“Freedom is our Religion!” proclaimed the enormous panels covering the soot and grime of a burned out building in the heart of downtown Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. The slogan was meant to encapsulate the fervently held ideals that spurred a popular uprising in 2013–2014 that forced the pro-Russian oligarchic president of Ukraine to flee in the night. The chains painted on each panel dynamically shatter as they meet, illustrating the release from colonial bondage that a new-found salvation in “our religion” has delivered. Written in English and Ukrainian, the panels were hung by the city administration prior to Kyiv hosting the televised Eurovision song contest in May 2017 (image 1). They remained for over a year until the building was fully renovated. Many that I spoke with explained the expression of the secular value of “freedom” in terms of “our religion” to indicate shared moral convictions. These panels are one of the many ways religion and politics interpenetrate in public space. The solidarity-producing tone of the panels metaphorically uses religion to articulate a collective sense of self. Simultaneously, the panels mute the fact that the uprising ended with over one hundred people shot dead in the streets and was followed by the loss of the coveted Crimean Peninsula and an undeclared war with Russia that has taken the lives of over thirteen thousand civilians and produced over two million refugees.Footnote 1

Image 1. Panels covering a building that burned during the Maidan protests of 2013–2014 in the capital Kyiv.

Although it evokes religion, this slogan is clearly a political statement. If read literally in a religious register, the meaning would be blasphemous. God, Jesus, the saints, and other biblical and institutionally recognized elements constitute religion, not secular political values. Yet, state and city authorities use religion to comment on recent political events, such as the Maidan protests, and offer a vision of the future as symbolized by breaking chains evoking an end to colonialism. Mobilizing the term “religion” in this way underscores the political and personal importance of the concept in popular consciousness.

With good reason, most scholarship on religion has focused on groups that influence the agendas of key social and political institutions. Yet, might there be other ways in which religion is influential when it is simply present? Might something amorphously called “our religion” wield political power by pervasively penetrating public and intimate spheres to such an extent that it becomes akin to second nature, allowing it to elude recognition, let alone critique? Rather than focusing on the ways religion challenges the secular, I suggest that religion can also quietly integrate into public space by accommodating itself to the secular, as these panels do. The visual and verbal articulation of key nationalizing political goals in terms of “our religion” allows religious institutions to exercise significant, yet often unexamined influence, even over non-believers, by informing attachments to place, political attitudes, and by extension, to the subjectivities of the citizens who live in those places.

Not all religious groups, however, are allowed to be present in public space to the same degree and command the same powerful, uncontested proclamation of “our” ideals. Historically dominant confessions can hide in plain sight even as they retain an authoritative and audible voice on a variety of social and foreign policy initiatives. The voices of other religious groups, in contrast, are often pressured to remain silent and their heightened visibility makes them subject to greater scrutiny. Just as whiteness in America is not always recognized as a racial category because it positions itself as unmarked and yet speaks with a forceful voice, the normative power and privilege of historically dominant faith traditions in states that claim to be secular often go unexamined and, by extension, unchecked.Footnote 2

Political positions can be announced from the scaffolding of burned-out buildings in the capital in terms of “our religion” precisely because a single, dominant faith tradition is recognized as culturally embedded. In Ukraine the ongoing, unchallenged acceptance of a public presence for religion is supported by a plethora of spiritualized practices that are place-based. This has fostered an affective atmosphere of religiosity, which informs inclinations to understand individual experiences and even political episodes in otherworldly terms. Religious institutions validate and endorse these interpretations to varying degrees. In doing so, they remain present in the lives of individuals who might otherwise be indifferent or even hostile to organized religion and this further naturalizes and renders normative the presence of religion in public space. This presence can be a form of power for religious institutions, and even for secular governing authorities, because the ability to predictably provoke certain emotions prompting specific actions and reactions makes religiosity an expedient political resource.

This article analyzes how an affective atmosphere of religiosity can be created and made politically useful. The spaces in between institutional religion and individual, ritualized behaviors as people go about their everyday lives can become sites that foster such an atmosphere. In some Orthodox Christian countries, a “place animated with prayer” (namolene mistse/namolennoe mesto) is said to be filled with energy that links individuals to others and to otherworldly powers. This designation allows non-doctrinal practices, non-clerical forms of authority, and non-institutional sacred sites to develop. Orienting religious practices to such sites circumvents anticipated coercion from clergy and institutions alike, but retains the shared understandings, emotional involvement, and attachments to places these vernacular religious practices breed.

I offer analyses of two such sites in Ukraine, a church and its surroundings and a large monasterial complex, and the plethora of practices people have developed to tap into the energy that resides in these places to make a change in their lives. Institutionally, these sites are affiliated with the Russian Orthodox Church, a linchpin in the colonial configuration that tethers Ukraine to Russia and keeps the country in a Eurasian geopolitical realm by hampering its drift into the orbit of the EU. It is precisely this colonial status that the uprising and armed conflict in eastern Ukraine seek to end (Fylypovych and Horkusha Reference Fylypovych and Horkusha2014; Hordeev Reference Hordeev2014; Finberg and Holovach Reference Finberg and Holovach2016; Kravchuk and Bremer Reference Krawchuk and Bremer2016).

The undeclared Russian-Ukrainian war, which has entered its fifth year, does not stop Ukrainians from attempting to utilize the powerful energy of these sites in spite of their affiliation with the Russian Orthodox Church. Some use their allegiance to these places to assert a claim for Ukrainian possession, thereby buttressing the nationalizing project of a beleaguered and corrupt Ukrainian state. For others, the meaningfulness of their experiences at these places prompts them to remain empathetic to the ongoing presence of the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine and respectful of the authority of the Moscow Patriarch far beyond Russian borders.

These starkly different views tend to boil down to assessments of which position promotes the “good” nationalism. Is the impulse to use religion to craft a sense of nationality to reinforce Ukrainian independence laudable? Or, should one respect the historical developments that have placed Ukraine within larger ecclesiastical and political units? Places animated with prayer capture these tensions by displaying “public feelings that begin and end in broad circulation, but they're also the stuff that seemingly intimate lives are made of,” as Kathleen Stewart has written (Reference Stewart2007: 2).

Places animated with prayer illustrate the advantages a historically and culturally dominant faith tradition has to be present in public space and to become embedded in semiotic ideologies that make places out of spaces and create attachments to them as well. These places and the practices they engender contribute to an affective atmosphere of religiosity. Such forms of vernacular religiosity can become a potential political resource because an affective atmosphere of religiosity is capable of shaping people's inclinations and can spark action driven by political and ethical judgments (Stephens Reference Stephens2015: 4). Even extra-institutional forms of religiosity can be seduced into serving a trinity of church-nation-state by articulating desired or actual political formations of nationhood, statehood, and ecclesiastical jurisdiction. This makes an affective atmosphere of religiosity an essential first step in the creation of religious nationalism or a confessional state, and this is why it merits our attention.

Yael Navaro has written, “It is only through fieldwork that unexpected frames for the study of affect could possibly emerge, inspiring conceptualizations that carry us beyond now well-established theoretical patrilines” (Reference Navaro2017: 213). Indeed, through participation and observation of encounters at places animated with prayer I realized the importance of these vernacular practices for creating and sustaining an affective atmosphere of religiosity. I have conducted ethnographic research in Ukraine since 1990 and on religion since 1997. The ethnographic material presented here was gathered in the Spring of 2017 in two locations: a church that is considered the place most animated with prayer in Kharkiv, a Russian-speaking city in eastern Ukraine in close proximity to the Russian border, and a large monasterial complex in western Ukraine.Footnote 3 Both are currently affiliated with the Russian Orthodox Church. As a Russian-speaking city, Kharkiv currently acts as a “fence” containing the armed conflict, but it has the potential to be a “bridge,” reconnecting zones. Therein lies its strategic value in an undeclared, albeit omnipresent war. The monastery, on the other hand, is in an overwhelmingly Ukrainian-speaking western region annexed to the USSR during World War II. Most there are strong proponents of Ukrainian sovereignty and a pro-European political orientation. Despite these historical and cultural differences, because some of the same people frequent both sites, many practices at these places animated with prayer are shared.

FROM AMBIANCE TO AN AFFECTIVE ATMOSPHERE

In analyzing the sources of an affective atmosphere of religiosity, I take inspiration from Matthew Engelke's concept of “ambient faith.” Engelke illustrates how members of the non-denominational Bible Society of England and Wales strive to produce what he calls “ambient faith,” meaning a Christian ambiance to everyday life (Reference Engelke2012). This echoes Charles Hirschkind's study of how cassette sermons inform the soundscape of markets and street life in Cairo and create a particular “sensory environment” that permeates public and private spheres and forges an Islamic “counterpublic” (Reference Hirschkind2006: 125). In a similar vein, the Bible Society deliberately attempts to infuse worldly contexts, such as shopping malls and coffeehouses, with semiotic markers that evoke Christianity to gently alter the sensorium of the public sphere as part of an effort to change the consciousness of individuals who circulate in that space (Engelke Reference Engelke2012: 156). Their ultimate goal is to produce an ambient faith in the doctrines and teachings of Christianity as recorded in the Bible. The advantages of being the historically and culturally dominant faith group are readily apparent. Would Muslims, or any other “outside” group, be allowed to introduce their religious symbolism into public space if they had similar goals? Would they have even asked?

However, the results of the Bible Society's campaigns have been negligible. Their attempts to publicly display angels as identifiable Christian symbols during Christmastime were blocked by government officials, who anticipated their constituents’ condemnation. The only symbols allowed were so highly abstract that most residents read them in a secular register or simply ignored them (Engelke Reference Engelke2013: 49–50).

Why do the Bible Society's efforts in England to create an ambient faith in public space fail, while it is possible for Ukrainian state officials to make public and uncontroversial assertions of “our religion” in the heart of the capital? Both England and Ukraine embrace secularism as a governing principle to manage pluralism, and both have a single historically and culturally dominant faith tradition. My goal is not to widen the spectrum of ethnographic particularism with yet another case study of religious-secular tensions. Rather, thinking comparatively can add to our understanding of how a public religion can be fashioned from meaningful experiences of an unseen realm and become a political resource when religion permeates public space.

The juxtaposition of Orthodox Ukraine and Anglican England is broadly illustrative of conditions of secular modernity across Europe. Many European countries have a single religious tradition that coincides with state borders. Yet, state-churches in Europe have exerted varied levels of influence on politics, and this has unevenly shaped the de-privatization of religion across the continent (Casanova Reference Casanova1994; Asad Reference Asad, Scott and Hirschkind2006: 207–9). In countries with a predominantly Orthodox population, a sense of national religion is fundamentally integrated into political power structures, concepts of state sovereignty, and the contours of nationhood, giving it a pronounced territorial dimension.Footnote 4 Embedding Orthodoxy in politically delineated spaces of nationhood gives it an ethnic cast and impedes its portability, compared to other Christian faiths that have creeds and modes of missionizing that can be inserted in almost any context.Footnote 5 The sharp differentiation of political and religious spheres, which characterizes the post-Enlightenment normative version of modern governance, is absent in Ukraine and much of Eastern Europe, leaving the ideal of a national Church serving citizens visibly interwoven into the social and political fabric.

Many factors have contributed to the evolving presence of an affective atmosphere of religiosity, but the plethora of individual devotional practices is key among them. On the eve of the Russian Revolution, Orthodox practice had fractured into “intensely particularistic” and “kaleidoscopic variations” on informal practices (Freeze Reference Freeze, Ransel and Burbank1998: 213).Footnote 6 Symbiotic to institutional authority for validation, these vernacular practices made the implementation of secularism as a political principle in the Soviet Union incomplete at best (Luehrmann Reference Luehrmann2011: 6–12; Wanner Reference Wanner2012: 7–23; Smolkin Reference Smolkin2018: 31–45). To block the legible practice of religion in public, Soviet leaders were obliged to dynamite monasteries and cathedrals, monitor cemeteries, execute clergy, and teach atheism. This occurred even as the Soviet state developed its own sacred sites, eschatology, political rituals, and cult of the dead, blurring the lines delineating “the religious” from “the secular” as modes of being and governing (Halfin Reference Halfin2000; Etkind Reference Etkind2013; Bernstein Reference Bernstein2015; Slezkine Reference Slezkine2017). Believers arrested for visibly practicing religion were usually considered political prisoners. This is why, especially in the 1960s, embracing religion was a means for believers and secular intelligentsia alike to express anti-Soviet sentiment.

The collapse of the Soviet Union coincided with a religious revival and orchestrated attempts at nation-building across the former USSR. This sharpened the politicization of religion in Ukraine even as it made the presence of religiosity more pervasive. Religious symbolism began to be fundamentally integrated into monuments and other renditions of the Ukrainian nation. The Holodomor, or Famine of 1932–1933, became a defining event in the newly crafted Ukrainian national narrative. Its monument is strategically placed before an illustrious monastery that was destroyed by Soviet authorities and reconstructed by the Ukrainian state (image 2). In this way, monasteries and other religious buildings provide an auspicious means to quietly harness religion for political purposes. The buildings themselves define and relate political spaces to one another, revealing the evolving place of religion in public space in a secular, pluralist society.

Image 2. Monument to the Ukrainian Famine of 1932–1933 (Holodomor), during which over three million Ukrainians died. The monument was erected in front of St. Michael's Monastery, which was destroyed by Stalin in the 1930s, rebuilt, and reopened in 1999 under the jurisdiction of the Orthodox Church affiliated with the Kyiv, not Moscow, Patriarchate.

ANTICLERICALISM AND INSTITUTIONAL DISAFFECTION

Using metrics of belief and institutional participation, as is common to measure religiosity in predominantly Christian societies, many scholars have concluded that Eastern Slavs are “nominally Orthodox.” Others have found inspiration in Grace Davie's succinct depiction of the English as “believing without belonging.” Jeanne Kormina (Reference Kormina, Hann and Goltz2010: 280) suggests that “belonging without believing” is more appropriate for Russians because they are part of a “church of the unchurched” (Kormina and Luehrmann Reference Kormina and Luehrmann2017). Tobias Köllner (Reference Köllner2012) characterizes Russians as “practicing without belonging,” whereas Julie McBrien (Reference McBrien2017) finds that “belonging” in Kyrgyzstan can morph into “believing.” “Minimal religion” is Mikhail Epstein's term to depict the Russian blending of mysticism, theosophy, “faith pure and simple,” and estrangement from religious institutions (Reference Epstein, Epstein, Genis and Vladiv-Glover1999: 378). These tensions between practice and belief and defining what one belongs to are reflected in the fact that, while conducting research in Ukraine, I rarely use the word “religion” and seldom end up at church. Many I have spoken with deny that they are religiously observant. Indeed, few enter a church, and fewer still do so for the purposes of attending a liturgy. Most do not know basic doctrines, such as the Ten Commandments, or participate in formal rituals, such as communion. Yet, when I see them very actively practicing their faith in pervasive and public ways and note the enormous political influence religious institutions wield, I find nothing minimal or nominal about it. Unrelenting criticism and disparagement of religious institutions aside, a mere 6 percent of Ukrainians claim to be nonbelievers, even though only 12 percent attend church with any regularity.Footnote 7 People indeed believe, but they do not always believe in religion, and they practice to belong, but not always to a church.

Their allegiance is to a faith tradition, not a specific institutional structure, and this shapes practice in decisive ways. The Russian word zakhozhane, usually rendered as “casual believers,” comes from the verb zakhodit’, meaning to “drop in.” Casual believers “drop in” to church to light a candle or pray before an icon or relic, but not to participate in a liturgy. There is no Ukrainian equivalent of this term. Prykhyl'nyky, or “sympathizers,” is the Ukrainian word to describe equally episodic forms of practice but with the important caveat that prykhyl'nyky connotes emotionally induced, ongoing commitment. Another phrase used in both languages is “atheists with traditions.” Those who so self-describe acknowledge meaningful forms of religious practice along with a secular worldview. Casual believers, sympathizers, and atheists with traditions practice religious rituals as a form of self-help, in response to the beat of cultural and political rhythms, or out of a desire for cultural belonging, but they do it on their own terms.

Places animated with prayer suit them because they simultaneously accommodate a guarded distance and an active attachment, a refusal to be coerced and yet the desire to belong. At places animated with prayer, there is little discrediting of religion, even as individuals seek to escape its institutional confines. Such religiosity is a means to overcome institutional disaffection and suspicion of clergy while capitalizing on the validation and authentication of sacred sites they offer. Places animated with prayer reveal the extent to which transformative practices associated with Orthodoxy are place-based. Place, not clergy or the religious institutions themselves, is the ultimate mediator and source of power. Place-making is a cultural mechanism by which everyday lived experiences can breed attachments and feelings of belonging, which has the potential to escalate into political inclinations and even political attitudes and action.

Orthodoxy is elastic and porous enough to accommodate nonbelievers, doubters, and critics because of its historic conceptualization of an organic assemblage unifying church-nation-state. This forms the basis of a religious identity that is understood to be inherited, eternal, and transcendent. In other words, regardless of whether or how one believes or practices, any East Slav can claim an Orthodox identity.Footnote 8 Although there are multiple Orthodox jurisdictions in Ukraine, over one-third of the population refuses to acknowledge allegiance to any single institution, preferring to identify as “just Orthodox” (23 percent) or simply a “believer” (12 percent).Footnote 9 This is similar to the rise of the “nones” in the United States, who skirt an allegiance to a particular denomination and claim to be “spiritual but not religious.” Here I focus on “sympathizers” and “casual believers” because they constitute “swing voters.” They are neither disengaged nor involved. They could be indifferent enough to stay at home when religious conflicts flare or politically mobilized enough to decisively force an answer to the vital question: whose places animated with prayer are these, anyway?

AN AFFECTIVE ATMOSPHERE OF RELIGIOSITY

Teresa Brennan begins her study of affect by asking, if there is anyone who has not, at least once, walked into a room and “felt the atmosphere.” (Reference Brennan2004: 1). She could have just as easily asked if there is anyone who, after arriving in another country, has not “felt the atmosphere.” An atmosphere distinguishes one place from another by uniting material and spatial experiences with the sensual and the affective.Footnote 10 When an atmosphere is not just felt, but, as Brennan says, begins “getting into the individual” and to transmit the feelings and inclinations of people who circulate in those spaces, then it has become affective. I will analyze how an affective atmosphere forms before addressing how it can become politically useful.

When I claim places animated with prayer contribute to an affective atmosphere of religiosity, I mean to signal the experiences at these sites are immanent (mediated through the material) and transcendent (connect an individual to an otherworldly realm). Atmosphere is borne of materiality, which becomes part of a sensory experience understood as religious. Material objects and the practices they engender make places animated with prayer spaces of intensity. Such places do not merely stir emotion; they provoke “visceral shifts in the background habits and postures of a body” (Anderson Reference Anderson2006: 737). When people circulate in affectively charged places and recognize the import of the experiences that occur there by incorporating underlying assumptions about those places to guide thought and behavior, then the totality of these experiences can produce an affective atmosphere. Such places constitute “moody force fields” that make collective publics (Stephens Reference Stephens2015: 2).

Two key factors explain why an atmosphere of religiosity emerges in Ukraine and not in other societies with a historically and culturally dominant faith tradition, and why it becomes affective. First, I emphasize religiosity, and not religion or faith per se, which is what Engelke's Bible Society tries to advance. This religiosity includes vernacular religious practices, born of institutional disaffection and anticlericalism, that are symbiotic to institutionalized religion because they exist between institutional confines and individual improvisation. Ambient faith, which the Bible Society tries to foster, centers on shared beliefs that draw on textual and clerical authority upheld by an institution. The work of learning and applying biblical teachings is difficult and very different from the emotive, embodied practices found at places animated with prayer.Footnote 11 These practices thrive because they do not need to form a community or make moral judgments, although they often do. They do not require institutional affirmation, although they benefit from it. This gives these practices considerable flexibility, tenacity, and validity.

Second, rather than producing an ambiance to roll back secularism, as the Bible Society attempts to do (as do religious entities in other societies), an affective atmosphere of religiosity in Ukraine integrates secularism and institutional religion and does not challenge either (cf. Navaro-Yashin Reference Navaro-Yashin2002; Özyürek Reference Özyürek2006; Bowen Reference John2008; Engelke Reference Engelke2012). A braiding of individualized religiosity, institutional religion, and secular impulses into a symbiotic relationship of co-dependence characterizes practices at places animated with prayer. A form of “syncretic secularism” results, which simultaneously allows for processes of secularization and sacralization to unfold, by meshing seemingly opposed inclinations and desires in novel reconceptualizations of religiosity (Wanner Reference Wanner2014: 435). Obscuring distinctions between the religious and the political (rather than trying to reinforce them) renders secularism as a political principle much more malleable and keeps religious institutions present in the lives of non-believers (Asad Reference Asad1993: 25; Casanova Reference Casanova2009: 1051–52).

This means that it is not always the “dangerous passions” that religious zeal can ignite that is the most politically volatile, as Michael Billig's (Reference Billig1995) study of “banal nationalism” illustrates. Rather, the daily experience of circulating in an affective atmosphere of religiosity can forge attachments that prime people to act and react in certain predictable ways. An affective atmosphere of religiosity can render the fates and fortunes of religious institutions of vital importance, even to non-believers critical of the same institutions. The political utility of religiosity rests on the fact that it is something that is already integrated into public and private spaces, and unquestioningly so.

Recognizable semiotic forms must be read in a religious register to identify something as religious. This is what prompts certain practices that create and sustain an affective atmosphere of religiosity. To give a straightforward illustration, it has become quite common for people to cross themselves when they pass before a church. They do not do this when they walk by other buildings. The architectural and aesthetic elements of the church signal to the pedestrian that they are in the presence of a sacred space, a point of access to otherworldliness. Some people, having read these signs in a religious register (as opposed to historically, aesthetically, or ignoring them altogether), reproduce a gesture of piety to signal their acknowledgement of this social fact.

Affect-driven processes of sensing-thinking-acting are filtered through a semiotic ideology as people read and interpret signs. Webb Keane defines a semiotic ideology as “people's underlying assumptions about what signs are, what functions signs do or do not serve, and what consequences they might or might not produce” (Reference Keane2018a: 65). Semiotic ideologies engage sensory modalities, such as sound, smell, touch, and pain, in historically contingent ways to form presuppositions that provide the underpinnings of worldviews. Keane recalls an example familiar to anthropologists. E. E. Evans-Pritchard studied witchcraft among the Azande and noted that if a termite-ridden granary collapsed on a person sitting under it the cause of the collapse would be perfectly clear to them: termites had eaten the granary's wooden supports. But why it collapsed when that particular person was sitting under it is equally clear: witchcraft caused their misfortune (Reference Evans-Pritchard1985 [1937]: 22–23). A semiotic ideology mediates the connections between a sign vehicle (the collapse of the granary) and its object (suffering) to make meaning. In other contexts, bad luck, angry ancestors, or moral transgression would have been offered as explanations as to why a particular person was under the granary when it collapsed. Local, historically-specific underlying assumptions govern which signs are meaningful, how they function, and their consequences. “Ideology” signals that the consequences of reading these signs can result in political and moral judgements by presupposing divine, natural, or arbitrary provenance. The evolution from a mere presence of religious signs to an affective atmosphere of religiosity hinges on reading signs such that they relate transformative experiences to political and moral judgements, which, in turn, inspire actions and reactions.

FORGING ATTACHMENTS

Although the expression “place animated with prayer” (namolene mistse/namolennoe mesto) is widely known, it only came into common parlance after the collapse of the USSR. It is used to distinguish especially sacred, historic places from newer ones. Jeanne Kormina refers to such designations as a “creative process of inventing values and ascribing them to things and places” (Reference Kormina, Hann and Goltz2010: 277). Namolenist’, or prayerfulness, is a semiotic form that contributes to an affective atmosphere of religiosity and a certain sensory regime that “makes belief” (Meyer Reference Meyer2014: 214). I first heard this expression in 2008 at the same time a friend did when she was criticized for the church she chose for her son's baptism. She is not a religious person and simply chose an attractive, neighborhood church near her home in Kharkiv. Her friends said this church was not a place animated with prayer and therefore the protective power of the baptism was diminished. “Well, where would have been a better place?” I asked. “The Goldberg Church,” she responded. “They said this is the place most animated with prayer in Kharkiv.”

I began to inquire what a place animated with prayer is exactly and what makes a baptism at the Goldberg Church more effective than at another church. I was told that if people come to a particular place with their heartaches and hopes, they leave something of themselves behind, creating a special zone of “positive energy,” even “raging energy” (beshenaia energiia). The energy left behind by the faith and prayers of others can be felt as sensations. Powerful sensations can burgeon into transformative experiences that result in healing, relief, visions, removal of hardship, fulfilment of requests, and other miraculous feats. The very corporality of the experience such energy produces is taken as evidence of its truth. Places animated with prayer, such as the Goldberg Church, are “energized places where a connection to God exists,” and this, not the institution or a deity, is what makes for transformative experiences, including an especially protective baptism. Energy, or bio-energetika, with its blend of science and religiosity, is an illustration of “syncretic secularism.” Such forms of “scientific spirituality” that involve tangible manifestations of energy began to exert widespread appeal as a valuable resource during the “religious renaissance” that occurred after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 (Lindquist Reference Lindquist2005; Panchenko Reference Panchenko, Bowman and Valk2012; Golovneva and Shmidt Reference Golovneva and Shmidt2015; Darieva Reference Darieva, Darieva, Mühlfried and Tuite2018).

The ritualized, discursive act of praying has a sacralizing function. There is no defined sense as to how prayers should be performed or how many believers must pray before a place can be considered namolene, which introduces a pronounced element of indeterminacy to a very specific status. Such a designation becomes an “underlying assumption” of a semiotic ideology when enough people recognize, replicate, and interpret their transformative experiences as coming from the power of the energy believed to reside in these places. The designation puts in place an upward spiral as people anticipate and imitate the experience of energy and ascribe a transformative power to it. By doing so, they perpetuate the cycle of validating the energy's power and reaffirming the status of a place as “animated with prayer.”

Once certain places are recognized as carrying this energy, they serve a mediating role, conjuring up the presence of energy that is so sought after for its transformative power. For many, the experience of visceral sensations of an unseen realm, where the presence of specific people is felt, regardless of whether they are dead or alive, can be both calming and invigorating. Presence is relational and takes the here and now as a starting point. The problems that prompted a person to visit a place animated with prayer can suddenly seem surmountable against the vastness of an otherworldly realm. These experiences also introduce expansive dimensions of time. Feeling the energy from the depth of history and one's own ancestral roots in that particular place can deliver comfort and empowerment. The transformative power of this energy stems from the connection it makes to the place and to others who have come before and animated it. When experiences of energy are frequently replicated at a specific place, an informal consensus emerges that declares the place animated by the faith-based practices of prior generations, evoking the original meaning of religion as a binding, connecting force.

The meaning of the designation is specific, but the type of place is fairly open-ended, making for an unlimited potential for spatial enchantment. One of the signs associated with a place animated with prayer is a deep mythological vision of a holy past. This is often projected onto a site where a church or monastery now stands with the assumption that pre-Christians worshiped there too, deepening the deposit of devotional energy and marking the site as a “place of forces” (mistse syly/mesto sily) (Lesiv Reference Lesiv2013: 118; Golovneva and Shmidt Reference Golovneva and Shmidt2015). Part of the appeal of a place animated with prayer is that it demands little performative competence and no clerical intermediary (Panchenko Reference Panchenko, Bowman and Valk2012; Kormina and Luehrmann Reference Kormina and Luehrmann2017). There is no prescribed ritual that must be performed there. Anyone can partake by innovating their own ritualized behaviors to appeal to otherworldly forces who share the same space. Although places animated with prayer are sometimes natural spaces, such as springs or groves, if they are part of the built environment, they are frequently connected to an official religious institution. This means that official religious sites host a variety of worldly inspired, lay practices.

This reverses the dynamic the Bible Society pursues. They try to infuse “secular” spaces (shopping malls and coffee shops) with religious symbolism, which is a more ambitious project. In Europe the perils of classifying space as “secular” or “sacred” are heightened. Empty churches are increasingly converted into tourist attractions, concert halls, and conference centers. They still retain something of a sacred atmosphere even after being reframed as sites of cultural heritage. In contrast, many religious buildings during the Soviet period were repurposed for profane uses. The Goldberg Church in Kharkiv, for example, was turned into a warehouse from 1925 to 1941 before it was reopened during World War II. Declaring this church (and others) animated with prayer in a post-Soviet era is a rhetorical device to purify decades of profane use and neglect. It reestablishes reverence by emphasizing the sincere devotional practices of ancestors that occurred specifically in this place and induces forgetting of the decades of desecration.

THE GOLDBERG CHURCH

The Goldberg Church was built from 1907–1915 by a Jewish convert to Orthodoxy when he became the head of the merchants guild. Local lore has it that, in gratitude, he gave the church to the city as a gift. The church's actual name is Three Saints Church, but no one calls it that. Goldberg ran his paint and hardware business with two of his brothers, who also converted to Orthodoxy, perhaps explaining the official name. Not only the Church's provenance from Jewish converts, but also its aesthetic and architectural elements are read in such a way that it has earned the designation “animated with prayer” in the superlative.

As one enters the vestibule, floor to ceiling ornamentation of naive folk renditions of sunflowers, cherries, and strawberries greet the visitor and create an unusually playful atmosphere (image 3). Painted by a Russian artist who was brought in expressly to create a uniquely Ukrainian folk motif, the vestibule sets the stage for the bright light that streams down from the multitude of windows in the cupola into an open hall. The mysticism of some Orthodox churches is created by the fact that they tend to be shadowy places with minimal natural light, filled with smoke from candles, incense, and human breath. This church breaks with those atmospheric and architectural conventions. In addition to the light, there are no central pillars, which makes for a single open space that was considered quite a feat of construction at the time (image 4). By local standards, this church is not particularly old, a quality usually attributed to namolenist’. However, its choir is famous for medieval Byzantine chants. Music, like icons and architectural elements, are “sensational forms,” which, Birgit Meyer (Reference Meyer2014) argues, as shared religious aesthetics, mediate practices, patterns of feeling, and contribute to making religious subjects. Such sensational forms, of which there are a plethora in Orthodoxy, govern the engagement of bodies in certain practices that can create experiences, even transformative experiences, of feeling the presence of energy (Engelhardt Reference Engelhardt2014; Kellogg Reference Kellogg2017).When such sensational forms are read as religious and are in constant circulation, they promote an affective atmosphere of religiosity by appealing to the senses and by catering to an underlying assumption of lived space as enchanted.

Image 3. Vestibule of the Goldberg Church, the place most animated with prayer in Kharkiv.

Image 4. The Goldberg Church has an unusual atmosphere thanks to its open, bright central space.

Let us consider the myriad ways a place animated with prayer, such as the Goldberg Church, is experienced before we turn to how these experiences can be made politically relevant. Natalia is a “casual believer” to the extent that she “drops in” to this church on her own to light candles but does not attend services. She is aware that the church is associated with the Moscow Patriarchate, but this plays no role in her decision. She describes the atmosphere of the church as one of “peace” and “comfort” that transports her into a “state of calmness,” and this is what motivates her to come:

When you arrive in a namolennoe mesto, you realize right away that you are where you need to be. You feel a sense of comfort when you approach icons and feel God's grace. Such a sensation. Such calmness (spokoistvo). You arrive, you make a request, and you understand that there is an answer. This is why you become calm…. That's the kind of atmosphere that exists here … you feel some kind of awe and you just start to speak quietly.… In that atmosphere of calmness, you suddenly feel warm and you leave with these feelings. You just fall into that aura and you become calm. You feel there is some kind of protection around you and you gain strength from that.

She searches for her grandmother's energy at places animated with prayer because she believes that her grandmother is the source of the protective powers that have positively shaped her life. Although this could be considered a form of ancestor worship, it mirrors official church doctrine that acknowledges the ability of saints to intercede on behalf of the living. At forty-eight, Natalia has for twenty-six years been happily married, as were her sister and mother. Her grandmother was the only person she knew during the Soviet period who admitted to being a believer. She attributes her family's harmony to her grandmother's intervention through prayer when she was alive and the work of her spirit today, and she understands the sensations of energy she experiences at this namolene mistse as her presence. She comes anticipating and searching for these sensations, as part of a process of “inner sense cultivation” so germane to religion, and routinely experiences them (Luhrmann and Morgain Reference Luhrmann and Morgain2012: 363).

The affective atmosphere of such places, created by light, music, visual stimulation, and other sensational forms, sets in motion a mimetic faculty as people attempt to imitate the experience of restorative energy that has been described to them (Gebauer and Wulf Reference Gebauer, Wulf and Reneau1995: 26). Bodily sensations induced by the affective atmosphere confirm the existence of energies at places animated with prayer. In this way, the mimetic faculty predictably sets in motion the perceptual, sensational, and experiential affective flow in which sensations lead to thoughts and actions and culminate in experiences. When there is an informal consensus that experiences of energy at a particular place effectively fulfill requests and deliver desired transformation, the place is considered namolene. Ultimately, then, becoming a place animated with prayer rests on the human ability to imitate a sought-after experience. This reflects Michael Taussig's succinct definition of the mimetic faculty as “the nature that culture uses to create second nature” (Reference Taussig1993: xiii). It becomes “second nature” for visitors, such as Natalia, to both anticipate and experience the energy of the affective atmosphere as it circulates and “gets into the individual.”Footnote 12

Natalia enters the church with the expectation of experiencing certain sensations that will provide relief and otherwise make her feel calmer than when she entered. Using icons and candles, she has developed the ability to conjure up the felt presence of her grandmother. These experiences are increasingly filtered through a semiotic ideology that reaffirms an underlying assumption that some places are animated with otherworldly powers and situates such places within political borders. By repeatedly visiting this place animated with prayer, Natalia's connection and attachment deepens, not only to the dead who continue to positively influence her life but also to the Goldberg Church where these encounters occur. Dropping in to this church is not a political act for her. It carries purely personal benefits. However, precisely because her visits root her in this place and connect her to ancestors who were also rooted there, she could be made to care about the fate of this church. Her improvised and episodic, but nonetheless sincere, forms of religious practice are symbiotic to a religious institution that has become a pawn in geopolitical tensions, as we will see. This heightens the importance of supporting secular powers that can deliver continued access to these otherworldly powers.

AN ANIMATED NEIGHBORHOOD

The first time I visited the Goldberg Church I was with Viktoria, a historian of the city, and she wanted to introduce me to someone she thought I should know. Yurii is a literary scholar who has dedicated his professional life to promoting the writings of Yurii Shevelov, a linguist, essayist, and literary critic who lived in Kharkiv until he fled to the United States during World War II. Yurii's dedication to Shevelov reflects the sacred status of writers as beacons of truth, wisdom, and beauty and the pious devotion with which they are revered among members of the intelligentsia in this part of the world. His house, filled with handwritten manuscripts and books, amounts to a shrine to the writer's life. For him, the Goldberg Church is part of a semiotic ideology to the extent that it permeates his worldview and forms the bedrock of his “assumptions about the nature of the world, the kinds of beings that inhabit it, and the kinds of causes and effects with which they are involved” (Keane Reference Keane2018a: 67–68).

The Goldberg Church is in a neighborhood of small one-story homes without running water, encircled by high fences, and connected by a maze of dirt roads. When Yurii asked what brought us to this neighborhood, I explained that I wanted to see the most namolene mistse in all of Kharkiv. His grandfather had been a priest in the church, and many of the neighboring homes also belonged to clergy and are now inhabited by their descendants. For this reason, Yurii considers the entire neighborhood animated with prayer and he has no intention of ever leaving it. He recited the church's history in minute detail. When I mentioned that I found his account of great interest, he replied, “To some it is interesting, to others it is sad (summno).” The church and its sordid fate during the Soviet period represented both the zenith of human accomplishment and the nadir of human madness, Yurii insisted.

He is not a believer and voraciously criticizes the Orthodox Church, with special wrath reserved for the Moscow Patriarchate, of which the Goldberg Church is a part. This does not stop him from being a “sympathizer” and decorating his home with a variety of religious artifacts including icons, prayer beads, and embroidered cloths (image 5). For him, these objects are a sign of his cultural heritage and indicate that he is, as he put it, a “patriot of his country.” These religious objects are a material manifestation of a semiotic ideology that Yurii uses to express his political views and his devotion to promoting his cultural heritage, which centers on literature and religion.

Image 5. Domestic shrines that include religious objects, such as icons, prayer beads, and folk art, like this rushnyk, or embroidered cloth, are quite common in the homes of secular intelligentsia, who often appreciate religious artifacts for their aesthetic, cultural value and what they communicate about national allegiance.

Elayne Oliphant (Reference Oliphant2015) analyzes how the Catholic Church in France encourages art exhibits of religiously themed works in religious buildings, which position art as the form and religion as the content. The Church thereby retains a presence in public space, albeit not as religion but as “cultural heritage.” This brings the Church and non-believing public together in a shared place with a religious aura and history. Nonbelievers who might not enter a church might attend an art exhibit. This opens the possibility that aesthetic signs could be interpreted in a spiritualized register, as the Bible Society in England also recognized when it tried to place angels in public space at Christmastime. When a historically dominant religious tradition informs aesthetic sensibilities, it can strengthen attachments to the religious among non-believers by allowing them to appropriate and secularize religious objects as art, cultural heritage, or political statements. Yurii's religious artifacts trade on his underlying assumption of the organic integration of national identity and religiosity, giving a particular ideological meaning to these objects. When a certain faith tradition is a defining pillar of nationality and the institution that claims to be its protector is a political agent, promoting literature and displaying art can become vehicles to express political views that feed into religiously infused subjectivities.

Illustrating how the political and historical context can change the semiotic ideology through which religious objects as signs are perceived and experienced, recall that, motivated by communist ideology, the Soviet state vigorously tried to demystify the otherworldly powers of religious objects by claiming that they were mere art objects. Later, in the 1990s, both the Ukrainian and Russian governments, in an effort to silence right-wing extremists, sought to prohibit using religious signs and symbols to make political statements. More recently, however, both states have encouraged a nationalist reading of these religious signs and have become more tolerant of assertions of “our religion” to make political statements. This illustrates changing underlying assumptions as to what constitutes reverence, critique, and blasphemy.Footnote 13

Although Yurii is an atheist, he uses icons and other religious objects, like his beloved author, to express his ardent pro-Ukrainian political views in this highly Russified city on the edge of a war zone. In surveying the décor in his home, I was reminded of Stewart's observation, “Politics starts in the animated inhabitation of things, not way downstream in the various dreamboats and horror shows that get moving” (Reference Stewart2007: 15–16). These religious objects anchor his small home, with its clerical origins, in the dramatic history of the Soviet Union's promotion of militant atheism. They announce his allegiance to the Goldberg Church, even as he fiercely criticizes the Orthodox Church for its subservience to an imperial state, and his respect for his grandfather, even as he lambasts the clergy of today. These religious objects express political judgments about national allegiance and dissidence to state powers.

As I went to shake his hand before leaving, Yurii chastised me for standing over the doorway. A long-standing and widely observed custom has it that spirits lurk beneath the threshold and might surface if greetings of arrival or farewell are expressed there. Avoiding the threshold has become “second nature” for him even though he is a nonbeliever. He instinctively does it even when the custom trades on the ability of malevolent forces to inflict harm while hiding under a clerical home in a neighborhood animated with prayer.

The mimetic practice of not shaking hands over the doorway is common, as are many other such “folk” customs. They, too, contribute to an affective atmosphere of religiosity because they trade on underlying assumptions of animated places and unseen forces capable of transforming a person's life. They are not carriers of the political the same way as practices connected to institutional settings are. Those religious institutions are squarely situated in politically defined spaces and often have pronounced political agendas. Nonetheless, such semiotic forms of vernacular religiosity are part of a web of practices that draw on a worldview of a concatenation of otherworldly forces inhabiting the same space as humans. These practices have created second-nature otherworldly instincts in Yurii even as he insists on his own atheism. This is yet another way an affective atmosphere of religiosity is sustained.

TRAVELING TO AFFECTIVE PLACES

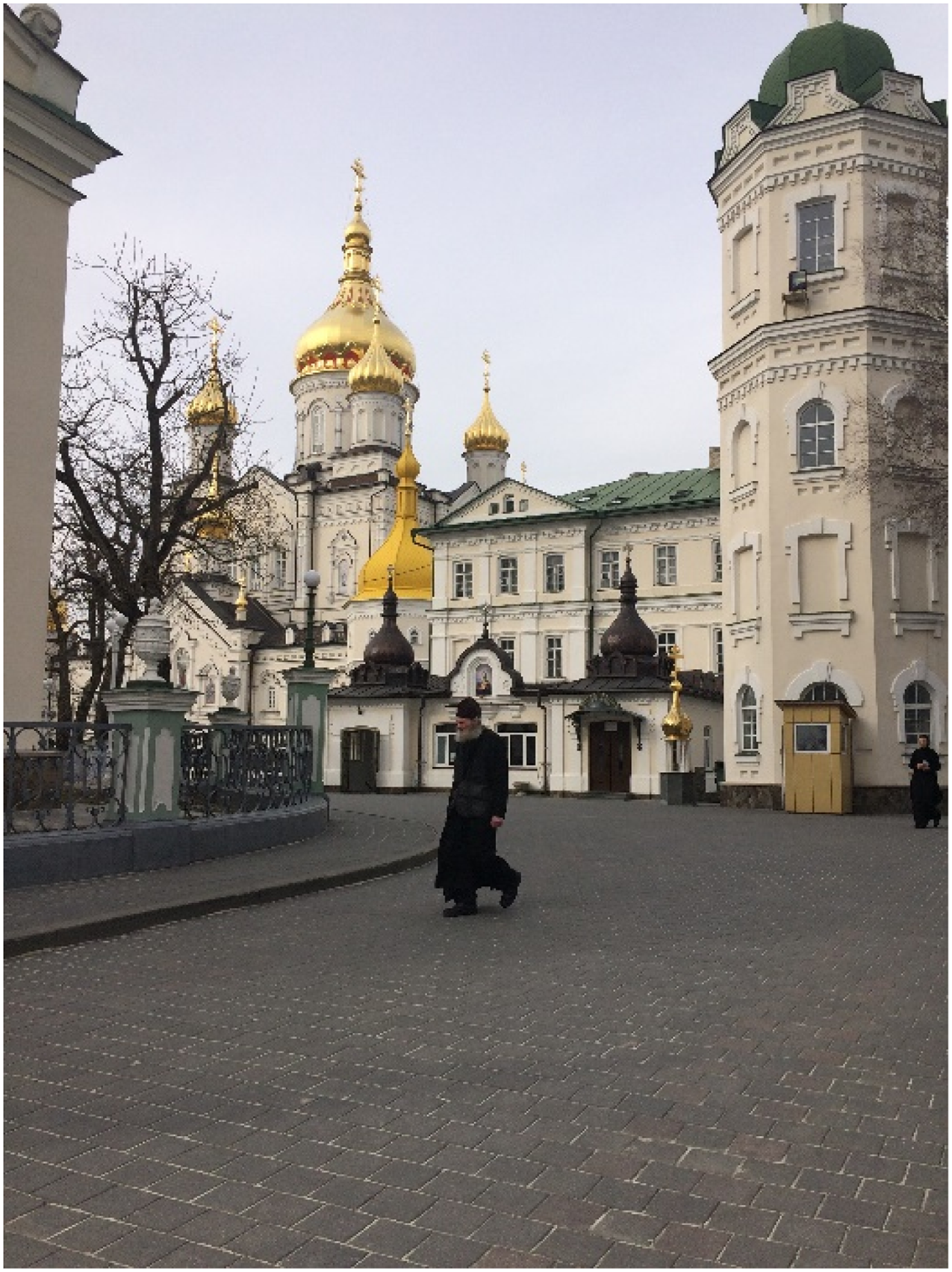

While “sympathizers” like Yurii and “casual believers” such as Natalia appeal to the powers of neighborhood places animated with prayer to advance political and personal goals, when people's needs are great many will set off for some of the most animated places in the Orthodox tradition: monasteries. A veritable religious tourism industry, sponsored by denominations, parishes, or purely commercial travel agencies, offers a mix of travel catering to pious devotion, self-help, vacationing voyeurism, and spa-like cleansing experiences for the deeply devout and curious alike. Before the war broke out, pilgrimages ignored political borders and transported Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians to shared sacred sites all over the former USSR and even around the world. Kormina characterizes this widespread form of religious practice as “nomadic religiosity” because it forms “temporary communities of practice” (Reference Kormina and Luehrmann2018: 144). Orthodox clergy lament that so many prefer such travel to actually attending a liturgy. The war has remade this “nomadism” as travel from Ukraine to Russia has all but halted and movement in the other direction has significantly fallen off. However, this has not changed the number of pilgrims to Pochaiv, one of the five important monasteries for Eastern Slavs (image 6). Pochaiv is under the Moscow Patriarchate and located deep in western Ukraine, a region known for its nationalist leanings. The war has simply changed where the pilgrims come from: Russians and Belarusians might travel to Ukraine in far fewer numbers, but Ukrainians do not leave, so for the monastery it is business as usual.

Image 6. Pochaiv Monastery in western Ukraine.

In February 2017, I joined a pilgrimage group to Pochaiv to see how the connection to the Moscow Patriarchate, given the armed conflict in the east, might affect, if at all, enthusiasm for monastic visits. Its hotel has one thousand beds and it was booked over capacity on the winter days I was there. Pilgrimage agencies offer convenient, two-day trips that include visits to three monasteries with miracle working icons, a cemetery, and a sacred spring (images 7–9). The fee, equivalent to US$20, covers transportation, modest accommodation, and most meals. (Six years ago the price was less than one-third of that, so this seems expensive to most Ukrainians.) A text message instructed us to “meet at the tank.” An old Soviet war memorial featured wilted World War II-era weaponry, including a tank, and faded images of destroyed “hero cities.” As I headed toward the tank at 6:45 a.m., I could see in the distance a woman wearing a long black skirt and a scarf covering her head and hair, attire that was expected of women at monasteries. Her name was Valentyna and she distinguished herself from all the other participants in the pilgrimage group because she observes the fasts, regularly takes communion, and generally has reverence for the institution. This would be her fifth or sixth trip to Pochaiv; she could not remember exactly. She had also been to numerous other monasteries and was planning another pilgrimage for the following week. At sixty-three, she has time to travel. She recently retired from her “man's job,” as she called it, as an electrical engineer at a construction firm in Kharkiv. She is highly educated, speaks English, and has traveled extensively throughout Europe.

Image 7. Placing prayer requests for the dead at a cemetary along the way to the monastery.

Image 8. A seminarian leads a tour of the churches of Pochaiv Monastery in western Ukraine.

Image 9. The pilgrimage culminates in an immersion in a sacred spring. This is the gender-segregated, covered immersion area.

As we settled into a small van, just barely fitting all the bags, she peered out at me over her gold-rimmed glasses, with several gold teeth glimmering to match, and told me how she prefers to travel by herself. “Why don't you travel alone to Pochaiv then,” I asked. “Because to go alone would be tourism,” Valentyna responded. “You would travel about the monastery with people of different faiths for whom the monastery would have other meanings, probably as just a cultural and historic landmark.” She assumed, probably correctly, that, excepting myself, the others in the group, even those who had signed up through a travel agency, still wanted and perhaps even needed to experience the monastery's affective atmosphere. This is why they chose to form a group, something of a temporary group of shared need, and come to the monastery as pilgrims, not as tourists. The distinction, though, could be a fine one.

Their motivations for participating were divided. Half, I would say, were vacationing with a purpose, whereas the others came for redress. We were thirteen women and one man, he being the thirty-four-year-old son of one of the women. He was celebrating his birthday on this journey and the pilgrimage was a gift. At one point, his mother offered everyone wine and sweets in celebration. There was also a mother-daughter pair who had registered through a travel agency, and two well-heeled young women who were clearly friends. The latter wore fur coats, had perfectly manicured fingernails and designer handbags, and yet they showed up without skirts, scarves, or long shirts for bathing in the sacred spring. The tour guide, prepared for tourists who know little of monastic life, had an extra skirt, which meant that only one of the women was obliged to wrap a scarf around her legs as a makeshift skirt to be in keeping with the monastery's dress prescriptions for women. All six of these pilgrims reserved double rooms in the monastery hotel to enhance their bonding experiences, whereas everyone else slept in rooms that held upwards of ten beds each. This group was vacationing with a purpose—they wanted to take advantage of the “blessings” that a place animated with prayer could deliver, but they also wanted to enjoy themselves.

The other women had clearly come to find relief from some form of woe that had beset them. Many were in their late twenties or early thirties, an age where two types of difficulties can set in: either they have no partner, or their partner is problematic. Some want children and others want their children to be healthy. These women kept to themselves and were quiet to the point of being somber. Their need to feel the energy seemed more urgent. They were shouldering the gendered responsibility of caring for the well-being of their families. One of them, Zhanna, was on her third pilgrimage to Pochaiv. She came to pray for the health of her husband, who for three months prior had visited doctors to heal a hacking cough. She thought he had walking pneumonia, but no medicine seemed to help. One week earlier he had left for Israel to receive medical treatment and Zhanna left for Pochaiv to put in prayer requests for the monks and nuns to pray, with their learned piety, for his recovery. Each was doing their part to restore his health.

Once we arrived at the monastery, a seminarian gave us a tour (image 8). Aware that many people come to the monastery for its affective powers, he warned against expecting the “aura” or “magic” of the monastery to heal. He countered with appeals to turn off the television. He wanted us to read, go to adult Sunday school, and study the symbolism of the liturgy. Much like the Bible Society, he wanted us to learn. Orthodox church services are sung in Church Slavonic, a liturgical language, which, like a Latin mass, is incomprehensible to most. Although a sacred language is meant to be a vehicle to a religious experience, it frequently has the opposite effect. Knowledge, the seminarian countered, is the best insurance against boredom during long services. It would help us, he insisted, to retain a focus on the state of our eternal soul. How do we know we have a soul, he rhetorically asked? Because it hurts, the women answered in unison. Fully prepared for the response, he nodded in agreement. This, I understood, was the purpose of the trip: to reduce the pain of an aching soul, the reasons for which are as varied as there are visitors.

A pilgrimage is an efficient means to do so. A monastery offers many possibilities for accessing otherworldly powers through places and things to alleviate suffering. Pilgrims visit the various churches and chapels that dot the monastery grounds on their own and can, if they choose, participate in formal rituals such as confession, communion, and late night and crack of dawn liturgies. One can appeal to God, the saints, elders, monks, and ancestors using sacred spring water, holy water, miracle-working icons, relics, prayer requests, and candles. One can also purchase crosses, books, icons, and a plethora of other religious objects to take home, as well as bread, honey, tea, and other consumables made by the monks. Each of these material things mediates the religious experience by helping to generate a sense of presence by delivering, in this case, protective or healing energy (Engelke Reference Engelke2007; Meyer Reference Meyer2014).

Tetiana was one of the women who brought a fur coat but none of the other requisite clothing. Over the course of the two days, she purchased books on healing children and put in numerous prayer requests for good health and the dead. During each transaction (the cost is based on the number of names the monks are asked to pray for), a monk inquired: “Are they all Orthodox? Of the Moscow Patriarchate?” She was the only member of the group who responded that her family members were not believers, which meant she had to pay more. All others automatically responded in the affirmative. “Yes, they are all believers and yes, of course, they are of the Moscow Patriarchate.” Privately, however, many spoke differently. Zhanna emphatically told me that she goes to whichever church she wants, and that it was none of the monk's business.

Just as the monk seemed to have no difficulty asserting that this was the only True Orthodox Church, making the other Ukrainian Churches apostate schismatics in spiritual sin and error, the women lied straight to his face with no regret. They told him what he expected to hear so that he would give them what they wanted. This coarse transactionalism and duplicity is illustrative of consumerist attitudes toward spiritual consumption and the deep-seated mistrust and cynicism that fuels institutional disaffection. Such critical attitudes do not, however, diminish the desire for otherworldly help to solve problems in the here and now. Anticlericalism coexists with a recognition of the monks’ “pious erudition,” which makes their prayers more effective. Sometimes, this builds in a preference to rely on intermediaries, lay and monastic, to gather and deliver prayer requests (Kormina and Luehrmann Reference Kormina and Luehrmann2017). It can also inspire those in need to participate in temporary communities, such as this pilgrimage, as a forum preferable to membership in a parish. Pilgrimage reflects both the attraction of the monastery and monks as privileged places and peoples to access otherworldly energy as well as a means to live a “just Orthodox” commitment to a faith tradition. By not choosing a parish, and by extension a single denomination, there is no risk of receiving the kind of condemnation my friend did when she chose the “wrong” church in which to baptize her son.

OTHERWORLDLY POWERS OF THE LAND

This pilgrimage, like many others, culminated with the purifying experience of immersion in a sacred spring. This was the highlight of the trip and everyone cast aside the possibility of falling ill and participated, except for the pious pilgrim Valentyna and myself. The two of us simply could not make that leap of faith. The water in February was a near-freezing 4 degrees (34°F) and the surrounding snow and ice made it seem even colder. There were two options for immersion: a gender-segregated covered area or an open pool (images 9 and 10). Immersion was conducted under the guidance of Marina, the tour guide, who doubled as a lay expert on the ritual. After Tetiana, the woman who admitted that her family were non-believers, immersed herself in the spring, as promised by Marina, she felt a certain “lightness.” She said that she suddenly understood why christenings involve water. “At first,” she said, “the spirit was so heavy that I could hardly breathe. And then lightness. Marina said to me, ‘Do you see how light you feel? It is true! You have taken the bad out of yourself.’ I believe it. Maybe because I am the kind of person who believes things. I am not a skeptic. I accept this on faith.”

Image 10. This open immersion pool is connected to the sacred spring.

The sensations delivered by immersion in freezing waters at a sacred spring were enough to transform her self-perceptions and validate the trip. She had come on this pilgrimage with a goal in mind. Now that “the bad” had been removed, she could return to her daily life with that knowledge. In the bus back to Kyiv she was already speaking of her next trip to a sacred spring. Discussions focused on which monasteries are accessible given the roadblocks and checkpoints the war has imposed. For those unable to become “nomadic,” a public park in Kharkiv offers the possibility of an immersion experience, replete with iconostas, in a cross-shaped pool filled with spring water that “doctors” claim is the purest water in all of Kharkiv (image 11). The prominence of religious signs in a vernacular version of a religious ritual practiced in secular public space is uncontroversial. Precisely because such vernacular practices are meaningful, their ambient presence in the form of unmarked religiosity means that even a public park contributes to an affective atmosphere of religiosity.

Image 11. The Sarzhyn Yar public park in Kharkiv also offers access to bathing in a sacred spring.

Each time someone such as Tetiana, Zhanna, or Valentyna has a transformative experience at a place animated with prayer, they build an attachment to that place and to the imagined others whose faith made it animated to begin with. That attachment, in turn, breeds a will to keep that place accessible. When place-based forms of vernacular practice are politicized by political, cultural, and ecclesiastical leaders, an attachment to place can become territorial. Once place-based sensational forms are perceived and experienced through a semiotic ideology, leading to ethical or political judgments informing behavior, then the affective atmosphere of religiosity can become a political resource capable of mobilizing believers and non-believers alike. Given the meaningfulness of the transformative experiences that occur at these places, allegiances grow to the state powers that can secure otherworldly powers. Let us return to the question of whose places these are.

THE WORD EVERY UKRAINIAN KNOWS

Every Ukrainian knows the meaning of the Greek word tomos: it refers to a “tomos of autocephaly.” One of the issues currently exacerbating the armed conflict between Ukraine and Russia is the institutional configuration Orthodoxy should assume in Ukraine. The Russian Orthodox Church considers its canonical domain to be the historic territory of the Russian Empire and envisions itself as the unifier of the “Russian world” (russkii mir), meaning all Eastern Slavs under one Church. Other Orthodox Churches are structured according to an ethno-territorial model, that is, Greek Orthodox, Serbian Orthodox, Bulgarian Orthodox, and so on.

Confronted with mounting demands from Ukrainian political leaders after decades of independence from Russia, the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople signaled he would grant a tomos in late 2018, paving the way for the establishment of an independent, self-governing “Orthodox Church of Ukraine.” Efforts to establish ecclesiastical independence from Russia to mirror state independence have been in the making in some form since the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917 (Plokhy and Sysyn Reference Plokhy and Sysyn2003; Denysenko Reference Denysenko2018). In an effort to compensate for the vast disappointments over the lack of tangible change following the Maidan protests, political leaders worked tirelessly to secure the tomos. The creation of a new Ukrainian Orthodox Church became the President's signature accomplishment, reflecting once again the interpenetration of religious and political authority.

The Ecumenical Patriarch's decision prompted vigorous protests from the Russian Orthodox Church since significant numbers of its parishes are located in Ukraine. The dispute has ramifications for Orthodox communities around the world, some of whom must now choose between Constantinople and Moscow. Within three months of the tomos, approximately five hundred parishes in Ukraine left the Moscow Patriarchate (map 1). How, or if, larger, more valuable properties, such as the places animated with prayer profiled here, will re-affiliate remains entirely unclear as of this writing.Footnote 14

Map 1. Stars indicate the 502 parishes that stated an intention to reaffiliate to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine in the first three months after the tomos was granted.

Prior to the tomos, several Orthodox churches in Ukraine claimed to be national churches. The largest, in terms of having the most parishes by far, was the Russian Orthodox Church. Two “schismatic” churches united under a self-proclaimed Kyiv Patriarchate.Footnote 15 Neither was canonically recognized, and both formed in conjunction with aspirations for Ukrainian statehood, one after the Revolution in 1921 and the other in 1995 after the USSR collapsed. Finally, the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church, which predominates in western Ukraine, also has a Byzantine rite but its supreme authority is the Roman Catholic pope. It was outlawed in the USSR from 1946–1989, and with five million adherents it became the largest banned religious group in the world. The Orthodox Church associated with Moscow has the greatest amount of property, the Church allied with Kyiv has the greatest number of parishioners, and the Greek Catholic Church has the most committed members, so each has a unique source of power and presence in society. Given their doctrinal and liturgical similarities, one-third of the population circumvents this politicized fracturing by self-identifying as “just Orthodox.”

With serious challenges to Ukraine's sovereignty from Russia after 2014, efforts to secure an independent church became a powerful weapon for a weak state fighting a hybrid war. Ukrainian autocephaly deals a blow to Russian Orthodoxy, and by extension to Putin's standing, in retaliation for annexation and occupation of Ukrainian territory. In spite of the tomos victory, the president responsible for it was promptly voted out of office. The new leader was handed a list of “red lines” signed by NGOs, unions, journalists, writers, policy makers, and celebrities. They claimed to be “actively defending Ukraine's sovereignty and national interests.”Footnote 16 Among these lines not to be crossed was “implementing any actions aimed at undermining or discrediting the Orthodox Church of Ukraine or supporting the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine.” This statement contains no mention of religious conviction, practice, or affiliation, but it speaks volumes about the emotionally induced commitment of “sympathizers” to institutional religion. Individual, national, and moral well-being are conflated into a will to protect the trinity of church-nation-state. The signatories threatened “political instability” should any of the red lines be crossed. Why do they care? Why are they willing to take to the streets again if the state sides with one Orthodox church over another? The reason is as personal as it is political. The affective atmosphere of religiosity, which roots them in places where they feel they belong, has shaped political attitudes that connect meaningful individual experiences with geopolitical strategic goals via religious institutions.

ANIMATED PLACES AND RELIGION

I stated earlier that my goal was not to provide still another example of religious particularism in a secular society. I have analyzed seemingly innocuous appeals for assistance from otherworldly forces via improvised, episodic behaviors that reflect institutional disaffection and anticlericalism. Such forms of religiosity offer insulation against moral judgments and the retention of autonomy against communal obligations. Yet these practices are symbiotic to religious institutions and, in the eyes of many Ukrainians, become “religion” (as opposed to superstitions, folk practices, or New Age fads) when they are performed at sites where institutionalized religion, state authorities, and the political visions they promulgate all intersect. The affective attributes of an atmosphere of religiosity are sustained by embodied practices, whose kaleidoscopic variety paradoxically serves to homogenize allegiances and identities into a “just Orthodox” orientation to a faith tradition that colors public space and the politics of belonging and makes attachments to animated places normative for both believers and nonbelievers.

These practices unfold in a secular society with a historically and culturally dominant Eastern Christian tradition that is now freighted with stark choices of political allegiance and national orientation. Places animated with prayer, such as the Goldberg Church and Pochaiv Monastery, are embedded in political and ecclesiastical jurisdictions. Claiming ownership of these highly valued places has become a powerful tactical move in a hybrid war. These two religious sites are currently part of a confessionally defined, multinational “Russian World” that includes Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. The “Orthodox Army,” as some of the fighting force in eastern Ukraine is known, wants to keep it that way. Others, however, would prefer that these places were under the jurisdiction of a Ukrainian church that serves Ukrainians. Within the context of war, the difference is significant. Although individuals might attempt to divorce their own improvised appeals to otherworldly forces from the political by disassociating from clerical and institutional moorings, the fact remains that these transformative experiences occur in sites that are decisive carriers of the political. The political utility of places animated with prayer lies in their ability to forge attachments to contested places, to offer new forms of agency rooted in place, and to indirectly redeem a particular institutionalized religion and the political vision it promotes. In other contexts, the credit for curative relief or other forms of assistance delivered by a blend of Christian practices and indigenous faith systems is given to the power of Christianity, not to the specific places where the practices occur (Meyer Reference Meyer1999; Chua Reference Chua2011).

A pilgrimage to a monastery with connections to the Moscow Patriarchate on Ukrainian soil implies endorsement of neither the Russian Church nor an independent Orthodox Church of Ukraine, but the potential for political manipulation to curry favor in either direction exists. When an ambient presence of religiosity in the architectural, cultural, and aesthetic palette of the society is accompanied by widespread, sincere, and public appeals to otherworldly solutions to worldly problems, then the affective atmosphere that emerges can become a political resource by constituting subjects with underlying assumptions about the enchantment of the places in which they live or should live. Attachments to places animated with prayer, and to the experiences that occur there, spill over into allegiance to the state that offers its own protective powers to the people whose prayers have animated the place.

Affective objects, assemblages, and practices circulate from the Goldberg Church to the neighborhood to homes just as purifying experiences circulate from a monastery in western Ukraine to a sacred spring in a city park in eastern Ukraine. The emotional power of attachment to place is so formidable because it forges bonds to other people, some living and some dead, and to the land and its protector, be it a church or state. The intimacy of these bonds, affirmed and reaffirmed through practice, circulated and recirculated in public space, constitute this affective atmosphere of religiosity. As a heuristic device, an affective atmosphere gives us a vantage that refuses to isolate aspects of lived experiences, such as those we call “religion,” from the needs of governance. Confessionally unmarked understandings of “the religious” and “the political” shift in tandem with the needs of governance, highlighting the agentative properties of the material world to create a particular atmosphere from private sensations. An affective atmosphere, via mimetic abilities and bodily capacity, connects individual engagement in a socio-spatial environment to experiences that can be appropriated politically.

Analyzing the presence of unmarked religiosity underlines the social and political stakes of a public religiosity and allows us to propose more finely tuned comparative concepts for analyzing religious mainstreams in secular societies. Even when there is a significant degree of alienation from religious authorities and institutions, an affective atmosphere of religiosity can make religious institutions a significant political resource for government officials and opposition leaders, particularly during periods of crisis, because they are implicated in transformative experiences that are meaningful and motivating, albeit not always in predictable ways.