Introduction

By 2003, the Asia-Pacific arm of a global professional services firm was heading for a serious fall. Characterized in the business press as a ‘sick puppy,’ the (hitherto named) ‘Firm’ not only lagged behind its competitors, but also seemed destined for second tier relegation. In this grounded research case study, we present the Firm’s organizing response enacted by the 2003-appointed Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and his newly appointed senior management team. This case study reveals how the tension between exploration and exploitation can be used productively in organizing, but requires a high level of tolerance for uncertainty accompanying the ostensible pursuit of contradictory tensions.

The case takes its initial motivation from the tangible success the Firm produced in the 10 years between its ‘sick puppy’ period in 2003 – encompassing two global financial crises – and its emergence as a billion dollar firm with an envious growth rate. This research asks how a large firm delivers on efficiency and control at the same time as flexibility and innovation through its organizing forms. To answer this question we began with an interpretive mindset (Isabella, Reference Isabella1990), assuming that organizational actors create and enact their own social realities (Berger & Luckmann, Reference Berger and Luckmann1967). Furthermore, their realities are likely to be shared and heavily influenced by senior members as well by the maturing, meaning-making nature of time and reflection (Deetz, Reference Deetz1996). Context was therefore sovereign, our approach mirroring Galvin’s (Reference Galvin2014) description of an ‘inside out’ research focus where the chief issues hold particular salience within a specific environment. In building a model to describe the case organization’s response, our aims go beyond understanding the single context as the results might be employed to later extend theory for superior generalization.

The study utilized data collected from in-depth interviews, supplemented by data obtained from ethnographic techniques. Data were analyzed with grounded methods consistent with Whiteley’s (Reference Whiteley2004) ‘grounded research.’ It departs from a steadfast grounded theory methodology in the Glaser and Strauss (Reference Glaser and Strauss1967: 32) conceptualization, in favor of a ‘pragmatic’, modified version attuned to the business setting but holding faithful to ‘theoretical sensitivity’ where emergent data are considered in light of existing theory.

Our initial research question emanated from the explore–exploit problem, and most particularly, the absence of case data revealing how it has been addressed in practice. Organization theory literature engages with the explore–exploit problem through concepts such as dualities (and tangentially through ambidexterity). In fact, the dualities literature (Graetz & Smith, Reference Graetz and Smith2008; Farjoun, Reference Farjoun2010) offers a theoretical platform for conceptualizing the tensions that arise when organization’s seek efficiency and innovation simultaneously by introducing structures responding to both at the same time (Smith & Lewis, Reference Smith and Lewis2011). However, little empirical work – especially from cases – exposes how: first, dual organizing forms can stimulate innovation (explore) without sacrificing efficiency (exploit); and second, how dual organizing forms can deliver a legacy after discontinuation. The grounded research (Whiteley, Reference Whiteley2004) method allowed for a model indigenous to the case firm to emerge in order to provide some suggested avenues for better understanding the utility of a duality-driven organizing form for addressing the explore–exploit conundrum.

To foreshadow, our results reveal a complex network of concomitant explore and exploit activities. It depicts a response to the explore–exploit paradox where switching emphasis and resources between the two priorities failed, leading to a novel combination of heavy exploitation-driven actions alongside deep exploration projects. Most pointedly, the organizing response was fluid. For example, the Firm created a new major business unit, liberated it from the demands of normal operations, placed an entrepreneurial maverick in charge, and supported it like a start-up. As the unit became successful it was spun back into the mainstream business, and another, more advanced iteration spun out again as another change stimuli. Not only was the approach successful in driving new innovation, it also had a powerful cultural impact on the normally intractable exploit side of the business. The deeply conservative business clusters impelled by incremental monthly targets started to engage with the Firm’s ‘rise and fold’ innovation projects.

Grounded theory allows for an initial separation between ‘substantive theory’ (from extant literature) and ‘grounded theory,’ allowing the researchers some interpretive space to comprehend the social reality of the research site and its actors without having to make it fit a preconceived structure. As Glaser and Strauss (Reference Glaser and Strauss1967) originally declared, substantive theory provides a strategic link to grounded theory; the two converge. For example, Strauss and Corbin observed that, ‘… all kinds of literature can be used before a research study is begun …’ (Reference Strauss1990: 56). While our approach does begin with an awareness of substantive theory, it does not strictly adhere to Glaser’s (Reference Glaser1992) original principle of emergence, where data are generated purely from induction and without any prior contact to theory. As a result, like Whiteley (Reference Whiteley2004) and Suddaby (Reference Suddaby2006), our approach does not assume that prior knowledge presents a contamination danger so long as researchers avoid hypotheses testing instead of directly observing the results from the actors’ perspectives. Grounded methods – under the banner of Whiteley’s (Reference Whiteley2004) ‘grounded research’ rather than ‘grounded theory’ – therefore can be useful in allowing organization studies researchers to understand the ‘research questions’ driving their case organizations. This final point provides us a departure into some concepts connecting our data with the literature, and helps to contextualize the forthcoming language and paradigm governing what the Firm’s leadership realized was their ‘daily’ organizing challenge.

Our approach acknowledges the prior knowledge that duality theory offers about our explore–exploit research question, but does not employ a priori hypotheses for testing against data. We therefore position our analytical approach as interpretive, informed by a theoretical platform framing the research problem, but inductive in that a naturalistic inquiry method was used consistent with the method advocated by Lincoln and Guba (Reference Lincoln and Guba1985) in order to allow for an emergent presentation of the primary data. Lincoln and Guba (Reference Lincoln and Guba1985) note that a naturalistic inquiry should outline its theoretical perspective. As a result, the naturalistic inquiry approach utilized in this research employed a conceptual coding method (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss1990). Our approach was guided by Denis, Lamothe, and Langley (Reference Denis, Lamothe and Langley2001), who like Whiteley (Reference Whiteley2004) outlined how nascent theory can be explored and developed by starting with a theory-inspired problem and pursuing it with a detailed inductive procedure. We began with the explore–exploit problem inspired by duality theory, and used conceptual coding to compile the data into themes relevant to the case firm’s response to the problem. In this research we selected a single case study as the research site.

We suggest that the use of a naturalistic method employing grounded research has proven productive in allowing the details of this case to be exposed in a manner consistent with the experiences and interpretations of its respondents. For example, although we began our study with an expectation of its principal connection to organization theory, the data told a different story; one that involved increasing rather than resolving tension and contradiction. From this perspective, case methods are receptive and adaptable to the often numerous, mutually shaping influences and value patterns that may be encountered in an organizational context.

In the following sections we address the literature associated with our findings, including background concerning the explore–exploit tension and dualities. Following on, we profile the study’s research design in detail before presenting and discussing the results of our coding analysis. The article culminates in a model seeking to answer the research question, leading to sections offering theoretical and practical implications followed by conclusions.

Dualities and Organizing

The ‘explore–exploit’ conundrum has been connected to an organizing forms duality tension emanating from what are, at least superficially, contradictory modes of operation (Graetz & Smith, Reference Graetz and Smith2011). From a theoretical perspective, Smith and Tushman (Reference Smith and Tushman2005: 523) defined exploitation as ‘variance decreasing’ based on ‘disciplined problem solving’ and exploration as ‘variance increasing’ through trial and error experimentation. Exploitation is concerned with stability and continuity; it draws on and builds from an organization’s past, aiming to increase efficiency and profitability of the current business model. Exploration is concerned with change and adaptability; encouraging creativity and risk taking, and tapping into new, untested markets and opportunities (Smith & Tushman, Reference Smith and Tushman2005; Groysberg & Lee, Reference Groysberg and Lee2009). In short, duality theory proposes organizing for innovation and commercialization at the same time.

In 2003, the Firm’s new CEO and his executive team encountered the challenge of how to devise structures that facilitate exploration for future growth while also exploiting for current prosperity. They recognized that dual mode of operation – also advocated by O’Reilly and Tushman (Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2004) – required different organizing forms thinking at the same time. Impelled by the mobilizing vision of becoming the ‘number two’ professional services firm, the conservative firm committed to instilling innovation, captured in their declaration to be ‘different.’ Being different proved a reference to more than just the Firm’s client services. At the heart of change was an entirely new operating prescription, transitioning from the ‘right to innovate’ to, in the CEO’s words, ‘a responsibility to innovate.’ Rather than just seeing it as an issue of strategizing, the new team regarded the duality paradox as an organizing problem, presenting a deep challenge to the engrained culture of the professional services firm. High levels of exploration and exploitation mean dealing with completely different imperatives and structures in a business as ‘mutually enabling constituent’ parts (Farjoun, Reference Farjoun2010: 205). Moreover, professional services firms ‘are not generally equipped to cope with fragmentation and high ambiguity’ (Seo, Putnam, & Bartunek, Reference Seo, Putnam and Bartunek2004: 162). For the most part, their core business resides with long-standing, conservative and legalistic services based on trust, security and efficiency.

Previous research shows that even with the right people, organizational structures, systems and processes constrain dual thought and action (Ghoshal & Bartlett, Reference Ghoshal and Bartlett1995; Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst, & Tushman, Reference Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst and Tushman2009). After all, professional service firms need control and efficiency to continually deliver on their profit targets. As a result, large firms face the difficulty of balancing organizing control mechanisms through their executive planning, performance measurement and reward systems, and client delivery processes, against freedom for new innovations (Jansen, van den Bosch, & Volberda, Reference Jansen, Van Den Bosch and Volberda2006; Lubatkin, Simsek, Ling, & Veiga, Reference Lubatkin, Simsek, Ling and Veiga2006).

The struggle to balance basic organizing tensions (Asch & Salaman, Reference Asch and Salaman2002) threads through the organizing forms literature, including commentaries on pressures to differentiate and integrate, the need for controllability and responsiveness, and ambidextrous forms encapsulating explore (premised by efficiency, stability and control) and exploit (invoking innovation, adaptability and risk taking) domains, as the ideal architectures for simultaneous tight and loose organizing (Evans, Reference Evans1999; Benner & Tushman, Reference Benner and Tushman2003). Where ambidextrous forms of organizing were seen to reflect a ‘mix and match’ approach (Jackson & Harris, Reference Jackson and Harris2003), comprising interactions or ‘sequencing’ between explore and exploit organizing poles, duality theory advocates for triggering a ‘productive’ tension. While some ambidextrous approaches prescribe sequential or temporal switching between exploitative and explorative goals as a means of easing or resolving tensions, duality theory argues for juxtaposition. As Lewin, Long, and Carroll (Reference Lewin, Long and Carroll1999) observed, in robust (dynamic) systems, a constructive tension emerges between order (the pull of exploitation) and disorder (the pull of exploration), often described as the ‘edge of chaos.’ Divergent, creative ideas depend on convergent, analytical thinking for nurturing and support. A duality approach recognizes that contradictions and complementarities necessarily coexist to leverage performance (Whittington & Pettigrew, Reference Whittington and Pettigrew2003). In short, dualities involve the simultaneous and equally charged pursuit of creativity, innovation and speed while maintaining coordination, focus and control (Volberda, Reference Volberda1998).

Research Design

This 24-month study aimed to capture and explain one firm’s organizing forms response to the explore–exploit challenge, motivated by the initial observation that the approach had been successful over a 10-year period. Case studies enable the identification of dynamics present within single settings (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989), operate under specific contexts (Daymon & Holloway, Reference Daymon and Holloway2002), and require detailed, rich data in order to be understood. Case studies also allow the researchers to understand organizational events and issues from the perspective of different organizational stakeholders (Gillham, Reference Gillham2000a, Reference Gillham2000b) and where ‘human agents and organizational structures’ intersect (Sjoberg, Williams, Vaughan, & Sjoberg, Reference Strauss and Corbin1991: 55). While case study methodology is sometimes criticized for its lack of generalizability, relevant to our approach is Yin’s (Reference Yin2009: 15) argument that case study findings are generalizable to ‘theoretical propositions,’ not simply organizations or populations. Farquhar (Reference Farquhar2012) similarly argued that the primary intent of the case study approach is to conduct an in-depth study of a single case or multiple cases, rather than generalize findings. In addition, the evidence collected in cases is ‘grounded’ in the social setting being studied (Jennings, Reference Jennings2001), strengthening its validity. As Glaser and Strauss (Reference Glaser and Strauss1967) claimed, the goal of exploratory case studies is to discover theory by directly observing social phenomena in its raw form, further encouraging our selection of grounded techniques as a research procedure to tackle the contextually situated organizing activities transpiring in the Firm.

As an inductive procedure, grounded research seeks to identify conceptual categories arising from the data using what Glaser and Strauss (Reference Glaser and Strauss1967) named the constant comparative method. It works through an ongoing interrogation of the incidents observed in the data and the emerging theoretical concepts. We compared the contents of each interview’s data units as well as 24 months of ethnographic observations as they were examined, with the aim of specifying the common and diverging themes. Our procedure employed theoretical sampling to select the next interview, adding depth and perspective to the emerging codes. As themes evolved and matured, common concepts became apparent, which were subsequently used to generate data categories. The categories provided the foundations for theory development, thereby finalizing the process of theoretical sensitivity. Thus, as our codes demonstrate, the focus was upon capturing and explaining the action and interaction strategies of organizational actors (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss1990).

Data collection

Unstructured, in-depth interviews were conducted with the senior executive of the Asia-Pacific arm of the Firm, as well as interviews with a theoretical sample of senior partners, innovation directors and managers, and project leaders across the Firm who played pivotal roles in shaping, and responding to, its organizing form initiatives. We used theoretical sampling as a method of progressing the constant comparative analysis (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998). Sampling theoretically involved selecting each successive interview candidate on the basis of analytic need. We followed the interview management protocol outlined by Minichiello, Aroni, and Hays (Reference Minichiello, Aroni and Hays2008) in the form of analytic induction, a detailed, grounded, constant comparison process. This protocol encourages a complete analysis of each interview before making decisions about the next selection, in turn driven by the intention to address the gaps remaining in the theoretical concepts, categories, propositions or entire theory, depending upon proximity to data saturation. We used memos and data cross-checking between independent coders to choose interview respondents with anticipated viewpoints relevant to the confirmation or disconfirmation of the emerging theory. Such a process can be imperfect due to incorrect assumptions about a respondent’s perspective, their availability, and the choice of whether the theoretical uncertainty would be better engaged with a confirming or disconfirming position. As Minichiello, Aroni, and Hays (Reference Minichiello, Aroni and Hays2008) advised, continuing the process until saturation is the best response.

One specific business unit of the Firm, ‘TechFirm,’ a unique, semiautonomous innovation-driven entity, was examined through an interview census of its members. In addition, ethnographic data were collected through a series of participant observations undertaken over several months. Participant observation combined participation in the occupational lives of the members of TechFirm while maintaining a professional distance allowing adequate observation and data recording (Fetterman, Reference Fetterman1989). Our participant observation included three elements: watching what people did; listening to what they said, and periodically interjecting to ask clarifying questions (Gillham, Reference Gillham2000a, Reference Gillham2000b). Like Pettigrew (Reference Pettigrew2000), we suggest that grounded techniques and ethnography are compatible, mainly due to the shared naturalistic assumptions inherent to both methods. For example, each focuses on observing and analyzing behavior in context. All observations were recorded as transcribed notes and added to the interview data for coding.

Finally, interviews with purposefully sampled representatives liaising with the Firm and TechFirm from the London, New York and San Francisco offices were also undertaken to assist in establishing context. In total, 32 formal interviews were conducted, transcribed and coded, excluding the numerous repeat interviews informally undertaken as part of the participant observation. Interviews were video-recorded as well as audio-recorded, the former used by the researchers to assist in reviewing memos and theoretical notes. All audio data were transcribed and organized within the qualitative software NVivo 10. This computer-aided software provided structural and therefore practical assistance in the coding of more than 350,000 words of data. While NVivo offers some analytical tools, we built our theoretic structure through a rigorous process of constant comparison, theoretical sampling and intercoder cross-checking. Notwithstanding the complex debates surrounding variations in grounded analysis, we favored Strauss and Corbin’s (Reference Strauss and Corbin1998) general theory of action to build an axis for an emerging theory.

Data analysis

Interviews and observational data were transcribed word for word. As grounded research our conclusions emerged from a detailed, line-by-line investigation of the interview and observational data, coded in three (in two cases four) thematic, hierarchical layers. Our subsequent theory building escalated these codes into concepts, categories and ultimately theoretical themes. The outcome of this iterative and inductive process was four ‘open’ codes constituting (1) Models and Concepts, (2) Actions, (3) Interactions and (4) References. These initial codes correspond generally to Strauss and Corbin’s (Reference Strauss and Corbin1998) four factors of chief interest: conditions, strategies and tactics, interaction among the actors, and consequences. Including the second ‘axial’ tier of coding, the third ‘selective’ tier, and a fourth ‘selective subnode’ tier where needed, our results produced 99 coding categories. The conceptual and theoretical implications of our analysis have been formulated on the basis of a constant comparative method that interrogated these themes as they were developed until the point of saturation.

Data analysis occurred during the research process and took place after each interview in order to make constant comparisons. Transcripts and video were first broadly studied to gain a general familiarity of the contents. During this process, dominant themes were noted to form the codes with which the transcript was interpreted and meanings developed. We used the codes to structure and organize the data and analytical process, including the revision of notes, video and audio tapes (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994). The codes acted as tags or labels for assigning units of meaning to the descriptive or inferential information compiled during research. Subsequently, these codes were attached to ‘chunks’ of varying size; words, phrases, sentences or whole paragraphs (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994). During the coding process, keywords were applied to sections of the text, providing specific meanings to the text as well as a label for the section. Labels were selected that best described the conceptual contents of each code. In order to determine whether a code was correctly assigned, the coders compared text segments to earlier data already allocated the same code. Using the constant comparison method, the coders then determined whether the new data reflected the same code or justified the creation of a new code.

Coding was undertaken in three stages (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1994), open, axial and selective, although the selective codes were only used in two out of four open codes. However, for the larger two open codes, we added a fourth tier of coding in the form of ‘selective subnodes.’ The open stage of coding involved breaking down, examining, comparing, conceptualizing and categorizing data (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss1990). Once particular phenomena had been identified in the data, concepts were grouped around them in axial coding before being categorized through selective and selective subnodes. During the coding process, ‘theoretical sensitivity’ was used to carefully process the data. Strauss and Corbin (Reference Strauss and Corbin1998) described theoretical sensitivity as the ability to recognize important elements in the data while giving it meaning.

Theory building

By constantly comparing data, a model evolves, subject to interrogation at successive iterations of data collection. Our model focuses on relationships between explanatory variables, seeking to establish the causal antecedents; it aims to predict and explain. While the model draws heavily on the coding outcomes as a data synthesis – the basic units of theory organized into categories – it goes beyond the codes to establish relationships and infer causality (Strauss, Reference Sjoberg, Williams, Vaughan and Sjoberg1995). Our approach was to translate categories articulated through the detail of selective codes into themes, which we subsequently used to create generalized relationships between categories and their contents.

Data credibility was sought through investigator triangulation where two individuals were involved in the interviewing process. As Lincoln and Guba (Reference Lincoln and Guba1985: 307) observed, multiple investigators help to keep each other ‘honest.’ This process was further bolstered through peer debriefing where the interviewers subjected their working observations to the scrutiny and analysis of a team member not involved in the interviews. Transferability was sought through a comprehensive cataloging of the details concerning the research methods, contexts and assumptions underlying the study. A theoretical sample was employed and the conceptual constructs, coding themes, labels and categories used in the study were rigorously recorded so that they might be transported to other research contexts. In addition, contextual data such as annual reports, written descriptions of the physical environment, historical developments and current issues identified on the firm’s website and social media platforms were collected in order to help locate the data within a practical, situational framework. This process extended to conducting interviews with international Firm counterparts.

Dependability was sought through theoretical sampling, emphasizing the application of judgment and deliberate effort to locate theoretically relevant data sources including both common and divergent perspectives. In addition, two researchers were involved in coding the data. ‘Check-coding,’ a technique where the researchers separately code the same data and subsequently come together to compare codes, was employed to enhance reliability (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994). A working reliability score was then calculated by dividing the total number of coding agreements (adjudged by content rather than working labels given to codes) by the total number of agreements plus disagreements. This process was performed intermittently until reliability reached a satisfactory level. Intercoder agreement was considered reliable when it reached 90%, as recommended by Miles and Huberman (Reference Miles and Huberman1994).

Results and Discussion

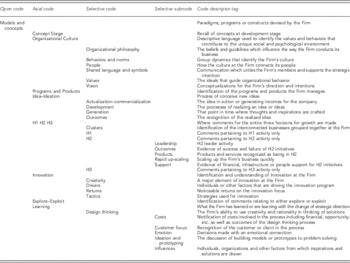

We present the data by first identifying and describing the four open codes and their general contents. Table 1 presents a summary of the open and axial codes exported from NVivo’s file structure.

Table 1 Open and axial codes imported from NVivo

The first open code labeled Models and Concepts, captures the paradigms, programs or constructs employed by the Firm. These models and concepts represent shared mental lenses depicting key assumptions about the Firm’s internal engagement and ways of perceiving the outside world. In addition to views about the culture and values of a professional services firm, respondents expressed the need to shift away from traditional organizing forms, and work with models that embrace the tension associated with the explore–exploit imperative. As a consulting partner and member of the Firm’s Innovation Board observed, ‘Is there sufficient uncertainty around it? If there’s not enough uncertainty, it probably should be done again, another model.’

In turn, eight axial codes conceptualized Models and Concepts: (1) Concept Stage; (2) Organizational Culture; (3) Programs and Products; (4) Idea–Ideation; (5) H1, H2, H3; (6) Innovation; (7) Explore–Exploit; and (8) Learning. For each axial code, the selective, and selective subnodes underpinning their categorization appear as an exemplar in Table 2. One axial code requiring further comment is ‘H1, H2, H3.’ This refers to the three horizon model where the first horizon (H1) involves minor, incremental innovations designed to bolster current operations; horizon two (H2) innovations focus on extending competencies into new markets or commercializing nascent, high potential new products; and horizon three (H3) deals with innovations capable of radically changing the composition of a firm’s product/market position. However, as the CEO observed in framing why the Firm was forced to experiment with untested organizing forms, conceptual models do not easily translate into the real world: ‘… it was supposed to be the perfect model of H3 into H2 into H1; we very quickly saw that this thing doesn’t really work in H2. Let’s put it aside and run it very, very separately.’

Table 2 Example open code – models and concepts

The second open code, labeled Actions, was the largest and represented the translation of the Firm’s ‘models and concepts’ to its operational, organizing forms focus from 2003 until 2013. One senior partner commented: ‘… what was recognised 3 years ago was that there was a problem that was unanswered and a willingness to invest and explore that.’ Actions comprises two axial codes: (1) Performance and Delivery, and (2) Marketing. Performance and Delivery contains 10 selective codes and eight selective subnodes, mainly reflecting the Firm’s perceived and actual success in delivering on its new fluid structures. According to the Firm’s Innovation Director, ‘… we’ve got the strategy, we’ve said we’re going to do what we’re going to do at a high level, we’re now going to take it down another level in terms of the initiatives and building project plans.’ Marketing contains 13 selective codes and 10 selective subnodes, principally dealing with the firm’s aggressive brand position, operational processes, and leadership underpinning the choice of organizing forms, or what the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) described as ‘… big plays that we thought could make a difference to our growth and branding.’ That is: ‘Being known as the most innovative firm is really important.’ (Senior Partner)

The third open code, labeled Interactions, concerns the firm’s approach to engagement with internal and external stakeholders. Five axial codes comprise Interactions: (1) Client Interface; (2) Executive Level; (3) External Interface; (4) Staff Level; and (5) Tension. Throughout all forms of engagement with internal and external individuals and groups, the tension arising from the dual need for explore and exploit activities proved a common element in respondents’ comments. With the appetite for change from the leadership came the mandate to experiment and challenge conservative ways of organizing, including the widely held assumption that new structures should at least be harmonious and permanent, rather than deliberately contradictory and transient. Allied to this desire for change was a certainty that if the firm could find the right organizing drivers for both explore and exploit, they would reap the rewards. According to the CEO, ‘… we have to change, we are going to gain ground like we’ve never seen before if we now act out the agility that we have been training for since 2003.’ However, with new initiatives and expectations also came pain. For one senior partner at the coalface of a small, new start-up venture project, only part of the equation seemed successful. She commented, ‘Well we are failing cheaply, like it’s costing nothing for me to spend all my extra time … I’m slowly getting burnt out.’

The fourth open code was References, capturing sources of influence on the Firm’s path from 2003. It was clear that importing the explore–exploit and horizons concepts had caused a significant impact, infiltrating the thinking and everyday language of the respondents, including the Chief Strategy Officer (CSO), Asia-Pacific: ‘The three horizon model … which is saying in H1 that’s where exploit happens and in H3 that’s where explore happens and you have to have a healthy pipeline.’

References included three axial codes: (1) Commercialese; (2) Management Thinkers; and (3) Success and Failed Organizations. The first axial code referenced attempts to convert theory into practice. One senior executive noted: ‘We started to take some of the lessons again from the latest work … which is basically saying, you know, think big but bet small and the only way it can get together is to be disruptive, and that is what you should do in H3 and it should not cost a lot of money.’ The Firm’s leadership had spent considerable time and money traveling to prominent management schools to acquire the latest tools and thinking: ‘I then took the executive all to Harvard a year later to a course on managing organizational change and renewal, which is really about the theory that you can take innovation into an existing company.’ (CEO) At the same time, the CEO and his executive team remained vigilant about lessons from both failures and successes: ‘Kodak is my great inspiration for not wanting to be like them.’

An explore–exploit model

The model reproduced in Figure 1 conceptualizes three thematic results that seek to explain the unique organizing forms model that the Firm evolved to secure both explore and exploit outcomes. The first involves aggressive initiatives in both explore and exploit spaces simultaneously. The second involves the implementation of horizon two projects designed to fast track the scaling-up process from innovation to commercialization. The final theme involves the creation of a new business unit operated as a start-up, and its subsequent return to the mainstream business, after which the process was repeated.

Figure 1 Explore–exploit model

The model explains the Firm’s response to its explore–exploit challenge. In Figure 1, the horizontal lines at the top and bottom of the page specify the Firm’s contextual position, the former through its internal modes of thinking and operation, and the latter through the external references influencing judgment and action. Internally, the company operationalized its philosophy through a bold strategic objective: 30% of revenue will come from new or substantially different service offerings every 2 years. As a billion dollar company, this means generating more than $300 million of new business services every 2 years. The CSO reinforced the importance of the strategy: ‘It replaces the stuff that becomes redundant and commoditized that we need to exit, but it also creates growth opportunities which our people need like humans need oxygen.’ Simultaneously, the Firm distanced itself from the natural inclination to prescribe and inform, ‘… we were talking about what new services means … how it creates opportunities for growth for individuals, how many people actually make partners out of that, how this is cool to be in the new space.’

External influences also shaped the burgeoning entrepreneurial approach. While benchmarks provided by competitors and lessons from other successful companies were studied intensely, the Firm also imported a ‘design-thinking’ method as a tool toward a renewed mindset for approaching clients, products and the new organizing forms that were needed. According to the Innovation Director, ‘Design thinking is about getting people to think differently, really getting them to look at things and change the way they look at things today.’ Even the once skeptical CFO observed that, ‘Things we’re doing around design thinking now are starting to resonate.’

Theme 1: Fluid dualities and innovation/commercial algorithms

In recognizing the problems associated with oscillating attention and resources between explore and exploit, the Firm crafted a new organizing framework where the two modes of structuring would be pursued. But, rather than a balance, high levels of both were sought at the same time, which also led to a more fluid approach to organizing than they were used to. Whereas in the past new structures were put in place on the assumption that further change would be in the distant future, the Firm now began with the principle that change to structures would be constant and essential in order to capitalize on the tension between the distinctive organizing forms associated with control and flexibility. According to the CSO, ‘… the exploit process said you put a business case in place with certain workflow, this is what you do, this is the approvals you get, get it signed over 10 places.’ Conversely, in the explore process ‘… you come up with a good idea, you get $10,000 to go and play with, no questions asked.’

In the exploit sphere, illustrated on the right of Figure 1, the Firm divided its operational business units into 60 highly granularized, specific, measureable and accountable ‘clusters.’ Performance in each cluster was assessed with forensic vigor: ‘You just focus on what we call operational excellence measures’. (CFO) The result was the division of the clusters into five performance bands – fix, enhance, optimize, accelerate and dominate – designed to encourage the elevation of lesser performing groups at the same time as revealing where to invest and grow those of the greatest potential. As one senior partner indicated, for those underperforming clusters, ‘We are not interested in your growth, your client penetration, because we think that for every dollar, for every new client you get, we lose a dollar, so fix your basic operating model.’ This microexploitation represents the firm’s commercial algorithm.

On the explore side of the ledger, depicted on the left in Figure 1, the Firm invested heavily in organizing forms dedicated to driving innovation. As early as 2004, an internal innovation program was established, designed to provide employees with a forum to share and generate ideas. The program’s governance model comprised an appointed executive under which an Innovation Council was established to assess ideas, solicited from all members of the Firm via the cloud-based Innovation Academy tool, and typically arranged under a general theme such as social media, mobile applications or gaming. Combined with their small group-based Innovation Café process for collective brainstorming, incorporating contributors from diverse backgrounds, expertise and positions, the pool of new ideas was next subjected to an online game mechanic for rating. Using an online Innovation Idea Capture tool, rationed votes helped to reduce the sweeping range of ideas to a handful. The Council looked for game changers, including ideas that could be taken to market to generate revenue over the next 12 months, or improve the company’s agility with streamlined processes: ‘… the effect of the process is to create, generate ideas, submit those ideas in a transparent way, through our innovation idea capture tool, and then people promote it through our internal social media networks and through their mates and try and get them to vote for it, comment on it, collaborate around it.’ (Chair, Innovation Council)

The Council reviewed ideas every two weeks and allocated microfunding to the most promising on the basis of voting and alignment with existing offerings. The microfunding model utilized a venture capital philosophy and structure. Once an idea was selected, its originator was allocated AUD$10,000 on the basis of a one-page pitch: ‘Put the idea in, we’ll review it within two weeks, if we like it we’ll give you a micro-fund of $10,000 which gives enough oxygen to the idea to get it going, … and if there’s an appetite for it, expand it.’ The microfund worked on the basis of a ‘pool of time’ concept allowing for all innovation projects to run and conclude in pulses as structures including diverse cross-sections of expertise from across the firm.

As a professional services operation, the Firm uses time as a currency. It therefore needed a mechanism to allow its members to work on innovative ideas in the same way that they would with client ideas. The answer involved creating a pool of time wherein a dollar value was allocated against every project. And, every project was considered a fluid cross-functional structure. As a result, project champions could work on their ideas up to the value of AUD$10,000 without compromising their service line revenues, as the project was treated in the same manner as a client billing process. As a method of cyclical regulation when ideas flow quickly or slowly, the Council could modify the realization percentage on the pool of time. If new ideas were overflowing, for example, realization on the time could be decreased so that project champions worked for less than 100% of full billing rates. Innovators could receive up to AUD$50,000 in bootstrapping finance provided their 6-weekly reports demonstrated proof of concept, client interest and ultimately a commercial case. Project structures were broken into discrete chunks or ‘staged gates,’ where exits could be taken discontinuing, divesting, spinning in or commercializing the new product or service. A key assumption was that all innovation-driven organizing projects would start, peak and end as fast as possible.

Although simple, the pool of time model protected partners’ performance measures, thereby encouraging quick forays into innovation, as its costs did not come in either implementation time or in preparing lengthy business cases. It also liberated any individual willing to mobilize his or her ideas into a reality: ‘But the beauty of this is you give a person $10,000, they spend their weekends on this. You get $50,000 worth of input for that investment. That was the best return on investment we ever got because we tapped into discretionary effort, and people didn’t feel abused. They loved it, and that now is core to the way that we look at our innovation program.’ (CSO)

Theme 2: Horizon 2 projects as scalable organizing forms

The center channel of Figure 1 depicts the ‘productive tension’ between explore and exploit. Within this channel are horizon two (H2) projects, designed initially as commercialization pathways to up-scale high potential innovations as fast as possible and return them to the business clusters. As such, they rely on being transient organizing forms for success: ‘We define success in Horizon 2 as the speed with which we can create a scaled business to go back into the core … so they’re fairly attractive, got good scale and there’s some uncertainty, and that perhaps means there’s more than one service line involved.’ (H2 project leader and partner) Under this original conception, clusters were considered inappropriate hosts for H2 products, too conservative, static and time-poor to invest in nascent ideas. Equally, the innovation program was too informal and unstructured to accommodate the tight market expectations of clients expecting a rigorous and tested new product. H2 requirements ‘and the scale and the complexity, it’s got to be more about future trend spotting than coming out of incremental strategic insights … that’s not to say that they wouldn’t have input from the innovation program but I think it’s a little less likely.’ (H2 project leader and partner) As a result, the Firm needed an organizing form that offered the solidity and confidence of a more formal structure without relinquishing the fluidity and agility of an ad hoc structure.

After several years of difficult experimentation – ‘… you know it’s messy and it’s ugly and it’s frankly stressful’ – the H2 projects began to evolve naturally into two streams, mainly because an independent program was less influential across the firm than semi-independent projects receiving support from a central group but connected more directly to an innovation or a commercial channel. One set of H2 projects reflected a high risk and return orientation, having grown as a radical new innovation seeking a commercial home. Another set aligned more directly with a sponsoring cluster and sought to infuse a new product or market orientation around an already successful initiative. According to the CEO, ‘… it’ll be the third year in a row that H2 has not got the support I believe it deserves to get. We’re going to persist …’ The overarching problem was that the projects required partner champions to shift focus from their profitable cluster businesses (‘I gave up a 4.5 million dollar ledger’). As a result, ‘the biggest challenge is that you have a very small group of people and skill wise you’re loading … there’s high expectations loading up onto them.’ (H2 leader and partner).

The idealized intention of a series of middle-ground H2 projects encountered difficulty, belonging to neither camp, and supported by no one other than a small, centralized support unit. But two developments added traction to the ongoing H2 projects. First, those effectively up-scaling existing products in the form of a significant product/market expansion began to align with a parent cluster, keen to incorporate the addition as soon as possible, fueled by the powerful and ever-present reminder that 30% of their business must be replaced every second year. Second, the more radical innovations, too far from commercial success for a cluster to engage with, and typically involving high levels of technical specialization or digital knowledge, began to connect with a relatively new, independent start-up business unit being operated by a brazen internal entrepreneur, conferred with unprecedented autonomy and a propensity to make things happen fast. The cluster leaders had found a way to meet their confronting new targets for growth, while the innovators had found a vehicle to progress their ideas without falling victim to over-analysis and measurement.

Theme 3: Fluid organizing forms for optimizing duality tension

Figure 1 presents ‘fluid corporate entrepreneurship’ at the center of the tension between explore and exploit. This third theme reflects the development of TechFirm. Unlike a typical corporate spin-out, TechFirm remained within the company but, at the same time, operated like an entrepreneurial start-up.

TechFirm was formed in 2009, ostensibly to create digitally driven professional services. The internal start-up assumed a platform emphasizing technology-based services and stand-alone products, but its real differentiation was an entrepreneurial method emphasizing rapid prototyping, proof of concept, fast and cheap failure, and agile systems. At the helm was a partner described by the CSO as someone specializing in ‘pushing the boundaries.’ TechFirm’s CEO reveled in the prospects of entrepreneurial empowerment, knowing from his own successful business ventures that ‘Innovators don’t necessarily want rewards, they want to see their idea executed. You give them a bit of oxygen, you give them a bit of capability, you help them get something out the door, they’ll put in.’

TechFirm aimed to be a ‘game changer,’ challenging the traditional professional services firm model. Instead of high margins and few clients with high touch, regular face-to-face contact, the TechFirm model worked on low touch, low resolution, infrequent face-to-face contact, self-service, high volume of transactions and numerous clients at low margins. Under the revised model, generating new ideas was subservient to their transformation into rapid execution. The small team comprised a mix of young entrepreneurs and more experienced members recruited from traditional clusters.

In 2012, TechFirm blended into the exploit world with the Firm’s Management Consulting Practice, aiming to consolidate a suite of integrated digital products and services. For example, both product and market opportunities expanded radically when TechFirm’s new tools were wielded by consulting expertise to share services and build offerings in partnership with other parts of the Firm. The organizing model had come full circle: the Firm spun out TechFirm until it had secured its mandate and then spun it back in. Innovation needed freedom until it became sustainable but then needed control to generate scope and efficiency. The Firm’s Managing Partner of Consulting added: ‘We’ve brought out what we had as our online practice which was our consigned practice that takes external digital offerings to the market, web design development, e-commerce. And we’ve brought them both together now.’ As a result, a world of new services was opened by the digital bridge: ‘… we’ve got a human capital practice over here that consults on leadership, let’s bring those two together and digitize and differentiate your leadership offering that you take to market.’ With the Firm’s opportunities for contained but disruptive innovation curtailed by the absorption of TechFirm into main operations, the former CEO of TechFirm was assigned to repeat the process in spearheading a new innovation venture.

Implications for Theory

Interpretive, grounded methods are conventionally criticized for their lack of generalizability across populations. Rather, case studies such as this generalize only to theoretical propositions, although this can be subject to debate too. The dual pioneers of grounded theory, Glaser and Strauss, part ways from each other on several nuances including the appropriate treatment of results. Glaser (Reference Glaser1992) favors a more confined interpretation, while Strauss and Corbin (Reference Strauss1990) advocate for the transfer of interpretations from one context to another. Others remain undecided or unclear (e.g., see the reviews by Hammersley, Reference Hammersley1989; Annells, Reference Annells1996). Our way of overcoming this dilemma was to focus on generalizing the phenomena underlying the behaviors observed within the Firm, rather than attempting a wholesale transfer (De Vault, Reference De Vault1995), an approach also consistent with Whiteley (Reference Whiteley2004).

Harnessing the explore–exploit tension to create dual or ambidextrous forms of organizing has long been viewed as key to the successful management of continuity and change. We argue that our results suggest this cannot be achieved through some bland compromise, but rather by striving to excel at both exploration and exploitation. Yet, to date, no comprehensive theory has emerged to guide organizations toward ‘true’ ambidexterity, where an organization is committed to pursuing both organizing forms simultaneously, and with the same determination. Instead various contingent forms of ambidexterity have been advocated, such as temporal switching between explore and exploit, either emphasizing differentiation or integration (Eisenhardt & Brown, Reference Eisenhardt and Brown1998; Rindova & Kotha, Reference Rindova and Kotha2001). This form of ‘ambidextrous sequencing,’ switching on and off between an exploitative framework (premised by efficiency, stability and control) to an explorative framework (invoking innovation, adaptability and risk taking), represents a significant challenge for leaders and managers trapped between shifting priorities. We propose that a dual organizing forms architecture may provide the means for enabling and encouraging organizations to explore and exploit with equal success. In this case, we suggest that this dual capability underpins an organization’s proficiency to operate under, and sustain the dualistic organizing tension, that delivers both explore and exploit outcomes. Our contribution lies in highlighting how a dual capability will advance a revised process view of the exploration–exploitation process.

The enduring argument is that sustainable long-term organizational futures demand simultaneous exploration and exploitation that are pursued with equal vigor and dexterity. In fact, the simultaneous pursuit of exploration – invoking innovation and change, and exploitation – premised by stability and control, is viewed as undeniably critical to organizational success and survival, in which tension and discontinuity are accepted as natural, irreducible elements in managing ambidexterity. The plea for organizations is to put in place systems that can cope with ambiguity, ambivalence and contradiction. This suggests that organizations must learn to manage the dualistic tensions that underpin exploration (change) and exploitation (continuity). Examples include nurturing innovation alongside rigorous financial and operational systems; fostering empowerment through strong and supportive leadership; considering the impact of economic realities on social goals; and balancing formalized, central controls and policies with decentralized decision-making that would support more flexible forms of organizing. Yet, as we have uncovered, the simultaneous achievement of the overarching exploration–exploitation duality can prove elusive. The reality is that organizations ‘are not generally equipped to cope with fragmentation and high ambiguity,’ and the real challenge remains in encouraging organizational leaders to accept ambiguity as a ‘valued asset’ (Seo, Putnam, & Bartunek, Reference Seo, Putnam and Bartunek2004: 162).

Where discussion around explore–exploit tends not to get beyond ‘dynamic oscillation’ or modular organizing versions, a dual model attempts to create a new construct where the two extremes merge. Instead of saying what a company needs to do, the Firm’s leadership instead focused on what it needed to build in order to grow and develop, bringing together both structural and contextual considerations. As a consequence, rather than just assuming that explore and exploit outcomes are both needed, attention must shift to the development and sustenance of exploration and exploitation. Organizations now must learn something completely new, so the question turns to ‘how’ the new capability can be developed because ambidexterity entails doing both at once, not at different times. As we suggest, duality theory offers a potential explanatory framework for understanding and managing the tensions that arise in building a capacity for simultaneous, dynamic, related exploration and exploitation. A duality theory framework provides a conceptualization of change incorporating complexity and contradiction, without the implicit emphasis on removing, micromanaging, ignoring, or denying tension or contradictions.

As this case results highlight, the key to pursuing exploration and exploitation with equal skill and fervor lies with addressing the competing yet ultimately complementary contradictions as natural, irreducible elements of an organization’s capabilities. Dual capabilities operate across explore and exploit domains and broker linkages to share, absorb and translate into action the accumulated knowledge, skills, expertise and experience residing in both. As Tushman et al. found (Reference Tushman, Smith, Chapman Wood, Westerman and O’Reilly2010: 1336), positive performance outcomes depended upon ambidextrous designs that encapsulated heterogeneity through multiple integrated architectures that were ‘highly differentiated and inconsistent.’ This in turn points to the challenges we discussed and explained for the leadership team, not only in working with uncertainty and ambiguity and being comfortable with taking risks, but also in invoking and maintaining linkages across exploit–explore domains, and incorporating appropriate performance measures and benchmarks for nascent explore initiatives. The aim of building productive capability is not to resolve but to engage with the tension between these dual explore–exploit elements.

Reframing the explore–exploit tension: Fluid organizing forms

The Firm’s model of three organizing forms offers a workable response to the explore–exploit tension. However, rather than an opportunistic, dynamic oscillation between innovation and efficiency, the model reveals how the two can be practiced simultaneously through a form of ‘fluid’ structures. One initiative saw the creation – and most importantly liberation and return – of TechFirm. As a genuine start-up, the business unit broke all the rules, bound not by financial targets, but rather by a commitment to experimentation, fast and cheap failure, and finding linkages across the traditional business clusters. TechFirm’s CEO operated as a boundary spanner facilitating the flow of information between different groups and enabling ‘communication and understanding to take place across … knowledge domains’ (Taylor & Helfat, Reference Taylor and Helfat2009: 721). In his own words, ‘amazing things happen at intersections.’ The consolidation of TechFirm into the Firm’s consulting arm also highlights the centrality of driving the innovation culture deeper into the exploit landscape. The case reinforces the theoretical position (Leana & Barry, Reference Leana and Barry2000; Luscher & Lewis, Reference Luscher and Lewis2008; Davis, Eisenhardt, & Bingham, Reference Davis, Eisenhardt and Bingham2009) that one way to take advantage of the explore–exploit tension involves the use of heterogeneous, modular groups and units capable of working in the gray area, where the normal rules and expectations become more elastic, and novel propositions can be tested in the real world quickly at a low cost and risk. However, our model suggests that the tension becomes most productive when the groups move back into the fold.

A fluid focus: From explore–exploit tension to organizing forms action

Theorists such as Baghai, Everingham, and White (Reference Baghai, Everingham and White2000), and Moore (Reference Moore2007) have warned that attempting to optimize exploitation and exploration does not work. Balancing the two or trying to opportunistically shift resources between them paradoxically tends to leave investment in innovation for plentiful times when it is least needed. Along with the resource allocation issue, leaders and managers need to continually switch metrics and priorities around time horizons, performance and investment outcomes. According to dualities theory, the key revolves around maintaining a deliberate disequilibrium where everyone accepts uncertainty, tension, ambiguity and the real possibility of deleterious performance ratings in order to ensure that the next stage of the company’s life cycle will be successful. In the real, cut and thrust world of daily business, however, the duality mindset remains difficult to enact. The Firm’s response held consistent with a dualities approach, but as reported as a first theme, the key unit of thinking shifted to a fluid organizing mindset.

Where researchers like Tushman, Lakhani, and Lifshitz-Assaf (Reference Tushman, Lakhani and Lifshitz-Assaf2012) proposed that organizations create numerous and blurred boundary options, the Firm’s boundaries solidified through the use of fluid organizing forms. Clusters deliver the daily bread but seized virtually ‘free’ ready-made new products, mindful that their performances were being measured not just by quarterly profits, but also by a steady turnover of revenue sources. A solid foundation of stability serves as ‘both an outcome and medium of change’ (Farjoun, Reference Farjoun2010: 203). Our data indicate that management support, work discretion, organizational boundaries, rewards and reinforcements, and time availability were all fluid and conditional upon the leader and his or her project. That is, they were temporarily molded to the indigenous needs of the project at hand. The Firm’s H2 project initiatives were more successful when they avoided prescriptive, formulaic impositions and simply worked hard to support those that were working. A benefit of the dualities mindset enacted with these organizing forms is the disinclination to predict the unpredictable and just get on with testing the market.

Theory in Context

The Firm has been in business in some form since the late 19th century. It grew and prospered until the late 1980s when it became the victim of its own success, having become large but inert. It lacked the drive, willingness and flexibility to adapt and respond to a changing environment. The focus was on ensuring efficiency and stability, driven by conservative organizing principles around regulatory requirements and accountabilities. By the 1990s, the company had lost focus and direction, fueled by the arrival and departure of 10 CEOs in the space of just 8 years. By 2003, as the newly appointed CEO discovered, the company was hemorrhaging clients, staff and millions of dollars of revenue. As he described it, the place ‘was just a mess, it was not a happy place, and it was not a happy commercial place,’ lacking in motivation and low in morale and collective esteem. However, the incoming CEO and his new deputy, the firm’s CSO, saw the widespread turmoil and discontent as an opportunity to construct a new vision and direction. Their ambition was to encourage a more innovative, entrepreneurial business model to enhance the traditional side of their services that relied upon defending existing routines for business success. The leadership sought to encourage opportunistic responsiveness through exploration and experimentation while simultaneously maintaining efficiency and stability through the exploitation of existing resources. Initially, however, the senior leadership team struggled to give their message a clear voice. It was not until they explicitly transformed their message and consistently sought to emphasize both explore and exploit capabilities as integral to the organization’s continued success that those middle managers and partners responsible for implementing the new vision began to understand what changes in behaviors and practices were required to build such capabilities.

But how feasible is it, and what costs must be borne, in aggressively pursuing this proposed balance of exploitation and exploration? How, for example, do organizational leaders accommodate the structural and managerial tensions that accompany a commitment to innovation through both exploitation (‘tight’ structures, control, continuity, stability, conventional reporting and performance measures) and exploration (‘loose’ structures, flexible, responsive, experimental, evolving)? Simply put, how can organization leaders deal with such contradictory and complex forces? After all, according to previous studies, high levels of exploration and exploitation at the same time means dealing with completely different structures in a business.

We suggest that the Firm’s success lies with their approach to dealing with the explore–exploit tension. Instead of seeking to delimit it, they sought its escalation into a ‘productive tension,’ sufficiently powerful to impel individuals to exercise their entrepreneurial inclinations. According to the literature, a core challenge in reconciling the tension inherent in managing innovation and commercialization structures pivots around a misalignment between the organization and the individual. For example, there has been an overreliance on developing the organizational mechanisms needed to enable explore–exploit with little appreciation or understanding for the importance of individual performance (Raisch et al., Reference Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst and Tushman2009). Individuals tend to find it difficult to excel at both exploitation and exploration. Individual capability necessitates managing contradictions and conflicting goals, working with uncertainty and ambiguity, being comfortable taking risks, and performing diverse, fluidly changing roles.

Fluid structuring for explore and exploit

In framing their challenge, the Firm’s leadership faced the twin and often contra-indicated necessities of a controlled, commercial yield and radical product innovation. Between what they described as an ‘explore–exploit’ tension, the Firm responded by creating novel structures and initiatives characterized by three organizing forms described by the grounded theory presented in Figure 1, and outlined earlier as themes. The first tier combined a precisely executed cluster business model dedicated to surgical measurement, control, efficiency and incremental improvement with an innovation program committed to rapid prototyping and concept proofs in the market instead of lengthy commercialization plans, plus a design-oriented, user-based mode of thinking about client experiences instead of off-the-shelf service solutions. The second tier focused on discrete mid-horizon (H2) commercialization projects seeking either to inject modified products into existing clusters as rapidly as possible, or work toward the development of radical, ‘game-changing innovations.’ The third tier involved a pseudo spin-out, spin-in model of ongoing start-ups designed to operate freely as entrepreneurial entities that bring their newfound products and culture into the main operations. These three tiers offer some clues for similarly positioned knowledge-intensive business services toward the management of the explore–exploit ‘innovation’ tension.

Driving innovation and control with duality tension

Instead of relying upon change to the engrained performance mindsets of cluster partner leaders, the Firm’s executive leadership treated the entire business as an organizing sandpit. They constructed an innovation program open to all staff, which in turn fed incremental innovations into the clusters while releasing the potential of higher risk, disruptive ideas to connect with a new business unit that could deal with them. At the same time, the business unit clusters became further ‘granularized,’ although paradoxically the clusters loosened their stranglehold on the past and opened the door to new possibilities, driven by a newfound cohort of intrapreneurs keen to exercise some entrepreneurial thinking without cash-based cluster investment and without compromising day-to-day measures.

Paradox of location: Exploring radical innovation/exploiting existing initiative enhancement

As a second tier of fluid organizing forms, the Firm introduced horizon two projects designed to identify high potential ideas and rapidly accelerate their commercialization. Supported by a small central unit, H2 project leaders linked in with parent clusters or with TechFirm. The result was a series of new product/service prototypes, tested in the market and converging upon a deliverable commercial offering.

Conclusions

This case suggests that part of the Firm’s success emerged from their fluid organizing forms approach to dealing with the explore–exploit tension. Instead of seeking to delimit it, they sought its escalation into a productive tension, sufficiently powerful to impel individuals to innovate, but sufficiently contained to be captured at an organizational level. According to the literature, a core challenge in reconciling the tension inherent in managing innovation and commercialization structures pivots around a misalignment between the organization and the individual. For example, there has been an overreliance on developing the organizational mechanisms needed to enable dualities with little appreciation or understanding for the importance of individual fluidity (Raisch et al., Reference Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst and Tushman2009). Individuals tend to find it difficult to excel at both exploitation and exploration; they must manage contradictions and conflicting goals, work with uncertainty and ambiguity, be comfortable taking risks, and perform diverse, swiftly changing roles. We find in the Firm’s case a series of organizing forms in which individuals can be innovative and stable.

We suggest that the use of a naturalistic method employing grounded research procedures has proven productive in allowing the details of this case to be exposed in a manner consistent with the experiences and interpretations of its respondents. Although we cannot generalize sweepingly on the basis of compelling statistical significance, the data do offer possible indicators for other knowledge-intensive business services to explore. While acknowledging the contextual inextricability of any case, we note that it provides insightful themes concerning the nature of real-world corporate organizing, as experienced in the minutiae of a shared organizational reality.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is an original work that has not been submitted to nor published anywhere else. All the authors have read and approved the paper and have met the criteria for authorship as set out under Authorship in JMO: Instructions for Contributors. A key contribution of this paper is its use of a grounded research interpretive design to study a professional service firm’s decade-long organizing forms response to the need for groundbreaking innovation while maintaining existing operational performance, and thereby respond to the research question: How does a large firm deliver on efficiency and control at the same time as flexibility and innovation through its organizing forms? The paper seeks to align with the scope and aims of the Journal by offering theoretical and practical implications that emanate from the case study findings While acknowledging the contextual inextricability of any case, it provides insightful themes concerning the nature of real-world corporate organizing that will be of benefit to both scholars and practitioners.

Financial Support

This paper received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.