Nineteen sixty-one was a signal year for Yugoslavia. In September, Belgrade hosted the Conference of Heads of State or Government of Non-Aligned Countries, reinforcing the country's stature as the European leader of what was then called the Third World. In December, Ivo Andrić became the first, and as it would turn out, only Yugoslav writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. In his speech in Stockholm, the novelist spoke of Yugoslavia as a “‘country between worlds’. . .which, at break-neck speed and at the cost of great sacrifices and prodigious efforts, is trying in all fields, including the field of culture, to make up for those things of which it has been deprived by a singularly turbulent and hostile past.”Footnote 1 Yugoslavia would obtain an admittedly less significant achievement a few months later, in April 1962, when Surogat won the Academy Award for “Short Subjects, Cartoons,” making it the first non-American film to be so honored in the category.Footnote 2

Surogat was the product of a major animation movement, one of the most important of the late twentieth century that had begun a few years before in Zagreb. Since the mid-1950s, animators at Zagreb Film—among them trained architects, comics creators, and fine artists—had produced dozens of shorts, including children's cartoons, gag films, and what can, for lack of better terms, be called more serious, adult fare: experimental films, mini-dramas, political satires, and adaptations of literary classics. By the time of Yugoslavia's dissolution in the early 1990s, two generations of animators had produced hundreds more. At the Cannes Film Festival in 1958, the French critics André Martin and Georges Sadoul gave them their name, the “Zagreb School of Animation”—known in Croatian as zagrebačka škola crtanog filma.Footnote 3

Our love of animated film—whether it be Winsor McCay's Gertie the Dinosaur in 1914 or John Lasseter's Toy Story in 1995—is rooted in both a fascination with technology and a respect for human labor.Footnote 4 Tom Gunning writes that the medium “plays with movement with an affect of wonder and draws attention to its own process,” that it “arouses some curiosity about how it is done, though this does not require a thorough technical understanding,” and that it “restores to the moving image the sense of wonder at movement that the first projections of moving images occasioned.”Footnote 5 There are, of course, many different approaches to the animation medium and many different ways the animated film inspires “wonder.” Paul Wells refers to Disney's mimicry of the real—what we might see in painters’ attempts to give Snow White a more natural look from one frame to the next, or in character designers’ development of Bambi's muscular and skeletal structure based on their careful study of a fawn's carcass—as “hyper-realism.”Footnote 6 Walt Disney sold himself as an entrepreneur as well as a magician, and his hand or more literally the hands of his huge team of workers, were seemingly gifted with a godlike power to create a realistic, but at the same time, more perfected life than what the spectator experienced outside the movie theater.Footnote 7

The films of the Zagreb School, however, appealed to audiences with a different conception of the animator's hand, of “real,” and of “life.” A statement which accompanied screenings of their work at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMa) in New York in 1968 reads as follows:

Animation is an animated film.

A protest against the stationary condition.

Animation transporting movement of nature directly

Cannot be creative animation.

Animation is a technical process in which

the final result must always be creative.

To animate: to give life and soul to a design,

Not through the copying but through the transformation of reality.

The animators reiterate certain assumptions:

Life is warmness.

Warmness is movement.

Movement is life.

Animation is giving life; it means giving warmth.

Animation could be tepid, warm or boiling.

Cold animation is not animation.

It is a stillborn child.

Practically, animation is a long rubbing,

Of tree against tree in order to get sparkle or perhaps just a little smoke.

But they also celebrate their labor and their films’ lack of perfection:

Take one kilo of ideas (not too confused

If possible), 5dkg of talent, 10dkg of hard work

And a few thousand designs.

Shake it all together, and if you are lucky

You will not get the right answer to the question.Footnote 8

The animators employed not the full animation of Disney but so-called “limited” animation, a technique which involves highly simplified graphic design and a reduced number of drawings, resulting in circumscribed movement.Footnote 9 Using techniques born out of limited (but hardly impoverished) economic circumstances, the Zagreb School did not pursue pure mimesis, nor attempt any classic documentary recording of urban or rural life. But their “transformation of reality,” even in films heavily influenced by abstract art and Suprematism, create, paradoxically, a down-to-earth reality, what the Bosnian-born animation historian Midhat Ajan Ajanović describes as “an authentic vision of reality,” one that accepts but does not bemoan the lack of perfection in life.Footnote 10 As such, their vision is neither utopic nor dystopic.

The selfhood of the Zagreb School animators, I argue, is achieved with a techno-modernity. It is the technological process through which animation is produced that provides the tool for the human to reveal an inner being, an essential self. The spectator at MoMa in 1968 may very well have experienced something like “wonder” when they saw a Zagreb School short. Surogat’s clever tricks, rapid transformation of abstract shapes, and use of visual puns excite a childlike fascination. But the spectator's “wonder” was as much rooted in what they saw on the screen, as well as, I also argue, in a particular philosophy of labor.

This reading of the Zagreb School diverges from much scholarship of animation in central and eastern Europe. Western scholars have long attempted to define the political roles animators held in the region's non-democratic, socialist states. More than a few have focused on questions of censorship, romanticizing the animator as a dissident, albeit one working for a state-subsidized entity. Writing less than a decade after the end of the Cold War, William Moritz celebrated films critical of authoritarian regimes in Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Soviet Union. “[T]heir careful planning to outwit censorship made them, in some cases, create masterpieces of film.”Footnote 11 In the years since, scholars have adopted a more nuanced approach. Laura Pontieri, focusing on political satires produced in the Soviet Union in the late 1950s and 1960s, chronicles how artists negotiated the ambiguities of what could and could not be expressed during the Khrushchev Thaw.Footnote 12 The Czech surrealist Jan Švankmajer provides rich fodder for those who believe oppression inspires genius (his career was put on ice in the 1970s), but his politics were complicated, eschewing any obvious alliances. Keith Leslie Johnson writes, “Rather than being keyed to ‘equality’ or ‘justice’ or any of the buzzwords of democracy, Švankmajer's political agenda, such as it is, emerges from perpetual subversion of the order of things by the creative imagination.”Footnote 13 In his study of children's films, David MacFadyen writes that Soviet animation “went about its business in a way that suggests a type of selfhood confounding our expectations of dictatorial cultures.”Footnote 14

The English-language scholarship on the Zagreb School has focused very little on questions of censorship.Footnote 15 This is fitting. Zagreb School animators did not suffer from the belief that their imaginations were stifled by a capricious bureaucracy.Footnote 16 Even though many of the animators would become Party members, as far as their work in animation was concerned, they were not propagandists, obeying top-down directives.Footnote 17 Their films—existential, personal, and abstract—suggest not just autonomy but another form of selfhood. “Selfhood,” however, is not synonymous with “apolitical.” It is in fact their very connection to the larger questions Yugoslavia faced during this rapidly changing period—questions concerning labor, technology, and internationalism—that allowed the Zagreb School animators to realize their identity.

The techno-modern approach in the Zagreb School resonates with its subject matter. While the best-known Czech and Soviet animation indulges national-folk stylizations and contemporary domestic issues, the Zagreb School's major themes are universal: industrialization, militarism, environmentalism, nuclear annihilation, and urban alienation, as well as the conforming pressures of commercialization and mass culture.Footnote 18 Most of the films contain no dialogue whatsoever, emphasizing instead their jazz or classical music soundtracks and ingenious sound effects, in order to accentuate their visual power. A contemporary critic claimed their approach to sound marked them with an “international character.”Footnote 19 The films explore the ambiguities of modernization in the world as a whole, and in this the animators made use of the animation medium to show how societies might come to terms with modernity, for all of its dangers. The animators themselves would not necessarily agree with this interpretation. In a 1962 interview, Vatroslav Mimica, one of the studio's major early auteurs, said that he did not believe there was anything “typically Yugoslav” in the work of the Zagreb School and considered the suggestion that their work was part of a “new international language” an “exaggeration.”Footnote 20 Still, with the benefit of hindsight, almost three decades after the dissolution of the country, and four decades after the end of the Titoist era, the work of the animators, whatever their intentions, seem clearly adjacent to Yugoslavia's vaunted “third way,” an approach to society-building that rejected both the strictures of the communist east and the dehumanization of the capitalist west.

The labor philosophy of the “third way,” a movement which informed the development of the Zagreb School, was essential to Yugoslav identity. In the early 1950s, the country formally adopted a policy known as workers’ self-management, a socialism which would offer autonomy and dignity to the individual worker, all while keeping them part of a collective. Entities would function on the local level, under socialist principles, enjoying state funding, but outside the all-encompassing hand of the central authority in Belgrade. The system encouraged entrepreneurship, as well as a conception of labor driven not by the need for production, but by the need for the individual to maintain dignity while also finding a place within a collective.Footnote 21 The philosophy of workers’ self-management permeated political discourse. In 1968, when Croatians protested the government authority in Belgrade, they did so partly by demanding an adherence to an idea of self-management that would grant more autonomy to workers in Zagreb.Footnote 22 In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Croatian and Serbian intellectuals met annually on the Dalmatian island of Korčula to hammer out the meaning of self-governing socialism.Footnote 23 While this philosophy described the domestic facet of Yugoslav identity, Josip Broz Tito's leadership in the Non-Alignment Movement (NAM) served as the foreign policy rail of Yugoslavism.Footnote 24 As a diplomat on the world stage, he established Yugoslavia as a leader of both the denuclearization and the decolonization movements, a direct rebuke to the two great powers.

This article will examine first the history of how the Zagreb School developed its philosophy towards animation, adjacent to the country's development of workers’ self-management, and how that philosophy was formally, if not obviously, inscribed onto the films of the Zagreb School. Then, as an example of how this labor could be employed towards a conception of Yugoslavia's internationalist project, it will study one particular short, Bumerang, which was released in 1962, the same year the Zagreb School triumphed at the Oscars.Footnote 25 The eleven-minute film, a black comedy about nuclear war well in keeping with Yugoslavia's position regarding disarmament, is not the most representative short of the Zagreb School's early years. The truth is no one film can be seen as representative. I offer this study of Bumerang because it speaks directly to the concerns of the Zagreb School and of Yugoslavia as a whole. Through its employment of limited animation, Bumerang describes a relationship between human and machine that treats modern technology not as a means of creating a new cyborg for a utopian future, but as a means by which an individual human can achieve selfhood. In the Zagreb School, limited animation limits technology's potential to dehumanize the citizen.

The Formation of the Zagreb School of Animation

The story of the Zagreb School in the 1950s is the story of labor and progress in a country that was, following World War II, one of the most under-developed in Europe. Accordingly, the development of cel animation production meant something very different in Yugoslavia in the 1950s than the development of cel animation in the United States, some forty years before. The process employs individual, translucent celluloid sheets, which are used for the drawing of individual characters in various phases of movement. The sheets are then placed against a static, drawn background and photographed. The process, when it was developed by Earl Hurd and John Bray in the 1910s, stream-lined animation production. Following Taylorization practices already dominant in American industry, studios developed an assembly-line approach.Footnote 26 By contrast, the Yugoslav animators who eventually founded the Zagreb School began in the early 1950s not with the intention of developing a more stream-lined method of animation production, but simply with the goal of producing any cel animated film at all.Footnote 27 As Zagreb School animators reinvented the wheel of animation production, they were also searching for their voice, studying North American and European animation, and subconsciously reconfiguring the animator's relationship to labor in and of itself.

The story begins with an entrepreneurial figure, Fadil Hadžić. The publisher of a magazine anthology of comics called Kerempuh, he arranged for several of his comics artists to work on a short, Veliki miting, and assigned the brothers Walter and Norbert Neugebauer, who had experimented with animation a few years before, as directors.Footnote 28Veliki miting is propaganda, produced shortly after Tito's break with Iosif Stalin, and it celebrates Yugoslavia's new position as a state independent of the Soviet-dominated east. Bucharest appears as a dilapidated backwater where a propagandist, working under orders from Moscow, sits in a cluttered office. The Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha appears as a fat frog, Albanians as meek and crippled, and Albania itself as a swamp. Yugoslavia, presented in pristine background art, has a hydroelectric dam and a new highway system. The very existence of Veliki miting, the fact that the film is a work of animation and not live-action, complements the argument of the film. Yugoslavia could produce hydroelectric dams and highway systems. It could also produce animated films which depict the production of hydroelectric dams and highway systems.

Veliki miting is not particularly accomplished, but the do-it-yourself story behind the film's production, chronicled and celebrated at the time and in several retrospective essays and documentaries, is central to its importance. No one in the Neugebauers’ team had training in cel animation, and as a reference they used the Disney animator Preston Blair's handbook, Advanced Animation. It took over a year to make. Hadžić obtained material for individual cels secondhand from film companies. The animators made several rudimentary mistakes.Footnote 29 Still, contemporary reports highlight the film's production as evidence of national self-sufficiency. An article in the Zagreb-based Vjesnik claimed that “our chemists” devised non-running, adhesive paints from horse dung which would be proper for animation cels, paints that were, the paper claimed, superior to what the Yugoslav animators could obtain from outside the country.Footnote 30 Whereas most foreign animated films were between five and ten minutes, an article in the Belgrade-based Borba pointed out that Veliki miting was seventeen minutes—it is actually nineteen minutes—and about 10,000 drawings were made for the film.Footnote 31

In the years following the production of Veliki miting, Yugoslav animators concerned themselves with developing more efficient methods of production and making animated films that would attract audiences both at home and abroad. With the support of the Croatian government, Hadžić and other artists founded Duga Film, naming Walter Neugebauer as president, and obtaining for the new studio's team, among others, the comics creator Dušan Vukotić, who would become the Zagreb School's most famous auteur.Footnote 32 The best known of the shorts produced by the studio was Vukotić’s Začarani dvorac u Dudincima, another film that attempted to mimic the techniques of classical Hollywood animation.Footnote 33 In 1975, the Croatian film theorist Hrvoje Turković noted the film's obvious problems, writing that the protagonists’ movements lack the force of gravity and that the films’ gags are lazy, relying on obvious jokes about bureaucracy.Footnote 34

There were several more attempts to develop and maintain various studios. Vukotić found himself with several other animators in Nikola Kostelac's apartment, where they made commercials for feature films and Yugoslav companies. They contracted with Zagreb Film, a studio that was founded in 1953 with the intention of making live-action feature films, animated films, and documentaries, while also using material and technical equipment from other studios, including Zora Film and Jadran Film.Footnote 35 They started working with limited animation and certain graphic stylizations with which the Zagreb School would eventually become identified. In 1956, they moved permanently to Zagreb Film, which gave up its aspirations for feature films, and there produced what may be the first film of the Zagreb School, Nestašni robot, a science-fiction gag cartoon.Footnote 36 Though unremarkable, Nestašni robot contains many of the stylizations for which the Zagreb School would become known in its early years, particularly the use of abstract shapes in the background. The film was clearly influenced by the United Productions of America (UPA), a studio that had established itself as the vanguard of animation production in the United States with graphic-art masterpieces of limited animation such as Gerald McBoing-Boing and Rooty Toot Toot, as well as a series of cartoons featuring the near-sighted old man Mr. Magoo.Footnote 37

What was Yugoslav animation to be? What were the aspirations of the animators? An article Vukotić wrote in 1957 for the Belgrade-based Knjižene novine summarizes the questions of aesthetics, economics, and politics with which the studio was struggling in this period. The essay is more interesting for the questions Vukotić poses than for any solutions he offers. Many of these problems would remain unresolved throughout the history of the Zagreb School.

Vukotić begins by noting the Disney “technique of bringing speech and movement to perfection.” But he also notes the limits of the Disney style, so reliant on circles and ellipses, and laments Disney's “idealistic middle-class ethics.” He calls for Yugoslav animation to find its own path and says that it cannot do so without effort or funding.Footnote 38 He cautions against making inferior copies of foreign films.Footnote 39 Vukotić also provides a framework for the Zagreb School's aesthetics. Although he and his colleagues were working within the tradition of caricature, he still calls for something akin to realism, by which he means not mimesis, but rather a reflection of the day-to-day life we all inhabit. To interpret his point, we can say that the normal human on the street is not constantly bombarded by beauty nor by ugliness. So how can positive and negative elements be portrayed within the same work of art? “This problem is unsolvable only if the positive is taken to extremes in terms of romantic idealisation which then enters unreality, and if the negative is portrayed only in black and reduced to monstrosities,” he notes. “In turn, what is lost is the essence of humanity, while the characters end up differing to the point of becoming absolutely incompatible with each other in the same surroundings.”Footnote 40 Vukotić points to both Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and the Soviet Disney-esque Zolotaia antilopa as examples of films that had exaggerated the positive as well as the negative—good and evil, we might say—to such extremes they had eschewed anything like realism.Footnote 41 In conclusion, he says, “We are looking to use our humble experience so far to look for solutions and new paths, and will be happy and proud if our first films will succeed in communicating these aspirations of ours.”Footnote 42

In a speech that was later published as an article in the Zagreb-based film magazine Filmska kultura in 1960, Vukotić laid out the fundamental approach he wanted his team to take towards limited animation, calling for films which creatively use between 4,000 and 5,000 drawings—a relatively small number—without diminishing “visual richness.” Through a “meticulous attention to detail and a thorough understanding of animation,” workers would avoid any lazy shortcuts, such as an overuse of cycles, by which the same drawings were used repeatedly.Footnote 43 In other words, Yugoslav animation was also to be a celebration of ingenuity in the face of limited resources. The Zagreb School was not unique in using limited animation. The technique was also employed by Hanna-Barbera in the United States, Soiuzmul΄tfil΄m in the Soviet Union, and Osamu Tezuka in Japan.Footnote 44 But in Zagreb Film, limited animation as well as their organization carried ideological implications.

We can see the development of this philosophy in a behind-the-scenes documentary short Vukotić made for BBC television in 1960, Tisuću jedan crtež.Footnote 45 The film depicts Zagreb Film as an enterprise with no primary intelligence. The workers function individually, but never alone within the collective studio space. Shot by Mihail Ostrovidov, who would become one of Yugoslavia's great cinematographers, they are portrayed as distinct craftsmen. In the opening minutes, Borivoj Dovniković, a future auteur, appears as a character designer struggling to create a protagonist. He finds creative inspiration from an obnoxious woman he had encountered that morning on his commute to work. Miljenko Dörr, shot with a bright light illuminating his face against a black background, playfully voices several sound effects into a microphone. Each figure is lit to accentuate their body and their tool, highlighting their humanity as workers. Although their techniques are no different from what existed in almost any other animation studio at the time, the film suggests the director, or auteur, has only a minor role in the film's production.Footnote 46 In practice, this was often not the case. The Zagreb School, in fact, celebrated its auteurs. Mimica, who could not draw at all, took on a role as an animation auteur analogous to that of a live-action feature-film director.Footnote 47 In other words, the documentary cements the idea of animated film production as a collective project with no hierarchies, an iteration of workers’ self-management, in which each worker realizes their own purpose. The animators work hard to get the “right answer”—Dovniković spends several long minutes trying to draw a good character—but their finished film, while probably good, will not carry the same perfected sheen of a Disney cartoon. Also, it will not portray characters that are either extremely “positive” or “negative.”

Tisu ću jedan crtež ends with a montage of Zagreb School films. As a whole, they lack the finesse and tight narratives of UPA, but they are also far more diverse and employ various styles of the “anti-Disney” movement.Footnote 48 The early films of the Zagreb School include Na livadi, a nightmare of nuclear war; Happy-End, a Dalí-esque vision of the apocalypse; Piccolo, a film about the failures of peaceful co-existence that sets exuberant classical music and jazz melodies against vibrant purples and greens; and Zbog jednog tanjura, a satire of consumerism in which the geometric bodies of characters pun on the consumer objects they enjoy.Footnote 49 The Balzac adaptation Sagren ška koža mixes various art schools and indulges beautiful Art Deco stylizations.Footnote 50 Vlado Kristl's difficult, abstract, and comedic Don Kihot evaluates and re-evaluates geometry and perception.Footnote 51 Color schemes differ from one film to the next, as does movement. In the opening minutes of Zbog jednog tanjura, for instance, a husband jumps from one extreme position to another in the opening minutes. The more fluid movements of military machinery in Na livadi recall in style (if not message) some of Disney's World War II propaganda. The bleak Happy-End focuses the viewer's attention not on its protagonist but on the mise-en-scène of Zlatko Bourek's backgrounds. The themes are not consistent. Some shorts are straight gag films. Some study greater societal issues. Others are existentialist exercises. Many films defy clear genre categories. “People talk about the ‘Zagreb School,’ but I just came back from Yugoslavia, and I know they're going off in all directions,” Chuck Jones said in 1969.Footnote 52

Did the Zagreb School suggest a national identity? The auteur Aleksandar Marks claimed that if a “Yugoslav style” could exist it could not be forced.Footnote 53 “Our animated films still lack a more distinctive feature we could call our own. However, let us not consider this to be a serious flaw. . .,” Vukotić said in his 1960 speech.Footnote 54 Boris Kolar, the director of Bumerang, attempted to define the connection between the Zagreb School's oeuvre and Yugoslav identity, claiming that the Zagreb School could speak to the condition of man and society from “our aspect,” and that it could contribute both to “socialist culture” and animation.Footnote 55 Kolar called the Zagreb School a collective of virtuosic, self-taught artists, “among the best-known ambassadors of our culture and art.” He explored the reasons why the Zagreb School focused so much on universal themes, noting that the films about nuclear war and the failures of peaceful coexistence (Na livadi, Piccolo, and Bumerang) reflect Yugoslav foreign policy. That the artists from a country that had yet to experience all of modern technology's benefits, let alone its drawbacks, would spend their energies criticizing modern technology was for him a paradox.Footnote 56 But the struggle with modernity is essential to Yugoslav identity, and permeated discussions at the highest levels of government.

Mimica, despite his claims to the contrary, did make a film that speaks directly, didactically, to the Yugoslav character, in particular the ideals of workers’ self-management, and to the uses of technology. In Perpetuo i mobile, ltd., a film originally meant as an art installation, a worker struggles, Charlie Chaplin-like, on an assembly line, finding himself sucked into a machine, and at one point turned into a screw.Footnote 57 The film ends with the slogan: “We solve this problem with the participation of the worker in the management economy.” The film's message, as expressed visually, bears a striking resemblance to the arguments of Dziga Vertov, whose utopic vision Chelovek s kino-apparatom employs photographic collages and what we now call live-action, stop-motion animation to invent a novyi chelovek, a “new man” fully imbricated with modern technology.Footnote 58 Cinema that examines the “psychological,” Vertov wrote in 1922, “prevents man from being as precise as a stopwatch; it interferes with his desire for kinship with the machine.”Footnote 59 For Mimica, however, the machine works for the worker only if the worker himself is able to assert his humanity. Such beliefs seem to have permeated his ideas of animation. In one essay, he looked to filmmakers as disparate as Sergei Eisenstein and Saul Bass, who created a “new wave of romanticism.” Thinking globally in the era after Mauthausen and Hiroshima, he rejected any film that attempted a classical narrative. Instead, he called for a purified “SYMPHONY OF DRAWING AND MOVEMENT.”Footnote 60

Kolar's humbler approach, however, speaks to what became a through-line in the Zagreb School and its uses and approaches to the technological process of animation. The Zagreb School's artistic but relatively unpretentious approach to filmmaking acknowledges the technological process of animation as a means by which its heroes can declare themselves, not as heroes or villains, but as common men and women. Within a few years, after the end of the first phase of the Zagreb School, animators would employ an archetype known as the mali čovjek, the “small man,” a put-upon anti-hero, who faces the brutal problems of modern life. Three decades after Vertov wrote his manifesto, the Zagreb School was developing an approach to modernism that put breaks on the machine and made it a servant to man's natural state.

Unlike the animated shorts in Mimica's oeuvre, Kolar's Bumerang is a crowd-pleaser. It is just as aware of the post-Hiroshima/post-Mauthausen world Mimica describes in Happy-End, but it employs clever gags in order to examine the industrialization of modern warfare and the threat of nuclearization. The protagonist in the film is a mean-spirited general, but he lacks the grandeur of a Disney villain. The human soldiers he bullies lack any particularly heroic qualities. The film, as a whole, is not a symphony of drawing and movement as much as a cacophonous evening band's rendition of the same. To follow Gunning's definition of the animation medium, noted in this article's introduction, Bumerang plays with wonder and draws attention to its process, arouses curiosity about how it is done, and restores to the moving image the sense of wonder toward movement that the first projections of moving images occasioned. The viewer wonders at and admires not an illusion of life, however. Instead, they are enchanted by the clever reinvention of the medium and admire, whether they realize it or not, the socialist philosophy that helped make that reinvention possible.

Nuclear War and Satire

A summary of Bumerang’s narrative reveals its fundamental theme, juxtaposing the existence of advanced technology, with all of its attendant threats, with more primitive, folk technology, the kind that had been developed in rural environments throughout the nineteenth century. The film opens with a butterfly navigating an idyllic field of flowers. A machine, part bulldozer, tank, and man—a kind of cyborg—bulldozes the area. Afterwards, the cyborg plants, like a farm tractor with a plow, a series of mini-missiles that grow into hydrogen bombs. A new base of nuclear warheads has been established.

A general studies each bomb, testing them individually not with a machine, but by banging a hammer on each weapon to test for whether or not it makes a hollow sound. When one does make such a sound, he climbs the missile, opens the top and replaces a small-case “h” with a capital “H.” The general organizes his soldiers and forces them into a series of ridiculous formations. He denies their individuality. When one soldier steps out of line, he opens his helmet and removes a flower, a pretty bird, and a musical note, replacing it with a bullet. The formations are disrupted again when the butterfly reappears and distracts the general. As he swats it away, his soldiers follow his movements again, falling apart in disorder. The general attempts to kill the butterfly with a gun. He demands that his soldiers build a series of weapons, but they keep failing to follow his orders, building instead a collection of farm implements.

After a long, frustrating day, the general relaxes in front of a surveillance screen, which he treats like a television, eventually hitting on a stripper show. When his subordinate sees a bomb on a separate screen, he tries frantically to warn his general, by changing the channel, even ringing a small hollow-cup bell, but is ignored.

The general realizes his mistake and panics. He orders the mass mobilization not only of his own soldiers but of society as a whole: beachgoers, lovers on a park bench, soccer players, a cop and a robber, a corpse at a funeral, and newborn babies. The subordinate's mistake is revealed at the last, crucial moment. The bomb on the radar screen is not actually a bomb, but rather the silhouette of the butterfly, who has landed on the radar detector. The general saves the day by using a wheel and hand crank on his radar screen to turn the missiles away from their target.

Everything returns to normal. The helmets that had appeared on the mass citizenry, turning each of them into soldiers, magically lift from their heads, and return to a square black box. Fade to black. In the film's coda, a bird in search of a worm that has crawled on the radar zooms in for a kill. The subordinate sees the silhouette of the bird on the screen, and panic returns. Most Zagreb School films end with one of two Croatian words for “The End,” kraj or svršetak. Bumerang ends with a question mark.

At first glance, Bumerang is one of many examples in world cinema that expresses a viewpoint shared by several political philosophies: human beings are inherently incapable of responsibly handling the awesome power of nuclear weaponry. There is nothing uniquely Yugoslav about the film's sense of humor. Bumerang tells many of the same jokes as those found in Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, which was released a short two years later, in 1964.Footnote 61 Like Dr. Strangelove, Bumerang associates the male libido with nuclear power. Both films work with the aesthetics of aerial vision and draw upon the phallic associations of the hydrogen bomb.

But there is an inherently Yugoslav notion that permeates Bumerang. The film was released the same year as the Cuban Missile Crisis, during which Tito's government maintained a position well in keeping with the ideals of the Third Way, one that not only respected the ideals of denuclearization but also decolonization.Footnote 62 The narrative of Bumerang suggests a nation-state gone awry, one that disrupts man's natural desire to chase after butterflies, enjoy individual autonomy, and not live under the tyranny of nuclearized states.Footnote 63

In its depiction of a military that dehumanizes its soldiers, the Zagreb School animators inscribed an idea of humanity onto the film by revealing themselves. The viewer senses the movement of the hand drawing the shapes and laying out the backgrounds. They sense the means by which laborers, working within their modest means, communicate the dangers of nuclear power. Dr. Strangelove surrenders to the visual pleasures offered by aerial vision and offers a way out of the nightmare of nuclear war through hilarity. Pauline Kael would write that Dr. Strangelove “was experienced not as satire but as a confirmation of fears. Total laughter carried the day. A new generation enjoyed seeing the world as insane; they literally learned to stop worrying and love the bomb.”Footnote 64 Total laughter carries the day in Bumerang as well, but so does the power of labor, of the designers who shape and build each character, of the key animators and in-betweeners who articulate the movement, and of the background artist and designer's reconsideration of perspective.

Character Design

Limited animation did not outright reject the curvilinear line, a means by which animated characters had been permitted the ability to move, stretch and squash, morph and re-morph, while always tied or anchored to a centerline. Graphic designers and practitioners of limited animation often preferred sharper angles and quadrilaterals, however.Footnote 65 The film critic and Zagreb School fellow traveler Ranko Munitić, in his analysis of Vukotić’s films, noted the influence of Piet Mondrian. Bodies are defined by line. They lack three-dimensional volume. They are placed against an infinite space surrounded by other flat geometrical shapes.Footnote 66 Zagreb School animators imbue geometrical objects with specific, concrete meanings. In the case of Bumerang, the stiff black rectangles and severe line drawings suggest the military's inhumanity.

The general is the star of Bumerang and the first character who appears in the film, standing in a fixed, frozen position before the opening credits. He holds the shape of a nuclear missile in one hand (Figure 1). His stomach/torso is made up of a thick block rectangle articulated with thick black lines and within mini-circles and triangles suggesting a collection of medals. His four limbs are thin, just shy of spidery. His military hat complements his sharp triangular nose and his large thin smile is self-satisfied. After he throws the missile, his head cranks down. His eye has opened, and the black of his eyeball meshes into his black military cap. He is introduced to us as a mischievous, malevolent child. More importantly, his organic body and his military uniform are one and the same. He cannot exist as a naked being: he is himself defined by the cruel rules of geometry.

Figure 1. Bumerang (Boomerang, Boris Kolar 1962)

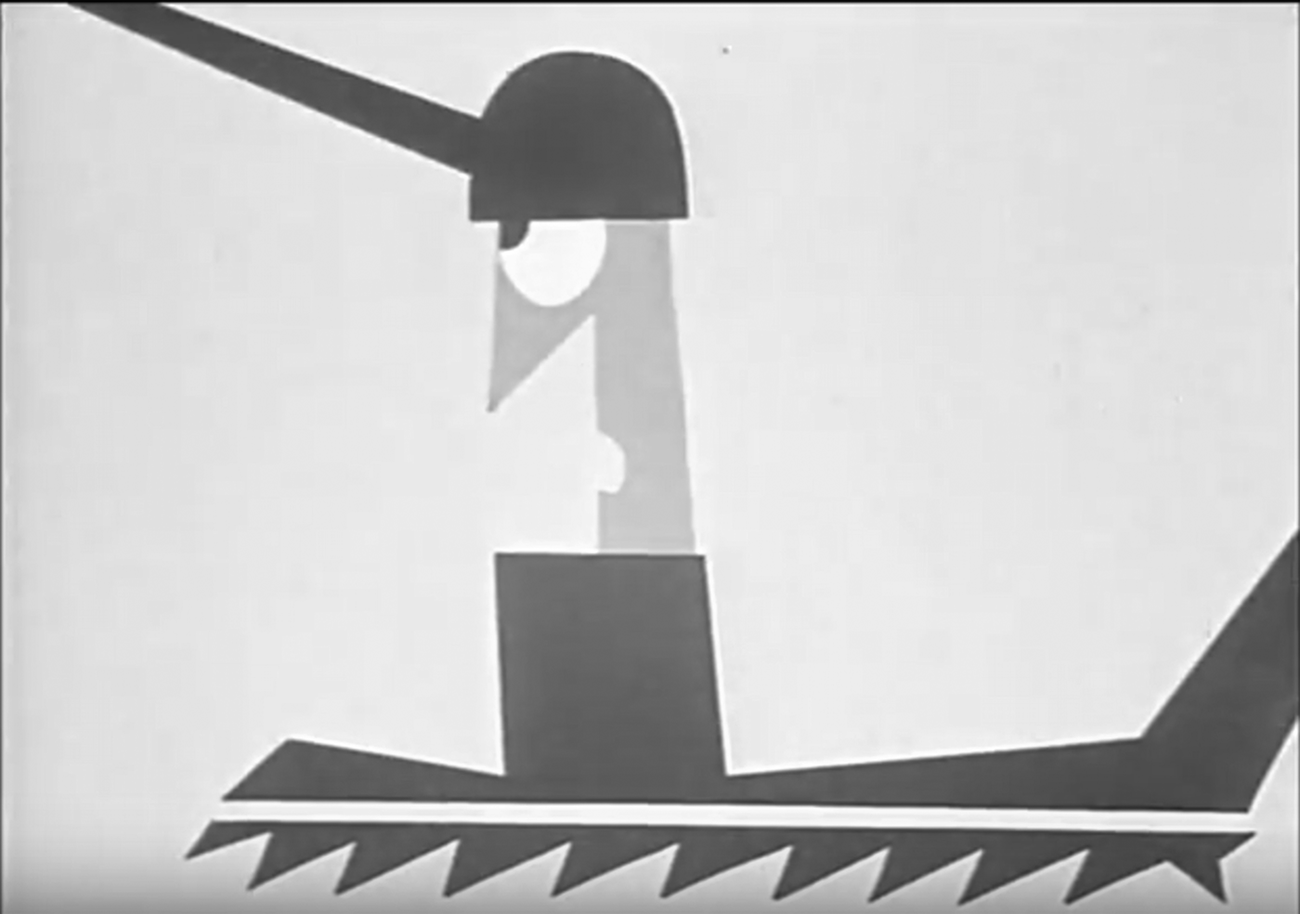

We can find the same approach in the design of the cyborg-like tank/bulldozer/man (Figure 2). The human head, which appears for only a few short seconds, emerges out of the body of the machine. The tank head and the barrel follow the same pattern if not exactly the same design as the general's hat. A half circle articulates the top, describing a helmet. The thick cylinder suggests the barrel is an insect-like antenna. It is not clear whether the face conforms to the machine or the machine conforms to the man. We can imagine Kolar or a member of his team, drawing with a sharp pen, perhaps even a ruler, each sharp line, running along a sharp edge. When we pause on the frame, we see that the triangles of the bottom meant to articulate a bulldozer's violent wheels, are not uniform. They differ slightly in size. A human hand has aggressively made these cuts into the body of this cyborg, although it seems to have done so quickly, hitting an angry note or two. It may be a machine, but it is an imperfect one.

Figure 2. Bumerang (Boomerang, Boris Kolar 1962)

Movement

The use of fewer drawings has various implications in limited animation. Bodies may appear more stilted. The viewer is forced to use their imagination to think in greater detail about what exists between key frames. At its most extreme, limited animation employs what we might think of as the animation medium's equivalent of a jump cut. Characters and objects effectively jump from one key position to another, from one frame to the next, occupying several frames of stillness before jumping once again. Several works of the Zagreb School employ the jump cut or something analogous to it. In the opening scene of Zbog jednog tanjura, a husband, made up of stiff geometrical shapes, jumps from one position to another to the rhythm of a scat jazz score. His body's movements, as well as the shapes of the objects he purchases, are motivated by the excitement of urban modernity and consumer culture. In the ultra-violent Koncert za mašinsku pušku, the jump cut is used to describe violence and death.Footnote 67 A body first appears whole and then, after a gunshot, is in the next frame broken apart on the screen, red paint expressive of blood and blue paint expressive of entrails. The bodies will not return to their original state. Their deaths are final.

Most of the movements in Bumerang are not jump cuts. Cycles are used throughout the film to express mechanical, robotic qualities. Bodies march stiffly. The lack of fluidity is the point. These cycles are not the result of lazy shortcuts on the part of the animators—what Vukotić had warned against a few years before—but rather a means of expressing the laziness of thought within the characters themselves. The humanity of the general and of the other members of the military appears once the cycles are broken, always announced with a jump cut. The general's sexual excitement when he sees the striptease artist is articulated with swift and extreme movements. His realization of his folly is expressed through another jump cut reflecting panic, as is the urgency with which he stops what at first seems like inevitable self-destruction.

Perspective

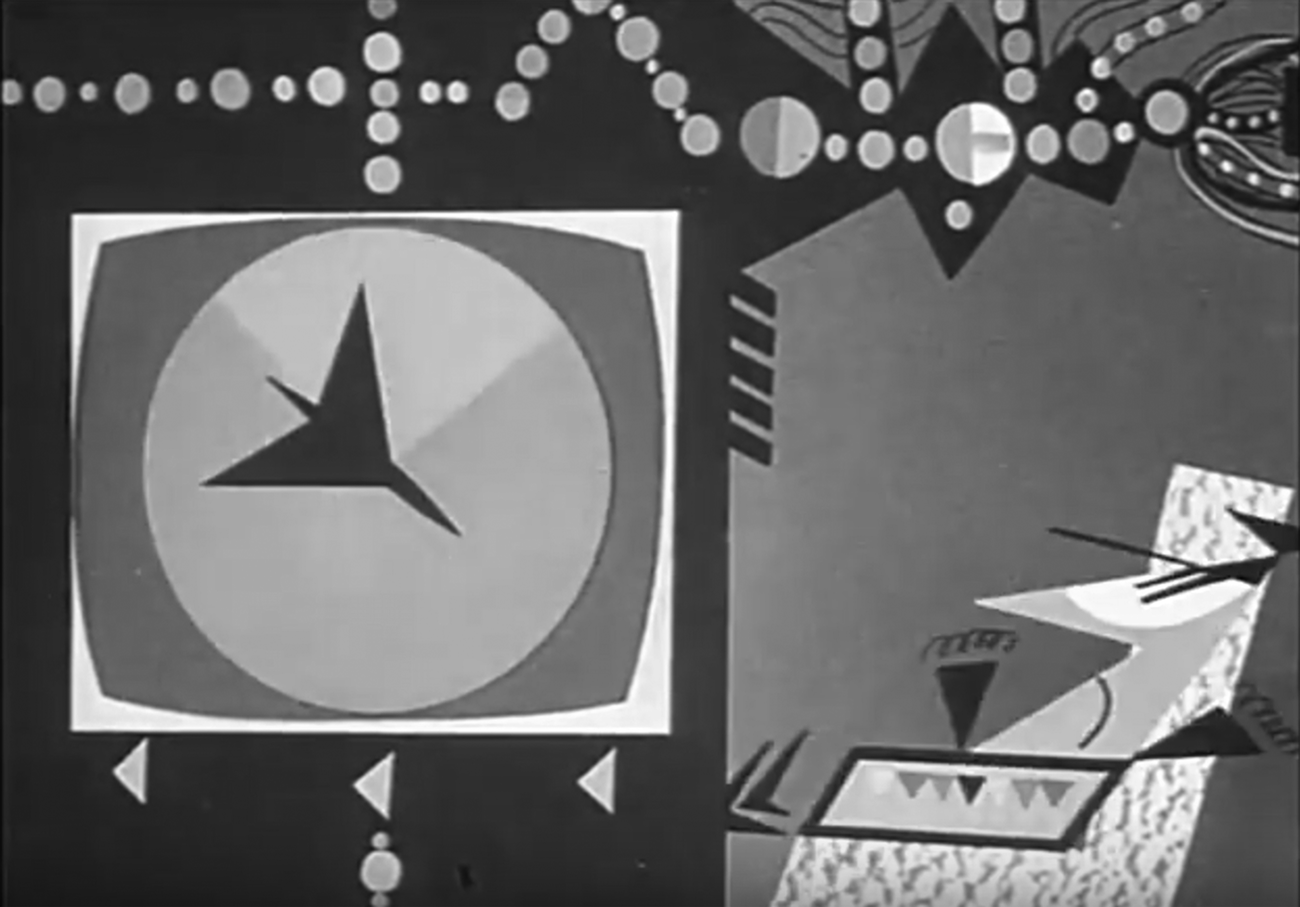

The term “flat graphic,” although used to describe much abstract animation in the post-World War II era, is often a misnomer. The term suggests animation in which the two-dimensional is an absolute, at the expense of any depth cues that would suggest three-dimensional space. Such depth cues—differences in size, a use of linear perspective, attached and detached shadows—are conventions in classical Hollywood animation, but a study of the backgrounds in UPA and Zagreb School cartoons would suggest otherwise. Still, Surogat follows the idea of what one can define as flat graphic. The objects are placed flat against the screen. The representations of bodies, goods, and shapes do not delineate any clear spatial relations between the characters.

I will not focus on each element of perspective in Bumerang. Many scenes follow the standard assumptions of flat graphics and contain absolutely no depth cues. Characters are presented as symbols in the manner of an early video game. I will, however, focus on Bumerang’s sense of depth and perspective in its depiction of aerial vision. Bumerang uses extreme flatness in its adoption and subversion of the conventions of the aerial shot, as we recognize it from photography, live-action film, and topographical drawing.

In the first moment of the film, following the opening credits, the viewer sees a large canvas of white and splotches of various colors (Figure 3). It is not clear what this background represents—the image is too abstract—until, after a zoom in, the film dissolves to a close-up of a butterfly travelling happily among these blotches. It is a field of flowers. The background artist Zlatko Bourek's watercolors are pretty, and carry something akin to a folk-art stylization. The butterfly settles on a flower. The shot dissolves back to the aerial shot of the entire field, now no longer an abstract collection of colors but a clear representation of a natural setting. The butterfly is a small part of the field. Its presence now defines the meaning of the objects around it. All is complete stillness.

Figure 3. Bumerang (Boomerang, Boris Kolar 1962)

A new, strange machine, one that is part tank and part bulldozer, appears and destroys the field, square by square. We see the field from a direct angle overhead, a top-down aerial shot. The view of the butterfly determines this angle, but the representation of the machine upsets the perspectival system (Figure 4). On the one hand, it is drawn as it would be seen from a direct ground level. On the other, it is a representation of the machine itself in an architectural drawing. It bulldozes most of the field, one piece of rectangular space at a time, following again the logic of pure, cold geometry. The butterfly flies away, its size increasing and decreasing as a suggestion of its distance from the viewer's eye, thus maintaining standard depth cues and maintaining the original conception of the shot as an aerial view.

Figure 4. Bumerang (Boomerang, Boris Kolar 1962)

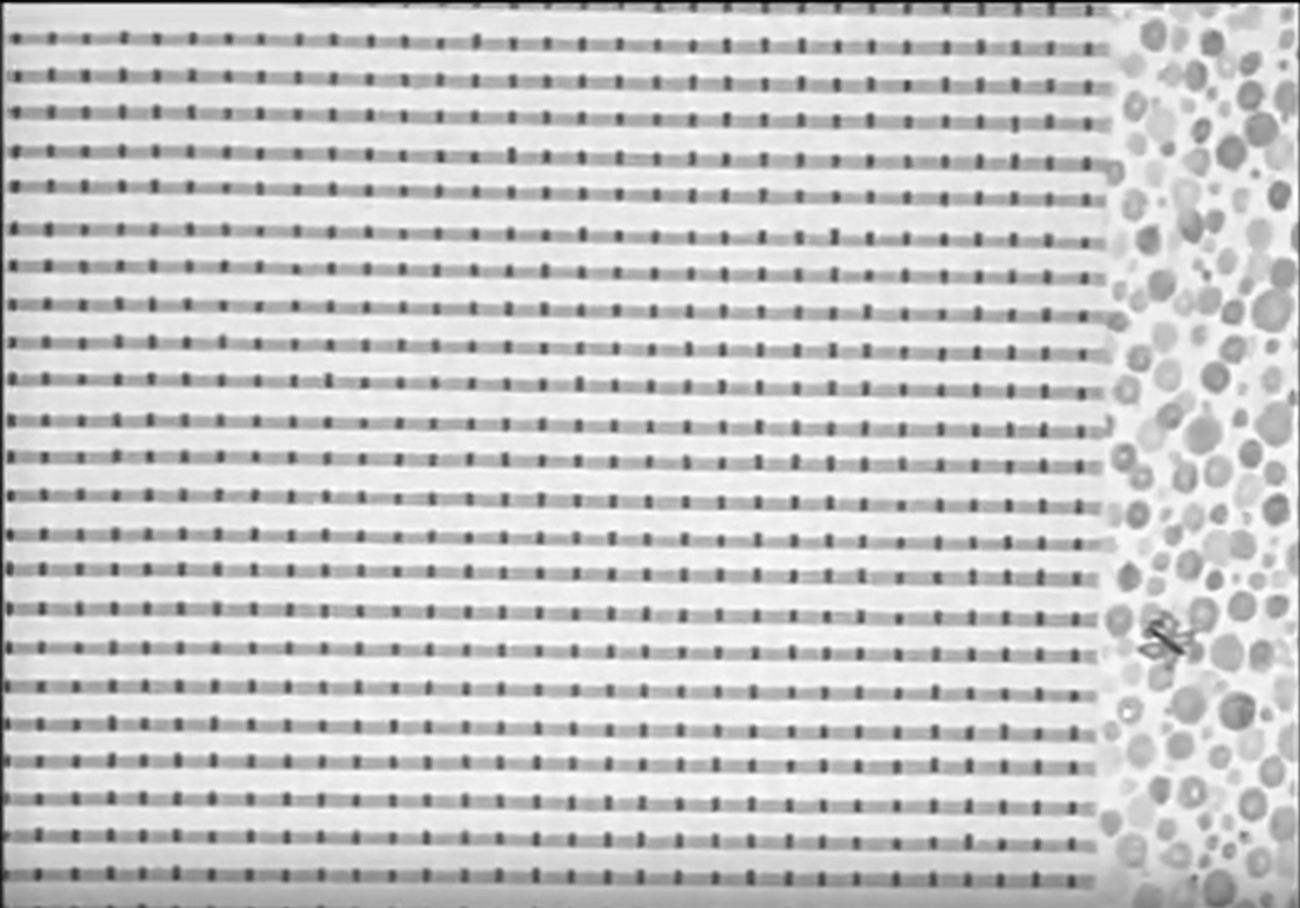

The film cuts to a close up of the cyborg. A head emerges from the tank and then disappears back into the machine. The cyborg returns to plow the field. It is no longer presented at ground-level, but at a slight angle, to suggest if not depth than the idea of depth. The machine plants a series of bullets, presented again from the side-angle view, all of them the exact same size (Figure 5). The butterfly studies the bullets, tries to pollinate them. They rapidly grow into a series of missiles. In other words, the pure aerial conception of this space is connected with a joyful celebration of the natural. The presence of the cyborg turns the space into something artificial, outside a comforting, realistic vision of space.

Figure 5. Bumerang (Boomerang, Boris Kolar 1962)

The direct opposite of this aerial vision of the field, as presented in the opening of the film, is the image of the “boomerang” of the film's title as it appears on the radar screen, an image that serves as the point upon which the narrative turns. The image of the boomerang, articulated to appear as a silhouette of a missile, appears flat and pure: the image of what a warhead would look like via a radar-eye pointed directly above into the sky (Figure 6). Like the butterfly in the aerial shot of the field, it increases and decreases in size to suggest its spatial relation to this radar eye within the film. In the film's essential gag, we discover that this “boomerang” on the screen is not a missile, but rather the butterfly from the film's first act, whose flight up and down is innocent and gentle when viewed from above, but is threatening and deadly when viewed from below, mediated through a machine.

Figure 6. Bumerang (Boomerang, Boris Kolar 1962)

In an analysis of the discourse of aerial vision in the twentieth century, Paula Amad has noted a dominant dystopian reading, particularly from Walter Benjamin and Paul Virilio, which connects the eye of the human held above the earth, high into the sky, with the bombing campaigns of World War I and World War II. “[T]here is obviously significant material evidence for the association of aerial vision with the negative, violent and even terroristic mode of modern vision.”Footnote 68 A utopian reading, one that relates the new opportunities offered by the aerial image in the pre-World War I era, from the Wright Brothers’ flight to 1914, suggests “the emancipation of the body and representation from the gravitational pull of the earth and traditional perspectival art.”Footnote 69 Amad upsets the binary by pointing to another discourse in which aerial vision offers a new conception of the earth, one in which humans are decentered and mountains and other natural phenomena can be considered living organisms. This conception became essential to the discourse of eco-environmentalism.Footnote 70

Bumerang’s conception of aerial vision and ground-up vision upsets the binary as well. The aerial vision of the short's first act is the privilege of the viewer, not of anyone within the film's diegesis, and even the viewer needs the presence of the butterfly to explain to them exactly what they are looking at. It does not fit into the utopian category that Amad describes as much as the middle way conception in which aerial vision is a means of explaining and conceiving the natural world, and an earth in which humans and human invention are no longer granted primacy. The Zagreb School's flat graphic vision has emancipated the viewer from perfection.

In its very essence, the development and struggle with technology is fundamental to Yugoslavia in the 1950s and 60s, and the Zagreb School, as Kolar imagines it, speaks directly to these concerns. The Zagreb School, by using limited animation to describe the great modern crises on the global stage, permits individuals to reveal themselves and their personalities. Their work comments on technology and community, on issues that inform how Yugoslavia wished to be perceived on the world stage, and how it wished to position itself as a moral critic of the great powers in the middle stages of the Cold War. They share in the global movement to break Disney ideology and rebuild the animation medium, and by doing so rebuild the world as a whole.

The viewers of the Zagreb School, at film festivals, on college campuses, and in museums, did not perversely fall in love with the bomb, nor factory life, nor rapid urbanization, nor technological alienation. They fell in love with an approach to modernism that called into question problems with modernity. They also fell in love with a new form of craftsmanship and a new means of witnessing the hand of the animator. They fell in love with a philosophy of labor, one that favored both a degree of entrepreneurship and autonomy, associated with capitalist systems, as well as a concept of labor as a means of realizing human dignity, associated with socialist systems. In order to save mankind from the threat of annihilation, either via nuclear war or environmental degradation, rapid urbanization or political upheaval, it was necessary to find a new means and a new reason for living and working in the modern era. The Zagreb School, whether its workers realized it or not, attempted to do so by rethinking the very meaning of the animated laborer and the animated film.