1. Introduction

This article applies the concept of spiritual intelligence (SI) to electroacoustic music (EA) so that the word ‘spirituality’ can be used in a way that is freed from either too much generality or too much religion.

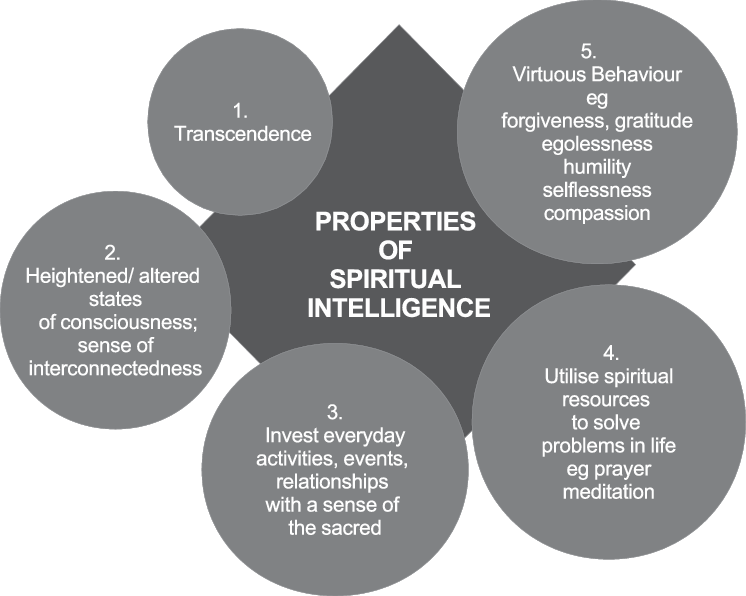

SI is used by psychologists and philosophers to expand the understanding of intelligence, begun as IQ and continued through EQ (emotional intelligence). Psychologist Robert Emmons (Emmons, Gardner, Kwilecki and Mayer Reference Emmons, Gardner, Kwilecki and Mayer2000) identifies five properties of SI, asserting that they all help people solve problems and attain goals in their everyday lives (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Properties of spiritual intelligence – Emmons.

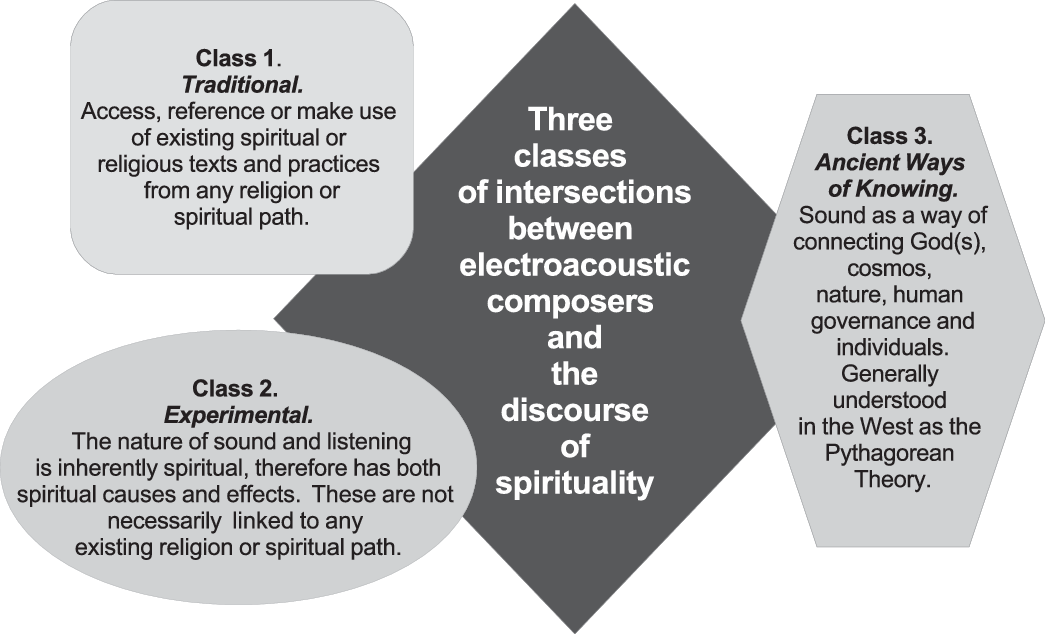

EA composers approach spirituality in different ways. Footnote 1 Some, such as Jonathan Harvey and Karlheinz Stockhausen, approach it more traditionally by drawing on existing sacred traditions. Others, such as Hildegard Westerkamp, Eliane Radigue and Ruth Anderson appear to approach sound as a way of exploring the nature of reality, which includes an inner resonance transforming their sense of self. Finally, some EA composers draw on ancient ways of replicating and understanding the universe. This can be generally thought of as the Pythagorean tradition although it has had many forms since its conception. Composers Laurie Spiegel and Bruno Degazio, in their versions of Kepler’s Harmonice Mundi, exemplify this tradition, as do some algorithmic composers, such as Michael Gogins. Figure 2 shows three different ways (classes) in which composers approach spirituality.

Figure 2. Three intersections between electroacoustic composers and the discourse of spirituality.

Class 1 refers to those works which reference, either in the actual work itself, or in the practice, spiritual texts or methods found within existing traditional religions or spiritual paths. Examples might include: the use of the I Ching or other divination tools as a compositional aid; using a sacred text or character from a religious tradition; soundscape compositions based on recordings of religious objects or spaces such as church bells, temple cymbals, sacred buildings or pilgrimages; or the creation of music for spiritual practices such as meditation, prayer or ritual.

Class 2 is more ephemeral. It refers to the idea that exploration and creation with sound is somehow inherently spiritual, but that it need not be tied to any specific path or tradition. In this class, both the activity and the product of sound art and composition seem to produce (as articulated by a significant number of composers and sometimes performers with whom I have talked directly or via the internet), unintended and mysterious feelings and thoughts that they, for want of a better word, describe as spiritual. The second class is for composers for whom the word ‘spiritual’, however they choose to define it, is part of their art practice, but who dislike some of the other words associated with the term, such as ‘religious’, ‘sacred’ or ‘traditional’.

Class 3 is for those who link with ancient ways of replicating and understanding the universe. This can be generally thought of as the Pythagorean tradition, although it has had many forms since its conception. Ancient ‘ways of knowing’ traditions assert that sound is intrinsic to the nature and relationship between God(s), cosmos, nature, human governance and individuals and is also tied up with mathematics. For the purpose of this article I consider this third class in relation to the Western tradition as articulated by Jeremy Begbie (Reference Begbie2007). It spans over two millennia, beginning with Pythagoras, through Plato, Augustine, Boethius and culminating in Kepler’s concept of Harmonices Mundi, where he argues that musical harmonies exist intrinsically within the spacing of the planets. The link between sound and the spirit as articulated in the East is for another study. Footnote 2 This particular class of music may also have contemporary relevance to algorithmic music because of the theory’s relationship to mathematics.

My research is inspired by four things: my understanding of my own compositional experience; the musical theorising of Christian theologian Jeremy Begbie; the way John Cage presents his music as having a spirituality based on Eastern religions (Larson Reference Larson2012) and the challenge put forward by Buddhist British composer Jonathan Harvey when he said: ‘We may begin the slow journey to an understanding of what “spirituality in music”, such a natural concept for composers of the past, might mean today’ (Harvey Reference Harvey1999: 7).

2. Properties of Spiritual Intelligence

Psychologist Robert Emmons has identified this organising concept that he sees as a type of intelligence, since it helps people to solve problems and attain goals in their everyday lives. He identifies the following five properties:

-

1. The capacity for transcendence.

-

2. The ability to enter into heightened or altered states of consciousness and/or a sense of radical interconnectedness.

-

3. The ability to invest everyday activities, events and relationships with a sense of the sacred.

-

4. The ability to utilise spiritual resources to solve problems in life.

-

5. The capacity to engage in virtuous behaviour (e.g., generosity, forgiveness, gratitude, humility, selflessness, compassion, egolessness).

The SI approach is valuable because it gives us components that we can identify with, whether or not we call ourselves religious. Thus we are freed from the unavoidable jargon around spirituality that is a consequence of its long intertwining with religions and cultures. So far, I have found that it is acceptable to both the religious and the non-religious alike. I also hope that it may be useful to some composers who have expressed to me, in no uncertain terms, that although they consider their music spiritual, they very much dislike words such as ‘sacred’ and ‘religious’.

This article is a general introduction to links between properties of spiritual intelligence and some works of electroacoustic music. Detailed mapping of the intersections between each of Emmons’s properties and particular works of electroacoustic music is for a further article. Nevertheless, I would like to briefly comment from personal experience, on how each of Emmons’s five spiritual properties may be applied to electroacoustic music.

2.1. Linking SI properties with existing works

I would consider the word transcendent to be appropriate to describing the kind of listening experience with a work such as Barry Truax’s Riverrun (Reference Truax1986). There is a sense of something much bigger than ourselves which lifts us into perhaps the imaginal realm, a term coined by Henri Corbin referring to a realm of archetypes and the divine. Footnote 3 Heightened or altered spiritual states of consciousness can occur during composing, performing and listening to minimalist or drone music. A friend who plays music like this has commented that she gets into a ‘zone’ where she is so completely unaware of herself that on one occasion, when she came out of it, she asked her fellow musicians whether or not she had continued playing! (She had!) People can experience an intense interconnectedness to nature and culture while listening to or participating in the following kinds of music: soundscape music; global, internet-based performances; and highly improvised music. Emmons’s third property (the ability to invest everyday activities, events, and relationships with a sense of the sacred) seems an appropriate way of describing the care, attention and almost reverence to the sonic world while making both the sounds themselves as well as the structure in EA music. An example of property four (utilising spiritual resources to solve problems in daily life) is in Harvey’s approach to creating Bhakti – he meditated for two weeks before he began the work. Property number five, which lists a variety of behaviours, is important to a number of composers. In particular, the desire for egolessness in the composition of music has been articulated by composers as distinct as John Cage and Giacinto Scelsi. John Cage ‘had seen that the true purpose of music must be to connect the individual to the eternal, and that in order to do this, he had to let go of ambition, loosen his ego’s hold on his music’ (Pritchett Reference Pritchett2016: 182). Scelsi has been quoted as saying that he is not a composer but simply a vessel for communication from the divine (IDFA n.d.).

3. Three classes of intersections between EA music/discourse of spirituality

In order to clarify different ways in which composers and works of EA intersect with the discourse of spirituality, I have identified three classes (see Figure 2).

3.1. Class One – Traditional

One of the most obvious intersections between spirituality and electroacoustic music is when composers access, reference or in some way make use of spiritual or religious texts or practices. This might include the following: referring to sacred scripture, character or commentary; works relating to liturgical or ritual structures; consciously incorporating meditation as part of the composition process; creating a work that is a prayer; creating soundscape compositions that use recordings from sacred sources or paths; incorporating divining methods into human decision-making; for example, the I Ching, as a way of determining the will of God or the universe. Below are some examples.

-

1. Eliane Radigue (b. 1936, France): Jetsun Mila (Reference Radigue1986). Incorporates Buddhist concepts.

-

2. Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007, Germany): Gesang der Jünglinge (Reference Stockhausen1956). Considered this work to be a kind of motet for a Catholic mass liturgy.

-

3. Jonathan Harvey (1936–2012, UK): Bhakti (1982). Meditated for two weeks before its creation.

-

4. Andrew Lewis (b. 1963, UK): Vox Dei (based on Psalm 19), and Vox Populi (Reference Lewis2011), choir and fixed media (using the sound of the cathedral bell), and installation respectively. In the latter, people can send a message to God by speaking into a microphone attached to signal processing and spatialisation. This is heard immediately within the space of the cathedral.

-

5. Gary Kendall (b. 1973, UK): Ikaro (Reference Kendall2009) and Wayda (Reference Kendall2002). Uses divining processes in these and other compositions (Kendall Reference Kendall2011).

-

6. Yiorgis Sakellariou (b. 1976, UK): Silentium (Reference Sakellariou2015). Discusses spirituality and electroacoustic music via his work composed from sounds of religious origin, the bell, the church interior and organ sounds from the Prague cathedral. He speculates on their effect on studio work and acousmatic performance.

-

7. Felipe Otondo (b. 1972, Chile): Sarnath (Reference Otondo2013). Uses field recordings (by Francis Booth), such as bells, drums and chants recorded from the places where the Buddha lived and taught throughout his life.

3.2. Class Two – Experimental

This approaches sound and listening directly via Emmons’s concept of spiritual intelligence, without the intermediary of an existing religion or spiritual path. It assumes that there is something about the nature of both creative sound-making and listening that is inherently spiritual. Footnote 4 First, it links with the universal spirit of creativity, found in almost all of nature and culture. Second, the listening experience itself – immersive, non-hierarchical and both objective and subjective – offers a model for the spiritual notion of ‘presence’, or ‘being in the now’ (Tolle Reference Tolle2004). This kind of experience is particularly pronounced in soundscape listening, as well as spectral and reduced listening. Finally, it supports a number of composers who assert vigorously that their music is spiritual, but have grave concerns about other words like religious, sacred, etc.

A quote from a recent New York Times obituary for composer Ruth Anderson, who used psychoacoustics and biofeedback techniques as part of her philosophy of composition, seems to support this:

[Her work] has evolved from an understanding of sound as energy which affects one’s state of being, she wrote in an autobiographical essay, adding that such pieces were ‘intended to further wholeness of self and unity with others.’ (Smith Reference Smith2019)

It is worth briefly considering a particular work, Talking Rain (Reference Westerkamp1997), by Hildegard Westerkamp, to see how some of Emmons’s spiritual properties might apply. A veteran of soundscape composition, Hildegard’s highly refined listening and studio practice draws music out from environmental sound. Woven together ‘song lines’ lead us on an enriching sonic journey of expanded aural consciousness and interconnection. Hildegard may or may not call her work ‘spiritual’. Nevertheless, I would like to assert that the spiritual attributes of expanded (aural) consciousness and sense of interconnection are present for this listener at least. Perhaps for the composer, Emmons’ category 3 (the ability to invest everyday activities, events, and relationships with a sense of the sacred), is present during the recording and compositional process.

One may also perhaps, under this class, consider the work of Jonathan Weinel (Reference Weinel2018), who has researched the creation of altered states of consciousness through electroacoustic music and audiovisual media.

3.3. Class Three – Ancient Ways of Knowing

The third category refers to the attractive intercultural, philosophical/theological idea that sound and listening, in and of itself, tells us something about the divine milieu. In the West, this tradition existed for two millennia from Pythagoras in the sixth century bce and perhaps has a continuing influence, even if radically reshaped in more recent cosmological theories. It argues that music/sound is the best analogue for a God-created/infused cosmos, which includes the universe, nature and the human’s ethical life. Recent thinking echoes this idea. Michio Kaku, the co-founder of string theory says: ‘We now, for the first time in history, have a candidate for the mind of God – it is cosmic music, resonating through eleven dimensional hyperspace.’ Footnote 5 Further, the tradition argues among many other things, that the mathematical elegance and simplicity of the harmonic series indicates divine reason at play in sonic nature. Footnote 6 Examples of works from the twentieth and twenty-first century which could fall into this class are: Ecology of Souls (Reference Newby1993) by Kenneth Newby (b. 1956, Canada), which uses structures based on the harmonic series and the table of Pythagoras; two recent versions of Kepler’s Harmonices Mundi, by Bruno Degazio (Reference Degazio2013; b. 1958, Canada) and Laurie Spiegel (Reference Spiegel1977; b. 1946, USA).

These three classes are useful for distinguishing ways in which existing works intersect with the discourse of spirituality, as clarified through the concept of spiritual intelligence. They are also helpful for the creation of new works. This author intends to classify a large number of existing works, given to her via an informal call-out with the CEC (Canadian Electroacoustic Community) in June 2019, according to these classes. She is also in the process of composing new compositions based on them.

4. Conclusion

I have briefly described the framework of Spiritual Intelligence with the hope that the word ‘spiritual’ may become more accessible to composers, performers and listeners. I have identified three ways in which composers link with the spiritual: Traditional, Experimental, and Ancient Ways of Knowing. Traditional refers to those works which reference, either in the actual work itself, or in the practice, spiritual texts or methods found within existing religions or paths. Experimental refers to the idea that exploration and creation with sound is somehow inherently spiritual, but need not be tied to any specific path or tradition. Ancient Ways of Knowing refers to works which link with ancient traditions from both the east and the west, where sound and mathematics is intrinsic to the nature and relationship between God(s), cosmos, nature, human governance and individuals.