1. Introduction

In April 2019, the Japanese government officially legally recognized the Ainu as Indigenous people through the Act on Promoting Measures to Realize a Society in Which the Pride of the Ainu People Is Respected (Act No. 16 of 2019). The law comes with political and financial commitments as well as clear responsibilities distributed across the national, regional, and municipal levels. Does the law hold the potential to challenge and ultimately reform institutions? Or does it rather represent another facet of “cosmetic multiculturalism” (Morris-Suzuki, Reference Morris-Suzuki2018)? While this legal reform may appear encouraging with its set of important promises for the Ainu, the extent to which it can bring change for the Ainu people and respond to their claims and international commitments is questionable in light of institutional constraints. Building on an institutionalist framework, this paper articulates how the governance of the Ainu has been evolving, emphasizing institutional limits and possibilities in the Japanese context, which are simultaneously shaped by and shaping Ainu's activism and individuals both outside and inside the government.

This paper suggests that to better understand Ainu governance, policy and institutional legacies are of great importance. Nevertheless, it would be a grave omission to discuss institutions without incorporating agency into the analysis. First, it is crucial to return to the process through which the Ainu have been colonized and assimilated into the Japanese population to understand how policy legacies have influenced Ainu's activism and subsequent policies. Second, institutional opportunities have mediated the ways that activists have sought to make their voices heard in the political arena. The hierarchical configuration and impermeability of the policymaking process combined with the government's sensitivity to international pressure have prompted Ainu activists to turn to specific political venues, international forums in particular. Key political actors benefitting from political power and resources have also acted as drivers of political reforms. Alliances with political parties as much as personal interests and ambitions intersecting with Ainu's claims at particular times often provided a strategic springboard for reforms.

These policy developments mirror some tensions between gradual institutional change and the confined focus of policy change, shedding light on the contingency and ambiguity of policy change and reforms embedded in ongoing negotiations of interest and a collective identity quest.

2. New institutionalism and policy change

Historical institutionalism (hereafter HI) is rooted in the assumption that institutions, as historical constructs, constrain and affect the behavior of political actors (Steinmo et al., Reference Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992; Pierson Reference Pierson1994; Immergut, Reference Immergut1998). HI analysis posits that institutions are typically characterized by long periods of stability, that are occasionally punctuated. Institutional processes tend to reproduce themselves over time, so change is difficult because institutions are “sticky.” Institutions persist because they are taken for granted and enjoy a high degree of legitimacy (March and Olsen, Reference March and Olsen1984). Generally, HI emphasizes the power of long-term institutional legacies on policymaking and links policy development to the concept of path dependency. Path dependency refers to the idea that possible courses of action are constrained by previous decisions and institutional structures (Pierson, Reference Pierson2000).

More recent developments of the institutionalist theory have attempted to incorporate mechanisms of institutional change into the analysis while retaining the idea of “path dependency” (Thelen, Reference Thelen, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003; Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005). Path-departing change can be caused by external shocks, when incremental reforms alter institutional logic, or in cases of successful legitimization of path departure logic (Pierson, Reference Pierson2000; Béland, Reference Béland2005). As part of these processes, Thelen (Reference Thelen, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003) identified several mechanisms of gradual institutional change, namely conversion (redirection of institutions due to strategic considerations), drift (change of existing institutions due to changes in the environment), layering (introduction of new institutions over or along existing institutions), and displacement (removal of existing institutions and replacement by new ones) (Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005).

Of particular interest for the argument developed in this paper is the mechanism of “layering”. This approach is useful in the sense that it moves the discussion to incremental and endogenous change and points to the importance of studying the accumulation of incremental changes occurring during long periods of relative stability, which can ultimately trigger major reforms (Thelen, Reference Thelen2004; Béland, Reference Béland2005; van der Heijden, Reference van der Heijden2011). Layering “involves the partial renegotiation of some elements of a given set of institutions while leaving others in place” (Thelen, Reference Thelen, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003, 225). It refers to processes of incremental institutional change along which new elements become attached to existing institutions, thereby gradually altering the status or structure of institutions. However, such changes do not necessarily replace or transform institutions. They can add “institutional layers,” such as rules, policy processes or actors, to the old institutions, producing unpredictable transformations (Thelen, Reference Thelen, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003; Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2010). Along the process of “layering,” institutions can be subject to lock-in effects or increasing returns, meaning that each layer consolidates previous institutions (Pierson, Reference Pierson2004). Changing institutions then becomes more difficult or costly (Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005). Layering can also increase the complexity of institutional settings and generate institutional incoherence, thus providing institutional opportunities for actors to seize (Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005; Capano, Reference Capano2019).

An important feature of layering is the role given to actors as agents of change who can actively and strategically contribute to bringing institutional change (Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005). The salience of agency and structure is not sequential. Actors do not just wait for institutional opportunities to open up. Institutions are the object of ongoing negotiation processes where actors attempt to take advantage of institutions by interpreting, subverting, or redirecting them to achieve their goals. In short, actors cultivate change within contextual and contingent opportunities and constraints. In particular, ambiguities and “gaps” in institutional design can provide opportunities for agency and political contestation.

The paper traces the historical process of layering in the context of the expanding governance framework on Ainu issues in Japan. In particular, the focus lies in the mechanisms and impacts of layering on policies and the actions of political actors. Essentially, it is argued that Japan's governance of the Ainu is undergoing a process of layering. Institutional change is limited to some elements within a given set of institutions, yet does not directly challenge them. Path dependency constraints action notably pertaining to the capacity of the Ainu to mobilize effectively in national political arenas. At the same time, capitalizing on international pressure and the presence of policy entrepreneurs inside the government, political agents and groups have attempted to (re)negotiate and (re)interpret institutional rules by adding some new “layers” to institutions and leveraging on institutional ambiguity.

3. The Ainu in contemporary Japan

The Ainu constitute an Indigenous population originally occupying the island of Hokkaido located in the north of Japan, the northern part of Honshu (Japan's largest island), and the Kuril and (southern) Sakhalin Islands. Their precise origin remains opaque and debated by competing theories. Because of the discrimination experienced due to their Ainu identity and the discourse emphasizing the possibility of fully integrating with the Japanese society so as to reach an equal status, the number of Ainu is hard to estimate (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2015). State assimilation policies have been largely successful and widely accepted as a national discourse (Stevens, Reference Stevens2008). Although recent legislative changes may have contributed to raise awareness, Japanese people are for the majority ignorant about Ainu issues and believe in the homogenous myth of the Japanese nation, making Ainu issues not particularly salient in national politics (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2014a). Based on official or associations' estimations, there are somewhere between 20,000 and 200,000 Ainu living in Japan today (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson and Watson2014).

While Hokkaido remains Ainu territory, the Ainu are now found all over the country (Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b). Ainu living outside of Hokkaido have faced a “statistical genocide” in addition to lack of services and acknowledgment (Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b; Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2015). Some Ainu permanently left Hokkaido during the post-war migration period in the 1950s for big cities like Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya, taking up low-class occupations as a result of their social origins and lack of qualifications. Many of them also left behind their Ainu heritage (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996; Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b). Only two government-funded surveys of Ainu in Tokyo have been conducted, one in 1974 and the other in 1988. They focused on the Tokyo Metropolitan region and reported 679 Ainu in 1974 and 2,699 in 1988 (Watson, Reference Watson2010, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b; Uzawa, Reference Uzawa, Gerald, Hiroshi and Virdi2018). Government surveys have often referred to self-identification as a way to designate and record the Ainu population. The 1974 Survey of the Socio-Economic Conditions of Ainu Residents in Tokyo shed a brighter light on the living conditions of the Ainu living in Tokyo including issues of employment, income, housing, and discrimination. Its findings were subsequently used for a campaign for acquiring special financial livelihood provisions from the Tokyo government (Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b). However, by designating Tokyo Ainu as Tokyo resident Ainu, the language of the survey inexorably persisted in maintaining a distinction between Tokyo as just a place of location and a place that could intrinsically be one of identification for the Ainu. The convergence of institutional narratives and material constraints has greatly hampered the development of a collective identity of Tokyo Ainu (Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b).

The absence of Indigenous rights beyond cultural rights participates in creating an environment where being an ethnic minority is a disadvantage and may thus complicate the process of self-identification (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2015). Many Ainu hide their ethnicity to their colleagues, children, and even partners (Council for Ainu Policy Promotion, 2016). Assimilation policies have mandated the Ainu to embrace Japanese names and forego their culture and traditions so they can easily pass for Japanese. Because of the prolonged contact between the Ainu and the Wajin (ethnic Japanese), physical features that were once emphasized as distinct have generally lost their significance as Ainu have mixed with Japanese (Howell, Reference Howell2004). Furthermore, many Ainu living outside of Hokkaido have left the island precisely because they sought to escape the discrimination they experienced there, so are less likely to self-identify as such (Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b; Uzawa, Reference Uzawa, Gerald, Hiroshi and Virdi2018). Many among them are mixed and possess a cultural background largely influenced by Japanese culture and values. In short, Indigeneity means different things for different people and being of Ainu heritage does not necessarily represent the most salient dimension of one's identity today.

In addition to struggles related to identity, culture, and beliefs, historical processes of dispossession and assimilation have had resonance to the present days with respect to the socioeconomic status of the Ainu. A 1994 survey found that the social welfare rate of Ainu in Hokkaido was more than twice as high as the average rate in Hokkaido (Yoshida, Reference Yoshida and Kim2014). According to the 2008 Hokkaido Ainu Living Conditions, socioeconomic gaps persist between Hokkaido Ainu and the Wajin in particular regarding household income, employment, and education (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2015). In 2010–2011, the first survey taking into account more than the region of Hokkaido was conducted. 40.7% of Hokkaido Ainu and 34.8% of Tokyo Ainu had experienced Ainu cultural activities such as learning Ainu language and history, dance, music, carving, or participating in ceremonies. Moreover, the survey found that opportunities for consultation regarding welfare and education were still limited outside of Hokkaido (Council for Ainu Policy Promotion, 2011). The success of the survey remains limited by the very small number of Ainu living outside Hokkaido that had been identified. Only 241 Ainu households and 318 Ainu individuals living outside Hokkaido had been identified, far from the 2,700 recorded in 1989 (Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b).

The Ainu diaspora and issues related to lands have complicated both Ainu activism and government policies (Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b; Uzawa, Reference Uzawa2019). Although bonded by the same historical legacy of oppression and discrimination, Ainu outside of Hokkaido and Hokkaido Ainu are confronted with different issues. The Ainu do not represent a homogenous and monolithic group, which reverberates in the fragmentation of Ainu's claims. While some Ainu demand greater autonomy, land rights, and self-determination, others are more concerned with social and economic rights without questioning the Japanese state's sovereignty. For some Ainu, socio-cultural aspects are the most important to create a sense of belonging in the community. Some Ainu do not engage in Ainu politics, and actively seek to blend in within the Japanese majority and live a “normal” life (Roche et al., Reference Roche, Hiroshi and Kroik2018). The difficulty to rally around a common ground and the coexistence of associations and activist groups with contrasting ambitions has proven to be a challenge for effective mobilization. At the same time, this diversity exhibits the richness of Ainu identity and its plural manifestations, thereby embodying a form of resistance to colonial and assimilationist forces that attempted to muzzle Ainu identities.

Given the multidimensional portrait of the Ainu and the fact that public policy works primarily by reference to target groups, which are social constructions based on stereotypes about particular people (Schneider and Ingram, Reference Schneider and Ingram1993, 335), Ainu governance in contemporary Japan presents many challenges. Maruyama (Reference Maruyama2013) asked the important question, “[w]hy has the Japanese government not recognized Ainu Indigenous rights?”. Nakamura (Reference Nakamura2014a, Reference Nakamura2014b) argued that legal and democratic issues prevent Indigenous rights from being implemented in Japan. In particular, conceptual and constitutional issues regarding the inclusion of Indigenous rights within the Japanese legal framework and the lack of support from the majority population represent important challenges. He further suggested the more accurate question, “[t]o what extent are Indigenous rights being implemented in Japan and why?” to conceptually disentangle the complexities of Ainu policy development. The paths of causation are obviously more complex and multifaceted than what the scope of this paper can cover. The focus of the argument is thus limited to institutional dimensions emphasizing both policy legacies and incremental changes, while accentuating the power of agency.

4. Historical processes of colonization and assimilation

The Ainu culture can be traced back to the mid-12th century (Walker, Reference Walker2006). Originally, the people occupied the north of Japan, namely Ainu Moshir (“the land of the Ainu”), currently known as Hokkaido, as well as the the northern part of Honshu, and the Kuril and (southern) Sakhalin Islands. Active contact between the Ainu and the Wajin started around the 13th century. Interactions were mostly orchestrated by trading and land issues with some inexorable tensions and conflicts regularly occurring. In the 15th century, Ainu groups were living in Ezo (Hokkaido's previous name) as “chiefdoms” (Walker, Reference Walker2006) or autonomous regional communities, distinct from each other, each exhibiting its own social hierarchy and patrilineal leadership (Stevens, Reference Stevens2008). By 1604, Hokkaido was “granted” to the Matsumae clan by the Tokugawa shogunate, which then exercised military subjugation over the Ainu, although the clan technically remained “landless” (Howell, Reference Howell2004). From 1590 to 1800, trade and interactions with the Japanese increased and consolidated relations of interdependence between the Ainu and the Wajin. Contact between the Ainu and the Wajin has thus had a longer history than in North America, which has led to incremental processes of colonial encounters and policies where parties have closely influenced each other (Walker, Reference Walker2006).

4.1 Transformation of the shogunate: the delimitation of territorial boundaries

The transformation of Japan's political system is important to understand the rationale of assimilation policies and colonization processes of the Ainu. The Tokugawa shogunate ruled during the Edo period, which is often characterized by a period of relative isolation from the West from 1623 to 1853 called sakoku. However, this western-centric view is not totally accurate as the Tokugawa shogunate was already starting a process of expansion toward the North (Walker, Reference Walker2006). Prior to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan was ruled by a feudal system of government, characterized by the absence of a central power and the independence of political authority, distributed among 270 autonomous regional lords or daimyos. The Ainu lived in outcast communities autonomous from the mainstream population, but at the same time subordinate to it (Howell, Reference Howell1994). The shogunate progressively attempted to establish a central power that could exercise control over a bounded territory, leading to the establishment of a mixed system of government with centralized and decentralized authorities. The process was incomplete, as autonomous lords and the emperor coexisted with the shogunate. It was, however, the first regime in Japanese history that attempted to establish physical borders for itself (Howell, Reference Howell1994).

It is against this backdrop that the political dependence of the shogunate on the Ainu can be understood (Howell, Reference Howell1994). While the Ainu grew as economically dependent on the shogunate for commodities, the shogunate was politically dependent on the Ainu being subjected and part of the Tokugawa shogunate. More accurately, the Matsumae clan's position within the Tokugawa shogunate was dependent upon the monopoly held over trade with the Ainu. It was thus crucial for the Matsumae clan to maintain clear boundaries, whether ethnic, geographical, or cultural, to distinguish the Ainu and the Japanese as a way to preserve their political power and the economic dependence of the Ainu upon them (Howell, Reference Howell1994).

Japan was not the only one attempting to expand its territory and sovereign power. Russia also sought to expand its holding. Fear of growing Russian influence over the northern islands forced the Japanese government to dedicate more resources to Hokkaido with the goal of delimiting its territorial boundaries. Gradually, the government realized the importance of strengthening Hokkaido economically so it could finance its own defense (Ishikida, Reference Ishikida2005a). The Matsumae clan further emphasized the need to “educate” the Ainu to prevent the spread of Russian influence (Bukh, Reference Bukh2012). By 1854, the Russian threat had decreased notably due to the Treaty of Shimoda (Russo-Japanese Friendship Pact) of 1854, wherein the Ainu were never consulted nor consented (Ishikawa, Reference Ishikawa2003; Abe, Reference Abe2015). Under this treaty, the Ainu were declared Japanese people (Abe, Reference Abe2015). In 1855, the shogunate assumed direct administration of Hokkaido and began a process of assimilation intended to gain international recognition of Ainu's Japanese identity in order to secure territorial rights (Howell, Reference Howell1994). Contrary to North America, where Indigenous policies were primarily concerned with a displacement of population for settlers to occupy the lands, in Japan they were initially shaped by strategic considerations pertaining to national defense (Cornell, Reference Cornell1964).

4.2 The Meiji restoration: modernization and development

After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Ainu land was appropriated as terra nullius under the Land Regulation Ordinance in 1872 (Stevens, Reference Stevens2001). While immigration to Hokkaido was greatly discouraged by the state until the 1860s, things began to change when the Colonization Office (Kaikakushi) was established in 1869. Policies to encourage Japanese migration were implemented, albeit generally with limited success (Cornell, Reference Cornell1964; Maruyama, Reference Maruyama2014). Most of the policies were not meant to chase Ainu out of their lands, and never seriously threatened to do so. It came to be realized that the Ainu knowledge and practices were necessary to the development of the island, especially regarding fisheries and forest industries (Cornell, Reference Cornell1964). The Meiji government began its mission to colonize northern territories and educate the Ainu by setting up a system of local development commissioners (Ishikida, Reference Ishikida2005a). In particular, it was interested in developing the agriculture and modern extractive industries through the stimulation of Japanese immigration to the North, which ultimately led to the disruption of Ainu's livelihoods and natural resources (Cornell, Reference Cornell1964; Maruyama, Reference Maruyama2014). Several policies to restrict Ainu's freedom were enacted, such as the replacement of Ainu's names with Japanese names, the prohibition to practice ceremonies, and a ban on all visible distinctive markers of Ainu's identity, norms, and culture (Ishikawa, Reference Ishikawa2003).

The Meiji Restoration redefined Japan's identity based on Western ideas of progress and modernization and made international law relevant to the political and legal structures of the state. The newly centralized state attempted to assert its authority directly over its subjects (Howell, Reference Howell1994). Ideology of colonization was largely influenced by the position of Japan amidst Western nations. At that time, Japan was still subject to unequal treatment vis-à-vis the West. The West was perceived as civilized in contrast to Japan, which had just begun a process of modernization. For Japan, it was important to maintain a discourse where mobility from the status of “uncivilized” to “civilized” was possible and desirable (Bukh, Reference Bukh2012). Under this logic, although the Ainu were perceived as uncivilized and inferior to the Japanese, civilizing and assimilating the Ainu through education for them to become subjects of the Emperor became an important facet of the country's modernization and colonization policies (Bukh, Reference Bukh2012). Fear of discrimination prompted the Ainu to actively embrace and engage in the process of assimilation and integration into the Japanese society (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996). The dominant discourse further suggested that it was possible for Ainu to “dilute” their inferior blood through marriage (Lewallen, Reference Lewallen2016). The idea that Ainu blood would mingle with that of the Yamato minzokuFootnote 1 and elevate Ainu to progress became widespread, leading to some forms of biological assimilation (Siddle, Reference Siddle2003). Most of the discourses on Ainu assimilation emphasized practical policy issues such as education, health, and employment rather than genetics (Howell, Reference Howell2004).

The state was successful in politically constructing ethnicity while at the same time subjecting it to the political structure of the Japanese state (Howell, Reference Howell1994). Legal and policy documents reflected the fact that the Ainu would soon disappear and were in the process of assimilating to the Japanese nation, a requirement for them to be considered fully equal within the modernizing nation-state. The 1871 Household Registration law considered the Ainu as Japanese subjects, though the latter were still referred to as “former natives” (Lewallen, Reference Lewallen2016). The Ainu were attributed with the status of “former aboriginal” in the process of assimilation from 1878 (Godefroy, Reference Godefroy2019). As a result, they became subjects to taxation and civil and criminal law as Japanese subjects (Howell, Reference Howell1994). This status de facto materialized into the Hokkaido Former Natives Protection Act (FNPA) of 1899, which aimed at “protecting the dying race” (Siddle, Reference Siddle2002), mandating the replacement of hunting and gathering practices with agriculture (Howell, Reference Howell1994; Lewallen, Reference Lewallen2016). The primary concern of the FNPA was tied to land tenure and land use. It guaranteed 5 hectares of subsistence to each Ainu family (these lands were usually very poor in terms of utility for cultivation), although the government still retained legal title over the lands and many requirements were attached to granted lands (Cornell, Reference Cornell1964; Howell, Reference Howell2004). Relocation of Ainu people into “reservations” was meant to control and use the fertile lands for agriculture (Stevens, Reference Stevens2001). Special free schools for Ainu children were also established, serving as a vector for Japanization (Cornell, Reference Cornell1964). By the end of the 1920s, attendance rate of Ainu children was at 90% (Stevens, Reference Stevens2001). Following the implementation of the Act, language as well as Ainu culture went underground or became limited to within households and were rapidly replaced with Japanese language and traditions (Howell, Reference Howell2004).

The FNPA had a major impact on the Ainu community by relocating scattered Ainu households into bigger farming communities for the sake of agriculturization (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996). Except for some small kotan (Ainu village) including Nibutani, one of the best-known Ainu communities in Hokkaido, many kotan in contemporary Hokkaido, such as Shiraoi and Chikabumi, are in fact artificial creations by state policy (Howell, Reference Howell2004). The FNPA was further assorted with benefits including medical expenses, tuition fees for the children, or funeral expenses. These measures were designed to support Ainu who could not benefit from agriculture implements (Howell, Reference Howell2004). Eligibility was determined based on state recognition. In theory, the Ainu were individuals that “anyone would recognize as aboriginal” (Howell, Reference Howell2004, 12), yet in practice this condition was generally tied to the place of residence. Technically, once Ainu left those places, they ceased to be Ainu in the eyes of the state. By linking Ainu's identity and status to residence in rural Hokkaido villages with a majority of Ainu, the state de facto constructed Ainu's issues and politics as a local or as a “regional problem” (Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b; Lewallen, Reference Lewallen2016). It transpires that geographical locations and ethnicity have been created and manipulated by the colonial history, normalizing Hokkaido as a cultural and geographical boundary of the Ainu (Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b).

In short, assimilation and colonial processes were built upon a long history of interaction between the Ainu and the Wajin, deeply anchored in territorial considerations and modernity aspirations. This paper focuses on two policy legacies that prove to be particularly important to examine subsequent policy developments, which are (i) the narrative that equality could be attained through assimilation; (ii) the political construction of the “Ainu problem” as a regional one tied to Hokkaido. These policy legacies generated institutional routine and procedures that constrained and shaped policymaking, limiting the range of policy options considered by policymakers.

5. Policy legacies and mobilization

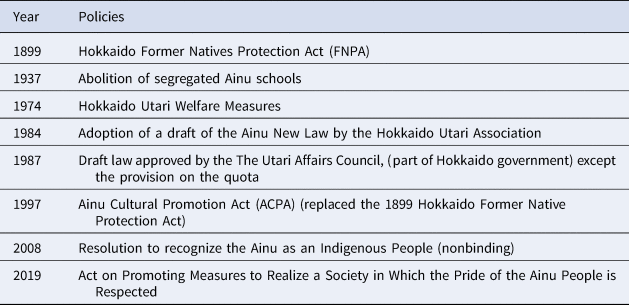

Past policy can consolidate institutions and constrain the development of policymaking by generating a phenomenon of path dependency, thereby making change difficult. Policymakers do not operate in a vacuum but are inextricably intertwined with a social and historical context. Policy legacies deeply affect political institutions and policymaking, which shaped possibilities for Ainu mobilization. However, it would be wrong to believe that the Ainu were solely passive to Japanese institutions and laws (Stevens, Reference Stevens2008). Policy development and Ainu mobilization in the 20th century encapsulate the tensions provoked by the interplay of policy legacies, changing socio-political contexts, and activism inside and outside institutions (Table 1).

Table 1. Reconstruction of the main policies regarding the Ainu

While Ainu activism penetrated political institutions, the Ainu's presence became increasingly restricted as they climbed the governance ladder. The ambivalence of assimilation policies, that is, access to institutional spaces and integration through civil rights, also clearly materialized in Ainu activism and demands (Godefroy, Reference Godefroy2019). Ainu activism remained however complex, characterized by persistent and internal conflicts within Ainu communities and groups, leaving the notion of “public gain” subject to controversies and disagreements.

Ultimately, the Hokkaido government proved to be more responsive to Ainu's demands and lobbying, positing itself as relatively progressive in the face of the national government. The long history of activism and close contact between Ainu in Hokkaido and the government has ostensibly been a driving force in influencing policy developments. Challenges, however, intensified when policy initiatives reached the national level, as fewer points of contact and networks were available to the Ainu.

5.1 Early Ainu activism: between assimilation and welfare

At the beginning of the 1920s, a few individuals belonging to small local collectives began self-identifying as Ainu. Pointing to high rates of unemployment and alcoholism, their claims revolved around the need to abolish segregated systems of education and improving their living conditions. Early Ainu activism thus primarily demanded greater integration to the Japanese society as a way to escape racial determinism (Godefroy, Reference Godefroy2019). Parallel Ainu discourses largely shaped by the state's project to attain modernity emphasized the possibility for the Ainu to contribute to the betterment of the Japanese nation, which would logically undermine the basis of discrimination (Howell, Reference Howell2004). In 1937, segregated Ainu schools were abolished, and Ainu children began enrolling in Japanese elementary schools (Ishikida Reference Ishikida2005b). Early Ainu activism presented assimilation as an effective way to improve Ainu's living conditions. While reflecting dominant state narratives, it also points to the ubiquity of such discourses: Ainu people have re-appropriated them as a strategy for the betterment of their everyday life.

The first Ainu association, the Hokkaido Ainu Association, was formed as an extension of the Social Section of Hokkaido Administration in 1930. The Association changed its name in 1961 to Hokkaido Utari Association (Ishikida, Reference Ishikida2005a) and became an independent office in 1974,Footnote 2 albeit still receiving subsidies from the Prefectural Government (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996). The association was supported by the opposition parties, notably the Japan Socialist Party (JSP) and the Japan Communist Party (JCP). The fact that Ainu issues or the “Ainu problem” particularly elicited public attention in late 1960s was perceived as a strategical issue to be engaged in for those parties. The JSP and the JCP both established special committees for Ainu issues closely echoing the positions of the Utari Association. This synergy de facto strengthened Ainu institutional bases for negotiation with the government (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996).

Early on, the Utari Association lobbied for social welfare measures to be implemented for the Ainu. The Hokkaido Administration introduced the Hokkaido Utari Welfare Measures from 1974 with the purpose of improving living conditions, employment, and education levels of the Ainu. The policy included the construction of public houses and scholarship for Ainu children (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996). Initially, the Utari Association was mostly composed of politically conservative Ainu farmers who engaged in close cooperation with the Hokkaido prefectural government to provide assistance with regard to education and employment (Howell, Reference Howell2004). The Utari Association made clear that its priorities laid in the welfare support for the Ainu of Hokkaido. The measures were limited to Hokkaido, excluding the Ainu that had left the island from any kind of support. Many Ainu found themselves satisfied with their integration into the Japanese society and showed no particular interest in engaging actively in the Utari Association, except perhaps to seek welfare benefits (Stevens, Reference Stevens2008). The Utari Association has de facto served as the major point of contact for the government. It united the Ainu cause but also narrowed the geographical scope, the framing, and the range of Ainu's claims to be addressed by the government.

5.2 Post-war activism: the emergence of a (fragmented) collective identity

In the post-war period, Ainu activism started to progressively forge a collective identity attempting not only to build capacities to dialogue with the government, but also to organize themselves at the grassroots level. The idea of creating a distinct Ainu ethnicity compatible with the imperial nationhood emerged as a plausible enterprise (Howell, Reference Howell2004). The new constitution of 1946 clearly established equality before the law, thus rendering the Protection Act void (Godefroy, Reference Godefroy2019). Several organizations autonomous from the government flourished and attempted to subvert discourses of ethnic homogeneity in Japan (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996; Godefroy, Reference Godefroy2019). Activist discourses emphasizing colonization policies and Ainu suffering, and the quest for recognition as Indigenous people, were not prominent until the early 1970s. These claims surfaced in the political realm due to the salience of Indigenous issues at the international level, but also the rise of national social movements, which incited the construction of an Ainu consciousness (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996; Larson et al., Reference Larson, Johnson and Murphy2008; Bukh, Reference Bukh2012). A new generation of activists started making forays into the political sphere, questioning the assimilation policies advanced by the Utari Association. A movement to recognize Ainu ethnicity and fight against discrimination materialized (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996; Howell, Reference Howell2004; Ishikida, Reference Ishikida2005a). It attempted to build activist bases that were autonomous from the government. It also denounced discriminatory and paternalistic dimensions of the Protection Act, and official discourses amnesic and blind to the traumas caused to the Ainu people (Stevens, Reference Stevens2001). In parallel, the pragmatism of the Utari Association incited its members to cultivate relations with academics, citizens, and politicians from different orientations. While most leaders of the Utari Association were wealthy farmers and businessmen with strong local links to members from the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the Utari Association also maintained institutional affinities with the opposition Socialist and Communist parties (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996).

5.3 Institutional opportunities and legal mobilization

The election of Takahiro Yokomichi from the JSP in 1983 as the Governor of Hokkaido created a more favorable political environment for Ainu's claims (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996). In 1984, the Hokkaido Utari Association adopted a draft law (Ainu New Law). Through this law, the Association advocated for the abolition of the 1899 Hokkaido Former Natives Protection Act that upheld the idea that Ainu are inferior to the Japanese nation (Siddle, Reference Siddle2002). The draft was prepared within the Utari Association by a commission of eight Ainu and two Wajin, a civil servant sent by the Hokkaido Prefecture, and a former editorial writer for the Hokkaido Newspaper (Kawashima, Reference Kawashima2004). The Ainu New Law was relatively progressive, including rights related to political representation and participation at both the national and local level, measures against socioeconomic discrimination, economic benefits based on the idea of compensation for historical dispossession through a fund that would be administered by the Ainu themselves, and the establishment of a national body for Ainu policies (Siddle, Reference Siddle2002; Ishikida, Reference Ishikida2005a; Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2014a). The New Law essentially aimed at reframing the relationship between the Ainu and the state in the context of the rise of international human rights (Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b). It gathered wide support from Ainu all over Japan and became a foundation of Ainu's claims both domestically and at the international level (Siddle, Reference Siddle2002; Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b). Notably, the majority of Ainu associations surpassed their antagonisms to speak in a unified voice and work under a common objective (Stevens, Reference Stevens2001, Reference Stevens2008).

The Hokkaido government was responsive to these demands. In 1984, it established the Utari Affairs Council, which included Ainu representatives, as a response to the request of the Utari Association regarding the enactment of the New Law. The Utari Affairs Council, as part of Hokkaido government, approved the draft law in 1987, except the provision on the quota for the Ainu in the National Diet because of Constitutional violation (Kawashima, Reference Kawashima2004). The Hokkaido assembly then unanimously passed the proposal and sent it to the National Diet for review.

Ainu progressively started to make their way through political institutions, which was crucial for political gains, especially at the national level. Shigeru Kayano began gaining notoriety in the public sphere and rapidly emerged as a key figure of Ainu activism in the political sphere. He first became elected as a municipal councilor of his hometown, Biratori in Hokkaido, before becoming the first Ainu to sit in the Diet in 1994 until 1998 as a member of the JSPFootnote 3 (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996). Kayano actively engaged in a process of lobbying from inside the government for Ainu interest. In November 1994, he made a speech partially in Ainu language advocating for the enactment of the New Law. His presence, as the only Ainu among 600 congressmen/women attracted public attention and participated in diffusing information and awareness about the Ainu to the mass public. In parallel, the Utari Association and the Government of Hokkaido petitioned for the development of legislative protection for the Ainu (Kawashima, Reference Kawashima2004).

The review process of the bill for the New Ainu Law at the national level was painfully slow. However, the Diet did review the bill. These efforts can be linked to Shigeru Kayano having allies inside the Diet, notably Kozo Igarashi, the Chief Cabinet Secretary belonging to the JSP. Despite bureaucratic opposition, Igarashi, a politician originally from Hokkaido and a long-time friend of Kayano, established the Ruling Parties Project in 1994 in charge of reviewing the New Law (Siddle, Reference Siddle1996, Reference Siddle2002). The Ruling Parties Project became an ad hoc consultative agency in 1995 named the Council of Experts on Implementation of Countermeasures for the Ainu People. The Council of Experts, however, did not include any Ainu among its seven members (Kawashima, Reference Kawashima2004). After a year of meetings and hearings, punctuated with trips to Hokkaido, the Council of Experts released a report with the findings on April 1, 1996 (Siddle, Reference Siddle2002; Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b). In the meantime, the Chief Cabinet Secretary had changed in 1996 to Seiroku Kajiyama from the LDP, who became in charge of supervising the development of the report. The report reflected the academic nature of the Council. The limited scope of the recommendations focusing on Ainu culture and excluding issues of rights and compensation was justified based on the ad hoc nature of the Council and the ambitious nature of the reforms. Since revising the colonial legislation was urgent, the Council focused on practical issues and produced a report that could easily become the basis of a draft bill to be passed to the Diet (Siddle, Reference Siddle2002). The report became the basis for the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act (ACPA) of 1997.

5.4 The Ainu cultural promotion act and institutional layering

In 1997, the Nibutani Dam decision recognized Japan's Indigenous Ainu people as a distinct ethnic group. However, its legal certainty and reach were certainly limited by the fact that it was issued by the Sapporo District Court (Hokkaido) and not the Supreme Court. The Ainu Culture Promotion Act (ACPA) was passed three months after the Nibutani Dam decision (Sjöberg, Reference Sjöberg, Willis and Stephen2007). No clear legal definition of Ainu ethnicity was found in the act (Siddle, Reference Siddle2002). While the active promotion of Ainu language and culture found in the Act goes beyond some of the requirements of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, its weaknesses reside in the absence of concepts of Indigenous rights, political rights, and economic rights, restricting its focus to cultural promotion and dissemination (Stevens, Reference Stevens, Hudson, Lewallen and Watson2014). The ACPA established the Foundation for the Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture based in Sapporo and supervised by the Hokkaido Development Agency and the Ministry of Education (Siddle, Reference Siddle2002). Rather than risking the dilution of Ainu issues in the background of political priorities, some Ainu chose to endorse the law, establishing it as a step, albeit small, toward the recognition of Indigenous people in Japan. The law was a disappointment for the Ainu outside Hokkaido who were not considered (Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b). Shigeru Kayano contended that the law was like a seed that would later blossom into a tree of rights (Stevens, Reference Stevens2008, 137). The deceptive outcome eroded the collective impetus and put an end to the short-lived coalition between Ainu organizations of different orientations (Stevens, Reference Stevens2008).

The 1997 ACPA replaced the 1899 Hokkaido Former Native Protection Act. It opened an array of reflections. The ACPA as the first-ever Ainu policy is an important policy reform through which a process of institutional change began taking place. Layering can be pursued by the enactment of rules that can modify ideational structures of institutions. Ideational structures are comprised of ideas, values, assumptions, goals, and programs that structure and organize institutional arrangements (Béland, Reference Béland2005; Capano, Reference Capano2019). They are contextual and contingent, and actively participate in shaping and defining policy problems and solutions. By recognizing a non-mainstream ethnic culture and promoting “multiculturalism” within the nation-state, the ACPA departed from the long-standing homogeneity discourse. By emphasizing and valuing Ainu culture, the Act also contributed to promoting more awareness about the Ainu in the Wajin society. In this respect, ideational elements framing institutional arrangements were partially altered by the new law. Nevertheless, the report of the Expert Group upon which the law was based remained grounded in a nihonjinron discourse,Footnote 4 suggesting that ethnic minorities were still contained within Japan's inherent territories, belying issues of colonial legacies and forced assimilation (Bukh, Reference Bukh2012). Ainu culture is defined narrowly, embracing language, dance, music, and handicraft, thereby depoliticizing and reifying Ainu culture and traditions to the past. Wajin bureaucrats managing the Foundation for the Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture designed the activities of the Foundation without consulting the Ainu. Compared to the Protection Act that proclaimed the Ainu as “dying people”, the ACPA posits a discourse of a “dying culture” in need of protection by the Japanese government. The government's position thereby reproduces paternalistic discourses, making culture “locked into a structure of oppression little different from the days of the official assimilation policy” (Siddle, Reference Siddle2002, 406). Furthermore, Ainu residing outside of Hokkaido were almost entirely ignored by the law, finding at best some implicit mention in the supplementary non-binding resolution attached to the law which recommended the expansion of support for the existing Hokkaido Utari Welfare Measures yet lacked concrete measures (Siddle, Reference Siddle2002; Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b). As such, while some ideational elements were slightly altered, policy legacies still powerfully constrained the development of substantial and meaningful policy change for the Ainu.

6. International leverage, political entrepreneurship, and recognition

National Ainu lobbying has been of limited success for several reasons. Constitutional issues persist. While the Japanese Constitution guarantees individual rights, collective rights cannot be taken for granted. Article 14 of the Constitution posits the equal treatment of all people so that rights can only be implemented to fill the socio-economic gaps between Ainu and Wajin that have been caused by previous government policies. However, it makes it hard to conceptualize Indigenous collective rights (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2015). Moreover, the Ainu officially identified represent less than half of one percent of the Japanese population. As a result, there exists a lack of awareness and education regarding ethnic and Indigenous minorities among the Wajin, and many of them do not understand minority rights (Stevens, Reference Stevens, Hudson, Lewallen and Watson2014; Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2015). The focus on culture has also participated in defining Indigeneity primarily in terms of a reified culture, leaving aside the political dimensions of it. The lack of definition regarding who the Ainu are, or the reliance on individual (self-)identification, also contributes to creating some confusion regarding “who” the bearers of collective rights could really be. Of critical importance is the absence of discussion regarding collective rights, self-determination, and colonialism, which considerably narrows the possibilities for developing truly meaningful and progressive Ainu policies (Watson, Reference Watson2013). These challenges represent some facets of the explanation to why domestic lobbying was of limited use. To explain policy development and analyze the leverage used by the Ainu to push for political change, this paper contends that institutions also matter.

First, state structures provide few opportunities for Ainu to participate in their governance. The Japanese state is characterized by a strong hierarchical bureaucracy (Tsuneki, Reference Tsuneki2012). While it promotes stability in the governance system, it concurrently fragments the democratic process through corruption, a lack of transparency of the policy process, and the consolidation of an integrated network hard to penetrate for outside members (Choi, Reference Choi2007; Larson et al., Reference Larson, Johnson and Murphy2008). Until recently, the Ainu had no legal power or special political status as Indigenous people of Japan. Even in Hokkaido, which had been the locus of Ainu policy development, and at the more local level in the district of Nibutani, which historically hosts a large part of Ainu population, the Ainu do not enjoy any specific authority or rights over the land and resources (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2015). Their capacity to influence higher levels of governance is thus restricted.

Second, the nature and point of contact between the Ainu and policymakers bears the mark of policy legacies. Excessive focus on Ainu cultural promotion and Ainu welfare shaped the substance of contact between Ainu leaders and the bureaucracy, leaving little space for rights claims. The circumscription of Ainu issues to Hokkaido has also translated into the central government transferring responsibility to the Hokkaido prefectural government for administering social support and programs for the Ainu (Larson et al., Reference Larson, Johnson and Murphy2008). Because of this configuration of responsibility, Ainu have had few opportunities to influence national policy and negotiate rights and control over the lands and resources since their main point of contact has been the Hokkaido government. However, policy developments also demonstrate that some of the recent policy advances were facilitated by powerful agents that used the Ainu cause to advance their interests and political commitments.

Given institutional barriers, an effective institutional form of leverage has been gaiatsu. Gaiatsu refers to the idea of “foreign pressure” in Japanese since the Japanese government being sensitive to its international reputation (Lewallen, Reference Lewallen2008; Stevens, Reference Stevens, Hudson, Lewallen and Watson2014). This mode of activism was used to gain recognition as Indigenous people, and currently serves as a vector for Indigenous rights' claims (Stevens, Reference Stevens2008, Reference Stevens, Hudson, Lewallen and Watson2014). With respect to Ainu activism, gaiatsu materialized through Ainu activism mobilizing United Nations (UN) international human rights bodies and events of international scope to put pressure on the Japanese government regarding its human rights policy (Lewallen, Reference Lewallen2008; Stevens, Reference Stevens, Hudson, Lewallen and Watson2014). Through participation in international indigenous forums, Ainu activists have acquired a powerful language to formulate their claims, circumventing the limitations of national lobbying.

6.1 The 2008 resolution and the recognition of the Ainu as indigenous people

In June 2008, the Houses of the Diet adopted a resolution that noted the history of discrimination against Ainu people in Japan and recognized them as Indigenous people of Japan. To understand how this rather unexpected move took place, it is necessary to more closely scrutinize the interactions and power dynamics between the Ainu, the Japanese government, and international organizations.

Since the 1970s, Ainu, including activists from the Utari Kyokai, had built networks with other Indigenous groups at the international level, and presented regular updates of the situation in Japan at the UN. Their voices were amplified by the responsiveness of the Japanese government to pressures resulting from techniques of naming and shaming. For gaiatsu to be effective, the Japanese government must recognize a norm as a minimal standard to be reached by respectable industrialized democracies. Although the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) had existed as a draft for 20 years, it was not formally adopted until 2007. When debates about Indigenous rights arose in Japan in the 1990s, it could logically not be salient enough to initiate change (Lewallen, Reference Lewallen2008; Stevens, Reference Stevens, Hudson, Lewallen and Watson2014).

In addition, July 2008 coincided with the G8 summit in Hokkaido. Strategically, Indigenous groups planned to organize an Indigenous People's Summit in Hokkaido at the same time. They sustained a program on domestic activities and press conferences from December 2007 onwards that effectively harnessed international attention on Japan and the G8, raising awareness regarding the Ainu and Indigenous issues. The Ainu, supported by Hokkaido-based national politicians, including the powerful politician Muneo Suzuki and the leader of the Japan Democratic Party (DPJ), Hatoyama Yukio, called for the establishment of a non-partisan Meeting of Diet Parliamentarians to Consider the Establishment of Ainu People's Rights in March 2008 (Winchester, Reference Winchester2009). Of equal importance to explain the 2008 recognition may have been the advocacy work of the politician Muneo Suzuki, in addition to the Ainu Association, whose insistence may have provided significant pressure on the government. Muneo Suzuki had become a powerful voice in pressing for the recognition of the Ainu as Indigenous people, contrasting with his controversial past. In 2001, he made a statement describing Japan as a homogenous nation where the Ainu had been “largely assimilated” (Lewallen, Reference Lewallen2008). A year later, he was caught in bribery affairs with Hokkaido-based construction companies and forced out of the LDP soon after. While these scandals threatened to put an end to his political career, Suzuki's resilience has aided to restore much of his former influence, maintaining ties to the LDP (Brown, Reference Brown2019). Suzuki created a new party, the New Party Daichi (NPD), and defined himself as a fervent advocate for the revitalization of Hokkaido economy and Ainu issues. Notably, the NPD endorsed the candidature of Kaori Tahara, the first Ainu woman candidate, in the 2007 general elections of the Upper House. From September 2007 to July 2008, Suzuki sent 16 official inquiries to the Diet urging the Japanese government to recognize the Ainu as Indigenous people based on the UNDRIP. Suzuki's move was certainly instrumental to the realization of larger goals and interests. In fact, he believed that granting the Ainu the status of Indigenous people would facilitate the negotiations with Russia regarding the return of Southern Kuriles Islands, which he was involved in (Lewallen, Reference Lewallen2008).

Working in close consultation with the government, the House Members Group for Considering the Establishment of the Rights of the Ainu People began drafting a resolution calling upon the government to recognize Ainu as Indigenous people and reconsider Ainu policy in light of the UNDRIP. As a result of those efforts, parliamentarians came up with a resolution that was adopted by both houses of the Japanese Diet on June 6, 2008 (Lewallen, Reference Lewallen2008; Stevens, Reference Stevens2008; Bukh, Reference Bukh2012). Importantly, the Diet and the Utari leadershipFootnote 5 tacitly agreed beforehand that no discussion on financial compensation or self-determination claims would be held. The resignation to challenge Japan's territorial integrity and sovereignty by the Ainu, in dialogue with the government, may in all probability have facilitated this public recognition (Bukh, Reference Bukh2012; Godefroy, Reference Godefroy2019).

Following the resolution and under the authority of Chief Cabinet Secretary, Nobutaka Machimura (from the LDP), an Advisory Council for Future Ainu Policy was established along the same pattern as in 1995. When he was the Minister for Foreign Affairs in 2007, Nobutaka Machimura, the son of former Hokkaido Mayor, Kingo MachimuraFootnote 6, had expressed some reservations regarding the recognition of the status of the Ainu as an Indigenous peopleFootnote 7 (MOFA, 2007). The 2009 forthcoming general elections (which the LDP ultimately lost to the DPJ) may contribute to explain the timing of the resolution in addition to international pressure. The Advisory Council was mandated to develop a comprehensive policy framework for the Ainu.

In May 2009, the long-ruling party of the LDP was defeated by Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) led by Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama, originally from Hokkaido. As he hailed from a constituency in Hokkaido, the Ainu expected a lot from Hatoyama's election. Days after his victory, Hatoyama met with Tadashi Kato, the chairman of the Ainu Association of Hokkaido, who reiterated the need to develop measures to support his community. In a 2009 parliamentary address, Hayotama appeared clearly committed to building a society free from discrimination and prejudice, and promoting cultural diversity with reference to the Ainu (Kantei, 2009). Hatoyama sat in the Advisory Council, which was constituted by a majority of scholars and politicians including the Governor of Hokkaido, and two members being from an Ainu background (Okada, Reference Okada2012; Tsunemoto, Reference Tsunemoto2019). Following Hatoyama's addition in the Council, the Council submitted its final report in 2009 with recommendations accentuating cultural and social realms (Advisory Council for Future Ainu Policy, 2019). Political issues were only mentioned as mid- and long-term policy issues that need to be studied more carefully, and no systematic participatory process was envisaged. The Council supported the development of a National Ainu Museum and Park (Upopoy) in Shiraoi in Hokkaido focused on Ainu culture and crafts. One of the most notable recommendations posits that Ainu policy initiatives cover the national scope (Watson, Reference Watson2014a, Reference Watson2014b). It is an important step forward for all Ainu from the diaspora, as it brings the long-awaited equality between Ainu in Hokkaido and elsewhere.

To ensure that the government would take responsibility for seeing the measures implemented, the Chief Cabinet Secretary established the Council for Ainu Policy Promotion (CAPP), chaired by himself, in December 2009 as a forum of discussion aimed at reflecting the opinions of Ainu and experts in relevant fields. Five among the 12 members sitting on the CAPP are Ainu. Yet they do not represent an adequate diversity of the different Ainu interest groups or associations, prioritizing groups already sharing close ties to the government.

A second step of ideational layering has been achieved through this resolution, although its extent remains somewhat confusing. By recognizing the Ainu as Indigenous people, the position of Japan regarding its past has been implicitly questioned. However, without apologies or acknowledgment of colonial policy, what it means to be Ainu in contemporary Japan remains incomplete.

6.2 The 2019 legal acknowledgment

Following the 2008 recommendations, a new law was introduced a decade later in February 2019. The minutes of the Ainu policy meeting in December 2018 indicate that no real debate has taken place regarding the content of the proposed bill, which remains vague in its commitment and in the identification of target groups. Yoshihide Suga, current Prime Minister of Japan (2020−), and back then Chief Cabinet Secretary (2012–2020), was heavily involved in the drafting of the 2019 law, and acted as an important architect in the promotion and passing of the bill. Despite being referred to as the “shadow prime minister,” the power and influence of Suga in the political world is undeniable. Occupying a pivotal position in the government, Suga's long-time political commitments involve the revitalization of rural Japan and the promotion of tourism. Pragmatism-oriented, Suga supported the Ainu policy, emphasizing the importance of the tourism industry. During a visit in Hokkaido in 2018, he declared that ““[h]aving the world understand the splendid aspects of Ainu culture will contribute to international goodwill and lead to the promotion of tourism” (Asahi Shimbun, 2019). Along this logic, the law includes the establishment of the National Ainu Park in Shiraoi town (Upopoy). The interest of enacting the Ainu law in 2019 was a strategic move, grounded in a development program aiming at stimulating tourist-based revenue in the perspective of the 2020 summer Tokyo Olympics (Charbonneau and Maruyama, Reference Charbonneau and Maruyama2019). The law was indeed released the year before the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games. In addition to leveraging on Ainu culture for economic benefits, the law also serves the purpose of embellishing Japan's standing regarding Indigenous issues as the world watches (Godefroy, Reference Godefroy2019).

The 2019 law reiterates the necessity to take into account Ainu living outside Hokkaido and develop policies at the national level. All prefectures are further mandated to work toward the development of regional plans to promote and implement the Ainu (cultural) policies. They have an obligation to consult the different parties involved in the implementation. It includes the deployment of measures to promote Ainu's culture and traditions, and to educate the general public about Ainu issues. It also bans discrimination against the Ainu based on ethnicity. Special measures pertaining to the lands and resources are included but solely to protect Ainu culture, thus do not constitute rights per se. The government is also mandated to establish the Ainu Policy Promotion Headquarters in the Cabinet to ensure comprehensive and effective Ainu Policy promotion. The headquarters is to be headed by the Chief Cabinet Secretary and includes relevant Cabinet members such as the Minister of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MLIT) and the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). The law is attached to 660 million yen available to municipalities to fulfill commitments expressed in the law. Among the 16 municipalities that have applied for funding, only one of them is located outside of Hokkaido as of 2019. Although it is expected that more municipalities will apply for funding in the future, this observation presently contrasts with the national scope of the law. Most of the resources are dedicated to tourism, national and international exchanges, and the promotion and preservation of Ainu culture and traditions (Tsunemoto, Reference Tsunemoto2019). Upopoy opened its doors in 2020 in Shiraoi in Hokkaido, thereby freezing Ainu culture a little more into the past and the location of Hokkaido.

6.3 Institutional thickening and path dependency

Both the 2008 resolution and the 2019 law can be analyzed through the prism of layering and, in particular, “thickening” (van der Heijden, Reference van der Heijden2011). Thickening describes a process through which governance arrangements increase in density and complexity. Institutional complexity can be enhanced through the introduction of new actors or institutional bodies (Capano, Reference Capano2019). The development of new governance bodies for the Ainu, such Ainu Policy Promotion Headquarters in the Cabinet has “thickened” institutions. While these achievements certainly coincide with institutional change, they are only layering in the sense that they do not fundamentally alter power relations or the substance of old institutions, for they mostly comprised government members or Ainu members already sharing ties with the government.

These policy developments easily espouse the logics of policy legacies, focusing solely on cultural promotion and symbolic recognition. At the same time, they break from these policy legacies in that they depart from the idea that only Ainu in Hokkaido matter. At least, this is true in the spirit of the law. Concretely, the majority of municipalities that applied for funding to develop initiatives promoting Ainu culture are still located in Hokkaido, as is the museum.

Despite international pressure and reference to the UNDRIP in discussing the development of Ainu policy (Bukh, Reference Bukh2012; Godefroy, Reference Godefroy2019), rights persist in being kept off the agenda. The extent to which cultural promotion and reinvigoration can be substantial without rights attached to it is questionable. The government is still the one in power of defining Ainu culture as the only facet of Indigenous governance, reducing Ainu culture to language, ceremonies, or dances. Dominant narratives are not interrogated, being oblivious to the political and contemporary manifestation of Indigenous issues and Indigeneity, and presenting Ainu culture and identity as things from the past. Without rights, can Ainu really aspire to maintain and create their identity and culture? Can this focus on static Ainu culture in the past alleviate the burdens of the present?

Layering is a strategical means for institutional change as it allows many possible combinations, and can respond to a broad array of stakeholders' demands with contrasting expectations. It is a useful mode of institutional design, as it is possible to combine seemingly progressive policy measures while maintaining the stability of old institutions. In the case of the latest Ainu policy development, policy makers seem mainly interested in the institutional effects of layering. Recent moves were clearly driven by political motivations and gaiatsu. The goals were to exhibit a progressive posture as the G8 summit and the Olympics harnessed international attention. The primary interest of these political moves was presumably to intervene on institutional arrangement without any real interest in the policy outcome for the Ainu. Rather, the Japanese government appeared mostly concerned with preserving the legitimacy of old institutions and serving its own interests. Tensions are conspicuous from these new institutional arrangements. First, although the Ainu are recognized as Indigenous people, policies seem to only define indigeneity based on cultural dimensions. The recognition is thus purely symbolic, as it remains difficult to understand how it will materialize or truly respond to Ainu's demands and needs. Second, without making space in the political sphere for a diversity of Ainu organizations and claims, and sticking to old ties with Ainu endorsing dominant narratives, it is hard to imagine how the Ainu could substantially use institutional change for their own benefits. Finally, the power of international pressure has proved necessary to provoke policy change, yet has been mostly unable to influence its nature.

7. Conclusion

National law today preserves Ainu culture, and the Japanese state recognizes and protects the link between Ainu culture and natural resources and use of land. Ainu are further not only an ethnic minority, but also legally recognized as Indigenous people. These outcomes have been the result of decades of mobilization interacting with and shaping policy legacies and policy development, facilitated by policy entrepreneurs. In particular, narratives of assimilation as a goal or as the inevitable outcome of government policy, and the confinement of the “Ainu problem” to Hokkaido have played a significant role in creating a situation of path dependency that has limited the available choice for policymakers to make policy decisions (Pierson, Reference Pierson2000). Of critical significance has been the friction of domestic and international politics that has opened an array of possibilities regarding the framing of Indigenous issue, and questioned dominant narratives pervading political institutions and imaginations. These processes have gradually eroded policy legacies, at least on the surface. As the phenomenon of path dependency suggests, change is difficult because institutions have the tendency to reproduce themselves. The analysis clearly shows how Ainu policy developments are difficult to deviate from their historical path. Some might argue that it is perhaps too early to accurately assess the nature of policy change pertaining to the Ainu in Japan and the real implications of recent legislative changes.

In light of a historical and institutional analysis, the power of policy legacies is conspicuous. The means of participation for the Ainu in the governance structure are limited by policy legacies that focus on welfare and cultural promotion, which heavily limits the points of contact available for the Ainu to make rights claims. The lack of institutional basis dramatically facilitates Indigenous people's assimilation by the state as they possess no institutional leverage to voice their concerns, nor power to define their past, present, and future. However, it does not mean that no effective strategies exist for the Ainu to engage in transformative and self-determination activities (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2014b; Uzawa, Reference Uzawa2019; Uzawa and Watson, Reference Uzawa and Watson2020).

Furthermore, Japan's institutional arrangements, and in particular the structure of the bureaucracy, contribute to explaining the difficulty of access to political institutions for Ainu activists. Although institutional “thickening” has allowed for the creation of more points of contact for the Ainu, institutional mechanisms still prioritize Ainu that already share connections with the government. These people are less likely to make radical demands or challenge state authority. Policy entrepreneurs that have played a key role in pushing for the adoption of new policies and legislations have often instrumentally utilized the Ainu cause to advance some intersecting political goals.

Institutional layering has translated into both ideational layering and thickening. Prevailing ideas about Indigenous people have been altered, and institutions have sought to accommodate Ainu's claims under international pressure by creating new policy bodies. Implications for Ainu governance are mostly unclear because of the ambiguity and tensions that institutional layering has brought into institutional arrangements. It seems that, at present, two institutional orders coexist, one aiming at maintaining and reinforcing the status quo, the other demonstrating some progressive elements with regard to Indigenous people. These continuous tensions are exacerbated as more institutional layering occurs, the major risks being that this layering creates contradictory dynamics and undermines the functionality of policy in terms of outcomes.

In turn, this tensed layering as institutional design will most likely cause unexpected policy dynamics, further reflecting this ambiguity. Ambiguity can be used strategically as it is illustrated by a recent lawsuit filed by a group of Ainu at the Sapporo District Court over fishing rights on August 17, 2020. Under the current legal framework, Ainu can fish when the activity aims at cultural heritage, based on permission granted by prefectural authorities. The plaintiffs seek to restore their rights to fishing for commercial purposes. This lawsuit is the first action related to Indigenous rights against the central and prefectural government of Hokkaido by the Ainu (Asahi Shimbun, 2020). While it is probable that with a newly acquired legal status, the Ainu will find more points of contact to engage and negotiate with the state, the extent of their success remains uncertain.

Financial support

No funding was received for this research.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest to acknowledge.