INTRODUCTION

Since Nigeria returned to civilian rule in May 1999, a deluge of political litigation has besieged the country's judiciary. The Supreme Court, in particular, has been summoned relentlessly to arbitrate in a series of constitutional struggles between the Federal Government, based in the federal capital territory of Abuja, and the constituent states of the federation. These inter-governmental conflicts have involved some of the most constitutionally contentious, politically explosive and regionally divisive issues in the federation, including the ownership of offshore oil resources, the distribution of public revenues, the implementation of Islamic Sharia law, the management of the police and public order, and the status and control of local governments.

This article analyses the federalism decisions of the Nigerian Supreme Court during the two constitutional terms of President Olusegun Obasanjo from 1999 to 2007, the longest period of continuous civilian rule in the country's post-independence history. It begins with an examination of the problematic ethno-political, constitutional and institutional contexts of judicial federalism in Nigeria. This is followed by a discussion of fifteen different inter-governmental disputes decided by the Supreme Court during Obasanjo's civilian tenure. A political analysis of the Court's federalism work is then followed by the conclusion, which summarises the findings of the paper.

THE FRAUGHT CONTEXT OF JUDICIAL FEDERALISM

A daunting challenge for conflict management in Nigeria involves the deep centrifugal tensions built into this federation of three major ethnic groups (the Muslim Hausa-Fulani in the north, Christian Ibo in the south-east, and religiously bi-communal Yoruba in the south-west), hundreds of smaller ethno-linguistic communities (the so-called ‘minorities’), and roughly equal numbers of Muslim and Christian adherents. These tensions have fuelled a secessionist war (1967–70), the collapse or abortion of three democratic republics, a succession of military coups, and continuing ethno-political violence.

Nigeria's military rulers sought to contain some of this turbulence by transforming the country from a centrifugal union of three regions at independence in 1960, into a more integrated 36-state federation by 1996. Although this transformation functioned remarkably well to prevent a recurrence of secessionist warfare, the military's authoritarianism encouraged hyper-centralisation and ethno-political contention, producing a crisis of national unity by the end of military rule in 1999. This crisis was underscored by the regional economic nationalism of the Ijaw and other southern Nigerian ethnic minorities in the oil-endowed (but impoverished) Niger Delta, by Yoruba and Ibo ethnic autonomist agitations, by political Islamism in the north, and by broad agitation across the country for a more equitable or decentralised federal bargain. Following the restoration of democracy, this ferment came to infuse the system of inter-governmental relations, whence it filtered into the Supreme Court in the form of federal-state litigation. Yet, as claimed by Donald Horowitz (Reference Horowitz2006: 134), the resolution of intense sectional conflicts is essentially ‘a non-judicial function that risks undermining the acceptance of constitutional adjudication’.

At the same time, the Supreme Court lacked any extensive experience in managing Nigerian federalism before 1999. Rather, judicial federalism was constrained by the abuse of parliamentary sovereignty in Nigeria's Westminster-style First Republic (1960–6), by the brevity of the country's experiment with American-inspired presidential federalism during the Second Republic (1979–83), and by the extended political adventurism and authoritarian centralism of the military, which aborted the Third Nigerian Republic even before its inauguration in 1993.

Like other British Commonwealth federal constitutions (in Australia, Canada and India), Nigeria's Independence Constitution of 1960 creatively grafted the federalist and intrinsically anti-majoritarian principle of judicial review onto a majoritarian parliamentary template. The Constitution established a federal Supreme Court, which exercised original jurisdiction in all inter-regional and federal-regional conflicts. The ceremonial federal president, on the advice of a professional judicial service commission, appointed the justices of the Court. As a further guarantee of judicial review, appeals could be made from the Court to the Privy Council in London.

As underscored by cases such as Balewa v. Doherty and Adegbenro v. AG Federation, the Supreme Court became embroiled in the bitter political litigations emanating from the polarised ethno-regional conflicts of the First Republic (Okere Reference Okere1987). Its curtailment of the federal powers of inquiry over regional institutions in Balewa v. Doherty, in particular, produced acerbic partisan denunciations by the federal parliamentary executive of the ‘dangers of government by the judiciary’ (Mackintosh Reference Mackintosh1966: 42). Ultimately, the judiciary was stripped of much of its independence under the revised republican constitution of 1963. The constitution terminated appeals to the Privy Council and scrapped the judicial service commission, thereby facilitating direct political control of the judiciary. Thereafter, the Supreme Court in the First Republic began to shy away from ‘any desire to become involved in political issues or to stress federalism in the sense of a division of powers’ (ibid.: 85). This intimidation of the judiciary reinforced the undercurrent of political repression and corruption that culminated in the violent overthrow of the First Republic by the military in 1966.

Although it was separated from the First Republic by thirteen years of military rule, and based on a substantially reformed federal constitution (including a reconfigured internal territorial structure and a more robust concept of independent judicial review), the Second Republic replicated the failure of its predecessor. To be sure, the Second Republic witnessed a growing federalist role for the Supreme Court, as evidenced by the Court's intervention in federal-state conflicts over revenue allocation (AG Bendel v. AG Federation), public order (AG Ogun v. AG Federation), and electoral administration (AG Ondo v. AG Federation), among others (Okere Reference Okere1987). This evolving tradition of judicial federalism, however, unravelled with the collapse of democracy and the re-imposition of military rule following fraudulent general elections in 1983.

Both in its first (1966–79) and second (1984–99) phases, military rule in Nigeria was defined by the subordination of the federal structure to the soldiers' unitary command system, with the army headquarters deploying (and redeploying) officers to the states as governors or administrators like any other routine military appointment. The military replaced the rule of law with rule by inherently lawless decree-law. The ‘Federal Military Government’ could ‘make laws for the peace, order and good government of Nigeria or any part thereof with respect to any matter whatsoever’ (Suberu Reference Suberu2001: 31). Such laws routinely included clauses that barred the judiciary from investigating or invalidating any actions of the military. Instead, military-facilitated administrative tribunals, which often co-opted members of the bench and bar, usurped many of the judicial functions of government, while the regular judiciary suffered neglect, manipulation, humiliation and intimidation.

The extinction of state autonomy and the pre-emption of independent judicial review effectively precluded the development of judicial federalism under military rule. A related challenge for constitutional adjudication was the contentiousness (both procedurally and substantively) of the constitution that the military, and its civilian constitutional advisers, bequeathed to Nigerians in 1999.

The 1999 Constitution for the Fourth Republic was neither democratically crafted, nor genuinely federal or conceptually coherent, but was virtually dictated by the military and riddled with ‘loopholes, inconsistencies and illogicalities’ (Adamolekun Reference Adamolekun2005: 401; FRN 1999). The Nigerian Nobel Prize-winning playwright, Wole Soyinka (Reference Soyinka2006), denounced the Constitution ‘as a military document that was imposed upon the nation, forced down its throat, and was designed to concentrate power’.Footnote 1 One prominent legal scholar, citing the Constitution's ‘illegitimacy’ and ‘lack of moral authority’, called for the ‘judicial annulment’ of the document (Ogowewo Reference Ogowewo2000: 1).

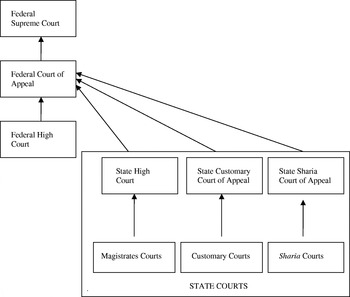

Yet the judiciary in general, and the Supreme Court in particular, are often regarded as a part of, rather than a potential solution to, this constitutional crisis. This is because, reflecting the centrist proclivities of its military promulgators, the 1999 Constitution reinforces Nigeria's unified judicial structure in which federal courts (the Federal High Court and the Court of Appeal) and the sub-federal judicature (especially, the state High Court and Customary, or Sharia, Court of Appeal) are part of a single appellate hierarchy, with the Supreme Court (which exists only at the federal level) at the apex (see Figure 1).

What is more, the 1999 Constitution innovatively establishes a National Judicial Council (NJC) of mainly senior federal jurists, under the leadership of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. The NJC recommends federal and state judges for appointment (by the president or governor subject to confirmation by the Senate or the State legislature), on the basis of nominations received from the federal or state judicial services commissions. The council is additionally charged with the disbursement of monies for the judiciary and the disciplinary control of judicial officers throughout the federation. Although the NJC was designed (and has functioned) to promote the political insulation and professional regulation of the judiciary, critics denounced it as yet another centrist assault on Nigeria's federal system (Belgore Reference Belgore2002: 26).

To reiterate, a context of ethnic diversity and animosity, a legacy of military rule and democratic instability, and a contentious constitutional framework, all pose tremendous challenges to federalism in Nigeria. The generic fragility and immaturity of public institutions in the African milieu (owing to the relatively recent and western origins of those institutions and the intense socio-economic premium on their political manipulation) is the final contextual constraint on the federalism role of the Supreme Court.

Although better resourced and institutionalised than the lower tiers of the Nigerian judiciary, the country's Supreme Court remains a comparatively fragile and nascent organisation (Alabi Reference Alabi2002; Alero Reference Alero2006; Okere Reference Okere1987; Oko Reference Oko2005). In its present constitutional status as Nigeria's apex judicial institution, the Court dates back only to 1963, when it essentially comprised six members (five justices plus a chief justice). Since then, the Court has expanded progressively to its current size of sixteen members, which can statutorily be increased to a maximum membership of twenty-two under the 1999 Constitution. However, all disputes coming before the Court are heard by a quorum of five justices or, in constitutional disputes, by a ‘full’ bench of seven justices, as may be empanelled in both cases by the Chief Justice. In essence, the resolution of constitutional conflicts in the federation can be determined by only four of the Court's members, and a Chief Justice can theoretically ‘pack’ the Court by asking ‘three … justices who share his judicial philosophy to sit with him’ in deciding such disputes (Eso Reference Eso2006: xiii). In practice, the selection of a Supreme Court panel is preceded by a conference of all the Court's justices, and the Chief Justice conventionally picks a panel that is broadly representative of the entire Court.

Considerations of judicial philosophy in the Nigerian context have revolved around the dichotomy between a progressive, activist, radical or liberal orientation, on the one hand, and a more conservative, passive, or politically restrained approach, on the other (Ade.Ajayi & Akinseye-George Reference Ade.Ajayi and Akinseye-George2002; Okere Reference Okere1987; Sagay Reference Sagay1988). The former orientation involves a generous interpretation of the rule of locus standi (the right or standing to sue) in order to broaden public access to judicial redress, as well as resistance to the military's assaults on the rule of law, judicial independence and federalism; the latter approach adopts very rigid or strict standing rules, but is more pragmatic in accommodating the exigencies and legacies of centralised authoritarianism. In Nigeria, these jurisprudential orientations cannot be completely isolated from regional faultlines, because the more populous and politically powerful (but developmentally disadvantaged) north has dominated the military, while southerners (including illustrious activist jurists like Kayode Eso and Chukwudifu Oputa) were traditionally more prominent in the judiciary.

Beginning with the appointment of Justices Mohammed Bello and Mamman Nasir to the Supreme Court in 1975, however, a conscious effort has been made to ensure that the composition of the Court better reflects the plural or ‘federal character’ of Nigeria by injecting qualified, but professionally and chronologically younger, northerners into the Court. This has ensured a north–south balance in the composition of the Court, without redressing the under-representation or non-representation of specific ethnic blocs or even non-ethnic constituencies, such as women, on the bench.Footnote 2 What is more, due to the application of a seniority rule that is based on the number of years spent on the Court before attaining a mandatory retirement age, justices from the previously under-represented north have come progressively to enjoy a near-monopoly of succession to the position of Chief Justice. Thus, while Nigeria's five indigenous chief justices from 1963 to 1987 were from south-western Nigeria, all of the country's four chief justices since 1987 have been northern Muslims, including Muhammadu Uwais, who was Nigeria's Chief Justice from December 1995 until June 2006.Footnote 3

The insinuation of ethno-regional considerations into the Supreme Court highlights broader concerns about judicial integrity in Nigeria, including the ‘pervasive and endemic’ problem of corruption, particularly in the lower tiers of the judicature (Oko Reference Oko2005: 45). The NJC was established to undercut some of the underlying sources of such judicial corruption, including politicisation of the appointment process for justices, the relatively poor salaries and conditions of service in the judiciary, the operational and financial dependence of the judicature on the political executive, and the paucity of effective mechanisms for detecting, investigating and punishing corrupt behaviour. Yet, reflecting the continuing insertion of the courts as putative mediators in corruption-ridden struggles among Nigeria's political elites, judicial malfeasance and manipulation has persisted as a major concern. At the same time, despite some sensational and apparently politically motivated allegations of corruption against the Uwais Court during the Obasanjo years, the Supreme Court would stand firm as a beacon of independence and integrity.Footnote 4

All of these constraints on the judiciary reinforce the perspective that politics in the country and the continent at large takes place outside the universe of institutional restraints. In this perspective, Western-style institutions like the courts, constitutions, legislatures and bureaucracies are mere facades, masking the reality of neo-patrimonial or personal rule, sectionalism, corruption, impunity and violence. Yet, the neo-patrimonial framework of such analysis often trivialises the significant recent advances towards the democratisation, liberalisation and institutionalisation of power in Africa (Posner & Young Reference Posner and Young2007).

In the Nigerian case, the long-standing commitment to federalism as a system of self-rule, shared rule, and limited rule, has traditionally restrained the full-fledged development of neo-patrimonial personal rule. Additionally, the new constitutional provisions on judicial appointments carried some promise for judicial independence as the country transitioned from military to civilian rule in May 1999.

To reiterate, under the 1999 Constitution, the Nigerian President appoints the Supreme Court's Chief Justice and justices, subject to Senate confirmation, on the basis of the recommendations of the NJC, which itself receives advice or nominations from the Federal Judicial Service Commission (FJSC). Both institutions are headed by the Chief Justice and comprise some of the most senior members of the Nigerian bench and bar, plus some representation from outside the legal profession.Footnote 5 The primary contribution of these two bodies has been to promote constitutionality, merit and/or seniority (and, thus, to constrain the discretion of the president) in appointments to the Supreme Court, to the chagrin of the Obasanjo Administration, which in 2006 unsuccessfully schemed to introduce a constitutional amendment that would eliminate the NJC (Ughegbe Reference Ughegbe2006).

Essentially, the basic constitutional requirement for a seat on the Nigerian Supreme Court is qualification as a legal practitioner in Nigeria for at least fifteen years, but with all justices subject to a mandatory retirement age of seventy (up from sixty-five under the 1979 Constitution). Aside from enforcing this requirement, the NJC and FJSC have emphasised the seniority principle, so that the most senior (longest-serving) justice on the Supreme Court has invariably succeeded to the position of Chief Justice, while all recent appointees to the position of justice of the Court have been ‘elevated’ to the position from the next most important court in the country, the Court of Appeal, rather than from lower courts, including the State High Courts, or from outside the judicature.

Once appointed, the Chief Justice cannot be removed except ‘by the President acting on an address supported by two-thirds majority of the Senate’ (FRN 1999, section 292). Similarly, the President can only remove any of the other justices of the Court on the recommendation of the NJC that the justice be dismissed on grounds of infirmity, incompetence or misconduct.Footnote 6 These guarantees of judicial independence augured well for the development of a robust and impartial Supreme Court, despite the broadly problematic context for judicial federalism in Nigeria.

In sum, the 1999–2007 period would be a test of the capacity of Nigeria's revitalised Supreme Court to navigate the complicated ethno-regional, inter-governmental and ideological contours of Nigeria's evolving democratic federalism. Would the Court play a largely conservative or centrist role, in view of the over-centralisation of the 1999 Constitution, the broad suspicion in the traditionally politically dominant north of the southern-led agitation for true federalism in Nigeria, and the perceived northern stranglehold on the key position of Chief Justice? Or would the Court function as a liberal, progressive or activist instrument for the democratic decentralisation of the Nigerian federation after years of hyper-centralising, extra-judicial military rule? Or, alternatively and perhaps more judiciously, would the Court play a more balanced role, reflecting its institutional independence, relatively diversified regional composition, and putative political neutrality?

THE SUPREME COURT AND FEDERAL-STATE CONFLICTS, 1999–2007

Reviewed here are all fifteen major inter-governmental suits decided by the Supreme Court during the 1999–2007 period (see Table 1). These cases span four broad themes, namely the ownership of natural resources, the allocation of public revenues, the status of local government, and the policing of public security.

Table 1 The federalism decisions of Nigeria's Supreme Court, 1999–2007

Source: Adapted from Supreme Court Monthly (2001–6).

Natural resources and the derivation principle

Disputes over natural resources have been especially acrimonious in Nigeria, because the oil and gas assets of a minority-populated region, the Niger Delta, constitute the predominant source of domestic public finances and foreign exchange earnings in the Federation. Unlike the more decentralised regime for natural resource control in federations like Canada and the USA, therefore, the Nigerian Constitution places mineral resources under exclusive federal proprietorship. In addition, the formulae for distributing the centrally collected oil revenues have progressively gratified the Federal Government and the non-oil producing sections, while the Niger Delta remains economically neglected, ecologically endangered and, therefore, increasingly restive. In response to growing agitations in the Niger Delta, the 1999 Constitution, section 162, provides that any act for the allocation of federal revenues by the National Assembly shall apply ‘the principle of derivation’ (that is, the exclusive allocation of centrally collected revenues to their unit-of-origin) to ‘not less than thirteen percent of the revenue accruing to the Federation … directly from any natural resources’.

As with several other provisions in the 1999 Constitution, section 162 is ambiguous and contentious. The Constitution, for instance, does not identify the beneficiary of the derivation rule. While the states are officially assumed to be the legitimate recipient of derivation-based oil revenue transfers, the local governments and village communities of the Niger Delta have staked their own claims to these transfers.

In addition, invoking the American example of private proprietorship of petroleum assets, as well as the Nigerian Constitution's guarantee of the fundamental right to own property (section 43), politicians in the Niger Delta argued for the ownership of oil resources by ‘families and individuals’ in the resource-bearing areas (Ekikerentse Reference Ekikerentse2001: 58). Yet, such campaign for private ownership of prime oil resources is a recipe for chaos, given the fluidity and contentiousness of land tenure rights in Nigeria. This partly informs the Nigerian Constitution's complete vesting of proprietary rights over oil in the Federal Government, ‘notwithstanding’ the document's guarantee of individual property rights (FRN 1999, section 44).

Nonetheless, there is a glaring conflict between the Constitution's attribution of mineral resources to the Federal Government, and the provision that federally collected resource revenues be disbursed partly on a unit-of-origin basis. Reflecting this tension, the Federal Government, supported by the non-oil producing states, conceded the allocation of 13% of onshore oil revenues to the oil-rich states on a derivation basis, but claimed that offshore resources (the source of some 40% of oil revenues) are exempt from the derivation rule because they belong to the Federation as a whole.

In the face of strident demands by the Niger Delta and other southern Nigerian littoral states (mainly Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Cross River, Delta, Rivers, Ondo and Lagos) that offshore resources be attributed to the adjoining states and made subject to the derivation rule, the Federal Government approached the Supreme Court for a determination of the boundaries of Nigeria's littoral states for the purpose of implementing section 162 of the Constitution. But the littoral states challenged the Federal Government's initiation of the suit, AG Federation v. AG Abia & Ors, as politically vexatious, pre-emptive of the National Assembly's revenue allocation powers, procedurally defective on account of the involvement of the non-littoral units, and an abuse of the judicial process. The position of these states reflected their disenchantment with Nigeria's centralised Constitution and with the under-representation of the Niger Delta region on the Supreme Court, and their consequent preference for a political, rather than legalistic, resolution of the dispute.

In July 2001, a seven-member panel of the Supreme Court, with one justice dissenting, said the Federal Government's suit on the derivation rule was ‘properly instituted’ and that the Court ‘has jurisdiction to entertain it’ (SC28/2001a: 89). In his acerbic dissent, however, Justice Adolphus Karibi-Whyte, from the oil-rich Rivers state, argued that the suit ‘was fraught with dangerous political consequences and fit only for political resolution’, warning that any ‘attempt by the Court to exercise jurisdiction in political issues would lure it into a political thicket from which it will be difficult to extricate itself’ (SC28/2001a: 76, 81).

In its substantive ruling on the derivation principle in April 2002, the Supreme Court upheld several counter-claims by the states that challenged the Federal Government's irregular administration of the derivation rule in particular, and centrally collected revenues in general. The Court, however, validated the Federal Government's position that the natural resources on Nigeria's continental shelf belong to the Federation as a whole and, therefore, cannot be said to be derivable from the adjoining littoral states for revenue allocation purposes. The southern boundary of the littoral states, the Court argued, is the low-water mark of their land surface or the seaward limit of their internal waters; it does not extend to Nigeria's continental shelf or territorial waters.

The Supreme Court's decision was informed by several considerations. The first involved a series of colonial-era enactments that consistently defined Nigeria's southernmost regions – the precursors to the current littoral states – as sharing a boundary with ‘the sea’, thereby implying that, ‘by logical reasoning, the sea cannot be a part of the territory of any of the old regions’ (SC28/2001b: 23). A second consideration was the absence in the 1999 Constitution of a provision similar to section 134 of the 1960 Constitution (or section 140 of the 1963 Constitution), according to which the ‘continental shelf of a region shall be deemed to be part of that region’ for the purpose of applying the derivation rule (SC28/2001b: 32–3). Third, the Supreme Court, citing relevant cases in comparable common law jurisdictions, set great store by the fact that Nigeria's continental shelf is ascribed to the country by virtue of international conventions and concessions that ‘do not directly apply’ to sub-federal units, but are given domestic effect by the exercise of federal legislative competence (SC28/2001b: 91).

In political terms, the Supreme Court's blunt rejection of the claims of littoral states to offshore oil revenues reflected and legitimated the fiscal interests of the Federal Government and the non-oil-producing majority of the Nigerian states. It therefore provoked considerable disenchantment in the Niger Delta, whose politicians and intellectuals routinely disparaged the judgement as symptomatic of the ‘age-long neglect’ and deprivation of the region by the rest of ‘the Federation’, as a premeditated and ‘monumental judicial error’, and as an example of ‘supreme injustice’ against the oil-bearing minority communities (Ibori Reference Ibori2002; Ikhariale Reference Ikhariale2005).

More scholarly critics faulted the Court for its strange invocation and strained interpretation of colonial-era proclamations, for disregarding more recent national legislation and international judicial decisions that blurred the dichotomy between onshore and offshore oil resources, for conflating the jurisdiction of the Federal Government over external affairs with the question of the domestic allocation of offshore oil revenues, and for its contradictory posture in pre-empting the allocation of offshore oil revenues while recognising the broad constitutional mandate of the National Assembly to determine the terms of such allocation (Ebeku Reference Ebeku2003; Egede Reference Egede2005).

These bitter criticisms engendered a search for a political solution to the disaffection in the Niger Delta region by the President, the National Assembly, and the governors and leaders of the region. Their protracted and often convoluted negotiations eventually led to the enactment of the ‘Allocation of Revenue (Abolition of Dichotomy in the Application of the Principle of Derivation) Act of 2004’. This so-called Abolition Act provided that an area of ‘two hundred metre water depth Isobaths contiguous’ to the littoral states would be deemed to belong to those states for the purpose of the derivation principle (SC144/2004: 34). Essentially, the Act replaced the onshore/offshore dichotomy with a triadic distinction in oil revenue sources (onshore, offshore within 200 metre depth, offshore beyond 200 metre depth). Although it failed to satisfy the demands of the littoral states for the application of the derivation principle to all offshore oil revenues, the Abolition Act was challenged at the Supreme Court by twenty-two non-littoral/non-oil-producing states, including all nineteen states in the north, and Ekiti, Osun and Oyo in the south-west.

The Abolition Act, the plaintiff non-littoral states argued, had unlawfully ceded portions of the country's territorial waters to the littoral states, short-changed the non-littoral states economically, imposed a ‘legislative judgment’ that reversed the Supreme Court's decision on the ownership of offshore oil revenues, and was, therefore, both in conflict with the Constitution and in contempt of the judiciary (SC144/2004: 26). The Federal Government and the littoral states counterclaimed that the Act was a legitimate law of the National Assembly, including representatives of the non-littoral states.

In a ruling that appeared to contradict its initial position on the derivation rule but helped to redeem its image in the Niger Delta, the Supreme Court, in AG Adamawa & Ors v. AG Federation & Ors, impugned the plaintiff non-littoral states for failing to ‘demonstrate sufficiently and effectively how their civil rights and obligations have been affected by the [Abolition] Act’ (SC144/2004: 42). The Act, the Court found, was consistent not only with the extensive revenue-sharing powers of the National Assembly, but also with the principle of natural justice, as offshore exploration activities negatively impact the ecosystem of the adjoining states. ‘The Act’, wrote Justice Ignatius Pats-Acholonu, would ‘ensure that agitations of short-changing of the littoral oil states are put behind us, and that the oil producing areas in the littoral zones are getting what ought to be due to them’ (SC144/2004: 63). All of this underscored the Court's willingness to abandon a rigid adherence to the constitutional principle of federal ownership of offshore oil for the larger political goals of inter-regional accommodation, the alleviation of ethnic minority grievances, and systemic conflict mitigation.

Revenue allocation and administration disputes

Nigeria's oil-centric political economy and centralised constitutional framework have made revenue-sharing conflicts especially endemic, intensive, pervasive and persistent. To elaborate, the Nigerian Federal Government is constitutionally required to collect the most important public revenues (including mineral, import and company taxes) in the country, and pay them into a general distribution pool, namely the Federation Account. The Account is then shared, according to a law of the National Assembly (based on proposals submitted to the Assembly by the President on the advice of the Revenue Mobilisation Allocation and Fiscal Commission or RMAFC), vertically between the centre, the states and localities, and horizontally among the sub-federal tiers.

Under the revenue-sharing decree-law bequeathed by the military to the civilian government in 1999, revenues in the Federation Account are distributed vertically in the proportions of 48·50%, 24%, 20%, and 7·50% to the federal government, states, localities, and centrally controlled special funds, respectively. Horizontally, the Federation Account revenues devolved to the sub-federal governments are respectively shared among the states and among the localities on the basis of such criteria as inter-unit equality, relative population, social development, own-revenue generation effort, and land mass and terrain.

Federally collected revenues constitutionally exempted from this general vertical/horizontal distributive scheme include: the 13% minimum revenues from natural resources to be paid exclusively to the states of derivation; the net proceeds of centrally collected taxes on capital gains and stamp duties to be paid also to the states of derivation; the income tax of diplomatic, military and police functionaries and residents of Abuja, regarded as independent revenues of the Federal Government; and the value-added tax (VAT), which replaced the state-based sales tax in 1994 and is shared according to a distinct allocation rule, vertically and horizontally. In all, the Nigerian states and localities, in aggregate, depend on federal revenue transfers for 90% of their finances (World Bank 2003: 51).

Reflecting the enormous inter-governmental and ethno-regional stakes involved, the National Assembly failed to pass a substantive general revenue allocation law during the eight-year tenure of the Obasanjo Administration. Yet, the subsisting revenue-sharing decree-law, along with extra-statutory revenue-sharing practices similarly bequeathed by the military, contradicted the provisions of the Constitution in many respects. Consequently, the states turned to the Supreme Court to obtain redress from these violations.

Thus, while upholding federal proprietorship of offshore revenues in April 2002, the Supreme Court invalidated the direct payment by the Federal Government of centrally collected revenues to entities or funds other than the three levels of government. This decision specifically targeted the allocation of 7·5% of the Federation Account revenues to special funds (for national ecological emergencies, development of Abuja, and economic stabilisation), as well as upfront deductions from centrally collected revenues in the form of first-line charges (for external debt payments, oil revenue receipts in excess of a federal budgetary bench-mark, external debt service payments, the judiciary, and federal priority projects). The special funds were statutorily but unconstitutionally codified in the federal revenue decree-law, while the first-line charges lacked a basis both in the Constitution and in any federal statute. The annulment of both these funds and charges potentially represented a huge advance for fiscal decentralisation, as it invalidated the pre-emption of a huge chunk of centrally collected revenues from the general inter-governmental distributable pool (World Bank 2003: 42).

The Supreme Court subsequently revisited the issue of revenue allocation in AG Ogun & Ors v. AG Federation, and in AG Cross River v. AG Federation & Another. In these suits, the Supreme Court reached or reiterated three main conclusions that upheld sub-federal revenue-sharing rights. First, the servicing of the debts of the Federal Government through a direct or first-line charge on the Federation Account is unlawful, because the Account ‘belongs to the three tiers of government and cannot be properly described as the money of the Federal Government’ (SC137/2001: 17). Put succinctly, each government of the Federation must service its debts from its own share of the Federation Account, and not by a direct charge on the Account. Second, the Supreme Court ruled that all monies standing to the credit of the localities in the Federation Account must constitutionally be channelled to the local governments through their respective states, rather than transferred directly by the Federal Government to the local councils.

Third, although it absolved the Federal Government of Cross River's charge of ‘neglect, omission or wilful default’ in accounting for centrally collected revenues, the Supreme Court, in AG Cross River v. AG Federation & Another, conceded that the Federal Government, as the ‘trustee in respect of all monies paid into the Federation Account’, was obliged to render accurate and regular statements of the Account if and when it is clearly requested to do so by the sub-federal beneficiaries of the Account (SC124/1999: 98). The Court also awarded about $17.1 million of verified shortfalls in federal revenue transfers to the Cross River state government (SC124/1999: 98; ICG 2006a: 27).

But the following holding of the Court, in AG Ogun and Ors v. AG Federation, underscored the centre's broad revenue-sharing powers: because it is constitutionally obliged to transfer some portions of federally collected revenues to the states on a derivation basis, the Federal Government cannot be asked, as demanded by the five plaintiff south-western states, to pay all federally collected revenues, net of its own independent revenues, into the general distributable pool or Federation Account. In effect, the Federal Government would continue controversially and unconstitutionally to pre-empt vast amounts of centrally collected revenue from the Federation Account.

The federal executive's revenue-sharing prerogatives were also upheld by the Supreme Court's January 2003 decision, in AG Abia & Ors v. AG Federation, that President Obasanjo was legally competent to modify the existing revenue allocation decree-law in order to bring it into conformity with the Constitution. The ruling followed a petition by the thirty-six states challenging a 2002 presidential order that formally transferred the 7·5% of the Federation Account designated as special funds to the Federal Government in response to the judicial invalidation of direct allocations of the Account to items other than the three tiers of government. The states argued that the special funds should have been prorated to the three levels of government, rather than assigned exclusively to the centre. They also contended that the president's modification of the revenue formula exceeded his constitutional powers. In the opinion of the Supreme Court, however, the modification was consistent not only with the Court's recent fiscal federalism holdings but also with section 315 of the 1999 Constitution, according to which an ‘appropriate authority’ (defined as the president in the case of a federal law) may ‘at any time by order make such modifications in the text of any existing law as … necessary or expedient to bring that law into conformity with the … Constitution’.

In its 2005 decision in AG Abia v. AG Federation & Ors, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the broad powers of the federal executive to administer Nigeria's federal finance. The Abia state government had challenged the authority of the Federal Government to make deductions from the state's share of the Federation Account for the purpose of servicing debts incurred by the state, including its partial obligations for loans acquired by the old Imo state, which was subdivided into Abia and Ebonyi in 1996. But the Supreme Court opined that, as the guarantor of all external loans contracted or inherited by the states, the Federal Government has the ‘responsibility to see that repayments for the loans are paid as and when due’, which ‘can only be done by deductions from the states’ monies available through the Federal Government, namely, the Federation Account' (SC245/2003: 47).

Does the centre's substantial fiscal mandate extend to the enforcement of some transparency in the use of funds by all levels of government? The Supreme Court addressed this issue when Ondo state challenged the authority of the Federal Government to enact and administer a federation-wide anti-corruption law. The Court, in AG Ondo v. AG Federation & Ors, determined that the Anti-Corruption Act, while it contained some irregularities, was generally consistent with the broad constitutional powers of the Federal Government to establish and regulate authorities for enforcing certain national objectives and directive principles, including the abolition of ‘all corrupt practices and abuse of power’ (FRN 1999, section 15). Similarly, the Court, in February 2007, struck out a suit by Abia state challenging the Federal Government over the investigation of the state government by the federal anti-corruption agency, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC).

In essence, the Supreme Court's rulings on revenue allocation upheld the broad powers of the centre to frame and manage the system of inter-governmental revenue transfers. This is consistent not only with the provisions of Nigeria's centrist Constitution, but also with the imperatives of an oil-centric political economy in which the sub-federal tiers are overwhelmingly funded by centrally collected revenues. Yet, the Supreme Court also established the accountability of the Federal Government to the sub-federal beneficiaries of the national revenue-sharing system, including the federal executive's constitutional obligations to channel federal transfers to the localities via the states, thereby reinforcing the powers of state governments over local administrations.

Local government and urban planning

Federal-state conflicts over local governance in Nigeria are significantly rooted in the profound ambiguity surrounding the putative constitutional status of the localities as the third tier (after the centre and the states) of the country's federal system. Since the Second Republic, this three-tier federalism has involved the entrenchment of local government in the Federal Constitution as a way of securing its autonomy from the states and extending self-rule to Nigeria's diverse local communities.

Celebrated by some as an ingenious experiment in decentralist constitutional engineering, the Nigerian concept of three-tier federalism has been disparaged by others as a military-inspired, centrist assault on the traditional federalist prerogatives of the states over local government; an attempt, in other words, to undermine constituent state autonomy from below. Torn between these contending perspectives, the 1999 Constitution is replete with conflicting provisions on local government.

The Constitution assigns the responsibility for the conduct of local government elections to state-level electoral commissions, while giving the National Assembly and the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) the authority to enact and administer laws regarding the ‘registration of voters and the procedure regulating elections to’ local councils (FRN 1999, 2nd & 3rd schedules). Indeed, INEC, which constitutionally conducts all non-local (federal and state government) elections, was transitionally charged by the military with administering the Fourth Republic's inaugural local government elections in 1999, under a federal decree-law that provided for three-year tenure for the local councils.

The 1999 Constitution also provides for the creation of new Local Government Areas (LGAs) by the states, but codifies Nigeria's current 774 areas and empowers the National Assembly to update the number and names of the LGAs in the federation, after ‘adequate returns’ have been made to that effect by the state legislatures (FRN 1999, section 8). The National Assembly is also constitutionally empowered to prescribe the ‘terms and manner’ for the allocation of federal and state revenues to the localities, but each state is authorised by the Constitution to regulate the inter-local distribution of these revenues (FRN 1999, section 162). Finally, despite endowing the National Assembly with significant powers over the election, reorganisation and funding of the localities, the Constitution, section 7, mandates the ‘Government of every State’ to ensure the ‘existence’ of the ‘system of … democratically elected local government councils … under a law which provides for the establishment, structure, composition, finance and functions of such councils’.

This contradictory construction of the constitutional architecture of local government proved to be a recipe for inter-governmental litigation. Thus, in the aforementioned case of AG Ogun & Ors v. AG Federation, the Supreme Court determined that it is the responsibility of each state government to establish and manage the constitutionally mandated ‘State Joint Local Government Account’ (SJLGA), which is a repository for all allocations to the LGAs of a state from the Federation Account and from the government of the state. The Court, therefore, invalidated the establishment of a SJLGA Committee for each state under the subsisting federal revenue decree-law.

The Court also tilted towards states' rights when it ruled in favour of a petition by the thirty-six states challenging a 2001 federal Electoral Act that extended the tenure of local councils from three to four years. Aside from exploiting the contradictions and confusion in the constitutional status and political administration of the localities, the extension reflected the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP)-controlled federal executive's design to ensure that local elections would take place after, rather than before, the anticipated uprooting of the opposition Alliance for Democracy (AD) governments of the south-western states in the centrally administered 2003 national (federal and state) elections. This would ensure that local elections in President Obasanjo's south-western region would be managed and ‘won’ by newly installed PDP governments.

In a March 2002 decision, however, the Supreme Court invalidated the Federal Government's extension of the tenure of local councils. Rather, the Court confined the applicability of the extension to the six LGAs in the federal capital city of Abuja, restricted the electoral powers of the National Assembly at the local level to the procedural (rather than substantive) regulation of local elections, affirmed the inherent powers of the states over their localities, and impugned the National Assembly for encroaching on state autonomy. In the words of Justice Michael Ogundare (SC3/2002: 65–6),

the Constitution intends that everything relating to local government be in the province of the State Government rather than in that of the Government of the Federation. … Other than … power … given to the National Assembly with respect to the registration of voters … the procedure regulating elections to a local government council [and] … statutory allocation of public revenue to local government … I can find no provision in the Constitution empowering the National Assembly to make laws affecting local government.

Ogundare's contention above, which simultaneously proclaims the jurisdiction of the states over ‘everything’ local, but acknowledges the powers of the National Assembly to regulate local elections and finances, ironically illustrates the contradictions in the constitutional status of the localities. Not surprisingly, the management of local government affairs remained a constitutional battlefield between the centre and the states.

Thus, in an April 2004 letter, President Obasanjo asked the Federal Minister of Finance to enforce three conditions for the transfer of federal revenues meant for the localities to the states. First, states were to submit evidence that they have established the constitutionally mandated SJLGA and the ‘basis for sharing allocations from the Federation Account due to their constituent Local Government Councils’ (SC70/2004: 23). Second, the states must also submit evidence of the fulfilment of their own financial obligations to local governments (statutorily fixed nationally at 10% of internal state revenues) through appropriate payments into the SJLGA.

Finally, and most crucially, President Obasanjo directed that Federation Account revenues should not be released for local councils in Ebonyi, Katsina, Lagos, Nasarawa, Niger and any other states where elections had been conducted by state governments in LGAs created after 1999. In the President's words, ‘As the National Assembly is yet to make the necessary consequential provisions in respect of any of the newly created Local Government Areas in the country, conducting any election into them, or funding any of them from the Federation Account, would clearly be a violation of the Constitution’ (SC70/2004: 23).

Consequently, Ebonyi, Katsina, Nasarawa and Niger, all controlled by the PDP, abrogated their new LGAs in order to continue to receive federal transfers to the localities. But the AD-controlled administration of Lagos remained adamant about its authority to create local governments, which it had increased from twenty in 1999 to fifty-seven by 2002. Its recalcitrance partly reflected southern Nigerian opinion that the regional distribution of the 774 LGAs (bequeathed by the northern-dominated military government in 1999) had short-changed the south in general, and Lagos (the most populous southern state) in particular. Thus, the state approached the Supreme Court for a declaration that it is unlawful and unconstitutional for the federal executive ‘to suspend or withhold for any period whatsoever the statutory allocation due and payable to the Lagos state government’ for the benefit of its localities (SC70/2004: 48).

In December 2004 the Supreme Court argued, in AG Lagos v. AG Federation, that the President had no power to hold back federal transfers meant for the localities in Lagos in so far as the money ‘applies to the 20 Local Government Councils for the time being recognised by the Constitution and not the new Local Government Areas which are not yet operative’ (SC70/2004: 48). At the same time, the Court did not derecognise the new Lagos LGAs, which it described as legal but inchoate until their ratification by the National Assembly. The Supreme Court also refused the Federal Government's request for the invalidation of the elections into these areas because, according to the Court, the polls involved several individuals and groups that were not parties to the suit.

The Supreme Court's decision, however, generated contradictory interpretations. The Lagos state government celebrated the decision as a vindication of its struggle for true federalism and against an imperial presidency. But the federal executive, to the chagrin of Chief Justice Uwais, held on to the disputed funds, ostensibly because the creation of new Lagos LGAs had obliterated the legitimate beneficiaries of the funds, but primarily because it was politically embittered by the Supreme Court's implicit endorsement of the AD's overwhelming victory in elections into the areas. Although an informal political settlement secured a partial release of the funds in February 2006 by getting the Lagos state government to downgrade its new LGAs into sub-units of the twenty old areas, the federal executive continued to withhold portions of these funds until after the expiration of Obasanjo's term in May 2007 (Newswatch 6.8.2007: 30).

Any doubts about the states' rights-oriented nature of the Supreme Court's local government jurisprudence were, however, significantly dissipated by the Court's 2006 opinion in AG Abia & Ors v. AG Federation & Ors. This case involved an action by Abia, Delta, and Lagos states, challenging the constitutionality of the Federal Government's ‘Monitoring of Revenue Allocation to Local Governments Act 2005’. Consistent with the tone of President's Obasanjo's April 2004 letter, the 2005 Act had required each of the thirty-six states to establish a SJLGA committee under the chairmanship of the commissioner responsible for local government in the state. The committee, according to the Act, would comprise the following: a commissioner of the RMAFC, not being an indigene of the state; all chairmen of local councils in the state; the Accountant-General of the state; a representative of the Accountant-General of the federation; and a representative of the state revenue board.

The committee's primary function would be to ensure that all statutory federal and state grants to the localities are ‘promptly paid into’ the SJLGA, and distributed among the councils in accordance with the relevant laws of the state legislature (SC99/2005: 60). The committee would also render monthly statements of the SJLGA, on the basis of which quarterly reports will be made available to the National Assembly through the Accountant-General of the Federation. Finally, under the Act, a state government encroaching on funds due to its localities will have its Federation Account allocations appropriately deducted and credited to the affected local council(s), while a functionary involved in such violation would be ‘liable on conviction to a fine twice the amount [involved] or imprisonment for a term of five years or to both such fine and imprisonment’ (SC99/2005: 63).

But the Supreme Court, by a 5:2 majority, determined that the Local Government Monitoring Act violated the federal principle of state autonomy under the Nigerian Constitution. Echoing the Court's previous affirmations of the authority of the states to oversee their localities, the majority upheld the claims of the plaintiff state governments that the Act had usurped the powers of state legislature to provide for the establishment, composition and functions of the SJLGA committee, unlawfully directed the states to include federal appointees on the committee and render reports to the Federal Government, encroached on the powers of the states to regulate the distribution of federal and state allocations standing to the credit of their localities, and unconstitutionally conferred on the Federal Government oversight functions over local administrations within a state.

Essentially, it was the opinion of the Court's majority, particularly Justices Niki Tobi and George Oguntade, that the Act had exceeded the federal powers to allocate revenues to the localities, and assumed the responsibilities of the states to regulate the distribution of such funds to local councils. Although the dissenting Justices Idris Kutigi and Dahiru Musdapher disparaged it as a distinction without a difference, the dichotomy between the federal powers of allocation and state powers of distribution was the conceptual key to the Court's invalidation of the monitoring Act. Inadvertently, however, the invalidation facilitated the systematic hijacking and raiding of local funds by the states, thereby undermining the financial integrity of the localities, and the transparency and effectiveness of the federal revenue-sharing system.

Basically, the Supreme Court's approach in AG Abia & Ors v. AG Federation & Ors was broadly to reaffirm the status of local government as a domain of constituent state autonomy that is protected substantially from the general hegemony of the central government under Nigeria's highly centripetal Federal Constitution. In another example of this states' rights jurisprudence, the Court upheld an action by Lagos challenging the constitutionality of the Nigerian Urban and Regional Planning decree-law. Enacted under military auspices in 1992, the planning law gave the Federal Government broad powers to formulate national standards and policies for urban and regional development throughout the federation. The law also created planning bodies at federal, state and local government levels, including a federal control department with powers to regulate the development of all federal lands in the states. As Nigeria's former federal capital territory, Lagos state contains vast amounts of such federally owned lands, which the Federal Government continued to develop often in violation of the state's urban and regional planning laws. Consequently, the state sought the Supreme Court's invalidation of the powers assigned to the Federal Government under the planning law, including a declaration that ‘by virtue of the 1999 Constitution urban and regional planning … is a residual matter within the exclusive legislative and executive competence of the states’ (SC353/2001: 18).

The declaration was granted by the Supreme Court, which ruled 4:3 in favour of Lagos state. Specifically, the Court voided whole sections of the planning law and upheld the authority of Lagos to regulate the physical development of federally owned land in the state. It also declared urban and regional planning an inherently local affair that is conceptually distinct from national environmental policy-making and, therefore, beyond the purview of any exclusive, concurrent or incidental constitutional powers of the Federal Government.

However, while they impugned portions of the controversial federal planning law as unconstitutional and antithetical to federalism for imposing regulatory bodies and burdens on the states, the three dissenting justices (Chief Justice Uwais and Justices Emmanuel Ayoola and Tobi) declared that the law was broadly consistent with the general powers conferred on the Federal Government under section 20 of the 1999 Constitution to ‘protect and improve the environment’. In the opinion of the dissenting justices, urban and regional planning is a concurrent federal-state subject; to designate such planning as a residual subject for the states would be to ‘stifle the legislative power of the federation in a manner not envisaged by the Constitution’ (SC353/2001: 131).

Policing and public security

Nigeria's unitary police structure provides one of the most glaring illustrations of the political over-centralisation of the country's federalism. The 1999 Constitution (sections 214–16), like the 1979 basic law, establishes the ‘Nigeria Police Force’ (NPF) for the whole country, puts this force under the operational control of an Inspector-General of Police who is appointed by the President, and provides that ‘no other police force shall be established for the Federation or any part thereof’. To be sure, the Constitution authorises the governor of a state to give the State Police Commissioner (the centrally appointed operational commander of contingents of the NPF stationed in the state) ‘lawful directions with respect to the maintenance of public order and safety in the state’. In a crucial proviso, however, the Constitution states that before ‘carrying out any such directions … the Commissioner of Police may request that the matter be referred to the President or such Minister of the Government of the Federation’ as the President may authorise (FRN 1999, section 215).

These centrist provisions provoked considerable political conflict, including allegations by the states regarding the federal executive's partisan or factional use of the NPF to destabilise state governments. Many of these governments consequently agitated for separate state police units, while promoting the establishment of locally controlled quasi-police or vigilante institutions. This conflict over the police ultimately came before the Supreme Court in the form of litigations by Anambra and Kano states, respectively.

The background to Anambra's legal action was most revealing of the violent chicanery of Nigerian politics. Soon after his induction as Anambra governor in May 2003, Chris Ngige fell out with Chris Uba, a local PDP patron with strong Abuja connections, who had helped rig the governor into power, but was now determined to oust the increasingly independent Ngige from office. First, in July 2003, the NPF sensationally abducted Ngige in an unsuccessful bid to force his ouster on the basis of a ‘false’ resignation letter (SC3/2004: 25). Second, following an absurd (and apparently corruptly induced) January 2004 order by Justice Stanley Nnaji of the High Court of neighbouring Enugu state, the Federal Government withdrew Ngige's police security detail on the grounds that he had effectively resigned from office. Finally, in November 2004, arsonists, allegedly acting to Uba's script to have the President declare a state of emergency in Anambra, destroyed the governor's official residence and other government buildings while the police stood idly by.

Consequently, the state government approached the Supreme Court seeking declarations to the effect that the President or Inspector-General of Police has no constitutional authority to remove or withdraw police protection from any governor, or to arbitrarily impose emergency rule in a state. The state government also sought the Court's affirmation of the powers of a state governor (‘subject only’ to the relevant provisions of the Constitution) ‘to give direction to the Commissioner of Police … with respect to the securing and maintaining of public order in the state without interference by the Federal Government or the President’ (SC3/2004: 15).

Embarrassed by the political acrimony of the case, the Supreme Court dismissed many of the declarations requested by the Anambra government as ‘hypothetical’ and ‘speculative’, claiming that there ‘has been no evidence of a declaration of a state of emergency in Anambra state or a threat to declare one that would necessitate the intervention of this Court’ (SC3/2004: 39). The Court also refused to impugn the withdrawal of police security from Ngige because the action was based on the order of a State High Court over which the apex Court has no direct appellate jurisdiction. Moreover, according to the Supreme Court, ‘every person against whom an order of court is made or directed should obey it even if the order seems irregular or void [until] it is set aside on appeal’ (SC3/2004: 20). Nevertheless, acknowledging the ‘siege’ on the Ngige Government, the Supreme Court conceded the Government's ‘innocuous’ claim regarding the constitutional authority of the governor to give rightful directions to the state police commissioner (SC3/2004: 19, 27).

Abuja's police powers were similarly challenged by the opposition All Nigerian Peoples Party (ANPP)-controlled Kano state government in 2006, following a federal ban on the controversial Hisbah corps set up by the state government to enforce Islamic law in Kano, and the detention and prosecution of the Hisbah leadership by the Inspector-General of Police. The ban was imposed amidst the Hisbah's move to enforce a controversial gender-segregated transportation policy in Kano, as well as allegations by the Federal Minister of Information that the Hisbah leadership had threatened national security by seeking intelligence training for its members from foreign Islamist governments. But the Hisbah remained quite popular locally for bringing down crime rates and providing quasi-official employment for thousands of people, and the federal ban was arguably designed to deprive the ANPP government of a potential counterweight to the PDP-controlled federal police in the run-up to the fraudulent and violent 2007 elections.

Challenging the federal ban, Kano state government asked the Supreme Court both to declare the establishment of the Hisbah as consistent with the constitutional powers of the Government to legislate ‘for the peace, order and good government of the State’, and to restrain the Inspector-General from arresting or harassing the Hisbah members (FRN 1999, section 4; SC26/2006: 2). But the Court struck out the challenge on the ground that the conflict did not entail a constitutional confrontation over the relative powers of the Federation and its constituent states. Rather, it involved an administrative dispute between an agency of the Kano government (the Hisbah) and two agencies of the Federal Government (the police and the Federal Information Ministry), as well as a crime-related cause, both of which are constitutionally outside the original (as distinct from appellate) jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

Thus, while effectively preserving the centre's police powers in AG Kano v. AG Federation, the Supreme Court sidetracked the constitutional conundrum and sectarian minefield around the legality of Sharia implementation in Nigeria. Indeed, as claimed by the President of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA), the ‘Sharia issue has been so politicised that a constitutional court proceeding … to determine the constitutionality or otherwise of the Sharia enactments will place the court dangerously in a no-win position where its decision one way or the other will hardly command acceptance no matter how right or correct the judgment may be’ (The Guardian 23.3.2000).

The Supreme Court similarly sidestepped, in Plateau State & Another v. AG Federation & Another, a potentially momentous legal tussle over the Federal Government's emergency and public order powers. This action challenged Obasanjo's suspension of the elected executive and legislature of Plateau state for six months (18 May–17 November 2004), following an outbreak of ethno-religious violence in the state. However, the Supreme Court ruled the suit incompetent because it was instituted during the six-month emergency period by the suspended legislators in the name of Plateau state without the authorisation of the incumbent, centrally imposed, administration in the state. That the emergency administration could not possibly have authorised a legal action against its own validity did not stop the Supreme Court from dismissing the action as outside its constitutional jurisdiction for disputes ‘between the Federation and a State’ (SC113/2004: 161; FRN 1999, section 232).

APPRAISING THE FEDERALISM WORK OF THE SUPREME COURT

Echoing broad public opinion in Nigeria, Obasanjo in February 2007 applauded the Supreme Court for ‘being an impartial, courageous and principled arbiter … in a manner which has earned it the respect, confidence and indeed admiration of actors across the entire political spectrum’ (Lohor Reference Lohor2007). Undoubtedly, the Court's decisions have variously demonstrated its value as a defender of federalism, a guardian of democracy, a bulwark for constitutionalism and the rule of law, a force for political pluralism and institutionalism, and a credible, but often cautious and discreet, intervener in the volatile political conflicts that plague Nigeria.

In managing Nigeria's federal-state conflicts, the Supreme Court has functioned more as a trusted interpreter of the Constitution or as an instrument for policing the federal balance (or imbalance) of power written into this basic law, than as a conservative protector of federal hegemony or an activist promoter of state autonomy. Reflecting the inherent centralism of the 1999 Constitution, seven of the Court's fifteen federalism decisions have buttressed federal supremacy. Yet, the Supreme Court's clear endorsement of states' rights in four cases, and even-handed affirmation of both federal prerogatives and state autonomy in four other rulings, indicates the Court's relatively balanced adjudication of federal-state conflicts.

There can be little doubt that this relatively impartial or balanced adjudication of centralising and decentralising pressures in the Nigerian federation has been greatly facilitated by the substantial political insulation of the judiciary under the much-vilified 1999 Constitution. For all the criticisms of the document, the 1999 Constitution promotes judicial federalism, not least by guaranteeing the autonomy of a premier Court whose composition is not directly controlled by the federal executive, but is nominated by the FJSC, recommended by the technocratic NJC, appointed symbolically or formally by the president, and confirmed by the Senate.

Yet, several inter-related contradictions and constraints beset the Supreme Court's federalism work. These relate to the Court's limited impact on the resolution of violent conflicts, its exposure to ethno-regional fissures, its split along federal centralisation v. states' rights lines, its unenviable task of interpreting a conflicted Constitution, and its impotence regarding the enforcement of judicial decisions.

First, it is doubtful whether the Court can accurately be described as an effective institution for the ‘non-violent resolution of conflicts’ in Nigeria's deeply fragmented federation (Alemika Reference Alemika2006: 512). Instead, despite the best efforts of the Court to mediate federal-state relations, the operation of the federal system remained ‘deeply flawed, contributing to rising violence’ (including conflicts in the Niger Delta and over the Sharia), involving at least ten thousand deaths during the Obasanjo years (ICG 2006b: i).

Yet it may be unrealistic to expect the Court to significantly reduce levels of conflict and instability in the Federation. The primary role of the Court is strictly not the resolution of ethno-political conflicts, but the determination of specific inter-governmental disputes through the interpretation of the Constitution and other legal provisions. Indeed, as we have seen, the Court has periodically resisted its entanglement in the ethno-political ‘thicket’ by technically sidestepping some of the federation's more explosive sectarian or partisan disputes. What is more, such disputes, including the conflict over offshore oil revenues, have actually been managed more effectively by political accommodation or negotiated legislation than by judicial arbitration.

Second, although it would be misleading to portray the Supreme Court as a captive of primordial interests, such sectionalism does constitute a potential threat to the internal cohesion, public legitimacy, or conflict resolution capacity of the Court. So far, making the Court both as politically insulated and regionally inclusive as possible has significantly mitigated this threat. Indeed, during the 1999–2007 period under review, the successive seven-member panels of the Court that considered the various constitutional disputes were almost always constituted in such a manner as to include at least three members each from the north and south. That these regionally inclusive panels were able to reach unanimous decisions in all but three of the fifteen disputes considered here is an indication of the relative professionalism and non-sectionalism of the Supreme Court. The three exceptions involved (i) the preliminary consideration of the Court's jurisdiction in the offshore oil case (AG Federation v. AG Abia & Ors), (ii) the conflict over the urban and regional planning decree-law (AG Lagos v. AG Federation & Ors), and (iii) the dispute over the monitoring of local government revenues act (AG Abia & Ors v. AG Federation & Ors).

Of these three cases, only AG Federation v. AG Abia & Ors highlighted a clear ethno-regional fissure on the bench. In his lone dissent in this case, Karibi-Whyte passionately voiced the opposition of his own Rivers state and the wider Niger Delta region to the Federal Government's move to obtain judicial affirmation of the Federation's exclusive constitutional rights to offshore oil revenues. Arguing that the Supreme Court should decline jurisdiction in AG Federation v. AG Abia & Ors and leave the matter for political resolution, Karibi-Whyte denounced the Federal Government's legal action as ‘improper, irregular … unconscionable … oppressive, reckless and vindictive’ (SC28/2001a: 81). But he was isolated on a Supreme Court bench whose six other members came from outside the core Niger Delta region, including two other justices of southern Nigerian origin, Michael Ogundare and Emmanuel Ogwuegbu, and four northern Nigerians, namely Chief Justice Uwais, and Justices Salihu Belgore, Abubakar Wali and Idris Kutigi. As we have seen, however, Karibi-Whyte's minority position was ultimately vindicated by the Supreme Court's subsequent validation of a politically negotiated legislation that overturned the Court's initial support for exclusive federal control of offshore oil revenues.

The two other non-unanimous decisions of the Supreme Court, AG Lagos v. AG Federation & Ors and AG Abia & Ors v. AG Federation & Ors, highlight what may be considered a third constraint to the federalism work of the Supreme Court, namely the existence of a division on the bench ‘between federalist judges … and … more conservative, unitary-minded justices’ or between so-called ‘hard and soft federalists’ (Arthur-Worrey Reference Arthur-Worrey2006: 493; Alemika Reference Alemika2006: 523). In AG Lagos v. AG Federation & Ors, Justices Samson Uwaifo and Akintola Ejiwunmi (from the south) as well as Justices Sylvester-Umaru Onu and Umaru Kalgo (from the north) constituted the Court's majority, which ruled the federal urban and regional planning law a ‘relic of military government … a clear breach of the principles of federalism and an incursion into the legislative jurisdiction of the states’ (SC353/2001: 14, 37). The dissenting, more ‘unitary-minded’, justices in this case were Chief Justice Uwais (north) and Justices Ayoola and Tobi, both from southern Nigeria. Of the three, Tobi was by far the most passionate in upholding what he described as the ‘unitary provisions’ in Nigeria's ‘federal Constitution’. ‘Neither other federal constitutions nor theories and principles in federalism’, he contended, ‘will be a substitute to the provisions of our Constitution’ (SC353/2001: 137–8).

Yet Tobi subsequently wrote the lead judgement of the Supreme Court's 5:2 decision, in AG Abia & Ors v. AG Federation & Ors, that invalidated the ‘Monitoring of Revenue to Local Government Act’ as an invasion of the autonomy of the states. ‘The word “monitoring”’, he wrote, ‘conveys some element of policing the State Governments … In terms of showing the strength of the Federal Government, it is a very arrogant word that spells … doom in a federal structure’ (SC99/2005: 57). Justices Pats-Acholonu, Oguntade and Walter Onnoghen, all from southern Nigeria, as well as Justice Kalgo (north), supported Tobi's lead judgement.

Justices Kutigi and Dahiru Musdapher, both from northern Nigeria, wrote dissenting opinions that echoed Tobi's previous stance about the Court's obligation to uphold, rather than jettison, the inherently centrist features of Nigeria's ostensibly federal Constitution. For Tobi, however, the establishment of an over-centralised federation is not necessarily inconsistent with the preservation of some degree of constituent state autonomy, and the monitoring act was particularly obnoxious because it disrespected the Supreme Court's previous pronouncements about the inherent status of local government as a residual subject for the states (SC99/2005: 65).

Nonetheless, the country's contradictory constitutional framework of unitary federalism remained a significant constraint on the federalist work of the Supreme Court, producing decisions that often upheld the political hegemony of the centre, sometimes affirmed the rights of the states, and at other times ambivalently espoused both federal centralisation and state autonomy. At various times, the justices of the Supreme Court bemoaned or at least acknowledged the conflicted nature of the 1999 Constitution in entrenching ‘a hybrid of a Federal and Unitary System of Constitutional Government’, as claimed by Justice Ejiwunmi (SC200/2001: 167). In AG Ondo v. AG Federation & Ors, for instance, Uwais (SC200/2001: 40) argued as follows:

I am afraid it is the Constitution that makes provisions that have facilitated breach of the … cardinal principles of federalism, namely, the requirement of … autonomy of the state government and non-interference [by the Federal Government] with the functions of State Government … As far as the aberration is supported by the provisions of the Constitution, I think it cannot be argued that an illegality has occurred.

Similarly, for Tobi, ‘We may have our own aversions and prejudices on the unitary context of some provisions of our Federal Constitution but there is nothing we can do as judges’ (SC353/2001: 137). Indeed, some Supreme Court justices like Ogundare and Musdapher tried to rationalise the Constitution's centripetal federalism as a ‘pragmatic’ response, by the ‘framers of the Constitution, in their wisdom’, to the imperatives of ‘good governance’ in the Nigerian context (see SC227/2002: 33–4; SC99/2005: 90). Ultimately, the broad approach of the Supreme Court (most closely approximated by Tobi) to this unitary-federal constitutional conundrum was generally to uphold the centrist features of the 1999 Constitution, while preserving some relatively limited, but still significant, sphere of constituent state autonomy, particularly with regard to the administration of local government.

Yet even this concession to state autonomy was endangered by the disobedience, selective enforcement or deliberate misapplication of Supreme Court orders by the federal executive. The most widely cited instance of this executive contumacy or outlawry was Obasanjo's continued withholding of the Lagos local government funds in apparent defiance of the Supreme Court's ruling in AG Lagos v. AG Federation. Another was the federal executive's persistent unilateral diversion of billions of dollars in centrally collected revenues into various ‘special’ programmes or funds, and away from the common inter-governmental distributable pool, in violation of the Court's invalidation of upfront or extra-constitutional deductions by the executive from these revenues (see Newswatch 9.4.2007: 42–9; Agbese Reference Agbese2007: 16).

Indeed, violations of Court orders were a pervasive feature of Nigerian politics at both federal and sub-federal levels during the 1999–2007 period. This disrespect for the judiciary, which provoked a nation-wide strike (boycott of the courts) by the NBA during March 2006, was bluntly denounced by Uwais in the following words: ‘disobedience to Court orders … in a democratic set-up like ours … is an affront to the Constitution and a clear evidence of bad governance. Those in authority and their agencies cannot pick and choose what Court orders to obey’ (The Comet 6.12.2005: 4). Ultimately, in the absence of an autonomous coercive or enforcement capacity by the courts, the effectiveness of judicial decisions will depend significantly on the ability of the political opposition and organised civil society to restrain the propensity for executive political lawlessness.

* * *