Introduction

In the fall of 1637, in the bustling port of Lisbon, the young Manuel de Almeida Falcão prepared himself to face the Atlantic for the first time. Like many soldiers involved in the war against the Dutch, he was leaving for Brazil, a Portuguese possession that was then part of the powerful Hispanic monarchy. Iberia had become united in 1580, after the demise of the Avis dynasty, with the Portuguese crown and all its domains being inherited by the Spanish Habsburgs. The journey of Manuel de Almeida Falcão was about to embark was far from trivial. According to Michael Zuckerman, the crossing of the ocean was a disturbing event, provoking great anxiety among travellers beset by a sense of emotional separation from their birthplace and from their families and friends.Footnote 1 However, the young soldier did not seem to be particularly traumatised by the experience. Nor was he disturbed by the overthrow of the Habsburg kings in Portugal—in 1640 a dissatisfied part of the Portuguese aristocracy led a coup against Madrid and established the Bragança dynasty in Portugal. He served six years in Rio de Janeiro, where he likely encountered leading members of the Correia de Sá family, as his participation as a superior officer in a later military expedition led by Salvador Correia de Sá e Benevides suggests. In the meantime, he had returned to Europe in 1643, only to re-embark again the next year. After a skirmish with ships from Dunkirk near the Azores Islands, he returned to Brazil, this time as a member of an expedition intended to protect the always harassed American sugar fleets.

By 1646, he was back on the Iberian Peninsula and serving on the Alentejo frontiers against the armies of the former Habsburg rulers. Although very brief, his stay in Lisbon, in 1647, was probably long enough to reunite with the highly influential Correia de Sá, who had governed Rio de Janeiro during Manuel’s first sojourn in that city (1637–42), and who was now drafting plans for another south Atlantic expedition. Correia de Sá now had his eyes on Luanda, which the Dutch had seized in 1641. The plan of the leading minister of the first Bragança king, John IV, aimed to restore the slave trade between that trading post and the demanding sugarcane fields of Brazil;Footnote 2 it was also a way to redeem Spanish silver through the commercial connection that linked Rio de Janeiro to Buenos Aires. This must have looked like another imperial opportunity. So, unsurprisingly, on 24 October 1647, Manuel de Almeida Falcão, now sergeant-major, sailed from the Tagus River in the company of Salvador Correia de Sá, whose political influence might have contributed to Manuel’s promotion.Footnote 3 In 1650 he returned to the mother country and in the following years served in ships guarding the Portuguese coast and the American fleets against North African privateering. He officially retired in the aftermath of Alentejo summer campaigns of 1657, but that did not stop him from being considered for the government of São Vicente, in southern Brazil.Footnote 4 In 1658, the marquis of Cascais, donatary (landlord) of that captaincy, recommended him to be captain-major (capitão-mor),Footnote 5 which is further proof that he was well-connected with leading aristocrats. The proposal was accepted in the Overseas Council and favourably dispatched by the king, but he never took office. He probably changed his mind but, now a knight of the Order of Christ, he kept his eyes on the other side of the ocean. Some years later, in 1662, he applied for the post of captain in Rio de Janeiro, although unsuccessfully.Footnote 6

There is something remarkable about this constant back and forth. In fewer than fifteen years, from 1637 to 1650, Manuel de Almeida Falcão crossed the Atlantic at least eight times, in many directions. Between 1645 and 1651 he was in Brazil, at least once, in the mother country, in Angola for three years, and then back in Portugal. This kind of migratory behaviour between the Atlantic shores was not unique to Manuel de Almeida Falcão. He was representative of a group of men, soldiers, and low-ranking officers, who actively participated not in one but in several mid-seventeenth-century military campaigns around the Portuguese empire. They could have chosen to stay in one conflict zone—in Brazil, Africa, Iberia, or India—but they chose differently. Their constant back and forth and their reasons for such apparently frenetic movement around the empire has never been a point of discussion for historians interested in the circulation patterns of the Portuguese empire. In fact, I should underline, the phenomenon has never been identified, maybe because this trait was characteristic of an understudied group. Thanks to authors like Stuart Schwartz or more recently the collective efforts of the Optima Pars team, we know the social background and the recruitment patterns of several groups that participated in the Portuguese overseas experience. The empire was a space for economic opportunities for merchants and skippers, but also one in which judges, bureaucrats, clergymen, and governors found opportunities for professional progression if they were willing to embark in transoceanic journeys.Footnote 7 We know much less about military personnel, apart from the fact that this was a heterogonous group. Recent studies have given us some hints about social backgrounds and about the all-important mechanisms by which they were selected,Footnote 8 but these do not provide an explanation for a restlessness that started in the mid-1620s and, as far as I know, was not replicated by any other group.

Furthermore, the itinerancy of Manuel de Almeida Falcão and his colleagues does not quite fit the useful typology that Luiz Felipe de Alencastro established to classify voluntary migration in the early modern Portuguese world. According to the convincing (although rather unexplored) theory of the Brazilian historian, the empire promoted the emergence of what he called the “colonial man,” who, irrespective of his social status or career choices, tended to depart the mother country and never returned. But, at the same time, the empire also produced what Alencastro called the “overseas man.” This was someone that left the mother country to come back, “to enjoy in the Metropolis their social [and economic] gains,” in Alencastro’s words.Footnote 9 Both were familiar figures in all Atlantic empires, and, in the end, Manuel de Almeida Falcão had to become one or the other. Perhaps, after all those restless years, he got homesick and returned home to his daughter, Sebastiana Maria de Almeida, whose future he tried to ensure with a royal annuity (tença).Footnote 10 Or, maybe, he simply spent his last days enjoying the tropics.

We do not know what happened to him in the end, but we know that he cannot be described simply as a colonial or an overseas man, rendering these categories useless. The remarkable mobility displayed by him and his comrades in such a short period of time calls for historical scrutiny. What motivated this specific behaviour? What was the reason behind the constant back and forth? In this study, I will argue that the predisposition to circulate in such a way was a result of a combination of circumstances unique to the period from the early 1620s to the late 1660s, and especially between the 1640s and 1660s. During this time two major wars broke out in the Portuguese world, first in the South Atlantic against the Dutch, then in the North Atlantic, in Iberia, against the Habsburgs. These were vital conflicts that acted as magnets for military personnel looking for places to serve, especially if those places were highly regarded by the crown. And none were more highly regarded than the fight for empire against Dutch “heretics” in the South Atlantic, or the fight for independence in Iberia. The prevalent political culture of negotiation and reciprocity between crown and vassal was crucial, channelling men and resources for those scenarios. Like any other group, these soldiers and low-ranking officers played within the rules of a very effective incentive system. An imperial mentality that did not perceive the overseas territories as only platforms for commercial exploitation was also important: a top-down perception of empire would have discouraged military service in these territories. I also contend that such peregrination was for the most part confined to the Atlantic and that it came to an end when peace was reached with the Habsburgs and with the Dutch. To be sure, military personnel continued to move around after the 1660s just like any other group. There was not a return to the situation prior the 1620s and 1630s, when the small size of the Portuguese detachments in the South Atlantic did not exactly promote circulation; they were far too small to absorb many men.Footnote 11 After the 1660s, men like Manuel de Almeida Falcão would certainly be co-opted by the Portuguese imperial effort in America, Africa, or Asia, but the constant back and forth across the Atlantic came to an end.

The study is conceived within the framework of Atlantic history, if not in the elusive Braudelian sense,Footnote 12 or within the far-flung conceptual framework of David Armitage’s “circum-Atlantic history,”Footnote 13 at least as an approach that addresses the Atlantic as a unit of historical analysis and an organizing principle of historical research. As an analytical tool, it is certainly perfect to address the way a given group, as heterogeneous as it may have been,Footnote 14 conceived a space that included not only the Portuguese territories in the South Atlantic, namely Brazil, but also the mother country. These contested territories constitute the geographical canvas of this study.

An underlying intention of this article is to help to consolidate the place of the Portuguese Atlantic system in the research agenda of this subfield. Although the Atlantic history paradigm is not a novelty among historians of the Portuguese empire,Footnote 15 their results seldom receive the international recognition they deserve. It has probably something to do with the well-known failure to participate in the broader historiography that Roquinaldo Ferreira underlined in his survey about recent historiographical trends of the Portuguese empire.Footnote 16 It is true that the Portuguese Atlantic has been recently included in several collective works, like the ones edited by Jack Green and Philip Morgan, and by Bernard Bailyn and Patricia Denault, both in 2009, and by Nicholas Canny and Philip Morgan, in 2011.Footnote 17 However, the general assessments produced for these collections, like those of A. J. R. Russell-Wood,Footnote 18 as good as they are, should not be the only way forward in regard to the internationalization of the Portuguese Atlantic, not least because, as Alison Games has argued, this is a subfield that requires archival research to remain interesting.Footnote 19 So, in a certain way, I will try to follow the road previously paved by Luiz Felipe de Alencastro, whose work turned the Ocean into the centre of the narrative.

Preconditions: Ambiguous geographic hierarchies in the Portuguese Atlantic World

The Portuguese, during the early stages of their global expansion, developed an acute conscience of empire that was essentially based on moral theology.Footnote 20 Religion, in general, and the pope, in particular, helped sustain Portugal’s initial overseas ambitions. In fact, it was convincingly argued that the “Crown’s only source of legitimacy for its overseas expansion was the papal authority,” since the Portuguese did not have the military might of other European powers.Footnote 21 This was the time when the Avis kings surrounded themselves with theologians and canonical juristsFootnote 22 who controlled an institution that played a crucial role in the matters of empire: the Mesa da Consciência (Board of Conscience).Footnote 23

Everything, from commerce to war, conveyed a theological charge until the 1578 expedition to Morocco, where the young Sebastian was killed in the battle of Ksar el-Kebir (also known as the battle of the Three Kings). During the subsequent Iberian unification, religion remained undoubtedly very important, however the Portuguese imperial imagination seems to have lost its original structural component: moral theology.Footnote 24 According to Giuseppe Marcocci, this was partly the result of some institutional transformations brought by the Habsburgs, which included the transference of the Mesa da Consciência to Madrid. Marcocci convincingly argued that this council was no longer able to influence the Portuguese imperial thought and practices, at least in the same way it did before;Footnote 25 certainly the creation of other institutions where the matters of empire were discussed, namely the Council of Portugal (Conselho de Portugal)Footnote 26 and the Council of the Indies (Conselho da India),Footnote 27 did not help. In this respect, it is worth mentioning that, under Habsburg rule, Lisbon also lost control of the rewards system when the office where petitions for services rendered in the empire were ultimately analysed moved to Madrid. To the dismay of some contemporary observers,Footnote 28 a crucial instrument of the Portuguese expansion had just change hands.

Despite a substantial shift in the fundamentals of the original medieval and early sixteenth-century expansion, the empire remained critical to Portuguese identity.Footnote 29 The introductory remarks of Luís Mendes de Vasconcelos, in his Do Sitio de Lisboa, published in 1608,Footnote 30 about the way Lisbon opened to the Atlantic Ocean clearly show how the Portuguese understanding of the world had been changed by their overseas experience. Although the word “empire” never took root in the Portuguese political discourse, imperial motifs were a pervasive feature in the crown’s consecration ceremonies, revealing how important the empire was to the self-representation vehicles of the monarchy—so much so that Sebastian I even started to use the imperial honorific Majestade (Majesty).Footnote 31

During the Iberian Union (1580–1640) a strain of imperial rhetoric gained ground in Portugal as a result of the intrinsic political tensions that appeared in the Habsburgs multinational world. The Portuguese imperial conscience was successfully integrated in Spain’s imperial ideology.Footnote 32 However, the merger left plenty of room for old rivalries to resurface and for new ones to emerge. At stake was the place of each kingdom in the great political conglomerate of the Habsburgs, and, as Pedro Cardim has shown, the Portuguese had no qualms about using the size of their global empire to assert their political primacy. For example, the Memorial de la Preferencia, que haze el Reyno the Portugal, y su Consejo, al de Aragon, y de las Sicilias… (1627) was an attempt to position Portugal above Aragon. The author, Pedro Barbosa de Luna, claimed that there was no comparison between the great military deeds and religious achievements of the Portuguese and the ones performed by the Aragonese in the Mediterranean. Others, like the well-known João Pinto Ribeiro, followed a different road, famously complaining about the misappropriation of human resources in Iberia. According to this jurist, the Portuguese were getting the short end of the stick, since their soldiers were being forced to fight for Castile in Europe, leaving the widespread Portuguese imperial outposts very vulnerable.Footnote 33

There is not much clarity about the role played by imperial ideologies in the Portuguese political discourse in the aftermath of the 1640 secession. Some scholars claim the political circumstances of the secession precluded any real attempt to establish an integrated idea of empire. There were other pressing preoccupations. To the great Brazilian historian Evaldo Cabral de Mello, those circumstances did not leave much room for abstract theorizations of empire in a rebellious agenda,Footnote 34 which was mainly focused on the privileges that the Habsburgs allegedly supressed. The seditious aristocracy was too busy trying to justify its “heinous” actions to an audience of suspicious European kings.Footnote 35 In his book about the Castilian and Portuguese relations in Asia, Rafael Valladares emphasised the indifference that the Bragança showed to the fast receding Portuguese territories in that part of the world.Footnote 36 The economic decadence was painfully obvious (during the second half of the seventeenth century the Estado da Índia ran frequent deficits) and the new dynasty certainly did not make much of an effort to re-establish the former symbolic status of those possessions. As the Spanish historian shows, even the once-vigorous crown-backed historiography of the Portuguese military feats in Asia was put on hold: between 1642 and 1667 the position of cronista geral (chronicler) and guardamor (chief archivist) of the archives of Goa, previously occupied by leading historians like Diogo do Couto (1542–1616) or António Bocarro (1594–1642), was left vacant.Footnote 37 This administrative option highlights a lack of commitment to preserve the historical memory of the old glories of the eastern empire—the peak of the Portuguese expansion process.

To a certain extent, the conceptual developments of empire became, during this period, an endeavour of the lesser clergy, fairly unimportant and frequently entwined with messianic concerns. (Vieira’s Esperanças de Portugal, Quinto Império do Mundo is probably the best example of this utopian literature).Footnote 38 To other scholars, the empire not only was a pressing topic in the agenda of the secessionist kingdom but it was also a rhetorical asset, a legitimizing argument. During the 1640s and 1650s, Portuguese diplomats were constantly trying to establish a connection between the size of the empire and the new status of the house of Bragança.Footnote 39

As in any other time, the abstract theorizations of empire published in the aftermath of the 1640 secession, like the famous Tractatus de Donationibus Jurium et Bonorum Regiae Coronae (1673), by which Domingos António Portugal tried to justify Portuguese primacy in the Indian Ocean, entailed a top-down vision of empire. Overseas territories did not have the same prestige as the mother countries because they were generally considered to be beyond the limits of civilization.Footnote 40 Europe and the Europeans were frequently represented at the top of a symbolic hierarchy of continents and peoples. As the frontispiece of Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570) shows, iconography was particularly effective in spreading this idea of European supremacy, at least among more erudite groups. Ortelius famous piece projects a stereotyped vision of other continents, which are personified and represented in a portal. In it America, almost nude, occupies the bottom of the portal and is depicted in way that underscores the innate savagery of the continent and its people, namely the presence of cannibalism.Footnote 41

For a European powerhouse like the Habsburgs, with clear political ambitions over the Old World, the American territories seemed far less important, even after the Spanish branch lost the imperial title. However, as Pedro Cardim recently underlined, the Portuguese case was far different. They had no continental ambitions in Europe, making their overseas expansion much more than a fortuitous accident in distant lands. From the start, going beyond Europe had been “the only alternative for political elite determined to broaden their horizons.”Footnote 42

I would go a bit further than Cardim’s assessment, arguing that, for a while, the top-down vision of empire coexisted with a blurrier conception of the empire as a diffuse aggregation of discrete territories. Beyond sophisticated literary efforts, there was a much more balanced approach that did not entail an immediate symbolic devaluation of rich captaincies, and these can be identified at the highest spheres of Portuguese politics during the mid-seventeenth political crisis. For example, in 1673 the Overseas Council stated, regarding a request for ammunition from Pernambuco, that “those Conquests are the arms of this mystical Body of Your Highness’s Monarchy, and this [Brazil] should be preserved uniformly, being Your Highness the Lord and Prince of this Kingdom as is of the same Conquests.” The reasoning was later reinforced. The counsellors argued that “it was same as what Your Highness ordered in past years in the continuation of the war with Castile; when a Province had [a] need it relied upon another, for help as well as ammunition, without differentiation … taking into consideration only the preservation [of the province].”Footnote 43 The use of the term “Conquests” for the overseas territories entailed a hierarchical connotation, suggesting that they were in a subordinate position.Footnote 44 However, the general tenor of the speech was much more balanced, almost suggesting the idea of aeque principaliter, that is, an egalitarian union between those territories and the mother country.Footnote 45

The influential Duke of Cadaval (president of the Overseas Council) conveyed this kind of understanding in 1672, during a special meeting. New financial solutions had to be found for an empire in dire straits. And the plan of the influential courtier could only be devised in accordance with an understanding of empire that was unwilling to attribute a mere ancillary status to the overseas territories. Cadaval proposed to set aside revenues collected in the customs house of the mother country—but largely generated by the colonial trade—in order to secure the means for the defence of the overseas territories, especially Brazil.Footnote 46 There was definitely a concern that went beyond the mother country’s well-being, which the highly influential António Vieira had taken even further. In a sermon delivered in Bahia shortly after the arrival of the first viceroy, the Marquis of Montalvão (thus, even before the Portuguese secession), the Jesuit had already condemned what he considered an unacceptable drainage of resources for the benefit of the mother country. He blatantly championed a solution that secured Brazil’s general interests: “Everything that Bahia yielded, should be for Bahia, everything that [we] took from Brazil, [we] should spend for Brazil.”Footnote 47 It was as if Brazil was not a subordinate part of the Portuguese monarchy. Vieira’s almost insolent words seem to reveal an arrangement by which instead of being a kingdom with its dependent conquests, the mid-seventeenth century Portuguese monarchy was more like a composite state, as Nuno Gonçalo Monteiro and Mafalda Soares da Cunha have suggested.Footnote 48 In that scenario the overseas territories were more like autonomous polities. One of the main characteristics of this form of political organization, the mutual compact and permanent negotiation between the crown and local elites, was certainly a pervasive feature in the Portuguese world.Footnote 49

At a time of great political and military distress, not even Lisbon’s pre-eminence was completely assured. In fact, there were moments when the new dynasty, fearing the might of its powerful neighbour, which wanted to reassert its sovereignty, considered moving the court southwards, to Brazil. In one instance mentioned by Vieira, John IV had outlined such a plan shortly before his death.Footnote 50 Due to the military imbalance in Iberia, the Braganças could not be completely sure about the security of their foothold in Europe, at least until 1668. In a way, such a move was a question of political survival.

Vieira even submitted a proposal for Brazil’s independence as a way to sustain a war on two fronts. The plan entailed a matrimonial union with the house of Bourbon. John IV would step down and hand over the realm to his first-born son, prince Teodósio, previously married to the “Grande Demoiselle,” Duchess of Montpensier and niece of Louis XIII of France. Afterwards, he would assume political control of a new overseas kingdom, comprising not only the southern part of Portuguese America, but also Maranhão and the Azores.Footnote 51 To be sure, these political solutions were rejected by men like Sebastião de Magalhães, Peter II’s confessor,Footnote 52 who dismissed the transference of the court as an absurdity, and the successful separation from Spain eventually made the point moot. But the simple fact that they were recommended is significant. Such ideas would not be possible if the stringent top-down perception of empire had been shared by everybody.

This mid-seventeenth-century political undertone of intra-imperial equality became an indelible feature of the institutional and cultural character of Portuguese expansion, which was marked by a proliferation of powers,Footnote 53 and which, I believe, helped provide a rather favourable attitude towards the patterns of circulation followed by men like Manuel de Almeida Falcão. In spite of its overwhelming specificities and the fact that some settlers envisioned returning to the mother country,Footnote 54 Brazil was designed to reproduce the mother country’s society.Footnote 55 Unlike the Puritans in North America, there was no intention of establishing “a city on the hill.”Footnote 56 In fact, even the natural wonders of America could not avoid being compared to the mother country’s geographical features. For example, the Jesuit Fernão Cardim recalled the rivers Tagus and Mondego in his late-sixteenth-century account, when he described the landscape of Guanabara Bay.Footnote 57 In contrast to what had happened in the Spanish Empire, Brazil shared with the mother country the same rules, ordinances, and regulations, although they were often enforced with some delay. For example, the Regimento das Fronteiras (frontier regulations), which were an attempt to rationalize Portuguese military procedures, was dispatched to the New World only in 1653, eight years after being enacted.

Brazil was certainly deprived of a university, whose establishment was demanded by the municipal senate of Salvador da Bahia in 1663. However, as others have underscored,Footnote 58 the crown’s rejection at that time was probably due to the influence of Coimbra, which sought to preserve its monopoly on higher education. It was not a product of royal slight, and had nothing to do with the political status of the American territory.

Brazil did not possess palatine councils (why should it have had institutions that needed to be close to the king?), but it did have a high court of appeal (Tribunal da Relação). After being suppressed in 1626, the Relação was re-established in Bahia in 1652, in response to a petition from the city of Salvador. The tribunal topped a network of judicial districts (comarcas), just as in the mother country. Below the latter were the municipalities, which were the cornerstones of Portuguese colonization from Macau to Maranhão, as Charles Boxer pointed out long ago.Footnote 59

As spaces where local interests were actually represented, municipalities were vested with the kind of authority that suggest the crown was more than willing to spread the traditional privileges and dignities of the mother country throughout the empire. The overseas territories were extended polities and not mere platforms of economic exploitation, exclusively destined to produce surpluses for the greater good of the metropolis. The crown awarded to some American cities, and their citizens, the same constitutional rights given to other major cities in the mother country. For example, in 1646, the senate of Salvador da Bahia received the same privileges that had been extended to Oporto. At that time, someone in the mother country even proposed additional prerogatives to the “City of Bahia … Metropolis and Head of the great state of Brazil”: the king should alter his royal title to include a reference to the New World, and the city should be awarded with a seat in the Cortes, or general parliament.Footnote 60

Such proposals were certainly compatible with the political leeway already conceded to some Brazilian municipalities. For example, in 1644, the municipal senate in Rio de Janeiro was vested with the power to elect its own governor if something happened to the royal nominee,Footnote 61 once again suggesting the loose imperial attitude towards hierarchies. The political agreements ratified by the senate of Salvador da Bahia and the governor general, the count of Ericeira, in 1652, regarding the payment of more than 2000 regular soldiers, points in the same direction. As in other municipalities, in the Portuguese empire, the Bahia aldermen replaced the king’s officials in that instance, but in exchange, they imposed a binding provision that forbade the mobilization of those men, outside of Bahia.Footnote 62 The royal government recognised the aldermen’s military authority and shared with them custody over the colonial army.

This perception that the overseas territories were not necessarily less important than European ones was understandingly strong among the settlers, and not only in the Portuguese Atlantic world. In his research about the ideologies of the British Empire, Anthony Pagden stated that London’s imperial status was regularly perceived through the unassuming lenses of patrocinium (protectorate) and not imperium.Footnote 63 And the English Civil War of the mid-seventeenth century would eventually lend additional visibility to these “questions about the exact location of imperial authority.”Footnote 64 So it is hardly surprising that the rhetoric settlers used to justify the several revolts that sprouted throughout the Portuguese empire mimicked the separatist reasoning of the 1640s.Footnote 65 If Portugal, or even England, could legitimately exercise the right to revolt against the tyranny of their kings, why should they not do the same? After all, they were subjects with the same rights as those who lived in the mother country. Such an unbiased point of view would play a crucial role in the peregrinations of the aforementioned Manuel de Almeida Falcão and his peers. It provided a favourable mental framework for a bellicose time when military service in the New World was almost as valued as was service in Europe.

Service and Expanding Empire

As was true of many other European countries, Portugal had a political culture anchored in negotiation. The relationship between sovereign and subjects, in particular, was guided principally by what is conventionally called the economy of the gift. Several historians, following in Marcel Mauss’s footsteps,Footnote 66 have underlined the crucial role of reciprocal obligations in ancien régime societies. António Hespanha, in particular, has unearthed clear evidence about this cycle that made the service rendered to the crown and the expected royal reward crucial elements to the formation of the early-modern states.Footnote 67 The concept, now generally and more adequately called economia de mercê (economy of reward),Footnote 68 meant that those who served the crown had a legitimate expectation that needed to be redeemed by the king under the penalty of failing in what was one of his main functions, namely, doing justice, in this case, distributive justice. It should be remembered that the king was not thought of as an agent of social or political change, at least in his vassals’ eyes. Quite the contrary, in fact. As the supreme judge, he had to be especially mindful of a principle that would become a cornerstone of the intentionally unequal early-modern societies, and of which he was constantly reminded: “give each one what is his.” Therefore, the king needed to be fair—mindful of everybody’s place and merits—not only when distributing rewards, but also when distributing punishment, when it was justified. Otherwise, as was underlined by the jurist António de Sousa Macedo, he might even lose his kingdom.

António Vieira even considered that that kind of injustice (failing “to give each one what is his”) was the root of the all Iberian military setbacks in their war against the Dutch in America. The skilful Jesuit resorted to an allegory and stated, “It is therefore the disease of Brazil … the lack of appropriate justice; both the punitive justice, which punishes the wicked, and the distributive justice, which rewards the good.”Footnote 69

According to Christian dogma and classical influences, namely Aristotle’s writings, there were also considerations of liberality that made the fulfilment of the vassals’ expectations almost compulsory. Liberality was normally seen as a royal virtue, that when conventionally displayed would allow them to come closer to God.Footnote 70 Cupidity would alternatively lead to the destruction of royal power. Liberality was the way to secure the subjects’ collaboration in any endeavour. According to the Jesuit António Moreira Camelo, liberality was “very powerful to seize wills and to captivate moods.”Footnote 71 Often the need to reward services performed on behalf of the monarchy superseded normal concerns in societies obsessed with status, birth, and honour. Traditional preoccupations with purity of blood and with manual occupations were sacrificed to a greater purpose.

As Fernanda Olival noted, “serving the crown, with the purpose of asking for rewards, became a way of life for different sectors of the Portuguese social space. It was a strategy of material survival.”Footnote 72 Those who served the crown were not moved by patriotism or even by love for their king. They did it because they wanted to be rewarded with one of the several grants the king had at his disposal. Regarding the types of service that were most likely to be rewarded, there were no major restrictions until 1706 (when more comprehensive ground rules were adopted). Several groups took advantage of this reward system without setting foot on the battlefield. However, some of the royal favours, like the habits of the military orders and commanderies, were especially geared to reward military achievements, along with diplomatic missions and high civil positions. Additionally, the reward system always kept pace with Portuguese expansion. Originally built around the well-known Christian reconquista, the Portuguese military thought was carried to North Africa, where the fight against the Moors gained momentum during the reign of Afonso V (1448–81). Insignias of the three military orders (Christ, Avis, and Santiago) had been established with the purpose of fighting the infidel and to expel them from Iberian territory. In this sense, they truly circumscribed Christianity’s geographical frontiers.Footnote 73

The struggles against the Moors in North Africa remained pivotal in Portuguese military thought, as was clearly revealed by Francisco Manuel de Melo. While writing about the recruitment of noblemen to serve in the Iberian coastal galleys against Muslim privateers, the well-known author stated that “Africa,” namely Ceuta, Tangier and Mazagan (present-day El Jadida), was a “superb school of the Portuguese prowess.”Footnote 74 However, from the mid-16th century onwards, those insignias were no longer exclusively attached to the war effort in North Africa. For the first time, services performed in India and in the galleys of the Algarve coast could be equally rewarded. Ironically, these new guidelines were significantly sponsored by the young king Sebastian, who was later condemned for his disastrous insistence on the fruitless campaigns in North Africa, where he would die in the battle of the Three Kings.

In 1607, Philip III did the same for services rendered in Angola, where the Portuguese had faced stiff resistance since 1579. According to a royal decree, military achievements in Angola should be rewarded in the same way as those performed in North Africa, in the warships off the Portuguese coast and in India.Footnote 75 America was apparently left out of this wide-ranging policy, which nevertheless shows the Portuguese commitment to their overseas territories. In a way, it was also a matter of reputation attached to America as a battlefield, something that was going to change in the coming decades.

Political priorities and military reputation: shaping new patterns of circulation

It was the Dutch attack that redefined Brazil’s place in the hierarchy of priorities of the Portuguese crown, which, in the meantime, had been inherited by the Spanish Habsburgs. As the ongoing war in Flanders clearly showed, the Dutch were a mighty adversary, perfectly capable of dislodging the Iberians from that part of America. Thus, it is not surprising that the status of the American territory gained a new appreciation after the Dutch invasion. In a certain way, Brazil almost became sacralised as a battleground against what was perceived the Dutch Protestant heresy, which enhanced that theatre of action’s capacity to attract volunteers.

The social circumstances that surrounded the 1625 Bahian expedition, subsequently known as the “journey of the vassals,” revealed how far the war in Brazil had progressed in the imperial outlook of the Iberian powers. “The last great enterprise in the Iberian world in which the traditional feudal obligations and military values of the nobility were effectively mobilised by the crown,” in the words of Stuart Schwartz,Footnote 76 became a political hallmark, a symbol of an elusive collaboration between Portuguese, Castilians and Neapolitans that immediately prompted Olivares’ plans for the unsuccessful Union of Arms. Filipe III kept his promises, yielding several royal grants, especially to the Portuguese high nobility that took part in the journey of the vassals.

The sheer size of the expedition—56 ships, 1,185 guns, and 12,463 troops—proved Madrid’s commitment to the defence of Brazil. But the deployment of what was to that time the largest naval force ever to cross the Atlantic also testifies to the drastic change in the status of the New World as a battleground and a space in which to enhance one’s reputation. Despite all the military failures in Pernambuco during 1630s, that status, apparently, did not decay in the following years. Since the commendable nature of the battlefield was essentially related to the Dutch, its political status, highly favourable for military services, would be preserved as long as the “heretic” Dutch remained there. In 1640, António Vieira wrote about the significance of the war in America: “No services Your Majesty pays with more liberal hand than those of Brazil.”Footnote 77 The problem that he had identified was related to the “dispatch,” to the inner workings of the bureaucratic expedient. According to Vieira, “the valiant get the wounds and the fortunate the prizes.” The Jesuit was returning to the theme of justice so often resorted to by Portuguese secessionists.

Previously seen as a less than dignifying field of battle, the New World became a place for extraordinary military deeds that the king could not ignore. Francisco de Brito Freire even contended that the New World engagements were more significant than the celebrated combats in Flanders.Footnote 78 In this respect, the type of war was of little consequence, despite the undeniable preference for Old World military orthodoxy. In Brazil, but also in Angola, there was little room for orchestrated battle movements (developed since the sixteenth century), which, according to several sources,Footnote 79 were largely unknown to the majority of the Portuguese anyway.

The war in America was carried out not only by Iberians (Portuguese and, until Portugal’s secession from the union, Castilians) and Neapolitans, all professional soldiers, but also by Indians and black Africans. In 1648, 650 of the 3,550-strong Pernambucan army were Blacks and Indians—the famous units of Henrique Dias and Camarão.Footnote 80 The Portuguese army that recovered Maranhão from the Dutch in 1644 comprised mostly of Indians: 3,000 out of 3,500 men.Footnote 81 When Salvador Correia de Sá retook Luanda in 1648, he had around 2,000 men, “people and infantry personnel trained in the frontiers in the wars of Portugal and in the campaigns of Pernambuco.”Footnote 82 But he also counted on the help of black soldiers spared by local African chieftains.Footnote 83 This meant that the Indians and the Blacks were also able to procure satisfaction for their martial bravery in what Charles Boxer considered ought to be called the First World War.Footnote 84 Born to slaves in Pernambuco, the famous Henrique Dias, who helped the Portuguese against the Dutch, is a good example. Although the Habsburgs dismissed his first request—the Mesa da Consciência (which usually made the necessary background checks) considered his demand contemptibleFootnote 85 —he later was successful with the Bragança. He was also successful in his attempt to obtain a royal sanction for the proclamations that had conceded freedom to slaves previously incorporated in the Portuguese forces. (the slave-owners were unwilling to do so.)Footnote 86

The attitude of the Portuguese towards the Dutch was clearly marked by conflicting sentiments. On the one hand, they displayed a visceral religious hatred, which lead them to say that the “Dutch … are only good to be burned as inveterate heretics.”Footnote 87 Yet, on the other hand, they could not disguise an admiration for their enemies’ achievements and military skill. For example, it was with unconcealed compliments that Francisco Manuel de Melo described the fortification of Recife. To him, “everything [was] regular, perfect and great.”Footnote 88 The same author also praised the abilities of soldiers besieged in Recife in 1654. Sometimes their admiration went even further, entering into the realm of aesthetic valorisation of their enemies. According to Charles Boxer, the Portuguese, who were certainly malnourished, commented with jealousy on the masculine bodies of Germans, French, British, and Scandinavian employed by the Dutch West India Company that tumbled onto the tropical battlefields. This certainly happened in an account written by one of the Portuguese defenders of siege of Bahia in 1638, which Boxer reproduced: “We counted their dead when we transport them—327 of the most perfect men that one can ever have seen; they seemed giants and definitely were the flower of the Dutch Army.”Footnote 89

The fight against the Dutch was perceived as an extraordinary endeavour, so much so that the Portuguese used it as a tool for their international rehabilitation after the controversial deposition of Philip III, particularly with the papacy. To Francisco Manuel de Melo, while others were losing ground to the “heretics” in Europe, they were recovering lost lands in the New World. The transcription below shows that the war with the ‘heretics’ was not simply an Old World issue; instead it was conceived of from an imperial perspective, according to which the American religious restoration was as valued as the European setbacks: “What pleases Portugal … is that Rome knows that, at the same time, a more favoured Catholic Prince, is handing over Provinces and Temples to the enemies of the Church; [while] the Vassals of the Portuguese King (although less favoured by the Supreme Pontiff) are freeing other Provinces and clearing other Temples from the heretical yoke and corruption, offering them to the obedience of the Apostolic See.”Footnote 90

The improving reputation of the South Atlantic battlefields and the financial and symbolic resources that were consequentially poured into them explains the successful mobilization of men, but does not explain their constant back and forth. It would be the Portuguese secession from the Habsburg Monarchy that added a reason to return to Portugal without the fear of being unemployed. The new and fragile Bragança dynasty, which inherited an empire globally harassed, also found itself threatened in the Iberian frontiers by the troops of the deposed king. The struggle against the Dutch in Brazil and Africa, temporarily suspended, was officially resumed in 1645 and maintained its prominent place in a changing imperial imagination, which focussed increasingly on the Atlantic, as several publications about the Dutch war show.Footnote 91 At the same time, Lisbon had become increasingly dependent on Atlantic trade since the Estado da Índia, the Asian thalassocracy, was clearly falling behind under pressure from the Dutch and English.Footnote 92 However, in the Old World, the war was no longer viewed as a distant event that had taken place in rather remote although prestigious places like Flanders, to where Madrid had diverted men who presumably were needed in the Portuguese empire, at least according to the aforementioned claim of João Pinto Ribeiro.Footnote 93 Now, to the dismay of the Portuguese government, the enemy was literally at the gates. And since the risk had a direct relation to the reward, the Portuguese frontier also became a space to enhance military reputations and to pursue social advancement.

As with the Dutch, a prestigious symbolism attached to the war with Spain. This is particularly evident in an insightful letter that the Governor General Francisco Barreto de Meneses sent to Pedro de Melo in 1662, regarding his nomination to the captaincy of Rio de Janeiro. Note that he was writing in a rather different context: while the Dutch had already been beaten, the Castilians were still exerting pressure on the Iberian frontier. According to the governor general, the New World was now incompatible with the social condition and military honour of Pedro de Melo. As we can see below, it was almost offensive to waste a good sword in a place where it was no longer needed:

I cannot help but feel your frustration; for in times when [you] should be continued in the Wars of the Realm, occupation of Fame, I saw you being buried in Brazil, scandal of His Majesty’s service. I am not inclined to murmur, but I will tell the truth to your Lordship, it is much to complain about the practice from those who banish your Lordship from [the realm], when [they] needed more your sword, your zeal, and your experience. Allow me the modesty of your Lordship to speak this way: what a shame, how different it is to beat Castilians than to have to deal with Mazombos [colonials].Footnote 94

By then the Iberian frontier, where the war would last until 1668, was the primary stage on which to perform the kind of military achievements that the Braganças could not ignore, especially because it was there that the Portuguese independence was directly threatened. In turn, Brazil, without the Dutch, defeated in 1654, was devalued as a battlefield (although the peace treaty was only ratified in 1669). For many men, and certainly for royal officials, it had become a distant space of tedious daily squabbles with few chances to show the kind of bravery that the king would feel compelled to reward. (Other opportunities would arise during the subsequent colonization process of Brazil.) Furthermore, the use of the term Mazombos for white Brazilians, which by then already had acquire derogatory connotations,Footnote 95 suggests that something else was changing in the way the European-born saw the American-born in the Portuguese Empire.

Everything was very different when there were Dutch to fight in the New World and in Africa, and Spaniards to fight in Europe, to whom we can also add the traditional fight against the Moors in North African waters. Those who served during the 1640s and 1650s benefited from unique circumstances in the early modern history of Portugal. They had favourable scenarios on both sides of the Atlantic. The perceptions about the military might of the enemies faced on both sides of the Atlantic and the imperial mindset that preserved overseas territories from immediate explicit colonial demotion led to an unbiased reward policy that valued military deeds performed in Europe as well as in the tropics. After all, they were both at risk.

To some degree, the monarchy’s Atlantic territories competed for military manpower. They competed for the military service of their subjects, regardless of their place of birth. And, although the war in Europe had always required more manpower, the Overseas Council certainly did its part to keep the American at strength. In 1647, during the preparation of an expeditionary force that Vila Pouca de Aguiar commanded to Brazil (of which he had been appointed governor general), the tribunal made a striking call to arms. John IV was advised to promise the same kinds of awards that had been guaranteed to the men that embarked in the 1625 journey of the vassals, which had retrieved Bahia for Madrid.Footnote 96 Such was the imperial imagination that some ministers would channel men to Brazil even when the mother country was under threat of being invaded.

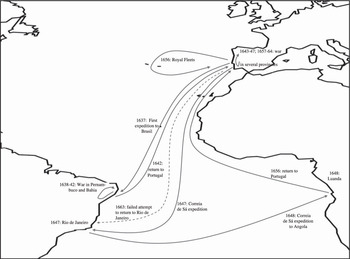

Admittedly dependent on overseas revenues, the crown did not make straightforward distinctions in military matters, so long as there was still the fear of losing Brazil to the Dutch or the mother country to the Spaniards. And that is why some men (though by no means all) circulated in an almost compulsive manner, as we can see below in the visual representations of the trajectories of João Machado de Freitas and Baltazar Vieira da Veiga, both contemporaries of Manuel de Almeida Falcão. Probably less prone to adopt a biased understanding of the Portuguese territories to begin with (when compared with top political agents who never left Europe), they must have sensed that the Portuguese fragile state, threatened by more powerful enemies, would fulfil their expectations wherever they chose to serve.

Atlantic Experience of Вaltazar Vieira da Veiga, 1640-166З

Atlantic Experience of João Machado de Freitas, 1637-1664

Crisscrossing the Ocean

The perception of João Machado de Freitas and Baltazar Vieira da Veiga, among others, becomes even clearer in the accounts they submitted to the crown to request promotions. Whether accurate or overblown, their accounts combined laudatory references to their participation in the Iberian battles and also in the main South Atlantic military campaigns. They did not establish any kind of symbolic hierarchy between the battle of Montijo (1644) and the re-conquest of Luanda (1648) or between the battle of Aronches (1653) and the victory in Recife (1654).

The Atlantic was conceived of as a wide space essentially free from mental or emotional prejudices with respect to different theatres of war. The highly-praised services in Alentejo, the main theatre of operations in the Portuguese war of secession, were a constant element in the accounts that the Overseas Council analysed, but the same happened to the services performed elsewhere in the empire. They even included military achievements that preceded the deposition of the Habsburgs, because these were also valued by the new dynasty. Participations in the journey of the vassals (1625), or in the successful defence of Salvador (1638), or in the naval expedition of the Count of Torre (1638) and Luís Barbalho Bezerra’s subsequent 400-league march through enemy territory were seen as assets that increased the bargaining power of these soldiers. Therefore, they were naturally added to the accounts that already alluded to services performed in later stages of the war, as was the case with the battles of Guararapes (1648) or with several skirmishes that pushed back the Dutch into the fortified walls of Recife.

As would be expected, patronage ties and networking appeared to play a major role in the circulation of men like Manuel de Almeida Falcão. In fact, the records show that several of them embarked in expeditions led by some of the most important political leaders of the period, whose recommendations largely shaped the imperial policies of the first Braganças. This was true in the case of the famous Salvador Correia de Sá, who planned and executed the re-conquest of Angola, but it was also the case with the group of the Count of Penaguião, significantly called the “warmongers,”Footnote 97 and which included António Teles da Silva (governor general of Brazil from 1642 to 1647) and António Pais Viegas (John IV’s private secretary).Footnote 98

Rather flexible administrative regulations, whose inner workings were kept in place until 1670s, made it easier for the governors who could appoint their men at least to certain positions, sometimes even before they set sail. In this regard, there are several allusions to governors who commissioned their protégés almost as soon they dropped anchor in American waters. That was certainly the case of Domingos Delgado, who sailed with count Vila Pouca de Aguiar to Bahia, in 1647, to the dismay of those who already served in that territory and who had seniority over Aguiar’s man.Footnote 99

References to Asian territories are surprisingly absent from these accounts. In this group, during the period covered by this study, there were not many really global trajectories like that of Sebastião Ferreira de Brito who embarked to India and Mombasa in the late 1620s, as a Habsburg subject. He returned to Europe in 1635 only to sail for Cacheu, in Guinea-Bissau, where his father had been appointed governor. The journey ended in shipwreck, whereupon he embarked once again, this time as part of the 1638 naval expedition to Brazil, where he would spend the next few years.Footnote 100 In my ongoing survey on the military officers of early modern Brazil, I have found only six men that served both in the Atlantic and in India between 1640 and 1680. Four of them applied for a post in Bahia and two in Rio de Janeiro (Sebastião Ferreira de Brito being one of them).Footnote 101 The prosopography based on application procedures (concursos) and other military papers submitted to the crown to apply for promotions suggest that there were two different areas of imperial circulation.Footnote 102 One, Atlantic based, included the mother country, America, and Africa; the other, was centred in the Indian Ocean. Apparently, those who left to serve in India tended to remain in the fast-receding Portuguese outposts in Asia, or, at most, would return to the mother country. An application procedure for a new regiment in the army of Alentejo, in 1645, reveals the levels of unparalleled cohesiveness and integration in the Portuguese Atlantic world—probably not unlike what Bernard Bailyn has detected in the northern Atlantic.Footnote 103 Seventeen of the forty-two men proposed as captains of infantry of that regiment had previously served in Brazil against the Protestants as soldiers or low-ranking officers; none had spent time in Asia.Footnote 104

The constant back and forth even provoked bureaucratic problems to the new Bragança dynasty. According to the administrative inner workings of the Portuguese political system, the services rendered were submitted to the king through different institutional channels that had their own zealously shielded territorial jurisdictions: while the services performed in the mother country needed to be forwarded to the Secretaria das Mercês (secretary of rewards), where they were later evaluated, the services performed overseas were submitted to the Overseas Council. However, at the beginning of 1660s several men had served on both sides of the Atlantic, which added a new point of disagreement to an already contentious system. After all, which institution should examine the merits of the papers sent by soldiers who had served in Portugal as well as abroad?

The crown apparently tried to redistribute those assignments on the basis of the amount of time served in each territory. That effort became very clear in a 1662 meeting of the Overseas Council. The ministers stated that “the petitioners should make their requests together and the services and actions that they had; and when the ones of the Realm were more than the ones of the Conquests they should be dispatched by the Secretary of Rewards, [and] when the ones of the Conquests were more than the ones of the Realm [the dispatch] belongs to this Council.”Footnote 105 This was also evidence that men with such a track record were a common sight in the Portuguese court, and that they were probably trying to use the institutional complexities of the political system to their advantage. Yet, this was not to last.

Changing Perceptions

The peace treaties with Spain in 1668, and with the United Provinces in 1669, put a formal end to this particular pattern of transatlantic movement. Portugal turned its back on Europe, which assured it several decades of permanent peace, broken only in 1704, at the beginning of the War of Spanish Succession. War certainly continued in the empire, notably in Angola and northeastern Brazil, but, for the most part, Portuguese rule was never thought to be in real danger, which affected the amount of resources allocated. Brazil lost its status as a battleground, and, apparently, not even the Guerra dos Bárbaros—the Barbarians’ War, a lengthy conflict (1683–1713) against several Amerindian tribes—could reclaim the lost symbolism.Footnote 106

Moreover, the kind of warfare that took place in Brazil against the so-called Tapuias, for example, demanded men accustomed to ambuscades and guerrilla tactics, which were also used against the Dutch in Brazil but largely unknown to Europeans. It is noteworthy that the indigenous revolts that lingered in Bahia and Rio Grande between the 1650s and 1690s were suppressed by the colonists of São Paulo, who had feeble ties, at best, to the mother country, and by their Indian allies.Footnote 107 On the other hand, in the mother country, the beginning of the eighteenth century witnessed a growing affection for European military orthodoxy, at least as far as the competitions for vacant positions were concerned. Men with less experience on European battlefields were less likely to be promoted. They were being snubbed for others with that kind of experience, even when the latter ones had seen less military action.Footnote 108 Ultimately, this biased approach would have even discouraged military personnel from embarking on an imperial career.

In the meantime, there were undisputable signs of political centralization, suggesting that the empire was gradually but undeniably being conceived of as a rigid top-down structure. Lisbon intruded more in the administration of its south Atlantic territories, seeking to curtail some of the more sensitive powers that the institutions of local representation had been assuming. For example, the intent to remove the American municipalities’ influence over the army suggests that the crown had stopped recognising the polycentric nature of the empire—the sense of near parity among territories—which had provided a rather favourable background for an unprejudiced migratory behaviour.

An assessment of the overseas ministers regarding the fiscal difficulties in Bahia, submitted to Peter II in 1676, encapsulates this changing perception. They said that such influence, solemnly conceded to the municipality in return for the aldermen’s involvement in tax collecting, had to be supressed.Footnote 109 According to the ministers, the aldermen should only be able to control the municipal taxes, in order to avoid what the council considered suspicious affinities between the troops and the local elites. To some extent, they were questioning the way a crucial feature of sovereignty was being shared. And this desired administrative submission entailed a change in the way the empire was perceived and in the way the crown rewarded their subjects. Significantly, a new regulation put in place in 1671 understandingly emphasized political and military service in the most threatened outposts of the Portuguese empire, notably Mazagan, the last Portuguese stronghold in North Africa.Footnote 110 To be sure, the overseas territories continued to provide plenty of opportunities for professional and social advancement, as well as for general enrichment. This was particularly true for Brazil, which became the focal point of the growing Portuguese emigration after the discovery of gold in Minas Gerais at the end of the seventeenth century. The overseas territories continued to attract the interest of low-ranking officers and other royal agents including clergymen and bureaucrats.Footnote 111 Yet, as far as military personnel were concerned, something had changed. As the Overseas Council records clearly show, those who sought to win a martial reputation continued to sail for the overseas territories, but the constant back and forth definitely ended in the 1660s. Their circulation pattern became simpler with far fewer transoceanic voyages. Leaving for Brazil, for example, generally meant staying there for the long run.

Final Remarks

This study does not mean to suggest that the Portuguese empire was deprived of ideologies, which would be an odd thing in the context of European expansion, as Giuseppe Marcocci recently noted.Footnote 112 But it emphasises the fact that, during the mid-seventeenth-century crisis, the Portuguese Atlantic world was perceived by many as a continuous space almost free of hierarchical understandings. I have tried to show that signs of this perception of an empire less centred on the mother country can be found even at the highest levels of Portuguese politics. Beyond this, there are overwhelming proofs of polycentrism, meaning that overseas dynamics owned at least as much to private initiative, often planned and executed in the colonies (sometimes not even immediately sponsored by the state), as to the crown’s colonial policies. The Pernambucan rebellion against the Dutch and the reconquest of Luanda clearly show that the “tail wags the dog” syndrome was a dominant feature of the Portuguese world, and one that can be identified in Portugal’s Asian territories as well.Footnote 113

This underlying perception about the Portuguese empire helped provide ideal conditions for the circulation of men engaged in Portuguese war efforts. Such conditions were greatly enhanced by the valorisation of Brazil as a battleground following the Dutch invasions of 1624 and 1630, and by the beginning of hostilities against Spain in 1641. Soldiers’ papers clearly show that they made no distinctions between fighting in the mother-country, against the Habsburgs, or in the south Atlantic in an all-out effort to defeat the “heretics.” For them, in this period, there were no all-important centres and unappealing peripheries. They were part of what looks like an essentially Atlantic circuit that included the mother country, America, and Africa. The Asian outposts are surprisingly, but definitely, not in their orbit. The ensuing political stabilization in Iberia and the Dutch defeat in the New World, with the inevitable devaluation of Brazil as a battleground, affected the incentive system and brought an end to the special kind of circulation treated here. An imperial career in the Atlantic world was no longer marked by a constant back and forth between the shores of the ocean.