Introduction

In 2010, a political scandal raged in Denmark. A politically appointed ministerial adviser was alleged to have asked a civil servant to delete an incriminating email as part of a cover-up. The email was relevant to an ongoing public debate on public overpayment for services provided by private hospitals. The civil servant did not comply but went to his superior, who supported him. Someone then leaked the information about the cover-up attempt to the press, probably a civil servant who found the request alarming (Frederiksen and Nielsen Reference Frederiksen and Nielsen2010).

Leaking information to outsiders is risky and unusual, however. Civil servants are therefore likely to consider other options first, such as voicing their concerns internally to colleagues or superiors, or staying silent and loyally obeying orders (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970; Kingston Reference Kingston2002; Niemann Reference Niklasson2013, 193). They may even start neglecting their duties, or sabotaging the work of the organisation in secret, whereas others may prefer to leave the organisation entirely (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970; Golden Reference Golden1992; Dowding et al. Reference Dowding, Mergoupis and van Vugt2000).

Most studies focus on these responses as reactions to civil servants’ working conditions, e.g. dissatisfaction with salaries, benefits, training, promotion and physical work environment (Whitford and Lee Reference Williams2014). This research largely replicates findings from the private sector and ignores the nature of public employment (John Reference John2017). For instance, public employees may be more motivated by a will to serve the public good than private employees. We have little knowledge of civil servants’ preferred responses to the kind of situation described in the Danish case above. When government organisations move in the “wrong direction” (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970, 78) or make what bureaucrats perceive to be poor or even harmful policy decisions, what do civil servants do? Do they look away and carry on as usual, or do they stand up to their political principals?

This article sheds light on what factors influence civil servants’ behaviour in these situations. Our interest is the study of voice in politically steered organisations, or more precisely in ministries. Since ministries can employ merit-recruited and tenured civil servants as well as politically recruited advisers (here referred to as political advisers), we compare how these groups respond in two systems that are politicised in different ways.

We speak of two forms of politicisation depending on how ministerial employees are hired and what tasks they perform. Politicisation by recruitment (Hustedt and Salomonsen Reference Hustedt and Salomonsen2014) is the “substitution of political criteria for merit-based criteria in the selection, retention, promotion, rewards and disciplining of members for the public service” (Peters and Pierre Reference Peters2004, 2). This kind of politicisation has received much attention from researchers. There are studies of the extent to which the recruitment of different public administrations is politicised (e.g. Peters and Pierre Reference Peters2004; Lewis Reference Lewis2008; Dahlström Reference Dahlström2009; Rouban Reference Rourke2012) and how increasing politicisation affects the role perception and prominence of the permanent civil service (e.g. Eichbaum and Shaw Reference Eichbaum and Shaw2007; Reference Eichbaum and Shaw2008; Mulgan Reference Niemann2007; Rouban Reference Rourke2012). No one has examined how such a change might affect the expression of critical voices in the policy process, however.

Functional politicisation refers to the kinds of tasks the civil service performs. Political-tactical tasks include delivering political advice, having contacts with parliamentarians, interest groups, and the media; less political tasks – policy tasks – include documenting, analysing, writing draft law and implementing decisions. This dichotomy has proven useful as an analytical construct (cf. Goetz Reference Goetz1997; Overeem Reference Peters and Pierre2005; Hustedt and Salomonsen Reference Hustedt and Salomonsen2014).

Our article examines how different types of politicisation affect civil servants’ propensity to voice their concerns when they perceive a policy to be harmful. Such responses may affect the degree of critical policy scrutiny in, and thereby the quality of, the policy process (Flynn Reference Flynn2006).

The contribution of this study is twofold: First, it adds important knowledge to the research on the politicisation of the civil service by studying how politicisation may affect voice in policy processes. Second, it speaks to the literature on how and when employees express voice by studying the inclination to speak up in (1) a group that has not been studied in this field of research previously, namely political advisers and (2) civil servants who react to something that is harmful to the country rather than to themselves.

We start out by summarising the debate regarding civil servants’ duties and rights. We discuss how they might respond to perceived harmful proposals and why different actors are likely to respond in certain ways. Based on this discussion, we formulate three hypotheses. We present design and data and move on to the empirical analysis and conclusion.

The responsibility of civil servants

Should civil servants do anything at all that might influence policies? According to the Weberian ideal, public administrators should be neutral and loyal to their political principals (Weber Reference Whitford and Lee1946). A civil servant should implement political decisions “exactly as if the order agreed with his own conviction” (Weber quoted in Lewin Reference Lewin2007, 132). Voicing concerns regarding perceived poor political decisions to outsiders, or in other ways impeding their realisation is unthinkable (Overeem Reference Peters and Pierre2005).

This implies that civil servants cannot be held responsible for negative effects that may follow from these decisions. Responsibility and the line of authority are hierarchical, the idea being that this structure makes it possible to hold those in charge accountable. Democratically elected politicians should make the decisions and take the blame or the credit. Civil servants cannot be held accountable by the people and should not attempt to represent them (Wilson Reference Öhberg and Naurin1887; Christensen Reference Christensen2011). In sum, politicians make decisions, civil servants follow order.

This image has been questioned empirically as well as normatively (de Graaf Reference de Graaf2010). Empirically, researchers have pointed out that this division of labour is impossible given civil servants’ professional expertise, long tenure and central position in the decisionmaking and implementation processes (Kaufman Reference Kaufman1960; Rourke Reference Rusbult and Lowery1992; Bovens Reference Bovens2007). Politicians would be unwise not to take the advice of this knowledgeable group, especially since political issues are becoming increasingly complex (Dahl Reference Dahl1989).

Normatively, civil servants who simply function as marionettes have also been questioned, since they may carry out all sorts of atrocities, as during WWII (Arendt Reference Arendt1994). Ingraham and Colby (Reference Ingraham and Colby1982, 304) recommend a balance between a neutrally competent and a politically responsive bureaucracy: “Though one [value] or the other may be ascendant or dominant, it does not attain its preferred status by completely eliminating the others.” Many scholars stress that the responsibility of civil servants is not just to follow orders, but also to serve the public good and other values such as efficiency and effectiveness (Bovens et al. Reference Bovens, Geveke and Vries1995; Denhardt and Denhardt Reference Denhardt and Denhardt2000; Bovens Reference Bovens2007). Some even claim that it would be detrimental to the political process and its outcomes if civil servants did not speak up in order to reveal low quality, low productivity, fraud, mismanagement, illegal activities or other types of problematic administration (Bovens et al. Reference Bovens, Geveke and Vries1995).

There are thus good reasons to argue both that civil servants, in rare cases, should defend the public interest and that their primary duty is to remain loyal to their political masters – even in the face of disaster. The question is how civil servants say they will react.

Different ways to respond

Three possible responses, famously introduced by Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1970), are exit, voice and loyalty. Given our focus on how different forms of politicisation affect civil servants’ propensities to raise voice against perceived harmful policies, we exclude exit from the discussion. Thus, we do not test the full range of Hirschman’s framework. This allows us to dig deeper into different voice options. Studies of exit tend to leave voice out, presumably for the same reason (see overview in Whitford and Lee Reference Williams2014). Furthermore, our purpose is not a broad account of civil servants’ responses, but to study when civil servants and political advisers speak up in different contexts.

Voice can be defined as an “attempt … to change … an objectionable state of affairs” (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970, 30) often by appealing to a higher authority (vertical voice) inside or outside the organisation (Farrell Reference Farrell1983; Dowding and John Reference Dowding and John2012, 43). Employees use vertical internal voice when they take their concerns directly to their administrative superiors or to the political leadership, face-to-face or in writing. Horizontal internal voice implies that employees discuss their concerns among themselves (Dowding and John Reference Dowding and John2012, 43-44).

External voice can also be expressed horizontally or vertically. It may entail complaining about policy proposals to colleagues or superiors in other departments or leaking information to the press. Most scholars describe leaking as a release of confidential or nonofficial information about an organisation to an outsider. Critical employees who are prepared to take this step can thus “bring honesty into the system” (Flynn Reference Flynn2006, 260). However, leaking is a radical reaction that few employees are expected to engage in; the potential cost for the individual is high.

Loyalty was originally introduced by Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1970, 38, 77-78) as a psychological condition that affects the cost-benefit calculation concerning exit and voice. In empirical studies, the concept has been used to capture passive responses of employees whose organisational commitment restrains them from criticising it openly. Their trust causes them to believe in the organisation’s goals or silently hope that the organisation will come around by itself (Rusbult and Lowery 1985; Golden Reference Golden1992).

Other silent and resistant responses are sabotage and neglect (Rusbult and Lowery 1985; Dowding et al. Reference Dowding, Mergoupis and van Vugt2000). It is a well-known phenomenon that public policies are not always developed and implemented in the way politicians expect (e.g. Cook Reference Cook1988), due to apathy and lack of enthusiasm (neglect), or silent resistance among professionals through foot dragging or deliberate slowdown of agency activities (sabotage) (Golden Reference Golden1992).

In sum, ministerial advisers may react to perceived harmful policy proposals in different ways. This article focuses on the extent to which civil servants and political advisers are inclined to use different voice options. We also compare their preferences for these options to their propensity to stay silent – whether out of loyalty or in order to silently resist the proposal.

Responses by different actors

(H1) Our first hypothesis is that political advisers are more likely to use internal voice options than civil servants: This prediction is based on (1) the different employment arrangements that apply to these two groups and (2) their access to the political leadership.

For a start, political advisers’ employment is formally connected with the government’s electoral success; if the government goes, so do the political advisers. Political advisers thus share the government’s need to maximise support for its policies. Poor policies that might make the government lose the next election are not in political advisers’ interests. Consequently, they are expected to voice concerns against bad policies.

Senior civil servants are also expected to indicate their opinion on policy alternatives (Peters Reference Pfiffner1987; Niemann Reference Niklasson2013, 244) and to object when they believe that their minister’s preference is detrimental. However, if the political principals stick to their original position, civil servants are supposed to step back. It is not their job to take political fights (Niemann Reference Niklasson2013, 181-191), and we therefore hypothesise that they score lower on internal voice than political advisers.

It is reasonable to assume that political advisers have fairly easy access to their minister, allowing them to raise their concerns. Several studies have shown that they indeed have their minister’s ear (e.g. Aucoin Reference Aucoin2010; Eichbaum and Shaw Reference Eichbaum and Shaw2010). Some civil servants also have direct access to the minister, but most do not and the growing number of political advisers may render it more difficult for civil servants to make their voices heard in the policy process. This is true, first, because political advisers sometimes act as gatekeepers to the ministers (Eichbaum and Shaw Reference Eichbaum and Shaw2008). Second, because objections from civil servants may carry less weight when the minister is surrounded by supportive political advisers who urge her to continue in the politically preferred direction. Knowing this is likely to make civil servants refrain from voicing concerns; it can prove costly for the individual civil servant and have little effect on the intended policy. Leaving the organisation may become more attractive (Bertelli and Lewis Reference Bertelli and Lewis2013; Niemann Reference Niklasson2013, 193).

However, there are also other response options available to civil servants.

(H2) Our second hypothesis is that civil servants are more likely to express external voice than political advisers: We base this hypothesis on the important difference between civil servants and political advisers in terms of loyalty. Civil servants are employed by the state and their personal careers are independent of the fate of the incumbent government. Even if they need to be loyal to the government of the day, they are in a position to provide professional and frank-and-fearless advice (Eichbaum and Shaw Reference Eichbaum and Shaw2007) and to speak up against what they perceive to be problematic projects. In Aberbach and Rockman’s (Reference Aberbach and Rockman1994, 461) wording, a nonpoliticised civil servant is [a neutral] competent official] with an eye to the long-term interests and the institutional health of the government.” If these interests are threatened, civil servants may feel obliged by their professional and ethical codes to voice their concerns, primarily internally within the organisation, but if this has no effect, they may reach out and leak information to the public.

Political advisers are employed by, and are loyal to, the government or the minister and may therefore be less inclined to act against the government’s interests (Kingston Reference Kingston2002; Dahlström et al. Reference Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell2012). If political advisers are not heard when expressing internal voice, they may be expected to stay loyal, or exit, rather than voice their concerns publicly and possibly harm the government.

Hypotheses 1 and 2 address the possible consequences of politicisation by recruitment. The third hypothesis focuses on the possible effects of a functionally politicised advisory system, where top civil servants participate in the political-tactical aspects of their minister’s work. Being deeply involved in the development of policies, they have a solid understanding of the substantial, political and tactical considerations behind the minister’s policies. They must be neutral in the sense that they serve all governments alike, but their loyalty to the government of the day must be beyond doubt. Consequently, they may relax some of the technical and professional aspects of their work. Research has shown that civil servants in such systems put less emphasis on critically assessing the government’s policy proposals and presenting alternative options. They do also not strive to provide independent, honest and upright advice to the same extent as other civil servants (Christiansen et al Reference Christiansen, Niklasson and Öhberg2016).

(H3) Our third hypothesis is therefore that civil servants in functionally politicised systems are more silent. They are less likely to use voice and more likely to opt for loyalty or silent resistance than civil servants in less functionally politicised systems: These kinds of responses avoid open conflict with the political leadership, but some of them still enable employees to influence policies.

A comparative approach

In order to test the effect of politicised recruitment on bureaucratic response (Hypotheses H1 and H2), we compare civil servants and political advisers in Sweden. Approximately 200 of the 4,600 employees at the Swedish Government Offices are political advisers, which means that ministers are allowed eight of them on average (e.g. state secretaries, policy experts and press secretaries).Footnote 1 Only the state secretaries are part of the ministerial hierarchy, however. The others have no formal authority over merit-recruited civil servants (Ullström Reference Vantilborgh2011).

In an international perspective, this level of politicised recruitment is not striking; e.g. the ministries in the USA, Australia and France score much higher (Dahlström Reference Dahlström2009). Still, the number of political advisers in Sweden is large enough to allow us to examine how this group responds to perceived harmful policies compared to civil servants in the same system.

The hypothesis regarding functional politicisation (Hypothesis H3) is tested in a comparison of civil servants in Denmark and Sweden. These countries can be classified as managerial bureaucracies (Dahlström and Lapuente Reference Dahlström and Lapuente2017, 64). They are both unitary states, have decentralised public service sectors, belong to the Nordic group of universal welfare states, are parliamentary systems, have strong unions and a corporatist heritage. They have proportional, multi-party systems and are typically governed by minority coalitions. Finally, the two countries have comparatively efficient bureaucracies, their corruption levels are among the lowest in the world (Transparency International Reference Ullström2015), the civil services have similar educational backgrounds, and they apply similar ethical codes (DJØF 1993; Värdegrundsdelegationen Reference Weber2014).

The countries have drifted apart in one respect since the 1960s though, namely in the way they politicise ministerial advice. Denmark is often portrayed as being close to the Weberian ideal (Christensen Reference Christensen2006; Reference Christensen2011). This is true as regards politicised recruitment. An intra-Danish comparison of civil servants and political advisers is therefore difficult, since each minister is only allowed one political adviser (party leaders two) (Government of Denmark 2013). The most important ministerial advisers in Denmark are the permanent heads of the ministries (state secretaries) and other top civil servants. These are all recruited on formal, professional merits.

However, Denmark is significantly more functionally politicised than Sweden. Research has shown that Danish civil servants more often provide political-tactical advice on how their minister’s policies can be promoted in the minister’s party, in the government, and in parliament compared to their Swedish counterparts (Christiansen et al. Reference Christiansen, Niklasson and Öhberg2016). In sum, a comparison between Denmark and Sweden constitutes a suitable – although not perfect – Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD) for studying the hypothesis regarding how functional politicisation affects the willingness of civil servants to express voice; the two countries are similar in most respects, but their organisation of ministerial advice differs significantly.

Data

Two web surveys were conducted in 2012. Before the questionnaire was finalised, questions and formulations were discussed with eight former ministers, civil servants and political advisers in both countries. In the Danish case, the Prime Minister’s permanent state secretary endorsed the survey, which probably contributed to the striking differences in response rates (see below).

The surveys included questions on how respondents would react to perceived harmful policy proposals. In Sweden, the survey was sent to 1,635 civil servants (response rate 49%) and 111 political advisers working at the ministries (response rate 38%). In Denmark, the questionnaire was administered to 383 civil servants in leading positions (response rate 78%) and to 31 political advisers (response rate 80%). To ensure comparison of equal units, only responses from civil servants in leading positions are used in the country comparisons. In Denmark, this group consists of 282 respondents employed in various departments (permanent state secretaries and agency directors are excluded), corresponding to a response rate of 76%. The Swedish group of civil servants in leading positions (directors general of ministerial work, assistant undersecretaries, division leaders, experts and ambassadors placed in the ministries) includes 393 individuals, corresponding to a response rate of 47%.

At the time of the survey, Denmark had a centre-left government consisting of the Social Liberal Party, the Social Democrats, and the Socialist People’s Party, whereas Sweden had a centre-right government consisting of the Moderate Party, the Centre Party, the Liberal People’s Party and the Christian Democrats. Both were minority governments. We cannot rule out that the different kinds of governments may affect the way civil servants react to perceived harmful decisions. However, the civil services in both countries are stable institutions with rather strong professional norms. We believe these norms outweigh the political sympathy individual civil servants may have for the government. In fact, we have some empirical evidence in favour of this point: In the Swedish questionnaire, we ask for the respondents’ political positions. When we include this variable in the comparison between political advisers and civil servants (Table 1), our main results remain unaffected.

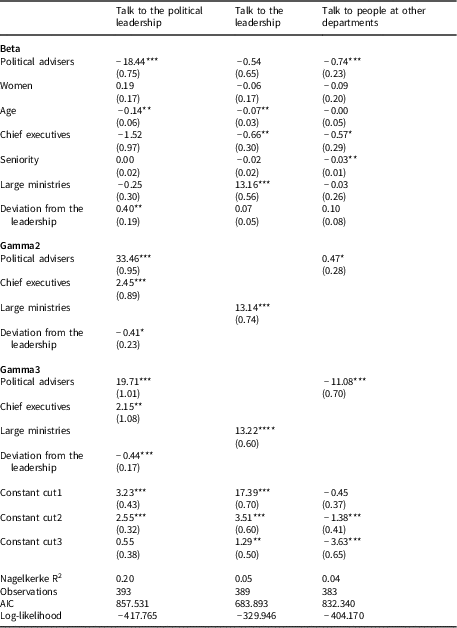

Table 1 Swedish civil servants’ and political advisers’ propensities to express internal and external voice (generalised ordered logit model)

Note: The dependent variables run between: “Not likely at all”=1, “Not very likely” =2, “Fairly likely” =3 and “Very likely”=4. The respondents are clustered to their ministries. Robust standard errors in parentheses ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1. The Gamma2 parameter shows the effect of the explanatory variable on the probability of a response to the outcome variable higher than “Not very likely”. Gamma3 does the same for responses higher than “Fairly likely”.

Measures

In order to capture the propensity to voice, we use six dependent variables, which are items of the same question: “If the government were to push for a policy within your field of responsibility that is in accordance with the law but that you believe would harm the country severely, how likely is it that you would act in the following way?”

The limitation to policies that are in accordance with the law implies that the respondents are under no clear obligation to do anything, which might have been the case if the policy were illegal. We have chosen this phrasing because it presents more of a conundrum; the respondents have to base their answers on their perceptions of their moral obligations rather than on legal requirements.

The first of the six dependent variables captures loyalty, i.e. obeying without voicing or acting in any way: “Not express my doubts, but loyally work for the passage of the policy.” The second dependent variable aims at silent resistance: “Not express my doubts, but in my daily activities try to work for a policy change in the long run.” Since we do not ask how the respondent would work for such a change, we cannot say whether this item captures neglect, sabotage, or some other silent strategy. It differs from loyalty, however, as it does not signal the same docility towards the leadership, but a silent persistence aimed at changing the unwanted decision. The third and fourth dependent variables tap internal voice. These voice options represent an employee who raises concern to the management and/or the political leadership: “Express my concern internally, via my superior,” or “Express my concern internally, in direct interactions with the political leadership in my department.” Finally, the fifth and sixth dependent variables tap external voice: “Express my doubts externally in conversations with people from other ministries” and “Express my doubts externally through the media without informing the political leadership.” The answer categories were: “Not likely at all,” “Not very likely,” “Fairly likely,” “Very likely” and “Don’t know,” which is coded as “missing” in the analyses (5% chose that option for all questions).

Our approach assumes that the respondents answer truthfully about how they would act when facing perceived harmful policy proposals. We may overestimate internal voice, since this response may be thought of as courageous and upright, whereas external voice and silent resistance may be underestimated, as they may be perceived as disloyal and sneaky (Niemann Reference Niklasson2013, 193). We have tried to mitigate this effect by formulating the response options as neutrally as possible.

Methods

We use a generalised ordered logit model, gologit2 (a user written program for Stata) with gamma parameterisation (Williams Reference Wilson2006), because the assumptions for an ordered logit model are not present. The generalised ordered model relaxes the assumption that the independent variables have an even impact across all answer categories of the dependent variables.

The generalised ordered logit model with gamma parameterisation shows Beta coefficients for all independent variables. Additional variables will be shown in the model if they violate the proportional assumption. They are reported as Gamma coefficients and they show for each category on the dependent variable for which an independent variable deviates from the proportionality assumption. The generalised ordered logit model estimates a series of binary logistics regressions where the dependent variable is combined in different categories. A Gamma coefficient=0, means that the independent variable meets the proportional odds assumption and will not be shown in the table. Coefficients>0 imply that higher levels of the independent variable are correlated with higher levels of the dependent variable (Williams Reference Wilson2006). Consequently, coefficients<0 mean that higher levels of the independent variable are correlated with lower, or the same levels of the dependent variable. Both outcomes are reported.

The model can be described in the following way (e.g. Long Reference Long1997):

In a partial model, the

![]() ${\rm \rbeta }$

can vary. In the formula above, the β1’s coefficients do not violate the assumption and are in turn associated with a subset

${\rm \rbeta }$

can vary. In the formula above, the β1’s coefficients do not violate the assumption and are in turn associated with a subset

![]() ${\rm X}_{{1i}} $

of observed independent variables for all values of the j. The

${\rm X}_{{1i}} $

of observed independent variables for all values of the j. The

![]() ${\rm \rbeta }_{{2{\rm j}}} $

’s coefficients vary according to the cut point of the ordered logit model and are associated to a subset

${\rm \rbeta }_{{2{\rm j}}} $

’s coefficients vary according to the cut point of the ordered logit model and are associated to a subset

![]() ${\rm X}_{{2i}} $

of observed independent variables that can differ for all values of j. Finally, M represents the different categories of the dependent variable. When M is smaller than 2, the program runs binary logistic regression where it contrasts the different categories (j) to each other. From this, we can then detect not only which of the independent variables violates the assumption, but also for which category of the dependent variable the assumption is violated. It may be for only one, or for all categories.

${\rm X}_{{2i}} $

of observed independent variables that can differ for all values of j. Finally, M represents the different categories of the dependent variable. When M is smaller than 2, the program runs binary logistic regression where it contrasts the different categories (j) to each other. From this, we can then detect not only which of the independent variables violates the assumption, but also for which category of the dependent variable the assumption is violated. It may be for only one, or for all categories.

It is also possible, in order to relax the proportional odds assumption, to use a multinomial logistic regression. A multinomial logistic regression estimates the individual effect of all independent variables for each answer category of the dependent variable, which makes the results unnecessarily complicated to read and interpret. Furthermore, the model does not consider that the categories follow in a certain order. However, as already described, with a partial proportional odds model, only the coefficients for those variables that violate the assumption will be shown and the order of categories will be intact.

One of the models that compares Denmark and Sweden (“Stay loyal”) did not pass the Brant test for two control variables (gender and seniority) and our main independent variable (country). We re-estimated the model using a gologit2. Our main result, the difference between countries is not affected by the models used. Thus, we will use the ordered logit regressions in those models (for the gologit2 model, see Appendix Table A1).

Controls

We include the following control variables in the analyses:

Gender

The distribution of women and men is slightly different among political advisers and civil servants. In the Swedish administration, 50% of the civil servants and 59% of the political advisers are men. The corresponding Danish figures are 66% and 88%. Research is inconclusive on whether responses are gendered; some studies find that women and men engage in voice differently (Liljegren et al. Reference Liljegren, Nordlund and Ekberg2008; Hsiung and Yang Reference Hsiung and Yang2012; Vantilborgh 2015), others find no gender differences at all (Lewis and Park Reference Lewis and Park1989; Lee and Varon Reference Lee and Varon2016). Since a possible gender effect cannot be disregarded, we include gender in the analyses. Women are coded as 1 and men as 0.

Age

The average age of political advisers in Sweden and Denmark is 36–40. The average age of civil servants in Denmark is 41–45 and in Sweden 46–50. Other studies have found that older employees are more risk averse (Moynihan and Landuyt Reference Mulgan2008) and more loyal to their organisations (Kellough and Osuna Reference Kellough and Osuna1995). Age consists of 11 categories of four years from 21–25 through 70+.

Management position

The hierarchical position of an employee may affect her response to perceived harmful proposals. Chief executives are often more likely to stay loyal or express internal voice when discontented (Dowding et al. Reference Dowding, Mergoupis and van Vugt2000; Hooghiemstra and van Manen Reference Hooghiemstra and van Manen2002). They have invested more resources in the organisation and the cost associated with losing position or leaving is higher for them than for lower-level managers. Promotions in public administration are somewhat dependent on the absence of prior failure (Niskanen Reference Overeem1971), which means that senior civil servants are likely to be cautious individuals do not opt for risky responses (Kingston Reference Kingston2002). Managerial positions (chief executives) are coded as 1 and lower positions as 0 in the models comparing Swedish political advisers and civil servants. As mentioned above, political advisers are never managers, except for the Swedish state secretaries. Managerial position is not included in the Danish-Swedish comparisons of civil servants, since all respondents in these analyses are managers.

Seniority

Civil servants work longer at the ministries than political advisers. The average years of service for the political advisers are three in Sweden and one in Denmark. The corresponding figures for the civil servants are 11 and 9 years. Just like managers, employees who have worked in an organisation for a long time have invested more resources in that organisation than new recruits. They are therefore more likely to opt for loyalty or internal voice. Hirschman suggests that voice “is an art that can be developed” (Dowding and John Reference Dowding and John2012, 13), which implies that people who work within the same organisation for a long time can learn how to voice efficiently within that context. Those who stay in an organisation for a long time also tend to embrace its norms and thus be more loyal (Kingston Reference Kingston2002). Seniority – years at the department – runs from 1 to 22.

Department size

Ministry size is relevant, since smaller organisations entail closer relations between leadership and employees, something that may affect the voicing behaviour of the latter (Kingston Reference Kingston2002). Swedish ministers are allowed different numbers of political advisers depending on the scope of their portfolio and their placement in government committees. Most political advisers in Sweden (69%) are therefore placed in large departments. The corresponding figure for civil servants is 80% in Sweden. Since Denmark has another system with a fixed number of political advisers, the share of political advisers does not increase with the size of the ministry. Department size is coded 0 for smaller departments and 1 for the five largest departments in terms of personnel.Footnote 2

Ideology

Ideology is included, since the political sympathies of a civil servant might influence to what extent she feels loyalty and trust towards her political principals. Ideally, this is something that should not matter for how civil servants carry out their work (Weber Reference Whitford and Lee1946), but in reality, this may very well influence how they respond to policy proposals that they perceive as harmful. Politicisation of the civil service has, for example, sometimes been motivated by politicians as a way to sidestep or counter what they perceive to be ideologically driven parts of the public administration (Pfiffner Reference Rouban1985; Levin Reference Levin1983; Dickinson and Rudalevige Reference Dickinson and Rudalevige2005; Rouban Reference Rourke2012). Previous studies have also shown that civil servants working at the Swedish ministries tend to place themselves further to the left than to the right on the political spectrum (Government Investigation 1990; Ehn Reference Ehn1998; Niklasson Reference Niskanen2007). Any potential differences between the civil servants and the political advisers may therefore be a matter of ideology rather than their terms of employment. To capture ideological deviation from the leadership we use The Swedish Parliament Study, which is a well-established survey of Swedish MPs. The survey has an expectational high response rate (88%). We are therefore able to develop a very reliable measurement of the ideological position of each party by using information on where the MPs of each party place themselves on a left-right scale running from 0 to 10. The scale is the same for the MP survey and our Swedish survey. Since each department is dominated by a single party, we calculated the mean among MPs for the relevant party and assumed that this would also be the mean of their department/s. In the next step, we computed how much every Swedish respondent deviated from the ideological mean of her department.Footnote 3 The scale runs from 0.1 to 7.6.

We lack data that would allow us to control for other potentially relevant variables, such as personal income, job security or career concern. Some of these effects are captured by the managerial position and seniority variables. On an aggregated level, these factors can be claimed to be included through our MSSD when we compare Swedish and Danish civil servants. Civil servants in Denmark and Sweden are protected by special employment laws to the same extent and their careers tend to be equally long (Dalström and Lapuente 2017, 64pp). The average Danish top civil servant earns more than her Swedish colleague, but living costs are also higher in Denmark. Compared to the average full time working Dane, the top civil servants included in our survey have a 48% higher income. The corresponding Swedish figure is 30%. Danish political advisers earn about the same as an average top civil servant, but they are also fewer in number than in Sweden and have a position very close to the minister. Swedish political advisers earn less on average, but they are a differentiated group ranging from the state secretary to political advisers in a relatively early stage of their career (salary statistics provided via email by the Swedish and Danish Government Offices for 2012). We do not have reason to believe that these differences in wages between and within countries systematically affect the responses from advisers and civil servants.

Part of the difference between political advisers and civil servants may be explained by differences in job insecurity (notoriously greater for political advisers) and in the degree of risk aversion (notoriously greater for civil servants, because they typically enjoy life-long careers at Scandinavian ministries) – but these differences are captured by the job descriptions of civil servants and political advisers; job insecurity is part of the deal for political advisers and the character of that deal is one of our main points in arguing for Hypotheses H1 and H2.

Results

Figure 1 shows the proportion for each category of our six response options among Danish and Swedish civil servants and political advisers combined.Footnote 4 Overall, the options score very differently. Criticism is much more likely to be raised internally than externally. By far, the most common reaction when civil servants and political advisers are confronted with decisions they perceive will have negative societal consequences is to talk to their superiors: 96% state that they are “very likely” or “fairly likely” to do so. Nor would they hesitate to bring their concerns to the political leadership (78%).

Figure 1 Civil servants’ and political advisers’ propensity to use different response options in Denmark and Sweden (%).

There is also a clear demarcation line between external and internal voice options. Ministry employees are unwilling to share their concerns with people outside the ministry, particularly the media. Hardly any (only 2%) state that they would be very likely to talk to colleagues at other departments and no one states that they are very likely to talk to the media. Just like Scandinavian parties (Jensen Reference Jensen2000; Öhberg and Naurin Reference Öhberg and Naurin2015), departments appear to act as collective entities where individuals mainly remain loyal to their organisations.

The respondents were also offered a silent response option: remain loyal and try to change the policies through their daily work. 12–14% claim that they would be “very likely” or “fairly likely” to choose these options. It is noteworthy that the ministerial staff would much rather keep silent than speak to the press about a policy about which they are seriously concerned.

The takeaway from this descriptive section is that the leadership will most certainly hear from their staff if they have concerns about a policy proposal. It is not likely that these voices will reach a broader audience through the media. Apparently, very much needs to be at stake before ministerial staff reach out to journalists.

We test our two first hypotheses on Swedish data only. Our first hypothesis (H1) states that political advisers are more likely than civil servants to voice internally. Hypothesis H1 is tested by two indicators: (a) the propensity to raise concerns to a superior and (b) the propensity to talk to the political leadership.

Table 1 presents the results of the generalised ordered logit model.Footnote 5 For those independent variables that do not violate the parallel assumption only the beta coefficients are shown. Gamma coefficients are presented for those independent variables that violate the assumption of parallel odds. The model shows that the effects of age, gender and seniority are constant across the four categories of the dependent variables, whereas political advisers, chief executives and large ministries violate the assumption in some (but not all) models, depending on the outcome variable. We discuss this below.

Hypothesis H1 is partly supported. There is a significant difference between civil servants’ and political advisers’ propensities to raise concerns to the political leadership. The predicted value for political advisers to state that they are “very likely” to do so is 67%, for civil servants: 37%. Moreover, the predicted probability for political advisers to be “fairly likely” to talk to the political leadership is 33%, while it is 45% for civil servants (cf. Table A5).

For the control variables, we note that chief executives are more likely to take the case to their nearest superior. Among the chief executives, the propensity to state that they are “very likely” to take concerns to the political leadership is 53%. For ordinary civil servants, it is 38%. Instead, there is a higher propensity for the latter to state that it is “fairly likely” that they will do so (44% versus 39% for chief executives). The two groups thus emphasise their readiness to address the political leadership differently. There is also an effect of age. Like Moynihan and Landuyt (Reference Mulgan2008), we find that older employees are less willing to raise their voices internally to the political leadership. Moreover, ideology matters. Employees who differ from their ministries ideologically are less likely to voice to the political leadership. Since the political principals at all departments lean to the right in the Swedish study, this means that left-wing employees are more hesitant to voice internally to the politicians.Footnote 6

However, the second indicator of internal voice does not support H1; there is no significant difference between political advisers’ and civil servants’ propensity to talk to their immediate superior. This is probably not very surprising, given that the political advisers’ immediate superior is the minister, or possibly the state secretary, who both make up the political leadership in the ministry. To political advisers, the survey questions about the political leadership and the immediate superior thus appear to ask the same thing twice, so they answer more or less the same to both questions (see Figure 1).

The civil servants’ superiors are directors general and division leaders and the civil servants are much more likely to speak to them than to the political leadership. Civil servants are thus not less inclined to express internal voice than political advisers, but they use different channels. The efficiency of their preferred channel is less obvious, however, since they only reach the political leadership indirectly. Still, there is little risk that civil servants will just sit back and watch perceived harmful policies being passed without voicing.

Among the control variables, age is again negatively correlated with a willingness to voice. Chief executives, however, who are more prone to voice to the political principals than ordinary civil servants, are less likely to voice internally to the nonpolitical leadership. This is not surprising, since there is no such level above the chief executives in the Swedish ministries. There is, moreover, an effect of department size. Employees in larger departments have a higher propensity to talk with the leadership. An interesting nonsignificant difference is that ideological deviation from the political principals does not matter for the propensity to voice to the nonpolitical leadership. Thus, ideological differences between politicians and civil servants will not prevent internal voice from being expressed. Although politicians will primarily hear from employees who share their ideological conviction, all employees are willing to turn to their nonpolitical superiors. The leadership will thus most likely find out if their employees believe a policy proposal to have harmful effects.

Our second hypothesis (H2) states that civil servants are more willing than political advisers to express voice externally. The indicator used is the respondents’ propensity to vent their concerns to colleagues in other departments. Hypothesis H2 is supported, cf. Table A5. Political advisers are less inclined to go outside the ministry with their problems. They are almost as unlikely to talk to colleagues in other departments as they are likely to talk to the political leadership in their own. 63% is the predicted value for political advisers to “not very likely at all” speak to other departments. For civil servants: 46%. Yet, it looks as if there is a reversed U-shaped effect of the political advisers on the third category on this dependent variable, since the coefficient is negative. However, this pattern arises because civil servants and political advisers put different emphasis on the likelihood of not talking to colleagues in other departments. As shown above, a clear majority of the political advisers state that they would not voice to other departments (63%), and only 23% state that it is “Fairly likely” that they would do so. The answers of the civil servants are more evenly spread; 38% state that it is “Fairly likely” that they would talk to people from other departments. For the other answer categories, there are no clear differences between political advisers and civil servants; 17% of the civil servants state that it is “very likely” or “fairly likely” that they would talk to people in other departments. For political advisers, it is 11%.

We also detect that senior staff and chief executives are more sceptical about talking to other ministries. Given the time and effort, these groups have invested in their organisations, they can be expected to be more cautious about criticising them in front of outsiders (Dowding et al. Reference Dowding, Mergoupis and van Vugt2000; Hooghiemstra and van Manen Reference Hooghiemstra and van Manen2002; Kingston Reference Kingston2002).

We now turn to Hypothesis H3, where we test the effect of functional politicisation. Table 2 shows that Hypothesis H3 receives some support in our data. Danish civil servants are significantly more silent in the sense that they are more inclined to keep their peace and work loyally, even for a policy that they perceive as harmful to their country. Danish civil servants are also more prone to accept, but quietly try to change a policy they disapprove of.

Table 2 Civil servants’ responses to perceived harmful policy proposals in Denmark and Sweden (ordered logit regressions)

Note: The dependent variables run between: “Not likely at all=1,” “Not very likely =2,” “Fairly likely=3” and “Very likely=4.” The respondents are clustered to their departments. Robust standard errors in parentheses ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1.

When it comes to internal voice, Danish civil servants are significantly less willing to talk to the political leadership. We have calculated that 24% are predicted to state it “very likely” that they would do so compared to 38% of their Swedish counterparts. There is no difference between the two countries when it comes to raising the issue to immediate superiors, however. Thus, Danish civil servants do not compensate by showing a greater inclination to speak to the chief executives.

Neither are Danish civil servants more likely to voice their concerns to colleagues in other departments. Rather, the overall impression is that they are more reluctant to respond by expressing external voice, since significantly fewer of them say that they would be prepared to leak information to the press.

Few control variables show consistent significant effects. Age matters to some extent, as older employees are less willing to talk to immediate superiors and political superiors. They are more prone to silent resistance. Senior employees seem to have a higher propensity to discuss their concerns with the political leadership than junior employees (cf. Kingston Reference Kingston2002). Employees in large departments are less likely to talk to political superiors, perhaps because of fewer opportunities to do so. Instead, they find silent resistance more feasible. Calculations show that 14% of the women compared to 10% of the men say that they are “fairly likely,” or “very likely” to work loyally for the implementation of a policy, even when it may be harmful to their country. We have also controlled for (1) the ideological position of the individual civil servant, (2) the difference between the individual civil servant and the average left-right position of the civil servants in that department and (3) the difference between the ideological position of the individual civil servant and that of the party which controls her ministry. None of these variables is significant. The tests are only carried out on the Swedish data, since we do not have the left-right positions of the Danish civil servants.

We interpret the Danish-Swedish difference as an effect of the higher level of functional politicisation in Denmark, but we are aware that our MSSD is not perfect; competing explanations that have not been controlled for cannot be excluded. Still, for this kind of comparative design, not many other countries would have been better suited. More importantly, the results make sense theoretically, which makes us inclined to claim that we find Hypothesis H3 supported.

Conclusion

Civil servants and political advisers will from time to time be in situations where they perceive that a political decision is wrong. That will force them into considerations about how to respond to this situation.

Our analyses are based on the responses of Danish and Swedish political advisers and civil servants as stated in two web surveys. We show that political advisers are more likely than civil servants to raise their voices internally to the political leadership. Hypothesis H1 is thus partially supported, as the civil servants turn out to be more willing to voice internally to their immediate superiors, like the civil servant in the Danish scandal. Given the different terms of employment and the different roles of political advisers and civil servants, it is reasonable to assume that the variation in the preferred responses depends on their access and loyalty to the political leadership. How smoothly and efficiently these channels reach the minister’s ear is another question.

External channels – voicing to colleagues in other departments and leaking to the press – can also be used. We hypothesised that external voice will be more readily used by civil servants (Hypothesis H2). Our results confirm that they are in fact more open to voicing concerns regarding perceived detrimental policies externally to colleagues in other departments.

Hypothesis H2 is only partially supported, though; neither civil servants nor political advisers are particularly keen on leaking to the press. This result is perhaps not surprising considering how risky and ill thought of this response is (Niemann Reference Niklasson2013, 193).

Danish civil servants are even less likely to leak than their Swedish colleagues. Furthermore, Danish civil servants are also more hesitant to voice their concerns internally to the political leadership and more likely to respond through loyalty or silent resistance. The results support Hypothesis H3 but again only partially; there are no significant differences between the civil servants in Sweden and Denmark when it comes to voicing internally to immediate superiors or externally to colleagues in other departments.

To summarise, none of our three hypotheses receives undivided support, but all significant differences found in the data point in the expected direction. So what are the implications of these results for how we interpret the consequences of different forms of politicisation of ministerial advice? Our conclusion is that the level, as well as the kind of politicisation are likely to affect policy processes. The Swedish model, in which civil servants are shielded from some of the political-tactical tasks, increases the propensity of the civil servants to voice internally as well as externally if they perceive that their minister is on the wrong course. The Swedish model thus relieves some of the political pressure on civil servants, who otherwise risk being caught in-between their roles as political-tactical advisers and neutral civil servants, a position that may induce them to silence. The differences between Denmark and Sweden are not great, but they hint at a reason to focus on the level of functional politicisation of ministerial advice. Also, the Swedish case indicates that political recruitment of ministerial advice might decrease the chances of bad news reaching beyond the department should the number of political advisers grow too large in relation to the civil servants. Both systems thus appear to have their weaknesses.

This conclusion needs to be tested further in different contexts. Denmark and Sweden are not extreme cases. Other systems have a much higher degrees of politicisation. It would be interesting to see comparative studies, or in-depth case studies of how civil servants and political advisers respond to perceived harmful policies in those contexts; however, that is a task for future research.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X18000508.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to five anonymous reviewers and Professor Anthony Bertelli for valuable comments and suggestions.