Introduction

The number of people with dementia (PwD) is rising every year. By 2050, there will be approximately 131 million PwD worldwide (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2015). It has therefore been perceived as one of the greatest problems facing society in the 21st century (Alzheimer's Society, 2014).

The majority of PwD are community-dwelling and cared for by a spouse or an adult child, typically of the female gender (Alzheimer's Research UK, 2015). The increasing number of dementia cases means that the number of informal care-givers (unpaid relatives or friends) of PwD is also increasing. Research indicates that informal care-givers of PwD can experience positive benefits from the acquisition of the care-giving role, such as feeling as though family members have come closer together and appraising life as more fulfilling and meaningful (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Colantonio and Vernich2002). However, there is an abundance of literature that suggests that the role can lead to the presence of perceived burden (e.g. Brodaty and Donkin, Reference Brodaty and Donkin2009; Chiao et al., Reference Chiao, Wu and Hsiao2015) and psychological difficulties. The strongest evidence base is for the presence of depressive symptoms that are more severe than those found in older adults who are not care-givers (Vitaliano, Reference Vitaliano1997) and care-givers of people without dementia (Pinquart and Sörensen, Reference Pinquart and Sörensen2003).

Burden

In this review, ‘care-giver burden’ (here on referred to as ‘burden’) is conceptualised as a multi-dimensional biopsychosocial reaction (Given et al., Reference Given, Given, Azzouz, Kozachik and Stommel2001) that results from the care-giver's perception of the degree to which the care recipient is dependent upon them and the care-giving role has had a negative impact upon their emotional health, physical health, and social or financial status (Zarit et al., Reference Zarit, Todd and Zarit1986). Literature has frequently attempted to distinguish ‘objective’ from ‘subjective’ burden, although this distinction still remains unclear. The current burden definition is based on that of Zarit et al. (Reference Zarit, Todd and Zarit1986) which has been suggested to include ‘objective burden’ concepts (e.g. physical, social and financial impacts, and level of dependency) and ‘subjective burden’ concepts (e.g. the care-giver's perceptions and the emotional impact of care-giving), and is in line with most of the well-established and validated care-giver burden measures (Vitaliano et al., Reference Vitaliano, Young and Russo1991).

When taking into account this burden definition and the research comparing the experiences of care-givers of people with and without dementia, it becomes clear why care-givers of PwD might perceive greater burden. Care-givers of PwD tend to spend more hours per week on care-giving tasks, assist with a greater number of activities of daily living, report more employment complications, and less time for leisure and social activities due to care-giving responsibilities (Ory et al., Reference Ory, Hoffman III, Yee, Tennstedt and Schulz1999), and spend more of their own money on care-giving expenses (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2016). In addition to this, many PwD display aggressive behaviours, the presence of which increases perceived burden (Ornstein and Gaugler, Reference Ornstein and Gaugler2012). Interestingly, the higher the burden experienced by care-givers of PwD, the more likely they are to expedite nursing home placement (Gaugler et al., Reference Gaugler, Kane, Kane and Newcomer2005).

Research exploring burden in care-givers of PwD has tended to focus on the relationships between burden and psychological constructs such as depression, and predictors of burden. This has revealed that depressive symptoms and burden are positively correlated with one another (Epstein-Lubow et al., Reference Epstein-Lubow, Davis, Miller and Tremont2008; Medrano et al., Reference Medrano, Rosario, Payano and Capellán2014). Moreover, that there are significant patient-related predictors of burden such as the patients' severity of dementia, behavioural problems or psychological symptoms and extent of personality change, and care-giver-related predictors including socio-demographic variables and psychological health (Etters et al., Reference Etters, Goodall and Harrison2008; Chiao et al., Reference Chiao, Wu and Hsiao2015). These studies have therefore been significant in uncovering the potential difficulties that may be experienced by those with perceived burden and the types of factors that increase a care-giver's vulnerability to experiencing perceived burden. However, to our knowledge, there has been no meta-analytic review of the prevalence of burden among informal care-givers of PwD. Determining this would appear vital to further our psychological understanding of this population and help inform the provision of services.

Depression

Depressive symptoms can include a persistent sadness/low mood, marked loss of interest or pleasure in activities, disturbed sleep, decreased or increased appetite or weight, loss of energy, poor concentration, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, and/or suicidal ideation or acts (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013). To fulfil the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) criteria for major depression at least one of the first two symptoms must be present alongside five of the remaining symptoms nearly every day for at least two weeks (APA, 2013). There are numerous self-report measures that have been designed to map on to the diagnostic criteria for depression, include specified cut-offs to determine depression, and have been validated in older adult populations. The most frequently used measure in research on care-givers of PwD is the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, Reference Radloff1977).

Care-givers who have depression typically experience problems in daily functioning and poorer physical health (Gallagher et al., Reference Gallagher, Rose, Rivera, Lovett and Thompson1989; Cucciare et al., Reference Cucciare, Gray, Azar, Jimenez and Gallagher-Thompson2010). In addition, a large cross-sectional study of 566 informal care-givers of PwD revealed that approximately 16 per cent had contemplated suicide more than once in the previous year (O'Dwyer et al., Reference O'Dwyer, Moyle, Zimmer-Gembeck and De Leo2016). Although a smaller longitudinal study found the prevalence of suicidal thoughts to be substantially lower than this at approximately 5 per cent (Joling et al., Reference Joling, O'Dwyer, Hertogh and Hout2018), both studies reported depression to be a risk factor for suicidal ideation. Therefore, at least, depression can compromise a care-givers' ability to maintain their role effectively and, at worst, it can lead to suicide, demonstrating why investigating the prevalence of depression among this population is important.

A previous meta-analysis found a moderately significant difference in depressive symptoms between informal care-givers of PwD and people who were not care-givers (Pinquart and Sörensen, Reference Pinquart and Sörensen2003). This review, however, did not evaluate the prevalence of depression among either group. A meta-analysis conducted 13 years ago estimated the pooled prevalence of depressive disorders among informal care-givers of PwD, assessed via interviews based on the DSM-III(-R)/IV (|APA, 1980, 1987, 1994) or the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10; World Health Organization (WHO), 1992). This was found to be approximately five times higher than that of the general population, at 22.5 per cent (Cuijpers, Reference Cuijpers2005). A more recent meta-analysis by Sallim et al. (Reference Sallim, Sayampanathan, Cuttilan and Ho2015) estimated the pooled prevalence of depression among care-givers of people with Alzheimer's disease (AD), measured via self-report instruments, to be 34 per cent. However, these reviews included relatively small numbers of studies: ten (Cuijpers, Reference Cuijpers2005) and 13 (Sallim et al., Reference Sallim, Sayampanathan, Cuttilan and Ho2015).

A contextual model (Figure 1) by Williams (Reference Williams2005) adapted from that of Dilworth-Anderson and Anderson (Reference Dilworth-Anderson, Anderson, Light, Niederehe and Lebowitz1994) conceptualised the factors that may influence the likelihood of a care-giver of someone with dementia experiencing depression. Among other factors, gender and the relationship to the care recipient were posited to influence this likelihood.

Figure 1. The conceptual model for understanding the effects of context on emotional health outcomes among care-givers of people with dementia.

Indeed, one meta-analysis found the prevalence of depression to be higher in female and spousal care-givers of people with AD compared to male and non-spousal care-givers of people with AD, respectively (Sallim et al., Reference Sallim, Sayampanathan, Cuttilan and Ho2015). However, this review was limited to care-givers of people with AD and, due to the extremely small number of included studies in each meta-analysis (N = 3) and the lack of assessment of publication bias, findings may not be robust. It is important to note that using meta-analytic approaches to investigate the influence of the other contextual factors presented in the adapted model of Williams (Reference Williams2005) on depression would not be appropriate, given that research often presents these factors as summary data and conducting moderator analyses on such data would introduce aggregation bias (Harbord, Reference Harbord2010).

There are many psychological interventions that are being delivered to and adapted for informal care-givers of PwD, such as Compassion-Focussed Therapy (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Gilligan and Poz2018) and Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (e.g. Hoppes et al., Reference Hoppes, Bryce, Hellman and Finlay2012). Determining the current prevalence of burden and depression is important to quantify the need for such programmes and the requirement to develop, adapt or change the availability of existing treatments to fulfil the needs of this client group, and so help delay and reduce rates of transition into care homes (Gaugler et al., Reference Gaugler, Kane, Kane and Newcomer2005; Alzheimer's Disease International, 2013).

The study aimed to address the gaps in the literature on burden and depression by conducting a current comprehensive meta-analysis with the following objectives:

(1) To quantify the prevalence of burden and depression among informal care-givers of PwD.

(2) To compare the prevalence of depression among female and male care-givers and spousal and non-spousal care-givers.

(3) To explore moderator variables including the methodological quality.

Method

The meta-analysis adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA; Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009).

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included if they were written in English or Japanese, as both authors are fluent in English and the second author is fluent in Japanese, and used observational study designs (see Munn et al., Reference Munn, Moola, Lisy and Riitano2014) including prospective and retrospective longitudinal cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies and studies that analysed baseline data from other studies of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). All other study designs were excluded, such as experimental studies, qualitative studies and review articles.

The population studied were informal care-givers of PwD. Studies involving care-givers of people without dementia or professional care-givers (e.g. paid support workers) were excluded. There were no limitations on the gender or age of the care-givers, the dementia type of the care recipients, or the setting or time spent as a care-giver. Studies were included if they sought to recruit a representative sample of its population. Studies were therefore excluded if they recruited only care-givers with specific mental or physical health difficulties, or they actively excluded care-givers experiencing a depressive episode.

Similar to the meta-analyses of Krebber et al. (Reference Krebber, Buffart, Kleijn, Riepma, Bree, Leemans, Becker, Brug, Straten, Cuijpers and Verdonck-de Leeuw2014) and Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Wu, Lai, Long, Zhang, Li, Zhu, Chen, Zhong, Liu and Wang2017), studies were included if they reported the number or percentage of individuals with depression assessed by semi-structured or structured diagnostic interviews based on criteria by DSM-III(-R)/IV or ICD-10, or validated self-report measures with specified clinical cut-offs. Studies were included if they reported the number or percentage of care-givers that scored above a specified cut-off for burden on a burden measure that was in line with the study's definition, and had evidence of high internal consistency, validity and being an effective tool for assessing burden in care-givers of PwD; for instance, the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI; Novak and Guest, Reference Novak and Guest1989) and the most widely referenced burden measure, the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI; Zarit et al., Reference Zarit, Reever and Back-Peterson1980). The cut-off point for the presence of mild to severe burden on the 22-item ZBI is >21. Studies not reporting depression or burden prevalence data were excluded.

Initially, articles published in any year were included. However, during the screening of full-text articles the authors decided that only studies published from the year 2000 onwards were eligible for inclusion. This decision was made because a number of factors have changed substantially from prior to the year 2000 to the present day which could have impacted upon the accuracy of the current prevalence estimates of depression and burden. For example, in the 1980s, older adult services in the United Kingdom (UK) rarely diagnosed dementia, it was common for PwD to be hospitalised and there was a lack of psychologically informed care (Brooker, Reference Brooker2017). In contrast, from around the 1990s there has been an increase in the formal diagnosis of dementia and a shift towards community-based care, with most PwD today living in the community and receiving care from a relative or friend (Schulz and Martire, Reference Schulz and Martire2004). The evidence base for and provision of psych-osocial and psychological interventions (e.g. Cognitive Simulation Therapy; Spector et al., Reference Spector, Thorgrimsen, Woods, Royan, Davies, Butterworth and Orrell2003) has also grown. Other factors taken into account included lifestyle changes and technological advances, the increase in the prevalence of depression in the general population (WHO, 2017) and the reduction in stigma towards depression in the last 20 years (Taylor Nelson Sofres British Market Research Bureau, 2014) – potentially increasing the likelihood of care-givers disclosing depressive symptoms.

Information sources

A comprehensive search of the literature was conducted. The databases of PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, MEDLINE Complete, SCOPUS and Web of Science were searched to identify relevant published articles. Unpublished articles including dissertations and theses were sought through the ProQuest global database. Hand searches were performed on the reference lists of included studies and relevant prevalence reviews and meta-analyses obtained via the Cochrane Online Library.

Search

The first author performed the search using the keywords and search strategies outlined in Table 1. All databases were searched from their inception to 31 October 2017 and no limits were applied to language.

Table 1. Search strategy and key terms

Notes: For the databases PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO and MEDLINE Complete the key words in the ‘epidemiology concept’ were searched for in the abstracts of texts and the ‘burden/depression’ and ‘participants’ concepts in the title of texts. The SCOPUS search was limited to articles, reviews and conference papers, and all key words were searched for in the titles and abstracts of articles. The key words were searched for in the titles of texts within the Web of Science database and abstracts of texts within the Proquest database.

Study selection

The results of the searches were merged using EndNote software (version X8.0) and duplicate articles were removed. Eligibility assessment was conducted in a non-blinded manner. The first author performed the initial screening of the titles and abstracts, whereby clearly irrelevant articles were excluded. Full-text articles were screened by both authors independently using a structured checklist created by the first author (see the online supplementary material). The kappa coefficient was 0.68 indicating substantial agreement (Cohen, Reference Cohen1960). Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussions. When data from studies overlapped, the report with the largest sample size or data-set was included.

Data collection process

The first author developed an electronic database which was pilot tested on a randomly selected study by both authors collaboratively and refined accordingly. In order to reduce errors and minimise bias, both authors independently extracted the data from 11 of the included studies (10%) and results were compared, with no significant discrepancies identified. Data extraction was completed on the remaining studies by the first author independently and the data transferred to the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (CMA version 3; Borenstein et al., Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2005).

Data items

Information was extracted from each study based on (a) characteristics of the study (including year of publication, country, design, recruitment process, sample size and instruments used to assess depression and/or burden); (b) characteristics of the care-givers (including the definition given for a care-giver, mean age, percentage female, race, nationalities, average length of time spent care-giving in months, percentage employed, percentage married, mean years of education, and types and percentages of relationships held with the care recipients); (c) characteristics of the care recipients (including procedure used to diagnose dementia, percentages of the types of dementia diagnoses and severity of dementia – primarily measured by a mean Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score); (d) depression and burden outcome data (including the number or percentage of participants within the sample that were diagnosed with depression or scored above the specified clinical cut-off, and the number or percentage of females and males, and spouses and non-spouses that were diagnosed with depression or scored above the specified cut-offs). Information was not inputted if it was missing or unclear and not made available by study authors.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The bias risk of each study was investigated using a 13-item list (Table 2) adapted from existing criteria lists (Luppa et al., Reference Luppa, Sikorski, Luck, Ehreke, Konnopka, Wiese, Weyerer, König and Riedel-Heller2012; Krebber et al., Reference Krebber, Buffart, Kleijn, Riepma, Bree, Leemans, Becker, Brug, Straten, Cuijpers and Verdonck-de Leeuw2014). Quality rating scales for RCTs tend to generate an overall score of study quality or separate quality scores in key domains. The assessment tool used in this review measured the level of risk that each study posed to the reliability of the specific outcomes of the current review. Adaptations to the list were therefore made with regards to the population being studied and focused on: (a) the description of the care-givers including information about the care recipients' diagnosis and (b) the representatives of this population. Items for the description of the care-givers included socio-demographic characteristics (age and gender, and at least one of the following four: marital status, education, employment or socio-economic status), inclusion and exclusion criteria, dementia diagnostic procedure, dementia diagnoses and severity, time spent as a care-giver, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and information about (a history) of psychiatric problems of the care-givers. Items of the representativeness of the study population included sample size >100, description of participation or response rate and this being at least 75 per cent, reasons for non-response/non-participation presented or a statistical comparison of the characteristics of responders and non-responders, description of the recruitment process and use of a consecutive sampling method. A risk item was given a positive score if the study provided adequate information. If the information was incomplete or unclear, a negative score was given. If a study referred to another publication describing relevant information about the first study (e.g. recruitment process), the additional publication was obtained to score the item of concern. For each study, a total bias score was calculated by counting the number of criteria scored positively; therefore, the highest total score available was 13. A study was considered of low bias risk if the score was at least 75 per cent of the total, of medium bias risk if it was between 50 and 75 per cent of the total, and high risk if below 50 per cent of the total.

Table 2. Thirteen-item adapted bias risk assessment tool

Notes: Low risk: ⩾9.75. Medium risk: ⩾6.5 to <9.75. High risk: <6.5.

The risk assessment tool was pilot tested on a randomly selected study by both authors collaboratively and refined accordingly. Subsequently, the authors independently rated 11 randomly selected studies and compared the results. There were a few discrepancies between the ratings. If a risk item was rated positively by one author but not the other, a discussion was held and often the conservative value was chosen. The remaining studies were assessed by the first author independently.

Summary measures

Meta-analyses were conducted by computing the event rate of depression and burden using CMA (Borenstein et al., Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2005).

Synthesis of results

Effect sizes (event rates), their 95 per cent confidence intervals (95% CI) and associated z and p values were computed using the number of care-givers who scored above the specified cut-offs for depression or burden and sample size. As considerable heterogeneity of event rates was expected, the pooled prevalence estimate and its 95% CI were calculated using a random-effects model. To assess for heterogeneity among studies, the chi-squared statistic (Q; Higgins and Thompson, Reference Higgins and Thompson2002) and I-squared statistic (I 2; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003) were computed. I 2 provides a percentage of the total observed variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than chance and is not affected by low statistical power. An I 2 of 25 per cent is considered low, 50 per cent moderate and 75 per cent high.

Risk of bias across studies

Publication bias was assessed by constructing funnel plots, and conducting the trim and fill method (Duval and Tweedie, Reference Duval and Tweedie2000) and Rosenthal's Fail Safe N (Rosenthal, Reference Rosenthal1979). The trim and fill method estimates how many studies could be missing from each meta-analysis, corrects the funnel plot symmetry and calculates adjusted effect size estimates. Rosenthal's Fail Safe N determines how many studies with a null result would be needed to nullify the pooled prevalence estimate. If only a few studies (e.g. five or ten) are required to cause the pooled prevalence estimate to become non-significant caution is held over the robustness of the results (Borenstein et al., Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2009).

Additional analyses

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine whether the burden pooled prevalence estimate would have differed substantially if a study that measured ‘persisting’ burden (Epstein-Lubow et al., Reference Epstein-Lubow, Davis, Miller and Tremont2008) was omitted. As samples enrolled in RCTs could differ from samples which are not, a random-effects sub-group analysis was performed to determine whether prevalence estimates differed according to whether studies used a cross-sectional sample or one taken from an RCT at baseline.

Odds ratio effect sizes, their 95% CI, and associated z and p values were computed on the proportion of female care-givers compared to male care-givers that were classed as depressed, and the proportion of spouses compared to non-spouses that were classed as depressed. Two meta-analyses using random-effects models were conducted to ascertain the overall odds ratio estimates and their 95% CI.

A random-effects meta-regression investigated the relationship between study quality and the prevalence estimates of depression and burden. A random-effects sub-group analysis was also conducted to determine whether depression prevalence estimates differed according to the type of measure used to assess depression and the continent on which the study was conducted.

Results

Study selection

The database searches produced 8,568 articles and hand searching produced 35 articles, resulting in a total of 8,603 studies (Figure 2). After the removal of 1,905 duplicates, 6,698 titles and abstracts were reviewed, with 6,584 articles deemed clearly irrelevant and excluded. The full texts of the remaining 114 articles were screened, with 71 not fulfilling criteria and 43 studies included in the meta-analysis.

Figure 2. PRISMA flowchart of information from identification to inclusion of studies.

One study used a higher cut-off for the burden measure compared with other included studies that used the same measure, as it assessed ‘persisting burden’ rather than the presence of burden (Epstein-Lubow et al., Reference Epstein-Lubow, Davis, Miller and Tremont2008). The authors included the study and assessed its potential impact via additional analyses.

Study characteristics

The key characteristics of the 43 included studies are provided in Tables 3A and 3B. The total number of participants included in the meta-analysis was 16,911. Most of the studies were conducted in Europe (19), followed by North America (16), Asia (three), Australia (three) and South America (two). The majority of studies used cross-sectional designs (28), with the remaining studies using baseline RCT data (eight), adopting a longitudinal prospective cohort design (four) and using baseline data from longitudinal prospective cohort studies (three). The recruitment procedures varied greatly across studies. Sixteen recruited from multiple different platforms. For example, Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Lam and Kwok2013) recruited care-givers from memory clinics, outpatient clinics, day hospitals, day care centres and social services. Seventeen recruited from one database or service, and ten recruited from two or more of the same types of service, such as memory clinics (e.g. Brodaty et al., Reference Brodaty, Woodward, Boundy, Ames and Balshaw2014).

Table 3A. Characteristics of included studies

Notes: N = 43. N/A: not available. Location: AL: Alabama; CA: California; FL: Florida; IL: Illinois; MA: Massachusetts; MN: Minnesota; NY: New York; OH: Ohio; OK: Oklahoma; OR: Oregon; PA: Pennsylvania; RI: Rhode Island; TN: Tennessee; TX: Texas; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America; UT: Utah. Design: RCT: randomised controlled trial. See Table 3B for abbreviations for dementia diagnostic tools, dementia terms and depression measures.

Table 3B. Characteristics of included studies

Notes: N = 43. N/A: not available. Dementia diagnostic tools: CAMDEX: Cambridge Mental Disorders of the Elderly Examination (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Tym, Mountjoy, Huppert, Hendrie, Verma and Goddard1986); CDRS: Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Berg, Danziger, Coben and Martin1982); DSM-III-R/IV/IV-R/5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition revised (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 1987)/4th edition (APA, 1994)/4th edition revised (APA, 2000)/5th edition revised (APA, 2013); ICD-9/10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 9th revision (World Health Organization (WHO), 1978)/10th revision (WHO, 1992); ICPC-2: International Classification of Primary Care, 2nd edition (WHO, 2003); MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination (Folstein et al., Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh1975); NINCDS-ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (McKhann et al., Reference McKhann, Drachman, Folstein, Katzman, Price and Stadlan1984). Dementia terms: AD: Alzheimer's disease; FTD: Frontotemporal Dementia; LBD: Lewy Body Dementia; PPA: Primary Progressive Aphasia; PwD: people with dementia; VD: Vascular Dementia. Depression measures: BDI-I/short form/II/Spanish version/Chilean version: Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock and Erbaugh1961)/short-form (Beck and Beck, Reference Beck and Beck1972)/second edition (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer, Ball and Ranieri1996)/Spanish version (Conde and Useros, Reference Conde and Useros1975)/Chilean version; CES-D/-10/modified version: Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977)/10-item (Andresen et al., Reference Andresen, Malmgren, Carter and Patrick1994)/modified version (Hays et al., Reference Hays, Blazer and Gold1993); DSQ: Depression Screening Questionnaire (Wittchen et al., Reference Wittchen, Höfler and Meister2001); GADS: Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Scale (Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Bridges, Duncan-Jones and Grayson1988); GDS/15-item: Geriatric Depression Scale (Yesavage et al., Reference Yesavage, Brink, Rose, Lum, Huang, Adey and Leirer1983)/15-item (Yesavage and Sheikh, Reference Yesavage and Sheikh1986); HADS original/Chinese version: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond and Snaith, Reference Zigmond and Snaith1983)/Chinese version (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Leung, Fong, Leung and Lee2010); HRSD/Spanish version: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1980)/Spanish version (Ramos-Brieva, Reference Ramos-Brieva1986); MADRS: Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (Montgomery and Asberg, Reference Montgomery and Asberg1979); PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001); OAHMQ: The Older Adult Health and Mood Questionnaire (Kemp and Adams, Reference Kemp and Adams1995); SCID-I: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams, Rush, First and Blacker2008); RDC: Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer and Robins, Reference Spitzer and Robins1978). Burden measures: ZBI 22-item/Spanish version/Chilean version: Zarit Burden Interview (Zarit et al., Reference Zarit, Reever and Back-Peterson1980)/Spanish version (Martín et al., Reference Martín, Salvadór, Nadal, Miji, Rico, Lanz and Taussig1996)/Chilean version (Breinbauer et al., Reference Breinbauer, Vásquez, Mayanz, Guerra and Millán2009); CBI: Caregiver Burden Inventory (Novak and Guest, Reference Novak and Guest1989).

Of the 40 studies that reported the proportionality of genders, all were predominantly female. Thirty-three studies reported the mean age of the sample (ranging from 51.8 to 83.5 years old). Of the 40 studies that reported the percentages of relationships between the care-givers and care recipients, 20 had a majority of spouses and 20 a majority of non-spouses (typically adult children). Twenty-four studies reported the tools used to diagnose dementia or a form of dementia in all care recipients; seven used the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA; McKhann et al., Reference McKhann, Drachman, Folstein, Katzman, Price and Stadlan1984) alone or in conjunction with other diagnostic tools or procedures. Twenty-one studies reported the percentages of the care recipients' dementia diagnoses. Ten studies were 100 per cent AD, five were primarily AD followed by Vascular Dementia (VD) then other dementias, one was primarily AD followed by other dementias then VD, one was 75 per cent AD and 25 per cent Lewy Body Dementia (LBD), one was a majority of Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) followed by AD then other dementias, and one was 100 per cent FTD.

Structured diagnostic interviews were used in two of the 38 studies that reported the prevalence of depression, leaving 36 studies that used self-report depression measures (Table 3B). The 20-item CES-D (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977) with cut-off ⩾16 was used the most times (11) to measure depression. Of the nine studies that reported the prevalence of burden, eight used a version of the 22-item ZBI (Zarit et al., Reference Zarit, Reever and Back-Peterson1980).

Risk of bias within studies

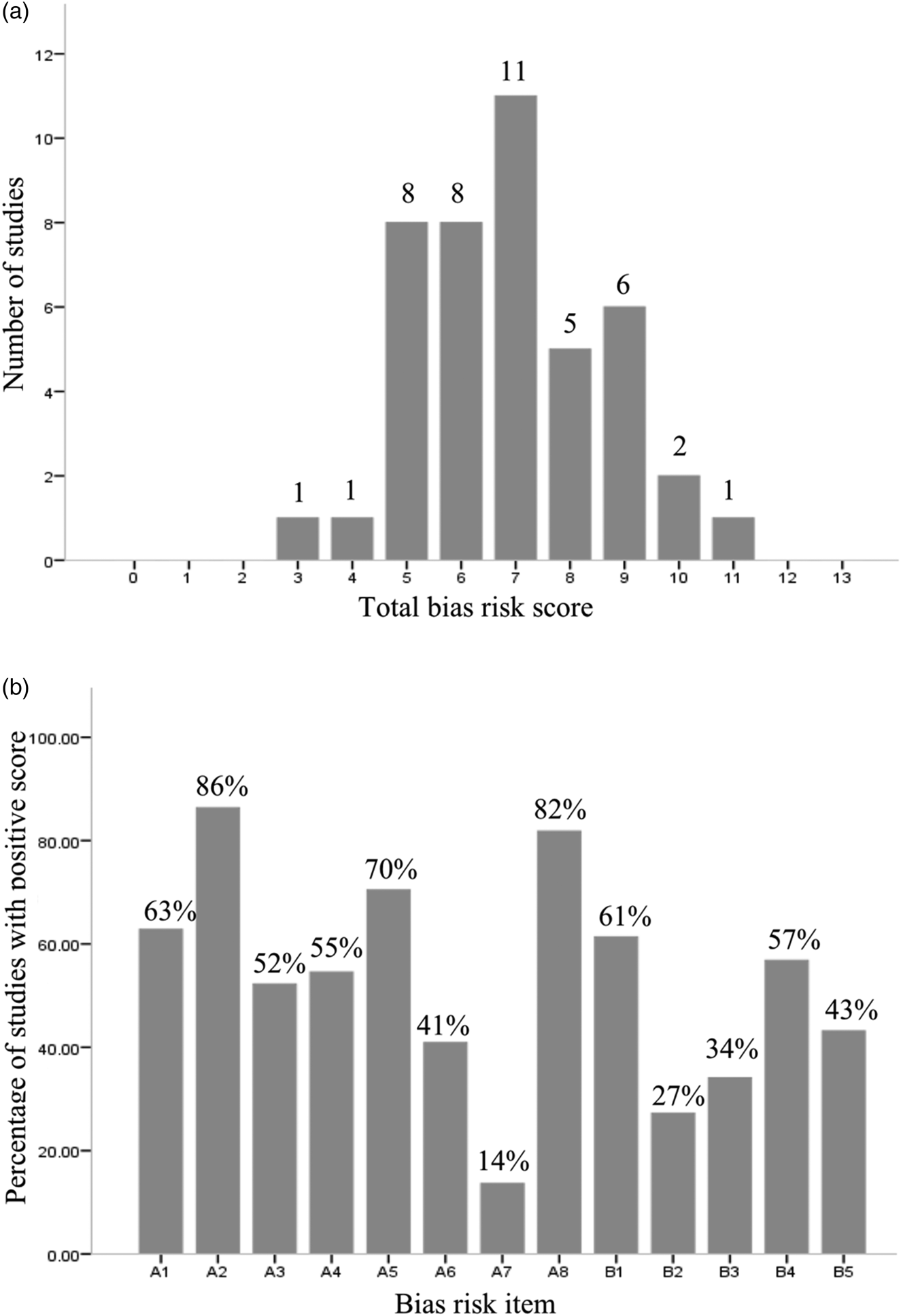

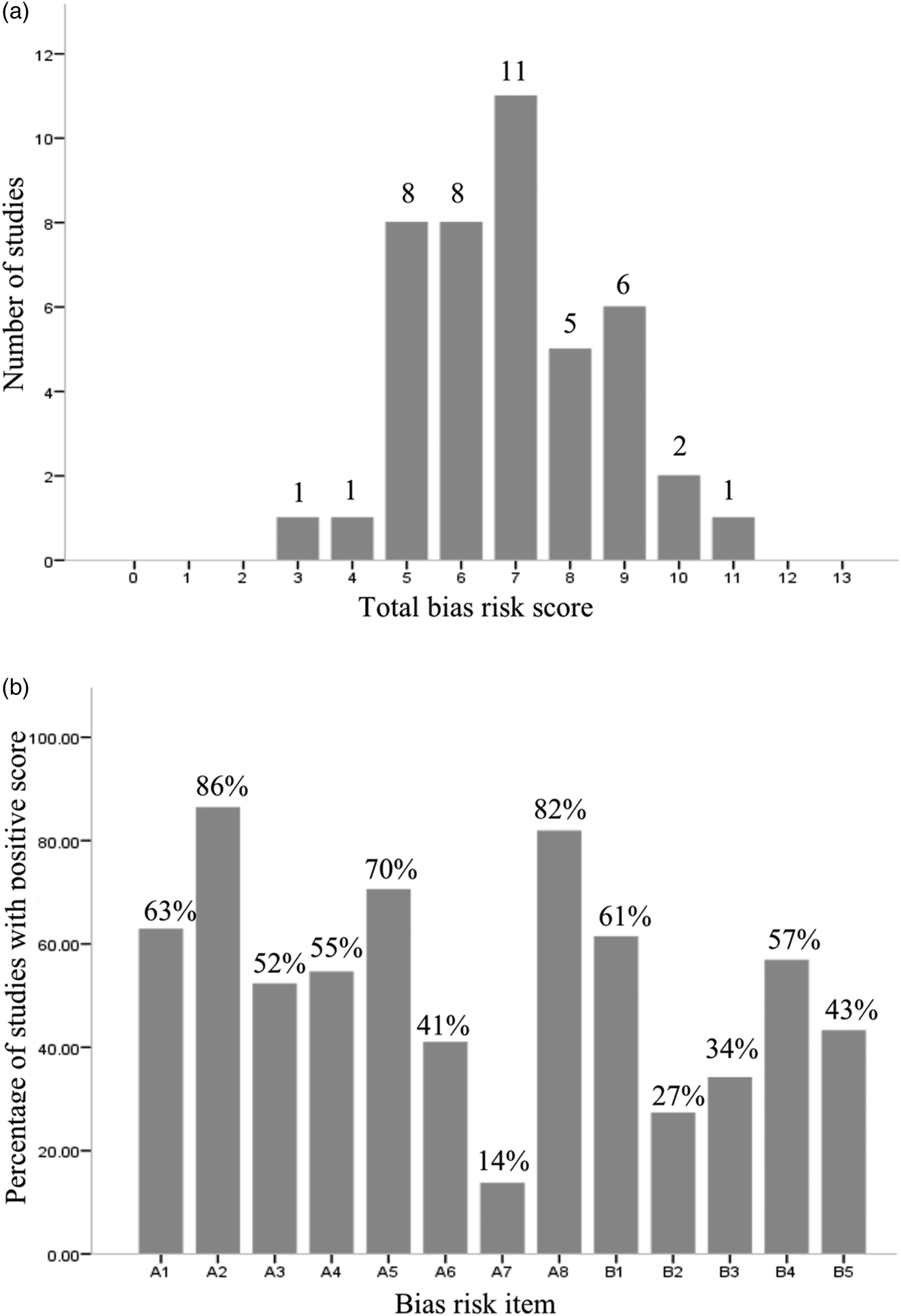

The mean bias score was seven (standard deviation = 1.65) and scores ranged from four (highest risk bias) to 11 (lowest risk) (Figure 3A). Of the 43 studies assessed, 18 had a high risk, 22 had a medium risk and three a low risk. As can be seen in Figure 3B, over 80 per cent of the studies reported the percentages of the types of relationships between care-givers and care recipients, and inclusion and exclusion criteria. More than half had a sample size ⩾100 and reported sufficient socio-demographic information, the dementia diagnostic procedure, percentages of dementia diagnoses, dementia severity and provided an adequate description of the recruitment method. The most under-reported risk items were ‘(history of) psychiatric problems’ (14%) and ‘participation and response rates are described and are more than 75 per cent (27%). See Figure 3 for a full description of the risk bias assessment results.

Figure 3. Bias risk assessment of 43 studies. (A) Number of studies per rating; (B) percentage of studies with a positive score on each risk item.

Results of individual studies

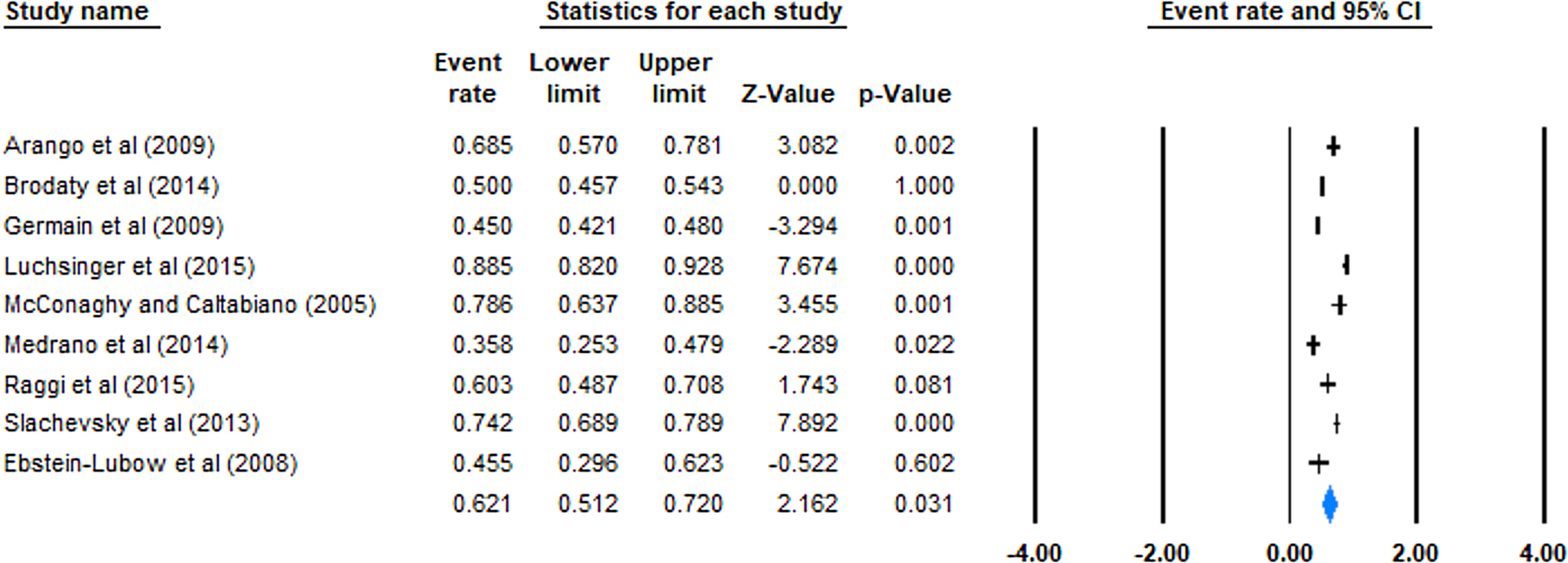

Figures 4 and 5 show forest plots of prevalence estimates for burden and depression, including their CI and associated z- and p-values.

Figure 4. Forest plot on the prevalence of depression among care-givers of people with dementia.

Figure 5. Forest plot on the prevalence of burden among care-givers of people with dementia.

Synthesis of results

Prevalence of depression

Thirty-eight studies included prevalence estimates of depression. These ranged from 3 to 57 per cent; although it must be noted that the study with a 3 per cent prevalence estimate (Lowery et al., Reference Lowery, Mynt, Aisbett, Dixon, O'Brien and Ballard2000) had the highest standard error and could be considered an outlier (Copas and Shi, Reference Copas and Shi2000). Overall, prevalence estimates of depression yielded a pooled prevalence of 33.6 per cent (95% CI = 29.9, 37.5; p < 0.001). However, the heterogeneity of the prevalence estimates was significantly high (I 2 = 93.96%; Q = 612.31; p < 0.001).

Prevalence of burden

Nine studies reported prevalence estimates of burden. These estimates ranged from 35.8 to 88.5 per cent, with a pooled prevalence of 62.5 per cent (95% CI = 51.2, 72; p = 0.031). However, heterogeneity of the prevalence estimates was significantly high (I 2 = 94.90%; Q = 157; p < 0.001).

Risk of bias across studies

Studies on depression

The depression pooled prevalence estimate corresponded to a z-value of −28.77 (p < 0.00001) indicating that 8,149 studies with a null effect size would be needed before the combined two-tailed p-value would exceed 0.05, suggesting that the observed effect estimates may be extremely robust. The trim and fill method indicated four potentially missing studies that would need to fall on the left side of the pooled prevalence estimate to make the plot symmetrical (Figure 6). Assuming a random-effects model, the new pooled prevalence estimate reduced to 31.24 per cent (95% CI = 27.70, 35.01).

Figure 6. Random effects funnel plot of logit event rate depression effect sizes by standard error.

Studies on burden

The burden pooled prevalence estimate corresponded to a z-value of 5.914 (p < 0.00001) indicating that 73 studies with a null effect would be needed before the combined two-tailed p-value would exceed 0.05, suggesting that the observed prevalence estimates may be robust. The trim and fill method indicated three potentially missing studies that would need to fall on the left side of the pooled prevalence estimate to make the plot symmetrical (Figure 7). Assuming a random-effects model, the new pooled prevalence estimate reduced to 49.26 per cent (95% CI = 37.15, 61.46).

Figure 7. Random effects funnel plot of logit event rate burden effect sizes by standard error.

Additional analyses

Sensitivity analysis

Following the omission of Epstein-Lubow et al. (Reference Epstein-Lubow, Davis, Miller and Tremont2008), the prevalence of burden increased by a minimal percentage (1.4%). The analysis found no deviations from the main analysis in terms of heterogeneity or significance of results.

Sub-group analysis

Random-effects sub-group analysis comparing RCT data to non-RCT data was not appropriate for burden outcomes, given that only one of the nine studies used baseline RCT data (Epstein-Lubow et al., Reference Epstein-Lubow, Davis, Miller and Tremont2008). The depression pooled prevalence estimate of studies that used baseline RCT data did not significantly differ from that of studies where samples were obtained via cross-sectional or longitudinal prospective cohort designs (p = 0.734). The second random-effects sub-group analysis included 32 studies and revealed that depression prevalence estimates differed according to the type of measure used (p = 0.003); two studies that used diagnostic criteria reported the lowest prevalence rate (8.9%; 95% CI = 3.4, 21.4; I 2 = 88.01%), although one of these studies may be considered an outlier, followed by studies that used a form of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; 26%; 95% CI = 15.6, 40.1; I 2 = 95.89%). Five studies that used a form of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) reported the highest prevalence estimate (49.2%; 95% CI = 34.3, 64.2; I 2 = 59.66%). As there were no studies conducted in Africa and only one study based in South America reporting depression prevalence data, the random-effects sub-group analysis for continent compared the pooled prevalence estimates of Asia, Europe, Australia and North America. There was a significant difference between the depression pooled prevalence estimates of the continents entered into the analysis (p < 0.0007), with Asia reporting the lowest estimate of 26.8 per cent (95% CI = 17.2, 39.2), followed by North America 29.1 per cent (95% CI = 24.3, 34.6), Europe 36.8 per cent (95% CI = 31.1, 42.8) and Australia yielding the highest estimate of 58.1 per cent (95% CI = 40.0, 74.3).

Meta-regression results

Study quality was not a significant moderator of depression prevalence estimates (0.0254; 95% CI = −0.0816, 0.1324; p = 0.641) or burden prevalence estimates (−0.18; 95% CI = 0.144, −0.461; p = 0.215).

Odds ratio meta-analyses

The first meta-analysis included eight studies (Figure 8) and revealed that the odds of a female care-giver having depression was 1.45 times higher than a male care-giver (95% CI = 1.125, 1.874; p = 0.004). There was no significant heterogeneity of the odds ratio estimates. The pooled odds ratio estimate corresponded to a z-value of 3.854 (p = 0.001), indicating that 23 studies with a null effect would be needed to reduce the p-value to below the significance level, suggesting that the odd ratios may not be robust. However, the trim and fill method indicated no missing studies from the analysis. The second meta-analysis included seven studies and the odds of a spouse compared to a non-spouse having depression was found to be 1.15, however this was not significant (95% CI = 0.737, 1.779; I 2 = 84.42; p = 0.547). The trim and fill method suggested there were no missing studies from this analysis.

Figure 8. Forest plot on gender of care-giver and its impact on the prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms.

Discussion

Forty-three studies set across five of the seven continents, predominantly comprising cross-sectional designs, were examined with a combined total of 16,911 participants. To our knowledge, this was the first meta-analysis to quantify the prevalence of perceived burden among informal care-givers of PwD. Overall, the trim-and-fill adjusted prevalence estimate of burden was 49.26 per cent. In other words, approximately half of all the informal care-givers of PwD perceive their care-giving role to be mildly to severely burdening. This result was indicated to be robust in the context of publication bias. There may be numerous reasons for why the remaining half of the population perceives their role to have little or no burden, including that these care-givers perceive more positive benefits from the acquisition of the role. For example, if a care-giver perceives that their family has become closer together, this could impact upon their response to questions regarding the social impact of the role – a construct of burden. Importantly, the finding highlights a great need within this population for interventions effective at reducing burden. Such interventions could increase the wellbeing of care-givers during their role, which could prolong the transition of care recipients to care homes, and prevent post-death psychiatric morbidity (Gaugler et al., Reference Gaugler, Kane, Kane and Newcomer2005).

The trim-and-fill adjusted prevalence estimate of depression was 31.24 per cent, suggesting that almost a third of all care-givers of PwD are experiencing depression. Rosenthal's fail-safe N indicated that this finding was extremely robust, with over 8,000 extra studies with a null effect required to nullify the result. The depression prevalence estimate is substantially higher than that of the prevalence of depression among adult primary care patients, assessed via structured diagnostic interviews (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Vaze and Rao2009), and the prevalence of depression in older adult populations, assessed via self-report measures (Luppa et al., Reference Luppa, Sikorski, Luck, Ehreke, Konnopka, Wiese, Weyerer, König and Riedel-Heller2012; Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Shao, Qi and Tian2014). Given that depression has been found to be a risk factor for suicidal ideation among family care-givers of PwD, the high prevalence of depression supports the finding of higher prevalence rates of suicidal ideation in this population compared to the general population (O'Dwyer et al., Reference O'Dwyer, Moyle, Zimmer-Gembeck and De Leo2013, Reference O'Dwyer, Moyle, Zimmer-Gembeck and De Leo2016). Overall, the finding demonstrates that more informal care-givers of PwD are in need of interventions to reduce depressive symptoms than the adult/older adult general population.

Interestingly, the depression prevalence estimate is higher than that found in the study of Cuijpers (Reference Cuijpers2005). This could be attributed to the fact that all of the studies within Cuijpers (Reference Cuijpers2005) were conducted at least 12 years ago and therefore its estimate may not reflect the current prevalence in today's population. The difference could also be due to the fact that all studies in Cuijpers (Reference Cuijpers2005) were based in either the UK or the United States of America, unlike the current review which included depression prevalence estimates from studies conducted in numerous countries across Europe, multiple states in North America, and several places in Asia and Australia. In addition to this, the current review included almost four times as many studies and so may have provided a more accurate prevalence estimate. Finally, the review of Cuijpers (Reference Cuijpers2005) only included studies that assessed depression via semi-structured or structured diagnostic interviews, whereas the current meta-analysis also included studies that assessed depression via self-report measures. It has been reported that, compared with self-report measures, interview methods commonly underestimate the prevalence of psychiatric disorders (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Chan, Bhatti, Halton, Grassi, Johansen and Meader2011). In line with this and the findings of other meta-analytic reviews (e.g. Krebber et al., Reference Krebber, Buffart, Kleijn, Riepma, Bree, Leemans, Becker, Brug, Straten, Cuijpers and Verdonck-de Leeuw2014), the current review discovered that the depression prevalence estimates differed according to the instrument used to assess depression, with interviews based on diagnostic criteria yielding the lowest pooled prevalence estimate. This could also explain why the overall depression prevalence estimate was similar to that found in Sallim et al. (Reference Sallim, Sayampanathan, Cuttilan and Ho2015), where studies assessing depression via self-report measures were included.

The review also found that female care-givers are 1.45 times more likely to experience depression than male care-givers. Although, this finding may not be robust in the context of publication bias, and further observational studies comparing the prevalence of depression between male and female care-givers of PwD are warranted. No significant difference in terms of depression prevalence was observed between spousal and non-spousal care-givers; indicating that care-givers who are adult children, friends or other relatives of the care recipient may be just as much at risk of developing depression as care-givers who are spouses of the care recipient. This outcome did not support the finding of Sallim et al. (Reference Sallim, Sayampanathan, Cuttilan and Ho2015), where spousal care-givers of patients with AD were significantly more likely than non-spousal care-givers of patients with AD to experience depression. It is not thought that this is attributed to the fact that the current review included care-givers of people with all forms of dementia, but because it included over twice as many studies – three of which reported a higher prevalence of depression in non-spousal compared to spousal care-givers. Some research has indicated that it may not be the type of relationship that poses a risk for depression but the care-giver's perception of the quality of the relationship. For example, Kramer (Reference Kramer1993), Williamson and Schulz (Reference Williamson and Schulz1993) and Fauth et al. (Reference Fauth, Hess, Piercy, Norton, Corcoran, Rabins, Lyketsos and Tschanz2012) found closer relationships prior to the onset of dementia predicted lower levels of depressive symptoms. Furthermore, Morris et al. (Reference Morris, Morris and Britton1998) found care-givers with lower levels of intimacy prior to and following the onset of dementia had higher levels of depressive symptoms.

Limitations

Although study quality was not found to be a significant moderator of the burden or depression prevalence estimates, 18 studies were rated as having a high risk of bias and only three studies were rated as having a low risk of bias. The majority of studies failed to report any details of the history of psychiatric problems for the informal care-givers. Most did not report details of the participation and response rates or when these were reported they were less than 75 per cent, and most studies did not compare those that did respond/participate to those that did not (either qualitatively or quantitatively). This could mean that within these studies a large proportion of care-givers did not respond/participate. If this were true, this could have affected the accuracy of the burden prevalence estimate, particularly given that one of the reasons some informal care-givers of PwD do not engage with services is due to a high level of burden (Brodaty et al., Reference Brodaty, Thomson, Thompson and Fine2005).

Another limitation of the review, and a major limitation of this field of research, is that most studies used convenience-based samples rather than population-based samples. Pruchno et al. (Reference Pruchno, Brill, Shands, Gordon, Genderson, Rose and Cartwright2008) discovered that care-givers recruited via convenience sampling methods reported higher levels of burden and increased depressive symptomatology relative to those identified using a population-based sampling method. This is therefore a serious methodological concern in that convenience samples are likely to exaggerate the prevalence of depression and burden considerably and therefore the findings may not be reliably generalisable (Pruchno et al., Reference Pruchno, Brill, Shands, Gordon, Genderson, Rose and Cartwright2008). Future research should endeavour to recruit a consecutive sample of the population.

Another limitation is the findings of significantly high heterogeneity of depression and burden prevalence estimates. This suggests that these are not similar across studies and conclusions drawn are limited by this fact. Interestingly, the purpose of recruitment did not appear to impact the prevalence estimates as the pooled prevalence of studies that used baseline RCT data did not significantly differ from that obtained for studies using cross-sectional designs and longitudinal prospective cohort designs. The heterogeneity among depression prevalence estimates was, however, partially explained by the type of instruments used to measure depression, with studies using diagnostic criteria yielding the lowest pooled prevalence estimates. In terms of self-report measures, studies that used a form of the HADS yielded the lowest pooled prevalence estimates and studies using a form of the BDI had the highest pooled prevalence estimates. These findings reflect those of a recent meta-analysis of the prevalence of depression among medical outpatients (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wu, Lai, Long, Zhang, Li, Zhu, Chen, Zhong, Liu and Wang2017). The self-report measures are designed to assess clinically significant depressive symptoms but they are not tools for diagnosing different types of mood disorders, e.g. the HADS does not include all of the diagnostic criteria for depression based on the DSM (Laidlaw, Reference Laidlaw2015). It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that the two studies that used diagnostic criteria reported the lowest prevalence rates. Moreover, the HADS was designed to detect depression and anxiety in people with medical conditions, and thus it is useful for older people with chronic physical illnesses. Although the BDI is a well-established measure, it can be criticised for having somatic scale items as this may inflate scores when used with older people (Laidlaw, Reference Laidlaw2015). Considering that many informal care-givers of PwD are older people, this may account for the significantly large difference observed between the pooled prevalence estimates of studies that used the HADS and the BDI. It is also acknowledged that different cut-offs may have affected the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity.

The study also revealed that prevalence estimates differed by continent. Asia appeared to have the lowest prevalence of depression, followed by North America, Europe and Australia, respectively. Unfortunately, the review could not include South America within the sub-group analysis as only one study conducted in this region reported the prevalence of depression, and overall no included study was conducted in Africa. This leaves a question as to whether the prevalence of depression among informal care-givers of PwD differs greatly in these continents.

Conclusion

In summary, this review revealed that almost one-third of informal care-givers of PwD experience depression and approximately one-half appraise their care-giving role to be burdensome. Unfortunately, significant heterogeneity of depression and burden prevalence estimates was observed. As reported in other reviews, different screening instruments were found to produce different estimates of depression. The heterogeneity of depression prevalence estimates was also partially explained by the continent on which the studies were conducted, with Asia reporting the lowest prevalence and Australia the highest. Female care-givers were found to be more at risk of experiencing depression than male care-givers. However, further observational studies investigating this finding are warranted. No significant difference in terms of depression prevalence was observed between spousal and non-spousal care-givers. Based on previous literature, it is suggested that a care-giver's vulnerability to developing depression may be more related to the quality of the relationship with the care recipient as opposed to the relationship type. The review demonstrates that within this population there is a great need for the provision of interventions that are effective at reducing burden and depressive symptoms. Given that these difficulties can negatively impact upon a care-giver's health, ability to perform their role (Gallagher et al., Reference Gallagher, Rose, Rivera, Lovett and Thompson1989; Cucciare et al., Reference Cucciare, Gray, Azar, Jimenez and Gallagher-Thompson2010) and increase the likelihood of the care recipient being transitioned to a nursing home placement (Gaugler et al., Reference Gaugler, Kane, Kane and Newcomer2005), economically, it would appear vital for dementia services to establish or tailor existing interventions promptly to treat these difficulties.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X19000527

Author contributions

The first author designed the study, collected the data, analysed the title, abstracts and all full texts, conducted statistical analyses, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. The second author contributed to analysing full-text articles and assessing eligibility, extracting the data and analysing the quality of selected studies, and editing and proof reading the manuscript. Both authors have approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Clinical Psychology Course at the University of East Anglia (UEA), which provided financial support for the CMA software. The authors work within the institution, however, no other UEA personnel were involved in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.