Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a condition characterized by impaired social communication and interactions, associated with a pattern of repetitive behaviors and narrow interests, with or without intellectual disability. 1 A wide number of studies focusing on autism etiopathogenesis highlighted the role of genetic heritability, which seems to interact with environmental, mostly intrauterine, factors.Reference Carpita, Muti and Dell’Osso 2 – Reference Kim, Son and Son 5 Although a family aggregation is reported in ASD since 1977,Reference Folstein and Rutter 6 an increasing number of studies stressed the presence of a wide spectrum of milder symptoms, such as cognitive, social, and language impairments, among parents and siblings of ASD subjects. This evidence led to the concept of broad autism phenotype (BAP), a label employed to describe the wide spectrum of subthreshold autistic traits (AT) that can be frequently detected among first-degree relatives of ASD probands.Reference Folstein and Rutter 6 – Reference Billeci, Calderoni and Conti 15 Parents of ASD patients often show little interest in social interactions, and they usually have few, shallow friendships.Reference Losh and Childress 14 , Reference Piven, Palmer and Jacobi 16 In this framework, Sucksmith et al reported, among fathers of ASD probands, the presence of empathy deficits.Reference Sucksmith, Allison and Baron-Cohen 17 Moreover, parents and siblings of ASD children frequently show difficulties related to verbal and nonverbal communicationsReference Bishop, Maybery and Maley 18 – Reference Ruta, Mazzone and Mazzone 22 as well as impaired executive functionsReference Delorme, Gousse and Roy 23 and a ASD-like pattern of narrow interests.Reference Whitehouse, Barry and Bishop 19 – Reference Sucksmith, Roth and Hoekstra 21 , Reference Briskman, Happe and Frith 24 , Reference Robel, Rousselot-Pailley and Fortin 25 Taken together, all these elements—impaired social skills, language difficulties, restricted interests, and behaviors, similar, although less severe, to those of ASD patients—represent the typical features of BAP, which has been interpreted as a mild phenotypic variant of the disorder.Reference Losh and Childress 14 , Reference Bailey, Palferman and Heavey 26 – Reference Ruzich, Allison and Smith 28 Some authors reported that even the Theory of Mind, the ability to assess information related to other people’s mental states, seems to be compromised in parents of ASD children,Reference Happé 29 – Reference White, Hill and Happé 32 although this result has not been confirmed in all the studies.Reference Sucksmith, Roth and Hoekstra 21 , Reference Ozonoff, Rogers and Farnham 33 In this framework, other studies pointed out that some specific personality traits can be frequently found among family members of ASD subjects, such as shyness, suspiciousness, hypersensitivity to criticism, aloofness, insensitivity, and rigidity.Reference Losh and Childress 14 , Reference Piven 34 A wide number of studies investigated neurobiological features of first-degree relatives of ASD children, further supporting the conceptualization of BAP.Reference Carpita, Muti and Dell’Osso 2 , Reference Carpita, Marazziti and Palego 4 , Reference Billeci, Calderoni and Conti 15 In particular, neuroimaging has been variously employed in this population, reporting neurostructural and neurofunctional alterations in parents of ASD probands, also in those not behaviorally impaired (although more significant abnormalities were reported in subjects with behavioral correlates of BAP).Reference Billeci, Calderoni and Conti 15 Although genetic epidemiological studies stressed a genetic basis and heritability not only of ASD features, but also of BAP-like personality traits,Reference Billeci, Calderoni and Conti 15 abnormalities in different kinds of biochemical parameters have been found among parents of ASD children, similar to those reported in their probands,Reference Carpita, Muti and Dell’Osso 2 , Reference Carpita, Marazziti and Palego 4 Higher blood levels of serotonin (5-HT) is one of the traits more consistently associated with autism spectrum,Reference Carpita, Marazziti and Palego 4 but most recent studies highlighted also altered levels of inflammatory markers, oxidative stress, and microbiota profiles in both ASD and BAP subjects.Reference Carpita, Muti and Dell’Osso 2 , Reference Carpita, Marazziti and Palego 4 These findings are of particular interest because they may contribute to explaining the higher prevalence of autoimmune diseases and gastrointestinal symptoms among ASD children and their relatives, further characterizing BAP also from a neuroimmunological point of view.Reference Carpita, Muti and Dell’Osso 2 , Reference Carpita, Marazziti and Palego 4

More recently, increasing literature is stressing that subthreshold autism spectrum symptoms seem to be continuously distributed in general population, and in particular in some high-risk groups, such as university students, as well as among clinical samples of patients with other psychiatric disorders, where AT are generally associated with higher severity and with increased suicide ideation and behaviors.Reference Dell’Osso, Dalle Luche and Cerliani 35 – Reference Dell’Osso, Bertelloni and Di Paolo 47 Although in literature the impact of AT in global functioning has been investigated in general population,Reference Jobe and White 48 – Reference Suzuki, Miyaki and Eguchi 51 studies among parents of ASD children generally focused mainly on work and social adjustment related to the burden to raise a child with ASD, rather than on the functional impairment related to their own AT.Reference Ooi, Ong and Jacob 52 On the other hand, the prevalence of psychiatric conditions has been investigated also among relatives of ASD probands, highlighting an increased risk for mood disorders: one of the firsts studies in the field was led by Delong and Dwyer,Reference DeLong and Dwyer 53 who found a higher rate of mood disorders in relatives of ASD children with respect to the general population. Other studiesReference Piven, Chase and Landa 54 , Reference Dumas, Wolf and Fisman 55 reported an increased rate of anxiety and mood disorders among parents of ASD children when compared with parents of children with Down’s syndrome. Although the burden of raising an autistic child may partially explain the higher rate of psychiatric conditions in this group, it has been observed that this issue cannot account for the overall increased rate of mood disorders.Reference Bolton, Pickles and Murphy 56 , Reference Goussé, Galéra and Bouvard 57 Moreover, according to another study, the majority of depressed mothers of ASD children reported their first depressive episode before the birth of the child.Reference Micali, Chakrabarti and Fombonne 58 , Reference Ingersoll and Hambrick 59 In this framework, Ingersoll and Hambrick, highlighting an increased rate of depression in mothers of ASD children, hypothesized a role of AT in the development of mood symptoms.Reference Ingersoll and Hambrick 59 Several studies stressed also a high rate of social anxiety and obsessive–compulsive disorder among relatives of autistic probands,Reference Bolton, Pickles and Murphy 56 , Reference Piven and Palmer 60 – Reference O’Neill and Murray 62 leading to hypothesize that social anxiety and obsessive–compulsive traits may be considered as core features of BAP.Reference Micali, Chakrabarti and Fombonne 58 , Reference Piven and Palmer 60 It is interesting to note that social anxiety is a disorder which implies an impairment in social functioning, with strong neurobiological underpinnings,Reference Marazziti, Baroni and Giannaccini 63 , Reference Marazziti, Abelli and Baroni 64 and which is supposed to mask autistic-like symptoms especially among females, where ASD frequently remain undiagnosed.Reference Attwood 65 In this framework, it is noteworthy that a large body of evidence is stressing that mental rumination, as a maladaptive pattern of repetitive thinking which often impairs problem solving and negative emotion processing, may play a key role in the onset of different kinds of psychiatric disorders,Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky 66 – Reference Dell’Osso, Cremone and Carpita 68 increasing also the risk of suicide ideation and behaviors.Reference Dell’Osso, Gesi and Carmassi 36 , Reference Carbone, Miniati and Simoncini 39 , Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti 46 , Reference Teismann and Forkmann 69 , Reference Law and Tucker 70 Ruminative thinking is a dimension frequently associated with ASD and AT,Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti 46 , Reference Mayes, Gorman and Hillwig-Garcia 71 , Reference Dell’Osso, Gesi and Massimetti 72 which has been reported to possibly mediate the relationship between autistic-like traits and psychiatric symptoms.Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Cremone 42 However, this dimension has been poorly investigated among parents of children with ASD.

Although, as reported above, previous studies reported a higher frequency of different kinds of psychiatric disorders among parents of ASD probands, as well as autistic-like deficits in social communication and executive functioning, no study to the best of our knowledge has investigated the association between AT, ruminative thinking and global functioning (including clinical correlates) in parents of subjects with ASD.

In this framework, the aim of the present work was to investigate clinical and functional correlates of AT in a sample of parents of children with ASD, with a special focus on ruminative thinking. We hypothesized to find a high correlation between AT and rumination and an association of AT and ruminative thinking with a lower global functioning, as well as with a higher presence of psychiatric disorders. We also hypothesized that ruminative thinking may mediate the association between AT and the impairment in global functioning.

Methods

Subjects were recruited among parents of children (age range 18–72 months) with a diagnosis of ASD according to DSM-5, followed at the ASD unit of the Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS) Fondazione Stella Maris (Pisa, Italy). All the enrolled subjects were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 for investigating the presence of mental disorders according to DSM-5, as well as with the Adult Autism Subthreshold Spectrum (AdAS Spectrum), the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS), and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS). All participants received clear information about the study and had the opportunity to ask questions before they provided a written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki; the Local Ethics Committee approved all recruitment and assessment procedures.

Instruments

AdAS Spectrum

The AdAS Spectrum is an instrument developed and validated by Dell’Osso et al,Reference Dell’Osso, Gesi and Massimetti 72 with the aim to assess autism spectrum symptoms in adults with average intelligence and without language impairment. It has been tailored to evaluate not only overthreshold manifestations, but also a wide range of subthreshold, isolated or “atypical” features (including female-specific manifestations) such as those included in the BAP. The questionnaire is composed by 7 domains, for a total of 160 dichotomous items. The AdAS Spectrum has been proved to be highly correlated with other instruments in the field, such as the Autism Spectrum Quotient (Pearson’s correlation = 0.77). The instrument demonstrated also an excellent reliability (Kuder Richardson’s coefficient = 0.964).

RRS

The RRS is an instrument composed by 22 items, widely utilized in literature to investigate the presence of ruminative thinking. The items are grouped in 3 dimensions: reflection, brooding, and depression, and the answers are organized in a 4-point Likert scale. The RRS demonstrated an excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89).Reference Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 73 , Reference Parola, Zendjidjian and Alessandrini 74

SOFAS

The SOFAS is an observational instrument widely employed in literature to assess the level of social and occupational functioning in a continuum, with scores ranging from 1 to 100 (higher scores are associated with better functioning). It is specified that the impairment must be directly related to the psychiatric (or somatic) symptoms in order to be rated.Reference Goldman, Skodol and Lave 75

Statistical Analyses

We utilized Student’s t tests to compare the mean scores on AdAS Spectrum and RRS between males and females, between subjects with/without a psychiatric disorder, as well as between subjects with/without a history of school difficulties or a history of language development alterations. We performed a Pearson’s correlation coefficient in order to evaluate the association between AdAS Spectrum and RRS scores, between AdAS Spectrum and SOFAS scores, as well as between RRS and SOFAS scores. A multiple logistic regression analysis, with a single block entry (sex, AdAS Spectrum, and RRS domain scores were the independent variables), was employed to identify the best predictors of the presence of a psychiatric disorder. Moreover, multiple linear regression analysis was performed to identify the factors most predictive of SOFAS score, with sex, AdAS Spectrum, and RRS domain scores as independent variables (also in this case, all variables were entered as a single block). Finally, we performed a mediation analysis with AdAS Spectrum total score as predictor, SOFAS score as dependent variable, and RRS total score as mediator. The Hayes’s PROCESS tool was utilized; bootstrap confidence intervals and Sobel test for indirect effect were computed. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., 2017).

Results

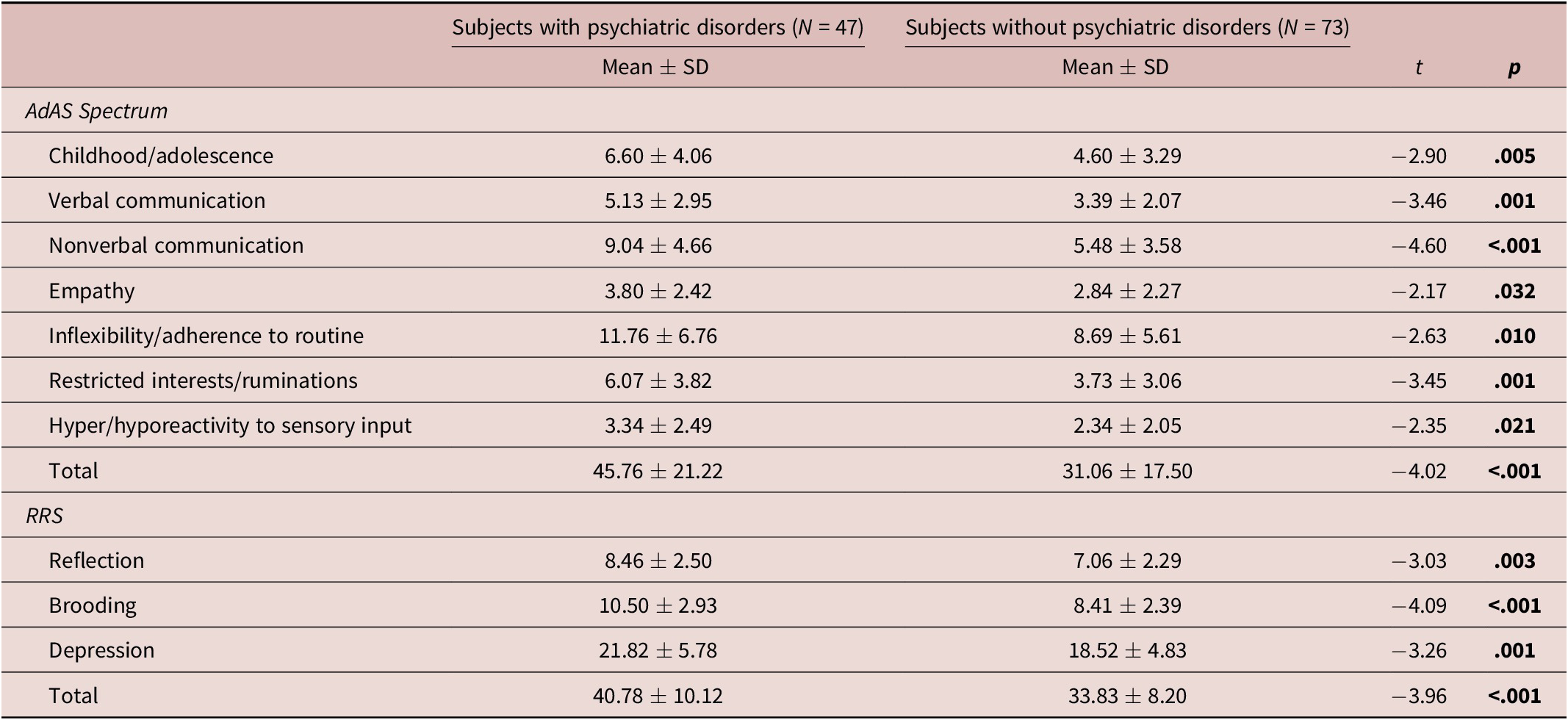

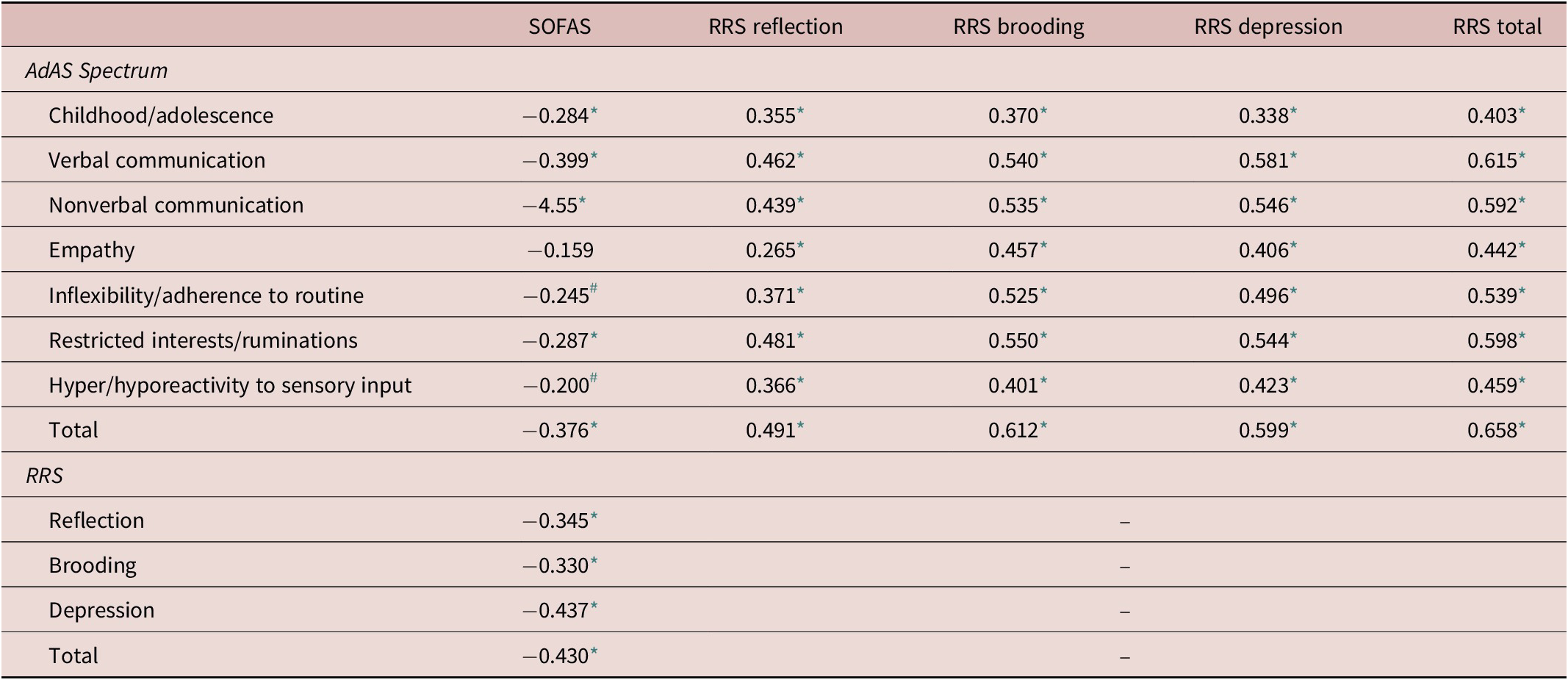

Our sample was composed by couples of parents of 60 ASD children, for a total of 120 subjects (60 males, 60 females) with a mean age of 39.82 ± 6.02. A total of 39.2% of the subjects reported a full-blown psychiatric disorder, whereas 15.8% of the subjects reported several comorbid psychiatric conditions. In particular, 11.7% of the subjects showed a bipolar disorder (N = 14), 17.5% (N = 21) a panic disorder, 25% (N = 30) other anxiety disorders, whereas 5.8% (N = 7) reported feeding and eating disorders. According to our data, 22.5% (N = 27) of the sample was employing psychopharmacological therapies. In particular, 11.6% of the total sample (N = 14) was taking only 1 drug: among them, 64.29% (N = 9) employed benzodiazepines, 7.14% (N = 1) antiepileptics and 28.57% (N = 4) antidepressants. Moreover, 10 subjects (8.33% of the whole sample) were taking both antidepressants and benzodiazepines. Finally, 1 subject was taking antidepressant and antipsychotics, and 2 subjects were treated with antidepressant, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines. We found an overall rate of 5.8% (N = 7) of previous school difficulties, while 8 subjects (6.7%) reported a history of alterations in language development. The mean score on AdAS Spectrum was 37.04 ± 20.35, while the mean score on RRS was 36.76 ± 9.65. No gender differences were found on AdAS Spectrum total and domain scores, while females scored significantly higher than males on RRS reflection subscale (8.10 ± 2.36 vs 7.18 ± 2.50; t = −1.998; p = .048). Subjects with a psychiatric disorder showed significantly higher AdAS Spectrum total and domain scores as well as significantly higher RRS total and domain scores (Table 1). Subjects with a history of school difficulties when compared to those without, reported significantly higher AdAS Spectrum total scores (61.14 ± 31.05 vs 35.45 ± 18.54, t = −3.38, p = .001), as well as significantly higher AdAS Spectrum childhood/adolescence (10 ± 4.69 vs 5.11 ± 3.49, t = −3.51, p = .001), nonverbal communication (11.86 ± 6.09 vs 6.601 ± 4.10.49, t = −3.18, p = .002), and inflexibility/adherence to routine (15.00 ± 9.02 vs 9.60 ± 5.95, t = −2.24, p = .027) domain scores, while they did not report higher RRS scores. Subjects with a language development alteration scored significantly higher only on AdAS Spectrum childhood/adolescence domain score (5.18 ± 3.50 vs 8.50 ± 5.45; t = −2.474; p = .015). We found significant correlations between all AdAS Spectrum and RRS total and domain scores (Table 2). Moreover, we found a significant negative correlation between SOFAS score and AdAS Spectrum total and domain scores, with the exception of AdAS Spectrum empathy domain score. The highest correlation was found between SOFAS and AdAS Spectrum nonverbal communication domain score (Table 2). Significant negative correlations were found also between SOFAS score and RRS total and domain scores (Table 2). We performed a multiple logistic regression analysis in order to identify the best predictors for the presence of psychiatric disorders, which is a categorical variable. Although multiple independent variables (in particular: sex, AdAS Spectrum, and RRS domain scores) were entered as possible predictors, our results identified only the female gender and AdAS Spectrum nonverbal communication domain score as predictive variables for the presence of a psychiatric disorder (Table 3). Moreover, we performed a multiple linear regression analysis with SOFAS score as the dependent continuous variable in order to evaluate possible statistically significant predictors of social and occupational functioning, including sex, AdAS Spectrum, and RRS domain scores as independent variables. The regression equation was significant (F[11, 93] = 3.676, p < .001), with R 2 = 0.303, and the model identified the AdAS Spectrum nonverbal communication domain score as the only significant predictive factor for a lower SOFAS score (Table 4). Finally, the significant negative correlations of both AdAS Spectrum and RRS total scores with SOFAS score (r = −0.38, p < .001, and r = −0.40, p < .001, respectively) as well as the significant positive correlation between AdAS Spectrum and RRS, suggested us to verify the eventual presence of a mediating effect of RRS total score on the relationship between AdAS Spectrum and SOFAS score. The mediation analysis showed a significant indirect effect of AdAS Spectrum total score on SOFAS score through RRS total score, b = −0.12, 95% bootstrapped 95% CI [−0.23, −0.04]; Sobel test showed b = −0.12, Z = −2.64, p = .008 for RRS total score. It is noteworthy that the mediation appears to be full because there was a significant total effect (b = −0.220, p = .001), but not a significant direct effect (b = −0.10, p = .152) of AdAS Spectrum total score on SOFAS score (Figure 1).

Table 1. Comparison between subjects with or without a psychiatric disorder on AdAS Spectrum and RRS scores.

Results statistically significant for p < .05 are in bold.

Table 2. Pearson’s correlation between AdAS Spectrum, RRS, and SOFAS scores.

* p < .005.

# p < .05.

Table 3. Multiple logistic regression analysis for predictors of psychiatric disorders. Results statistically significant for p <.05 are in bold.

Cox R 2 = 0.246; Nagelkerke R 2 = 0.331.

Results statistically significant for p < .05 are in bold.

Table 4. Multiple linear regression with SOFAS score as dependent variable.

Results statistically significant for p < .05 are in bold.

Figure 1. Mediation analysis results.

Discussion

The aim of the present work was to investigate clinical and functional correlates of AT and ruminative thinking in a sample of parents of children with ASD. The rates of psychiatric disorders in our sample are in line with those highlighted in previous literature, which stressed a higher presence of mood and anxiety disorders in parents of ASD children than in general population.Reference Goussé, Galéra and Bouvard 57 In particular, our sample showed a 11.7% rate of bipolar disorders, while the reported prevalence in the general Italian population is about 1%.Reference Faravelli, Guerrini Degl’Innocenti and Aiazzi 76 , Reference de Girolamo, Polidori and Morosini 77 However, we did not find any case of major depressive disorder (MDD), which is the most common mood disorder in the general Italian population, with a prevalence about 10%.Reference de Girolamo, Polidori and Morosini 77 Although previous studies reported higher rates of different kinds of mood disorders, including MDD, in parents of ASD children,Reference Goussé, Galéra and Bouvard 57 , Reference Ingersoll and Hambrick 59 our results are somewhat is in line with recent findings that suggested a specific association of autism spectrum with bipolar disorders, also from a genetic point of view.Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti 46 Moreover, while in the general Italian population the reported prevalence of anxiety disorders is about 11%, mainly represented by specific phobia (5.7%),Reference de Girolamo, Polidori and Morosini 77 we found in our sample a rate of 17.5% only for panic disorder (vs a prevalence of 2% in the general Italian population),Reference de Girolamo, Polidori and Morosini 77 and a 25% rate of other anxiety disorders. Finally, according to other studies that stressed higher rates of feeding and eating disorders among BAP subjects,Reference Carbone, Miniati and Simoncini 39 in our sample parents of ASD children showed a 5.8% rate of feeding and eating disorders, while in the general Italian population, the reported prevalence is about 0.6%.Reference Faravelli, Abrardi and Bartolozzi 78 Globally our results, in line with other studies,Reference Carbone, Miniati and Simoncini 39 , Reference Dell’Osso, Muti and Carpita 40 , Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Cremone 42 , Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti 46 seem to suggest an association between BAP and specific kinds of psychiatric disorders, although further researches in wider samples are needed to clarify this point.

The relatively high rates of school difficulties and language development alterations that we found in our sample, associated with significantly higher AT during childhood and adolescence, are in line with other studies that reported increased rates of delays in language development and pragmatic language alterations among relatives of ASD children.Reference Szatmari, MacLean and Jones 13 , Reference Briskman, Happe and Frith 24 , Reference August, Stewart and Tsai 79 Moreover, we found that higher AT were associated with the presence of psychiatric disorders, as well as to a lower global functioning. This result adds to previous data, which reported high levels of AT in different kinds of psychiatric disorders,Reference Dell’Osso, Muti and Carpita 40 – Reference Dell’Osso, Bertelloni and Di Paolo 47 as well as a higher frequency of psychiatric conditions in parents of subjects with ASD.Reference Bolton, Pickles and Murphy 56 , Reference Goussé, Galéra and Bouvard 57 Some studies in this field ascribed the higher rates of psychopathology in parents of ASD children to the extremely stressful experience of raising a child with ASD, which may be more severe than the stress of raising a child with different kinds of disorders, such as mental retardation.Reference Goussé, Galéra and Bouvard 57 , Reference Hastings 80 – Reference Hayes and Watson 82 In this framework, our data are in line to those of Ingersoll and HambrickReference Ingersoll and Hambrick 59 who reported that the presence of depressive mood in mothers of ASD children was directly related to their own BAP score (as measured by the Autism Spectrum Quotient), rather than to parental distressing. Previous studies variously highlighted also an impairment in social and occupational functioning among parents of ASD children, focusing in particular on the stress related to the diagnosis of their child.Reference Ooi, Ong and Jacob 52 When the child receives a diagnosis of ASD, the family unit must adjust to their new circumstances in a way that changes their life, including marital relationships, work arrangement, coping styles, and future perspectives.Reference Ooi, Ong and Jacob 52 However, according to our results, it seems that lower SOFAS scores were associated with higher AT: in this framework, we could also hypothesize a role of the BAP in the impairment of global functioning observed in this group, as reported in different populations.Reference Jobe and White 48 – Reference Suzuki, Miyaki and Eguchi 51 Both poor functional outcome and the presence of psychiatric conditions among parents of ASD children might be, at least partially, considered as a consequence of their own BAP traits.Reference Ingersoll and Hambrick 59 , Reference Ingersoll, Meyer and Becker 83 – Reference Pruitt, Rhoden and Ekas 85 BAP may act as a risk factor for the development of psychiatric symptoms, either directly, because mood and anxiety disorders may be considered as an associated feature of BAP, with which they share also a genetic liability, or indirectly: the presence of AT may be considered as a vulnerability factor for developing post-traumatic spectrum symptoms after stressful events, including also those related to the role of caregivers.Reference Carbone, Miniati and Simoncini 39 , Reference Dell’Osso, Muti and Carpita 40 Moreover, BAP features may imply more difficulties in reaching social support due to the impairment in social skills.Reference Carbone, Miniati and Simoncini 39 , Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Cremone 42 , Reference Pruitt, Rhoden and Ekas 85 Other features associated with BAP, in particular intolerance of uncertainty and sensory sensitivity, have been considered as a potential risk factor for the development and maintenance of affective problems in the general populationReference Aron, Aron and Jagiellowicz 86 – Reference McEvoy and Mahoney 88 as well as in ASD.Reference Wigham, Rodgers and South 89 , Reference Uljarević, Carrington and Leekam 90 Our results identify in the nonverbal communication problems (as measured by AdAS Spectrum), the statistically predictive dimension for the presence of psychiatric conditions, and poorer social and occupational functioning. These data are in line with a previous study, which stressed the link between autistic-like nonverbal communication impairment and suicide risk among university students.Reference Dell’Osso, Bertelloni and Di Paolo 47 It is noteworthy that social support seems to be a strong predictor of adjustment for parents of children with ASD,Reference Boyd 91 , Reference Benson and Kersh 92 while communication impairment may result in higher social isolation, with more difficulties in externalizing and processing emotions, leading to reach lower social support, thus increasing the vulnerability to psychopathology.Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Cremone 42 , Reference Dell’Osso, Bertelloni and Di Paolo 47 , Reference Pelton and Cassidy 93 , Reference Carmassi, Bertelloni and Salarpi 94 In our sample, we did not find gender differences with respect to AT. Several investigations reported an increased expression of some (but not all) BAP features among male relatives: in particular higher aloofness, rigidity, irritability, and sensitive traitsReference Murphy, Bolton and Pickles 11 as well as pragmatic language alterations.Reference Ruser, Arin and Dowd 95 Despite that, not all the studies have reported such differences,Reference Piven, Palmer and Landa 10 , Reference Losh and Childress 14 , Reference Landa, Piven and Wzorek 96 and our results seem to be in line with these latters. However, according to our data, female gender was a statistically predictive factor for the presence of psychiatric disorders, together with autistic-like nonverbal communication features. These data reflect results from other studies, which highlighted higher rates of psychopathology among females, including in samples composed by parents of ASD children.Reference Goussé, Galéra and Bouvard 57 In our sample, gender was not a predictive factor for the presence of a lower social and occupational functioning. Previous studies reported, among parents of ASD children, a lower functioning in mothers than in fathers, which was generally associated with higher levels of stress.Reference Dabrowska and Pisula 97 , Reference Al Kandari, Alsalem and Abohaimed 98 Although the role of gender differences on the impact of parenting stress is still controversial,Reference Ingersoll, Meyer and Becker 83 , Reference Carmassi, Corsi and Bertelloni 99 females often show, in different kinds of samples, a higher vulnerability to trauma- and stress-related symptoms.Reference Dell’Osso, Dalle Luche and Carmassi 100 , Reference Carmassi, Corsi and Bertelloni 101

Our data reported also a significant association between ruminative thinking and the presence of psychiatric disorders, as well as between ruminative thinking and lower global functioning. Mental rumination involves perseverative thoughts that revolve around a negative emotion or situation. As an unintended and involuntary process, rumination is often long lasting and may consume cognitive resources, leading to poorer outcome.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita 38 , Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky 66 These results confirm the wide amount of studies which stressed the role of rumination in promoting different kinds of psychopathology.Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky 66 – Reference Dell’Osso, Cremone and Carpita 68 On the other hand, ruminative thinking is a feature frequently associated with AT.Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Cremone 42 , Reference Mayes, Gorman and Hillwig-Garcia 71 , Reference Dell’Osso, Gesi and Massimetti 72 ASD patients frequently show also features like perseverance and repetitiveness, including pervasive rumination on specific subjects.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita 38 In a recent meta-analysis, it has been stressed that ASD patients often show difficulties in inhibitory control,Reference Geurts, Bergh and Ruzzano 102 a feature that seems to contribute, in this population, to increasing the tendency to rumination, in particular about negative emotional experiences, eventually implying a higher vulnerability toward depressive symptomatology.Reference Siegle, Moore and Thase 103 In this framework, our results, which stressed a significant correlation between AT and rumination as respectively measured by AdAS Spectrum and RRS, add to previous literature,Reference Carpita, Marazziti and Palego 4 confirming the strong link between those 2 dimensions. Moreover, it is noteworthy that, according to the mediation analysis, we found a significant effect of AT on the social and occupational functioning score; however, this effect was totally mediated by the presence of ruminative thinking. This result is in line with another study, which reported a mediating role of rumination in the relationship between AT and mood symptoms.Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Cremone 42 Globally, these data seem to further suggest a transnosographic role of rumination in the development of psychopathology and functional impairment in subjects with higher vulnerability.

This study suffers from several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design prevented us from clarifying the temporal, and eventually causal, relationship among AT, rumination, and global functioning or psychiatric symptoms development. Moreover, the AdAS Spectrum and the RRS are self-reported instruments, and patients may have over- or underestimated their own symptoms, eventually leading to the presence of biases in our results. This is an exploratory study conducted in a small sample and without a control group, mainly focused on psychopathological features chosen due to their known relationship with BAP. As a consequence, many demographic variables, other than sex, potentially involved in the relationship between AT and global functioning were not included in the study. In particular, according to previous literature, features such as marriage quality, access to social support, as well as the child symptom severity, may play a significant role in the level of adjustment among parents of ASD children.Reference Benson 81 , Reference Boyd 91 , Reference Benson and Kersh 92 We did not collect any kind of neuroimaging, genetic, or biochemical data, although literature stressed the role of different kinds of biological variables in determining BAP features. In particular, according to the most recent studies, specific attention should be provided in clarifying the role of neurostructural and neurofunctional characteristics, as well as the role of oxidative stress, immune system activation and gut microbiota profiles, in shaping specific BAP psychopathological features and trajectories.Reference Carpita, Muti and Dell’Osso 2 , Reference Carpita, Marazziti and Palego 4 , Reference Billeci, Calderoni and Conti 15 , Reference Dell’Osso, Del Grande and Gesi 104 , Reference Carmassi, Palagini and Caruso 105 Finally, pharmacological factors were not included in the analysis due to the small sample size and the high heterogeneity of treatments reported among the subjects. Further studies in wider samples and with a longitudinal design are warranted to clarify the relationship between AT, rumination, and both clinical and functional outcomes among parents of ASD patients.

Disclosure

The authors do not have anything to disclose.