Much of the current political science research distinguishes between ‘economic’ and ‘social/cultural’ policy issues, thereby (at least implicitly) assuming that reasoning about economic issues follows a cost–benefit logic, while reasoning on social-cultural issues follows a moral, value-based or identity-related logic (Tavits Reference Tavits2007; Benoit and Laver Reference Benoit and Laver2006).

In this study, we analyse voters' justifications for their vote decisions in direct democratic votes using justifications as an indicator of their type of reasoning on policy issues. We distinguish between pragmatic arguments, which rely on consequentialist reasoning based on (economic or other) cost–benefit calculations, and principled arguments, which relate to moral or social norms, values or perceptions of identity. We address two questions. First, do voters justify their political decisions in direct democracy using pragmatic or principled arguments? Secondly, what are the determinants of principled versus pragmatic reasoning?

Drawing on research on morality in political reasoning as well as on framing theory, we consider three possible determinants of principled versus pragmatic reasoning. First, the nature of the issue might be decisive, that is, the policy domain of the vote (Engeli, Green-Pedersen, and Larsen Reference Engeli, Green-Pedersen and Larsen2012; Mooney and Schuldt Reference Mooney and Schuldt2008). Secondly, traits and predispositions of individual voters might determine whether they tend to reason in pragmatic or principled terms (Ryan Reference Ryan2014; Skitka Reference Skitka2010). Finally, arguments delivered to voters during the political campaigns might affect their reasoning (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Hobolt Reference Hobolt2009).

Direct democratic decisions, that is, ballot votes on referendums and popular initiatives, are an interesting setting in which to study these questions for two reasons. First, the use of direct democratic instruments has increased in recent years, and studying the processes that leads to public opinion formation is therefore becoming more important, as the legitimacy of these decisions depends on the voters' reasoning. Secondly, popular votes provide an ideal real-world opportunity to study opinion formation processes, as voters decide directly on policies that affect their lives. For this analysis, we use an original dataset of post-ballot surveys conducted after thirty-four popular votes in Switzerland, covering a range of policy domains. The dataset contains the answers to an open-ended question that asks respondents to justify their vote decisions.

A quantitative content analysis of these open-ended answers reveals that throughout all policy domains, principled and pragmatic reasoning are equally frequent. Rather surprisingly, the type of reasoning reported by voters does not significantly depend on the policy domain of the vote, as the distinction often drawn between two types of issues would suggest. Instead, there is a strong correlation between the dominant campaign arguments and the type of reasoning. Thus the arguments put forward during the campaign seem to be more important for the way voters approach a political question than the nature of the issue per se. Moreover, a voter's personal characteristics significantly affect his or her type of reasoning. The remainder of the article will first introduce some theoretical background, then describe the data and the coding procedure of the open-ended answers. Finally, it presents descriptive analyses and hierarchical models testing the determinants of principled versus pragmatic reasoning.

Why Study Justifications?

Arguments are essential in democratic decision making because they allow elite actors and citizens to engage in a common public discourse on political issues. Deliberation theory depicts mutual justification and the exchange of arguments as the central element of democratic decisions. Actors are rational when they are able to justify and explain their actions (Cohen Reference Cohen, Hamlin and Pettit1989; Habermas Reference Habermas1993; Thompson Reference Thompson2008). Not only are arguments central to an informed public debate, they can also reveal how voters perceive and approach different policy issues. In this study, we use voters' justifications as an indicator of whether they reason in principled or pragmatic terms about a policy.

Some scholars claim that the reasons voters give to explain their political decisions are often post hoc rationalizations of decisions that are actually based on unconscious and automatic psychological processes (Haidt Reference Haidt2001; Reference Haidt, Scherer, Davidson and Goldsmith2003; Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge and Taber2013; Skitka Reference Skitka2010). Our data do not allow us to examine this claim. We maintain, however, that the arguments reported by voters are nonetheless revealing, as they shape the public debate and how voters engage in public deliberation on the ballot. Furthermore, while voters may not always be aware of their underlying psychological motives, we assume that they mostly answer the questions honestly, as we see no strategic motive to report false justifications.

Two Types of Issues?

Scholars of party competition widely recognize the distinction between economic and social-cultural issue dimensions in the political space (Benoit and Laver Reference Benoit and Laver2006; Laver Reference Laver2001; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2006; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2012; Van der Brug Reference Van der Brug1999). These two dimensions represent the two central political conflict lines in today's affluent societies: a distributional (economic) conflict and an identity-based (cultural) conflict. The economic dimension refers to topics such as economic planning, free enterprise, incentives and taxes policies, market regulation, corporatism and protectionism and is usually associated with material cost–benefit considerations and consequentialist reasoning. The social-cultural dimension refers to issues such as immigration, gay rights, abortion and gun control (see, for example, Tavits Reference Tavits2007), which are perceived in terms of values, culture or identity.

However, for many issues, the categorization into these two issue dimensions is not clear-cut (Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Häusermann, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015). For example, welfare state and social justice issues have moral as well as economic components. Likewise, although immigration is often cited as a prime example of a cultural policy (Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010), many studies show that economic factors such as skill level and exposure to globalization remain important determinants of immigration attitudes (Dancygier and Walter Reference Dancygier, Walter, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014). While these studies explore whether voters' opinions are determined more by economic or by value-based or cultural factors, our analysis takes a different approach and analyses how voters justify their decisions on these issues. According to Habermas' theory of communicative action (Reference Habermas1981), actors are rational when they are able to explain their actions. Studying the reasons and arguments voters give should help us better understand their decisions. We first categorize their justifications into principled versus pragmatic, as explained below, and then analyse possible determinants of these types of justifications.

In order to develop a set of hypotheses about these determinants, we draw on research on morality in political reasoning. Scholars of morality policy distinguish between ‘moral’ and ‘non-moral’ issues. Engeli, Green-Pedersen and Larsen (Reference Engeli, Green-Pedersen and Larsen2012, 23) define moral issues as ‘related to fundamental questions, such as death, reproduction, and marriage’ and contrast them with ‘the usual topics on the agenda’ (1) such as welfare state reforms, the environment or financial policy. Similarly, Mooney (Reference Mooney2001) describes moral issues as generating conflicts of basic moral values, and as widely salient and technically simple. These scholars generally recognize a clear distinction between moral and economic issues, even though some issues, such as the environment, are categorized as moral by some scholars and non-moral by others. Other issues, such as smoking regulations, have evolved from non-moral to moralized issues over time. They usually agree, though, that economic issues such as tax policy and welfare state reforms are not moral issues – which is puzzling if we think of principles such as fairness, equality or self-reliance guiding many of these economic issues.

Scholars of morality politics mostly assume that morality is derived from the politics surrounding a certain issue, rather than from the intrinsic substance of the issue (Haider-Markel and Meier Reference Haider-Markel and Meier1996; Mooney Reference Mooney2001). They suggest that an issue becomes moral when at least one relevant actor uses moral arguments in the debate. This is in line with a wealth of findings in framing research, which suggest that the way political elites and the media frame an issue has crucial effects on voters' thinking about the issue (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Druckman, Peterson, and Slothuus Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013; Nelson and Oxley Reference Nelson and Oxley1999; Scheufele Reference Scheufele2000). Campaigns are crucial in referendums, maybe even more so than in elections. Because referendums are about single issues that may be unfamiliar to voters, they might have little knowledge and no clear pre-existing opinion, so campaigns can potentially have a more profound effect (Binzer Hobolt, and Brouard Reference Binzer Hobolt and Brouard2011; Kriesi Reference Kriesi2012; LeDuc Reference LeDuc2002).

Regarding principled versus pragmatic reasoning, Domke, Shah and Wackman (Reference Domke, Shah and Wackman1998) and Shah, Domke and Wackman (Reference Shah, Domke and Wackman1996) showed in framing experiments that whether individuals perceive health care in moral-ethical or economic-pragmatic terms substantially depends on the framing of newspaper articles to which they were exposed. In a recent experimental study Leidner, Kardos and Castano (Reference Leidner, Kardos and Castano2017) find that moral arguments have a stronger effect on increasing opposition to torture than pragmatic arguments. These studies show how the framing can crucially affect whether voters reason about this issue in principled or pragmatic terms.

More recent work on moral reasoning and moral conviction in political psychology pushes back on the idea that there are clear boundaries between the two issue types. These studies assess moral attitudes as an individual-level and situational concept and suggest that whether an issue is perceived in moral terms or not lies primarily in the eye of the beholder (Amit and Greene Reference Amit and Greene2012; Biggers Reference Biggers2011; Ryan Reference Ryan2014; Skitka Reference Skitka2010). According to these authors, the morality of a political attitude varies on the individual level, as well as between issues. Skitka (Reference Skitka2010) defines moral convictions as consisting of ‘evaluations based on morality, and immorality, right and wrong’, in contrast to attitudes more generally, which are made up of positive and negative evaluations of attitude objects.

These scholars agree, however, that morality constitutes a distinct quality of political attitudes, which implies specific behavioural, cognitive and emotional consequences. Compared to strong attitudes that are non-moral (for example, preferences or conventions), moral attitudes are found to trigger stronger emotional reactions (negative and positive), a lower tolerance for disagreeing others and stronger one-sided political thinking, less willingness to compromise, difficulties for conflict resolution and decreasing obedience to authorities (Garrett and Bankert Reference Garrett and Bankert2018; Ryan Reference Ryan2014; Skitka Reference Skitka2010). Furthermore, studies find increased political engagement and participation (Biggers Reference Biggers2011; Grummel Reference Grummel2008; Skitka and Bauman Reference Skitka and Bauman2008) when attitudes are moral.

This discussion raises the question of whether voters indeed think about economic issues in pragmatic terms and about cultural issues in value-based terms. Which factors determine whether voters reason in principled or pragmatic terms? Is their reasoning mainly driven by the type of issue, or by characteristics of the voters themselves? Or does the political discourse and public debate surrounding the issue define whether a policy decision is perceived as pragmatic or principled? As few studies have investigated the antecedents of voters' principled versus pragmatic reasoning, this study takes an exploratory approach and examines three hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (Issue Hypothesis)

Whether voters justify their ballot decisions based on pragmatism or principles depends on the nature of the issue. We expect typical issues of the economic dimension and putative non-moral issues to be associated with more pragmatic justifications, and social-cultural or putative moral issues to be associated with more principled reasoning.

Hypothesis 2 (Voter Hypothesis)

Whether voters justify their ballot decisions based on pragmatism or principles depends on the voter's individual predispositions. We expect more principled reasoning when an individual has strong opinions about an issue.

Hypothesis 3 (Framing Hypothesis)

Whether voters justify their ballot decisions based on pragmatism or principles depends on the arguments/frames, which are dominant in the public campaign preceding the vote.

Principled Versus Pragmatic Reasoning

Central to this debate is the distinction between principled and pragmatic attitudes. We rely on the distinction between pragmatic and value-based frames, as used in studies on European Union (EU) politicization. This argumentation-theoretical approach, based on Habermas' theory of communicative action, is particularly well suited to analysing voters' justifications, as it concentrates on the content and types of arguments used, rather than on the underlying motives of actors (Lerch and Schwellnus Reference Lerch and Schwellnus2006). Following this approach, we distinguish on a basic level between two types of arguments: pragmatic and value-based (Helbling, Höglinger and Wueest Reference Helbling, Höglinger and Wueest2010; Lerch and Schwellnus Reference Lerch and Schwellnus2006; Medrano Reference Medrano2003; Sjursen Reference Sjursen2002).

When actors use pragmatic arguments, they base their decisions on reasons of material gain and justify policies by referring to their expected output, in a utilitarian way. Principled or value-based arguments, by contrast, comprise identity-related and universalistic arguments. Identity-related arguments are based on an actor's ‘sense of identity or understanding of the “good life”’ (Sjursen Reference Sjursen2002, 493). They rely on certain values perceived as representative of a specific community. Finally, actors can draw on their sense of fairness when explaining their actions, therefore using universalistic arguments. Footnote 1 Here, the perspectives of all concerned actors have to be considered in order to find a solution that could be acceptable to everyone. Arguments based on human rights, global UN standards or other universally valid moral principles, such as tolerance or equality, fall into this category.

It is important to note here that the researchers have consciously made this twofold distinction between types of justifications. We acknowledge that the nature of an argumentation is sometimes not as clear-cut and exclusive as in this typology. However, the present classification and coding represents an attempt to get at two of the main categories of argumentation in public discourse that previous studies have found to affect citizens' opinions and behaviour on certain policy issues.

Research Design, Data and Measurement

Data

This study is based on a combination of two datasets (see Kriesi Reference Kriesi2005 for a similar procedure, Milic Reference Milic2009). At the individual level, we use a dataset of cross-sectional post-ballot surveysFootnote 2 conducted within 1 week of federal-level popular votes in Switzerland using computer-assisted telephone interviewing.Footnote 3 The surveys are based on representative samples drawn through stratified random sampling of the population of all Swiss citizens who are eligible to vote. The samples are representative of the Swiss population in all relevant socio-demographic respects except for the participation rate, which is higher than actual average turnout (61.6 per cent vs. 44.4 per cent). In the present study, however, we analyse only the data of respondents who report that they voted in the referendum. Only these respondents are asked to justify their vote decision in the survey.

The dataset contains data on voters' justifications for all thirty-four federal-level votes that took place between 2008 and 2012,Footnote 4 covering different policy domains. It also contains information on all individual-level variables employed in the study, that is, sociodemographic variables, political predispositions and preferences regarding the vote (see variable descriptions below). The unit of analysis constitutes a response given by a respondent on a specific proposition. The individual-level dataset contains 26,621 observations on thirty-four votes. Finally, for the purpose of a multilevel-analysis, this individual-level dataset is combined with a second, context-level dataset that contains information on the policy domain of the vote (referendum/initiative), the most important campaign arguments, the complexity of the vote, and other elite- and campaign-related variables.

Main Outcome Variable: Type of Justification

The main outcome variable is the type of justification given by a voter with regard to a specific proposition. It is based on a quantitative content analysis of an open-ended survey question, which asks respondents for the most important reasons of their vote decision. The question reads as follows: ‘Which are your main reasons for accepting / rejecting the proposal XY?’

These answers range from a few words and sentence fragments to two or three full sentences. Two trained research assistants coded them for the type of justification reported (see Table 1). In a first step, we distinguished policy-related answers from non-policy-related answers. A policy-related justification is every answer that refers to the policy content of the vote.Footnote 5 In total, 69 per cent of respondents report a policy-related argument when asked to justify their decision. Of course, one first interesting question is, who gives a policy-related answer and who does not? This is not the focus of the current study, however. We have analysed the selection into giving a policy argument as well as the complexity of these arguments elsewhere (Colombo Reference Colombo2019) and found that the strongest predictors of providing a policy-related argument (versus non-policy-related answers) are an individual's political interest, and the complexity of the issue on the ballot. The present study focuses on principled versus pragmatic reasoning; we will therefore focus only on policy-related arguments. The large majority of respondents (85 per cent) mentioned only one argument (see Appendix Table A5).

Table 1. Coding examples types of justifications

These policy-related arguments were then coded into a scheme of subcategories as presented in Table 1 (see Appendix Table A1 for the detailed original coding scheme). Following the work discussed above, these categories can broadly be subsumed into pragmatic and principled arguments. Pragmatic arguments contain arguments referring to one of the following categories: economic/material cost–benefit, security or political efficiency. Economic cost–benefit arguments refer either to direct personal costs or benefits of the respondent or to costs and benefits more generally, for the country as a whole; they therefore comprise pocketbook and sociotropic pragmatic arguments. Security arguments refer to law enforcement, law and order, or personal and national security. Political efficiency arguments refer to efficient and effective procedures, feasibility and proportionality concerns, and arguments about bureaucracy (red tape).

Principled arguments comprise identity-related/cultural arguments as well as universalistic value arguments. Identity-related or cultural arguments refer to national values and tradition, separation from the rest of the world, religious concerns and different social groups, such as age and class groups, ethnic groups or immigrants. Within the category of universalistic values, the largest group is fairness or social justice and injustice arguments. Other universalistic values comprise equality, solidarity, sustainability, democracy or progress. Specific principles refer to principles held by specific groups such as animal rights or environmental protection. Legal arguments are coded as principled arguments because they refer to universally valid legislation such as the Swiss constitution or legislation, the rule of law, or international law such as the European Convention of Human Rights or the UN Human Rights declaration. Finally, institutional arguments mainly refer to questions of institutional competence, in most cases the question of federal versus cantonal competencies or direct democracy and citizens’ right to participate in political decisions.

This categorization proves to be comprehensive. Only 2.8 per cent of the policy-related answers were coded as residual (missing) because they did not fit into any of these categories. Intercoder agreement was established by calculating Cohen's Kappa (k), a widely used statistical measure of intercoder agreement. The agreement between the two coders reached 83 per cent (k = 0.801), which is classified as almost perfect agreement.

Individual-Level Covariates

Political interest is measured by the standard question: ‘In general, how interested are you in politics?’, with answers ranging from 0 (not at all interested) to 3 (very interested). The questionnaire contained a measure of the personal relevance of the issue on the ballot for the respondent. The question reads: ‘Now, let's talk about the importance of this issue for you personally. How important was issue X for you personally?’ The answer scale ranged from 0 (not at all important) to 10 (very important). Political ideology is captured by a left–right self-placement measure (where 0 represents ‘very left-wing’ and 10 denotes ‘very right-wing’) as well as by a measure of partisan preference. Appendix Tables A2 and A3 provide summary statistics for the variables of interest. Further measures include vote decisions, measured as acceptance versus rejection of the proposal (and thus votes for the status quo), as well as sociodemographics (education, age, gender and language, as Switzerland is divided into three language regions, German, French and Italian speaking, each of which has a separate regional media).

Issue-Level Covariates

We distinguish between eight policy domains (see online Appendix Table A6 for a list of all issues and policy domains): institutional, fiscal, culture/education/law, foreign policy/peace, immigration, social policy and ecology. These categories provide a meaningful distinction of different policy domains in Swiss direct democracy and have been used in previous studies (Kriesi Reference Kriesi2005). The share of respondents who report difficulties when making a decision measures issue complexity.

Empirical Results

Before presenting the results of our multilevel analysis, it is instructive to look at the distribution of the types of justifications in the sample. Figure 1 shows the percentage of respondents for each type of justification in the whole sample (n = 17,817). Universal values, legal arguments, institutional arguments, identity-related arguments and specific principles constitute the categories of principled arguments, while the pragmatic arguments comprise economic, efficiency and security arguments. In total, principled and pragmatic arguments are used in almost equal shares (52.6 per cent pragmatic versus 47.4 per cent principled). Arguments referring to universal values constitute the most frequent category, with almost one-third of the sample. Of the pragmatic arguments, economic cost–benefit arguments (25.3 per cent) and political efficiency and efficacy arguments (20.5 per cent) are the most frequent.

Figure 1. Distribution of policy-related answers

Note: based on entire sample (n = 17,817).

Figure 2 shows the proportion of principled versus pragmatic arguments for different policy domains. Both types of arguments are used in every policy domain. As we would expect, propositions on immigration and cultural policy yield the highest rate of principled justification with 54.5 and 52 per cent principled answers respectively, together with institutional argumentsFootnote 6 (see Appendix Table A4 for the exact proportions of principled versus pragmatic answers).

Figure 2. Proportion of principled versus pragmatic justifications over policy domains

As expected, immigration policy votes also received the highest share of identity-related answers among all policy domains (16 per cent of all policy-related answers for immigration propositions). Still, this share of identity-related arguments is quite low, especially given the fact that all the immigration initiatives (including the minaret ban and the deportation initiative)Footnote 7 were launched by members of the right-wing populist Swiss People's Party, which is said to mobilize strongly on identitarian grounds. Social desirability motivations might play a role here (that is, respondents may refrain from reporting identitarian justifications), even though the respondents were guaranteed anonymity by the interviewers. A closer look at the different immigration initiatives shows that proponents often argued with security and law and order arguments (for example, ‘the deportation initiative helps to lower crime rates’), while opponents often reported efficiency reasons, such as labelling the proposition as exaggerated, ineffective or unfeasible. As mentioned above, our data do not allow us to unmask respondents’ original motivation, but we can analyse the rhetoric used.

In fiscal policy, somewhat unexpectedly, a large part (46.7 per cent) of the arguments refer to principles. Of the four fiscal propositions in the sample, two referred to tax policy, while the other two concerned book price fixing and gambling legislation. The titles of these propositions show that they were debated in principled terms: one initiative, launched by the political left, was called ‘The tax justice initiative’, while the other one, a property tax initiative launched by property owner-interest groups, was called ‘For safe housing in old age’. As these titles indicate, the proponents of the proposals used fairness principles to promote their cause. For social policies, by contrast, pragmatic reasoning predominates. While this might be surprising at first sight with questions of redistribution, the list of all votes analysed (available in Appendix Table A6) shows that in the social policy domain, most votes concerned welfare state institutions such as pensions, unemployment insurance or health care insurance. Thus in times of austerity and retrenchment, it is not surprising that cost and profitability arguments dominated many debates (in particular, the high costs and the long-term preservation of welfare state institutions).

In sum, Figure 2 and Appendix Table A4 show that voters in these direct democratic votes used principled and pragmatic arguments equally frequently. The policy domain does not seem to determine the type of reasoning. In order to analyse this question more systematically, we next present a multilevel analysis of the determinants of pragmatic versus principled reasoning.

Multilevel Models

Model Specification

The unit of analysis is a respondent's justification for a certain proposition. The main dependent variable in these models is the binary distinction between a pragmatic and a principled justification (pragmatic justifications are coded as 1). While individuals differ in the type of justifications they provide, it is important to note that different propositions might also trigger different types of arguments. To the extent that respondents justify their decisions regarding a particular proposition in a similar way, there is clustering at the proposition level. For this reason, we use hierarchical models. Model 1 includes only individual-level predictors of justification type in a logit model with standard errors clustered by proposition, while Models 2 and 3 present two-level random-intercept logit models, including predictors at the proposition level. In these models, the type of justification y for a given person and a given proposition j is represented as a function of individual- and proposition-level characteristics.

At the individual level, following Hypothesis 2, we include a measure of personal relevance of the issue. Further, we include a measure of ideological self-placement along the left–right dimension to account for the possibility that political ideology might affect the type of reasoning. Finally, we include a set of control variables: education and political interest, as two prominent determinants of political sophistication, a set of socio-demographic controls (age, gender, language region), and a measure of acceptance versus rejection of the proposal to account for the fact that supportive (pro) arguments might be different in nature from opposing (contra) arguments. On the context level, following Hypothesis 1, we are principally interested in the effect of the different policy domains. We also control for the complexity of the proposition to account for the possibility that this might affect the type of reasoning.Footnote 8 The estimation was performed using the xtmixed command in STATA for mixed-effects logistic regressions. The model coefficients are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Regression of justification type on individual- and proposition-level predictors

Note: logit coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. Model 1: logit model with standard errors clustered by proposition. Models 2–5: random-intercept multilevel logit models. Dependent variable = type of answer (1 = pragmatic/0 = principled). †p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Results

Looking at the individual-level correlates of pragmatic reasoning in Model 2 shows, first, that if an issue has higher personal relevance for a voter, this is associated with more principled (and less pragmatic) reasoning. More precisely, the predicted probabilities (based on Model 3) show that someone who finds an issue not at all personally relevant has a 60 per cent probability of giving a pragmatic answer, while someone who finds an issue highly personally relevant has only a 49 per cent probability of doing so, holding all other variables at their mean. This effect appears only in the random-intercept models, however. This finding is in line with Hypothesis 2 (Voter Hypothesis).

Secondly, we find that right-wing ideology has a strong significant effect on pragmatic reasoning. In substantive terms, while someone who considers herself very left wing has a 42 per cent of providing a pragmatic argument, a respondent on the ‘very right-wing’ end of the scale has a 64 per cent probability, holding all other variables at their mean.

Furthermore, we find that accepting a proposition is associated with more principled reasoning. The probability of giving a pragmatic argument is 58 per cent if a proposal is rejected, and 47 per cent if it is accepted. This finding suggests that voters tend to reject policies on pragmatic grounds and to accept them on principled grounds.Footnote 9 These results lend some support for Hypothesis 2, which states that the type of justification depends on the voters' individual characteristics.

Yet what is more surprising are the effects at the context level. The policy domain does not appear to significantly affect the type of reasoning. Neither of the policy domains has a statistically significant effect on the type of reasoning (p < 0.05), and this result does not depend on the choice of reference category. Nor does the complexity of the proposition significantly affect the type of reasoning. Looking at the predicted probabilities of pragmatic reasoning for the different policy domains (see Figure 3, based on Model 3), we find the largest differences between foreign policy issues (41 per cent probability of pragmatic reasoning) and fiscal issues (62 per cent), but the predicted probabilities again show that none of the differences is statistically significant.

Figure 3. Predicted probability of giving a pragmatic answer by type of strongest campaign argument

Note: includes 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Grouping the different policy domains into two dimensions – an economic-pragmatic (fiscal and economic issues) and a social-cultural one (social, cultural and immigration questions) – does not significantly affect the type of justification either, as Model A5 in Appendix Table A7 shows. We tested different categorizations of the policy domains into two dimensions, but none of these two-dimensional categorizations is significantly associated with justification type. The policy domain of the ballot question does not appear to affect the type of voter justification. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is not supported by the data.

What is it, then, that determines whether voters think about an issue in principled or pragmatic terms? According to framing theory, the most plausible explanation is probably that public discourse during the campaign frames voters' reasoning about an issue. In order to test this hypothesis, ideally we could conduct an experiment, in which we expose voters to certain campaign frames and then assess their type of justification. However, no such data are available for the votes analysed here. We do, however, have two different measures capturing the strongest argument in each campaign. First, one major Swiss quality newspaper, the Tagesanzeiger, publishes a short overview of the content of the proposal, the main actors' positions, and the main pro- and contra arguments in the debate about 1 month before every vote.

From these summaries, we collected the main argument of the winning camp for each vote and coded it as either pragmatic or principled. We used the main argument of the winning camp based on the assumption that this must have been the most prominent and convincing campaign argument.Footnote 10 As the last column in Appendix Table A4 shows, for almost every policy domain, there were campaigns run primarily on a pragmatic argument and others run mainly on principled arguments. In line with the previous finding, certain types of campaign arguments are not necessarily tied to certain policy domains – there are principled as well as pragmatic immigration campaigns, for example. In total, twenty-two of the thirty-four campaigns were dominated by a pragmatic argument.

Model 3 includes this dichotomous measure of principled versus pragmatic media discourse and finds a strong effect on the type of justifications reported by voters. As Figure 4 shows, when the strongest campaign argument is a pragmatic one, respondents have a 64 per cent probability of reporting a pragmatic answer; this predicted probability is only 32 per cent when the strongest campaign argument is principled. This supports Hypothesis 3.

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of giving a pragmatic answer by policy domain

Note: includes 95 per cent confidence intervals.

From this analysis, it is difficult to determine conclusively whether the campaign really affects the justifications voters use, or whether campaigns instead pick up the arguments that are most popular in the public opinion. In other words, the direction of causality is difficult to establish. Even though the causality of our data cannot be established conclusively, several additional tests suggest that campaign arguments affect voters' justifications and not the other way around.

First, we used an alternative campaign framing variable based on national polls conducted in two waves prior to the vote by the same company that conducted the post-ballot surveys on a representative sample of approximately 1,000–1,500 respondents. These surveys ask respondents about their agreement with a set of (4–6) pro and contra arguments that were debated during the campaign. A team of experts selected these arguments prior to the beginning of the official campaign (three months in advance, since this is when public campaigns usually start). Since at this time there was no intensive public debate about the issue yet, it is more likely that these arguments affected the subsequent debate and not the other way around.Footnote 11

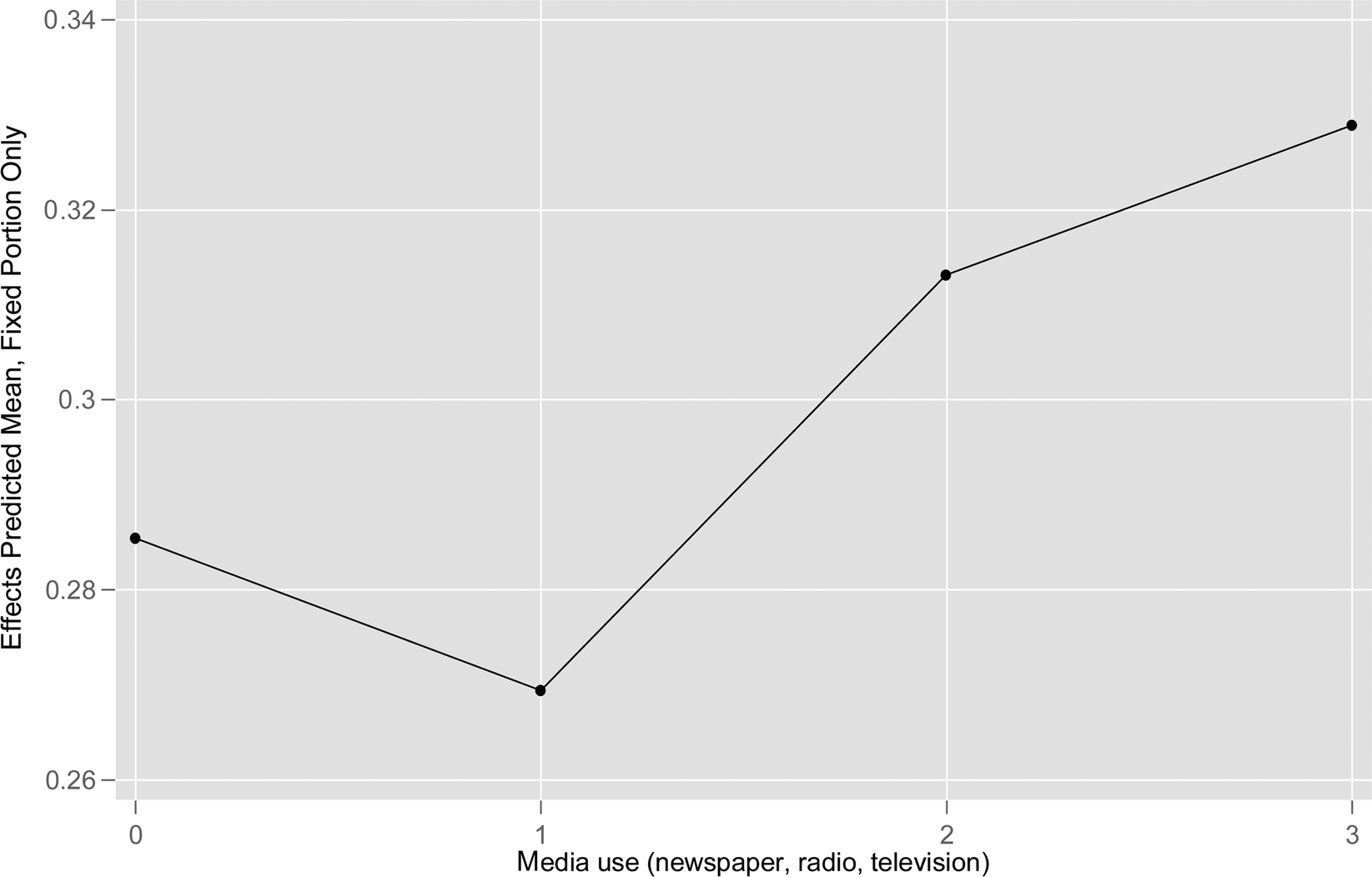

As an additional test, Models 4 and 5 include a variable of individual media use and a cross-level interaction of respondents' media use with the effect of campaign arguments. The Media Use variable in Model 4 measures how many different media (newspaper, radio, television) a respondent reported using during the campaign, while the variable in Model 5 only measures whether a respondent reported using newspapers as an information source about the vote or not. Both variables have a significant positive cross-level interaction with the effect of the strongest campaign argument. This means that the effect of campaign arguments on justification type is stronger for respondents who consume more news media compared to those who consume less. Figure 5 (based on Model 4) shows that the average marginal effect of the strongest argument on the type of justification decreases by about 5 per cent for those who do not consume any news media compared to frequent news media consumers, holding all other variables in the model at their mean. This lends additional support to the hypothesis that the campaigns run in the media affect the moral versus pragmatic justification type.

Figure 5. Average marginal effect of the strongest campaign argument on the type of justification (principled/ pragmatic) for different levels of new media use

Note: 0 = no news media used for information about the vote, 4 = high media use.

Figure 6 presents the proportions of pragmatic and principled justifications for every issue. It shows that issues belonging to the same domain can have quite different shares of pragmatic justifications. For example, while the minaret ban is justified mostly in principled terms (79 per cent principled arguments), the deportation initiative is discussed much more in practical terms (41 per cent principled arguments). Among the social issues, health insurance propositions raise discussions about fairness and right to treatment, while a pension reform and a reform of the retirement age were discussed more in pragmatic terms, which focused on the profitability and long-term survival of welfare state institutions.

Figure 6. Proportion of pragmatic versus principled reasoning by issue

Note: soc = social, for = foreign policy/peace, cult = culture/education/law, im = immigration, ins = institutions, fisc = fiscal.

This shows that policy issues can be approached from different angles, and that the way the debate is led largely determines how voters think about an issue. To sum up, these results lend support to the Voter Hypothesis (Hypothesis 2), which predicts that individual characteristics affect the type of reasoning, and to the Framing Hypothesis (Hypothesis 3), which predicts that campaign arguments determine the reasoning type. The Issue Hypothesis (Hypothesis 1), which expects the policy domain to significantly shape the type of reasoning, finds no support.

Robustness Checks

First, in order to test the robustness of the results to different categorizations of the principled versus pragmatic argument distinction, we replicated Models 2 and 3 after categorizing institutional arguments as pragmatic (instead of principled) and, secondly, categorizing specific principles as pragmatic (instead of principled) (see Models A1 and A2 in Appendix Table A7). These two categories were the most difficult to categorize as either principled or pragmatic. However, all results hold in these different categorizations.

Secondly, Model A3 in Appendix Table A7 shows that all results hold when using partisan preference instead of left–right self-placement; right-wing party supporters show significantly more pragmatic justifications and left-wing supporters significantly more principled justifications compared to non-partisans and to supporters of centrist parties. Finally, Model A4 in Appendix Table A7 shows that substituting the strongest campaign argument variable with an alternative measure, based on pre-ballot surveys, decreases the precision of the estimation but still yields a significant positive effect of campaign arguments.

Discussion and Conclusions

Knowing how voters reason about different policy issues is essential, as it determines the way they approach and decide about those issues in democratic settings. Granted, our content analysis measures principled versus pragmatic justifications and does not exactly capture whether an attitude is moralized or held with moral conviction, and therefore our measurement differs from research on attitude morality. However, we take principled justifications as an indicator, if only an imperfect one, of attitudes held by principle. Therefore we believe our results are of interest to scholars researching moral attitudes.

The most striking result of this analysis may be that principled or pragmatic reasoning are not inherent to the nature of certain issues. That is, a question's policy domain does not necessarily determine how voters reason about this issue. Citizens discuss immigration issues in pragmatic terms at times, invoking concerns about security, or the effectiveness and costs of a proposed policy measure. At other times, they discuss immigration in principled terms, such as protecting national identity versus granting universal human rights. Tax policy can be discussed either as a matter of fairness or as a matter of fiscal responsibility and consequences for the national budget. This contradicts the strong twofold distinction between economic and social-cultural or between moral and non-moral issues that is often drawn, and is more in line with the findings from moral political psychology.

Different individuals appear to assess the same issue differently, or as Ryan (Reference Ryan2014) has put it, principled reasoning varies not only between issues, but also within issues. Principled reasoning is significantly more common with issues deemed to be personally relevant. This fits well with research on attitude moralization that has found significant correlations between moral attitudes and attitude strength. While Ryan (Reference Ryan2014) conceptualizes morality as one dimension of attitude strength, Skitka (Reference Skitka2010) distinguishes attitude strength from moral conviction, stating that there can be strong attitudes without moral conviction. Both authors, however, conceptualize moral conviction as a distinct construct, and they both show that moral conviction correlates with dimensions of attitude strength like attitude extremity, importance, relevance and centrality. The concepts measured in this study are slightly different – in particular, we do not have a measure of moral conviction, which tends to correlate with personal relevance, and therefore cannot test whether it is personal relevance or actual moral conviction that drives principled reasoning. Nevertheless, we can confirm that principled reasoning is associated with issues of high personal relevance. With strong attitudes, we tend to argue more with principles and less with consequences.

Endorsement of a policy proposal is also correlated with principled reasoning: voters report more principled reasons when they accept a proposal and more pragmatic reasons when they reject it. Together, these findings indicate that we tend to take a principled position with issues we feel strongly and positively about. It therefore appears that voters use principled language to promote political change, but employ pragmatic language to defend the status quo. Here again, the comparison to research on moral attitudes is interesting even though we do not directly measure the morality of voters' opinions.

Morality theorists often focus on rules, social norms, avoidance of immoral actions or avoidance of harm (Graham, and Haidt Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009; Gray, Schein, and Ward Reference Gray, Schein and Ward2014; Haidt Reference Haidt2012; Schein, Gray, and Bulletin Reference Schein and Gray2015). In our dataset, we find that universal values are mainly used to promote social change, and in particular social justice, since arguments related to fairness and social justice are the more frequently mentioned universal values.

Janoff-Bulman's theory of moral motives appears to capture this positive use of moral norms by distinguishing between approach- and avoidance-oriented morality, where approach-oriented morality promotes activation and a focus on positive outcomes (Janoff-Bulman and Carnes Reference Janoff-Bulman and Carnes2013; Janoff-Bulman, Sheikh and Baldacci Reference Janoff-Bulman, Sheikh and Baldacci2008; Sheikh and Janoff-Bulman Reference Sheikh and Janoff-Bulman2010). In particular, she conceptualizes social justice morality as the moral concern of ‘providing for the welfare of the group’ (Janoff-Bulman and Carnes Reference Janoff-Bulman and Carnes2013, 222). This concept of a sociotropic motive to further the welfare of the whole country/economy/society corresponds well with the universal values that are frequently mentioned in our dataset. Janoff-Bulman, Sheikh and Baldacci (Reference Janoff-Bulman, Sheikh and Baldacci2008) find that social justice morality is significantly correlated with liberalism. In our study, principled reasoning is more frequent among left-wing voters, as discussed in the next paragraph.

Regarding partisanship, in the US context, some have argued that conservatives are more likely to hold strong moral convictions, due to authoritarian predispositions (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1996), adherence to a Protestant work ethic (Furnham Reference Furnham1984), stronger conventional morality (as opposed to moral relativism, see, for example, Layman Reference Layman2001) or a stronger focus on cultural issues (Frank Reference Frank2004; Westen Reference Westen2008). Others argue that both liberals and conservatives are equally likely to hold moral attitudes, but that they differ in the moral values they find important (Lakoff Reference Lakoff2002). Both Skitka, Morgan and Wisneski (Reference Skitka, Morgan, Wisneski, Forgas, Crano and Fiedler2015) and Ryan (Reference Ryan2014) find moral attitudes to similar extents among Republican and Democrat respondents. Our analysis does not measure moral values, but rather justifications based on principles and values, which might at least partially explain the different findings in the Swiss context. In Switzerland, right-wing voters are significantly more likely than left-wing voters to justify their decisions using pragmatic arguments. If we look at the specific arguments used by both sides, we find that arguments regarding fairness, equality, universal rights and the rule of law are more frequent on the political left, and that this drives the effect. This comes as a surprise, given that much of the recent direct democratic mobilization was driven by the populist right, which is often said to mobilize on identitarian grounds.

Finally, and most importantly, we find that the arguments brought forward by the different camps during the campaigns significantly affect the type of reasoning. If the dominant campaign argument is principled, voters are significantly more likely to report principled justifications, and vice versa. While the effectiveness of campaigns is disputed in the electoral context, various scholars have claimed that campaigns are more likely to have an impact in direct democratic votes, where voters often have little detailed information and partisan alignments are not always clear and simple (de Vreese Reference de Vreese and de Vreese2007; Hobolt Reference Hobolt2009; LeDuc Reference LeDuc2002). This finding is also in line with a recent study on the effect of elite rhetoric on voters' opinions on the US health care debate (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2017), which finds that elite rhetoric does not necessarily change voters' opinions about healthcare, but it affects how they justify their positions. Thus, voters are likely to adopt elite rhetoric to justify their own policy decisions and preferences.

This study contributes to the literature in three main ways. First, while previous studies measuring moral attitudes at the individual voter level use either experimental manipulations (Leidner, Kardos, and Castano Reference Leidner, Kardos and Castano2017) or closed-ended survey questions (Ryan Reference Ryan2014; Ryan Reference Ryan2017; Skitka Reference Skitka2010), this study adds a different perspective by analysing open-ended survey questions. Secondly, it adds evidence from the European context to the mainly US-based discussion on moral attitudes. Finally, we examine the antecedents of principled reasoning and try to determine when citizens form principled attitudes in the first place. Even though we do not directly measure moral conviction, these findings might nevertheless be interesting for scholars of morality in political attitudes, which have more often focused on the consequences of moral attitudes.

The study suffers from at least two limitations. First, the analysis uses justifications reported post hoc, which do not necessarily represent respondents' ‘true’ underlying motives, thus the possibility of post hoc rationalization cannot be excluded. However, as pointed out previously, we nevertheless find these justifications highly relevant, as these are the arguments that voters will use in any public debate or private discussion about the ballot issues. In other words, these are the arguments constituting the issue-related deliberation. Furthermore, even if not every respondent is aware of their unconscious motives all the time, we assume most people will answer the question honestly most of the time. A related concern is that social desirability might bias the types of answers about voters' justifications. In particular, we suspect that respondents have reservations about openly mentioning identity-related arguments containing xenophobic, patriotic or nationalistic arguments. These types of motives might well be more frequent than admitted in the survey answers. With regard to principled versus pragmatic answers, however, we do not have clear expectations about their general social desirability; we would expect this to depend on the specific issue and the respondent's characteristics. For example, social justice and fairness concerns might be more desirable among left-wing voters than among conservatives, as might human rights concerns. Unfortunately, we do not have the means to test for social desirability effects here.

A second limitation is that, as usual with observational data, the analysis cannot determine the direction of causal effects beyond all doubt. For example, do we find moral reasons for issues that are more relevant to us, or do convincing moral arguments make an issue more important to us? This would be particularly interesting to find out for the framing of the campaign arguments: does exposure to certain frames evoke moral or pragmatic reasoning in direct democratic campaigns, as some previous research suggests (Domke, Shah and Wackman Reference Domke, Shah and Wackman1998; Leidner, Kardos and Castano Reference Leidner, Kardos and Castano2017), or does the campaign simply take up and reproduce the arguments that dominate public discussions? Additional tests make the latter probability seem less likely. Future experimental studies will have to determine this question, however.

What implications can be drawn from these findings? As reported above, moralized attitudes have been found to trigger negative consequences for democracy, such as a decreasing willingness to compromise and deliberate, but also positive consequences such as increased participation. On the other end of the spectrum, pragmatic reasoning is often assumed to be more rational and to rely more on facts and information, and has indeed been found to trigger fewer strong emotions – but again, this can have both positive and negative implications for democracy. Citizens who strongly and passionately argue for the common good, and for fairness and equal treatment, are indeed desirable. In fact, most deliberative theorists would judge principled arguments referring to a universal common good as more valuable than pragmatic arguments referring to narrow-scope material consequences or efficient procedures.

This study's findings, however, indicate that whether an issue is discussed in principled/value-based or pragmatic/consequentialist terms is variable and can potentially be influenced by campaigning. Furthermore, it depends, at least to a certain extent, on the subjective perception of the individual voter. This is good news insofar as there do not seem to be issues on which no compromise can be achieved simply because they are identitarian, social-cultural or moral in nature. For example, the current debate on immigration in many European countries and in the United States is led at times in principled terms, stressing unalienable, human rights, the principle of equal opportunity or equal treatment before the law. At other times it is led in pragmatic terms, referring to consequences for domestic labour markets, and discussing proposals such as merit-based visa systems, additional protective measures for domestic businesses or immigration caps of varying numbers. Another example is the welfare debate in the United States, which transformed from a pragmatic-economic debate on state versus market forces to a debate about deservingness and racial identity.

As always, these findings, while answering some questions, introduce a whole range of new questions. How does the link between framing, attitude strength and reasoning type work exactly? What is the potential of principled versus pragmatic framing, and what are the limits? Can ‘contentious’ issues be framed in pragmatic terms in order to foster the possibility of political compromise? Which pragmatic arguments and which principles are effective with different issues? Do some actors purposely moralize policy issues in order to strengthen their supporters' opinions on them? While studies using experimental manipulations are ideal for exploring the psychological mechanisms driving political reasoning, we think direct democratic campaigns offer an interesting and fruitful setting to further study the effect of campaigns, elite frames, and principled versus pragmatic public opinion.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QICYLQ and appendices at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000218.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Denise Traber, Hanspeter Kriesi, Silja Häusermann, Davide Morisi and the participants of the Political Knowledge Workshop in Vienna, as well as the participants of the Publication Seminar at the University of Zurich's Political Science Department for their valuable comments and support. In addition, I thank Mathias Birrer and Lela Chakhaia for their invaluable help with data coding and their many inputs.