Introduction

Irritability is a transdiagnostic symptom that has garnered a great deal of attention in the developmental psychopathology literature of late. Partially in response to an alarming increase in rates of bipolar disorder diagnoses in young children (Blader and Carlson, Reference Blader and Carlson2007), one line of research has explored alternative classification for children who exhibit severe, chronic irritability. Led by Leibenluft and colleagues, this research culminated in the addition of Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD) to the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). DMDD is a childhood-onset diagnosis in the depressive disorder section, defined by irritable or angry mood and severe temper outbursts. A related line of research has explored the dimensionality of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) (Leibenluft and Stoddard) symptoms, identifying a relatively stable irritable symptom dimension characterized by anger, touchiness, and temper outbursts. Compared to other ODD symptom dimensions (e.g. hurtful, headstrong), the irritable symptom dimension demonstrates differential concurrent and longitudinal correlates (e.g. Stringaris and Goodman, Reference Stringaris and Goodman2009, Burke, Reference Burke2012, Whelan et al., Reference Whelan, Stringaris, Maughan and Barker2013).

Across disorders, irritability has emerged as a clinically significant phenomenon, marking greater severity of psychopathology and functional impairment (Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Brotman and Costello2015, Wakschlag et al., Reference Wakschlag, Estabrook, Petitclerc, Henry, Burns, Perlman, Voss, Pine, Leibenluft and Briggs-Gowan2015). There has been particular interest in exploring links between irritability in childhood and adolescence with psychopathology later in life. The consensus emerging from this work is that chronically irritable children and adolescents go on to experience internalizing psychopathology later in life, particularly depression. This work has been summarized in a number of qualitative reviews (Burke and Loeber, Reference Burke and Loeber2010; Leibenluft and Stoddard, Reference Leibenluft and Stoddard2013; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Burke, Roberts, Fite, Lochman, Francisco and Reed2017) and a recent meta-analysis (Vidal-Ribas et al., Reference Vidal-Ribas, Brotman, Valdivieso, Leibenluft and Stringaris2016). While this evidence base is substantial, the literature has several significant gaps and limitations.

First, there has been little attention to variability in the way that irritability is assessed. Most commonly, irritability symptom items are extracted from diagnostic interviews geared to assessing DSM criteria for specific disorders. Most studies use an aggregate of the touchy or easily annoyed, angry or resentful and temper tantrum items from the ODD section of interviews (Stringaris and Goodman, Reference Stringaris and Goodman2009; Rowe et al., Reference Rowe, Costello, Angold, Copeland and Maughan2010; Burke, Reference Burke2012; Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Zavos, Leibenluft, Maughan and Eley2012b; Whelan et al., Reference Whelan, Stringaris, Maughan and Barker2013; Althoff et al., Reference Althoff, Kuny-Slock, Verhulst, Hudziak and van der Ende2014; Lavigne et al., Reference Lavigne, Gouze, Bryant and Hopkins2014; Leadbeater and Homel, Reference Leadbeater and Homel2015; Déry et al., Reference Déry, Lapalme, Jagiellowicz, Poirier, Temcheff and Toupin2017; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Sellers, Hammerton, Eyre, Bevan-Jones, Thapar, Collishaw, Harold and Thapar2017). In addition, some studies have combined these items with the irritability symptom items from the depression, dysthymia, and/or mania sections of the interview (Dougherty et al., Reference Dougherty, Smith, Bufferd, Stringaris, Leibenluft, Carlson and Klein2013; Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Shanahan, Egger, Angold and Costello2014; Dougherty et al., Reference Dougherty, Smith, Bufferd, Kessel, Carlson and Klein2015; Pagliaccio et al., Reference Pagliaccio, Pine, Barch, Luby and Leibenluft2018). Studies exploring DMDD most often make the diagnosis ex post facto based on endorsement of irritability items from both the ODD and major depression sections (e.g. Dougherty et al., Reference Dougherty, Smith, Bufferd, Kessel, Carlson and Klein2016). Finally, one study considered irritability items assessed from a depression-focused measure only (Kouros et al., Reference Kouros, Morris and Garber2016).

The context in which a symptom is assessed (e.g. in order to make a particular diagnosis) and differences in the way items are worded could impact how the items are rated and, ultimately, what phenomena are captured. This is exemplified by one of the earlier longitudinal studies by Leibenluft's group, which distinguished between irritability assessed with items from the depression and mania section of the interview, which they considered ‘episodic irritability,’ and irritability assessed with items from the ODD section, labeled ‘chronic irritability’ (Leibenluft et al., Reference Leibenluft, Cohen, Gorrindo, Brook and Pine2006). They found that stability correlations for each type of irritability over time were greater than the correlations between types over time. Further, episodic irritability was a significant predictor of anxiety and mania in late adolescence, and mania only in early adulthood, while chronic irritability predicted ODD and attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) in late adolescence, and major depression in early adulthood. Despite this finding, surprisingly few studies since have considered whether irritability is a multifactorial construct and how that may translate to different trajectories of psychopathology across development.

Another limitation of the literature concerns the assessment of externalizing outcomes. While some reviewers have argued that irritability is primarily related to later internalizing disorders (Vidal-Ribas et al., Reference Vidal-Ribas, Brotman, Valdivieso, Leibenluft and Stringaris2016; Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Vidal-Ribas, Brotman and Leibenluft2018), these conclusions may be premature given limitations in the assessment of externalizing psychopathology. That is, a substantial portion of studies exploring the longitudinal relationship between irritability and psychopathology have not explored links to externalizing disorders at follow-up (Burke, Reference Burke2012; Lavigne et al., Reference Lavigne, Gouze, Bryant and Hopkins2014; Kouros et al., Reference Kouros, Morris and Garber2016; Déry et al., Reference Déry, Lapalme, Jagiellowicz, Poirier, Temcheff and Toupin2017; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Sellers, Hammerton, Eyre, Bevan-Jones, Thapar, Collishaw, Harold and Thapar2017). Among studies that do, the focus is largely on ODD, ADHD, and conduct disorder (CD) in adolescents, with relatively less attention to externalizing outcomes in adults, such as substance use disorders (SUD) and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). Only three prior studies have looked at SUD as an outcome (Pickles et al., Reference Pickles, Aglan, Collishaw, Messer, Rutter and Maughan2010), two of which also assessed ASPD (Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Cohen, Pine and Leibenluft2009; Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Shanahan, Egger, Angold and Costello2014).

In general, most studies have focused on outcomes in late childhood through adolescence, with few studies following participants into adulthood. Among the studies that have included adults in their follow-up sample, some used irritability items from the ODD-section only (Stringaris and Goodman, Reference Stringaris and Goodman2009; Althoff et al., Reference Althoff, Kuny-Slock, Verhulst, Hudziak and van der Ende2014; Leadbeater and Homel, Reference Leadbeater and Homel2015), while others used measures that combined items from both the depression and ODD sections (Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Shanahan, Egger, Angold and Costello2014). Some studies did not account for continuity of psychopathology by adjusting for the presence of the outcome disorders at baseline (Pickles et al., Reference Pickles, Aglan, Collishaw, Messer, Rutter and Maughan2010; Althoff et al., Reference Althoff, Kuny-Slock, Verhulst, Hudziak and van der Ende2014; Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Shanahan, Egger, Angold and Costello2014). Finally, several studies employed mixed-age cohorts so that at follow-up, samples included both adolescents and adults (Stringaris and Goodman, Reference Stringaris and Goodman2009; Althoff et al., Reference Althoff, Kuny-Slock, Verhulst, Hudziak and van der Ende2014; Leadbeater and Homel, Reference Leadbeater and Homel2015). These inconsistencies suggest the need for further investigation of the adult outcomes of youth irritability.

A final noteworthy feature of this literature is that a vast majority of studies used parent report of irritability, either exclusively or combined with child or teacher report. Only four studies exploring prospective psychopathology outcomes have used irritability data from youth without considering parent report (Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Zavos, Leibenluft, Maughan and Eley2012b; Leadbeater and Homel, Reference Leadbeater and Homel2015; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Blossom and Fitein press), one of which also presented results for parent-reported irritability (Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Cohen, Pine and Leibenluft2009). The predominant focus of prior studies on parent-report is appropriate given that many of these studies assessed irritability in childhood or early adolescence. However, for youths in mid-late adolescence who are more independent and perhaps less open with their parents about their internal struggles, there is particular benefit in understanding how self-report compares in this context.

The current study aims to augment this literature by examining the relationship between self-reported irritability in adolescence and subsequent psychopathology in adulthood, taking into account these issues. Using data from the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (OADP; Lewinsohn et al., Reference Lewinsohn, Hops, Roberts, Seeley and Andrews1993), we first explored dimensionality in the irritability symptom items from the major depression, dysthymia, mania, and ODD sections of a semi-structured diagnostic interview. Next, we examined the relationship between these dimensions of irritability in adolescence and psychopathology assessed at age 24 and 30.

Methods

Participants

The OADP is a large, prospective study of psychopathology in a community sample of three cohorts of adolescents recruited between 1987–1989 (Lewinsohn et al., Reference Lewinsohn, Hops, Roberts, Seeley and Andrews1993, Rohde et al., Reference Rohde, Lewinsohn, Klein, Seeley and Gau2013). Participants were randomly selected from nine high schools representative of urban and rural districts in western Oregon. At the initial assessment (T1), the original sample of 1709 participants ranged in age from 14–19 (M = 16.6; s.d. = 1.2) and 9% of participants were non-White. All participants were invited for a second assessment (T2) approximately one year later (M = 13.8 months; s.d. = 2.3). Of the 1507 participants who returned for the T2 assessment, participants with a history of a mental disorder by T2 (n = 644) and a random sample of participants with no history of a mental disorder by T2 (n = 457) were invited to participate in a third assessment (T3) when they turned 24 years old. Of these, 85% (n = 941) participated in the T3 assessment. A fourth wave of assessments (T4) was conducted when participants turned 30 years old, and 87% (n = 816) of participants from T3 returned for this final assessment. T1 assessments were conducted in-person (either in the lab or at the school) while T3 and T4 assessments were conducted over the phone because many participants had moved out of the area. All study procedures were approved by the appropriate institutional review board and written informed consent was obtained from all participants (and their guardians, if applicable) at all assessments. More detailed description of study procedures can be found elsewhere (e.g. Lewinsohn et al., Reference Lewinsohn, Hops, Roberts, Seeley and Andrews1993).

For this study, we focused on predicting outcomes at T3 and T4 from T1 to ensure that our outcome samples were exclusively adult. Attrition from T2 to T3 and from T3 to T4 did not differ as a function of diagnostic status by T2 and T3, respectively. Among the 941 participants in the T3 wave, 57.3% were female and 10.9% were non-White. The distribution of race did not differ between T3 and T4 samples, however, a significantly larger proportion of women returned for the T4 assessment compared to those who did not (58.8 v. 47.2%), χ2(1) = 5.99, p = 0.01.

Measures

Irritability was assessed with a version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS) that combined features of the epidemiologic version (K-SADS-E; Orvaschel et al., Reference Orvaschel, Puig-Antich, Chambers, Tabrizi and Johnson1982) with the present episode version (K-SADS-P). The interview was conducted with the participant only (i.e. parents were not interviewed about the teen). Three items from the depression, dysthymia, and mania sections that inquire about periods of feeling angry, grouchy, cranky or irritable, and three items from the ODD-section that probe whether the participant is often angry or resentful, often mad or easily annoyed, and often loses temper, were extracted to assess irritability. All six items were rated based on the worst period in their lifetime, so that these items essentially captured whether a participant had experienced a significant period of irritability at any point in their lives up to the time of assessment. We chose to use the symptom items rated based on the worst period instead of the current episode ratings, because current episode ratings for the irritability items from the ODD section were not available. The irritability symptom items were coded as present or absent. All six items were assessed in all participants (i.e. they were not affected by skip-outs).

Axis I diagnoses were assessed solely with the K-SADS at T1 and jointly with the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE; Keller et al., Reference Keller, Lavori, Friedman, Nielsen, Endicott, McDonald-Scott and Andreasen1987) at T3. At T4, diagnoses were jointly assessed with the LIFE and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1997). T1 diagnoses were based on the DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) criteria, while T3 and T4 diagnoses were based on DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). We included diagnoses if they were rated as threshold or not otherwise specified (NOS) and if they occurred at any point in the lifetime up to the time of assessment for T1. Outcome variables counted psychopathology reported since the last assessment (i.e. since T2 for T3 outcomes and since T3 for T4 outcomes).

We combined disorders into diagnostic groups coded as any disorder present/absent because of the relatively low rates of many individual disorders. The diagnostic groups of interest for the T3 and T4 outcomes included depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and SUD. For depression, we counted major depression, dysthymia, and depressive disorder NOS. Anxiety disorders included panic disorder with and without agoraphobia, specific and social phobia, separation anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder, and anxiety disorder NOS. SUD included abuse or dependence of alcohol or any illicit (at the time) drug. Finally, we created a disruptive behavior disorder (DBD) category, which included ODD, ADHD, and CD. DBDs were not explored as outcomes at T3 and T4 but were included as T1 covariates in some analyses. Diagnostic group variables were coded as any disorder present or absent.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

T1 demographics are reported for the subset of the original sample who returned for at least the T3 follow-up, therefor the distribution of gender and race is identical across T1 and T3.

s.d., standard deviation; SUD, substance use disorder; DBD, disruptive behavioral disorder; ASPD, antisocial personality disorder; BPD, borderline personality disorder; IRR-MOOD, the mood disorder irritability dimension; IRR-ODD, the oppositional defiant disorder irritability dimension.

Personality Disorder Symptoms were assessed with the International Personality Disorder Evaluation (IPDE) at T3 and T4. The IPDE is a semi-structured interview of personality disorder symptoms based on DSM-IV criteria. ASPD and borderline personality disorder (BPD) were the only personality disorders assessed because they are the most widely researched. Symptoms were summed to create dimensional measures of ASPD and BPD because of the relatively low base rates of these disorders in our sample. We excluded the symptoms referring to behavior occurring before age 15 from the ASPD symptom total because these could have occurred prior to the T1 assessment and thus would not reflect adult outcomes. We also excluded the item probing ‘lack of remorse’ from both T3 and T4 because it was not assessed at T4 (Table 1).

Data analysis

All analyses were weighted to account for overselection of participants reporting a mental disorder by T2 in the follow-up samples. Analyses were conducted in Mplus version 8.1 (Muthén and Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2010).

First, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using robust weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimation was conducted to evaluate dimensionality of the irritability symptom items assessed at T1. WLSMV estimation is recommended for categorical indicators (Rhemtulla et al., Reference Rhemtulla, Brosseau-Liard and Savalei2012). Factor solutions with eigenvalues greater than one were extracted and oblique geomin rotation was applied to allow factors to correlate. Although parallel analysis is generally recommended to determine the number of factors to retain (Hayton et al., Reference Hayton, Allen and Scarpello2004), Muthén and Muthén (Reference Muthén and Muthén2013–2017) have found it to be inaccurate with categorical indicators. Model selection was based on χ2 difference testing and evaluation of fit indices in accordance with Muthén and Muthén's recommendation for WLSMV. Irritability symptom dimensions to be used in later analyses were created based on the sum of irritability items loading on each factor. Results of the EFA conducted on the sample of participants who came for the T3 follow-up were reported, as the T4 follow-up sample was completely nested within the T3 sample and results did not differ substantively between the two samples.

Next, the irritability symptom dimensions were entered into binary logistic regression models predicting any SUD, depressive, or anxiety disorder at later assessments. Separate models predicted T3 and T4 outcomes in order to explore whether outcomes differed as a function of age at follow-up. The personality disorder symptom variables followed a count-like distribution (i.e. positive integer values concentrated at or near zero) with over-dispersion (i.e. conditional variance > conditional mean), so we used negative binomial regression to model BPD and ASPD symptoms at T3 and T4 (Coxe et al., Reference Coxe, West and Aiken2009). We initially ran each model controlling for gender, race, age at T1, and all T1 psychopathology diagnostic groups (i.e. depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, SUD, and DBD). Including many uninformative covariates can be problematic, (e.g. leading to numerically unstable estimates and large standard errors; Bursac et al., Reference Bursac, Gauss, Williams and Hosmer2008), so covariates with p > 0.10 were dropped from the final models. Results did not differ substantively between the initial and final models. The initial models containing all covariates can be found in the online Supplementary appendix.

Missing data

In our larger T3 sample, 84 (8.9%) participants were missing irritability symptom items, 39 (4.1%) participants were missing BPD symptom scores, and 37 (3.9%) of participants were missing ASPD symptom scores. We addressed missing data by using multiple imputation, creating 100 ‘complete’ datasets. All predictor and outcome variables were included in the imputation models to improve the accuracy of the missing data estimates. This process was completed separately for T3 and T4 outcomes. Regression analyses were conducted in each imputed dataset and results were pooled across analyses. As Mplus does not allow for multiple imputation with EFA, this analysis was conducted on pairwise complete data.

Results

Exploratory factor analysis of the irritability items

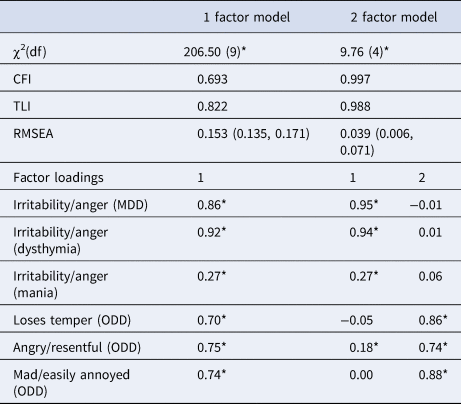

Factor loadings and model fit indices are reported in Table 2. One-factor and 2-factor solutions produced eigenvalues greater than one and a χ2 difference test suggested that the 2-factor solution provided a significantly better fit, χ2(5) = 168.822 (p < 0.001). Additionally, approximate fit indices (Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.997; Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.988; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.039, 95% confidence interval = 0.006-0.071) surpassed commonly cited thresholds (Hooper et al., Reference Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen2008), suggesting that the 2-factor model fit the data well.

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis of irritability items

MDD, major depressive disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder.

*Significant at p < 0.05; the 2-factor model fit significantly better than the 1 factor model χ2(5) = 168.822, p < 0.001.

The irritability items from the major depression, dysthymia, and mania sections all loaded on the first factor, suggesting that this factor embodies a mood disorder dimension. Although the mania item loading was relatively small (loading = 0.27), it did not cross-load on the second factor and thus we retained it in the mood disorder dimension. These three items were summed to create a mood disorder irritability dimension, which we will refer to as IRR-MOOD for efficiency of communication. All three irritability items from the ODD section loaded strongly on the second factor (loadings = 0.74–0.88). The angry or resentful item loaded significantly on the first factor as well, however, this loading was much smaller (0.18 v. 0.74), suggesting that it was a better indicator of the second factor. The three irritability items from the ODD section were summed to create an ODD irritability dimension, which we will refer to as IRR-ODD. The IRR-MOOD and IRR-ODD factors were moderately correlated (r = 0.41), further suggesting that these items are probing distinct, but related dimensions of irritability.

Regression analyses predicting psychopathology in early-mid adulthood

Results of the binary logistic regression analyses predicting depression, anxiety, and SUD at T3 and T4 are displayed in Table 3. The IRR-MOOD dimension predicted depression at T3 (but not T4) and anxiety at T4 (but not T3), but it did not predict SUD at either timepoint. In contrast, the IRR-ODD dimension predicted SUD at both timepoints, and anxiety at T3 (but not T4), but did not predict depression at either timepoint. Males had a significantly lower risk for depression and anxiety and a higher risk for SUD, compared to females. Younger age at T1 was associated with increased risk of SUD at T3 (but not T4). Additionally, participants with a SUD at T1 were at increased risk of depression at T3 and T4 and anxiety at T3 (but not T4).

Table 3. Logistic regression models predicting depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; IRR-MOOD, the mood disorder irritability dimension; IRR-ODD, the oppositional defiant disorder irritability dimension; SUD, substance use disorder.

Results of the negative binomial regression analyses predicting ASPD and BPD symptoms at T3 and T4 are reported in Table 4. Neither irritability dimension predicted ASPD symptoms at T3, while IRR-ODD (but not IRR-MOOD) predicted ASPD symptoms at T4. Male sex and T1 DBD and SUD were relatively strong predictors of ASPD symptoms at both T3 and T4. Additionally, younger age at T1 assessment predicted greater severity of ASPD symptoms at T4. At T3, IRR-MOOD predicted BPD symptoms and IRR-ODD approached significance (p = 0.06). At T4, both IRR-ODD and IRR-MOOD predicted BPD symptoms. T1 SUD and DBD predicted BPD symptoms at T3 and T4, while T1 depression predicted BPD symptoms at T3 only. Examination of the variance inflation factor revealed that multicollinearity was not an issue for any of the models.

Table 4. Negative binomial regression models predicting personality disorder symptoms

s.e., standard error; IRR-MOOD, the mood disorder irritability dimension; IRR-ODD, the oppositional defiant disorder irritability dimension; SUD, substance use disorder; DBD, disruptive behavioral disorder; race is coded as a nominal variable with 5 levels.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first paper to explore dimensionality in irritability symptoms assessed across multiple sections of a diagnostic interview using a data-driven approach. The results of our EFA are in line with Leibenluft et al. (Reference Leibenluft, Cohen, Gorrindo, Brook and Pine2006) theory-driven distinction between irritability symptoms from the mood disorder section and irritability symptoms from the ODD section, which they labeled ‘episodic’ and ‘chronic’ irritability, respectively. We referred to these dimensions as the IRR-MOOD and the IRR-ODD so as to remain neutral about the meaning of the latent factors.

As reviewed above, most investigators have concluded that irritable youth go on to develop internalizing psychopathology, particularly depression. The results of our prospective analyses exploring the association between irritability assessed in adolescence and psychopathology assessed in early-mid adulthood yielded more nuanced findings.

First, the IRR-ODD dimension did not predict depression at either follow-up. This is particularly surprising given that a number of studies using an ODD-only assessment of irritability have found this relationship to be significant (e.g. Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Cohen, Pine and Leibenluft2009). Several factors likely contributed to this discrepancy. First, our study accounted for covariance between the two irritability dimensions. We observed that the IRR-MOOD dimension predicted depression in early adulthood over and above IRR-ODD, suggesting that significant associations in previous studies using the ODD items alone or when aggregated with the mood disorder items could have been driven, in part, by shared variance between irritability symptom items from both sections of the interview.

Additionally, few previous studies have assessed psychopathology in adulthood, and most of those that have focused on the period of late adolescence through early adulthood. The fact that neither irritability dimension predicted depression at T4 (age 30) could indicate that irritability does not predict increased risk for depression after early adulthood, over and above prior depression. Alternatively, it could be that, specifically, self-reported irritability does not predict depression in adulthood, given that Stringaris et al. (Reference Stringaris, Cohen, Pine and Leibenluft2009) found that parent but not child-reported irritability in adolescence predicted depression assessed around age 33. Further study of adult outcomes of irritability is needed to clarify which factors are driving these discrepancies.

Regardless, there is evidence to suggest that this relationship is sensitive to developmental period. For example, a twin study parsing additive genetic effects of irritability and symptoms of depression/anxiety across late-childhood through early-adulthood found that, although there was significant genetic overlap across development, this overlap was strongest at ages 13–14 and the relationship between irritability and depression/anxiety was bidirectional at some, but not all, ages (Savage et al., Reference Savage, Verhulst, Copeland, Althoff, Lichtenstein and Roberson-Nay2015). Additionally, Leadbeater and Homel (Reference Leadbeater and Homel2015) found that, although irritability was moderately stable across adolescence-early adulthood, irritability only predicted internalizing symptoms in the transition from ages 18–19 to ages 20–21. This suggests that the nature of the relationship between irritability and internalizing symptoms changes across development. Thus, irritability may play a central role in the development of internalizing pathology in childhood and adolescence, but this relationship may attenuate after early adulthood.

The results for SUD and ASPD also extend previous research. No prior study has reported that irritability significantly predicted SUD or ASPD in adulthood. In contrast, IRR-ODD significantly predicted ASPD at T4 and SUD at both follow-up waves in our study. These findings challenge the assumption that irritability has a specific association with later internalizing psychopathology. Rather, it seems that this relationship depends on developmental stage and how irritability is assessed. Notably, none of the prior studies exploring this relationship in purely adult samples appeared to use the ODD irritability symptom items alone, which may explain this discrepancy. However, there are very few studies exploring externalizing outcomes in adulthood at all. This is likely due to the fact that, by convention, fewer externalizing disorders are assessed in adult diagnostic interviews. ADHD and CD were only recently added to the adult SCID for DSM-5 as optional modules not included in the main interview.

Our finding that IRR-ODD did not predict T3 ASPD is consistent with previous work exploring conduct problems in late adolescence-early adulthood using ODD-only measures of irritability (Stringaris and Goodman, Reference Stringaris and Goodman2009, Althoff et al., Reference Althoff, Kuny-Slock, Verhulst, Hudziak and van der Ende2014, Leadbeater and Homel, Reference Leadbeater and Homel2015). That IRR-ODD predicts ASPD symptoms in mid, but not early, adulthood may be explained by Moffitt's dual taxonomy of antisocial behavior (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt1993). Observing that prevalence of antisocial behavior peaks during adolescence, Moffitt has argued for two subgroups of individuals engaging in antisocial behavior; a life-course persistent group who engages in antisocial behavior throughout the lifespan and is characterized by more severe externalizing problems and a less severe adolescence-limited group whose antisocial behavior emerges during adolescence and desists by adulthood. It could be the case that our T3 assessment of ASPD was capturing a mix of antisocial subgroups, whereas our T4 assessment was more exclusively represented by life-course persistent individuals more likely to have experienced IRR-ODD during adolescence.

The results of the analyses predicting anxiety disorders at T3 and T4 are more challenging to explain. Only the IRR-ODD dimension predicted anxiety disorders at T3, while only the IRR-MOOD dimension predicted anxiety disorders at T4. Post-hoc analyses revealed little overlap in participants with anxiety disorders at T3 v. T4, however, exploratory analyses did not reveal notable differences in the composition of specific anxiety disorders or the patterns of comorbidity. Future research should elucidate whether these are spurious findings or capture meaningful relationships.

Surprisingly, the literature has largely ignored BPD as a prospective outcome of irritability in youth. Affective instability, and particularly, proneness to hostility and anger are central features of BPD. Further, there is evidence that ODD symptoms in childhood predict BPD symptoms in adolescence (Stepp et al., Reference Stepp, Burke, Hipwell and Loeber2012), however, this study did not distinguish between irritable and defiant/hurtful symptoms of ODD. One study compared the relationship between ODD symptom dimensions and BPD (Burke and Stepp, Reference Burke and Stepp2012), and found that the oppositional behavior dimension, but not the negative affective dimension, predicted BPD at age 24. Notably, this study defined negative affectivity using the spiteful symptom and two of the three irritability symptoms we have included, and they included the ‘loses temper’ symptom in the oppositional behavior dimension. In our study, both IRR-MOOD and IRR-ODD predicted severity of BPD symptoms at T3 and T4, although the relationship between IRR-ODD and BPD at T3 fell just short of the threshold for significance. Taken together, this suggests that irritability in youth, and perhaps both dimensions of irritability, may be precursors of BPD in adulthood. This is consistent with structural analyses indicating that BPD straddles both internalizing and externalizing dimensions of psychopathology (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, Krueger, Keyes, Skodol, Markon, Grant and Hasin2011). Further investigation of the role of irritability in the development of BPD is warranted.

It is notable that, although the 2-factor model provided superior fit compared to the 1-factor model, all irritability items loaded significantly onto the single factor and, in the 2-factor model, the factors were moderately correlated. This suggests that there is moderate overlap in the two dimensions of irritability and therefore it is unsurprising that many researchers have combined them. It is possible that the stronger relationship among irritability items within than between diagnostic sections reflects shared method variance rather than differences in the underlying trait. For instance, interviewers may have a lower threshold for positively rating the irritability item from the depression sections if other depression symptoms are present. Additionally, the items from the same section are administered more closely together in time than items from different sections. Nevertheless, the two dimensions demonstrated different patterns of longitudinal correlates, both in our study and in Leibenluft et al. (Reference Leibenluft, Cohen, Gorrindo, Brook and Pine2006), even when holding concurrent psychopathology constant. Further, Leibenluft and colleagues found that chronic and episodic irritability followed different trajectories across development, with episodic irritability increasing linearly from late-childhood through early adulthood and chronic irritability peaking in mid-adulthood. This suggests that shared method variance cannot entirely account for this distinction and that the two dimensions of irritability symptoms are likely capturing meaningfully distinct phenomena.

The question remains of how to interpret the two dimensions of irritability symptoms. Apart from context/method variance effects, one possibility is that the irritability items from the mood disorder section reflect subjective affective experiences such as grouchy, grumpy or angry mood, while the items from the ODD section capture behavioral expressions of irritability, such as temper tantrums. Carlson and Klein (Reference Carlson and Klein2018) note that the affective and behavioral aspects of irritability can have differing impact on functioning and different clinical implications. Another, not incompatible, possibility is that the probes in the mood disorder sections inquire about specific periods of time (i.e. ‘periods of feeling angry, grouchy, cranky, or irritable’), suggesting episodicity, whereas the questions in the ODD section stipulate that the symptoms occur ‘often,’ implying some degree of chronicity. Hence, the two sets of items may reflect differences in course, as suggested by Leibenluft et al. (Reference Leibenluft, Cohen, Gorrindo, Brook and Pine2006). Most likely, the two dimensions identified in our data reflect a combination of differences in affective v. behavioral expression of irritability, course, and method factors. We echo the call from Stringaris et al. (Reference Stringaris, Goodman, Ferdinando, Razdan, Muhrer, Leibenluft and Brotman2012a) and others for more specific measures of irritability that will be able to provide a clearer characterization of the components (e.g. behavioral v. affective, episodic v. chronic) of this important clinical phenomenon, independent of a diagnostic context.

Limitations

The many strengths of this study should be considered in light of its limitations. First, because we used a community sample, rates of many individual disorders were relatively low and could not be assessed as independent outcomes. Second, although T1 assessments were conducted in adolescence, the diagnostic interviews covered the lifespan up to the time of assessment. As such, we were unable to distinguish between participants who experienced irritability at earlier (e.g. early childhood) v. later (e.g. mid-adolescence) developmental periods. Additionally, we were unable to compare the timing of mood symptoms relative to ODD symptoms, however, symptoms within a diagnostic section were rated based on the same period. Third, as is the case of all studies that employ retrospective reports, there is risk of recall bias. Fourth, we were limited to using existing diagnostic interviews that were designed to assess irritability as a symptom of a larger syndrome. This is a common approach, however, future research would benefit from using more specific measures that assess irritability in a transdiagnostic manner. Fifth, although irritability is a feature of generalized anxiety disorder, the irritability item from this section could not be included in the T1 irritability composites because it is not part of the screener and thus not assessed unless the cardinal symptoms are endorsed. Finally, we were limited to interviews with adolescents. As parent-report also has limitations, it would be ideal to obtain both parent and adolescent report for comparison.

Conclusions

Despite a large literature exploring longitudinal outcomes of irritable youth, few of these studies have considered the multidimensionality of irritability. The results of the present study suggest that the irritability symptom items in a widely used diagnostic interview represent distinct dimensions that are associated with different psychopathological outcomes in adulthood. These findings challenge the assertion that irritable youth grow specifically into internalizing adults; rather, different facets of irritability appear to predict internalizing and externalizing outcomes. Exploration of the irritability dimensions in other samples is needed to confirm these, as irritability is clearly a marker of persisting impairment that warrants more nuanced assessment that takes its multidimensionality into account.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719002903

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the seminal contributions of Peter M. Lewinsohn, who initiated and led the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project.

Financial support

This research was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health Awards MH40501, MH50522, and MH52858.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.