Introduction

For most Western countries, knowledge work makes up an increasing part of their economic activity (Engelbrecht, Reference Engelbrecht2000; Kitay & Wright, Reference Kitay and Wright2003; Wei, Reference Wei2004; Cannizzo & Osbaldiston, Reference Cannizzo and Osbaldiston2016; Hays, 2016; Eurostat, 2018), not least what is known as knowledge-intensive business services (Miles, Reference Miles2005). Knowledge workers are typically highly educated, and the input and output of their work are concerned mainly with the handling and production of information (Alvesson, Reference Alvesson2004). Knowledge-intensive business service relies highly on worker creativity, on the personal, professional judgment of the worker, and on close interaction with customers (Løwendahl, Revang, & Fosstenløkken, Reference Løwendahl, Revang and Fosstenløkken2001). All these factors contribute to the fact that knowledge workers are expected to self-lead to a high degree (Drucker, Reference Drucker1999).

A prominent challenge for knowledge workers is to manage the underdesign of their work. How and even what to work on often is not clearly specified, but is considered part of the job to define (Drucker, Reference Drucker1999; Alvesson, Reference Alvesson2001; Hatchuel, Reference Hatchuel2002; Davenport, Reference Davenport2005). Knowledge work is nonroutine: It may not be clear exactly what a problem is or what your task is, what you can expect or demand from others, or what they can demand from you. The responsibility for planning, prioritizing, coordinating, and executing work is placed to a large degree on the individual knowledge worker (Grant, Fried, & Juillerat, Reference Grant, Fried and Juillerat2010: 104; Allvin, Mellner, Movitz, & Aronsson, Reference Allvin, Mellner, Movitz and Aronsson2013). Outcomes in service business are more directly the result of employee behaviors than they are in industrial settings where technology and work design play a larger role (Edgar, Gray, Browning, & Dwyer, Reference Edgar, Gray, Browning and Dwyer2014). Although the knowledge worker is the most valuable asset of a knowledge-intensive business services firm, little empirical research has been carried out that examines the self-leadership of knowledge workers.

Moreover, mental health problems due to stress at work, including worker burnout, are growing and expensive issues in Australia (Safe Work Australia, 2015), New Zealand (Baehler & Bryson, Reference Baehler and Bryson2009), UK (Health & Safety Executive, 2017), United States (American Psychological Association, 2012), and Scandinavia (Borg, Andersen Nexø, Kolte, & Friis Andersen, Reference Borg, Andersen Nexø, Kolte and Friis Andersen2010; Försäkringskassan, 2017). Although previously thought to be the case, knowledge workers’ great autonomy does not exempt them from the risks of work intensification; in fact, such autonomy may even contribute to it (Ipsen & Jensen, Reference Ipsen and Jensen2010; Michel, Reference Michel2014; Pérez-Zapata, Pascual, Álvarez-Hernández, & Collado, Reference Pérez-Zapata, Pascual, Álvarez-Hernández and Collado2016). The largest contributing factor to work stress is how work is organized in terms of pace, intensity, quality of communications and social relations, employment security, and more (Schnall, Dobson, Rosskam, & Elling, Reference Schnall, Dobson, Rosskam and Elling2018). Moreover, while an employer is responsible for the organization of work traditionally and legally, when it comes to knowledge work in practice, it is the workers themselves who are responsible (Ipsen & Jensen, Reference Ipsen and Jensen2010). This further highlights the need for empirical research that examines the self-leadership of knowledge workers, especially as it relates to work intensity and stress.

Knowledge workers are highly educated and report high intrinsic motivation in their jobs (Joo & Lim, Reference Joo and Lim2009; Ipsen & Jensen, Reference Ipsen and Jensen2010). Owing to the complexity of the work, it requires high amounts of controlled attentional effort (Kaplan & Berman, Reference Kaplan and Berman2010; Müller & Niessen, Reference Müller and Niessen2018), which is a depletable resource (Vohs, Baumeister, Schmeichel, Twenge, Nelson, & Tice, Reference Vohs, Baumeister, Schmeichel, Twenge, Nelson and Tice2008). From a knowledge worker perspective then, conventional self-leadership theory strategies (Manz, Reference Manz1986; Stewart, Courtright, & Manz, Reference Stewart, Courtright and Manz2011) have two main weaknesses: (a) they focus on enhancing intrinsic motivation, a motivation expected to already exist for knowledge workers and which can even exacerbate some problems (Muhr, Pedersen, & Alvesson, Reference Muhr, Pedersen and Alvesson2012; Pérez-Zapata et al., Reference Pérez-Zapata, Pascual, Álvarez-Hernández and Collado2016); and (b) they focus on the self rather than on surrounding factors, which demands additional attentional effort. Given these limitations of self-leadership theory in this context, we see an opportunity to revisit knowledge workers’ self-leadership. Thus, the aim of this study is to investigate the link between self-leadership strategies and work intensity in knowledge workers, using management consultants as an example.

The paper is structured as follows: The theoretical background is presented, including the concepts of knowledge work, self-leadership and ego depletion; the study sample and method are described; empirical results and analysis are presented, followed by a synthesizing discussion, implications, limitations of the study, suggestions for future research, and conclusions.

Theoretical background

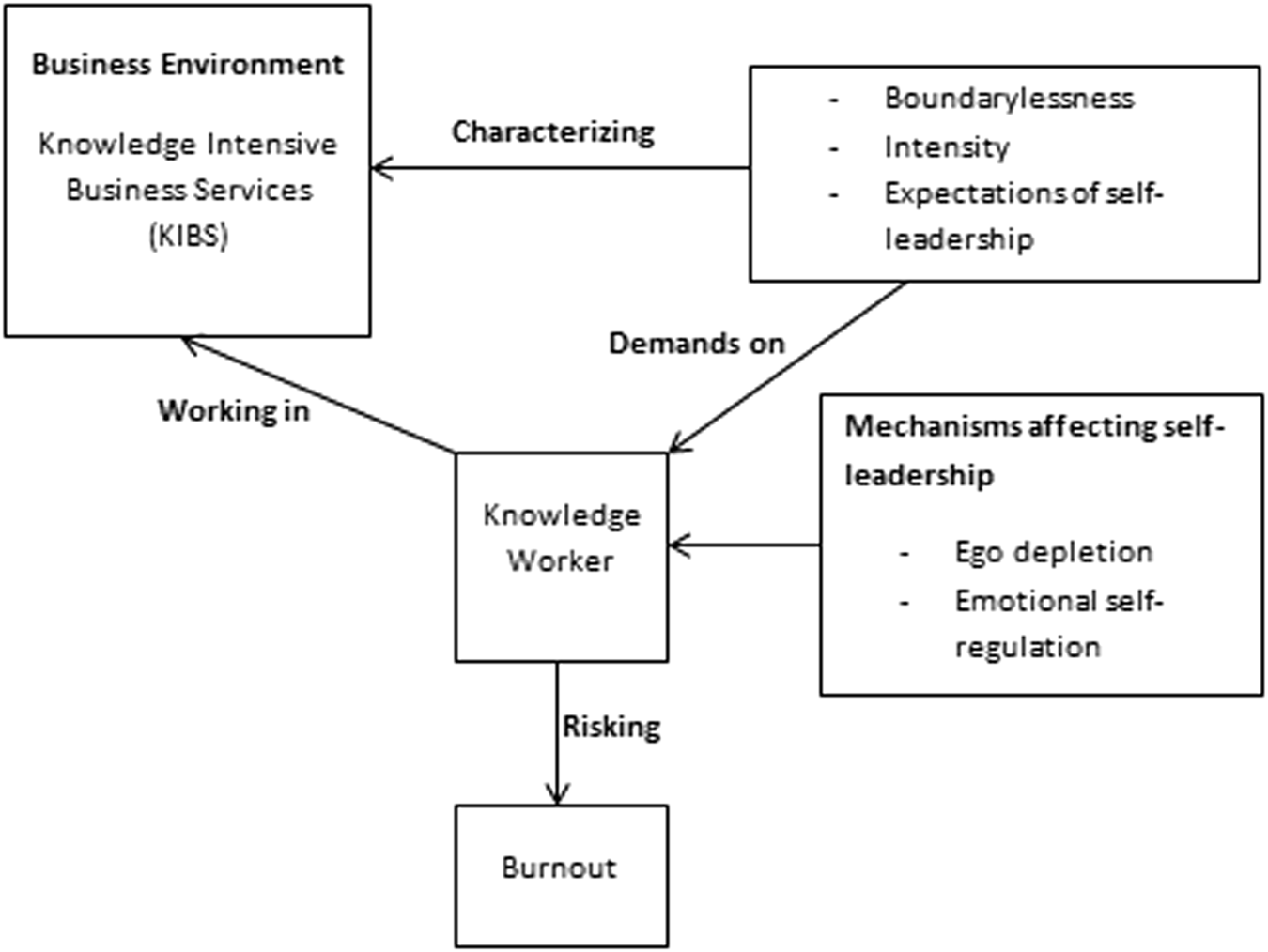

Here we explore the theoretical concepts used in the study. For a visual overview of the general relationships of the concepts, see Figure 1.

Figure 1 Relational map of theoretical concepts

Knowledge work and knowledge workers

A common denominator for knowledge-intensive firms is that such organizations predominantly employ highly educated people and that both the work and the results are concerned mainly with the handling of information (Alvesson, Reference Alvesson2004). Archetypical examples of workers in knowledge-intensive firms include software developers and management consultants (Starbuck, Reference Starbuck1992; Makani & Marche, Reference Makani and Marche2012). Almost half of all European workers are employed in knowledge-intensive service production (Montalvo & Giessen, Reference Montalvo and Giessen2012), and even more in the Scandinavian countries (Vinnova, 2011).

For consultants in particular, work tends to entail a strong pull toward exploitation over exploration, prioritizing billable hours, and being flexible and available for customers at all times, leading to long hours (Løwendahl, Revang, & Fosstenløkken, Reference Løwendahl, Revang and Fosstenløkken2001; Jensen, Poulfelt, & Kraus, Reference Jensen, Poulfelt and Kraus2010). Several studies have further highlighted how knowledge workers typically are complicit in their own exploitation and willingly subjugate themselves to, for example, long working hours in exchange for ‘freedom’ (Ipsen & Jensen, Reference Ipsen and Jensen2010; Muhr, Pedersen, & Alvesson, Reference Muhr, Pedersen and Alvesson2012; Michel, Reference Michel2014; Pérez-Zapata et al., Reference Pérez-Zapata, Pascual, Álvarez-Hernández and Collado2016). This has been called ‘the autonomy paradox,’ in which more autonomy, normally considered a job resource, results in employees overworking, not least of all through an overuse of technologies (email, mobile phone). Being able to work ‘anywhere/anytime’ becomes ‘everywhere/all the time’ (Mazmanian, Orlikowski, & Yates, Reference Mazmanian, Orlikowski and Yates2013; Lupu & Empson, Reference Lupu and Empson2015). Workers consider themselves to have freedom and autonomy, but somehow this freedom always seems to result in workers working more.

Knowledge work is unlike manual work in that it ‘does not program the worker’ (Drucker, Reference Drucker1999). This means that it is not possible to externally manage knowledge workers in the same way one might direct other workers. Accordingly, the workers themselves are crucially involved in the leadership of knowledge work (Drucker, Reference Drucker1999) and thus have to continuously bridge the gap between market demands and daily specific work tasks (Alvesson, Reference Alvesson2001; Hatchuel, Reference Hatchuel2002; Kira & Forslin, Reference Kira and Forslin2008). However, findings from a Swedish study conclude that the ability to master the demands of complex, flexible, and free work cannot be taken for granted (Hanson, Reference Hanson2004). The results show that a number of metacognitive skills are very helpful in managing the demands of flexible work, such as insight into one’s strengths and weaknesses, how one usually responds to stress, how to recuperate successfully, and the ability to draw boundaries for oneself and to self-regulate.

Self-leadership: A solution to the underdesign of knowledge work?

Using advanced metacognitive skills to bridge the underdesign of work can be framed as self-leadership (Manz, Reference Manz1986). This is a process of self-influence and a set of individual strategies that substitute the leadership behaviors otherwise offered by a boss (Kerr & Jermier, Reference Kerr and Jermier1978; Manz & Sims, Reference Manz and Sims1980). The theory of self-leadership posits that behavior is ultimately internally and individually controlled even though it may be heavily influenced by external leadership or other forces. With higher degrees of self-leadership, one not only regulates compliance with externally set standards but also internally establishes those standards (Stewart, Courtright, & Manz, Reference Stewart, Courtright and Manz2011); for example, when work is underdesigned. Neck, Houghton, Sardeshmukh, Goldsby, and Godwin (Reference Neck, Houghton, Sardeshmukh, Goldsby and Godwin2013) describe these skills in terms of cognitive resources that moderate demands and resources. Participating in self-leadership training has also been shown to decrease strain (Unsworth & Mason, Reference Unsworth and Mason2012).

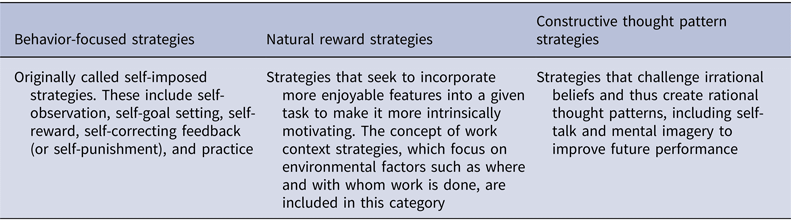

Manz and Sims (Reference Manz and Sims2001) propose three categories of self-leadership strategies: (a) behavior-focused, (b) natural reward, and (c) constructive thought patterns. These are explained in Table 1.

Table 1 Three categories of self-leadership strategies based on Manz and Sims (Reference Manz and Sims2001)

The original theory of self-leadership (Manz, Reference Manz1986) aims to foster intrinsic motivation, and the practical strategies highlighted are geared toward this. However, for knowledge workers, intrinsic motivation can usually be assumed to already exist (Joo & Lim, Reference Joo and Lim2009; Ipsen & Jensen, Reference Ipsen and Jensen2010). Another concern with self-leadership theory in this context is its reliance on cognitive and self-monitoring strategies (Politis, Reference Politis2006; Manz, Reference Manz2015). In the last 20 years, psychological research has covered many cases of self-regulation and has shown strong support for the ‘strength model of self-regulation’ (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, & Tice, Reference Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven and Tice1998; Baumeister, Tice, & Vohs, Reference Baumeister, Tice and Vohs2018). Research shows that a wide variety of acts of self-regulation, both mental and physical, seem to draw from the same pool of resources, which can become depleted. This is referred to as ‘ego depletion,’ which results in worse self-regulation (Vohs et al., Reference Vohs, Baumeister, Schmeichel, Twenge, Nelson and Tice2008; Hagger, Wood, Stiff, & Chatzisarantis, Reference Hagger, Wood, Stiff and Chatzisarantis2010). Ego depletion impairs performance on cognitively complex tasks, but not simpler tasks (Schmeichel, Vohs, & Baumeister, Reference Schmeichel, Vohs and Baumeister2003), and cognitively complex tasks, in turn, cause ego depletion (Wright, Stewart, & Barnett, Reference Wright, Stewart and Barnett2008).

In their 2011 review of empirical research of the development of the self-leadership concept, Stewart, Courtright, and Manz (Reference Stewart, Courtright and Manz2011) describe emotion regulation as a key mechanism in the internal forces of self-leadership. They state that emotion regulation can be categorized as either antecedent- or response-focused. It has been shown that antecedent-focused strategies, which involve self-regulation choices that happen before an emotional response is triggered, are more effective than response-focused strategies, which involve coping after a response has been triggered (Gross & Thompson, Reference Gross and Thompson2007).

According to this line of thinking that just because one is attempting to self-influence, it does not follow that using ‘self-applied strategies’ (Manz, Reference Manz2015) are necessarily the best way to do it. Although self-leadership aims to regulate one’s own behavior and reach outcomes in which one is involved, the aforementioned research on ego depletion and emotion regulation suggests that the most successful self-leadership strategies focus on external factors rather than internal ones, unlike the cognitive and self-monitoring strategies that are primarily proposed in traditional self-leadership theory.

Summary and research questions

Past research on knowledge work has highlighted the challenge of knowledge workers to manage the underdesign of their work. The responsibility for planning, prioritizing, coordinating, and executing work is placed to a large degree on the individual. In order to meet this challenge, it has been suggested that knowledge workers use self-leadership approaches. However, given the limitations of conventional self-leadership theory in this context, there is a need to examine self-leadership strategies in knowledge work, in particular, related to managing work intensity.

On the basis of focus group interviews with management consultants in Denmark, this study seeks to answer three research questions:

-

1. How is work intensity created in this type of knowledge-intensive work?

-

2. What strategies do consultants use to manage work intensity, and do they work?

-

3. What is the role of self-leadership among consultants in dealing with work intensity?

Method

The study presented is based on in-depth focus group interviews, a well-established technique to study people’s views and experiences (Kitzinger, Reference Kitzinger1994). It is also a technique that has gained in interest among researchers from a wide variety of disciplines over the last couple of decades, and is now a well-established method across the field of social science (Finch, Lewis, & Turley, Reference Finch, Lewis and Turley2014). Basically, the focus group is a structured group discussion on a given subject where a moderator leads the discussion. The technique has proven productive, specifically from a participatory research perspective, since it helps to make unreflected assumptions visible and to encourage working together to find ways forward; in so doing, it thus empowers the participants to become research partners (Piercy & Thomas, Reference Piercy and Thomas1998). The open-response format of group discussion often results in rich ideas that would be impossible through individual interviews or more quantitative methods. It also allows the researcher to study people in a more natural conversation mode than in semi-structured individual interviews, for example. Participants can relate their own thoughts and experiences to those of others and make links between individual and collective experiences, feeding off each other’s ideas (Smithson, Reference Smithson2006; Stewart & Shamdasani, Reference Stewart and Shamdasani2015).

Setting, sample, and participants

This study examined a group of Danish management consultants working in a small organization with 16 employees. The organization’s main business was creating and delivering bespoke trainings in sales, leadership, and business development. It is what one would call a convenience sample in that the second author was familiar with the firm, and that the management had contacted him about their problems with employees being stressed and burning out. This was thought, in part, to be caused by a lack of self-leadership skills among the employees. Thus, the organization was chosen because management consulting is viewed as archetypal knowledge work (Fincham & Clark, Reference Fincham and Clark2002; Makani & Marche, Reference Makani and Marche2012; Muhr, Pedersen, & Alvesson, Reference Muhr, Pedersen and Alvesson2012), and because the organization had experienced employee burnout. As such, they were selected with the ‘extreme case’ strategy (Flyvbjerg, Reference Flyvbjerg2006), that is, a case very likely to have information about the issues we wished to study (self-leadership, knowledge workers, and intensity) (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989; Yin, Reference Yin2003). In all, eight members of the organization (seven men, one woman) participated in the focus group interviews. The participants were in the range of 30–50 years of age, with university degrees. All but one had children still at home. At the time of the interviews, one of the respondents was working as one of the two managers in the firm. This, of course, may have affected what was said in the group. With management present, coworkers may hold back information and feelings. On the other hand, it opens up dialogue and discussions about culture and expectations that would not have been possible otherwise. There is a more even distribution of power in Danish organizations between managers and employees, which further alleviated worries about holding back to a degree that would compromise the study (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1980; Hofstede Insights, 2017).

Procedure

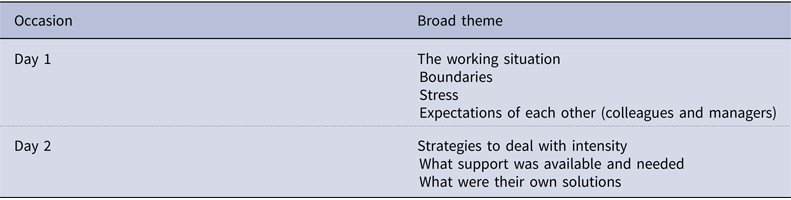

The focus group interviews took place on two occasions about one month apart, with the same participants. The group interviews were conducted in Swedish and DanishFootnote 1 by the second author, and were recorded and transcribed in their original language. University ethics protocols were followed in regards to data storage. The focus group interviews lasted 6–8 hr, which provided the opportunity to cover the topic in breadth and depth. The second author validated the accuracy of his impressions of what came forth in the first interview during the second one by a process called ‘member checking’ (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). An additional validation check was performed with the contact person at the organization after the interviews. The respondents were informed in advance of the aim and purpose of the study and were encouraged to reflect on the topic before the interviews; specifically, they were encouraged to reflect upon work demands, opportunities and capabilities for control, and self-leadership skills. The goal of the interviews was to capture areas of work intensity and self-leading strategies to deal with it. The focus group interviews were semi-structured around a number of themes that were determined in advance (see Table 2), but that allowed considerable leeway in developing and exploring emergent topics.

Table 2 Themes used in focus group interviews

Data analysis

Before analysis, a code schema was conceived with high-level codes based on Strauss (Reference Strauss1987) four suggestions: conditions, interactions among actors, strategies and tactics, and consequences. All interviews were first coded by hand, and then another round of coding was carried out using NVivo 9 software. This provided both a second review of the codes and finer granularity of the coding.

The initial general codes were further broken down into more specific codes relating to the topics of work intensity and self-leadership strategies. Following a thematic analysis procedure (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006), the analysis then moved from the level of text to the level of codes, grouping related codes together and proposing links between them. After this, codes were aggregated under new headings on a more theoretical level. Finally, the findings were summarized narratively under three main topics: (1) characteristics of the work, (2) areas of intensity, and (3) strategies. The results and analyses presented in this paper are based on these narratives and are illustrated with translated quotes. The first author conducted the main coding and analysis. After the main analysis, it became clear that the strategies identified could be divided according to whether they had a more internal or external focus, and a more reactive or proactive focus. This was an emergent theme (Bryman & Burgess, Reference Bryman and Burgess2002: 180). Initially, the strategies were coded to correspond with Manz and Sims’ three self-leadership strategies (2001) (Table 1), but on closer acquaintance with the data, these strategies proved not to be a good fit. Consequently, they were abandoned in favor of a new framework, the construction of which was based on the self-regulation literature, as a way to explain the emergent theme. The participants’ statements about self-leadership strategies were selected and all the three authors classified each one as either internal or external and as either reactive or proactive, and further indicated whether the strategy had worked, not worked, or was hypothetical. These patterns are described for each of the four categories of strategy below.

Results

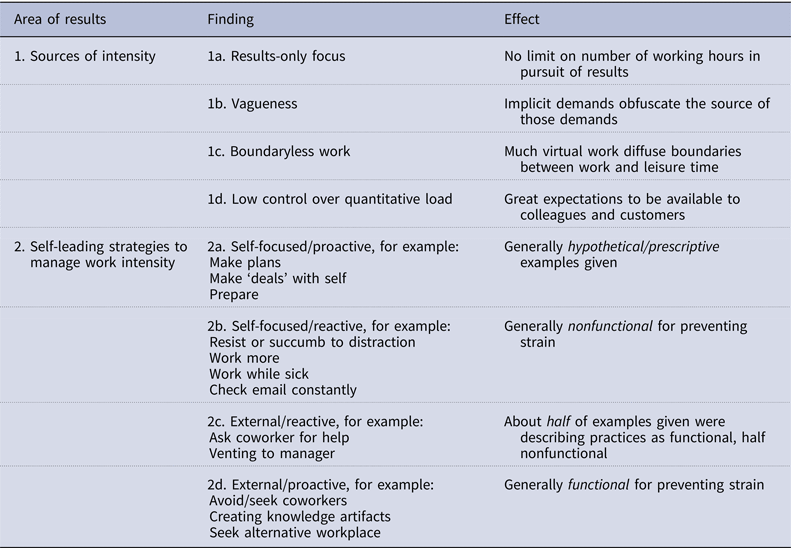

The results are reported in two parts. The first part is a characterization of the work and answers the first research question: How is work intensity created in this type of knowledge-intensive work? The second part examines the strategies used and answers the second and third research questions: What strategies do consultants use to manage work intensity, and do they work? and What is the role of self-leadership among consultants in dealing with work intensity? A very brief summary of results is presented in Table 3.

Table 3 Summary of results

On an overall level of analysis, all respondents expressed great engagement and pleasure in their work. Work engagement was described as stemming from the work being cognitively complex and stimulating. The consultants reported that they are expected to be subject matter experts in everything they do and to have a good understanding of the specifics of the customer. This finding supports the perspective that intrinsic motivation is more a point of departure than a goal outcome in understanding the challenges of self-leadership within this group of workers.

Areas of intensity in the work

The following areas of work intensity were identified from the analysis of the transcribed focus group interviews: (1) results-only focus, (2) vagueness, (3) boundaryless work, and (4) low control of the quantitative load.

Results-only focus: The ‘last 5%’ of the work

In analyzing the consultants’ stories, work was described as result-oriented, meaning that delivering results in time for deadlines took precedence over limiting working hours. The translation of theoretical knowledge into practical knowledge relevant to the specific customer was often described as the ‘last 5%’ of the work. This was something that the respondents highlighted as an issue that causes almost all of their worries and efforts. This hides a dualism in their view of their work: even though one might, as mentioned by one respondent, spend weeks thinking about how to put together an exercise that will take 2 hr to accomplish, that work is somehow considered to be in the ‘last 5%.’ Clearly, it is not 5% of the working time that is referred to, or 5% of the value to the customer. But it might take up 5% of the PowerPoint presentation, or of the time in a class given by the consultant. It is perhaps not surprising that customer-facing time, which is confined and has hard deadlines, is considered the ‘most real’ work, but it seems to cast everything else as a kind of support activity rather than an essential core activity for creating value for customers.

Vagueness

A common theme was that the organization of the work logic was based on the result-oriented culture, with little regard for the time spent to achieve results. There seemed to be no disagreement that each assignment is expected to be ‘great,’ not just good, and that it is the difficult ‘last 5%’ that provides the greatest value for customers and it is thus worth spending a lot of time on it.

This kind of result orientation may lead to difficulties in determining when an assignment is finished. The limits for this are implicit, vague, and subjective.

On the one hand [management has] no demands at all, but at the same time, they have REALLY many demands. It’s just that they’re implicit, so we’re supposed to interpret ourselves what the demands are that Carl and John [managers] have for our day-to-day work.

This shows that the idea of what constitutes ‘real work’ was implicit and depended on the individual consultant’s perception. Although one consultant felt guilty about preparing for presentations at work because it did not feel like ‘real work’ – and instead usually spent Sundays or evenings working on preparations – another consultant had no such qualms, and saw preparations as a normal and important part of the job, entirely legitimate to do during work hours.

Implicit demands from management obfuscate the source of those demands. With so much room for interpretation, consultants start to place high demands on themselves. The participants frequently mentioned that stress, and most demands, come mainly ‘from myself,’ while describing, somewhat exaggeratedly, that the results they were expected to deliver to customers should be a ‘[…] huge success every time. Fireworks!’.

A further source of vagueness is the nature of the assignments themselves, which are sometimes more standard and run on an established course, and are sometimes more ‘fuzzy.’ The fuzzy problems demand a lot of energy because they are the sources of uncertainty. ‘You can spend several days’ just figuring out how to frame the problem. The participants also stated that they can end up being responsible for things without taking part in any formal discussion.

Boundaryless work

The consultants’ work is made boundaryless by a combination of fuzzy problems that have to be solved as ‘huge successes,’ a high quantitative workload, and the need to ‘infer’ reasonable boundaries around work. There is always room for improvement but no explicit feedback for when it is good enough.

The second aspect of boundaryless work is the virtual nature of the consultants’ work. Much of it can be carried out from practically anywhere using a laptop with mobile internet. This leads to fuzzy boundaries between work and leisure time. Every space is a possible office and every time of day is possible work time. A blending of work and leisure was evident in several stories from participants who described checking their work email every day of the week, ruining a family holiday by working, watching TV while answering emails at home, and frequent and obtrusive thoughts about work.

Low control of the quantitative load

All respondents mentioned that the quantitative workload was great, and they frequently showed symptoms of stress. One manifestation of this was that it was common for ‘everyone’ to fall ill the first week or so of vacation. Consultants generally did not call in sick, certainly not if meeting with customers, but even when that was not the case, they would rather continue to work from home. Working while ill was both a way of coping with a high workload and a cause of intensity in itself, often prolonging illness.

Working very close to customers, and with several customers at the same time, often meant difficulties in predicting the amount of work over time. Having several different customers was a factor that would easily ‘overfill one’s glass’ by having to give a little extra to each customer, which was the standard. Because of this, consultants felt a lack of control over the ‘flow of work,’ and struggled to ‘keep the workload even.’

The expectation of long working hours came not only from the consultants but also from their colleagues. At the end of the focus group interview, one respondent reported the long hours he had worked in the past couple of weeks, only to be met by comments such as ‘Not more?’ and ‘Then you’re slacking off!’ Respondents describe that they had trouble limiting their working hours. On occasion, managers had to intervene to limit their consultants’ working hours, telling them to take time off. However, consultants were clear that they did not want increased monitoring or more regulated working hours as they felt this would promote a more transactional, less engaged relationship to work. Rather, they desired methods and tools for better self-managing and work planning.

Self-leading strategies for managing work intensity

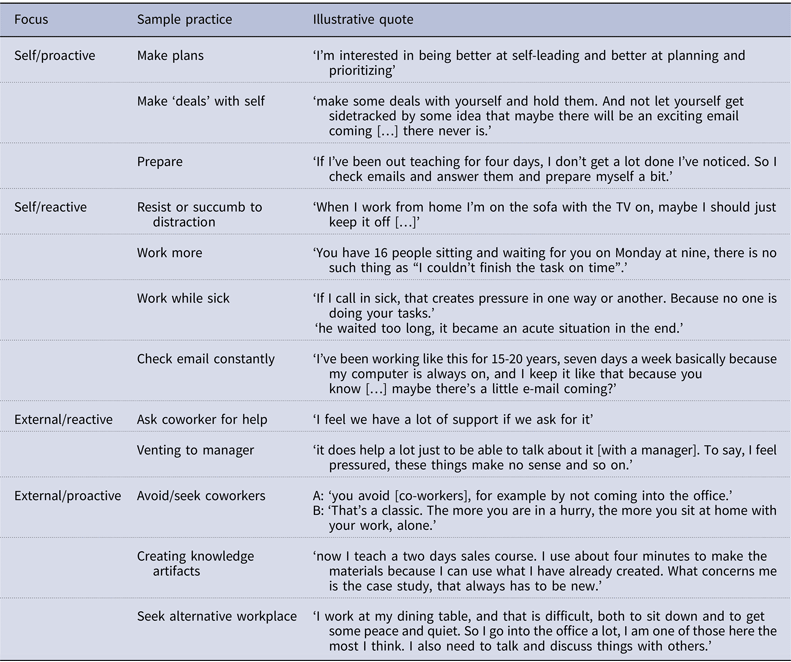

As explained in the Method section, the self-leading strategies used by consultants did not align very well with the conceptualization of Manz and Sims (Reference Manz and Sims2001) in Table 1. Instead, in the light of recent research on self-regulation and to extend existing self-leadership theory, we present an analysis of the respondents’ self-leadership strategies as being self-focused or externally focused and as proactive or reactive, resulting in four categories of strategies. See Table 4 for a summary of the strategy focus, samples of practices, and illustrative quotes. An in-depth exploration of the results is as follows.

Table 4 Focus of self-leading strategies, examples, and illustrative quotes

An overall finding was that self-focused strategies were described as hypothetical (i.e., respondents expressed something one ought to do, but did not do) or as nonfunctional (i.e., did not protect against intensity), while in contrast, externally focused strategies were largely described as functional.

Self-focused strategies

Self-focused strategies involve behaviors that act on the self or require changing oneself, rather than acting on or changing others or one’s environment.

Proactive self-focused strategies

The consultants generally recognized that being better at self-leading and creating one’s own structure in day-to-day working life would be very useful. A distant but desirable goal was to stop checking emails on Sundays. The consultants joked that participating in the focus group might ‘teach’ them how to take time off on evenings and weekends.

I would really like to be able to say, ‘OK, I’ll work from eight to four and then I’ll take some time off.’ But now it’s more like I work from eight to ten, but not very effectively.

To achieve this goal, ‘planning’ and ‘prioritizing’ were the key skills the participants thought they needed to improve. The assumption seemed to be that they would have more time left at the end of the day if they learned to work more efficiently, not by putting a boundary on the number of hours they worked in advance, and let priorities flow from that. In other words, the participants considered a strategy that required self-control (to work ‘more efficiently’), and hoped it would result in the structure they wanted, rather than a strategy that imposed the structure they wanted and allowed that to shape their behaviors (i.e., being forced to prioritize).

Many of the self-leadership strategies they described were thought-based and similar to Manz’s ‘self-talk’ strategies (Table 1). One consultant said, as if to herself, that not giving 110% in every area of life simultaneously must become more acceptable. Other examples were to make deals with yourself, such as not working during holidays and stop thinking that you might get a special interesting email at any moment (‘because you never do’), to ‘learn’ not to check email, and to ‘discipline’ yourself to ‘not think’ about work when you are not at work.

What was perhaps most interesting about this category is how many strategies were phrased as hypothetical or prescriptive, something one should do and hopefully would do better in the future, not something they had done in the past that had worked well. A clear majority of all the strategies classified by the authors as hypothetical were proactive and self-focused. The consultants would have liked to resolve the issue of work consuming their lives using antecedent (proactive) strategies (e.g., by deciding when to stop working in advance). But what they actually do is more response focused, and this does not work as well (e.g., when 4 p.m. rolls around, they do not feel that they have finished their work for the day and they cannot resist continuing, perhaps in an attempt to resolve anxiety).

Reactive self-focused strategies

The most common behavior for dealing with high workloads, both quantitative and qualitative, can be called ‘stretching yourself.’ This occurs when the consultants let work take up more time, more cognitive space, and in general assume priority in their lives. In a way, this is a failure of self-leadership in relation to the consultants’ stated wishes of not letting work consume their lives.

Another common reactive self-focused strategy was improvisation. For example, if consultants do not have enough time for preparations, they may improvise while teaching:

Sometimes I am improvising wildly, making up exercises and so on. /…/ But it is more fun to improvise when you are very well prepared, than improvising when you don’t have anything. That is really, really bad.

Other examples of reactive self-focused strategies, some of which were perhaps not deliberate, were to work when sick, to regulate emotions, and to think frequently of work (e.g., while showering, watching TV, or socializing).

The authors classified most of the reactive self-focused strategies as nonfunctional, and most of the nonfunctional strategies were reactive self-focused, suggesting that these strategies were not very effective in preventing strain.

For example, working from home, which was common, meant having to deal with distractions like watching TV, running errands, or leisurely surfing the web, all of which could result in a considerably longer workday. It was considered better to ‘[…] really be off when you’re off, and work when you’re supposed to work, instead of this vague sort of thing,’ and yet, consultants often found themselves unable to do so.

Externally focused strategies

Externally focused strategies are behaviors directed outwardly to other people or one’s situation and environment, rather than acting on oneself.

Reactive externally focused strategies

Consultants described how having several different customers could easily ‘overfill your glass’ when you have to give a little extra, which was often. When your glass is full, you can alert management, with varying results. ‘Venting’ to a manager usually felt good, but even though your glass is full, assignments still have to be divided and carried out. When asking a manager for help or presenting a problem, the response was often a deflective pep talk: ‘Oh, but I believe in you. You can do it!’ Thus, while they could voice concerns, in reality consultants did not seem to have much power over the workload. In practice, voicing concerns seemed to be more of a coping mechanism for emotional regulation than a proactive strategy to change working conditions.

Asking a colleague for help was common and replying swiftly to such requests was expected.

I feel we have a lot of support if we ask for it.

However, social support is a two-way street. Even though respondents liked to work together, there could be even stronger mechanisms against that when the pressure was on.

The authors classified about half of the reactive externally focused strategies as functional for reducing or preventing strain.

Proactive externally focused strategies

When respondents had very large workloads, it was common to stay out of the office to avoid having to socialize. They were still expected to help colleagues, answer their emails, and return phone calls. Withdrawing was one of a few ways they had to protect themselves from excessive claims on their time and attention.

Person 1: You sort them to the side I guess, for example, by not coming into the office.

Person 2: I think that’s classic: the busier you are, the more you sit alone at home with your assignment.

Some, however, tended to do things the other way around:

I work at my dining table, which is a bit of a pain, both with regards to sitting there and trying to get some peace and quiet and so on. So I actually come into the office a lot, I’m one of those who’s in here the most I think. I also have a great need to talk and bounce ideas off someone else and so on.

In addition, spatial strategies were brought up as important for relaxation. Being ‘completely away from’ work meant to be both physically and mentally away from it. One consultant accomplished this by playing baseball, something that requires his full attention. Another way of relying less on self-control to self-lead was to explicitly ask your partner at home to put more demands on your presence there.

As for hypothetical strategies, the participants’ organization did have the ambition to standardize more of its services and products to give employees more time to work on ‘the last 5%’ in order to do creative work or to make their output ‘truly perfect.’ However, they had not ‘given themselves the time’ to fully develop the standardized products, resulting in half-standardized processes and products. Thus, the time that was supposed to go to creative polish was instead spent on completing the process or product.

It’s difficult because you have to sit down and do it, and that time investment is simply too large in relation to what I personally get out of it, since I have to do it for the benefit of the others. But I don’t really have time for that because I have a lot of assignments.

Working on standardization, then, was seen as something that would benefit the organization, but the pressure on the respondents to perform in the here and now steered them away from making such an investment. Instead, they had to spend time individually completing half-standardized products repeatedly. In other words, performance pressure incentivized the consultants away from proactive preparations toward more reactive catching up. Some consultants, however, did their own standardizations, such as a folder one could just ‘grab and go’ to teach a course.

The proactive externally focused strategies were usually classified as functional, and of the functional strategies, this was the most common category.

Discussion

Traditional strategies of workforce management were intended to increase productivity and alleviate the psychologically damaging effects of small, repetitive, and boring jobs; many jobs were overdesigned, meaning that they extensively confined the worker and the worker’s tasks (Grant & Parker, Reference Grant and Parker2009). In contrast, in modern knowledge-intensive work, the challenge is rather the opposite. Many jobs are underdesigned, described as lacking security, being marked by ambiguity, competing demands, and unrelenting work pressures (Mohrman, Cohen, & Morhman, Reference Mohrman, Cohen and Morhman1995; Allvin, Aronsson, Hagström, Johansson & Lundberg, Reference Allvin, Aronsson, Hagström, Johansson and Lundberg2006). The responsibility for planning, prioritizing, coordinating, and executing work is placed on the individual (Grant, Fried, & Juillerat, Reference Grant, Fried and Juillerat2010; Allvin et al., Reference Allvin, Mellner, Movitz and Aronsson2013), which means that self-leadership becomes an important factor in how well work demands can be met. Research on management has traditionally put the manager in the center as a causal and all-embracing factor in explaining how people gain motivation and direction within organizations (Holmberg & Tyrstrup, Reference Holmberg and Tyrstrup2010). But much of that work is now expected to be handled by the employees themselves.

Past research has examined how opportunities for self-leadership can increase intrinsic motivation (Manz, Reference Manz2015). However, building upon Parker’s (Reference Parker2014) observation that designing work for motivation is ‘necessary, but insufficient,’ our study considers intrinsic motivation as a point of departure for self-leadership, instead of an outcome (i.e., having high intrinsic motivation may even create new problems) (Joo & Lim, Reference Joo and Lim2009; Ipsen & Jensen, Reference Ipsen and Jensen2010). With boundarylessness and ambiguity characterizing work, and requirements for individual planning and prioritizing being very high, we see other problems emerging, such as a risk for burnout. Being a successful self-leader in this context raises other issues, which we have examined in this study. In addition, research on self-leadership theory to date has focused largely on cognitive and self-monitoring strategies (Manz, Reference Manz2015). Operationalizing self-leadership with this perspective implies a focus on what we have called self-focused strategies.

This study makes three contributions. First, it presents an empirical description of contemporary knowledge work. The description reinforces the observation that motivation and engagement are points of departure rather than the goal, and that these in turn actually contribute to work intensity through the internalization of demands. Several studies of knowledge workers (Ipsen & Jensen, Reference Ipsen and Jensen2010; Muhr, Pedersen, & Alvesson, Reference Muhr, Pedersen and Alvesson2012; Michel, Reference Michel2014; Pérez-Zapata et al., Reference Pérez-Zapata, Pascual, Álvarez-Hernández and Collado2016) have all found a kind of autonomy paradox, where freedom to work ‘anywhere, anytime’ becomes ‘everywhere, all the time’ (Mazmanian, Orlikowski, & Yates, Reference Mazmanian, Orlikowski and Yates2013). Similarly, in this study, the internalization of demands by the participants seems to obfuscate the element of normative control and recast it as a kind of freedom. Consultants explain how demands are not stated explicitly and have to be interpreted, but that they are still quite clearly felt, for example, the expectation to produce ‘fireworks, every time’. Management’s avoidance of explicit policies and guidelines results in workers placing higher demands on themselves. They perceive themselves as active cocreators of these demands placed on them, not as passively coping with ones that are externally imposed (Pérez-Zapata et al., Reference Pérez-Zapata, Pascual, Álvarez-Hernández and Collado2016). What is crucial here is that stress resulting from such internalized demands is interpreted as a personal failing, a failure of self-leadership.

Second, this study contributes to knowledge of the phenomenon of self-leadership in the context of knowledge work by examining consultants’ self-leading strategies to handle the risks of overload and burnout. We found that the consultants’ beliefs about how they ideally should handle intensity did not, in fact, seem to be what actually helped them to do so. Self-leading was conceptualized by consultants as being disciplined, structured, and self-controlled. Becoming ‘better’ at self-leadership, through self-control, was believed to be what was lacking, and that this would protect them against stress, burnout, and falling ill. Notably however, this was usually articulated in hypothetical terms and hopes that a future self would ‘learn’ and through self-control would be better able to stop work, to stop checking emails, and to stop thinking about work. In practice, this reliance on hope often seemed to lead to overwork. The self/reactive strategies can be seen as reactions to situations that are high in demands but lack design and directions. This means that there are no buffers between demands and the individual’s need to respond (Kira & Forslin, Reference Kira and Forslin2008), and the individual herself assumes the cost of that. This is done, for example, by working more, working when sick, checking ones’ email, and other variants of letting work seep into all aspects of life. The pattern described is reminiscent of workaholism (compulsive work and thoughts of work) as a kind of failure in self-regulation (Wojdylo, Baumann, & Kuhl, Reference Wojdylo, Baumann and Kuhl2017), a failure to resist the compulsion to keep working in spite of an expressed wish to do so.

The results indicate that viewing oneself as the source of stressful demands – as knowledge workers often do – leads to beliefs that self-leadership through effortful self-control will be a solution. From the consultants’ stories of their practices, however, other strategies emerged as more successful for managing intensity. Notably, these often depended on manipulating physical space such as choosing where to work, not bringing a device along when you were supposed to be off work, turning off distractions, and standardizing assets that could be reused in work (digital or physical). The practices of consultants showed that they could indeed self-lead to manage work intensity, but that the effective self-leadership was focused on manipulating the conditions and environment surrounding their work or nonwork situations, and not so much on the internally focused use of effortful self-control, which was how consultants conceived self-leadership. Proactive, externally focused strategies can lead to better work outcomes and improve one’s ability to be entirely off work. One common strategy that was effective to manage intensity for the individual, but that might have detrimental effects for the organization as a whole however, was to ‘hide,’ that is, work from home, when the need to focus was great. Since the expectations to help colleagues were so high, physically being out of sight was effective to manage these demands, similar to previous findings that being under stress promotes withdrawal behaviors (Manca, Grijalvo, Palacios, & Kaulio, Reference Manca, Grijalvo, Palacios and Kaulio2018).

The third contribution is the addition of the perspective of ego depletion to that of self-leadership to explain the results and propose a mechanism of self-leadership in the context of knowledge work. With ego depletion in mind, we argue that it makes sense that cognitive, self-focused strategies for self-leadership would not be as effective as more externally focused strategies (such as spatial strategies), especially in the context of mentally complex work. According to research on emotion regulation (Gross & Thompson, Reference Gross and Thompson2007), antecedent, externally focused strategies (such as situation selection and situation modification) are more effective for regulating responses than reactive strategies (such as cognitive change and response modulation). In other words, trying to think differently about something or resisting an impulse to do something (checking email). In the context of the management consultancy knowledge work presented here, the work is described as often complex and fuzzy with no clear standard of when it is reasonably complete. When a person’s intention is set to stop work at a given time, that person still has to execute a proactive, internal strategy using effortful self-control at the end of the day when his or her executive powers are depleted (Sjåstad & Baumeister, Reference Sjåstad and Baumeister2018). By applying one’s willpower earlier in the week or day to plan and structure the working situation more physically (if possible) pays off later because less control is needed to comply with one’s original intentions (Fujita, Reference Fujita2011; Ent, Baumeister, & Tice, Reference Ent, Baumeister and Tice2015; Duckworth, Gendler, & Gross, Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016). We propose that to be effective, self-leadership in knowledge work should reduce reliance on self-applied, thought-focused strategies in favor of externally focused, proactive strategies to regulate behavior.

Implications

Much vagueness exists concerning the quality criteria in knowledge work (Alvesson, Reference Alvesson2001), like that of management consultants. Some of this might be unavoidable due to the nature of the problems the customer has – if the problems are very clear cut, the customer may not need to turn to management consultants in the first place (Werr & Styhre, Reference Werr and Styhre2002; Kitay & Wright, Reference Kitay and Wright2003). This is also what makes the job interesting. Some of the vagueness reported in this study, however, seemed to stem from ‘implicit’ demands and how consultants have to infer what managers expect. Apart from taxing the consultant’s cognition itself, this seemed to be where self-expectations were both raised and internalized, something that resulted in very different subjective appraisals of the work demands.

Although past research has emphasized self-applied strategies for self-leadership (Manz, Reference Manz2015), our findings extend and externalize self-leadership to also become an issue of designing work by continually orchestrating external work conditions for oneself, similar to the concept of job crafting (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski and Dutton2001). Job crafting is about ‘the physical and cognitive changes individuals make in the task or relational boundaries of their work’ (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski and Dutton2001: 179). Although the nature of knowledge work and the demands posed by fluctuating market make it impossible to design a job once and for all, it is clear from this study that workers, and in extension organizations, may suffer from having too little design. In this context of work intensity, thinking in terms of (continual) job crafting comes closer to addressing root causes of problems rather than working from the presumption that there is some adaptation at a purely individual level that is sustainably possible (Hackman, Reference Hackman2009). If workers indeed have autonomy, it is better for them to invest their energy earlier in the arrangement of work situations than later to keep them from failing to resist the temptation to overwork. Likewise, the organization can help their consultants manage work intensity without further adding to the cognitive load through work design by providing guiding policies, procedures, or rules; being more explicit about demands; and considering the environment available. It is not about robbing employees of autonomy – and consultants explicitly expressed not wanting to punch a clock – but rather about buffering them from incessant demands on their attention, the knowledge worker’s most precious resource (van Knippenberg, Dahlander, Haas, & George, Reference van Knippenberg, Dahlander, Haas and George2015).

Limitations and future research

Given the small case and qualitative approach, we cannot empirically generalize from these findings. Further research is needed, for example, to determine the conditions under which these results might hold true for others. The proactive, self-focused strategies that were mostly hypothetical for these consultants could perhaps work very well in actual practice, and under different circumstances, they might be easier to practice.

Moreover, one needs to acknowledge the particular logic of consultants’ work. Knowledge workers who are based in long-term teams and are not expected to react directly to customer demands may have rather different strategies at their disposal than do management consultants.

Future research needs to investigate further workforce management and knowledge worker practices in knowledge-intensive business services. In this context, self-leadership strategies emerge as a central topic because knowledge-intensive business services are populated by professional, motivated, and self-directed coworkers. Although we, in this study, question the relevance of the historical emphasis on self-applied and internal strategies for modern knowledge work, these strategies at least generalize more easily across situations. The question is: Do external, proactive strategies generalize across different work settings and organizations, or are they specific to the unique conditions of a particular workplace and work logic? Another area to investigate is the prevalence of external, proactive ways of self-leading through job crafting and how these affect work intensity. This would further bridge the gap between the more general theory of ego depletion and self-control and applied theories of self-leadership at work.

Future empirical studies might examine interventions aimed to encourage the use of more external, proactive strategies and whether this has an effect on levels of stress or hours worked. A general test of the model proposed here but with quantitative measures would also be beneficial: to what extent does use of different categories of strategies relate to stress and performance, with cognitive complexity of the work as a possible moderator; does it confirm what is suggested in these results?

The problem of knowledge workers’ productivity (Drucker, Reference Drucker1999) continues to have potential for improvement in its solutions.

Concluding remarks

The goal of self-leadership should not be to maximize the use of effortful self-control (Fujita, Reference Fujita2011; Duckworth, Gendler, & Gross, Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016), but the successful implementation of desired behaviors that support one’s chosen goals. Our study of management consultants, whose work is both cognitively complex and highly demanding of self-leadership, suggests that externally focused, proactive strategies work best in practice for shaping one’s own behaviors as desired.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare under grant number 2012-1253.

About the Authors

Gisela Bäcklander is a doctoral student at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden. She teaches team leadership, human resource management, and organizational psychology at KTH. Her research interests focus on knowledge-intensive work, self-leadership, and collective forms of leadership.

Dr. Calle Rosengren works as Assistant Professor at Lund University. His research examines working time, with a particular focus on the ongoing relations among new technologies, organizing structures, cultural norms, and work practices.

Dr. Matti A. Kaulio is an Associate Professor at KTH Royal Institute of Technology. His current research deals with leadership in innovation and business transformation.