Herbert Simon's bounded rationality and Pierre Bourdieu's practice theory have both become pivotal theories of action in International Relations (IR).Footnote 1 Theories of action such as these two constitute abstract models of how individuals process information, make decisions, and behave, applicable to different social contexts and actors.Footnote 2 They are fundamental to the social sciences because they allow social scientists to connect the ‘intentions of persons with macrosocial consequences’ and to ground explanations of change in individuals' actions.Footnote 3 They are for this reason indispensable tools to theorize change within the social world.

In a context where constructivism was long considered to possess no real theory of action and rationalism's reliance on a classic expected-utility model had been heavily criticized,Footnote 4 Bourdieu's practice theory and Simon's bounded rationality were particularly welcome additions. They allowed constructivists and rationalists respectively to address a number of shortcomings in their conceptualizations of action.Footnote 5 Although far from being the only theories of action in use, the gradual adoption of these two by numerous scholars of IR sitting in traditionally opposed theoretical camps make them particularly worthy of attention. And these theories' opposition to one another in fact predates their import into IR. As Simon and Bourdieu rose to prominence in the late 1970s, with the former even winning the so-called ‘Nobel Prize’ in economics, the French sociologist adopted a rather grim outlook on his American colleague's efforts, a mere attempt to correct ‘the inadequacies of a paradigm without every really challenging it’.Footnote 6 In one sense then, their gradual rise and continued opposition within IR is but a new set in a longer game.

In this article, I make two related arguments. The first is that practice theory and bounded rationality in fact share at least two fundamental characteristics. Bounded rationality and practice theory both accept that the way in which individuals process information and make choices varies in social space in the same time frame, that is, synchronically. They also accept that information-processing and decision-making vary in historical time, that is, diachronically. While these two points might be uncontroversial with regards to practice theory on its own, it is my claim that they apply equally to bounded rationality that is likely to raise a few eyebrows, and thus necessitates the most attention. On my reading, bounded rationality is far more than a minor modification of rational choice theory, as Bourdieu would have it. By contrast with rational choice theory and its classic expected-utility model, which assumes that agents always process information about the world and make decisions in the same way, bounded rationality and practice theory do not. For both these theories of action, understanding how agents will process information about the world and make decisions requires some type of empirical investigation. In other words, on their own the assumptions of bounded rationality and practice theory are in fact rather indeterminate. By adopting these theories of action, rationalists and constructivists have therefore moved much closer to each other's positions in ways that have gone oddly unnoticed.

My second argument builds on this first one and proceeds in two steps. To begin with, I note that an important corollary of my first argument is that bounded rationality and practice theory – and through them numerous rationalists and constructivists – accept a common source of social change, that is, change over time in terms of how people process information and make decisions. For international theorists of all stripes, analysing this type of change can provide a crucial insight into large-scale historical transformations in international relations, by grounding macro-level changes in micro-level shifts. And yet, there exists almost no work on this issue, with most scholarship focusing on limited timeframes and exclusively on the post-1945 period. The subsequent step in the argument consists in identifying a way of addressing this absence. Drawing on scholarship in social theory and history, I argue that a particularly useful approach to study this type of change would be to study education, and specifically international practitioners' education (e.g. diplomats, lawyers, and military strategists).Footnote 7 This is because education is one of the key places where new modes of information-processing and decision-making originate, are transmitted, and replaced. Crucially, the study of education allows researchers to examine large groups of individuals across sizeable time periods, instead of limiting them to spatially and temporally highly specific cases.

With these twin arguments, this article makes three key contributions. First, by identifying major similarities among two theories of action widely used in IR and the social sciences, it opens up a space for pluralist dialogue. Rather than seeking to create a new ‘via media’ or attempting to subsume existing work under a new meta-theory, this article underlines shared assumptions and thereby identifies a practical basis for pluralism, a type of work that has arguably been lacking in IR.Footnote 8 In the context of a fragmentation of IR into a ‘camp structure’,Footnote 9 this may be one of the few viable approaches to engage in a discussion across theoretical lines. Second, this article outlines a path to explore empirically the common theoretical ground it identifies, namely through the study of international practitioners' education. The study of education has received remarkably little attention in IR, and yet, it provides an almost unparalleled entry point to study how groups of people learn to think and behave, and how this shifts over time. Finally, by offering a means of analysing changes in the way people process information and make decisions over time, this article makes a methodological contribution to the study of historical international relations. It does so by identifying a new vantage point from which to study large-scale historical transformations in international relations, moving away from the language of norms, values, and identity, towards a more granular examination of how key groups of international practitioners think and act and how this shifts over the long term.Footnote 10

Before I begin, I want to underline two caveats. First, in IR, debates about competing theories of action largely take the form of a discussion about different ‘logics’ of action. This article will avoid such language. While it arguably helps to clarify the differences between various ways of thinking about the determinants of individual action,Footnote 11 this language has tended to reduce the debate to one between an incredibly restricted set of highly stylized ‘logics’,Footnote 12 that is, the logic of consequences, appropriateness, arguing, and practicality.Footnote 13 This limited typology does not adequately capture theories of action used in IR scholarship and beyond. For instance, Bourdieu's practice theory is not captured by any of them; as Vincent Pouliot explains, the ‘logic of practicality’ he developed is only ‘meant to theorize a more specific dimension of social action, namely, nonrepresentational practices’.Footnote 14 As I will show later in this article, the same point could be made with regards to bounded rationality, only very partially captured by the logic of consequences. The rest of this article therefore focuses on theories of action rather than on these logics. The second caveat is that this article does not dwell on the differences between practice theory and bounded rationality, nor does it engage in a comparison of the totality of Bourdieu and Simon's theories, or of rationalism and constructivism.Footnote 15 Rather, my aim is to point out two crucial similarities among theories of action which have become central to rationalism and constructivism in IR theory, and enjoy a great popularity among an array of social scientific fields. I then want to explain why this implies that they agree on the existence of a common type of change in international relations and, in a pluralist spirit, point to a way of studying this type of change.

With this goal in mind, the article proceeds in three steps. The first two sections argue that the assumptions of bounded rationality and practice theory necessarily entail that the way in which people process information and make choices varies first, in social space within the same time frame (synchronically), and second, in historical time (diachronically). The third section argues that because of these similarities, both theories of action recognize a common source of change in international relations, and that in order to study it and capitalize on their convergence, scholars can turn to the study of international practitioners' education. It uses a brief example from the history of international relations to make the case. The conclusion summarizes my two core arguments and their broader implications.

Synchronic variation

This section argues that bounded rationality and practice theory both accept that actors' information-processing and decision-making varies in social space within a similar timeframe, that is, synchronically. Bounded rationality is increasingly popular in IR, though it is not particularly new.Footnote 16 By and large, the idea of bounded rationality is dated back to the 1950s, particularly to the work of political scientist Herbert Simon.Footnote 17 It is sometimes depicted as a minor amendment of rational choice theory. Pierre Bourdieu for instance claimed that it was a mere attempt to correct ‘the inadequacies of a paradigm without ever really challenging it’, while James March and Johan Olsen lump bounded rationality with rational choice theory under the heading of the ‘logic of consequences’.Footnote 18 As I explain below, in so far as bounded rationality accepts that individuals' information-processing and decision-making varies in social space, these assessments are somewhat misleading.

The core assumption at the heart of Simon's idea of bounded rationality is that seemingly irrational action is not only imputable to imperfect or incomplete information, but also to actors' imperfect processing of information.Footnote 19 This is because theories of bounded rationality ‘incorporate constraints on the information-processing capacities of actors’.Footnote 20 Thus, theories that locate ‘all the conditions and constraints in the environment, outside the skin of the rational actor’ are excluded from the realm of bounded rationality.Footnote 21 As Robert Keohane puts it, the ‘source of [actors’] difficulties in calculation lies not merely in the complexity of the external world, but in their own cognitive limitations’.Footnote 22 Based on these insights, all actors are considered ‘satisficers’ rather than utility-maximizers.Footnote 23 The acceptance of bounded rationality, and of the imperfect processing of information as a corollary, implies that social outcomes may in fact be the result of an inefficient use or outright dismissal of information, as opposed to a lack of it.

On its own, the claim that rationality is bounded tells us relatively little. To take an example, some scholars claim that bounded rationality may either mitigate or aggravate distributional considerations when choosing to use, select, change, or create international institutions.Footnote 24 Others disagree as to whether rationality becomes ‘more bounded and imperfect as one move[s] from individual choice to organizational routine’.Footnote 25 The insights used in the framework of bounded rationality are indeed rather broad and open-ended, allowing for the explanation of many different outcomes. In order to understand how actors process information and make choices in a given situation, this theory of action requires us to specify how exactly it is that their rationality is bounded. At the moment there exist two basic ways of approaching the issue, each entailing different views as to whether information-processing and decision-making can vary in social space. The first is based on the insights of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, while the second draws on the earlier work of Herbert Simon. Because of the prevalence of the former,Footnote 26 I shall spend more time dealing with it and discuss it first.

Although bounded rationality can be traced back to Herbert Simon, a great deal of contemporary research based on the notion of bounded rationality draws on work in psychology and behavioural economics, particularly Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky's insights.Footnote 27 In fact, scholars such as Hafner-Burton et al. claim that the ‘origins of the [behavioral] revolution are usually traced to [their] joint work’.Footnote 28 The core insight in this strand of work is the notion that individuals rely on heuristics to process information about the world. These are

‘automatically used shortcuts [that] facilitate the processing of overabundant information by focusing – and thus limiting – people's attention and by supplying simple inferential rules that lower computational costs and allow actors to navigate uncertainty’.Footnote 29

In other words, heuristics are mental shortcuts that enable individuals to process information more quickly and efficiently. However, they can also lead people to misprocess some information or to entirely discard it, when it might in fact be useful. They are thus both constraining and enabling.Footnote 30 One example is the ‘availability heuristic’, which refers to ‘people's tendency to rely excessively on information that is vivid and easily available’.Footnote 31 It leads decision makers to either ‘exaggerate or entirely ignore low-probability, high-impact risks’.Footnote 32 Heuristics such as this one are not consciously selected, but rather put into action and adapted to changing environments.Footnote 33 Which heuristics to select is something that is learnt over time by ‘evolutionary and cultural learning’.Footnote 34

On the face of it, this understanding of bounded rationality does not seem to easily accommodate the notion that information-processing and decision-making vary in social space. This is because it thinks in terms of universals; the heuristics it identifies are meant to be common to all humans. For this reason, it is sometimes said of this type of work that it has identified a ‘laundry list of biases’, but that it remains unclear when they apply, ‘with what magnitude, and whether they [are] in fact constant across agents’.Footnote 35

This universalist orientation has been the object of strong criticism in psychology.Footnote 36 In a widely-cited study, Henrich et al. note that the work of ‘Tversky, Kahneman, and their colleagues’ to ‘demonstrate the existence of systematic biases in decision-making that violate the basic principles of rationality’ tends to generalize findings based on geographically and culturally very limited samples.Footnote 37 Their issue with this research does not pertain to the use of an unrepresentative sample to prove the existence of biases, but rather, it concerns the hasty extension of these findings to ‘people’ in general.Footnote 38 Based on the observation that ‘Western, and more specifically American, undergraduates […] form the bulk of the database in the experimental branches of psychology, cognitive science, and economics, as well as allied fields’, Henrich et al. argue that we are currently unable to disentangle those universal aspects of human psychology from the more ‘developmentally, culturally, or environmentally contingent aspects of our psychology’.Footnote 39 To be clear, the authors do not go so far as to endorse the more radical thesis that denies the existence of any shared traits in the psychology of humans across the world.Footnote 40 But the conclusion they reach is that psychologists need to carry out a great deal more empirical work before claims about universal biases of the kind put forth by Kahneman and Tversky can be properly sustained. And indeed, a number of widely cited studies from the 1990s made more pointed claims about the importance of different cultural conceptions of the self for cognition, emotion, and motivation.Footnote 41 Thus, some of the critiques put forth by psychologists themselves suggest that the way in which individuals process information and make decisions varies in social space at a given moment in time. However, Kahneman and Tversky's scholarship offers unclear theoretical foundations to account for such variation; it is criticized precisely for its failure to acknowledge it.

While some see Kahneman and Tversky's work as ‘both developing and amending Herbert Simon's notion of “bounded rationality”’,Footnote 42 it really only focuses on a restricted dimension of his theory of action. For Simon, who saw his own research ‘both as psychology and sociology’,Footnote 43 there are far more potential sources of bounded rationality. In his view, one could see bounded rationality at work in the ways in which ‘cultural and educational background influence how people approach an “ill-defined” policy problem such as “hunger in a country”’.Footnote 44 By contrast with Kahneman and Tversky, he therefore had no qualms identifying limits to his behavioural findings based on a particular professional or social group, or more broadly, based on particular societies and eras – within which certain stable invariant properties of human behaviour might be identified.Footnote 45 In Simon's version of bounded rationality, information-processing and decision-making unequivocally vary in social space. Although this notion may seem at odds with a view of bounded rationality that sees it as a minor amendment to rational choice theory, it was at the core of Simon's view. This discrepancy between the two strands of scholarship on bounded rationality may explain why studies in political science that draw from Kahneman and Tversky ‘rarely cite work in the Simonian tradition’.Footnote 46

To illustrate the difference between these two versions of bounded rationality and the way in which they deal with variation in information-processing and decision-making, let me use a well-received recent study on investment treaties as a brief example.Footnote 47 This study seeks to explain why developing countries signed many bilateral investment treaties in spite of the fact that they provided no meaningful investment benefits, and that information regarding this fact was widely available. In other words, why did developing countries make an irrational choice despite the existence of easily available information that should have led them to avoid such a choice? Although bounded rationality assumes that all actors are boundedly rational, what the author must explain is the fact that some were particularly bounded, so to speak. His explanation is ‘that the biasing impact of heuristics is […] greater’ for developing countries than for developed ones.Footnote 48 This greater biasing impact of heuristics on developing countries explains why they signed investment treaties that cost them so dearly in terms of sovereignty and provided no clear benefits – all this in spite of the existence of abundant information. But on its own, Kahneman and Tversky's version of bounded rationality cannot account for why developing countries in particular were more prone to these biasing heuristics; in other words, they cannot account for spatial variation in terms of information-processing and decision-making. To do this, the study has to introduce another, more fundamental, underlying factor: a lack of legal expertise in developing countries' bureaucracies as well as high staff turnover, which creates a barrier to learning.Footnote 49 The account of boundedness found in this study thus actually puts the bulk of the explanatory weight not on heuristics, but on the specific kind of knowledge (or lack thereof) of the bureaucracies involved in signing investment treaties. This is a type of explanation that fits squarely within the purview of Herbert Simon's understanding of bounded rationality (on which the author of the study explicitly relies), rather than within Kahneman and Tversky's version. This example thus illustrates the differences between these two versions of bounded rationality and the greater ease with which Simon's accounts for variation in space.

To sum up, while bounded rationality as it is understood in work drawing on Kahneman and Tversky does not easily accommodate the notion that information-processing and decision-making vary in social space at a given time, the Simonian tradition unequivocally does. By contrast with the former, the latter view frames boundedness as stemming from a host of different sources that depend on one's position in social space, such as being part of a cultural or professional group. It is not restricted to universal heuristics of the type identified by Kahneman and Tversky, although it encompasses them as well. The premises of Simon's version of bounded rationality are in a profound sense radically different from those of classic rational choice theory (sometimes also referred to as synoptic rationality) for which information-processing and decision-making are constant across social space.

Practice theory, like bounded rationality, accepts that the way in which agents process information and make decisions varies in social space. In addition, these two approaches have common views as to the origins of this variation. Practice theory, a somewhat recent import into IR theory,Footnote 50 is becoming increasingly commonplace as a theoretical reference point.Footnote 51 Until recently, the practice turn in IR has been ‘almost equated with Bourdieu's work’,Footnote 52 and it remains the most prominent strand both theoretically and empirically. Because of its central place in IR and its popularity in sociology and beyond,Footnote 53 I shall take this instantiation of practice theory as my main object of focus when I use the expression ‘practice theory’ in the next few pages. This should certainly not be taken as a statement that there are no other theories of practice, and even less so as a claim that these other theories are not interesting. This choice is based on the impact that this version of practice theory has had in IR and in the social sciences more broadly.

At the core of practice theory lies the idea that agents act on the basis of a stock of practical knowledge they have acquired over time, and that the act of drawing on this knowledge is often relatively ‘unthought’ or un-reflexive.Footnote 54 Bourdieu calls this stock of practical knowledge ‘habitus’, ‘a system of durable, transposable dispositions which integrates all past experiences and functions at every moment as a matrix of perceptions, appreciation and action, making possible the accomplishment of infinitely differentiated tasks’.Footnote 55 In one of the most cited statements on practice theory in IR, Adler and Pouliot explain that ‘practice rests on background knowledge’, which ‘precedes practice’.Footnote 56 According to them, this knowledge is mainly practical, ‘oriented towards action’, and as a result, should be seen as being closer to skill ‘than the type of knowledge that can be brandished or represented, such as norms or ideas’.Footnote 57 Despite their minor differences, these notions are very similar.Footnote 58 Habitus, or background knowledge, is what allows actors to improvise when they encounter new situations. Their practical sense leads them to draw on this stock of taken-for-granted knowledge and to apply it to new situations. Background knowledge thus ‘regulates the range of possible practices without actually selecting specific practices’.Footnote 59 This is why Bourdieu thought that the habitus was about ‘improvisation within defined limits’.Footnote 60 But this improvisation was always ‘strategic’ for him, a phrase meant to distinguish his theory of action from rational choice's utility-maximizing postulate, but to nonetheless hint at a degree of instrumentalism. As Mérand and Forget note in what is, to my knowledge, the only remark linking the two theories in IR, this argument is ‘at times, surprisingly, not so different from Herbert Simon's “bounded rationality”’.Footnote 61 Indeed, it is difficult to avoid seeing a parallel between Bourdieu's notion of strategies and Simon's idea of ‘satisficing’.

As with the assumption of bounded rationality, the notion that individuals act based on their habitus or background knowledge tells us relatively little about how they will act in any given situation. For this, it is necessary to specify the content of their habitus, just as we would need to specify the nature of an individuals' boundedness. The exact content of any individual's background knowledge will depend on her specific social trajectory. This, however, does not mean that there can be no common features in the background knowledge of large swathes of people. As Bourdieu explains, an individual's habitus is only the ‘structural variation’ of a ‘class habitus’, this variation being the result of the ‘singularity of social trajectories’.Footnote 62 I want to pause here for an instant to make two points. The first observation to make is that a core tenet of Bourdieu's practice theory consists in saying that the content of an individual's habitus (or background knowledge) is common to larger social groups.Footnote 63 Habitus, or background knowledge, is therefore shared. This point is absolutely crucial in the context of international relations where, to take a key example, the analysis of state action necessitates an analysis of groups of people such as diplomats. The second and closely related point I wish to make is that Bourdieu's reference to class is a little restrictive analytically speaking. One could very well examine the habitus of other types of groups, for instance what Weber calls status groups.Footnote 64 In a different vein, in their adaptation of practice theory to IR, Adler and Pouliot make room for a type of group other than class, namely ‘communities of practice’.Footnote 65 Although the nature of these communities is left relatively open, what makes them communities is that the practitioners they comprise share similar background knowledge. It is the diffusion of background knowledge among members of these communities that makes them act similarly and that enables collective practices (e.g. diplomacy).Footnote 66

To illustrate the proximity of bounded rationality and practice theory in terms of how they account for spatial variation in information-processing and decision-making at a given point in time, let me return to the study I used as an example earlier.Footnote 67 To restate its subject, this study sought to explain why developing countries signed a large number of bilateral investment treaties that cost them so dearly in terms of sovereignty, in spite of abundant information demonstrating the absence of any clear benefits. The author's answer was that limited legal expertise and high staff turnover in bureaucracies involved in signing treaties led to a particularly pronounced ‘availability heuristic’, and thus explain developing countries' action. A roughly similar explanation can be produced with a practice-theoretic framework. In this version, the account would centre on the nature of the specific group of bureaucrats' habitus. This seemingly self-sabotaging signing of treaties would be attributed to poor strategic improvisation based on their habitus, namely a ‘matrix of perceptions, appreciation, and action’,Footnote 68 which led them to ignore a type of information that was in fact crucial to the choice they had to make.

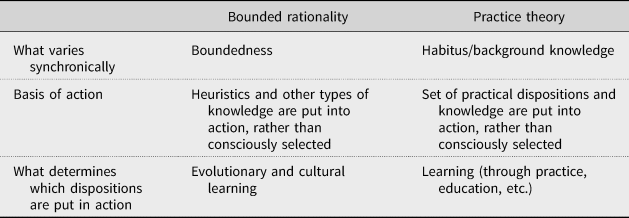

To sum up, Bourdieu's practice theory, like bounded rationality accepts that individuals' information-processing and decision-making varies in social space at any given time. In the framework of practice theory, types of habitus, or background knowledge, vary in social space, while in the case of bounded rationality, the content of boundedness does.Footnote 69 As I explained with regards to Herbert Simon's bounded rationality, types of habitus can also be shared by large social groups (e.g. communities of practice, class, etc.). As in the case of bounded rationality, which holds that heuristics and other types of knowledge are put into action rather than consciously selected, practice theory's habitus is also put into action (‘mis en oeuvre’ in French). In this sense, habit and habitual action are at the core of both approaches. Finally, in both cases, habit is intimately linked to a process of practical learning; which dispositions or practices are used in specific cases will depend on a long process of learning (see Table 1 for summary).

Table 1. Section summary

Diachronic variation

Beyond synchronic variation, bounded rationality and practice theory both accept that the ways in which individuals process information and make decisions varies in time, that is, diachronically. In Herbert Simon's conception of bounded rationality, the imperfect processing of information changes across time. In other words, information is imperfectly processed in different ways, in different epochs. In order to show why this should be so, I shall draw on a famous example from Herbert Simon's writings.

In an article published in the late 1990s, Simon engages in an argument about why economics is and should be a fundamentally historical discipline. After making the case that in many instances, scholars can relax the assumption of full rationality in their models and still produce similar results, Simon delves into the key historical factors to be included in economic explanation, which are inconsistent ‘with the assumptions of neo-classical theory’ and deal with ‘the fact that human rationality is bounded’.Footnote 70 For the purposes of my argument, namely to expose the fact that variation over time in terms of how people process information and make decisions is part and parcel of bounded rationality, I shall only deal with the first of these factors, which is arguably the most important one.Footnote 71 Central to explaining economic change, Simon claims, is an understanding of actors' changing knowledge about economics, by which he means two things. The first is that economic doctrine changes over time; the way in which economists think about the economy changes throughout history – hardly a contentious point. The rise and fall of economic theories imply that economists will process information about the world differently at different points in time. But, Simon explains,

there are, in fact, two histories, more or less parallel: one describing the changes in economic theory espoused by those who studied the subject, taught it, and wrote on it, the other describing the changes of knowledge of the participants in economic affairs, or in the affairs of governments that regulated the economy.Footnote 72

When he speaks about changes in the knowledge of participants in economic affairs, Simon is quite clearly not referring to changes in information, which he discusses later in the text.Footnote 73 To disentangle the two notions, the following analogy is useful. If an actor's mind can be represented with a formula, information will only alter the value of variables, not the formula itself. Knowledge constitutes the formula, namely how the information is processed and what counts as information. Simon's point in the quote above is that, in the same way that economists develop economic theories, all the actors engaged in economic activity, whether consultants or shopkeepers, devise an understanding of how economic life functions, although this understanding will often be of a more tacit type than for economists. The ‘economics’ of lay economic actors may be influenced by professional theory, as Simon notes, but ‘will not be identical with it’.Footnote 74 From this analysis, Simon concludes that a key task in economic history is ‘to trace the changes in popular economic beliefs and assess the effects of these changes upon the behaviour of the economy and the course of state regulation’.Footnote 75 This research programme resembles nothing short of a fully-fledged economic sociology. More importantly, and to return to the initial point, this example neatly showcases how the framework of bounded rationality accepts that people's information-processing and decision-making varies over time, that is, diachronically.

One final point to make regarding Simon's theory of action is that because of its historical outlook, it appreciates the discrepancies that might arise between individuals' ways of thinking and their concrete environment, over time. Indeed, Herbert Simon's conception of bounded rationality was ‘ecological’, in the sense that rationality was for him constituted by ‘the match between mind and environment’.Footnote 76 Consequently, a mismatch would lead to irrational behaviour and choices.

For practice theory, the habitus of actors is not only dependent on their location in social space, but also on the historical moment they live in. It was noted in the previous section that individuals have specific social trajectories. Their habitus (or background knowledge) is the stock of practical knowledge they accumulate in this social trajectory. Needless to say, an individual's social trajectory can hardly stand outside time.Footnote 77 Over time, the habitus of individuals and social groups changes as they come to face new situations and have to improvise, thereby gaining new practical knowledge. It is thus hard to disagree with sociologist George Steinmetz when he says that ‘Bourdieu's main theoretical concepts […] are all inherently historical’.Footnote 78 This is equally true for Adler and Pouliot's notion of background knowledge. Indeed, for them ‘practices’ symbiotic relationship with background knowledge suggests a research agenda on ways that tacit and reflexive knowledge combine in the innovation, evolution, and execution of international practices.Footnote 79 In other words, from their stance, individuals' background knowledge morphs over time and leads to new kinds of practices.

Earlier, I used an example pertaining to Simon's view of economics to defend bounded rationality's acceptance of the historicity of how agents process information and make choices. Let me use a related example then to illustrate the similarity of Bourdieu's position. In his The Social Structures of the Economy, Bourdieu explained that he considered the historicization of specifically ‘economic’ dispositions to be a key task of economic sociology:

Everything economic science posits as given… is, in fact, the paradoxical product of a long collective history… which can be fully accounted for only by historical analysis […]. Against the ahistorical vision of economics, we must, then, reconstitute… the genesis of the economic dispositions of economic agents.Footnote 80

In other words, Bourdieu is urging social scientists to historicize what has come to be seen as the a-temporal hallmark of all economic actors, particularly within neo-classical economics, namely her disposition to introduce economic calculation in all social relations and to cease to perceive economic transactions ‘as governed by social or family obligations’.Footnote 81 Although this historical account of ‘what happened’ may very well need historical verification, Bourdieu's theoretical point is clear. The propensity of economic actors to calculate cannot entirely be denied, but it must be historicized.Footnote 82 Bourdieu's position is incredibly similar to the one Herbert Simon had been developing and expressed almost at the same time.Footnote 83

Finally, as for bounded rationality, the historicity of the habitus means that individuals' practical knowledge may be completely out of tune with the problems they face. It may have been, at an earlier point in time, adequate, but it is not properly geared to their new position within a given field. In such cases, these groups will innovate on the basis of what they do know, but they may very well act in a way that appears totally odd or even irrational to other actors. This is what Bourdieu calls ‘hysteresis’.Footnote 84 For both bounded rationality and practice theory, similar empirical puzzles therefore arise, one example of which is the question of how actors come to develop ways of processing information and making decisions that are at odds with their environment.

To sum up, the frameworks of bounded rationality and practice theory both accept variation over time in terms of how people process information and make decisions. Rationalists and constructivists' growing reliance on these two theories of action means that they have come to share at least two major theoretical assumption, which they did not share before. However, this has gone oddly unnoticed. By moving beyond the identification and comparison of mutually exclusive ‘logics of action’ and turning instead to the comparison of existing theories of action, the last two sections have identified common ground for a meaningful pluralist conversation between two major theoretical camps. What remains to be discussed are the specific implications of this convergence for international theory, as well as the more practical question of how to make full use of this theoretical convergence.

Why theoretical convergence matters: education and the study of change in historical international relations

The arguments put forth in the last two sections imply that bounded rationality and practice theory – and through them a significant number of rationalists and constructivists – both accept the existence of a similar type of change, that is, change in the way people process information and make decisions over time. This kind of change has received insufficient attention in IR. Within the scholarship on epistemic communities, as well as the budding work on communities of practice, there are analyses of how different social groups – many of them scientific, as one scholar notes – process information and make decisions differently.Footnote 85 This is equally true of work drawing on bounded rationality. The first section of this article discussed one such example, in which developed and developing countries, within a similar timeframe, processed information regarding the value of bilateral investment treaties differently.Footnote 86 What is lacking however are contributions that examine variation in time. The very few existing ones focus on short time periods exclusively situated in the post-1945 era.Footnote 87 The dearth of studies examining variation over broad time periods prior to the second half of the 20th century is arguably one of the causes of IR's much-criticized presentist bias, which tends to flatten the past and hinder efforts to better grasp the distinctiveness of the present.Footnote 88

Beyond addressing IR's presentism, one of the most compelling reasons to engage in the study of agents' changing ways of thinking and making decisions over the long-term is that it can deepen our comprehension of large-scale transformations in international relations. Indeed, studying major historical shifts in the way groups of people, such as diplomats, lawyers, economists, colonial administrators and military strategists, process information and make choices, can shed new light on the micro-level mechanisms through which macro-level transformations in the nature of diplomacy, international law, global economic governance, empires, and war, take place.Footnote 89 To take an example, analysing the evolution of economists' background knowledge (or boundedness) in the late nineteenth and early 20th century could help us understand why the practice of comparing distinct ‘national economies’ emerged during the interwar period, and led to the development of global economic governance as we know it today.Footnote 90

What is required to engage in this type of research is a means of studying the origins, transmission, and enshrinement of new ways of processing information and making choices over time. Practice theorists and proponents of bounded rationality currently possess clear tools to study living individuals' background knowledge and boundedness – notably interviews, ethnography, and in some cases, experiments on population samples. However, the same cannot be said about the study of defunct individuals, a problem that research dealing with major timeframes will inevitably encounter. In what follows, I outline a possible path through which both scholars relying on bounded rationality and practice theory might approach this task.

My argument is that the study of education constitutes an almost unparalleled entry point to analyse historical shifts in the boundedness of individuals' rationality or in their background knowledge. By implication, it also constitutes an excellent means of approaching the type of international change I described above. Broadly speaking, education can be understood as including schools and universities, but also ‘informal networks of learning and activity’.Footnote 91 In principle therefore, studying the content of international practitioners' education is a fairly open endeavour, including both professional and quasi-professional types of education. It need not be exclusively concerned with highly formalized training and could range anywhere from a structured university curriculum, to practical manuals, or even a looser form of teaching by competent individuals.

Scholars in neighbouring disciplines already rely on the study of education to understand social change (or lack thereof). Indeed, some of the central figures that inspired practice theorists in IR put education at the core of their analysis of the world, and in some cases, could even be labelled ‘sociologists of education’.Footnote 92 Pierre Bourdieu himself is perhaps the best such example, not least because one of his first institutional moves as an academic was to create a ‘Centre for the Sociology of Education’.Footnote 93 Bourdieu's sociological theory was forged in great part with education in mind, whether it was to draw attention to the role of educational institutions in creating an artificial scholarly gaze, or to reveal the centrality of education in the process of social stratification.Footnote 94 One could turn to the equally towering figure of Michel Foucault, no less interested in the role of disciplines in structuring social practices across entire historical epochs. Nearly all of Foucault's work is concerned with such questions, which means one could potentially cite his whole oeuvre to demonstrate this assertion.Footnote 95 One of the main lights of these thinkers has thus remained hidden under a bushel after their import into IR.

To find scholarship focusing both on education and the question of change in international relations, one must however turn not to social scientists, but to historians. One such example is the work of Donald Cameron Watt. Worried by a tendency to transform historical personalities into ‘coat-hangers or clothes horses’ for attributes and worldviews projected back onto them from the present,Footnote 96 he considered the study of education to be one of the crucial ways into groups of individuals' actual perceptions and dispositions.Footnote 97 This is especially true of his later work. Studying education was one of the means through which he hoped to avoid the ‘systematic repopulation’ of the past ‘with the mental furniture of the present’.Footnote 98 Furthermore, Watt was also chiefly interested in diplomats and other ‘elite’ international practitioners, the ‘Europe of Harrod's customers’ rather than ‘those of Woolworth's’, in his own words.Footnote 99 However, Watt's work does not quite put the type of heavy emphasis on education I am suggesting here.

The scholarship that approaches the type of inquiry I am interested in most closely is really social and cultural historians' work on various groups of international practitioners. Among these historians, some have explicitly framed their work against Norbert Elias' understanding of the relation between education and international relations, as outlined in the Civilizing Process. Instead of emphasizing the impact of social structures (e.g. courts) on the development of education, individual behaviour and affects,Footnote 100 they have attempted to flip Elias' argument around, recasting the ‘system of education and its curriculum as the most important element in the process of civilizing’.Footnote 101 One way of describing the unique feature of this type of scholarship is that they are histories ‘not of international law and diplomacy, but of international lawyers and diplomats’.Footnote 102 They attempt to shed light on key domains of international relations by examining how their practitioners have changed over time.Footnote 103 This is a related but different aim from diplomatic historians' such as Watt, who were more concerned with explaining discrete events, a task they ardently defended against the Annales School. Put differently, these social and cultural historians use the study of education to understand how international relations are constituted, or in John Ruggie's words, to understand ‘what makes the world hang together’.Footnote 104 In some cases, educational change is not only seen as a process that transforms international practitioners, but also as one that produces and empowers new groups of practitioners.Footnote 105 In my view, the underlying insight of all these works, namely that education provides an excellent vantage point to study international change, remains insufficiently exploited in IR.

This methodological point is particularly important with regards to historical international relations, because it deals with dead people. In these instances, which constitute most of the data about human existence, no ethnography, interviews, or controlled experiments are possible. By contrast, the study of education is. One of the tasks ahead for scholars interested in understanding how key groups of international practitioners have historically thought and made decisions is, accordingly, an enormous historical effort to grasp how the content of their education has shifted over time. As I have argued here, this kind of research can shed new light on large scale transformations in international relations, an issue at the heart of international theory, and raise new research questions.

As an illustration, it is worth briefly considering the process that led to a major historical transformation in international relations: the ‘unrestricted mathematical application’ of the balance of power principle.Footnote 106 As noted by a number of historians, the Congress of Vienna (1814/1815) witnessed a ground-breaking diplomatic innovation, namely the application of clear numerical reasoning to calculate and uphold the balance of power in Europe.Footnote 107 More specifically, the value of territories lost by the French Empire was determined by using quantifiable indicators (mainly population), in order to redistribute it and maintain a balance among Europe's powers – a diplomatic practice that remained fundamental to international politics for decades.Footnote 108

With the gradual spread of a new language to describe international politics as relations between ‘powers’ (Macht or puissance) from the mid-18th century onwards,Footnote 109 the institutions teaching future statesmen and diplomats developed a discipline to measure and compare of the power of states.Footnote 110 Although it initially mixed textual descriptions with numbers, it quickly became exclusively quantitative. In the Holy Roman Empire, the law professors involved in this academic endeavour called it Statistik (from the German Staat), an expression thought to have been coined by Gottfried Achenwall in 1749.Footnote 111 This term quickly spread throughout the rest of Europe, as it designated a type of study that was truly innovative.Footnote 112 For instance, in 1798 British political arithmetician John Sinclair explained to his readers that

in Germany they were engaged in a species of political inquiry to which they had given the name of Statistics. By statistical is meant in Germany an inquiry for the purpose of ascertaining the political strength of a country […].Footnote 113

By contrast with Statistik, the older British tradition of ‘political arithmetic’ to which Sinclair belonged seldom engaged in interstate comparison.Footnote 114 This was beginning to change however, partly as a result of the war waged against the French Empire.Footnote 115 The standard presentation of statistical data typically took the form of two-dimensional schemata, which had a horizontal dimension, containing the countries to be compared, and a vertical one, presenting the categories for comparison.Footnote 116 This discipline helped diplomats determine who was a great, middle or small power, as well as to ascertain the value of territory, and to grasp with more accuracy the balance of power in the world.

The link from this disciplinary development to the Congress of Vienna and the mathematical application of the balance of power principle is direct. The men who acted as its transmission belt had all attended the reformed protestant universities of the Holy Roman Empire, at the heart of the development of statistics.Footnote 117 More specifically, the two key figures of the Statistical Commission of the Congress of Vienna – the first ever of its kind – Georg Friedrich von Martens and Johann Gottfried Hoffmann both attended the University of Göttingen's Faculty of Law, where the discipline of statistics had truly taken off.Footnote 118 Prince von Metternich had himself studied diplomacy and law at the University of Mainz's ‘newly founded historical statistical faculty’, and at the University of Strasbourg, where he would have come into contact with statistical work as well.Footnote 119 In 1814/1815, these three men went on to play the leading roles at the Congress of Vienna: Metternich chaired, while von Martens was the general secretary of the statistical commission and Hoffmann directed its technical work.Footnote 120 Guided by von Martens and Hoffmann, the commission imported statistics directly into international relations, leading to the mathematical application of the balance of power principle. Although Talleyrand, the French representative, opposed the notion that the value of territory could be ascertained by the ‘enumeration of souls’ within it as the inhabitants of the Rhineland were not qualitatively equal to ‘Galician Poles’, the quantitative principle triumphed.Footnote 121

The ‘unrestricted mathematical application’ of the balance of power principle in international relations can thus in great part be traced back to an important shift in diplomatic education in the second half of the 18th century. Diplomatic education's integration of what a number of German professors then called Statistik profoundly altered diplomatic actors' background knowledge or, put differently, their boundedness. Over a few decades, diplomats came to think that a new type of information, in this case statistical data about countries and territory, was relevant to their analyses of the world and the way in which they took decisions. In short, educational change led to a diachronic variation in the way diplomats thought and made decisions, thereby altering the nature of peace settlements.

This brief example shows that the study of education offers practice theorists and scholars relying on bounded rationality a new and relatively untapped method to analyse the origins, transmission, and enshrinement of new ways of processing information and making decisions among all sorts of practitioners. In this specific case, it allows us to historicize what is frequently assumed to be a trans-historical way of thinking about international relations. Indeed, scholars across a range of disciplines have long considered the power of states, measured in terms of wealth, military capabilities, population, and the like, to be a fundamental variable to understand the dynamics of international relations. The brief example examined above reveals that European diplomats themselves only began giving serious consideration to this kind of information in the second half of the 18th century, leading to an important shift in the practice of diplomacy. In so doing, the example illustrates the potential pay-off of studying such micro-level changes to shed light on major transformations in international relations.

Conclusion

As I noted at the outset of this article, within the social sciences, theories of action are widely perceived to be crucial to explain change. When the set of theories of action in use in a given field is altered, major implications can therefore follow. In IR, Herbert Simon's bounded rationality and Pierre Bourdieu's practice theory have become key theories of action for opposed theoretical camps, but there has been little reflection the implications of this dual import. Bounded rationality continues to be depicted as a minor amendment to rational choice theory, with both theories frequently lumped under the heading of the logic of ‘consequences’, and practice theory remains regularly opposed to these two, under the heading of the logic of ‘practicality’. By contrast, this article has argued that as theories of action, bounded rationality and practice theory in fact share two fundamental assumptions. They both accept that the way in which agents process information and make decisions varies in social space at a given time (synchronically), as well as in historical time (diachronically). This means that by importing them in the rationalist and constructivist camps, respectively, scholars have inadvertently brought two of IR's major theoretical strands closer together.

A direct implication of the theoretical overlap I identified is that bounded rationality and practice theory both accept a type of change that remains largely under-researched in IR, namely long-term change in groups of individuals' information-processing and decision-making. While a handful of IR studies examine this type of change over brief time frames in the era after the Second World War, the longue durée and the period preceding 1945 remain largely under-researched. To the extent that IR has been repeatedly criticized for its presentism, the study of this type of change provides a potentially fruitful avenue for research. My second argument therefore consisted in identifying a means of studying this type of change, namely through the study of international practitioners' education. Although a number of internationally minded social and cultural historians have followed this path, the insight remains almost untapped in IR. As I sought to underline through an example about the development of balance of power policies, education offers researchers an almost unrivalled entry point to observe the emergence, transmission and transformation of new ways of processing information and making decisions.

By advancing these twin arguments, this article makes three contributions to IR. First, it reveals the fact that scholars relying on bounded rationality and practice theory share common theoretical assumptions, as well as empirical tasks. From the perspective of these two theories of action, determining how different people process information and make choices at different times is indeed an empirical question. One cannot properly define the nature of different actors' background knowledge, or of their boundedness, without reference to some socially situated group and historical timeframe. Thus, rather than emphasizing incommensurability between different logics of action or attempting to create an inchoate theoretical via media, I sought to map out common ground for a pluralist dialogue, which does not require anyone to abandon their prior theoretical commitments. As one observer explains, this practical question of how to engage in dialogue if, as scholars, we are committed to pluralism, is frequently neglected – a task that appears particularly pressing in the context of IR's fragmentation into a ‘camp structure’.Footnote 122

Second, this article identified a relatively straightforward way of analysing the creation, transmission, and evolution of actors' boundedness or background knowledge over time. This task, which ought to be at the heart of studies relying on bounded rationality and practice theory, is typically carried out with the help of interviews, ethnographies, or even experiments. But these methods are difficult to apply to the study of historical international relations, which mostly deals with groups of defunct people. By contrast, the method I identified, namely the study of education, is particularly well-suited for this task. As a result, it offers a clear path to take bounded rationality and practice theory into the realm of historical international relations,Footnote 123 and to engage with strands of international theory that have traditionally accorded a large place to questions of historical change.Footnote 124

Third and finally, the method I outlined here can sharpen our understanding of major transformations in international relations. More specifically, this type of study can help us understand the changing ways in which groups of practitioners such as diplomats, lawyers, and colonial administrators think, thereby shedding new light on transformations in the nature of diplomacy, international law, imperialism, and the like. The example I used in this article illustrates how a close examination diplomats' education could shed new light on the enshrinement of balance of power thinking within diplomatic circles. By contrast with approaches that focus on norms, values, and identity to understand change in historical international relations, this approach shifts the focus towards international practitioners and the seemingly minor figures that design educational curricula and actually teach them.Footnote 125 The ultimate pay-off is thus to put practically-oriented individuals and their concrete ways of thinking back at the centre of our conceptions of major transformations in international relations.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Julia Costa-Lopez, Eric Haney, Edward Keene, Arthur Learoyd, Walter Mattli, Anne McNevin, Lizzie Presser, Sam Rowan, Michael Sampson, Jack Seddon, Claire Vergerio, Tomas Wallenius, Rafi Youatt, Alexa Zeitz and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on earlier drafts. I also thank Stephen Graf for his research assistance.