People are interested in and affected by events that happen around them. Quite often we not only care whether an event took place but also whether it was performed completely. A clear illustration of this comes from sports: if one leads a marathon race right from the start and for the next 42 km but falls of exhaustion just before the finish line, that runner’s effort is wasted and the sportsman is not crowned as the marathon winner. In a less dramatic example, a client is likely to be angry with a painter who did an impeccable job painting the walls everywhere in the living room except for a spot above the fireplace. As these and many other examples suggest, people are quite tuned to event completion, and so is their language. In language, event completion can be encoded using lexical (e.g., using words completely, fully) or grammatical (e.g., via lexical or grammatical aspect) means.

The main objective of our research is to examine Japanese learners of English’s understanding of completion entailments of second language (L2) predicates in situations where the entailment pattern differs from that of the first language (L1). We will focus on accomplishment predicates with count objects such as eat an apple or erase a star. Of special interest to us is the fact that such predicates have the so-called event cancellation (Tsujimura, Reference Tsujimura2003) or neutral perfective reading (Singh, Reference Singh1998) in Japanese but not in English (Fromkin, Reference Fromkin2000; Ikegami, Reference Ikegami, Makkai and Melby1985; Kageyama, Reference Kageyama1996; Tsujimura, Reference Tsujimura2003; Yoshida, Reference Yoshida2005, Reference Yoshida and Rothstein2008). The term “event cancellation” refers to the fact that in Japanese and some other languages, a simple past accomplishment predicate with a concrete countable object may indicate an incomplete event (i.e., an event that did not reach its culmination point). This is illustrated by sentences in (1) and (2), which exemplify the availability of the event cancellation reading in Japanese but not in English; these judgments will be carefully explored in our study using a sample of monolingual Japanese and English speakers.

(1)

(2)

In (1a), the English simple past sentence Lisa erased the star entails completion (i.e., it describes a star-erasing event as a result of which the star has been removed completely). Accordingly, the sentence becomes semantically infelicitous when it is followed by a clause suggesting that the event is incomplete, such as but some of it still remains, as in (1b). By contrast, a Japanese simple past predicate such as hoshi-o keshita “star-Acc erased” in (2a) can refer to both a complete and an incomplete event, as confirmed by the fact that the sentence (2b) is semantically felicitous. The event cancellation phenomenon has also been observed in Chinese (Smith, Reference Smith1991, Reference Smith1994, Soh & Kuo, Reference Soh, Kuo, Verkuyl, de Swart and van Hout2005; Tai, Reference Tai, Testen, Mishra and Drogo1984, Yin & Kaiser, Reference Yin, Kaiser, Granens, Koeth, Lee-Ellis, Lukyanchenko, Prieto Botana and Rhoades2011), Hindi (Arunachalam & Kothari, Reference Arunachalam and Kothari2011; Singh, Reference Singh1998), Malagasy (Travis, Reference Travis, Tenny and Pustejovsky2000), and Thai (Koenig & Muansuwan, Reference Koenig and Muansuwan2000).

For a Japanese learner of English to know that the English sentence in (1a) entails completion is not trivial. In order to arrive at a targetlike understanding of aspectual entailments of simple past accomplishment predicates in English, the L1 Japanese learner needs to invalidate the event cancellation reading. That is, she needs to infer that English simple past predicates only possess the subset of readings, that is, they refer to complete events only.

In the current study, we will show that, in line with full transfer/full access hypothesis (Schwartz & Sprouse, Reference Schwartz and Sprouse1996), Japanese learners of English start out by exhibiting an L1-like pattern in the domain of aspectual entailments in L2 and gradually move toward the L2-like pattern of aspectual entailments. Moving toward the targetlike representation in L2 implies the ability to eliminate the event cancellation reading, which is only available in Japanese. There are (at least) two logically possible ways in which a Japanese learner of English could progress toward a targetlike representation of completion entailments in English: via explicit instruction or via internalization of the English determiner phrases that render the event cancellation reading unavailable. With regard to the first option, explicit instruction does not seem to be a substantive factor because, to the best of our knowledge, it is quite rare that completion entailments are discussed in the classroom. With regard to the second option, however, the properties of determiner phrases (DPs) in English that are discussed in the classroom may indirectly help learners to internalize the compositional rules that are important for the derivation of aspect and completion entailments in English (see the next section). Furthermore, although spontaneous real-life observation available to L2 learners is compatible with their original L1 “superset” setting whereby a simple past accomplishment predicate can refer to either complete or incomplete events, the L2 learners’ sensitivity to the missing data in the L1 input, namely, the fact that L1 English speech sentences like (1a) are (almost) never used to refer to incomplete events, may provide further evidence needed for abandoning the Japanese superset option and maintaining the subset option as the only option available in English past tense sentences. In the following sections we outline how aspect is calculated for past accomplishment predicates in English and Japanese, review previous studies on the event cancellation phenomena, and outline the current study.

Event Cancellation: Linguistic Analysis

Aspect reflects internal properties of an eventuality denoted by the verb in relation to the event’s temporal continuity, such as whether it is complete or incomplete (which is what the current paper focuses on), has an inherent start point or endpoint, as well as whether it is habitual, durative, iterative, and so on. Such aspectual distinctions can be encoded via grammatical or lexical aspect. “Grammatical aspect” is governed by inflectional categories such as tense and aspect that operate above the verb phrase (VP) level.Footnote 1 For example, in English, the simple past form of the predicate build a house (as in John built a house) is considered to entail that the house was built completely, but its past progressive form (as in John was building a house) does not. “Lexical aspect” is calculated compositionally at the VP level as a function of the properties of the verb and its arguments (Dowty, Reference Dowty1979; Tenny, Reference Tenny1994; Verkuyl, Reference Verkuyl1972). For example, the predicate class from the so-called Vendler–Dowty classification (Dowty, Reference Dowty1979; Vendler, Reference Vendler1967) interacts with lexical aspect. In this classification, four types of predicates are distinguished on the basis of the properties of an eventuality denoted by predicate: statives (e.g., know), activities (e.g., run), accomplishments (e.g., run a mile), and achievements (e.g., recognize). In addition, as shown below, the properties of the object DP can influence lexical aspect in general, and whether the predicate refers to a complete and incomplete event in particular.Footnote 2

Research on the event cancellation phenomena across languages reports availability of the reading in languages such as Chinese, Hindi, Japanese, or Thai but not in a language such as English. However, the details of theoretical analyses as to why the reading is available in some languages but not others differ.Footnote 3 One prominent approach to event cancellation examines crosslinguistic differences in the nominal system. Singh (Reference Singh1998) attributes the difference in the availability of these readings in Hindi versus English to the lack of determiners in Hindi. According to Singh, bare noun phrases (NPs) in Hindi create at least two ambiguities that have repercussions for whether a simple past sentence entails event completion. One ambiguity can be found in a mass noun such as “milk” that can be interpreted as “milk” or “the milk.” Whereas Mike drank the milk typically entails event completion, Mike drank milk does not. Another ambiguity occurs when using a count noun such as “apple,” which does not only mean “an apple” or “the apple” but also “apples” or “any part of an apple” and thus interacts with the completion entailment of a sentence (e.g., Ken ate the apple entails event completion whereas Ken ate apples does not). Similar observations on bare NPs in accomplishment predicates and their availability for event cancellation readings are reported for Japanese (Fromkin, Reference Fromkin2000) and for Chinese (Soh & Kuo, Reference Soh, Kuo, Verkuyl, de Swart and van Hout2005). Fromkin (Reference Fromkin2000) claims that Japanese allows bare NPs in sentences and that accomplishment verb predicates with bare NPs are compatible with both complete and incomplete readings. Similarly, in Chinese, Soh and Kuo (Reference Soh, Kuo, Verkuyl, de Swart and van Hout2005) argue that the availability of the event cancellation readings is due to the Chinese nominal system (i.e., lack of articles).Footnote 4

An adaptation of Soh and Kuo’s (Reference Soh, Kuo, Verkuyl, de Swart and van Hout2005) analysis to the case of Japanese provides us with an appropriate framework to offer a detailed account of our learnability assumptions. Therefore, we assume that the differences in availability of the event cancellation readings in Japanese versus English are due to the differences in their DPs. That is, properties of the object DP are taken to modulate the aspectual value of a simple past accomplishment predicate (i.e., its completion entailments). To illustrate this, one could picture a scenario in which Ken was to build three houses but could only finish two of them while leaving the third one built halfway. In English, this event can be described as “Ken built houses” but not as “Ken built the houses” or “Ken built three houses,” thus indicating that the object DP (houses vs. the/three houses) critically interacts with the completion entailments of the sentence. A similar observation holds in Japanese: when the object of the past verb tatemashita “built” is a bare noun as in (3a), Ken-wa ie-o tatemashita (literally “Ken house built”), it is compatible with the incomplete house-building scenario described above. However, when the object is changed to “three houses” as in (3b), the resulting predicate can only refer to a completed event in which all three houses were finished.

(3)

The above demonstrates that the aspectual value of the predicate is conditioned, at least partially, by the object DP. The difference in the completion entailment pattern in English versus Japanese accomplishments is then attributed to the representation of bare nominals in these languages and to whether or how bare nominals combine with functional categories such as Det(erminer) and Num(ber) (Kaku & Kazanina, Reference Kaku, Kazanina and Otsu2007, Kaku, Liceras, & Kazanina, Reference Kaku, Liceras, Kazanina, Slabakova, Rothman, Kempchinsky and Gavruseva2008a, Reference Kaku, Liceras, Kazanina, Chan, Jacob and Kapia2008b). In particular, Soh and Kuo (Reference Soh, Kuo, Verkuyl, de Swart and van Hout2005) adopt Chierchia’s (Reference Chierchia and Rothstein1998b) idea that bare nominals may differ across languages: bare nouns in English may be either count or mass, whereas all nouns in Chinese (and Japanese) are mass.Footnote 5 In addition, they employ Jackendoff’s (Reference Jackendoff1991) classification of nominal features in terms of the binary conceptual feature boundedness ([+/−b]), which indicates whether boundaries of an entity are discernable. Under this classification, singular count nouns in English (star) are bounded, whereas plural count nouns (stars) and mass nouns (milk) are unbounded because entities denoted by them lack precise boundaries. Various functional heads that project within a DP, such as determiners or number morphology, are considered as functions that modulate the value of the boundedness feature of their complement NP. In our analysis (Kaku & Kazanina, Reference Kaku, Kazanina and Otsu2007, Kaku et al., Reference Kaku, Liceras, Kazanina, Slabakova, Rothman, Kempchinsky and Gavruseva2008a, Reference Kaku, Liceras, Kazanina, Chan, Jacob and Kapia2008b) we propose that in English the determiners a and the set the value of the boundedness feature of its complement to [+b], whereas the plural marker −s sets the boundedness value of its complement to [−b].

We assume that Japanese learners of English know, at least at the conceptual level, that English has a mass/count distinction that comes with Det and Num morphology. This assumption is based on two facts. First, explicit instruction in formal classroom settings is available for most Japanese learners of English (at least it was in the case of the L2 learners who participated in this study). Second, as proposed by the rich agreement hypothesis (Koeneman & Zeiljstra, Reference Koeneman and Zeiljstra2014), there is a tight connection between syntax and morphology, which is also realized as a tight connection between a morphosyntactic form and its abstract features, which leads us to propose that the abstract features associated with Det and Num morphology are available to the learners.

Let us illustrate the described approach using an English predicate erased a/the star (Figure 1a) where the bare count noun star enters the derivation as bounded (i.e., [+b]). Figure 1 shows that in English, and other languages with overt determiner and number morphology, NumP and DetP are obligatorily projected (Déprez, Reference Déprez2005; Gabriele, Reference Gabriele, Belikova, Meroni and Imeda2007). In the present example, projection of these categories does not change the boundedness value and the resulting DP a/the star is [+b] at the uppermost level. When the [+b] DP merges with the verb (erased), the entire VP refers to a complete event. The derivation for the predicate erase the stars with a plural object (Figure 1b) is different, but it yields an identical overall outcome in terms of the predicate aspect. The bare nominal star starts as [+b], but the boundedness feature is reset to [−b] once it merges with the plural marker −s when NumP is projected. The value [−b] is then changed back to [+b] as a result of merging with the determiner the. The resulting DP is bounded, and the entire VP entails event completion. When the predicate is used in the simple past tense, heads merging above the VP level (e.g., tense or aspect) do not change the aspectual value, and hence the aspectual value of the sentence coincides with that at the VP level.

Figure 1. Derivation of VPs (a) “erased a/the star” and (b) “erased the stars” in English.

Figure 2 shows the derivation of the Japanese VP hoshi-o keshimashita “gloss: star-Acc erased. The bare noun hoshi is unbounded and enters the derivation as [−b]. NumP and DetP are not obligatorily projected in Japanese, and the boundedness value [−b] remains unchanged. The verb keshimashita merges with an unbounded object, and the resulting predicate can refer either to a complete event or to an incomplete event. This accounts for the availability of the event cancellation reading in Japanese but not in English.

Figure 2. Derivation of the VP hoshi-o keshita (gloss: “star-Acc erased”) in Japanese.

In sum, the account above argues that, in order to correctly derive the aspectual value of the English predicate, learners need to have an understanding of object boundedness, how it is computed, and how it interacts with the projection of NumP or DP in English. Applying this to the case of Japanese learners of English, as learners (with increasing L2 proficiency) gain better awareness of English determiner and number morphology, this will lead them to incorporate the projection of NumP and DP in the L2 grammar, which in turn will contribute to their progress toward a targetlike representation of the predicate aspect.

Previous Studies on L2 Acquisition of Aspect

The acquisition of semantics in the aspectual domain in L2 learners has received considerable attention in the literature (Gabriele, Reference Gabriele2005, Reference Gabriele, Belikova, Meroni and Imeda2007, Reference Gabriele2009, Reference Gabriele2010; Montrul & Slabakova, Reference Montrul, Slabakova, Perez-Leroux and Liceras2002, Reference Montrul and Slabakova2003; Slabakova, Reference Slabakova2000, Reference Slabakova2001, Reference Slabakova2005; Yin & Kaiser, Reference Yin, Kaiser, Granens, Koeth, Lee-Ellis, Lukyanchenko, Prieto Botana and Rhoades2011, Reference Yin and Kaiser2013). Below we briefly discuss several studies that focus on L2 learners’ understanding of aspectual semantics in the target language.

As is true for many phenomena in L2 acquisition, one of the factors that influences whether L2 learners achieve a targetlike representation concerns the relationship between the relevant representations in the L1 and the L2. Speaking of predicate aspect, the L1 and the L2 may use essentially the same encoding of aspect as, for example, English and Spanish do for lexical aspect (i.e., object boundedness influences the aspectual value of the predicate; Nishida, Reference Nishida1994). Alternatively, the L1 and the L2 may use different encoding mechanisms, as in the case of English versus Bulgarian or Russian (in Bulgarian and Russian, object boundedness does not influence aspect but affixes on verbs do). If at the beginning stage of the second language learning process the learners use algorithms from their native language, that is, “L1 transfer” (Gass & Selinker, Reference Gass and Selinker1994; Schwartz & Sprouse, Reference Schwartz and Sprouse1996), a more targetlike performance should be expected in the L2 when the learners use a similar encoding of aspect in their L1. Slabakova’s (Reference Slabakova2000, Reference Slabakova2001) studies on acquisition of English telicity by native speakers of Spanish and Bulgarian and Slabakova’s (Reference Slabakova2005) study of English learners of Russian provide support for this view.

Most relevant to us are two studies by Gabriele (Reference Gabriele2009, Reference Gabriele2010) on aspectual entailments that involve Japanese and English. Gabriele (Reference Gabriele2010) investigated completion entailment of accomplishment predicates with plural objects in Japanese and demonstrated L1 transfer effects of the boundedness of count nouns in the interpretation of telicity by English learners of Japanese. As mentioned, Japanese accomplishment predicates with bare count nouns (i.e., boundedness) are compatible with both complete and incomplete events. The results from interpretation tasks indicate that both intermediate and advanced English learners of Japanese have difficulty in calculating the correct aspectual value of predicates with bare count nouns in Japanese (e.g., kaado-o kakimashita “wrote card”); that is, they interpret them as referring to complete events only. Gabriele argues that this pattern stems from the boundedness of count nouns in L1 English and that overcoming this L1 transfer effect is difficult especially when the learners cannot rely on a morphosyntactic cue to interpret predicate aspect.

In her bidirectional study on English and Japanese L2 learners, Gabriele (Reference Gabriele2009) investigated preemption in the aspectual domain (i.e., cases where certain aspects of the L1 need to be “unlearned” to achieve the L2 pattern). Of critical interest were achievement predicates such as arrive, which yield a progressive reading when they are combined with a progressive morpheme be –ing in English (as in The plane is arriving), but a resultative reading when they combine with the imperfective marker te-iru in Japanese (Hikooki-ga kuuko-ni tsuite-iru “The plane [arrived and] is at the airport”). Gabriele found that preemption was difficult for both groups of learners, but especially for Japanese learners of English, of whom even the most advanced ones incorrectly accepted the resultative reading with achievements in English at a rather high rate. The phenomenon examined in our experiments (completion entailments of simple past accomplishments by Japanese learners of English) represents, arguably, an even more challenging case of preemption. The interpretations available for a simple past accomplishment in L1 Japanese (complete or incomplete events) represent a superset of the interpretations available in the L2. Hence, positive evidence from English whereby accomplishments refer to a complete event (representing L1 English, i.e., subset setting) may be misinterpreted by Japanese learners of English as supporting evidence for their L1 (superset) setting, and thus incorrectly reinforce such superset representation as adequate for the L2. In Gabriele’s study, such reinforcement via positive evidence is unavailable as the progressive and resultative readings are mutually exclusive.

Research Questions and Predictions

Our study investigates two research questions. First, we examine whether adult Japanese learners of English learn to invalidate the event cancellation reading of simple past predicates such as in (1a). Second, if the L2 learners successfully derive completion entailments of L2 predicates, we examine how such understanding develops and interacts with increasing L2 proficiency.

We predict that, with increasing L2 proficiency, Japanese learners of English will progress toward a targetlike representation of aspectual entailment. We further hypothesize that such progress results from two parallel routes: a grammatical route rooted in the learners’ growing awareness of the English determiner and number morphology, which will lead them to incorporate the projection of NumP and DP in the L2 grammar, combined with a statistical route rooted in the learners’ inferences based on missing data. The statistical route is rooted in the assumption that, as proposed for L1 learners, L2 learners may be able to make inferences about the aspectual entailments of English simple past predicates on the basis of missing evidence (see Discussion & Conclusions section).

Finally, an important point that has been noted in the theoretical literature concerns the existence of predicate-level variability and contextual and pragmatic influences with respect to the availability of the event cancellation reading (Hay, Kennedy, & Levin, Reference Hay, Kennedy and Levin1999; Koenig & Muansuwan, Reference Koenig and Muansuwan2000; Soh & Kuo, Reference Soh, Kuo, Verkuyl, de Swart and van Hout2005; Tsujimura, Reference Tsujimura2003). Our experimental study aimed to approach this issue with rigor by including two sizable monolingual groups (L1 English and L2 Japanese) and 16 different predicates that could be screened to yield a (smaller) set of predicates that clearly differ between English and Japanese in terms of the availability of event cancellation reading. The native speaker data, apart from serving as baseline for L2 speakers, are a valuable addition to the existing literature, in which predicate-level variability has received limited empirical examination.Footnote 6

Experiment

Participants

One group of 196 Japanese learners of English (L2 English group) as well as one control group of English monolinguals (L1 English, n = 20) and one control group of Japanese monolinguals (L1 Japanese, n = 20) participated in the experiment. Sixty of the 196 participants in the L2 group were second-year junior high school students in Japan and were classified as beginner L2 learners. These students had been taking formal English lessons an average of 1.8 years (ranging from1.7 to 1.9 years) at the time of the experiment. No additional placement test was administered for this group. Because the test items were challenging for beginner participants and in order to ensure that the participants were able to perform the task adequately, they were trained on the same lexical items as those included in the experiment a week prior to the task (i.e., the verbs in the target sentences in the experiment) and no special morphology or syntax training was provided.Footnote 7 Including results of the substantial numbers of beginners is important for the study as it provides us with information as to whether or not L1 transfer effect is present in the acquisition of the semantics of predicate aspect. Such a confirmation is needed because, for example, there is a logical alternative whereby all L2 English learners interpret simple past sentences as entailing event completion as being the default option regardless of the type of DP that their L1 possesses. This would parallel Koenig and Muansuwan’s view (Reference Koenig and Muansuwan2000) for the suggestion that in L1 acquisition by default simple past refers to a completed event. If this were the case, the results would show that the L2 beginners interpret an English simple past sentence’s incomplete event as a complete event. As seen in the Results section, our findings rule out this option.

The remaining 136 out of 196 participants were categorized into an intermediate group (n = 96, the mean years of formal English study was 9.2 years, range 6–20 years) or an advanced group (n = 40, mean years of study was13.5 years, range 6–30 years). The intermediate group were university students in Japan and workers in Canada. The advanced group comprised speakers who were university students in Japan, Japanese English teachers in Japan, and workers in Canada. The classification into intermediate versus advanced group was done on the basis of the Quick Placement Test (published by Oxford University Press and the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate, 2001), which evaluates the learners’ vocabulary, grammar, and reading skills. Following Rezai (Reference Rezai, O’Brien, Shea and Archibald2006), participants with scores of 70% and above were classified as advanced (n = 40, mean score 74.5%, range 70%–96.6%), and those who fell into the range of 40%–69% were classified as intermediate (n = 96, mean score 57.5%, range 42%–68%). L1 English speakers (mean age 30.1 years, range 20%–45% were recruited in Ottawa, Canada, and the participants in the L1 Japanese control group (mean age 26.9 years, range 20–40) were recruited in either in Japan or Canada.

The L2 English groups and the L1 English group performed a truth-value judgment task in English, and the L1 Japanese group performed a Japanese version of the truth-value judgment task. The L2 English groups also completed a language background questionnaire (see Kaku, Reference Kaku2009).

Method

The experiment was modeled after Kaku and Kazanina’s (Reference Kaku, Kazanina and Otsu2007) experiment and followed the basic features of a truth-value judgment task (Crain & Thornton, Reference Crain and Thornton1998; Gordon, Reference Gordon, McDaniel, McKee and Crains1996). Participants watched a short animated PowerPoint presentation. In each animation, the objects appeared on the screen and then moved and changed their location and/or appearance as part of an event that they participated in. The effects were implemented using animation effects options in PowerPoint (e.g., appear, disappear, and their motion paths, which enable specifying object movement trajectories). Each event was performed either completely or incompletely; the performance of the event was accompanied by a verbal description narrated by a male speaker (also duplicated by written text appearing on the screen). The participant’s task was to judge the truth-value of a target sentence that appeared at the end of each story.

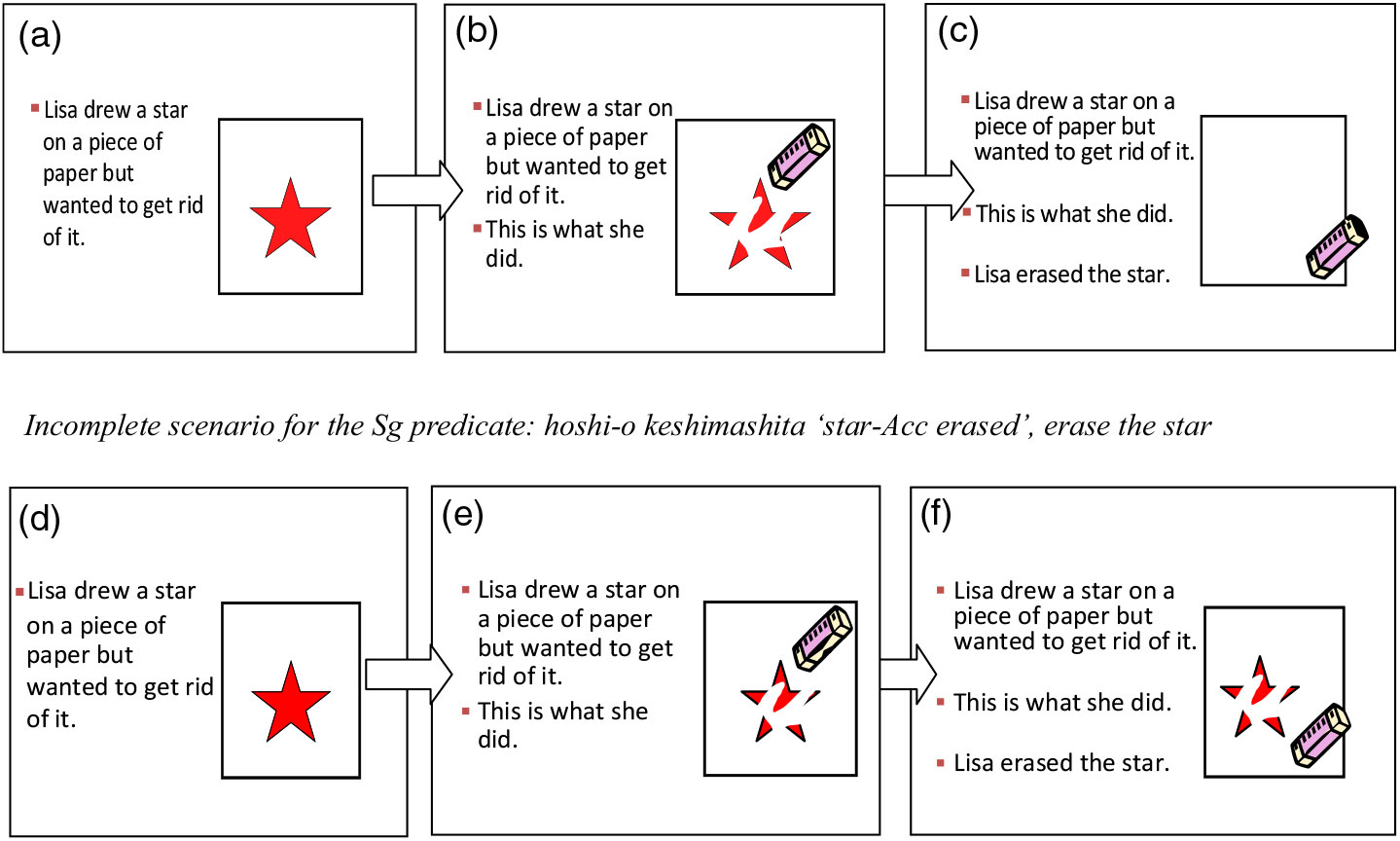

To illustrate this procedure, we provide a depiction of the complete singular version of the star-erasing scenario (Figure 3). The voice announces (and was also duplicated by written text on the screen) that a girl named Lisa has a drawing of a star on a piece of paper (the star drawing appears on the screen; Figure 3a). Then the voice says that Lisa wanted to get rid of the star.Footnote 8 At this point, the eraser appears and starts moving back and forth, which results in gradual disappearance of the star (Figure 3b) until the star is completely erased. The voice says “This is what she did,” and the star disappears completely (Figure 3c). The target sentence Lisa erased the star then appears on the screen, and the participant has to judge if the sentence is a true description of what happened in the story. Participants were instructed to choose an answer from one of three choices: Yes, No, or I did not understand the sentence. When choosing No, participants were asked to elaborate on their rationale in any language. The incomplete singular version of the star-erasing scenario is shown in Figure 3d–f. The incomplete version is identical to its complete counterpart including the target sentence, except for the fact that in the animation the star is erased incompletely (Figure 3f).

Figure 3. A complete (a–c) and incomplete (d–f) sample scenario based on the predicate erase the star. The participant sees a PowerPoint slide with an animated event (shown here as a sequence of pictures a–c or d–f), which is accompanied by a corresponding oral and written description. The participant’s task was to judge the final target sentence using responses Yes, No, or I didn’t understand the sentence. The target sentence is Lisa erased the star in the English version and Lisa-wa hoshi-o keshimashita. “Lisa-Top star-Acc erased” for the Japanese version.

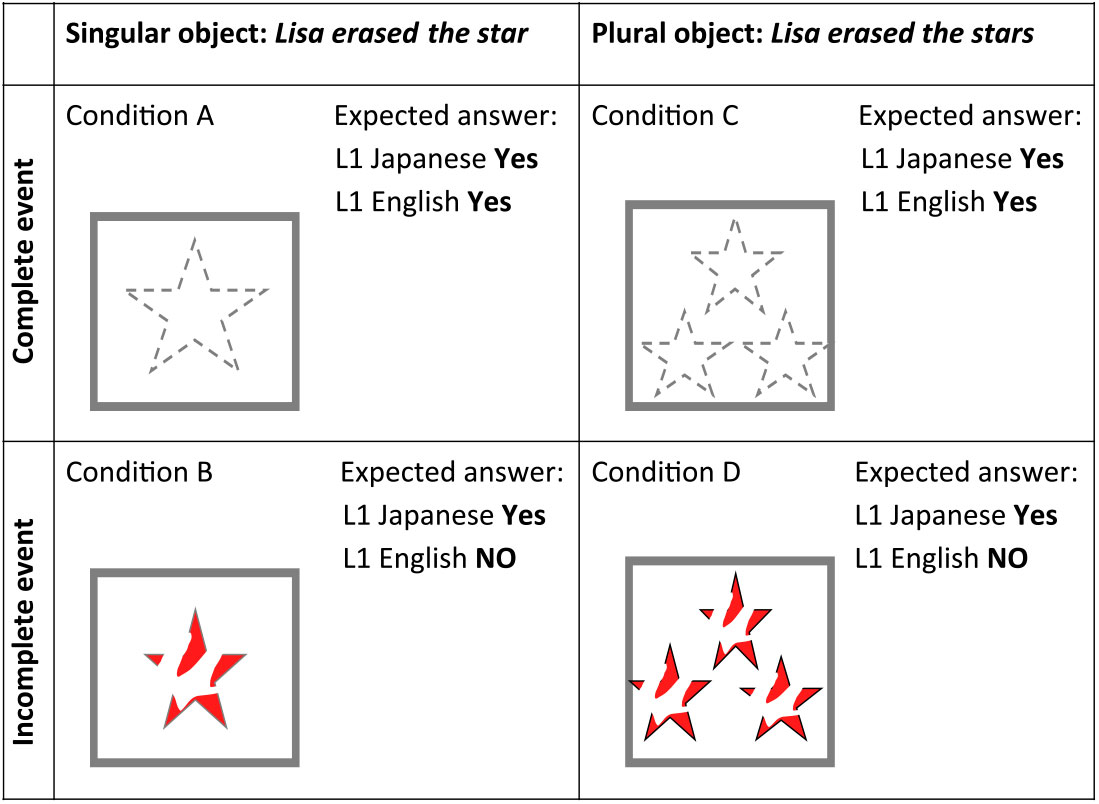

The experiment followed a 2 × 2 design with factors event type (complete/incomplete) and number of affected objects (singular/plural; Figure 4). Conditions A and B both involved a singular object and differed in whether the critical event was performed completely (Condition A) or incompletely (Condition B). Accordingly, the target sentence contained a predicate with a singular bounded object DP (e.g., Lisa erased the star). Conditions C and D followed the same pattern with the difference that multiple objects (2 or 3; see Appendix A) were involved in the event; the target sentence contained a plural bounded object DP (e.g., Lisa erased the stars).

Figure 4. The factorial design of the experiment. An empty dotted star contour represents a star that has been erased completely. The target sentence for Conditions A and B, which contain a singular bounded object DP, is Lisa erased the star for the English version and Lisa-wa hoshi-o keshimashita “Lisa-Top star-Acc erased” for the Japanese version. The target sentence for Conditions C and D, which contain a plural bounded object DP, is Lisa erased the stars for the English version and Lisa-wa hoshi-o keshimashita “Lisa-Top star-Acc erased” for the Japanese version.

Designing stimuli for the experiment presented the following challenge: to find English predicates that are definitively perceived as an accomplishment (i.e., denoting an event that unfolds incrementally toward a clearly defined and unambiguous endpoint). This is a nontrivial task as even the same predicate with a bounded object may be ambiguous between an accomplishment and an activity reading.Footnote 9 Furthermore, the status of each predicate (more precisely, its translation equivalent) with respect to the event cancellation reading in Japanese needed to be verified. We aimed to track the L2 learners’ performance in a situation in which their native (L1 Japanese) and L2 target (corresponding to L1 English) entailment judgments are diametrically opposite; that is, the predicate can denote an incomplete event in L1 Japanese but not in L1 English. In light of these facts, our strategy was to include a wide range of predicates in our experimental materials to make it possible to compile a large enough subset of predicates for the L2 groups’ analyses that includes only those predicates that showed a clearly distinct pattern in L1 English and L1 Japanese (i.e., they were unambiguously rejected by L1 English speakers and clearly allowed an event cancellation reading by L1 Japanese speakers). Hence, 16 sets of four conditions were created using 16 different accomplishment predicates: paint the door(s), build the house(s), erase the star(s), draw the picture(s), eat the orange(s), fill the glass(es), assemble the chair(s), untie the bow(s), empty the bottle(s), remove the cork(s), circle the star(s), shred the document(s), melt the candle(s), disassemble the table(s), unwrap the present(s), and type the name(s). In each scenario we attempted to highlight the desired endpoint/goal for the event by explicitly stating it at the beginning of the story (e.g., in the “erase the star” scenario, the goal was stated as “Lisa wanted to get rid of the star”).

Four presentation lists were created using a Latin square design, and 16 filler animations were added to each list (see Appendix B for a list of experimental materials). The order of items within each list was randomized. Participants were tested individually, in small groups, and in the case of beginners, in a classroom setting.

An animated PowerPoint presentation was presented to them by the experimenter on a laptop screen (when tested individually) or on a projector screen (when tested collectively in small groups or in the classroom setting), and the audio stimuli were played via loudspeakers. The participants wrote their answer at the end of each trial into a response sheet. They were given 25 s to respond to each question.Footnote 10 The experimental session lasted approximately 40 min including a 5- to 7-min break halfway through the task.

Results

Analysis

The dependent variable was binary (the yes/no response from each participant for each trial in each Condition A–D), and hence mixed-effects logistic regression model was applied to raw, trial-level data (Jaeger, Reference Jaeger2008) in R (Version 3.4.3; CRAN project; R Core Team, 2017). The R function glmer (package “lme4”; Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) with a binomial family and a logit link function was used. Two models were constructed: one model was fitted to the data from the L1 English and L1 Japanese groups, and the other to the data from the L2 groups. We included three predictors into the model: language group (for the analysis of L1 group data) or L2 proficiency (for the analysis of L2 group data), number of objects, and event type, as well as their interactions. All fixed factors were coded using sum-to-zero contrast coding (see Tables 1 and 2 below for further details).

Table 1. Results of statistical analysis for Yes-response rates from L1 speakers of English and Japanese (based on all 16 predicates)

Note: The best fitting model included as fixed factors language group (English/Japanese), event type (complete/incomplete), number of objects (“numobj”: singular/plural), and all their two- and three-way interactions; subjects and predicates were included as random factors (abridged R formula: model = glmer [yesrate ~ group*event*numobj] + [1|subj] + [1+event+group|pred], family=binomial). All fixed factors were sum coded as follows: language group: English −½ vs. Japanese ½; event: complete −½ vs. incomplete ½; number of objects: Sg −½ vs. Pl ½. Parameters for the best fitting mode (i.e., coefficient on the logit-transformed odds scale, standard error, and z value) are listed. Effects sizes for fixed factors are shown in the form of odds ratios alongside their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Significant effects and interactions are in bold. Number of observations: 638, groups: subj, 40; pred, 16.

Table 2. Results of statistical analysis for Yes-response rates from L2 learners of English (based on 8 “clear” predicates)

Note: The best fitting model included as fixed factors L2 proficiency (beginner, intermediate, advanced), event type (“event”: complete/incomplete), and number of objects (“numobj”: singular/plural) and all their two- and three-way interactions; subjects and predicates were included as random factors (abridged R formula: model = glmer [yesrate ~ L2proficiency * event * numobj] + [1 | subj] + [1+ L2proficiency + event | pred], family = “binomial”). Fixed factors event type and number of objects were sum coded: eventtype (complete −1/2 vs. incomplete ½); number of objects (Sg −1/2 vs. Pl ½). For the three-level factor L2 proficiency (beginner, intermediate, advanced), one contrast compared beginners to intermediate and advanced leaners lumped together (L2prof1: beginner −2/3, intermediate 1/3, advanced 1/3), and the other contrast compared intermediate learners to advanced learners (L2prof2: beginner 0, intermediate −1/2, advanced 1/2). Parameters for the best fitting mode (i.e., coefficient on the logit-transformed odds scale, standard error, and z value) are listed. Effects sizes for fixed factors are shown in the form of odds ratios alongside their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Significant effects and interactions are in bold. Number of observations: 1509, groups: subj, 196; pred, 8.

Participants and items were used as random factors. Model parameters were estimated using a maximum likelihood method (the Laplace approximation). A maximal random-effect structure justified by the design was used to fit a model (Barr, Levy, Scheepers, & Tily, Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013) whereby random intercepts and slopes were included for every fixed effect. If the maximal model did not converge, the effect structure was simplified stepwise until convergence was obtained using the recommendations in Barr et al. (Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013).

The data from the L1 Japanese and L1 English groups will be reported first and will serve to identify a subset of predicates that clearly differ in terms of the availability of the event cancellation reading in Japanese versus English. This subset of predicates will then be used in the analysis of the L2 learners’ data.

L1 English and L1 Japanese speakers’ performance

Results from the L1 English participants and L1 Japanese participants, who performed a Japanese version of the task, are shown in Figure 5. Both the L1 English and the L1 Japanese speakers overwhelmingly accepted sentences with complete events: the averaged %Yes-responses on Conditions A (Sg/complete) and C (Pl/complete) was 100% for the L1 English and 98.1% for the L1 Japanese groups. On the contrary, the performance on the incomplete-event conditions differed across languages, with the L1 Japanese speakers accepting the target simple past sentence at a higher rate than the L1 English speakers: 63.1% versus 20.6% of Yes-responses, respectively, on Conditions B (Sg/incomplete) and D (Pl/incomplete). These observations were confirmed statistically (Table 1).Footnote 11

Figure 5. Percentage of Yes-responses from L1 Japanese and L1 English groups by condition (based on all 16 predicates). Error bars represent standard error.

The maximal convergent model included the factors language group, event type, and number of objects and their two- and three-way interactions as fixed factors, as well as a random intercept by subject and random intercept and slopes for event type and group by predicate (Abridged R formula: model = glmer [yesrate ~ group*event*numobj] + [1|subj] + [1+event+group|pred], family=binomial). In the model the significant factors were event type (estimate =6.5, SE = 1.2, z = 5.5, p < .001), reflecting higher Yes-rate for complete versus incomplete events, and the interaction Group × Event Type (estimate = 5.0, SE = 1.8, z = 2.8, p = .005) reflecting that Yes-rate for complete versus incomplete events differed for English versus Japanese L1 speakers. As no factors containing number of objects were significant, for the remainder of this section, singular and plural objects will not be considered separately.

Ceilinglike acceptance of target sentences with complete events in the complete-event Conditions A (Sg/complete) and C (Pl/complete) by both groups is in full alignment with our expectations. The overall trend in the incomplete-event Conditions B (Sg/incomplete) and D (Pl/incomplete) is as expected (i.e., Japanese speakers accepted target sentences as descriptions of an incomplete event significantly more than English speakers). A relatively low acceptance rate in the incomplete-event Conditions B and D by English speakers suggests that simple past accomplishments entail completion in English. A significantly higher acceptance rate in the same Conditions (B and D) by the Japanese group reflects the availability of the event cancellation reading in L1 Japanese. However, the fact that the English speakers accepted target sentences with incomplete events in Conditions B (Sg/incomplete) and D (Pl/incomplete) roughly in a fifth of cases and the Japanese speakers rejected them with incomplete events in roughly a third of cases requires a closer examination and points to a possibility of lexical variability among different predicates, as mentioned in the Method section. We therefore examine (Figure 6) the individual predicate data from the L1 Japanese and the L1 English groups with the aim of establishing potential differences among predicates. Such differences, if found, would have implications for theories of aspectual entailments in English and Japanese (see the Discussion and Conclusions section). With respect to the key focus of this research, this analysis is needed to establish a subset of predicates that clearly have a completion entailment in English but not in Japanese and thus are likely to present a challenge for Japanese learners of English.

Figure 6. Percentage of Yes-responses from L1 Japanese and L1 English groups for individual predicates across the incomplete-event conditions (i.e., Conditions B [Sg, incomplete] and D [Pl, incomplete]) collapsed together. In these conditions, Yes-responses reflect availability of the event cancellation reading.

Various types of predicates can be identified on the basis of Figure 6. The first 6 predicates (eat the orange, untie the bow, erase the star, disassemble the table, paint the door, and shred the document) showed an expected pattern of judgments in both L1 English and L1 Japanese. That is, they are rejected with an incomplete event in L1 English and accepted in L1 Japanese. These predicates that yielded diametrically opposite response patterns from the L1 English and the L1 Japanese speakers align perfectly with the predictions of Soh and Kuo’s extended account that links the predicate aspectual value to the object boundedness in Japanese (see Event cancellation: Linguistic analysis section above). We also added to this group the predicates type the name and assemble the chair on the grounds that they similarly show a strong contrast between the L1 English and L1 Japanese readings (at least 50% difference). This was done to maintain a larger set of predicates for the analyses of L2 data. We will use this subset of 8 “clear” predicates to examine whether L2 learners can progress from the L1 Japanese representation of aspect to an L1 English representation of aspect.

Among the remaining 8 predicates, 3 predicates (draw the picture, melt the candle, and unwrap the present) were largely accepted by both L1 Japanese and L1 English speakers with incomplete events, and 5 other predicates (fill the glass, build the house, circle the star, empty the bottle, and remove the cork) were rejected by both L1 Japanese and L1 English speakers with incomplete events. Because in all these cases the L1 English and L1 Japanese judgments are similar, they do not provide information for exploring progression of completion entailments in Japanese learners of English. Although they will not be included in the main L2 data analysis that we discuss next, they provide valuable information on which factors affect completion entailments in English and Japanese. We will return to this in the Discussion and Conclusions section.

L2 English learners’ performance

All analyses of the data from L2 English speakers are performed using the 8 “clear” predicates identified on the basis of the L1 data above. These predicates are the 8 accomplishment predicates that showed a constrast in the presence of an event cancellation reading in L1 Japanese versus L1 English: eat the orange, untie the bow, erase the star, disassemble the table, paint the door, shred the document, type the name, and assemble the chair. Each participant thus provided 2 data points for each of 4 conditions.

“I don’t understand” responses (59 out of a total of 1,568 responses corresponding to 3.8%) from L2 Japanese learners’ of English were excluded from further analyses. All analyses were performed on the remaining 1,509 responses to “clear” predicates. Figure 7 shows the rate of Yes-responses for the beginner, intermediate, and advanced L2 groups on Conditions A–D for the 8 “clear” predicates. The figure also includes the data from L1 Japanese and L1 English, which respectively provide a starting and a target performance level for L2 learners.

Figure 7. Percentage of Yes-responses by condition for beginner, intermediate, and advanced L2 English groups and L1 Japanese and L1 English monolingual controls for 8 “clear” predicates. The corresponding data from L1 Japanese and L1 English, which, respectively, provide a starting and a target performance levels for L2 learners, are also added to the figure for comparative purposes (checkered bars for L1 Japanese and horizontal lined bars for L1 English). Error bars represent standard error.

Figure 7 demonstrates that all three L2 groups showed a ceilinglike performance in Conditions A (Sg/complete) and C (Pl/complete). It also shows that in the critical Conditions B (Sg/incomplete) and D (Pl/incomplete), L2 learners show a clear progression toward targetlike (i.e., L1 English-like) performance with growing English proficiency level. A rather high acceptance of past predicates with incomplete events by beginners (72% in Conditions B and D combined) lowers to 61% in the intermediate group and further to 39% in the advanced group. The maximal model that converged included the factors L2 proficiency, number of objects, and event type and their two- and three-way interactions, as well as random intercept by subject and random intercept and slopes for L2 proficiency and event type by predicate (abridged R formula: [yesrate ~ L2prof * event * numobj] + [1 |subj] + [1+ L2prof + event | pred]). The model output is reported in Table 2, alongside effect sizes and confidence intervals for each simple effect or interaction.

The model showed a significant main effect of event type (estimate = 3.1, SE = 0.5, z = 6.7, p < .001) reflecting a higher rate of Yes-responses for complete versus incomplete events. Two-way interactions Event Type × Number of Objects was significant (estimate = −1.5, SE = 0.5, z = −3.0, p = .002) reflecting the L2 learners’ higher rate of Yes-responses for plural objects with incomplete events. The L2 Proficiency × Event Type interaction was significant for both contrasts, reflecting higher acceptance rates for simple past sentences for beginners versus intermediate and advanced learners (estimate = −2.1, SE = 0.5, z = −4.6, p < .001) and also for intermediate versus advanced learners (estimate = −1.4, SE = 0.7, z = −2.1, p = .039) but only in the case of incomplete events. Finally, the interaction L2 Proficiency × Event Type × Number of Objects was significant (estimate = 2.2, SE = 0.9, z = 2.5, p = .012) confirming higher acceptance rates for simple past sentences with complete versus incomplete events for beginners than for intermediate and advanced learners, especially with singular objects.Footnote 12 Moreover, focusing on incomplete events, the drop in acceptance rates of English simple past accomplishments was especially pronounced with singular incomplete events (beginner 64%, intermediate 46%, advanced 34%), and was also present with plural events (beginner 69%, intermediate 61%, advanced 46%). This significant decrease in acceptance of simple past sentences with incomplete events with increasing L2 proficiency demonstrates that L2 learners progress from an L1 Japanese-like interpretation of English simple past predicates that allows event cancellation toward an L1 English-like one that precludes event cancellation.

Finally, we examined the L2 learners’ data from the incomplete-event Conditions B and D predicate by predicate. Figure 8 shows L2 learners’ performance alongside the performance from L1 Japanese and L1 English speakers for individual predicates. Despite some differences in an exact curve shape for the individual predicates, the majority of individual predicate curves show a stable descending trend found in the averaged data for the incomplete-event conditions. As discussed above and as demonstrated in Figure 8 by the dotted average line, the acceptance rate of simple past predicates with incomplete events (i.e., event cancellation reading rate) is highest in the L1 Japanese and the L2 English beginner groups, then drops in the L2 English intermediate group, and drops even more in the L2 English advanced and L1 English groups.

Figure 8. Percentage of Yes-responses for beginner, intermediate, and advanced L2 English groups and L1 Japanese and English monolingual controls for individual “clear” predicates in Condition B (Sg, incomplete) and Condition D (Pl, incomplete). The black dotted line shows average performance across all predicates. Error bars represent standard error.

Discussion and Conclusions

Our study investigated whether Japanese learners of English can learn to invalidate the event cancellation reading in English and how such understanding develops with increasing English proficiency. We addressed this question by examining how beginner, intermediate, and advanced Japanese learners of English interpret accomplishment predicates that allow an event cancellation reading in Japanese but not in English. Eight “clear” accomplishment predicates that show a distinct pattern in L1 Japanese and L1 English with respect to the availability of the event cancellation reading (84% of acceptance in Conditions B (Sg/incomplete) and D (Pl/incomplete) by Japanese L1 speakers vs. 6% of acceptance by English L1 speakers) were chosen. We found that whereas the beginner learners directly transferred their L1 Japanese representation of predicate aspect onto their L2, the intermediate and especially the advanced learners of English clearly progressed toward the targetlike representation of aspectual entailments in the L2 (73% vs. 65% vs. 39% in incomplete Conditions B [Sg/incomplete] and D [Pl/incomplete] by the beginner, intermediate, and advanced Japanese learners of English, respectively). These results demonstrate that L2 learners can gradually overcome the effects of L1 transfer and learn to invalidate the event cancellation reading in English.

The results from the beginner L2 learners reveal L1 transfer effects as predicted by the full transfer/full access hypothesis (Schwartz & Sprouse, Reference Schwartz and Sprouse1996). If beginner learners misrepresent the English bare nominal star as [−b] (see Figure 9a) and, following their native language principles, do not project NumP and DP, the English predicate erased a/the star will be marked as [−b] at the VP level. Hence, their representation will be consistent with the event cancellation reading. (Figure 9b demonstrates a similar derivation for the plural erased the stars.)

Figure 9. A proposed derivation of (a) the VP “erase a/the star” and (b) the VP “erase the stars” by the beginner Japanese learners of English who use their L1 settings.

Furthermore, the L1 transfer effect of the object boundedness observed in our study is in line with Gabriele (Reference Gabriele2010), who demonstrated that English learners of Japanese use their L1 setting of count noun boundedness and NumP and DP projectionFootnote 13 to compute predicate aspect in the L2. Recall that Gabriele’s (Reference Gabriele2010) study found that English learners of Japanese interpret a simple past sentence with a bare count noun (e.g., kaado-o kakimashita “wrote card”) to mean that all of the cards mentioned in the story are affected (i.e., the cards) and to entail completion. Gabriele argued that the challenge for the learners lies in the absence of morphosyntactic cues (i.e., plural morphology and determiners) for interpreting completion entailment of simple past accomplishment sentences in Japanese. L1 transfer effects of boundedness of count nouns and the projection of NumP and DP were prominent in both the intermediate and the advanced learners in Gabriele (Reference Gabriele2010). In our study, in comparison, L1 transfer effects of both the boundedness of count nouns and the lack of the projection of NumP and DP weaken with growing proficiency; that is, they show progress toward the targetlike interpretation of English predicate aspect. Given this, our results could indicate that it is less complex for the learners to move away from their L1 settings toward the targetlike representation of aspect when there are overt morphosyntactic cues that can aid in the computation of predicate aspect. Most generally, we consider our findings to align with the proposal (Gabriele, Reference Gabriele2010; Gabriele & McClure, Reference Gabriele and McClure2011; Gabriele & Sugita Hughes, Reference Gabriele, Sugita Hughes and Nakayama2015) that morphological encoding of a semantic concept influences L2 learners’ acquisition trajectory of the target like form–meaning mapping (see also Slabakova, Reference Slabakova2008).

At the outset of this article we discussed two options that may enable Japanese learners of English to move away from their L1-like superset interpretation of aspectual entailments in simple past predicates (“a simple past accomplishment predicate need not entail completion”) to a subset interpretation (“a simple past accomplishment entails completion”). First, the learners may benefit from their growing awareness of English determiner and number categories, which contribute to calculation of DP boundedness, which in turn is important for aspectual entailments. Note, however, that our study did not manipulate object boundedness (only predicates with bounded objects were used). Therefore, while our results are compatible with the interpretation that the L2 learners’ progress is aided by their growing understanding of object boundedness in English, a more definitive answer will require further research that includes object boundedness manipulation.

Second, L2 learners may be able to make inferences about the aspectual entailments of English simple past predicates on the basis of missing evidence. The role of missing evidence has been discussed in L1 acquisition in terms of whether learners use this type of information in language learning, and if so, how they use it (Pinker, Reference Pinker1989). The idea is that learners can infer ungrammaticality of certain types of sentences based on the observation of nonoccurrence of them in the input. Some researchers argue that missing evidence does not explain children’s successful language learning because it is too vague to measure if and how children use it in the language learning environment (Pinker, Reference Pinker1989). Similarly, in L2 acquisition, missing evidence is generally not considered as playing a facilitating role for L2 learners to acquire the target language (White, 1989, p. 15; Reference White2003, p. 165). However, a growing amount of research indicates that children do use missing evidence in language acquisition (MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2004; Perfors, Tenenbaum, & Regier, Reference Perfors, Tenenbaum and Regier2006; Tenenbaum & Griffiths, Reference Tenenbaum and Griffiths2001). Following the research demonstrating the role of missing data in L1 acquisition, we would like to argue that L2 Japanese learners of English may benefit from missing evidence. In a nutshell, if L2 learners observe that sentences such as John erased a star are uttered by English speakers (almost) exclusively to describe a completed star-erasing event, the lack of situations in which the sentence refers to an incomplete star-erasing event functions will be interpreted as “missing evidence.”

Let us provide more details about the hypothesis presented above. Starting generally, an important role of missing evidence for learning and generalization has been formalized by Tenenbaum and Griffiths (Reference Tenenbaum and Griffiths2001). These authors laid out a framework that rationalizes these processes in many cognitive domains, including language, in terms of Bayesian statistical principles. The central idea is that the learner entertains a limited number of hypotheses in relation to the data; a hypothesis gains more weight as the learner encounters data instances that fully support the hypothesis. Hence, if a hypothesis is supported by a data pattern that is missing from the input, it will eventually lose to a competitor hypothesis that is reinforced by the input. In our case, imagine that an L2 learner considers a superset hypothesis (“simple past predicates need not entail completion”) and a subset hypothesis (“simple past predicates entail completion”) regarding the aspectual entailments of English simple past accomplishments. During his or her exposure to English, the learner will encounter instances of simple past predicates referring to a past complete event much more often than those in which they refer to a past incomplete event. Thus, the subset hypothesis whereby the English simple past entails completion will be reinforced as the one that is better correlated with the input. Note that this acquisition scenario makes two assumptions that await independent verification: that an appropriate hypothesis space consisting of the subset and the superset hypotheses can be outlined by the learner, and that the learner has an opportunity to both observe events in the real world and hear how they are described by native English speakers.

Completion entailments in English and event cancellation in Japanese: Individual predicate variability

Although the main goal of the study was to investigate whether L2 learners can develop a completion entailment pattern in L2 that is different from their L1 pattern, our well-controlled empirical data from monolingual English and Japanese speakers are valuable for the discussion of completion entailments for the simple past in these languages. The results from a total set of 16 predicates reported in Figure 6 clearly demonstrate significant interpredicate variation in both languages.

In L1 English there is a bimodal distribution pattern among predicates. Namely, for 13 out of 16 predicates, the L1 English speakers either did not accept the event cancellation reading at all (eat the orange, erase the star, disassemble the table, paint the door, untie the bow, type the name, assemble the chair, circle the star, empty the bottle, and build the house) or accepted it at most 20% of the time (shred the document, fill the glass, and remove the cork). However, with the remaining three predicates (melt the candle, draw the picture, and unwrap the present), they accepted the event cancellation reading in 80% of cases. The L1 Japanese speakers’ judgments of the equivalent 16 Japanese predicates are nonuniform as well. In particular, there were 8 predicates for which the event cancellation reading is readily available (acceptance rates of 80% or higher): eat the orange, erase the star, disassemble the table, paint the door, shred the document, untie the bow, melt the candle, and draw the picture. L1 Japanese speakers consistently rejected 4 out of 16 predicates (acceptance rate ≤20%): circle the star, remove the cork, empty the bottle,Footnote 14 and build the house). We discuss why this could be the case below. The remaining four predicates (assemble the chair, type the name, fill the glass, and unwrap the present) yielded an intermediate score between 40% and 60%.Footnote 15 The variation above suggests that the event cancellation reading is not always available in Japanese and unavailable in English with accomplishment predicates. Hence, the object DP boundedness is not the only factor for deriving completion entailment in single past accomplishment sentences. Instead, as discussed below, the availability of either reading is also influenced by the lexical properties of the verb and potentially by other factors.

L1 variability in the acceptance of the event cancellation reading has been previously reported in various languages, including Japanese and English (Arunachalam & Kothari, Reference Arunachalam and Kothari2011; Gabriele, Reference Gabriele2010; Soh & Kuo, Reference Soh, Kuo, Verkuyl, de Swart and van Hout2005; Sugita, Reference Sugita2009; Tsujimura, Reference Tsujimura2003; Yoshida, Reference Yoshida2005, Reference Yoshida and Rothstein2008). Our L1 findings are similar to the findings by Arunachalam and Kothari (Reference Arunachalam and Kothari2011), who examined completion entailments in English and Hindi simple past accomplishments and achievement predicates. Focusing on their findings on English accomplishments, the accomplishments that they tested were all accepted with incomplete events to at least a considerable degree (cover a pot: 54%; draw a flower: 64%; eat a cookie: 67%; fill a glass: 95%). When these simple past accomplishments were tested in another experiment alongside the same predicates used with the particle “up” (e.g., cover up a pot), English speakers’ acceptance rate of the simple accomplishments with incomplete events was even higher (cover a pot: 83%; eat a cookie: 83%; fill a glass: 100%; draw a flower: not tested). In explaining their results, the authors argue that whether an event is considered as (in)complete varies with context, which can differ by the type of object (e.g., a full wine glass typically has more empty space than a full water glass) and the intended use (e.g., filling a water glass for drinking does not require that the water reaches the rim, but such a requirement may be present when one fills up a water glass to measure out a quantity of water).

Similar considerations may apply to our case. The fact that the object type can affect the aspectual entailments of the predicate may explain some of the predicate variability in L1 English. For example, L1 English speakers often accepted the predicate drew a picture in an incomplete scenario, which could be due to the fact that incomplete objects may be considered as acceptable examples of the category denoted by the object NP (the notion of “extended objects” in Parsons, Reference Parsons1990, or “allowed partial objects” in Soh & Kuo, Reference Soh, Kuo, Verkuyl, de Swart and van Hout2005) whereby an incomplete picture may be included in the set of denotations for the relevant nominal). In addition, our L1 Japanese data ie-o tatemashita “house-Acc built” that showed the low acceptance in the incomplete scenario may be explained by this notion of the object type. For example, when someone said Bill-wa ie-o tatemashita “Bill-Top house-Acc built,” there should have been at least one completely built house where a person can live in. In other words, for the Japanese accomplishment predicate “built a house,” incomplete objects (i.e., unfinished house) is not considered as acceptable denotation of the event of built a house (i.e., the notion of “No Partial Object” in Soh & Kuo, Reference Soh, Kuo, Verkuyl, de Swart and van Hout2005, whereby only a complete house is included in the set of denotations for the relevant nominal).Footnote 16

Furthermore, there may be variability due to the intended use. Despite our effort for experimental situations to set an unambiguous intended event endpoint for each experimental scenario (e.g., in the “erase the star” scenario, the agent stated the intention to get rid of the star completely), it could be that some scenarios failed to clearly establish what a targeted complete event was, as a result of which the participant may have concluded that the event goal was reached even when the event was acted out incompletely. For example, in a story with the predicate melt a candle, we used the lead-in sentence Grace wanted to make two small candles out of one big candle to make it clear that the original big candle had to be melted completely. However, both L1 English and L1 Japanese speakers almost always accepted the target sentence Grace melted the candle even in an incomplete scenario in which the candle started melting and stopped when it melted halfway. If participants thought that the wax from a half-melted candle was sufficient to make a second candle, they could conclude that the event had reached its endpoint and accept the target sentence.

Theoretical accounts discussed so far all highlight the relevance of the object DP (its boundedness or the meta-linguistic properties of its referent) in computing the aspectual entailments of accomplishment predicates. It has also been proposed that some of the information that is relevant for computation of the predicate aspect is lexicalized in the verbal root (Rappaport Hovav & Levin, Reference Rappaport Hovav, Levin, Doron, Rappaport Hovav and Sichel2010). Rappaport Hovav and Levin distinguish two main types of verbal roots in accordance with the associated event structure: result roots and manner roots. The idea is that a result root (e.g., empty) focuses on a state that results from some activity, whereas a manner root (e.g., wipe) indicates an activity, which is carried out to achieve a change defined by the predicate. Because a verb such as empty describes a result state that is brought about by removing substance from a place, it is incompatible with an incomplete situation in which that result state is not achieved (regardless of whether the object is bounded, as in “John emptied the bottle,” or unbounded, as in “John emptied bottles”). Relating to our L1 Japanese findings, fill and remove, which yielded unexpectedly high rejection rates in the incomplete scenario, carry the main characteristic of result roots (i.e., they denote a change of state reached by an externally caused activity).

In contrast, a manner root such as draw describes an activity that is associated with means (e.g., inscribing lines with pens or other marking instruments). Such verbs indicate an activity targeted toward achieving the result state indicated by the predicate. However, they may not require the result state to be achieved even with bounded object DPs. Accordingly, three predicates that were often accepted in an incomplete event by L1 English speakers, draw, melt, and unwrap, all have a manner root. Hence, the type of verbal root may need to be considered among factors influencing the aspectual value of the predicate.Footnote 17 Most generally, our findings support the claim that lexical properties of the verb or meta-linguistic knowledge about objects, alongside the boundedness of the object DP, influence the predicate aspectual value.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that Japanese learners of English progress toward an English-like representation of aspectual distinctions (and preempt their L1 option). We have proposed that such a progress was possible due to a combination of grammatical knowledge and observational inference. Further tests for this proposal might be provided by other linguistic phenomena and/or different combinations of L1 and L2, which we leave for future research.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Alison Gabriele, Ana Arregui, Andrés Salanova, and Paul Hirschbühler for their insights on earlier versions of this paper. Thanks are also due to Suzuko Nishihara, Martin Willis, Hiromi Iwamoto, Toshiyuki Yonehara, Vicky Abdenner, Vlasta Cech, Bianca Sherwood, Barbara Greenwood, Eriko Hoshino, Shoko Inoue, and Helmut Zobl, who helped us to recruit some of the L2 English participants in Japan and Canada and to Yuriko Kaku, Shunichi Honda, Michael Schulman, and Chris Sullivan for conducting the experiments on some of the L2 participants in Japan. Thanks are also due to Kumiko Murasugi and Laura Sabourin for arranging space for conducting the experiments in Canada, Marie-Claude Tremblay for recruiting L1 participants, and Marco Llamazares for recruiting participants and conducting some of the experiments on the L1 English group in Canada. We are grateful to Cristobal Lozano who made the placement test (Quick placement test / Local Examinations Syndicate, University of Cambridge) available for this project; to Ian Cunnigs, Michelle Taylor and an anonymous statistics expert on the editorial team of Applied Psycholinguistics for statistical advice; to the editor of this volume, Hayes-Harb; and to three anonymous reviewers for their detailed and constructive feedback on the manuscript. This study was based on Kaku-MacDonald’s doctoral dissertation (2009) and earlier versions of this project were presented at the 8th Tokyo Conference on Psycholinguistics (2007), the 9th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference (GASLA, 2007), and the 32nd annual Boston University Conference on Language Development (BUCLD, 2007). We thank these audiences for their comments and suggestions. The work was partially supported by the HSE Basic Research Program and the Russian Academic Excellence Project ‘5–100’.

Appendix A Target Predicates Tested in the Truth-Value Judgment task (N = 16)

Appendix B English and Japanese Stimuli

(Sg.) = singular object scenario; (Pl.) = plural object scenario; C = context; T = target sentence

1. Paint/door: English (Sg.) C: Ken wanted his yellow door to be red. He bought some red paint and a brush. T: Ken painted a door. (Pl.) C: Ken wanted his yellow doors to be red. He decided to work on two doors. T: Ken painted the doors. Japanese (Sg.) C: ケンは黄色のドアを赤くしたかったので赤いペンキとブラシを買いました。T: ケンはドアをペンキで塗りました。(Pl.) C: ケンは黄色のドアを赤くしたいと考えました。そこで2つのドアに取り掛かることにしました。T: ケンはドアをペンキで塗りました。

2. Eat/orange: English (Sg.) C: Matthew’s lunch box had an orange in it. T: Matthew ate an orange. (Pl.) C: Matthew’s lunch box had oranges in it but there were too many of them so he decided that two would be enough. T: Matthew ate the oranges. Japanese (Sg.) C: マシューはお昼にオレンジを持っていきました。T:マシューはオレンジを食べました。(Pl.) C: マシューはお昼にオレンジを持っていきましたが、あまりにたくさんだったので2つだけにすることにしました。T: マシューはオレンジを食べました。

3. Empty/bottle: English (Sg.) C: Ken wanted to drink a bottle of orange juice but it smelled so bad that he decided to get rid of it. T: Ken emptied a bottle. (Pl.) C: Ken wanted to drink bottles of orange juice but two of them smelled so bad that he decided to get rid of them. T: Ken emptied the bottles. Japanese (Sg.) C: ケンはオレンジジュースを飲みたかったのですが、変なにおいがしてきたのでそれを捨てることにしました。T: ケンはジュースを空にしました。(Pl.) C: ケンはオレンジジュースを飲みたかったのですが、その内2本のジュースから変なにおいがしてきたのでそれを捨てることにしました。T: ケンはジュースを空にしました。

4. Melt/candle: English (Sg.) C: Grace wanted to make two small candles out of one big candle. T: Grace melted a candle. (Pl.) C: Grace has several small candles. She would like to make one large candle out of two small ones. T: Grace melted the candles. Japanese (Sg.) C: グレイスは大きなろうそくをから小さなろうそくを2本作ることにしました。T: グレイスはろうそくを溶かしました。(Pl.) C: グレイスは小さなろうそくを何本か持っていて、その内2本のろうそくを使って大きなろうそくを作ることにしました。T: グレイスはろうそくを溶かしました。

5. Build/house: English (Sg.) C: Bill is a carpenter. He wanted to make a house. T: Bill built a house. (Pl.) C: Bill is a carpenter. He was asked to make several houses but he decided to make three. T: Bill built the houses. Japanese (Sg.) C: ビルは大工です。彼は家を作りたいと考えていました。T: ビルは家を建てました。(Pl.) C: ビルは大工です。何軒かのうちを作るように頼まれましたが、その内3件を作ることにしました。T: ビルは家を建てました。

6. Fill/glass: English (Sg.) C: Sally wanted to have a glass of water. T: Sally filled a glass. (Pl.) C: Sally wanted to have three glasses of water. T: Sally filled the glasses. Japanese (Sg.) C: サリーは水を一杯飲みたいと思ったので水を汲むことにしました。T: サリーはコップを水で満たしました。(Pl.) サリーは水を3杯飲みたいと思ったので水を汲むことにしました。T: サリーはコップを水で満たしました。

7. Remove/cork: English (Sg.) C: Rob wanted to drink a bottle of wine. The bottle had a yellow cork. He wanted to open it. T: Rob removed a cork. (Pl.) C: Rob was going to open bottles of wine for his guests. He decided to open three bottles. T: Rob removed the corks. Japanese (Sg.) C: ロブはワインを飲みたいと思っていました。そのワインは黄色のコルクがついていて、それをあけようと考えました。T: ロブはコルクをとりました。(Pl.) C: ロブはお客のために何本かのワインをあけようと考えていました。結局彼は3本のワインをあけることにしました。T: ロブはコルクをとりました。

8. Disassemble/table: English (Sg.) C: Ken needed to pack up his table so he decided to take it apart. T: Ken disassembled a table. (Pl.) C: Ken was going to move out. He had many tables but he decided to take apart three of them. T: Ken disassembled the tables. Japanese (Sg.) C: ケンは荷造りのためにテーブルを取りはずすことにしました。T: ケンはテーブルを分解しました。(Pl.) C: ケンは荷造りのために、たくさんあるテーブルのうち、3つを取り外すことにしました。T: ケンはテーブルを分解しました。

9. Erase/star: English (Sg.) C: Lisa drew a star on a piece of paper but wanted to get rid of it. T: Lisa erased the star. (Pl.) C: Lisa drew stars on a piece of paper. She decided to get rid of two of them. T: Lisa erased the stars. Japanese (Sg.) C: リサは紙に星を書きましたが、やっぱり取り除くことにしました。T: リサは星を消しました。(Pl.) C: リサは紙に星をいくつか書きましたが、その内2つを取り除くことにしました。T: リサは星を消しました。

10. Assemble/chair: English (Sg.) C: Richard bought a new chair from IKEA and wanted to put it together. T: Richard assembled the chair. (Pl.) C: Richard bought many chairs from IKEA and decided to put together two of them. T: Richard assembled the chairs. Japanese (Sg.) C: リチャードはIKEAで買った新しい椅子に取り掛かろうとしています。T: リチャードはいすを組み立てました。(Pl.) C: リチャードはIKEAで買った新しい椅子のうち2つを作ろうとしています。T: リチャードはいすを組み立てました。

11. Circle/star: English (Sg.) C: Dan painted a star and wanted to draw a circle around it. T: Dan circled the star. (Pl.) C: Dan painted some stars and wanted to draw circles around two of them. T: Dan circled the stars. Japanese (Sg.) C: ダンは星に色を塗った後、その内2つの星の周りに円を書くことにしました。T: ダンは星を円で囲みました。(Pl.) C: ダンは星の色をぬったあと、その内2つの星の周りに円を書くことにしました。T: ダンは星を円で囲みました。

12. Unwrap/present: English (Sg.) C: Phoebe got a present from her friend on her birthday and wanted to see what was inside. T: Phoebe unwrapped the present. (Pl.) C: On her birthday, Phoebe got presents from her friends and decided to see what was inside two of them. T: Phoebe unwrapped the presents. Japanese (Sg.) C: フィービーは友達から誕生日のプレゼントをもらったので中に何が入っているのか見たくなりました。T: フィービーはプレゼントをあけました。(Pl.) C: フィービーは友達からもらった誕生日プレゼントの内、特に2つに何が入っているのか見たくなりました。T: フィービーはプレゼントをあけました。

13. Draw/picture: English (Sg.) C: Rika wanted to create a picture of a girl on the women’s washroom door. T: Rika drew the picture. (Pl.) C: Rika wanted there to be a picture of a girl on each of the women’s washroom doors. She decided to work on only three doors. T: Rika drew the pictures. Japanese (Sg.) C: リカは女性トイレのドアに女の子の絵がほしかったので、ドアにかくことにしました。T: リカは絵を描きました。(Pl.) C: リカは女性トイレのドアに女の子の絵がほしかったので、3つのドアにかくことにしました。T: リカは絵を描きました。

14. Untie/bow: English (Sg.) C: Mary made a bow using a red ribbon. She was not happy with it and decided to undo her work. T: Mary untied the bow. (Pl.) C: Mary made bows using red ribbon. She was not happy with them and decided to undo three. T: Mary untied the bows. Japanese (Sg.) C: メアリーは赤いリボンを作りましたが、満足できなかったため、もう一度やり直すことにしました。T: メアリーはリボンをほどきました。(Pl.) C: メアリーは赤いリボンを作りましたが、満足できなかったため、3つをもう一度やり直すことにしました。T: メアリーはリボンをほどきました。

15. Shred/document: English (Sg.) C: Lucy wanted to discard document. T: Lucy shredded the document. (Pl.) C: Lucy wanted to discard documents and she decided to get rid of three of them. T: Lucy shredded the documents. Japanese (Sg.) C: ルーシーは書類を処分しようとしています。T: ルーシーは書類をシュレッダーにかけました。(Pl.) C: ルーシーは書類を処分しようとしています。そしてその内3枚の書類を破棄することにしました。T: ルーシーは書類をシュレッダーにかけました。

16. Type/name: English (Sg.) C: Mika wanted to make a name tag for her friend Sachiko. T: Mika typed the name. (Pl.) C: Mika wanted to make name tags for her friends Sachiko, Rumiko, and Tomoko. T: Mika typed the names. Japanese (Sg) C: ミカは友達のサチコのために名札を作りたいと考えていました。T: ミカは名前をタイプしました。(Pl.) C: ミカは友達のサチコ、ルミコ、トモコのために名札を作ろうと考えました。T: ミカは名前をタイプしました。