On 23 January 1948, Abuker Hussein, a mason and political activist residing in Mogadishu, asked a special commission of inquiry of the United Nations (UN), the Four Powers Commission, to return Somalia to Italy under international mandate. Since the defeat of the Italians in 1941, the former colony had been placed under temporary British Military Administration (BMA). The end of Italy's oppressive regime spurred the emergence of a series of self-help and socially-oriented associations, especially in Somalia's capital, Mogadishu. Their activism received a further boost when a debate in the UN raised the possibility of self-government and independence for the former Italian colonies.Footnote 2 In order to make an informed decision on the country's future, the UN delegated the Four Powers Commission to visit Somalia and investigate the aspirations of local communities.

When Abuker Hussein testified before the UN in 1948, Somalia's capital was in turmoil. A few days earlier, violent clashes had taken place in Mogadishu because members of Italian and Somali communities sabotaged a demonstration organized by a nationalist movement, the Somali Youth League (SYL).Footnote 3 Although the Commission did not investigate these clashes, it concluded that they were caused by a tense competition between two different political fronts. One of these fronts was the SYL, the foremost political organization of its kind, whose activities were not merely confined to Somalia, but extended to Somaliland, Ethiopia, and Kenya. The SYL opposed the possibility of returning Somalia to Italy and campaigned for the unification of Somali-speaking regions into a Greater Somalia, a project originally launched by British Foreign Minister Bevin in 1946.Footnote 4 The rival front was the Conferenza per la Somalia, an umbrella organization financed by the Italian government that grouped together seven smaller associations – most notably the Patriotic Benefit Union (PBU) and the Hizbia Digil and Mirifle (HDM). These associations claimed to mainly represent the towns and regions of southern Somalia.Footnote 5 When interrogated by the Commission, the associations spoke in favour of Italian rule and were henceforth nicknamed pro-Italia. Their backing of the Italians contributed to the restoration of Italian rule under a ten-year UN trusteeship in 1950.

The Four Powers’ delegates, who convened in Mogadishu in 1948, were preoccupied with determining which power would take over Somalia's administration amid the emerging conflicts of the Cold War. If Somali testimonies also reflected similar considerations, their decision to take part in the international dispute over Somalia had little to do with the Four Powers’ concerns. Despite backing Italy's claims, Abuker Hussein and other Somali activists did not explain their stance in terms of support of colonial rule, but rather placed their choice against the backdrop of regime change, the resulting power vacuum and the rise and diffusion of the SYL. Representatives of the pro-Italia were not convinced that the project of Greater Somalia was the best path forward for Somalia's future and, more generally, that the SYL, accused of acting as a state within the state, was entitled to speak on behalf of all Somali communities. As Abuker Hussein put it: ‘Here, in this place, wherever is a British Officer, next to him there is a Somali Youth League member either as a clerk or as a boy, a personal servant or as an interpreter, and that is why we have troubles.’Footnote 6 Although very little is known about pro-Italia voices, an appreciation of their activities, the tensions that arose and shaped the entire spectrum of associations within Somalia will be crucial in understanding the postwar situation.

By supporting Italy in 1948, the pro-Italia associations crucially affected terms and modes of Somalia's decolonization. However, as they were negatively associated with the former colonial rulers, the successive postcolonial regimes discarded their contribution to Somalia's path to independence.Footnote 7 Concurrently, their voices received little attention from an earlier generation of scholars of Somalia, who instead focused on features and activities of the majority nationalist party, the SYL.Footnote 8 In many ways, this neglect reflects broader trends that characterize the historiographies of colonial Africa. As underlined by Aristide Zolberg as early as 1966, research on African politics suffered from the fact that scholars concentrated on large and dominant political organizations, often underestimating the importance of minority associations.Footnote 9 In addition, early studies on Somalia reflected contemporary concerns of analyzing, assisting, and justifying the emergence of nationalism and nation-states in Africa.Footnote 10 This predominant historiographic focus on nationalism was also accompanied by a tendency to approach Somali politics through the paradigm of agnation, commonly defined as a clan system, which rested at the foundation of Somali society. Accordingly, the clan system, with its centrifugal and centripetal features, was seen as shaping and informing both nationalist and more ‘sectarian’ politics.Footnote 11 Although this approach highlighted certain patterns within Somali society, it also produced a rather reductive take on local politics. Hence, the formation of the pro-Italia movement was framed as a clan-based reaction to the SYL and more specifically a reflection of traditional cleavages between agro-pastoral and pastoral communities.Footnote 12

Admittedly, historiographies of Somali studies have been widely revised over the last two decades and these debates have questioned the role played by the clan system in Somalia's recent political developments vis-à-vis the impact of socioeconomic changes taking place in the twentieth century.Footnote 13 Yet if new historical research on postwar politics is growing, scholarly focus on nationalism still predominates.Footnote 14 What is more, novel studies on the critical phase of Somalia's decolonization and the interaction between Somali activists and colonial rule have either concentrated on the latter dimension or on reinterpreting existing scholarship under a different theoretical framework.Footnote 15 Thus, there remains an urgent need to further scrutinize the postwar period. As Frederick Cooper noted, pre-independence politics in Africa should not be reduced to anticolonial or nationalist movements, as these ‘were both smaller and larger than the nation, sometimes in creative tension with each other, sometimes in repressive antagonism’.Footnote 16

Renewed attention to postwar politics would also require a critical examination of sources and biased narratives of the then-occupying power, the BMA. Early scholarship failed to historicize and problematize these sources (re)producing limited views of the Somali past. To be sure, this flaw can be partially ascribed to the scant and fragmented nature of archival materials that are often difficult to locate and access.Footnote 17 However, it also reveals a tendency to heavily, and often uncritically, rely on the BMA's official publications, whose main aim was to justify the occupation of the enemy's colonies and to present it as a liberal triumph over fascist oppression.Footnote 18 The notion that the British occupied Somalia in order to emancipate local communities still lingers in scholarly works. For example, consider the work of the established scholar of Somalia, Ioan M. Lewis, whose A Modern History of the Somali is to date the most comprehensive study of modern Somali history. Although Lewis's scholarship has already come under a critical gaze, the issue of chosen sources and their underlying rhetoric demand additional consideration.Footnote 19 This is especially true for Lewis's account of British-occupied Somalia, which remains unequivocally wedded to wartime propaganda:

To understand the atmosphere in Somalia at this time [during the BMA], and the nature of the relations between British officials and Somali, it has to be remembered that the new rulers saw themselves as liberators from fascist oppression and to a considerable extent were so received. Indeed, the generally friendly reception accorded to them reinforced the Administration's tendency to regard the Somali as allies against the Italians. And many British officials made no secret of their admiration for Somalis and contempt for the defeated Italians. Hence there was from the beginning a considerable bond of sympathy between the rulers and the Somali public, which, in the liberal currents of opinion of the times, found expression in a strong and quite explicit pro-Somali policy.Footnote 20

By conferring upon the BMA the role of ally and liberator of Somali communities, a more critical engagement with the military occupation was hindered and the possibility that parts of Somali communities were less keen or submissive to British rule conveniently forgotten.Footnote 21 As this also contributed to perpetuating a sense of shame that was associated with the pro-Italia’s backing of former colonial masters, it is not surprising that research on postwar minority associations defensively denied this collaboration.Footnote 22 This becomes all the more problematic because echoes of wartime stereotypes still resonate in contemporary literature today. Bearing the stigma of having favoured the return of Somalia to Italy, the pro-Italia phenomenon has been recently portrayed as a corrupt movement, fuelled by bribes and Italian meddling.Footnote 23

There is little doubt that Italian propaganda agents on the Ministero dell’Africa Italiana’s (MAI) payroll sought to bribe local organizations in order to promote their interests in the former colonies.Footnote 24 But by reducing the pro-Italia movement to these activities, the issue of support of former colonial rule is left unproblematized – as if part of Somali society had been inherently inclined to side with the Italians regardless of their views, local opportunities, and circumstances. Looking at this front as the by-product of Italian initiatives also fails to account for the longevity of some associations, as that of the HDM, whose activism continued long after the UN decided to return Somalia to Italy.Footnote 25 The question, then, is not whether Italy's attempts to further its position managed to amass forms of local support, but it is rather about the whys and wherefores of these dynamics.

Gramsci's notion of consent – the masses’ acquiescent attitude to the direction imposed on social life by the dominant fundamental group that enjoys a hegemonic position in the system of production – has been often adopted to investigate the dialectics of domination and resistance in colonial Africa.Footnote 26 Important studies, such as Glassman's Feasts and Riots, have drawn attention to ways in which both dominant and subordinate groups contributed to the production of hegemonic ideologies, arguing that forms of consent do not necessarily serve the interests of the oppressor.Footnote 27 A similar perspective helps illuminate the motives behind the pro-Italia front. And the fact that these voices came together during the British occupation – at a time when Italian colonial power was not, conceptually speaking, hegemonic in the area – points to the necessity to move beyond the allegedly pro-Italian feature of the pro-Italia and further investigate the meanings of political alignment in postwar Somalia. What follows is an attempt to do so.

At the end of the Second World War, international discussions concerning Somalia's future, combined with British and Italian efforts to build local alliances for their competing hegemonic projects, compelled Somali activists to take sides. The launch of the Bevin Plan, which promoted the idea of Greater Somalia, spurred and galvanized the activities of the SYL and paved the way for a cooperation between the national party and the BMA. The PBU, the HDM, and other more recent associations engaged with Italy's initiatives in an attempt to antagonize the SYL. This process of political alignment compromised the image of Somali politics, drawing focus onto the existing hostility between international powers and the perceived tensions inherent to Somali society. Although the pro-Italia front ended up uniting activists claiming to represent the interests of semi-pastoral regions and clans of southern Somalia, this did not occur according to predetermined patterns. It was the agenda of the national party that was a significant bone of contention between different voices. Pro-Italia representatives argued that the programme of the SYL – a unified Greater Somalia with no clan based differences – would put land rights and access to resources, regulated by clan and regional belongings, at risk. Similar issues continued to inform politics in self-governing Somalia, resulting in a tense relation between the SYL and the opposition. But once the SYL gained power on the eve of independence, its governments managed to silence other parties and exclude them from parliamentary representation.

THE UN DEBATE AND THE IDEA OF GREATER SOMALIA

During the discussions regarding the future of Italian colonies, the Big Powers’ representatives, who were appointed to the Commission of Foreign Ministries, generally agreed that Somalia should be granted self-government via a new form of international mandate. These debates were preoccupied with establishing which power was best placed to lead Somalia to independence. Among other plans, Britain's Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin launched the idea to create a Greater Somalia to bring together most Somali-speaking regions under British trusteeship. As Bevin further elaborated before the House of Commons in 1946, the plan intended to give ‘the poor nomads a chance to live’ under a united country and Great Britain recognition for their victory over Italy's East Africa Empire.Footnote 28 But the Bevin Plan was also in line with Italy's past attempts to redesign the spheres of influence in the Horn of Africa. After occupying Ethiopia, Italy had expanded Somalia's border limitations, annexing the Somali-speaking region of Ogaden. The War Office, in charge of British administration in the Horn of Africa, de facto maintained Italy's territorial adjustments until 1948.Footnote 29 As Cedric Barnes has argued, this demonstrated that the British believed that the future of the whole area remained ‘implicitly bound up with the fate of the ex-Italian Somaliland’.Footnote 30 In this way, the idea of Greater Somalia remained a recurrent theme within British internal correspondence. This theme continued to influence their policymaking process in spite of the fact that the British government officially abandoned the Bevin Plan due to opposition from other Big Powers and Ethiopia.

In many ways, the launch of the idea of Greater Somalia had a long-lasting impact on political developments in Somali-speaking regions. British chief administrators – Brigadier Wickham in Somalia, Brigadier Fisher in Somaliland, and Colonel R. H. Smith in Ethiopia's Somali-speaking regions – had already contributed to drafting the proposal during wartime.Footnote 31 With the announcement of the Bevin Plan in 1946, they began to promote the idea locally.Footnote 32 If in wartime Somalia the BMA had shown little interest in local affairs, it later pursued a more direct engagement or a ‘closer touch’ with Somali communities.Footnote 33 One of the first changes occurred in early 1946, when the War Office instructed military authorities in Mogadishu to establish a series of district councils that would integrate customary representatives into the military administration.Footnote 34 At the same time, the BMA began to engage with Somali clubs that had emerged after Italy's oppressive regime came to an end. Originally based in Mogadishu, the largest associations were the SYL, founded as the Somali Youth Club, and the PBU, nicknamed Jumiya, both promoting mutual assistance and cooperation against the background of wartime shortages.Footnote 35 Their agendas aimed to enhance the local trade industry, severely hit by the war, and education policies that were largely neglected during Italian rule.Footnote 36 With the regime change, these associations also became providers of essential welfare systems.Footnote 37

In the summer of 1946, the BMA presented the Bevin Plan to Somali associations and disclosed the information that a special investigative commission of the UN was soon due to visit Somalia in order to decide upon future dispositions.Footnote 38 The news came like a bombshell, because it anticipated Italy's formal renunciation of any rights to its former colonies – namely the quitclaim of colonial possessions – that was to be stipulated by the Peace Treaty in February 1947. Urged to organize politically, Somali clubs broadened their scope and purpose so as to mobilize more widespread support. They were soon joined by an array of brand-new associations that emerged to promote the interests of a variety of other under-represented groups. Although very little archival data exists today to illustrate this trend, the rapidity with which brand-new associations were put together is telling of the importance given to this historical juncture. Recapturing the intensity and the range of these activities is thus an important endeavour. As recent work on Eritrea and Somalia's nationalist movements has illustrated, further scrutiny into postwar sociopolitical mobilization often reveals neglected, yet crucial, contributions to the ‘paths towards the nation’.Footnote 39 But postwar activities should not be reduced only to nationalist movements because not all of the concerns that motivated Somali activists came to be associated with nationalist paths. Nonetheless, they all attempted to envision a possible future for Somalia amid the constraints and possibilities of the postwar period.

Seeking local alliances, the BMA began to work closely with the SYL. Although this cooperation was almost certainly motivated by a common interest in the Bevin Plan, it also reflected the military authorities’ appreciation of the party's original features. In contrast to other groups, the SYL was founded as a youth movement, which also meant that its early members were less likely to have played an active role in the previous administration. To the BMA, this was a welcome attribute. During the early phase of occupation the BMA had in fact grown wary of Somalis who had worked for the Italian regime. The British had exiled and replaced a number of clan leaders under the Italian colonial salary-scheme for alleged insubordination and/or for assisting the enemy.Footnote 40 Moreover, the belief that members of the SYL had had little to do with the Italian regime fit nicely with the wartime rhetoric that the BMA had chosen to use. This helped present their occupation as the inauguration of a new era of ‘progress’ and emancipation from fascist oppression.Footnote 41 It is crucial to look into this rhetoric because on the one hand it provided a source of inspiration to many Somali activists, and on the other hand, it also contributed to constructing a dualistic image of Somali politics that distinguished between the groups that conformed to the new standards of progress and ones that did not.Footnote 42 As a consequence of their cooperation with the BMA, the SYL came to represent a product of the modernizing process initiated by the British occupation. Accordingly, reports drafted by the military regime began to portray the SYL as a ‘progressive’ organization, ‘sincere in its desire to further the interests of the Somali people … [and which had] to be regarded as a law abiding club’.Footnote 43 Its leaders – modern, ‘intelligent and quick-witted’ young Somalis – also met the standards of the new regime.Footnote 44

Enjoying the BMA's approval, the SYL was able to make the most of the opportunity offered by the UN debate. Seizing the Bevin Plan, the SYL used the idea of Greater Somalia to promote an egalitarian society, which would bear no division and discrimination based on clan ties. The association further endeavoured to politically mobilize all Somali communities by reducing the age limit of its membership. Within a few months, the organization turned from a Mogadishu-based self-help youth club into a national party with active branches scattered throughout the Somali-speaking regions.Footnote 45 This success was in great part due to the party's ability to tap into some of the aspirations and dissatisfactions of young entrepreneurs and recently settled urban dwellers. In particular, the party sought to promote Somali participation in the commerce by advocating ‘a peaceful eviction’ of Arab/Yemeni traders from the economic sector.Footnote 46 The party's agenda to eliminate the clan system was also met by some popular support and party affiliates occasionally refused to state their clan belonging in court cases or business transactions.Footnote 47 But it was the idea of Greater Somalia that enabled the party to enjoy a great deal of popularity beyond urban centres and to create ‘a popular rally call’ that brought together different priorities in the party's agenda.Footnote 48

But the rapid diffusion of the nationalist party was also materially facilitated by an increasing number of SYL members employed in the BMA. By 1946, ‘clerks [of the BMA], servants of Europeans, traders, medical dressers, members of the Somalia Gendarmerie’ figured prominently in the party's membership.Footnote 49 In particular, the SYL started to recruit heavily from the Somali Gendarmerie, the new police force. In early 1947, an estimated three-quarters of policemen stationed in Mogadishu belonged to the SYL, while almost no policemen were members of other political groups.Footnote 50 To some extent, the BMA worried about the ‘disquieting’ popularity of the party in the police force, because they feared the possibility that the Somali Gendarmerie ‘might not oppose an agreed demonstration by the Somali Youth [League]’.Footnote 51 Nevertheless, at this stage, the BMA favoured the employment of SYL members in the military regime because it provided ‘a material source of help’ to British chronic problems of personnel shortage in Somalia.Footnote 52 British preferential treatment of the SYL contributed to the shaping of the idea, frequently recorded by the UN commission, that the SYL worked in collusion with the BMA.Footnote 53 This perception remained vivid despite the fact that the SYL had withdrawn support from a British mandate for Somalia by the end of 1947.Footnote 54

While the SYL made good use of their position within the BMA to expand across Somali-speaking regions, the other larger association at the time, the PBU, struggled to put together a political agenda that would catalyze support on a broader scale. In 1946, the association had its headquarters in a makaja in via Roma in the Xamar Weyne neighbourhood of Mogadishu and relied on the proceedings of a trading textile company.Footnote 55 In the capital, the association counted roughly 1,000 members recruited mainly from Abgal Somali, one of the largest communities in the area, benefitted from ‘generous donations’ of Arab/Yemeni communities, and had active branches in the districts of Baydhabo and Marka.Footnote 56 Certainly, the BMA did very little to facilitate the development of the PBU. In the eyes of the British, the PBU did not deserve assistance because it was supported ‘by a number of chiefs … mostly the disgruntled ones and the troublemakers’.Footnote 57 Its female members were discredited for being ‘for the most part prostitutes’, whilst ‘many of the male members [we]re undesirables’.Footnote 58 Moreover, the BMA disliked the PBU's popularity among the Abgal community. As the latter passed for ‘the largest single tribal factor’ in Mogadishu, the BMA assumed that it was also ‘the largest tribal trouble making and criminal factor’ in the area.Footnote 59 As a result, the BMA tended to conclude that although ‘the alleged aims of the Jumiya [we]re identical to those of the Somali Youth [League],’ the PBU was ‘a reactionary movement fostered for the preservation of certain vested interests’.Footnote 60

Clearly, the PBU failed to live up to the standards of progress and development of the new regime. By contrast, the SYL had appropriated British wartime rhetoric and advanced calls for social and political change that emphasized the progressive features that the movement had prompted in Somalia.Footnote 61 These articulations reinforced the narrative that differentiated between the associations that had adjusted to the ‘modern times’ and the groups that had remained in the past. But this dichotomy did not only serve to classify ‘modern’ and ‘backward’ associations, it also helped define the national character of the SYL as opposed to the ‘tribal’ and ‘traditional’ features of other groups.Footnote 62 Commenting on the parties’ anniversary celebrations held in 1947, the Chief Civil Affairs Officer, Donaldson, made this distinction clear:

Those of the Somali Youth League … seemed purposeful and were well organised. A large number of British officers and their wives were the only European guests invited. The ‘hosts’ were almost exclusively young men in modern-cut suits. By comparison, those of the Patriotic Beneficence Union (Jumiya) were somewhat haphazard and ill organised … a selection of leading Italians were present … . It was also more picturesque in that there was a greater predominance of traditional Arab and Somali costume.Footnote 63

Complicating the PBU's reputation further, military authorities identified the association as responsible for the ‘Mogadishu riots’ of August 1946 when a number of protesters broke into the British headquarters and were forcibly dispersed by police fire.Footnote 64 Although this was most likely a protest against the rationing of food supplies and impending urban taxation, the BMA saw the demonstration as the result of anti-British activities, ‘indirectly’ linked to a series of strikes taking place at the time among Italian personnel, ‘with the purpose of lowering British prestige’.Footnote 65 However, there was no evidence that connections existed between these episodes and, more generally, that groups of Italians had influenced the PBU's activities in August 1946. It was the rising anxieties of military authorities over possible rebellions and their preferential policies towards the SYL that made the PBU, and other groups, turn to former colonial rule.

SHAPING THE PRO-ITALIA

Despite negotiating the quitclaim of colonial possessions for the Peace Treaty, the postwar Italian government had not given up aspirations of returning to their former colonies – Eritrea, Libya, and Somalia – via forms of international mandate. The still-functioning Ministry of the Colonies, MAI, devised plans to promote Italy's position through the activities of locally recruited agents who attempted to put together political fronts in support of former colonial rule. MAI hoped this would help create a legitimate basis for Italy's colonial claims before the UN.Footnote 66 The creation of a web of contacts between the MAI and Somalia was sparked by the arrival of a delegation headed by a senior colonial official, Luigi Bruno Santangelo. Starting in October 1946, he managed the repatriation of civilians and prisoners of war from East Africa. During its visits, the party delegated senior Italian personnel, selected by the BMA as representative of the Italian community, to engage in a variety of propaganda activities.Footnote 67 These efforts reached a climax in September 1947 when Italian money financed an umbrella organization, Conferenza per la Somalia, to bring together seven associations. According to the UN Commission, the groups that joined the pro-Italia platform had ‘a predominant influence in the B[a]na[a]dir and Upper Juba provinces’, that is, in the districts of southern Somalia.Footnote 68

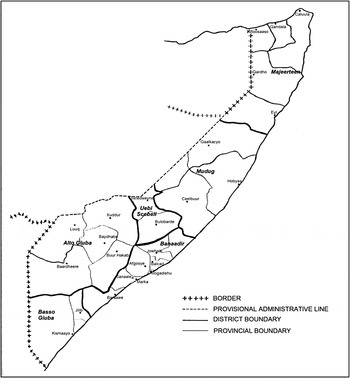

Fig. 1. Administrative Map of Somalia, 1953. Source: Compiled from Istituto Centrale di Statistica, Censimento della Popolazione Italiana e Straniera della Somalia (Rome, 1958).

In an attempt to explain the formation of the pro-Italia front, recent studies have directed their attention to the MAI's efforts to revive past networks of collaboration with Italian colonial rule. The argument goes that, in looking for potential partners and collaborators, Italian agents relied on the support of groups that had facilitated colonial rule in the past, such as clan and religious leaders and colonial soldiers.Footnote 69 However, this argument incurs the risk of taking the MAI reports on its activities in the former colonies at face value. In truth, the strategy to ‘revive contacts’ had little grounding in postwar Somalia. There were no fixed networks of support for Italian rule, which had been temporarily interrupted by British occupation, waiting to be reactivated. Admittedly, parts of Somali society had some interest in recovering their relations with former colonial masters. Colonial soldiers, for instance, having been disbanded following Italy's defeat in 1941, awaited payments for their war services.Footnote 70 But in spite of Italian attempts to mobilize these groups, they did not make a significant contribution to Italy's cause when presented to the UN.Footnote 71

The associations that joined the Conferenza per la Somalia in September 1947 had emerged independently of their relations with the former colonial rulers. This meant that although their concerns and interests converged and intersected with the pro-Italia front, they did not necessarily coincide with the colonial aspirations of the defeated Italians. Mohamed Hassan Gure, secretary of the Union of Africans in Somalia, made this point clear to the UN Commission in 1948. Questioned about the nature of their support for Italy, the activist explained that when they had decided to organize politically they ‘did not think … to have Italy’ as administrative power but ‘thought [of their] own interest’.Footnote 72 The reasons that motivated Mohamed Hassan Gure and others to side with Italy were thus contingent on the postwar context.Footnote 73

Above all, the process of political alignment enforced by the visit of the UN Commission was compromised and monopolized by British and Italian antagonism in the Horn of Africa. These were hostilities that dated back to wartime rivalries. In the early 1940s, the Allied rhetoric had presented the occupation of Italian colonies as part of the liberation campaign and official publications of the British government had openly condemned Italy's rule in Somalia.Footnote 74 By the end of 1946, the MAI returned the favour and instructed agents in the former colony to compile ‘materials’ – such as data on economic productivity – that would document British misrule before the UN.Footnote 75 Comparisons between British and Italian rules were also debated in print media in Italy and the United Kingdom.Footnote 76 In an attempt to defend their imperial reputation, the BMA distributed guideline questionnaires to Somali associations that specifically asked their delegates to compare British and Italian administrations to the UN.Footnote 77

Seen from this perspective, the question of Somalia's future was reduced to a choice between former colonial rule and military occupation. Somali associations were asked to frame their aspirations accordingly. This left the delegates to the UN with few options. As Sheck Mohamud, of the Conferenza per la Somalia, pointed out:

We were hating the Italian government, and were saying may God bring the British Administration … [that we thought] was a justice giver and peacemaker … [but] when they had been here for six months they started to loot our property and arrest our people … when we saw everything was upside down we were hoping God to bring the Italian Administration back.Footnote 78

As the quote suggests, backing Italy somehow offered an alternative to the BMA and the grievances associated with the military occupation. The significance of this alternative should not be underestimated, especially in the context of such a power vacuum and the ever-growing uncertainty over future sovereignty. This situation particularly concerned areas that had been affected by Italy's territorial adjustments and whose future was yet to be settled. This was the case in Qalafo, a settlement of semi-sedentary communities located on the Shebelle River in modern Ethiopia. As a contested boundary area, disputes among different powers were not new to the district. Throughout the 1920s, Italy's efforts to expand their occupation clashed with Ethiopia's attempts to impose tributes on local commerce.Footnote 79 With Italy's occupation of Ethiopia in the mid-1930s, Qalafo was at first included in the Italian colony and, in 1941, came to be placed under temporary British rule.

In areas like the Qalafo district, those who felt compromised by the recent past had good reason to fear retribution in the future. Consider the figure of the legendary Sultan Olol Dinle of the Ajuuraan clan. In the 1920s, the sultan accepted Italy's protection and used colonial arms and ammunition to prevail in a dynastic dispute for local hegemony with Sultan Hamed Badil.Footnote 80 In the 1930s, he led an armed band in Italy's campaign against Ethiopia and was awarded military decorations by the Italian regime as a result.Footnote 81 With Italy's defeat, Olol Dinle's position was bound to change dramatically and, after initial attempts to resist British occupation, the sultan gave himself up to the BMA. Considered ‘an able and dangerous man’, Olol Dinle was moved to a prison in Mogadishu because his ‘prestige as a guerrilla leader would enable him to raise following from tribes [in southern Ogaden]’.Footnote 82 When returned to Qalafo in 1947, Olol Dinle found the possibility of the area being placed under Ethiopia's sovereignty discomforting. This uncertainty offered Olol Dinle little option but to renew his allegiance to Italy and participate in the dispute over Somalia's future.Footnote 83

As the visit of the UN approached, support for Italy also granted access to a series of resources that would enhance grass-roots activism. Urging to make their aspirations known to the Four Powers’ delegates, the UN called for Somali communities to organize politically. As the UN had also raised the possibility of self-government and independence for Somalia, the visit of the Commission was certainly a welcome opportunity. At the same time, some pragmatic issues arose as to how to better prepare for the occasion. There was no tradition of prewar organized political activism in Somalia. The series of self-help movements that emerged in the 1940s were not based on consolidated party structures that would further the mobilization of communities on a large scale. Getting hold of some kind of structural support was therefore crucial. Because the BMA provided leasing contracts and authorizations for public gatherings, meetings and processions, the backing of the British administration was clearly important. But, as MAI's agents understood all too well, the Italians also possessed an array of equipment that could facilitate political campaigning. This included technical support such as the provision of printing facilities, venues for political gatherings, vehicles, and fuels – the latter particularly well received given wartime shortages – but also funds for political campaigns and the distribution of so-called ‘lucrative donations’ to individual activists.Footnote 84

Most likely, it was the Mayor of Mogadishu, Vincenzo Calzia, who had coordinated these activities in Somalia, while the MAI had financed the propaganda drive through money transfers to private companies, notably the electricity supplier De Vincenzi.Footnote 85 The efforts to create alliances with Somali communities reflected the broader policy of the postwar Italian government. By mid-1947, Italian officials had made a series of campaign promises in the media to sponsor a possible return of Italy to Somalia. These included the commitment to establish a democratic regime based on ‘cooperation and equality between Italians and Somalis’, and to proclaim a general amnesty for the crimes committed during the BMA.Footnote 86 Building upon this policy, Italy's agents began to tour Somalia in order to directly come into contact with leading Somali figures, such as political activists and policemen, to promise future rewards in return of their backing before the UN, and to offer financial support.Footnote 87 In spite of this attention to local politics, Italy's agents had a limited interest in Somali associations and expressed no preference for any particular group to rise above the rest. Their intention was to converge the activities of all Somali associations ‘towards one single goal: [Italy's] interest.’Footnote 88 It was the response of Somali activists to the MAI initiatives that changed the political scenario.

Unsurprisingly, of the various associations active at the time, the PBU was the first to engage with the Italians. Marginalized by the BMA and overwhelmed by the rise of the SYL, the association came to a dead end by the final months of 1946 and reduced its activities to charity and assistance to the poor.Footnote 89 Italy's efforts to establish local alliances represented an opportunity to break free from the political impasse and to antagonize the SYL. Within a few months, the PBU's Secretary Islao Mahadalle Mohamed – a translator employed by an Italian judge, but largely unknown to MAI circles – became a key figure in the pro-Italia movement. He was both a coordinator of the Conferenza per la Somalia and a leading delegate when interacting with the UN.Footnote 90

The most noticeable result of this interaction was a steady increase of pro-Italia propaganda activities. Equally important were the changes in power relations among Somali and Italian communities in the former colony. Engaging with the MAI's initiatives, pro-Italia activists were able to seize and influence means of communication that had been the exclusive domain of the Italian community. This concerned the local media in particular. After the war, Italian newspapers began to promote Italy's renewed responsibility to their ‘civilizing mission’ in Africa.Footnote 91 Somali activists appealed to the new ‘enlightened’ principles of the Italian government and demanded Italian-controlled local media revise their targeted audience to make space for Somali voices. Thus, Radio Rome began to broadcast in Somali, the local periodical paper Il Popolo published activists’ articles that debated the legitimacy of Italy's claims over its former colonies, and the printing house at the Catholic mission in Mogadishu produced leaflets and posters for their campaign.Footnote 92 If this front easily married the anti-British tones of Italian propaganda that equated wartime socioeconomic impoverishment with the BMA, it also became clear that it did not simply reproduce the MAI's advertising. For example, when military authorities searched the Conferenza per la Somalia’s headquarters to confiscate anti-British publications, they were surprised to find materials produced without the ‘approval’ of Italian agents.Footnote 93

Another result of this cooperation was the expansion of the number of associations that joined the Conferenza per la Somalia. By the summer of 1947, these were able to increase their membership, often at the expense of the SYL.Footnote 94 Although it seems likely that the MAI dispensed considerable sums of money to these associations, Italy's financial support is not enough to explain the progress of the pro-Italia phenomenon. Italian officials themselves had several doubts of the extent to which the distribution of money, as opposed to ‘political arguments’, brought about positive results.Footnote 95 Facilitated by the Italians, their progress often entangled with different sets of dynamics. The area of Qalafo is again a case in point. During Olol Dinle's imprisonment in Mogadishu, the SYL had managed to open a few party branches in the area. When Olol Dinle was released from prison and opened up a branch of the PBU in 1947, the SYL encouraged local communities to disregard the sultan's authority and shift their loyalties to the emerging party. According to BMA intelligence reports, the hostile SYL attitude towards the sultan stemmed from the party's proposition to overcome the clan system and clan authorities.Footnote 96 At the same time, the controversy became an occasion to revive older disputes between Sultans Olol Dinle and Hamed Badil, whose followers seemed to support the SYL branch in Qalafo.Footnote 97 Repeated clashes between the sultan's supporters and SYL members occurred, resulting in several casualties, including the injury of Olol Dinle during one of these conflicts.Footnote 98 In September 1947, Olol Dinle directly confronted the President of the SYL, Haji Mohamed Hussein, who travelled all the way from Mogadishu to face the situation. Summoned by the British local commissioner, the leaders spent ‘four whole days in fruitless discussions’ before reaching an agreement.Footnote 99

The Qalafo district was not alone in its experience of the disrupting effects of political alignment. Apart from the major towns where political groups had been most active, political competition between the pro-Italia front and the SYL developed intensively in southern Somalia, especially in the districts of Afgooye, Baydhabo, Buur Hakaba, Kismaayo, Jowhaar, and Marka.Footnote 100 By the time the UN Commission visited Somalia, there were many formal complaints, charges, petitions, and counter-petitions. While the SYL accused the HDM and PBU of cooperating with former colonial masters,Footnote 101 associations of the pro-Italia front complained that the SYL abused its position of power within the BMA, particularly within the police, so as to intimidate and repress their work.Footnote 102 As Mohamed Hassan Gure put it:

We did not fear the authorities. We only feared [the] Somali Youth League and the military [Somali Gendarmerie] because the Government of this territory accepts only the word of the Somali Youth League …[for this reason we] pray God and the Four Powers that this land should not be left to the present Government.Footnote 103

THE QUESTION OF LAND AND THE IDEA OF GREATER SOMALIA

The direct accusations the pro-Italia made against the BMA contributed to the stigmatization of this front in the longer term. Drafting reports on political developments in Somalia, military authorities were quick to dismiss the pro-Italia coalition as a reflection of clan-based cleavages between agro-pastoral and pastoral communities that were inherent to Somali society. Their belief was supported by the fact that the pro-Italia front brought together associations that claimed to represent semi-pastoral regions and clans of southern Somalia.Footnote 104 Building upon the perceived inequalities among Somali communities, the BMA marked a clear-cut divide between the allegedly ‘pure’ Somalis, the nomadic clans of Dir, Daarood, Hawiye and Isaaq, and the ‘mixed blood’ and semi-agriculturist clans of the Raxanweyn. Because the BMA saw their membership as consisting ‘largely of Arabs and such non-Somali tribesmen as the Ra[xanweyn] and some Bantu Riverines’, this racialized discourse served to ridicule the pro-Italia front.Footnote 105 More generally, the BMA questioned their right to have a say in the international dispute over Somalia's future because they argued that these groups played ‘a less specific role in the life of the community’.Footnote 106

As the BMA had contacts with the British delegation to the UN Commission, it is not difficult to see how British biases affected the work and findings of the Commission.Footnote 107 Above all, these prejudices discriminated against pro-Italia voices, precluding a closer attention to their claims during hearings with the UN. Yet, a closer look into these voices sheds light on how the series of concerns that motivated different activists went beyond the dichotomization of Somali politics as construed by a tension between ‘progressive’ and ‘retrograde’, ‘modern’ and ‘tribal’ movements. Although the UN hearings were subjected to a contested and manipulative questioning, they offer a more nuanced insight into different claims and represent a unique written testimony of activists explaining their political stance.Footnote 108 If the coalition of associations under a pro-Italia front took the form of communal tension, this entangled with the more poignant question of land rights and access to fertile cultivation lands in southern Somalia. As pro-Italia delegates claimed representation for these regions, they took the visit of the Commission as an occasion to defend what they referred to as ‘their land’ and its economic importance from potential contenders.Footnote 109 From the point of view of contemporaries, the economic future of an independent Somalia lay in the development of agriculture and agricultural productions from these districts. The HDM, for example, was quite outspoken about the necessity to officially recognize land property rights, arguing that other groups ‘think they may live and stay with us, but we want them behind us recognising the land as belonging to us and not to them’.Footnote 110 For this reason, they emphasized the need to define who was entitled to lay claims to territorial resources in future Somalia.Footnote 111

Concerns about land and access to resources were also behind the dispute between the pro-Italia front and the SYL, entangling with the broader question of envisioning a future independent Somalia. Among other reasons, the former opposed the national party because its agenda would purportedly pose a threat to the rights agriculturist communities enjoyed over fertile lands. As these rights were also regulated through clan and regional belonging, the SYL's proposition to eradicate the clan system, if applied literally, would have led to a loss of land privileges. Thus, it was no surprise that while the SYL insisted on the necessity to overcome the clan system in a nation-building effort, others associations were less eager to do so. The Hidaita Al Islam, for instance, explicitly requested its members ‘to notify their identity, name, father's name and tribe as prescribed by Moslem laws’.Footnote 112 Ultimately, questions of land and land rights were positioned against the SYL's final aim, the unification of all Somali-speaking regions into a Greater Somalia. On the matter, Islao Mahadalle Mohamed of the Conferenza per la Somalia pointed out that:

The fact is that the question of Greater Somalia is a question raised by the Somali Youth League, who were led to request it because of Foreign Minister Bevin talked about a Greater Somalia.Footnote 113

While previous scholarship on Somalia has devoted a great deal of attention to the importance that the question of land played in postcolonial politics, the fact that similar issues were at the centre of political debate in the postwar period is often overlooked. These questions continued to shape Somali politics in the following decade resulting in tense relations between the SYL and the HDM, the main opposition party in the 1950s. For example, the draft of a land law in 1952 revived conflicting views over land rights, and where the League pushed for the revision of these rights, the opposition insisted on having them recognized by official legislation.Footnote 114 This contention also gave rise to clashes between different parties’ affiliates. Most notably in 1953, SYL supporters in Mogadishu stabbed Ustad Osman Mohamed Hussein, a prominent member of the HDM and of the Territorial Council, to death.Footnote 115 Some time later, HDM affiliates incited violent clashes against members of the SYL in the city of Baydhabo.Footnote 116 Although both parties were involved in these conflicts, it was the opposition that took a beating in the ‘contest’. By the time Somalia gained independence in 1960, members of the SYL occupied the majority of key governmental posts and the influence of southern associations in postcolonial politics remained marginal. As Lee Cassanelli has noted, the exclusion of southern associations from these posts can be certainly attributable to the fact that by the mid-1950s the Italians had withdrawn their support of associations that had joined the Conferenza per la Somalia and had openly begun to favour the SYL.Footnote 117 Moreover, this exclusion was also part of a policy the SYL adopted to repress the opposition.

Once the SYL gained power in 1956, its government strove to keep other parties away from parliamentary representation. First, the government ratified a law that forbade the use of clan terminology in political parties’ nomenclature, a measure clearly directed against the opposition party.Footnote 118 Subsequently, the SYL-led government established the shamba tax, or tax on farming, that although technically applied to the whole country, mainly targeted the districts of southern Somalia that hosted the majority of cultivations. Enforced in 1957, it triggered numerous protests by farming communities that were harshly repressed by the police.Footnote 119 In the same way that the BMA had adopted a racialized discourse to ridicule the pro-Italia front, the SYL used the rhetoric of their fight against the clan system as a way to gloss over demands and protests coming from the opposition.

A final and decisive attempt to curb smaller associations took place just before Somalia achieved independence. Pressured by an increasing number of dissenting voices both within and without the party, the SYL-led government approved legislation to increase its power over internal affairs.Footnote 120 It later passed an electoral law that complicated the requirements for the presentation of electoral lists. In order to run in a certain constituency, each party had to present a list of ninety nominees, supported by 5,000 signatures and by the payment of 90,000 Somali shillings. This made electoral competition for smaller parties extremely difficult. Footnote 121 In some cases, ruling authorities rejected electoral lists presented by the opposition due to alleged irregularities.Footnote 122 As a protest against these measures, opposition parties boycotted the electoral competition and the SYL won the absolute majority of votes by default. As a result, 83 out of 90 seats of the Legislative Assembly elected in 1959, the bulk of Somalia's first independent government, were assigned to the SYL. Hence, opposition parties were, for the most part, excluded from parliamentary representation and were cut off from the debates that addressed the features of Somalia's Constitution Charter that would determine the future Somali Republic.Footnote 123

CONCLUSION

The defeat of Italian colonial rulers in Somalia by the Allied forces in 1941 inaugurated a time of hope, optimism, and opportunity for many Somalis. Future expectations were further boosted by the possibility of achieving independence, raised by international debates that developed in the UN starting in 1945. But the active involvement of the UN in arranging Somalia's future also had the unforeseen consequence of enhancing the position of the former colonial power. Encouragement and pressure for Somalis to organize politically, albeit well-intentioned, ended up favouring Italian agents that, possessing more resources and means of propaganda, were necessarily advantaged in the competition for national rule. The disrupting impact that this process had on local politics is one worth taking into account. Italian postwar colonial aspirations directly competed with British rule and interests in the area. This antagonism and the consequent efforts to set alliances with Somali communities not only exacerbated tensions among different groups but also reduced the range of discussions about future dispositions. Imperial antagonism in Somalia also contributed to shaping the spectrum of political associations by reflecting the tensions that dominated international affairs. In this way, the foremost nationalist movement, the SYL, came to symbolize the global quest for progress and modernity. On the other side, associations of the pro-Italia front were taken as proof of the pervasiveness of backward and traditional forces within Somalia that refused to conform to the new standards of progress. Ending up on the wrong side of this international dispute, the latter would bear the two-fold stigma of having backed the former colonial administration and, also, the former fascist power defeated during the war by Allied forces.Footnote 124

In order to shed light on the plurality of voices that arose following the change of regime one has to move beyond this simplistic binary approach to politics and political alignments in postwar Somalia. In an effort to do so, this article has built upon a growing body of literature that is devoting a renewed interest in the process of decolonization in the Horn of Africa.Footnote 125 At the same time, the article has also pointed to the importance of looking beyond nationalism and national movements. A scrutiny into pro-Italia voices illustrates how issues concerning land rights and access to resources informed political discourse and competition in postwar Somalia. Previous works have illustrated the connections between the struggle for land during the civil war in the 1990s and attempts of Siad Barre's regime to appropriate and redistribute land resources starting from the 1970s.Footnote 126 Looking at the postwar period helps putting this policy of ‘land alienation’ into a broader perspective; one that links back to pre-independence governments’ attempts to exclude minority associations from national politics.