Introduction

The received view of how the West democratized in the early twentieth century has concentrated on three reform dimensions: the institutionalization of civil liberties, the extension of the suffrage, and the process of making executives responsible to elected parliaments (see, e.g., Capoccia and Ziblatt Reference Capoccia and Ziblatt2010; Collier Reference Collier1999; Dahl Reference Dahl1971; Rueschemeyer et al. Reference Rueschemeyer, Stephens and Stephens1992; Tilly Reference Tilly2004; Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2006). The development of another key dimension of democratization, namely the capacity to organize free and fair elections, has not been the subject of the same scholarly attention for these old, established democracies. This is highly puzzling from the perspective of democratization in developing countries today. Whereas suffrage is typically universal and executives are at least on paper mostly accountable to the electorate, nowadays “most democratic transitions,” in Pastor's (Reference Pastor1999: 2) words, “often totter on the fence that separates a good from a bad election.” So when and why did the West, by contrast, develop the capacity to hold clean elections? How pervasive was electoral fraud in this part of the world historically, what mechanisms gave rise to it, and when and how was such fraud abolished?

The main aim of this paper is to answer these questions for the case of Sweden, by most observers considered to fit the general description of first wave of democratization. Sweden was largely liberalized politically through the introduction of a bicameral parliament in 1866. The process of making the cabinet responsible to the parliament rather than the king is usually considered to have been completed around 1917; universal male suffrage was established in 1911, female suffrage in 1921 (see, e.g., Lewin Reference Lewin2006; Rustow Reference Rustow1955; Tilton Reference Tilton1974; Verney Reference Verney1957). But when and how did Sweden develop the capacity to organize free and fair elections?

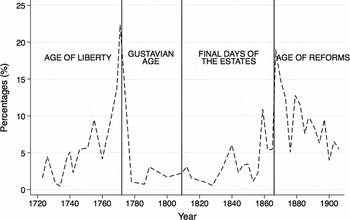

To address this understudied question, I rely on a hitherto largely unexplored source material: charges of electoral fraud filed with political authorities (Lehoucq Reference Lehoucq2003). Consider figure 1, which displays the number of petitioned district elections to the Swedish Diet/Parliament from 1719 to 1921, the first election with universal suffrage. As can be seen, the frequency of election petitions first peaks in the eighteenth century, after which it turns into a slump while returning on a large scale by the mid-nineteenth century. After this, however, the frequency of complaints over elections slowly dissipate and are by the time when universal suffrage is introduced in the early twentieth century almost nonexistent. Sweden is thus a case in point for addressing the more general puzzle of when and how election fraud was eliminated before democracy was established along its other dimensions.

FIGURE 1. Petitioned legislative elections, Sweden 1719–1921.

By delving deeper into the grounds on which the elections were petitioned, I will show that it was only in the eighteenth century that elections in Sweden were outright fraudulent. Most importantly, election officials in both the cities and the countryside interfered in the election of 1771 by attempting to fabricate election results more to their own liking. Toward the mid-nineteenth century, however, these practices had been eradicated, and the second rise of election petitioning rather concerned rule uncertainty before and after the advent of a new bicameral parliament in 1866. Drawing on both qualitative analysis of aggregate-level trends, and a quantitative analysis of the elections to the House of Burghers in 1771, I find that fraud in Sweden was more prevalent when two conditions coincided: (1) the absence of a professionalized bureaucracy, and (2) the presence of partisan elections. This is a theoretical proposition that can be tested in outer contexts and periods.

Tracing the historical root causes of electoral corruption and its abolishment in a case like Sweden is not only of interest for the historical study of comparative democratization. It also holds some keys for understanding the origins of Sweden's extraordinarily successful twentieth-century development at large. Sweden is typically portrayed as having one of the world's most developed welfare states, with comparatively low levels of poverty and achieving high ranking in terms of socioeconomic equality (Esping-Anderson Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001). On the international scene, Sweden today is considered a “norm entrepreneur,” exercising its influence abroad through moral leadership—from sponsoring the Nobel Prize and participating in global peacekeeping efforts to providing generous foreign aid and monitoring human rights abuses in the international community (Ingebritsen Reference Ingebritsen2006). Explaining how electoral corruption was uprooted historically, paving the way for other democratic reforms and the resulting expansion of the welfare state, is thus also a way of shedding light on Sweden as a case of interest.

The paper is organized as follows. Because the aim is to explain an overtime trajectory that has never been unearthed before, I start in the next section by presenting and discussing the data and my measure of election fraud in the Swedish case. “Explaining the Origins and Abolition of Electoral Fraud” then puts forward some theoretical propositions derived from the literature on election fraud, concentrating on my own novel argument about the importance of bureaucratic structures and partisanship. I then test this argument on the Swedish case through within-case analysis, first over time (“Corroborating the Argument I: Aggregate Trends”), then cross-sectionally for the city elections of 1771 (“Corroborating the Argument II: The City Elections in 1771”). I conclude by discussing the portability of my argument to other countries (“Extensions to Other Countries”) and by summarizing my findings (”Conclusion”).

The Rise and Decline of Election Fraud in Sweden

Following Schedler (Reference Schedler2002: 105), I will in this paper define electoral fraud as “the introduction of bias into the administration of elections” that “distorts the voting process in its narrow sense, in any of its multiple steps from the registration of voters to the tally of the vote.” In recent years, a literature in comparative politics has developed an intriguing number of strategies for studying election fraud empirically, based on election observer and other reports (Birch Reference Birch2011; Kelley Reference Kelly2012; Simpser Reference Simpser2013), or advanced statistical analyses of reported vote counts (e.g., Alvarez et al. Reference Alvarez, Hall and Hyde2008; Cantú and Saiegh Reference Cantú and Saiegh2011). For studying a historical case of a first-wave democratizer, however, when there were no election observers and when vote counts are not available, these techniques are not an option. Instead, I will in this paper rely on another, and hitherto largely unexplored, source material relating to electoral practices in Sweden: the election petitions filed with the Council of the Realm, and later the Supreme Court, in 1719–1908. This source has the advantage of being amenable to overtime and within-country comparisons because the system for petitions in place in Sweden was largely kept intact throughout the two centuries of study.

That this kind of source material can yield novel insights into the practice of electoral conduct has already been shown in several other national contexts (Anderson Reference Anderson2000; Bensel Reference Bensel2004; Jenkins Reference Jenkins2004; Kam Reference Kam2017; Kreuzer Reference Kreuzer, Little and Posada-Carb1996; Lehocq and Kolev Reference Lehoucq and Kolev2015; Lehoucq and Molina Reference Lehoucq and Molina2002; Mares Reference Mares2015; Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2009). This is not to say, however, that petitions paint an objective and undistorted picture of the actual historical practice of elections. At least two potential problems affect the findings that may be adduced from this source material. One has to do with the risk of drawing too gloomy conclusions from studying the “underbelly,” as it were, of the elections. If petitions are only a strategic device to extend partisan struggles, or for sore losers seeking personal vengeance, the general practices might have been better than how these petitioned elections portray them. The second problem is exactly the opposite, namely that every case of electoral misconduct does not necessarily make its way into a petition; apart from institutional hurdles (such as the costs incurred), this could be due to lack of education or other resources. Here the risk is thus that conclusions drawn from studying petitioned elections are too rosy.

I nevertheless contend that the richness of nuanced findings from the previous literature illustrates that both these problems can be tackled with. More specifically, it will be deemed crucial to carefully differentiate different types of charges made in the petitions, and to consider the strength of the evidence provided as well as the strategic or institutional motives that prompt or preempt the likelihood of petitioning. Thus, following the lead of Ziblatt (Reference Ziblatt2009), Mares (Reference Mares2015), and Kam (Reference Kam2017), by systematically controlling for various sources of bias in petitioning, such as competitiveness and access to resources, both cross-sectional patterns and long-run trends in petitioning can be used as proxies for the evolution of electoral misconduct, at least in a single-country case study.

The Data

For the purpose of this study, original data on second-instance petitions was gathered at the Swedish National Archive for the three elected houses of the Diet of Estates (Clerics, Burghers, and Peasants) until 1865, and from 1866 the Lower House of the bicameral parliament.Footnote 1 The starting point for the study, in 1719, follows from the fact that this was the first Diet of Estates summoned during the “Age of Liberty” (Roberts Reference Roberts1986), the era in which electoral practices in Sweden first became firmly established. Apart from the House of the Nobility, where each approved noble family was guaranteed a seat, and parts of the House of Clerics reserved for the highest-ranking prelates, the deputies of the Diet were elected. As a rule, clerical elections were held by plurality vote, counted per capita, in single- or multimember districts within the 25 to 30 dioceses. To the House of Burghers, elections were in some larger cities indirect in multimember districts, but in most places direct elections were held by plurality vote in some 100 single- or multimember districts, with votes weighed according to tax burden. Among the peasantry, indirect elections in single-member districts were the rule, with votes graded by tax burden; although there were some 300 rural districts, a substantial number of them chose to elect a common candidate, typically leading to fewer than 150 “effective electoral districts” for the House of Peasants. Naturally, the suffrage was limited. Even within the peasantry, only those who owned their land or sustained a leasehold from the state were enfranchised.

As a rule, each estate conducted their elections without the involvement of any representatives from other estates. The clerics were thus completely responsible for conducting the elections within the dioceses, and the magistrates (mayors and city council judges) for overseeing the Burghers' elections in the cities. The major exception to this concerns the second-stage indirect elections to the House of Peasants, which were overseen by the district judges in the countryside (not part of the peasantry).

In 1866 the Diet of Estates was replaced by a bicameral parliament, summoned every year. Members of the Upper House were indirectly elected every nine years by local assemblies with severely restricted eligibility to stand for office; voting was graded according to wealth and income. The Lower House was elected every three years by plurality vote in 174–201 mostly single-member districts; although indirect elections were initially practiced on the countryside, direct elections soon predominated. The magistrates remained the election officials in the cities, the district judges in rural districts; the latter comprised around 75 percent of the total number of districts. The franchise consisted of all men of age 21 or older that fulfilled certain wealth and income criteria; approximately 80 percent of the adult male population was thereby disenfranchised.

The final year of the study has been set to 1908, the last election before proportional representation (PR) was introduced in 1911. In all, this means that this study covers a bicentenary period of 54 parliamentary elections held in 1719–1908.

The Overtime Trajectory

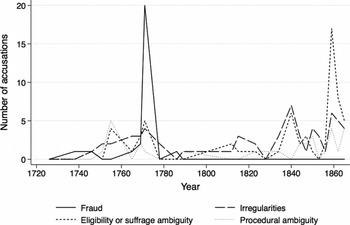

Because the number of elected seats varies over time, figure 2 displays the share of elections to the Swedish Diet/Parliament in a given district for which there was a second-instance petition filed, subdivided into four distinct periods corresponding to the largest political changes concerning the structure of government in Swedish political history. The first period, the “Age of Liberty,” was marked by relatively weak kings and increasingly fierce competition for political power between two political factions, the “Hats” and the “Caps.” From 1738 and onward, the Diet indirectly controlled the composition of the cabinet, the so-called Council of the Realm, which brought a proto-parliamentarian character to the structure of government. As can be seen, the share of petitioned elections increases gradually during this period, to virtually explode during its final eclipse: the election of 1771, the year before the military-backed coup of King Gustavus III. Immediately after the coup, the parties were banned, and the power of the estates was seriously circumscribed, with the ensuing nearly 40-year-long “Gustavian Age” only seeing the convocation of five parliamentary sessions. As figure 2 shows, election petitions waned in this period.

FIGURE 2. Share of petitioned district-level elections by period, 1719–1908.

In 1809 another coup d’état, orchestrated by a group of officers and senior public officials, put an end to the “enlightened despotism” of Gustavus IV Adolfus, the heir of Gustavus III (who was assassinated in 1792). This marks the beginning of the third period, “The Final Days of the Estates,” with a new constitution seeking to balance the power of the legislature and the executive branches of government. The king solely decided the composition of the cabinet, and both the king and the Diet of Estates—to be summoned at least every five years—yielded mutual power to veto and initiate legislation. As can be seen, election petitions then remain infrequent until the mid-1850s when they increase gradually, to peak again in 1866, the first election to the bicameral parliament. The final decades of the nineteenth century, the fourth period, called the “Age of Reforms,” displays short-term fluctuations around a slowly dissipating trend in the frequency of petitions.

Yet the frequency of petitions must also be interpreted in light of the contents of the complaints and the council/court's hearing and verdict. To capture content, I have systematically coded the 141 election petitions containing the most serious charges from the beginning of the observation period until 1865 (the last election to the Diet of Estates). Figure 3 depicts the development over time of the number of charges classified into four categories. Following Lehoucq and Molina (Reference Lehoucq and Molina2002: 17–19), a first distinction is being made between accusations of (1) fraud and (2) irregularities, the distinguishing feature of the former being that the violation in question was intended. To illustrate how this distinction has been used in practice, the city mayor Kiörning in the city of Härnösand was in 1771 charged with having registered people not eligible to vote, and with having counted votes for people not present at the polls, both to boost his own plurality of the votes. Similar charges were in the same year leveled against several magistrates in the cities of Kalmar and Vadstena, whereas the magistrates of Åbo were charged with having imposed a new electoral system to favor their interests. These are thus all instances of what Lehoucq and Molina (ibid.: 17) calls “a plot to overturn election results,” that is, instances of alleged fraud.

FIGURE 3. Types of accusations leveled in election petitions, 1719–1865.Footnote 2

By contrast, a losing candidate in the city of Lund in 1859 complained against several shortcomings in the Burghers' election for that city, mostly pertaining to alleged faults in the electoral register, and in the hundreds of Vestra a losing candidate in the peasantry elections claimed that one of the primary parish elections had been held too early. In neither of these cases, however, did petitioners charge anyone for having fabricated the results intentionally. These are thus coded as instances of alleged irregularities.

A large bulk of accusations do not concern distortions of the voting procedure, intended or not, but stems from unclear rules and ambiguous regulations. These ambiguities could concern (3) the criteria for who was eligible to stand for office or had the right to vote, that is, an eligibility or suffrage ambiguity; or (4) the election procedure, coded as a procedural ambiguity (such as the procedure for how to count graded votes exactly).

As figure 3 makes clear, charges of outright fraud are almost exclusively concentrated to the election of 1771, hardly ever to return during the rest of the period studied. Restricting our attention to this particular election, the far most common charge leveled concerned allegations of severe fraud (comprising 58 percent of all charges). This mostly implied allegations against those responsible for conducting elections to the Houses of Burghers and Peasants (the magistrates in the cities and the district judges in the countryside) for defying the voting tally and certifying someone other than the nominal winner with the proxy for that particular seat. In almost all these instances, the council pleaded guilty to the charges implied and thus confirmed the previous verdict of the court of appeals.

It thus cannot be doubted that the elections of 1771 were marred with fraud. It takes no more than a quick glance at the content of petitions filed toward the mid-nineteenth century, however, to conclude that the nature of charges leveled had at that time changed profoundly. True, some irregularities seem to have occurred according to the petitioners. In neither of these cases, however, did the Supreme Court rule in the petitioner's favor. The far most common ground for petitions in the final elections to the Diet of Estates instead concerned ambiguities with respect to the eligibility for office and suffrage criteria. Were noblemen eligible to stand for office in the House of Burghers? Were persons running a private business, or working for the crown, eligible to stand for office in the House of Peasants? Was it possible to voluntarily decline from being a representative at the Diet, despite having been elected by a plurality of the voters? Such were the issues mostly raised by petitioners in this later period.

Drawing on secondary sources, the picture that emerges from the first decades of the bicameral parliament is no different. A systematic study of all election petitions filed with both the country governors and the Supreme Court after the introduction of the bicameral parliament in 1866–84 found that the irregularities complained against were caused by “negligence, ignorance and indifference,” not with malicious intent to systematically bias the outcome (Wallin Reference Wallin1961: 93). This conclusion has been corroborated in a more recent historical study (Andersson Reference Andersson and Romanelli1998: 367–69), and contemporary overviews of the verdicts of the Supreme Court, also incorporating the first period after the tariff elections of 1887, support the same conclusion (Hansson Reference Hansson1893; Lilienberg Reference Lilienberg1894). The fraudulent practices of the Age of Liberty thus appear to somehow have been eradicated by the mid-nineteenth century.

Alternative Interpretations

Before I turn to evaluating the substantive explanations for this shift, the question whether this is a methodological artifact of the data and research design employed needs to be addressed. To begin with, could it simply be the fact that what changes over time in the Swedish case is the meticulousness with which files were stored, and not the actual situation on the ground? Looking at the direction of change, that seems unlikely. It is the case that the exactitude of the archival records improves over time, but this should make it more likely to find petitions regarding fraud or election irregularities in the nineteenth century, whereas my finding is that they are by then more or less missing. Thus, an alternative story based on the quality of the archival sources does not fit the general trend in election behavior I have uncovered.

Basically, the same objection could be raised against the argument that what changes over time is not electoral practices, but the expectations and ramifying norms of the electorate itself (cf. Piattoni Reference Piattoni2001: 17). To the extent that petitions were filed in response to grievances, they reflect the cultural standards of the time. So how can we separate changing standards from changing practices? As before, I have no way of doing this perfectly, but with rising levels of education, economic prosperity, organizational resources, and even increasing coverage of the elections by the news media, the nineteenth-century Swedish electorate should, if anything, have had higher standards of conduct than their eighteenth-century counterpart. So why then did they not complain about election fraud? The most plausible explanation, I surmise, is that they experienced it to a far lesser extent (if at all).

Explaining the Origins and Abolition of Electoral Fraud

What then can explain the sudden rise and disappearance of election fraud in Sweden? Turning to the literature, a first institutional determinant commonly mentioned is the establishment of the secret ballot. The key theoretical rationale behind the idea that secret voting curbs fraud is that voters cannot be bullied or bought when their actual voting behavior cannot be observed (Baland and Robinson Reference Baland, Robinson and Schaffer2007). In the case of Sweden, however, the secret ballot was established only in 1866 for direct elections and the second-order elections among electors, and not until in 1911 was the organization of the polling stations formally regulated, with voting booths and proper screens mandated (Esaiasson Reference Esaiasson1990: 110). It thus appears dubious that reforms relating to the introduction of secret ballots could have affected the transition from fraudulent to relatively clean elections after 1771. Moreover, it is not clear theoretically how the secret ballot could have curbed other, and in the Swedish case more persistent types of fraud, than vote buying and voter intimidation.

A second institutional feature concerns the electoral system in use. Lehoucq (Reference Lehoucq2003: 252–53) opines that plurality formulas should be more conducive to electoral corruption, for twin reasons: that relatively small number of votes may determine the outcome in each district, and the more person-centered campaigns that usually accrue to the plurality system (also, see Birch Reference Birch2007, Reference Birch2011; Lehocq and Kolev Reference Lehoucq and Kolev2015). Yet, again, the introduction of PR in Sweden in 1911 obviously cannot have explained why the vote had become so relatively clean more than a century earlier.Footnote 3

Drawing on modernization theory (Lipset Reference Lipset1959), a third prominent but more structural hypothesized driver of election fraud is poverty. Because excessive vote buying can be shown to be more pervasive among voters possessed with less economic resources (Lehoucq and Molina Reference Lehoucq and Molina2002; Stokes Reference Stokes2005), industrialization, urbanization, and income growth should present a curb on electoral malpractice (Aidt and Jensen Reference Aidt and Jensen2017; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013). Again, however, there is no easy fit in the Swedish case between the modernization of society and the sudden disappearance of electoral fraud after the Age of Liberty. Industrialization, urbanization, and income growth came late to Sweden, starting by the mid-1800s but not taking off in earnest until the 1890s (Jörberg Reference Jörberg and Koblik1975; Lindbeck Reference Lindbeck1975; Myhrman Reference Myhrman1994; Tilton Reference Tilton1974). By implication, the elimination of poverty cannot be part of the explanation for why election fraud disappeared after 1771.

Relatedly, Ziblatt (Reference Ziblatt2009) finds a systematic relationship between fraudulent elections and landholding inequality in Imperial Germany, arguing that elections could be manipulated indirectly by the powerful “Junkers” in the German countryside, who controlled the election officials (cf. Mares Reference Mares2015). The equalization of landownership in one respect fits the Swedish case because landownership in the eighteenth and nineteenth century was shifted dramatically from the hands of the nobility to the peasants and the so-called nonnoble persons of standing, and this process was even accelerated during the Gustavian Age (Carlsson Reference Carlsson1973: 113–81). However, again taking the nature of fraud into account, there is no clear mechanism relating the existence of inequality to the presence of fraud when it did occur. The Swedish nobility had no “Junkers” comparable to their German counterparts, and even in the eighteenth century Swedish land was, comparatively speaking, evenly distributed (ibid.: 118). Because each estate was delegated the authority of administrating its own elections, moreover, the nobility lacked the wherewithal to control the composition of the other houses of the Diet. In fact, for this very reason, the peasants leasing their land from the nobility were disenfranchised until the 1830s, the other parts of the peasantry looking with great suspicion on their “dependent” counterparts. In Sweden, there is little evidence to suggest that landed elites could “capture” the administration of elections and thus increase the prevalence of fraud.

Considering the inadequacies of these former explanations of election fraud, I will in this paper present two other propositions. First, the previous literature is by and large dominated by accounts of what provides the incentive to commit fraud (e.g., Birch Reference Birch2011; Simpser Reference Simpser2013), whereas the administrative side of what presents or prevents opportunities for fraud has been neglected (Fortin-Rittberger Reference Fortin-Rittberger2014; Pastor Reference Pastor1999). I thus concur with the argument that the structure of electoral governance is of utmost importance for understanding the incidence of election fraud (Mozaffar and Schedler Reference Mozaffar and Schedler2002). Lehoucq (Reference Lehoucq2002) argues that electoral corruption can be most effectively combated when the responsibility for overseeing elections lies with an independent electoral commission and/or the courts, not the legislature. Because parties “cannot police themselves,” the delegation of the oversight of elections to independent courts should help combat electoral fraud (Eggers and Spirling Reference Eggers and Spirling2014). Relatedly, Hartlyn and colleagues (Reference Hartlyn, McCoy and Mustillo2008) argues that the establishment of autonomous and impartial election management bodies have a critical impact on the quality of elections.

Although concentrated on the specific state organs responsible for organizing elections, there is a more general implication that could be derived from these arguments: that the establishment of what Silberman (Reference Silberman1993) calls “professionalism” in the bureaucracy at large—implying, most importantly, nonpoliticized and meritocratic recruitment and promotion to key posts within the administrative apparatus—should be a key reform behind the curbing of election fraud. There are two reasons for this. The first is that a professionalized bureaucracy limits access to patronage as a resource for political elites to draw upon when funding elicit electoral tactics (Epstein Reference Epstein1967; Shefter Reference Shefter1994). The second is that if elections are to be rigged or tampered with, someone must execute the actual tampering or rigging. However, in a professionalized bureaucracy where the election administrators are salaried employees not dependent on patronage, and appointed and promoted based on merits, they are unlikely to see any reason to carry out such clandestine tactics.

If the lack of a professionalized bureaucracy is what makes fraud possible, I do concur with the larger literature that fraud must also be desirable. Because it draws on illicit and typically illegal tactics, there is always a risk involved. This implies that the incentives to commit fraud must be strong enough to outweigh the expected costs of being caught. The conventional wisdom in this respect rests on the marginal impact of cheating: Given that one stands the risk of punishment if being caught, the probability of fraud increases as the number of votes that need to be swayed to win decreases. By implication, the smaller the perceived margin of victory—or the more competitive the race—the more likely that one of the candidates will be willing to cheat (Lehoucq and Molina Reference Lehoucq and Molina2002; Nyblade and Reed Reference Nyblade and Reed2008). As Simpser (Reference Simpser2013) shows, however, it is not necessarily the case that a more competitive race induces incentives for fraud. Sometimes electoral contenders cheat even when they are certain to win, typically to gain more long-term advantages such as intimidating future attempts of opposition. Yet I shall argue that the competitiveness argument neglects an even stronger driver behind election fraud: that the incentives for committing fraud are strongest when political parties are the main electoral contenders.

The essence of this argument is that multiple political parties raise the stakes involved in an election, making it, ceteris paribus, more important to win as compared to a situation when no or only one party appears at the polls. This follows from assuming either office or policy motivations among parties or candidates (Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999). The office seeker would be enticed to win by the fact that multiparty competition seems to strengthen the influence of elected officials over the executive arm of government (Cox Reference Cox1987). Moreover, it could be argued that the rise of parties implies a nationalization of the organization of election campaigns, bringing down costs and raising the material perks distributed to winners (Chhibber and Kollman Reference Chhibber and Kollman1998). The second reason for why political parties make winning more important, however, is not based on material but policy rewards. Parties are more capable than individual candidates to coalesce around policy platforms and to credibly commit to pursuing those platforms once in office (Aldrich Reference Aldrich1995). In this way, too, parties raise the stakes involved in elections. Hence, multiparty elections—regardless of their degree of competitiveness—increase the incentives for committing fraud to win.

In sum, I argue that election fraud is more prevalent when political parties compete at the polls as well as when the bureaucracy at large has not been professionalized. These two propositions, finally, should work most effectively in tandem—that is, when there are both incentives and opportunities for fraud. Parties are thus most likely to drive up the use of fraudulent tactics when the bureaucracy is unreformed.

Corroborating the Argument I: Aggregate Trends

Let us first see how this argument fares when applied to the longitudinal trajectories of the Swedish case. With respect to electoral governance, there is ample evidence that the Swedish bureaucracy was far from professionalized during the Age of Liberty (Cavallin Reference Cavallin2003; Frohnert Reference Frohnert and Blomsted1985). Turning first to the adjudication of election petitions, the executive, in the form of the Council of the Realm, was the highest court of appeals for these petitions, whereas the first-instance petitions were decided upon by the county governors, directly appointed by the council. Moreover, the election administrators—the magistrates in the cities and the district judges in the country—were also dependent on the top brass currently at the helm of the state (Fällström and Mäntylä Reference Fällström, Mäntylä and Ericsson1982: 210–14; Frohnert Reference Frohnert and Blomsted1985: 230). Finally, during the eighteenth century both mayors and, even more so, district judges figured quite prominently among cases of official misconduct heard by the Council of the Realm/Supreme Court. They were charged for various misdemeanors but also more serious crimes including bribery and embezzlement, and some of them were thus deprived of their office (Cavallin Reference Cavallin2003: 193–228).

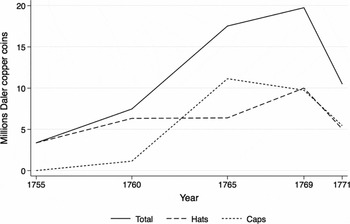

This politicized appointment structure and nonprofessional conduct among election officials created, as it were, the “supply” of electoral fraud in Sweden. But apart from “supply,” there must be “demand” for fraud. Upon my reading of Swedish political developments, this demand was created by the presence of organized political proto-parties. During the final years of the Age of Liberty, Hats and Caps fought ferociously along partisan lines over the control of the Diet and the Council (Brolin Reference Brolin1953; Metcalf Reference Metcalf1977b, Reference Metcalf1981; Olsson Reference Olsson1963). One way to quantify this development is to look at the extent to which the partisanship of the loser in an election is known. Because partisanship of the loser has to be based on information from what is known about the partisan stance of a candidate before the election, it is a much more reliable indicator of whether the election was fought along partisan lines than by looking at the partisanship of the winner.Footnote 4 From a study of the city elections to the House of Burghers (the details of which shall be fleshed out in the next section), I find that the elections of 1771 was unusually partisan with 28 percent of the first losers being partisan, which is steadily on the rise from the less than 5 percent in the election of 1755 (see left-hand solid line in figure 4). True, competitiveness between the candidates, irrespective of partisanship, was also on the rise (see the left-hand dashed line, the margin of victory, in figure 4). But because the nature of fraud usually concerned an outright denial of the election result, not an effort to manipulate the latter at the margin, there is no obvious reason why competitiveness should be driving the outcome.Footnote 6

FIGURE 4. Partisanship and competitiveness in Swedish elections, 1755–1908.Footnote 5

The increasingly partisan structuring of the elections, by contrast, bolstered both types of mechanisms leading to a raise in the stakes of winning, as argued in the preceding text. In terms of office-seeking rewards, it is a well-established historical fact, and was allegedly common knowledge at the time, that the main source of finance for the deputies of the Diet stemmed from the great foreign powers at the time. France thus funded the Hats, whereas England, Russia, and to some extent Denmark fed the Caps (Metcalf Reference Metcalf1977a). Based on the reports of the respective ambassadors in Stockholm, the rough estimates of how much money was spent on each party from 1755–71 is summarized in figure 5. As can be seen, the sheer amounts of expenditure on the parties by the foreign powers increased dramatically, although there was a slight decrease in the Diet of 1771 when the ambassadors started to lose faith in the efficiency of the spending effort. Considering that one day's manual labor earned an income of about 2 daler, and that a simple meal with a drink cost about 1 daler (Lagerqvist Reference Lagerqvist2011: 130), there can be no doubt that these millions of daler amounted to enormously large sums of money. This money was also spent in an increasingly organized fashion, mostly on the purchase of proxies for the House of Nobility; the distribution of pamphlets and other propaganda material to the constituencies around the country; and social clubs and treatment for those elected to the Diet (Brolin Reference Brolin1953: 298–300; Metcalf Reference Metcalf1981: 41n46, 42–43). Because the gold was channeled through the political parties, it was thus of increasing importance to win the election on a partisan ticket.

FIGURE 5. Foreign spending on the parties, 1755–1771 (in 1771 equivalents).Footnote 7

But although the two parties should mostly be seen as cliques held together by personalistic ties (Winton Reference Winton2006), they did compete over policy as well. First, their external funders were also their foreign policy allies, where the Hats favored France whereas the Caps preferred Russia and England. Moreover, the Hats were sturdy believers in orthodox mercantilism that favored exporters and handpicked industrialists as well as the interests of the bureaucratic establishment in general. The Caps, by contrast, were more open to free trade, a less regulated market economy, and above all fought to debunk the power of the state bureaucracy (Metcalf Reference Metcalf1977b; Roberts Reference Roberts1986). The windfall of foreign gold in combination with a deepening policy divide thus created an obvious incentive to win elections, an incentive that more often than before was strong enough to encourage fraudulent behavior.

In line with this argument, after the coup of Gustavus III in 1772 political parties did not structure the pathways to power in Sweden. One of the first of Gustavus's ordinances emitted after the coup in 1772 was a ban on the usage of the names “Hats” and “Caps” in public speech or writing (Olsson Reference Olsson1963: 1). Moreover, during his entire reign Gustavus called snap elections to take his foreign adversaries by surprise and discourage any organized activities within the electorate. Even after the Gustavian Age, the development of political parties was further stifled by the Parliamentary Act of 1810, in large part due to a paragraph stating that the use of “enticement, persuasion or threats” to attract votes at elections was subject to corporal punishment. Although this ban on election campaigning was lifted in 1866, the bicameral parliament was initially largely nonpartisan. Legislative factions did exist, but no clear partisan struggle, either at the polls or over the composition of the cabinet, entered Swedish political life again until after the so-called tariff elections of 1887 (Carlsson Reference Carlsson1988; Esaiasson Reference Esaiasson1990; Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Jansson and Sörbom1972; Thermaenius Reference Thermaenius1935).

But this raises another puzzle: Why didn't fraudulent practices return with this resurgence of partisan election in the late nineteenth century? The answer ties back to the argument on electoral governance. Whereas “demand” for fraud rose again by the turn of the nineteenth century, there was no longer any “supply.” The Supreme Court, since its inauguration in 1789 the highest court of appeals for election petitions, was an increasingly professionalized judicial body as compared to its forerunner in the Council of the Realm (Carlsson Reference Carlsson1990; Metcalf Reference Metcalf1990; Wedberg Reference Wedberg1922, Reference Wedberg1940; Westman Reference Westman1924). And, equally important, there are clear signs of a similar professionalization of the election officials: the city mayors and district judges (Asker Reference Asker2007: 206). In stark contrast to the eighteenth century, an investigation of malfeasance has not been able to trace a single case in the Supreme Court tried against any of these officials after 1840.Footnote 8 More generally, by at least the 1870s the Swedish state appears to have been “bureaucratized,” in the sense that “the last of noble privileges had disappeared, a uniform salary system had been introduced, and the various government agencies had begun reorganizing toward a higher level of efficiency and rationality” (Rothstein Reference Rothstein1998: 303; also, see Teorell and Rothstein Reference Teorell and Rothstein2015). Swedish election officials were now recruited based on merit rather than patronage or political connections; they were also, by and large, salaried employees. What this means is that even for those partisan interests who might have had an interest in fabricating election results to their own favor, there was no longer a cadre of politicized and unprofessional officials who could execute this plan.

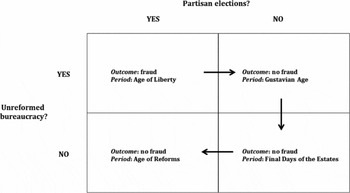

My argument from the Swedish historical experience is thus that electoral fraud is most prevalent when partisan struggles combine with an unreformed state bureaucracy, most notably politicized and nonprofessional bodies responsible for conducting and administrating elections. The aggregate-level overtime evidence for this argument is summarized in figure 6.

FIGURE 6. The overtime case for what drove fraud and its abolition.

Corroborating the Argument II: The City Elections in 1771

The relative timing and nature of events thus go a long way of disentangling the causal mechanisms behind the rise and fall of election fraud in Sweden. Yet this strategy is admittedly wrought with the usual degrees of freedom problem: With several large-scale processes sometimes occurring simultaneously, how to tell them apart and assert causal prevalence for any one of them? As a second strategy, then, I will also conduct a cross-sectional analysis drawing on within-country variation for one particular time point: the election to the House of Burghers conducted in the early spring of 1771.

There are two main reasons why this is the ideal setting to test contending claims of the drivers of election fraud in the Swedish case. The first is that this is where fraud was most prevalent. As argued in the preceding text, in 13 of the 101 cities there were serious allegations of fraud in this election, a figure by far larger than the 6 cases of fraud out of 173 elected peasants, or the complete absence of allegations of fraud among the petitions for the House of Clerics. The incidence of fraud in this election also by far outnumbered all previous elections to the House of Burghers. Second, again compared to the House of Peasants and the Clerics, far more is known about the constituencies where these elections were conducted (i.e., the cities), which crucially also includes the elections that were not petitioned. Because election results in the Swedish case have only been systematically reported from 1872 and onward, even for the city elections this was a huge data collection endeavor.Footnote 9

Gauging the extent to which the election administration in the cities was professionalized is admittedly not an easy task because a unified system of electoral governance was applied in all cities. There is, however, one source of cross-sectional variation that could be tapped into. Recall that the magistrates, consisting of the mayor(s) and the city council judges, were the ones responsible for conducting the city elections. However, they quite commonly also had a personal stake in the contest. Although they were not enfranchised, they were eligible to stand for office, and particularly the mayors were very commonly elected (Nilsson Reference Nilsson1934: 258; cf. Carlsson Reference Carlsson1963: 11). That the person responsible for conducting and overseeing the election was also one of the main contenders in the race was not a situation favorable to impartiality. Because there was variation across cities with respect to whether the mayor ran for office or not, this is a state of affairs that could be measured.

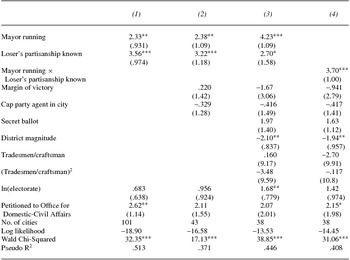

The second major proposition to be tested state that election fraud is primarily driven by partisanship, the measure of which has already been introduced: whether the partisan identity of the loser is known. Table 1 then reports the results of a series of logistical regression analyses with fraud (coded 1, otherwise 0) as the dependent variable.Footnote 10 In all models I also control for the size of the city electorate, which could act as a proxy for the resources available to write up a petition, and a more direct proxy for the selectivity problem: whether the city in question had filed a petition with the Office of Domestic-Civil Affairs. Although this body handled the less serious charges, whereas the Lower Judicial Audit Office ruled on allegations of official misconduct or illegal behavior—that is, the fraud cases—the fact that the burghers of any given city could file a complaint to the former body should have made them equally capable of getting their case tried also before the latter.

TABLE 1. Determinants of fraud in the Swedish city elections, 1771.

* significant at the .10 level; ** significant at the .05 level; *** significant at the .01 level.

Note: Entries are logit coefficients with robust standard errors clustered on counties within parentheses; the constants have been suppressed from the table. The number of observations for the five separate elections conducted in Stockholm have been weighed to sum to 1 to count equally to the remaining cities.

As should be clear, both theoretical propositions are supported: Elections were more fraudulent where the election administration was less autonomous and more politicized—that is, where the mayor ran—as well as where the elections were more partisan in the sense that even the loser's partisan identity was known. These two additive effects are statistically significant at conventional levels when controlling for selectivity in the petitions measure (model 1). To also proxy for the extent of preelection spending, I add in model 2 a control for the presence of a party agent from the Caps in each city as reported to the Danish chief operative (although only available from 1768; Metcalf Reference Metcalf1981: Appendix). Although election results have only been obtained from a sample of 43 cities, I also control directly for competitiveness measured as the margin of victory. The main results are only marginally affected and hold up well even when a host of alternative sources of election fraud, including the presence of voting secrecy, district magnitude, and a proxy for socioeconomic development and distribution,Footnote 11 is controlled for, although this tougher test renders the coefficient for partisanship marginally significant (model 3).

In sum, then, partisanship and partial electoral governance seems to have been the main drivers of election fraud in the 1771 elections to the House of Burghers, in line with my more general argument for what explains the aggregate-level trend of fraud across nearly two centuries. But what then about the claim that these two effects should work in tandem? As a matter of fact, I find support for this claim in the city elections of 1771 as well in that an impressive 10 out of 13 cases of fraud in the city elections did involve the mayor as one of the main contestants. More importantly, in 9 of these 10 cases the mayor lost the election, and in all but one case he then either tried to falsify the result by instructing the other magistrates to issue the proxy (or one of the two proxies) in his name, or in other ways manipulated the counting of votes in a way that assured his own victory. Although the full interactive model including both constitutive terms cannot be tested on this limited data,Footnote 12 simply adding the product term reveals a highly significant result, even in the presence of all other controls (model 4). This implies that, even in this cross-section of elections, partisanship does appear to have exerted most of its causal impact in the presence of a politicized and nonprofessionalized electoral administration.

Extensions to Other Countries

How far could this argument travel? Most importantly, are there lessons to be learned from the Swedish case on how election fraud was abolished in other established Western democracies? A cautionary stance to any broad claims for generalization is that the nature of election fraud arguably differed among countries that democratized during the first wave. British elections were first and formerly compromised by widespread vote buying. In the United States another primary cause for concern seems to have been violence and intimidation, as well as other more regular types of ballot and registration frauds (Bensel Reference Bensel2004; Kam Reference Kam2017; Kuo and Teorell Reference Kuo and Teorell2017; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013). The more precise causal mechanisms operating on the ground thus arguable would look different in these different contexts. Having said this, however, it is a striking fact of election fraud in the United States and Britain that political parties were an essential force behind it, and that the abolition of fraud does seem to coincide with efforts to reform the central state bureaucracy.

Consider, first, the case of elections in Victorian Britain. As has been documented elsewhere, the frequency of election petitions as well as other anecdotal evidence point toward an increased frequency in electoral bribery toward the mid-nineteenth century (Kam Reference Kam2017; O'Leary Reference O'Leary1962; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013). This upward trend coincides neatly with the rise of party competition in the electorate. According to Cox (Reference Cox1987: ch. 9), both split voting and nonpartisan plumping—inverse measures of partisan elections—faded in the British electorate at the time when fraudulent practices became more widespread. Cox even reports a (negative) “correlation between yearly split voting rates and a crude measure of national trends in corruption” (ibid.: 116). This fits my general argument about partisan incentives to commit fraud: When parties rather than candidates started to compete at the polls, policy divides deepened and more was at stake, because elections by then also exercised an indirect influence over cabinet formation. There is thus prima facie evidence to believe that at least part of the rise in electoral bribery in Britain was due to the nineteenth-century rise of political parties.

What then about the marked British decline in electoral bribery toward the end of the nineteenth century (Kam Reference Kam2017; O'Leary Reference O'Leary1962; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013)? Because political parties to this day continue to structure the vote at British polls, decreased party competition can have had no or at least very little role in that decline. Yet there is a striking temporal coincidence between British civil service reform and decreased electoral malpractice. The so-called Northcote-Trevelyan report issued in 1853 eventually led to the introduction of entry into the civil service through competitive exams, a measure that profoundly helped professionalize the British bureaucracy (Neild Reference Nield2002; Silberman Reference Silberman1993). Yet here we must also recall what type of electoral fraud that mostly plagued British elections: the purchase of votes. Because electoral bribery is not conducted by election administrators but by the candidates or parties, bureaucratic reform in this case can only have played an incidental role in its abolition.

There is however another significant reform in the British case that squares with the argument that parties can only conduct fraud if they remain unchecked by an impartial administration. This is the reform of 1868, through which the handling of election petitions was transferred from its partisan treatment in Parliament to independent electoral juries (O'Leary Reference O'Leary1962: 31–43). It has been evidenced that this transfer led to a substantial reduction of bias in the adjudication of election petitions, which most likely tempered the incentives to bribe voters at the polls (Eggers and Spirling Reference Eggers and Spirling2014). In this sense, also the British case supports the argument that election fraud, albeit of a different kind, results from a combination of partisanship and unreformed bureaucracy.

Also in the case of the United States, both according to the trend in contested elections and other sources of historical data (Allen and Allen Reference Allen, Allen, Clubb, Flanigan and Zingale1981; Argersinger Reference Argersinger1985; Jenkins Reference Jenkins2004; Kuo and Teorell Reference Kuo and Teorell2017), the rise of election fraud coincides with the third-party system of increasingly established competition between the Democrats and the Republicans (Burnham Reference Burnham1970; Campbell Reference Campbell2006; Kleppner Reference Kleppner1979). Again similarly to Britain, the decline in fraud that then, according to the same sources, seems to have occurred in the early twentieth century coincides with civil service reform after the Pendleton Act of 1883 and the ensuing fight against federal corruption (Glaeser and Goldin Reference Glaeser and Goldin2006; Johnson and Libecap Reference Johnson and Libecap1995). Because US elections were marred not only by electoral bribery and intimidation, but even more so by clandestine tactics committed by election administrators, such as tampering with ballot boxes or the padding of election registries (Kuo and Teorell Reference Kuo and Teorell2017), one could thus at first glance imagine that bureaucratic reform in this case did help more directly in abolishing election fraud. The problem with this argument in the US case, however, is that the administration of elections is not primarily a federal responsibility. It is instead the states that organize elections, which makes it far-fetched to argue that federal civil service reform could have had any effect on them. Moreover, as has been recently evidenced, civil service reform swept the state-level administrations much later than at the federal level, starting in earnest only in the 1930s and 1940s (Folke et al. Reference Folke, Hirano and Snyder2011; Ujhelyi Reference Ujhelyi2014). This is not to argue that patronage and corrupt election administration did not help fuel US election fraud. On the contrary, there is substantial historical (e.g., Erie Reference Erie1988; Harriss Reference Harris1934) as well as statistical (Folke et al. Reference Folke, Hirano and Snyder2011) evidence documenting the extent to which it did. But the timing of state-level civil service reform does not fit the downturn in fraud in US congressional elections toward the early twentieth century.

What seems more likely, this time like the case of Sweden after the Age of Liberty, is that the fading of structured bipartisan competition described as resulting from “the system of 1896” (Burnham Reference Burnham1970; Campbell Reference Campbell2006; Kleppner Reference Kleppner1987) caused the significant drop. When parties no longer fought as hard for political power at the polls, the incentives to commit fraud to win receded. This is not to say that other reforms or processes were unimportant. Much as in Britain, another significant change occurring at this time was the introduction of the secret ballot, a measure that significantly decreased the practice of vote buying in both Britain (Kam Reference Kam2017) and the United States (Kuo and Teorell Reference Kuo and Teorell2017). But there is no logical relationship between introducing ballot secrecy and decreasing ballot and registration fraud. What the waxing and waning of this type of election fraud in the still administratively corrupt nineteenth and early twentieth century does suggest, therefore, is again that the combination of partisanship and unreformed bureaucracy seem to have plausible explanatory value beyond the borders of the Swedish case. This is indeed a topic worthy of further study.

Conclusion

Drawing on election petitions filed with the highest authorities in 1719–1908, I argue in this paper that Sweden experienced a surge in election fraud toward the end of the Age of Liberty, with election officials manipulating the outcome in several elections to the Houses of Burghers and the Peasantry. Both the aggregate trends and a cross-sectional large-n study of the city elections of 1771 support the notion that a combination of two factors caused this surge: the development of partisan elections, and the absence of an impartial, nonpoliticized and professional bureaucracy. When the parties disappeared from the scene with the beginning of the Gustavian Age, so did election fraud. When the parties reemerged toward the end of the nineteenth century, however, elections were kept clean due to the previous establishment of a professionalized bureaucracy.

In terms of Shefter's (Reference Shefter1994) argument on the relative timing of bureaucratization and democratization, I thus concur with the former but not with the latter. What explained the absence of electoral fraud in Sweden by the mid-nineteenth century was not the limited suffrage (the extension of which is basically what Shefter implies by the word democratization), but the absence of partisanship. Another key difference between mine and Shefter's (ibid.) argument is that, whereas I concur that the sequence of reform in the Swedish case did play a crucial role, this sequence was not irreversible. Parties were introduced before the advent of a professionalized bureaucracy, and election fraud was one consequence of this. But then the parties were abolished, and the sequence could in the late nineteenth century be reversed with the parties reemerging after state bureaucratization. As a result, fraud could this time be avoided.

I have also argued, although more tentatively, that a similar logic may explain the rise and decline of election fraud in nineteenth-century Britain and the United States. If we add a temporal to this spatial dimension of portability, are there even lessons to be learned from the Swedish case about how to eradicate election fraud in the developing world today? Again, there are reasons to be cautious. One key difference between elections in Sweden before the twentieth century and the not fully democratic countries of today is the sheer size of the electorate. Another crucial difference relates to the advent of the news media and modern campaigning techniques, which makes the elections of today a much more protracted event, sometimes occurring over the course of several months. The historical election of Sweden was mostly a one-shot occurrence, typically dealt with in a few hours. All these differences probably imply that the forms of election fraud have changed, and the timing of when it occurs has very much extended. I would still surmise, however, at least as a conjecture for future research, that the nature of parties and state bureaucracies are key causal factors behind the occurrence of election fraud, even in the world of today.