Introduction

Stroke is the primary cause of disability worldwide (Thrift et al., Reference Thrift, Cadilhac, Thayabaranathan, Howard, Howard, Rothwell and Donnan2014), especially in the elderly (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Mendis and Mathers2009; Kelly-Hayes, Reference Kelly-Hayes2010). After rehabilitation, stroke survivors have to cope with substantial physical, cognitive and emotional deficits (Bonita et al., Reference Bonita, Mendis, Truelsen, Bogousslavsky, Toole and Yatsu2004). In their everyday life at home they usually need care and assistance from family members (Bakas et al., Reference Bakas, Clark, Kelly-Hayes, King, Lutz and Miller2014). Family care-givers are relatives, partners, friends or neighbours, who provide voluntary physical, practical and emotional care and/or support to a person with a chronic disability in the home environment (Candy et al., Reference Candy, Jones, Drake, Leurent and King2011; Family Caregiver Alliance, 2019). Most family care-givers caring for an elderly patient are also over 65 years of age, and are likely to suffer from declining health themselves (Camak, Reference Camak2015; Family Caregiver Alliance, 2019).

Compared with other care-giving situations, such as in Alzheimer's dementia, the suddenness of a stroke, with an abrupt onset of complex demands, is challenging for the family (Redfern et al., Reference Redfern, McKevitt, Wolfe and Charles2006; Legg et al., Reference Legg, Quinn, Mahmood, Weir, Tierney, Stott, Smith and Langhorne2011). Family care-givers can feel pressurised by the expectation from professionals in the system that they are able to manage immediately individual, interpersonal and organisational issues, without enough time to adjust to the new situation or to find their way within the support system (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Young, Forster and Ashworth2003; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Hunt and Steadman2014). New care-givers, in particular, may suffer from low health literacy concerning the consequences of a stroke, but may also be unfamiliar with the stroke support system in their setting, or lack the knowledge and skills to master care at home (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Lawrence, Kerr, Langhorne and Lees2004). Complex demands of care-giving may influence negatively the family care-giver's own physical, psychological, psycho-social, social health or financial situation (Lutz and Young, Reference Lutz and Young2010; Adelman et al., Reference Adelman, Tmanova, Delegado, Dion and Lachs2014). Many long-term stroke care-givers suffer from depression (Han and Haley, Reference Han and Haley1999) and social isolation (Tooth et al., Reference Tooth, McKenna, Barnett, Prescott and Murphy2005).

The professionals in the health-care system often ignore the needs of stroke family care-givers (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Schnepel, Smotherman, Livingood, Dodani, Antonios, Lukens-Bull, Balls-Berry, Johnson, Miller, Hodges, Falk, Wood and Silliman2014; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiao and Bellis2015). Family care-givers require informational, emotional, psychological, psycho-social and peer support (Wilz and Böhm, Reference Wilz and Böhm2007; Li et al., Reference Li, Xia, Wang, Zhang, Liu and Wang2017), as well as coaching during patient's transitions (Egan et al., Reference Egan, Anderson and McTaggart2010). The provision of psychological first aid seems to be essential (Gunderson et al., Reference Gunderson, Crepeau-Hobson and Drennen2012). Family care-givers can feel marginalised or overlooked by support services, may lack sufficient communication with professionals, or may have limited awareness of services and involvement during transferals of the patient (Ng, Reference Ng2009; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiao and Bellis2015; Pindus et al., Reference Pindus, Mullis, Lim, Wellwood, Rundell, Abd Aziz and Mant2018). Insufficient preparation to cope with the stroke survivor's impairment after hospital discharge can foster complications, leading to rehospitalisation, the so-called ‘revolving door’ phenomenon (Perry and Middleton, Reference Perry and Middleton2011; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Ehnfors, Eldh and Ehrenberg2012).

Over the last decades, numerous stroke care-giver support programmes have been developed and tested (Bakas et al., Reference Bakas, McCarthy and Miller2017). Overall, stroke care-giver support initiatives vary in content from specialist services, (psycho-)education, counselling and social support by peers (Visser-Meilly et al., Reference Visser-Meily, van Heutgen, Post, Schepers and Lindeman2005). Most interventions are multi-component, including information provision, education and counselling (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Egbert, Dellman-Jenkins, Nanna and Palmieri2012; Ostwald et al., Reference Ostwald, Godwin, Cron, Kelley, Hersch and Davis2013). Interventions also vary in approach, e.g. personalised or group support, number of sessions or actual support time, from e.g. a two-hour session (Aguirrezabal et al., Reference Aguirrezabal, Duarte, Rueda, Cervantes, Marco and Escalada2013) to a 12-week support service (King et al., Reference King, Hartke, Houle, Lee, Herring, Alexander-Perterson and Raad2012). No programme operating parallel to the whole stroke patient care pathway could be found in the literature, but there were examples of care-giver support programmes in specific phases in the stroke patients care trajectory. For instance, Forster et al. (Reference Forster, Dickerson, Young, Patel, Kalra, Nixon, Smithard, Knapp, Holloway, Anwar and Farrin2013) offered a structured care-giver training programme in the acute stroke phase in hospital, whereas Aguirrezabal et al. (Reference Aguirrezabal, Duarte, Rueda, Cervantes, Marco and Escalada2013) offered their programme in the rehabilitation phase, and Ostwald et al. (Reference Ostwald, Godwin, Cron, Kelley, Hersch and Davis2013) in the home care phase. In the majority of the interventions reviewed recently by Bakas et al. (Reference Bakas, Clark, Kelly-Hayes, King, Lutz and Miller2014), the effect of the support programmes was measured and evaluated only at individual care-giver level. A multitude of evaluation instruments was used, showing changes on care-giver's preparedness, knowledge, anxiety and depression, burden, strain, quality of life, social functioning, service use and satisfaction with the support were measured (Bakas et al., Reference Bakas, Clark, Kelly-Hayes, King, Lutz and Miller2014). Greenhalgh et al. (Reference Greenhalgh, Jackson, Shaw and Janamian2016) emphasised the importance of the system, but no reports on the impact on the support system itself were found. Nevertheless, building up a professional support network, discovering new support offers and optimising the quality of care for the stroke survivor are thought to be paramount for the care-giver (Visser-Meilly et al., Reference Visser-Meily, van Heutgen, Post, Schepers and Lindeman2005).

Family care-giver support in the German stroke care system

In Germany, the entire stroke rehabilitation process is fragmented (see Figure 1). It is characterised by multiple transition points and diverse bureaucratic, informational and logistical bottlenecks (Schuler and Oster, Reference Schuler and Oster2004). The system lacks co-ordination, communication and navigation through the different phases and affiliated services on individual and societal levels.

Figure 1. The German stroke rehabilitation support system and the timing of support by the Care-givers’ Guide.

Source: Adapted from Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Rehabilitation (2014).

Regional stroke units apply predominantly a patient-centred approach. Most of these units have implemented a case management system in order to facilitate a smooth patient transferal process from acute to rehabilitation care, but still fail to actively invite family care-givers to participate in these transferals (Küttel et al., Reference Küttel, Schäfer-Keller, Brunner, Conca, Schütz and Frei2015). Even the good practice project of the German Stroke Association, ‘Schlaganfall-Lotse’, puts attention only on the patient and not on the care-giver–patient dyad (Manteufel, Reference Manteufel2012). In general, one-size-fits-all care-giver support is offered, haphazardly, for instance by health insurances (Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung (GKV), 2011; Allgemeine Ortkrankenkasse, 2019) or communal services. Moreover, most of these services, even the well-known ‘Familiale Pflege’ project, focus on the improvement of ‘nursing’ skills, without taking the care-giver's own needs into account (Gröning et al., Reference Gröning, Lienker and Sander2018). In Germany, a comprehensive, nation-wide care-giving policy is missing (GKV, 2011), and a holistic stroke care-giver support programme that supports care-givers’ informational and psycho-social needs across their trajectory was not available.

The Care-givers’ Guide programme

The Care-givers’ Guide is a new primary prevention programme that was recently initiated, developed and implemented by the multi-disciplinary team of the Institute for Health Research and Social Psychiatry (igsp) in the Catholic University of Applied Sciences North Rhine-Westphalia in Aachen, Germany (2012–2015). The overall objective is to provide professional needs- and process-oriented support to stroke family care-givers (Jungbauer et al., Reference Jungbauer, Floren and Krieger2014). Care-givers are to be approached via outreach counselling and supported throughout the entire stroke care trajectory by a specially trained counsellor (clinical social worker), from as early as possible after stroke and for as long as needed and with as many sessions as necessary.

The actual Care-givers’ Guide programme consists of eight conceptual building blocks (CBB) (Krieger et al., Reference Krieger, Floren, Feron and Dorant2019). Five core blocks, ‘Content’, ‘Human resources’, ‘Personalised approach’, ‘Timing’ and ‘Setting’, essential for personalised care-giver support, were developed in the programme's development phase using insider knowledge from important stakeholders revealed through qualitative research methods (Krieger et al., Reference Krieger, Feron and Dorant2017). The three facilitating blocks, ‘Network building’, ‘Communication’ and ‘Social safety-net’, that together will serve as a lifebelt for the programme within the existing support system, were developed in the programme's optimisation phase, before the programme was implemented, by using Participatory Action Research (Krieger et al., Reference Krieger, Floren, Feron and Dorant2019). To manage the implementation of the programme, two instruments were developed using the inputs of a combined stakeholder and risk analysis (Krieger et al., Reference Krieger, Feron, Bouman and Dorant2020). A regional care-giver peer group had to be established by the project group to fill a gap in the desired support offer.

The complete programme with its eight CBBs, as well as each individual CBB, was set up to be flexible, in order to address variations between individual care-givers and system needs, also over time as new situations might emerge (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The conceptual building blocks of the Care-givers’ Guide on individual and system levels.

In this article, we report on the evaluation of the Care-givers’ Guide on two levels. Outcomes on the individual stroke family care-giver and the perceived benefits for the stroke care system are described.

Methods

In accordance with the Medical Research Council guidelines, this multi-component programme has to be considered and therefore evaluated as a complex intervention (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Dieppe, Macintyre, Michie, Nazareth and Petticrew2008). To address its complexity, a two-level multi-methodological approach was necessary (Creswell et al., Reference Creswell, Fetters and Ivankova2004; Morse and Cheek, Reference Morse and Cheek2014), with two concurrent interconnected parts (see Figure 3) and an explanatory sequential design (Ivankova et al., Reference Ivankova, Creswell and Stick2006).

Figure 3. Evaluation design of the Care-givers’ Guide support programme in the implementation and evaluation phase of the project.

Notes: The arrow between family care-givers and professional service providers depicts the interconnectedness in the system. T0: pre-intervention. T1: post-intervention.

Participants

Group 1: stroke family care-givers

Participants were first-time family care-givers with a prospective role as care-giver of a stroke patient, who lived in the region of Aachen. All participants had to be referred to the programme by professionals (not earlier than three days post-stroke) after entering the acute stroke care unit with their patient. Expectations on the prognosis of the stroke should allow for a favourable prediction on return to home.

During the admission period, 76 new stroke family care-givers were referred. However, 14 care-givers dropped out due to worsening of the patients’ situation or death (N = 7) or for reasons related to the care-giver, such as low compliance or unstable health status (N = 7).

All care-givers that completed both pre-intervention (T0) and post-intervention (T1) questionnaires (N = 62) were included in the quant-QUAL (quantitative–qualitative) (Figure 3).

Each care-giver received tailor-made counselling support from the programme's counsellor for as long as needed. The place of counselling (usually in the home), length (varying from five to nine months) and content (e.g. information provision) could be fitted to the needs of the care-giver.

On average, the support period between T0 and T1 lasted six months and contained six counselling sessions.

Care-givers were aged between 28 and 83 years (mean 56.4 years, 35% > 61 years), and the majority were females (76%). They were spouses/partners (N = 38), adult children or children-in-law (N = 19), parents (N = 2), sisters (N = 2) or a close friend (N = 1). The majority of them still worked, either full-time or part-time (27 and 26%, respectively), 34 per cent were unemployed and 13 per cent were retired.

A sub-group of 30 family care-givers (15 spouses/partners and 15 adult children) was selected to participate in a post-intervention qualitative semi-structured interview. The selection criteria were that the intervention was finalised, the care-giver was interested in participating in an interview, and the care-giver possessed time and sufficient German-language skills. The aim was to gain a detailed understanding of the perceived outcomes on care-givers’ health literacy and psycho-social health.

Group 2: professionals affiliated to the stroke care support system

Professionals were included in the analysis when they were enrolled in the programme through their daily work as care provider (e.g. medical doctors or case manager at the stroke unit), and took part in the referral procedure. Eleven professionals, representing the different domains of the stroke care and support system in Aachen, participated in a QUAL-QUAL study part ex post (Figure 3; Table 1).

Table 1. Professional stakeholders participating in the QUAL-QUAL (qualitative) study, ordered per stroke care phase

After completing the programme's implementation phase, professionals reflected in a two-part semi-structured qualitative interview on the perceived outcomes of the supported family care-givers and on their own stroke care system.

Instruments and analyses

Study part 1: before–after comparison

A quant-QUAL design was applied to evaluate the outcome at the individual care-giver level. The quantitative part served as the starting point, providing first indicators for change in health status. A qualitative interview was added to further explore the perceived changes (Figure 3).

Our semi-structured questionnaire measured two indicators of change, health literacy and psycho-social health, and contained 21 items to be scored on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 ‘very negative’ to 5 ‘very positive’ (see Appendix Table A1). Freebody and Luke's (Reference Freebody and Luke1990) health literacy framework was used to measure health literacy on three indices: (a) ‘functional health literacy’ (having enough information to function in day-to-day life) was assessed with three items (Cronbach's α = 0.84), (b) ‘interactive health literacy’ (having advanced cognitive and literacy skills to participate actively in daily activities and to apply new information to changing circumstances) with three items (Cronbach's α = 0.75), as well as (c) ‘critical health literacy’ (most advanced cognitive skills to be used to analyse critically situations and to use this information to have greater control over life) with five items (Cronbach's α = 0.66). For psycho-social health, we included six items to measure ‘sense of certainty’ (Cronbach's α = 0.82) and four items for ‘life balance’ (Cronbach's α = 0.78). SPSS 22 (Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis. Dependent t-tests were used to calculate statistical significance between T1 and T0 (p < 0.05). A higher score means a better outcome.

Semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted with a care-giver sub-group (see Appendix Table A2). All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Qualitative content analysis by Hseih and Shannon (Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005) was applied for data analysis. The transcripts were read line-by-line by the first author, and subsequently analysed by selecting and labelling sub-themes and themes emerging from the text with both deductive and inductive approaches. First, transcripts were analysed with a deductive approach (Schreiner, Reference Schreiner2012), starting with the indicators of the quantitative part as topics. Second, when new issues emerged an inductive approach was applied that led to the creation of new ‘sub-themes’ and ‘themes’ (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2013).

Study part 2: ex post analysis

Each professional was interviewed by the first author, either face-to-face (N = 8) or via telephone (N = 3). A semi-structured instrument was utilised (see Appendix Table A3) to gain a profound understanding on the perceived outcomes on both at individual and system levels.

The first author led the qualitative analysis (Hseih and Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). First, findings were divided in two data-sets: individual and system levels. The text reflecting on individual level was first analysed with a deductive approach (Schreiner, Reference Schreiner2012), referring to the ‘themes’ and ‘sub-themes’ of study 1, and when new issues emerged an inductive approach was applied (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2013). The text reflecting on the system level was analysed inductively only (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2013), applying open coding for sub-theme and theme recognition (Hseih and Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005).

All data collection instruments were piloted by participants from both groups regarding their feasibility, e.g. length, textual understanding and logical flow. The first author, conducting the interviews with both groups, was not involved in the counselling process at any time. The application of a semi-structured topic list allowed a dialogical means of communicating with the participant during the qualitative data collection process. Differences in data interpretation were discussed among the researchers until consensus was reached (Elo and Kyngäs, Reference Elo and Kyngäs2008). For each study part findings were triangulated, leading to a comprehensive understanding of the perceived changes on individual and system levels (Patton, Reference Patton2001; Springett and Wallerstein, Reference Springett, Wallerstein, Minkler and Wallerstein2008).

Ethics

Two dimensions of ethics in qualitative research were addressed: (a) procedural ethics and (b) ‘ethics in practice’, defined as the everyday ethical issues that arise while doing research (Guillemin and Gillam, Reference Guillemin and Gillam2004). First, ethical approval was given by the Ethic Committee of the Catholic University of Applied Sciences North Rhine-Westphalia. In addition, the COREQ research reporting guidelines were followed (Tong et al., Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007). Family care-givers received information about the study and provided written consent before data collection started. Verbal consent was obtained from all professionals participating in study 2. The second dimension was addressed by considering four important ethical research principles: (a) beneficence, (b) respect for autonomy, (c) justice, and (d) non-maleficence (Beauchamp and Childress, Reference Beauchamp and Childress1989).

Results

The two-level evaluation took four months and resulted in six outcomes. Five outcomes illustrate change on individual care-giver level, with special focus on health literacy and psycho-social health. One outcome concentrates on the perceived changes on the stroke support system level.

Outcomes at an individual level

Care-givers’ perspective

Health literacy improved on all three indices, with functional and interactive health literacy showing a statistically significant increase (Table 2). Both psycho-social health indices also improved: care-givers’ sense of certainty was significantly increased, whereas on life balance only marginal changes were perceived.

Table 2. Outcome on care-givers’ health literacy and psycho-social health; a quantitative pre- and post-analysis among 62 stroke care-givers supported by the Care-giver's Guide

Notes: HL levels (Freebody and Luke, Reference Freebody and Luke1990) were adapted to the programme. T0: pre-intervention. T1: post-intervention. SD: standard deviation.

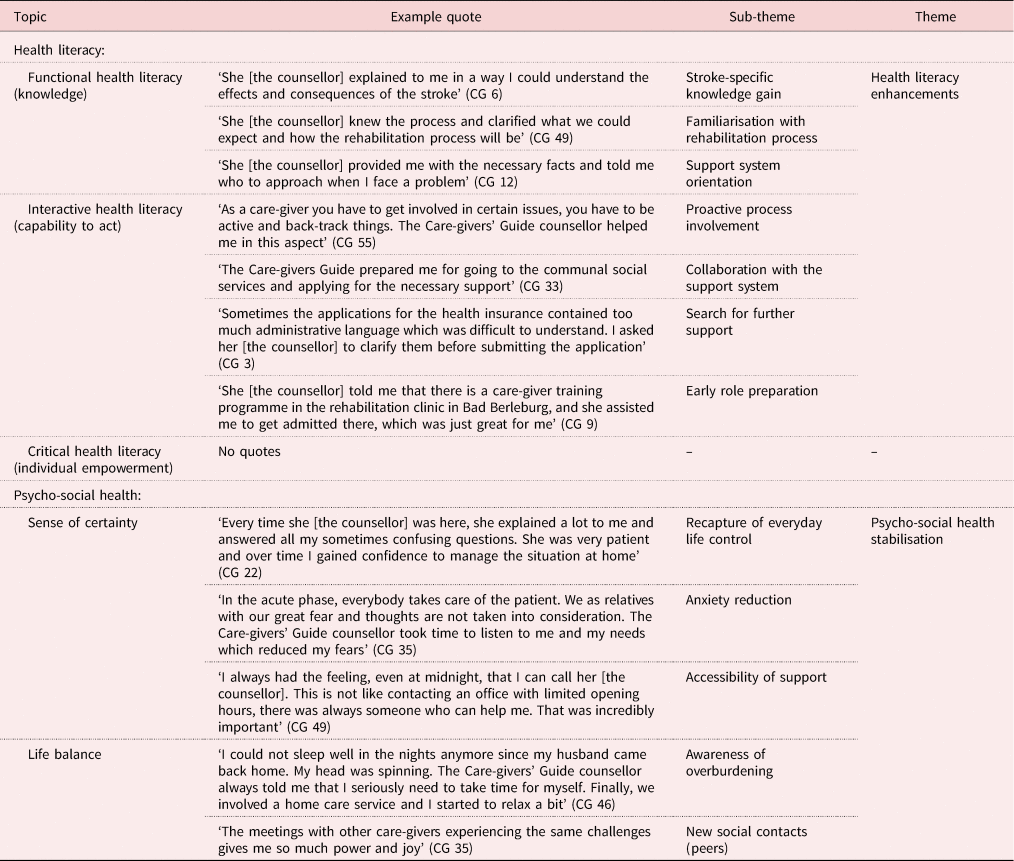

The concepts of health literacy and psycho-social health were explored in depth in the qualitative part of the individual care-giver study part with a deductive approach (Figure 3), using the indicators of the quantitative part as topics for the semi-structured interview. The detailed results with corresponding example quotes are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Deductively exploring the outcome of the intervention on care-givers’ health literacy and psycho-social health; a semi-structured interview-based qualitative study among 30 stroke care-givers (CG) supported by the Care-givers’ Guide

Family care-givers perceived that due to the Care-givers’ Guide counselling their health literacy and psycho-social health was enhanced.

Care-givers perceived a stroke-specific knowledge gain, which is considered as the first level of health literacy. Their understanding of stroke and its consequences improved, they could familiarise with the fragmented German stroke rehabilitation process (Figure 1) and felt oriented within the regional stroke support system with its support options, e.g. communal services (Table 3).

Care-givers noticed that their capability to act (level 2 of health literacy) improved during the counselling process:

I often could not understand the letters and requests from the health insurance. After she [counsellor] explained the topic to me I could react better on it. (Care-giver (CG) 3)

After having the necessary information (knowledge), care-givers felt enabled to collaborate with the system for both the patient and their own purposes, e.g. to find a suitable home care service. They started to involve themselves actively in the rehabilitation and discharge process and/or searched for further support options within the system:

She [counsellor] explained that we may apply for a disability card. I would not think about this issue by myself. (CG 53)

A timely stimulation for preparation for their new care-givers’ role was perceived as beneficial. Proposals from the Care-givers’ Guide like ‘attending a communal care-giver course’ (CG 35) or ‘searching for a day care option’ (CG 40) were considered to be very helpful.

Concerning the individual empowerment (critical health literacy – third level) due to information provision, no quotes were found in the qualitative interviews with the care-givers in Table 4.

Table 4. Inductively exploring the outcome of the intervention on other care-giver aspects that contribute to psycho-social health; a qualitative study among 30 stroke care-givers (CG) supported by the Care-givers’ Guide

Care-givers perceived that their psycho-social health stabilised due to the counselling process. They highlighted that counselling helped to maintain or retrieve their sense of certainty and assisted them in recapturing control of their everyday life and in taking actions to plan their ‘new life’, e.g. considering different future scenarios. Both the active listening strategy and the ‘first aid guide’, provided to each care-giver as an instrument in case of a possible re-infarct, were perceived to alleviate care-givers’ anxiety. Counsellor accessibility was perceived as crucial in the instable new situation:

She [counsellor] always said that I should call her if I'm in trouble and this helped me to calm down my fears. (CG 38)

Moreover, care-givers stated that the counselling process helped them to find a balance in their new life. Awareness of overburdening due to a new role was raised and practical solutions were found together with the counsellor:

She [counsellor] came up with the idea that we might profit from a holiday trip and helped us though the difficult administrative process of application with the health insurance. (CG 38)

Especially towards the end of the patient's rehabilitation process, some care-givers profited from gaining new contacts within the newly established peer group:

The meetings with other care-givers that experienced the same challenge gave me so much power and joy. (CG 35)

Post-stroke, care-givers said of themselves things such as:

It was just too much. I guess if there is nobody to help, one may easily get their head stuck in the sand. (CG 35)

Most care-givers stated that emotional re-stabilisation was ‘very essential’ for them (CG 55). From the first counselling session, the provision of psychological first aid support, e.g. promoting hope, was perceived as helpful to alleviate destructive emotions. Moreover, personalised counselling was considered as ‘very important’ (CG 11) for taking on the new role. The personalised approach helped to gain confidence to plan a realistic future as a family. Moreover, care-givers felt supported during their grieving process.

It is a completely different life…! How often do we sit here and tell ourselves ‘if we could have our old life back…’ Yes, the old life, we miss it much! (CG 5)

Finally, counselling was perceived as useful in resolving conflicts caused by having the stroke in the family, e.g. financial issues:

In that difficult [acute] phase I was not always in complete agreement with my sister. She [counsellor] helped us to find a good compromise. (CG 53)

Overall, the outcomes of the qualitative part suggest that individual family care-givers perceived the intervention as a great benefit.

I did not know where my head was! I was overwhelmed with fear and could barely think. Without the Care-givers’ Guide I would have probably lost my head. (CG 24)

Professionals’ perspective

Professionals within the stroke support system perceived in individual family care-givers (individual level) who were supported by the programme, enhancements of stroke-related health literacy and psycho-social stabilisation.

In addition to the care-givers’ own perception regarding their health literacy, professionals not only perceived positive changes regarding care-givers’ knowledge (functional health literacy – level 1) and capability to act (interactive health literacy – level 2) (see Table 5), but also outcomes on their ‘individual empowerment’ (critical health literacy – level 3) that were attributed to the programme (Table 6).

Table 5. Deductively exploring the outcome of the Care-givers’ Guide programme on care-givers’ health literacy and psycho-social health; a qualitative analysis among 11 professionals working as service providers in the stroke support system

Table 6. Inductively exploring the outcome of the Care-givers’ Guide intervention on other care-giver aspects on health literacy; a qualitative analysis among 11 professionals working as service providers in the stroke support system

Professionals in all phases of the trajectory (Table 5) observed that supported care-givers were better informed about the stroke and its consequences than they expected on the basis of earlier experiences with stroke family care-givers:

Care-givers in the programme better understood the different responsibilities of the different organisations involved in the rehabilitation process. (Case manager, rehabilitation care)

Supported care-givers were also more accustomed to the broader support system and knew of more support offers, e.g. communal services offers.

Professionals also observed that care-givers’ capability to act was enhanced earlier than in those not receiving support from the programme. They attributed this to the systematic and personalised information provision offered by the Care-givers’ Guide.

I noticed that care-givers started to understand why it is important to think about the future situation already in the acute phase. Normally they are not ready for this and we have our struggles with them. (Case management 2, acute phase)

Moreover, professionals noticed that supported care-givers were earlier and more actively involved in the decision making about the future of their patient, e.g. discharge planning, and increasingly tried to collaborate with the support system instead of blocking or delaying necessary decisions, e.g. transferals to the home environment. Professionals in the home care services and the external support providers observed that care-givers prepared themselves on time for their new role and were also actively searching for support for themselves to prevent possible overburdening, e.g. exploring additional support options in the home environment, which was attributed to the intervention by the counsellor.

Similar to care-givers’ perception, professionals observed outcomes on care-givers’ psycho-social health on all three topics: sense of certainty, life balance and emotional wellbeing.

Professionals stated that during the counselling process care-givers’ sense of certainty was reinforced, as they were able to plan a realistic future and gain control over their new life. They observed that care-givers’ initial anxiety, e.g. for the future, decreased due to the conversations with the counsellor:

Care-givers had the counsellor as a first contact person if something went wrong. They told me that therefore they did not feel abandoned by the system. (Nurse, home care phase)

Moreover, professionals in all phases perceived that the supported care-givers appeared to be ‘less stressed’ (Psychologist, ambulant rehabilitation care) and attributed this to the accessibility of the counsellor via telephone or email.

Professionals observed a better life balance for supported care-givers. Care-givers who were supported directly from the start and through all rehabilitation phases (CBB timing) were more aware of the possible risk of overburdening than those not receiving support from the programme. Consequently, they started to search for preventive actions for themselves, e.g. exploring and applying for short-term care for the patient. In particular, professionals who had contact with care-givers in the home care phase noticed that supported care-givers invested in sustaining their social contacts and therefore appeared to be less isolated. In addition, some profited from making new contacts through the peer group:

Some care-givers told me that when they were more certain in their care-giving role at home, they joined the care-giver peer group and they were very content with this offer. (Head nurse, home care services)

All professionals perceived that the topic ‘emotional wellbeing’ was imperative for care-givers’ psycho-social stabilisation, and some of them stated that the professional and early provision of psychological first aid was essential for care-givers’ emotional wellbeing. ‘Some care-givers are emotionally frozen, unable to act or to take decisions. Thanks to the psycho-social support of the counsellor, most care-givers gained their decision-making skills back soon’ (Case manager 1, acute care), and ‘when overcoming their shock status’ (Case manager 2, acute care) care-givers started to organise their new life. Moreover, professionals observed that the offer of professional grieving support was perceived as very helpful by the care-givers (Table 5). Professionals perceived that the conflict resolution skills of the counsellor contributed to care-givers’ emotional wellbeing (Table 5).

In addition to care-givers’ perception (Table 3), especially, professionals in the later phases, e.g. ambulant rehabilitation or home care, observed that supported care-givers achieved an individual empowerment (Table 6).

Professionals noted that supported care-givers achieved a better role adaptation:

Supported care-givers were better equipped to understand and actively manage the care-giving process. (Medical health equipment provider, home care phase)

Moreover, an increased use of network support was observed that was considered by the professionals as important for prevention of overburdening and social isolation:

Social isolation occurs often in family care-giving. The Care-givers’ Guide counsellor assured that the work is not done by only one family member. (CEO, home care services)

Outcome on system level

The programme's outcome on the system level was considered only from the professionals’ perspective (Table 7).

Table 7. Inductively exploring the outcome of the Care-givers’ Guide intervention on the stroke care system; a qualitative inductive analysis of 11 interviews with professionals working as service providers in the stroke support system

The practitioners observed that the new programme also influenced their professional routine, the inter-institutional support, the quality of patient care and the inter-institutional co-operation.

The Care-givers’ Guide programme heightened professionals’ attention regarding the complexity of care-givers’ needs. They perceived a professional development and resource allocation. Professionals, being in contact with the programme, observed that their view of suitable support offers in the geographic region expanded and their knowledge concerning initiatives for care-giver support provided by organisations other than their own, communal services offers for care-givers, was enhanced.

All professionals who were involved in the programme acknowledged the potential surplus value of the new family care-giver support programme within their daily work:

As the psycho-social support and co-ordination was offered to the care-giver by the programme, I could concentrate on my duty – the patient care. (Nurse, home care services, home care phase)

However, some professionals in the acute care (care manager and social worker) had to spend time recruiting potential care-givers for the new programme:

We needed to invest 15 minutes per week for preparing the recruitment list, and 20 minutes for the handover to the Care-givers’ Guide. (Case manager 2, acute phase)

Professionals perceived the new care-giver programme as comprehensive support and therefore it was welcomed by them across the trajectory:

This programme was filling a significant service gap. (Social worker, acute phase)

In our clinic we do not offer care-giver counselling support. However, care-givers need clear and precise information to not get lost or overburdened by the situation, and someone who takes time for them from the start. And this is what the support programme did. (Psychologist, rehabilitation phase)

The necessary resources for providing care-giver support, e.g. time and staff, were provided by the programme, which resulted in perceived improvements of the institutional support (Table 7):

The continuous support by the Care-givers’ Guide counsellor during transferal was simplifying for our work. Because many care-givers fear the situation when a patient is transferred from the rehabilitation phase to the home environment and therefore appear to be uncooperative. (Nurse, home care phase)

Moreover, the counsellor invested in communication between all actors involved from different organisations, and this was perceived as helpful in completing and improving the handovers:

The Care-givers’ Guide supported the stroke families since the beginning. For me it was so helpful to have someone [counsellor] who knows the family since the acute phase. She offered me a structured handover and I was much better prepared when a patient and care-giver was transferred to my services. (Medical health equipment provider, home care phase)

Due to the programme, professionals in the home care phase also perceived a strengthening of the quality of patient care. They felt that the care-giver-specific information provided by the counsellor ‘completed the condensed information provided by the handover protocol’ (Nurse, home care phase). Moreover, they felt that the counsellor contributed in safeguarding the rehabilitation outcome, e.g. having the appropriate medical equipment at home before transferal.

Professionals perceived that the counsellors’ work, enhancing care-givers’ stroke-specific knowledge and stabilising their psycho-social health, contributed to ‘avoid unnecessary acute re-hospitalisation’ (Nurse, acute care).

The new programme was a main driver in building up and maintaining an inter-organisational professional network within the region at this time. An interprofessional team-building process was started, where feedback loops provided a stimulating and positive working atmosphere:

Our communication was characterised by a high level of trust and transparency. (Social worker, home adaption counselling services, communal social services)

The new network improved the flow and quality of the communication, which was especially useful in the transferal of complex cases:

Many administrative issues were solved by using shortcuts within the system, which was beneficial for all. (Medical health equipment provider, home care phase)

Co-operation through this network was perceived as especially helpful in reducing bottlenecks, e.g. communications weaknesses, during transferal. The inter-institutional co-operation also activated an increased utilisation or interlinkage with the communal actors, e.g. communal services.

The findings from both parts of the two-level study, the multi-methodological approach and the triangulation, contributed to a comprehensive depiction of the outcomes on the individual and the system levels. Overall, both care-givers and professionals within the support system perceived a benefit from the new programme:

The structured, practical, flexible and professional guidance of the care-givers that was offered by the supplementary to the current support system was a big advantage for us and the care-givers. (Head of department, neurosurgery, acute care phase)

Discussion

A two-level multi-methodological approach was chosen to evaluate the impact of the Care-givers’ Guide. The study was designed as a combination of a quantitative part measuring change in health literacy and psycho-social health in individual stroke care-givers with a semi-structured questionnaire, and three qualitative parts focusing on aspects of health literacy and psycho-social health, perceived preparedness of individual stroke care-givers and impact on the care system for stroke patients.

The results from the quantitative part on the care-giver level showed an increase in both health literacy and psycho-social health (Table 2). In the added qualitative study parts, individual care-givers reported a knowledge gain regarding stroke and its consequences, the rehabilitation process and the existing support system. They noticed improvements in their capability to act, such as proactive process involvement, collaboration with the support system, search for further support and early role preparation. They also noticed that their sense of certainty was strengthened by regaining control over their everyday life, as well as by a reduction of anxiety. Having new social contacts and being aware of the risk of overburdening due to care-giving helped to stabilise their lives. Providing professional psycho-social support enhanced care-givers’ emotional wellbeing by supporting them in their future life orientation, grieving process and conflict resolution.

The effects on the individual care-giver level were further explored by including the perspectives of professionals working in the system. Interestingly, they perceived not only improvements in functional and interactive health literacy but also an individual empowerment of the supported care-givers (Table 5), which corresponds with findings of the quantitative part (Table 2). That might be due to the fact that they could reflect on their own case only and they did not see their individual empowerment processes themselves.

The effect on the system level itself was explored by interviewing professionals as being part of that system and having experienced the impact of the new programme during their daily work. Conclusions were that investing in communication and network-building activities helped in optimising the prevailing stroke support system (Table 7). Professionals perceived a positive change in their daily work within their own institutions, a strengthening of the quality of patient care and in inter-institutional co-operation.

Learning new skills

First-time care-givers, in particular, must develop new skills, e.g. practical skills, stress-coping skills and problem-solving skills, in order to interpret and analyse health information, navigate the health-care system and participate in encounters with the support system (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Ehnfors, Eldh and Ehrenberg2012; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiao and Bellis2015). These new skills may help to adjust to the new life and its unpredictable challenges (Yuen et al., Reference Yuen, Knight, Ricciardelli and Burney2018). Our results indicate that these skills could be developed within the relatively short period of six months. We are unable, however, to make any long-term predictions, but we expect that our care-givers felt secure enough to handle pressures or added burdens should changes occur in their own or their patient conditions.

Flexibility regarding the timing and number of sessions

In contrast with most other care-giver programmes that offer support during a specific phase of stroke survivors’ rehabilitation, e.g. in the acute phase (Aguirrezabal et al., Reference Aguirrezabal, Duarte, Rueda, Cervantes, Marco and Escalada2013), or have limitations regarding the quantity and duration of counselling sessions Wilz and Barskova, Reference Wilz and Barskova2007), our programme did not set a limit on the duration of the counselling support or the number of counselling sessions, and allowed flexible choices in the actual support offer by the Care-givers’ Guide counsellor. This flexibility was perceived by both care-givers and professionals as being of great benefit in enhancing care-givers’ health literacy and psycho-social health. We also showed that it only required a reasonable number of sessions (mean six sessions) within a reasonable time period of six months, which is comparable with other programmes (Larson et al., Reference Larson, Franzén-Dahlin, Billing, Arbin, Murray and Wredling2005; Schure et al., Reference Schure, van den Heuvel, Stewart, Sanderman, de Witte and Meyboom-de Jong2006).

Personalised information provision

Receiving personalised information was perceived by both care-givers and professionals as fundamental in enhancing their stroke-related health literacy. In public health and health promotion, health literacy is an important indicator when aiming to improve health outcomes (Paasche-Orlow and Wolf, Reference Paasche-Orlow and Wolf2007).

Our findings show that increasing health literacy by targeted and timely information provision (Pindus et al., Reference Pindus, Mullis, Lim, Wellwood, Rundell, Abd Aziz and Mant2018) with a personalised approach (Krieger et al., Reference Krieger, Feron and Dorant2017) led to an early and better role adaption (Tables 3, 5 and 6).

Psychological first aid

It is well known that family care-givers experience immediate high emotional stress levels from the start of their new role (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Hunt and Steadman2014). Our Care-givers’ Guide counsellor offered psychological first aid as part of the support programme, which was perceived by both care-givers and professionals as essential in stabilising care-givers’ psycho-social health. We found only one earlier publication, offering a one-session crisis intervention to stroke survivors and primary care-givers in the inpatient rehabilitation setting (Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Glass, Palmer, Loo and Wegener2004). Unfortunately, the effect of their intervention was not reported.

The family care-giver as part of the system

Inter-disciplinary co-ordination between the different care providers, as well as co-ordinated discharge planning and case management, with focus on the needs of both the patient and their family care-givers is important (Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Tsoi and Marsell2008). However, we observed that our family care-givers were overlooked by the professionals within our setting. Our professionals stated that they lack training, time and skills to involve care-givers or provide stroke-specific knowledge, and suggested including the family care-giver in future stroke care guidelines, as was suggested by Ris et al. (Reference Ris, Schnepp and Mahrer Imhof2019).

Holistic view

From the inception of our project we considered the German stroke rehabilitation trajectory as a holistic system. Our programme explicitly invested in the system by building up a professional network and improving the communication between the different actors in the support system (Figure 2; Krieger et al., Reference Krieger, Floren, Feron and Dorant2019). As the programme progressed, the professionals involved in the service provision started to acknowledge care-givers as part of the rehabilitation team, which was perceived as a first step in system optimisation. The ‘facilitating CBBs’ were perceived by the professionals as helpful by improving the communication lines, empowering individual professionals, e.g. by gaining a better understanding of the entire support system, as well as the broader system, e.g. by stimulating direct interactions between different organisations within the setting. Especially the professionals in the home care phase observed that the quality and continuity of care for the stroke survivor in the home environment got better in the course of the project due to ‘personalised’ transferals, e.g. obtaining detailed information on the care-givers’ needs.

Strengths and limitations

In this evaluation we aimed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the outcomes of the Care-givers’ Guide programme on both the individual care-giver as well as the stroke service provider level, interconnected with each other. We chose an intricate study design with four connected parts and two different methodologies (quantitative as well as qualitative). We were limited in the quantitative part by the relatively small number of participants and the use of a questionnaire with a limited scope of health indicators. However, this quantitative part only served as a starting point for the larger qualitative part, which took up the most time and resources of the project team and the participants. We showed that using a mixed-methods approach was feasible and appreciated by the individual care-givers, as well as by the professionals. Methodological pluralism (Morse, Reference Morse2015) and the combination of a deductive–inductive approach (Graneheim et al., Reference Graneheim, Lindgren and Lindman2017) during data analysis enabled us to explore the outcomes of our complex programme in depth. However, as complex interventions are strongly context- and time-dependent (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Murray, Darbyshire, Emery, Farmer, Griffiths, Guthrie, Lester, Wilson and Kinmonth2007; Datta and Petticrew, Reference Datta and Petticrew2013), replication may be challenging. Nevertheless, our approach can serve as an example for evaluation studies of complex interventions.

Conclusion

As complex interventions may have outcomes on different levels, a comprehensive evaluation is required. This paper provides evidence of the Care-givers’ Guide benefits at both individual and system levels.

On an individual level, we detected outcomes on care-givers’ health literacy and psycho-social health. Care-givers observed improvements in their own stroke-specific knowledge (functional health literacy) and capability to act (interactive health literacy). Professionals perceived improvements in care-givers’ individual empowerment (critical health literacy). The provision of psycho-social support was perceived by both the programme's end-users (care-givers) and the service providers (professionals) as beneficial for care-givers’ psycho-social health. Care-givers’ ‘sense of certainty’ and ‘life balance’ were strengthened and their ‘emotional wellbeing’ enhanced.

At a system level, the existing stroke support system felt optimised by investing in communication and network-building activities. The Care-givers’ Guide influenced the professionals’ daily routine, the institutional support offer, the quality of patient care and inter-institutional co-operation.

The application of a two-level interconnected mixed-methods approach, as well as the deductive and inductive data analysing methods, added significantly to our understanding regarding the complexity of outcomes on both individual care-givers as well as on the stroke support system.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20000665

Acknowledgements

We thank all family care-givers and professionals for their time investment and contribution in this evaluation. The presented study stems from the research project ‘The Care-givers’ Guide’, conducted under the direction of Prof. Dr Johannes Jungbauer, at the Catholic University North-Rhine Westphalia, Germany.

Author contributions

All authors revised the article critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version. FF and ED participated in analysing and interpreting data. ED contributed to the design of the manuscript. TK contributed to the data collection and primary analysis, and the conception, design and drafting of the manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The board of the University of Applied Sciences North Rhine-Westphalia and the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Aachen provided ethical approval.

Appendix

Table A1. Pre- and post-intervention questionnaire from the Care-givers’ Guide (adapted English version)

Table A2. Topic list for semi-structured interviews with stroke family care-givers

Table A3. Topic list for semi-structured interviews with professional stakeholders