Will partisan messages alter voters’ perceived risk of contracting COVID-19? Will voters internalize elite messages and align perceived risks with the policy preferences of their parties? Since the seminal studies on framing and risks by behavioral economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (1982), researchers have documented framing effects in the subjective assessments of risk and in policy preferences.Footnote 1 Frames can induce myopic responses when the messages emphasize potential gains or losses, which voters weight differently (Thaler et al. Reference Thaler, Amos, Daniel and Schwartz1997; Iyengar Reference Iyengar1990). Frames may also alter perceptions of risk by increasing the salience and memory accessibility of features of an event (Kahneman Reference Kahneman2011). Accordingly, as polarization increases, scholars have documented distinctive partisan responses that align with changes in perceptions of risks (Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Green et al. Reference Green, Bradley and Schickler2004) and in perceived trust in political facts and scientific evidence (Nisbet et al. Reference Nisbet, Cooper and Kelly Garrett2015; Bullock et al. Reference Bullock, Gerber, Hill and Huber2015; Kraft et al. Reference Kraft, Milton and Taber2015).

Political and public health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic provide significant anecdotal evidence of the effects of partisanship on risk perceptions, risky behavior, and policy responses. Populist leaders, such as Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Donald Trump in the United States, and Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico, publicly challenged scientific recommendations and the adoption of strict sanitary measures. Following these cues, government supporters in all three countries publicly challenged and actively mobilized against social distancing rules, the use of masks, and other measures that would limit the propagation of the virus. Nevertheless, the extent to which partisan messages are associated with changes in subjective perceptions of risk is less clear.

Understanding the effect of competing partisan frames on perceived (or subjective) risk is critical to managing the COVID-19 pandemic successfully. Since the early days of the pandemic, social distancing became the most important public health response. Compliance with social distancing measures, however, requires voters to accept the individual and collective risks that may affect them personally. Accordingly, a successful health response needs to evaluate how political beliefs affect perceived risks and interact with policy implementation (Gadarian et al. Reference Gadarian, Goodman and Pepinsky2020; Allcott et al. Reference Allcott, Boxell, Conway, Gentzkow, Thaler and Yang2020; Barrios and Hochber 2020; Mariani et al. Reference Mariani, Gagete-Miranda and Retti2020; Ajzenman et al. Reference Ajzenman, Cavalcanti and Da Mata2020).

This article presents new and timely survey data to understand subjective perceptions of risks during the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey field started on March 23 and continued until May 8. The first official death due to COVID-19 in Brazil occurred only a week earlier, on March 17. This survey collected a snapshot of citizens’ reactions during the first months of the pandemic.

The survey analyzes how perceptions of risks vary among party supporters, how sensitive voters are to information shocks, and how they react to social media frames. To this end, the study first introduces descriptive evidence of partisan differences in perceived risk.Footnote 2 It shows that supporters of the Bolsonaro administration in Brazil report lower subjective levels of job and health risks, along with greater support for the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The results are robust to several control variables and to model specification.

This study took advantage of random variation in the recruitment of survey respondents and modeled the effect of the first national address on COVID-19 by President Jair Bolsonaro. Using a difference-in-difference design with respondents interviewed in the two days before and after the speech, the survey found robust evidence of partisan updates of risk perceptions. The results show that among opposition voters, perceptions of job and health risk increased after Bolsonaro’s speech, compared to independents, while no changes were perceived among government partisans.

The article then presents an experimental design, with an IRB-approved and preregistered instrument, to detect the effect of social media frames on perceived health and job risks.Footnote 3 This experiment exposed respondents to high-level politicians’ positive and negative social media messages about COVID-19, and measured sharing and emotional responses, as well as their effects on perceived risk.

Overall, the analysis finds critical partisan differences in risk perceptions. It also finds a significant uptake in risk perceptions after Jair Bolsonaro’s public speech. However, evidence of framing effects from social media messages in this experiment is modest.Footnote 4 These results align with similar findings in the United States, raising questions about the level of sensitivity of the experimental treatments (Gadarian et al. Reference Gadarian, Goodman and Pepinsky2020).

To understand the modest effect of our social media frames on subjective risk, we conduct a statistical autopsy of our experiment, unpacking the behavioral responses to the experimental frames. The analysis reveals positive effects for the mediation mechanism (“anger”) on perceived health risk and in lower support for the government. However, “angry” responses to social media messages are not consistently higher for publications by out-group politicians; in-group polarizing messages elicited similar reactions. Therefore, while the mediation mechanism elicited the expected response, the different frames did not.

As in the difference-in-difference analysis of Bolsonaro’s speech, “anger” was more readily reported by partisans and increased perceived risks among independents. While the experimental design expected frames to increase partisan anger and anger to increase risk (frames → anger → risk), the findings only validate the effect of anger on perceived risk (frames ↛ anger → risk). By troubleshooting our experiment, we are able to pinpoint the mediating factors that increase perceived risks.

The results of the study have important public policy implications. Current studies in the Unikted States and Brazil have shown that districts with high voter support for Trump and Bolsonaro, respectively, have steeper epidemiological curves for the COVID-19 spread (Ajzenman et al. Reference Ajzenman, Cavalcanti and Da Mata2020; Mariani et al. Reference Mariani, Gagete-Miranda and Retti2020; Allcott et al. Reference Allcott, Boxell, Conway, Gentzkow, Thaler and Yang2020). Our research shows that this is consistent with government messages that made COVID-19 a wedge partisan issue. At a time when perceived health risk is critical to managing the COVID-19 pandemic successfully, the findings of this article should be of interest to health policy and political communication experts.

The organization of this article is the following: first, it introduces the Brazilian case, how the government has reacted to the COVID-19 pandemic, and partisan dynamics in the country. Then it presents descriptive evidence of partisan differences in government performance assessments, perceptions of job security, and perceptions of health risks. It reviews evidence from the difference-in-difference models describing the effect of Bolsonaro’s speech during the survey collection process. Hypotheses and survey instruments test for the effect of negative and positive social media frames on perceptions of risk. The experimental findings are described, and the final section discusses the paper’s overall contribution to understanding how partisanship affects risk perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Brazilian Populism, Out and About

In the first weeks of January 2020, news about the rapid spread of COVID-19 in the Hubei province of China circulated around the world. As Chinese authorities quarantined millions of citizens, governments worldwide struggled to assess the potential domestic damage of the virus and identify the proper health emergency protocols to halt its spread. Timid responses in February, in both Europe and the United States, included travel and trade restrictions both to and from the affected areas. On March 11, the World Health Organization declared the rapidly spreading COVID-19 virus a pandemic, likely to affect every country on the globe.

While some governments promptly adopted social distancing protocols to mitigate the consequences of the pandemic, leaders in a few countries resisted calls for swift action. The president of the United States, Donald Trump; the president of Mexico, López Obrador; and the president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, asked their citizens to dismiss the threat. Among these three leaders, Bolsonaro’s response serves as a textbook example of a defiant, unflinching, and vocal challenge to the scientific recommendations to address the crisis. As community spread of COVID-19 was confirmed in major cities of Brazil, Bolsonaro asked citizens to maintain their regular work schedules and prop up the economy. On the offensive, he criticized the media for their “hysterical” reporting on the virus and accused the political opposition of using COVID-19 for political gain. As he actively impaired Brazil’s own federal agencies, Bolsonaro urged mayors and state governors to roll back stay-at-home orders and repeatedly defied calls for social distancing. He promoted meetings and local gatherings, walked the streets to defy stay-at-home orders, and used his social media account and the bully pulpit of his office to dismiss the health consequences of the virus.

Bolsonaro’s supporters were equally vocal, sharing his social media posts, echoing his “business as usual” demeanor, defying stay-in-place orders, and minimizing the health risks of the crisis. In contrast, the opposition, the media, and most health professionals criticized the president for polarizing messages that failed to respond to the health crisis challenges. Anti-Bolsonaro activists pushed back against the president’s message, circulating their own distinct health messages.

Brazil’s large number of parties make partisanship a weak predictor of voter behavior. The Brazilian party system has been frequently described as “weakly institutionalized” (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring1991, Reference Mainwaring1999; Mainwaring and Scully Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995), with candidate-centered incentives driving politicians’ electoral behavior (Samuels Reference Samuels2003; Ames Reference Ames2001). Recent studies have begun to challenge some of these preconceptions, confirming that partisan and antipartisan sentiments affect candidate evaluation and policy preferences (Samuels and Zucco 2018; Power and Rodrigues-Silveira 2018; Baker et al. Reference Baker, Sokhey, Ames and Renno2016). Our findings bring further support to these views, with partisan preferences having measurable effects on perceptions of job and health risk during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Partisanship and Perceived Risk of COVID-19

As in the United States, partisan assessments of health and job risks are markedly different. Figure 1 vividly portrays differences in perceived risks by supporters of President Bolsonaro and supporters of the opposition’s candidate, Fernando Haddad.Footnote 5 For the outcome variables, three main questions were considered. These questions capture perceptions about personal risk during the COVID-19 pandemic and the respondents’ assessments of the government’s performance during the crisis.Footnote 6

Figure 1. Perceptions of Personal Risk and Government Support

Note: Survey assessments of the quality of the government response, perceptions of personal health risk, and. perceptions of personal job security, March 23–May 4, 2020

A total of 29 percent and 23 percent, respectively, of respondents who supported Haddad considered it very likely that they would lose their jobs or become infected with COVID-19. By contrast, Bolsonaro supporters reported a much lower probability, 22 percent and 12 percent, respectively. The differences are even more salient when reporting their evaluation of the government’s response to the crisis, resulting in 20 percentage points of difference between supporters of the government and of the opposition who considered the government response very appropriate. Measures of positive and negative partisanship toward the Workers’ Party (Samuels and Zucco 2018) yield broader differences on risk assessment, with 33 percent of pro-PT supporters fearing loss of their job and 25 percent reporting being very likely to become infected by COVID-19, compared to 22 percent and 14 percent for anti-PT respondents.

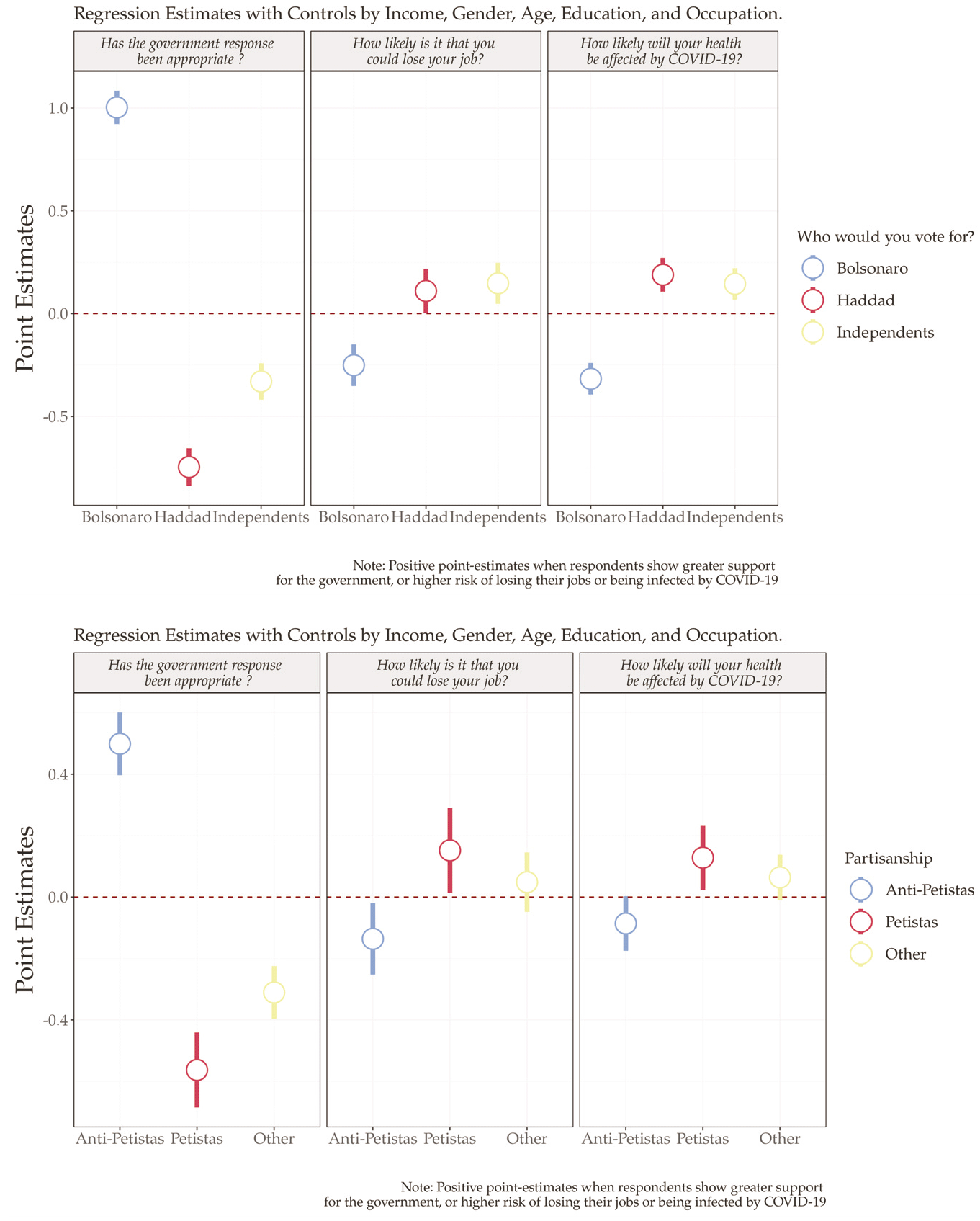

We also present results from linear models regressing the three outcome variables on partisan preferences and a set of sociodemographic variables, such as age, income, education, occupation in the labor market, and gender. The regression estimates using both the voter choice for the last presidential election and positive and negative partisanship toward the Workers’ Party render similar results. These results hold when the models are estimates controlling by age, gender, income, occupation, and education of the respondents. Figure 2 presents the results.

Figure 2. Partisan and Antipartisan Effects on Risk Perceptions and Government Assessment During COVID-19

Note: Linear regression estimates for partisan (top) and antipartisan (bottom) effects on risk perceptions and government assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Descriptive evidence is overwhelming, with significant interparty differences in perceptions of risk and government response assessment. Table 4 of the online appendix reports the effect of the controls. Controls for the models show that employed and highly educated respondents reported lower perceived job risks and higher health risks than unemployed and less educated respondents. Also, as age increases, perceptions of job and health risk increase. In particular, older voters see a considerably larger increase in their perceived likelihood of losing their job. By contrast, there are no statistically significant differences in assessments of government performance and age. Full results are presented in section B, table 4 of the appendix.

Beyond Description: Modeling the Effect of Bolsonaro’s Speech

Descriptive results show dramatic partisan differences in reported health and job risks, as well as in subjective assessments of the government’s response. Bolsonaro’s public speech during data collection can be used to causally identify changes in the respondents’ risk perceptions due to Bolsonaro’s discourses denying the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 7

Bolsonaro, in both social media posts and public appearances, urged local authorities to prioritize growth, challenged (and fired) his minister of health, and minimized the potential health risks of the pandemic. On March 24, President Bolsonaro gave one of his more widely publicized—and dismissive—messages on the COVID-19 crisis and his administration’s response. In a nationally televised address to the country, which was also his first presidential speech dedicated solely to the COVID-19 pandemic, Bolsonaro displayed a confrontational tone. Contrary to most pundits’ beliefs that he would moderate his attacks and hedge his political bets, the president accused governors of overreacting, challenged social distancing policies, criticized school closures, described himself as an athlete who would “not even notice” if he got infected, and labeled the virus, in the worst case, as just a little flu (Phillips 2020).

We made use of the granularity of our survey data over time to model the effect of Bolsonaro’s dismissive behavior about the COVID-19 pandemic during its first days in Brazil. Modeling this event at the beginning of the pandemic allowed us to measure risk perceptions when the number of cases was still modest. The survey started on March 23, allowing us to collect a small part of our sample two days before the presidential pronouncement. As previously, we focused the analysis on the differential effects among partisans and nonpartisans of the president. To identify the effects, we used a differences-in-differences approach on a narrow window of days before and after the event, described by the following estimation:

$$\eqalign{

& {\gamma _{it}} = {\alpha _i} + {\beta _1} \cdot Haddad + {\beta _2} \cdot Independents + {\beta _3} \cdot PostMarch24 + \cr

& \tau \cdot Haddad*PostMarch24 + {\beta _4} \cdot Independents*Post - March - 24 + {\varepsilon _{it}} \cr} $$

$$\eqalign{

& {\gamma _{it}} = {\alpha _i} + {\beta _1} \cdot Haddad + {\beta _2} \cdot Independents + {\beta _3} \cdot PostMarch24 + \cr

& \tau \cdot Haddad*PostMarch24 + {\beta _4} \cdot Independents*Post - March - 24 + {\varepsilon _{it}} \cr} $$

where y if is the survey responses on risk perceptions and assessments of government responses, and the partisan variables come as answers to whom the respondent would be likely to vote for if elections were held the following week. To make the sample before and after more comparable, we limited the analyses for the time window between March 23 and 26.Footnote 8 Our parameter of interest is T, which measures the differences in the outcomes comparing Bolsonaro voters (depicted by the intercept in the equation) and Haddad supporters.

The Effect of Bolsonaro’s Speech on Perceptions of Risk

Table 1 presents the results. The first three (restricted) models use no control variables, while the remaining three control for the respondents’ age, gender, occupation, education, and income. Among Haddad’s supporters, perceptions of job and health risk increased after Bolsonaro’s speech, compared to government supporters. The estimates for health risk are statistically significant at p < .05, while the effects for job risk are statistically significant at p < 1. More interesting, the results show that Haddad voters did not change their overall assessment of the government’s performance. By contrast, we observe a small decline of —0.441 in evaluations of the government’s performance among progovernment voters, significant at p < 0.1. The models that include all controls provide substantively similar, although slightly stronger, statistical results.

Table 1. Effects of Bolsonaro’s Presidential Pronouncement of March 24 on Risk Assessments

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

Linear regression models

The findings provide support for the effect of contextual partisan events on perceptions of risk. Related research has found robust evidence that Bolsonaro’s denial about COVID-19 increased the spread of the disease and reduced levels of compliance with social distancing in progovernment localities (Ajzenman et al. Reference Ajzenman, Cavalcanti and Da Mata2020; Mariani et al. Reference Mariani, Gagete-Miranda and Retti2020). Our results provide a behavioral explanation for these shocking

findings: as the president sends dismissive signals about the pandemic risks, although risk perceptions overall increase, his supporters do not report the same concerns as the rest of the population. Significantly, partisans of the opposition increase their risk perception, while government supporters keep their “business as usual” outlook, decreasing the effectiveness of social distancing policies and facilitating the spread of the disease.

Up to this point, this study has shown robust descriptive evidence for partisanship moderating risk perceptions in Brazil. It has identified strong partisan differences on risk perceptions in Brazil and a direct effect of Bolsonaro’s speech denying the severity of the COVID-19 on in-group risk updates. An online experiment can illustrate how partisanship interacts with framing in the context of social media’s positive and negative messages about the pandemic.

Framing and Risk Perceptions During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Following Entman (Reference Entman1993), we define framing as the act of selecting “some aspects of a perceived reality and mak[ing] them more salient in communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (Entman Reference Entman1993, 5). In social media networks, partisan messages frame events by altering the frequency of words, handles, and images (frame elements) that focus users’ attention on particular partisan traits (Aruguete and Calvo Reference Aruguete and Calvo2018; Lin et al. Reference Lin, Keegan, Margolin and Lazer2014). Posts are made accessible to users when peers publish content that makes salient moral evaluations of blame attribution by increasing the frequency of loaded terms (i.e., the “Chinese virus”), as well as cognitive assessments of likely threats (i.e., “just a cold” [uma gripezinha ou resfriadinho]) (Banks et al. Reference Banks, Calvo, Karol and Telhami2020). Framing is critically dependent on individuals’ willingness to share content they observe in their social media feeds (i.e., cascading activation in networks (Aruguete and Calvo Reference Aruguete and Calvo2018). Once this sharing is activated, peers observe social media messages that “promote a particular problem definition” (Entman Reference Entman1993, 5).

Since Kahneman and Tversky’s Reference Kahneman and Tversky1982 landmark studies on framing and risk, scholars have come to understand that presenting questions to voters in terms of losses yields responses that are substantively different from the responses produced by the same questions presented in terms of gains. Similarly, competing frames that focus attention on distinct issues, such as job losses or health risks, alter the weights that voters attach to the negative economic or health consequences of COVID-19. Consider first how voters may perceive a politician’s message, such as, “we need to work together to address this crisis.” In this case, the speaker’s willingness to cooperate with political rivals provides novel information to voters about the seriousness of the crisis, as well as the importance of investing in reducing health and economic costs, thereby converting enemies into allies. Now compare the previous message with one that attributes responsibility to out-group politicians, such as, “the government response has been careless.” The second message contains less information, since constituents interpret attacks as a “politics as usual” jab among contenders. Negative messages, therefore, activate partisan identities and trigger a politically congruent affective response (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Mason Reference Mason2016).

In polarized political environments, “cross-the-aisle” frames and congruent messages from in-group politicians provide new information to voters about the severity of COVID-19. On the other hand, negative framing by out-group politicians activates partisan identities and reduces the informative value of the political or scientific facts being reported (Nisbet et al. Reference Nisbet, Cooper and Kelly Garrett2015).

Like that of Banks et al. (Reference Banks, Calvo, Karol and Telhami2020), which models the effect of anger on preferences, our experiment presents respondents with a particular type of frame, procedural or generic, which alters the perceived legitimacy of the actors’ response to a crisis (Entman Reference Entman1993). We then inquire about how much negative and positive frames alter voters’ evaluations of government performance and, more important, their relative perceptions of job security and health risk. Like Iyengar and Westwood (Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015) and Nisbet et al. (Reference Nisbet, Cooper and Kelly Garrett2015), our interest lies in understanding how partisanship shapes voters’ beliefs about likely outcomes.

Hypotheses

This study developed a social media framing experiment with positive and negative partisan messages from high-level politicians to understand the effects of partisan preference and framing on risk perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. The first set of preregistered hypotheses tests for the effect of social media content on perceptions of risk and government performance. We consider the effects of negative and positive messages and the extent to which the effect interacts with partisan cognitive congruence or dissonance between the authors of the message and the respondents’ preferences.

Positive messages bring to voters the willingness of political elites to cooperate with rivals to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. In an era of high polarization, these messages provide voters with novel information, reinforcing the importance of unity and cooperation to address the crisis. The negative frames blame political opponents for sowing conflict and weakening the needed response to the crisis. By contrast, positive messages minimize party identity responses and signal that politicians do not behave as in a “politics-as-usual” way. Consistent evidence shows that people weight negative messages more heavily compared to positive information (Arceneaux and Nickerson 2010), and when thinking about risk, negative messages frame risks as dynamic losses for respondents, affecting their attention to the topic (Kahneman and Tversky 1982). The first hypothesis of the experiment predicts negative messages, on average, to increase perceptions of personal risk and induce partisan responses in reported support for the government’s response to the pandemic.

H1. Negative messages will increase perceptions of risk and decrease support for the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to positive ones.

A broad literature on political behavior shows that partisanship is central to attitude formation, in areas as distinctive as a candidate’s evaluation, economic perceptions, support for democracy or authoritarianism, and policy preferences (Green et al. Reference Green, Bradley and Schickler2004; Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2008; Slothuus and De Vreese Reference Slothuus and De Vreese2010; Evans and Andersen Reference Evans and Andersen2006; Zaller Reference Zaller1992). Based on this literature, we expect the framing effect from negative and positive messages to be conditional on partisan identities. The second hypothesis argues that a “politics as usual” polarizing message from elites elicits a partisan identity response from voters. We expect that cognitive dissonance between the respondents’ preferences and the author of the messages will ensure that health risks and job losses will be interpreted as wedge issues that separate the parties. We expect cognitive dissonance to mitigate responses to the social media message when framing in a cross-the-aisle style. Consequently, respondents who observe a cross-the-aisle message from a politician from a different party will decrease risk perceptions and increase support for the government, moderating partisan responses.

H2. Cognitive dissonance and calls for greater collaboration between politicians will decrease party identity responses, decrease perceptions of risk, and increase support for the government.

We expect the opposite effects when cognitive dissonance interacts with negative social media content. As shown by Banks et al. (Reference Banks, Calvo, Karol and Telhami2020), exposure to negative, dissonant social media messages increases contrast effects (Merrill et al. Reference Merrill, Grofman and Adams2003) and heightens perceived polarization, increasing party identity responses and reducing support for the government. After being exposed to negative messages by an outgroup politician, Banks et al. show, voters perceived ideological distance increases (contrast), driving responses to align further with their in-group beliefs. Similar dynamics have been found in previous studies with a focus on political behavior during a health crisis (Adida et al. Reference Adida, Kim Yi and Platas2018).

Following this intuition, we expect that to the extent that respondents observe a dissonant partisan signal with a negative frame, partisan identity responses will be exacerbated. Opposition voters will report heightened risks and lower marks for government’s response. The opposite effects are expected from Bolsonaro supporters, lowering their risk exposure and increasing support for the government.

H3. Cognitive dissonance and negative frames will heighten partisan identity responses. When exposed to cognitive dissonant negative frames:

H3a. Respondents aligned with the opposition will report higher health and job risks and lower performance scores for the government.

H3b. Respondents aligned with the government will report lower health and job risks and greater performance scores for the government.

Experimental Design

Our experiment implements a four-arm treatment assignment in which each respondent is randomly exposed to one of four different tweets, with variation in the content and the author of each message.Footnote 9 Each respondent was exposed to only one tweet, and after the treatment assignment, responded to our outcome variables.Footnote 10 In order to prime respondents in our experiment, we edited tweets. Although we reduced the experiment’s external validity by not using real tweets for our treatment conditions, we carefully chose the wording of the tweets, based on actual public statements and social media activity, to maximize the validity of the treatment conditions. Internal validity was achieved by randomization. Section A of the appendix shows a balanced sample of respondents across a range of sociodemographic and attitudinal variables between the treatment arms.

We varied only two features of each tweet, the author and the content. For the author, we used two prominent political figures: Eduardo Bolsonaro, a federal deputy and son of President Jair Bolsonaro; and Fernando Haddad, the Workers’ Party candidate in the 2018 national election. We chose high-level politicians to ensure congruence or dissonance between the message and the respondents’ preferences.

For the content, we varied between a positive and negative framing of COVID-19. In the positive, we used precisely the same wording for each author, in which the tweets mainly highlighted the existence of a crisis and the importance of President Bolsonaro’s leadership and institutional efforts to fight the pandemic. For the negative tweets, we created one for each sender, mimicking their political preferences, thus maximizing external validity for the experiment. With regard to Eduardo Bolsonaro, the tweets reinforced the argument that the crisis was not serious and that the opposition and the media were responsible for the “hysteria” around the spread of the virus. For Fernando Haddad, the tweets criticized the government and Bolsonaro’s statements minimizing the consequences of the crisis. Appendix C presents the wording of each treatment and the tweets as the respondents read them, in Portuguese.Footnote 11

Results: Framing Risk Perceptions

We manipulated our four treatment arms to identify the effects described, expecting negative messages from out-group politicians to increase perceptions of risk among opposition voters and reduce them among government supporters. The proposed mechanism rests on angry reactions to negative out-group politicians, altering the interpretation of the COVID-19 questions to better follow the policy cues of their preferred parties.

For presentation purposes, we concentrate on describing the relevant comparisons of all treatments, as reported in figure 3, and report the p values for the statistically significant and theoretically relevant comparison. Figure 2 shows significant interparty differences in evaluations of the government and in perceptions of job and health risks. For visualization purposes, estimates in figure 3 manipulate those average results by demeaning our dependent variables and showing interparty deviations when respondents are treated with any of the different frames.Footnote 12

Figure 3. Framing Estimates by Likely Vote

Note: Linear model estimates without a constant. Pairwise significance t-test to evaluate statistical differences across frames.

Consider the first row of figure 3, which reports differences in the variables of interest for each treatment for all respondents. In the plot at top left, we see that a negative tweet by Eduardo Bolsonaro reduces reported perceptions of government responses, while a negative tweet by Fernando Haddad does the opposite.

In fact, respondents move, on average, counter to the political leaning of the author of the tweet, with perceptions of government performance increasing when Haddad posts a message and decreasing with Bolsonaro (p < 0.05). The results also show that, on average, negative tweets by Bolsonaro increase perceptions of personal job risk (“losing your job”), while negative tweets by Haddad reduce perceptions of job risk (p = 0.12). Health risks, however, do not seem to be affected by the different treatments.

The second row presents estimates for the subsample of Bolsonaro voters. Like the full sample, negative messages by Eduardo Bolsonaro decrease overall perceptions of government response to the crisis and increase perceptions of job risk. This is an unexpected result, as respondents treated with negative tweets by Eduardo Bolsonaro are not activating a partisan response by the in-group. The third row reports the estimates of Haddad (Workers’ Party) voters. Messages by Eduardo Bolsonaro increase perceptions of job risks. As with Bolsonaro’s messages, we find no significant results on health risks. Social media frames, therefore, have a measurable effect on perceptions of job insecurity among voters of the opposition, as argued in hypothesis 3b. We find a large gap in job risk perceptions comparing negative messages by Bolsonaro with positive, cross-the-aisle messages by Haddad (p < 0.05).

The fourth row presents the estimates for independent voters, who preferred to submit blank ballots in the runoff election rather than vote for either Bolsonaro or Haddad. We had no preregistered expectation for this group, but we believe the discussion and results are worthy of being reported. Among independents, we see that messages by Haddad increase evaluations of the government while messages from Bolsonaro decrease them (p < 0.05). Different from partisans, the most interesting finding is that positive messages modestly increase perceptions of job and health risks. We interpret this as independents’ identifying partisan messages as posturing, thereby reducing the message’s information value while considering positive messages as informative.

Figure 4 reestimates the models for the subsamples of self-identified partisans of the Workers’ Party (PT), negative partisans (anti-PT), and others. Results align well with those in figure 3. Results indicate that self-identified anti-PT respondents are particularly sensitive to the treatments, with a significant decline in support for the government and an increase in job risk assessment when treated to negative messages by Eduardo Bolsonaro (p < 0.05). In other words, in the broader partisan group of anti-Petistas, a political factor that was crucial for Jair Bolsonaro’s election in 2018, his polarizing message is indeed increasing perceptions of risk and hurting his support.

Figure 4. Framing Estimates by Negative Mass Partisanship

Note: Linear model estimates without a constant. Pairwise significance t-test to evaluate statistical differences across frames.

Overall, our survey experiment finds no robust evidence for our preregistered hypotheses. Although we find consistent and robust partisan differences on nonexperimental survey responses to risk and support for the government during the pandemic, exposure to distinct framing on social media seems to alter little how citizens update their beliefs. Only one of our hypotheses is confirmed: voters of the opposition feel more at risk when treated with a negative message by a high-level politician aligned with Jair Bolsonaro’s government. Given that we conducted multiple tests and did not confirm most of our preregistered hypotheses, we report our experimental results as indicating null effects for framing. This finding goes in the direction of previous investigations about the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. context (Gadarian et al. 2020) and suggests an environment saturated by social media, which would explain why framing and endorsements have no effect on risk perceptions.

In addition, two risk differences are robust in our experiment and are purely exploratory, since we did not preregister these expectations. First, among independents, positive messages are read as posturing, increasing their job risk perception and support for the government. In a polarized environment, crossing the aisle seems to signal to independents that the crisis is rather serious. Second, negative messages minimizing the risks of COVID-19, sent by core members of the government, seem to hurt Bolsonaro’s popularity and to increase job risk perceptions among his voters and partisan anti-Petistas.

Why “Null Findings”? An Autopsy of the Experiment

The experimental results reported here are, at first sight, disappointing. The descriptive evidence showed significant party differences in perceptions of health and job risk. Then the difference-in-difference analysis of Bolsonaro’s speech gave new support for the proposed argument, showing that voters are sensitive to partisan messages, with heightened perceptions of health risk after Bolsonaro’s aggressive stance. The sample size of the experiment is large and comfortably exceeds power requirements, even for the subsamples for party voters and independents.Footnote 13 So why are the results of the framing experiment modest, and why do we find support for only one of our three hypotheses? Luckily for us, we included in the survey a number of validation checks that allow us to explore the mechanisms behind the modest results of the survey experiment.

What Could Have Failed … or Not?

Null findings are always important if they disprove theories but are less interesting if they reflect poor design choices. Therefore, it is important to know what could have failed. There are three different reasons that may explain weak findings in our experiment. First, respondents could have failed to interpret or react to the partisan message of the four different frames. In that case, weak findings would be explained by the failure of the frame or signal to which respondents had to react. We may test for this potential problem because we included a validation check in the experiment, asking respondents if they would “like,” “retweet,” “reply,” or ignore the tweet. Thus we can observe whether partisans’ behavior aligns with the content of the frames.

Second, findings may be weak because the frames did not elicit the expected emotional response to the negative or positive tweets posted by the in-group or outgroup politician. Following Banks et al. (Reference Banks, Calvo, Karol and Telhami2020), we expect the mediation mechanism (“anger”) to activate partisan identities and increase perceptions of risk among opposition and independent voters. This would be consistent with results from the difference-in-difference analysis of Bolsonaro’s speech. However, if the “angry” response to the social media frames is not consistently higher for negative messages by the out-group politician, there would be modest differences in perceived risk among respondents exposed to the different frames. While our experimental design expects frames to increase partisan anger and, in turn, expects anger to increase perceived risk (frames → anger → risk), failing to elicit the correct behavioral response would dissociate the frames from risk perceptions (frames ↛ anger → risk).

Third, it is possible that the treatment frames are properly interpreted by the respondents and that they elicit the expected response, “anger,” without this emotional response changing risk perceptions (frames → anger ↛ risk). In this case, the expected hypothesis would be thoroughly rejected.

In this autopsy, proving the first problem would highlight a design failure (e.g., poor frames); support for the second problem would amount to an expectation failure, failing to elicit the correct reaction to the frames (e.g., “anger”). And support for the third problem would disprove the theory, with the emotional trigger failing to affect perceptions of risk. We proceed now to troubleshoot our experiment and isolate the source of the reported weak findings.

Autopsy of Problem 1: Were the Frames Properly Designed?

To evaluate if there was a failure to communicate the partisan content of the frames, we can take advantage of one of the survey questions that asked respondents whether they would “like,” “retweet,” “reply,” or “ignore” the tweet they had just seen. Descriptive information in Figure 5 shows that, as expected, decisions to “like” or “retweet” follow clear partisan lines, with voters supporting the government considerably more likely to retweet the negative and positive messages of Bolsonaro. Similarly, voters of the PT (Workers’ Party) were considerably more likely to share messages by Haddad.

Figure 5. Favs, Retweets, Replies in Response to Each of the Four Treatments

Note: Responses to the question “Would, you..” (Fav, Retweet, Reply, Ignore [exclusive]).

More interesting, the results show a clear preference by voters to “like” and “retweet” positive partisan messages. While government supporters shared 43 percent of the negative Bolsonaro post, sharing increased to 63 percent for the positive post. Numbers also increased among Haddad voters from 11 percent to 22 percent and among independents from 11 percent to 34 percent. Figure 5 also shows that supporters of Bolsonaro and independents were considerably more likely to share positive messages by Haddad.

Sharing behavior also reflects a much higher propensity by independents to share messages from Haddad compared to those of Bolsonaro. Furthermore, while negative and cognitively dissonant messages trigger “reply” behavior by out-group voters, this is true of Haddad voters only in response to negative Bolsonaro messages. By contrast, there is no equivalent change in “reply” rates when government supporters read a negative Haddad message.

Overall, sharing behavior shows that the treatments were properly interpreted by respondents and triggered the expected sharing response. The results rule out the possibility that the source of the weak findings was a failure to communicate the partisan content of the tweets. Respondents understood and reacted as expected to each of the four treatments. However, there is a clear inclination for positive messages among Bolsonaro voters. This will be relevant when troubleshooting the second problem.

Autopsy of Problem 2: Did the Experiment Elicit “Anger” for Negative Out-Group Messages?

The results in figure 5 already hint that something is not quite as expected and that the affective reaction to the treatments may be more nuanced than anticipated. Positive tweets by both Bolsonaro and Haddad collected more shares than negative ones. Furthermore, reply rates for negative messages by out-group respondents were not particularly high. Both issues suggest that positive frames by out-group politicians and negative frames from in-group politicians have a larger presence in the data than we expected.

We can do considerably more to see how voters react to the content of the tweets and test for “anger” as a mediator because, after we asked respondents if they would share a tweet, we asked them how did the tweet “make them feel.” The “angry” response to this question collected about 8 percent in the positive frames and about 19 percent in the negative frames. While sharing behavior is higher for positive messages, “angry” responses were indeed higher for the negative tweets.

Table 2 presents descriptive evidence using logistic models for the effects of the four frames eliciting “anger” among our respondents. In the overall sample, negative messages from pro- and antigovernment officials induced similar levels of anger, and positive messages had no statistically significant effect. However, while negative posts elicited angrier reactions, the effects filtered by the partisan groups are not consistent: among Haddad voters, both in-group and out-group messages elicited similar amounts of angry response, while among Bolsonaro voters, both out-group negative and positive messages induced “anger.”

Table 2. Regression Models: Effects of Anger on Risk and Support for the Government

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

The results in table 2 provide compelling evidence of a disconnect between the content of the frames and the expected emotional response. The evidence confirms that the negative frames increased “angry” responses. However, the difference between the negative and positive tweets is modest, and “anger” was frequent after reading in-group and out-group messages. Therefore, the proposed frames failed to elicit the expected response (frames ↛ anger → risk). While “anger” was shown to have a crucial effect on subjective risk, the effect of the frames was modest.

Autopsy of Problem 3: Is There a Disconnect Between “Anger” and Risk?

Table 2 estimates the determinants of our dependent variables, perceived health risk, job risk, and government performance. As covariates we include the four treatments, a variable taking the value of 1 if the respondent indicated that they felt anger after reading the tweet, and a latency variable that measured the time, log(miliseconds), that respondents took to answer the “how did you feel” question. As in the preapproved plan, we expect automatic and fast responses to be associated with heightened perceptions of risk, what Kahneman (Reference Kahneman2011) defines as a System 1 response.

Table 2 shows evidence to rule out problem 3 in the health equation. The results show, as expected, that “anger” is associated with an increase in the users’ perceptions of health risk. The effect of “anger” increases perceptions of subjective health risk among Haddad and independent voters.

Results in model 1 of table 2 show that an angry response yields a statistically significant 0.241 increase in perceived risk for the full sample. Model 2 shows that the effect of anger on perceptions of health risk holds when controlling for vote intention, a statistically significant 0.187. The results also show that a lower time to express how they feel is associated with higher perceptions of risk. The effect of time is consistent with a decision that “operates automatically and quickly […] originating from impressions and feelings” (Kahneman Reference Kahneman2011, 21).

Although the results of this autopsy provide compelling evidence of a positive effect of “anger” on perceptions of health risk, validating the mediating mechanism, this is not the case for subjective job risk. The effect of “anger” on job risk is not statistically significant. We interpret the lack of significance as supporting evidence for problem 3 as an issue in the job equation. That is, frames that elicit anger are not having the hypothesized effect on perceived job risk. Furthermore, we do find an effect of the anger mediator decreasing support for the government’s response to the pandemic, as shown in model 5. However, the effect shrinks and loses significance when controlling for party vote, which is a consequence of exteme levels of polarization in support for the government during the pandemic.

To summarize, the autopsy on key validation checks of our experiment allows us to discard problems in the interpretation of the frames (problem 1) and shows a disconnect between the frames and our expected emotional responses by respondents (problem 2). In the case of health and support for the government, our model supports the interpretation that frames ↛ anger → risk instead of the expected frames → anger → risk.

Concluding Remarks

In a time when social distancing is the primary health response to the COVID-19 pandemic, understanding subjective assessments of health and job risks is essential. In countries such as Brazil, Mexico, and the United States, health and job policies have become deeply contested issues that separate partisans and trigger identity responses. This article has provided descriptive evidence of large differences in perceptions of risk by progovernment and opposition voters, has tested for the effect of public discourses by Bolsonaro on perceptions of individual risks, and has tested for the effect of negative and positive social media frames on perceptions of individual risk.

The results verify the existence of partisan differences in perception of risks, a heightened effect of government speeches on opposition voters’ perceptions of personal risk, and a bounded partisan identity response to negative social media messages, particularly progovernment messages denying responsibility for the crisis. Evidence of framing effects from social media messages in our experiment is modest and mostly null, considering our initial hypothesis about the effect of negative content and cross-the-aisle positive social media messages on risk perceptions. However, we find evidence of backlash against negative messages by in-group politicians from government supporters in Brazil. Instead of triggering partisan responses, negative messages by in-group politicians triggered opposite responses. Bolsonaro voters exposed to negative messages by Bolsonaro increased their perceptions of job and health risks and decreased their support for the government. Similarly, Haddad voters exposed to negative messages by Haddad reduced their perceptions of job and health risks. This experiment provides evidence for citizens’ behavioral reactions to different narratives during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil, and suggests that polarization was not being received as an effective strategy by the core supporters of the government.

While the COVID-19 crisis lingers, political acts, such as rallies, party meetings, and fundraising, move to the virtual world. In a context of restricted physical mobility, social media and technologically mediated information exchanges are increasingly important. Beyond the preregistered findings, this research provides novel evidence of the partisan online behavior of negative and positive social media messages. Measures of the social media response to our treatments provide clear evidence that positive messages were more extensively shared by all voters, in-group and out-group, and that negative messages activated a smaller number of intense voters. Negative social media messages, therefore, both induce identity responses by strong partisans and reduce participation by less committed voters. This is an important effect that is worth exploring in future research, as it provides evidence that content in social media data is considerably more partisan than that expected from in-group voters. Therefore, at least in Brazil’s case during the first months of the pandemic, activating partisan identities to energize the base also reduces overall support for the government among its own constituency.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting materials may be found with the online version of this article at the publisher’s website: Supporting Information File. For replication data, see the authors’ file on the Harvard Dataverse website: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/laps