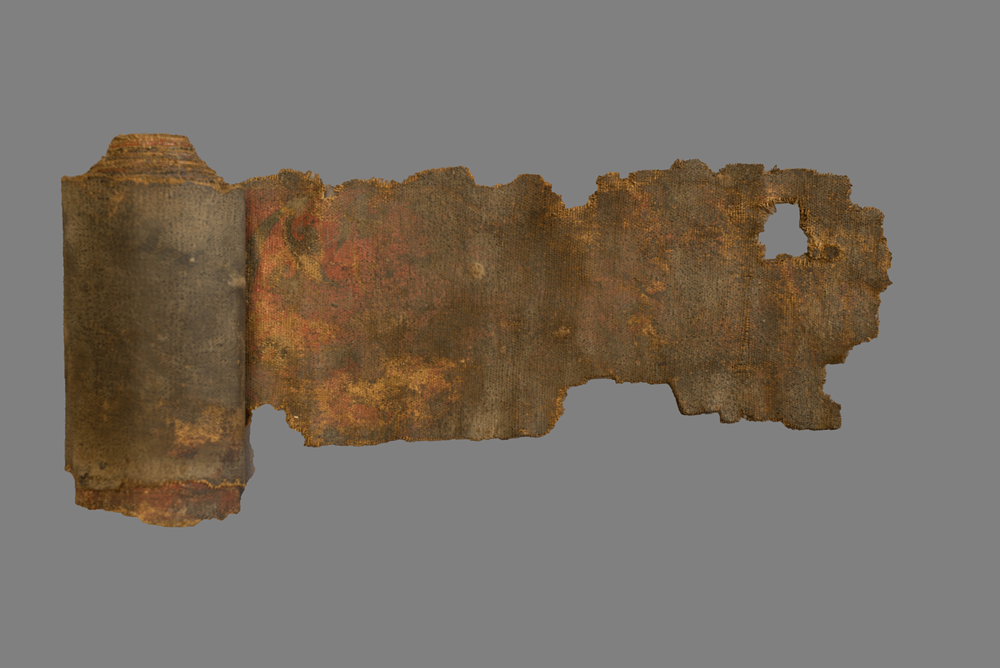

Among the numerous precious items—statues, paintings, ritual objects, and manuscripts—preserved for centuries by the monks of the Namgyal Choede Monastery (rnam rgyal chos sde), near Lo Manthang, in Mustang, Nepal, there are two intriguing painted scrolls (Fig. 1).Footnote 1 This article investigates the context, content and style of these scrolls, which are painted on both sides. The front side of one of them—referred to as the “Offerings Scroll”—is painted with offering deities and symbols within a continuous vegetal scroll (Fig. 2). The other scroll—referred to as the “Charnel Ground Scroll”—depicts the eight great charnel grounds (aṣṭaśmaśāna, dur khrod brgyad) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1. Footnote ‡

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Namgyal Choede Monastery dates prior to the first visit of the renowned Tibetan teacher Ngorchen Kunga Zangpo (ngor chen kun dga’ bzang po, 1382–1456) to Mustang in 1427.Footnote 2 This visit marked the beginning of a period of religious flourishing in the region initiated by the efforts of the sagacious King Amapel (a ma dpal, 1388–1447). During Ngorchen's second visit to Mustang in 1436 the Namgyal monastic complex was restored and expanded.Footnote 3 According to the sources, the reconstruction of Ngorchen was carried out combining three monasteries into one,Footnote 4 but in Roberto Vitalis's view Ngorchen simply invited the monks of these three monasteries to join the renewed Namgyal Choede.Footnote 5 When Ngorchen visited Mustang a third time between 1447–49, one thousand monks were living at Namgyal Choede.Footnote 6 The Namgyal collection may well be the result of the union of the three monasteries, but it has its roots in the period preceding the visit of Ngorchen.

The Offerings Scroll in its present condition is 675 cm long and 17 cm high; it is damaged at the end. It is made up of thick canvas treated to maintain the elasticity necessary to be rolled up. The structure and composition of the painting is extremely regular, as the entire canvas is covered by a long lotus scroll framing figures and symbols (Fig. 2). As Christian Luczanits pointed out in a conversation, the junctures of the four canvas segments that make up the scroll are clearly visible. Each of the segments is decorated with eleven images; thus, the scroll originally bore forty-four such images. On the last segment ten of these can be recognised; thus, only one—measuring approximately 15.5 cm—is missing. This means that the Offerings Scroll originally was ca. 690 cm long.

The Charnel Ground Scroll is a canvas of 703 cm in length and 20 cm in height, but a considerable part of it is missing. The original length can be reconstructed by extrapolating from the length of each of the fully preserved charnel grounds. According to my measurements, each Charnel Ground is 105 cm in length, so the full length of the scroll was approximately 840 cm.

The backs of both scrolls are painted with flames above a chain of vajra (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). Clearly, then, these paintings relate to and were used for a mandala, representing its outer periphery. The fact that the scrolls are painted on both sides indicates that they were used in a standing position that allowed them to be seen from both sides.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Given the dimensions of the scrolls, the mandalas for which the Namgyal scrolls were used had a diameter of at least 2.5 metres—truly impressive mandalas.Footnote 7 According to one of Namgyal's oldest monks, the two scrolls were used during the consecration of the sacred space (rab gnas) before, that is, the actual making of a sand mandala. The monks also told me that there had been four such scrolls in the monastery, but only two remain.

There are few other objects that compare with the Namgyal scrolls, namely:

• a nineteenth-century Offerings Scroll attributed to Tibet,Footnote 8

• a scroll attributable to the fourteenth-fifteenth century (Fig. 6), photographed by Eric Valli in Dolpo during one of his travels in the 1990s,Footnote 9 and

Fig. 6.

• a nineteenth-century example with the eight Charnel Grounds, today in the Shelley and Donald Rubin collection.Footnote 10

Of these scrolls, the first two represent offerings goddesses and are painted on both sides with flames and a chain of vajra on the backs. It is unclear whether the example in the Rubin collection is also painted on both sides.

In terms of iconography, we can compare the content of the scrolls with an altar table displaying a Vajrayoginī, today in the Alsdorf Collection and attributed to the eighteenth-nineteenth century.Footnote 11 In the upper part of the altar is the Vajrayoginī mandala surrounded by the eight charnel grounds. Four of the seven symbols of a universal ruler (cakravartin) are painted in the four corners of the table's surface, while on the sides of the altar the sixteen offering goddesses appear against a red background. Below the goddesses are the eight auspicious symbols.

In terms of format, the scrolls can be compared to the long painted scrolls depicting narratives as used in the Kathmandu valley. There are numerous examples of this type,Footnote 12 in their structure and composition resembling the Namgyal scrolls but obviously with completely different contents.

Having established the general context for the scrolls, we will now take a closer look at each of the two scrolls and analyse their content and style.

Offerings Scroll

There are six groups of figures and symbols represented on this scroll, which can be identified as: Eight Offering Goddesses, Sixteen Vajra Goddesses, Eight Auspicious Symbols, Seven Emblems of a Universal Ruler, Five Offerings for Sensory Enjoyment. Of these, the Eight Auspicious Symbols are divided into four sets of two symbols each, which are used to separate the figures and symbols of the other groups.

Read from left to right, at the beginning of the scroll are eight goddesses of offerings (mchod pa'i lha mo) which ritually symbolise the invitation of the deity to the sacred space: the green goddess Arghyā (mchod yon ma) with water to symbolically welcome a guest, the green Pādyā (zhabs bsil ma) with water to refresh the feet, the white Puṣpā (me tog ma) with a garland of flowers, the yellow Dhūpā (bdug spos ma) with incense (Fig. 7), the red Ālokā (mar me ma) with the lamp, the light green Gāndhā (dri chab ma) with the conch containing fragrance, the red Naivedyā (zhal zas ma) with a torma symbolising the offering of food, and the green ŚaptaFootnote 13 (sgra ma) with cymbals.Footnote 14

Fig. 7.

Between the seventh and eighth of these goddesses are the first two of the Eight Auspicious Symbols (aṣṭamaṅgala, bkra shis rtags brgyad), namely the knot and the flaming wheel (Fig. 8). As we have seen, these auspicious symbols divide the composition of the scroll into four parts.

Fig. 8.

The following group consists of Sixteen Offering Goddesses (mchod pa'i lha mo bcu drug), also called Sixteen Vajra Goddesses with their offerings and musical instruments.Footnote 15 They begin with the offerings of music, each of the goddesses holding and named after their respective instruments: the blue lute goddess Vīṇā (pi wang ma) (Fig. 9), the yellow flute goddess Vaṃsa (gling bu ma) (Fig. 10), the red drum goddess Mṛdaṅga (rnga zlum ma) (Fig. 11); and the green clay drum goddess Murajā (rdza rnga ma) (Fig. 11).Footnote 16 These are followed by offerings of joyful song and dance: the white goddess of charm Lāsyā (sgeg ma) (Fig. 12), the red goddess of song Gītā (glu ma) (Fig. 13), the yellowFootnote 17 goddess of laughter Hāsyā, sometimes also known as goddess of garlands, (phreng ba ma) (Fig. 13), and the green goddess of dance Nṛtyā (gar ma) (Fig. 14).

Fig. 9.

Fig. 10.

Fig. 11.

Fig. 12.

Fig. 13.

Fig. 14.

Two more auspicious symbols, the lotus (Fig. 14) and the victory banner are placed between the last two goddesses, the yellow Hāsyā (Fig. 13) and the green Nṛtyā (Fig. 14).

The third group among the sixteen offering goddesses present precious substances: the white goddess of flowers, Pūṣpā (me tog ma) (Fig. 15), the blueFootnote 18 goddess of incense, Dhupā (bdug spos ma) (Fig. 16), the red goddess of Light, Dīpā (mar me ma) or the Lamp Goddess (Fig. 17), and the green goddess of perfume, Gandhā (dri chab ma) (Fig. 17).

Fig. 15.

Fig. 16.

Fig. 17.

Finally there are five goddesses making offerings to the five senses: the yellow/orange (but in other versions white) goddess of form, Rūpa or the Mirror Goddess (me long ma) (Fig. 18), the red goddess of taste, Rasā (ro ma) (Fig. 18), the green (but sometimes white) goddess of touch, Sparśā (reg bya ma) (Figure 19), and the white goddess of the dharmadhātu, Dharmā (chos kyi ying ma) (Fig. 20).

Fig. 18.

Fig. 19.

Fig. 20.

The description of this Sixteenth Goddesses appears in Abhayākaragupta'sFootnote 19 Niṣpannayogāvalī.Footnote 20 These deities with offerings, with some colour variations vis-à-vis our scroll, are also described in the 'byung po'i gtor chog phrin las rgyas byed Footnote 21 related to the Food Offerings to the Spirits during rituals as mentioned in the Hevajra Tantra, part of the complete works of Ngorchen Kunga Zangpo, the ngor chen kun dga' bzang po'i bka' 'bum. Footnote 22

These GoddessesFootnote 23 are represented in a fourteenth-century thangka dedicated to Cakrasaṃvara Maṇḍala belonging to the Pritzker Collection (Fig. 21).Footnote 24 At the bottom of this painting is the group of Goddesses in their manifestations with four arms. They correspond to the group in the Scroll of the Offerings but sometimes with inversion of colours as well as and not just a greater number of arms. In the Cakrasaṃvara thangka the order starts from the centre towards the right and left, in conformity with one of the typical arrangements of the figures according to rank in the thangkas’ composition.

Fig. 21.

In general, the differences—more or less consistent—the various versions of the sixteen deities that we can see in different representations may depend on the cycle to which they belong or the lineage of teachings in which they are described, but the symbolism of the group does not change.

The Sixteen Goddesses are also depicted in another mandala thangka dedicated to Samvara, now conserved in the Boston Museum of Fine ArtsFootnote 25 (Fig. 22). Here the deities are divided into two rows: below we see ten deities and, in the upper row, the other six, divided into two groups, one on the right, the other on the left.

Fig. 22.

Another, similar example of the Sixteen Goddesses, arranged in the same way as the Pritzker thangka, is visible on one of the fourteenth-century three-dimensional stupas of Densatil (gdam sa mthil).Footnote 26 The fifth tier of one of those stupas presents the same groups of Offering Goddesses, in the same order as the Cakrasaṃvara Thangka.Footnote 27 Here and in the Densatil stupas, the arrangement of the goddesses is inverted, and they can be read from the centre towards the sides.

The group of the Sixteen Goddesses is followed by depiction of the Umbrella and the Vase, two other images belonging to the group of the Auspicious Symbols.

Immediately after them, the Seven Cakravartin Emblems are represented in a highly refined and delicate style: the Wheel, the triple flaming Jewel, the Queen (Fig. 23), the Minister (Fig. 24), the Elephant, the Horse and the Warrior (Fig. 25).Footnote 28

Fig. 23.

Fig. 24.

Fig. 25.

The Cakravartin Emblems are followed by the last two of the Eight Auspicious Symbols: the Shell (Fig. 25) and Fishes.

The sequence of female figures, as well as the symbols and emblems, in the Offerings Scroll is an important indication of the orientation of the painting. It should be interpreted from left to right, or clockwise, because this is the order of appearance of the images according to the sources. If we imagine unrolling the painting in an upright position around an imaginary circumference, the figures on it should be visible inside, the flames and vajras outside. In fact, in the Cakrasaṃvara thangka and in the repoussé figures of the Densatil stupas, the arrangement of the offering goddesses is inverted since they can be read from the centre towards the sides. In another Densatil panel, in the same tier, the arrangement of the deities with musical instruments is the exact contrary respect to that of the Offerings Scroll; here we see the bodies of the figures turned towards the centre.Footnote 29 The direction that they follow seems to be from left to right, but their hierarchical order with respect to the centre, and therefore to the main image, is from the right to the outside.

The last part of the Scroll is badly damaged and the last figures on it are not clearly visible. Possibly the first three of the Five Offerings of Sensory Enjoyment (pañcakāmaguṇāḥ, 'dod pa'i yon tan lnga) are represented here: the mirror (sight or form), cymbals, gongs or/and lute (sound), the incense-laden conch shell (smell), the fruit (taste) and the silk cloth (touch). Sometimes smell is also represented as the blossoms and leaves of fragrant flowers.Footnote 30

The hypothesis of the presence of the Five Offerings of Sensory Enjoyment is also borne out by some further evidence. The missing images must be part of a group of five symbols. As already explained, the junctures of the canvas segments are clearly visible on the Scroll. On each segment, eleven images are represented. The last sign of junction is between the Queen and the Minister, belonging to the group of the Seven Emblems of the Cakravartin. The next segment, being damaged, shows only ten figures, and the last three images are unfortunately not clearly visible. This means that the last segment of the painting has only the last image missing.

So, summing up again, the groups painted on this Scroll are the Eight Offerings Goddesses, the Sixteen Offerings Goddesses or Vajra Goddesses, the Eight Auspicious Symbols, the Seven Cakravartin Emblems and the Five Offerings of Sensory Enjoyment.

The background of the painting is red, with a green rim at the top and bottom and a thin yellow line in between.

Each image on the Scroll is surrounded by a fine green branch of a lotus plant, creating a scroll frame around the figures and symbols. The corollas of the lotus flowers become the bases on which the deities dance or the symbols stand.

This vegetal element forming roundel scrollwork motifs, is a common feature of what is called the Late Beri style.Footnote 31 In Mustang, this very common element is visible in paintings and sculptures in many temples and caves, such as the thirteenth-fourteenth-century cave temple of Trashi Geling, or the fifteenth-century paintings of the Champa and Thubchen Temples in Lo Manthang, for example, as well as some sculptures including the fifteenth-sixteenth-century altar with Śākyamuni and Bodhisattvas, kept in the Ghami Monastery (Fig. 26), or three fabulous halos (see Fig. 27 and Fig. 28) preserved in the Namgyal Monastery.

Fig. 26.

Fig. 27.

Fig. 28.

The Scroll of the Eight Charnel Grounds

The Namgyal Charnel Ground Scroll was painted for a mandala that in all probability belongs to the class of the Anuttarayoga-tantra, the highest class of Tantras in the Tibetan classifications.Footnote 32

The Aṣṭaśmaśāna-nāma, Eight Great Charnel Grounds (dur krod brgyad kyi bshad pa), all correspond to the eight cardinal directions: the four principal ones and the four intermediaries. These images of cemeteries represent the Eight places, well-known among the Indian ascetic schools, which Siddhas were accustomed to visit in order to accomplish, through their practices and yoga, their spiritual achievements. Of all these fearsome places, eight became very popular, not only in the context of Tantric Buddhism, but above all in the Tibetan Buddhist context.Footnote 33 There are not many sources on the Eight Cemeteries, and most of them have been lost. Only one is preserved in its original Sanskrit version: the Śmaśānavidhi by Lūipa.Footnote 34 According to Tucci,Footnote 35 further information on the Eight Charnel Grounds can be traced in several short texts in the Tengyur (bstan 'gyur)—for example, their names: in the East is the Cemetery named Caṇḍogra (gtum drag); in the North is Gahvara (tshang tshing can); to the West is Jvālākulakaraṅka or Karaṅka ('bar bas 'khrigs pa'i keng rus); in the South is Bhīsaṇa (’jigs sde); in the South-East is Lakṣmīvana (dpal gyi nags); in the South-West is Ghorandhakāra ('jigs pa'i mun pa); in the North-West is Kilikilārava (kīli kīlar sgrogs pa); to the North-East is Aṭṭahāsa (ha har rgod pa).Footnote 36

In all the representations of the Charnel Grounds, as in our example, we find the same figures and symbols in each Cemetery, some with their personal name and some with a generic appellation: a Mahāsiddha (grub thob chen po), a Nāga (klu), a Dikpāla (chos skyong) (the Guardians of the Directions), a Stupa (mchod rten), a KṣetrapālaFootnote 37 (zhing skyong), a mount, a cloud, a tree, fire, rocks, the Piśāka (srin po) demons, skeletons, fierce animals, parts of some dead bodies scattered all over the place, and so on (Fig. 3).Footnote 38

The position of the Dikpālas on this Scroll conforms to the usual orientation of the main mandalas dedicated to the wrathful deities, like those described in the Hevajra Tantra, for example, and the other sources cited here.Footnote 39 In this text it is specified that Yama (gshin rje) is in the South, Nairṛti (bden bral) in the South-West, Varuṇa (chu lha) in the West, Vāyu (rlung lha) in the North-West, Kubera (rnam thos sras) in the North, Īśāna (dbang ldan) in the Nort-East, Indra (brgya byin) in the East, and Agni (me lha) in the South-East.Footnote 40

The figures must be visible from the exterior of the mandala, so the Scroll had to be positioned standing with the Charnel Grounds outside and the flames and chain of vajra inside. The external position of the figures can be confirmed from the relationship between the figures and the cardinal points: Virūpa (bi ru pa) occupies the West direction, Yama the South, Kubera the North, for example; thus, in order to respect this position, the figures have to be placed outside.

The Charnel Grounds are always on the outsider circles or spaces of the mandalas, as we can see from several examples, including one of the oldest mandala thangkas dedicated to Cakrasaṃvara, preserved in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Fig. 29). In this early twelfth-century Nepalese style painting, the Charnel Grounds fill all the space of the canvas outside the ditch of flames, the most external circle surrounding the mandala proper. However, here it seems that the canonisation of the Charnel Grounds had yet to be concluded.

Fig. 29.

The position of the Namgyal Charnel Grounds Scroll, standing on the outside of a mandala, can also be seen in a twelfth-century Lotus Mandala dedicated to Hevajra, a metal work from Eastern India preserved in the Rubin Museum of Art, examined in depth by Robert Linrothe. In this marvellous object the figures stand on the outer petals of the flower and are clearly visible when the lotus is closed (Fig. 30).Footnote 41

Fig. 30.

Although none of the available sources tell us which specific Mahasiddha appears in each Charnel Ground, the visual source of the Hevajra Lotus Mandala in the Rubin Museum is very useful in this respect. The Eight Mahāsiddhas represented in this object are the same as those on our Scroll, although some of the figures are in different positions.

This Lotus Mandala is an important iconographic source to demonstrate that a clearly identifiable group of Eight Mahāsiddhas was already present in the twelfth-century artistic tradition of Eastern India.Footnote 42 As Linrothe pointed out, “over time, the exact constitution of the set gradually diverged from earlier Indian traditions and were modified by the preferences of particular lineages, highlighting teachers more or less important to the work's patron”.Footnote 43

But the relation between the Mahāsiddhas, the Dikpālas and the stupas is difficult to decipher without the texts in which this particular connection is described. As Christian Luczanits argues in his article on the role of the Pan-Indian deities in the Mandalas painted in the Nako temple, “Usually the connection between a particular deity or group of deities and a certain dikpāla is not specified in the texts; it reflects the Hindu religious tradition”.Footnote 44

The stupas represented on the Scroll are not stereotyped, simplified into a single generic representation, but each is recognisable. These are the Eight Stupas corresponding to the Eight Great Events of Śākyamuni's life.

The earliest Tibetan text that describes the specific characteristics of the eight types of stupas, associated with the Eight Great Events in the Buddha's Life and their sites, was composed by one of the renowned Sakya masters Dragpa Gyaltsen (grags pa rgyal mtshan, 1147–1216).Footnote 45 Dragpa Gyaltsen seems to have collected in his works all kinds of information on the stupas known to him, including the measurements.Footnote 46 Judging by the Sakya Master'sFootnote 47 interest in this subject, it is not surprising that the stupas in our Scroll are so precisely identifiable, since it was moreover painted in a Sakya context.

Their presence in the Charnel Grounds has a direct connection not only with death, by virtue of their original function as reliquaries, but above all with the Buddha's life, because they also symbolise specific episodes in his life. Each stupa, moreover, recalls the Śākyamuni's personal relationship with the Charnel Ground. In fact, various hagiographic traditions tell us that Śākyamuni spent a long period of his life in the cemeteries before he attained his awakening.Footnote 48 This means that when we are looking at those images we have to be aware of the different levels at which they can be read, which are not completely intelligible for us in all the cases without a textual source able to clarify the links among the symbolic meanings.

Regarding the structure and composition of the Charnel Grounds in the mandala, unusually, each of them in the Namgyal Scroll is demarcated by Chinese-style curved rocks (Fig. 31), instead of a river as the symbolic element that marks the boundaries.

Fig. 31.

Although the figures in the mandala should be read in a clockwise direction starting from the bottom, in the East cardinal direction,Footnote 49 according to the traditional direction of circumambulation, for the sake of convenience we will describe the images on the scroll from left to right but starting from the beginning of the canvas, and so from the North.

The first image of the Northern Charnel Ground, Gahvara (tshang tshing can), is Mahāsiddhas Śavaripa. Given the very poor condition of the canvas in this point, it is difficult to make this figure out, but from some very fragmentary details it is fairly clear that this Mahāsiddha is represented standing with his right leg bent, holding a bow in his left hand, as can be seen in several representations of this Mahāsiddha.Footnote 50 Subsequently we see the damaged figure of Kubera (rnam thos sras), with his consort presiding over the Charnel Ground. In this same Cemetery we can also glimpse the “Many Doors” Stupa, which commemorates the first sermon of the Buddha in the Deer Park of Sārnāth. It is characterised by the presence of many small square doors on the steps of the stupa.

In the North-Western Charnel Ground, Kilikilārava (kīli kīlar sgrogs pa), we find the Mahāsiddha Ghaṇṭāpa represented flying with his partner (Fig. 32). The faces of the two yogins are very carefully drawn and are highly expressive. In terms of style, the expressions and gestures of these figures can be compared with those of the fifteenth-century statues of the Mahāsiddhas from the Mindroling (smin grol gling) temple, attributed by David Jackson to the famous Tibetan artist Khyentse Chenmo (mkhyen brtse chen mo).Footnote 51

Fig. 32.

After Ghaṇṭāpa come the Nāga Kulika (rigs ldan)Footnote 52 (Fig. 32) and the Guardian of the North-Western Direction, Vāyu (rlung lha), together with his consort on a stag, under a tree inhabited by a stag-faced Kṣetrapāla (Fig. 33). The stag is painted in a naturalistic and extremely refined style. This way of depicting the animals shows the particular skill of this painter, who quite possibly took a personal interest in Himalayan and Indian fauna.

Fig. 33.

In the same Cemetery we can also see the stupa of the “Descent from Gods” (lha bab) (Fig. 3, Fig. 31), with the ladder in the centre of the steps, which recalls the episode of the Śakyamuni Previous Lives of the descent from heaven of the thirty-three Gods at Śānkāśya. It symbolises the coming of the Sugatas for the good of sentient beings.Footnote 53

Near the stupa there is a macabre scene: on the upper part, a dead body is surrounded by angry white-bearded vultures, intent on eating its bowels; below, a bird of prey is drinking blood from the throat of another corpse; on the lower part, a demon carries a dead body on his shoulders, accompanied by a dog and a weasel (Fig. 31).

In the Western Charnel Ground, Jvālākulakaraṅka or Karaṅka ('bar bas 'khrigs pa'i keng rus), we find the Mahāsiddha Virūpa, portrayed with a book in his hair (Fig. 34). He is accompanied by a female attendant wearing a white dress that rises over her head. The same attendant is painted with Virūpa in the fifteenth-century Lamdrè Lhakhang (lam 'bras lha khang) at Pelkor Chode (dpal 'khor chos sde), at Gyantse (rgyal rtse) (Fig. 35), and in various other temples. As in the Namgyal scroll, the female attendant is bringing a skull cup to Virūpa.

Fig. 34.

Fig. 35.

After the Mahāsiddha come the Nāga Karkoṭaka (stobs kyi rgyu) and Varuṇa (chu la) with his partner on the Makara, as well as the “Great Miracle” stupa (cho ’phrul) (Fig. 36). It is worth noting that the stupa of the Great Miracle is associated with Virūpa, who is portrayed performing a miracle.

Fig. 36.

In the South-Western Charnel Ground, Ghorandhakāra ('jigs pai mun pa), an unknown Mahāsiddha is depicted (Fig. 37), possibly Indrabhūti, as indicated by the parasol, symbol of royalty, held over his head by his attendant, but he might also be Khana, disciple of Virūpa.

Fig. 37.

The Nāga Ananta (mtha yas) precedes the Dikpāla Nairṛti (bden bral) and his partner on a Vetāla (Fig. 38).Footnote 54

Fig. 38.

This particular creature, the Vetāla, sometimes called ‘zombie’, is here depicted as a corpulent and muscular man, with a black beard, ruffled hair and dark and thick eyebrows. His wrathful face is drawn in a somewhat Chinese style, with big eyes painted with firm brush strokes. His body is shown in a twisted position, which brings out his mighty muscles.

The stupa of the “Complete Victory” (rnam rgyal), which belong to this section, has three round steps that symbolise the Three Doors of Deliverance.Footnote 55 It recalls the prolongation of lifetime by three months, apparently another event that took place at Vaiśāli. Here, too, it is worth noting how the zombie, a creature that survives death, albeit in unfavourable conditions, is represented in connection with the idea of the prolongation of Śakyamuni's life.

In the Southern Charnel Ground, Bhīsaṇa ('jigs sde), we see the Mahāsiddha Kukkuripa with his affectionate black dog (Fig. 39). Not far from them, a Piśāka—a particular cannibal demon—is devouring the arm of a dead body. The Nāga of this Cemetery is Padma (pad ma).

Fig. 39.

The cemetery is presided over by Yama (gshin rje) and Yami on their buffalo. Here we can also see the stupa of “Heaped Lotuses” (sku bltams), which symbolises the birth of Śākyamuni in Kapilavastu, in the Lumbinī garden (Fig. 40). All four steps of the stupa are covered with lotus petals.

Fig. 40.

It is worth noting that Yama, the God of Death, is associated here with a stupa symbolising the Buddha's birth. The significance of this association may be related to the Buddhist belief in the permanent cycle of death and rebirth. This is not the first time that we have found the lotus, a symbol of rebirth, purity and awareness, associated with death and charnel grounds, already seen on the bronze Lotus Mandala in the Rubin Museum.Footnote 56

At the end of this Charnel Ground is one of the most rare and fascinating representations in this painting: a detailed depiction of ‘sky burial’ (Fig. 41). The different sequences of this traditional form of treating the dead body are described as if in a movie frame. Two monks are playing some musical ritual instruments, including cymbals and a trumpet fashioned with a conch-shell,Footnote 57 while another man, probably a monk, bears on his shoulders a dead body in a foetal position, wrapped in a white cloth. We can sense the effort the man is making, despite his visible robustness, by the expression on his face and his bare legs, his garment wrapped around his thighs, possibly in order to walk more freely amid the rocks. A monk is depicted during performance of a ritual, with the vase and a ritual plant used for different kinds of offering ceremonies. Another monk, maybe the same seen carrying the dead body, is cutting the body up with a ritual knife normally used for skinning. Blood rivulets pour forth from the corpse, and a flock of hungry white vultures are starting to eat the fresh human flesh.

Fig. 41.

An interesting detail can tell us something more about the painting: the white garments under the monk's robes. This kind of dress is worn by some Sakyapa practitioners and is indicative of a special attitude these monks have towards their religious practice. Also, on the basis of other iconographic evidence, such as the presence of Mahāsiddha Virūpa, particularly worshipped by Sakyapa, we could hypothesise that this painting was made in a Sakya cultural context.

In the South-Eastern Charnel Ground, Lakṣmīvana (dpal gyi nags), we see the Siddha Ḍombi Heruka with his partner (Fig. 42). They are riding on a marvellous tiger, unfortunately not completely visible due to the poor condition of the canvas. In my opinion, this is one of the most beautiful representations of the Ḍombi Heruka's tiger. The feline crouches as if to pounce on its prey. The tiger's ears are lowered in a threatening attitude and its jaws are wide open showing its canines.

Fig. 42.

This Cemetery is presided over by a highly refined representation of Agni (me lha) and his partner, who tenderly pets the goat on which they are seated (Fig. 43). The Nāga depicted here is Mahāpadma (pad ma chen).

Fig. 43.

Next to the image of an impaled cadaver—a typical image in the cemetery scenes—is depicted the Stupa of the “Conquest of Mara” (byang chub). This one is the Stupa of the Great Enlightenment, of the awakening at Bodhgāya. It is worth noting how the theme of awakening is associated here with the fire and the light, both symbolised by Agni.

On the Eastern Charnel Ground, Caṇḍogra (gtum drag), we see a carefully depicted Mahāsiddha Saraha seated on an antelope skin bearing an arrow (Fig. 44). His facial features are shown in close detail and his expression is very naturalistic. This specific Saraha iconography is common in later representations of this Siddha, as can be seen in various different thangkas. The Saraha iconography depicted in the Namgyal's Scroll may, indeed, be one of the first examples showing this peculiar model to represent the Mahāsiddha appears.

Fig. 44.

After the Nāga Vāsuki we can recognise Indra (brgya byin) with his consort on the elephant (Fig. 45). The Kṣetrapāla with the elephant's head appears through the branches of the tree. The stupa of this Charnel Ground is the “Reconciliation” stupa (dbyen bsdum), with octagonal tiers that recalls two moments: one relating to Śākyamuni's previous lives, with the taming of the Elephant Nālāgiri at Rājgir, and one of the Eight Great Events, the reconciling of the factions of the Sangha divided by Devadatta. The symbolic significance of this stupa evokes the way in which the Buddha acts, always for the good of sentient beings, often through many miraculous transformations. Here we have a curious association between the event at Rājgir, which has an elephant as protagonist, and the vehicle of Indra.

Fig. 45.

The North-Eastern charnel ground is, unfortunately, totally missing.

At this point, having described each of the Charnel Grounds, I would now like to highlight some aspects and details of the painting and offer some considerations.

An interesting characteristic of this painting is the shape of the stupas’ domes, like flattened spheres. Apparently, this shape was common in Mustang during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. There are many portable stupas of this kind in metal in the Namgyal Monastery Collection, for example.

The “Great Miracle” Stupa (Fig. 46), painted in the Western section of the Scroll, is similar to a fifteenth-century metal sculpture, part of the metal stupa Collection in the Namgyal Monastery (Fig. 47).

Fig. 46.

Fig. 47.

Another comparison could be made between the “Descent from Gods” stupa (Fig. 31), painted in the north-western section of the scroll, and the same type in the metal stupa collection of Dzong Monastery (fifteenth-sixteenth century) (Fig. 48).

Fig. 48.

In this case, on the evidence of the sculptures, we can have a better idea of the particular shape of those stupas. In fact, this typology presents a sort of forward projection that is only suggested by a line in the painting but which is clearly visible in the metal model. Furthermore, these sculptures can offer a term for dating, being interesting examples of the artistic metal production of Mustang during the fifteenth-sixteenth centuries.

In general, these portable stupas, or miniature stupas, in different shapes and materials, are often to be found in the Himalayan Monasteries. Sometimes they were also used for specific offering ceremonies or festivities, like those still held in the Nepal Valley today. The function of miniature stupas, besides that of enabling the donors who commissioned their execution to accumulate merits, is connected to ceremonial and ritual Newari celebrations. During these celebrations, stupas of the kind are exhibited by believers in the streets, forming a sort of long pathway of pilgrimage. These ritual processions are held in a number of centres in the Valley at different times of the year.Footnote 58

Returning to our painting, stupas with the same shape are also to be seen in some wooden book covers kept in the Namgyal (Fig. 49) and other monasteries of Mustang.Footnote 59 The stupas are commonly carved on the sides of the thick book covers; they face the wall when the books are stored in the library and thus are not generally visible.Footnote 60

Fig. 49.

Sometimes the stupas are also carved in the front of the wooden cover as in a fifteenth-century example preserved at Tsarang Monastery (rtsa rang) representing three Buddhas in dharmachakra-mudra, surrounded by their retinue. On the edge of the cover we also find the Eight Stupas represented: four in the corners and four on the sides. This cover shows the Eight Stupas positioned: on the lower side thus; in the centre, is the “Heaped Lotuses” stupa; in the lower left corner the “Conquest of Mara”; in the centre left side the “Many Doors”; in the upper left corner the “Great Miracle”; in the upper centre side is the “Descent from the Gods”; in the right upper corner the “Reconciliation”; in the right centre side is the “Complete Victory”; and in the right lower corner the “Parinirvana”. As in the case of another cover preserved in Tsarang, but not only there, we can see different orientations of the Eight Stupas within the space. This means that the stupas, despite being linked with the cardinal directions, do not always follow the same order.

Other aspects to highlight are the beautiful animals that populate the Charnel Grounds. This aspect could also contribute to dating the painting. For example, if we take a close look at Indra's elephant (Fig. 45) we can see that the head of the animal is in a style typical of Nepali and Indian painting. From the fifteenth-century onwards, it became rare to find representations of elephants painted in such a naturalistic manner, the Tibetan painters no longer being familiar with these ‘exotic animals’.

The style of the elephant head on the Charnel Ground Scroll has many similarities to other depictions, such as those painted in Shalu in the fifteenth century (Fig. 50), the difference being that in the Charnel Ground Scroll the legs are similar to the legs of a horse, a common feature in Himalayan paintings from the fifteenth century on. An elephant seated in a position like a horse is to be seen in a fifteenth-century manuscript kept in the Namgyal Monastery (Fig. 51). This painting may have been executed in a transitional period, around the end of the fifteenth century/early sixteenth century, during which the painters were influenced by Nepali models but they had also started to look at Tibetan models.

Fig. 50.

Fig. 51.

Regarding the landscape, the Charnel Ground Scroll has a background divided into two parts: one blue, for the sky, and one faded green, for the meadow. Against the background of these shades of colours stand out Chinese-style rocks—a feature originating from China but still visible in the Himalayan art since the fifteenth century—and lush trees burgeoning with orange fruits. Each Dikpāla, or Direction Deity, has a tree bearing orange fruits in the background (Figs. 33, 36, 38, 40, 43, 45). The Charnel Ground trees are listed by the sources: śirīṣa (acacia sirissa), cūta or āmra (mangifera indica), aśvattha (ficus religiosa), vaṭa (ficus bengalensis), karañja latāparkaṭī (pongamia glabra), pārthiva or arjuna (terminalia arjuna), aśoka (saraca asoca) and barura (prunus cerasifera).Footnote 61 Most of them have fruits in different shades of orange, like those in the Namgyal Scroll. These symbols of life and prosperity, creating such a luxuriant impression, are to be viewed in connection with the Dikpālas represented in front of them.

A tree with orange fruits is also painted in a sixteenth-century manuscript illumination depicting Indra and preserved in the Namgyal Monastery (Fig. 52). The same type of tree is common in many other different miniature paintings kept in the same Monastery (Figs. 53, 54). The same tree with fruits can also be seen on the back of some fifteenth-century book covers in the Namgyal Collection. In one of these (Fig. 55) we also see similar types of rocks.

Fig. 52.

Fig. 53.

Fig. 54.

Fig. 55.

With regard to the style, this painting has some intriguing features including, for example, the use of colour. Even though the original pigments have lost their brilliance, it is clear that they were originally pastel colours. A similar technique was apparently in vogue, in the Himalayan context, in later centuries, around the 1700s, as in the case of a portrait of an unidentified KarmapaFootnote 62 painted in the eighteenth century and preserved in the Rubin Museum of Art, as well as another of Dralha Yesi Gyalpo (dgra lha ye si rgyal po), painted in the nineteenth century,Footnote 63 and an astrological scrollFootnote 64 made in the eighteenth century, also part of the Rubin Museum Collection.

Other examples are the illuminated manuscripts preserved in the Library of the Namgyal Monastery (Figs. 56, 57). The style of these miniatures is less detailed and less carefully drawn, but similar from a technical point of view. Some elements depicted in the miniatures are similar to our Scroll, such as the Chinese-style rocks on the background behind the figures (Fig. 56). There is also a portrait, in this manuscript, of the Mahāsiddha Virūpa (Fig. 57), slightly different from that of the Charnel Grounds Scroll in terms of iconography, but quite similar in terms of style.

Fig. 56.

Fig. 57.

There are many different examples of this characteristic use of colours, leaving some parts of the canvas surface empty in a way that highlights the drawing rather than the painting. But all the examples belong to a period later than that of the Charnel Ground Scroll in the Namgyal Collection. It may, indeed, quite possibly be one of the first artistic examples of this kind of technique.

Both in style and iconography, the topos of the Charnel Grounds of the Namgyal Scroll could be compared to the paintings of the Upper Gonkhang in the Gongkar Dorjeden (gong dkar rdo rje gdan) Monastery, painted by the renowned artist Khyentse Chenmo (mentioned above), started in 1464.Footnote 65 In the Gongkar paintings some characters are represented in the same posture as the characters on the Namgyel Scroll, like the man that carrying a dead body on his shoulders,Footnote 66 or some of the animals, in particular vultures and jackals represented in the landscapes of both paintings.Footnote 67 The use of colours and the choice of a pastel paletteFootnote 68 is quite similar in Gongkar and in the Charnel Ground Scroll, as well as the style of some details, like the flames. We may wonder whether the painter who made the Charnel Ground Scroll had seen the paintings at Gongkar, or had, perhaps, some of these iconographic features, already been described in some artistic manuals or texts available to the artists of the period?

The style of the Charnel Grounds Scroll is a mixture of Newari, Central Tibetan—in particular Khyenri (mkhyen ris)—and Chinese style, with authentic original features that make this painting extraordinary and unique.

Conclusions

The two Scrolls stored in the Namgyal Monastery Collection are marvellous examples of the second half of fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century artistic production of Mustang. They reflect the intense religious vitality of that particular historical period. These rare sacred ritual objects are ancient evidence of a type of practice, now most likely lost, related to the mandala rituals. The Offerings Scroll is painted in a typical Newari style common in Mustang during the late fifteenth century, while the Charnel Grounds Scroll shows strong influences of the Khyenri style, newari and Chinese and was probably made during the early sixteenth century.

The complexity and accuracy of the iconographic programme of these two Scrolls make of them fundamental sources to understand the function of the mandalas in depth. It is extremely rare, in terms of iconography, to have complete representations of the Charnel Grounds, for example, with all the elements precisely identifiable.Footnote 69 This painting has an important role also in this respect: as far as I know, it may well be the only example of a complete and detailed depiction of a version of the Eight Charnel Grounds.

The two Scrolls are, thus, both examples of the important role played by art in the Buddhist context, particularly when the visual sources are more detailed than the texts. This both inspires us and corroborates the fact that images and symbols are essential for meditation, for visualisation, and for inviting the gods to take part in esoteric rituals, as mnemonic reference points along the complicated path towards Awakening.