Theory Tangles

‘Film-Music Theory’ is the obvious title for this chapter, but it may also mislead. Its simplicity suggests that there is something we can call ‘film-music theory’, an established body of thought a survey can chart. But arguably there is not, and the first thing to do is to identify some of the blank areas on the map of film-music theory, and some of the obstacles that stand in the way of colouring them in.

The least problematic word in the title is ‘music’, but it, too, hides questions, gaps and blind spots. Can film-music theory limit itself to music, or is music so closely interwoven with other film sound that they are one object for theory? Michel Chion criticized the idea with the formula ‘there is no soundtrack’: that just because music, speech and noises are all types of sound does not mean that they have to form a coherent whole (Reference Chion and Gorbman1994, 39–40; Reference Chion and Gorbman2009 [2003], 226–30). On the other hand, Chion has done more than most to think about film sound and music within the same theoretical horizon – a characteristic approach from the perspective of film studies, which tends to see music as a subcategory of film sound. It is a valid hierarchy, but it can obscure the specifics of music in film. Musicologists, on the other hand, tend to treat music as a thing unto itself, though one at times linked to other film sound. A minor question about the relationship of music and sound in film is whether we always know which is which; an example such as Peter Strickland’s Katalin Varga (2009), with its tightrope walk between musique concrète and sound design, shows how that ambiguity can become creatively fertile (see Kulezic-Wilson Reference Kulezic-Wilson2011 and J. Martin Reference Martin2015). Uncertainty regarding the sound–music relationship affects this chapter too; depending on the context, it sometimes considers both and sometimes focuses on music.

Some kinds of music in film have been more thoroughly theorized than others: the scarcity of systematic discussion of pre-existing music in film is the most obvious example. The most comprehensive study is by Jonathan Godsall (Reference Godsall2013); there is work on ‘classical’ music in film (for example, Keuchel Reference Keuchel2000 and Duncan Reference Duncan2003), and on directors known for their use of pre-existing music, such as Stanley Kubrick, Jean-Luc Godard and Martin Scorsese (see Gorbman Reference Gorbman and Goldmark2007; Gengaro Reference Gengaro2012; McQuiston Reference McQuiston2013; Stenzl Reference Stenzl2010; Heldt et al. Reference Heldt, Krohn, Moormann and Strank2015). Another gap opens up if we change perspective and look at music not as a functional element of film. While it undoubtedly is that, a focus on function overlooks the fact that film has also been a major stage for the composition, recycling, performance, contextualization and ideological construction of music. It would be a task not for film musicologists, but for music historians to give film music a place in the story of music in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

The word ‘film’ is more of a problem. In the rapid expansion of screen-media musicology over the last generation, from the fringes of musicology and film studies to a well-established field with its own journals, book series, conferences, programmes of study, etc., music in the cinema has become an almost old-fashioned topic, at least from the vantage point of those working on music in television, in video games, on the internet, in audiovisual art and so on. (See Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Gorbman and Vernallis2013 for a survey.) Yet even if this were an old-fashioned Companion to Film Music, it would still need to consider the problem: what we mean by ‘film’ is becoming fuzzy, and what film musicology has considered in depth or detail is less than what one can now categorize as film. Most of us have an ostensive idea of a ‘film’ – a narrative feature film, around two hours long, shown in a cinema – and most film musicology deals with such films. Yet films have had a second home on television since the 1950s; most of us have seen more movies on the box via direct broadcasts or video than in the cinema. The involvement of television broadcasters in film production means that this is not just a secondary use, but is built into the economic foundations of filmmaking. And what about music in TV films – is it within the remit of film musicology or that of the emerging field of television-music studies? And where in the disciplinary matrix are we when we flip through the TV channels and stumble upon the movie Star Trek (2009) and then upon an episode of the television series Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987–94)? Multimedia franchises are yet another solvent eating away at ‘film’; in such a world, the idea of film musicology as a separate field may have had its day. Moreover, with the digital shift in filmmaking and exhibition, the very term ‘film’ has become anachronistic. (‘Movie’ has always been more telling, and it may be only linguistic pusillanimity that has kept it from becoming academically common.) Digital technology drags film out of its former home in the cinema and transforms it into a dataset fit for an increasingly diverse multi-platform media world.

On the other side of the methodological problem, much of what we can see and hear in the cinema has been largely ignored by film musicology: short films, abstract and other experimental films, documentaries, adverts, trailers and so on. There is literature on cartoons (see, for example, Goldmark Reference Goldmark2001 and Reference Goldmark2005; Goldmark and Taylor Reference Goldmark and Taylor2002; Jaszoltowski Reference Jaszoltowski2013), but other forms have languished in the shadows. Music in advertising has been studied more from the perspective of television – understandable given its role in the economy of the medium (see Rodman Reference Rodman2010, 77–101 and 201–24; B. Klein Reference Klein2010) – though most insights translate to cinema adverts; music in documentaries has only produced a smattering of studies (Rogers Reference Rogers2015 is the most substantial, though ‘rockumentaries’ and other music documentaries have found interest: see T. Cohen Reference Cohen2009; Baker Reference Baker2011; Wulff et al. Reference Wulff, Levermann, Niemeier and Strank2010–11); and music in film trailers and in other filmic paratexts, such as main-title and end-credit sequences, is only just emerging as a field of study (see Powrie and Heldt Reference Powrie, Heldt, Powrie and Heldt2014 for a summary and bibliography). And then there is ‘theory’, where things get more tangled. In the sciences, ‘theory’ is a relatively straightforward concept: a model of part of the world that allows us to make predictions that can be empirically tested, and where experimental falsification allows theories to be improved to become better models. This summary glosses over complications in the reality of theory formation and testing, but may help to throw art theories into relief. Art theories, too, model aspects of the world in order to explain how they ‘work’. But while the sciences have an established ‘scientific process’, a particular nexus of theory, empirical testing and reality (however idealized), that relationship is looser in the arts, where the career of theories rests on a less tidy set of circumstances: on their inherent plausibility; on their fit with other theories; on their analytical power; on their originality or their capacity to generate original interpretations; on trends and fashions in a discipline and in the wider academic landscape (especially for small disciplines such as film studies or musicology, which historically have depended heavily on ideas from elsewhere); and on political, ethical and aesthetic stances that introduce a prescriptive element to some theories that has no equivalent in the sciences.

Closest to the scientific model is the cognitive psychology of the effects of film music. (For summaries of research, see Bullerjahn Reference Bullerjahn2014 and Annabel J. Cohen Reference Cohen, Juslin and Sloboda2010 and Reference Cohen and Neumeyer2014.) Music theory is another tributary, informing how musicologists analyse the structures of music in films: harmonic structures from local chord progressions to film-spanning frameworks; metric, rhythmic and phrase structures that may affect how music relates to on-screen movement or editing; or motivic and thematic relationships. All of this is the small change of music analysis and usually goes without saying; only recently has music theory approached film musicology with more complex instruments (see Lehman Reference Lehman2012, Reference Lehman2013a and Reference Lehman2013b; and Murphy Reference Murphy2006, Reference Murphy and Halfyard2012, Reference Murphy and Neumeyer2014a and Reference Murphy2014b). A different appropriation of music theory – on the general level of music as an abstract system – is music as a metaphor for formal aspects of film, in a move away from understanding film as recording or representation of reality (see Bordwell Reference Bordwell1980), a variant of the more common metaphor of the ‘language’ or ‘grammar’ of film (for example, Spottiswoode Reference Spottiswoode1935; Metz Reference Metz1971 and Reference Metz and Taylor1974 [1968]; Arijon Reference Arijon1976).

But mostly, ‘theory’ means film theory, and the challenge it poses to film musicology is its diversity (see, for example, Stam and Miller Reference Stam and Miller2000, Simpson et al. Reference Simpson, Utterson and Sheperdson2004 and Braudy and Cohen Reference Braudy and Cohen2009 for anthologies; Elsaesser and Hagener Reference Elsaesser and Hagener2010 for an unusual account; and Tredell Reference Tredell2002 for a historical overview). There is media theory, dealing with technological and communicative, but also institutional and economic aspects of cinema; there are theories of the ontology of film, of film language, of authorship, of aesthetics, of narratology, with regard to narrative systems and with regard to the story patterns they generate; there are semiotics and pragmatics; there is genre theory; there are psychological theories on a spectrum from psychoanalytical approaches, often close to cultural theory, to empirical psychology; there are sociological theories, including engaged ‘critical’ theories; theories of performance, within film and of film; theories of film and cultural identities, and of different national and regional cinemas; theories of audiences and spectatorship, of gender, of emotion, of time and so on. There is also ‘Theory’, that ‘blend of Marxism, psychoanalysis and structuralism’ (Macey Reference Macey2001, 379) that became prominent in Anglophone film studies in the 1970s (see Buhler Reference Buhler and Neumeyer2014b for an overview of sound and music in relation to parts of Theory, and Bordwell and Carroll Reference Bordwell and Carroll1996 for critiques). The situation is complicated by the fact that theoretical thinking does not need to generate theories in a strong sense; much film-studies scholarship that does not aim to theorize as such still contributes to the initiative: to the development of ideas that may eventually be adopted in theories.

How film-music theory might fit into this jagged panorama (or widen its frame) is not yet clear. Is it another glass pebble in the theoretical kaleidoscope, contributing its own bit to the picture? Or should music be absorbed into film theories and become as integral to them as music often is to film? In the audiovisual art of film, sound is part and parcel of all these theoretical perspectives, and music intersects with most of them. So far, sound has played only a peripheral role in film studies, and film musicology has mostly been a thing apart, a situation to which musicologists are accustomed, separated as they are from colleagues elsewhere in the academy by musical notation and theory and its arcane symbols, concepts and terminology. However cosy that may be at times, it is also dangerously isolating. If film musicology wants to be productive in film studies, it has to grow into it, and film-music theory into film theory. That puts an onus on film scholars to accept it as something with which they need to engage if they want to do their job properly, and an onus on film musicologists to make themselves understood. That does not preclude studies reliant on expert musical knowledge – they make the widening of the horizon possible. But the arcana need to serve a purpose, and the results need to be communicated so that others can use them.

Theories in History

The challenge for film-music theory has been exacerbated by the unstable currents of artistic and academic developments. Film is only 120 years old, and sound film (as a commercially viable mass medium) less than 90, and beyond the aesthetic change that is a constant in the history of any art, revolutions in technology and media mean that film has been a moving target for theory. Film studies as an academic concern is only two generations old and has imported many ideas (and scholars) from other disciplines. That influx may have been stimulating, but there has been scant time for a disciplinary identity to emerge, much less so for a peripheral topic such as music. And while there have been major studies of film music since Kurt London’s in Reference London1936, for decades these were few and far between; only since the 1980s has development picked up and formed a new subdiscipline (though whether one subordinate to film studies or to musicology is not clear). That the birth of modern film musicology is often identified with the special issue ‘Film/Sound’ of Yale French Studies (Altman Reference Altman1980) proves the point of the heterogeneous disciplinary history that makes film-music theory precarious; that the title of the special issue omits music – though five of its articles are about it – shows its peripheral place in film studies at the time (and to this day).

This chapter can only offer a whistle-stop tour of some milestones in the uncertain unfolding of film-music theory and try to trace how questions and ideas are threaded through the history of such theory. This neither amounts to a history nor a metatheory of film-music theory; given the sketchy nature of the matter, the chapter cannot be but a sketch itself.

Chasing After Film: The Accidental Theory of Silent-Film Music

Until about two generations ago, the honour of theory was accorded to practices understood as (high) art. But film started life not as art; it began as technological sensation and spectacle, and continued as (sometimes quite cheap) entertainment. During the first quarter of the twentieth century, music in silent film was theorized only in passing, as a by-product of the practice of making music for film. A venue for such accidental theorizing was the development in the 1910s of organized collections of titles, incipits or stock music deemed suitable for film accompaniment, such as the Kinotheken series in Germany (see Altman Reference Altman2004, 258–65, for their early development). The implicit assumptions that governed their categories for music could be analysed as a cryptotheory of the semiotics of film music in its own right and the introductions to such collections often also contain, intentionally or not, nuggets of nascent film-music theory. ‘The pianist should create a tone poem that forms a frame, as it were, for the picture’, advises one compiler (True Reference True1914, 2), and what can be understood as a prod for cinema pianists to take pride in their work can also be read as an acknowledgement of a key function of music in film: to bind the fragmented structure of shots and cuts in the visual images into a whole.

The purpose of such collections made a critical view unlikely; introductions usually describe what their authors see as best practice without judgement. An example is Ernö Rapée’s Reference Rapée1925 Encyclopedia of Music for Pictures. What Rapée describes would, two decades later and translated into the conditions of sound film, provide the aim for the sarcastic critique of the first chapter of Theodor Adorno’s and Hanns Eisler’s Composing for the Film (Reference Adorno and Eisler2007 [1947]): music provides setting, atmosphere or emotion; Chinese music is for Chinese characters and English music for English ones; characters have themes (Rapée does not yet call them leitmotifs) chosen according to a system of musical clichés: the music shadows the film and does what it does in the most obvious way. (See excerpts from Rapée in Cooke Reference Cooke2010, 21–7; Hubbert Reference Hubbert2011, 84–96; and Wierzbicki et al. Reference Wierzbicki, Platte and Roust2012, 39–52.)

A counter-example is Hans Erdmann, Giuseppe Becce and Ludwig Brav’s Allgemeines Handbuch der Film-Musik, which frames its ‘thematic scale register’ – classifying pieces of music by a multi-level system of moods – with a critique of silent-film practice and its ‘style-less potpourris’ of worn-out clichés (Reference Erdmann, Becce and Brav1927, vol. 1, 5). At the end of silent cinema, Erdmann, Becce and Brav justify their advice for matching music to film with a rudimentary version of what James Buhler (taking his cue from Francesco Casetti) calls an ‘ontological theory’ of film music: one that ‘attempted to determine [the] nature and aesthetic possibilities’ of film music by trying to determine the nature of film itself, an attempt that would become important in the transition to sound film (Reference Buhler and Neumeyer2014a, 190–4). Erdmann, Becce and Brav ‘explain’ the integral role of music in film by locating film between drama and music: to the former it is linked by ‘the representational objective, the material content’, to the latter by its ‘wordlessness’ that makes it ‘averse to pure thought’ (Reference Erdmann, Becce and Brav1927, vol. 1, 39; my translation). While the reasons for music’s integral role in film were historical rather than aesthetic – music was common in other forms of dramatic storytelling, and it was part of the performance contexts in which film first appeared – it was still tempting to justify it by looking for a common denominator of film and music. Carl Van Vechten, for example, in 1916 found it in comparing the wordless action of film to ballet: ‘and whoever heard of a ballet performed without music?’ (Reference Van Vechten and Wierzbicki2012 [1916], 20); and the idea of movement linking images and music is still used by Zofia Lissa (Reference Lissa1965, 72–7). The flipside of Erdmann, Becce and Brav’s critique is their call for coherence: ‘incidental music’ (that is, music as diegetic prop) should be historically credible, and ‘expressive music’ should not ‘chase after film scenes like a poodle’, but shape the emotional trajectory of the film (Reference Erdmann, Becce and Brav1927, 46); music is understood to possess its own formal and stylistic integrity that combines with the images to form the film. (For background to the Handbuch, see Comisso Reference Comisso2012 and Fuchs Reference Fuchs, Tieber and Windisch2014.) The ‘style-less potpourris’ were still an issue when Rudolf Arnheim, writing in 1932, bemoaned that music chasing after film scenes coarsened their effect because it had not been part of the balancing of continuity and contrast at their conception (Reference Arnheim2002 [1932], 253–4).

Counterpoints: The Challenge of Sound Film

Silent film is more musical than sound film, but the challenge for theorists of early sound film was that it is musical in a different way. The sound of a silent film is not part of the film text, but is added in situ as part of the performance of the film (even though the brain may combine the visual and auditive layers into the experience of a whole). Sound film offered the possibility for sound and music to disappear into the images: ‘realistic’ diegetic sounds could be understood as their counterpart, and music lost its visible presence in the cinema and could become ‘unheard melodies’ (Gorbman Reference Gorbman1987). One may wonder what would have happened had Edison succeeded and film had been furnished with synchronous sound from the start: would film theory have taken its cues from theories of drama? Probably only up to a point, as its patchwork of shots and cuts gives film a fundamentally different structure. But film theory carried the origins of the medium with its silent images and musical layer across the transition to sound, most obviously in the idea of film as an essentially visual art. That in 2003 Chion still felt the need to blow the trumpet of sound with the book title Art sonore, le cinéma (published in English as Film, a Sound Art, 2009) shows the long shadow of the idea. (A music-specific variant of the problem is found in Noël Carroll’s ‘Notes on Movie Music’, which set music apart from ‘the film’ and categorized both as complementary ‘symbol systems’ [Reference Carroll1996, 141].)

For film theorists, the transition to sound sharpened the question of what film was good for – a question not so much about film’s ontology as one about its aesthetic potential. The technical recording process involved in most cinematic images (and sounds) made it tempting to ascribe to film a unique capacity for capturing reality – the view of mid-century theorists such as André Bazin, for whom ‘the guiding myth’ of cinema is ‘an integral realism, a recreation of the world in its own image, an image unburdened by the freedom of interpretation of the artist’ (Reference Bazin and Gray2005 [1967], 21), or Siegfried Kracauer, who distinguished between ‘basic and technical properties of film’ and saw as its basic property that film is ‘uniquely equipped to record and reveal physical reality’, while of the technical properties ‘the most general and indispensable is editing’ (Reference Kracauer1961, 28–9).

For Bazin, sound film ‘made a reality out of the original “myth”’, and it seemed ‘absurd to take the silent film as a state of primal perfection which has gradually been forsaken by the realism of sound and color’ (Reference Bazin and Gray2005 [1967], 21). But for theorists who had grown up with silent film, its relative lack of realism focused attention on ‘the freedom of interpretation of the artist’ enabled by the ‘technical properties’ of film – an achievement threatened by the illusion of realism which synchronous sound made that bit more insidiously perfect. And so Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin and Grigori Alexandrov feared that the realism of sound film might lead to sterile ‘“highly cultured dramas” and other photographed performances of a theatrical sort’ that would damage the aesthetic of montage which early Soviet films had developed, because ‘every adhesion of sound to a visual montage piece increases its inertia as a montage piece, and increases the independence of its meaning’; they called instead for an ‘orchestral counterpoint of visual and aural images’ (Eisenstein et al. Reference Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Alexandrov, Leyda, Weis and Belton1928, 84); Arnheim warned that sound film was inimical to the work of ‘film artists … working out an explicit and pure style of silent film, using its restrictions to transform the peep show into art’ (Reference Arnheim1957, 154); and Béla Balázs wrote that sound film was still a ‘technique’ that had not ‘evolved into an art’ (Reference Balázs and Bone1970 [1952], 194–5). Such scepticism was justified by film’s rapid move towards using speech and noises primarily in a ‘realistic’ manner (though exceptions such as René Clair’s films in the early 1930s show that creative solutions were possible, as did cartoons, which were freed from some of the expectations of realism).

One consequence of the shock of synchronized sound was to make theorists map how such sound could relate to images. There were two crucial issues: the degree to which sounds could be understood as realistic with regard to images, and the degree to which images and sounds converged or diverged conceptually. True to the title of the book, the most elaborate system was developed in Raymond Spottiswoode’s Grammar of Film (Reference Spottiswoode1935, 48–50 and 173–96). Spottiswoode places sound on different polar scales: it can be realistic or unrealistic in kind or intensity; realistic sound can have an on-screen or off-screen source (the latter he calls ‘contrapuntal’ sound; 174–8); sound can be objectively unrealistic (voiceover or nondiegetic music) or subjectively unrealistic (representative of a character’s perception). The second distinction is that between ‘parallel’ and ‘contrastive sound’: sight and sound ‘convey[ing] only a single idea’ or ‘different impressions’ (180–1).

Spottiswoode’s first set of distinctions is, in different versions and with a variety of terms, still part of the toolbox of film musicology: diegetic and nondiegetic music; on-screen and off-screen music; music representing objective reality or subjective perception (from Chion’s ‘point of audition’ [Reference Chion and Gorbman1994, 89–94] to ‘internal’ or ‘imagined’ diegetic music, ‘metadiegetic music’ and, conceptually wider, ‘internal focalization’; for a summary see Heldt Reference Heldt2013, 119–33). Distinctions added later are, for example, that between on- and off-track music (between music heard and music implied by other means; Gorbman Reference Gorbman1987, 144–50), and that between on- and off-scene diegetic music (between music that is diegetic with regard to the storyworld overall and music that is diegetic in a specific scene; Godsall Reference Godsall2013, 79–82), and temporality is introduced with the concept of displaced sound and music (see Bordwell and Thompson Reference Bordwell and Thompson2010, 280–98; Buhler et al. Reference Buhler, Neumeyer and Deemer2010, 92–113; Heldt Reference Heldt2013, 97–106).

Spottiswoode’s distinction between parallel and contrastive sound also had its career in film-sound theory (with ‘contrast’ often replaced by ‘counterpoint’, building on Eisenstein, Pudovkin and Alexandrov’s audiovisual ‘counterpoint’; Nicholas Cook returns to ‘contrast’ [Reference Cook1998, 98–106]; see also Chion Reference Chion and Gorbman1994, 35–9). Whatever the terms, the distinction underlies Eisenstein’s statement that ‘synchronization does not presume consonance’ and takes account of ‘corresponding and non-corresponding “movements”’ (Reference Eisenstein and Leyda1942, 85), allowing for the complex system of image–sound relationships sketched in The Film Sense; it is there in Adorno’s and Eisler’s ‘music … setting itself in opposition to what is shown on the screen’ (Reference Adorno and Eisler2007 [1947], 26–8); it informs Kracauer’s distinction between parallelism and counterpoint (sound and images denoting the same or different ideas), perpendicular to that between synchronous and asynchronous sound (sound matching or not matching what we see; Reference Kracauer1961, 111–15 and 128–32). (For further discussion and examples of the idea, see Gallez Reference Gallez1970.) Lissa uses both distinctions more flexibly: she allows for a fuzzy borderline between synchronism and asynchronism via ‘loosened-up’ forms of mutual sound/image motivation that pull them apart ‘temporally, spatially, causally, emotionally’. Audiovisual counterpoint for her covers a range of options: music linking strands on the image track; music dynamizing static images; music commenting on images or characterizing protagonists; music adding ‘its own content’ to images; music anticipating a scene; music in counterpoint to speech and noises; and music in Eisensteinian montages of thesis and antithesis implying a conceptual synthesis (Lissa Reference Lissa1965, 102–6). The idea is still present in Hansjörg Pauli’s distinction between musical ‘paraphrase, polarisation and counterpoint’: music matching the ‘character of the images’; music imbuing images with an interpretation; and music contrasting with images (Reference Pauli and Schmidt1976, 104), a division he later retracted as too simplistic (Reference Pauli1981, 190). The problem with such systems is that they undersell the multi-layered complexities of sound film. Both sound and vision can consist of different strands, but whereas the use of split screens or layered images is rather rare, the layering of multiple auditive strands in more complex ways (that is to say, different combinations of dialogue, noises, diegetic and nondiegetic music at the same time) is not uncommon in film. When in a film ‘we hear one or two simultaneous sounds, we could just as well hear ten or fifteen, because there is … no frame for the sounds’ (Chion Reference Chion and Gorbman2009 [2003], 227). Furthermore, images, sounds or music can rarely be reduced to a single ‘character’, and a static model of image–sound relationships ignores the dynamic, temporal nature of both. This complexity does not preclude simplifying systems, but they need to be understood as heuristic crutches.

Another approach to ordering film music that proliferated from the 1930s onwards is to describe its functions. Lists of functions have been too many and too various to be surveyed here (early ones are discussed in Lissa Reference Lissa1965, 107–14; other examples include Spottiswoode Reference Spottiswoode1935, 49–50 and 190–96; Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer1946; Copland Reference Copland and Cooke1949, elaborated in Prendergast Reference Prendergast1992 [1977], 213–26; Manvell and Huntley Reference Manvell and Huntley1957, 69–177, and 1975, 63–198; Kracauer Reference Kracauer1961, 133–56; Gallez Reference Gallez1970, 47; La Motte-Haber and Emons Reference De la Motte-Haber and Emons1980, 115–219; Schneider Reference Schneider1986, 90–1; Chion Reference Chion1995a, 187–235; Kloppenburg Reference Kloppenburg2000, 48–56; Larsen Reference Larsen2005, 202–18; Bullerjahn Reference Bullerjahn2014, 53–74; for classical Hollywood film Gorbman Reference Gorbman1987, 70–98, and Kalinak Reference Kalinak1992, 66–110). Lissa’s list can illustrate a feature of such catalogues: their synoptic nature means that they range across the realms of different theories. Lists of functions focus on their being performed by music at the expense of their place in a particular theoretical framework. Lissa distinguishes between music underlining movement, music as stylization of sounds, music as representation of space, music as representation of time, deformation of sound material, music as commentary, music in its natural role, music expressing mental experiences, music as a basis for empathy, music as symbol, music as story anticipation and music as a formally unifying factor (Reference Lissa1965 [1964], 115–231). One of the categories, the deformation of sound material, is not a function in itself, but a range of techniques for different purposes; the others comprise aspects of the semiotics of film music, of its narratology, of its psychology and of film form.

Lists of functions are compiled not on the basis of understanding film as a super-system of formal systems – typical for neoformalist film theory associated with scholars such as David Bordwell, Kristin Thompson or Carroll (for example, see Bordwell Reference Bordwell1985; Thompson Reference Thompson1988; N. Carroll Reference Carroll1996; Bordwell and Thompson Reference Bordwell and Thompson2010) – but with regard to the making and perception of films. If we understand the former as anticipation of the latter, the two are related (though not as mirror images, because not all intentions are realised and not all perceptions anticipated), and we may see the categorization of functions of film music as part of the poetics rather than the theory of film – part of the craft of making rather than the science of analysing film. A counterpart of such a perspective is the phenomenological approach, an analysis of the experience of film music, which is an implicit part of many analyses, but has rarely been the subject of methodological discussion (Biancorosso Reference Biancorosso2002, 5–45, is the most elaborate example).

Monument Valley: Musical Monoliths in the Desert

Although early film-music theory was born of film-sound theory and the work of film theorists rather than musicologists, for most of the twentieth century not just music but sound itself became a sideline for film theory which was ‘resolutely image-bound … sound serving as little more than a superfluous accompaniment’ (Altman Reference Altman1980, 3). (Anthologies such as Stam and Miller Reference Stam and Miller2000 and Simpson et al. Reference Simpson, Utterson and Sheperdson2004 mention music on only 8 and 5 pages, respectively, out of total lengths of 862 and 1,487 pages.) For a long time, studies of film music were relatively few and were either practical primers (Sabaneev Reference Sabaneev and Pring1935); surveys of film music as a whole, made from historical as well as systematic perspectives, but without a specific theoretical aim, such as the studies of Kurt London (Reference London1936), Roger Manvell and John Huntley (Reference Manvell and Huntley1957), Georges Hacquard (Reference Hacquard1959), Henri Colpi (Reference Colpi1963), François Porcile (Reference Porcile1969) and Roy M. Prendergast (Reference Prendergast1992 [1977]); or idiosyncratic monoliths, such as Adorno’s and Eisler’s Composing for the Films (Reference Adorno and Eisler2007 [1947]) or Lissa’s Ästhetik der Filmmusik (Reference Lissa1965 [1964]).

The fame of Adorno and Eisler is indeed based on their idiosyncratic views more than on their work’s usefulness as a textbook, which it is not. In one sense, it is an adjunct to Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), a case study of ‘the most characteristic medium of contemporary cultural industry’ (Adorno and Eisler Reference Adorno and Eisler2007 [1947], xxxv); it is a polemic of two creative minds thrown by history right into the heart of the capitalist system that had occupied their thinking for many years; it is an exploration of alternatives to the Hollywood orthodoxy (using Eisler’s own film scores as counter-examples). The biting criticism of Hollywood’s ‘Prejudices and Bad Habits’ in the first chapter may be the least interesting one because it states the obvious: that much film music does what is expected of it in terms of musical style, semiotic referencing and narrative function, but does it in an unobtrusive way that relegates it to ‘a subordinate role in relation to the picture’ (ibid., 5). The book is also occasionally curiously retrospective: two of the bad habits, the attempt to justify music diegetically and the use of classical hits as stock music (ibid., 6–7 and 9), were not really relevant anymore in the mid-1940s, and many examples of scores by Eisler refer back to the early 1930s. But the chapters on musical dramaturgy, musical resources and aesthetics (ibid., 13–29 and 42–59) contain insights and ideas that show a belief in the potential of music to release ‘essential meaning’ from the ‘realistic surface’ of film (ibid., 23). Many of these insights remain unredeemed, and while film music has discovered the use of many ‘new resources and techniques’ (ibid., 21) since 1947, it has also transformed many of them into new ‘bad’ habits. The most important contribution of the book to film-music theory was perhaps that it widened the range of what ‘theory’ meant – that it need not be restricted to theorizing film music as a subsystem of the film text, but that the economic, institutional and social conditions of the making and reception of films were crucial to their structure. Even though that seems obvious, one danger of the theory-proliferation mentioned in the first part of this chapter is that theories of different aspects of film and its music do not speak to each other, and whatever one may think of Adorno’s and Eisler’s aesthetics, their attempt to intertwine sociology with the structure and style of films and their music was (and is) a salutary lesson.

Lissa’s own idiosyncratic monolith, written two decades later, takes almost the opposite tack, perhaps consciously so. Lissa ignores Adorno’s and Eisler’s lesson of socio-economic contextualization and casts music as part of film not as ‘mass culture’, but as art: a synthetic art reliant on the ‘organic cooperation of the means of different arts’ (Reference Lissa1965 [1964], 25). If Adorno and Eisler were anxious for music to become productive in film by retaining its integrity, Lissa sees its difference to the rest of the film as the potential to become an ‘integrative factor’ in the ‘dialectic unity of the layers of sound film’ (ibid., 27, 65). Through historical convention, music has become integral to film because it adds a dimension: unlike most elements of a film, music does not represent a (fictional) reality, but is a reality in its own right (though this does not apply to diegetic music, which is representational), and while the images ‘concretise … the musical structures’, linking them to specific meanings, they in turn ‘generalise the meaning of the images’ (ibid., 70). The dialectics smack of an attempt to justify music in film via an unnecessary reductive principle (there are enough films without music that work perfectly well, after all), but the idea of music as integral to a new multimedia art informs analyses of the functions of film music, of the role of form and style, of music in different genres and of its psychology that for the time were matchlessly detailed and differentiated. One idiosyncrasy of the book – at least for readers in Western countries – is that many examples are from films made in the Eastern bloc (though for the German version references to Western films were added; ibid., 6). Despite that, it is a loss that the book has never been translated into English; though its interest today may be mainly historical, for that reason alone a translation would still be worthwhile.

Becoming Film Musicology: The Constitution of a Discipline

The hearing loss of film theory eventually made way for a return to the interest in sound and music that had been integral to early sound-film theory, programmatically in the 1980 ‘Film/Sound’ special issue of Yale French Studies mentioned above. The quantity of film-music literature picked up as well, but widely read books such as Claudia Gorbman’s Unheard Melodies (Reference Gorbman1987) or Royal S. Brown’s Overtones and Undertones (Reference Brown1994) still show traces of the older, synoptic model (as does Helga de La Motte-Haber and Hans Emons’ Filmmusik in Reference De la Motte-Haber and Emons1980), though new theoretical concerns now come to the fore.

Its balancing of survey and theoretical perspectives new to film musicology made Gorbman’s film-music book the first port of call for a generation: it uses ideas from semiotics, narratology and suture theory to explain the workings of underscoring in narrative fiction films, and applies its tools to classic Hollywood as well as to René Clair and Jean Vigo. The most eye- (or ear-)catching idea gave the book its title: that the melodies of film scores usually go unheard, evading conscious audience awareness. Already Arnheim in 1932 had averred that ‘film music was always good if one did not notice it’ (Reference Arnheim2002 [1932], 253; my translation), one of Adorno’s and Eisler’s bugbears. Gorbman recasts it via the concept of suture: the idea that film needs to overcome the ontological gulf between the viewer and the story on the screen, and that it has developed ways to suture that gap, to stitch the viewer into involvement with the narrative (Reference Gorbman1987, 53–69). Visual strategies were crucial to suture theory, for example shot‒countershot sequences. Music offered another thread for the stitching of ‘shot to shot, narrative event to meaning, spectator to narrative, spectator to audience’ (ibid., 55), the more so since most viewers lack the concepts to assess critically the effects of musical techniques.

Suture is just one concept from what Bordwell ironically characterized as Grand Theory (Reference Bordwell, Bordwell and Carroll1996): the confluence of ideas from (mainly Lacanian) psychoanalysis, (post)structuralist literary theory and (post)Marxist sociology that became a major strand of film theory in the 1970s (from hereon written ‘Theory’ to distinguish this complex of ideas from the generic term). Different strands of Theory try to show how cinema – as an institution, as a technology, as a (prefabricated) experience, as a narrative medium – and the structuring and editing techniques of film create illusions: of realism, of continuity and coherence, of meaning, of authority, of subject identity and connection, illusions reducing the viewer to a cog in an ideological machine. Despite the tempting capacity of music to help bring about the quasi-dream state cinema engenders (Baudry Reference Baudry1976), music has not played a significant role in Theory, nor the latter in film musicology. (Jeff Smith [Reference Smith, Bordwell and Carroll1996] criticizes the idea of ‘unheard melodies’ with regard to Gorbman Reference Gorbman1987 and Flinn Reference Flinn1992; Buhler Reference Buhler and Neumeyer2014b discusses psychoanalytically grounded theories mainly with regard to film sound overall, with few references specifically to music.) One reason may be that film musicology discovered Theory when its heyday was coming to an end; another reason may be that musicology does not have a tradition of the ideas that informed Theory (and much film musicology was done by musicologists). The cachet of Theory has waned, together with psychoanalysis as a psychological theory, and with the socio-political ideas that had entered cultural theory with the Frankfurt School of social philosophers, Adorno in particular. Even if ‘critical theory generally understands psychoanalysis not as providing a true account of innate psychological forces … but rather as providing an accurate model for how culture shapes, channels and deforms those psychological forces’ (Buhler Reference Buhler and Neumeyer2014b, 383), the latter is not independent of the former, and Theory as a social theory is no less problematic than as a psychological one. But ideas about cinema as a dream-machine, and about sound and of music in it, may be partly recoverable in other theoretical frameworks, even if their original foundations have become weakened.

More durable may be the semiotic and narratological perspectives in Gorbman’s book. Semiotic functions of film music had long been a strand of the literature, even avant la lettre: the use of commonly understood musical codes to suggest time, place, setting, characters; the provision of an experiential context by establishing mood and pace; the interpretation of story and images by underlining aspects of them – in short, the creation, reinforcement and modification of filmic signification through music. However, semiotics are more prominent in analyses of individual films and repertoires of films, often done in DIY fashion, without an explicit theoretical framework (not necessarily a bad thing); coherent theoretical or methodological models are relatively rare. The most elaborate one, Philip Tagg’s ‘musematic’ analysis, was developed for television music (Tagg Reference Tagg2000; Tagg and Clarida Reference Tagg and Clarida2003 applies the idea to a wider range of television music); other theoretical approaches to film-music semiotics can be found in Lexmann Reference Lexmann2006 and Chattah Reference Chattah2006 (which distinguishes between semiotics as a focus on the relationship between signs and what they signify, and pragmatics as a focus on the relationship between signs and their users and contexts).

As with semiotics, narratological concepts had been applied to film music long before narratology came into play by name, chiefly in the distinction between ‘source music’ and ‘scoring’: music that has a source in the image (or suggested off-screen space) and music that has not, i.e. music on different levels of narration. Many different terms have been used for, more or less, this distinction (see Bullerjahn Reference Bullerjahn2014, 19–24 for a list), but the most common are diegetic and nondiegetic (or extradiegetic) music (see Gorbman Reference Gorbman1980 and Reference Gorbman1987, 11–30). To replace old terms by new ones needs a justification, and the obvious one is that ‘source music’ and ‘scoring’ are specific to the craft of film music, while ‘diegetic’ and ‘nondiegetic’ link into a theoretical system, developed by Gérard Genette (who borrowed diégèse from Étienne Souriau: see Genette Reference Genette and Lewin1980 [1972], 27), but also common in film studies, and related to the story/discourse distinction more common in literary studies (see Heldt Reference Heldt2013, 19–23 and 49–51 for the terminological background). Film musicology has rarely ventured beyond the basic diegetic/nondiegetic distinction. Gorbman applied Genette’s term ‘metadiegetic’ to music which might be interpreted as being in a character’s mind (Reference Gorbman1987, 22–3), problematic because the embedded narration to which Genette applies it differs from Gorbman’s usage (see Heldt Reference Heldt2013, 119–22); and Jerrold Levinson (Reference Levinson, Bordwell and Carroll1996) tried to make Wayne Booth’s concept of the implied author useful for film musicology, though he misappropriates the idea (see Heldt Reference Heldt2013, 72–89). Systems of levels of narration extend further, however, from historical authorship via implied authorship and extra-fictional narration to nondiegetic, diegetic and metadiegetic levels, and also take in the differentiation between objective and subjective narrative perspectives, as in Genette’s concept of ‘focalisation’. (For examples of such systems, see Genette Reference Genette and Lewin1980 [1972], 227–37; Chatman Reference Chatman1978, 146–95; Bal Reference Bal2009, 67–82; and Branigan Reference Branigan1992, 86–124; see Heldt Reference Heldt2013 for an application to film music.) How music relates to most of these concepts has not been explored, and much less other elements of film narratology, such as the relationship of music to temporal ordering with regard to aspects such as filmic rhythm, ellipses, anticipation and retrospection (see, for example, Chatman Reference Chatman1978, 63–79; Bordwell Reference Bordwell1985, 74–98; Bal Reference Bal2009, 77–109), to historical modes and norms of narration (Bordwell Reference Bordwell1985, 147–55), or to the distinction between narration and monstration (Gaudreault Reference Gaudreault and Barnard2009 [1988]), important for film because the relationship is very different from that in literature, and most filmic ‘narration’ consists in the organization of access to information rather than the literal telling of a story.

The other hitch in the relationship of film musicology and narratology has been that film musicologists have worried about the diegetic/nondiegetic distinction more than scholars in other disciplines. Some have explored how music can blur the distinction, or how it can transition between categories (for example, Neumeyer Reference Neumeyer1997, Reference Neumeyer2000 and Reference Neumeyer2009; Buhler Reference Buhler and Donnelly2001; Biancorosso Reference Biancorosso2001 and Reference Biancorosso2009; Stilwell Reference Stilwell and Goldmark2007; Norden Reference Norden2007; J. Smith Reference Smith2009; N. Davis Reference Davis2012; Yacavone Reference Yacavone2012). Others have questioned the usefulness of the concepts as such, suggested alternatives or posited that they have been misused (for example Kassabian Reference Kassabian2001, 42–9, and Kassabian Reference Kassabian and Richardson2013; Cecchi Reference Cecchi2010; Winters Reference Winters2010 and Reference Winters2012; Merlin Reference Merlin2010; Holbrook Reference Holbrook2011, 1–53). The main bones of contention have been the claims that the categories make an a priori distinction too rigid for the reality of film (music), and that to call music nondiegetic distances it from the diegesis and misses its part in establishing it. But the critique applies more to applications of the concepts than to their substance. Narratology has never understood them as quasi-ontological categories, but as heuristic constructs in the reader’s or viewer’s mind, in a process of ‘diegetisation’ (see Hartmann Reference Hartmann2007 and Wulff Reference Wulff2007), an evolving understanding of the boundaries of the storyworld that is open to revision. The categories should also not be burdened with tasks they cannot fulfil: they say nothing about what music does in a film, or how realistically it tells its story. And the criticism that ‘nondiegetic’ falsely distances music from the storyworld (Winters Reference Winters2010) misconstrues the relationship of narration and diegesis: the voice of a heterodiegetic narrator in a novel, for example, is by definition not part of the diegesis (and in that sense distanced from it), but it is crucial for creating the diegesis in the reader’s mind, and so integral to it; the same applies to nondiegetic music as one of the ‘voices’ of filmic narration (Heldt Reference Heldt2013, 48–72).

Such disputes stem from a general problem of film-music theory: it gets many of its ideas – usually via film theory – from other disciplines, not least from the much larger and livelier field of literary theory. That does not make ideas inapplicable, but they need to be vetted and adapted. As a narrative medium, film is structurally quite different from, say, a novel (the quintessential form of most literary theory). With few exceptions, a novel consists of a single data stream, and the task for the reader is to imagine; a film consists of sound and vision, which can both be split into any number of data streams, and the task for the viewer is to synthesize. What this means for the applicability of narratological concepts has been considered only fitfully by film theory, and hardly at all by film musicology.

What is true of semiotics is also true of other theoretical perspectives important to film studies, such as genre or gender; in recent film musicology, these have been more often theorized in the process of analysing film-music repertoires. Outlines of a theory of genre and film music have been suggested (see Brownrigg Reference Brownrigg2003; Scheurer Reference Scheurer2008, 7–47; Stokes Reference Stokes2013), and much work has been done on particular film genres. That is even truer of questions of film music and gender, necessarily linked to particular repertoires and their musical codes. The melodrama has been a field of such theorizing (for example, see Flinn Reference Flinn1992; Laing Reference Laing2007; Bullerjahn Reference Bullerjahn2008; Haworth Reference Haworth2012; and Franklin Reference Franklin2011 for a wider genre horizon), but questions of gender affect the musical practices of many other film repertoires as well.

Synthesis or Pluralism?

Trying to pinpoint the state of film-music theory is like taking a snapshot of an explosion. Film musicology has expanded so rapidly over the last generation – and is continuing to do so, and is already being subsumed into the wider field of screen-media musicology – that any summary will be outdated before it has been printed. Plus ça change … Writing in 1971, Christian Metz saw a ‘provisional but necessary pluralism’ in film studies, but hoped for a future time when the ‘diverse methods may be reconciled … and film theory would be a real synthesis’ (Reference Metz1971, 13–14; my translation). Not only has this synthesis yet to happen, it has not even come any closer, and the provisional pluralism seems to be here to stay. Perhaps we should simply enjoy the ride rather than worry too much about mapping its course.

The definition of a film score as musical text is now more complex, or perhaps more loose, than it has ever been. From the multiple handwritten materials of the earliest years of Hollywood scoring to the technologically generated soundscape of current scoring technique, the initial challenge facing a scholar who wishes to analyse a written score is to identify whether one even exists. While some film scores have been published in concert-hall versions (which do not necessarily reflect how the music appeared in the film), scholars seeking original manuscripts must seek out library, archive or personal holdings by composers.

However, handwritten scores – as opposed to those produced using music technology – do not always reflect clearly the individual stages in the process of composing and recording music for film, and it is often likely that the final sound of a recorded score will not mirror accurately what is notated on the page. Post-composition, the complex balancing of the score against other soundtrack elements – such as special effects or dialogue – is often micro-managed by sound editors to the extent that what seems like a striking instrumental line on the page becomes obscured in the finished screen product. To complicate this, handwritten scores, particularly those from the 1930s and 1940s, may not have references to these other soundtrack elements: classical-era Hollywood composers frequently used only dialogue as a signpost for placement and synchronization, as if suggesting that the music had little else to compete with in the soundtrack. Finally, there are the effects of the editorial process on the score: scenes added, cut, extended or reduced all place demands on the composer at the eleventh hour. Versions of a notated score may not include all the last-minute alterations, so there are often pieces of recorded music heard in a film that are apparently undocumented.

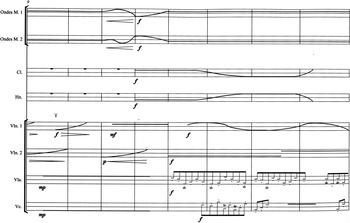

With these caveats in place, however, notated musical texts are a fascinating resource for the study of both individual pieces of film music and the compositional process. Unusual and distinctive musical textures or the exact rhythmic notation of a theme can be revealed, and it is possible to see levels of organization in a manuscript which otherwise escape the ear. The extent of the revelations is sometimes determined by the sources: notated manuscripts come in different forms, from fully orchestrated scores such as those by Bernard Herrmann, to Max Steiner’s four-stave ‘pencil drafts’ (see Platte Reference Platte2010, 21) intended for others to orchestrate. With more recent technological developments, the definition of ‘manuscript’ has expanded to include MIDI files which can be studied collectively to explore structural and developmental processes in a way which is not possible even with a heavily annotated handwritten score. These can lead to a more holistic study of the sound design of a film, expanding the remit of the film musicologist.

In 2000, I established a series of Film Score Guides, designed to enable scholars to bring all the contingent factors in a score’s composition together with its analysis. Though initially published by Greenwood Press, the series transferred to Scarecrow Press in 2003 and has grown from its first volume, on Steiner’s Reference Steiner1942 score for Now, Voyager (Daubney Reference Daubney2000), to cover a contrasting range of traditional and innovative scoring techniques across a wide variety of films from the 1930s to the twenty-first century. In the research for these volumes, the authors drew on diverse academic library, studio and personal archives, and this chapter collates our experiences of this type of research. As series editor, I have had a fascinating oversight into the complexity and revelations of this process, and the authors have generously shared their experiences through personal discussion, as indicated below.

Working in an Archive

For scholars wishing to work on American or British film composers, there are a number of useful archival holdings. In the United States, these include (but are not limited to): the University of California Los Angeles Film and Television Archive; the University of Southern California; the University of California Santa Barbara; the Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills; the US Library of Congress (LOC); the University of Syracuse, New York State; and Brigham Young University, Utah. Holdings in the United Kingdom are wide-ranging, though some focus more exclusively on British composers and/or British film. Thanks to the diligent and detailed investigation by Miguel Mera and Ben Winters into the holdings of film-music materials in the UK on behalf of the Music Libraries Trust, there is now a comprehensive assessment of holdings available (Mera and Winters Reference Mera and Winters2009). These include university libraries such as those at Leeds, Oxford, Trinity College of Music and University College Cork; national libraries and archives such as the British Library, the BBC Music Library and the British Film Institute; and other small specialized collections.

Increasingly, contemporary composers keep their own digital archives of materials, including emails and MIDI drafts, and scholars who have the opportunity to work with such composers have the benefit of a sometimes greater range of detail than might have been sifted out in an older paper-based collection. Indeed, as the Scarecrow authors have found, the range of factors affecting the composition of a film score is both fascinating and, at times, overwhelming. The richness and diversity of materials available in an academic or personal archive enables study of a score’s composition in the context of scrapbooks, notebooks, letters, emails, interviews, memoranda and studio internal documentation such as production schedules and cue sheets. Furthermore, research is often not limited to one archive: in the case of David Cooper’s contextual research of Herrmann (Reference Cooper2001 and Reference Cooper2005), he used The Bernard Herrmann Papers at the University of California Santa Barbara; the Library of Congress for its microfilm copies of many of the holographic scores and some original manuscripts; and the CBS collections at the New York Public Library and the Music Library Special Collections at UCLA for Herrmann’s music for radio and for television, respectively.

It is easiest and most productive to visit an archive in person, if at all possible, and several days should be allowed for looking over the materials. Scholars must keep extensive and accurate records of archival research – particularly if they are able to visit only once – as it is not always possible to photocopy materials without securing a licence in advance. Most archives produce catalogues of their holdings which allow for preparation in advance and a more focused and productive visit. Building a relationship before arrival with an archive director or manager is also essential, as you are more likely to be able to access what you need if they understand what your aims are for the visit. You will also find out what limitations there are on copying or even viewing materials, due to fragility, preservation, external loan and so on.

Obtaining photocopies of original scores or from microfilm for study away from an archive can be extremely difficult, if not impossible, and often requires permission of the copyright holder as well as the archivist. A scholar intending to publish research, including transcriptions or reproductions of score material, will need to obtain copyright permission to do so, and in some cases also a licence to reproduce the score for research purposes. The archivist may be able to access the network of companies and individuals with the authority to grant copyright permissions, which can itself be a long and convoluted process: this issue is discussed in more detail later in the chapter.

During my PhD research on Steiner, content from which was later published in my Film Score Guide on Now, Voyager, I spent a week studying the Max Steiner Collection at Brigham Young University. The Steiner Collection is an excellent and diverse accumulation of materials, from personal letters to his four wives and his son, to the 177 volumes of bound manuscript film scores. The Academy Award statuettes for Now, Voyager and Since You Went Away (1944) sit in a vault, while three enormous scrapbooks covering the years 1930–53 chronicle the period of Steiner’s greatest industry through his own choice of newspaper reviews, underlined by the composer in thick blue or orange pencil. There is also, among other materials, correspondence with Jack Warner and David O. Selznick, and a collection of copies of contracts, royalty statements and original songs and other compositions from Steiner’s pre-Hollywood career in Vienna and on Broadway.

With such a range of material, it can be difficult to know where to start, and certainly it can be helpful to begin with a particular score and work outwards through the contextual material. A holograph may provide some sense of the composer’s personality through style of notation, approach to editing and, perhaps most conspicuously, through marginalia and other written commentary. For example, Steiner’s pencil drafts contain many ribald annotations to his orchestrators. His comments paint a vivid picture of his often scornful opinion of the films’ subject matter or leading actors, giving a clearer insight into his attitude and approach to process than many other more formal documents he wrote. For example, in the score for Dodge City (1939) he annotates a dialogue cue, ‘How d’you like these here onions?’ with the remark, ‘God help us!—The whole picture is like this—I am resigning!!’ (Steiner Reference Steiner1939b, 33). Bette Davis once observed that Steiner was ‘one of the great contributors to countless films with his musical scores. Many a so-so film was made better through his talents’ (Stine Reference Stine and Davis1974, 11), but she was doubtless unaware of how the composer judged her: in the pencil draft for The Bride Came C.O.D. (Reference Steiner1941) he complained that ‘She cries like a stuck pig’ (Reference Steiner1941, 28).

Steiner also demonstrates his frustrations over having to write so much music in such a short time. Against one long sustained chord in the score to The Oklahoma Kid (1939), he notes: ‘Always good when you don’t know what to write’ (Reference Steiner1939a, 163), and – lacking the time to write everything down in the pencil draft to Dodge City – he asks for an orchestration of ‘Everything bar the kitchen stove!’ (Reference Steiner1939b, 145). His notes sometimes indicate a desire to shift responsibility for decision-making to his orchestrator, as in the pencil draft to The Gay Sisters (Reference Steiner1942) where he admits to Hugo Friedhofer: ‘I don’t know how to orchestrate this—all I know is I hear a SORT of “sentimental” Children’s TUNE’ (Reference Steiner1942, 79).

The other advantage of archival research is the discovery of circumstantial materials that build a picture of the context in which the music was composed, shedding light on a particular strategy or situation which influenced a score’s construction. A studio’s internal documentation such as production schedules or chains of correspondence have significance for the deduction of process that is useful in a creative context where the means of production are often invisible. But personal documentation can also reveal this, such as letters from Steiner to his third wife, Louise Klos, written on his behalf by his secretary. For example:

He is working very hard, as you can imagine. [Since You Went Away] is another picture like “Gone with the Wind” [1939]; twenty one reels; changes every day; having to get approvals from Mr. Selznick for every melody he writes, etc., so you can appreciate from his former experience [Gone with the Wind] what he is going through.

This body of contextual detail often has to stand in the place of more formal documentation of the composer’s art. Steiner completed an (as yet) unpublished autobiography in 1964 entitled ‘Notes to You’, but its value to the scholar is fairly limited, as it is full of unsubstantiated and inaccurate anecdotes about his life, and contains comparatively little discussion of scoring practice. He also did not experience the cult of celebrity which generated the television-interview opportunities and greater media coverage enjoyed by later composers.

By contrast, students of Herrmann’s scores can find published interviews (as in R. S. Brown Reference Brown1994, 289–93) and footage of Herrmann talking about his work, but his scores tend to be fully orchestrated (rather than the short forms of the Steiner archive) and contain very little in the way of marginalia. As Cooper observes, it can be difficult to deduce process from such a clean manuscript:

I would be interested to know from Herrmann how many of the musical decisions were ‘intuitive’ and how many were rationalised, though I guess he would generally go for the latter. I would also be interested to know how he dealt with issues of timing, both in composition and performance. For example, he did record The Ghost and Mrs. Muir [1947], but not Vertigo [1958], and was renowned for his ability to work without aids.

Sometimes, archival work does not make matters clearer. When Ben Winters (Reference Winters2007) explored the relationship between Erich Wolfgang Korngold and his orchestrator Friedfhofer during the composition of the score for The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), he found that

the manuscript materials threw up more questions than answers … Evidently there was a degree of trust between them (as Friedhofer’s oral history recounts), and that perhaps explains in part why there were virtually no written instructions about orchestration recorded on Korngold’s short score … [And] while pages of Robin Hood short score that existed only in the hand of Friedhofer suggested that boundaries between composition and orchestration may in a few cases have been less clearly defined than we might have supposed, that evidence never extended to ‘proof’ of authorship. In short, examining the manuscript materials opened up areas for speculation rather than serving to define the nature of the relationship.

Working with a Living Composer

It might seem that working on the scores of a living composer would be easier, but there are different obstacles and restrictions to gaining access to material. Sometimes individuals are unwilling to be frank about particular situations, or about colleagues and other participants in the film business, not least because they may have to work with them again in the future. Nevertheless, with access to a composer and the opportunity to discuss his or her work, the exploration of compositional process can be fascinating. Obtaining scores can still be a lengthy process because those of living composers tend not to be archived, and are often kept anywhere from studio libraries or storage facilities to the composer’s personal collection. The most effective approach is to contact the composer directly, via their agent or their personal music-production company. Approaching studios is not always useful, as staff are often unaware of what materials are held in storage, and catalogues are virtually non-existent. Cultivating and acknowledging contacts and developing networks are vital parts of the film-music research process.

Mera (Reference Mera2007) had the benefit of considerable access to the personal holdings of Mychael Danna while preparing his book on Danna’s score for The Ice Storm (1997). Danna provided access to all his personal materials, including MIDI and audio files, as well as making himself available to discuss his process of composition and the finished work. Working with MIDI and audio files might seem to provide a clinical, less intimate picture of the creative process, but in practice the technology makes it possible to view process on a more precise level. MIDI sequencer files show the set-up of a composer’s workstation, giving an added perspective on what equipment is used and how it contributes to the process. They also often contain an audio track with dialogue and sound effects, which, while helpful to the orchestrator and conductor, also gives an immediate picture to the analyst of how the composer accommodates the potentially competing elements in the soundtrack. This microscopic level of detail can bring a different focus to analysis, as Mera explains:

One of the most important features of this sort of material is that it is extremely useful in showing how a composition progresses and develops. In some instances there are sixteen versions of the same cue, so it is possible to chart the composer’s thought processes from initial idea to finished product. When you also know something about how the composer was influenced by the director, the producer, or even the temporary score during this process, the sequencer files become a very powerful analytical tool, which allows the musicologist to pursue analyses of intention as well as interpretation. MIDI files can be seen to be a very detailed equivalent to the traditional composer’s sketch.

Danna’s generous co-operation with Mera emphasizes the personal aspect of working with a living composer. Trust is an important element in the relationship, and the emphasis moves towards sharing and discussion, from the more objective analysis that we engage in when composers are not personally known to us. Mera agrees that the input of the composer is ‘incredibly helpful’, but points out that a certain balance is required when a composer does co-operate with the research process:

The potential problem is that the composer will say something about their work that ruins your nice, neat academic argument. However, I find this debate to be one of the most interesting features of understanding a living film composer’s work. Scholars have, in my opinion, been nervous to talk to film composers about their work or to draw information from interviews and so on. It depends on who the composer is, of course, but I don’t understand why there is not at least the desire to try and understand a composer’s intentions before applying an interpretation to what they have done.

Even with the composer’s participation, the musicological process is not always easy. Charles Leinberger (Reference Leinberger2004) had the opportunity to interview Ennio Morricone for his book on the score for The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966), an interview which was conducted on the composer’s terms, in Italian and in his home city of Rome. The opportunity to hear the composer playing from his own score at the piano was clearly a unique experience, as it would be for any scholar, although in other respects Morricone was less keen to participate in the analytical process. He was particularly reluctant to explain certain distinctive aspects of his technique for fear of being copied by other composers, and Leinberger was faced with a decision about how he should respect Morricone’s wishes and protect what the composer saw as his trade secrets.

Janet Halfyard (Reference Halfyard2004) had a completely contrasting experience when preparing her book on Danny Elfman’s score for Batman (1989). Elfman has consistently declined to engage with academic study of his work, though he has, in contrast with his classical-era predecessors, given a huge number of press interviews which provide an account of his scoring methods. Despite approaches to participate, Elfman was unwilling to contribute anything to Halfyard’s research, but she does see a specific advantage in this:

It left me free to explore my own readings of the music without having to bow to the obvious authority of the composer’s own version of events. I would love to have discussed the film with him, but the fact that he wasn’t interested did give me a lot of freedom that I would potentially have lost if his readings had been very different from my own. As it is, they are my readings, everything that I have got from the score in the absence of the author’s own interpretation. And I’m actually rather impressed that the score doesn’t need him explaining it for all those multiple layers of meaning to come out.

Elfman’s score for Batman sits beside Prince’s soundtrack album for the same film, and for Halfyard this was another area which would have benefited from the composer’s participation:

I would like to have asked Elfman how much of Prince’s soundtrack album had already been written when he started work on the score, because of the relationship between Prince’s ‘Scandalous’ motif and the ‘Bat-theme’; and how intuitive his scheme of time signatures for rationality and irrationality was.

Tracking down all the contributors to the musical component of the film can be complicated and time-consuming, and with older films it can also be a question of exploring other pre-composed music contemporaneous to the film’s production or relevant to the period of its narrative, such as the extensive use of vernacular songs and march tunes in Gone With the Wind or the wartime popular hits of Since You Went Away. It also puts emphasis on exploring the role of other studio staff in the process. Was a temporary track used, or was there input from a music editor or even the director on scoring matters? It can be crucial to the process of analysing originally composed music to find out what form these other interventions and contributions took, so it is useful to explore whether studio papers are available.

An additional factor in Halfyard’s research was that the score she used was a full orchestral score written in the hand of Elfman’s orchestrator and assistant, Steve Bartek. Elfman typically composes about half the material on a sequencer, filling out the other half by hand onto the sequencer print-offs. Bartek then orchestrates in full this sixteen-stave short score. A photocopy of Bartek’s score was made available by the Warner Bros. Music Library, but small sections of his notation were illegible. The challenge to certainty created by this small detail is indicative of a larger, interesting question about the ability of the scholar to examine the authorial relationship between a composer and his orchestrator when the orchestrator’s score is the only one available.

Heather Laing (Reference Laing2004) revealed a similarly close relationship between Gabriel Yared and his orchestrator John Bell during research for her book on The English Patient (1996). In an interview with Laing, Yared gave an explanation of how he and Bell had collaborated on a later film score that brought a level of specificity valuable to the analyst:

With the help of his sound engineer Georges Rodi, [Yared] creates an exact synthesizer version of each cue, which is then translated by Bell into actual instrumentation. ‘But,’ says Yared, there is ‘not one note to add, not one harmony to change, not one counterpoint to add – it’s all there and it’s divided into many tracks … [E]verything is set and I don’t want anything to be added, and anything to be subtracted, from that.’ The synthesizer demo for The Talented Mr. Ripley [1999] is therefore, according to Yared, indistinguishable from the final instrumental tracks that appear in the film.

A recurrent issue pondered by scholars is the role and nature of intuition in the compositional process, and this frequently emerges in discussion with composers. Several of the scholars mentioned above have discussed the process of compositional decision-making and its effect on analytical interpretation, and having a trusting relationship with the composer may make it possible to explore these issues. From an analytical perspective, we are often keen to pin down definitive explanations for why a particular instrument or chord or melodic motif is used, and answers from composers can appear to lend weight to the conclusions. But there is always an element of tension in the publication of research in which a composer has been involved. Laing observes, ‘I was really lucky with [Yared] – I’m not at all sure how I’d be feeling had I been working with someone who wasn’t as interested or supportive as he was. Nonetheless, my heart was in my mouth from the moment I sent him the draft manuscript to the moment I received his comments!’ (personal communication, 23 November 2004).

Copyright and Other Considerations

In general, if a composer has been dead for more than seventy years then there is greater freedom to quote extracts from scores because they are in the public domain, but because film music is still a relatively young art, most of the materials that scholars want to use are still covered by copyright. Finding the copyright holder and obtaining permission from them remain the biggest obstacles to the citation of film scores in published material. For example, Cooper was advised that he was the first person to have been loaned a personal copy of one particular Herrmann manuscript by Paramount, and found it difficult to track down the right person in the studio from whom to secure permission, before finally resorting to help from a film-music ‘insider’ (personal communication, 1 March 2004). Generally, studios are still unprepared for requests to study film scores or for copyright permission for score reproductions: it took over a year for me to secure permission for extracts from Steiner’s scores for Now, Voyager and other films, via a very circuitous route through Warner Bros. in California to IMI in the United Kingdom, who actually held the copyright.

Securing copyright permission relies primarily on making contact with the right person in the right organization. Ownership of copyright is not always clear, particularly with music from a film where the publication rights from sheet music, for example, may differ from the rights for the soundtrack recording and the video release. The composer’s own company may also be involved. It is vital to begin by finding out exactly which company or individual owns the rights to reproduction of the orchestral score, and it is recommended that this should be done right at the beginning of research, because it can be extremely time consuming and frustrating to locate the copyright owner, and then to get permission. Archivists can often be helpful in this respect with a composer who has already died. Sometimes companies themselves are not certain which copyright they own, and one must be prepared to make follow-up calls to individuals until permission is granted.