INTRODUCTION

Africa has been for decades a playground for global powers. In the late 19th century, the term ‘scramble for Africa’, indicating a rivalry and competition among European powers for new territories and local resources, was coined for the first time. The second phase came during the Cold War when the West competed with the East for the newly independent African states. With the continent's economic renaissance recorded since the mid-1990s, causing Africa to become the second fastest growing continent in the world after Asia (World Bank 2020), the interest of – this time not only global, but also newly emerging powers – has intensified. According to some, we are in a new phase of the scramble for Africa (Southall & Melber Reference Southall and Melber2009; Carmody Reference Carmody2011; Ayers Reference Ayers2013).

Powers such as the UK, France, the USA, Japan, Turkey, India, Brazil, Russia and China (among others) have all increased their trade and investment activities on the continent, as they also did in the field of foreign policy and diplomacy. Indeed, Africa has a lot to offer. It is believed to account for 42% of global bauxite (deposits), 38% of global uranium, 42% of global gold and 73% of global platinum, among many other valuable resources (Carmody Reference Carmody2011). Additionally, it is home to more than a billion mostly young people whose number is projected to reach to 2.5 billion by 2050 (UN DESA 2020). But it is not only this that motivates states to (re)engage with the continent. For many of them, Africa has also recently regained strategic political and security significance.

Much of the discussion focuses on China's engagement with the continent (Ayers Reference Ayers2013; Kinyondo Reference Kinyondo2019; Hwang & Black Reference Hwang and Black2020). While for some China is not posing any threat and brings a lot of new opportunities for mutual cooperation and benefits, others believe that China, indeed, has become a new African coloniser (see Chen Reference Chen2016 for details). Such an ambivalent approach can be observed in the case of other powers, too. In the shadow of attention paid to the Chinese engagement with Africa, they also compete in gaining new strategic economic, security or political partnerships on the continent. This article focuses on one of them, the Russian Federation.

Russia has been present in Africa for centuries. The first encounters date back to the 11th century when Prince (Knyaz) Vladimir sent his first missionaries to Egypt. Initially religious in nature, these contacts soon enlarged into trade and the first diplomatic missions. In this regard, the most advances came with the Russian king (Tsar) Peter the Great and Empress Catherine the Great (Antoshin Reference Antoshin2012). But unlike the European powers, Russia has never colonised African territories. During the Soviet era, its presence was strong both economically and politically (see Besenyő Reference Besenyő2019 for details). However, after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the internal turmoil that the country went through, both in terms of political and economic development, Russia has recorded years of long distance from the continent. Thus, with its recent return Russia cannot be considered a newcomer (Hamchi & Rebiai Reference Hamchi, Rebiai, Ksenofontova and Abisheva2014).

Under President Vladimir Putin, Russia has started an internal debate on regaining the status of a global power (Herd & Akerman Reference Herd and Akerman2002; Lee Reference Lee2010; Nitoiu Reference Nitoiu2017). From this perspective, Africa was not high on the agenda. Exceptions were countries in North Africa and the Republic of South Africa which had already welcomed President Putin during the 2000s. Russia's revival of its Africa policy came only after 2014, mainly due to sanctions imposed on Russia following the Crimea annexation, the creation of the Euroasian Economic Union and Russian airstrikes on Syria (Kalika Reference Kalika2019). Since then, trade and investment with many African countries have been growing rapidly, as well as political and diplomatic meetings at various levels. Many African heads of states were also welcomed by Putin in Moscow. The rising interest of Russia in the continent was reflected in the first-ever Russia–Africa Summit and Economic Forum held in Sochi (Russia) in October 2019, attended by 43 African heads of states. As Simoncelli (Reference Simoncelli2019) argues, it ‘marked the culminating point of the Kremlin's renewed interest in the African continent and its political and economic assets’.

For Russia, military cooperation and nuclear energy were traditionally the major sources of power and tools of cooperation (Nitoiu Reference Nitoiu2017). In 2011, the former Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs (1998–2004), Igor Ivanov, called for a paradigm shift in Russian foreign policy. He called for a policy which diverted from ‘using a very limited set of military or energy tools’ while targeting the future that will be shaped by a smart economy. ‘A smart foreign policy requires the ability of the political leadership to make use of the widest range of assets at the disposal of a particular country and a particular society; including, of course, the nonmaterial assets, which were often ignored or at least seriously underestimated by the traditional diplomacy of the past’ (Ivanov Reference Ivanov2011). As an example, Ivanov mentioned ‘export of education’. In 2016, Russia introduced its latest Foreign Policy Concept. It aims to ‘strengthen Russia's position in global economic relations’ and to ‘consolidate the Russian Federation's position as a centre of influence in today's world’. It does not mention ‘smartness’ as such, but it stresses ‘soft power’ to achieve the policy goals (MFA 2016).

The aim of this article is to analyse Russia's recent return to Africa. We analyse the shift in Russia's foreign policy, we investigating the extent to which Russia has abandoned its traditional tools of military cooperation and nuclear energy and shifted to ‘smart’ ones. Also, we examine the motivations on both sides for the rapprochement. The article builds on three case studies of African countries which in 2018 (latest data available) recorded the highest trade volume with Russia. These are Egypt, Algeria and Morocco (WITS 2020). All of them are located in North Africa, a region holding a very special position in Russia's foreign policy. Russian official documents consider it both a part of Africa (where it geographically belongs and where countries are bonded by membership of the African Union, a key partner for Russia) and of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) where it belongs due to historical, cultural or ethnic reasons. This dichotomy, in combination with the recent increase in Russia's interests in the Middle East, recovering from numerous Arab uprisings, and influenced by the shift in President Obama's administration towards the Middle East, which has resulted in a power vacuum in the region enabling new states to come in and steer their interests (King Reference King2020), together with the rising interest of Russia in African affairs, makes a deeper analysis of the mutual relations of Russia with these three selected countries interesting. In particular, we investigate the recent changes in the economic cooperation of Russia with all three countries. We pay special attention to military cooperation and the energy sector as representatives of traditional tools of cooperation. Moreover, we analyse the recent uptick in activities in development cooperation as representatives of new tools. We also explore the political context of mutual relationship development. We work with the latest available data for trade and development cooperation covering the period 2009–2018, or 2019 for military products. Where possible, we add the most recent developments in 2020.

The structure of the article is as follows. In the first part, we set out the essential policy background for the latest U-turn in Russia's policy towards Africa, and North Africa in particular. We analyse major strategic documents of Russia such as the Concept of Foreign Policy, National Security Strategy, Military Doctrine and Energy Strategy. In the next section, we investigate the collaboration between the three selected countries and Russia from a political, economic and development perspective. For this part, we use mostly primary source data from organisations such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the World Bank (World Integrated Trade Solution, WITS), the World Nuclear Association (WNA) and the Stockholm Institute for Peace Research (SIPRI). Where appropriate, we supplement these data with official Russian sources. In the last part, we conclude with a summary of results.

RUSSIA'S RECENT RETURN TO AFRICA: A FOREIGN POLICY CONTEXT

The recent shift in Russia's approach towards Africa, and most notably North Africa, should be evaluated within a broader historical-political context of Russian foreign policy dynamics. The post-1990s foreign policymaking was largely influenced by the involvement of previously excluded non-political actors, such as federal and regional bureaucracies, business communities and think tanks (Koldunova Reference Koldunova2015: 385), as well as by internal civil unrest, the rise of poverty resulting from a ‘market opening strategy’ and a drastic ‘shock therapy’ adopted to shift from an administrative type of economy towards a market economy. This internal turmoil resulted in an initial decline in foreign policy activities (El-Doufani Reference El-Doufani1994; Koldunova Reference Koldunova2015). A partial revival started in the late 1990s following the second Balkan war. At that time, an increased search for national identity occurred within the foreign policy debate (Koldunova Reference Koldunova2015; Nitoiu Reference Nitoiu2017). Consequently, with President Putin in office, an intensive debate on ‘regaining the great power status’ has started and foreign policy activities have intensified (Herd & Akerman Reference Herd and Akerman2002; Lee Reference Lee2010; Nitoiu Reference Nitoiu2017).

The ambitions for a greater power status initially started with balancing the position of Russia against the West, represented by the USA and Europe. Later on, the idea of Eurasianism was introduced, focusing on Russia's integration project in Eurasia (Koldunova Reference Koldunova2015: 382). The turning point was the Munich speech of President Putin in 2007, in which he voiced a general discontent with activities of the West in both Eastern Europe and the Middle East (Allison Reference Allison2013). But as Ziegler (Reference Ziegler2016) highlights, the entire Western experience was not rejected. Concepts of free markets and private ownership were accepted, but active attempts by Western liberal democracies to subvert authoritarian regimes were rejected. As a result of all this, the regional scope of Russia's foreign policy has gradually enlarged. The initial focus on the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and other former Soviet countries has widened towards Eastern Europe and the Middle East, and most notably towards Asia, indicating Russia's foreign policy ‘turn to the East’ with China as its natural partner. Gradually, Africa and North Africa in particular also regained the status of a strategic region.

Re-emergence of Africa in Russia's foreign policy

The first Foreign Policy Concept (1993) after the fall of the Soviet Union placed Africa very low (MFA 2013). It could be explained by the ‘shrinking’ of all foreign policy activities and by the prioritisation of the CIS as Russia's ‘closer circle’. The next Foreign Policy Concept (2000) moved Africa a bit higher on the list, even higher than the Caucasus, which has been a traditional area of geopolitical interest for Russia over the last 10 centuries. However, the position was still rather low. In both latest versions (2013 and 2016), Africa is considered a partner for political dialogue and mutually beneficial trade (MFA 2016), but in in terms of priority, it still occupies a rather lower positions. However, the stress on ‘prevention of regional conflicts and facilitation of post-conflict settlements in Africa’ reinforces Africa's position in Russia's security and defence policy (MD 2015). The latest version of the National Security Strategy mentions the development of political, economic and military cooperation with Africa as a priority in constructing Russian strategic stability and places bilateral cooperation with Africa even higher than with the USA and Europe (MD 2015).

Within this framework, North Africa holds a very special position among other African subregions. From the Russian point of view, it is important to stress that all North African countries are members of the African Union, which Russia considers an important element of its policy towards Africa (MFA 2016). Indeed, the African Union plays an increasing role in post-conflict settlement across the region. At the same time, Russia considers (as well as many other countries) North Africa as a part of the MENA region. It was in 2000 that North Africa was mentioned for the first time separately from Africa in Russia's Foreign Policy Concept, in a clearly expressed connection with Russia's aim to ‘stabilize the situation in the Middle East’ (MFA 2000). As time went by, this special position of North Africa has remained, even though Russia's priorities have changed. In 2008, the MENA region was mentioned in the Foreign Policy Concept with regards to developing cooperation in the energy sector (MFA 2008); the latest version stresses the fight against international terrorism (MFA 2016).

The recent revival of Russian activities with Egypt, Algeria and Morocco thus needs to be understood not only in the context of Russia's return to Africa but also in the context of Russia's return to the Middle East. We also cannot forget that North Africa is a part of the Mediterranean region, where Russia has recently started pursuing its interests. In search for Russia's motivations to re-engage with these countries, the following recent events were identified as having the largest impact based on a literature review. First, the ‘sanctions wars’ (2014) between Russia and the USA and the EU which created an impetus for Russia to start a search for new markets for both its exports and sources of imports of some goods, mostly food products (Gerőcs Reference Gerőcs2019). Second, the creation of the Euroasian Economic Union in 2014 encouraged Russia to actively seek to strengthen its geopolitical position by signing free trade agreements with other countries outside of the Post-Soviet space (Mostafa & Mahmood Reference Mostafa and Mahmood2018). Third, Russia's reinforced presence in Syria since 2015 which helped Russia regain the status of ‘an honest broker in the region’ at the same time pushed it to search for (military) allies to help pursue Russian interests in the Middle East (Stent Reference Stent2020). Fourth, Russia's most recent foray into Libya created a space to search for countries looking for a ‘back door’ to Libya (Farag Reference Farag2020). And last but not least, the recently deepening disagreement with Europe over many issues has created a space for Russia to search for ways to exert pressure on Europe. North Africa as one of the important suppliers of gas and oil to Europe may play a crucial role in this regard (Besenyő Reference Besenyő2019).

Traditional instruments of cooperation in Russia's recent return to Africa

Military cooperation and nuclear energy were traditionally the major sources of power and cooperation for Russia. Nowadays, the military priorities of the Russian federation abroad are formulated in two fundamental documents that simultaneously shape the legal framework of foreign policy and manifest its major goals and regional priorities – the Military Doctrine and the National Security Strategy. Nuclear energy is a fundamental part of energy security, which is reflected in the Energy Strategy of Russia for the period up to 2030.

The Military Doctrine formulates the basic provisions of military policy and military economic support for the defence of the state (MD 2014). The document has a rather defensive character (Pietkiewitz Reference Pietkiewitz2018). It commits Russia to protecting its national interests and the interests of allies, while widening the scope of allies is among its priorities. Military cooperation (both in defence and trade) with allies has a great importance, as it is well developed in both sectoral and regional scope and priorities. Besides defining the military threats, the Doctrine also states various types of military cooperation ranging from UN peacekeeping to nuclear containment (MD 2014). The importance attached to the role of military power is also reiterated in the National Security Strategy. This document clearly states that the use of force as an instrument of advancing foreign activities is only allowed as a means of last resort after all diplomatic and other non-violent measures to protect national security might have failed (MD 2015).

As mentioned earlier, Russia has been sanctioned by the USA and EU following Russian involvement in Ukraine in 2014. Those sanctions were, among others, targeting the Russian arms trade. It resulted in an 18% decline in Russia's military exports in 2015–2019. However, despite this, Russia has remained the second largest arms exporter in the world after the USA (SIPRI 2020). And interestingly, Africa has re-emerged as a significant trade partner for Russia. As Besenyő (Reference Besenyő2019) argues, the defence industry has a special and very successful status within the current economic cooperation of Russia with Africa. Russia has recently become the largest arms supplier to Africa, accounting for 35% of arms exports to the region, followed by China (17%), the USA (9.6%) and France (6.9%). Since 2015, Russia has also signed over 20 new bilateral military agreements with African states (Adibe Reference Adibe2019).

The Energy Strategy sets goals and priorities for Russia's energy sector up to 2030. According to it, Russia aims to remain the leading player in the world hydrocarbon, electricity and coal markets, while strengthening its position in the world nuclear energy industry (ME 2010). Regarding Africa, the Russian leadership considers it important to have access to African oil and gas fields, mostly with the aim of influencing projects representing the EU's alternative supply sources, which would subsequently lower its dependency on Russia (Besenyő Reference Besenyő2019). Most notably, this applies to North Africa and Algeria in particular (see below). According to the World Nuclear Association (WNA), Russia continues with plans to expand the role of nuclear energy, including development of new reactor technology (WNA 2020). Russia's recent pivot towards Africa is gaining momentum in this regard. Africa represents a continent full of opportunities where energy is in high demand and the continent has barely any nuclear power plants. Negotiations over construction of new nuclear power plants are ongoing with countries such as South Africa, Ghana, Nigeria, Algeria, Zambia and Kenya. But so far they have only been concluded successfully with Egypt (Luzin Reference Luzin2020). For Russia, such cooperation is not only about building power plants but also about training African nuclear specialists or setting up centres for atomic science and technology. The use of ‘smart’ tools of cooperation, as indicated by Foreign Minister Ivanov, is an important element of the Russian energy policy towards Africa.

New instruments of cooperation in Russia's recent return to Africa

The latest Foreign Policy Concept (2016) stresses that ‘soft power’ has to be employed to achieve the foreign policy goals. Special attention is attached to international humanitarian cooperation and human rights (MFA 2016). Indeed, the Soviet Union used to be a dominant player in the field of development (in Russian official documents referred to as humanitarian) assistance. However, as did most of its other foreign activities, the aid programme collapsed with the end of the Soviet Union (Burkhardt Reference Burkhardt2019: 3). The revival came with Russia's aspirations to regain global power status in the mid-2000s. The first International Development Assistance Concept, introduced in 2007 (and renewed in 2014) declared many goals ranging from ‘elimination of poverty and facilitating socioeconomic development in developing and post-conflict countries’, to ‘developing trade and economic cooperation’, ‘preventing the occurrence and facilitating the elimination of focus points of tension and conflict’ and ‘strengthening the credibility of Russia and promoting an unbiased attitude to the Russian Federation in the international community’ (MF 2007). Both altruistic and self-interest motivations can be observed in these goals but as Burkhardt (Reference Burkhardt2019: 10) argues, as long as international development assistance remains highly politicised, it will most likely serve as another tool to enforce Russia's geopolitical and national interests. This rather confirms the later version of the Concept (2014) noting that ‘aid is provided to developing states, cooperation with which serves the interests of the Russian Federation’ (MFA 2014).

Within the period under analysis, Russia has significantly increased its development cooperation budget; from US$415.9 million in 2010 to US$1,521 million in 2016, with a decrease to US$1,189.6 million in 2017. The OECD preliminary data for 2018 suggest that the threshold of US$1 billion was also reached for this year (OECD 2020). Most of the aid has been distributed on a bilateral basis. Sub-Saharan Africa together with North Africa and the Middle East have received only a small share (10.9%) of the budget over the last five years (Aidwatch 2020). However, the less aid means in terms of money, the more aid means for mutual relationships in terms of its ‘soft power’.

The instrument of the ‘export of education’, whose renewal Minister Igor Ivanov has called for, has a long tradition in Russia's foreign policy or international development assistance (Kukin Reference Kukin2019). The tradition was reduced significantly after the collapse of the Soviet Union but restored recently. In 2018, 17,000 African students studied at Russian universities, of which 4,000 received scholarships (Kukin Reference Kukin2019). To illustrate the soft power of this instrument, we can note that since the 1970s about 400,000 African students in total received education in the Soviet Union or Russia (Kalika Reference Kalika2019). Some of them have taken high positions in African politics or business. The most recent example is the current President of Angola, João Lourenço. In 2019, during his visit to Moscow, Angola, as one of the principal buyers of Russian arms, also signed new deals in diamond mining, gas and oil production, space and agriculture (Africa News 6.4.2019). Considering the benefits that this aid instrument brings, it is not surprising that Russia's interest in educational cooperation has increased again. During the Russia–Africa summit in 2019, increasing the number of scholarships for students from Africa and the possibility of opening branches of Russian universities on the African continent have been discussed (Kotyukov Reference Kotyukov2019). As a result, the number of scholarships for African students should double by 2024 (Ria Novosti 12.2.2020). Interestingly, the Russian business community interested in expanding its presence on the African market has joined these efforts, providing scholarships to African students in corresponding specialisations, too. For example, Rosatom joined this programme in 2010. Currently, about 300 students from more than 15 African countries (including Algeria and Egypt) study nuclear engineering in Russia (Kukin Reference Kukin2019).

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF RUSSIA'S RECENT RETURN TO EGYPT, ALGERIA AND MOROCCO

In this section, we present the results of our comparative analysis of three case studies. In each subsection, we give a short introduction to the history of bilateral relations. Then we follow with an analysis of recent developments at the highest diplomatic and political levels to better understand motivations on both sides to re-engage in cooperation. We further explore the traditional military and nuclear energy tools of cooperation, both framed within the context of broader economic cooperation. We conclude with an analysis of the re-emergence of ‘smart’ tools in the field of development cooperation.

Russia and Egypt: close allies in military and nuclear energy

The first encounters between Russia and Egypt date back to the 11th century. Since then, trade has been an important element in their mutual relationship. Traditionally, Russia exported to Egypt sugar, tobacco, flour, kerosene and alcohol, and they imported cotton (Antoshin Reference Antoshin2012). Motivations for cooperation increased when Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, initially taking an anti-imperialist stance towards both the USA and the Soviet Union, changed his approach during the Suez Crisis in 1956. Egypt switched to a pro-Soviet orientation and after that Moscow considered it a ‘key stronghold’ in the region (Purat & Bielecki Reference Purat and Bielecki2018). The Soviet Union quickly become Egypt's principal arms supplier (Aftandilian Reference Aftandilian2019). Moreover, many important infrastructure projects were carried out in Egypt with the assistance of the Soviet Union, such as the Aswan High Dam, the Helwan Iron and Steel Factory, and the Nag Hammadi Aluminum Plant (Embassy of the Russian Federation to the Arab Republic of Egypt 2020). However, after the death of President Nasser, the relationship between the countries significantly declined.

Partial resumption came with President Honsi Mubarak. During his 29-year-long rule, the most notable change came under with President Putin. But it was only in 2014 with President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi that the mutual relationship entered its most dynamic phase so far. As Issaev (Reference Issaev2017) argues, the tendency of Moscow to establish relations with authoritarian regimes also experiencing difficulties with relations with the West contributed to their rapprochement. But first and foremost, it is the significance of Egypt, as the leading political, economic and cultural centre of the Middle East, that Russia hopes to use in pursuing its interests in the region. Moreover, Russia's recent efforts to arbitrate the Egypt–Ethiopia dam dispute suggest that African security issues might become a new frontier for bilateral cooperation with Egypt (Ramani Reference Ramani2019). The rapprochement is not smooth though, as indicated by the three-year-long ban of the Russian national carrier Aeroflot on flights to Egypt following the explosion of a bomb on a Russian plane over Sharm el-Sheikh (BBC 13.11.2015).

It is also worth mentioning that re-engagement between both countries was accelerated by the US and EU policy towards Egypt around 2013 and onwards. Traditionally, Egypt has been a close US ally in the region, enjoying, among others, a benefit of US$1.3 billion annually as military assistance. However, since 2013, this aid has been suspended several times because of rising concerns over Egypt's poor human rights protection and its military connections with countries such as North Korea (Aftandilian Reference Aftandilian2019). Consequently, the US imposed an arms embargo on Egypt in 2013, following the continuously worsening situation. Moreover, the USA threatened to impose another embargo four years later when Egypt was planning to buy fighter jets from Russia (AlJazeera 15.11.2019). Issaev (Reference Issaev2017) argues that this was an Egyptian effort to ‘make Washington jealous’, but in fact, the USA clearly revealed that closer ties between Russia and Egypt are ‘causing them a headache’ (Aftandilian Reference Aftandilian2019). Besides, the EU also imposed an arms embargo on Egypt in 2013 not as a legally binding sanction but rather as a political commitment (SIPRI 2017).

Diplomatic level

To underline the rising importance of the mutual relationship, numerous high-level meetings occurred over the analysed period. These started in 2005 when President Putin embarked on his first visit to Egypt. Since then, he has repeated it twice in 2015 and 2017. Vice versa, three Egyptian presidents (Mubarak, Morsi and Al-Sisi) visited Moscow. President Al-Sisi visited Moscow four times. The first time was shortly after he seized power in a military coup. At that time, he was not only warmly welcomed by President Putin, but Putin also made a surprising public declaration in support of his presidency before it was even officially announced (The Telegraph 13.2.2014). This close tie has been reflected lately in numerous deals which have been signed, including an arms deal worth US$3.5 billion (2014), or an important Egyptian approval to allow Russian aircraft to use Egyptian bases and airspace (2017). This deal significantly helped Russia to gain a ‘back door to Libya’ and to exert pressure on Europe in the Mediterranean (Farag Reference Farag2020).

Economic cooperation

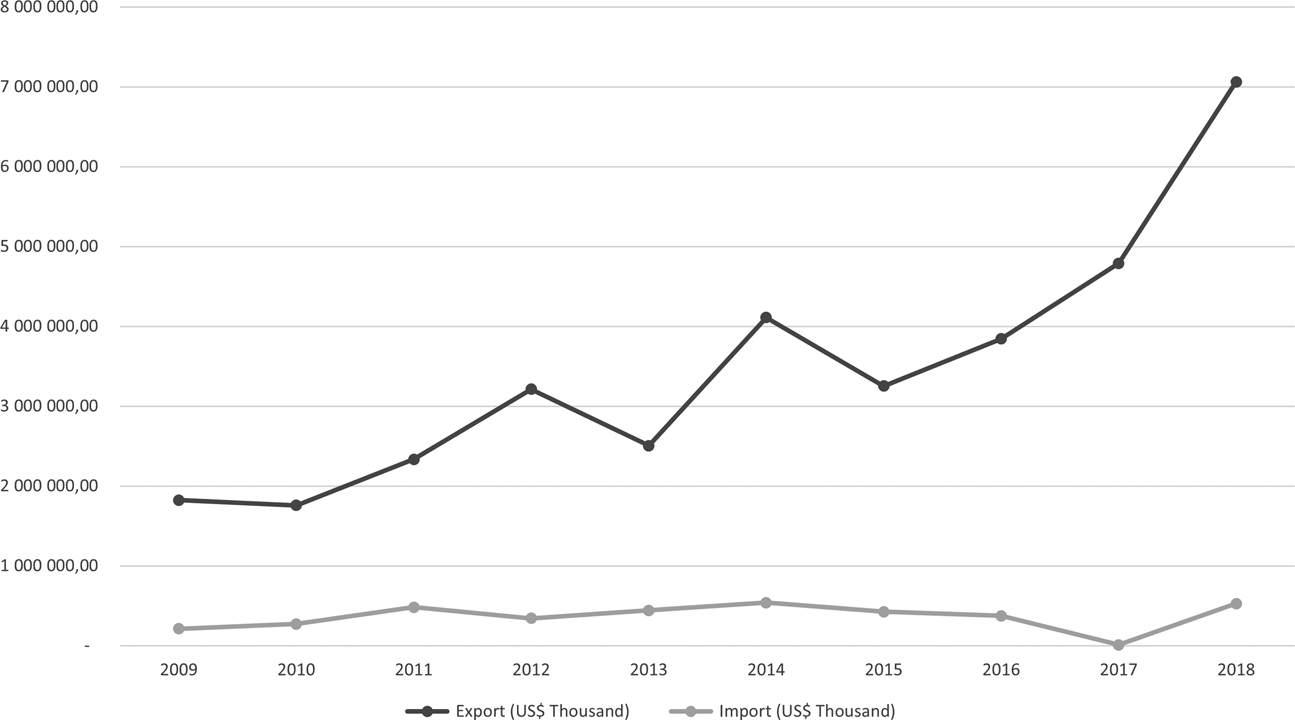

The trade balance between both countries steadily increased over the period under review period (see Figure 1). For the whole time, Russia's exports to Egypt exceeded imports and the gap significantly widened over time. One can also see the sharp U-turn in Russia's exports to Egypt after 2015, shortly after the EU and US sanctions against Russia were imposed and the 2014 arms deal was signed. As a consequence, Russia's share in Egypt's imports rose up to 6% (2018), making it the fourth most important trade partner after China, Saudi Arabia and the USA. With regard to commodity structure, in 2018 Russia exported to Egypt mostly food (including wheat), manufacture goods (including arms), fuels, ores and metals, and imported in the vast majority food and to a lesser extent manufactured goods and textiles (WITS 2020).

Figure 1 Russia's trade with Egypt in 2009–2018 (US$ thousands). Source: WITS (2020).

During the Sochi summit (2019), both Presidents Putin and Al-Sisi reaffirmed the commitment to scale up cooperation, mostly in two areas – building the Russian industrial zone in the Suez Canal Economic Zone and construction of four proposed nuclear power plants (Modern Diplomacy 14.6.2020). Moreover, the Russian companies Rosneft and Lukoil had already indicated a clear interest in expanding cooperation to other fields such as the development of hydrocarbon deposits in both Egypt and its continental shelf (Embassy of the Russian Federation to the Arab Republic of Egypt 2020). It is also important to mention that both countries currently negotiate free trade agreements between Egypt and the Euroasian Economic Union (Daily News Egypt 4.6.2020).

Nuclear energy

Egypt may soon become a showcase of Russia's recent nuclear energy diplomacy in Africa. The licence for the Russian company Rosatom to build a US$30 billion nuclear power plant El Dabaa is expected to be issued in late 2021 (Egypt Today 18.8.2020). It is likely to be ‘the most expensive nuclear deal in history’ (Luzin Reference Luzin2020). Most of the costs (US$25 billion) were provided to Egypt as a loan. Egypt will have to start its repayment shortly after the construction is completed. This condition could represent Russia's weak point in further promotion of nuclear energy to African counterparts (Luzin Reference Luzin2020).

Military cooperation

Egypt holds the position of the world's third largest arms importer in the world after Saudi Arabia and India. For Russia, Egypt is the second largest African arms importer after Algeria and for Egypt, Russia is the second largest arms supplier after France (SIPRI 2020). The trade has significantly intensified with President Al-Sisi. From just 2015–2019, Russia's arms exports to Egypt increased by 191% compared with 2010–2014. According to Russian customs statistics, in 2018 the total value reached US$2.1 billion and in 2019 US$2.4 billion (RBC 2020). The upward trend coincides with Egypt's rising military involvement in Libya, Yemen and the Sinai Peninsula (SIPRI 2020). It can also be attributed to the 2014 arms deal with Russia. With the latest arms deal worth US$2 billion, Egypt could soon become the major African importer of Russian arms (Khlebnikov Reference Khlebnikov2019).

Development cooperation

Based on very limited evidence, Egypt enjoys benefits of the ‘export of education’ in the field of development cooperation. The number of Egyptian students in Russia reached 4,377 in 2019. Most of them pay for their studies or obtain financing from companies; however, the number of state scholarships is also steadily growing and reached 119 in 2019 (MSHE 2020). Nuclear physics is one of the most popular specialisations for Egyptian students; the future employees of the El Dabaa power plant are so trained, for example. Some Russian universities prepare other specialists in collaboration with Egyptian educational institutions. For example, Tomsk Polytechnic University has a double degree programme ‘Nuclear Power Plants: Design, Operation, and Engineering’ in partnership with the Egyptian–Russian University (Study in Russia 2019). This indicates that export of education has become a crucial element of Russia's energy policy towards Egypt. And it also seems to bear fruit.

Russia and Algeria: old military allies expand cooperation to energy sector

The first important treaty between both countries was signed in the late 18th century under the reign of Catherine the Great (Antoshin Reference Antoshin2012). It set up a tradition of close ties in defence. During the Algerian War of Independence, the Soviet Union provided Algeria with political, military as well as financial support (Hamchi & Rebiai Reference Hamchi, Rebiai, Ksenofontova and Abisheva2014). This close connection continued in the 1970s and 1980s. Estimates indicate that between 1962 and 1989, Moscow supplied military equipment to Algeria worth US$11 billion, equal to 70–80% of Algeria's inventory (Katz Reference Katz2007). These arms were paid for by loans, and these were never fully repaid. Moreover, large-scale projects were implemented in various sectors of the economy at that time, such as metallurgical plants in El Hadjar and Annaba, the thermal power plant in Jijel, the Alrar–Tin Fouye–Hassi Messaud gas pipeline and the Beni-Zid and Tilezdit dams (Zherlitsina Reference Zherlitsina2015a).

The relationship between the countries ceased after 1991 as both were preoccupied with internal problems. Algeria partially revived its economic ties with Russia in the mid-1990s when several agreements on joint exploitation of oil reserves and contracts for construction of oil pipelines were signed (Antoshin Reference Antoshin2012). The recent revival is marked by President Bouteflika and President Putin who both took office around the same time. Shortly after being elected, they initiated talks on the resumption of a mutual relationship. Algeria welcomed Russia's resolve for involvement in the modernisation of various industries such as the fuel and power sectors, and Russia welcomed re-engagement with a traditionally strong importer of its military products. Not surprisingly, Algeria became the first Arab country to sign a strategic partnership agreement (2001) with Russia (Hamchi & Rebiai Reference Hamchi, Rebiai, Ksenofontova and Abisheva2014). The Russian motivations to re-engage with the continent, however, are also connected to its energy policy abroad (see below) and to its recent involvement in Libya. Indeed, this signals a mutual interest. Current Algerian President Tebboune has confirmed recently in an interview for Russia Today that he seeks to further tighten the relationship with Russia and to bring them ‘up to the level of political understanding’ (Algeria Press Service 22.2.2020). Through rapprochement with Russia, he primarily seeks to resolve the conflict in Libya, Algeria's ‘most pressing national security threat’ (AlJazeera 23.1.2020).

Diplomatic level

The rapprochement started in 2001 when President Bouteflika visited Moscow and signed two important documents, one concerning defence and the other strategic partnership (BIC 2019). Five years later, President Putin visited Algeria after a decades-long abstention. On this occasion, he signed an arms deal which is believed to be the biggest contract in the field of military-technical cooperation in Russian post-Soviet history (Izvestia 19.2.2008). No less importantly, by signing the deal, Russia pledged to write off Algeria's external debt to Russia (Kommersant 11.2.2008). Following the visit, additional agreements in the gas and oil industry were signed between the Russian state company Gazprom and the Algerian state company Sonatrach, confirming the hypothesis that Russia aims to influence projects of oil and gas supplies to the EU on the African continent, in order to prevent the EU from lowering its dependence on Russian energy supplies (Besenyő Reference Besenyő2019). To confirm the rising importance of the mutual relationship, another Russian presidential visit to Algeria occurred in 2010 when President Medvedev paid a visit to his Algerian counterpart, following the visit of President Bouteflika to Moscow two years before.

Economic cooperation

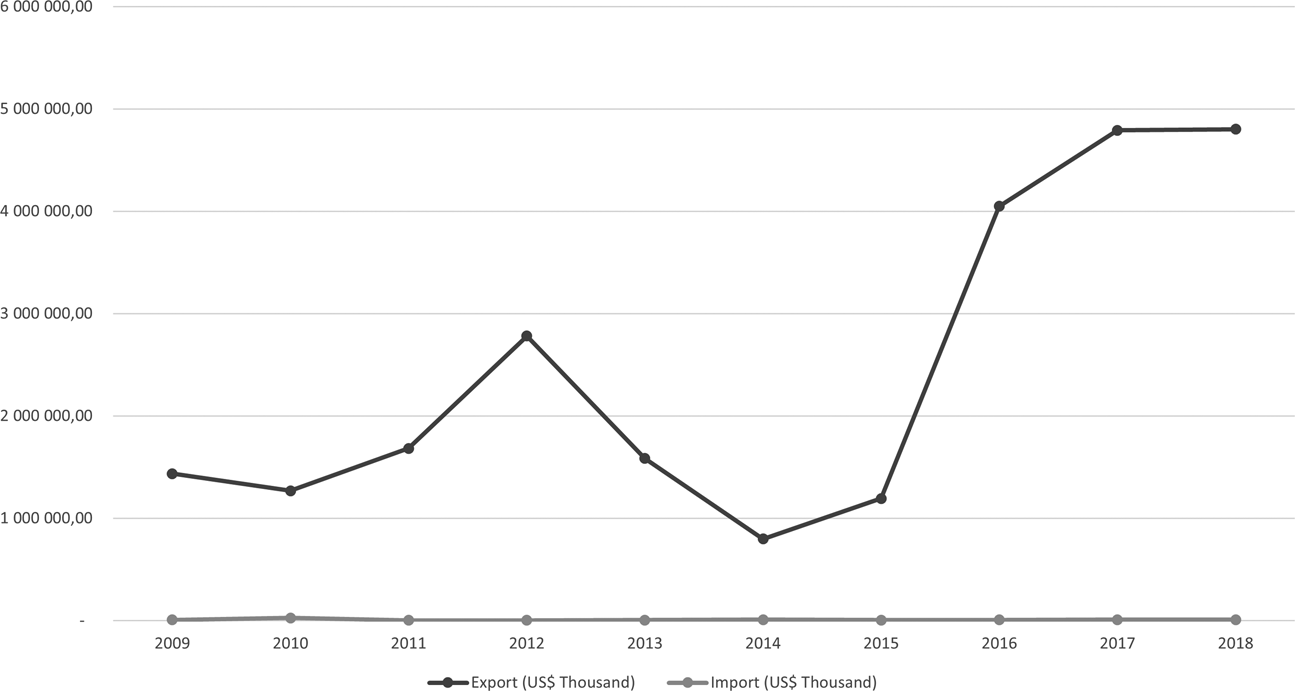

During the same period, the overall trade balance showed that while Russia's exports to Algeria were steadily increasing (with the exception of 2012–2014, when Algeria was going through an economic decline following the Arab uprising), Russia's imports from Algeria were stable and mostly negligible during the whole time. One can also notice the sharp U-turn in Russia's exports after 2014 (the US and EU sanctions). Their value over 2014–2018 alone increased five times. As a consequence, Russia became Algeria's seventh largest importer in 2017 (latest data available; see Figure 2). Regarding the commodity structure, in 2018, the largest shares of Russia's exports to Algeria were in manufactured goods (including military products), followed by small shares of machinery and transport equipment, fuels and food. On the other side, vegetables and raw materials were the main items in Russia's imports from Algeria (WITS 2020).

Figure 2 Russia's trade with Algeria in 2009–2018 (US$ thousands). Source: WITS (2020).

Energy sector

The energy sector has become the major focus of Russian investment in Algeria over this period. To name a few examples, since 2008 the Russian Gazprom has been cooperating with the Algerian Sonatrach on exploration and extraction of hydrocarbons in the El Assel area (Gazprom 2020). A consortium of Russian companies, Rosneft-Stroytransgaz, carried out a contract for the exploration and development of the Gara Tisselit block in the Illizi province. In 2019, Russian Transneft extended a contract with Algerian Sonatrach for cooperation in the areas of non-destructive testing and improving the safe operation of pipeline infrastructure (Transneft 2019). And most recently, Lukoil also indicated its willingness to enter the Algerian market when signing a Memorandum of Understanding with Sonatrach in May 2020, aiming to discuss possible joint investment in oil and gas exploration and extraction (RCC 2020).

Nuclear energy

In 2014, both countries signed an agreement on cooperation in nuclear energy, opening a pathway to possibly construct a nuclear power plant in Algeria. Simultaneously, similar agreements have been concluded between Algeria and other partners such as China, Argentina, France and the USA (NBN 2018). In 2016, Rosatom and the Algerian Atomic Energy Commission signed a Memorandum of Understanding for cooperation in the field of peaceful use of atomic energy. Beside the possibility of building a nuclear power plant, the memorandum envisages collaboration in related fields such as nuclear safety, staff training or the education of Algerian students in Russian universities (Made in Russia 2016). The last round of high-level meetings occurred during the Sochi Africa–Russia Economic Summit in 2019 when President Putin, together with the Director General of Rosatom, met Algerian President Tebboune. So far, there has been no clear outcome.

Military cooperation

Between 2009 and 2018, Russia's military exports to Algeria were the highest among African countries, accounting for US$8.087 billion. For Russia, Algeria is the third largest arms importer after China and India. And for Algeria, Russia is the No. 1 arms supplier (67% of its arms imports in 2015–2019 were from Russia). It is worth mentioning that the North African region increased military spending in 2015–2019, accounting for 74% of all African arms imports in this period. Algeria itself recorded 79% of North African arms imports, which made it the world's sixth largest arms importer in 2015–2019 (SIPRI 2020). The increased demand is caused by the persisting tensions with neighbouring Morocco, and conflicts in neighbouring Mali and Libya.

Development cooperation

Data on development cooperation with Algeria are very limited. To the best of our knowledge, scholarships for Algerian students and debt relief were the main instruments used. In 2006, Russia wrote off US$4.7 billion of Algerian debt. In return, Algeria promised to purchase military goods from Russia for the same amount (Rossijskaya gazeta 7.10.2010). Interestingly, the number of Algerian students in Russia is the lowest among the compared countries (less than 1,000 in 2019), but they benefit the most from government scholarships (110 students in 2019). Both numbers have been rising since 2013, the first year for which data are available (MSHE Reference Laaroussi2020).

Russia and Morocco: re-emerging partners with Algeria at the back

Russian–Moroccan relations have a long history, dating to Sultan Mohammed III bin Abdullah who signed a peace treaty with Empress Catherine the Great in the late 18th century. Since the country's independence, Morocco has been an important trading partner in Africa for the Soviet Union, especially in the energy and mining sector. With Soviet financial and technical support, the Jerada thermal power station, the Al Wahda hydroelectric complex, the Moulay Youssef hydropower plant and the Mansour Ed Dahbi hydropower plant were built in Morocco (Zherlitsina Reference Zherlitsina2015b). However, the still unresolved issue of the Sahara, an ongoing dispute that hampers relations not only between Morocco and Algeria but also with their allies, has left a negative influence on relations with the Soviet Union, and Russia, respectively. For this reason, the relationship was put on hold in 1980 when the Soviet Union openly supported the Polisario movement, calling for the independence of the Sahara from the Moroccan reign, for which King Hassan II consequently announced that both countries were ‘at war’ (Sheldon Reference Sheldon1980). The relationship only resumed with his son King Mohammed VI. However, the issue of the Sahara still plays a crucial role and represents one of the major motivations of Morocco to actively re-engage with Russia, a permanent member of the UN Security Council which discusses and votes on many resolutions related to this territorial dispute.

Diplomatic level

The rapprochement of both countries has been reflected in numerous high-level visits. These started in 2002 when King Mohammed VI visited Moscow for the first time and invited President Putin for a reciprocal visit. This happened four years later, 47 years after his Soviet predecessor Leonid Brezhnev visited Morocco for the last time. To show the rising significance of Russia for Moroccan foreign policy, the king revisited Moscow in 2016. On this occasion, a significant deal on strategic partnership between both countries was signed. In 2017, when Prime Minister Medvedev was in Rabat, another agreement, this time to enhance cooperation in military, security, economic and political areas was concluded. Medvedev marked this as a starting point of a new phase of mutual relations. ‘Morocco remains [Russia's] strategic partner in the Arab world and Africa in general’, noted Medvedev (Middle East Monitor 12.10.2017).

However, the reality is slightly more complicated. The rising numbers of Russian official visits to Morocco indicate that Russia has an increased interest in the country, but since the timing of these visits often coincides with visits to neighbouring Algeria, it suggests that for Russia balancing relations between both countries poses a real challenge. While Russia remains the main military supplier to Algeria (and not so to Morocco) and expands its influence in the Algerian gas and oil industry, so crucial for Russia's foreign policy interests, Morocco has recently attempted to play off the conflicting interests between Washington and Moscow by pushing for greater support from Russia for the Sahara issue (Laaroussi Reference Laaroussi2019). Morocco felt that the US support had rather faded with the Donald Trump administration and hoped that Russia can help to find a solution to the conflict.Footnote 1 From the Russian perspective, Morocco's recent economic dynamics and willingness to cooperate in many areas ranging from military to fisheries and the energy sector represents an interesting opportunity to re-engage. Not surprisingly then, Morocco (as well as Egypt) was invited to sign an economic cooperation memorandum to strengthen relations between Morocco and the Euroasian Economic Union (Maroc.ma 28.9.2017).

Economic cooperation

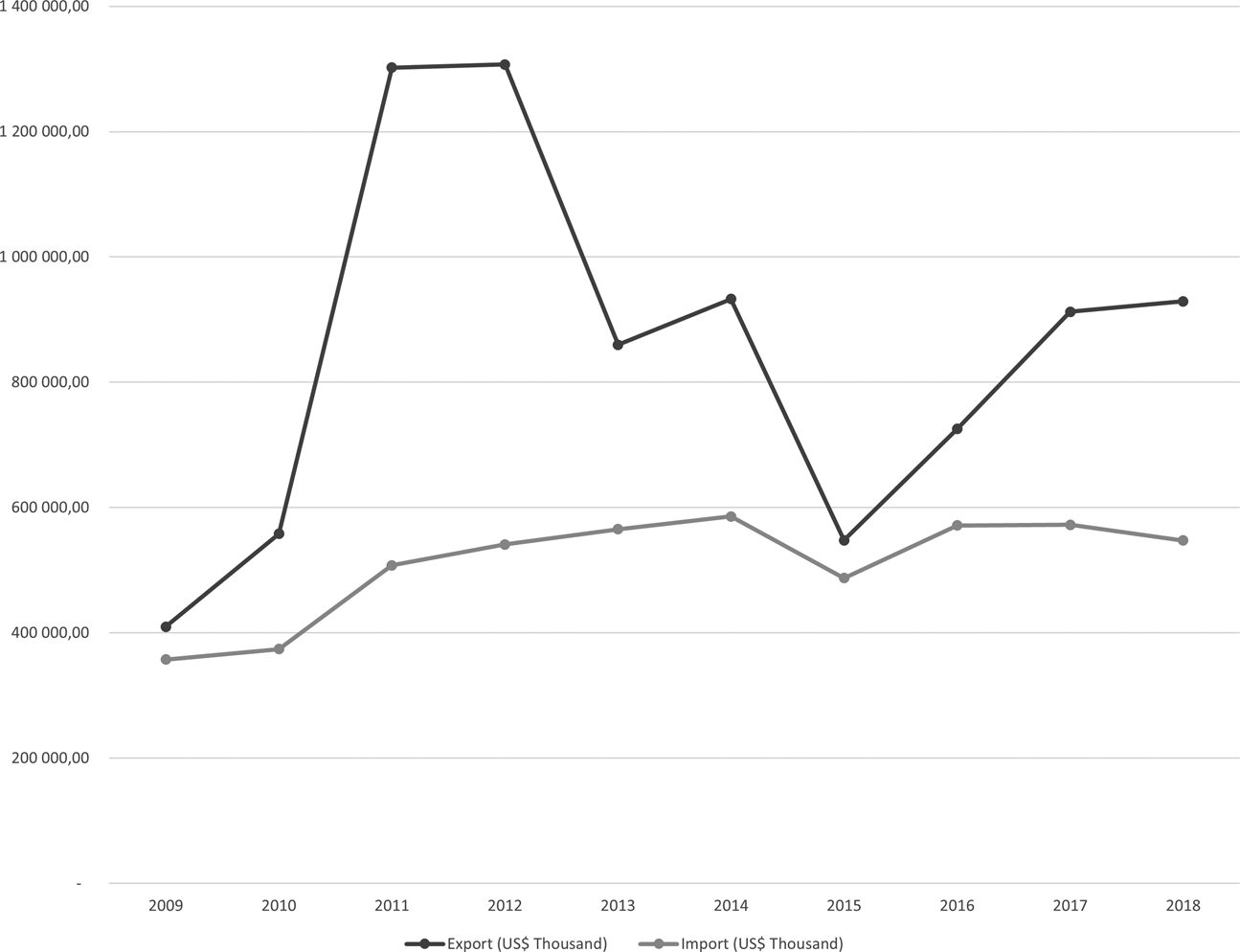

Compared with Egypt and Algeria, Morocco is a far smaller trading partner for Russia. Moreover, the trading patterns between both countries show a slightly different path. First, the mutual trade has increased in volume only slightly over the last 10 years. This was mainly due to a significant drop in Russia's exports to Morocco in 2010–2015. Second, Morocco is the only country which recorded significantly growing exports to Russia. Although the structure consists mostly of agriculture and mining, it could be considered as a success for Morocco. Russia's exports to the country are more diversified with fuels, manufactured goods, chemicals and food among the items of highest value (WITS 2020). But what unites Morocco with other countries is the U-turn recorded in Russia's exports since 2015 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Russia's trade with Morocco in 2009–2018 (US$ thousands). Source: WITS (2020).

One of the key sectors of Russian–Moroccan economic cooperation is marine fishery. In 2002, Russia and Morocco pronounced their determination to strengthen collaboration in this area (Fishnews 28.1.2019). Subsequently, Russia was granted a quota of 100,000 tons of fish against a compensation of US$5 million (Novaya Gazeta 25.8.2014). The king's visit to Russia in 2016 reaffirmed the desire of both countries to implement joint fishing projects. The creation of joint ventures, as well as the training of experts in specialised institutions was agreed upon (Fishnews 28.1.2019). Consequently, in 2019, Russian vessels were granted an increased annual quota of 140,000 tons of fish (Fishnews 20.2.2019). A new agreement between Russia and Morocco is currently ready to be signed; Russian fishermen will have the opportunity to fish in Moroccan waters for four more years (Shestakov Reference Shestakov2020).

Energy sector

Cooperation in the energy sector was one of the main issues discussed during the meeting between President Putin and King Mohammed VI in March 2016. By signing the Statement on the Extended Strategic Partnership, Russia and Morocco confirmed their interests to strengthen cooperation in this sector, most notably in liquefied natural gas (LNG) supplies, the construction of gas infrastructure, hydrocarbon exploration, construction and operation of electricity generation facilities, as well as renewable energy sources (Neftegaz 16.3.2016). In 2017, Minister of Energy Alexnader Novak announced that Russian companies Gazprom and Novatek were ready to participate in the implementation of large projects in Morocco, which were to include a regasification terminal, pipelines and energy generation (TASS 21.9.2017). However, these projects are at a standstill (Finmarket 10.6.2019). In December 2019, a Memorandum of Cooperation between Transneft and the National Office of Hydrocarbons and Mines of the Kingdom of Morocco (ONHYM) was signed in Rabat. The document aims to develop cooperation in the field of hydrocarbon transportation and the maintenance of related infrastructure (Transneft 2019). For Morocco, the development of the energy sector is crucial as the economy grows and so too does the demand for energy. The Moroccan delegation attending the Russia–Africa summit in Sochi in 2019, headed by Prime Minister Saad-Eddine El Othmani, was not surprisingly then accompanied by Minister of Energy and Mines Rabbah and numerous delegations consisting primarily of representatives of the mining and energy sector, indicating Morocco's primary economic interest in cooperation with Moscow.

Nuclear energy

In 2017, when Prime Minister Medvedev met Prime Minister Othmani in Rabat, among other things, a Memorandum of Understanding between Rosatom and the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Sustainable Development for the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy was signed (The Russian Government 2017). However, since then, no further major steps have been taken. Morocco considers nuclear energy a ‘long-term alternative to meet the country's future needs’ (IAEA 2017). Therefore, another scope for cooperation could possibly open up here.

Military cooperation

Unlike Egypt and Algeria, Morocco spends far less money on the military. And unlike both countries, its share in the world's military imports decreased in 2015–2019 in comparison to 2010–2014 (SIPRI 2020). For Russia, there is another very significant difference – the vast majority of Moroccan military imports come from the USA (91% in 2015–2019). Imports from Russia are almost negligible. In 2015, for example, Morocco received 60 fighting vehicles from Russia (Saaf Reference Saaf2016: 18). However, this does not mean that Russia would not be interested in changing this status quo. This can be proved, for example, by a visit from the Russian Armed Forces in Rabat, coming at a time when Morocco made efforts to set up a local military industry through joint ventures with foreign companies specialising in the manufacture of weapons (Morocco World News 22.6.2019). It is important to note that Morocco has recently intensified its military purchases, aligned with its plan to ‘attain regional military supremacy’ (Morocco World News 24.9.2020).

Development cooperation

As in the previous cases, there is not much evidence for development cooperation with Morocco. We notice that Moroccans also benefit from Russian ‘export of education’. During the Soviet era, 5,000 Moroccan students received their education in the Soviet Union (Zherlitsina Reference Zherlitsina2015b). Today, around 2,500 Moroccan students study in Russia, of which 42 (2018) study under a scholarship scheme (MSHE Reference Laaroussi2020).

CONCLUSIONS

The aim of this article was to analyse Russia's latest return to Africa. In particular, we were interested to disclose to what extent Russia has abandoned its traditional tools of cooperation and shifted to more ‘smart’ ones. Our interest was also to explore motivations on both sides for the rapprochement. The article was built on case studies of the three African countries – Egypt, Algeria and Morocco – which have the largest trade volume with Russia.

Our results show that for Russia, Africa has regained its significance mostly in building new alliances in energy security and defence, traditional areas of Russia's cooperation. In particular, this applies to North Africa. Russia has recently become the largest arms supplier to Africa, with Algeria and Egypt being the largest importers. Based on numerous arms deals signed recently, this trend will most likely continue. Beside military sales, Russia has engaged in numerous energy projects across all three analysed countries. To attain the goals, Russia has significantly intensified the use of ‘smart’ tools such as development cooperation and ‘export of education’ in particular. Available data indicate that mostly in energy policy this proves to be an efficient instrument.

As North Africa intersects the rising interests of Russia in Africa and the Middle East, it comes as no surprise that all three analysed North African countries have become Russia's largest trade partners in Africa. The mutual trade is unbalanced though, with Russia's dominance in (military) exports. The recent US and EU sanctions imposed on Russia and at the same time Russia's attempts to increase the geopolitical role of the newly established Euroasian Economic Union most likely contributed to the fact that mutual trade has significantly increased since 2015. But we should not forget that all three countries represent for Russia important geopolitical and geostrategic partners. Egypt in pursuing Russia's rising interest in the Middle East and also in North Africa, Algeria has gained a new strategic position in Russia's foreign energy policy aiming to exert pressure on Europe in its energy dependency, and Morocco, despite posing quite a challenge for Russia due to the persisting territorial dispute with Algeria, showed its willingness to cooperate in many areas (including military and energy) which has become appealing for Russia to re-engage and increase its role in the region.