Introduction

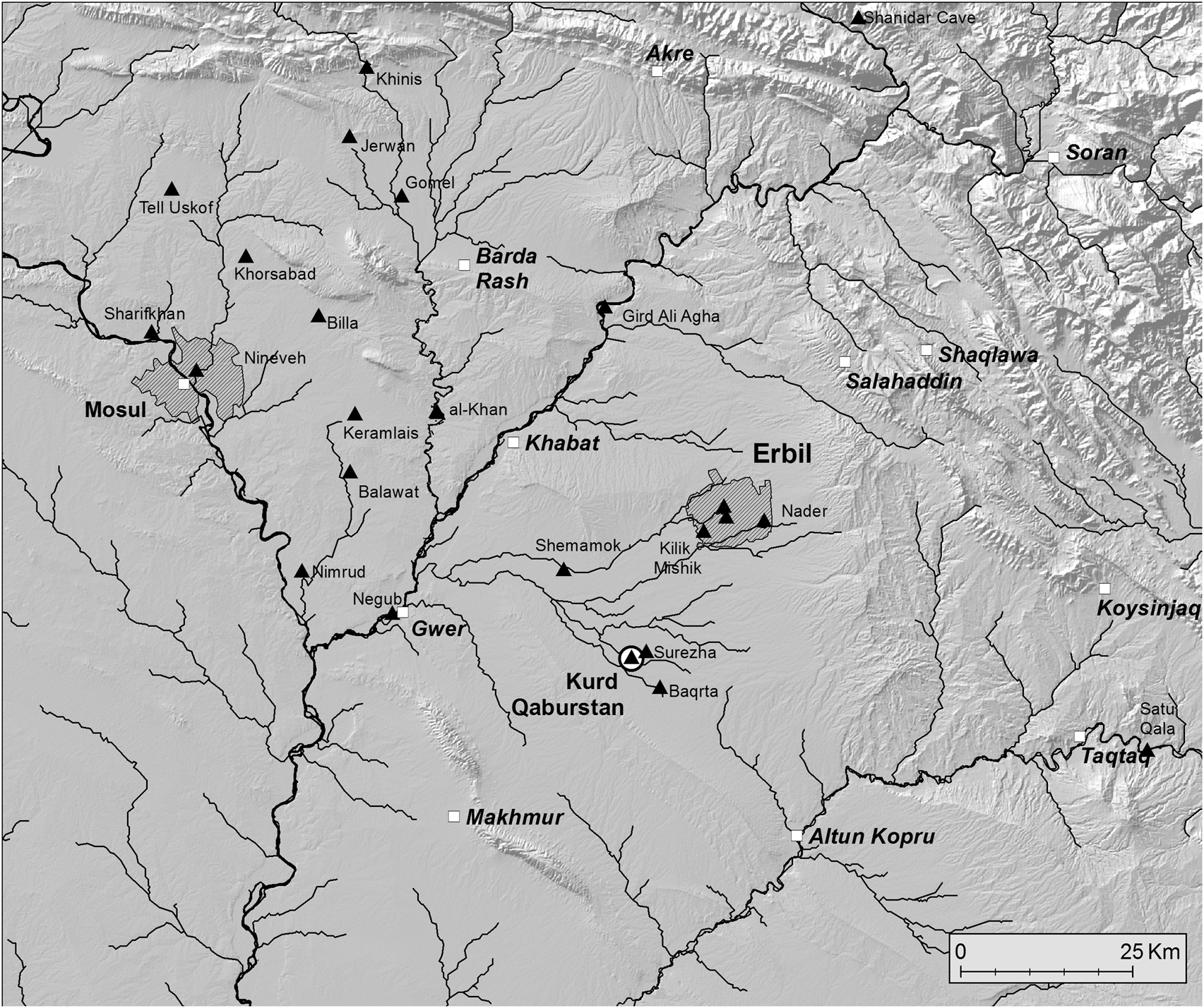

The Johns Hopkins University field project at Kurd Qaburstan on the Erbil plain in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (Fig. 1) conducted a study season in May–June 2016 and a third excavation season in April–May 2017.Footnote 1 A walled city of c. 95 hectares in the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000–1600 B.C.), Kurd Qaburstan is one of the largest Bronze Age archaeological sites in the region of Erbil (Figs. 2–3) (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017; Ur et al. Reference Ur, de Jong, Giraud, Osborne, MacGinnis, Babakr, Palermo, Creamer, Ramand, Soroush and Nováček2021).Footnote 2 Because its main period of occupation was Middle Bronze, it has been proposed that Kurd Qaburstan was ancient Qabra, capital of the Erbil area in the Middle Bronze period (Ur et al. Reference Ur, de Jong, Giraud, Osborne and MacGinnis2013). After the Middle Bronze occupation, settlement was substantially reduced in size but continued until the second millennium A.D. The Johns Hopkins Kurd Qaburstan project aims to study the development, character, and organization of a second millennium B.C. northern Mesopotamian city, focusing on the Middle and Late Bronze periods.

Fig. 1. Kurd Qaburstan and the Erbil region (map by Jason Ur).

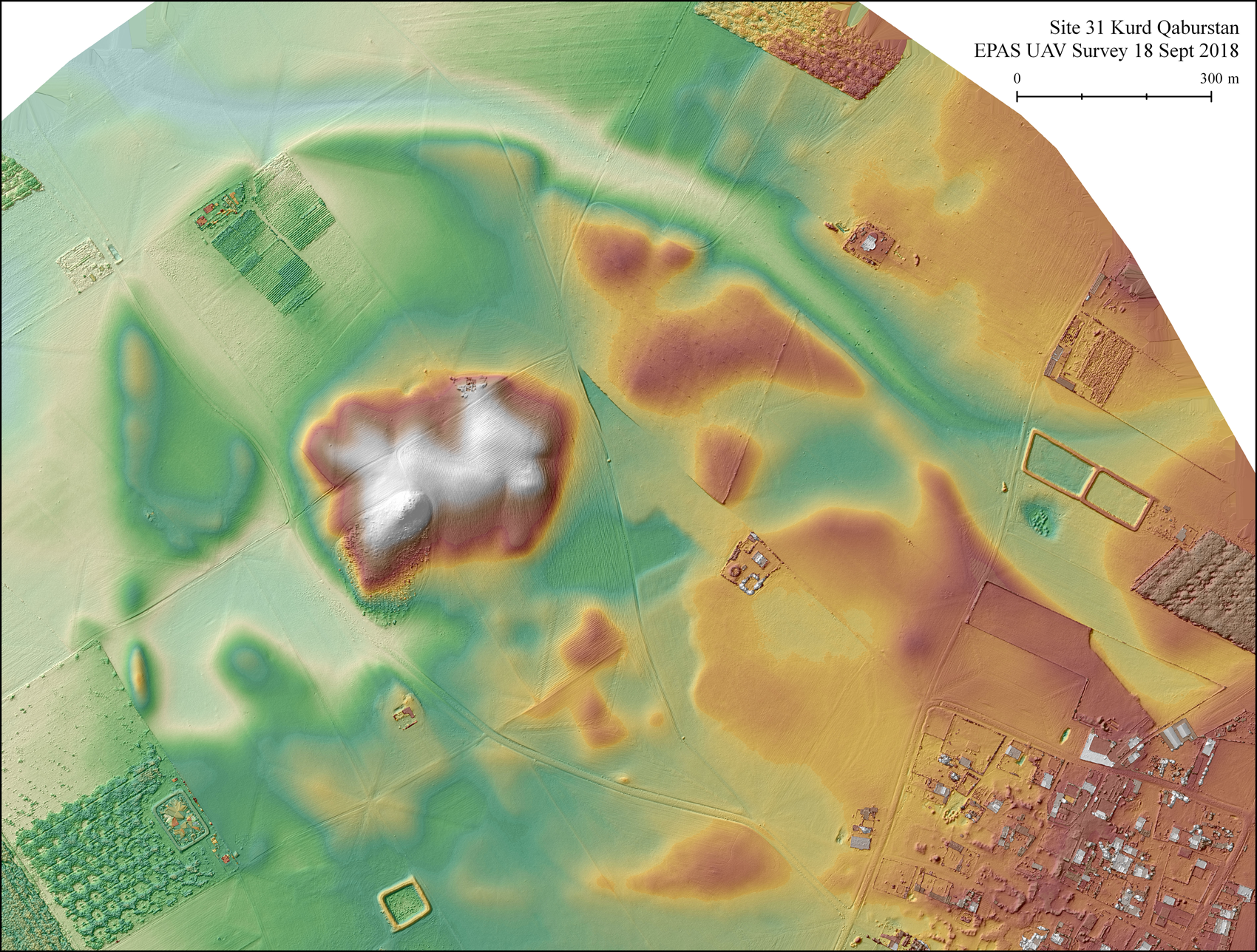

Fig. 2. Kurd Qaburstan plan, contour interval 0.5 metres. Solid line around site indicates approximate location of city wall.

Fig. 3. Kurd Qaburstan DEM (courtesy Jason Ur, EPAS Project).

As Marti and Nicolle (Reference Marti, Nicolle, Marti, Nicolle and Shawaly2015: 116) have observed, Kurd Qaburstan is the second in a chronological sequence of three major urban conglomerations on the plain south of Erbil in the Bronze Age. Earliest was Tell Baqrta to the southeast of Kurd Qaburstan, estimated to have encompassed some 90 hectares in the Early Bronze Age (Kopanias et al. Reference Kopanias, Beuger, MacGinnis, Ur, MacGinnis, Wicke and Greenfield2016). An identification of Baqrta with ancient Hamazi (Steinkeller Reference Steinkeller, Buccelati and Kelly-Buccelati1998) might be hypothesized. Following the floruit of Kurd Qaburstan in the Middle Bronze Age (hereafter MB), 50-hectare Qasr Shemamok to the northwest became the main center of the region in the Late Bronze (hereafter LB) and Iron Ages. The site has been identified as the Assyrian provincial capital Kilizu and, in an earlier part of the Late Bronze Age, a locality called Tue (Masetti-Rouault Reference Masetti-Rouault, Otto, Roaf and Kaniuth2020; Rouault Reference Rouault, MacGinnis, Wicke and Greenfield2016).

Kurd Qaburstan is located within the drainage area of the Chai Kurdara watercourse, which flows west into the Upper Zab river. Positioned strategically, Kurd Qaburstan is near a gap in the Avanah Dagh hills that provides access from the Erbil region to the Makhmur plain and the Tigris valley beyond. The annual rainfall of c. 300–400 mm per year documented in recent times would have permitted successful dry farming in the region.

Kurd Qaburstan is comprised of an 11-hectare high mound with three distinct peaks of elevation and a walled lower town now estimated at 84 hectares. Considering the topographic map (Fig. 2) and DEM (Fig. 3), we can observe that the site's enclosure wall is punctuated at several points by likely gates. A large depression southwest of the high mound may have served as a source of soil for mudbrick construction.Footnote 3 Further details on the spatial configuration of the site are discussed below in the geophysical commentary.

The 2016 study season included reconstruction of MB vessels from the Lower Town North A, study of LB pottery from the High Mound East, and faunal and osteological analysis. In the 2017 field season, the project had four main goals:

(1) continue the geophysical survey of the ancient city to determine its organization and spatial layout,

(2) expand excavations of Middle Bronze remains on the lower town and the south slope of the high mound, where Middle Bronze contexts are accessible directly below the surface,

(3) identify and excavate Middle Bronze remains on the high mound,

(4) expand excavations on the high mound where well-preserved Late Bronze architecture is accessible below the site surface.

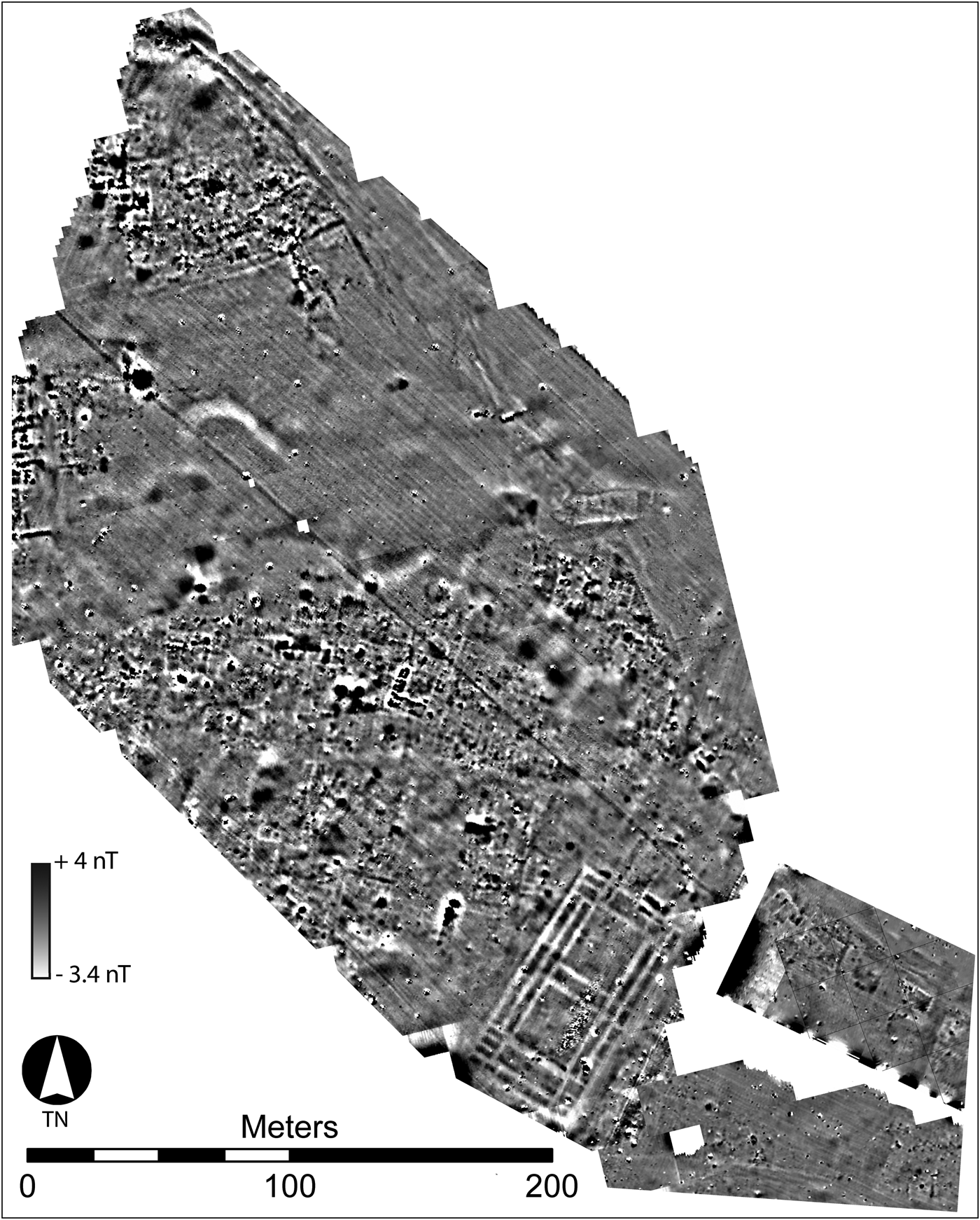

Geophysical Survey

In 2017, the geophysics team continued magnetometer survey on the lower town of Kurd Qaburstan to investigate the urban structure, to learn how the city grew, and to identify possible evidence for destruction such as burning.Footnote 4 Most of the evidence dates to the Middle Bronze Age, since the majority of the latest occupation on the lower town belongs to that era (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017). We surveyed 17 hectares with a Bartington Grad 601-2 Magnetic Gradiometer, bringing our total coverage to 51 ha of the 95-ha city.Footnote 5 The new data reveal information about the city wall, street patterns, gates, open space, and a large public building or temple. We focused our work on the southern and eastern parts of the city in Areas 2 and 6 (Fig. 4).Footnote 6 Obstacles to survey, marked by gaps or cluttered high-value magnetism features in the data, included a large cinder-block enclosure along the northwestern edge of the modern village and modern metal debris from the village that spreads into adjacent agricultural fields. Despite these obstacles, the work was very fruitful.

Fig. 4. Magnetometry data collected to date, with survey areas, selected streets, and major features indicated. Due to varied data processing in this composite figure, the nanotesla scale (nT) is generalized to high/low.

City Wall

We previously identified a city wall with bastions at the western and northwestern edges of the city in Areas 4 and 5 (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017: 240–241). The data from 2017 show the city wall continuing around the northeastern corner of the city, and we pick it up again in the southeastern corner. Notably, we see a second, inner or double, wall in the northern area (Figs. 5–6). It is not clear if this double wall represents multiple phases, an expansion of the city, or an internal walled area such as a citadel or other protected zone. Like the bastions in the northwestern city wall in Area 5, the bastions of the outer wall are spaced 18–22 m apart, and the smaller bastions of the internal wall are c. 10 m apart. The bastions along the southern segment of the city wall in Area 2 are 11–16 m apart. The southern wall may also have a glacis, as previously suggested for the western and northwestern walls (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017: 241).Footnote 7 There are several candidates for gates along the newly discovered sections of the city wall, located in areas where a street approaches the city wall or a structure seems to breach that wall (Fig. 4, arrows).

Fig. 5. a) Magnetometry, Area 6, showing dense architecture surrounding a possible open space, city wall with double-wall segment, and possible gates. Processing steps: zero median traverse, destagger, interpolate to 8 x 8 samples/m, wallis enhancement, clip at 1 standard deviation. See Fig 4 for inset location.

Fig. 6 Magnetometry, Area 6, with features marked.

Open Space, Streets, and Structures

In the northeastern part of the city in Area 6 we identified an area over 2 ha that is apparently devoid of structures and may be a large open space within the city walls (Figs. 5–6). The dense structures at its northern, western and southern edges end abruptly at this space. This transition corresponds to a topographic depression surrounded by mounded ruins. Barring evidence for modern bulldozing, erosion, silting, or substantial landscape modification, this apparently natural depression marks a substantial open space unparalleled in other survey data from the site.

Street patterns in the newly surveyed areas are not as clear as those discovered in previous seasons in Area 5, in part due to the obstacles and contamination described above. We identified some wider main streets and narrower secondary streets in Areas 2 and 6. The main streets are oriented approximately perpendicular or parallel to the east-west long axis of the city. Area 6 is characterized by clusters of structures with small rooms and by structures lining the city wall (Fig. 6). Several of the small-roomed structures flanking the open space show evidence of burning. The boundaries of adjacent buildings are not easy to discern, which makes it difficult to identify their individual sizes. Structures are less clear in the data from Area 2, although we can identify parts of walls that suggest dense architecture (Fig. 4).

Public Building

We identified a large 88–89 m x 48 m building in Area 6 (Fig. 6). Based on its size and parallels with other structures excavated in the region, this building can be confidently identified as a temple (see below). Notably, the building does not share the orientation of the structures immediately east or west of it. Instead, it is situated roughly perpendicular to the city wall as it turns to the northwest. The building contains two square internal spaces that we interpret as courtyards, each approximately 25 m x 23–25 m, bounded to the north and south by three rectangular rooms, measuring 15–26 m x 5–8 m, to the east and west by four narrow rooms c. 24–25 x 3 m, and at least 30 smaller rooms on the perimeter. The entrance was most likely from the north, where parallel walls lead toward the city wall. Although some areas of the building have slightly elevated magnetism that can suggest burning, the structure does not appear to have been heavily burned except perhaps in the northeast end. In that area, a rectilinear structure or room of a possibly earlier or later phase, extending as it does beyond the main outer wall, had significantly higher magnetism than other spaces. Excavations in this space (trench 5688.5/2931.5) revealed burned mudbrick debris but did not reach a floor.

Discussion

Like the results from Areas 4 and 5 in the western part of the city, these new data from the eastern part of the site reveal densely built structures and roughly rectilinear main and secondary streets. The city wall with bastions also continues around the eastern part of the city but with an intriguing earlier or inner/double wall in its northern section that could mark a specially protected area. Perhaps the most important discoveries from 2017 consist of an open space over 2 ha in area and a large temple in Area 6. Both features contribute to important discussions of city structure and growth. As the city filled in with densely built architecture, open spaces must have reduced over time. This large open space in the northeastern quarter of the city is so broad that it seems to have been protected against significant encroachment by neighboring areas.Footnote 8 Finally, the large temple does not respect the orientation of the densely built area to its west and is not accompanied by other monumental structures. Consequently, we may speculate that it was constructed later than surrounding structures and its orientation was chosen for ritual purposes or to best fit an open space or other topographic factors essential for a large structure.

Excavation Results (see Table 1)

Middle Bronze Temple, Lower Town East (LTE). After the magnetometry survey discovered a monumental building in the eastern part of the site, two small trenches were opened to explore the structure and determine its date. The trenches (5632/2878 and 5688.5/2931.5) were each 5 x 4 meters (Fig. 2).Footnote 9 All the associated material culture was Middle Bronze in date. In the northern trench 5688.5/2931.5, where the geophysical survey detected burned remains, a cluster of burned mudbricks was found out of context. Otherwise, it was difficult to discern mudbrick architecture in either trench, since the soil was homogeneous and displayed no evidence of mudbricks or of living surfaces either horizontally or in section. This is a problem typical of the Kurd Qaburstan lower town (see below, Lower Town North A and B). In future, we plan to use a magnetic susceptibility meter as an aid in recognizing the walls in this area.

Table 1. Kurd Qaburstan chronology; absolute dates and chronological relationships between excavation areas are preliminary.

According to the magnetometry results, the building measures c. 48 x 88 meters. We can compare this structure to the Middle Bronze period temple at Tell al Rimah (Oates Reference Oates and Curtis1982: 92), which resembles half of the Kurd Qaburstan building in scale and room layout (Fig. 7). Oates suggested that the Babylonian character of the Rimah temple and its architectural regularity implied the presence of Babylonian architects (Miglus Reference Miglus2013), presumably under the aegis of Shamshi-Adad, whose predilection for southern Mesopotamian material culture styles is well-attested (Ristvet Reference Ristvet2014). Shamshi-Adad's temple to the god Aššur at the site of Ashur also bears resemblances to the Kurd Qaburstan structure, although it lacks a double row of exterior rooms. From southern Mesopotamia itself, the Hammurabi-era Ebabbar temple of Shamash at Larsa is comparable (Huot Reference Huot2014). Although larger than the Kurd Qaburstan building, it has a similar plan with two courtyards flanked by a double row of rooms. Given these comparanda, we conclude that the Kurd Qaburstan building is a temple.

Fig. 7. Middle Bronze temples, from left to right: Kurd Qaburstan; Aššur temple at Ashur; Tell al Rimah; Larsa Ebabbar (all to same scale).

Fitzgerald (Reference Fitzgerald, Boda and Novotny2010) notes that Shamshi-Adad and Hammurabi built new temples or restored old ones in conquered regions to consolidate their rule. Given its similarities to the Tell al Rimah and Ashur temples, it is possible that the Kurd Qaburstan building is an example of such a project initiated by Shamshi-Adad. If so, the divergence of the building's orientation from the surrounding architecture may signal its later imposition.

Middle Bronze Remains, Lower Town North A (LTNA) and B (LTNB). MB contexts were also accessible below the modern site surface on the Lower Town North, and excavations were initiated in 2017 to expand the MB exposure in this area. In 2014, excavations in trench 4870/3217 on the Lower Town North A had identified two Middle Bronze phases now designated 1 (later) and 2 (earlier) (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017). Phase 2 (Fig. 8) had yielded a large inventory of ceramic vessels in situ, primarily from area 3 and the eastern part of area 4.

Fig. 8. Plan of Phase 2, Middle Bronze, Lower Town North A, Trench 4870/3217.

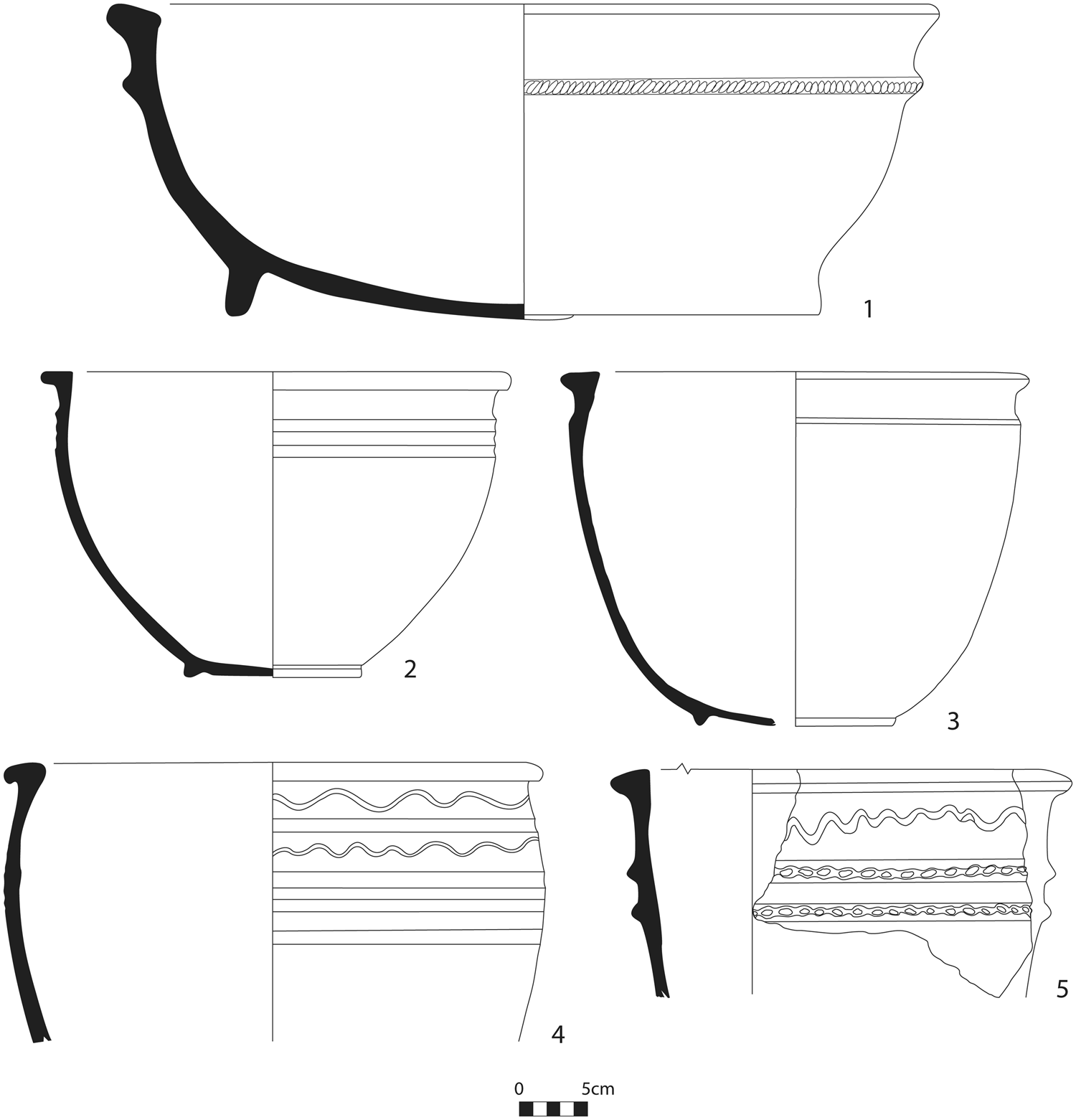

In 2017, we excavated trench 4870/3225 (6 x 10 m) north of trench 4870/3217, with a 2-meter baulk between. Two Middle Bronze phases were identified, both contemporaneous with the later MB phase 1 of 4870/3217 and designated phases 1a (later) and 1b (earlier). In phase 1a, a round clay oven (diameter 80 cm) was found in the northeast part of the trench in proximity to a floor surface. Both inside and outside of the oven were sherds of several complete or near-complete vessels, including the upper body of a ‘grain measure’ beaker with an elaborate stamped and impressed design (Fig. 9; Fig. 10: 1),Footnote 10 a ring-based beaker (Fig. 10: 2), and a ‘shoulder goblet’ (Fig. 10: 3).Footnote 11 The earlier phase 1b was mainly characterized by an expansive pebble surface. Apparently this area served as a large plaza or courtyard.

Fig. 9. Stamped and impressed beaker, Phase 1a, Middle Bronze, Lower Town North A, Trench 4870/3225.

Fig. 10. Middle Bronze ceramics, Phase 1a, Lower Town North A, Trench 4870/3225. 1: KQ 17 4870/3225-004, inside and outside oven; light brown, fire-darkened exterior, no visible inclusions, stamped/impressed. 2: KQ 17 4870/3225-009, inside oven; light yellow, medium vegetal inclusions, bitumen coating on interior from base to 5 cm below rim. 3: 4870/3225-004, on surface outside oven; light brown, no visible inclusions.

Additional Middle Bronze remains were obtained from a second trench (5134/3350, 6 x 10 m with an 8 x 1 m extension to southeast) on the Lower Town North B, northeast of 4870/3225 near the city wall. This trench was in a location where geophysical results had indicated the presence of a large building. Excavations revealed four MB phases below the present-day surface and above virgin soil. The latest two phases (1–2) each had a pebble and sherd surface in the southeast trench extension. Belonging to phase 1 were several segments of a very large open vessel with applied horizontal ribs, a type well-known in southern Mesopotamia as a receptacle for the bodies of deceased persons.Footnote 12 However, no bones were extant.

In phase 3, an earthen surface was associated with broken but complete ceramic vessels and grinding stones in the southern part of the trench. Faunal remains from this locus may reflect butchery activities (see below). Nearby in the trench center was a square threshold of large baked bricks with a baked brick door socket. Also found in phase 3 was the head from a clay figurine of a pig or boar, perforated vertically (Fig. 11).Footnote 13 Although the baked brick threshold and associated remains support the geophysical indications of a significant building in this area, the mudbrick walls of such a building were not visible.

Fig. 11. Clay figurine of boar/pig's head (KQ 17 A-3), Phase 3, Middle Bronze, Lower Town North B, Trench 5134/3350.

Virgin soil was reached below the earliest MB phase (4) in a 2 x 4 meter sondage in the southwest corner of the trench, c. 2.5 meters below the mound surface. These results indicate that at least this part of the lower town was first settled in the Middle Bronze period and was only occupied during that time frame. Given the rarity of pre-MB pottery on the site surface, it is likely that the remainder of the lower town was also founded in the Middle Bronze period.

The absence of visible mudbrick walls here and in other trenches on the lower town is attributable to local geomorphological conditions that produce a homogeneous soil masking the evidence of mudbricks. Wilkinson and Tucker (Reference Wilkinson and Tucker1995: 5–6) observed a similar phenomenon in their Iraqi North Jazira survey, where post-depositional processes on low sites transformed as much as one meter of subsurface deposit into soil without a trace of mudbricks or strata. On high tells, the situation was different, with the latest deposits eroding away and exposing the layers below so that a homogeneous soil profile did not develop. While at first glance these observations seem applicable to the situation at Kurd Qaburstan, the soil homogeneity on the lower town reaches as deep as three meters.

Given the difficulty in identifying mudbrick architecture on the lower town with the naked eye, it would seem prudent to reevaluate our earlier conclusions on the correlation between the whitish masses visible on Corona imagery and mudbrick architecture (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017: 230–231). Since we failed to observe significant mudbrick architecture in the locations where the whitish shapes were evident, we had concluded that those shapes were not necessarily indicators of substantial architecture. However, our difficulty in recognizing mudbrick architecture on the lower town during excavation indicates that we are not able to judge whether or not the whitish formations are good predictors of significant mudbrick architecture below the surface. It is both curious and fortunate that the magnetometry survey has been able to discern mudbrick architecture where the human eye cannot. One may infer that the mudbricks have magnetic properties that distinguish them from the surrounding soil.

Middle and Late Bronze Remains, High Mound North Slope (HMNS)

Middle Bronze Age contexts had been difficult to reach on the high mound in previous seasons due to the depth of the Late Bronze remains under the site surface. An exception was the High Mound South Slope (see below). In hopes of documenting Middle Bronze phases in the northern part of the high mound, a step trench 12 x 20 meters was excavated down the northern slope (trenches 5072/3154, 5072/3164, and 5078/3154). In the step trench, Middle Bronze contexts were exposed below a single Late Bronze phase.

The Late Bronze Age phase, immediately below the site surface, is designated phase 1. Enigmatic clusters of baked brick fragments, broken grinding stones, and large sherds were characteristic of this context, as well as an area demarcated by a line of baked bricks on edge. Also found was a burial composed of a smaller lime-plastered pit inside a larger one. The small pit contained the disarticulated bones of two human skeletons, an adult and a child, and, to the north, a small squat jar and segments of at least four subadult sheep/goat (Fig. 12a–b).Footnote 14 To the east of the small pit was a short mudbrick wall.

Fig. 12. Phase 1, Late Bronze, High Mound North Slope. a. Pit burial; b. Jar from burial.

Discovered with the human bones inside the small pit were four unbaked or lightly baked clay human statuettes or figurines. Of these, the best-preserved was of a female with two bronze toggle pins criss-crossed on the torso (Fig. 13a).Footnote 15 The figurine had a pinched nose and ears, concentric circular eyes, pronounced breasts, no evident genitalia, and short rounded stump arms and legs. The pins had slightly swollen (globular?) heads and perforations 2 mm in diameter located 2.3 cm from the end of the head.Footnote 16 Notably, they were not scaled down to accommodate the size of the figurine but were instead of a size worn by an actual person. Perhaps they were used for a garment worn by the statuette. Also of possible significance is the echoing of the criss-cross pattern of the toggle pins in the arrangement of sheep/goat radii in the northern part of the burial.

Fig. 13. Clay figurines, Phase 1, Late Bronze pit burial, High Mound North Slope. a. KQ 17 H-10; b. KQ 17 H-11; c. KQ 17 H-12; d. KQ 17 H-13.

The three other figurines, all missing their heads, are apparently male. Like the female, one example (Fig. 13b) had rounded short stump legs and what seem to be short arms extending at right angles from the torso.Footnote 17 Two criss-crossing impressions on the torso are likely to derive from two toggle pins no longer present. Another figurine (Fig. 13c) had male genitalia and one short stump leg still extant.Footnote 18 The most poorly preserved of the group (Fig. 13d) consisted of a torso with the beginnings of two (stump?) arms and the base of a penis.Footnote 19 Whether these figures represent the individuals buried in the grave or have another significance is unclear. Parallels for this type of clay figure are rare in the Late Bronze period, but they recall the “stone spirits” found widely throughout west Asia in the second millennium B.C. (Carter Reference Carter1970; al-Maqdissi Reference Al-Maqdissi2007). Although the Kurd Qaburstan clay figurines date from a significantly later period, one might also compare examples found in graves of third millennium B.C. Syro-Mesopotamia (Peltenburg Reference Peltenburg2015: 190–191, pl. 46: 13–16).

Also notable from Late Bronze contexts in this area was a ceramic anthropomorphic gaming board segment (Fig. 14a). This object resembles the fiddle-shaped boards used for the game of ‘58 holes’ attested in the Levant and Nubia in its general layout and head-like appendage, which is perforated from side to side for suspension (de Voogt et al. Reference de Voogt, Dunn-Vaturi and Eerkens2013: 1721, fig. 5). However, the usual shape of fiddle-shaped boards is a figure eight, while the Kurd Qaburstan example is more lozenge-shaped. In 2014, another terracotta gaming board fragment was found in the latest LB phase on the High Mound North (trench 5088/3116), resembling boards for the game of ‘58 holes’ but with only three rows of holes instead of four (Fig. 14b).Footnote 20

Fig. 14. Fired clay gaming boards. a. (top) KQ 17 O-2, Phase 1, Late Bronze, High Mound North Slope. b. (bottom) KQ 14 O-4, Phase 2, Late Bronze, High Mound North.

Substantial architecture dating to the Middle Bronze period was identified below the LB remains on the High Mound North Slope in a deposit of at least four meters designated phase 2. To the north on the edge of the mound slope was a mudbrick wall at least 1.7 m wide with a possible tower preserved higher than the rest of the wall (Fig. 15). This wall is probably part of an enclosure wall encircling the high mound. Above the extant top of the wall was debris that included burned wooden beam segments and other ceiling material, suggesting that elements from burned structures higher on the mound slope had fallen on top of the brickwork.

Fig. 15. Plan of Phase 2, Middle Bronze, High Mound North Slope.

Such structures were identified in the southern part of the trench, forming a set of rooms with well-preserved, relatively thick mudbrick walls (c. 1.25–1.40 m wide) (Fig. 16). Two of those rooms, areas 1 and 2, included numerous fragments of burned construction materials like those found above the enclosure wall. It is likely that the architecture in this area was terraced down the mound slope.

Fig. 16. Photo of Phase 2, Middle Bronze, High Mound North Slope, Areas 2 (foreground) and 4 (rear), looking southwest.

The walls of areas 1–4 and the enclosure wall to their north were comprised of square bricks 40 x 40 cm or half bricks. Due to the walls’ relatively high preservation, excavation did not reach associated floors during 2017. These preliminary results from the High Mound North Slope indicate that the main occupation of this part of the site was Middle Bronze in date and included fortifications and a large-scale building.

Middle Bronze and Achaemenid Remains, High Mound South Slope (HMSS). In 2014, the High Mound South Slope had yielded two Middle Bronze phases relatively close to the site surface in trench 5065/2973. Given the accessibility of MB remains in this area, we expanded our sample of MB occupation in 2017, opening trench 5065/2985 (6 x 10 m) north of trench 5065/2973, with a 6-meter unexcavated area between. In trench 5065/2985 and the earlier trench 5065/2973, four phases were documented, consisting of phase 1 (vestigial Islamic remains), phase 2 (Achaemenid burials), phase 3 (MB), and phase 4 (MB).

In trench 5065/2985, phase 1 included a pit below the present-day surface in the western part of the trench. Several pit burials were assigned to phase 2; although none contained artifacts, their proximity to the Achaemenid Persian period burial excavated in 2014 suggests that their date is also Achaemenid (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017: 226–229).

The later Middle Bronze phase 3 in trench 5065/2985 had no substantial architecture, a situation also observed in phase 3 in trench 5065/2973 to the south. Remains that could be identified included clusters of baked bricks lying flat, perhaps working surfaces, and pebble surfaces. Also found, presumably intrusive but of Middle Bronze date, were the skeletal remains of a child underneath several large sherds of a ‘burial jar’ comparable to the example from the Lower Town North B trench 5134/3350.

In the earlier MB phase 4 was a set of rooms with walls of mudbricks that were typically 40 cm square or half that, as on the High Mound North Slope (Fig. 17). In area 6, a drain sunk vertically into the ground was composed of stacked piecrust potstands. Piecrust potstands had also been used as elements in a horizontal drain excavated in 2014 in the Lower Town North A (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017: 232). Installed at a later point than the original architecture in phase 4 was a pebble surface in the east, probably contemporaneous with two ovens intruding into the western corner of area 7. In both MB phases of trench 5065/2985 there was a notable frequency of grinding stones and other large objects of ‘synthetic basalt,’ i.e., ceramic slag produced to replicate basalt (Stone et al. Reference Stone, Lindsley, Pigott, Harbottle and Ford1998; Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017: 230).

Fig. 17. Phase 4, Middle Bronze, High Mound South Slope. Note 6 m distance between trenches 5065/2973 and 5065/2985 has been compressed in the figure.

Late Bronze Remains, High Mound East (HME)

After the MB occupation, most of the Kurd Qaburstan lower town was abandoned. The high mound became the locus of settlement in the succeeding LB period.Footnote 21 In much of the high mound, LB remains are immediately encountered below the present-day surface, as was the case on the High Mound North Slope.

In 2013–2014, a sequence of three LB occupational phases was documented in the High Mound East, designated 1–3 (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017). To continue investigation of this area, a 14 x 6 meter trench (5138/3051) was excavated north of trenches 5133/3044 and 5144/3044 from 2013–2014, with a 1-meter balk between (Fig. 18).Footnote 22 Directly below the mound surface were skeletal remains of two human adults without any associated material culture and thus of uncertain date; one was against the north balk of the trench (north of area 9) and the other in the southeast corner.

Fig. 18. Plan of Phase 3, Late Bronze, High Mound East.

Also in the southeast corner of the trench was an LB pit burial containing the body of a child under a cover of vertical mudbricks, perhaps to be dated to the latest LB phase 1.Footnote 23 The child was in a flexed position facing south and wore a bracelet and necklace of beads of carnelian, limestone, blue frit, shell, and other materials.

The Late Bronze architecture encountered below the site surface proved to be a continuation of the rooms excavated to the south in 2013–14 in phase 3, the earliest LB phase excavated. Presumably the architecture of phases 1 and 2 had been eroded in the area of trench 5138/3051, as had been the case in the western part of the High Mound East excavated area in 2013–14. Portions of four rooms were excavated (Figs. 18–19). Like the architecture to the south, the exposed rooms had diverse water control installations; in the easternmost area 11 was a jar sunk below the floor connected to a drain, while room 8 had a baked brick drain leading to the bath identified to the south in area 1 in 2014 (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017: fig. 13). Of unclear function is the feature or installation 10 inside the larger room 9, whose mudbrick walls were preserved c. 65–90 cm lower than the walls demarcating room 9.

Fig. 19. Photo of Phase 3, Late Bronze, High Mound East, Areas 7–11, looking northwest; wall in left foreground disturbed by later LB burial.

The baked brick baths, toilet, and wall thicknesses of this architecture suggest an elite character. Similar features are observable in the elite residential architecture at Nuzi, in the houses of Šilwa-Teššub and Šurki-Tilla (Starr 1937). Whether the excavated area is part of a single building or consists of parts of several edifices remains to be determined. Given the evidence of back-to-back walls between areas 2 and 6, 8 and 9, and 9 and 11, one might propose that rooms 2 and 9/10 were constructed first and the adjacent rooms 6, 8, and 11 added later.

Pottery and Chronology

The Middle Bronze Ceramic Assemblage

The 2016 study season and 2017 excavations allow for an enhanced understanding of the ceramic assemblage in second millennium B.C. Kurd Qaburstan. For the Middle Bronze period, an important addition to the ceramic corpus is a group of complete or near-complete vessels found on the floors of poorly-preserved rooms 3 and 4 (Fig. 8) in phase 2, the earlier of two MB phases excavated in the Lower Town North A trench 4870/3217 (Figs. 20–22). This corpus included large globular jars with ledge rims (Fig. 20: 1–7),Footnote 24 a tall, thin jar with ovoid body and flaring neck (Fig. 20: 8),Footnote 25 ledge-rim kraters (Fig. 21: 1–5),Footnote 26 large shallow bowls and other open forms (Fig. 22: 1–5),Footnote 27 a potstand (Fig. 22: 6), and a base with a ram's head spout (Fig. 22: 7).Footnote 28 The shallow bowls were often rough on the base exterior or the exterior lower body, as if scraped.

Fig. 20. Ceramics, Phase 2, Middle Bronze, Lower Town North A, Trench 4870/3217. Light yellow, medium vegetal inclusions unless otherwise specified. 1: KQ 14 4870/3217-052. KQ 16 P-18. Yellow-brown to red-brown, bitumen on exterior and interior, oval marks below the horizontal rope appliqués are impressions of string and/or knots used to support the jar during manufacture (Postgate et al. Reference Postgate, Oates and Oates1997: 68). 2: KQ 14 4870/3217-027. KQ 16 P-7. Bitumen on top of rim and on interior: two vertical bands and horizontal band below rim. 3: KQ 14 4870/3217-013. KQ 16 P-19. Bitumen on exterior and interior. 4: KQ 14 4870/3217-013. Bitumen blob on exterior below rim. 5: KQ 14 4870/3217-013. Bitumen blob on interior shoulder. 6: KQ 14 4870-3217-033. 7: KQ 14 4870/3217-052. 8: KQ 14 4870/3217-066. Exterior mottled yellow-gray to brown to pink.

Fig. 21. Ceramics, Phase 2, Middle Bronze, Lower Town North A, Trench 4870/3217. Light yellow, medium vegetal inclusions unless otherwise specified. 1: KQ 14 4870/3217-025. KQ 16 P-6. Pink-brown, band of bitumen 1.5 cm high at base on exterior, underside of base coated in bitumen. 2: KQ 14 4870/3217-046. KQ 16 P-5. Light yellow/green. 3: KQ 14 4870/3217-050. KQ 16 P-12. Light brown. 4: KQ 14 4870/3217-049. Light yellow. 5: KQ 14 4870/3217-081. Exterior/interior light yellow, core pinkish-brown.

Fig. 22. Ceramics, Phase 2, Middle Bronze, Lower Town North A, Trench 4870/3217. Light yellow, medium vegetal inclusions unless otherwise specified. 1: KQ 14 4870/3217-058. KQ 16 P-2. 2: KQ 14 4870/3217-070. 3: KQ 14 4870/3217-050. KQ 16 P-25. Pink-brown, medium vegetal inclusions and fine white sand. 4: KQ 14 4870/3217-046. KQ 16 P-13. 5: KQ 14 4870/3217-066. KQ 16 P-15. 6: KQ 14 4870/3217-050. KQ 16 P-16. Medium white sand. 7: KQ 14 4870/3217-015. Bitumen on interior near spout.

Many of the larger vessels in this group, as in the MB assemblage at Kurd Qaburstan in general, had evidence of bitumen application in streaks, bands or design motifs (Fig. 23a and b). This treatment was especially apparent on kraters with ledge rims and, to a lesser extent, jars. Bitumen was attested on vessel exteriors, interiors, tops of rims, and bottoms of bases.

Fig. 23. Large jar with bitumen application on exterior (a) and interior (b) (KQ 16 P-7, Fig. 20: 2).

In general, the Kurd Qaburstan MB assemblage seems relatively uniform, without conspicuous differences between phases or between excavation areas. Since there are many parallels between the assemblage and pottery from Mari and Leilan in the era of Shamshi-Adad and Zimrilim (see Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017 and notes here), a date in the middle MB seems likely.

The Late Bronze Ceramic Assemblage

A quantitative analysis of pottery from the three LB phases in the High Mound East has revealed a relatively homogeneous assemblage (Fig. 24).Footnote 29 However, some chronological changes can be observed, including a steady increase over time of plates/shallow bowls and of tall-necked jars with band rims. At the same time, types well-attested in MB contexts such as ledge-rim bowls and tall-neck jars with triangular section rims decline through the LB sequence. Tall-neck jars with block rims also exhibit a reduction through time.

Fig. 24. Selected Late Bronze ceramic types and their relative frequencies through time, High Mound East phases 1-3. Numbers in parentheses are raw counts. Post-phase 2 comprises contexts above the preserved architecture of phase 2, below phase 1 architecture.

A number of criteria lend support for dating of this assemblage to the early LB.Footnote 30 Gray Burnished Ware and Black Burnished White Paste Inlay Ware, sherds of which were found in numerous contexts, are dated by Pfälzner (Reference Pfälzner, al-Maqdissi, Matoïan and Nicolle2007) to early LB in the Syrian Jezireh (Middle Jezireh IA, ‘Early Mittani’). On the other hand, Red-Edged Bowls, represented by only one example from the latest phase (1) on the High Mound East, are assigned by Pfälzner to Middle Jezireh IB (‘Later Mittani’). Dark on Buff Animal Ornamented Ware, dated to early LB in Pfälzner's chronology, was represented by one sherd from the earliest LB phase (3) on the High Mound East.

The rarity of Nuzi Ware might also support an early LB date for our assemblage, comparable to the scarcity of this ware in the early LB stratum III at Nuzi itself (Oguchi Reference Oguchi and Özfırat2014), dated by Novák (Reference Novák, Bietak and Czerny2007) to c. 1525–1440 B.C. At Kurd Qaburstan, only two Nuzi Ware sherds have been recovered, one from the High Mound East phase 1 (Schwartz Reference Schwartz, Kopanias and MacGinnis2016: fig. 10: 3), the other from the earlier of two LB phases excavated in the High Mound North. Nuzi Ware does not appear at Nuzi in large numbers until stratum II (Stein Reference Stein1984; Novák Reference Novák, Bietak and Czerny2007: 392; Oguchi Reference Oguchi and Özfırat2014: 219).

An assemblage comparable to the Kurd Qaburstan LB corpus has been identified at the 10-hectare site of Helawa, seven km west of Kurd Qaburstan. Among the numerous characteristics the Helawa VI corpus shares with Kurd Qaburstan (Oselini 2020: 213–216) are Younger Khabur Ware (Peyronel et al. Reference Peyronel, Minniti, Moscone, Naime, Oselini, Perego and Vacca2019: fig. 74: 2–3, 7; fig. 79: 1–2), Gray Ware carinated bowls, some with white paste inlay (Peyronel et al. Reference Peyronel, Minniti, Moscone, Naime, Oselini, Perego and Vacca2019: fig. 74: 13, 16; fig. 79: 12–14), block rim bowls and kraters (Peyronel et al. Reference Peyronel, Minniti, Moscone, Naime, Oselini, Perego and Vacca2019: fig. 74: 11, 17, 19–20; fig. 80: 7, 10), ring-based carinated bowls with vertical upper bodies (Peyronel et al. Reference Peyronel, Minniti, Moscone, Naime, Oselini, Perego and Vacca2019: fig. 80: 4–5), and Cooking Ware pots with everted rims (Peyronel et al. Reference Peyronel, Minniti, Moscone, Naime, Oselini, Perego and Vacca2019: fig. 80: 13). Rare at Kurd Qaburstan, Nuzi Ware is not attested at all at Helawa. Given its ceramic comparability with the Kurd Qaburstan LB, Helawa VI is also likely to date to an early LB time frame (Peyronel et al. Reference Peyronel, Minniti, Moscone, Naime, Oselini, Perego and Vacca2019: 14).Footnote 31

Radiocarbon Analysis

A preliminary series of radiocarbon (14C) dates from Kurd Qaburstan was recently measured at the AMS laboratories of the University of Groningen and ETH Zürich. Representing both MB and LB strata, the samples comprise archaeobotanical materials acquired via flotation during the 2014 and 2017 seasons.Footnote 32 The independently calibrated dates are shown in Fig. 25a, and a summary of outcomes obtained by Bayesian analysis appears in Fig. 25b. The latter is briefly discussed here and presented in more detail in Webster et al. Reference Webster, Smith, Dee, Hajdas and Schwartzforthcoming.

Fig. 25. a) Independently calibrated radiocarbon dates from Middle and Late Bronze Age horizons of Kurd Qaburstan (1σ and 2σ probability ranges indicated). b) Transitions between phases as estimated using Bayesian analysis. 14C analysis utilized OxCal software (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and the latest calibration curve (IntCal 20; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey and Butzin2020).

The MB dates derive from burned contexts associated with the large-scale architecture on the High Mound North Slope (three measurements) and from the western of two ovens in phase 2, area 5 of trench 4870/3217 on the Lower Town North A (one measurement). The four results are consistent, falling in the 18th and 19th centuries B.C. (Fig. 25a, between 1890 and 1745 B.C. at 68.3% probability). LB samples derive from the High Mound East, representing ashy deposits or occupation debris of phases 3 and 1, as well as ashy material that separated phases 2 and 1. Overall, the LB results indicate occupation in the second part of the 16th century B.C. and the 15th century B.C. (Fig. 25a). One date (GrM-19818, Phase 3) appears to be an outlier.

Taking into account both the radiocarbon results and the relative stratigraphic order of samples, a Bayesian analysis allows us to further refine the chronology of Kurd Qaburstan's MB and LB occupation.Footnote 33 Fig. 25b shows the phase boundaries calculated by a simple Bayesian model that imposes the order of High Mound East phases 3–1 (LB); the MB samples are assumed to pre-date these, based on stratigraphy and unambiguous pottery differences. Since only a single MB phase has thus far been datedFootnote 34 and is followed by a substantial time gap, Bayesian analysis is unable to narrow the estimate substantially; the phase extends from the second part of the 19th through the first part of the 18th century B.C. (68.3% probability). The destruction/abandonment of the MB city – suggested by burning on the High Mound North Slope and a large assemblage of in situ pottery from the Lower Town North A phase 2 – can be estimated at 1805–1734 B.C. (68.3% probability). More effectively refined by Bayesian modelling is the absolute dating of LB occupation, thanks to the series of three phases. The earliest known phase (3) is placed in the range 1538–1491 B.C., phase 2 at 1512–1479 B.C. and phase 1 at 1489–1434 B.C. (all cited at 68.3% probability).

Chronological Implications

The 14C outcomes for MB Kurd Qaburstan fit comfortably with the “middle” MB date indicated by the ceramic assemblage. Further, this absolute dating would accord well with the proposed identification of Kurd Qaburstan with ancient Qabra, whose defeat by Shamshi-Adad and Dadusha is datable to c. 1800 B.C. and whose mention in the time of Zimrilim of Mari (early 18th century B.C.) under the rule of the king Ardigandi marks its latest appearance in the textual record (Charpin Reference Charpin, Marti, Nicolle and Shawaly2015; Ziegler Reference Ziegler, Marti, Nicolle and Shawaly2015). The question of how early the MB city began must remain an open question until more detailed 14C data are obtained from multiple MB phases; as noted above, up to four MB phases are known from trenches and probes in the lower town.

14C outcomes for the LB clearly support our attribution of the pottery to the early part of this period. Indeed, the 16th to 15th century B.C. dates imply that High Mound East phases 1–3 precede the era of Mittani control. It is probable that Ashur, to the southwest of Kurd Qaburstan, and the Erbil region were not subjugated by Mittani until the reign of Sauštatar in the later 15th century (Llop Reference Llop2011; MacGinnis Reference MacGinnis2018). The 16th century B.C. date of phase 3, definable ceramically as early LB, shows that the LB must have commenced before 1500 B.C., contrary to the estimate promoted by the Ultra-Low Chronology. Note that it is still uncertain whether phase 3 is the earliest LB horizon, since excavation in the High Mound East has not yet progressed below it.

The gap of some 200 years between the 14C-based dates of MB and LB strata (assuming GrM-19818 is indeed an outlier) needs further investigation to ascertain the degree to which it represents a real hiatus in occupation or a lack of data. Until excavation in the High Mound East progresses deeper, we cannot rule out the presence of additional (as yet undated) late MB and/or early LB phases.

Faunal Analysis

Animal bones from the 2017 excavations were analyzed in the field by Jill Weber. A total of 2433 individual specimens (NISP – bones independent of each other) were analyzed, dating to the Middle Bronze (n=1749), Late Bronze (n=350), and Late (mainly Islamic, n=334) (Fig. 26). Preservation was poor, with much encrustation and damage from modern cultivation. This particularly affected Middle Bronze remains, since many of these derived from the lower town, which has undergone the most cultivation and damage. Overall, sheep and goat clearly dominated all assemblages (Fig. 27), as was the case in the results from earlier seasons (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017).

Fig. 26. Number (NISP) of animal bones per period.

Fig. 27. Comparison of relative abundance of major faunal taxa. Sh/gt – sheep/goat, bos = cattle.

Middle Bronze Contexts

The Middle Bronze assemblage is dominated by sheep and goat (c. 65%), marked by a relatively large proportion of pig (c. 28%), and rounded out by cattle (c. 7%). Compared to the contexts analyzed previously, there are relatively more sheep and goat (compared to 55%) and fewer cattle (compared to c. 12%). Of four equid bones identified, one astragalus was morphologically identified as donkey, while two others were also considered to be donkeys by virtue of their small size. The 11 canid bones were from a minimum of two dogs, with adult bones and one puppy bone identified. Wild animals were rare and manifested by bones of gazelle (n=11), fox (n=2), hare (n=3), and reptile (n=1).

Compared to data from MB assemblages from earlier field seasons, there were relatively more sheep and goat. Moreover, there was a greater abundance of goat (n=31) relative to sheep (n=19). A previously excavated kitchen/food preparation area in the Lower Town North A revealed more sheep (n=16) than goat (n=11) among its bones (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017: 31). By contrast, assemblages from the High Mound South Slope had many more goat (n=15) than sheep (n=1). From the current analysis, the two Lower Town North trenches had many more goat (n=20) than sheep (n=8) among their remains, while the High Mound South Slope was roughly equal. Similar to earlier findings, about 50% of animals lived to approximately their fourth year (Fig. 28). The percentage of fused bones is a proxy for the percentage of animals that survived beyond a given age class. The teeth add additional data for the earlier age classes and provide the only evidence for ages past 48 months. An approximation between the percentage of fused bones and the percentage of teeth in each class indicates the percentage of animals surviving that age class. Data from teeth and bones are largely complementary. Small differences reflect variations in preservation between bones and teeth and small sample size. Neither teeth nor bones provide precise age data, and the most accurate approximation is gained by using both lines of evidence. These variations in the relative numbers of sheep and goat but similarity in culling age suggest that the difference in that measure is contextual, rather than purely spatial. In other words, there was not a strong preference for either sheep or goat in different parts of the MB community.

Fig. 28. MB age data, sheep/goat. u = unfused articular ends, f = fused articular ends. The row of cells indicates the number of each. The ‘teeth’ row of cells indicates the percentage surviving each age class (“1” = 100% and indicates no teeth from an individual of that age were recovered, 0.83 = 83% of animals that age survived, etc.).

A total of 142 pig bones were identified in the MB assemblage. Age data indicate that some animals were killed at sexual maturity (c. 7–8 months), but many more lived longer, at least until c. two years of age (Fig. 29). The same methodology of survivorship approximation was used for pigs as for sheep/goat (above). Notably, there were few skull bones and teeth; since such bones are dense and easily recognizable, their absence is probably not related to biases of preservation. Pigs were exploited for meat and fat, either of which could be indicated by the remains. However, this limited range of elements might indicate that pigs were acquired from elsewhere and not raised or butchered in these contexts.

Fig. 29. MB Pig fusion data. u = unfused articular ends, f = fused articular ends.

Four bones showed evidence of intentional modification. Two sheep or goat astragali (#1548, #1549, Lower Town North A, 4870/3225-018) had been shaped by flattening their sides, a common practice to modify astragali into gaming pieces such as dice. Neither bone had been completely modified before discard. A radius bone from either a sheep or goat had been shaped into a point and used, as indicated by the polish on the point (#2088, High Mound South Slope, 5065/2985-046). This was an informal tool that was selected, used, and discarded within a short time. While shaped astragali and expedient tools had previously been recovered from MB contexts at Kurd Qaburstan (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017: 32), a ‘formal’ item recovered in the 2017 excavations was a pin (#2968, Lower Town North B, 5134/3350-026) with a shaped, smoothed, and polished tip that had broken in antiquity and been discarded. The item likely derived from a large-sized mammal metapodial. While numerous such implements have been found in LB contexts, this is the first to be recovered from an MB locus.

Analysis of MB contexts was hampered by poor preservation. In many cases, the bones had a heavy encrustation of dirt and salts that rendered identification difficult and examination of surface treatment impossible. Most affected were deposits from the Lower Town North, located in an area of long-term cultivation. For example, only the densest pig and cattle bones were recovered from the stratigraphic unit 4870/3225-002. Since these were heavily encrusted, it seems probable that less dense bone failed to survive the inhospitable soil environment.

While that preservation problem undoubtedly formed over the centuries after the bones had been buried, a second type of problem was caused in antiquity. Many MB deposits excavated on the Lower Town North B appear to have derived from external surfaces (e.g, Trench 5134/3350-027, 028, 029, 049; phase 3, south part of trench). The bones were heavily fragmented into small pieces, with many refits possible, indicating that breakage occurred in situ, possibly within a trampled surface. In addition, some bones had weathered surfaces and breaks. No evidence of gnawing was apparent, and burning was limited to bones in units 028 and 049. Within these assemblages, bones of younger animals are evident. Because of the heavy fragmentation, a distinctive identification pattern emerged; it was easier to identify genus (typically as ‘Ovis or Capra’) from teeth or phalanges than from long bones or axial elements, which were mostly limited to size and class (almost all were ‘medium-sized mammal’). We suggest, then, that whole animals were present in this area, which may have served as a primary butchery location. Presumably, the recorded prevalence of skull and extremity bones is an artifact of post-depositional fragmentation (trampling) and possibly pre-depositional fragmentation.

Late Bronze Contexts

Relative to other periods, there is a greater proportion of cattle and lesser relative abundance of sheep and goat in the LB contexts. Cattle account for c. 20% of the assemblage, as do pig, while sheep and goat comprise c. 60% of the bones. Compared to the results from earlier seasons (in which 45% of the bones were identified as sheep and goat), these LB contexts contain more sheep and goat and far fewer pig remains (compared to c. 40% from earlier seasons). The relative abundance of cattle is much the same.

Age data from 31 bones and teeth of sheep and goat indicate that many animals were culled young; of those recovered, roughly half may have been killed by 2 years of age, and only a small percentage lived to 4 years (Fig. 30). The same methodology of survivorship approximation was used as for MB sheep/goat (above). These data do not diverge strongly from assemblages recovered from LB levels excavated earlier. In those, more animals lived to roughly 3–4 years, but few lived beyond that age. Regardless, the lack of both very young and very old animals suggests that the LB contexts excavated on the High Mound in 2017 were areas of consumption rather than production, which makes sense given their central location. Otherwise, the slight shift in age could indicate shifts in offtake strategy by herders, possibly as a result of annual or seasonal variation in climate, commodity demand, or political activity.

Fig. 30. LB age data, sheep/goat. u = unfused articular ends, f = fused articular ends.

For pig, 26 bones were identified. Aging data were minimal but suggest that some animals were killed just after reaching sexual maturity, around 6–7 months. Many animals survived beyond this age and were killed around 3–4 years of age. This pattern marks a distinct difference from the pig assemblage recovered from earlier seasons, in which few pigs lived beyond one year of age. The difference in culling age, as well as the lesser relative abundance of pig overall, may indicate diversity in either the value or purpose of pigs across space or over time, or simply functional differences between contexts. The large number of young piglets previously recovered was linked to possible elite contexts on the High Mound North, as pig's fat was a valued commodity in the contemporary Nuzi period (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017: 34). The dearth of pigs – and particularly piglets – in the current assemblage may indicate that these were resources that were regulated and controlled by elite households that are not represented in these current assemblages.

Cattle bones (n=27) comprise c. 20% of the LB assemblage – roughly the same as previously excavated LB materials. These bones were heavily fragmented. With a single exception, all the bones belonged to adult animals. The exception was an animal that died around 4 years of age. However, this animal's femur had an abscess that may indicate disease, ill health, or poor treatment in life that resulted in its death rather than intentional culling of a young, valuable animal. This bone also showed evidence for carnivore gnawing, and it is possible that the individual was killed by dogs, given its potential weakness. A metapodial bone was recovered from the High Mound East (5138/3051-011 #2241, debris above architecture in south central part of trench) that is consistent with debris previously recovered from a probable workshop from phase 2 in the High Mound East (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017: 33-4). This workshop specialized in the cutting and polishing of cattle and equid bones into a specific type of implement – long pins. The metapodial recovered in 2017 had its distal articulation sawn off in the same fashion as the worked debris recovered from the workshop.

Equid bones (n=9) from at least two donkeys (based on their small size) were identified, and one of the bones had been shaped into an implement (#2456). This bone, a metapodial, had been formed into an awl with the distal end of the bone left as a handle and a thick point (broken) produced in the central shaft. Recovered from the High Mound North Slope [5078/3154-026], this broken implement provides a newly-attested use and location for equid bone as a raw material at LB Kurd Qaburstan. Previously, equid bone as a raw material was only known from the workshop discussed above. In the LB contexts, wild animals were rare and were attested by bones of gazelle (n=2), birds (n=2), and reptiles (n=3).

Islamic Contexts

In this period, sheep and goat (n=57) accounted for over 80% of the assemblage relative to the major taxa recovered, i.e., sheep, goat, pig, and cattle. Teeth from five different animals indicate that their deaths occurred across a large range of ages: two between c. 6–12 months, two between 3–4 years, and one c. 4–6 years of age. Few bones of pig (n=4) were identified, possibly a result of the pork taboo within Islam, although reduction in pig exploitation could have numerous causes. All pig bones recovered derived from adult individuals. Cattle, too, are represented by few, heavily-fragmented bones (n=7). Bones from a minimum of 2 equines were recovered. Of these, a full set of teeth indicates a 2.5–3.5 year old animal (donkey?) just ready to shed its deciduous premolars with no 3rd molar yet visible, while a fully-fused first phalange indicates an adult donkey. Birds (n=4), fox (n=2), and gazelle (n=2) were also present.

Discussion

Kurd Qaburstan encompassed a large occupied area, particularly in the Middle Bronze occupation but also applicable to the Late Bronze settlement. While only a small proportion has so far been excavated, the 2017 findings largely validate those of 2013 and 2014. Specifically, sheep and goat were heavily exploited in all periods relative to other animals. Pig and cattle vary in relative abundance over time but represent a primary focus within the animal economy, while wild animals are nearly absent.Footnote 35 Within the LB deposits, more evidence was uncovered in 2017 supporting a specialized bone-pin workshop on the High Mound East. This, together with indications that pig exploitation may have varied significantly by context, suggests a high-degree of spatial segregation (and thus specialization) within the Late Bronze settlement. While a larger number of bones have been analyzed from Middle Bronze deposits, we can only make very general statements about the exploitation of animals and use of bones. In general, the MB assemblage indicates less formal divisions between areas – relative to the Late Bronze – and shows greater informality in the use of raw materials. This may be due, in part, to the large sample of lower town contexts relative to the potentially more centralized upper town contexts that have been excavated. Regardless, there is much more to be uncovered and learned.

Archaeobotanical AnalysisFootnote 36

Methods

During the 2017 season, 34 archaeobotanical samples were collected spanning the MB (n = 21), LB (n = 12), and Islamic Period (n = 1). A total of 242 litres of sediment was floated, with sediment volume per sample varying between 2 and 12 L with a mean of 7 L (Table 2). Prior to flotation, a small scoop of sediment was collected from each sample and stored for future starch grain, phytolith and spherulite analysis. Sediment samples were processed in the field using a bucket flotation system. Light fractions were dried in the shade before being transported to the Archaeobotany Laboratory at the University of Connecticut for analysis. After flotation in the field, some samples still contained sizeable amounts of fine-grained sediments, so samples were refloated/washed in the lab by Geoffrey Hedges-Knyrim. Resultant light fractions were then sieved using 4 mm, 2 mm, and 1 mm sieves and were scanned for taxa present. All seeds, fragments, and plant parts were identified to the most specific taxonomic rank possible using the reference collection in the Archaeobotany Laboratory at the University of Connecticut, which is rich in flora from Southwest Asia. Various flora, seed identification manuals, and archaeobotanical reports were also used to assist with identifications and provide ecological and ethnobotanical information (e.g., Bor Reference Bor1968; Davis Reference Davis1965–1985; Townsend and Guest Reference Townsend and Guest1974; Nesbitt Reference Nesbitt2006; van Zeist and Bakker-Heeres 1984 (Reference van Zeist and Bakker-Heeres1986), 1985 (Reference van Zeist and Bakker-Heeres1986)). This report provides presence/absence data gathered during the first sorting phase (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 2. Contextual information for MB, LB, and Islamic archaeobotanical samples.

Table 3. Contents of Middle Bronze Age archaeobotanical samples (x = present; xx = present in greater than normal abundance). Contextual information for each sample is provided in Table 2.

Table 4. Contents of Late Bronze Age archaeobotanical samples (x = present; xx = present in greater than normal abundance). Contextual information for each sample is provided in Table 2.

Many samples were dominated by modern plant materials (rootlets and sometimes seeds), owing to the shallow depth of many of the excavated strata. Some samples, including the sole Islamic period sample recovered from pit fill (5065/2985-005, 007, 014 #9) were sterile. The bioturbation caused by modern plant growth appears to have negatively impacted preservation of some samples, but cultural factors relating to plant deposition and charring in antiquity could also be important. Despite the overall paucity of charred remains, a number of interesting observations can still be made.

Middle Bronze Plant Remains

All 21 samples dating to the Middle Bronze Age were examined. Six samples collected from 4870/3225 in the Lower Town North A included debris above a pebble surface, the contents of an oven, and sediment close to grinding stones (Tables 2 and 3). All light fractions contained numerous modern rootlets and had been impacted by bioturbation. Three of the samples from 4870/3225 were essentially sterile. However, as excavations progressed and the lower part of an oven (4870/3225-009, #10) was excavated, slightly more charred remains were recovered. Included were several Hordeum sp. (barley) and Triticum sp. (wheat) grains, poorly preserved cereal grain fragments that could not be identified to genus, and a single lentil (Lens culinaris). Several wild grasses, including wild Hordeum sp. and Lolium sp. were also encountered in the oven. In general, however, the contents of the samples from this trench were sparse. Similar assemblages were recovered from MB tannurs at Helawa, although Aegilops and a variety of small grasses and field legumes were also found (Peyronel et al. Reference Peyronel, Minniti, Moscone, Naime, Oselini, Perego and Vacca2019: 92). The three samples from trench 5134/3350 on the Lower Town North B were similarly sparse, containing isolated cereal remains and small wood fragments that likely represent background noise (Table 3). On the High Mound North Slope, three samples recovered from trench 5072/3164 and a single MB sample from trench 5072/3154 all appear to represent building collapse (Table 3). The samples contained very little modern contamination and were dominated by large concentrations of wood fragments, suggesting a catastrophic fire. Identification of the wood is ongoing, but it is clear that each sample contains a single species that provided either roofing material or support within a structure.

Eight samples were examined from trench 5065/2985 on the High Mound South Slope, representing domestic sediments including contexts associated with an oven, a grinding stone, and a ceramic drain (Table 2). While densities of plant remains in this area remained fairly low, a wider range of taxa was recovered, including Hordeum sp. and Triticum sp. Unfortunately, the preservation conditions did not allow for species level identifications of these cereals, and too few grains were recovered to infer relative abundance. A few chaff remains were also recovered, including Hordeum rachis fragments, Triticum glume bases (presumably from Triticum dicoccum, emmer), and several culm fragments. Weedy taxa included Aegilops sp. (goat grass, as grain and glume bases), Alopecarus sp., wild Hordeum sp., Lolium remotum type, Echium sp., Bulboschoenus sp., and Malva sp. Small amounts of wood fragments were also present, along with a possible dung pellet fragment.

A number of wild plants recovered from 5065/2985 may have been consumed or used by the MB inhabitants, including Capparis sp. (caper), a member of the Brassicaceae (Cruciferae/mustard) family, and Malva sp. (a mallow—while only seeds were recovered, the flowers are beautiful and the roots can be used for a wide range of ailments, including treating joint pain). Brassica/Sinapsis remains have been encountered at other sites across the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, including Late Neolithic Tepe Marani (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Wengrow, Saber, Hamarashi, Shepperson, Roberts, Lewis, Marsh, González Carretero, Sosnowska, D'Amico, Sagan and Lockyear2020) and fourth millennium B.C. levels at Gurga Chiya, both within the Shahrizor Plain (Wengrow et al. Reference Wengrow, Carter, Brereton, Shepperson, Hamarashi, Saber, Bevan, Fuller, Himmelman, Sosnowska and Carretero2016). Brassicaceae finds were also reported from Surezha, a small mounded site located just northeast of Kurd Qaburstan, dating from the Ubaid period to the Late Chalcolithic 2–3 (Proctor Reference Proctor2021), suggesting that they are a common feature of archaeobotanical assemblages across the region.

Fruit use is minimally attested at MB Kurd Qaburstan. Several Ficus carica (fig) seeds were recovered from two domestic samples within trench 5065/2985 (-032 #11, and -069 # 35); fig appears to have been commonly consumed across northern Mesopotamia for some time (cf. a large cache of mineralized fig seeds found at Surezha within a Late Chalcolithic 1–2 context interpreted as a feasting pit; Proctor 2021). Helbaek (Reference Helbaek and Mallowan1966) also reports fig, date, olive, pomegranate, and cucumber from later Assyrian periods at Nimrud. At Tell Taya, Vitis vinifera (grape) and Olea europea (olive) were identified in an Akkadian period oven. To date, with the exception of fig, none of these taxa have been recovered from Kurd Qaburstan (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017), Helawa (Peyronel et al. Reference Peyronel, Minniti, Moscone, Naime, Oselini, Perego and Vacca2019), or nearby Surezha (Proctor 2021).

In recent years, archaeobotanists have been working to expand the range of charred remains that can be identified from flotation samples, moving beyond seeds and plant parts to include fragments of prepared foods. A number of scholars are now focusing on bread and processed cereals (e.g., Arranz-Otaegui et al. Reference Arranz-Otaegui, Carretero, Ramsey, Fuller and Richter2018; González Carretero et al. Reference González Carretero, Wollstonecroft and Fuller2017; Heiss et al. Reference Heiss, Pouget, Wiethold, Delor-Ahü and Goff2015; Popova Reference Popova, Bacvarov and Gleser2016). The earliest positively identified bread to date was recovered from Shubayqa 1, a hunter-gatherer site located in Jordan dating to 14,400 years ago. It is highly likely that bread and cereal-based foods are ubiquitous at many sites across Southwest Asia from the Neolithic onwards (and even earlier), but scholars are only now beginning to recognize them. Two MB samples within Kurd Qaburstan trench 5065/2985 on the High Mound South Slope from around an oven (5065/2985-032, #11) and near a grinding stone (5065/2985-039, #16) contain remnants of a dough/bread-like substance. Both fragments were initially examined using low-powered microscopy, and their identification was confirmed using scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 31). The remains were compared with a modern charred bread reference collection within the Archaeobotany Lab at the University of Connecticut that contains both leavened and unleavened breads baked using different cereal taxa. Within the matrix of the MB remnants, the size of the voids suggests that they were ‘flat(ish)’ breads that could have been cooked on a tannur wall but also may have experienced some gentle leavening through natural yeasts. A similar process is observable in naan bread, although manufactured raising agents are frequently added today. Remnants of flat bread have also been reported at Gurga Chiya and Tepe Marani on the Shahrizor plain within levels spanning the Late Neolithic, Late Ubaid, and LB periods (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Wengrow, Saber, Hamarashi, Shepperson, Roberts, Lewis, Marsh, González Carretero, Sosnowska, D'Amico, Sagan and Lockyear2020; Wengrow et al. Reference Wengrow, Carter, Brereton, Shepperson, Hamarashi, Saber, Bevan, Fuller, Himmelman, Sosnowska and Carretero2016).

Fig. 31. Scanning electron microscope images of a charred food fragment (likely a gently-leavened bread) from an area around an MB oven in 5065/2985 (Archon 032, #11).

Late Bronze Plant Remains

Late Bronze samples were collected from two different trenches (5078/3154 and 5138/3051). Very few charred plant remains were recovered from within 5078/3154 on the High Mound North Slope (5078/3154-006, #15 and -007, #17) and the animal bone deposit within a grave (5078/3154-017, #22). The light fractions of all three samples were dominated by fine modern rootlets and modern Malva sp. seeds and can essentially be considered sterile, although sample 17 contained 8 small wood fragments and several fragments of wild Hordeum caryopses. The number of modern Malva sp. seeds in some of the samples was striking. While modern bioturbation undoubtedly affected preservation, the relative paucity of charred remains associated with an installation demarcated by a line of baked bricks on edge suggests that the area did not experience sustained charring that would have been conducive to preservation of macro-botanical remains. Future examination of phytoliths within the sediment samples can further assess whether the installation was related with plant use in any way. The third LB sample, collected from an animal bone deposit within a grave, contained several bone fragments alongside poorly preserved charcoal that included several Triticum glume bases.

The nine Late Bronze Age samples from trench 5138/3051 on the High Mound East yielded more charred plant remains on the whole relative to those from 5078/3154, reflecting some similarities with the MB domestic remains from 5065/2985 (Table 4). Most samples contained small amounts of wood. Cereal remains included several Hordeum sp., Triticum dicoccum, Triticum durum/aestivum (bread/durum wheat) grains, indeterminate cereal grain fragments, and sporadic emmer glume bases, free-threshing Triticum rachises, a Hordeum rachis, and several culm (stem) fragments. Several remnants of bread were also recovered from the LB room 9 (5138/3051-021 #7, -038 #30, and possibly -041 #33).

Within all nine samples from 5138/3051, only one Lens culinaris cotyledon and one fragment of a poorly preserved large legume were recovered. Neither Vicia ervilia nor Pisum sativum were observed in any of the archaeobotanical samples examined here, although isolated finds of Vicia ervilia and Lathyrus sp. were recovered from MB and LB levels during the 2014 season (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017). Mundane, everyday preservation biases tend to result in preferential preservation of cereals relative to legumes across Southwest Asia, so it is possible that legumes exist elsewhere on the site where more catastrophic or preferable preservation conditions occurred, but it also plausible that additional cultural factors relating to shifts in plant use are at play. The rarity of legume finds at LB Kurd Qaburstan mirrors other LB evidence in the region, providing a strong contrast with earlier practices across the region. Within Late Neolithic samples from Tepe Marani, Ubaid samples from Gurga Chiya and Helawa, and Ubaid and Late Chalcolithic samples from Surezha, legumes are generally much more abundant and ubiquitous, sometimes dominating sample assemblages (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Wengrow, Saber, Hamarashi, Shepperson, Roberts, Lewis, Marsh, González Carretero, Sosnowska, D'Amico, Sagan and Lockyear2020; Peyronel et al. Reference Peyronel, Minniti, Moscone, Naime, Oselini, Perego and Vacca2019; Proctor 2021).

Additionally, a general paucity of chaff in LB samples has been noted at other sites including Surezha (Proctor 2021) and may relate to a broader regional shift in plant use whereby crop processing was not as intensive on-site relative to earlier time periods. Analysis of phytoliths within the sediment samples would be helpful to confirm this, since the preservation of phytoliths within chaff is not subject to the vagaries of charring. Comparable remains recovered from an LB oven at Gurga Chiya dating to the 14th or early 13th centuries cal. B.C. also yielded low density charred remains consisting of weedy taxa, wheat, barley, lentil, bitter vetch (Vicia ervilia), and cf. Pisum sativum (Wengrow et al. Reference Wengrow, Carter, Brereton, Shepperson, Hamarashi, Saber, Bevan, Fuller, Himmelman, Sosnowska and Carretero2016). The LB oven at Gurga Chiya also contained a well preserved Panicum miliaceum (millet) grain and two possible melon seeds (cf. Cucumis melo), neither of which is currently attested at Kurd Qaburstan (Wengrow et al. Reference Wengrow, Carter, Brereton, Shepperson, Hamarashi, Saber, Bevan, Fuller, Himmelman, Sosnowska and Carretero2016). In contrast, however, plant remains recovered from LB tannurs at Helawa contained a variety of cereal grains (including sizeable amounts of Hordeum vulgare, Triticum dicoccum, and T. aestivum/durum grain along with numerous wheat and barley chaff parts), a variety of abundant weeds, and sheep and goat dung pellets, collectively suggesting the use of dung fuel (Peyronel et al. Reference Peyronel, Minniti, Moscone, Naime, Oselini, Perego and Vacca2019). It is possible that differing cleaning practices partially contributed to the difference.

Although the range of wild taxa recovered from trench 5138/3051 was the most varied of the 2017 archaeobotanical corpus, relatively few remains were present. Wild taxa included Aegilops sp. grain and glume bases, a range of wild grasses (Alopecarus sp., cf. Eremopyron sp., wild Hordeum sp., Lolium remotum type, Phalaris sp., Stipa sp., and small grasses <1mm), several small legumes (Coronilla sp. and Trigonella astroites type), Rumex sp., and finds belonging to the Brassicaceae/Cruciferae (mustard) family. While many of these species can occur as field weeds, they are frequently found in pasturelands and are therefore widely consumed by animals. In general, the wild/weedy seeds were concentrated in ashy areas within the room fill. It is possible, therefore, that they represent the remains of spent dung fuel. The use of dung fuel at Kurd Qaburstan is well-attested given the observations of dung spherulites from samples excavated during the 2014 season (Proctor 2021; Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Brinker, Creekmore III, Feldman, Smith and Weber2017).

Discussion

While the density of plant materials recovered from MB and LB levels at Kurd Qaburstan was low, the charred macro-botanical remains are informative and provide new insights into the distribution of charred bread. Preservation appears to be an issue in some samples, particularly those excavated close to the modern surface, yet others contained well-preserved charred remains, indicating the preservation potential at the site. Considering other reports of similar LB remains across the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, it would appear that the overall low density of plant remains at Kurd Qaburstan cannot be attributed to post-depositional factors alone. It is possible that regional cultural factors relating to the nature and location of plant processing, plant use, and repeated exposure to fire during the MB and LB also influenced the assemblages. Further work at other sites is needed to determine whether substantial shifts in crop processing and plant use did indeed occur though time. The inclusion of micro-botanical studies will also remain important.

Conclusions

The 2016–2017 fieldwork at Kurd Qaburstan produced a number of significant results. We may now provisionally date the foundation of the lower town and the expansion of the site to a sprawling 95-hectare city to the Middle Bronze period. Additional evidence of a major Middle Bronze presence is now available from the High Mound North Slope, with fortifications and substantial adjacent architecture, and from the Lower Town East, with a monumental temple. These data reveal that the Middle Bronze Age was the major period of occupation at Kurd Qaburstan and that large-scale urban activities occurred at the site during that period. The geophysical results continue to demonstrate that the Middle Bronze community was not a “hollow city” (Ur et al. Reference Ur, de Jong, Giraud, Osborne and MacGinnis2013: 100) but was densely occupied.

Given the chronological results attained thus far, we may posit that these developments occurred when Kurd Qaburstan was part of the kingdom of Qabra and, temporarily, part of the upper Mesopotamian state fashioned by Shamshi-Adad. Whether Kurd Qaburstan is to be identified with ancient Qabra is still uncertain, but the evidence obtained thus far is consistent with that proposition. The MB results, when merged with new data from excavations elsewhere in upper Mesopotamia such as Helawa, Aliawa, and Qasr Shemamok on the Erbil plain (Masetti-Rouault Reference Masetti-Rouault, Otto, Roaf and Kaniuth2020; Peyronel et al. Reference Peyronel, Minniti, Moscone, Naime, Oselini, Perego and Vacca2019; Rouault Reference Rouault, MacGinnis, Wicke and Greenfield2016), Gir-e Gomel on the Navkur plain (Morandi Bonacossi et al. Reference Morandi Bonacossi, Qasim, Coppini, Gavagnin, Girotto, Iamoni and Tonghini2018), and Bassetki and Kemune in the middle Tigris (Pfälzner and Qasim Reference Pfälzner and Qasim2020; Puljiz and Qasim Reference Puljiz and Qasim2019), can be expected to yield new perspectives on early second millennium B.C. urban and socio-political developments.

In the succeeding Late Bronze period, we are now aware that occupation on the high mound of Kurd Qaburstan dates to early LB, perhaps preceding the imposition of Mittani control in the region. As with MB, the new results, when considered together with data from recent excavations elsewhere in upper Mesopotamia, are helping to enhance our chronological and historical understanding of the era. Finally, zooarchaeological and archaeobotanical analyses continue to illuminate the nature of human-animal and human-plant relationships at Kurd Qaburstan in the MB and LB.