1 Introduction

With the development of global markets and internationalization of trade, English for International Business (EIB) plays an essential function as a lingua franca (Rogerson-Revell, Reference Rogerson-Revell2007), as English language skills are an important tool for competing in the global economy (Graddol, Reference Graddol2006). Competence in English also plays a pivotal role in the success of many careers. Moreover, oral communication in English is an important aspect of the workplace and a required linguistic skill for business graduate students (Crosling & Ward, Reference Crosling and Ward2002; Forey, Reference Forey2004). Hence, upgrading the level of professional knowledge and English skills provided by the system of higher education is significant because it will help students augment their language skills and gain related abilities for their jobs in the future.

One of the goals of foreign language education identified by the Ministry of Education of Taiwan for vocational educational programs is to provide students with the foreign language ability and advanced professional knowledge necessary to succeed in the job market. This development trend has caused ESP instruction to be more greatly emphasized at technical universities in Taiwan during the last few years (Tsai, Reference Tsai2009; Tsai & Davis, Reference Tsai and Davis2008). However, there are some problems in the development of ESP courses in Taiwan. After investigating the relationship of the English proficiency level of about 350 students in four universities of technology, their needs when taking ESP courses, and their expectations of an ESP teacher, Lai (Reference Lai2005) found that: (1) learners’ main reasons for taking ESP courses are their relevance for future jobs in business or technology; (2) sufficient qualified teachers, authentic materials and specific knowledge were not provided; (3) the target need of students taking ESP courses is to be able to apply language skills such as listening, speaking, reading and writing.

Oral presentations in English are considered to be a required course in most ESP programs in Taiwan, as they are an important technique by which to enhance students’ communicative ability and to facilitate their learning. Presentation needs the same skills as daily conversation, but it is more highly structured, requires more formal language and a different method of delivery. In general, in addition to voice manipulation and bodily action, organization with a well-designed opening, body and conclusion is indispensable for a good presentation. How to effectively prepare a presentation text in the target language becomes an important issue. According to Chi's study (Reference Chi1996) investigating EFL students’ learning in combined speaking and writing courses in Taiwan, students did not know how to effectively apply what they learned in linguistic contexts.

With recent progress in information technologies, educational technologies provide learners and instructors with numerous advantages in the areas of contextual, active, self-paced and individualized learning, and automation. Through integrative computer-assisted language learning (CALL) which involved authentic uses of the language and interactive multimedia, language skills can be easily integrated for learners to practice listening (Romeo, Reference Romeo2008; Rost, Reference Rost1990), speaking (AbuSeileek, Reference AbuSeileek2007; Hsu, Wang & Comac, Reference Hsu, Wang and Comac2008), reading (Abraham, Reference Abraham2008), and writing (Chang, Chang, Chen & Liou, Reference Chang, Chang, Chen and Liou2008; Futagi, Deane, Chodorow & Tetreault, Reference Futagi, Deane, Chodorow and Tetreault2008). In addition, the integration of multimedia courseware into instruction has also become an effective tool for learning (Roblyer, Reference Roblyer2003; Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg2001). Brett (Reference Brett2000) indicated that well-structured multimedia courseware can provide a favorable learning environment to facilitate and improve language fluency. Recently, Tsai (Reference Tsai2010) reported on the development of ESP multimedia courseware for oral presentations, and its integration into self-learning and elective courses for EFL students in a technical university in Taiwan. EFL students benefited from multimedia courseware integration and such learner-centered instruction was as good as teacher-centered instruction as one solution to problems in ESP courses.

Although multimedia courseware development and its application in classroom lectures is becoming more greatly emphasized, its design and use have been more focused on courses related to sciences and technology (Azemi, Reference Azemi2008; Jiménez & Casado, Reference Jiménez and Casado2004; Shamsudin & Nesi, Reference Shamsudin and Nesi2003). That is because instructors in these fields have more competent skills and knowledge of multimedia software and programming so that they are less hesitant to convert their lecture notes into an interactive package that can be available to students. Consequently, the effectiveness of these new instructional tools has not been fully realized or studied in ESP which is an interdisciplinary subject that emphasizes the coordination and integration of learning subject knowledge and English skills.

2 Purpose of the study

Although the majority of students in higher education do not major in English, acquiring fluency in English communicative ability and competent presentation skills is nonetheless very important for them because English has been seen as an essential skill for conducting successful business in the workplace (Forey & Nunan, Reference Forey, Nunan, Barron, Bruce and Nunan2002). However, few studies have been undertaken to understand the learning performance and attitudes toward ESP multimedia courseware for oral presentations within the classroom for non-English major (NEM) students, who are generally less proficient in English and spend far fewer hours in studying English than English major students. Thus, the aim of this study is to understand whether or not NEM students with lower English proficiency can apply what has been learned from courseware integration into regular classes. In a multimedia courseware-integrated curriculum, computers play a central role as the means of information delivery, as a way to help students improve relevant linguistic fluency and enhance their skills in developing a presentation through their self-learning with the courseware. In this study, the learning effectiveness and concerns of NEM students are discussed from both quantitative and qualitative perspectives, and also compared with what English major students did in a previous study.

3 Instructional design

The courseware for integrating practices in English skills was implemented in a special elective program “English for technical presentation”, offered for two-and-a-half hours per week for five weeks. A computer-aided instruction (CAI) approach (Warschauer, Reference Warschauer and Fotos1996) combined with a task-based learning (TBL) approach (Nunan, Reference Nunan1989; Skehan, Reference Skehan1998) was adopted. In general, TBL includes three principal phases: Pre-task, During task, Post-task (Ellis, Reference Ellis2006). The task of the study is to ask students to write an English presentation text before and after their self-learning with the courseware.

During the pre-task phase, students had to conduct a written pre-test in which they were required to prepare a presentation text through which they not only previewed the task objective, but had to think ahead about how to do the task and plan the knowledge and language they would need. Then, based on students’ pre-test texts the teacher conducted one-on-one feedback for each student to provide them with a better understanding about what would be expected of the students while completing the task. Meanwhile, a questionnaire of concerns (QC) was administered to elicit students’ concerns about giving a presentation. During the task phase, the students self-studied with the courseware and the teacher mainly played the role of an observer or counselor. Such a role limited the teacher's intervention to working to understand students’ ability to handle autonomous learning and to apply what they learned to the post-test. During the post-task phase, students were asked to complete both a post-test and an open-ended questionnaire to provide some notion of student perceptions of their learning effectiveness through comments on whether or not they achieved some improvement in preparing a presentation text after their self-study with courseware in the previous phase. Then, based on students’ actual performance and their questionnaire reports, the teacher provided oral feedback including language forms that students were using, problems that students had with language and organization, and progress that students made. The methodology of this study was divided into two phases, Description of the instructional material, and Courseware integration into instruction, and are discussed in that order.

3.1 Description of the instructional material

The integrated courseware is based on Mayer's multimedia learning cognitive theory (Mayer, Reference Mayer2001, Reference Mayer2005) and its language learning focus draws on Chapelle's suggested criteria for development of multimedia CALL (Chapelle, Reference Chapelle1998). The courseware includes authentic texts with first language (L1: English) audio and translation support, narration, practice of language skills, on-line tests with instant self-checking; graphical images are all presented, both temporally and spatially, as shown in Figure 1. They are implemented in learner-paced segments so that students can control their learning pace and educational experience for repetition, deliberate practice and self-evaluation with the courseware.

Fig. 1 Bilingual buttons design for selecting sections and their learning topics and unit shown on the main page of the courseware

The content of the ESP courseware for presentations is divided into three thematic sections: Starting a presentation, During a presentation, and Terminology. Each section includes several topics, each with two or more learning units and on-line tests. A variety of sentence patterns commonly encountered in a presentation are provided in each learning unit to lead students into real-life situations and to engage in meaning-making (Brown, Collins & Duguid, Reference Brown, Collins and Duguid1989). Such a conversational style of multimedia learning with narration is intended to promote a better transfer and performance in retention tests, as stated in Mayer's (Reference Mayer2005) personalization principle. It provides learners with verbal interaction and visual aids which help increase their Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1962) and enables them to construct and promote their skills in problem solving for the task requirement. Thus, the well-structured content of the courseware plays a scaffolding role to help students develop or improve ideas and language skills for an oral presentation. The structure of each section in the courseware is explained as follows:

(1) Start a presentation consists of an introduction to the preparation for a presentation. This is outlined in order to help students establish an overall concept about a presentation. In addition, formal and informal salutations, and introducing oneself or others, are included.

(2) During a presentation includes three topics: (a) Beginning of a presentation (greeting, self-introducing, stating the purpose, length, and preview of the presentation); (b) Body of a presentation (focus on how to use techniques such as order, emphasis, generalizing, causes/reasons, contradiction, interrupting, reassertion, additions, and question-answer sequences); and (c) End of a presentation (summarizing, concluding, and closing the presentation).

(3) Terminology includes relevant vocabulary and technical expressions such as explanatory phrases for describing facts, possibilities, trends and comparisons, description of numbers and units, ratios, graphs and tables, and dealing with unexpected events such as technology glitches.

When any paragraph of the English text in the learning units is touched by the mouse, the color of the paragraph becomes blue, as shown in Figure 1. The paragraph is being spoken in English with L1 audio as learners click on the left button of the mouse. This allows learners to practice English reading skills, and helps improve the learners’ pronunciation and listening ability. Such subtitled multimedia courseware with L1 audio is similar to subtitled video, which positively enhances performance in listening and speaking, and promotes more efficient comprehension for second language (L2) learners (Herron, Morris, Secules & Curtis, Reference Herron, Morris, Secules and Curtis1995; Lund, Reference Lund1991; Rubin, Reference Rubin1994). This multimedia message combining written words with spoken language corresponds to Mayer's (Reference Mayer2001) modality and multimedia principles. It gives verbal and visual cognitive support and facilitates learning. In addition, learners can use the recording system offered by Microsoft Office to record their pronunciation, allowing them to practice their English speaking skills. After clicking the right button of the mouse, the Chinese translation and explanation of the paragraph will be simultaneously given in a pop-up window shown near the paragraph. This design corresponds to Mayer's (Reference Mayer2001) temporal and spatial contiguity principles.

An on-line test and evaluation system includes several language tests of varying difficulty, ranging from vocabulary gap-filling, sentence restructuring, listening tests to bilingual translation writing (Chinese to English, and English to Chinese). This system is provided for learners to practice integrative English skills: listening, speaking, reading, writing, and translation, as shown in the right-top of the learning window in Figure 1. When any test is selected, the questions in the test are randomly chosen by the program for learners to practice on. In addition, all these learning activities are combined with an instant self-checking system in order that learners can monitor their progress and test themselves immediately. If learners do not know how to answer the question, the L1 audio of the correct answer can be played by clicking the bell-button shown at the end of the question. This learner-centered cue design aims to reduce cognitive load and learning difficulty and help learners find the answer for themselves. This design is especially appropriate for learners with lower English proficiency, corresponding to the Prior Knowledge principle in Mayer's (Reference Mayer2005) Advanced Principles of multimedia learning. An example of the listening test is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2 The self-checking system for the listening test: the incorrect part of the learners’ reply is shown in red, and its reference answer is in green

3.2 Courseware integration into instruction

The courseware was implemented in a special elective program “English for technical presentation”, offered for two-and-a-half hours per week for five weeks. The course mainly focused on listening and writing, which are respectively related to learners’ input technique and output assessment of the task. Students were asked to write the text of four PowerPoint slides for a presentation, one involving real-life communication skills, before and after the use of the courseware.

The design of the course was as follows:

3.2.1 Target Audience

The program was selected by 11 NEM students from different colleges and backgrounds in a technical university in Taiwan: four graduate students from the Human Resources graduate school, five undergraduate students from the International Trade department and two undergraduate students from the Chemical Engineering department. The English proficiency of the students was determined by a simplified on-line TOEIC-like test in the pre-task phase. The TOEIC-like test included three test units with a total score of 445: multiple choice questions and answers about sentence patterns, a short oral discussion to assess listening skills, and a set of reading comprehension questions to provide understanding of their English proficiency, especially in listening and reading which are two main input channels for learning (Chen, Reference Chen2007; Chiu, Reference Chiu2006).

3.2.2 Learning context

The course was conducted in the multimedia laboratory. The courseware was installed on the laboratory server so that each student was able to easily access its content through their computers linked to the laboratory intranet.

3.2.3 Instruction

The multimedia courseware, as a silent partner, played the role of a peer and an adjunct language teacher with which students actively explored and interacted with content knowledge, at the same time practicing relevant linguistic fluency according to the curriculum schedule controlled by the teacher. In that sense, the courseware was a major medium for delivering and transferring subject content and language practices. The teacher supervised and observed students’ behaviors and learning, and encouraged their self-learning with the courseware.

3.2.4 Assessment

Written pre- and post- tests were conducted in the pre-task and post-task phases to provide evidence of students’ learning performance. The scores for these two tests were included in their grade, thus promoting the kind of student motivation that is generally characterized by the desire to obtain something practical or concrete from the study of a second language (Hudson, Reference Hudson2000). The two written tests were similar, and each included four PowerPoint slides. In the first two slides, students were asked to write the opening of a presentation, including greetings, self-introduction, objective introduction, schedule arrangement, and briefing. In the last two slides students could demonstrate their ability to describe more graphic, statistical and technical data, which is a very important skill in presentations. In addition, all the students’ written texts were collected, analyzed and measured by the Computerized Propositional Idea Density Rater (CPIDR) which is a computer program to determine the propositional idea density (P-density) of an English text automatically on the basis of part-of-speech tags (Brown, Snodgrass, Kemper, Hermen & Covington, Reference Brown, Snodgrass, Kemper, Hermen and Covington2008; Covington Reference Covington2007). P-density can be approximated according to the number of verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and conjunctions, divided by the total number of words in the text. It relates to the understanding and remembering of texts and some experiments have related idea density to readability, memory, and the quality of students’ writing (Kintsch, Reference Kintsch1998; Takao, Prothero & Kelly, Reference Takao, Prothero and Kelly2002; Thorson & Snyder, Reference Thorson and Snyder1984).

3.2.5 Questionnaire survey

A questionnaire of concerns (QC) was administered just after the pre-test to elicit what students were concerned about in giving a presentation, including fourteen items targeting four issues: English Ability (pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar, sentence patterns); Appearance (appropriate clothing, body movement, gestures); Preparation of PowerPoint (layout choice, information per slide, background choice); and Performance (volume, intonation, pauses, stress). Meanwhile, students were asked to choose their three greatest concerns from among these fourteen items in the pre-task phase. After the post-test, an open-ended question was asked, in order to understand students’ comments on whether or not they achieved some improvement after self-studying with courseware integration for about 12.5 hours, especially regarding their three items of greatest concern.

4 Results

Students’ evaluation and evidence of integration was seen through completion of the written pre- and post- tests, a questionnaire of concerns, and an open-ended question. The choices students selected for each question in the questionnaires were averaged and the standard deviation (STD) was analyzed. All valid responses were input and filed for statistical data analysis using SPSS. This analysis, doing the pairs and independent samples t-tests, focused on learning concern, effectiveness and attitude of the students in order to understand if there were any significant differences existing among the factors mentioned above. An acceptable significant level for each statistic was at .05 in this study.

4.1 Text analysis

Students were asked to prepare four PowerPoint slides for a presentation as pre- and post-tests. The first two slides were expected to demonstrate whether or not students could give a complete opening for a presentation. Five items, which were presented in the second section, “During a presentation”, of the courseware learning units, need to be considered. Eleven NEM students completed the pre- and post-tests. The frequency in percentage that students wrote for each item is given in Table 1.

Table 1 Frequency for the items given in the first two slides of NEM students’ pre- and post-tests

*p < .05.

The result indicated that the frequencies of all the items in the students’ texts for the post-test were higher than those in the pre-test. Moreover, all the students gave a self-introduction and briefing in the post-test. A further paired samples t-test analysis shows that there was a significant difference in the fourth (schedule arrangement) item between the pre-test and the post-test.

Students’ speech texts for the pre- and post-tests were collected, and then analyzed by the software CPIDR which allows researchers to gain an impression of the text quality by determining the P-density. The analysis through the paired samples t-test for the idea count, word count and P-density of students’ speech texts for the pre- and post-tests is shown in Table 2; this demonstrates that the means of idea count, word count and P-density in the post-test were significantly higher than those in the pre-test (p < .05). In addition, the mean P-density of the students’ text in the post-test was 0.459, an increase of 13.9% from 0.403 in the pre-test and close to the P-density (0.470) measured from all collected sentence patterns provided in the courseware. Such an increase in P-density in students’ post-tests revealed that NEM students could apply what they had learned from the courseware to prepare speech texts so that their writing quality in the post-test was significantly improved.

Table 2 Paired samples t-test analysis of NEM students’ speech texts of the students

4.2 Questionnaire of concern about giving a presentation and results of open-ended question

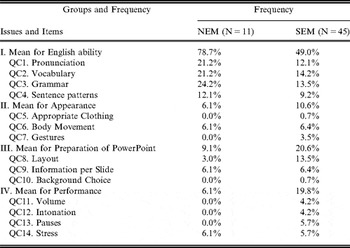

During the pre-task phase, students completed the questionnaire of concern in order to choose their three greatest concerns from fourteen items. The frequency for each item chosen by students is collected and shown in Table 3. Comparison of the mean of each issue showed that NEM students were much more concerned about English ability (78.7%) which is related to basic language skills for communication, including grammar (24.2%), pronunciation (21.2%) and vocabulary (21.2%), and sentence pattern (12.1%), but much less concerned about three other issues, Appearance (6.1%), Preparation of PowerPoint (9.1%), and Performance (6.1%), that are all related to a higher level of skills for oral presentation.

Table 3 Results of students’ questionnaire of concern before learning with the courseware

NEM: non-English major students; SEM: students with English major (Tsai, Reference Tsai2010).

After students’ self-learning with courseware integration, an open-ended written question was administered regarding students’ self-evaluation and their expectations for sustaining learning in the future. Most of the students clearly indicated that they had made some improvement or progress in their three items of greatest concern after self-learning with the courseware. The main areas highlighted by the students include improvement in varied linguistic skills, better understanding about preparation for speech texts, useful (or helpful) instruction through courseware integration combined with a teacher's coaching, bilingual design of the courseware; opportunities for practice in a stress-free environment. In addition, some students hope to have the opportunity to do a stage performance. Students’ responses are summarized below.

In the beginning, I had no idea of how to prepare a text for presentation. However, after five weeks’ study with courseware integration, I though I can perform better now than other classmates who have not taken this course. I knew more about how to start a presentation and prepare for different steps in a presentation, and meanwhile I learned some terminology. (Student A)

Through repeated practice with the courseware, I found my listening and writing abilities were improved, and also learned lots of vocabulary. Bilingual texts gave me a better understanding. I hope to have more opportunities to practice speaking with peers. (Student B)

At first, I felt strange, nervous and afraid to write down the text for a presentation. During this five-week’ study, I gradually liked learning with courseware integration which provided a fearless learning environment. One-on-one coaching was very helpful, which allowed me to understand better what my problems in grammar or writing were. (Student C)

In the beginning, I felt my English was not good. I felt improved in vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation through repeated practices with the courseware. In addition, teacher's coaching really gave me more confidence for learning with courseware. I had less fear of preparing a presentation in English. (Student D)

The most improved item for me was to understand how to use sentence patterns in different situations of oral presentations. However, body movement was not taught under such courseware integration. (Student E)

After five-week's study, I had a deeper understanding of preparing presentation texts. I knew how to use simple words to express myself. It was very helpful. Besides, my listening and pronunciation were improved. (Student F)

I thought that presentation in English was a tough task. However, after five-week's study, I understood better how to perform a presentation and apply sentence patterns offered by the courseware to real-life situations. I felt more confident to perform a presentation in English in the future career. Of course, it will be better if students can conduct stage performance. As teacher's suggestion, I have to practice English everyday in my free time to keep global competitiveness for the future. (Student G)

5 Discussion

This study aimed at integrating the ESP multimedia courseware for oral presentations into task-based learning in which computers played a central role in helping students to construct and promote content knowledge learning and improve communicative ability through their direct interaction with the courseware. The discussion is divided into two parts as follows:

5.1 Text analysis

As shown in Table 1, the text analysis by CPIDR for the pre- and post-tests indicated that NEM students gave a significantly better opening for a presentation after self-studying with the courseware, which provided a sequence of situational contexts to facilitate students’ construction of a well-structured beginning for a presentation. The analysis and the paired samples t-test showed that the means of idea count, word count and P-density in the post-test were significantly higher than those in the pre-test, as shown in Table 2. It meant that NEM students had a significantly better performance in writing quality and quantity after their self-learning with the courseware.

In addition, when compared with 45 sophomore students with English majors (SEM) in a previous study (Tsai, Reference Tsai2010), NEM students showed significantly lower values in the scores of the TOEIC-like test, idea count, word count and P-density of speech texts in the pre-test than SEM students; this revealed that NEM students had significantly lower English proficiency, writing quality and quantity than SEM students at the beginning of the study, as shown in Table 4. After five weeks of self-learning, although NEM students still had fewer ideas and words than SEM students in the post-test, there was no significant difference in idea count, word count and P-density between NEM and SEM groups. Moreover, students’ mean P-density (0.459) in the NEM group was not only close to that of the SEM group (0.465), but it was also close to the P-density (0.470) of the courseware content. This result implied that NEM students with lower English proficiency benefited from self-learning with the courseware which provided useful and practical sentence patterns for English presentation, so that their writing quality was improved to some extent.

Table 4 Independent samples t-test analysis between non-English major students and sophomore students with English major

*p < .05 significant difference existing in the pre-test between Non-English major and English major groups.

In general, writing requires some conscious mental effort and is considered to be the most difficult and challenging task of the four language learning skills. While composing an article, learners need not only to create and organize their ideas, but also to transform them into meaningful text in English. Thus, it was a tough task to ask NEM students to perform as well as SEM students. Although NEM students could not write as many as ideas or words as SEM students, their performance improved significantly through five weeks of learning with courseware integration, especially in the quality of their writing.

Since the analysis of students’ speech texts by CPIDR is just a simple and quick measure of lexical proficiency, a detailed analysis can be further conducted to provide insight into deeper, cognitive measures of L2 writing lexicons such as the development of word senses and lexical networks, which could lead to a better understanding or awareness of how L2 learners process and produce lexical acquisition.

5.2 Questionnaire of concern about giving a presentation and results of open-ended question

According to the results of the questionnaire of concern shown in Table 3, NEM students were much more concerned about the issue of English ability such as grammar, pronunciation, vocabulary, and sentence pattern, than three other issues: Appearance, Preparation of PowerPoint, and Performance. If further compared with SEM students (Tsai, Reference Tsai2010), an independent sample t-test analysis showed that there was a significant difference in concern between NEM and SEM students in the following items: gramma, gesture, layout, volume, intonation, and pauses. Moreover, except on the item of grammar, NEM students had lower scores than SEM students in the other five items that are related to a higher level of presentation skills. This result suggested that students with different English proficiency had different concerns about preparing a presentation. Learning how to use appropriately a higher level of skills for animation and emphasis in a presentation is especially important for the students with higher English proficiency, but students with lower English proficiency need more linguistic support to enhance their language ability in preparing speech texts.

In addition, from the results of the open-ended written question, most students clearly indicated some improvement or progress was made in their three items of greatest concern after learning with multimedia courseware integration. The satisfactory or beneficial factors that students explicitly mentioned included improvement in varied linguistic skills, better understanding about preparation for speech texts, useful instruction through courseware integration combined with coaching by a teacher, the bilingual design of the courseware, and the opportunity to practice in a stress-free environment.

Although this study was based on a limited number of students, the response above not only suggested evidence of successful courseware design and the effectiveness of its integration into the learning environment, but also provided some indications of how ESP instruction with multimedia courseware integration might be applied in other contexts:

Firstly, the courseware as integrated into this task-based learning responds to an increasing awareness in the ESP teaching that the curriculum frame should integrate three essential fields: content knowledge, business practice and language skills (Zhang, Reference Zhang2007). The coherent layout of the courseware with three sequential thematic sections and related topics and learning activities, succeeded in making students aware of a variety of sentence patters and vocabulary commonly occurring in different situations during a presentation. After five-weeks of self-learning with the courseware, students were able to better understand how to prepare a presentation in English and apply what had been learned so that the quality and quantity of their writing in the post-test measured by CPIDR analysis was enhanced and they demonstrated a conscious improvement in varied linguistic skills.

Next, since the courseware included authentic texts with L1 audio and translation support, narration, practice of integrative language skills, and instant self-evaluation functions, the computer functioned as a peer or an adjunct teacher with which students had direct interaction, allowing them to practice language skills, receive questions, and think of the answers for meaningful learning in the target field. In addition, according to the teacher-as-researcher's observation within the class, most of the NEM students’ questions related to grammar and writing due to their lower English proficiency. They were usually not sure whether what they wrote was grammatically correct and they did not have the confidence to know how to express themselves in a simpler and more effective way. Thus, more supportive linguistic help, either from the teacher or the courseware, is necessary in learner-centered instruction for students with lower English proficiency, to allow them to learn in a more motivated and less fearful environment (Gu, Reference Gu2002; Jeon-Ellis, Debski & Wigglesworth, Reference Jeon-Ellis, Debski and Wigglesworth2005; Tan, Gallo, Jacobs & Lee, Reference Tan, Gallo, Jacobs and Lee1999).

In fact, in order to develop a favorable learning environment for task-based ESP learning in this study, the teacher intervened in the pre-task phase to offer individual supportive feedback or guidance in language forms and subject content. Moreover, on-line evaluation of the courseware also provided students with an instant self-checking function. These auxiliary supports should be considered especially useful for learners with lower English proficiency such as NEM students, in order that their confidence, motivation and engagement might be enhanced for the promotion of language fluency and content knowledge in a less threatening environment.

Furthermore, students using the courseware had greater opportunities to integrate their English skills at their own pace and according to need during their learning process. Such integrative language practices through the multimedia courseware will be much more helpful within a typical class with an average class size of 50 students or above. This feature not only met the needs of Taiwanese students taking ESP courses, but also reinforced the importance of the integration of language skills that has been emphasized by, for example, Kumaravadivelu (Reference Kumaravadivelu2003), based on theoretical and experiential knowledge.

It was a new experience for NEM students to learn and study through task-based ESP learning with multimedia courseware integration, where they needed to take more responsibility for their learning. A few students mentioned their preference for teacher-centered instruction and hoped to get more interaction and explanation from the teacher. However, in view of new trends toward e-learning, either in higher education or later, in the workplace, students will need to learn how to take more responsibility for their learning, and this will especially be the case with learning with multimedia courseware. Courseware integration requires them to engage more actively in the cognitive processes of selecting, organizing, integrating and applying what they acquire in the learning process. Thus, expanded abilities and more positive attitudes toward e-learning are important new literacies that most educational institutions now urge students to establish. This will allow them to be able to conduct lifelong or continuing learning on their own after graduating from school.

6 Conclusions and implications

Integrating technologies into language instruction has become a reality for teachers of English to speakers of other languages (TESOL) practitioners. Meanwhile, students around the world increasingly need both English and technology skills for their future careers in the workforce (Shetzer & Warschauer, Reference Shetzer, Warschauer, Warschauer and Kern2000). To integrate multimedia courseware into task-based ESP learning, students have to not only improve their English proficiency, but also learn to communicate effectively in the target field that they wish to join after academic life. In order to find some possible solutions to problems in the development and expansion of ESP courses in Taiwan, the aim of this study was to integrate ESP multimedia courseware for presentations into a self-learning course. Evaluation of this implementation is based upon data from pre- and post-tests, student questionnaires of concern, and an open-ended question. Although this study was based on a limited number of students, learning effectiveness under such learner-centered instruction with courseware integration has been achieved as follows:

(1) The well-structured multimedia courseware in this study functioned as a tutor and facilitator through which students were able to apply what they had learned to complete the task. Thus, after active participation and self-learning with the courseware, non-English major students significantly improved their learning effectiveness in terms of writing quantity and quality in preparing speech texts for a presentation.

(2) Students with different English proficiencies have different concerns. NEM students with lower English proficiency were much more concerned about English ability (78.7%) which relates to basic language skills for communication, including grammar (24.2%), pronunciation (21.2%), vocabulary (21.2%), and sentence pattern (12.1%). They need more linguistic support to enhance their language ability in preparing speech texts.

(3) After self-learning with the courseware, most of students clearly indicated that they had made some improvement or progress in their three items of greatest concern. The main areas where students reported improvements were varied linguistic skills, better understanding about preparation for speech texts, favorable learning through courseware integration combined with teacher's coaching, bilingual design of the courseware, and practice in a stress-free environment.

How to keep improving both the instructional method and its medium, by using multimedia or technology tools to create a more motivated, interactive, stress-free and unconstrained environment, is always a great challenge for teachers in the digital era. The fullest collaboration in ESP teaching is often said to be one where a subject expert and a language teacher team-teach classes (Dudley-Evans & St John, Reference Dudley-Evans and St John1998). However, such teaming has not been feasible in vocational higher education in Taiwan for several reasons, such as lack of qualified teachers, difficulty in collaboration or relevant curriculum design. Based on the experience and results in this study, the well-structured ESP multimedia courseware integration with a teacher's intervention in the pre-task phase did offer a potential solution to problems in the development and expansion in frequency of ESP courses in Taiwan to meet learners’ needs relating to professional knowledge and language skills.

Development of ESP multimedia courseware is an interdisciplinary task and creating teacher-customized courseware to be incorporated into a regular classroom asks a lot from teachers in terms of willingness and contribution to content design and curriculum planning. However, students’ positive attitude toward courseware integration into ESP instruction implies that the courseware, incorporating L1 audio with paragraph subtitles and their translations, can be an instructional tool to support an approach to ESP in higher technical education in which students’ English skills and comprehension can be promoted. Thus, in order to better determine and understand the full impact of such courseware integration, more classroom-oriented research is required to further analyze and discuss learning effectiveness, attitude and strategies of learners with different educational and working backgrounds toward ESP instruction with multimedia courseware integration. In addition, through collaboration with other departments and industries, the development of ESP multimedia courseware can be expanded to more professional subjects in order to enhance the professional and English skills of learners in different fields.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank most sincerely Dr. Boyd Davis, Professor of Applied Linguistics/English, University of North Carolina-Charlotte (USA), for her valuable suggestions during this study.