This rhetoric becomes ideology—specifically, the idea that the ruling class operates in the subordinates’ best interest—and its adoption allows for the maintenance of positive social relationships between the ruling class and subordinate groups. Through political and social tactics, the ruling class promises and passionately emphasizes that they will utilize their power to better subordinate groups. By building a relationship of coerced trust, those in power have subordinates relinquish some of their autonomy under the perception that the powerful know best and will ensure subordinate well-being as long as those being subordinated follow particular guidelines.

In the school setting, administrators, and teachers—as agents of the ruling class—create rules and regulations that are designed to indoctrinate students into particular ideologies that reproduce societal norms (Giroux Reference Giroux1983). Such a position means that administrators and teachers are representatives of a state-sanctioned agency tasked with exerting forms of hegemony upon students for the sake of ensuring future generations adopt normalized practices (Giroux Reference Giroux1983). In the context of my argument, the hegemonic ideology that must be inculcated into students is the concept that Whiteness is the only socially acceptable, culturally prescribed performance allowed within civil society (Yosso Reference Yosso2005). Essentially, through prescribed hegemonic tactics, the school setting becomes a space that seeks to reproduce a racial scheme where Whiteness is valued above all else (Gillborn Reference Gillborn2005, Reference Gillborn2006; Long Reference Long2018; Yosso Reference Yosso2005).

However, for Whiteness to be reproduced on Black students, teachers and administrators must first invoke a specific kind of racialization of Blackness that renders Black performances and physical expressions of one’s Blackness as “other.” Racialization refers to the social practice of creating a “racial other” in which a particular group is defined and understood to be different based on essentialist and cultural understandings of race (Mills Reference Mills1998; Murji and Solomos, Reference Murji and Solomos2005; Omi and Winant, Reference Omi and Winant2014). The making of the “racial other” is historical and structural. Negative social and cultural references often influence the mistreatment and discrimination Black people are forced to endure within public spaces, institutions, and organizations, as falling into the “racial other” category moves Black people to the subordinate group inferior to White people in all aspects (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva1997; Mills Reference Mills1998; Murji and Solomos, Reference Murji and Solomos2005; Omi and Winant, Reference Omi and Winant2014; Ray Reference Ray2019). Once defined as the “racial other,” the dominant class or its agents are granted the ability, through rules and regulations, to engage in various forms of hegemony that are embedded within racism. In the U.S. racial project, Black and White hairstyles are easily differentiated (Mercer Reference Mercer1987; Thompson Reference Thompson2008, Reference Thompson2009), and this allows for hegemony to be implemented through policies aimed at erasing Black hairstyles in public spaces—policies like school dress codes.

By racializing Black hairstyles via association with gang activity, by deeming them unprofessional, by labeling Black hair dangerous, lower-class, distracting, and inappropriate (Byrd and Tharps, Reference Byrd and Tharps2014a; Harris Reference Harris2014; May and Chaplin, Reference May and Chaplin2008; Mele Reference Mele2017; Murphy Reference Murphy1990; Patton Reference Patton2006; Peterson and Kern, Reference Peterson and Kern1996; Wallace Reference Wallace1978), Black students become exposed to various forms of hegemony (Gaventa Reference Gaventa1982; Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971) within the school setting. Teachers and administrators first identify particular expressions of Blackness as a racial other and then engage in hegemonic practices that erase Black expression in a manner embodying colorblindness. With hegemonic colorblindness, Black hairstyles are banned for being a distraction and not representative of success—not because they are Black (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2002; Reference Bonilla-Silva2014; Brewer and Heitzeg, Reference Brewer and Heitzeg2008). These dress-codes around hairstyles are racist because they target Black students and produce anti-Blackness.

Building upon the concept of the school being a site in which hegemonic control is enacted upon students, Simson (Reference Simson2013) conceptualizes how such a process is applied in the context of severe punishment for Black students. Simson (Reference Simson2013) contextualizes the process in which teachers disproportionately punish Black students, not because of behavioral infractions but because they are Black, and teachers harbor racialized biases and stigma towards Black people. For example, instead of merely breaking up a scuffle between Black second graders, school “resource” officers handcuff these children and remove them from the school building (Rios Reference Rios2011). However, the power in hegemony is not always achieved through extreme tactics or punishments (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971) like suspension or expulsion as Simson (Reference Simson2013) describes. On the contrary, it is often and more effectively enacted through rules and regulations that seem to inflict the least amount of pain on the subjugated population (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971), for example, through school dress codes. The possible punishment for violating dress codes is usually less severe than suspension or expulsion; however, more subtle policies create a setting in which Black students are more covertly and seamlessly indoctrinated and/or subordinated into Whiteness. In order to avoid minor forms of punishment, Black students willingly adopt White aesthetics for the sake of avoiding unnecessary confrontations with teachers and administrators. However, in doing so, they also learn to accept the message that White hairstyles are more acceptable and professional.

Teachers and administrators actively convince students that dress codes are for students’ own good (Morris Reference Morris2005; Murphy Reference Murphy1990; Woods and Ogletree, Reference Woods and Ogletree1992; Workman and Studak, Reference Workman and Studak2008). By having an active conversation about professionalism and societal expectations necessary for upward economic mobility, teachers and administrators begin the process of coercing students to adopt the belief that assuming a White aesthetic is in students’ best interest. Specifically, teachers and administrators focus on how, within corporate America, certain kinds of dress are expected, and anything that deviates from a specific aesthetic will hinder the applicant’s chances of successfully working in a corporate environment. Such a controlled dialog between teachers or administrators and students illustrates how hegemony is achieved through conversations (Gaventa Reference Gaventa1982; Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971), as now the students believe subscribing to Whiteness will yield the most benefit for them in their futures. Hence, Black students cut or straighten their hair for the sake of adhering to societal norms that are purportedly linked to upward economic mobility rather than questioning why these standards exist or addressing the other barriers that have barred Blacks’ upward mobility, no matter their appearance. Failure to comply often results in various forms of retaliation from teachers and administrators, as students could lose school privileges or be suspended. Such actions speak volumes to the power of hegemony—when coercion fails through the means of conversation (Gaventa Reference Gaventa1982), acts of domination are imposed upon subjugated bodies (in this case, Black students) to force specific kinds of social norms (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971).

A Model for Understanding How Dress Codes Reinforce Whiteness

Simson’s (Reference Simson2013) socially constructed racial school discipline model is a Critical Race Theory-based model that explains racial disparities in the American school system. The model focuses on the implications racialized biases and stigma have in school discipline. He contextualizes the process in which teachers disproportionally punish Black students, not because they are uncomfortable with culturally prescribed class performances most commonly associated with Blackness in the school setting (Emmer Reference Emmer1994; Kearney et al., Reference Kearney, Plax, Sorensen and Smith1988; Townsend Reference Townsend2000), but because they are Black (Simson Reference Simson2013).

I build upon Simson’s (Reference Simson2013) model to look explicitly at dress code around hairstyles within the confines of disciplinary actions. My model demonstrates how teachers and administrators create the space necessary to reinforce hegemonic ideology (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971) that coerces Black students to adopt hairstyles more commonly associated with Whiteness. Hegemony is enacted through conversations (Gaventa Reference Gaventa1982), as teachers and administrators try to convince Black students that altering their hairstyles is what is best for them. This argument is based on the notion that race acts as a powerful coercive and ideological tool to further Whiteness within all forms of life (Haney López Reference Haney López1994; Harris Reference Harris1993). My model shows how teachers and administrators engage in practices to normalize Whiteness and ensure other subjugated bodies adopt Whiteness as an ideological reference and as a physical aesthetic.

The model is conceptualized through a Black-and-White binary frame because White supremacy is understood through a racialized hierarchy in which Whiteness is situated at the top and Blackness at the bottom (Ansley Reference Ansley, Delgado and Stefancic1997; Bonnet Reference Bonnett, Werbner and Modood1997; Mills Reference Mills1998, Reference Mills2014). Such a position allows for race to be understood through a binary system as different groups become categorized as either White or Black (Alba and Alba, Reference Alba and Alba2012; Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2014; Hochschild et al., Reference Hochschild, Weaver and Burch2012). Teachers and administrators who racialize students often only look at a few key markers—like hairstyle and hair texture—to determine students’ race. This happens because Blackness is frequently understood through phenotype (Mills Reference Mills1998) whereas other racialized groups may be marked by other factors such as language use (e.g., Spanish for the Latinx) or clothing choices (e.g., headscarves for people of Middle Eastern descent).

The conceptual model was conceived through an abridged version of polymorphous engagement (Gusterson Reference Gusterson1997). I utilize an arrangement of stories captured by various news articles where teachers or administrators singled out Black students because of their hairstyles. As a methodological practice, polymorphous engagement includes multiple techniques ranging from “interacting with informants across a number of dispersed sites… and collecting data electronically from a disparate array of sources in many different ways… . [such as the] extensive reading of newspapers” (Gusterson Reference Gusterson1997, p. 116). Researchers only access information that has been publicly disseminated through different mediums. Polymorphous engagement aims to restore balance by employing a less intrusive methodological technique and help ensure the sanctity of the subject as long as the moral and ethical practices of conducting research are still maintained when applying this particular framework (Gusterson Reference Gusterson1997).

Furthermore, utilizing polymorphous engagement allows me to conceptually map out the various ways in which hegemony is enacted upon Black students to normalize hairstyles that correspond to Whiteness. These cases of Black students being punished or at risk of being punished within the school system broaden our collective understanding of how the application of Whiteness operates upon Black bodies through more subtle practices. Simson’s (Reference Simson2013) model acts as a catalyst in which school discipline cannot only be measured by the rates in which Black students are disproportionately punished but also how the possibility of being punished is a lingering threat. Using polymorphous engagement, the hegemonic practices illustrated in the cases allow us to conceptually imagine the various ways in which teachers and administrators use dress code around hairstyles to either force or encourage the adoption of hairstyles that correspond with Whiteness. Hence, the more significant takeaway from the conceptual model is not centered on the similarities or differences between the schools, teachers, or administrators but how White supremacy and White dominance are theoretically embedded within the social world (Ansley Reference Ansley, Delgado and Stefancic1997; Bonnet Reference Bonnett, Werbner and Modood1997; Mills Reference Mills1998, Reference Mills2014). Such a position ensures all expressions of Blackness, like hairstyles, can be punished, and teachers and administrators engage in the covert practice of enacting hegemony upon Black students to further Whiteness.

Model 1 provides a conceptual model for understanding how dress codes reinforce Whiteness. In Step 1 (Race), teachers and administrators must identify a student’s race based upon an essentialist understanding of racial categories. In particular, one’s racial identity is identified through phenotype, ancestry, self-awareness of ancestry, public awareness of ancestry, cultural expression, experience, and subjective identification (Mills Reference Mills1998). Schools are located in neighborhoods, and neighborhoods are racialized (i.e., “Black” neighborhoods), as are schools based on the dominant demographic characteristics of the attendees. Nevertheless, even Black children who go to “White” schools are asked to indicate their race when filling out enrollment forms. All of these factors shape the ways in which students are racialized (Fong and Faude, Reference Fong and Faude2018). Quintessentially, teachers and administrators racialize everyone based on a variety of cues. Such aspects mean that people can identify a student’s race based upon this essentialist understanding of race categories (Mills Reference Mills1998). For simplicity, the explanation of the other steps assumes a Black-White Binary as I focus on the relationship Black students have with Whiteness in the school setting.

Model 1

In Step 2 (Racial Categories) and Step 3 (Racial Assignment), once students have been classified as either White or Black, teachers and administrators sort the students into racial categories that correspond to different racial stereotypes they associate with a person’s racial identity. In the third step, teachers and administrators consciously or unconsciously assign hairstyles to race. These categorizations are historical and structural (Patton Reference Patton2006; Peterson and Kern, Reference Peterson and Kern1996; Robinson Reference Robinson2011; Wallace Reference Wallace1978).

In Step 4 (Racialized Social Meaning), once each hairstyle is sorted into a racial and class group, teachers and administrators tease out broadly the social meaning behind each hairstyle. These meanings emphasize racialized biases and stigma as hairstyles associated with Blackness are seen to symbolize danger, gang activity, lack of professionalism (as viewed through a class lens), distraction, and as inappropriate (Harris Reference Harris2014). On the other hand, hairstyles associated with Whiteness are seen to symbolize professionalism (Patton Reference Patton2006; Wallace Reference Wallace1978).

In Step 5 (Racialized Experience), once teachers and administrators attach social meaning to hairstyles, they will develop disciplinary protocols to suppress the exhibition of these hairstyles. News articles over the last several years capture this social phenomenon being played out in schools across America. For example, in 2013, Vanessa Vandyke was being bullied by other students because of her puffy hairstyle. Instead of protecting Vanessa, administrators told her mother to cut or straighten Vanessa’s hair, or she would be expelled because her hairstyle was “a distraction” (Battle Reference Battle2017, Huffpost 2013). Vanessa ended up leaving the school not long after. In 2017, teachers and administrators at Mystic Valley Regional Charter School in Malden, Massachusetts, labeled the braided hair of sixteen-year-old students Mya and Deanna as distractions to the learning environment, thus violating the school dress code. School administrators told Mya and Deanna’s parents that they needed to “fix” their daughters’ hair, and as punishment for violating the dress code, Mya and Deanna were banned from participating in extracurricular activities. Additionally, school administrators threatened Mya and Deanna with school suspension if they did not remove their braids (Lattimore Reference Lattimore2017). In August 2019, J.T., a thirteen-year-old at a Texas junior high school, faced in-school suspension for having a cursive “M” shaved on the side of his head. Although the symbol was neither gang-related nor derogatory, the Assistant Principal told J.T. to report to the Discipline Office for being “out of the dress code” (Fieldstadt Reference Fieldstadt2019). Two months later, on October 9, 2019, Marian Scott, an eight-year-old girl at Paragon Charter Academy in Michigan was told that she could not be included in the school pictures because of her red hair extensions. School officials said the hair color violated the handbook stating children’s hair color “must be natural tones” (Buchmann Reference Buchmann2019). Lastly, in January 2020, DeAndre Arnold was suspended from Barbers Hill ISD school in Mont Belvieu, Texas and would not be allowed to walk for graduation unless he cut his dreadlocks. School officials took action because of the length of DeAndre’s hair, as it was too long according to the school policy (Associated Press 2020).

In Step 6 (Confirmation of Social Meaning: The Usage of Colorblind Logic), in attaching racialize social meaning to the hairstyles the teachers or administrators must justify their reasoning. This has two parts. First (Step 6.1), the teacher or administrator must refer to the student handbook and express to the student and their parents that this particular hairstyle actively breaks the dress code. Next (Step 6.2), the teacher or administrator must engage in colorblind language (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2002; Reference Bonilla-Silva2014) in articulating why these particular hairstyles are being penalized. Hence, the language of “distraction,” “inappropriate,” or “lacking professionalism” are employed. This type of race-neutral language is seen in the cases of Mya and Deanna, J.T., Marian Scott, Vanessa Vandyke, and DeAndre Arnold (Associated Press 2020; Battle Reference Battle2017; Buchmann Reference Buchmann2019; Fieldstadt Reference Fieldstadt2019; Huffpost 2013; Lattimore Reference Lattimore2017). The racial neutrality of the teachers and administrators’ language coupled with school dress codes that forbid particular hairstyles allows the racialized rhetoric to be covert. However, the fact that hairstyles most commonly associated with Blackness are the ones being penalized within the school setting uncovers how these practices and policies are an extension of structural racism within the school setting (Harris Reference Harris2014) that corresponds to the logic of colorblind language (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2002; Reference Bonilla-Silva2014).

In Step 7 (Hegemony), in subscribing and promoting the ideology that Black hairstyles are distracting, unprofessional, or inappropriate, teachers and administrators engage in domination and coercion as agents of higher-level dominant groups with the goal of making Black students transform their hairstyles in a manner that is more commonly associated with Whiteness. Teachers and administrators do not want to suspend or take away students’ privileges but create the necessary space for them to adopt particular hairstyles they deem to be professional and not distracting or inappropriate. For example, J.T.—the student with an M shaved into the side of his head—was given two options: either color in the “M” with a jet-black marker or face in-school suspension. J.T. elected to color in the side of his head (Fieldstadt Reference Fieldstadt2019). His decision is not surprising; failure to comply leads to disciplinary action like suspensions. Hence, if a student wants to remain in the classroom and not be removed from school activities with their classmates, they must adjust to the regulations created and enforced by the administrators and teachers even when the regulations are essentially oppressive. When these students comply, it reinforces to other students that there are acceptable (White) and unacceptable (Black) hairstyles.

Racialization and Reproduction of Whiteness in School

What can be deduced from how schools regulate hairstyles is how Whiteness extends the bonds of racial identity and functions as a kind of property that is valued and protected within all social practices (Harris Reference Harris1993). Cheryl I. Harris (Reference Harris1993) states, “[W]hen the law recognizes, either implicitly or explicitly, the settled expectations of Whites built on the privileges and benefits produced by White supremacy, it acknowledges and reinforces a property interest in Whiteness that reproduces Black subordination” (Harris Reference Harris1993, p. 1731). Teachers and administrators value and protect a physical presence that validates a White aesthetic. Such a position actively renders non-White aesthetics and presentations of self as a lesser category unworthy of protection or value. The adoption of dress codes allows teachers and administrators the power to coerce students to alter hairstyles by threatening them with suspension or taking away extracurricular activities like in the cases of Mya and Deanna, J.T., Marian Scott, Vanessa Vandyke, and DeAndre Arnold (Associated Press 2020; Battle Reference Battle2017; Buchmann Reference Buchmann2019; Fieldstadt Reference Fieldstadt2019; Huffpost 2013; Lattimore Reference Lattimore2017).

Furthermore, banning hairstyles associated with Blackness is one way that the state controls Black bodies through anti-Black policies (Yancy Reference Yancy2016). The school setting is a key agent of socialization, and thus the forces of White supremacy have a tool for ensuring all students subscribe to hegemonic ideologies (Yancy Reference Yancy2016). More specifically, ensuring Black students subscribe to Whiteness as an aesthetic helps maintain and reproduce White supremacy as the dominant frame in the social organization of life (Gillborn Reference Gillborn2005, Reference Gillborn2006; Long Reference Long2018). This happens because Black hairstyles are political and a site of resistance to Whiteness (Banks Reference Banks2000; Byrd and Tharps, Reference Byrd and Tharps2014a; Gwaltney Reference Gwaltney1980; Mercer Reference Mercer1987; Patton Reference Patton2006; Robinson Reference Robinson2011; Thompson Reference Thompson2008, Reference Thompson2009), and as such the state has a vested interest in the removal of such hairstyles in spaces deemed part of civil society like corporate America and schools. Allowing for hairstyles commonly associated with Blackness to remain in a key institution like schools unravels the process by which the superiority of Whiteness is woven into the consciousness of Black people and thus removes the racial inferiority of Blackness the state seeks to maintain. Under the façade of upholding standards of professionalism and creating non-distracting learning spaces, teachers and administrators can invoke colorblind rhetoric (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2002; Reference Bonilla-Silva2014), which is effective in convincing Black students that following dress codes is in their best interest. Such a process emphasizes how hegemony occurs through conversation and creates the space necessary for the subject to willingly engage in ruling-class sanctioned social norms (Gaventa Reference Gaventa1982; Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971).

Whiteness is a socially constructed category with no biological reality (Ansley Reference Ansley, Delgado and Stefancic1997; Bonnet Reference Bonnett, Werbner and Modood1997; Haney López Reference Haney López1994; Harris Reference Harris1993; Mills Reference Mills2014). Racialization is a social process that discriminates against marginalized groups based on arbitrary characteristics (Mills Reference Mills1998; Omi and Winant, Reference Omi and Winant2014) like hairstyles to sustain racial oppression while simultaneously uplifting a White aesthetic as the social norm. The reproduction aspect of Whiteness into the social development of Black students and the racialization of Blackness as a subordinate racial category must work together to constantly project into Black students’ minds that their hairstyles, and associated aspects of Blackness more broadly, are inferior. Both must be inflicted upon Black students simultaneously, or the process of indoctrinating Black students into Whiteness will be incomplete. Essentially, hegemony becomes a racialized weapon that teachers and administrators invoke through dress codes and the possibility of disciplinary actions to achieve indoctrination into Whiteness. By telling Black students their hairstyles look like they belong in a gang or are unprofessional and inappropriate (Byrd and Tharps, Reference Byrd and Tharps2014a; Harris Reference Harris2014; May and Chaplin, Reference May and Chaplin2008; Mele Reference Mele2017; Morris Reference Morris2005; Murphy Reference Murphy1990; Patton Reference Patton2006; Peterson and Kern, Reference Peterson and Kern1996; Wallace Reference Wallace1978), students are both encouraged to look White and also told that their Blackness is inferior. Hearing this message repeatedly, Black students eventually perform and reproduce Whiteness by altering their physical appearance to avoid punishment but also because they ultimately buy into the hegemonic stance.

Subtle punishments teachers and administrators enact against violators of hair codes are directly linked to how colonized people learn to subscribe and embody Whiteness within all social and private performances of the self (Banks Reference Banks2000; Byrd and Tharps, Reference Byrd and Tharps2014a; Gwalthney Reference Gwaltney1980; Mercer Reference Mercer1987, Patton Reference Patton2006; Robinson Reference Robinson2011; Thompson Reference Thompson2008, Reference Thompson2009). The practice of removing hairstyles most commonly associated with Blackness was prognosticated by W. E. B. Du Bois ([1906-1960] Reference Du Bois and Aptheker2001), who theorized that the desegregation of schools would lead to a racial suicide of Blackness and Black culture. He suggested that all that would remain within the school setting is the ghost of Blackness as Black students learned to mimic Whiteness and White culture while still not gaining the same status as their White counterparts. Hence, the by-product of telling Black students that their hairstyles are not acceptable reinforces the belief that their Blackness is inferior to Whiteness.

Conclusion

In a society dominated by Whiteness where the middle-class aesthetic is the normalized presentation accepted in (White) civil society, teachers and administrators wittingly or unwittingly try to socialize students into performing Whiteness through dress codes. Because there are negative stereotypes associated with Black hairstyles (Harris Reference Harris2014; May and Chaplin, Reference May and Chaplin2008; Patton Reference Patton2006; Wallace Reference Wallace1978), teachers and administrators amplify these negative stereotypes by telling their students that these hairstyles are unprofessional, inappropriate, or distracting from the learning environment (Associated Press 2020; Battle Reference Battle2017; Buchmann Reference Buchmann2019; Fieldstadt Reference Fieldstadt2019; Huffpost 2013; Lattimore Reference Lattimore2017). Such practices further White hegemony (Gaventa Reference Gaventa1982; Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971), which prioritizes Whiteness as the only aesthetic acceptable in the school setting.

Rather than socializing children to adopt White hairstyles, schools should be restructured to actively integrate pedagogies found outside of Whiteness into the social fabric of the school. Specifically, schools must make visible and actively weave into every educational endeavor initiatives that seek to broaden children’s understanding of beauty and professionalism that exists outside of Whiteness. Doing so would disrupt the reproduction of Whiteness and become a project of anti-racism (Kendi Reference Kendi2019; Oluo Reference Oluo2019).

The transformative process of integrating pedagogies found outside of Whiteness also builds upon Bettina L. Love’s (Reference Love2019) work on incorporating an abolitionist schema into education and Henry Giroux’s (Reference Giroux1983) concept of school as a site to build resistance. Love (Reference Love2019) and Giroux (Reference Giroux1983) present the basis for social transformation that exists within the theoretical inquiry that explores how power, resistance, and agency can be vital in the struggle to restructure education and critical thinking. Love (Reference Love2019) and Giroux (Reference Giroux1983) believe that schools can usher in new pedagogical models for education that do not reproduce social harm and subordinate ideologies. Through the integration of pedagogies found outside of Whiteness comes the process of removing the veil from Black students’ minds, and the idea that their Blackness makes them inferior to their White counterparts. Also, integrating pedagogies found outside of Whiteness can shift negative stereotypes of Blackness some teachers and administrators might harbor that makes them uncomfortable and results in disciplinary actions (Banks Reference Banks1993; Emmer Reference Emmer1994; Kearney et al., Reference Kearney, Plax, Sorensen and Smith1988; Monroe Reference Monroe2005; Morris Reference Morris2005; Payne and Welch, Reference Payne and Welch2010; Townsend Reference Townsend2000; Wun Reference Wun2016). The more teachers and administrators learn about White hegemony and concepts outside of Whiteness, the more likely they will be to understand how policies are racialized and cause social harm.

Hegemony, as explained by Gramsci (Reference Gramsci1971) and Gaventa (Reference Gaventa1982), only persists because there are individual actors who uphold ideals perpetuated by the state and use domination and coercion to maintain social order. Such maintenance often reflects Whiteness as the causal mechanism to organize students (Gillborn Reference Gillborn2005, Reference Gillborn2006; Long Reference Long2018; Yancy Reference Yancy2016). Hence, all school policies, including dress codes, are strategically placed at certain moments of social development to ensure students conform to societal norms (Giroux Reference Giroux1983). Societal norms surrounding the physical presentation of self are engrained into students as they must consistently perform a physical presentation of self that corresponds to Whiteness.

Hence, to disrupt White hegemony, we must reorganize how schools operate on a fundamental level and create new avenues where domination and coercion are not necessary for the organization of people. Overall, schools should be a space in which students can express who they are in the world, and for Black students, that means to identify and express their Blackness through a presentation of self that includes their chosen hairstyles. Limitations placed upon Black students’ physical appearance further creates differences, and such a divide creates the space from which hegemony can be enacted. Teachers and administrators should celebrate and validate students’ expressions of Blackness rather than upholding White presentations of self through policies, such as bans on hairstyles, which only perpetuate anti-Black rhetoric and further the coerced reproduction of Whiteness upon Black bodies.

The practice of punishing Black students for having Black hairstyles has now become a common reaction by some teachers and administrators. More specifically, the actual dress code does not matter anymore, nor do ideals of professionalism hold any real merit. Such logic is merely a placeholder which some teachers and administrators call upon to legitimate their exertion of hegemony upon Black bodies. Shifting the focuses away from actual dress codes and focusing on the formation of racialized biases and stigma by some teachers and administrators allows for a conversation to take place that discusses the possibility that Black students are not being punished because their hairstyle is distracting, unprofessional, inappropriate, or breaks the school dress code but simply because such hairstyles are associated with Blackness, and that is unacceptable. Quintessentially, such understanding builds upon Simson (Reference Simson2013)’s work on how Black children are being punished for being Black, and criminalizing Black hairstyles is an avenue in which such punishment of one’s racial identity is accomplished through more covert colorblind practices.

Acknowledgments

This paper would not have been possible without the intellectual companionship of the people in my life. I want to thank Dr. Ashlee B. Anderson, Dr. Della Winters, Alessandra Early, Abigail Tobias-Lauerman, Shaquille Anderson, Cindy Pimentel, Tavis Lovick, Michael Holliday, Huy Ho, Abigail Toribio, Karolyn Moni. Most importantly, thanks to Dr. Stephanie A. Bohon and Dr. Michelle Christian as this paper would not exist without their guidance and Heidi Mendez for all the support.