1. Introduction

It is almost undisputed that the CJEU has been an engine of supranational integration in the European Union (EU).Footnote 1 This has led scholars to argue that newly established RICs outside Europe should replicate the design features and jurisprudential principles of their European cousin if they want to trigger legal and political integration.Footnote 2 This article challenges this scholarly position by demonstrating that RICs become engines of supranational integration not because of their institutional design or because they develop specific jurisprudential principles, but rather because they meet favourable conditions in the institutional, political, and societal contexts in which they operate.

The article takes the CACJ and the CCJ as case studies. Some scholars have branded these two courts institutional copies of the CJEU.Footnote 3 Both courts have also borrowed jurisprudential principles from the Luxembourg Court with the goal of expanding the reach of Central American and Caribbean Community Laws vis-à-vis hostile institutional and socio-political contexts. The article considers whether the pro-integration rulings of the CACJ and CCJ have fostered supranationality in their respective systems – the Central American System of Regional Integration (SICA) and the Caribbean Common Market (CARICOM). In so doing, the article outlines the preconditions allowing RICs to become engines of supranationality in different institutional and socio-political contexts. The analysis has broader implications beyond the empirical comparison between the two systems. Investigating the rarely-discussed Caribbean and Central American experiences provides unique insights which may help to nuance the theoretical approaches to supranationality and supranational adjudication. The article shows that, although the CACJ and the CCJ have borrowed design features and jurisprudential principles from the CJEU, the two courts have thus far failed to nurture supranationality in the SICA and the CARICOM. In other words, during the process of ‘tropicalization’, EU Law has lost the power to foster integration with which it is usually credited by scholars. This suggests that, very often, too much emphasis is placed on formal rules and principles and that the CJEU should not necessarily be the benchmark to evaluate other RICs. The CJEU is the product of uniquely European legal, political, and social domains as well as historical contexts and, thus, the import–export of its peculiar design features and jurisprudential principles to other operational contexts may not result in similar outcomes. For this reason, understanding how RICs contribute to the construction of supranational systems requires investigation into the institutional and socio-political contexts in which these courts operate and assessment of whether and the extent to which their practices become part of the general structuring of the polities and societies in which they are called to act. The conditions allowing RICs to become engines of integration, in fact, lie for the most part outside the direct control of judges, most notably, in other institutional (i.e., regional Secretariats and national judges) and societal (i.e., legal professionals, elites, and academics) actors as well as in the national and regional political environments in which these courts operate.

These considerations are increasingly important in light of the current existential crisis of the EU and, more generally, of international institutions and law. Political pushback, member states withdrawing (or threatening to withdraw) from regional organizations, and non-compliance with RICs’ rulings and regional policies have been rather common in the SICA and the CARICOM. Hence, a comparative analysis of the trajectory of supranationality in Central America and the Caribbean may also shed a different and more nuanced light not only on the experiences of these two regions but also on the future of European integration and, more broadly, of international law and institutions.

Methodologically, the article relies on 63 qualitative interviews with key stakeholders of the SICA and the CARICOM.Footnote 4 The interview-based research was informed by an approach known as reflexive sociology of law and was aimed at understanding institutional and legal developments from the perspective of the agents surrounding and operating the two courts.Footnote 5 Using this approach to the CACJ and the CCJ allowed me to frame these courts not as autonomous entities that develop and change through endogenous and self-referential legal logics, but rather as historically produced social constructions that are deeply embedded in different national, regional, and international relations of power, which, in turn, shape their activities through a variety of processes (i.e., professional interests, visions of law, ideologies, education, socialization, and so on).Footnote 6 For this purpose, the heuristic notion of the (legal) field proved to be a very helpful research tool for guiding the empirical enquiry.Footnote 7 The research frames the social space (field) of the CACJ and the CCJ in terms of a network of objective (adversarial) relations concerning the meaning and purpose of these two institutions – and, more generally, of Central American and Caribbean Community Law. This framing allowed me to capture how social continuities and discontinuities in the construction of power relations, professional practices and interests, as well as visions of these worlds, have impacted on the capacity of the two courts to foster supranationality in their respective fields of operation.Footnote 8

The remainder of the article proceeds as follows. Section 2 discusses the approach of the article, situating it within the existing scholarship. Section 3 introduces the SICA and the CARICOM systems and the most relevant rulings of the CACJ and of the CCJ. Section 4 argues that the failure of the two courts to stimulate and drive supranationality in the SICA and the CARICOM is chiefly due to the lack of contextual permissive conditions able to translate the normative efforts of the two courts into concrete political and legal realities. Section 5 concludes by re-calibrating the discussion on how RICs can become actors in building supranational systems.

2. Towards a theory of de facto supranationality

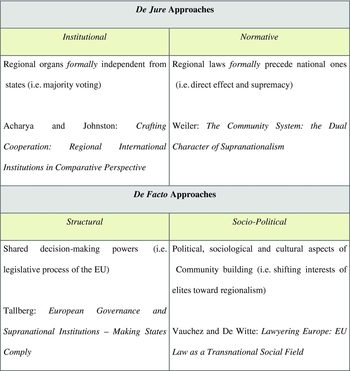

Regional institutions are supranational when their organs penetrate the surface of the states and interact directly with the principal players in national systems.Footnote 9 Key questions relate to how regional organizations become supranational and how RICs contribute to this enterprise. I divide the literature on such topics into de jure and de facto approaches. De jure approaches focus on the formal powers of regional organizations. These powers may be delegated by the states and/or developed by the regional organs independently. De facto approaches refer to the actual exercise of powers by regional organizations and how these powers concretely shape the behaviour of institutional and societal actors.

De jure approaches can be further divided into institutional and normative. Some institutional approaches codify the legal features of regional organizations and courts, explaining how variations in design features and formal rules influence regime efficiency.Footnote 10 Others propose checklists of factors and actions that regional organizations and courts must either contend with or perform in order to become effective.Footnote 11 In this view, regional organs are supranational when they are formally independent from states, meaning that their governing body is not composed of representatives directly instructed by governments.Footnote 12 As far as the EU is concerned, its Commission, Parliament and the CJEU are institutionally supranational, as they enjoy substantial autonomy from national governments.Footnote 13 Likewise in the Inter-American Human Rights System (IAHRS), the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) is institutionally supranational, it being composed of independent individuals serving in their personal capacity and not as state representatives.Footnote 14 Normative approaches focus on the correlation between regional and national laws. In this sense, regional organizations are supranational when their measures and laws are directly applicable in national legal systems and have precedence over national ones.Footnote 15 The doctrines of direct effect and supremacy developed by the CJEU are emblematic examples of normative supranationality.Footnote 16

The de facto approaches can be further divided into structural and socio-political. Structural approaches refer to the distribution of decision-making powers between various regional organs and how these powers are concretely exercised. According to this view, regional organizations are supranational when decision-making powers are shared by various organs, and/or when compliance with regional policies and laws is ensured by means of a decentralized system.Footnote 17 The legislative prerogative of the EU – exercised jointly by the Council, the Commission, and the Parliament – is an example of structural supranationality. Other examples of structural supranationality are the manner in which different actors (i.e., Commissions, national judiciaries, and private parties) ensure compliance with EU law.Footnote 18 Finally, socio-political approaches refer to aspects related to national and regional politics, objective constraints of prevailing economic and states interests, subjective elements of identity and community building, and the professional interests of the stakeholders of regional organizations.Footnote 19 Often the shifting interests of legal and political elites towards regional law and policies signal increased supranationality. Figure 1 illustrates schematically these four approaches.

Figure 1. De Jure and De Facto Approaches to Supranationality

These theories enrich the study of supranationality. Yet, they approach the various aspects of this concept in a disaggregate manner by singularly assessing design features, normative reasoning, compliance, inter-institutional dialogue, as well as political and societal involvement in regional organizations. This article takes a different stance and analyzes these aspects jointly, focusing on the interplay between the de jure and the de facto facets of supranationality.

Figure 2 displays the four aspects of supranationality as nested, suggesting that regional organizations first need (some) de jure features (institutional and/or normative), and that these must be somehow transformed into de facto features (structural and/or socio-political) in order for a regional organization to become effectively supranational.

Figure 2. The Interplay between De Jure and De Facto Aspects of Supranationality

To empirically trace the trajectory of supranationality in regional organizations and to assess how RICs foster this process, I employ the logic of the authority model developed by Alter, Helfer, and Madsen.Footnote 20 The model differentiates de jure from de facto authority; de jure authority is a position of normative power granted or constituted by norms, while de facto authority depends on the reception of rulings in the practices of key stakeholders.Footnote 21 I apply this methodological approach to the idea of supranationality. In this picture, de jure supranationality corresponds to: 1) the formal delegation of powers to regional organs and RICs; and 2) the establishment of pro-integration principles through the case law of RICs (the two smaller circles in Figure 2). Yet, because of the peculiar contexts in which regional organizations and RICs are entrenched, the formal delegation of powers and pro-integration case law are insufficient to build effective supranational systems. In other words, de jure supranationality must be transformed into de facto supranationality (the two larger circles in Figure 2).Footnote 22 Applying the logic of the model of Alter, Helfer, and Madsen to supranationality is useful for an additional reason. The model identifies key contextual factors in transforming de jure into de facto authority. In my view, the same factors explain the transition (or lack thereof) from de jure to de facto supranationality. These factors are institution-specific (i.e., different access rules and jurisdictions, alternatives to litigation, and variations in subject matter competences), actor-specific (i.e., the different constellations of constituencies relating to RICs), and political (i.e., international, regional, and domestic politics).Footnote 23

The article uses this theoretical framework to assess the extent to which the (CJEU-inspired) de jure supranationality introduced by the CACJ and the CCJ in the SICA and the CARICOM has contributed to the transformation of these two organizations into de facto supranational systems. In so doing, the article delineates the contextual factors that may facilitate or obstruct the capacity of RICs to transform their normative efforts into effective supranational legal and political systems.

3. De jure supranationality in Central American and Caribbean regional organizations

This section analyzes the de jure aspects of the Central America and Caribbean systems of regional integration. These organizations were originally set up following the intergovernmental model, as they were conceived as mere fora for diplomatic and economic co-operation between states. The recent establishment of the CACJ and the CCJ, however, has increased the normative supranationality of both systems, as the two courts are formally independent from the member states, grant extensive access to private parties, and have adopted supranational principles in their rulings.

3.1. The dynamics of institutional design in Central America and the Caribbean

The first attempts at integrating the Central American and Caribbean regions date back to the 1950s and 1960s, when the Organization of Central American States (ODECA) (1951), the Central American Common Market (CACM) (1960), the Caribbean Free Trade Association (CARIFTA) (1965), and the CARICOM (1973) were established. These organizations were subsequently reformed in the 1990s and early 2000s when the SICA was created and the CARICOM reorganized.

Both the first and second generations of organizations dealing with regional economic integration in Central America and the Caribbean were aimed at regulating trade issues and fostering functional co-operation between states, and not at developing binding systems of rules. Furthermore, the CARICOM was conceived to complete the Caribbean process of decolonization from the United Kingdom, while the SICA is a spillover of the Central American process of pacification that occurred at the end of the Cold War.Footnote 24 Accordingly, the balance between law and politics in these organizations leaned towards the latter.

3.1.1. The intergovernmental infancy of the ODECA, the CACM, and the CARICOM

The first Central American organizations dealing with regional economic integration were mainly aimed at fostering political bargaining between states (the ODECA), turning integration into a viable strategy for economic development (the CACM), and, ultimately, pursuing industrial development in the region.Footnote 25 The institutional design of both institutions confirms their intergovernmental nature. The main organ of the ODECA was the Meeting of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs, whose decisions were taken by consensus. In 1962, the ODECA was amended and a supranational tribunal was instituted, which, however, was never called upon to decide any relevant issues. Similarly, the main organ of the CACM was the Central American Economic Council, composed of the Ministers of Economy of the member states, which required unanimity to determine whether decisions would be adopted by a concurrent vote of all members or a simple majority.Footnote 26

The institutional design of the CARICOM was modelled after the intergovernmental framework.Footnote 27 This organization was controlled by the Conference of the Heads of Government and the Council of Ministers, whose decisions were taken by consensus. Both the Conference and the Council were aided by a Secretariat. However, this was not a supranational body vested with executive powers like the European Commission. Finally, the CARICOM also included an intergovernmental procedure for settling disputes. These were solved either by the Conference, if the dispute concerned the interpretation or application of the Treaty, or by the Council, if the controversy concerned a breach of obligation under the Common Market. In the latter case, the Council could refer the dispute to an ad hoc tribunal, although its decisions were not binding.Footnote 28

The key role of the Ministers of Foreign and Economic Affairs (in Central America) and the Heads of Government (in the Caribbean), the voting procedures based on unanimity rules, and the lack of supranational secretariats and/or tribunals, underscore the centrality of governmental preferences in the ODECA, the CACM, and the CARICOM, and the flexibility of those systems. In fact, multiple escape routes and safeguard mechanisms were maintained for countries disagreeing with regional policies. In short, decisions could hardly be enforced against the will of the states.

3.1.2. Institutional reforms within the intergovernmental framework: the SICA and the second CARICOM

The Central American and Caribbean systems were reformed respectively in the 1990s and 2000s. Their restructuring, however, left the balance of power between states and community organs almost unchanged. In Central America, the first reforms were enacted during the peace negotiations of Esquipulas I and II, when it was established that the Presidential Meetings, together with a regional Parliament (the PARLACEN), would be the engine of regional reforms.Footnote 29 As these reforms turned out to be insufficient for the stability of the region, the Protocol of Tegucigalpa to the Charter of the ODECA (the Protocol) established the SICA, an umbrella institution aimed at facilitating economic, political, and legal integration and at completing the pacification process in the Central American region. Similar to its predecessors, the SICA was (and still is) almost completely controlled by the member states. Its main organ is the Meeting of Presidents, which takes decisions by consensus.Footnote 30 While the Meeting is characterized by a low level of institutional supranationality, the PARLACEN has certain supranational traits, as its members are directly elected by the people of the Central American states. Yet its political and institutional relevance is limited, as the PARLACEN has mostly consultative tasks.Footnote 31

In the Caribbean, reforms were pursued to respond to the challenges and opportunities presented by changes in the global economy following the end of the Cold War.Footnote 32 The Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas (RTC) renewed the Conference of the Heads of Government and the Council of Ministers as the main organs of the CARICOM. Yet, in the new framework, these two organs take decisions by a qualified majority of three quarters, and not by consensus. While these changes suggest an increased level of institutional supranationality, in reality the situation is different. The RTC counterbalances the fact that decisions can be taken by (qualified) majority by providing a way for states to opt out from formally binding decisions where they seek agreement of the Heads of Governments and the fundamental objectives of the RTC are not undermined.

The low level of institutional supranationality of the SICA and the CARICOM is also confirmed by the remaining institutional arrangements. Both organizations are equipped with administrative secretariats/commissions. These, however, do not have far-reaching executive powers similar to the European Commission, and they are neither independent nor autonomous from the member states, which also contribute directly to the financing of these organs. The secretariats also play no role in the legislative process of the two Communities and they are constrained both in their monitoring and implementation functions. In other words, far from being the ‘watchdogs’ of the Communities, the SICA and CARICOM Secretariats are mere administrative assistants to the Heads of Government.Footnote 33

The key role played by the Heads of Government, the de facto veto power enjoyed by the states in the SICA, the possibility for states to opt out from binding decisions in the CARICOM, and finally, the lack of independent secretariats/commissions, indicate the centrality of state preferences in the SICA and the CARICOM. This low level of institutional supranationality, however, did not paralyze the two systems, which, over time, have managed to introduce a significant amount of regional legislation. The centrality of states has, however, strengthened the intergovernmental political bargaining nature of the decision-making process of both systems, which continue to be perceived as fora for handling diplomatic relations rather than regimes able to establish binding obligations upon the states.

3.2. The rise of normative supranationality in the SICA and the CARICOM

The reforms enacted by the Protocol and the RTC brought elements of normative supranationality into the two systems. The two Treaties equipped the SICA and the CARICOM with the CACJ and the CCJ, which are institutionally supranational. The two courts are, in fact, politically autonomous from the member states, can take legally binding decisions, and allow private parties and national judges to file cases.Footnote 34 Moreover, both courts have attempted to strengthen the supranational features of their respective Communities through adjudication. In so doing, they made extensive use of EU Law principles and of doctrines developed by the CJEU, most notably: 1) the principle of direct applicability as set out by Article 288 of the TFEU, and 2) the principles of direct effect and supremacy as developed by the CJEU.Footnote 35

3.2.1. The uneasy relationship between directly applicable Community Law and dualism

One of the first issues faced by the CACJ and the CCJ was the direct applicabilityFootnote 36 of Community law. With regard to the CACJ, some had argued that the SICA's legal system is moderately dualist, as the Protocol establishes that SICA Law does not automatically translate into municipal law.Footnote 37 The CACJ rejected this view. Echoing the words of the CJEU, it ruled that the SICA constitutes a ‘new and autonomous legal order’ characterized by its direct applicability within the legal system of the member states.Footnote 38 According to the court, Central American Community Law automatically becomes law in the member states without them needing to explicitly incorporate it into national law through parliamentary approval.Footnote 39

In more recent decisions, the direct applicability of the Central American Community Law has been restated by the CACJ in three important cases: (1) an advisory opinion requested by the PARLACEN concerning the competence of the Guatemalan Supreme Court to rule on the constitutionality of regional treaties;Footnote 40 (2) a contentious case presented by a group of Costa Rican custom agents who asked the CACJ to nullify an act of the National Custom Service of Costa Rica;Footnote 41 and (3) a contentious case filed by the PARLACEN asking to invalidate the Panamanian withdrawal from the PARLACEN.Footnote 42 These three cases are important as they were brought against Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Panama which had refused to recognize the jurisdiction of the CACJ, having ratified only the Protocol and not the Statute of the court. In all three cases, the CACJ dismissed the arguments of the states that they were not bound by the jurisdiction of the court since they had not ratified its Statute through domestic legislation. In the court's view, obligations to comply with SICA Law do not necessarily stem from incorporation of regional treaties into national law but are a direct consequence of the Heads of State agreeing and signing regional agreements.Footnote 43

Issues related to the direct applicability of Community Law have arisen also in the Caribbean, although the facts and details of the cases were different. Within the CARICOM, the principle of direct applicability is contested, given the strong dualistic approach to international law that the Caribbean states inherited from the United Kingdom. Yet the RTC and some original jurisdiction decisions of the CCJ have established a soft direct applicability within the CARICOM. Firstly, Article 9 of the RTC establishes that member states must take all appropriate measures to carry out the obligations set out in the Treaty and that they shall abstain from measures which could jeopardize its objectives.Footnote 44 Relying on this norm, the CCJ constructed a twofold principle of direct applicability. On the one hand, the court stated that the rights expressly recognized by the RTC apply to individuals directly without necessarily being incorporated into national law. On the other hand, the CCJ added that, in the circumstances in which the RTC imposes obligations on the member states, ‘correlative rights’ are granted to private parties throughout the entire Community, thus expanding the reach of the Treaty.Footnote 45

3.2.2. Copy-paste and adaptations: The tropicalization of direct effect and supremacy

Having gone this far in making Central American and Caribbean Community Laws directly applicable, the Central American and Caribbean judges were inevitably faced with the issues of Community Law's enforceability and its relationship with national laws – that is, direct effect and supremacy of Community Law. In the SICA, the Protocol is silent about the question of direct effect and, accordingly, it has been argued that it is left to the discretion of the CACJ whether or not to import this principle to Central America.Footnote 46 In relation to the hierarchical relationship between national and community laws, Article 22 of the Protocol adopts a contradictory position, as it attributes to SICA Law a para-legal status when compared to national law.Footnote 47 Despite this rather limited role assigned to Central American Community Law by the Protocol, in more than one instance, the CACJ affirmed that SICA Law occupies a hierarchically superior position when compared to the national legislation of the member states,Footnote 48 and it directly creates rights and obligations on natural and juridical persons.Footnote 49 The CACJ also vested the national judges with the power to apply and interpret SICA Law as if they were Community judges.Footnote 50 In the words of the court:

Community Law is embedded in the national legal order of the Member States. This manifests in the direct applicability, direct effect and primacy. The Community constitutes a new legal order, in which the benefit of the Member States have limited, albeit in a restricted manner, their sovereign rights.Footnote 51

Within the CARICOM, the RTC is equally silent on the key questions of direct effect and supremacy. Generally, the strong dualistic approach to international law which characterizes the legal systems of the majority of Caribbean states seems to limit the applicability of these two doctrines to the system. The first President of the CCJ repeatedly denied the applicability of direct effect and supremacy in Caribbean Community Law. According to President de la Bastide, the RTC explicitly vests the CCJ with the exclusive jurisdiction to rule over controversies related to CARICOM Law.Footnote 52 In turn, this disposition entails that national judges are not allowed to rule on issues of Community Law, even when the interpretation of that act would be uncontroversial. President de la Bastide also pointed to key institutional differences between the CARICOM and the EU; in particular, the lack of an executive body modelled on the European Commission signals an implicit denial of the idea of a directly enforceable Caribbean Community Law.Footnote 53

Yet, in the Myrie case – the ‘Van Gend en Loos moment’ of the CARICOM as it has been coinedFootnote 54 – the CCJ introduced principles that echo the notions of direct effect and supremacy.Footnote 55 In Myrie – a case concerning a violation of the right to freedom of movement of a Jamaican citizen by Barbados – the CCJ was called upon to ascertain the validity of a decision by the Heads of Government of the CARICOM that was not converted into municipal law by Barbados. Here, the CCJ echoed the words of the CJEU and declared that Caribbean Community Law constitutes a ‘new and autonomous legal order’, thus implying the application of some aspects of the direct effect doctrine to the CARICOM.Footnote 56 The CCJ further added that:

Although it is evident that a State with a dualist approach to international law sometimes may need to incorporate decisions taken under a treaty and thus enact them into municipal law in order to make them enforceable at the domestic level, it is inconceivable that such a transformation would be necessary in order to create binding rights and obligations at the Community level. . . If binding regional decisions can be invalidated at the Community level by the failure of the part of a particular State to incorporate those decisions locally the efficacy of the entire CARICOM regime is jeopardized and effectively the States would not have progressed beyond the pre-2001 voluntary system that was in force.Footnote 57

Despite the rhetoric of the CCJ, which directly recalls the wording of the CJEU in Van Gend en Loos, conceptually speaking the court did not introduce the principle of direct effect to the CARICOM. The doctrine of direct effect presupposes the capacity of Community norms to be invoked by individuals in national courts, which are bound to apply them.Footnote 58 The principle developed by the CCJ in Myrie is different, as Caribbean Community Law produces direct effects only at the regional level. Yet, if read in conjunction with the doctrine of ‘correlative rights’ established by the CCJ in one of its former cases, this unique doctrine reinforces the normative supranationality of the CARICOM as it entails that, despite its ratification into national law, Caribbean Community Law can be enforced at the Community level by private litigants bringing cases directly before the CCJ.Footnote 59

4. Explaining the limited impact of the CACJ and the CCJ on de facto supranationality of the SICA and the CARICOM

Despite the normative efforts of the two courts, the SICA and the CARICOM remain largely intergovernmental. Both systems are still dominated by the member states, which control the majority of regional organs and still perceive them as fora for diplomatic relations rather than binding legal regimes. The normative principles developed by the two courts have also had little impact on the legal systems of their member states both quantitatively and qualitatively.Footnote 60

What factors explain the limited impact of the rulings of the CACJ and of the CCJ on the de facto supranationality of the SICA and the CARICOM?

It is argued that the lack of institutional, actor-specific, and socio-political preconditions has thus far impeded the two courts from transforming the SICA and the CARICOM into de facto supranational systems.

4.1. Institutional factors

An important limit on the ability of the CACJ and the CCJ to foster de facto supranationality in their respective systems is that the two courts are the only independent institutions guarding the implementation of the Central American and Caribbean Community Law. The rulings of RICs, however, only create legally binding obligations to comply with their judgments. Whether compliance with these rulings actually occurs depends on the behaviour of other actors, such as regional secretariats and national judges.Footnote 61

4.1.1. The limited co-operation with regional secretariats

The experiences of other international organizations, such as the EU, the Council of Europe, and the IAHRS, reveal that independent commissions and/or secretariats are of key importance in supporting normative supranationality. The EU Commission has played, and still plays, a central role in transforming the normative efforts of the CJEU into concrete legal and political realities. The Commission monitors the implementation of the Treaties, presents non-compliance cases before the CJEU, and supports the enforcement of the CJEU's rulings, thus functioning as ‘watchdog’ of the EU Treaties.Footnote 62 Although entrenched in relatively different socio-political and institutional environments, the European Commission on Human Rights and the IACHR have also played a pivotal role in allowing the normative principles developed by their respective judicial institution – the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) respectively – to have a concrete impact on the development and enforcement of human rights in Europe and the Americas.Footnote 63

The SICA and the CARICOM Secretariats are far from becoming institutional allies of their corresponding courts. This is especially evident in the SICA, where there are two main Secretariats – the Secretariat of the SICA and the Secretariat of the Central American Economic Integration (SIECA).Footnote 64 Firstly, although these two Secretariats are empowered in principle to file infringement cases before the CACJ, in practice they are rarely in a position to do so. In the SICA, matters of non-compliance with Community Law are preferably solved via political channels by submission to the Heads of Government after mediation by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs.Footnote 65 Secondly, the Central American Secretariats are financially dependent on the member states, which perceive them more as ‘servants’ of their interests than independent organs with powers to implement regional policies and laws against them. Thirdly, over time, the two Secretariats have developed a conflictual relationship with the Court. The skirmishes began in the late 1990s, when the CACJ was called upon to rule over conflicts between the Secretariats themselves, with member states, and with other regional organs (i.e., Costa Rica and the PARLACEN). In these rulings, the CACJ attempted to limit the role of the Secretariats by repeatedly claiming exclusive competence over all disputes arising in the SICA. The CACJ even attempted to establish a hierarchical relationship between the two Secretariats, ruling that, although historically the SIECA had played an important role in Central American integration, the establishment of the SICA – and within the SICA's framework of the CACJ – entailed a reorganization of the existing institutions of the Central American integration. The court, hence, concluded that it was now time for the Secretariat of the SIECA: ‘to mind its own businesses in order to avoid future ambiguities and contradictions’.Footnote 66 Not surprisingly, these rulings were not received positively by the Secretariats, which began to ignore the CACJ and even pushed the Heads of Government to create an alternative system of dispute resolution in the framework of the SIECA, which now is competing with the Court for tariffs- and business-related matters.Footnote 67

Also in the CARICOM, the CCJ and Secretariat have struggled to become institutional allies for reasons that have to do with the latter's limited powers and the insufficient number of lawyers among the Secretariat's staff.Footnote 68 Recently, however, after younger and pro-integration legal officers have made their way into key positions at the CARICOM Secretariat, the organ has become more supportive of the CCJ. In the Myrie case, the Secretariat was deeply involved in the proceedings, intervening as a third party, providing important documents needed to reach the decision, and, ultimately, giving leverage to the court in producing one of its boldest and most pro-integration judgements. The Secretariat was also central to the enforcement of the ruling against Barbados, which, after months of diplomatic negotiations, complied with the ruling.

4.1.2. The missing interaction with national judges

The limited impact of the two courts on the de facto supranationality of the SICA and the CARICOM is also due to a lack of interaction between judges at the national and regional levels. Key to the success of EU Law has been the widespread use of the process by which national courts ask the CJEU to rule on the interpretation of EU Law, known as preliminary reference. Many landmark judgments of the CJEU were, in fact, decided after a national court requested the Luxembourg Court to give its interpretation of EU Law in preliminary rulings. This ultimately created an alliance between the national judges and the CJEU aimed at monitoring the enforcement of EU Law.Footnote 69 Today, European national courts – although to a varying degreeFootnote 70 – effectively function as reviewing bodies of the policies of state executives and participate in protecting individual rights and implementing EU Law.Footnote 71 The importance of establishing links with national judges has also been underlined in relation to courts other than the CJEU. For instance, many of the difficulties facing the IACtHR in becoming an authoritative institution have been explained in terms of the significant troubles the Court has faced in bonding with its national counterparts.Footnote 72

In Central America, there is almost no interaction between national judges and the CACJ. Since the Court's opening in 1994, only a few preliminary rulings have reached the CACJ.Footnote 73 Moreover, although national Supreme Courts have formally endorsed the principles developed by the CACJ in several decisions,Footnote 74 Central American judges have been reluctant to embrace the jurisprudence of the Court. This is not only due to a widespread lack of familiarity with the jurisprudence of their regional counterpart among national judges but also – and above all – to longstanding clashes between the CACJ and certain national Supreme Courts (i.e., Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Panama) on the extent to which the CACJ was allowed to review national legal and political issues. The situation is similar in the Caribbean, where national judges largely ignore the rulings of the CCJ and CARICOM due to both lack of familiarity with the jurisprudence and a general mistrust in their regional counterpart. Although the RTC obliges national judges to refer cases to the CCJ whenever they face questions of Community Law, since the Court's establishment in 2005, not a single preliminary reference has reached the CCJ.

This lack of preliminary references is central to explaining the two courts’ limited impact on the de facto supranationality of the SICA and the CARICOM. Firstly, without preliminary references, the courts did not receive those cases that neither states nor private parties were willing to file, thus limiting their dockets in a significant way. Secondly, this situation has brought the question of compliance and enforcement back to the member states. While disobeying a decision of the CJEU nowadays means, in most cases at least, disobeying national courts,Footnote 75 contravening the rulings of the CACJ and the CCJ does not have the same legal and political consequences. This ultimately means that, within the SICA and the CARICOM, compliance with the decisions of the CACJ and of the CCJ depends almost entirely on the goodwill of the member states. This has been problematic especially in Central America, where many cases decided by the CACJ have been vehemently opposed by the states on the losing side of the disputes. In one case, Honduras even suspended the payment of its judges and threatened to withdraw from the Court as a sign of protest against an adverse decision.Footnote 76 Although in the Caribbean compliance with the CCJ's decisions has been less problematic, the limited interaction between the court and national judges has nevertheless complicated the issue significantly. In several instances, compliance with the CCJ's decisions was repeatedly delayed and, eventually, occurred only after political pressure was applied on the losing state.Footnote 77 Had these cases been brought through the mechanism of preliminary reference, such difficulties would have been avoided, or at least minimized, and the two courts would have had an easier time seeing their pro-integration principles penetrate the surfaces of member states.

4.2. Actor-specific factors

The limited impact of the CACJ and of the CCJ on the de facto supranationality of the SICA and the CARICOM is also due to the lack of transnational networks of lawyers and academics interested in transforming the rulings of the two courts into political and legal realities. Another key reason for the success of the CJEU is that its jurisprudence found fertile ground among the European legal professions. Over time, Euro-law advocacy movements used their positions of power to recommend domestic support for the CJEU,Footnote 78 while legal scholars celebrated the new legal developments and forged a field of Community Law lawyers.Footnote 79 In other words, the jurisprudence of the Luxembourg Court did not remain dead letter but became the object of an interpretive process of a widespread network of Euro-lawyers, who transformed the rulings of the CJEU into a judicial theory and practice of Europe. Similarly, the variable impact of the IACtHR on human rights in Latin America has been explained by looking both at the practices of constitutional law attorneys in each state and at the development of transnational networks of lawyers interested in advancing a liberal vision of constitutional law.Footnote 80

The Central American and Caribbean practicing lawyers have thus far shown little involvement in the legalization of the SICA and the CARICOM. This is because the CACJ and the CCJ are mostly at odds with the professional interests of important social groupings of Central American and Caribbean lawyers. The CACJ has a troubled relationship with business lawyers. Because of the court's broad jurisdictionFootnote 81 and the conflictual regional and national political environments, the CACJ has developed an expertise on constitutional and inter-state disputes rather than Community Law matters. This has led the court to become known among practicing business lawyers as a political and politicized institution, unsuitable to perform the – for them, crucial – role of a regional economic court.Footnote 82

Furthermore, the CCJ has struggled to win favour with a significant part of the Caribbean legal professions. The CCJ has a double jurisdiction (appellate and original). The appellate jurisdiction seeks to replace the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) in London as the apex court of those Caribbean states that were once British colonies. In its original jurisdiction, the CCJ deals with international and CARICOM Law.Footnote 83 These two functions have placed the CCJ in the midst of a professional and generational battle between the older, British-educated Caribbean lawyers – specialized in litigation before the JCPC and generally skeptical of the CCJ – and the younger, locally-educated Caribbean lawyers, who are more inclined to replace the JCPC with a local court of appeal and support the legalization of the CARICOM.Footnote 84 For decades the older lawyers have strongly opposed the CCJ, which constituted a threat to their privileged professional position as Caribbean lawyers practicing both locally and transnationally. This opposition from key members of the Caribbean legal professions has prevented the Court from strengthening CARICOM's de facto supranationality. The CCJ and its legal developments were simply opposed – if not ignored – by too many key stakeholders in the system.

Things are slowly changing, however, since the CCJ initiated a constructive dialogue with the various social groupings of Caribbean lawyers through extrajudicial outreach activities. Moreover, by means of the Myrie case, the CCJ has signaled its intention to create an intersectional constituency of support by satisfying both the interest of the older lawyers in seeing fundamental rights protected and the concern of the younger attorneys in seeing the common market developed.Footnote 85 While Caribbean lawyers are still generally reluctant to engage with the CCJ, these latest developments mark an important shift, which, in the long run, may facilitate the CCJ becoming a more effective engine of supranational integration.

As for legal academia, in Central America there is a general disconnect between academics and the CACJ. Few universities offer specialized curricula on Central American Community Law, with the result that few practitioners and academics have developed expertise in this field.Footnote 86 Moreover, those few institutions dealing with SICA Law do so independently, without communicating with one another. Ultimately, this scattered system of education has hampered the creation of cohesive networks of lawyers ideologically and professionally interested in the SICA, competent to deal with Central American Community Law, and, ultimately, willing to convince other influential elites to take consequential steps in support of the CACJ.Footnote 87

The situation differs in the Caribbean, where the University of the West Indies (UWI) (1940) and its Faculty of Law (1970) have nurtured a generation of lawyers and academics that is more attuned to regional careers and, thus, also to the legalization of the CARICOM. Since its inception, the UWI was organized on a regional level.Footnote 88 This forced students to travel throughout the region to study, thus creating bonds among them.Footnote 89 Moreover, the Faculty of Law has trained students to practice in every jurisdiction of the Caribbean.Footnote 90 Ultimately, most lawyers educated at the UWI ended up supporting Caribbean integration and the CCJ; some of them even sit on the bench of the CCJ today. This fertile academic environment has recently benefited the CCJ, both during and after the Myrie case. The Dean of the Faculty of Law of the UWI, for example, was part of the legal team that defended Barbados. Myrie also triggered a new phase of scholarship on Caribbean law, with publications discussing the new legal developments in journals of local and international regard. Although much remains to be done in order to transform the CARICOM into an effective supranational institution, these latest developments show an increase in the conditions required to transform the CCJ into an effective engine of integration.

4.3. Political factors

Finally, the limited impact of the normative efforts of the two courts on the de facto supranationality of the SICA and the CARICOM is also a consequence of broader political factors. Firstly, the EU-like principles introduced by the two courts clash with the nature and politics of the Caribbean and Central American integration projects. These differ substantially from EU integration. In the EU, regional integration is of a more closed nature, meaning that it is aimed chiefly at tightening economic, political, and legal bonds among its member states. This has made the jurisprudence of the CJEU – especially the principles of direct effect and supremacy – the optimal legal framework for achieving precisely these (internal) goals. Conversely, regional integration in the SICA and the CARICOM is of a more open nature, meaning that both systems are aimed chiefly at equipping the Central American and Caribbean regions with credible institutional arrangements to secure trade with external powers (i.e., the United States, the EU, and the United Kingdom) and to protect foreign investors.Footnote 91 In turn, this outward focus of the Central American and Caribbean integration projects accounts for the relatively limited impact of principles such as direct effect and supremacy, which simply do not fit with the overall purposes of the systems.

The failure of both the CACJ and the CCJ to enhance de facto supranationality in the CARICOM and the SICA is also a consequence of the fact that the idea of Regional Integration through Law (RITL) in Central America and the Caribbean differs from the one developed in the EU. In the EU, RITL has meant Constitutionalisation of Community Law, while in Central America and in the Caribbean, it has taken the form of Community Law with Constitutional Features. The distinction between the two terms is significant. The constitutionalization of EU Law – at least in the early days of the Community – entailed the creation of an apolitical, technical, yet hierarchically strong system of regional norms with precedence over national ones. From here, the prominent role of the principles of direct effect and supremacy, which are substantially neutral principles, was to allow EU Law to have structural precedence over national laws. Conversely, in the Central American and Caribbean regions, the constitutionalization of Community Law has meant the development of thick(er) individual and fundamental rights standards able to provide alternative rights-based regional systems to inefficient national ones.

These particular approaches to RITL are rooted in the specific histories of both systems. In the Caribbean, both the CARICOM and the CCJ were established to complete the process of Caribbean decolonization from the United Kingdom.Footnote 92 The CCJ is a key institution in the Caribbean struggle for independence.Footnote 93 Caribbean decolonization, however, was (and still is) only secondarily linked to the hierarchical superiority of CARICOM Law over national laws. It is, instead, highly dependent on the production of local jurisprudence on human and fundamental rights, both in terms of providing human rights standards and protection comparable to that of the JCPC and remedying the inefficiencies of national judicial systems in CARICOM member states. At the appellate level, this has led the CCJ to rule on the constitutionality of the mandatory death penalty for murderFootnote 94 and indigenous land rights.Footnote 95 At the international level, it has led to the development of a fundamental rights approach to Caribbean Community Law, especially in cases such as Myrie and Tomlinson, in which the Court was called upon to face pressing issues of freedom of movement and LGBT rights. Yet, while developments at the appellate level have generally been well received politically,Footnote 96 the latest developments within the original jurisdiction have raised several concerns. On the one hand, some states (Trinidad and Tobago) voiced concerns about the potential increase in immigration from poorer CARICOM states (i.e., Jamaica and Haiti). On the other hand, some Caribbean lawyers publicly criticized the CCJ for trying to dismantle the dualistic approach to international law that characterizes the legal systems of many Caribbean countries by introducing features of EU Law into the system.Footnote 97

RITL also differs from the EU conception in Central America. This is mainly because both the SICA and the CACJ were chiefly created to pacify and democratize Central America at the end of the Cold War. The CACJ explicitly revived the Cartago Court, a regional international court that was active in Central America from 1907 to 1918.Footnote 98 This has made pacification and democratization of the region one of the CACJ's main tasks. In this case, however, the pursuit of peace and democracy is only secondarily linked to the hierarchical superiority of SICA Law over national laws, while it is mostly related to issues of regional immunities, inter-state conflicts, and separation of powers disputes within the constitutional organs of the member states. It is, in fact, in these three fields that, until now, the CACJ has made its most important contributions. Yet the development of this politicized version of Central American RITL has come at a high price for the Court. This jurisprudence has scared away many business lawyers, who have oriented their practices elsewhere – most notably, towards international commercial arbitration. In the words of one interviewee:

[T]he CACJ is not competent in arbitration and commercial issues. The Court has been focussing chiefly on issues of separation of powers within the States. This has really been its expertise . . . The people at the Court are our friends, but I do not see how . . . you know . . . the clients bring money . . . I believe that, for historical reasons, they have been more focussed on issues of public law rather that private law. From here, my reservations arise.Footnote 99

The pro-integration rulings of the two courts have also failed to foster de facto supranationality as they clash with the overarching structural weaknesses of both the SICA and the CARICOM. In both systems, the member states have conflicting views on regional integration, with some states (El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua in Central America and Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, and Jamaica in the Caribbean) being more committed to regional integration, while others are either more interested in expanding their markets outside the region (Panama and Costa Rica in Central America) or in changing the power and economic structures within the system (the East Caribbean states and Guyana in the Caribbean).Footnote 100

A final but important note on the CACJ. Political instability, the authoritarian drift, and the difficulties in completing the process of democratization of many Central American states have also played an important role in obstructing the CACJ from fostering de facto supranationality in the SICA. Exemplary in this regard is the case of Guatemala, which, despite being a founding member of the court, only ratified the CACJ in 2008 and, until now, has failed to appoint its judges to the court, thus remaining at the margins of the court's activity. The interviews conducted reveal that Guatemala's reluctance to join the court is chiefly due to the enduring interference of several former political leaders in contemporary politics, who perceive the CACJ as a threat to their impunity for the crimes committed during the civil war, regardless of the fact the CACJ is neither a human rights nor a criminal court.Footnote 101 Similar issues have arisen in Nicaragua, when, in 2005, President Enrique Bolaños filed a case at the CACJ trying to avoid a soft coup d’état,Footnote 102 and in Panama, when, in 2010, some members of the PARLACEN filed a case at the CACJ asking the Court to stop the newly-elected President Ricardo Martinelli from manipulating the results of the regional elections.Footnote 103

5. Conclusions

The CACJ and the CCJ have formally reproduced the case law of the CJEU. Yet, they have thus far failed to transform the SICA and the CARICOM into de facto supranational organizations. This, it has been argued, is due to several factors: the lack of independent regional Secretariats; the missing interplay between the two courts and the national judges; the widespread disinterest of lawyers and academics in the two courts; and, finally, the peculiar nature and politics of Central American and Caribbean projects of regional integration.

These findings allow for a re-calibration of the discussion on how RICs can contribute to the development of de facto supranationality in regional systems. The article shows that treaties and judicial decisions granting ‘the right to rule’ to a regional organization do not necessarily translate into effective political and legal integration. Although the Central American and Caribbean regional treaties have rules and judicial institutions similar to those of the EU, and although the CACJ and the CCJ have often reflected the jurisprudence of the CJEU, the SICA and the CARICOM remain largely intergovernmental. This means that design features and activist normative efforts are not sufficient to ensure the development of de facto supranational systems. RICs can thus only foster de facto supranationality when the rulings of a RIC are endorsed by actors in their practice. In sum, RICs are likely to nurture supranationality when their normative activities are supported by a set of institutional, political, as well as societal factors allowing for the effective enforcement of their rulings at the regional and national levels.

Appendix – Interviews Quoted in the Article

Interview 1 – with a lawyer from Trinidad and Tobago

Interview 2 – with a judge of the CCJ

Interview 3 – with a judge of the CCJ

Interview 4 – with a judge of the CCJ

Interview 5 – with a judge of the CCJ

Interview 6 – with a member of the CARICOM Secretariat

Interview 7 – with a judge of the CCJ

Interview 8 – with a Caribbean businessman

Interview 9 – with a Caribbean Law Professor

Interview 10 – with a Central American Law Professor

Interview 11 – with a Central American lawyer

Interview 12 – with a Central American lawyer

Interview 13 – with a Judge of the CACJ

Interview 14 – with a Central American Law Professor

Interview 15 – with a member of the SICA Secretariat

Interview 16 – with a member of the Ministry of Economy of El Salvador

Interview 17 – with a member of the Ministry of Economy of El Salvador

Interview 18 – with a Guatemalan politician

Interview 19 – with a Central American lawyer