Introduction

Background and Rationale

Real-world public health emergencies and exercises have shown that public health leaders frequently fulfill critical incident management roles that differ from their routine job functions, a departure from what they know and do routinely. Coupled with limited time and resources, variable experience managing emergencies and inconsistent fluencies with incident management and coordination roles among leaders may adversely impact the overall effectiveness of public health emergency responses.

While training and exercise programs as educational interventions are commonly used methods for fostering and transmitting the appropriate emergency management knowledge, skills, abilities, and attitudes (KSAA) to the public health responder workforce, best practices in these areas remain undetermined. To address this challenge, we conducted a scoping review of existing literature to describe prevalent methods and opportunities to improve educational interventions applicable to developing public health emergency response leaders.

This scoping review’s objectives aimed to (1) identify and summarize relevant peer-reviewed and gray literature that describes existing approaches, systems, methods, techniques, and/or modalities directly related to developing public health emergency response leaders; (2) identify and summarize key themes in existing literature of non-public health disciplines (ie, education/adult learning, military science, leadership studies, and crisis leadership/management) that can be applied to inform the development of public health emergency response leaders; and (3) describe emerging priorities and opportunities to improve the effectiveness of educational interventions for developing public health emergency response leaders. Specific assumptions regarding the focus and target audience of this review, as well as clarification of distinctions among commonly used terms, are included in the Methods section.

Methods

Assumptions and Definitions

Public health emergency response leaders, rather than personnel engaged in emergency response activities (eg, emergency medical technicians, first responders, health care professionals), are the intended focus and target audience of this review. This review is not intended to create, develop, or define leadership competencies or the content that comprise leadership competencies. In addition, we made the following distinctions in commonly used terms to clarify the parameters of this review.

-

1. Leader vs Leadership

-

- Leader: individual(s) responsible for directing others and/or making decisions.

-

- Leadership: specific competencies, skills, attributes, qualities, and actions pertaining to making decisions or directing, managing, or influencing others in the interest of achieving tactical or strategic goals.

-

-

2. Training vs Exercises

-

- Training: imparting knowledge and skills to a target audience using 1 or more modalities (eg, didactic, online, just-in-time) for grasping and retaining imparted knowledge and skills.

-

- Exercises: 1 or more modalities (eg, tabletop, functional, full-scale exercises) that provide participants with the opportunity to translate into practice the knowledge, skills, and abilities imparted/received during training.

-

-

3. Attitude: the acceptance and perception of effectiveness of training and exercise modalities. Attitude is also reflected by demonstrated receptiveness to participate in training and exercise activities and may be assessed (in part) by how well participants retain imparted knowledge, skills, and abilities, and translate these into practice.

Literature Source, Search Strategy, and Eligibility

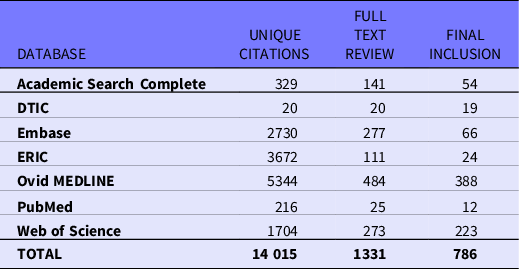

Working with an informationist, we developed search strategies using consistent search terms and queried 6 English language bibliographic databases: Academic Search Complete, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Embase, Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, and Web of Science. We also identified additional articles by manually searching the Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC).

Our search for relevant articles encompassed the following fields: public health; disaster medicine; education/adult learning; military science; leadership studies; and crisis leadership/management. The articles identified for this review were published between January 1990 and October 2017. Tailored search strategies for each database are provided in the Online Supplement.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

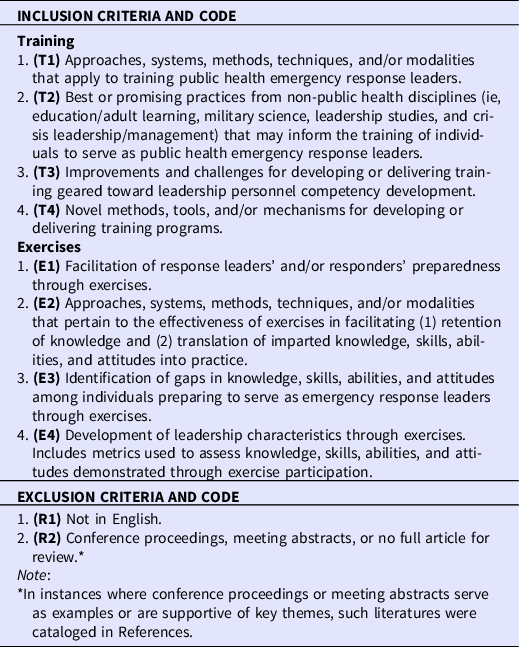

We established specific inclusion and exclusion criteria with corresponding codes for this review (Table 1). Each article included in full-text review covered at least 1 topic related to existing practices in developing public health emergency response leaders through training (designated by inclusion codes T1-T4) and exercises (designated by inclusion codes E1-E4). As this may be viewed as an emerging discipline, we did not apply exceedingly rigid exclusion criteria to ensure that any evidence that could positively influence current practices is captured.

Table 1. Article inclusion and exclusion criteria with corresponding code

Article Selection Process

The following process in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines was used to select articles for review (Figure 1). Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin1 Citations for all articles identified in this review were documented and organized using EndNote® (Philadelphia, PA, USA).

-

1. Identification – checked redundancy to maintain uniqueness of each article identified in the literature search

-

2. Screening – screened the title and reviewed the abstract of unique citations based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine eligibility for full-text review. Each citation was catalogued by the article inclusion or exclusion criteria code(s) (see Table 1) described previously

-

3. Eligibility review – reviewed full-text articles to determine final inclusion or exclusion in the scoping review

Figure 1. Article selection process.

Content Extraction

To identify key themes, 2 co-authors (YL and NNP) independently reviewed and conducted structured content extraction from each article captured for a full-text review, including a brief synopsis and keywords. Keywords were manually documented and included training and/or exercise approaches, systems, methods, techniques or modalities, learning theories, evaluation methods and outcomes (eg, pre-/post-educational intervention surveys on self-reported gains), leadership characteristics or strategies, tools, guidance, and needs in the context of – or potentially applicable to – developing leaders. The co-authors also examined the content extracted to identify and discuss emergent themes and achieve consensus surrounding representative articles for resultant themes.

Study Selection

Using the methodology described, we identified 14 015 citations (excluding duplicates) in the title/abstract screening stage. Subsequently, title/abstract screening enabled our review to narrow the list of articles to 1331 for a full-text review. Finally, 786 articles, predominantly descriptive and qualitative studies, met eligibility criteria following a full-text review (see Figure 1; Table 2).

Table 2. Articles included in the scoping review

Results

General Study Characteristics

We identified articles as meeting 1 or more of the inclusion criteria related to the major categories of training or exercise. Many articles fulfilled multiple eligibility criteria and frequently addressed both training and exercises.

Of the 786 articles included in the scoping review, descriptive and qualitative studies (n = 740, 94.1%) predominated. By contrast, quantitative studies (n = 46) represented 5.9% of the articles.

Across all databases, a significantly larger number of articles addressed training as opposed to exercises. Specifically, 675 articles pertaining to training met eligibility criteria (n = 675/786, 85.9%), whereas 234 articles addressing exercise methods met eligibility criteria (n = 234/786, 29.8%). In addition, 192 articles covered multiple training criteria (n = 192/786, 24.4%), 87 articles discussed multiple exercise criteria (n = 87/786, 11.1%), and 64 articles addressed both training and exercises (n = 64/786, 8.1%).

Delineating articles further by inclusion criteria and corresponding codes referring to specific topics in training (T1-T4) and exercises (E1-E4) (see Table 1), 285 articles (n = 285/786, 36.3%) described approaches, systems, methods, techniques, and/or modalities that may apply to training response leaders (T1). Two hundred twenty articles (n = 220/786, 28.0%) described best or promising practices from non-public health disciplines that may inform the training of individuals to serve as public health emergency response leaders (T2). One hundred forty-one articles (n = 141/786, 17.9%) focused on improvements and challenges for developing or delivering training geared toward the development of leadership personnel competency (T3). Finally, 195 articles (n = 195/786, 24.8%) highlighted novel methods, tools, and/or mechanisms for developing or delivering training programs (T4) (Table 3).

Table 3. Article statistics associated with training and exercise inclusion criteria

Notes:

* All percentages are calculated using the total number of articles (N = 786) as the denominator; articles may address training, exercise, or both and can pertain to 1 or more subcategories within training or exercise, thus total percentages exceed 100.

Among all articles included in this review, 87 (n = 87/786, 11.1%) reported on the facilitation of response leaders’ and/or responders’ preparedness through exercises (E1). Ninety-eight articles (n = 98/786, 12.5%) addressed approaches, systems, methods, techniques, and/or modalities that pertain to the effectiveness of exercises (E2). Another 86 articles (n = 86/786, 10.9%) pertained to identification of gaps in KSAA among individuals preparing to serve as emergency response leaders through exercises (E3). Finally, 48 articles (n = 48/786, 6.1%) focused on the development of leadership characteristics through exercises (E4) (see Table 3).

Thematic Findings

We assigned each article that met inclusion criteria 1 or more keywords that encapsulated the main themes identified in the article. These selected keywords formed subthemes; related subthemes were combined. From these, the following 5 themes emerged:

Theme 1: Experiential Learning – Incorporating Realism into Training and Exercises

Existing literature describes experiential learning as an established approach for designing and delivering training and exercise activities, specifically in supporting interactive learning environments. The objective of experiential learning is to provide learners with a realistic context from which to gain knowledge and develop skills. An important form of experiential learning is problem-based learning (PBL). In contrast to didactic learning, which emphasizes direct presentation of facts and concepts, PBL is a teaching method that conveys concepts and principles in the context of complex real-world challenges. Ideally, PBL encourages critical thinking, logical reasoning, decision-making, and teamwork. PBL tools such as scenario-based training, case studies, and serious/applied games facilitate the acceptance, retention, and application of KSAA. In addition, the growing utilization of modeling and simulation tools as mechanisms to augment the design, delivery, and dissemination of educational interventions and enhance realism in experiential learning supports this goal. The literature also discussed blended learning – the combination of traditional training methods and modalities (eg, information-based didactic delivery and learning) and experiential learning.

The theme of experiential learning is interwoven with numerous studies that highlight interactivity, case studies, hands-on decision-making, and teamwork as principal methods of training. Articles comprising this key theme focused on how to develop decision-making skills (n = 170) Reference Abed, Hongxia and Hongyan2–Reference Zografos, Douligeris and Tsoumpas171 under either realistic or simulated (n = 159) Reference Adini, Goldberg and Cohen6–Reference Akbar, Aliabadi and Patel8,Reference Araz17–Reference Ayala20,Reference Barrett, Eubank and Smith22–Reference Berariu, Fikar and Gronalt24,Reference Bruni-Bossio and Willness30,Reference Chen and Pena-Mora37,Reference Chen, Wang and Zomaya38,Reference Chen, Kuo and Lai40–Reference Chou, Tsai and Chen42,Reference Das, Savachkin and Zhu52,Reference Daughton, Generous and Priedhorsky53,Reference Dorn56,Reference Drury, Klein and Pfaff59–Reference Ergu, Zhang and Guo61,Reference Goolsby, Vest and Goodwin70,Reference Han, Kim and Suh72,Reference Hasan, Mesa-Arango and Ukkusuri73,Reference Holm, Moradi and Svan76–Reference Hunsaker79,Reference Izida, Tedrus and Marietto83–Reference Jining, Lizhe and Lajiao88,Reference Kanno, Shimizu and Furuta91,Reference Kirk, Fiumefreddo and Reynard97,Reference Lee, Maheshwary and Mason104,Reference McGregor, Kaczmarek and Mosley118,Reference Rice133,Reference Rosenthal and Sheiniuk138,Reference Sharma147,Reference Siegel and Young149,Reference Song, Gong and Li153,Reference Stewart, Williams and Smith-Gratto156,Reference Tang and Wen157,Reference Tena-Chollet, Tixier and Dandrieux159,Reference Warner, Bowers and Swerdlin163,Reference Xu, Nyerges and Nie169,Reference Yu, Wen and Jiang170,172–Reference Zhu, Abraham and Paul281 conditions (eg, exercises, virtual reality [VR] simulations). In accordance with experiential learning, many studies explored, developed, or tested unique training design (n = 124) Reference Araz and Jehn18,Reference Chen, Wang and Zomaya38,Reference Cohen-Hatton and Honey43,Reference Coleman, Ishisoko and Trounce45,Reference Cools and Van Den Broeck47,Reference Dorn56,Reference Ibrahim and Tanglang80,Reference Kaczmarczyk, Davidson and Bryden90,Reference Khorram-Manesh, Berlin and Carlstrom94,Reference Loos and Rogers111,Reference Renger and Granillo132,Reference Rose, Seater and Norige137,Reference Smith151,Reference Stalker, Cullen and Kloesel155,Reference Bernardes, Rebelo and Vilar185,Reference Delaney, Lucero and Maves204,Reference Gagnon, Vough and Nickerson213,Reference Goolsby and Deering217,Reference Janev, Mijovic and Tomasevic221,Reference Ingrassia, Ragazzoni and Carenzo236,Reference Miller, Scott and Issenberg239,Reference Munnell and Todaro246,Reference Olson, Hoeppner and Scaletta249,Reference Paton and Jackson254,Reference Wang, Li and Yuan270,Reference Weinstock, Kappus and Kleinman271,Reference Ablah, Nickels and Hodle282–Reference Yoon, Velasquez and Partridge379 or gaming (n = 20) Reference Adida, DeLaurentis and Lawley5,Reference Crichton and Flin51,Reference Kaczmarczyk, Davidson and Bryden90,Reference Tena-Chollet, Tixier and Dandrieux159,Reference Bharosa, Janssen and Meijer187,Reference Chen, Wu and Wu197,Reference Djordjevich, Xavier and Bernard206,Reference Jarventaus222,Reference Lisk, Kaplancali and Riggio234,Reference Mendonça, Beroggi and van Gent238,Reference Olson, Hoeppner and Scaletta249,Reference Sanjay259,Reference Williams-Bell, Murphy and Kapralos274,Reference Yu and Ganz280,Reference Barnett, Everly and Parker289,Reference Parker, Barnett and Fews341,Reference Crichton, Flin and Rattray380–Reference Rosenbaum, Klopfer and Perry383 while incorporating teamwork (n = 11), Reference Crichton and Flin51,Reference Setliff, Porter and Malison143,Reference Baliga, Rolland and Bright182,Reference Venegas-Borsellino, Dudaie and Lizano268,Reference West, Landry and Graham272,Reference Greci, Ramloll and Hurst308,Reference Hill384–Reference Subramaniam, Ali and Shamsudin388 interactive (n = 11), Reference Loos and Rogers111,Reference Maciejewski, Kim and King-Smith115,Reference Setliff, Porter and Malison143,Reference Chen, Wu and Wu197,Reference Chu, Drogoul and Boucher199,Reference Gemmell, Finlayson and Marston215,Reference Miller, Scott and Issenberg239,Reference Holtzhauer, Nelson and Myers312,Reference Orfaly, Biddinger and Burstein338,Reference Rottman, Shoaf and Dorian389,Reference Waltz, Maniccia and Bryde390 blended learning (n = 7), Reference Adini, Goldberg and Cohen6,Reference Fernandez, Vazquez and Daltuva391–Reference Tretsiakova-McNally, Maranne and Verbecke396 and PBL (n = 7) Reference Stalker, Cullen and Kloesel155,Reference Marshall, Yamada and Inada328,Reference Streichert, O’Carroll and Gordon362,Reference Bhogal, Murray and McLeod397–Reference Wei, Wu and Feng400 formats (Table 4).

Table 4. Frequency of keywords associated with each theme

Representative of this theme, Cesta et al. (2011) outline the necessity of fostering creative decision-making by developing engaging and realistic scenarios in support of experiential learning. Reference Cesta, Cortellessa and De Benedictis32 The resulting system developed supports trainers in incorporating exercises into 4- to 5-hour training sessions with exercises for classes of decision makers to practice in joint decision-making under stress. Yang-Im et al. (2009) point out the advantages of the experiential nature of large-scale exercises, including building trust among individuals and their respective organizations. Reference Yang-Im, Trim and Upton277 In addition, Setliff et al. (2003) describe several independent workforce initiatives (ie, the Sustainable Management Development Program, the Management Academy for Public Health, and the Leadership and Management Institute) at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) aimed primarily at strengthening management and leadership capacity through interactive adult learning, with emphasis on interaction, decision-making, reflection, and application. Reference Setliff, Porter and Malison143 Furthermore, Stern (2014) speaks to the desire for well-designed training and exercises tailored to the needs of strategic leaders in order to develop and maintain critical problem-solving and communication skill sets. Reference Stern401 Last, Wilson et al. (2014) describe the historical evolution of emergency training and elaborated on the advantages of a blended learning format of a 3-day course in the United Kingdom; the course used an immersive learning environment (ie, “Hydra” Simulated Operations) to provide incident command training for civil emergencies. Reference Wilson and Gosiewska375

Theme 2: Technological Adaptation – Describing the Evolution from Human-Driven Leadership to Technology-Assisted Leadership

Technological adaptation has become increasingly common among decision makers. In particular, there has been a distinct evolution from exclusively human-driven leadership and decision-making to increasing the incorporation of technology-based aids and tools. In contrast to the previous theme in which modeling and simulation tools support and enhance the experiential learning environment, this theme describes technological solutions in broader terms as capabilities that support decision-making among emergency response leaders and the design, delivery, and dissemination of educational interventions.

Importantly, while existing literature demonstrated increasing utilization and growing acceptance of technological tools, this review notes the lack of definitive evidence on the accessibility, ease of use, and cost-effectiveness that can be generalized to recommend specific technological solutions for training, exercises, and decision-making during emergency response. In other words, evidence described in existing literature is primarily subjective based on user experiences, and the positive impacts of technological tools are still emerging. This observation underscores the need – also noted subsequently in Theme 5 – to develop methodologies and metrics that can be applied consistently across diverse learning environments to evaluate the effectiveness of educational interventions, including the impact of technological tools.

Descriptive studies, particularly from the engineering and computer science literature, highlighted technology in development and the utility of technological decision-support tools. Of note, both technology-aided decision support (n = 116)Reference Abed, Hongxia and Hongyan2,Reference Adla and Zarate7–Reference Duzgun, Yucemen and Kalaycioglu12,Reference Araz17,Reference Bertsch, Geldermann and Rentz26,Reference Bravata, McDonald and Szeto29,Reference Chang, Tseng and Chen34,Reference Chen and Pena-Mora37,Reference Chen, Lu and Pang39,Reference Chou, Tsai and Chen42,Reference Dillon, Liebe and Bestafka55,Reference Drake, Favreau and Mangum57,Reference Drury, Klein and Pfaff59,Reference Eaglin, Wang and Ribarsky60,Reference Esmaelian, Tavana and Arteaga62,Reference Gaynor, Seltzer and Moulton66,Reference Good, Winkel and VonNiederhausern69,Reference Jehn and Lant84,Reference Jeng-Chung Chen, Ni-Bin and Yang-Chi Chang85,Reference Kim, Sharman and Cook-Cottone95,Reference Kirk, Fiumefreddo and Reynard97,Reference Lee, Maheshwary and Mason104,Reference Li, Wang and Qi105,Reference Liapis, Kostaridis and Ramfos107,Reference Liu, Guo and Jiang110,Reference Lowe, Coelho and Barcellos113,Reference Neville, O’Riordan and Pope122,Reference Park, Nam and Jang124,Reference Parks, Walker and Pettey125,Reference Perry, Wiggins and Childs128,Reference Perry, Wiggins and Childs129,Reference Rojas-Palma, Madsen and Gering135,Reference Salt and Dunsmore139–Reference Schneider, Romanowski and Stein141,Reference Shahparvari, Chhetri and Abbasi144,Reference Taniguchi, Ferreira and Nicholson158,Reference Thompson, Altay and Green160,Reference Wilkins, Nsubuga and Mendlein165,Reference Wilson, Polyak and Blake166,Reference Yu, Wen and Jiang170,Reference Bowles and Aboelata191,Reference Campbell, Mete and Furness194,Reference Carr, Walsh and Williams195,Reference Chu, Drogoul and Boucher199,Reference Dvorzhak, Puras and Montero207,Reference Hale218,Reference Lee, Maheshwary and Mason228,Reference Little, Loggins and Wallace235,Reference Mendonça, Beroggi and van Gent238,Reference Nasstrom, Sugiyama and Baskett247,Reference Ozdamar253,Reference Zhu, Abraham and Paul281,Reference Yoon, Velasquez and Partridge379,Reference Cianciolo, Grover and Bickley398,Reference Abramovich, Toner and Matheny402–Reference Zhang, Zhou and Liu458 and modeling (n = 72)Reference Araz17,Reference Barrett, Eubank and Smith22,Reference Beloglazov, Almashor and Abebe23,Reference Bertsch and Geldermann25–Reference Bingzhen and Weimin27,Reference Coles, Zhang and Zhuang46,Reference Coombs48,Reference Daughton, Generous and Priedhorsky53,Reference De Groeve, Annunziato and Kugler54,Reference Drake, Favreau and Mangum57,Reference Esmaelian, Tavana and Arteaga62,Reference Goolsby, Vest and Goodwin70,Reference Han, Kim and Suh72,Reference Hasan, Mesa-Arango and Ukkusuri73,Reference Holm, Moradi and Svan76,Reference Ji-Quan, Jing-Dan and Xing-Peng86,Reference Jining, Lizhe and Lajiao88,Reference Kanno, Shimizu and Furuta91,Reference Mackinnon, Bacon and Cortellessa116,Reference McGregor, Kaczmarek and Mosley118,Reference Monu and Woo120,Reference Pauwels, Van de Walle and Hardeman126,Reference Rice133,Reference Santella, Steinberg and Parks140,Reference Shan, Wang and Li145,Reference Sharma147,Reference Stewart, Williams and Smith-Gratto156,Reference Warner, Bowers and Swerdlin163,Reference Xu, Nyerges and Nie169,Reference Chaturvedi, Armstrong and Chaturvedi196,Reference Dvorzhak, Puras and Montero207–Reference Ferreira, Vicente and Raimundo Mendes da Silva209,Reference Gan, Richter and Shi214,Reference Hale218–Reference Hoard, Homer and Manley220,Reference Jarventaus222,Reference Lee, Maheshwary and Mason228,Reference Moghadas, Pizzi and Wu242,Reference Nasstrom, Sugiyama and Baskett247,Reference Sanjay259,Reference Sisiopiku261,Reference Baccam and Boechler288,Reference Anaya-Arenas, Ruiz and Renaud406,Reference Angalakudati, Calzada and Farias408,Reference Benamrane and Boustras411,Reference Bryson, Millar and Joseph414,Reference Camp, LeBoeuf and Abkowitz415,Reference Chalfant and Comfort418,Reference Han, Zhang and Dong428,Reference Heslop, Chughtai and Bui431,Reference Shahparvari, Chhetri and Abareshi453,Reference Zhang, Zhou and Liu458–Reference Aebersold, Tschannen and Bathish475 represent a large proportion of technological advancements. Although many articles discuss simulation with reference to exercises, simulation was less commonly associated with technology-aided training. Furthermore, the definition of simulation in literature is not precise; it is often used interchangeably with – and in differing contexts ranging from – computer-based simulation to multiagency exercises. For this reason, simulation is not exclusively tied to technology. Nonetheless, a subset of articles shows clear linkages to technology, including those describing virtual reality (VR; n = 10) Reference Lemheney229,Reference Ingrassia, Ragazzoni and Carenzo236,Reference Munnell and Todaro246,Reference Sharma, Jerripothula and Mackey260,Reference Yellowlees, Cook and Marks278,Reference Andreatta, Maslowski and Petty287,Reference Greci, Ramloll and Hurst307,Reference Hsu, Li and Bayram315,Reference Kilmon, Brown and Ghosh319,Reference Aebersold, Tschannen and Bathish475 and augmented reality (n = 3) Reference Gan, Richter and Shi214,Reference Rosenbaum, Klopfer and Perry383,Reference Dong, Schafer and Ganz476 to support training design, delivery, and dissemination that make use of online (n = 32), Reference Acquaviva, Posey and Dawson4,15,Reference De Groeve, Annunziato and Kugler54,Reference Jeng-Chung Chen, Ni-Bin and Yang-Chi Chang85,Reference Renger and Granillo132,Reference Atack, Bull and Dryden181,Reference Chu, Drogoul and Boucher199,Reference Jarventaus222,Reference Lisk, Kaplancali and Riggio234,Reference Nambisan333,Reference Weiner372,Reference Westli, Johnsen and Eid374,Reference Waltz, Maniccia and Bryde390,Reference Ehrhardt, Brown and French424,Reference Huang, Chan and Hyder433,Reference Baldwin, LaMantia and Proziack477–Reference Xu, Jiang and Qin493 distance learning (n = 14), Reference Hassad74,Reference Ibrahim and Tanglang80,Reference Von Lubitz, Carrasco and Fausone269,Reference Macario, Benton and Yuen394,Reference Jenvald, Morin and Kincaid466,Reference Frahm, Gardner and Brown481,Reference Horney, Sollecito and Alexander484,Reference Kenefick, Ravid and MacVarish486,Reference Shield, Wiesner and Curran490,Reference Xu, Jiang and Qin493–Reference Straus, Shanley and Yeung497 and just-in-time (n = 8) Reference Koerner, Coleman and Murrain-Hill99,Reference Von Lubitz, Carrasco and Fausone269,Reference Li, Li and Chen324,Reference Shahparvari, Chhetri and Abareshi453,Reference Baldwin, LaMantia and Proziack477,Reference Blando, Robertson and Bresnitz478,Reference Hogue, Bounds and Barbye498,Reference Sanger and Luebbert499 methods (see Table 4).

The following representative articles further illustrate the subthemes of technological adaptation. Hsu et al. (2013) present a review of advents in technology-based approaches for disaster response training using VR environments, including the rationale and advantages of VR-based training. Reference Hsu, Li and Bayram315 Little et al. (2015) describe preliminary research to determine how emergency managers and other officials use decision support systems for natural disaster planning, response, and recovery. Reference Little, Manzanares and Wallace445 This study aims to identify specific desirable system attributes and suggest areas for improvement. In addition, Santella et al. (2009) describe the utility of a modeling tool to aid decision-making for critical infrastructure protection. Reference Santella, Steinberg and Parks140 This study presents capabilities of the Critical Infrastructure Protection Decision Support System (CIPDSS) model from the US Department of Homeland Security and describes the developmental challenges of such a model. Finally, Tena-Chollet et al. (2016) discuss the development of technology-based learning approaches and teaching strategies and describe a novel learning system that uses a semi-virtual training environment for strategic crisis management and decision-making. Reference Tena-Chollet, Tixier and Dandrieux159

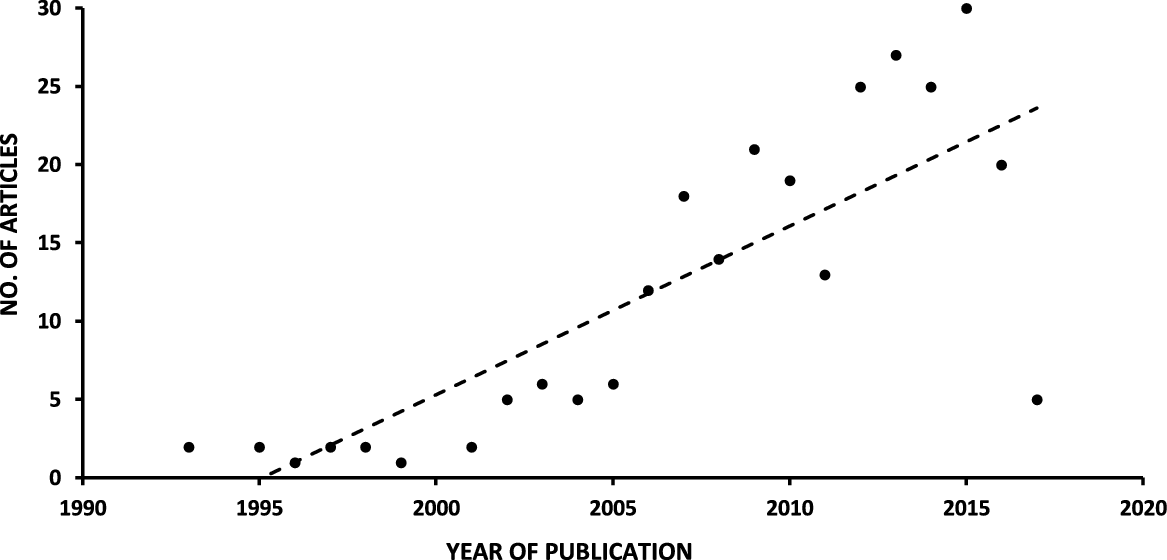

Existing literature also revealed a noteworthy trend in technology-aided decision support. Over time, an increasing number of articles highlighted the utilization of modeling, simulation, and other technological tools to support decision-making. Specifically, from 1993 to 2000, 10 articles pertaining to this topic appeared in the literature; from 2001 to 2010, 108 articles were published; and from 2011 to 2017, 145 were published on this topic (Figure 2). Reference Abu-Elkheir, Hassanein and Oteafy3,Reference Acquaviva, Posey and Dawson4,Reference Akbar, Aliabadi and Patel8–Reference Akgun, Kandakoglu and Ozok10,Reference Duzgun, Yucemen and Kalaycioglu12,Reference Albano, Sole and Adamowski13,15–Reference Araz, Jehn and Lant19,Reference Barrett, Eubank and Smith22,Reference Beloglazov, Almashor and Abebe23,Reference Bertsch and Geldermann25,Reference Bertsch, Geldermann and Rentz26,Reference Bruni-Bossio and Willness30,Reference Chang, Tseng and Chen34,Reference Chen and Huang36,Reference Chen and Pena-Mora37,Reference Chen, Kuo and Lai40,Reference Cheng41,Reference Cohen-Hatton and Honey43,Reference Das, Savachkin and Zhu52,Reference Daughton, Generous and Priedhorsky53,Reference Dorn56,Reference Drake, Favreau and Mangum57,Reference Drury, Klein and Pfaff59–Reference Fuse, Okumura and Hagiwara64,Reference Gaynor, Seltzer and Moulton66,Reference Good, Winkel and VonNiederhausern69,Reference Hadley, Pittinsky and Sommer71–Reference Hasan, Mesa-Arango and Ukkusuri73,Reference Holm, Moradi and Svan76–Reference Hunsaker79,Reference Ireson and Burel82–Reference Jehn and Lant84,Reference Jia and Xie87,Reference Jining, Lizhe and Lajiao88,Reference Kanno, Shimizu and Furuta91,Reference Kirk, Fiumefreddo and Reynard97,Reference Liu, Guo and Jiang110,Reference Lowe, Coelho and Barcellos113,Reference Maciejewski, Kim and King-Smith115,Reference Mansourian, Rajabifard and Zoej117,Reference McGregor, Kaczmarek and Mosley118,Reference Monu and Woo120,Reference Neville, O’Riordan and Pope122,Reference Park, Nam and Jang124,Reference Parks, Walker and Pettey125,Reference Peng, Zhang and Tang127–Reference Perry, Wiggins and Childs129,Reference Rice133,Reference Rojas-Palma, Madsen and Gering135,Reference Rosenthal and Sheiniuk138–Reference Santella, Steinberg and Parks140,Reference Shan, Wang and Li145–Reference Sharma147,Reference Siegel and Young149,Reference Song, Gong and Li153,Reference Stewart, Williams and Smith-Gratto156–Reference Tsai and Yau161,Reference Warner, Bowers and Swerdlin163,Reference Wilson, Polyak and Blake166,Reference Yu, Wen and Jiang170,Reference Asproth and Amcoff Nyström180–Reference Baliga, Rolland and Bright182,Reference Bernardes, Rebelo and Vilar185–Reference Bharosa, Janssen and Meijer187,Reference Boet, Bould and Fung189–Reference Cranmer and Johnson201,Reference Davis, Proctor and Shageer203,Reference Delaney, Lucero and Maves204,Reference Djordjevich, Xavier and Bernard206,Reference Dvorzhak, Puras and Montero207,Reference Ferreira, Vicente and Raimundo Mendes da Silva209–Reference Fung, Boet and Qosa212,Reference Gan, Richter and Shi214,Reference Gemmell, Finlayson and Marston215,Reference Hale218,Reference Hassanzadeh, Nedović- Budić and Alavi Razavi219,Reference Janev, Mijovic and Tomasevic221–Reference Lemheney229,Reference Lerner and Meshenberg231–Reference Lewis, Strachan and Smith233,Reference Little, Loggins and Wallace235,Reference Ma, Mao and Zhou237–Reference Olson, Scheller and Wey251,Reference Ozdamar253,Reference Paton and Jackson254,Reference Rubin257–Reference Stein, Rudge and Coker264,Reference Van Niekerk, Coetzee and Botha267–Reference Von Lubitz, Carrasco and Fausone269,Reference West, Landry and Graham272–Reference Yamashita, Soeda and Noda276,Reference Yellowlees, Cook and Marks278,Reference Youngblood, Harter and Srivastava279,Reference Zhu, Abraham and Paul281,Reference Andreatta, Maslowski and Petty287,Reference Glow, Colucci and Allington305,Reference Greci, Ramloll and Hurst307,Reference Hsu, Li and Bayram315,Reference Kilmon, Brown and Ghosh319,Reference Pinto and Bozkurt344,Reference Tarek364,Reference Walkner, Fife and Bedet369,Reference Yoon, Velasquez and Partridge379,Reference Haferkamp and Kramer381,Reference Rosenbaum, Klopfer and Perry383,Reference Fernandez, Vazquez and Daltuva391,Reference Rodríguez Montequín, Mesa Fernández and Balsera399,Reference Aleskerov, Say and Toker403,Reference Amailef and Jie404,Reference Anaya-Arenas, Ruiz and Renaud406,Reference Angalakudati, Calzada and Farias408–Reference Camp, LeBoeuf and Abkowitz415,Reference Chalfant and Comfort418,Reference Dalnoki-Veress, McKallagat and Klebesadal419,Reference Dotson, Hudson and Maier423,Reference Farnaghi and Mansourian425,Reference Han, Zhang and Dong428–Reference Jiang, Wang and Lung436,Reference Kim, Maciejewski and Ostmo438,Reference Kolios, Milis and Panayiotou439,Reference Levy and Taji442–Reference Little, Manzanares and Wallace445,Reference Meris and Barbera447–Reference Shahparvari, Chhetri and Abareshi453,Reference Tian, Zhou and Yao455–Reference Dilmaghani, Rao and Member461,Reference Hu, Liu and Hua464,Reference Jenvald, Morin and Kincaid466,Reference Li, Deng and Liu469,Reference Liu, Jiang and Member470,Reference Rosenfeld, Fox and Kerr472,Reference Aebersold, Tschannen and Bathish475,Reference Baldwin, LaMantia and Proziack477,Reference Chiu, Polivka and Stanley479,Reference Horney, MacDonald and Rothney483,Reference Horney, Sollecito and Alexander484,Reference Peddecord, Holsclaw and Jacobson488,Reference Wang, Gonzales and Milewski491,Reference Alexander, Horney and Markiewicz494,Reference Metzko, Reeding and Fletcher496,Reference Ablah, Hawley and Konda500–Reference Yamashita, Soeda and Noda532

Figure 2. Chronological trend of articles pertaining to technology-aided decision-making or decision support through modeling, simulation, or other tools.

Theme 3: Educational Continuum – Incorporating Leadership Training in Public Health Academic and Professional Development Curricula

The educational continuum encompasses learning beginning with degree-granting programs and professional schools and progressing through postgraduate and workforce development (ie, on-the-job) training programs. Presently, public health leadership training primarily focuses on postgraduate or job-related training and varies widely in content and delivery. Integrating leadership training throughout the educational continuum will provide opportunities for developing future leaders systematically. As such, there is growing recognition that leadership training merits equal emphasis as traditionally accepted training priorities (eg, technical skills). The literature underscores the importance of the following:

-

Curriculum development and training design that promote relevant learning and knowledge acceptance

-

Multidisciplinary training that fosters an understanding of the interdependencies of decision-making across disciplines

-

Training that emphasizes the standardization of core competencies in workforce development through existing frameworks or guidance

-

Evolving educational priorities that address concerns and issues in the present academic and professional development environment

Educational elements for structuring leadership training as part of a systematic pipeline included training design (n = 101), Reference Araz and Jehn18,Reference Chen, Wang and Zomaya38,Reference Cohen-Hatton and Honey43,Reference Coleman, Ishisoko and Trounce45,Reference Ibrahim and Tanglang80,Reference Kaczmarczyk, Davidson and Bryden90,Reference Khorram-Manesh, Berlin and Carlstrom94,Reference Renger and Granillo132,Reference Rose, Seater and Norige137,Reference Stalker, Cullen and Kloesel155,Reference Bernardes, Rebelo and Vilar185,Reference Delaney, Lucero and Maves204,Reference Goolsby and Deering217,Reference Ingrassia, Ragazzoni and Carenzo236,Reference Miller, Scott and Issenberg239,Reference Wang, Li and Yuan270,Reference Weinstock, Kappus and Kleinman271,Reference Ablah, Tinius and Horn283,Reference Aitken, Leggat and Robertson284,Reference Alexander286–Reference Bochenek, Grant and Schwartz292,Reference Brower, Choi and Jeong295–Reference Dutton, Frost and Worline302,Reference Evans, Anderson and Shahpar304–Reference Holtzhauer, Nelson and Myers312,Reference Hsu, Dunn and Juo314–Reference Jackson, Buehler and Cole316,Reference Khoshnevis, Panahi and Ghanei318–Reference Langan, Lavin and Wolgast321,Reference Levy, Aghababian and Hirsch323,Reference Markenson, Reilly and DiMaggio327,Reference Miller, Umble and Frederick331–Reference Negandhi, Negandhi and Tiwari335,Reference Orach, Mayega and Woboya337,Reference Orfaly, Biddinger and Burstein338,Reference Owen, Scott and Adams340,Reference Parker, Barnett and Fews341,Reference Piltch-Loeb, Nelson and Kraemer343–Reference Rebmann, English and Carrico350,Reference Reutter, Schutzer and Craft352–Reference Savoia, Biddinger and Fox354,Reference Scott, Swartzentruber and Davis356–Reference Smith and Kuldau359,Reference Stein361–Reference Subbarao, Lyznicki and Hsu363,Reference Thorne, Oliver and Al-Ibrahim365–Reference Westli, Johnsen and Eid374,Reference Winskog, Tonkin and Byard376,Reference Wright, Thomas and Durham377,Reference Ablah, Tinius and Konda533–Reference Sandstrom, Eriksson and Norlander542 frameworks (n = 76) Reference Adida, DeLaurentis and Lawley5,Reference Arain16,Reference Araz17,Reference Bravata, McDonald and Szeto29,Reference Chen, Wang and Zomaya38,Reference Das, Savachkin and Zhu52,Reference Fruhling and Petter63,Reference Gambhir, Bozio and O’Hagan65,Reference Hassad74,Reference Huang, Wang and Jiang77,Reference Kayman and Logar92,Reference Knebel, Sharpe and Danis98,Reference Liu, Guo and Jiang110,Reference Lowe, Coelho and Barcellos113,Reference Mitton and Patten119,Reference Song, Gong and Li153,Reference Tena-Chollet, Tixier and Dandrieux159,Reference Worm168,Reference Zografos, Douligeris and Tsoumpas171,Reference Antoniou, Panayides and Pattichis177,Reference Asllani, Dileepan and Ettkin179,Reference Chen, Wu and Wu197,Reference Corley and Mikler200,Reference Hoard, Homer and Manley220,Reference Bochenek, Grant and Schwartz292,Reference Carone and Iorio296,Reference Decker and Holtermann299,Reference Ned-Sykes, Johnson and Ridderhof334,Reference Seynaeve, Archer and Fisher357,Reference Subbarao, Lyznicki and Hsu363,Reference Ortiz Figueroa, Moftakhar and Dobbins387,Reference Subramaniam, Ali and Shamsudin388,Reference Amailef and Jie404,Reference Camp, LeBoeuf and Abkowitz415,Reference Jiang, Wang and Lung436,Reference Levy, Hartmann and Li443,Reference Jenvald, Morin and Kincaid466,Reference Lichtveld, Cioffi and Baker521,Reference Tsai, Lee and Lu528,Reference Olson, Hoeppner and Larson538,Reference Ablah, Tinius and Konda543–Reference Wright, Rowitz and Merkle578 incorporating overarching principles or paradigms, competencies (n = 71), Reference Hunsaker79,Reference Khorram-Manesh, Berlin and Carlstrom94,Reference Cranmer and Johnson201,Reference Olson, Scheller and Wey251,Reference Osen, Patry and Casement252,Reference West, Landry and Graham272,Reference Williams-Bell, Murphy and Kapralos274,Reference Ablah, Tinius and Horn283,Reference Barnett, Everly and Parker289,Reference Evans, Anderson and Shahpar304,Reference Hites, Lafreniere and Wingate311,Reference Holtzhauer, Nelson and Myers312,Reference Hsu, Dunn and Juo314,Reference Negandhi, Negandhi and Tiwari335,Reference Owen, Scott and Adams340,Reference Potter, Pistella and Fertman348,Reference Sarpy, Chauvin and Hites353,Reference Scott, Swartzentruber and Davis356,Reference Traicoff, Walke and Jones366,Reference Walsh, Altman and King370,Reference Weiner372,Reference Werner, Wright and Thomas373,Reference Rottman, Shoaf and Dorian389,Reference Chiu, Polivka and Stanley479,Reference Hites, Granillo and Garrison482,Reference Horney, MacDonald and Rothney483,Reference Kenefick, Ravid and MacVarish486,Reference Sarpy, Warren and Kaplan489,Reference Lichtveld, Cioffi and Baker521,Reference Wang, Luangkesorn and Shuman530,Reference Olson, Hoeppner and Larson538,Reference Gebbie and Merrill554,Reference Lichtveld, Hodge and Gebbie560,Reference Richmond, Sobelson and Cioffi567,Reference Shuck and Herd570,Reference VanDevanter, Leviss and Abramson574,Reference Weiner and Trangenstein576,Reference Wright, Rowitz and Merkle578–Reference Zhuravsky611 KSAA (n = 55), Reference Khorram-Manesh, Ashkenazi and Djalali93,Reference Renger and Granillo132,Reference Djordjevich, Xavier and Bernard206,Reference Fung, Boet and Bould211,Reference Lewis, Strachan and Smith233,Reference Miller, Scott and Issenberg239,Reference Nicely and Farra248,Reference Paton and Jackson254,Reference Wong, Ng and Chen275,Reference Yamashita, Soeda and Noda276,Reference Alam, Tesfamariam and Alam285,Reference Blum, Raemer and Carroll291,Reference Carone and Iorio296,Reference Dutton, Frost and Worline302,Reference Miller, Umble and Frederick331,Reference Negandhi, Negandhi and Tiwari335,Reference Orfaly, Biddinger and Burstein338,Reference Stein361,Reference Haferkamp and Kramer381,Reference Jankouskas, Haidet and Hupcey385–Reference Ortiz Figueroa, Moftakhar and Dobbins387,Reference Baldwin, LaMantia and Proziack477,Reference Blando, Robertson and Bresnitz478,Reference Frahm, Gardner and Brown481,Reference Horney, MacDonald and Rothney483,Reference Barnett, Thompson and Semon549,Reference Olson565,Reference McCabe, Everly and Brown592,Reference Peller, Schwartz and Kitto596,Reference Reischl and Buss599,Reference Abatemarco, Beckley and Borjan612–Reference Ziesmann, Widder and Park635 and curriculum design and development (n = 38). Reference Adini, Goldberg and Cohen6,Reference Hassad74,Reference Khorram-Manesh, Ashkenazi and Djalali93,Reference Goolsby and Deering217,Reference Osen, Patry and Casement252,Reference Wang, Li and Yuan270,Reference Alexander286,Reference Greci, Ramloll and Hurst308,Reference Holtzhauer, Nelson and Myers312,Reference Walsh, Altman and King370,Reference Mantha, Coggins and Mahadevan386,Reference Ortiz Figueroa, Moftakhar and Dobbins387,Reference Rottman, Shoaf and Dorian389,Reference Fernandez, Vazquez and Daltuva391,Reference Lichtveld, Cioffi and Baker521,Reference Baka, Fusco and Puro548,Reference Barnett, Thompson and Semon549,Reference Kohn, Barnett and Galastri558,Reference Tower, Altman and Strauss-Riggs573,Reference Hoeppner, Olson and Larson587,Reference Ingrassia, Foletti and Djalali588,Reference Reed, Bullis and Collins598,Reference Ziesmann, Widder and Park635–Reference Paquin, Bank and Nguyen650 In this context, multiple studies also addressed multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary collaboration (n = 65), Reference Ireson and Burel82,Reference Kim, Oh and Jo96,Reference Kohn, Semon and Hedlin100,Reference Mansourian, Rajabifard and Zoej117,Reference Sommer and Nja152,Reference Wilson, Wood and Kong167,Reference Atack, Bull and Dryden181,Reference Fung, Boet and Bould211,Reference Miller, Scott and Issenberg239,Reference Moghadas, Pizzi and Wu242,Reference Nicely and Farra248,Reference Rui, Bin and Fengru258,Reference West, Landry and Graham272,Reference Yang-Im, Trim and Upton277,Reference Youngblood, Harter and Srivastava279,Reference Marshall, Yamada and Inada328,Reference Negandhi, Negandhi and Tiwari335,Reference Sarpy, Chauvin and Hites353,Reference Seynaeve, Archer and Fisher357,Reference Streichert, O’Carroll and Gordon362,Reference Bicocchi, Ross and Ulieru459,Reference Demers, Mamary and Ebin480–Reference Hites, Granillo and Garrison482,Reference Hoying, Farra and Mainous485,Reference Chang and Li507,Reference Chronaki, Kontoyiannis and Charalambous508,Reference Diez, Tena and Romero-Gomez513,Reference Dorn, Savoia and Testa514,Reference Lichtveld, Cioffi and Baker521,Reference Archer and Seynaeve546,Reference Brooks, Bodeau and Fedorowicz551,Reference Abraham, Walls and Fischer579,Reference Ingrassia, Foletti and Djalali588,Reference Quiram, Carpender and Pennel597,Reference Ablah, Molgaard and Fredrickson613,Reference Farra, Smith and Bashaw622,Reference McCabe, Semon and Lating628,Reference Ziesmann, Widder and Park635,Reference Bitto636,Reference Paquin, Bank and Nguyen650–Reference Wilson674 academia (n = 44), Reference Acquaviva, Posey and Dawson4,Reference Johansson and Harenstam89,Reference Kohn, Semon and Hedlin100,Reference Salt and Dunsmore139,Reference Setliff, Porter and Malison143,Reference Djordjevich, Xavier and Bernard206,Reference Goolsby and Deering217,Reference Moghadas, Pizzi and Wu242,Reference Dembek, Iton and Hansen300,Reference Dutton, Frost and Worline302,Reference Hall, Ward and Cunningham309,Reference Miller, Umble and Frederick331,Reference Morris, Greenspan and Howell332,Reference Waltz, Maniccia and Bryde390,Reference Han, Zhang and Dong428,Reference Demers, Mamary and Ebin480,Reference Frahm, Gardner and Brown481,Reference Horney, Sollecito and Alexander484,Reference Hoying, Farra and Mainous485,Reference Shield, Wiesner and Curran490,Reference Lichtveld, Cioffi and Baker521,Reference Olson, Hoeppner and Larson538,545,Reference Olson565,Reference Brown, Maryman and Collins581,Reference Calhoun, Rowney and Eng582,Reference Ingrassia, Foletti and Djalali588,Reference Quiram, Carpender and Pennel597,Reference Fernandez, Noble and Jensen623,Reference McCurley-Smith and Lewis644,Reference Orto, Umble and Davis649,Reference Horney and Wilfert662,Reference Pearson, Thompson and Finkbonner665–Reference Umble, Steffen and Porter669,Reference Johnson, Sabol and Baker675–Reference Veenema681 and other partnerships (n = 8) Reference Djordjevich, Xavier and Bernard206,Reference Hoying, Farra and Mainous485,Reference Brown, Maryman and Collins581,Reference McCabe, Semon and Lating628,Reference Sobelson and Young667,Reference Walsh, Craddock and Gulley671,Reference Mitchell, McKinnon and Aitken682,Reference Phillips and Williamson683 (see Table 4).

Existing literature supported the importance of integrating leadership training into the educational continuum. Specifically, Deitchman (2013) proposes a number of attributes for crisis leadership in public health, including competence in public health science; flexibility and decisiveness; ability to maintain situational awareness and provide situational assessment; ability to coordinate diverse participants across multiple disciplines; communication skills; and the ability to inspire trust. Reference Deitchman684 The author notes that, among these attributes, only competence in public health science is currently a goal of public health education. In addition, Gebbie et al. (2013) describe implications of emergency preparedness and response core competencies for managing public health emergencies; and Walsh et al. (2012) discuss core competencies in disaster medicine and public health emergencies that may be adapted to inform the development of formal leadership training in the field. Reference Gebbie, Weist and McElligott624,Reference Walsh, Subbarao and Gebbie685 Finally, Richmond et al. (2014) highlight the work of then CDC-funded Preparedness and Emergency Response Learning Centers (PERLCs) to enhance workforce readiness and competencies through schools of public health accredited by the Council on Education for Public Health. Reference Richmond, Sobelson and Cioffi567 While not specifically focused on leadership development, PERLC learning programs through an integrated national learning network emphasized the importance of linking academia with practice in public health education.

Theme 4: Defining Leadership Holistically – Developing Leaders through Competency and Character

Leadership competencies traditionally define the knowledge, skills, and abilities that an individual needs in order to lead successfully. In the context of developing future leaders, competencies provide the basis of and inform the key needs for leadership training. Articles from this review revealed an emerging perspective that, in addition to technical competencies, the character or soft skills of an individual are critical leadership qualities. In the context of this study, leadership character serves as the attitude component of the KSAA construct and addresses the non-technical, cognitive, behavioral, and/or interpersonal skills of an individual. In other words, how does a leader react, interact, or adapt in an environment through logical reasoning, critical thinking, and decision-making? Several articles suggested that psychometric questionnaires might have value in predicting leadership styles among candidates who may serve in public health emergency response leadership roles. Reference Cooper49,Reference Crichton and Flin50,Reference Kirk, Fiumefreddo and Reynard97,Reference Masotti and Appleget382,Reference Rodríguez Montequín, Mesa Fernández and Balsera399,Reference Tremble and Trueman608,Reference BilÍKovÁ and BartoŠÍKovÁ686–Reference Seiler and Andreas688

Studies under this key theme addressed leadership strategies (n = 42),Reference Boin and Hart28,Reference Cohen-Hatton and Honey43,Reference Ibrahim and Tanglang80,Reference Johansson and Harenstam89,Reference Deverell and Olsson301,Reference Dutton, Frost and Worline302,Reference Westli, Johnsen and Eid374,Reference Keppell, O’Dwyer and Lyon393,Reference Halverson, Mays and Kaluzny495,Reference Aini and Fakhru’l-Razi544,Reference Sjoberg, Wallenius and Larsson571,Reference Wright, Rowitz and Merkle577,Reference Anderson580,Reference Alvinius, Bostrom and Larsson616,Reference Reader, Flin and Cuthbertson631,Reference Brooks, Pinto and Gill653,Reference Bunker, Levine and Woody654,Reference Waugh and Streib673–Reference Johnson, Sabol and Baker675,Reference Sobelson, Young and Marcus679,Reference Deitchman684,Reference Adini, Ohana and Furman689–Reference Stenling and Tafvelin708 guidance (n = 42),Reference Hadley, Pittinsky and Sommer71,Reference Higgins and Freedman75,Reference Kayman and Logar92,Reference Khorram-Manesh, Ashkenazi and Djalali93,Reference Koerner, Coleman and Murrain-Hill99,Reference Mukherjee, Overman and Leviton121,Reference Brandeau, McCoy and Hupert192,Reference Carr, Walsh and Williams195,Reference Owen, Scott and Adams340,Reference Potter, Miner and Barnett347,Reference Reutter, Schutzer and Craft352,Reference Little, Manzanares and Wallace445,Reference Whiteley, Boguski and Erickson492,Reference Alexander, Horney and Markiewicz494,Reference Ablah, Tinius and Konda543,545,Reference Brooks, Bodeau and Fedorowicz551,Reference Mitchell, Doyle and Moran563,Reference Anderson580,Reference Gebbie, Weist and McElligott624,Reference Czabanowska, Rethmeier and Lueddeke639,Reference Kennedy, Carson and Garr642,Reference Getha-Taylor659,Reference Sobelson and Young667,Reference Admi, Eilon and Hyams709–Reference Turnock726 and behavior/behavioral (n = 34)Reference Chen, Wang and Zomaya38,Reference Cohen-Hatton and Honey43,Reference Cools and Van Den Broeck47,Reference Cooper49,Reference Eaglin, Wang and Ribarsky60,Reference Kim, Sharman and Cook-Cottone95,Reference Mackinnon, Bacon and Cortellessa116,Reference Mukherjee, Overman and Leviton121,Reference Wang, Zhang and Wang162,Reference Chen, Wu and Wu197,Reference Cuvelier and Falzon202,Reference Fung, Boet and Bould211,Reference Lewis, Strachan and Smith233,Reference Sharma, Jerripothula and Mackey260,Reference Wong, Ng and Chen275,Reference Yamashita, Soeda and Noda276,Reference Alam, Tesfamariam and Alam285,Reference Carone and Iorio296,Reference Deverell and Olsson301,Reference Hawley, Hawley and St Romain310,Reference Miller, Umble and Frederick331,Reference Hill384,Reference Subramaniam, Ali and Shamsudin388,Reference Kahai, Jestire and Huang437,Reference Yamashita, Soeda and Noda532,Reference Hites, Sass and D’Ambrosio625–Reference McCabe, DiClemente and Links627,Reference Neiworth, Allan and D’Ambrosio629,Reference Reader, Flin and Cuthbertson631,Reference van der Haar, Koeslag-Kreunen and Euwe670,Reference Adini, Ohana and Furman689,Reference Gronvall, Matheny and Smith727,Reference Slattery, Syvertson and Krill728 aspects of leadership as well as critical thinking/judgment (n = 22). Reference Bruni-Bossio and Willness30,Reference Coleman, Ishisoko and Trounce45,Reference Eaglin, Wang and Ribarsky60,Reference Hassad74,Reference Ibrahim and Tanglang80,Reference Kim, Sharman and Cook-Cottone95,Reference Kirk, Fiumefreddo and Reynard97,Reference Kowalski-Trakofler, Vaught and Scharf101,Reference Shen, Huang and Zhao148,Reference Warner, Bowers and Swerdlin163,Reference Decker and Holtermann299,Reference Hsu, Dunn and Juo314,Reference Amailef and Jie404,Reference Kondaveti and Ganz440,Reference Wang, Luangkesorn and Shuman530,Reference Bitto636,Reference BilÍKovÁ and BartoŠÍKovÁ686,Reference Chandra, Williams and Lopez729–Reference Ruter and Vikstrom733 A subset of articles also elaborated on the adaptability/flexibility (n = 17),Reference Ayala20,Reference Baker21,Reference Cooper49,Reference Hunsaker79,Reference Smith, Boulter and Hewlett150,Reference Engel, Locke and Reissman208,Reference Deverell and Olsson301,Reference Jankouskas, Haidet and Hupcey385,Reference Mantha, Coggins and Mahadevan386,Reference Mueller-Hanson, White and Dorsey646,Reference Paquin, Bank and Nguyen650,Reference Goralnick, Halpern and Loo660,Reference Duchesne730,Reference Edwards, Stapley and Akins734–Reference Ratnapalan, Martimianakis and Cohen-Silver737 non-technical skills (n = 13),Reference Cohen-Hatton and Honey43,Reference Crichton and Flin50,Reference Ibrahim and Tanglang80,Reference Kowalski-Trakofler, Vaught and Scharf101,Reference Boet, Everett and Gale190,Reference Lewis, Strachan and Smith233,Reference Brower, Choi and Jeong295,Reference Westli, Johnsen and Eid374,Reference Crichton, Flin and Rattray380,Reference Reed, Bullis and Collins598,Reference Seiler and Andreas688,Reference Cohen-Hatton, Butler and Honey711,Reference Cojocar736 cognitive skills (n = 13),Reference Akgun, Kandakoglu and Ozok10,Reference Ayala20,Reference Cools and Van Den Broeck47,Reference Cooper49,Reference Hunsaker79,Reference Worm168,Reference Gomes, Borges and Huber216,Reference Deverell and Olsson301,Reference Kahai, Jestire and Huang437,Reference Alexander501,Reference von Meding, Wong and Kanjanabootra609,Reference Seiler and Andreas688,Reference Curnow, Mulvaney and Calderon738 emotional intelligence/psychological factors (n = 12),Reference Bruni-Bossio and Willness30,Reference Mackinnon, Bacon and Cortellessa116,Reference Wang, Zhang and Wang162,Reference Djordjevich, Xavier and Bernard206,Reference Kahai, Jestire and Huang437,Reference Schreiber, Koenig and Schultz452,Reference Tian, Zhou and Yao455,Reference McCabe, Everly and Brown592,Reference Alvinius, Bostrom and Larsson616,Reference Birkeland, Nielsen and Knardahl690,Reference Smith707,Reference Hofinger, Zinke and Strohschneider739 teamwork (n = 11), Reference Crichton and Flin51,Reference Setliff, Porter and Malison143,Reference Baliga, Rolland and Bright182,Reference Venegas-Borsellino, Dudaie and Lizano268,Reference West, Landry and Graham272,Reference Greci, Ramloll and Hurst308,Reference Hill384–Reference Subramaniam, Ali and Shamsudin388 and attitude (n = 7)Reference Alam, Tesfamariam and Alam285,Reference Jankouskas, Haidet and Hupcey385,Reference Peddecord, Holsclaw and Jacobson488,Reference Barnett, Balicer and Thompson617,Reference Barnett, Levine and Thompson618,Reference Hites, Sass and D’Ambrosio625,Reference Ziesmann, Widder and Park635 aspects of leadership (see Table 4).

Representative of this key theme, Carone et al. (2013) identify critical factors to support effective crisis management by joining experiences in the field and knowledge of organizational models for crisis management and executive empowerment with coaching and behavioral analysis. Reference Carone and Iorio296 The study examines the relationships among human behavior, emotions, and fears, and how these correlated with decision-making. Hadley et al. (2011) use a novel Crisis Leader Efficacy in Assessing and Deciding (C-LEAD) Scale to measure leadership efficacy in order to assess information and crisis decision-making. Reference Hadley, Pittinsky and Sommer71 In addition, King et al. (2016) seek to elucidate important characteristics of disaster response personnel, including leaders. Reference King, Larkin and Fowler590 The authors suggest that these characteristics are not limited to the knowledge and skills typically included in disaster training and that further research is needed on how best to incorporate these attributes into competency models, processes, and tools for developing an effective disaster response workforce. Finally, Schmalzried et al. (2007) highlight that both experience and continuity of leadership (eg, preservation of institutional knowledge and other non-technical leadership attributes) are critical for managing public health crises. Reference Schmalzried and Fallon740 This study also notes that, even though 43.7% of top executives reported planning to leave their current position within 6 years, succession planning is not a high priority among the majority of local health departments.

Theme 5: Evaluation and Measures of Effectiveness in Training and Exercises – Reflecting on Current Practices and Opportunities for Progress

Generally, existing standards for evaluation of training and exercises demonstrate ample room for growth as few articles pertaining to evaluation and assessing the effectiveness of training and exercises offer specific frameworks or tools. Even fewer evaluation tools are consistent or generalizable. Currently, the majority of evaluation instruments and measures of effectiveness consist of pre- and post-intervention surveys or interviews that document self-reported gains. The limited amount of measurable data presents a challenge to assess or compare the relative effectiveness or quality of educational interventions objectively and meaningfully.

As noted, the preponderance of literature included mostly descriptive and qualitative studies as well as narrative and informational articles with relatively few quantitative or data-driven studies. The literature broadly discussed topics of evaluation (n = 89) Reference Adini, Goldberg and Cohen6,Reference Araz and Jehn18,Reference Bingzhen and Weimin27,Reference Huang, Wang and Jiang77,Reference Renger and Granillo132,Reference Stewart, Williams and Smith-Gratto156,Reference Dieckmann, Molin Friis and Lippert205,Reference Engel, Locke and Reissman208,Reference Lenz and Richter230,Reference Miller, Scott and Issenberg239,Reference Moulsdale, Khetsuriani and Deshevoi244,Reference Olson, Scheller and Larson250,Reference Paton and Jackson254,Reference Andreatta, Maslowski and Petty287,Reference Daniels, Farquhar and Nathanson298,Reference Glow, Colucci and Allington305,Reference Lindsey and Member325,Reference Savoia, Biddinger and Fox354,Reference Wang, Xiang and Xu371,Reference Jankouskas, Haidet and Hupcey385,Reference Rottman, Shoaf and Dorian389,Reference Tian, Zhou and Yao455,Reference Aebersold, Tschannen and Bathish475,Reference Chiu, Polivka and Stanley479,Reference Peddecord, Holsclaw and Jacobson488,Reference Sarpy, Warren and Kaplan489,Reference Ablah, Hawley and Konda500,Reference Dorn, Savoia and Testa514,Reference Paton539,Reference Babaie, Ardalan and Vatandoost547,Reference Kohn, Barnett and Galastri558,Reference Olson565,Reference Savoia, Agboola and Biddinger569,Reference Abraham, Walls and Fischer579,Reference Evans, Hulme and Nugus584,Reference Ingrassia, Foletti and Djalali588,Reference Reischl and Buss599,Reference Saleh, Williams and Balougan601,Reference Abatemarco, Beckley and Borjan612,Reference Ablah, Molgaard and Fredrickson613,Reference Farra, Smith and Bashaw622,Reference Fernandez, Noble and Jensen623,Reference Hites, Sass and D’Ambrosio625,Reference McCabe, Semon and Lating628,Reference Qureshi, Gershon and Merrill630,Reference Wang, Wei and Xiang633,Reference Ziesmann, Widder and Park635,Reference Chen, Yu and Chen637,Reference Cooper638,Reference Allah, Nickels and Hoddle652,Reference Sobelson and Young667,Reference Beerens and Tehler710,Reference Owen, Brooks and Bearman732,Reference Adini and Peleg741–Reference Zukowski776 and effectiveness (n = 59), Reference Chou, Tsai and Chen42,Reference Hunsaker79,Reference Renger and Granillo132,Reference Rose, Seater and Norige137,Reference Smith, Boulter and Hewlett150,Reference Smith151,Reference Stewart, Williams and Smith-Gratto156,Reference Bernardes, Rebelo and Vilar185,Reference Beroggi, Waisel and Wallace186,Reference Boet, Bould and Fung189,Reference Boet, Everett and Gale190,Reference Burden, Pukenas and Deal193,Reference Fung, Boet and Bould211,Reference Kincaid, Donovan and Pettitt224,Reference Lenz and Richter230,Reference Lerner and Meshenberg231,Reference Ma, Mao and Zhou237,Reference Olson, Scheller and Larson250,Reference West, Woodson and Benedek273,Reference Wong, Ng and Chen275,Reference Yang-Im, Trim and Upton277,Reference Aitken, Leggat and Robertson284,Reference Bluestone, Johnson and Fullerton290,Reference Brower, Choi and Jeong295,Reference Nambisan333,Reference Reutter, Schutzer and Craft352,Reference Thorne, Oliver and Al-Ibrahim365,Reference Jankouskas, Haidet and Hupcey385,Reference Rottman, Shoaf and Dorian389,Reference Hadziomerovic, Vollick and Budgell392,Reference Tian, Zhou and Yao455,Reference Bicocchi, Ross and Ulieru459,Reference Sarpy, Warren and Kaplan489,Reference Wee, Chong and Lim531,Reference Paton539,Reference Olson565,Reference Brown, Maryman and Collins581,Reference Reischl and Buss599,Reference Silenas, Akins and Parrish603,Reference Ablah, Molgaard and Fredrickson613,Reference Beaton and Johnson620,Reference Fernandez, Noble and Jensen623,Reference Wang, Wei and Xiang633,Reference Chen, Yu and Chen637,Reference Orto, Umble and Davis649,Reference Errett, Frattaroli and Barnett658,Reference McDonald701,Reference Ford and Schmidt715,Reference Owen, Brooks and Bearman732,Reference Dausey, Buehler and Lurie749,Reference Klima, Seiler and Peterson761,Reference Savoia, Preston and Biddinger772,Reference Baekkeskov and Rubin777–Reference Wang, Wei and Xiang783 with respect to educational interventions. Despite this, very few studies included quantitative assessments. Most studies addressed evaluation and effectiveness with respect to pre- and post-intervention (n = 22) Reference Atack, Bull and Dryden181,Reference Andreatta, Maslowski and Petty287,Reference Glow, Colucci and Allington305,Reference Chiu, Polivka and Stanley479,Reference Peddecord, Holsclaw and Jacobson488,Reference Ablah, Hawley and Konda500,Reference Kohn, Barnett and Galastri558,Reference Olson565,Reference Reischl and Buss599,Reference Saleh, Williams and Balougan601,Reference Abatemarco, Beckley and Borjan612,Reference Ablah, Molgaard and Fredrickson613,Reference Farra, Smith and Bashaw622,Reference Fernandez, Noble and Jensen623,Reference McCabe, Semon and Lating628,Reference Qureshi, Gershon and Merrill630,Reference Wang, Wei and Xiang633,Reference Ziesmann, Widder and Park635,Reference Allah, Nickels and Hoddle652,Reference Hope, Massey and Osbourn757,Reference Rask, Gitomer and Spell768,Reference Welling, Perez and van Harten784 and self-reported gains (n = 18). Reference Dreisinger, Leet and Baker58,Reference Miller, Scott and Issenberg239,Reference Daniels, Farquhar and Nathanson298,Reference Thorne, Oliver and Al-Ibrahim365,Reference Mantha, Coggins and Mahadevan386,Reference Demers, Mamary and Ebin480,Reference Frahm, Gardner and Brown481,Reference Peddecord, Holsclaw and Jacobson488,Reference Ablah, Hawley and Konda500,Reference Murray, Henry and Jackson523,Reference Wee, Chong and Lim531,Reference Ablah, Wetta-Hall and Molgaard614,Reference Fernandez, Noble and Jensen623,Reference Allah, Nickels and Hoddle652,Reference Sobelson, Young and Marcus679,Reference Umble, Baker and Woltring680,Reference Rask, Gitomer and Spell768,Reference D’Ambrosio, Huang and Sheng785 Few studies addressed the topic of cost-effectiveness (n = 13) Reference Araz and Jehn18,Reference Asllani, Dileepan and Ettkin179,Reference Boet, Everett and Gale190,Reference Ma, Mao and Zhou237,Reference Sanjay259,Reference Weinstock, Kappus and Kleinman271,Reference Williams-Bell, Murphy and Kapralos274,Reference Waltz, Maniccia and Bryde390,Reference Demers, Mamary and Ebin480,Reference Xu, Jiang and Qin493,Reference Allah, Nickels and Hoddle652,Reference Cross, Cerulli and Richards786,Reference Kyriacou, Dobrez and Parada787 (see Table 4).

A number of representative articles supported these observations. In an exploratory study on disaster exercise evaluation, Beerens et al. (2016) indicate a general lack of academic interest for standardized evaluation; the study pointed out that, while exercises take place routinely and are often used for research purposes, their evaluations are seldom the focus of attention. Reference Beerens and Tehler710 As an extension, Gebbie et al. (2006) emphasize that consensus-based and public health-specific planning and assessment criteria are necessary to facilitate measurable improvements. Reference Gebbie, Valas and Merrill752

While scant, literature pertaining to evaluation and measures of effectiveness in training and exercises includes a small selection of notable articles that suggest steps for improvement. For example, Biddinger et al. (2010) describe an evaluation of 38 public health emergency preparedness exercises employing realistic scenarios and reliable and accurate outcome measures. Reference Biddinger, Savoia and Massin-Short778 This study notes a demonstrated utility of these exercises in clarifying public health workers’ roles and responsibilities, facilitating knowledge transfer among these individuals and organizations, and identifying specific public health systems-level challenges. In addition, Hites et al. (2010) identify what constitutes quality in public health emergency preparedness training and proposed guidance to practitioners in selecting training packages. Reference Hites and Altschuld661 This study describes the development and selection of guidelines for suitable high-quality courses.

In addition, Miller et al. (2007) describe a unique study that attempted to link specific learning methods of a public health leadership development program with participant outcomes. Reference Miller, Umble and Frederick331 This study finds that learning projects were strongly associated with developing collaborations, whereas assessment tools and coaching were most often associated with increased self-awareness. Potter et al. (2010) examine the evidence base for preparedness training effectiveness and consider whether past experience could help guide future efforts to educate and train public health workers in responding to emergencies and disasters. Reference Potter, Miner and Barnett347 This study concludes that reviews of progress in preparedness training for the public health workforce should occur regularly and that governmental investment in preparedness training should continue with future evaluations based on measurable performance improvement. However, Savoia et al. (2013) find limited analysis on what makes an exercise an effective tool to assess preparedness. Reference Savoia, Preston and Biddinger772 This project aims to achieve consensus on (1) attributes that make an exercise an effective tool to assess preparedness and (2) elements that make an after action report an effective tool to guide preparedness improvement efforts. In a separate article, Savoia et al. (2014) determine that evaluation of simulated emergencies has been historically inconsistent, and little research exists to describe how data acquired from simulated emergencies actually support conclusions about the quality of the public health emergency response system. Reference Savoia, Agboola and Biddinger569 This article proposes a conceptual framework to measure system performance during emergency preparedness exercises.

Discussion

This discussion frames the 5 themes identified as subjects that hold long-term strategic significance (ie, an educational continuum that extends to a foundational educational framework and a holistic perspective on leaders) and as areas that merit consideration for practical implementation through formative training and exercise programs.

Theme 1: Experiential Learning – Incorporating Realism into Training and Exercises

Lessons learned from real-world events and exercises have frequently served as the premise for establishing training priorities. While traditional instructional design entails passive learning, training design has evolved to incorporate active learning formats that not only provide students with opportunities to apply individual competencies for translating KSAA into actions, but also reflect on the outcomes of their actions to identify training needs and priorities.

Experiential learning serves as a prominent example of active learning for public health emergency response training. It allows students – or leaders in the context of this review – not only to apply leadership competencies to make incident management decisions or react/adapt to fluid emergency conditions, but also to evaluate the effectiveness of their decisions in minimizing adverse outcomes of an incident within context (eg, austere environments). In other words, the design and application of experiential learning for developing incident management leaders can be particularly impactful given the low-probability but high-consequence nature of public health emergencies and disasters. Reference Silenas, Akins and Parrish603

In the context of experiential learning to facilitate immersive and context-specific learning environments, educational games and simulation enhance training and exercise design and conduct as well as the assessment of technical competencies and personnel readiness in disaster medicine. Reference Araz, Jehn and Lant19,Reference Olson, Hoeppner and Scaletta249–Reference Olson, Scheller and Wey251,Reference Barnett, Everly and Parker289 For example, the Uniform Services University of the Health Sciences developed a military medicine training curriculum that consists of low-, mid-, and high-fidelity simulations as experiential learning tools to emulate combat field conditions. Reference Goolsby and Deering217 To standardize disaster medical assistance team training, the Australian Medical Assistance Team training incorporated extensive immersion training and exercise activities to assess personnel readiness. Reference Norton648 In addition, modeling and simulation tools augmented VR training for Ebola virus disease management in health care settings, immersive simulations for pandemic influenza preparedness training, and incident management training for decision makers. Reference Rega and Fink131,Reference Tena-Chollet, Tixier and Dandrieux159,Reference Sanjay259,Reference Ragazzoni, Ingrassia and Echeverri349

In application, the effectiveness of experiential learning relies upon the design (focusing on the learning environment) and delivery (focusing on the learner) of the educational intervention (ie, training and exercises). Specifically, employing PBL as a learning theory in training design provides a structured framework that facilitates data-driven and context-specific (eg, case-based scenario) analytical thinking to achieve learning objectives. With continuing advancements in and growing adaptation of technological innovations for training delivery, modeling and simulation (eg, disease propagation models, VR) add realism, context, and the perspective of austere environments to enhance the learner experience. Reference Stalker, Cullen and Kloesel155,Reference Goolsby and Deering217,Reference Streichert, O’Carroll and Gordon362 In conjunction, application of structured learning theories and technological tools extends experiential learning as a meaningful practice for reinforcing KSAA among training and exercise participants. For example, various disciplines have used PBL to provide emergency manager training for decision-making under stressful conditions, ranging from managing severe weather events to responding to bioterrorist attacks. Reference Stalker, Cullen and Kloesel155,Reference Streichert, O’Carroll and Gordon362

While there is tremendous value in experiential learning, this discussion does not discount the merit of passive learning through traditional instructional design (eg, classroom-based learning). While it does not entail an active participatory role among students, passive learning has established value in communicating new and vast quantities of information to large audiences. In the context of developing public health emergency response leaders, this discussion also recognizes the combined benefits of experiential learning (active learning) and traditional instructional design (passive learning) as an extension of blended learning to aid individuals in translating leadership competencies gained in a classroom setting to practical actions through context-specific or simulated environments. For example, in modernizing the military’s pedagogical methods for specialized unit training, the US Army adopts blended learning to integrate traditional instructional design and technological solutions to provide context-specific training. Reference Plifka395

Implications for the Public Health Community

While there can be tremendous value in experiential learning for public health departments and agencies across multiple levels of government, the practicality of developing such educational programs is a function of its demand across the public health community. Collaboration among federal, state, and local public sector partners can reduce the resource burdens associated with independently developing and implementing experiential learning products and materials. Beyond collaborative efforts within the public sector, interdisciplinary and external partnerships with academia may be considered to develop joint experiential learning programs (eg, shadowing programs to observe emergency operations center [EOC] activities).

The overarching implications of experiential learning on the public health community culminate with 2 key considerations. First, the scalability of existing experiential learning programs will dictate various public health departments’ or agencies’ ability to adopt, scale, and tailor these concepts, approaches, or processes for organizational or jurisdictional purposes. Second, as resource commitments rise with increasing complexity, recognizing the context of, need for, and resources accessible to develop, implement, and sustain experiential learning programs will be critical to their success.

Theme 2: Technological Adaptation – Describing the Evolution of Human-Driven Leadership to Technology-Assisted Leadership

Fluid crisis conditions require flexible and informed decision-making among emergency response leaders. The advent of and perpetual advancements in technological innovations have transformed crisis decision-making in recent years. While the emergency management community has increasingly embraced technological tools (see Figure 2), the capabilities of such tools have also expanded. For example, computer- or web-based tools that originated with information capture, presentation, and dissemination for maintaining situational awareness (eg, WebEOC, geographic information systems [GIS]) have evolved into complex decision support systems that encompass modeling and simulation capabilities to help decision makers plan for, respond to, and recover from disasters. Existing literature described decision support systems as a broad spectrum of technological innovation and tools, ranging from spreadsheet-based tools to commercially available software platforms. In the context of emergency response and crisis management, the recent transformation of crisis decision-making through the expansion and advancements in technology-aided decision support tools encompasses data integration platforms as well as sophisticated modeling and simulation capabilities to inform incident management decisions. For example, a seismic damage estimation case study in Canada integrates GIS and a specialized seismic risk assessment tool to provide the basis for identifying vulnerable areas and supporting risk management decisions. Reference Alam, Tesfamariam and Alam285 A diverse range of smartphone applications from public and private sector entities provides emergency notification, public information, and data visualization capabilities to support disaster and emergency response. Reference Bachmann, Jamison and Martin409 In addition, a policy informatics system using a simulation-based model integrates information from multiple data sources to support decision-making at the strategic and policy levels. Reference Barrett, Eubank and Marathe410

The growing adaptation of technology-based decision support tools also includes simulation-based resource modeling for public health preparedness and response, logistics support in humanitarian assistance, GIS-based spatial decision support, situational awareness for incident managers, and data mining and aggregation through social media platforms. Reference Araz and Jehn18,Reference Peng, Zhang and Tang127,Reference Sharma147,Reference Taniguchi, Ferreira and Nicholson158,Reference Leaming, Adoff and Terndrup227,Reference Little, Loggins and Wallace235,Reference Stein, Rudge and Coker264,Reference Chalfant and Comfort418,Reference Hupert, Mushlin and Callahan434,Reference Chang and Li507,Reference McCormick522,Reference Ren, Wu and Hao600

Reflecting on the growing trend in technological adaptation that may be attributed to the emergence of technological innovations and increasing output in literature over time, the evolution of human-driven to technology-assisted leadership has considerable implications on (1) research and development of technological tools for crisis management, (2) training on the proper and practical application of technological tools in crisis management, and (3) technology-aided design and delivery of educational interventions (ie, training and exercises), in general.