Introduction

The majority of the available literature on the Jewish community in Hamadan notes that this community was the oldest outside of Israel.Footnote 1 Ephraim Neumark, who traveled through Hamadan around 1885, writes that there were approximately 800 Jewish families (approximately 5,000 individuals) at the time of his visit.Footnote 2 A. V. William Jackson estimates the number of Jews at 5,000 souls in 1903, when he visited Hamadan.Footnote 3 Yarshater introduces Hamadan, along with Tehran, Shiraz and Isfahan, as a fairly large Jewish community in Iran.Footnote 4 An estimated 4,000 to 5,000 Jews lived in Hamadan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, while only 800 were left by the time of Yarshater’s research.Footnote 5 However, Sahim’s informant, Mrs. Shamsi Rahimi, mentions that only 350 were left in the mid-1970s, and not all of them were native Hamadanis.Footnote 6

At present, the community has been reduced to three families, nine persons. Most of the Hamadani Jews have already left the country and moved to Israel and the United States. During my fieldwork in Iran, I found only two people who still speak this language. My main informant in this research is Mr. Nejat Rasad, seventy-four years old, a resident of Hamadan. He is a retired teacher who taught for many years at the Alliance School,Footnote 7 as well as other schools in Hamadan. He now works at the shrine of Esther and Mordechai in Hamadan and provides assistance and information to the tourists who visit the temple. The synagogue at the shrine of Esther and Mordechai holds services on Shabbat and the High Holidays. Hamadan’s Jewish Association is still active and under his direction, and he also offers a Hebrew class.

My second informant for this project is Mr. Bijan Asef. He was born in Hamadan and today lives in Tehran. He is a member of Tehran’s Jewish Association (Anǰoman-e Kalimiyān-e Tehrān). He wrote a manuscript entitled Kārkāsi (Kārkāši), Mād, Hegmatāne, Ekbātān, Hamadān (218 pages) in Persian about Hamadan and, specifically, the Jews of Hamadan. This manuscript was provided to the Jewish community outside Iran, according to the author, and has never been published. In his manuscript, he provides a list of about 250 words, twelve phrases and the verb conjugation of ḫordan “to eat.”

At the time I began my fieldwork, the majority of Jewish monuments in Hamadan had been abandoned. The old bathhouses and Kosher butcher shops were no longer active. The oldest synagogue, a small prayer room located in the shrine of Esther and Mordechai, served as the only active synagogue in Hamadan. The other four synagogues, Kenisa-ye Bozorg (lit. the Big Synagogue located on Bābā Ṭāher Avenue), Kenisa-ye Mollā Rebi (or Rabiʿ), also known as Kenisa-ye Yaʿqub Yāri (located near Darb-e Ḥakim-ḵāne on Kuče-ye Sayyedhā), Kenisa-ye Mollā Abram (located in Pir-e Gorg) and the Alliance Israélite Universelle (also known as Etteḥād) school are inactive, and one was converted into a mosque by the local authorities.Footnote 8 The cemetery in Laleh Park was still intact.

My informants call their language ebri (Persian

) “Hebrew” or zabān-e qadim “old language.” We know that the language is not Hebrew, but it seems that the term ebri is used to define and distinguish it in relation to Persian. The foreign designation of the language is guyeš/zabān-e yahudiyān-e hamedān or guyeš/zabān-e kalimiyān-e hamedān “The dialect/language of Jews of Hamadan.”

The language I encountered in 2019 was different from the language recorded by Abrahamian, Yarshater and Sahim. By the time I began my work in Hamadan, most of the Jews who spoke the language had either passed away or moved to other countries. The fluent speakers of Judeo-Hamadani (JH) are now unfortunately lost, and this dialect can be considered extinct. When Abrahamian carried out his survey in 1936, there were still communities of fluent speakers who passed the language on to their children. By the time of Yarshater and Sahim, there were only a few speakers left, and children were, for the most part, not learning the language. Sahim states that by the time of her research, most of the Hamadani Jews had either moved to Tehran or emigrated to Israel. During her trip to Hamadan to find supplementary material for her research in the mid-1970s, she found very few people who still spoke this dialect.

The death of Judeo-Hamadani is the result of a language shift in which community members no longer learned their heritage language as their first language. The cultural, political and economic marginalization of Jews created a strong incentive for individuals to abandon their language in favor of Persian, the official and more prestigious language of the country. Such a shift can happen when indigenous populations adopt the cultural and linguistic traits of a majority population in order to achieve higher social status and to improve their chances of finding employment, or when they are forced to adopt the majority’s traits in school.

The two remaining speakers of this language inside Iran, namely my informants, learned Persian as their first language, and do not use Judeo-Hamadani in their daily lives. Instead, they use Judeo-Hamadani in an increasingly reduced number of communicative domains.

Due to the influence of Persian, we find language change in phonological, morphological, semantic, syntactic and other features of the language of these speakers. In the domain of the lexicon, any Persian word can be found in Judeo-Hamadani instead of or in addition to inherited forms. The concept of sound changes covers both phonetic and phonological developments. The vowel system has been greatly reduced, and vowels such as ǝ (as in pǝž “to cook”) and ō (as in dōt “daughter”) can only be found randomly in a few words. Even in a relatively short time, one can observe the differences between the pronunciation of various words at the time of Sahim’s work in the 1970s and their pronunciation today.

In the domain of morphology, we find a strong influence from Persian. The use of Persian mi- as the durative marker instead of e- in some verbal forms (as in mi-beyr-ān “I cut,” and ne-mi-zun-ān, instead of na-zun-ān “I don’t know”) and the use of the enclitic copula =e instead of =u for third person singular (as in gorošna=m=e instead of gorošna=m=u “I am hungry”) belong to this group of changes.

The language still maintains an archaic appearance, however, at different grammatical levels. In spite of the relatively small body of academic work about Judeo-Iranian, the language is of great importance for the historical linguistics of Iranian languages.

History of Research on Judeo-Hamadani

Few texts have been written on the subject of Judeo-Hamadani linguistics. The first study of Judeo-Hamadani was completed by Abrahamian in 1936.Footnote 9 His book is a comparison of Judeo-Hamadani and Judeo-Isfahani based on the dialectal features found in the Bābā Ṭāher Quatrains. In addition to this comparison, his book includes conjugated forms of sixty verbs in Judeo-Hamadani and forty-six verbs in Judeo-Isfahani. Abrahamian’s book also includes a short description of phonology and morphology, as well as sample texts in Judeo-Hamadani and Judeo-Isfahani. Yarshater notes the special situation of some Jewish dialects as indicators of Median dialects and offers a number of Median morphological and phonological characteristics of the Jewish languages spoken in the central cities of Iran.Footnote 10 However, Yarshater’s work on Judeo-Hamadani remains unpublished. From Stilo’s contribution, we know that Yarshater made handwritten field notes during research trips to the Jewish communities of Hamadan and Tuyserkan in 1969, and these were made available many years later to Stilo.Footnote 11

The first study focusing specifically on Judeo-Hamadani emerged in 1975, written by Sahim, who wrote her master’s thesis on the language of Jews in Hamadan under the supervision of Bahram Fravashi. In 1994, she published a paper in which she examined some phonetic features and the verbal system in Judeo-Hamadani.Footnote 12 In her subsequent article, published in 1996, she provides a brief overview of the Jewish dialects of Iran, and, as in the work of Yarshater, she discusses selected characteristics of Judeo-Median.Footnote 13

Recent decades have seen a slight increase in related research, and in 2003 the first serious discussion and analyses of Judeo-Hamadani emerged, contributed by Stilo.Footnote 14 The aim of this study was to clarify several aspects of the language of Jews in Hamadan. As a result, the article provides a brief grammatical sketch of the language and is mainly based on data collected by Abrahamian and Yarshater. In his 2008 overview on the culture and language of Jews in Hamadan, Naghzguye Kohan demonstrates a number of phonological characteristics of the language.Footnote 15 In a 2014 comprehensive examination of Judeo-Median dialects, Borjian offers a number of isoglosses across Jewish dialects and takes Hamadani-Borujerdi as a single group. The focus of the present article is the dialectology of Jewish dialects.Footnote 16

The present work contributes to the knowledge about Judeo-Hamadani, especially in the field of historical grammar and typology. I update the findings about the historical grammar of Judeo-Hamadani and consider particularly the article by Stilo.Footnote 17 In addition to the research questions presented here, I have endeavored to provide as many language materials as possible, since, sadly, my recordings will be the last evidence of the language in Hamadan.Footnote 18 My recordings in 2019 suggest that Judeo-Hamadani is heavily Persianized; however, the language still exhibits important archaic characteristics. As the history of Judeo-Hamadani is closely intertwined with other western Iranian languages and the official language of Iran, Persian, it cannot be treated in isolation. In different parts of this work, various characteristics are compared to Parthian, representing the only attested northwestern Iranian languages from the Middle Iranian period. In the second part of the article, an attempt is made to systematically compare the Judeo-Hamadani material with two further northwestern Jewish dialects, namely Judeo-Yazdi and Judeo-Isfahani. Another area of research in this paper is to investigate the possible origins of Judeo-Hamadani.

Historical Phonology

In his valuable work, Stilo details the major North Western Iranian (NWI) phonological developments from proto-Iranian that appear in the Jewish dialect of Hamadan.Footnote 19 In the following, I discuss the historical phonology in greater detail and update some of the findings.

Consonants.Footnote 20

Old Iranian plosives

Word-initial p, t, k are preserved in Judeo-Hamadani, while postvocalic p, t, k yield b, d/y, g.

Examples: p- > p-, e.g. pəž- “to cook” (Prth. paž-, NP paz-); -p- > -b-, e.g. āb (also ō) “water” (Prth. /NP āb); t- > t-, e.g. tāz- “run” (Prth. taž-, NP tāz-); -t- > -d-, -y-, e.g. bud “was, been” (Prth. /NP bud) and vāy “wind” (Prth. wād, NP bād); k- > k-, e.g. kaft “to fall” (Prth. kaft) and kasar “small” (Prth. kas, NP keh); -k- > -g-, e.g. magas “fly” (Prth./NP magas).

Word-initial b, d, g are preserved in Judeo-Hamadani. Word-internal b and g are preserved. Postvocalic d yields y.

Examples: b- > b-, e.g. bud “was, been” (Prth./NP bud); -b > -b, e.g. xomb “jar” (Prth. xomb, NP xom(b)); d- > d-, e.g. dandān “tooth” (Prth./NP dandān); g- > g-, e.g. gōv “cow” (Prth./NP gāw); -d- > -y-, e.g. šuy- “to wash” (Prth. šōδ, NP šuy), vāyōm “almond” (NP bādām) and kiye “house” (MPrth., MP kadag, in NP kade).

Old Iranian fricatives and affricates

Old Iranian f and x seem to be preserved in Judeo-Hamadani, while postvocalic θ yields h.

Examples: -f- > -f-, e.g. nāf “navel” (Prth. nāfag, NP nāf) and kaf “foam” (Prth. kaf, NP kaf); -θ- > -h-, e.g. rāh “road” (Prth./NP rāh); x > x, e.g. xar “donkey” (NP/MP xar) and šāx “horn” (Prth./NP šāx).

Word-initial Old Iranian č is preserved, while postvocalic č yields ǰ or ž. The occurrence of both voiced and voiceless consonants as output is surprising.

Examples: č- > č-, e.g. čin “pick, gather” (Prth./NP čin); -č- >- ž- / -ǰ-, e.g. riǰ “to pour” (MPrth. rēz, NP riz) and vāžār “market” (NP bāzār).

An archaic characteristic of Judeo-Hamadani is the preservation of Old Iranian ǰ.

Example: ǰ- > ǰ- and ž-, e.g. ǰan/žan “woman” (Prth. žan, NP zan).

The only attested example of *-ǰ- in postvocalic position in my corpus is derāz “long” (Av. darǝγa-, NP derāz), which may have been borrowed from Persian.

Old Iranian s and z

Non-Persian Old Iranian s in initial position is preserved in Judeo-Hamadani.

Example: s > s, e.g. suǰ- “to burn” (Prth. sōž-, NP suz-).

In postvocalic position, it may be preserved or yield h.

Examples: -s- > -s-, e.g. ris- “to spin” (Prth. ā-rwis-, NP ris-); -s- > -h-, e.g. āhan “iron”Footnote 21 (Prth. āsun, NP āhan)Footnote 22 and rubāh “fox” (Prth. rōbās, NP rubāh).

Old Iranian z (PIE *ǵ(h)) is preserved in Judeo-Hamadani, as in zun “to know” (Prth. zān, NP dān).Footnote 23

Proto-Iranian *θr yields r in Judeo-Hamadani as in pir “son” (Prth. puhr, MP pus). In Judeo-Hamadani, as in many NWIr. languages, PIr. *śṷ yields sp, such as in espid “white” (Prth. ispēd, MP sefid).

The only example for proto-Iranian *źṷ is the word zovun “tongue” (MPrth. izβān, MP zabān), showing a typical NWIr. development.

Old Iranian š, irrespective of the PIE origin, seems to be preserved in Judeo-Hamadani.

Example: šur “salty” (Prth. šōr, NP šur) and miš “mouse” (NP muš).

Old Iranian h is preserved in ham “also” (Prth./NP ham), while it yields x in xā “sister” (Prth. wxār, NP xwāhar).Footnote 24

Old Iranian sonorants

The Old Iranian nasals m and n are preserved in Judeo-Hamadani, such as in mi “hair” (MP. mōy, NP mu), nim “half” (Prth. nēm, NP nim), ništ-Footnote 25 “to sit” (MPrth. nešiδ, NP nešin) and vin- “to see” (Prth. win-, NP bin-).

Old Iranian r is likewise preserved, e.g. ru “day” (Prth. rōž, NP ruz) and berā “brother” (Prth. brād, NP barādar).

Word-initial ṷ- is preserved, e.g. vin- “to see” (Prth. wind-, NP bin-), vāy “wind” (Prth. wād, NP bād), vārun “rain” (Prth. wārān, NP bārān) and veče “child” (NP bače).

Old Iranian aṷ# yields ō, e.g. in tō (Prth. tō, NP to), and with a further development of ō to ē(y) in ǰēy “barley” (NP ǰo). Postvocalic ṷ in other contexts would also show the loss of ṷ, e.g. yey “one” (Prth. ēwag, NP yek).

Old Iranian *![]()

![]()

Consonant clusters

Stilo states that Old Iranian ft is represented only by -ft: geft- “take,” kaft- “fall” and dor-oft- “sleep.” However, it seems that it can be changed to -(h)t ∼ -(t)t in Judeo-Hamadani, as in rōte “gone” (NP raft).

Old Iranian -xt, usually parallel to -ft, yields -(h)t ∼ -(t)t, e.g. sot- “burned” (NP suxt-) and pet “cooked” (Prth./NP poxt-).

Old Iranian xš- yields š, e.g. ši “night” (Prth./NP šab), šost “washed” (Prth. šust, NP šost) and fraš- “to sell” (NP foruš).

The verb dor-os- “to sleep” (Prth./NP xusp-) shows the loss of Old Iranian hṷ- in the initial position of the verbal stem -os. Other examples exhibit typical developments of Persian, namely the change of *hṷ- to x, as in xon- “to read” (Prth. xun, NP xwān), xor “to eat” (Prth. wxar, NP xwar) and xoč “own” (Prth. wxad, NP xwad). The product of OIr. š![]()

OIr. rn yields r in Judeo-Hamadani, e.g. biri- “cut” (NP burr) and xri- “to buy” (Prth., NP xar).

Vowels

Old Iranian short vowels are usually preserved, e.g. xoč “own” (Prth. wxad, NP xwad), čin “pick, gather” (Prth./NP čin) and suǰ- “to burn” (Prth. sōž-, NP suz-). Judeo-Hamadani pəž- “to cook” (Prth. paž-, NP paz-) exhibits the development of a > ə. Old Iranian short vowels can be elided in word-initial position in polysyllabic words, e.g. vā “open” (Prth. abāž, Persian bāz), but not in hāmā “we” (Prth. am(m)āh, Persian mā). In hāmā, the -a- has been lengthened to -ā- and an h- has been added.

OIr. ā seems to be elided in y- (NP āy).Footnote 26 It is preserved in vāy “wind” (Prth. wād, NP bād) but changed to u in zun “to know” (Prth. zān, NP dān). As in Persian, ā becomes u when preceding nasal consonants, a later development. OIr. i remains stable, e.g. di (Prth./NP did). Original *u, is generally fronted to i, for example in tit “berry,” pir “boy, son,” dir “far,” ri “face,” did “smoke,” āli “plums,” gerdi “walnut” and xin “blood,” and is even found in Arabic loanwords, e.g. tifān “storm,” āris “bride,” sābin “soap,” sātir “cleaver” and qebil “accept.”

PIr. *ṛ is changed into ar in labial contexts, e.g. bart (Prth. burd, NP bord), mart “died” (Prth. murd, NP mord) and pars- “to ask” (Prth. purs-, NP pors-), and in neutral contexts, e.g. tars- “to fear” (Prth./NP tars) and kart “did” (Prth. kird, NP kard), but ker- (Prth., kar-, NP kon-). There is ir in palatal contexts, e.g. gir- (Prth./NP gir).

Diphthongs

The OIr. diphthong ai- comes out as i, e.g. nim “half” (Prth. Nēm, NP nim) and riǰ “to pour” (MPrth. rēz, NP riz). The OIr. diphthong au- comes out as u, e.g. ru(ž) “day” (Prth. rōž, NP ruz), suǰ- “to burn” (Prth. sōž-, NP suz-) and šuy- “to wash” (Prth. šōδ, NP šuy).

Phonology

The consonantal system of Judeo-Hamadani is very similar to Persian and has the following inventory: /p, b, t, d, č, ǰ, ž, k, g, q∼γ, f, v, s, z, š, x, h, m, n, r, l, y/. No other sources introduce the consonant ž. Examples of this consonant can be found in žan “woman,” pǝž “to cook,” ruž “day” and vāžār “market” in my materials.

Stilo mentions that Yarshater’s notes also show a pharyngeal H, especially in Hebrew and Arabic words, and mentions that no other sources show this consonant. Even in Yarshater’s notes, it occurs in very few words. My main informant, Mr. Rasad, clearly uses pharyngeal consonants (/ħ/ and /ʕ/) in Hebrew and Arabic words, such as bet ħayyim “cemetery,” ʕeynō “Friday,” moʕed “festival” and ʕeyn “eye.”

The vowel system of Judeo-Hamadani has the following inventory: /i, e, ə, a, u, ō, o, ā/. Stilo states that ə is probably a variant of e.Footnote 27 Vowel ə can be found in dǝmāq “nose,” bǝrāt “for you,” pǝž “to cook” and kārǝm “my work.” Vowel ō occurs in dōt “daughter,” sō “apple,” ōlbālu, ōbālu “sour cherry,” dōle “water vessel,” vāyōm “almond” and raxtexō “bedding.” I am not yet positive about the existence of å (between ā and o); it seems to occur only in šålom “hello.”

Judeo-Hamadani’s suprasegmentals, including intonation, tone, stress and rhythm, have been strongly influenced by the current Hamadani dialect.

The most common diphthongs in Judeo-Hamadani from my corpus are: āā as in šāā “hour”; ao as in naon vāt “Didn’t I say?”; uā as in kuā “where” and buāyān “I would say”; ayi as in bet ħayyim Footnote 28 “cemetery”; āy as in vāy- “to say,” āyu “today,” āymi “human,” kāy “straw” and vāyōm “almond”; ey as in ʕeynō “Friday,” heyz (in Persian

) “a centrally positioned symmetrical axis pool in traditional Iranian houses” and keyčiz “ladle”; iye as in kiye “house,” vābiye “becomes”; av as in havā “air,” davā “fight,” maviz “rosine” and yavāš “slowly”; āv as in sāvun “soap”Footnote 29 and undāv “there.”

Lexicon

It is imaginable that the Judeo-Hamadani lexicon contains a considerable number of Hebrew words. Most of these loanwords form the bulk of the words concerning religion and religious practices. Hebrew loanwords have undergone several changes that were common in the JH language itself over the years. These changes influenced the loanwords and changed their semantic, structural and more or less morphological meaning, and even their phonetic appearance. Later, a number of Hebrew loanwords were assimilated into native JH and came to be acknowledged as pure JH. Most of the Hebrew loanwords indicate events, objects and ideas associated with religious services and cultural affairs: tām “salt,” ketubā/ketibā “marriage, marriage certificate,” tāmme “impure,” moʕed “feast,” taʕnit “fasting,” haqālā “cleaning the copper dinnerware with boiling water,” masā “Matzo,” haliq “a paste,” lahmā “bread,” bet ħayyim “cemetery” (lit. house of life) and the names of days—šābāt “Saturday,” ye-šābāt “Sunday,” do-šābāt “Monday,” se-šābāt “Tuesday,” čār-šābāt “Wednesday,” pan-šābāt “Thursday” and ʕeynō “Friday.” A number of words, such as lāšun “tongue,” ʕeyn “eye” and feste “pistachio,”Footnote 30 do not directly reflect a religious trace.

Contact with other languages, such as Hamadani and Turkish, have also left traces, which provide interesting insights into the external history of the language as they reflect cultural influence from further afield. Numerous common words between current Hamadani dialect and JH can be found in the names of objects associated with the house and household, such as giǰin “threshold,”Footnote 31 seyzun/seyzān (Hamadani seyzān)Footnote 32 “cellar,” dulō/dulāb (Hamadani dulābe) “closet,” qafā (qofā Footnote 33) “a kind of basket,” lānǰin “a kind of clay pot,”Footnote 34 tandir “oven,”Footnote 35 tiyānče “a small pan”Footnote 36 and mafraš (originally an Arabic word, which has been used in Turkic varieties inside and in the surrounding area of Hamadan) “a kind of blanket for packing bedding.”Footnote 37

The term māqāš “kitchen tongs” (alternatively maqāš, maqqāš, derived from manqāš) is originally an Arabic loanword, but it is also attested to in Hamadani and JH. The term venadig (Hamadani venedig) “window glass,” comparable to German Venedig “Venice,” also appears in Hamadani.Footnote 38 It is imaginable that this word refers to high quality glass from Venice, which was probably imported to Hamadan and used for windows.

The second group of Hamadani words in JH are body parts, such as omme/ome “buttock,”Footnote 39 and family members, ene zāye “step-siblings.”Footnote 40 The names of regional plants and foods of Hamadan also occur in JH, such as varak “Alhagi,” tiq do-rāq/tiq dolāq (originally tiq duq rāq)Footnote 41 “a Hamadani dish made with Spear thistle and yoghurt drink” and yaxni “a Hamadani dish consisting of a stew made with bone marrow, potatoes, and beans.”

The words dasgirāni/dastgiruni “engagement” and xāzmeni (NP. xāstegāri) “marriage proposal” in JH are also attested in Hamadani.Footnote 42

A number of Turkic loanwords, such as yuz “walnut,” qāb qoǰāq “kitchen dish” and qazqun “large copper pot,” can also be found in JH either transferred through Hamadani or due to direct contact with Turkish speakers in the region.

Morphology

Nouns

Substantives in Judeo-Hamadani are very similar to those in Persian. In both of these languages, substantives have no distinction of grammatical gender. There are two numbers, singular and plural, and there is no distinction between the direct and oblique case. The postposition rā/ro and its variations ā and o mark definite direct objects:

Variants ā and o appear after consonants:

The plural suffix -(h)ā is used on substantives to indicate both animate and inanimate, for example, žan-ā “women,” veče-hā “children” and mes-ā “coppers.”

There are two indefinite markers that occur either separately or together: ye(y) “one” and an unstressed -i. Both forms most commonly occur together:

Comparable to Persian, modifiers in Judeo-Hamadani follow the noun and are generally connected by an Ezafe particle, for instance, kiye-y-e to “your house,” madrese-y-e āliyāns “Aliyans school,” nesf-e šeyu “midnight,” sāl-e emi “next year” and pir-e kākol zari “a golden topknot boy.”

Pronouns

In Judeo-Hamadani, similar to Zoroastrian Dari and a number of other Central Dialects, the historical oblique forms of pronouns have been generalized, and a distinction between direct and oblique case cannot be observed.

The independent forms of personal pronouns in JH are very similar to those in Persian. There are only two differences. The first difference is the -ā- vowel in mān “I.” The second difference is the form hāmā “we” as opposed to the Persian mā. The form hāmā can also be found in Maḥallāti and Kᵛānsāri, Kāšāni and Isfahani dialects.Footnote 43

As a result of the simplification of the case system between Old and Middle Iranian, the use of pronominal clitics largely increased in Parthian and Middle Persian as well as in contemporary western Iranian languages in order to compensate for the deficiency of earlier distinctions.Footnote 44

In comparison to the Old Iranian pronominal clitic system, in which there was a distinction between accusative, genitive/dative and ablative forms, many Middle Iranian and contemporary Iranian languages instead have only a single pronominal clitic form, i.e. oblique, for all these cases. It must be noted, however, that some contemporary western Iranian languages, such as northern Kurdish, Zazaki and Sangesari, do not have such pronominal clitics.Footnote 45

In JH, similar to Persian and some additional languages, the pronominal clitics for the singular are derived from the Old Iranian genitive/dative pronominal clitics, e.g. 1sg. -om/am < OP -maiy, 2sg. -ot/od < OP -taiy and 3sg. -oš/aš < OP -šaiy. The JH pronominal clitics for the plural consist of the singular forms with the inclusion of the plural suffix -ān. In addition to this group, certain Iranian languages also have forms deriving from the Old Iranian accusative forms, for example, Sogdian and some Sorani dialects.Footnote 46 The JH pronoun forms are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Personal pronouns in Judeo-Hamadani

a V means vowel.

It must be noted that the clitic pronouns are used as agreement markers in past transitive constructions:

As Stilo observes, clitic pronouns are quite mobile in JH and there is a general tendency for them to move forward, particularly to the left, even inside the verb whenever possible:Footnote 47

Demonstratives in JH are in “this,” un “that” and hamin/hamun “this/that very (same).” The plural forms are inā “these” and unā “those.”

Reflexives are xo(č)- + clitic pronouns: xoč=am, xoč=at, xoč=aš. It seems that /č/ drops before plural clitics: xo=mān, xo=tān, xo=šān. For example, xoč=at zun-i “You know yourself” and barāye xoč=aš “for himself.”

Verbs

Lexical preverbs

The most common preverbs found in JH are he-, vā and vor-, which precede the verb. The preverb he- (< *frā) is attested by these examples: he-niš “sit!,” he-ne-gir “Don’t buy (it),” he=d-gefte “you have bought” and he-de “give (it)!”

Stilo identifies how Judeo-Isfahani and the dialects of the immediate Isfahan area have an i- ∼ e- preverb instead of JH he-, as in i-gi(r) “take, get,” i-ni “sit,” e-tā “give” and e-n- “put.”Footnote 48

The preverb vā- occurs in these examples: vā-pars “Ask!,” vā-puš-ān “I put on,” vā-nǝ=m-nevešt “I didn’t write,” vā-ker-ān “I open” and vā-n-eysāy-ān “I didn’t stand.” The preverb vor- is found in vor-os “rise, stand up.” In some cases, preverbs do not create any change in the meaning of the root, but sometimes, for example in the instance of vā-ker-ān “I open,” we find a total meaning change. In JH, preverbs precede the negative particle, the clitics and durative particle and always occur in the initial position:

The verbs “to be.”

The enclitic copula in the present is identical to the verbal suffixes (Table 2):

Table 2. Enclitic copula

In addition to the enclitic copula, there are two additional “to be” forms, namely “to be” of existence and “to be” of location, consisting of the preposition der and an enclitic copula (Table 3).

Table 3. Present form of the verb “to be”

Tenses

The present and imperfect tenses are formed with a suffixed and unstressed e-, also called the durative marker, as in e-ker-u “makes, does.” Very often in word-initial position and after ā in internal position, e- seems to be elided: vāy-u “he/she says.” The durative prefix mi- appears only very occasionally and is clearly the result of Persian influence, e.g. mi-beyr-ān “I cut.” The prefix be- is used in JH to form the subjunctive (be-š-im “we would go” and be-kr-i “you would do”), imperative (be-gir “take it!”), preterit (be=m-vād “I told”), the present perfect tense (be=m-e-šnofte “I have heard”) and the past perfect tense (be=m-xorte bo “I had eaten”).

The progressive tense seems to be formed on the basis of the colloquial Persian construction with the modal verb dāštan, e.g. mān dār-ān bar-gard-ān az kenisā “I am returning from synagogue.” The secondary preterit suffix *ā(d) is attested in JH, e.g. zun-ā(d) “knew” and pars-ā(d) “asked.” The causative marker en is attested in JH, as mentioned by Stilo in béxandene “make (someone) laugh!”Footnote 49

Similar to a number of NWIr. languages, JH also has the present stem structure, which is identified by a suffix -n- or -nd-, as in vin- “to see.”Footnote 50

The Historical Background and the Origins of Judeo-Hamadani

The dialect spoken by the Jews of Hamadan, similar to the Jewish dialects of Isfahan, Kashan, Borujerd, Yazd, Kerman and others, has been described as belonging to the Central Dialect group of northwestern Iranian languages according to traditional subdivisions of Iranian languages.

However, some limitations to the subgrouping of Judeo-Hamadani need to be acknowledged here. First, there should be a consideration of the use of the terms “northwestern language” and “Median dialect.” Recent linguistic evidence shows that the traditional subdivisions of Iranian languages into western and eastern branches, each of which are split into subsequent sub-branches, is in various respects problematic, and new models are needed to account for them.Footnote 51

Judeo-Hamadani has also been described as belonging to the “Median dialects,” a term first used by Yarshater and later followed by scholars including Borjian and Stilo.Footnote 52 The term “Median dialects” has been extensively used instead of the Central Plateau Dialect group of northwestern Iranian languages.

The term “Median dialects” is rather controversial, and there is no general agreement about its use. One major problem with this term is that Median is attested only by some loanwords in Old Persian and a few other non-Iranian language sources, and its grammar and dialectology are totally unknown. Since the grammar of Median is unclear, a number of scholars believe that we cannot be sure that Median is the predecessor of this group of modern Iranian languages. The term “Median dialects” may also be used to refer to the languages that were and are spoken in the territory of ancient Media. If the designation “Median dialects” refers to the historical region known as Media, then the use of the term seems acceptable.

One theory regarding the origin of Judeo-Hamadani is offered by Stilo and Borjian. In an investigation into Judeo-Median, Borjian follows Stilo’s conjecture that Hamadani Jewish “is probably not original to Hamadān area and will most likely prove to stem from different CPD areas.”Footnote 53 The reason for this theory is not clear but it may have had something to do with the information from Stilo’s informants, whom he encountered in 2001–02. He states:

The Jewish community of Hamadān claims to have mostly migrated there from Yazd in the 18th century. Members of the Jewish community of Tuyserkān also spoke of their derivation as from Yazd, but they also claim a portion of them came from Isfahan, which is most likely true for Hamadān as well.Footnote 54

Nevertheless Borjian underlines the discontinuity between medieval Hamadani and JH:

the historical Median spoken in the Hamadan region is known from a limited number of medieval poems, which are sufficient to make clear that the extinct Median variety native to the Hamadan region belonged to the Tati dialect type of northwestern Iran, rather than the Central Plateau type of central Iran. This historical arrangement might lead us to the inference that only population movements from central Iran could have occasioned the presence of the existing Jewish dialects in the Hamadan area (p. 279).Footnote 55

Much of the historical research to the present day suggests evidence disproving the theory that the origin of Judeo-Hamadani could be from Yazd. According to Amnon Netzer, the reason that the Jews of the southern neighborhood in Yazd speak only New Persian with a Yazdi accent is that they came from Hamadan.Footnote 56 The community members in YazdFootnote 57 also hold the view that at least one group of Jews of Yazd originally came from Hamadan.Footnote 58

A considerable number of historical sources document the existence of Jews in Hamadan in different periods. These sources include a report from the twelfth century estimating that the Jews in Hamadan numbered from 30,000 to 50,000 around 1167.Footnote 59 The records show that the community of Jews in Hamadan was one of the oldest and largest in Iran, and it is very unlikely that they “mostly migrated there from Yazd in the 18th century” as claimed by Stilo’s informant(s). I tend to be more careful about the Judeo-Hamadani stem from different CPD areas and particularly from Yazd.

The studies that have produced estimates of this theory fail to offer detailed and comprehensive data to support their claim. For example, the selected isoglosses across Jewish dialects offered by Borjian provide us with a basic comparison pattern,Footnote 60 but most of these characteristics can be viewed as having a low degree of diagnostic reliability to clarify the relationship of Jewish dialects and the history of migrations of Jews from one city to another. A comparison of JH with Judeo-Yazdi (JY) and Judeo-Isfahani (JI) provides us with important information and may help us to better understand the origins and history of these dialects. Since all three dialects exhibit similar historical phonological developments common to NWIr. languages, a number of other characteristics also need to be considered. In what follows, I focus on selected differences of these dialects.

In phonology, it seems that JI is the most conservative dialect, with its preservation of medial and final *d, both medially and finally as δ∼z and occasionally also medially as -d-, e.g. keze/keδe “house” (JH kiye, JY kéro “house”). An innovation in JI is the development of s > θ, as exemplified by xuruθ “rooster,” eθbed “white,” lebāθ “cloth” and keniθā “synagogue.”

In the pronominal system, the independent form of first person singular, namely mān, in JH is different from all other Jewish dialects. Just as in most other Iranian languages, pronominal clitics are part of the pronominal system of JY, JH and JI. The first observation to be made about the clitics (see Table 4) is that JY uses pronominal proclitics in the preterit (em=, ed=, eš= and um=, tun=, šun=) and imperfect of transitive verbs (me=, te=, še=; also ma=, ta=, ša=) along with modal verbs, e.g. ma=y-vā ve-š-in “I should go” (see also Table 5), while JH and JI use only enclitics. The use of the pronominal proclitic as a subject agreement marker in past transitive constructions is shared by various languages and dialects within Fars, Yazd, Kerman and the Hormozgan area. The plural forms of pronominal clitics are derived from corresponding singular ones by the addition of the ending -ān in JH and -un in JY and JI, which is indeed the oblique plural suffix for nouns. The plural ending -un for first person plural in JY shows another set of clitics, which is probably inherited.

Table 4. Personal pronouns

Note: V: Vowel.

Table 5. Transitive preterit

Different from JY, in JH and JI, the preverb be- is used for the preterit, and the pronominal enclitics are suffixed to be-.

The present enclitic copula and intransitive past suffixes are identical to the person endings, with the exception of third person, the singular copula en and the “zero” suffix for the preterit (Table 6).

Table 6. Person endings of verbs and the enclitic copula

The forms of the person endings of verbs are very similar in JH and JI, while JY differs in employing other forms. The 2S form -eš is not shared by other northwestern languages but can be found in the form of -iš in southern Fars, for example in Lār and Bastak.Footnote 61

JI uses a suffixed and unstressed -e, also called the durative marker, for present and imperfect (pres.: band-ún-e, band-í-e, “I hit, you hit,” etc.; imperf.: ārté-d-e “you used to bring,” še-nd-e “they used to go”),Footnote 62 while JY uses the durative prefix a- (e.g. a-bin-ām “I see,” a-š-e “he/she goes”). JH uses e- (e.g. e-ker-e “he/she does”), though e- is often deleted (e.g. vāy-ān “I say”). The prefix be- is used to form the subjunctive, optative, imperative, preterit and perfect tenses in all three dialects.

All three dialects share the suffix -ād, which forms secondary past stems, with Parthian “and several contemporary languages such as Zazaki and Semnani, while Persian and Balochi use a suffix deriving from *-ita-,”Footnote 63 e.g. JI parθā- “asked,” zunā- “knew,” JH and JY zunā(d), parsā(d) “asked.” All three dialects combine a present stem from the denominative <*waina-a- with the past stem did- (< *dita-), e.g. JY a-bin-ām “we see,” eš=di “she/he saw,” JH bin-ān “I see,” be=m-diye “I have seen,” JI be-ven-id “you (Pl.) would see” and bi=m-di “I saw.”

I could not find any remnant of a new optative ending (Parthian -ēndē) in these dialects. It seems that the optative is expressed with the subjunctive. Stilo refers to two JI examples from Yarshater, xeδā bé-š-keš-ā-Ø “may God kill him” and xeδā ʿomr-ot še t-ā-Ø “may God give you (long) life,” and points out that the optative only occurs in the third person singular and is formed with the optative marker -ā, in which case the third person singular -u is suppressed.Footnote 64

Based on at least a partial comparison of some of the important characteristics mentioned above, we can see that the origin of Judeo-Hamadani cannot be Yazd. Judeo-Yazdi differs in its possession of a number of distinctive characteristics, including a proclitic functioning as a subject marker in post-ergative constructions and with modal verbs, another personal ending system and different person endings and enclitic copulas. Concentrating on only non-typologically marked characteristics and looking only at similarities that are considered normal for northwestern Iranian languages yields incorrect assumptions about the origins and history of JY and JH.

A comparison of JY and Zoroastrian Dari of Yazd (ZDY) can help us to better understand the origin of JY. The similarities between these two languages confirm the possibility that they could partly reflect the former vernacular languages of the city of Yazd. Both languages are very similar in morphological innovations, and, with regard to the fact that such innovations are of particular importance in determining language affiliation, these typologically marked characteristics can be taken as a starting point to establish a genetic relationship. A full discussion of the affiliation of ZDY and JY lies beyond the scope of this article, and I hope to continue this discussion in the future.Footnote 65 For the time being, the crucial point is the possible origin of Judeo-Hamadani.

An opportunity to look at the matter from a different perspective is offered by a considerable amount of poetry composed in the old dialects of the Pahla and Fahla regions. This source helps us to at least begin to close the gap by providing more historical and comparative data as a basis for understanding the origin and history of Judeo-Hamadani.

The importance of Fahlaviyat for the study of the language of Jews in Hamadan and Isfahan motivated Abrahamian to compare material from these languages with that found in Bābā Ṭāher quatrains.Footnote 66 In his comprehensive investigation, he was able to show a number of similarities, though the author offers no explanation for them. Another drawback is that the study fails to draw a distinction between inherited characteristics and innovations through language contact.Footnote 67

This section builds on the idea that the languages of Fahlaviyat of Hamadan and Judeo-Hamadani meet certain criteria and are thought to have arisen from a common language, namely the former vernacular language of Hamadan. I test the hypothesis that Judeo-Hamadani could be a remnant of the vernacular language of Hamadan before it was replaced with Persian.

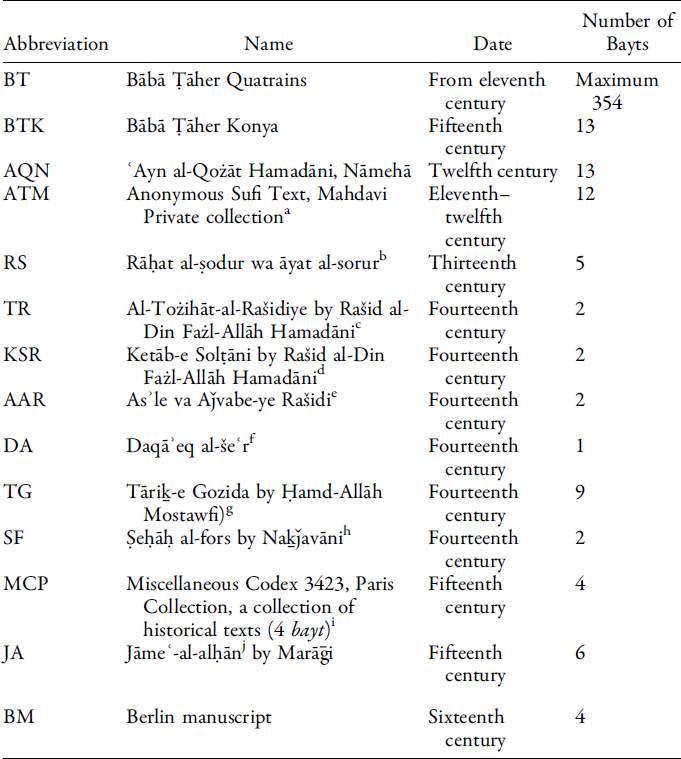

Fahlaviyat include poems composed in the former dialects of the Pahla and Fahla regions. From a linguistic point of view, the Pahla region consisted of western, central and northern Iran.Footnote 68 There are linguistic differences between the Fahlaviyat of different regions. The Fahlaviyat, as survivals of the Central Plateau dialects, have certain linguistic affinities with Parthian, although in their existing forms they have been strongly influenced by Persian. The Fahlaviyats shown in Table 7 have been considered as the Fahlaviyats of Hamadan and are of crucial importance for the research question of this study.

Table 7. Fahlaviyat of Hamadan

Notes:

a For information about this manuscript see Rāstgufar, “Nokte-sanǰihā-ye ʿerfāni.”

b Two quatrains and a single bayt quoted by Moḥammad Rāvandi in the section ẕekr-e ḫāndān-e ʿalaviyān-e hamedān “Mention of Alawite dynasty in Hamadan” and were called fahlaviye. See Rāvandi, Rāḥat al-ṣodur, 45–6; for translation of these Fahlaviyat see Adib Ṭusi, Fahlaviyāt-e lori, 11–12.

c For information on this manuscript and another copy, see Ṣādeqi, “Fahlaviyāt,” 17–18. Since two bayts in TR are probably from Faḫr-al-Din, who is originally Lor, some scholars such as Minovi believe that these verses are written in his own dialect, namely Lori. However, it reflects clear northwestern characteristics and, in my opinion, it could not be Lori. See Minovi, “Tożihāt-e Rašidiye.”

d Perhaps another copy of Al-Tożihāt-al-Rašidiye by Rašid al-Din Fażl-Allāh Hamadāni. See Ṣādeqi, “Fahlaviyāt,” 20, fn. 2.

e Rašid al-Din Fażl-Allāh Hamadāni, Asʾale va Aǰvabe-ye Rašidi, I, 57. For these bayts, see also Ṣādeqi, “Fahlaviyāt,” 21–2.

f Ḥalāwi. Daqāʾeq al-šeʿr, 90. This bayt is by a certain Qāżi of Sajās (a town between Hamadān and Abhar) and cited by Ḥalāwi.

g Ḥamd-Allāh Mostawfi, Tāriḵ-e gozida, 747–8. Kāfi-al-Din Karaǰi was apparently from Karaǰ-e Abu Dolaf, a town between Hamadān and Nehāvand. In TG, it is mentioned that this poet has good verses in Karaǰi language. This book contains the following Fahlaviyāt:

bayt by Kāfi-al-Din Karaǰi in Karaǰi language (ibid., 747–8);

bayt repetation (another variation of the first three bayt) (ibid., 747);

bayt by ʿEzz al-Din Hamadāni (ibid., 740), See Tafazzoli, “Fahlavīyāt.”

h See Naḵjavāni, Ṣeḥāḥ al-fors, 73. The occurrence of the name of Alvand mountain may indicate that the poem was composed in the dialect of Hamadan, as mentioned by Tafazzoli, “Fahlavīyāt.” The author of the text identifies the language of the quatrains as Pahlavi. There seems to be a connection between this Fahlavi and the Fahlvi of the Berlin manuscript (for a comparison see ʿEmādi, “Šenāsā’i,” 140–42). Both quatrains have the same meter and radif and the part vi ta xoš ni “without you is not good” is similar in both of them.

i For images of these Fahlaviyat, see Yāri Goldarre, “Se Pāre,” 54. In the first Fahlavi, the occurrence of the name of Alvand mountain may indicate that the poem was composed in the dialect of Hamadan. The second Fahlavi mentions the name of Kāfi-al-Din Karaǰi, the poet of Fahlavi in Tāriḵ-e gozida. The Fahlavi of Paris Codex by Kāfi-al-Din Karaǰi is not mentioned in Tāriḵ-e gozida. The language of Fahlaviyat of Paris Codex is very simple in comparison to Tāriḵ-e gozida.

j ʿAbd-al-Qāder Marāḡi, Jāmeʿ-al-alḥān, II, 139–42. For reading and translation of these Fahlaviyat, see Ṣādeqi, “Ašʿār-e maḥalli-y-e Jāmeʿ al-alḥān”; and Ṭabari, “Fahlaviyāt-e Jāmeʿ al-alḥān.”

Before proceeding to examine the language of Fahlaviyat of Hamadan, it is necessary to consider certain limitations. The most important limitation lies in the fact that the Fahlaviyat have been Persianized to such an extent that in its present form it hardly possesses the archaic and dialectal characteristics of the original local language. Another limitation involved here is that the readings and meanings of many words are uncertain, and there are a considerable number of variants in different manuscripts (e.g. Tāriḵ-e Gozida (TG)). These limitations mean that study findings need to be interpreted cautiously. In order to understand the limitations and complications of working with Fahlaviyat, I look at Fahlaviyat in ʿAyn al-Qożāt Hamadani’s letters as an example and offer an effective way of studying these materials.

ʿAyn al-Qożāt Hamadani (k. 525/1131, q.v.) quoted a few verses that seem to be in different languages. Tafazzoli points out that these verses are probably in his own dialect, namely Hamadani.Footnote 69ʿAyn al-Qożāt Hamadāni uses the name Owrāma for a group of these verses.Footnote 70 Another group of verses in his letters are called Fahlavi,Footnote 71 and, in one case, Šeʿr.Footnote 72 He also cited a bayt from Bondar Rāzi,Footnote 73 and another bayt from Šeyḫ Abu-al-ʿAbbās Qaṣāb.Footnote 74 However, difficulties arise when we consider the language of all these verses as identical. Let us discuss this issue in detail.

The key problem with the analysis of dialectal verses in ʿAyn al-Qożāt Hamadāni’s letters is that many words cannot be read and understood. Ṣādeqi tried to translate a number of these verses, but most of his interpretations are questionable, and many words were left untranslated.Footnote 75 In particular, the corrections in some cases are problematic and cannot aid the reader in understanding the meaning of the verses.

Despite these limitations, some dialectal characteristics can be recognized:

Bayt of Bondār Rāzi:

This bayt shows the development of *-č-> -ǰ- (rōǰ “day”), the preservation of v-, and a later change of -d- to -y- in vay (NP bad) as well as the use of the present stem ven/vin- “to see.” All of these characteristics are typical of northwestern Iranian and also attested in Judeo-Hamadani.

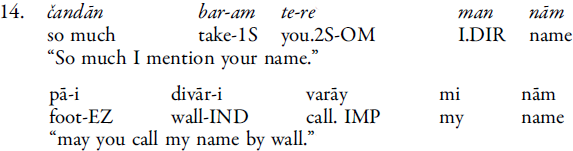

In his letters, ʿAyn al-Qożāt Hamadani quoted a bayt of Šeyḫ Abu-al-ʿAbbās Qaṣāb:

A number of characteristics clearly show that the language of this bayt could not be the same language found in example (13). The construction mi nām (POSS-SB) “my name” is common in Gilaki and Mazandarani. Since Šeyḫ Abu-al-ʿAbbās Qaṣāb came from Amol, it is possible that his language might be Mazandarani. The basis for some scholars’ assumption that the language of this verse is Hamadani is therefore unclear. If the language of this verse were Mazandarani, then the reading te-re “you” would be correct.

ʿAyn al-Qożāt Hamadani’s letters contain a number of Fahlaviyat termed Owrāma. Some examples illustrating the similarities with JH are provided here:

The use of the preverb vā- is similar to what is found in JH and exemplified here in vā-pars- “to ask.” The verb nebbu (NEG-be.SBJ-3S) is identical in JH. The verbal ending u for third person singular is also attested in JH.

Footnote 83Footnote 84Footnote 85

The pronoun (h)amā is a common form in Central dialects, for example, in Xuri. The form bō/bu “was” is also attested in Judeo-Hamadani.

Footnote 86Footnote 87Footnote 88Footnote 89

Similar to that which is found in JH, this Owrāma shows the development of ft>t as in gerte “taken” instead of Persian gerefte. *ǰ- remains as ǰ- in aǰi, and is similar to JH jn∼jen- “hit” (Prth. žan-, NP zan-).

In the first volume of ʿAyn al-Qożāt Hamadāni letters, there are three quatrains.Footnote 90 These verses can be understood with difficulty. Many words cannot be read or translated. The only important characteristic is again the development of ft > t in got (NP goft).

Despite the bayt of Šeyḫ Abu-al-ʿAbbās Qaṣāb, which could not be Hamadani, the other Owrāmas in ʿAyn al-Qożāt Hamadani’s letters and Fahlaviyat exhibit largely the same set of northwestern grammatical properties as Judeo-Hamadani. Linguistic data from Fahlavi sources of Hamadan suggest a number of similar characteristics to JH in the domains of phonology, morphology and syntax and can be summarized as follows:

1. Phonological characteristics. Both Fahlaviyat of Hamadan and JH share the following phonological developments:

*-č-> -ž- ∼ -ǰ-, e.g. in aǰ (Pers. az): “from” in all Fahl. except BT, BTK, až in BT and BTK, in JH az (Persian form), ǰir in JH vāǰ- in BT “to say,” with further weakening to -y/Ø- in vā(y)- in JH “to say,” rōǰ/ruǰ “day” in BT, AQH, ATM, ruž, ru in JH (Pers. ruz), vāžār, vāǰār “market” in JH (Pers. bāzār), suǰ- “to burn” in JH.

*v- > v-, e.g. in vin- (Pers. bin-) “to see” in BT, JH, vas (Pers. bas) “enough” in ATM, vād in JH and RS (Pers. bād) “wind,” vel in BT, BTK (Pers. gol) “flower,” vad in BTK, AQH, MCP (Pers. bad) “bad,” veče “child” in JH.

*y- > y-, e.g. yā (Pers. ǰā) “place” in BTK, RS, JH.

*dz > z, e.g. in zun-, zān “know,” in SF δān- (Pers. dān) in BT, TR, SF, JH.

*ǰ- > ž- ∼ ǰ-, e.g. žan- in BT, BTK (Pers. zan-) “to hit,” žira in BT (Pers. zire) “caraway,” ǰande (Pers. zende) “alive,” ǰen “hit,” žan “woman” all in JH.

*tsv > sp∼sb, e.g. espid in JH, BT, BTK (Pers. sefid) “white.”

*-xt > -(h)t ∼ -(t)t, e.g. in sot- “burned,” vāt- “said,” dot “daughter” all in JH, vāt- “said” in RS, bāht “lost” in RS, sāht “made” in BM.

*-ft > -(h)t ∼ -(t)t, e.g. in kat in BT, SF “fallen,” gert in AGH “took” (Pers. gereft), got in AGH (Pers. goft) “said,” rōte “gone” in JH (Pers. rafte).

Original *u, even in Arabic borrowings, is generally fronted to i both in BT and JH, e.g. hani(z) in BT (Pers. hanuz) “still,” tit “berry,” qebil “accept” in JH.

2. Morphological characteristics. Both Fahlaviyat of Hamadan and JH share the following morphological features:

“To be” of location can be found in both JH and Fahlaviyat, e.g. daru “is” in JH, darim “(we) are” in RS.

Imperative sing. of “to come” in both JH and BT is bur “come!”

Verbal ending 3s is -u in both BT and JH āyu “he/she comes,” in DA: -e.

Present stem of the verb “do” is ker- in both BT and JH.

Durative prefix e- is attested for the present and imperfect in JH and ad- in BTK instead of Pers. mi-.

Suppletive paradigm *waina- / dita- “see”Footnote 91 is attested in both JH and Fahlaviyat, e.g. vin-ān “I see,” be=m di “I saw,” diye-m “I have seen” in JH, and vin-ēm “I see,” diye-m “I have seen” in BT.

3. The post-ergative construction. In at least two Fahlaviyat, namely BTK and JA, we find a post-ergative construction:

A difference between Fahlaviyat and JH is the use of a distinct durative marker. In BTK and JA, ad- is used, while in JH, the prefix e- occurs:

In spite of the shared similarities, a set of differences can be found between FH and JH:

-ā- vowel in mān in JH “I,” as opposed to man and men in other Iranian languages, is not attested in Fahlaviyat.

-ān verbal ending for 1S PRS and INT. PST occurs only in JH beyr-ān “I cut,” dar-kaft-ān “I fell” and not in FH.

The durative marker is ad- in FH, but e- in JH.

After conformational analysis of the linguistics data collected during fieldwork in Hamadan and Fahlaviyat of Hamadan, we are now in a position to suggest some ideas concerning the origin of Judeo-Hamadani. I believe that the similar archaisms and shared innovations between JH and FH provide evidence to further support the theory outlined at the beginning of this study: Judeo-Hamadani could be a remnant of the former vernacular language of Hamadan. This means that the language of Hamadan was a northwestern Iranian language before being replaced with Persian in the New Iranian period.

From a sociolinguistic perspective, the question must be answered as to how and why the Jewish community, more or less a speech island, has maintained its distinct character while in contact with the surrounding speech communities. Several ingredients are necessary to bring about the preservation of this language among the Jews in Hamadan. First, I assume that the reason for the preservation of this language has been its origin in the character of the Jewish community in Hamadan. The historical evidence shows that the Jews of Hamadan earned their living by specializing in different kinds of gold- and silversmithing, glass-cutting, silk-weaving, dealing in secondhand clothes and tanning skins. Many of them were masons, blacksmiths, tailors and shoemakers, and some practiced medicine.Footnote 92

In spite of these activities and having contact with the Muslim population in their business lives, they maintained their own ways in terms of cultural and religious life. Their religiously and culturally based community consisted of the speakers with the highest degree of maintenance of the language. It seems that the community boundaries and conservative circumstances were a matter of language survival. However, linguistic convergence due to contact with Persian has led to the loss of much of this distinctive character and to the extinction of Judeo-Hamadani in modern times.

A slightly different development of the vernacular language of Hamadan has been documented by means of Fahlaviyat. The quality and quantity of the differences between JH and Fahlaviyat suggest the influence of further factors on the vernacular language. The language of Fahlaviyat can be considered a continuum of the oral literary tradition, in which the focus is on poetic beauty and meter rather than on the use and preservation of inherited forms.

It is possible to hypothesize that the remnants of the former vernacular language of Hamadan can be found in the current dialect of the city and in a number of dialects of villages and remote places around Hamadan. Today’s language of Hamadan reflects a limited number of characteristics found in JH and Fahlaviyat. Preverbs vā- and hā- (* fr-> h-), which are widely used in JH and Fahlaviyat, are attested in the current language of Hamedan. The verbal prefix hā is attested in hā-ǰastan “jump” and hā-dāštan “lift.”Footnote 93 The preverb hā occurs in the form he in JH and is used in verbs such as he-gir “take” and he-ni “sit.” The preverb vā- appears for example in vā-ǰastan “release,” vā-ǰidan “unfasten, untie, or loosen (something)”Footnote 94 and vā-vidan “become” in the current Hamadani dialect.Footnote 95

Another important characteristic that can be interpreted as a remnant of the former vernacular language in the current language of Hamadan is the attaching of the plural suffix -ān to the person endings of the first and second plural verbs, e.g. rafd-im-ān “we went,” rafd-in-ān “you went,” rafde bāš-in-ān “would you go (past)” and mi-r-im-ān “we go.”Footnote 96 The person ending -imān is attested in Bābā Ṭāher quatrains, for example in be-š-imān “we would go” and mi-koš-imān “we kill.”Footnote 97

It seems to me that the data which have become available from new fieldwork and from the Fahlaviyat sources invite a new assessment of the former languages of Hamadan, Yazd, Kerman, Isfahan, Kashan and other cities that replaced their former vernacular dialect or language with Persian in the New Iranian period.

Conclusion

The first part of this article was devoted to select features of Judeo-Hamadani grammar that are of crucial importance for the study of the historical development of the language and its typology. Judeo-Hamadani coexisted alongside Persian and persisted due to the isolation of the community and its cultural and religious distance from the surrounding population. For this reason, JH exhibits a considerable number of conservative grammatical characteristics. As far as external influence of the contact language is concerned, Judeo-Hamadani is heavily Persianized. A crucial development that can be observed in the last eighty years of Judeo-Hamadani is in the domain of phonology and includes the reduction of the vowel system and the loss of a homogeneous stress system. Judeo-Hamadani’s suprasegmentals, including intonation, tone, stress and rhythm, have been strongly influenced by the current dialect of Hamadan.

The second part of this article outlined the problems concerning the origin of Judeo-Hamadani in Yazd. It focused in particular on the differences, which are typologically marked characteristics with a high degree of diagnosticity, between Judeo-Yazdi and Judeo-Hamadani and noted the problems of establishing a genetic relationship between these two dialects. Through the use of Fahlaviyats of Hamadan as a corpus and a comparative study of Judeo-Hamadani and Fahlaviyat, the relevant similarities have been recognized. The most remarkable observation to emerge from the data comparison was that these languages could have a singular origin, namely the former vernacular language of Hamadan before it was replaced with Persian in the New Iranian period.

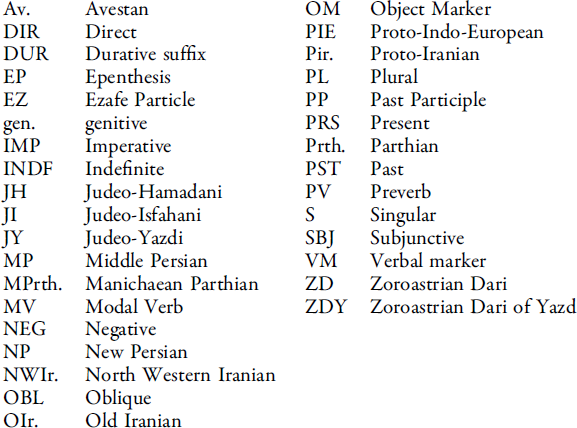

Appendix A. Abbreviations

Appendix B. Specimens of Judeo-Hamadani