Introduction

Violence and aggression arise from a complex interaction of personal and environmental factors; however, treatment of the violent or aggressive individual often proceeds without an adequate consideration of the sources of the patient’s threatening or violent behavior. Furthermore, there are no recent published guidelines about how to assess and treat violence in an inpatient forensic or state hospital system, where most of the patients have diagnoses of psychosis, especially schizophrenia. That is, most published guidelines that discuss the treatment of violence or aggression are focused on one particular diagnosis, such as dementia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injury (TBI), borderline personality disorder, or intellectual disability.Reference Diaz-Marsa, Gonzalez Bardanca, Tajima, Garcia-Albea, Navas and Carrasco 1 – Reference Warden, Gordon and McAllister 12 The published guidelines that do address treatment of violent or aggressive behaviors in a more general sense and across a variety of diagnostic categories were all published nearly a decade or more ago, the most recent being published in 2007.Reference Allen 13 – Reference Wong, Gordon and Gu 17 Since the publication of these guidelines, many advances in psychopharmacology have occurred, not the least of which is the introduction of several additional antipsychotic agents.

Recent research has also suggested that among psychiatric inpatients, personal factors leading to aggression and violence commonly fall into several broad categories, including psychotic persecutory distortions of reality, increased impulsivity, and antisocial (predatory) personality features, with substance abuse and cognitive impairment frequently playing aggravating comorbid roles with the other domains.Reference Dack, Ross, Papadopoulos, Stewart and Bowers 18

Environmental factors may also exert significant influences on the risk of aggressive or violent behavior. While it is recognized that, in many patients, more than one personal or environmental factor may be operative, it is the aim of these guidelines to ask the clinician to generate a data-driven hypothesis regarding the principal or proximate factors that promote the individual’s aggression or violence, and then to provide a roadmap for the further evaluation and treatment of the patient. These guidelines make the assumption that a logical, step-wise process of data collection, data analysis, and evidence-based treatment will maximize the probability of resolving or ameliorating the treated person’s risk of violent behavior.Reference Howland 19

These guidelines were written for a presumed clinical environment in which, based on level of risk and probable resistance to treatment, the patient may be moved to higher or lower levels of secure care, from a regular hospital unit to an enhanced treatment unit and then to less secure treatment settings as the danger of violence and aggression declines.Reference Kennedy 20 In order to ease the use of these guidelines in clinical practice, they are presented in a bulleted format with numerous tables and treatment algorithms (many available in the online Supplemental Material).

Overview and Key Points

-

∙ Determine type of aggression (psychotic, impulsive, predatory) as well as environmental factors that may exacerbate aggressive behaviors

-

∙ Actively monitor for and treat comorbid conditions that may contribute to aggressive behavior, including substance abuse

-

∙ Continually evaluate patients using violence risk assessment tools

-

∙ Integrate psychosocial therapies into the treatment plan for patients who are chronically aggressive

-

∙ Actively monitor therapeutic drug levels during treatment

-

∙ Strongly consider using high dose antipsychotic monotherapy or antipsychotic polypharmacy in patients who are aggressive and violent

-

∙ Strongly consider clozapine for patients with persistent aggression

Assessment

Determine etiology of aggressive behavior

● Evaluate patient for causes of aggressionReference Vaaler, Iversen, Morken, Flovig, Palmstierna and Linaker 21

○ Aggression typeReference Bandura 22 – Reference Hemphill, Hare and Wong 24

■ PsychoticReference Volavka and Citrome 25

● Patient misunderstands or misinterprets environmental stimuli

● Attributable to positive symptoms of psychosis

○ Paranoid delusions of threat or persecution

○ Command hallucinations

○ Grandiosity

● Accompanied by autonomic arousal

■ Impulsive

● Hyper-reactivity to stimuli

● Emotional hypersensitivity

● Exaggerated threat perception

● Involves no planning

● Accompanied by autonomic arousal

■ PredatoryReference Hare and Neumann 26

● Planned assaults

● Goal-directed

● Lack of remorse

● Autonomic arousal absent

○ Physical conditions that may contribute to violence riskReference Hankin, Bronstone and Koran 27

■ Psychomotor agitation

■ Akathisia

■ Pain or physical discomfort

■ Delirium

■ Intoxication or withdrawal

■ Complex partial seizures

■ Sleep issues

○ Abnormal laboratory results that may contribute to violence riskReference Joshi, Krishnamurthy, Purichia, Hollar-Wilt, Bixler and Rapp 28

■ Plasma glucose

■ Plasma calcium

■ White blood cell count to rule out sepsis

■ Infectious disease screens as clinically indicated

■ Plasma sodium to rule out hyponatremia or hypernatremia

■ Oxygen saturation as clinically indicated

■ Serum ammonia as clinically indicated

■ Thyroid status

■ Sedimentation rate if history of inflammatory disease

○ Adverse medication effects

■ Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS)

● Akathisia

● Dystonia

● Parkinsonism

■ Sedation

■ Orthostasis

■ Adverse anticonvulsant effects

● Ataxia

● Tremor

● Cognitive impairment

■ Adverse lithium effects

● Polyuria

● Tremor

● Cognitive impairment

■ Adverse beta blocker effects

● Hypotension

● Bronchospasm

● Bradycardia

○ Environmental factors that may contribute to violence riskReference Wortley 29

■ Physical environmentReference Gadon, Johnstone and Cooke 30 – Reference Zaslove, Beal and McKinney 32

● Regulation of daily life/activities

○ Meals, medication, showers, etc. on a fixed schedule

○ Personal choices about attire, food, and leisure time are limited

○ All actions supervised

● Waiting in line required

● Limited privacy

○ Shared bedrooms/bathrooms

● Crowded communal areas

● Conversely, constant monitoring and structured activities may be beneficial for decreasing violence

■ Treatment unit factors

● Younger age of unit populationReference Ekland-Olson, Barrick and Cohen 33 , Reference Mabli, Holley, Patrick and Walls 34

● Unsafe population mixReference Cooke and Wozniak 35

○ Unit population is unadjusted according to violence risk, age, and diagnoses of patients

● CrowdingReference Gadon, Johnstone and Cooke 30 , Reference Ekland-Olson 36 – Reference Palmstierna, Huitfeldt and Wistedt 38

● Poor unit managementReference Flannery, Hanson, Penk and Flannery 39 – Reference Flannery, Staffieri, Hildum and Walker 44

○ Unreliable schedules and routines

○ Staff roles not clearly defined

○ Poor teamwork among staff

○ Absence of a committed and active psychiatrist/leader

○ Poor therapeutic alliance between patient and staff

○ Lack of therapeutic activities

○ Sensory overload from excessive noise

● Lack of a sense of community/therapeutic communityReference Mistral, Hall and McKee 45

■ Staff factorsReference Cooke and Wozniak 35 , Reference Flannery, Hanson and Penk 43 , Reference Flannery, Staffieri, Hildum and Walker 44 , Reference Flannery, White, Flannery and Walker 46 – Reference Webster, Nicholls, Martin, Desmarais and Brink 49

● Inexperienced staff

● Shift and unit staff assignments are unadjusted for experience levels of staff

● Understaffing

● High turnover of staff

● Inadequate or improper staff trainingReference Stewart, Van der Merwe, Bowers, Simpson and Jones 50 , Reference Bowers, Stewart and Papadopoulos 51

● Noncompliance with risk-reducing policies and procedures

● Overtime shifts

● Lack of discipline for staff who show a repetitive pattern of poor quality relationships with patients

● Staff burnout (Supplemental Table 4)

■ Institutional factorsReference Cooke and Wozniak 35

● Limited ability of staff to quickly access risk-relevant patient information

● Lack of an effective crisis management plan

● Poor managementReference Reisig 52

○ Failure to resolve conflicts among staff members

○ Senior management absent from treatment units

○ Absence of a designated person in charge of violence management

○ Incomplete or inaccurate written policies related to aggressionReference Mistral, Hall and McKee 45 , Reference Templeton, Gray and Topping 53

○ Acceptance of risky current practices

● Lack of transfer options for patients who are too dangerous to be housed in current facility

■ Schedule factorsReference Jayewardene and Doherty 54 – Reference Hunter and Love 60

● Unstructured activities

● Periods of transition, patient movement, patient lines, high-volume patient–staff interactions

Violence risk assessment

● Areas of elevated social interaction and physical proximity (eg, hallways)Reference Bader, Evans and Welsh 56 , Reference Hodgkinson, McIvor and Phillips 58 , Reference Harris and Varney 61

● Violence risk assessment should include a systematic collection of patient information and documenting of violence risk factorsReference Heilbrun and Lander 62 , Reference Maden 63

● Violence risk assessment should include both

○ Validated violence risk assessments

○ Structured clinical judgment processes

● Violence risk assessment should be conducted by a credentialed mental health professional

○ With specialized education and supervised training in the use and limitations of psychological assessment instruments and structured clinical judgment processes

○ Who completes ongoing training to maintain expertise in the use of violence risk assessments

● Review prior history and assessments

○ Frequency of violence

○ Severity of violence

○ Patient factors associated with violence

○ Environmental factors associated with violence

○ Cause of latest decompensation

○ Comorbid factors associated with violence

■ Psychosis

■ Substance abuse

■ Criminal thinking/psychopathy

■ Emotional instability

■ Borderline personality disorder

■ Intellectual disability

■ Traumatic brain injury

○ Evaluate previous treatments and treatment efficacyReference Lopez and Kane 64

○ Review all incident reports, progress notes, laboratory reports, prior psychological and neuropsychological testing results, treatment team documents, and court records

○ Include collateral reports of previous violence incidents, if available

○ Interview treatment team members and level-of-care staff

○ Conduct a clinical interview with the patient including a full mental status examination

● Supplementary assessment tools (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2)

○ Structured professional judgment violence risk assessment instruments

■ Historical Clinical Risk Management-20 (HCR-20)Reference Douglas, Hart, Webster and Belfrage 65

■ Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START)Reference Webster, Martin, Brink, Nicholls and Desmarais 66

■ Violence Risk Screening-10 (V-RISK-10)Reference Bjørkly, Hartvig, Heggen, Brauer and Moger 67

○ Psychopathy

■ Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R)Reference Hare 68

■ Psychopathy Checklist-Short Version (PCL-SV)

○ Actuarial violence risk assessment instruments

■ Classification of Violence Risk (COVR)Reference Monahan, Steadman and Robbins 69

■ Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG)Reference Dolan, Fullam, Logan and Davies 70 , Reference Quinsey, Harris, Rice and Cormier 71

■ Violence Risk Scale (VRS)Reference Wong and Gordon 72

○ Observational rating scales and checklists

■ Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression (DASA)Reference Vaaler, Iversen, Morken, Flovig, Palmstierna and Linaker 21 , Reference Ogloff and Daffern 73

■ Staff Observation Aggression Scale-Revised (SOAS-R)Reference Nijman, Muris and Merckelbach 74

■ Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire

■ Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

■ Cohen–Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI)

● If patient poses an immediate threat

○ Evaluate need for seclusion or restraint

■ Clinical observation

■ Clinical interview

■ Use of rating scales (eg, DASA)

Treatment

● Treatment of acute agitation (Figure 1)Reference Marder 75 , 76

Figure 1 Treatment algorithm for acute agitation.

○ When possible, choose an antipsychotic that is also being used as part of the primary treatment. Available dose forms may limit this option

○ Recent studies have suggested that additional agents, such as midazolam and promethazine, may play adjunctive roles in controlling acute aggression and violenceReference Huf, Alexander, Allen and Raveendran 77 – Reference Nobay, Simon, Levitt and Dresden 80

● Long-term treatment

○ Note that absence of any adverse effects despite adequate plasma concentrations of antipsychotics may reflect a need for higher-than-standard doses to achieve adequate receptor occupancy (Tables 1 and 2)

Table 1 Dosing recommendations: conventional antipsychotics

See full prescribing information for details.

Table 2 Dosing recommendations: atypical antipsychotics

See full prescribing information for details.

○ A partial response (<20–30% on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [PANSS] or BPRS) with minimal or no adverse effects argues for a higher-dose trial of the present antipsychotic

○ Failure of 2 or more adequate trials of antipsychotics, with at least one being an atypical antipsychotic, argues for a trial of clozapine

○ Tailor treatments to target specific symptoms that may contribute to violence risk (Table 3 and Figure 2)

Figure 2 Adjunctive medications for the treatment of symptoms that may increase risk of aggression.

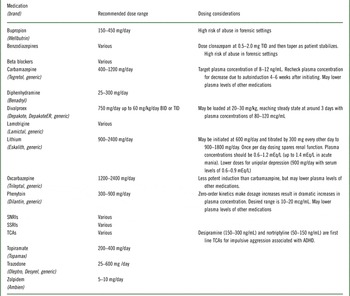

Table 3 Dosing recommendations: other medications

See full prescribing information for details.

○ There are a variety of pharmacokinetic and drug–drug interaction effects of the anticonvulsants, lithium, and beta blockers that should be consideredReference Silver, Yudofsky and Slater 81

■ eg, phenytoin with zero-order kinetics

■ eg, carbamazepine induces CYP450

■ eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) raise lithium levels

■ eg, nonselective beta-blockers are contraindicated in asthma

○ A partial response (small decline in Barratt Impulsiveness Scale [BIS-11]) with adequate anticonvulsant plasma concentrations argues for the addition of an anticonvulsant or other medication with a mechanism of action distinct from that of the primary treatmentReference Stanford, Anderson, Lake and Baldridge 82 , Reference Stanford, Mathias, Dougherty, Lake, Anderson and Patton 83

Psychotic aggression

● Confirm that the patient’s violent and aggressive behaviors arise primarily from psychosis

○ Associated with a primary psychotic disorder (Figure 3)Reference Buscema, Abbasi, Barry and Lauve 2 , Reference Castle, Daniel, Knott, Fielding, Goh and Singh 3

Figure 3 Antipsychotic treatment algorithm for long-term care of patients with psychotic aggression.

■ Schizophrenia spectrum disorders

■ Bipolar spectrum disorders

○ Associated with a major cognitive disorder (Supplemental Figure 1)Reference Herrmann, Lanctôt and Hogan 4 , Reference Oliver-Africano, Murphy and Tyrer 7 , Reference Vickland, Chilko, Draper, Low, O’Connor and Brodaty 10 , Reference Vickland, Chilko, Draper, Low, O’Connor and Brodaty 11

● Alzheimer’s diseaseReference Azermai, Petrovic, Elseviers, Bourgeois, Van Bortel and Vander Stichele 84

● Vascular dementia

● Major cognitive disorder with Lewy bodies

● Traumatic brain injuryReference Warden, Gordon and McAllister 12

■ Antipsychotics increase the risk of mortality by 1.5- to 2-fold in elderly demented patients but may be worthwhile if alternative choices to control agitation and violence are ineffectiveReference Langballe, Engdahl, Nordeng, Ballard, Aarsland and Selbæk 85 , Reference Ballard and Corbett 86

■ Periodically test whether antipsychotic dose is required to maintain stability

■ It is recommended that antipsychotics be tapered and discontinued after major cognitive disorders have stabilized or progressed

● Note that, although no response by weeks 4–6 of adequate to high-dose antipsychotic treatment portends a poor outcome, many patients show ongoing improvement for many weeks to months following a favorable, albeit partial, response to early treatmentReference Ruberg, Chen and Stauffer 87

● Some patients may require higher than cited antipsychotic plasma concentrations to achieve stabilization (Tables 1 and 2)

Impulsive aggression

● Confirm that patient’s violent and aggressive behaviors result primarily from impulsive aggression

○ Characterized by reactive or emotionally charged response that has a loss of behavioral control and failure to consider consequences

○ Associated with

■ Schizophrenia spectrum disorders

■ Cognitive disordersReference Tombaugh 88

■ ADHD (Supplemental Figure 2)Reference List and Barzman 5 , Reference Erhardt, Epstein, Conners, Parker and Sitarenios 89

■ Bipolar disorder (Supplemental Figure 3)Reference Ketter 90 – Reference Grunze, Vieta and Goodwin 100

■ Depressive disorders (Supplemental Figure 4)Reference Osterberg and Blaschke 101 – 114

■ Cluster B personality disorders (Supplemental Figure 5)Reference Jones, Arlidge, Gillham, Reagu, van den Bree and Taylor 115 , Reference Frogley, Anagnostakis and Mitchell 116

■ Intermittent explosive disorder (Supplemental Figure 6)Reference Stanford, Anderson, Lake and Baldridge 82

■ PTSD (Supplemental Figure 7)Reference Taft, Creech and Kachadourian 8

■ TBI (Supplemental Figure 8)Reference Warden, Gordon and McAllister 12

■ Unknown origin (Supplemental Figure 9)Reference Silver, Yudofsky and Slater 81 , Reference Stanford, Anderson, Lake and Baldridge 82 , Reference Butler, Schofield and Greenberg 117 – Reference Takahashi, Quadros, de Almeida and Miczek 120

○ Strongly associated with substance use disorders

○ Past history of psychological trauma increases risk of impulsive aggression and is often comorbid with substance use disorders and personality disorders

○ For mood disorders, the goal of treatment is resolution of the mood symptoms, or improvement to the point that only 1 or 2 symptoms of mild intensity persist

■ Resolution of psychosis is required for remission

○ For patients with mood disorders who do not achieve remission, a reasonable goal is response that entails stabilization of the patient’s safety and substantial improvement in the number, intensity, and frequency of mood (and psychotic) symptomsReference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer 121

Predatory aggression

● Confirm that patient’s violent and aggressive behaviors result primarily from predatory aggression

○ Purposeful, planned behavior that is associated with attainment of a goal

○ Some patients who engage in predatory acts may have the constellation of personality traits commonly known as psychopathy

● Avoid countertransference reactions (Supplemental Table 3)

● Determine potential reasons for predatory aggression (Supplemental Table 4)Reference Douglas, Hart, Webster and Belfrage 65 , Reference Hare 68 , Reference Dolan, Fullam, Logan and Davies 70 , Reference Hart, Cox and Hare 122

● Provide opportunities to attain acceptable goals using social learning principles, differential reinforcement, and cognitive restructuring (Figure 4)Reference Hare 123

Figure 4 Treatment algorithm for predatory aggression.

● Utilize the Risk–Need–Responsivity principles to determine risk level, treatment needs, and the best way to deliver and optimize treatment (Supplemental Tables 5 and 6)

● Regularly evaluate the progress of predatory aggression treatment (Supplemental Table 7)Reference Ross and Ross 124

● Consider using mood stabilizers, SSRIs, or other antidepressants for persistent tension, explosive anger, mood swings, and impulsivity

● While level of security and psychosocial interventions remain the mainstays of addressing predatory violence, preliminary data have suggested that clozapine also may reduce such aggression and violenceReference Brown, Larkin and Sengupta 125

Psychosocial Interventions

● It is often the case that when treating the violently mentally ill, both medications and therapeutic interventions are needed in order to impact change

● Pairing medication with appropriate psychosocial interventions can impart new coping strategies and increase medication adherence

● Psychosocial interventions should also give weight to the etiology of the aggression

○ Once an etiology has been identified, a behavioral treatment must be further individualized based on the patient’s needs, capabilities, and other logistical limitations

● Utilize the Risk–Need–Responsivity Model (Supplemental Table 6)Reference Bonta and Andrews 126 – Reference Hanson, Bourgon, Helmus and Hodgson 128

○ Risk principle

■ Assessment of patient’s level of risk and contributing factors to his or her aggressive behavior

○ Need principle

■ Assessment of criminogenic needs

● In this context, criminogenic needs refer to dynamic (treatable) risk factors that are correlated with criminal behavior, and when treated, reduce recidivism

■ Provides specific targets for treatment to reduce violence

● Early antisocial behavior

● Impulsive personality patterns

● Negative criminal attitudes and values

● Delinquent or criminal associates

● Dysfunctional family relationships

● Poor investment in school or work

● Little involvement in legitimate leisure pursuits

● Substance abuse

○ Responsivity principle

■ Individually tailor treatments to maximize the patient’s ability to learn from the interventions

● Intervention is tailored toward the patient’s

○ Learning style

○ Motivation

○ Abilities

○ Strengths

● Offer high-standard training on de-escalation and prevention strategies such as awareness of one’s presence (body posture), content of speech, reflective listening skills, negotiation, positive affirmation, and offering an alternative solution

● Provide supportive and nonjudgmental briefing sessions to staff who are involved in incidents to discuss their subjective experience

Psychosocial interventions for psychotic aggression

● General factorsReference Douglas, Nicholls and Brink 129

○ Good communication is essential

○ Multiple and coordinated treatment approaches should be used, including administrative, psychosocial, and psychotropic approaches

○ A sufficient dose of the selected treatment should be administered

○ Treatment integrity, including well-trained staff, supportive administration, and well-coordinated evaluation efforts, is vital

○ Treatment should be tailored to the individual

○ There should be a clear connection between risk assessment and treatment

● Specific interventions have some evidence for efficacy in reducing violence associated with mental illness

○ Using cognitive behavioral methods

■ Behavioral modification–reinforcement

● Unit and individual reinforcement

■ Group therapy

● UCognitive therapy for psychotic symptoms

● UAnger management

● UTeaching cognitive and problem solving skills

○ Individual therapy

■ Can use various approaches

■ Focus on reality testing

■ Building alliance

○ Social learning

■ Modeling by staff

○ Social learningReference Beck, Menditto, Baldwin, Angelone and Maddox 130

■ Teaching cognitive and problem solving skills

■ Using behavioral methods

○ Anger managementReference Becker, Love and Hunter 131 , Reference Stermac 132

○ Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)Reference Evershed, Tennant, Boomer, Rees, Barkham and Watsons 133

■ Associated with reduction in severity but not in frequency of violence in the mentally ill population

○ Seclusion

■ For up to 48 hours but not less than 4 hours

■ It is worth noting that anecdotal evidence suggests that some patients may respond to preventative interventions, such as time-outs, or to shorter periods of seclusion

■ Most experts caution against using methods that may seem punitive

○ Institutional approaches

■ Total quality managementReference Hunter and Love 60

● Including rewarding good behavior and changing the environment

■ Identifying the most aggressive individuals and targeting them for intense treatmentReference Drummond, Sparr and Gordon 134

■ Social structures that provide strong clinical leadershipReference Katz and Kirkland 41

■ A predictable, competent, interactive, trusting environment

■ Intrapsychic humanismReference Carroll and Tyson 135

Psychosocial interventions for impulsive aggression

● The goal of treatment is to increase behavioral control and decrease emotional dysregulationReference Shelton, Sampl, Kesten, Zhang and Trestman 136

○ DBTReference Rizvi and Linehan 137 , Reference Berzins and Trestman 138

■ Established as a validated treatment for borderline personality disorder and self-injurious behavior

○ Reinforcement/behavioral interventions

○ Positive coping

○ Individual therapy: exploration of impulsive episodes, coping, and triggers

○ Group therapy: anger management and social skills

● Psychosocial interventions for impulsive aggression with a trauma component:

○ Past history of psychological trauma increases risk of impulsive aggression and is often comorbid with substance use disorders and personality disorders

○ Treatments that incorporate trauma-informed strategies may be effective for impulsive aggression that is not responsive to other interventionsReference Flannery, Singer, Van Dulmen, Kretschmar and Belliston 139 – Reference Zlotnick, Najavits, Rohsenow and Johnson 148

○ Previous experiences of victimization often lead to difficulties in forming close relationships and ineffective coping strategies

○ Special emphasis on safety and therapeutic alliance

○ May be incorporated into many existing treatments, especially treatments for ongoing mood disorders or substance use disorders

○ In the case of trauma, be mindful of restraint conditions, which may re-traumatize

○ Exposure therapy may be useful for aggression stemming from PTSD or other traumatic experiences

● More intensive and specialized treatment may be required for severely ill patients or those with chronic coping deficits or personality disorders

Psychosocial interventions for aggression due to cognitive impairment

● Psychosocial interventions for aggression due to cognitive impairment

○ Cognitive impairment is found consistently in serious mental illness, especially schizophreniaReference Heinrichs and Zakzanis 149 – Reference Keefe and Fenton 151

○ Addressing complex aggressive behavior and cognitive issues should be the target of treatment

○ Recovery Inspired Skills Enhancement (RISE)

■ Multifaceted neurocognitive and social cognition training program for individuals with psychiatric disorders and severe cognitive needs and challenges

■ Goal of RISE is to eliminate maladaptive behaviors that interfere with an individual’s recovery process and acquisition of skills necessary for adaptive functioning

Psychosocial interventions for predatory aggression

● Interventions that are tailored to the individual and provided for a sufficient amount of time can result in treatment gainsReference Harris, Rice and Quinsey 152 – Reference Salekin 155

○ Keeping in mind, treatment gains may be modest or non-existent

● Treatments that address patients’ dynamic risk factors through psychotherapy and structured milieu interventions are most effective

● Interventions to address maladaptive patterns of thinking and behaviorReference McGuire 156

○ Reasoning and Rehabilitation (R&R)Reference Ross and Fabiano 157 , Reference Tong and Farrington 158

○ Enhanced Thinking Skills (ETS)Reference Clarke 159

○ Think First (TF)

● PsychotherapyReference Renner, van Goor, Huibers, Arntz, Butz and Bernstein 160 – Reference Livesley 162

○ May include theme-centered psychoeducation and process components

○ Modify antisocial attitudes

○ Improve problem solving abilities and self-regulation

○ Reduce resistance and impulsive lifestyles

○ Focus on early maladaptive schemas, schema modes, and coping responses

○ Seek to increase the patient’s awareness of how hostile thoughts, biases, and worldviews have contributed to his or her maladaptive behavior

○ If the patient is particularly psychopathic, individual therapy may be contraindicated

● Milieu

○ Highly structured environment

○ Lack of access to dangerous materials

○ Staff having strong boundaries is crucial

○ Increased monitoring/externally imposed supervision

■ Cameras

■ Hospital security officers

○ Consider a rotation

● Every interaction between the patients and a staff member should be considered an opportunity to reinforce pro-social behaviors and practice learned skills

● Reinforce and model pro-social ways to achieve one’s goals

Setting and Housing

● Make all efforts to preserve patients’ self-determination, autonomy, and dignity within the treatment environment 163

● Avoid seclusion, physical restraint, and sedation when possible

○ Finding the right balance is key

■ For instance, staff should not avoid the use of restraint and seclusion to the point where the patient does not have to follow unit rules

● Hospitalize patients in an enhanced treatment unit (ETU) who haveReference Coombs, Taylor and Pirkis 164

○ Recently committed/threatened acts of violence or aggression that put others at risk of physical injury and cannot be managed in a standard treatment setting

○ Recurrent violent or aggressive behaviors that are unresponsive to all therapeutic interventions available in a standard treatment setting

■ Review attempted interventions to ensure that standard of care has been met

● Communicate with treating clinicians to discuss past treatment plans

● Review medications to determine if pharmacotherapy meets standard of care for the identified disorders

● Review psychological assessments to determine if the relevant assessments have been attempted

● Review past psychological interventions, including behavioral plans, group treatment enrollment, and individual therapy progress

○ A high risk of violence that cannot be contained in a standard treatment environment determined by a violence risk assessment process in conjunction with clinical judgment

■ The patient shows continued symptoms that increase risk for violence despite standard care

■ The patient refuses to engage in treatment activities

■ The patient refuses medication

■ The patient possesses prominent risk factors for violence

○ Examples of violence or aggression that meet criteria for ETU admission:

■ One severe act of violence to staff or peers that causes bodily injury

■ Multiple acts of moderate physical violence with the potential to cause injury

■ A threat of significant violence (eg, “I’m going to kill you!”) with a history of past violence

■ Threatening gestures or words (eg, raised fist, slicing hand across throat) or words constituting a threat of violence

■ Intentional destruction of property to cause intimidation, discomfort, pain, or humiliation

■ Acts of sexualized violence or attempted sexual violence

○ Examples of behaviors that DO NOT meet criteria for ETU admission:

■ Nuisance behavior that is disruptive but does not cause injury to peers or staff, or has little foreseeable likelihood to result in injury

■ Minor forms of injurious behavior unlikely to cause substantial injury or permanent damage

■ Sexual behavior that is consensual and does not include an aggressive or violent component

■ Destruction of property lacking intent or risk of personal or interpersonal harm

■ Inappropriate masturbation

● Discharge patients from ETU who meet all of these criteria:

○ No evident risk of aggressive or violent behavior as demonstrated by absence of:

■ Serious rule violations

■ Heightened risk factors for assaultive or aggressive acts as determined by the violence risk assessment process

■ Threatening acts (eg, spitting, leering, posturing to fight)

■ Assaultive acts

■ Intimidating acts

○ Reasonable probability that the patient will be able to maintain psychiatric stability in a less structured environment and will continue to participate in ongoing treatment activities designed to reduce violence risk

■ Based on documented treatment records including notes, treatment plans, and consultations

○ Risk assessment indicates that the patient’s current risk for aggression on a standard treatment unit or in a less structured environment is no longer elevated

■ The risk assessment process should include objective inpatient violence risk factors

■ Underlying risk factors that contributed to elevated violence risk and placement in the ETU have been mitigated

Conclusion

In conclusion, the task before clinicians who treat violent mentally ill patients is great. We are challenged to help these individuals by whatever means necessary, while at the same time working within the practical restrictions of a hospital setting. The above guidelines will hopefully provide assistance with this task, and can be used as a reference. It is important to remember that many of our patients do not wish to harm others; they are simply struggling to hold themselves together, day in and day out, and it is our duty to help them achieve their highest potential. We must make every attempt to keep all those at our hospitals safe—patients and staff alike. Our concluding thought is to remember that our efforts matter; that by using science, and the best tools available, we can change the course of a life.

Disclosures

Debbi Ann Morrissette has nothing to disclose.

Marie Cugini Schur has nothing to disclose.

Jonathan Meyer has the following disclosures:

– BMS, Speaker, Speaker’s fee

– Genentech, Speaker, Speaker’s fee

– Genentech, Advisor, Honoraria

– Otsuka, Speaker, Speaker’s fee

– Sunovion, Speaker, Speaker’s fee

Eric Schwartz has nothing to disclose.

Susan Velasquez has nothing to disclose.

Darci Delgado has nothing to disclose.

Laura Dardashti has nothing to disclose.

Katherine Warburton has nothing to disclose.

George Proctor has nothing to disclose.

Michael Cummings has nothing to disclose.

Jennifer O’Day has nothing to disclose.

Charles Broderick has nothing to disclose.

Allen Azizian has nothing to disclose.

Benjamin Rose has nothing to disclose.

Shannon Bader has nothing to disclose.

Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD is an Adjunct Professor of Psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, Honorary Visiting Senior Fellow at the University of Cambridge, UK and Director of Psychopharmacology for California Department of State Hospitals. Over the past 12 months (March 2013–April 2014) Dr. Stahl has served as a Consultant for Astra Zeneca, Avanir, Biomarin, Envivo, Forest, Jazz, Lundbeck, Neuronetics, Noveida, Orexigen, Otsuka, PamLabs, Servier, Shire, Sunovion, Taisho, Takeda and Trius; he is a board member of RCT Logic and GenoMind; on the Speakers Bureau for Astra Zeneca, Janssen, Otsuka, Sunovion and Takeda and he has received research and/or grant support from AssureX, Eli Lilly, EnVivo, Janssen, JayMac, Jazz, Lundbeck, Mylan, Neuronetics, Novartis, Otsuka, Pamlabs, Pfizer, Roche, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva and Valeant.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1092852914000376.