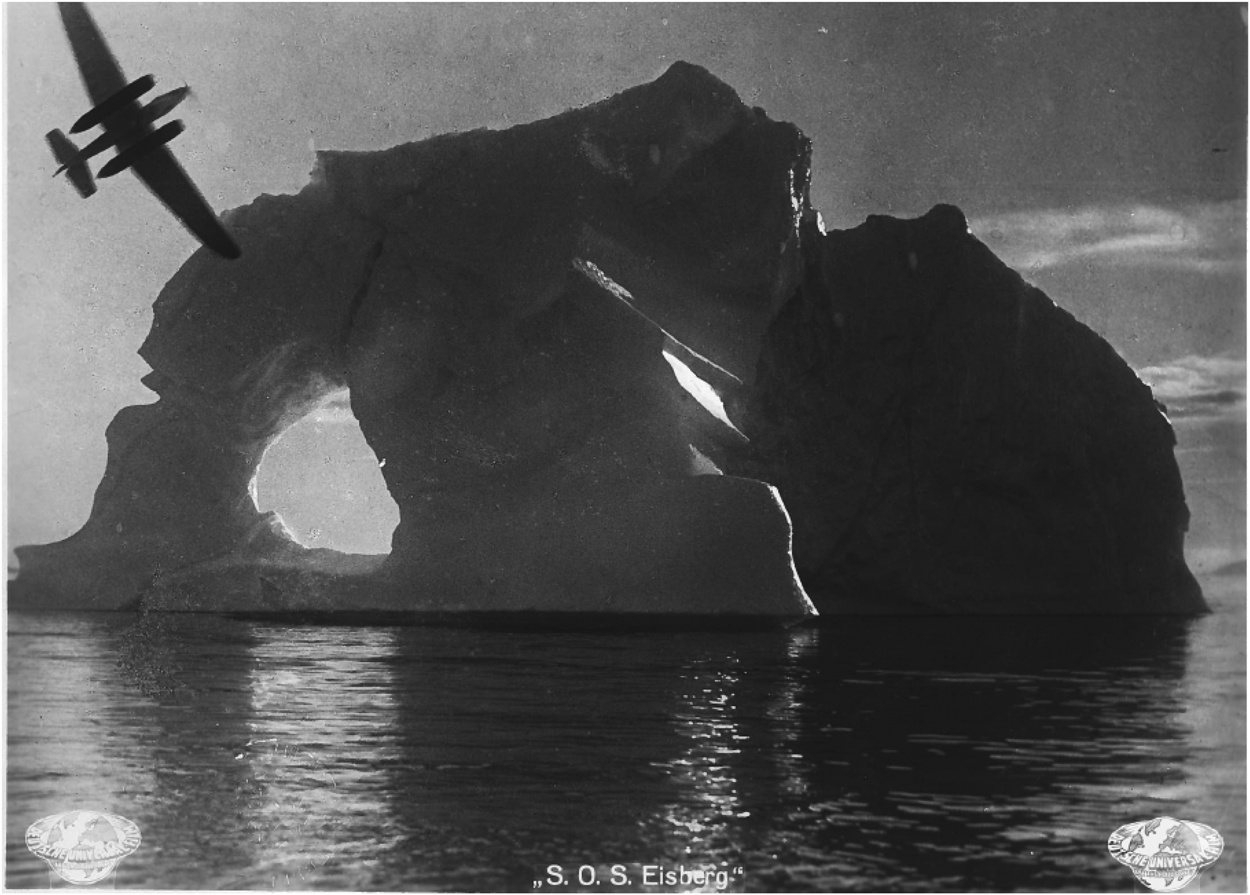

In 1932–1933, Universal Pictures produced two distinct versions of the same film for German and American audiences— S.O.S. Eisberg and Iceberg, respectively—because Universal thought the German version would not cross over. In both versions of the film, the hero repeatedly jumps into the icy waters to save his trapped comrades, which might be the best metaphor for moviemaking itself: a leap into the frozen waters of the financially dangerous unknown, hoping to reach land. While the German version became an “event film” and proved a box office success, the English-language version bombed in the United States.Footnote 1 In the 1920s, Universal struggled to bridge cultural and linguistic borders, as sort of a jump into the icy waters of cultural translations and audience expectations that, more often than not, failed to bring the expected revenues. By examining Universal's struggles, we ask why this transatlantic crossing proved so difficult.

Figure 1. S.O.S. Eisberg with Plane, Deutsche Universal-Film AG, 1933, advertising poster.

Source: USC Cinematic Arts Library.

Scholars of “irresistible” U.S. cultural hegemony in the twentieth century and economic historians who explain Hollywood dominance through audience-winning big-budget steamrollers have tended not to listen to German film scholars, who have long known that American films were rarely among the most popular films in Germany until the 1970s.Footnote 2 Film historian Thomas Saunders stresses that Germany's film industry reasserted itself against Hollywood only after the advent of sound and continuing anxieties about American film that stimulated protectionism and censorship (political risk). Indeed, after the fall of European empires, new nation-building efforts across Europe heightened attention to local art, culture, and language; for Germany specifically, the loss of the war made preserving national prestige and culture a crucial issue. However, we argue that even prior to sound pictures, American films were resistible because Germans favored different genres and their own local stars; they preferred more familiar reference points and had different versions of symbolicity, that is, how a movie is embedded into existing cognitive categories and expectations of audiences (cultural risk).Footnote 3 Most American films failed to dislodge German films in popularity even when the best American films could play on the German market.

Based on newly utilized archival materials of Paul Kohner, who led Universal's European strategy and later became a leading Hollywood talent agent, and blending international business and media/film studies concepts, we offer a case study of difficult localization by Universal Pictures in Germany after World War I. As implied by its corporate slogan “making Universal Films for the Universe,” Laemmle began with a global strategy for film aided by the alleged universalism of silent films yet during the late 1920s moved to a strategy of offering films cut to German tastes. Much literature focuses on why Hollywood as an industry succeeded, yet less is concerned with how individual firms adapted to local markets.Footnote 4 Universal eventually succeeded by financing and producing three very popular “German” films—Der Rebell (1932), S.O.S. Eisberg (1933), and Der Verlorene Sohn/The Prodigal Son (1934)—starring leading German actor-directors such as Luis Trenker and Leni Riefenstahl. However, the Nazis forced Universal out of Germany, labeling it a “Jewish” firm.

Of all the Hollywood studios, Universal had considerable advantages. Carl Laemmle was a German immigrant who maintained close ties to Germany. In 1932 he even led fundraising efforts to bring Germany's Olympic team to Los Angeles. Universal City, a company town outside of Los Angeles, was a harbor for German immigrants prior to 1933 and then a haven for exiled Germans after 1933. Universal City illustrated the complex transatlantic, translocal circulation of ideas, images, and talent that made a dry Los Angeles hill “Hollywoodland.”Footnote 5 Universal could have produced or dubbed German-language films from Los Angeles, yet instead it located its European subsidiary, Deutsche Universal-Film AG, in Berlin to have a close feel for the market. Berlin was also the portal to other central and eastern European markets because many German studios had extensive distribution networks and closer cultural affinities to those countries. Despite these advantages, Universal's forays into Germany proved contentious.Footnote 6

A Concept of Cultural Risk

As used here, “cultural risk” highlights the unknown discount, the wildly hazardous, fundamentally uncertain project of making successful films for the home market and then, in particular, crossing borders. Hollywood, it has been argued, proved a juggernaut after World War I because of its overwhelming economic advantages. According to Gerben Bakker, Europe's film industry failed to keep up with the American studios’ three-pronged investment in “scale and scope” (to use Alfred Chandler's phrase) or “escalation of quality” that permitted deep sunk costs to be monetized into feature-length films with high production value, with studio brands controlling efficient distribution networks.Footnote 7 Peter Miskell recently argued that Hollywood's extensive international distribution networks should not be neglected; Hollywood was just one source of global film content.Footnote 8 Finally, the sheer size and level of disposable income of the U.S. market helped to earn back the costs of big-budget features not available to fragmented, smaller, and poorer European markets disrupted by war, thus helping to offset any cultural discount involved. In spite of these advantages, the German film industry was widely regarded as one of Hollywood's main challengers.

The concept of cultural risk bundles together two concepts from two disciplines, cultural discount (media studies) and cultural or psychic distance (international business), to highlight the profound riskiness of crossing borders. Media scholars use the idea of cultural discount to assess the reduction in value when a cultural product crosses a border because every “national reception culture” is different.Footnote 9 It is the media studies equivalent of the liability of foreignness in international business literature, but it has the advantage of including a microeconomic implication.Footnote 10 Certain genres such as verbally oriented comedies or romances suffer from a larger cultural discount than action movies, physical comedies, thrillers, or science-fiction films, so their performance abroad is less predictable and less related to their original success in their home market.Footnote 11 Unlike products with functions such as an automobile or coffeemaker, film content is a complex artistic, semiotic product filled with interrelated meanings (symbolicity) that must appeal to the mental preferences of another culture's audience to create a market for a particular film. Film studios are “more akin to R&D centres than production factories” because of the necessity to innovate new products that attract audiences to the theater, leaving aside their profitability after costs.Footnote 12 Although production methods might be standardized to lower costs (supply), individual films have to offer moviegoers novel experiences or they stop going to the movies (demand). As with many cultural industries, financially successful products are often one-offs; popular franchises or star actors help mitigate this one-off risk.

Cultural discount has a microeconomic dimension. A large home market helps to monetize larger budgets through larger domestic sales within a given cultural sphere. Assuming the cultural discount rate is equal for films between two hypothetical markets and exchange is fully open, all things being equal, the studios with the larger home market can generate greater production quality for its films plus lower the marginal cost of exporting. Smaller national competitors thus have difficulty matching scale, quality, and cost of films from larger markets. And this idea presumes that the cultural discount and ease of exchange is the same across countries, which it is not. Domestic market size is also related to the fact that film is a joint consumption product that does not diminish in value with use, unlike a physical product; a successful film even creates a multiplier effect as a collective event experience.Footnote 13

The concept of cultural risk also highlights the psychic distance between the home studio and cross-national audiences for its film product. Psychic distance refers to how local individual managers perceive the difference of another culture, or their ability to read themselves into it, while cultural distance stresses how collective values or belief systems differ across countries more generally. Both concepts imply that films from some countries are likely to be more easily accessible to audiences in countries that are culturally more proximate.Footnote 14

However, larger budgets and effective distribution networks still do not ensure popularity in the eyes of the moviegoing public, who view films in their own interpretive act of local reception; secured screentime does not mean audiences come to the theater. Film's “semantic malleability” often leads to culturally specific meanings (and misunderstandings) for the same media product. In at least five nations (Germany, France, India, Japan, and Mexico), cultural backlash created vibrant local alternatives. In the 1940s, Kohner noted that American studios had to build their own theaters and production studios in Mexico to compete with Mexican studios, as “Mexicans prefer the Mexican made pictures,” and that a great percentage of the population could neither understand English nor even read Spanish subtitles.Footnote 15 Today, by contrast, Hollywood film is so dominant that it defines the “language of film” such that, at least among younger viewers, smaller national film markets suffer a cultural discount at home for domestic films. Some analysts argue that Hollywood films today, unlike classic Hollywood of the 1920s to the 1950s that projected an American dreamscape or “way of life,” are increasingly denationalized, deterritorialized, and delocalized, such as with science-fiction stories, so the industry has in a sense turned back to universalization.Footnote 16

Finally, in the immortal words of screenwriter William Goldman, “nobody knows anything” about making successful movies even in one culture. Extreme risk, skewed winner-take-all results, “wild behavior” were/are the only certainty; “hits” are few and far between (“variance” is high); the audience must first discover the film—and as a result, making a film without knowing the audience is a “frightening business.”Footnote 17 Laemmle voiced a similar sentiment at a 1930 Universal sales convention; Laemmle offered anyone in the company a salary of a hundred thousand dollars a year if they could prove themselves 80 percent right. Following up: “I don't care what you want or what I want, it is what the public wants that counts, because in the end they have to pay and they have the say. . . . Nobody knows.”Footnote 18

Cultural risk might be subsumed under cultural discount, but the results are not predictable, the “distance” not measurable. Both concepts of cultural discount and cultural distance appear to be more or less fixed, perhaps predictable, as if adjusting for distance by selecting the right golf club. “Market risk” might be used, but the market here is for a fundamentally cultural product that has to create a market for individual films across cultural borders. There might be a market for movies, but not for a film. In the early to mid-1920s, Universal tried to export American-made films to Germany and import German films to America, with little success. Audience preferences and expectations were too different.

Laemmle's Liabilities, 1917–1924

Management scholars have recently pointed out that foreignness is not just a liability but, depending on local contexts, timing, and shifting perceptions, also potentially an asset.Footnote 19 In Laemmle's case, his hybrid German-American-Jewish identity caused great problems precisely because he had two homes that both claimed and unclaimed him at different times. Laemmle was born in Laupheim, a small town south of Ulm in southwest Germany, to which he remained emotionally attached; Universal City even had a replica of his favorite Laupheim restaurant in its European set.Footnote 20 He immigrated to the United States in 1884 and became a naturalized citizen in 1889. Historian Neil Gabler argues that the immigrant founders of Hollywood studios tried to transcend their immigrant European roots, languages, and Jewishness.Footnote 21 This did not apply to Laemmle, who was a full generation older than the other studio heads and maintained an open identification with his home country and Jewish faith. He was culturally bifocal and tried to act as a transatlantic bridge. Laemmle frequently wrote for the entertainment press on the two continents (Universal Weekly, Saturday Evening Post, Film-Kurier, Lichtbild-Bühne) and in the 1920s made direct radio addresses in English and in German. A central part of his marketing approach was portraying himself as an impresario of motion pictures, with “Carl Laemmle Presents” on his movie posters, on theater signs, and at the beginning of films. This personification made him an easy target.

Laemmle's movie career began with regulatory and censorship altercations just as he would face in Germany later. In the United States, as a regional film distributor prior to World War I, Laemmle launched an antitrust campaign against the Edison monopoly on film and film equipment licensing. Contemporaries noted that this campaign pitted many independent immigrant Jewish exhibitors against the Anglo-Saxon Edison. One cartoon portrayed Laemmle as a poor Jewish peddler on a donkey pushing junk films on an undiscerning public. Independent distributors won in 1915 when the Supreme Court ruled the Edison company an illegal trust.Footnote 22

Laemmle then integrated backward into production with the appropriately named Independent Moving Pictures. In 1912, Laemmle with other partners founded the Universal Film Manufacturing Company. In 1915, he moved to Universal City, a “company city” entirely owned by Universal: “The Strangest Place on Earth, An entire city built and used exclusively for the making of moving pictures.”Footnote 23 Universal City featured live shows and studio tours since its inception. Laemmle later advertised to Germans that Universal City was a “German Hollywood.”Footnote 24 For a time, it was the largest production studio in Hollywood, a first mover in economies of scale, yet he ran Universal as a family business, often referred to as “Laemmle's Faemmle.”Footnote 25 One early find, for instance, was Wilhelm Weiller (William Wyler), his nephew and one of the more decorated directors in Hollywood history (Wuthering Heights [1939], Roman Holiday [1953], Ben-Hur [1959]).

Laemmle's “cultural bifocalism” should have made him an ideal interlocutor between American and German markets.Footnote 26 Already in 1911 Laemmle had opened a sales office in Berlin. His annual visits to Laupheim turned into business trips and talent searches. However, the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915, the discovery of the Zimmerman Telegram proposing an alliance of Germany and Mexico in 1917, and the declaration of war in April 1917 resulted in a wave of anti-German, anti-hyphenated-American hysteria that branded both Laemmle and Universal as pro-German. Universal and other film studios began producing propaganda films out of “practical patriotism” to prove themselves war-essential.Footnote 27 Universal produced three of the best-known titles of anti-German propaganda—strictly speaking, anti-Kaiser and anti-militarist films (an important distinction for Laemmle): The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin (1918), The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918), and The Heart of Humanity (1919).Footnote 28 In Heart of Humanity, the Prussian soldier (played by Erich von Stroheim) famously threw a baby out a window because it annoyed him while he attempted to rape an American Red Cross nurse. Never at a loss for a chance at publicity, Laemmle named von Stroheim as “the man you love to hate.” After the war's end, news that a German-born movie producer had made the harshest propaganda films shocked many Germans. Right-wing German opinion never forgave Laemmle, considering him a Jewish traitor to the homeland. Laemmle did not go back to Laupheim in 1919 for fear of being assassinated.Footnote 29

In spite of this poor beginning, Universal achieved a strong surge of exports into Germany based on a back catalog of low-budget films and cheap westerns. One German distributor accused Universal of being a “factory of mere thrills,” but it constituted 50 percent of the total foreign imports of feature-length films in Germany through 1923 (see below Table 2).Footnote 30 Universal put out a run of popular serials (Hoot Gibson westerns directed by John Ford) and silent picture landmarks: Blind Husbands (1919), Foolish Wives (1922), Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), and Phantom of the Opera (1925). Foolish Wives, Universal's first million-dollar movie, was a tremendous box office success in America in spite of its censorship controversies. However, it flopped in Germany because of director von Stroheim's villainous reputation and the public perception that its portrayal of European society was superficial.Footnote 31

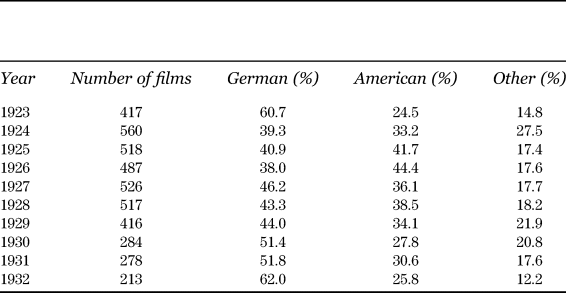

Table 1 Market Share of Feature-Length Films, 1923–1932

Source: Adapted from Ursula M. Saekel, Der US-Film in der Weimarer Republik—ein Medium der “Amerikanisierung”?: Deutsche Filmwirtschaft, Kulturpolitik und mediale Globalisierung im Fokus transatlantischer Interessen (Paderborn, 2011), 255, Table 52.

Table 2 Number of American Films Imported to Germany, Selected Companies, 1920–1933

Source: Adapted from Ursula M. Saekel, Der US-Film in der Weimarer Republik—ein Medium der “Amerikanisierung”?: Deutsche Filmwirtschaft, Kulturpolitik und mediale Globalisierung im Fokus transatlantischer Interessen (Paderborn, 2011), 255–56, Table 53; and Markus Spieker, Hollywood unterm Hakenkreuz (Trier, 1999), 337, Table 1, for overall 1928–1933 figures.

Note: Individual company figures not available from 1928 through 1932.

In 1924, German films lost 20 percent of their domestic market share to Hollywood. In 1926 American feature films reached their high point of 44 percent market share. American films were generally shown interspersed with German films, but other foreign films maintained a solid market share. Quotas blocked more American films. In 1923 Famous Players-Lasky, for instance, could show only twenty-one of their sixty-two films produced in 1923; Universal could show only ten of its forty-nine feature-length films. As early as November 1920, Laemmle sent some staff to Germany to begin production locally of “tales of German life.”Footnote 32 As with many import restrictions, quotas encouraged local production. Kohner later noted,

It is important to know that production of German-made pictures which was started on the continent as a quota measure and was vigorously fought at first by American companies, eventually developed into a major business for these subsidiaries of American companies, with many of them producing far more pictures than was mentioned for their quota—simply for the reason that they saw that they were in a better position to sell their American product by having an important number of German talking pictures on their program.Footnote 33

If they were fortunate, those local productions could be distributed elsewhere in the world but also, it was hoped, back to the United States too.

Hollywood studios tried to sell German films after 1924 to the U.S. market when many purchased hundreds of inexpensive German films, dubbed a “German invasion,” but these generally failed.Footnote 34 For instance, in late 1924 Laemmle had Kohner test-screen Friedrich Murnau's The Last Laugh (1924), one of the gems of Weimar cinema. The Wichita theater owner replied, “The public wants hokum not art.” Kohner reported that the theater owner “believes that the producers give the audience too much credit for intelligence. This is why he believes that LAST LAUGH will not go over in this town.”Footnote 35 In Vancouver, some theater owners thought there remained too much “anti-German sentiment in Canada” for the film to be successful; the Toronto theater exhibitor thought the “picture is very fine” but would not “recommend it for any of his theatres” as “it would not go over with the audience.” Kohner summarized the dominant sentiment: “Well this picture only shows the high regard that the Europeans have for a uniform—I do not believe Americans would understand it.”Footnote 36 It was not much of a German film invasion.

In Germany, the rise of U.S. film's market share led to a fear of the Amerikanisierung of German popular culture along with the potential takeovers (Überfremdung) of German industrial companies. Film became a cultural battleground. The German government in 1925 moved to a “one-for-one” compensation (Kontingent) system. This law meant that distributors could receive the license to show a foreign film only if it showed a German film of the same length. It capped the German market for foreign films at 50 percent, but it meant far less in practice for American studios because of other foreign competitors (Table 1).

The contingent quota system encouraged joint ventures. In October 1925, Laemmle had already made headlines with rumors that he had purchased the film company Bruckmann; that company denied it but did admit that it intended to distribute Universal's best films to Germany. Other Hollywood studios began pairing up with German studios or distributors, but these looked like emerging takeovers (political risk).

The UFA Setback, 1925–1928

In the mid-1920s, the German economy suffered a credit crunch. The flagship firm of the German film industry, the Universum Film AG (UFA), in which the Deutsche Bank held a controlling 30 percent stake, found itself near bankruptcy. It suffered a liquidity crisis because of a series of overbudget big feature films. Erich Pommer, UFA's production chief, also thought in terms of the “quality race” in production and promotion, but UFA needed access to capital and international film markets for its prestige films.Footnote 37

UFA found two suitors for a potential joint distribution venture: Universal and a consortium of Metro-Goldwyn and Famous Players-Lasky (Paramount was its distribution arm). UFA's movie theater network would place an American studio at the forefront of the German and central European markets, and UFA would gain an influx of capital. UFA also targeted the lucrative American market, where it had failed “to attain a regular and lasting market . . . aside from some exceptions.”Footnote 38

Famous Players-Lasky had approached UFA in mid-1925, but UFA executives felt that the Americans did not treat UFA as an equal.Footnote 39 By late 1925, however, UFA and Deutsche Bank executives felt they had little choice because of the firm's rising debt. Both Metropolis (1927) and Faust (1926) were still in production.Footnote 40 Fritz Lang's Die Nibelungen (1924–1925) was an outstanding success in Germany, where its premiere was attended by Chancellor Gustav Stresemann, who hoped the epic would unite Germans; Lang and his cowriter wife had laid a wreath at the grave of Frederick the Great earlier that day.Footnote 41 However, the film found little little favor with American audiences and thus did not generate the desired revenues.Footnote 42 Later, the science-fiction film classic Metropolis, which was among the most popular films of 1927 in Germany, was butchered into an incoherent mess to fit American expectations and failed there. The national reception of these major films demonstrated the chasm in audience expectations and nearly cost UFA its existence.

In October 1925, UFA and the Deutsche Bank opened secret negotiations with Universal; Laemmle handled the negotiations himself. In late November 1925, Universal released a press statement that it would loan UFA RM 15 million (approximately $3.6 million) in exchange for access to UFA's theater network. This announcement soon proved to be Laemmle's first misstep.

News of Laemmle's negotiations sparked Famous Players-Lasky (Paramount) and Metro-Goldwyn to reenter negotiations—as much to access the German market as to head off Universal. In December 1925 negotiations climaxed with an all-night meeting with UFA, Universal, and Famous Players-Lasky (Paramount)/Metro-Goldwyn. Laemmle negotiated personally, while Famous Players/Metro-Goldwyn sent their representatives. In a dramatic reversal, UFA signed a new contract with Famous Players-Lasky/Metro-Goldwyn on December 29 and another with Universal on December 30 that compensated Laemmle for breaking his November agreement.

In the new agreement, Famous Players-Lasky/Metro-Goldwyn extended UFA a ten-year loan of $4 million (RM 16.8 million) at 7.5 percent interest with UFA's headquarters on Potsdamer Platz as collateral, which proved problematic two years later. The new partners founded a joint distribution organization called Parufamet in which UFA held 50 percent of the shares, while Paramount and Metro-Goldwyn each held 25 percent. Each had to distribute at least twenty (but no more than thirty) of their top films exclusively through Parufamet, subject to quota regulations. UFA agreed to reserve 75 percent of its showings, “equitably distributed over the year” and in its “most suitable” theaters, for Parufamet films. Parufamet could expand its theater network with the ownership distributed according to the proportion of ownership rights of the joint venture. In return, Famous Players-Lasky and Metro-Goldwyn promised to finance and produce jointly one or two big-budget (at least $400,000) features and promote at least five UFA-produced films annually in the United States in a “first-run theater” “suitable for the American market.”Footnote 43 This last clause became notorious, since any film could be deemed as not meeting American taste.

Why the reversal? Confidentially, UFA executives felt that “these firms would be essentially much more favorable [partners] in comparison with the [November 21, 1925] contract with Universal in regards the quality of their film production, their purchasing power, and the power of their organizations that stands well above that of other groups.” UFA and the Deutsche Bank shifted their allegiance largely because of Metro-Goldwyn's reputation for quality and access to “first-run theaters,” with prominent movie palaces in large American cities, especially New York. UFA stressed to the German public that since there was no exchange of equity it was not a takeover, and the name of Parufamet was designed to have a neutral effect.Footnote 44 This was in contrast to the Universal contract that required that both “Carl Laemmle Presents” and the UFA logo be the same size on its movie posters. UFA's representative in New York also thought Universal's offerings were “at an essentially lower level.”Footnote 45

The UFA setback exposed Universal's weakness in the mid-1920s as a studio with an aging patriarch whose reputation was as a purveyor of B-level genre movies rather than “A-list” quality movies. Indeed, in late 1924 Laemmle had sent Kohner on a cross-country trip to meet with Universal's largely smaller, independent theater clients, but according to Kohner, the Universal “trade mark is considered by the public as a trade mark of cheap pictures.” Kohner reported that Universal's pictures were playing in the “small houses, the dumps, and the ‘shooting galleries,’ some of them veritable stables, hardly deserving the name ‘moving picture theater.’ . . . [We hear from our salesmen,] ‘We cannot sell the big house, because he is playing Famous-Players, First National, or Metro-Goldwyn pictures.’ And that usually ends the argument.”Footnote 46 It ended the argument for UFA too.

In January 1926, UFA management admitted that Laemmle had “not behaved entirely loyally.” They faulted Laemmle with “strong ethical reproaches” for leaking details of the deal prior to closing, reneging on prior promises, and, they claimed, trying to hire away one of UFA's executives for $50,000 per year at the negotiating table in the presence of the other UFA/Deutsche Bank executives. UFA negotiators faulted Laemmle's “blunt brutality,” his threats to walk out of the deal, and his intentions for a full takeover: “Lämmle merely agreed to the entire contract through this maneuver to incorporate his production in our huge chain of theaters. . . . [A]fter we got to know his company, it is perhaps appropriate to have as little to do with him as possible. . . . With him you can hardly negotiate because he hardly hears (when he doesn't want he can't hear at all), sees badly too, and moreover strongly adheres to his forefathers’ school of thought who were active in Laupheim's cattle trade.” This last anti-Semitic comment referred to Laemmle's small-town, Jewish background. According to one Deutsche Bank executive, they were dealing with a group of “film riff-raffs” (Filmgesindel) who wanted to incorporate UFA into an “American trust.”Footnote 47 As compensation for breaking the November 1925 agreement, UFA promised to distribute at least ten Universal films through its Decla-Verleih; Universal would also receive $275,000 in each of the next three years.Footnote 48

Laemmle's very public announcement had harmed UFA's reputation in German public opinion. The German press labeled the Parufamet deal a “UFA-Diktat,” a phrase echoing that used for the despised Versailles Treaty. In its press releases, UFA struggled to portray the agreement as a partnership instead of a capitulation. UFA did lose partial control over its film program, but most importantly it did not solve UFA's homegrown financial difficulties because American films “suffered a fiasco” at the box office.Footnote 49 By early 1927, UFA neared bankruptcy once again, until the right-wing nationalist media mogul and politician Alfred Hugenberg took it over. Hugenberg sought to amend, if not void, the Parufamet agreement. Hugenberg redirected UFA films toward celebrating German nationalism, consolidating the industry, and becoming more like a Hollywood studio where producers controlled the talent.Footnote 50

For Universal, the Parufamet deal was a major setback. Laemmle was forced to rethink his film strategy.

Localization, 1928–1930: Deutsche Universal-Film

After 1928, Universal refocused itself by offering more creative, prestige productions interspersed within its more familiar slew of western and genre films that had earned it the reputation as the Woolworths of American film studios. Universal recognized its weakness in distribution. After 1928 it began incorporating some three hundred–plus smaller provincial theaters but was forced to resell them during the Depression since they all needed expensive conversion to sound and Universal could no longer afford it. To his salesmen, Laemmle stressed in 1930, “Go to the best houses first and the dumps last. . . . We have to sell to the very best theatres in America.”Footnote 51

Two key figures emerged. Carl Laemmle Jr., who became chief of production in 1928, and Paul Kohner, head of production in Europe. Laemmle Jr. advocated for more high-prestige, big-budget productions, especially musicals that were extremely popular at home and could cross over more readily to international markets. This upmarket shift resulted in some landmark films: The Man Who Laughs (1928, produced by Kohner), the musicals Broadway (1929), Showboat (1929, 1936), and (in technicolor) King of Jazz (1930); two dramas directed by William Wyler, A House Divided (1931) and The Good Fairy (1935); with the biggest prize going to All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). Artistically, this phase of Universal films has found critical reevaluation, but these films undermined the studio's finances.Footnote 52 Universal also went on a creative run of classic horror thrillers including Frankenstein (1931), Dracula (1931), The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), and the Black Cat (1934).

Kohner moved to Berlin in 1928 to develop new European talent and content. In 1930, he became supervisor of foreign production at Deutsche Universal-Film in Berlin, a new subsidiary. Kohner advocated making films more European in their taste. Under Kohner's initiative and production, Deutsche Universal backed three big-budget German films that achieved box office success and critical acclaim in Germany—but not in the United States.

Figure 2. Carl Laemmle Jr., Carl Laemmle Sr., and Paul Kohner, ca. 1928

Source: “Filmdeutschland und Filmamerika von Carl Laemmle, Präsident der Universal Pictures Corporation,” Illustrierte Film-Zeitung: Wochenschrift des Berliner Tageblatts, no. 42, 1 Nov. 1928, file 4.3-88/14-1.9, Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin.

Universal tried to bring European talent back to Hollywood and blend European and American sensibilities: for instance, with director Paul Leni's Cat and the Canary (1927). While Laemmle praised the film for its “universal appeal,” it found some success in the United States but not in Germany. At Universal City, Leni could speak only German but expressed admiration for “American dash and enterprise—qualities which we lack in Europe because we are too slow and too poor.”Footnote 53 Leni's subsequent The Man Who Laughs, starring Mary Philbin and German star Conrad Veidt (Major Strasser in Casablanca), bombed. In a blistering letter, Laemmle reminded its producer, Kohner,

I suppose you know that the MAN WHO LAUGHS is a terrific failure in this country. We have a terrible time selling it. I'm sure our losses will be in the U.S. not much less than a half million dollars. I hope that we can make this up in foreign countries. I'm not blaming you for the losses on the MAN WHO LAUGHS but I'm simply writing you about it because of your opinion that the picture was far ahead of the HUNCHBACK or any other picture that Universal ever made. I'm going to think a long while before I make another big costume picture.Footnote 54

Laemmle made it his “guiding principle to fuse European culture and literature with American film techniques” to create a universal film language, but this proved fiendishly difficult.Footnote 55 Artistically it worked to some extent, as Leni brought Expressionist camera angles and new forms of light and shadow to the “mystery melodrama” that would permeate Universal horror films and American film noir—so a creative success (the premise of a man with a frozen smile inspired the Batman character of the Joker), but not necessarily a box office success.

In Germany, after the UFA debacle, Laemmle Sr. first set up his own distribution firm, called Matador-Film-Verleih, as a full subsidiary of Universal but did not call attention to its American origins. The usual “Carl Laemmle Presents” was replaced by the Matador logo for German films. Both the Matador logo and Universal Pictures logo were of equal size only for imported American films. Universal hired German managers to distribute both American and local German productions. Because of the matching principle (Kontingentierung), in Matador's first year it distributed thirteen German films and thirteen American firms; the German films starred popular German actors and directors. American-made films by German directors or starring German actors were highlighted in its advertising. In May 1928, Matador became Deutsche Universal-Film AG under general director Max Friedman (a nephew-in-law of Laemmle), and he reintroduced the famous Universal Globe as its logo. In 1928, Laemmle admitted in the Film-Kurier that he “had had already many good and bad experiences in Germany” due to the origins of his firm.Footnote 56

Germany altered its quota system again in 1928 and 1929 based on the prior year's number of feature films sold. Such quotas helped reduce the number of feature-length American films shown from 199 in 1928 to 142 in 1929, but part of this decline can also be explained by the transition to sound. Deutsche Universal chose not to rely on its American-made films but instead to distribute mostly German-made films with well-known German stars. For instance, of 100 films chosen by Deutsche Universal to distribute across Europe in 1928, just 14 were American feature-length films, including those made by emigré Germans. This example tends to confirm the importance of distributing films from other nations.Footnote 57

Sound transformed the industry, as native voices, language, accents, idioms, inflections, and subtle local meanings mattered for film reception in ways they did not in silent films. In July 1928, Kohner wrote to Laemmle Sr.: “IMPORTANT: The first company presenting the speaking and sound pictures in Europe will, on account of the novelty, receive a tremendous amount of publicity. I think we are the logical firm to do this. . . . We could be the first one to take advantage of the new market.”Footnote 58

Universal committed itself to localizing production in Berlin. Paramount, by contrast, unified its European production just outside Paris to create multiple-language versions of its films and rented out its facilities to other film studios. Metro-Goldwyn imported European talent to Hollywood to create multiple-language versions from Culver City. Universal filmed Showboat, Broadway, and King of Jazz competely in German at Universal City, but those films were initially shown in Germany as silent versions because of different technical standards and patent right difficulties for sound equipment. For King of Jazz, Kohner arranged a different master of ceremonies for introductions for Germany, France, Italy, and Japan so that the film seemed “made by and for” each native country. Kohner also had the bright idea to film different versions of the same story using different actors on the same sets, most famously with the Spanish-language Dracula (1931). In Germany, its film productions utilized the “Universal model” that immediately refilmed the same story in Berlin using German actors rather than synchronizing them after the fact. After 1930, Deutsche Universal greenlighted original screenplays using German actors and directors. Universal made a full commitment to bring “American technical skills to German art,” as Laemmle promised.Footnote 59

Symbolicity in the German Film Market, 1920–1933

As shown by the examples mentioned above of films that worked in one country but failed in the other, it proved difficult for Universal, and other American studios, to make films for the German market. Why? The salient barriers were political (quotas and censorship issues) and economic (relative poverty and upheaval, income stratification, and urban versus rural differences) but mostly cultural (rhetorical, referential, linguistic distances, and differing symbolicity). Simply stated, Germans favored different genres, tropes, and music and preferred their own stars. These distances amounted to an immense cultural risk, a mayhem of missed translations found in filmgoers’ own minds.

Politics. Quotas were made stricter to protect Germany's domestic industry while it made the technical transition to sound. The key difference after 1929 was that the Reich Import-Export Office acted as a sort of “film czar” that could rule on the exact number of films to be imported, sometimes based on the number of German films exported and sometimes based on the quality of individual films. This arbitrariness heightened uncertainty. American lobbyists argued that it was governments who restricted films against the public's desires, but this was wishful thinking. Another Depression-era stipulation of July 1932 required dubbed films be produced at German studios to boost employment. The Depression discouraged direct investment and imports, and depressed demand.Footnote 60

Table 2 shows three distinct periods that correspond to German political-economic upheavals: 1919 to 1923, 1924 to 1929, and 1929 to 1933. American market share fell consistently after 1926 (Table 1) with shifts only in the relative balance among the major studios (Table 2). The Parufamet contract allowed Metro-Goldwyn and Paramount figures to outpace those of Universal. American imported feature-length films dropped from 216 in 1926 to just 142 as the Depression and sound pictures began, and then to just 55 by 1932; they never really recovered. After 1933, imports declined from 64 films in 1934 to just 20 by 1939.Footnote 61 One of Universal's reactions to this loss in market share in feature-length films was to redouble its efforts in short films, but the number of imported short films dropped from 316 in 1929 to just 29 in 1933, so its relative market share dwindled in meaning.Footnote 62

Censorship played a role across the globe. Censorship can be considered a mixture of political, religious, and cultural “decency” considerations reified into messy and controversial industry standards.Footnote 63 Hence, many films existed in many different versions around the world. To take one example, Italy, Canada, Greece, Trinidad, and Australia banned American gangster films for romanticizing violence.Footnote 64 Age standards for films might drastically reduce the economic size of markets. Censors considered film a commercial product with moral ramifications, not an inviolable artistic statement.

All countries, including many American states and cities, tried to defend their version of national morality from Hollywood. German censorship was designed not only to protect its film industry but also to stop the immoral “danger to the German people” (Volksgefahr). One early 1920 survey found that 250 American films collectively showed ninety-seven murders, fifty-one scenes of adultery, nineteen seductions, thirty-five drunks, and twenty-five prostitutes.Footnote 65 According to the novelist Alfred Döblin, “The ordinary (kleine) man, the ordinary woman knows no literature, no development, no direction. . . . [T]hey want to be moved, excited, horrified, and burst into laughter. . . . [Motion pictures] offer the most amazing and thoroughly dreadful. The quality of the portrayal lies in direct proportion to the amount of created goosebumps.”Footnote 66 In Germany, it was easy to label the creation of “goosebumps” as a form of “Unkultur.”Footnote 67 Universal's many offerings fell squarely into this category.

In Germany, there was an early debate about how the “image” on film was not comparable to the reading of literary “texts,” according to the cultured class. Films were viewed as equivalent to smutty pulp fiction pamphlets, so-called “junk films” (Schundfilme) that lowered morals, especially for children.Footnote 68 One early sociological study found that many young working-class mothers went to the movies with their children.Footnote 69 After the loss of World War I, these fears took on nationalist-moralistic tones of degeneration.

Economic

With the decimation of ordinary German's real incomes after the hyperinflation, the German cinema industry still managed to expand. As Ursula Saekel demonstrates, the German market remained well served by an expansionary wave of cinemas after 1924, particularly those serving small and midsize towns. In 1927 Germany had the largest number of cinemas in Europe but was ranked eighth in cinemas per capita. There was a general trend toward larger, palatial-like “events.” Depressing the entire market, however, was a “pleasure tax” (Lustbarkeitssteuer) of 18 percent on movie tickets. Even going out to the movies was like the theater experience; people dressed up and made it an evening with ancillary activities, particularly since ticket prices were still fairly high relative to income.Footnote 70 Still, Germany had the largest film industry in Europe, with German being de facto a second language and Weimar cinema a creative tone setter with many key German contributors emigrating to Hollywood after 1933.Footnote 71

Cultural

American films generally failed to capture the expectations, preferences, reference points, tropes, genres, and tone that German audiences desired.Footnote 72 This drop in market share has been attributed to quotas or the advent of sound, but one can discern deeper cultural distances prior to the advent of talkies. It was uncommon that American films managed to break into the top ten most popular films shown in Germany before 1939, and their appearances on such lists remained irregular till the late 1960s. Also, securing space on screens did not mean the audience came to see the movie.

Internal memoranda between UFA and the Deutsche Bank provides concrete information on the relative unpopularity of American films—information from theater owners, not snooty cultural critics. Owners complained about a consistent loss in box office receipts “as long as the [Parufamet] contracts continue.”Footnote 73 And UFA offered the best of American silent cinema. The following excerpts represent around twenty pages of mostly complaints:

American films that ran constantly ruined the profits for the month and transformed a profitable business into a losing one. These mediocre American films, of which the worst are the ones delivered by Parufamet, ruin the business not only for the time they run, but also depress the standard of the Central Theater. . . . [W]e are certainly not to blame when the business does not generate any satisfactory profits. (A theater owner in Pforzheim)

The public radically rejects American films. . . . From eleven years of practical experience . . . the audience would rather see German mediocre films rather than films of the American ones of the “super-class.” . . . German actors with whom they have a personal attachment are those that secure a particular core audience. (Breslau)

American films with the exceptions of a few big films are being rejected by the movie audience here. . . . Many times I have observed that steady moviegoers turn around and leave again after viewing the placards and photos. (Gleiwitz)

[Regarding the film Big City Attracts:] Although this film is quite nice, there is an instinctive aversion to the average American film.

[Regarding the film Scarlett Letter:] Lilian Gish is a great artist, no one argues against that. That she is very beautiful, no one would argue against that. However, that one should be bored over an hour long should not be demanded of anyone. Historical material is always a risk in and of itself, in particular when it deals with things that we do not know about or do not understand. Too bad for Lilian Gish.

[Regarding the film Necessary Marriage:] We are not here in New York. With these titillating marriage issues (provided they even were titillating), but we will never get anyone into the movies. (Pforzheim)

Is that an Ufa Theater? It is a stall! Again you have brought us American crap. (Mannheim)Footnote 74

Because of poor box office sales and reception, the Paraufamet contract was renegotiated.

In 1930, the Film-Kurier ran a survey of theater owners regarding the top films released between 1925 and 1930. In terms of screen time, German and American films were shown almost equally, but theater owners thought that two-thirds of the most successful films each year were German, the rest being a mixture of American and other foreign films. Only one or two American films were among the top ten most successful films in each year prior to 1934; three were among the top ten in 1927–1928, including Ben-Hur, which ranked at number one in both 1926 and 1927. American films did best in 1932, occupying five of the top ten places, but three were Josef von Sternberg films, two of which starred Marlene Dietrich (Shanghai Express, Blonde Venus), fresh off her worldwide success with the dual-language Der Blaue Engel/The Blue Angel (1930), also a von Sternberg, joint Paramount-UFA production.Footnote 75 German audiences wanted to see appealing German stars, one of the keys to box office success since Laemmle had helped introduce the star system.

While the tendency to follow one's own stars for either aspirational or identification reasons might be universal, success still depends on how stars are portrayed and meaningfully embedded in stories in the complex symbolicity of film. American films could not quite speak the language of film in Germany, even silent film.

In the mid-1930s, Kohner argued that European movie audiences would accept films based on American history, but only if set in exotic locales, such as the American West; films set in colonies also attracted audiences. Otherwise, historical references should be as European/German as possible: “Leaving aside Westerns and big spectacles, which have always gone over in Europe as well as in America, the next best thing is either to develop more serious films . . . or to devise more serious twists, more sophisticated tones, for the average program product.” The “psychology of European movie-audiences is the fact that they are more serious than American audiences. Much that is not entertainment for American movie-goers is entertainment for them. Witness the great box-office success of a ‘social' film like Our Daily Bread” (1934, released in Germany in 1936), which became “a box-office clean-up” and the second most popular film of the year in Berlin. Kohner criticized the “exaggerated” realism or “fake realism of the gangster film” and stressed that “European audiences sensed the underying sincerity and authenticity of this film and flocked to see it.” Kohner suggested filming two versions of the same film built around a similar theme, one more “serious” and “extreme” in its realism. Costume dramas or romantic films, especially, needed to be grounded in European tastes that are “more sophisticated, more adult in viewpoint and characterization,” with “greater dramatic depth and psychological subtlety” and “more convincing characterizations—not standardized movie ‘types,’ but real individuals, true to life.”Footnote 76

Such films needed to pay close attention to European social manners, references, and morals. For instance, under Hugenberg UFA specialized in conservative-national films featuring figures from German history, such as the very popular sound film The Flute Concert of Sans-Souci (1930), which glorified Prussian military expansion; it was released a day before the prohibition of Universal's antiwar All Quiet on the Western Front. Sans-Souci itself referenced Adolph Menzel's famous painting, familiar to German audiences. Prussian royal history offered a space for big-budget historical costume dramas with a heroic past (Fridericus Rex [1922–1923], The Mill at Sanssouci (1926), The Flute Concert of Sans-Souci). Historical melodramas were common.Footnote 77 German films drew upon their own rich story tradition. They could tap into the mystical secret worlds of legends found in fairy tales and myths that were sometimes precursors to the horror genre (Der Golem [1914]). Lang's massive Die Nibelungen leaned upon German epic poems; Murnau's Faust rested on the original folktale.

Kohner criticized many American movies for their plot contrivances that Europeans found unconvincing. For instance, Universal's Hell's Heroes (1929)/Galgenvögel (1930), directed by William Wyler, failed to achieve high-art status and thus eligibility for a tax deduction because of its insufficient realism and “improbabilities.” One critic highlighted that (German) babies were in reality unable to digest condensed milk or drink bad water or keep their heads so upright as portrayed in the movie. And how can a sandstorm not wipe away horseshoe prints in the sand?Footnote 78 Universal's Frankenstein was banned in Sweden, Ireland, Australia, and, later, Italy and Czechoslovakia as too gruesome. Yet, ever enamored to the stunt, Laemmle stressed how many members of the audience needed medical help after watching the film. In Germany, Frankenstein first ran as a silent film because of technical-patent issues and so featured long-winded textual interludes that broke the sinister mood. Germans thought the mountains looked like cardboard. They were used to the “mountain film” genre filmed on location with stunning cinematography, as discussed below. And what was a northern European windmill doing in southern Tyrol? One critic asserted, “One should neither bring windmills to Tyrol or kitschy American horror films to Berlin.”Footnote 79 In 1932, Kohner wrote to Laemmle Sr.: “The picture was dubbed into French and I am convinced that it would have been a far better success in Germany if we had done the same thing.”Footnote 80 The examples illustrate just how easily the suspension of disbelief can be ruined, even for good films, by getting a few things wrong.

Subtle cultural codes made crossing borders more difficult. Film historian Anna Sarah Vielhaber identifies a “cultural discount” for foreign films in Germany between the 1930s and 1960s, finding a surprising number of parallels between American and German popular films in regard to plots and their focus on adventures, love stories, friends, and families.Footnote 81 Yet German audiences preferred to watch themselves in familiar spatial, contemporary, and historical settings accompanied by German folk or classical music; classical music was also central to German identity and Kultur.Footnote 82 The emergent “modern” American jazz and swing accompaniments in the 1920s were not only foreign but sometimes deemed suspect because of their roots in African-American culture (Hitler and Goebbels banned swing as “degenerate music”). A few settings were particularly popular among Germans: the home village (Heimat) as an idyll, the military or military officers as key figures, and an idealized high (aristocratic) society (feine Gesellschaft) with its operetta tradition and elaborate ballroom scenes. The pre-1914 Imperial historical period acted as an anchor point as the “good old times,” often conservative in tone. Many films oriented themselves to theater and literature; individual scenes might reference well-known paintings or iconography.Footnote 83

The invasion of American films projecting an “American way of life” along with jazz, dances like the Charleston, “new women” (the bobbed flapper), and boxing induced anxiety among this conservative class that dominated print mediums, academic and literary culture, and cultural criticism. Germany as a land of Kultur is an immensely complicated issue, but it drove self-perceptions, especially among conservative-nationalists.Footnote 84 American modernism was exciting but dangerous and uprooted; these were major themes in Universal's Prodigal Son.

The criticisms of the Parufamet films also highlighted that American advertising tended to scare away or disappoint the German audience with its hard sell. “Carl Laemmle Presents” posters stressed “kick.” To a Harvard Business School audience in 1927, Robert H. Cochrane, the head of advertising for Universal, related how he had once suggested “throw[ing] a bucket of blood across this thing [poster] to make it more attractive and gory,” and to his surprise the theater owner liked it.Footnote 85 For many Germans, American advertising was garish or too over-the-top. For instance, The Man Who Laughs was well-received critically, especially the performance of Conrad Veidt, but German audiences were disappointed because the film did not match the hype.Footnote 86

Germans also flocked to comedies, the genre with the highest cultural discount. Film historian Jan-Christopher Horak estimates that in 1928 one-quarter of feature films were comedies, with a good portion exhibiting a distinct Berlin-based, quick-witted German-Jewish sensibility (made most famous by Ernst Lubitsch and Billy Wilder).Footnote 87 Drawing upon Jewish physical and verbal comedic traditions, German comedy could be very transgressive and subversive regarding social norms and sexual taboos. The German-Jewish comedian Felix Bressart was the highest-paid film actor during the late Weimar Republic; he would appear later in Lubitsch's anti-Nazi comedy, To Be or Not to Be (1942). The curated set of classics representing Weimar cinema do not represent the array of film and film stars popular in the 1920s, especially comedies. The lighthearted musical-comedy operetta Three from the Filling Station (1930), which paired the popular film couple Willy Fritsch and Lilian Harvey, was the most lucrative film of the year. Even Arnold Fanck of “mountain film” fame generated two high-grossing ski comedies with Leni Riefenstahl (The Great Leap [1927] and The White Ecstasy [1931]).Footnote 88 It was with the Nazis that German film lost its sense of humor.

German audiences gravitated toward stories involving crime, adventure, and romance, but Weimar cinema developed a number of genres, a narrative system for organizing meanings, that were unique. There was a fascination with the psychology of crime and deception or detective work epitomized by Fritz Lang's Dr. Mabuse films: Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922) and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933). But these crime dramas did not morph into American gangster films; they reflected the uncertainty or dark side of German social life.Footnote 89 Another genre was the “intimate theater” or “chamber drama” (Kammerspiel) that portrayed the lives of ordinary people of the lower middle class in crisis in intimate, if not claustrophobic, settings, with great emotional resonance, such as The Last Laugh and G. W. Pabst's The Joyless Street (1925) with Greta Garbo. They explored the seedier undersides of German life, difficult circumstances, and tragedy (Asphalt [1929] by Joe May, Diary of a Lost Girl [1929] by Pabst). A related genre, the “street film,” had similar premises but emphasized social realism and criticism, class tensions, and the difficulties of navigating an urban world; the street expressed danger, crime, and sexuality. Such genres later influenced American film noir with their characteristic blend of crime, seduction, and the femme fatale.Footnote 90

Another popular genre, almost a franchise of stars and tropes, the “mountain film,” made stars of Luis Trenker and Leni Riefenstahl (The Holy Mountain [1926], White Hell of Piz Palu [1929], Storm over Mont Blanc [1930], Berge in Flammen [1931]/The Doomed Battalion [1932]). The genre was notable for its cinematography of the Alps and clouds combined with action stunt photography, with cameramen filming while on skis or from impossible vantage points. Riefenstahl learned her cinematography from these films. Fanck's “mountain films” celebrated men (excepting Riefenstahl) battling nature, successfully and unsuccessfully. These were “action movies” but tapped into Romanticism's exalted “sublime” counterbalanced with the excitement of the abyss, with men balancing at life's edge in snow and ice.Footnote 91

Kohner was a fan. He had tried to sign Trenker, a sort of mountaineer John Wayne of the Alps, to make White Hell of Piz Palu, but the chief executive of Deutsche Universal turned it down. H. R. Sokal-Film produced the film instead, and in Laemmle's words, “Sokol [sic] has become a millionaire. I know dozens and dozens of instances where Universal has given great pictures away and the other fellow has become rich.”Footnote 92 White Hell of Piz Palu was the second most popular film of that year. After this mistake, Kohner signed Trenker to Deutsche Universal for Der Rebell and The Prodigal Son, as well as Fanck and Riefenstahl for S.O.S. Eisberg. S.O.S. Eisberg is a sort of remake of White Hell among icebergs with many of the same stars.

Cultural distance also limited the appeal of European films and stars to Americans. In Budapest, producer-director Joe Pasternak made a European star of Hungarian Franziska Gaal for Deutsche Universal, but she failed to make the transition to Hollywood.Footnote 93 In the early 1930s, Universal considered signing the operetta singer and film star Marta Eggerth, as “she is the youngest, most attractive and sexiest of all the operatic players in pictures.” However, she spoke English with a slight accent, which needed rectification; although she had (fortunately) lost twenty pounds, achieving “about the same figure as Ginger Rogers,” and “would still be a fine financial investment in the world market,” she had more appeal for Europe than America. Universal maintained the right to reframe her public image, against her husband's wishes, but luckily, as one Universal executive wrote to Laemmle, “Miss Eggerth is one of the cleanest girls I have ever known.”Footnote 94 American film studios tended to mold their stars into a template of the wholesome American girl next door.

The tone and pacing of films differed. A executive of Famous Players-Lasky told his Deutsche Bank counterparts that long slow scenes such as a burial procession he saw in one film simply would not work in the United States. Americans “preferred a lot more amusing things and that it all fits together so that almost all American films show a happy end.”Footnote 95 One study of German films notes the lack of cross-cutting and closeness of shots that tend to make the story more dynamic. Scripts took their time to introduce characters. Many German films relied on filming classical stage performances, giving them an allure and “cultural value” that could garner both special awards and tax breaks. More inventive use of camera angles, too, including reverse angles and point-of-view shots at different distances, appeared more regularly in American film. The most appreciated feature perceived in American films was a “down-to-earth and concise style of narration.”Footnote 96

In another memo, Kohner recommended to his Universal colleagues, “I think for ourselves to educate ourselves to a certain extent to gain an insight into what foreign audiences like, we should show each week at least one foreign picture, and we all should see them, and not feel that we are being forced to do something we do not want to do. I know it is difficult—as Mr. Boylan puts it—to see these melancholic Mediterranean pictures; but nevertheless, I think it would be valuable and help.”Footnote 97 Kohner's advice and Boylan's characterization speak volumes.

Nonetheless, Weimar cinema not only challenged Hollywood in terms of the quality of its aesthetics, creativity, and film talent in front of and behind the camera, as epitomized by the Weimar canon, but also offered a robust set of genres and stars that addressed issues that better appealed to the broad, popular tastes of the German public. Of the classic films that now define Weimar cinema, only a few films—such as Metropolis, Homecoming (1928), White Hell of Piz Palu, Westfront 1918 (1930), and The Blue Angel—landed among the most popular films of their respective years.Footnote 98 Weimar film excelled in three areas in particular: it derived its staging from a deep theater tradition; it borrowed heavily from Modernist avant-garde art; and it mastered cinematography that created a culture of light and shadow to illuminate character, set the mood, and enhance the story. Many German sets became masterpieces of the form with great attention to lines, perspective, design, lighting, and camera placement. Weimar film rested upon the close partnership between director and cinematographer. Interestingly, many German cinematographers who emigrated to the United States had a difficult time adjusting to the Hollywood studio system.Footnote 99

However, the greatest difference from American cinema was that German cinema implicitly or explicitly processed the horrors of World War I and its harrowing aftermath. It was “shell shock” cinema: “There are ghosts . . . they are all around us” is the famous first sentence of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).Footnote 100 The mysterious mass deaths, coffins, sets of denuded trees, references to dirt and rats of Nosferatu (1922), all recalled the trenches, the postwar cholera epidemic, and putrid bodies; “mass dying” as a backdrop.Footnote 101 Other popular films such as Metropolis, White Hell of Piz Palu, Storm over Mont Blanc, Mountains on Fire (1931), and Kameradschaft (1931), the latter a dramatization about a real-life 1906 French mining disaster in which over one thousand people were killed, all turn into war movies at key points with evocative visuals. In one scene in White Hell of Piz Palu , the protagonists venture deep into an ice crevice to rescue the bodies of frozen comrades. In Storm over Mont Blanc, lightning strikes double for artillery fire. Simple melodramas registered the disruption of everyday family life and psychological duress. At about the three-quarters mark of Walter Ruttman's Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927)—a semidocumentary portrait of a day in the life of Berlin from morning to night, set to music—the film creates a mini-fictional surreal montage of spinning, out-of-control images before coming back to normal.Footnote 102 That montage sequence makes no sense without reference to the crises of war, defeat, and hyperinflation.

While the Hays office viewed film as a general advertisement for an “American way of life” built on a vast new array of consumer products (“trade follows film”), German film implicitly or explicitly expressed the pain of a lost war and hyperinflation, acknowledged the knife edge between poverty and middle-class respectability, highlighted the process of urbanization and/or loss of a small-town ideal, and processed the anxieties (and hopes) of a deeply divided country undergoing immense social and political change. Films offered escapism but drew upon reference points of historical insecurity or more conservative refuges such as tranquil village life. A number of films referenced der Schieber, the black market hustler, who games people of life's basic necessities.Footnote 103 In Lang's M (1931), the film opens with a familiar (to Germans) but chilling nursery rhyme that threatens children with being cut into pieces. The film references real-life serial killer Fritz Haarmann, the “Butcher of Hanover” or “Wolf-Man,” who sexually assaulted and dismembered more than twenty boys over a six-year period. Just before M was released, Peter Kürten, the “Vampire of Düsseldorf,” was executed for serial sex-murder just prior to the film's release. Many people thought Lang was trying to cash in on sensationalist events.Footnote 104 The point is that one had to be there to understand the references and mood, as Kohner stressed.

Lest this all seem dark, popular German film excelled in light-as-air comedies (sound picture operettas) that expertly blended in musical numbers to advance the plot and emotions. These proved popular escapism in the face of unemployment. Deutsche Universal employees including Joseph Pasternak, Henry Kosterlitz (Koster), and Felix Joachimson (Jackson) first met in Berlin in 1932 to develop one such operetta, Five from a Jazz Band (1932). In Budapest, the three collaborated on such musical comedies with Gaal. In exile in Hollywood, they transposed the operetta genre with the newfound Deanna Durbin in Three Smart Girls (1936), complete with classically tinged musical scores. They even remade a Pasternak-produced 1934 Budapest film starring Gaal into a star vehicle for Durbin, Spring Parade (1940). These immensely profitable films helped lift one studio out of near bankruptcy.

That studio was Universal Pictures. Durbin became the “Queen of Universal,” with a range of popular films into the early 1940s. In 1938, 17 percent of Universal Pictures’ net profits stemmed from Durbin's films.Footnote 105 Exiled European film transformed Hollywood and saved Universal.

Mistranslations, 1930–1934

These differences explain why a localization strategy finally proved most effective for Universal. Kohner shifted Deutsche Universal after 1930 to a strategy of quality local production in Germany for Germans by Germans: “Not quantity—but rather quality is the slogan of Deutsche Universal.”Footnote 106 Kohner argued, “I am completely convinced of our production in Europe. The import of German actors [to America] is not profitable. . . . Production should be where one can select from the abundance of acting talent there and where one can instantaneously feel the taste of the public. All else is just experiment.”Footnote 107

Political

Just as political risk increased with the rise of the Nazis, Universal found commercial success with a run of popular films by tapping into memories of war, moving into the mountain film genre, and hiring known director-stars such as Fanck, Trenker, and Riefenstahl. Between 1928 and 1935 Deutsche Universal produced thirty-five joint productions in Europe, mostly in Germany but also in Vienna and Budapest until forced out after 1934, then retreating to Vienna, Budapest, Paris, and finally London.Footnote 108

The first crossover success was All Quiet on the Western Front, based on the German novel by Erich Maria Remarque. While much of the literature has focused on the Goebbels-induced riot and the film's subsequent prohibition, All Quiet ranked sixth overall for the year and was the most popular American film in Germany in 1931–1932. Laemmle Sr. was attracted to the “universal” themes of the film, which told the story of four German soldiers struggling through the war. Laemmle Sr. thought the film could rehabilitate the Germans as human beings with the same universal emotions, fears, and pains as other nations’ soldiers and in doing so would be more effective than all the “peace meetings and disarmament conferences.”Footnote 109 The movie was dubbed in three different language versions: English, French and German. It received Universal's first Oscar, in November 1930, one month prior to its German premiere.

Censorship

All Quiet did not face trouble only in Germany. Every national censorship board in the world had an opinion on it, and as a result, a fully reconstructed English-language version of the film did not exist until 1997.Footnote 110 It was banned outright in Italy, Austria, Japan, Turkey, Hungary, Bulgaria, Soviet Union, and China (the latter owing to German pressure). Military authorities in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, France, and Germany were all dismayed by its anti-militarist, antiwar message. Australia and New Zealand temporarily prohibited the film on the grounds that it was antiwar propaganda. France only approved All Quiet because Universal cut its scene of French women cavorting with German soldiers. The undersecretary of fine arts interceded on Universal's behalf after intense personal lobbying.Footnote 111 Right-wing critics in Germany felt it was defamatory to the nation and portrayed German soldiers as defeatist.Footnote 112

In Germany, All Quiet premiered to a select audience of dignitaries on December 4, 1930, with little incident, but the next night has gone down in history. After a scene in which German soldiers retreat, Joseph Goebbels stood up in the front row and proclaimed the film a “Jewish lie,” a “Jewish obscenity,” and a “Jewish film” by a “Jewish Germany-hater” (meaning Laemmle). Goebbels had purchased one-third of the premiere's tickets and started a faux “spontaneous” revolt by releasing mice, stink bombs, and sneezing powder. Brownshirt thugs dressed in civilian clothes beat several members of the audience and robbed the box office, while yelling, “Money out, Jews out, end this Jewish garbage.” Police and stormtroopers clashed outside the theater. The Nazis organized street demonstrations and boycotts of theaters that made international headlines.

A week later, on December 11, the Supreme Film Censorship Board banned the film for inciting violence, being a danger to public order, and “damaging German prestige.” The Interior and Defense Ministries concluded that All Quiet was an extension of Laemmle's anti-German hate propaganda of the last war. Goebbels declared a Nazi “film victory.”Footnote 113

Yet Goebbels was wrong. At best, the prohibition was a temporary victory. Germans could still see the uncensored versions in neighboring countries and even commandeered special buses and trains to travel to see the film. Left and center parties protested against its prohibition. Led by Sam Spiegel, later a film producer (On the Waterfront [1954], Bridge over the River Kwai [1957], Lawrence of Arabia [1962]), Universal worked hard to overturn the ban. With Remarque's cooperation, they released a re-edited version after September 2, 1931, that omitted some of the most provocative material, but even with these cuts, the film's antiwar message was crystal clear—and the film was a popular hit.Footnote 114

In a subsequent debate about United Artists’ Hell's Angels (1930), and under the influence of All Quiet's reception, the German government amended its film laws in July 1932. The new Article Fifteen could prohibit the import of films if German authorities objected to other versions showing in foreign markets.Footnote 115 After Hitler came to power, All Quiet was banned once again. Laemmle and Remarque were among the first people banned from reentering Germany in the first purges of Jewish intellectuals, artists, and politicians. All Quiet tapped into Germans’ fascination with the war experience. G. W. Pabst's Westfront 1918, a grittier antiwar film set in the trenches, also attracted a large audience, and the Nazis banned this film as well.

The All Quiet controversy has overshadowed Deutsche Universal's remarkable box office success in these years. During the Depression, the Berlin film industry could even praise Universal for providing jobs; the 1932 German Olympic team owed much to Laemmle.Footnote 116

The first, if dubious, success came with Der Rebell. Luis Trenker starred and codirected with Kurt Bernhardt (Curtis Bernhardt); both Bernhardt and Kohner, the producer, were Jewish.Footnote 117 Der Rebell premiered in Stuttgart on December 22, 1932, and in Berlin on January 17, 1933, two weeks before Hitler was appointed chancellor. The Film-Kurier praised the film as a symbol of “German-American cooperation in production”; with it, Universal “had reached a significance on the German market that it had never possessed before” and a real “hit with the public.”Footnote 118 Based loosely on the real-life Tyrolean leader Andreas Hofer, who had led an uprising against Napoleon, Der Rebell might, without any historical context, be described as the story of a small band of rebels facing off against a major authoritarian military power, a Tyrolean Braveheart (1995), or Star Wars (1977), or American revolutionary uprising against the British Redcoats in its core plot. But Der Rebell had no American-style victory or “happy ending.” At the end, the main rebel, played by Trenker, and two fellow rebels are executed by a French firing squad, yet their spirits march undaunted and undefeated into the sky with flags flying. Nature and God—a cross with a crucified Jesus is conspicuous—feature prominently on the side of the martyred rebels. A scene in the middle where the main character cries out that “Germans should not be cracking each other's skulls, but should come together” garnered “hurricane-like applause.”Footnote 119

Here is where intention and reception diverged. Der Rebell can only be understand in the interpretive horizons of the German public at the time. Germans received the film as a resistance film against the French and the Versailles Treaty. Italy prohibited the film as it implied that Tyrol was part of Germany; Italians interpreted it as a call for a German rebellion against Italian rule in Tyrol.Footnote 120 The main protagonist's phrase about holding together echoed the very real fighting in German streets as well as a phrase familiar from the 1920 Kapp Putsch attempt: the head of the military stated that the “army should not shoot at the army.” Andrew Marton (also Jewish), an editor and screenwriter, thought he, Kohner, and Bernhardt were making a story about “simple people” or “peasants” rising up against Napoleon, even hoping to draw a parallel between Hitler and Napoleon as a fight against a dictator, but the ethnic Tyrolean Lederhosen costumes looked like Bavarians fighting against French uniforms. According to Marton, some German youth even interpreted All Quiet in the following terms: “Gee, what a great war picture. Look at those heroes in the trench. And all those explosions! It's marvelous!”Footnote 121 In April 1933, the Film-Kurier noted that in spite of “foreign and non-Aryan financing—Luis Trenker still managed to create a good film that contributed on his part to pave the foundation for the German uprising.”Footnote 122 The U.S. trade commissioner in Berlin, George Canty, noted on January 21, 1933, “The subject of this successful film should reinstate Mr. Laemmle into the good graces of the Government after the ill-feeling created by ‘All Quiet.’”Footnote 123 It did not.

Trenker rode the wake of the film's success and Hitler's accession to power, becoming one of the first film stars of the Third Reich. Goebbels declared Der Rebell a “masterpiece. . . . One can see what one can make out of a film.” Hitler loved it, and both watched it at least three or four times.Footnote 124 Goebbels singled it out along with Battleship Potemkin (1925), Anna Karenina (1927), and Die Nibelungen as models for the new National Socialist film.

Just weeks after the premiere of Der Rebell, in March 1933 Deutsche Universal was forced to stop distributing Das Brennendes Geheimnis/The Burning Secret (1933). The film was based on a book by Stefan Zweig, with a screenplay by Kohner's brother, Friedrich (later most famous for his surf-oriented Gidget character), and directed by Robert Siodmak (The Killers [1946]). They had to edit the names of Zweig, Siodmak, and Kohner out of the movie because they were Jews. Goebbels then banned the film entirely because it was deemed too “Jewish” and “unhealthily erotic.”Footnote 125 Deutsche Universal was also the foreign-language distributor and partial financer of Fritz Lang's last German film, Das Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), but Goebbels banned that film as a danger to public order because it showed how a small group of determined gangsters could overthrow a government. Kohner desperately wired Laemmle to advance loans in dollars to keep the Paris premiere on track, as Deutsche Universal's German accounts were frozen.Footnote 126 Lang's film premiered in April 1933 in Budapest and, in its French version, in Paris, the version most Europeans could see.