Introduction

The virtuosic electric guitar movement is a topic most associated with prominent players of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, such as Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Eddie Van Halen, Yngwie Malmsteen, and Tony MacAlpine.1 Throughout their careers, these players pushed the technical and creative boundaries of the instrument, placing them at the center of the guitar studies literature that highlights their originality and influential legacy in electric guitar technique, equipment, and culture.2 In comparison, the contemporary movement—defined in this chapter as a network of artists conversing primarily online on Instagram and YouTube—has received far less scholarly attention despite continuing to push boundaries and explore new approaches to the instrument, its sound, and how and where guitar culture takes place. Guitarists such as Tosin Abasi of progressive metal band Animals as Leaders, Tim Henson of Polyphia, and Yvette Young of Covet are pioneers in the contemporary guitar movement with innovative techniques and approaches to the instrument. Just like their influential virtuosic predecessors, these newer-generation guitarists primarily make instrumental music, using their technical abilities equally harmonically, rhythmically, and melodically for the benefit of musical composition and displaying their virtuosity.

The main space where contemporary electric guitarists “meet” is Instagram and, by extension, YouTube (see also Daniel Lee’s Chapter 15 on online guitar communities). On these platforms, guitarists post videos of themselves playing short snippets of work-in-progress material to receive feedback, update their followers, or merely create content. Popular videos showcase juxtaposed techniques such as tapping, thumping, and natural harmonics in close succession and with challenging combinations, as seen in videos by Ichika Nito,3 one of the guitarists with the largest following on Instagram (750,000 followers) and YouTube (2.2 million followers)—considerably outnumbering established virtuosos such as Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, or John Petrucci. Short educational videos on technique and music theory are also popular. Instagram is a place where guitarists also network and initiate collaborations such as joint albums, tours, or cover versions.

The clips receiving the most attention have high-quality video and audio recordings, usually edited, mixed, and mastered by the performer. Next to the high-quality videos, the playing must, in most cases, display a certain degree of virtuosity to attract attention. Importantly, though, the fans consider artists popular in the scene to be not only virtuosic but also accomplished composers and producers.4 This more balanced relationship between technical and musical skills makes perhaps the difference to some earlier virtuosic movements in electric guitar history. Arguably, the Shrapnel “shred guitar” era in the 1980s (e.g. Yngwie Malmsteen, Paul Gilbert, Vinnie Moore, Tony MacAlpine, Jason Becker, Greg Howe, Richie Kotzen) focused more on the display of technical prowess than on the quality of musical compositions—in contrast to the first generation of rock guitar virtuosos in the 1960s and 1970s (including Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Ritchie Blackmore, Uli Jon Roth, Randy Rhoads, Eddie Van Halen, Frank Zappa), who were valued as much for their songwriting as for their technical capabilities. We argue that while contemporary players certainly flaunt their virtuoso skills, just as previous generations of virtuosos did, their technique tends to be employed to benefit the quality of the songs (some of which do not contain traditional solos), whereas the songs of the earlier “shred” era were sometimes mere placeholders for technically demanding solos in which there was a stark contrast between highly advanced soloing and comparatively simple rhythm playing.5

Lively exchange on social media afforded by the internet has generally become a trend in popular music.6 Instagram provides contemporary guitarists with an essential marketing tool, which most of them use to personalize their social platform for their fans by posting pictures of their partners and holidays. The platform creates seemingly personal relationships, as followers can ask questions about Instagram stories. By engaging with their fans, leading to imaginative bonding facilitated by social media, these musicians are breaking away from the aloof rock guitar hero of the past.7 Most followers are musicians themselves, in particular, guitarists. They fulfill a crucial role in the economic viability and success of artists they respect, who earn most of their professional income from streaming royalties and the sale of educational products or online lessons rather than traditional revenue streams such as concerts, merchandise, and record sales.8 Many of the figurehead guitarists on Instagram, such as Jack Gardiner and Matteo Mancuso, post videos of themselves playing their own music and improvisations to promote their educational products, such as downloadable video lessons and masterclasses, on services like Jam Track Central.

This chapter outlines advances in guitar playing techniques commonly practiced in the contemporary scene defined above. Some of the techniques presented have been developed specifically for the guitar or were adopted from other instruments such as the violin, piano, bass, and drums to facilitate compositional ideas. Less attention is given in this chapter to the gear used by contemporary players and how their choice of equipment helps them achieve novelty in electric guitar-centered music. By discussing several playing techniques, this chapter provides an overview of techniques rather than an in-depth analysis of a specific technique.

There are numerous artists worthy of discussion, but this chapter concentrates primarily on guitarists in the progressive rock and metal genres, as these are the dominant styles in the contemporary guitar scenes analyzed,9 and they are also genres in which virtuosic technique has historically been foregrounded. A peculiarity to be mentioned is that many guitarists and their work explored have prominent influences and compositional styles beyond rock music. The blending of genres is commonplace and may itself be understood as a mark of virtuosity that is perhaps less technical in nature but reflects the musicians’ intention to explore expressively and artistically in the spirit of progressive (rock) music. Some influential musicians such as Tosin Abasi refer to themselves only as “progressive,” arguing that the terms prog rock and metal fail to capture the genre-bending nature of the current scene, the inclusion of electronic sounds, and the aesthetics of computer-produced music.10 For Abasi, progressive is a “fundamental approach” that does not have to adhere to the conventions of established genres with specific traditions like prog rock. Other examples of progressive artists include Polyphia, one of the main artists discussed below, who use structural and production influences from Kanye West to Taylor Swift throughout their album New Levels New Devils (2018), evident in tracks such as “O.D.” (2018). Manuel Gardner-Fernandes of Unprocessed creates pop-oriented music with skillful guitar playing and vocals with catchy hooks, as heard in their track “Deadrose” (2020). Intervals draw particular stylistic inspiration from pop-punk influences that run throughout their discography from the album The Shape of Colour (2015) onward.

Sweep Picking

Sweep picking (also known as “sweeping”) is a technique that has been used throughout the history of the electric guitar, particularly since the 1970s. As a technique of performing notes on successive strings with a single downward or upward motion, sweeping has undergone various changes regarding mechanical approaches and compositional purposes. Notable guitarists such as Jason Becker, Tony MacAlpine, and Rusty Cooley have employed sweep picking extensively throughout their careers, mainly as a display of virtuosity.11 Nowadays, sweep picking has lost much of its impressive impact, as it has become a standard technique learned by most ambitious rock and metal electric guitarists within their first few years as players.

Sweep picking is mainly used to perform arpeggios at high speeds or to play a series of notes in a melody in quick succession. In order to understand nuanced approaches to contemporary sweep picking, one must be familiar with two fundamental mechanics. With Downward Pick Slanting (DWPS), the plectrum is slanted away from the performer; with Upward Pick Slanting (UWPS), the pick is tilted toward the player. Lead-edge picking involves angling the plectrum toward the lower horn of the guitar. These mechanics remove as much friction as possible and ensure the plectrum glides across the string without becoming stuck when sweep picking.

Jason Becker is known to be one of the most prolific guitarists playing sweep picking. Becker incorporated challenging sweeping passages throughout most of his music, such as in “Altitudes” (1988). Becker mainly utilized DWPS and UWPS, depending on the sweeping direction (ascending or descending), as seen in clips of him performing “Serrana” (1995).12 Becker also anchored his wrist on the topside of the bridge and turned it, muting the lower strings when not in use. Becker’s fretting hand outlined the arpeggio shapes, rolling over strings with the same finger if adjacent notes were on the same fret. Many guitarists, including Yngwie Malmsteen, prefer this approach, as heard in the intro to “Eclipse” (1990), and others from the Shrapnel era. John Petrucci of Dream Theater is another, more recent guitarist taking a similar approach, of which “Gemini” (2020) is an example. Instead of turning his wrist while sweeping, Petrucci’s hand moves slightly up and down to have greater control when muting the strings, which puts less strain on his wrist.13 Although these guitarists span different eras, their approach to sweep picking remains relatively similar, apart from details of wrist mechanics.

Jason Richardson is within the current group of guitarists pushing the technical limits of sweep picking. Richardson continues to use DWPS and UWPS with his picking hand, but instead of moving his wrist, Richardson moves his entire arm down while creating a fist with his picking hand to mute all the strings when sweeping. Using palm, wrist, and sometimes forearm when playing extended-range guitars, Richardson mutes the strings as he sweeps. The main difference to the fretting-hand approach is that the fingers reach adjacent notes without needing to roll over frets. Richardson prefers stacking his fingers to play the notes because, for him, this approach does not run the risk of notes ringing out over each other, turning an arpeggio into an interval or chord, and creating a sloppy impression.14

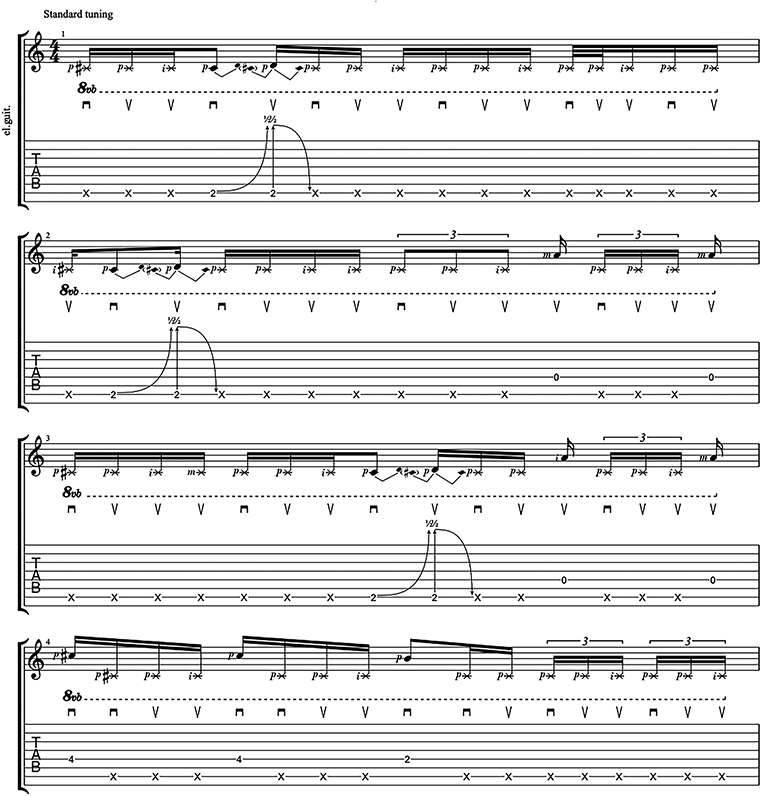

Nowadays, exclusively employing fast-paced sweep picking within an entire track section is no longer common. In the current scene, Tim Henson of Polyphia is a popular guitarist who, despite mastering sweep picking, uses the technique sparingly in his compositions. An example is the main riff/melody in “G.O.A.T.” (2018), with the riff using natural harmonics, hybrid picking, and sweep picking to enable him to play the technically demanding melody/riff (Figure 10.1). The sweep section of the guitar part is ascending only, and the technique is also used to connect two notes more than two octaves apart swiftly; in other words, sweeping facilitates a smooth transition between melodic ideas. Even contemporary shred guitarists no longer use sweeping exclusively to demonstrate virtuosity but to create emphasis or aid the transition between sections.

Manuel Gardner-Fernandes is another contemporary guitarist who uses sweep picking similarly favored by Henson. In “Right Hand King” (2021),15 Gardner-Fernandes performs sweep picking when no other instruments are playing to emphasize an arpeggio. In his collaborative cover with Tim Henson of Wiz Khalifa’s “In the Cut” (Henson, 2021),16 Gardner-Fernandes plays sweep picking to create a focal point toward the end of a section with little to no accompanying instruments, again to create emphasis but also to display his virtuosity (Figure 10.2). It should be noted with Gardner-Fernandes that the tone used for the above tracks is clean, whereas most guitarists sweep at high speeds with a compressed high-gain sound that connects all notes smoothly.17

Fast arpeggios can be performed in many ways without sweep picking, such as tapping the notes of the arpeggio on one string, as in Guthrie Govan’s “Wonderful Slippery Thing” (2006). There is also the approach of skipping strings and hammer-on arpeggio notes, popularized by Paul Gilbert.18 Overall, compositional approaches to arpeggios have changed considerably over the years. Today, sweeping is generally used for better realization of melodic ideas and less for the sake of sweeping itself and a display of technical skill, as was common in the 1980s and 1990s with artists such as Jason Becker and Yngwie Malmsteen. The mechanical approach to sweep picking has evolved, too, although not as much as with the other main electric guitar techniques discussed in the following sections. Among the principal developments are arguably the more musical application of techniques and the faster and cleaner execution, as seen, for example, in performances of Jason Richardson. In “Hos Down” (2016), he demonstrates hyper-clean and fast sweep picking and regular alternate-picking lines in continuation of the Shrapnel shred style (Figure 10.3). Other artists even sweep with a clean guitar tone to demonstrate their ability to articulate the technique flawlessly, as is the case with Polyphia’s “40oz” (2017).

Tapping

Tapping is another technique used by most contemporary virtuosic electric guitarists. It involves fretting notes on the fretboard with both hands, combining standard legato techniques (hammer-on, pull-off, slide) from the fretting hand with “hammer-ons from nowhere” from the picking hand to excite the string and perform a note at the same time. Eddie Van Halen is one of the most prominent guitarists associated with tapping, having popularized it during his career in Van Halen, although he did not invent the technique. Van Halen’s approach to tapping can be heard in tracks such as “Eruption” (1978) and “Hot for Teacher” (1984), performed with what might be described as “shred tapping,” utilizing the ergonomic mechanics of the technique to play legato faster than is possible with the fretting hand only. Since Van Halen’s influential releases, tapping has evolved into various forms. The general approaches are shred tapping, linear tapping, linear multi-finger tapping, pianistic tapping, and multi-role tapping.19 This section concentrates on the recent extension and refinement of the tapping technique.

Guthrie Govan is one of the recognized virtuosos in the tradition of Eddie Van Halen. Govan plays arpeggios by hammering on all notes with the fretting hand and one finger from the picking hand to extend the pitch range on one string. This technique lends itself to the definition of linear tapping, where the fretting hand taps on the fretboard in a nonrepetitive manner to achieve what the guitarist is aiming for—often, but not necessarily, speed. Yet some approaches such as linear tapping are also used as valuable tools for shaping articulation and tone, not just employing the picking hand to play the notes that the fretting hand cannot reach. Although Govan is capable of sweep picking as a solution to perform arpeggios, he nonetheless opts for the hammer-on tapping technique because it creates a fluid and bubbly quality that avoids the percussive sound of the pick attack, as Govan explains in a tutorial on his song “Wonderful Slippery Thing” (2006) (Figure 10.4).20

Figure 10.4 Linear tapping on multiple strings in Guthrie Govan’s “Wonderful Slippery Thing” (2006)

Bassists playing the Chapman stick usually dedicate one hand to performing the melodies and the other to the underlying harmonies. Although not so widely used, this approach to tapping, which could be described as pianistic tapping, was a milestone in the progression of tapping on the electric guitar. A notable performer of this technique, and a historically important artist for contemporary progressive rock and metal guitarists exploring tapping techniques, is jazz guitarist Stanley Jordan. As seen in his performance of “Treasures” (1987) on the Wall Street Journal live show,21 both hands are independent of each other, with each having an individual role (Figure 10.5). The melody and upper harmonies are the picking hand’s responsibility, while the fretting hand controls the lower harmonies and bass lines. Parachordal and orthrochordal are the two main hand positions of the picking hand: in the parachordal position, the picking-hand fingers are parallel to the strings; in the orthochordal position, they are perpendicular to the strings.22 Jordan uses the second, orthrochordal finger placement, allowing all fingers easier access to more frets.23

A technique similar to pianistic tapping is multi-role tapping. It is mainly performed by percussive acoustic guitar musicians such as Andy McKee in “Drifting” (2006), Jon Gomm in “Passionflower” (2020), and in Justin King’s “Knock on Wood” (2001). Multi-role tapping entails using both hands to perform all musical roles: the melody, inner harmonic voice, and bass movements. Another major difference to pianistic tapping is using “parachordal” finger placement, in which the picking-hand fingers are parallel to the strings, while the thumb is placed above the fretboard on the neck. One of the forerunners of multi-role tapping is Yvette Young of the band Covet. Young was a pianist and violinist before becoming a guitarist. Like Stanley Jordan, she approaches the guitar like a piano, using both hands on the fretboard. Young also fingerpicks while tapping, making it possible to add accents and utilize louder-sounding pull-offs to open strings. For multi-role tapping, open tunings are usually preferred. Open tuning is when the open strings of the guitar outline a chord; one of the most commonly used open tunings being DADGAD, which outlines a suspended Dsus4 chord. Open tunings produce a floating, almost atmospheric sound when using pull-offs and strumming with open strings, as Young does.

An example of multi-role tapping is the main riff of Covet’s “Ares” (2020), where both hands share the inner voices (Figure 10.6). Although the roles are shared, the bass notes are the fretting hand’s priority, and the melody is performed by the picking hand due to the ranges of the instrument to which the hands have easy access.

Figure 10.6 Multi-role tapping in Covet’s “Ares” (2020) in the second half of bars 1, 2, 5, and 6

Another guitarist using multi-role tapping is Marcos Mena of the band Standards, as demonstrated in Standards’ “Pineapple” (2019), which also incorporates “glitch tapping,” a technique discussed below (Figure 10.7).

Like sweep picking, multi-role tapping might be used almost exclusively throughout an entire song, as in Covet’s “Nautilus” (2015), but it is usually mixed with fingerpicking and other tapping techniques such as cross-over tapping—with the picking hand tapping on lower frets than the fretting hand, that is, the “crossing” of the arms—as heard in Standards’ “Special Berry” (2020).24 Regarding shred tapping and linear tapping, it is important to note that most guitarists prefer a saturated and compressed tone to gain the fluidity and compression that facilitates seamlessly connected notes,25 aiding the actual playing of the tune in turn. In contrast, guitarists exploring advanced tapping techniques such as multi-role tapping tend to opt for a clean (albeit compressed) sound, which benefits the performance in terms of the notes’ attack and sustain. It is common to use relatively clean, Telecaster-inspired tones, even when adding saturation, to ensure the clarity of sound needed for the open, fingerpicked notes or strummed notes.

The last approach to tapping covered in this chapter is percussive tapping, which includes a range of techniques. In percussive tapping, the guitarist creates rhythmic patterns or accentuation while displaying harmonic information. Josh Martin of Little Tybee, a rhythmic/percussive tapping pioneer, is one of the guitarists associated with this technique. In frequently uploaded reels and videos to Instagram and YouTube, he practices polyrhythmic exercises and encourages his followers to copy them or experiment with similar ideas. Among Martin’s preferred experimental techniques is butterfly tapping, with the guitarist tapping several frets with each hand simultaneously in different patterns (inspired by drum techniques like paradiddles) in a quick staccato fashion. Butterfly tapping can be heard throughout Little Tybee’s discography but stands out most in “Left Right” (2013) (Figure 10.8).

There are various educational videos by Josh Martin on YouTube26 and more behind the paywall on his Patreon—a website creators use for financial support by offering extra content to those who pay. Martin is also a pioneer in glitch tapping, tapping the same note on the same fret in quick succession with two to four different fingers of the picking hand in a staccato manner, creating a “glitch” effect.27 The technique is named after the glitchy sound that occurs when a television set lags and produces a short sound that repeats rapidly for half a second, or when a CD becomes stuck and creates a short segment that repeats until it continues. Glitch tapping produces a similar quality due to the lack of sustain. It can be heard in Standards’ “Pineapple” (2019) (Figure 10.7) and throughout Little Tybee’s discography. Few guitarists in the scene have embraced glitch tapping; to date, mainly followers of Josh Martin, like Standards’ Marcos Mena, post their approaches to exercises and riffs incorporating glitch tapping.

Butterfly tapping is commonly used in isolation, unlike glitch tapping, which is typically mixed with other techniques such as thumping,28 or other percussive techniques such as muted hammer-ons from nowhere.29 As noted throughout this section, various techniques may be employed for different effects and ease of playing. Shred and linear tapping generally aim for higher speed, accompanied and facilitated by an overdriven sound. These two types of tapping may be utilized alongside other techniques in a melodic line or as the only technique in a passage. Multi-role tapping is mixed with other techniques, especially picking-hand fingering, to avoid using a plectrum. What all guitarists discussed above have in common is that they were not taught tapping but acquired this technique by experimenting. Stanley Jordan and Yvette Young were originally pianists who wished to transfer a similar approach to the guitar, so they developed different styles and techniques through experimentation. The same applies for Eddie Van Halen’s approach to tapping, Guthrie Govan’s tapped arpeggios, and Josh Martin’s butterfly tapping technique.

Thumping

Thumping is a technique that is relatively new to the electric guitar, despite building on percussive techniques, such as Van Halen’s slap-tapping in “Spanish Fly” (1979), Buckethead’s slap-bass approach in “Robot Transmission” (1996), and amateur footage discoverable on YouTube. Popularized by and commonly associated with Tosin Abasi of Animals as Leaders, thumping has been explored in seemingly disparate musical styles throughout the contemporary electric guitar community. Inspired by the thumping technique of bassist Evan Brewer (who was taught by Regi Wooten) of his previous band Reflux, Abasi decided to apply this technique to the electric guitar.30 This decision set the mark for the entire Animals as Leaders discography, with standout tracks showcasing Abasi’s thumping technique, such as “The Woven Web” (2014) and “Backpfeifengesicht” (2018). Thumping has since been used in pop and EDM-influenced guitar-centered music by players like Kevin Blake Goodwin.31

The general mechanic of thumping is similar to how bassists slap/double thump and pop. The picking-hand thumb holds a thumb-up position when pushing through the string. That allows the string to be thumped by either turning the wrist or pushing through while moving the entire hand down. Once the first stroke is complete, the thumb is brought back up through the string to create a double thump, done again with either the wrist or arm. Since the second stroke of the thumping movement is generally weaker than the first, the thumbnail is used to achieve greater definition and clarity. After the double thump is complete, the fingers of the picking hand continue the overall rhythmic grouping the guitarist is performing, which can be achieved by keeping the fingers mostly stiff in a slightly opened claw shape. After the double thump is performed, the wrist turns, and the string is “fingerpicked” with the picking-hand fingers. The fingers create a short staccato effect by muting the string quickly after striking. Using just the index finger allows for a grouping of three; adding more fingers enables larger groupings. The double thump and the action of the fingers create what is now known as thumping.32

Abasi has musical influences that are rhythmically complex because he is heavily inspired by (proto-)djent bands such as Meshuggah. Djent is a progressive metal subgenre that utilizes odd meters and rhythmic groupings, as well as muted open strings, to create intricate rhythmic riffs. “The Woven Web” (2014) builds on this inspiration by using different thumped groupings to create a dry syncopated riff with accents in odd places (Figure 10.9). Open notes emphasize the accents further. On Animals as Leaders’ album Parrhesia (2022), thumping is employed in conjunction with drums in a different pattern for polyrhythms that create challenging segments of music. Following such patterns may be difficult for some listeners, yet they enrich the material through detail and complexity in a way typical of progressive rock. These polyrhythms can be heard in the tracks “Red Miso” and “Monomyth.”

Whereas Animals as Leaders base their riffs and sections of their music on thumping, other guitarists employ it as an ornamentation technique. Tim Henson has taken thumping in his own direction to create a personal style and explore new compositional approaches. In Henson’s “God Hand” (2020), for example, he solely performs the rhythmic sections with thumping (Figure 10.10).33

“Real” (2020) by Unprocessed is another example of this approach that features Tim Henson. As heard in these tracks, thumping is used not just rhythmically for syncopation and accented offbeats but also to outline chords and the overall harmonic movement. In the collaborative track “Sunset” (2022) by Henson, Plini, and Cory Wong,34 Tim Henson performs a solo in which he combines thumping with fingerpicking and slapping. This solo builds rhythmic interest and accentuation through sparingly used thumping. Compared to Abasi, Henson’s tone, although equally defined and precise, is completely clean, which is more in keeping with Henson’s (progressive) pop-oriented sound.

Thumping is predominantly performed on extended-range guitars with additional, usually lower strings that extend the instrument’s pitch range.35 Lower pitches and the required thicker strings lend themselves to an ideal thumping sound, as in the previously mentioned tracks. Marcos Mena and Tim Henson mainly thump on a six-string guitar with a clean compressed tone. In contrast, metal-oriented musicians such as Tosin Abasi tend to use a compressed, tight, overdriven tone on an extended-range guitar. Abasi and others have also experimented with tones that facilitate thumping. For example, blending the unique characteristics of two different amplifiers can create the ideal tone, that is, an aggressive, overdriven tone mixed with a clean low-end.36 Thumping has advanced to a technique used in various musical styles within contemporary guitar culture and continues to be explored. Percussive techniques are popular among more pop-oriented guitarists, such as Gardner-Fernandes’ quick-hand technique, Henson’s harmonic approach to thumping, or Martin’s glitch tapping. These artists have built on Tom Morello’s influential playing on Rage Against the Machine releases that opened up an alternative form of virtuosity focused as much on rhythmic effects as on more conventional elements of harmony and melody,37 for example, DJ-like turntable scratches and toggle switch effects on “Bulls on Parade” (1996).

Miscellaneous Techniques

The techniques to be discussed next have a relatively short history and are not yet widely used. They are included here to show ongoing creative explorations of physical approaches to the electric guitar. Such techniques, just like glitch tapping, could be considered niche or limited in their application, but they are explored throughout the contemporary electric guitar community, along with technological experimentation and innovation that supports playing and creativity.38

A recent movement in the exploration of electric guitar techniques is an approach called selective picking, practiced by Tosin Abasi, which combines the sound of picked notes with palm-muted hammer-ons from nowhere.39 Even though Abasi has used selective picking throughout the Animals as Leaders discography, he raised awareness when posting (now-removed) videos on YouTube, most notably during the Covid-19 pandemic, explaining and demonstrating the technique. He describes selective picking as “producing notes on the guitar, where I divide my left and right hand up … So if I wanna do a group of three [notes], I would actually hammer-on from nowhere the first note, and then two and three would be completed by my right hand.”40 Further to this definition, Abasi elucidates that the guitar must have low action to perform this technique, especially when muting the strings while hammering on from nowhere. Muting the notes when selective picking produces a percussive sound with a sharp attack. As with most techniques that utilize hammer-on from nowhere, the tone is usually compressed so that all notes have equal volume and attack.

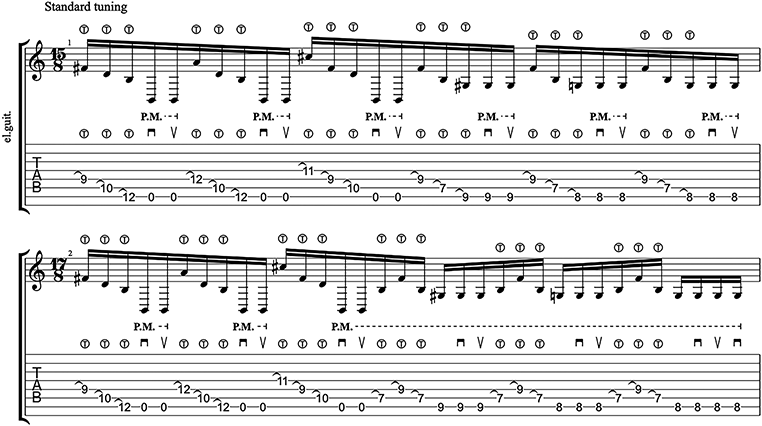

Abasi’s selective picking can be heard in Animals as Leaders’ “Kascade” (2014). After the solo intro on the strummed electric guitar, the main riff starts. This riff outlines different chords where all the notes except the root are hammered on from nowhere while the root note is alternate-picked (Figure 10.11). The first bar of the riff, in 15/8 time, has chords outlined in groupings of five, and the second bar, in 17/8 time, has various groupings. The root notes of the outlined arpeggio are also palm-muted for greater definition, with hammered notes not being muted.

Another track from Animals as Leaders where Abasi uses selective picking is “Monomyth” (2022). The selective picking passage is in the second section of the track; Abasi treats the B string as a “drone” by picking it with his middle finger throughout the ostinato while hammering on the other notes (Figure 10.12).

Concerning the use of thumbs, neither the left- nor right-hand thumb has much responsibility when it comes to general action on the fretboard. The picking-hand thumb may be used for thumping, strumming, holding the plectrum, and fingerpicking. The fretting-hand thumb’s main responsibility is to reach over the neck to play lower notes for particular chord voicings in the continued tradition of Jimi Hendrix. There are other uses for both thumbs that, although unconventional and not commonplace, allow for different sounds and chords voicings with unorthodox stretches.

A rather unusual use of the fretting-hand thumb is to treat it like a cellist when playing in the higher register of their instrument. As seen in live video footage of “Washington Is Next” (2008),41 Dave Mustaine uses the thumb to fret the 12th fret of the guitar while pulling off with his other fingers in order to stretch from the 12th to the 24th fret. Although this approach may seem somewhat gimmicky, as the 24th fret could just be tapped with the picking hand, Mustaine maintains alternate picking, which keeps the attack of the notes consistent. A more modern but niche approach utilizes the fretting-hand thumb to outline larger chord voicings, especially on extended-range guitars. Josh Martin demonstrates this in his piece “Thumbelina Etude” (2020),42 where he arpeggiates chords and frets using all fingers and the thumb on his fretting hand. In the same video, Martin gives credit to lesser-known guitarist Billy Jones for introducing thumb chords to him. Billy Jones is an avid user of thumb chords, as seen in videos on his YouTube channel.43

The picking-hand thumb is used for the previously mentioned techniques, but other techniques such as understrumming utilize it as well. Josh Martin developed this unconventional technique, which can be heard in Little Tybee’s “Tuck my Tail” (2016). Understrumming means holding a chord position with the fretting hand while adding extended voicings by fretting with the picking hand. When in this position, the thumb is brought under the picking-hand fretting fingers to strum the strings in a downward and upward motion.44

As evident in some of the previous examples, natural harmonics are used extensively in contemporary compositions. Natural harmonics can be found throughout Polyphia’s discography in tracks such as “Playing God” (2022), “G.O.A.T.” (2018), and “Goose” (2017). As with the tracks mentioned earlier, the contemporary approach to natural harmonics is to intertwine them within a riff or passage. The natural harmonics add coloration and draw attention to these riffs by creating different timbral moments. A track that uses natural harmonics in a riff is Chon’s “Bubble Dream” (2013). Here, guitarists Mario Camarena and Erick Hansel perform a melody with natural harmonics while playing the chords between the “melody” notes. Tapped natural harmonics are also used differently from playing the octave of a held note with high distortion. Tapped harmonics, such as practiced by Manuel Gardner-Fernandes,45 are used to outline chords but allow for a percussive attack from the tap while maintaining the floating character of the harmonics. Another track that utilizes this technique is Alex Vallejo’s “Otra Vez” (2022), where the arpeggios after the introduction are tapped for the compositional reason stated above.

Throughout the electric guitar’s history, special effects techniques have provided interesting or attention-grabbing sounds. Those techniques were not widely adopted, although some did gain popularity, including dive bombs, performed by Dave Mustaine, Dimebag Darrel, Steve Vai, and Joe Satriani. Herman Lee of Dragonforce employs various techniques, such as the “Pacman,” in which he repeatedly swipes the strings of the electric guitar on the pickups with a metal object, usually the whammy bar.46 Another classic effect is the race car emulation, as performed by Mick Mars of Mötley Crüe in “Kickstart My Heart” (1989).

Contemporary guitar-centered music widely ignores effects techniques, but the whammy bar remains popular for more nuanced and ornamental techniques. In “Every Piece Matters” (2016), Plini repeats the note by pushing down on the bar and immediately releasing it. Plini explains the advantages of the whammy bar in an interview with Guitar World, explicitly highlighting how it creates shape and adds motion to a melody when applied modestly; notes can be bent in and out that otherwise would prove difficult or unnatural to perform.47 Jeff Beck uses a similar technique extensively, as seen in the live performances of “Where Were You,” where he employs the whammy bar to reach different notes as soon as one is played, creating a legato sound reminiscent of a monophonic synthesizer. Delicate approaches to whammy bars are commonplace, as are more extravagant applications such as flutters. With flutters, the whammy bar points away from the guitar’s body and is struck to create strong, quick vibrations producing a flutter effect. Artists who use this frequently are Tim Henson and Scott LePage of Polyphia in tracks such as “LIT” (2017).

Conclusion

Listeners of mainstream popular and rock music and readers of scholarly guitar literature may not be aware of recent developments in the progressive contemporary guitar movement. Away from the mainstream spotlight, the scene experiments with playing techniques for compositional purposes and ergonomic reasons. Yet, anyone interested who has access to the internet can learn about these developments in social networks, that is, Instagram and YouTube, as well as other (subscription-based) platforms such as Patreon, Twitch, and Jam Track Central. The contemporary electric guitar space on social media is thriving, experimenting, and innovating. Guitarists’ posts span exercises, short explanations of their techniques, solo competitions, promotional material for their music, and clips about companies that sponsor them. Their experimental spirit contributes to the development and modification of guitar techniques, which expand the instrument’s expressive toolkit and enable compositions in which the guitar as the lead instrument can function rhythmically, harmonically, and melodically beyond the possibilities of established playing techniques. As the guitar scene flourishes, more techniques, new equipment, compositional methods, and unconventional uses of instruments come into being. Many of the guitarists discussed have signature instruments, amplifiers, and effects, or even their own equipment companies, such as Tosin Abasi with Abasi Concepts, offering equipment tailored to contemporary playing techniques.

To conclude this chapter, some reflections on virtuosity are in order to compare current trends with the history of rock guitar and to discuss the nature of contemporary rock guitar virtuosity. From a historical perspective, contemporary virtuosity appears to be both a recurrence and a further progression of earlier developments. As explored in more detail elsewhere,48 early rock guitar heroes in the 1960s and 1970s explored the potential of distortion and its expressive possibilities outside the idioms of the blues—importantly, not only for melodic playing but also for rhythm and songwriting. The 1980s saw explorations of technical prowess in the explicit pursuit of speed and progress in playing technique, turning songs into mere placeholders for solos and technically challenging lead ideas; a development that continued into the 1990s, albeit much less in the mainstream spotlight. As Steve Waksman notes, the dichotomy between technique versus emotion appeared to harden in the 1990s, leading to a “resurgence of punk values that occurred under the rubric of ‘grunge.’”49 According to Waksman, virtuosity was not completely replaced but rather transitioned into a new form that focused not on speed, physical dexterity, and spectacular melody lines but on “virtuosity of sound,” characterized by “ear-bending uses of noise … and atonal squalls of distortion that fell between the cracks of a song’s melody.”50

Contemporary rock guitar virtuosity seems to continue the legacy of all earlier forms of virtuosity. It harkens back to the 1960s and 1970s by focusing equally on solo and rhythm playing, and exploring the expressive potential of advances in instrumental technology (extended-range guitars, digital amplification, music production, and effects). Contemporary playing evidently takes up the “shred” tradition of the 1980s, striving for ever higher degrees of speed and more difficult ideas to perform. And it also draws inspiration from alternative forms of virtuosity in the 1990s and later, exploring playing techniques and means of expression that produce sounds not traditionally associated with the (electric) guitar, adopting ideas from other instruments and finding ergonomic ways to implement them on the guitar. Often these approaches highlight harmonic and rhythmic elements equally with the melodic chops traditionally pursued in virtuosic rock guitar playing. In the contemporary guitar scenes studied in this chapter, virtuoso players place a heightened emphasis on songwriting creativity and the ability to record, mix, master, and produce music as a more holistic approach to music-making, and as a way to cross genre boundaries in the spirit of progressiveness. Opponents of virtuosity criticize the one-sided focus on technique as an end in itself with little musical value.51 Proponents claim that technical skill and expressiveness are mutually dependent because technique is necessary to realize artistic feelings and visions, which is essential to exploring and shifting musical boundaries.52 Consequently, virtuosic pursuits may be authentically motivated by a “musical urge,”53 which may well be the case in the current guitar scenes.

A key feature of virtuosity is its inherent fascination throughout (rock) music history, from Jimi Hendrix to Ritchie Blackmore and Eddie Van Halen to Yngwie Malmsteen and Steve Vai and many others. According to Antoine Hennion, this fascination takes two forms.54 First, it is the transgression of what one thought possible, similar to the fascination of a magician, which allows for new experiences of sensation (and possibly, but not necessarily, musically ‘valuable’ novelty). Second, it is the spectacle of humans becoming automatons, making music with machine-like perfection. Both forms of fascination are evident in the contemporary rock guitar scenes observed. Perfection is expected, which has led to a culture of distrust and the need for artists to demonstrate the authenticity of their playing by being free of technological trickery afforded by digital audio and video production, especially given that the scene exists predominantly online, removing the traditional way of “authenticating” playing skills in a live context.55 There will certainly be no shortage of opinions about the musical value of the current explorations in playing technique. Some may dismiss them as technical exercises, providing contemporary artists with an opportunity to earn a living through social media and associated revenue in an era of dwindling sources of income for musicians. However, artistic curiosity and exploration of extended techniques are likely to expand the electric guitar’s expressive potential in the future and contribute to the further advancement of the instrument and the musical genres associated with it.