Introduction

Yiddish has served the English language as a comparatively minor donor language of words and meanings over the course of time. However, Yiddish has provided English with a number of borrowingsFootnote 1 that have become fairly common in present-day usage. This paper provides a rounded overview of the different lexical domains to which Yiddish contributed in the form of new words and expressions over the centuries, which has been relatively neglected in existing studies.Footnote 2 The focus of linguistic concern is on those Yiddish-derived terms that have become established in current English.

The findings presented in this paper are based on the analysis of a comprehensive lexicographical sample of 290 Yiddish borrowings retrieved from Murray et al.'s (Reference Murray, Bradley, Craigie and Onions1884–) Oxford English Dictionary Online (hereafter, OED) and the electronic form of Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged (Gove, Reference Gove2007; hereafter Webster's Unabridged). At present, the OED is undergoing its first complete revision. The OED can be consulted online at <http://www.oed.com>, consisting of the Second Edition from 1989 (commonly referred to as OED2), the 1993 and 1997 OED Additions Series (hereafter, OED ADD Series) and a plethora of revised and new lexical entries which are part of the Third Edition of the OED3. The OED Online is updated every three months with additional linguistic data.Footnote 3 The digitalized version of Webster's Unabridged corresponds to the Third Edition of the dictionary, to which several new words and meanings are being added at regular intervals. It currently represents the largest comprehensive dictionary of American English. Both the electronic OED and Webster's Unabridged include a search option which allows the identification of Yiddish-derived items in English: Advanced Search: entries containing ‘Yiddish’ in ‘Etymology’.

As I show in thie current paper, the collection of Yiddish borrowings identified in this way encompasses a number of lexical items which are mainly documented in American usage. An essential proportion of Yiddish borrowings were taken over into American English as a result of the Yiddish-speaking population in the United States. Durkin (Reference Durkin2014: 364) points out that:

Yiddish loanwords may often be perceived as Americanisms by speakers of other English varieties, because of the considerable international social and cultural impact of Jewish communities in the United States (especially in New York), although there may be long histories of use within Jewish communities elsewhere (e.g. in London). This perception is probably true to the extent that it is primarily the use of these words in some varieties of US English that has led to their familiarity to non-Jewish English speakers elsewhere.

The sample of Yiddish borrowings collected from the OED and Webster's Unabridged also consists of a number of lexical items which ultimately go back to other foreign languages, such as German, Hebrew, or Polish. It should be noted that the different words and meanings were categorized with the assumption that Yiddish is the immediate donor language. An example is the borrowing klezmer, which refers to ‘a Jewish instrumentalist’, or, in a more specific use, to ‘a member of a band of folk musicians in eastern Europe hired to play at Jewish weddings and gatherings’ (Webster's Unabridged). By the means of metonymy, it can also be used to designate the type of music which is performed by such a band. The word was classified as an adoption of the Yiddish klezmer, despite the fact that its Yiddish source originated in Hebrew (see OED3).

It seems noteworthy that the dictionaries consulted record the romanized forms of the words of Yiddish origin. The different letters of the Yiddish-derived items have been transcribed into the English alphabet, as is the case with klezmer, originally spelt כליזמר or קלעזמער according to the Semitic alphabet. Quite a few Yiddish borrowings have several different spelling variants in English. In these cases, I provide the orthographical form which is identified as the most common spelling in the OED and in Webster's Unabridged.

Subject areas and spheres of life influenced by Yiddish

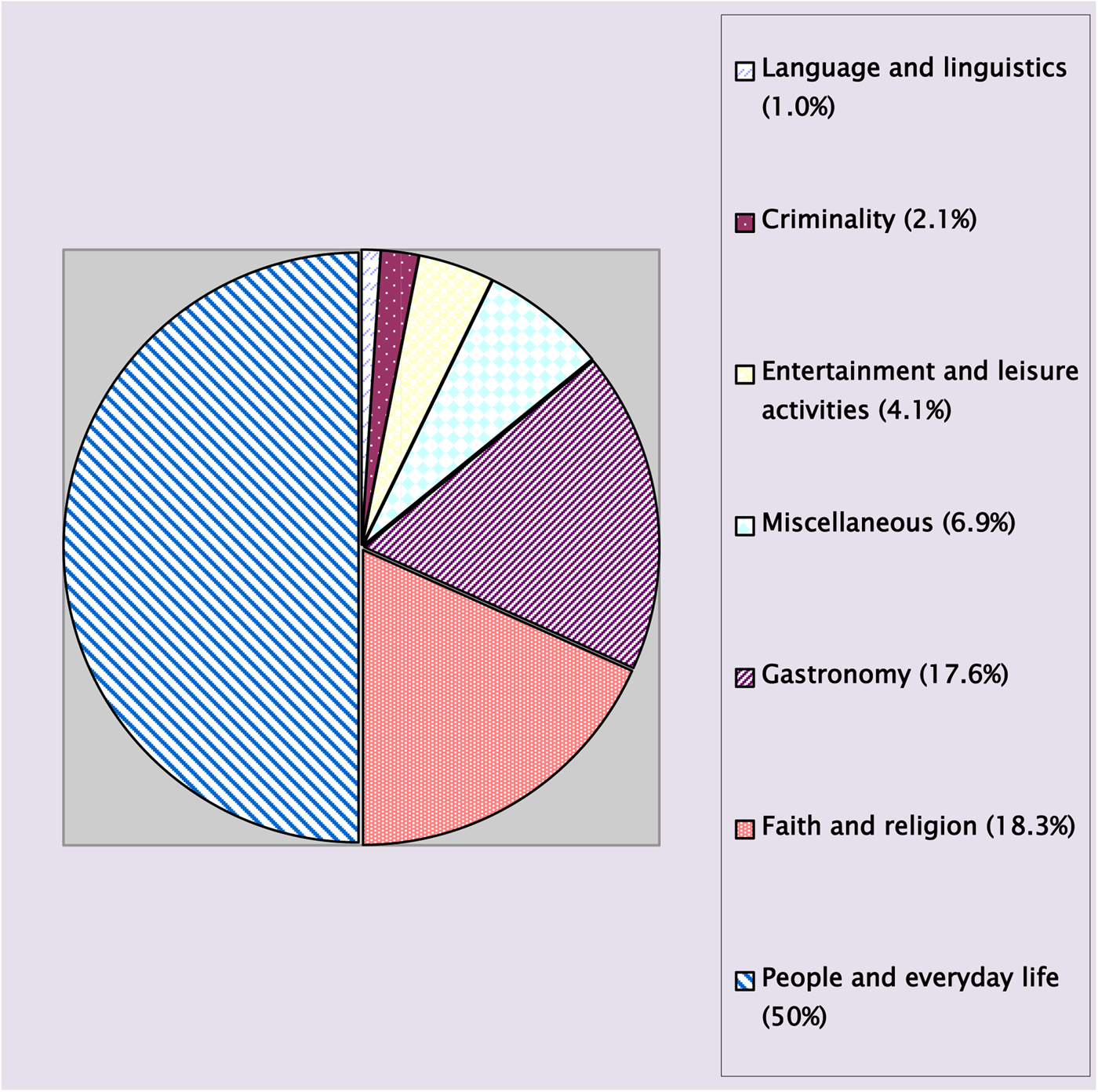

The number of Yiddish-derived words and phrasesFootnote 4 included in the OED Online and in Webster's Unabridged amounts to 290 lexical items. I grouped the different borrowings into six general domains and their related subfields. The division of several technical terms was a consequence of their categorization in the two dictionaries. However, the major assignment of the Yiddish borrowings is my own. The diagram below shows the proportions of the various borrowings in the six major subject areas.

The following list allows a comparison to be conducted between the numbers and proportions of the borrowings in a variety of subject fields with their related subgroups. Areas with a fairly high percentage of Yiddish-derived words and senses succeed domains where the influx of Yiddish was weaker. For each lexical domain, some representative examples of words of Yiddish provenance are provided:

(1) Language and linguistics (three borrowings, i.e. 1.0%), for example, Yiddish, n. (1871); mameloshen, n. (1968).

(2) Criminality (six borrowings, i.e. 2.1%), for example, ganef, n. (circa 1839).

(2.1) Drugs (three borrowings, i.e. 1.0%), for example, schmeck, n. (1932).

(3) Entertainment and leisure activities (12 borrowings, i.e. 4.1%)

(3.1) Music (one borrowing, i.e. 0.3%), for example, klezmer, n. (1908/first recorded in the OED in 1929).

(3.2) Hotel business (three borrowings, i.e. 1.0%), for example, tummler, n. (1965/first attested in 1966 in the OED).

(3.3) Sports and games (eight borrowings, i.e. 2.6%), for example, stuss, n. (1912); bagel, n. (first documented as a sports term in 1974).

(4) Gastronomy (51 borrowings, i.e. 17.6%), for example, matzo, n. (1650); gefüllte fish, n. phr. (1892); bagel, n. (1908/first recorded in the OED in 1919); matzo brei/matzo brie, n. phr. (1949); ingberlach, n. (not dated); kichel, n. (not dated).

(5) Faith and religion (53 borrowings, i.e. 18.3%), frum, adj. (1859); yarmulke, n. (1903); shalach monos, n. phr. (not dated).

(6) People and everyday life (145 borrowings, i.e. 50%)

(6.1) Clothing (five borrowings, i.e. 1.7%), for example, kapote (not dated).

(6.1.1) Accessories (eight borrowings, i.e. 2.6%), for example, moloker, n. (1890).

(6.2) Means of payment (seven borrowings, i.e. 2.4%), for example, finnip, n. (1839).

(6.3) Trade and selling (eight borrowings, i.e. 2.6%), for example, to hondle, v. (1921); schlockmeister, n. (1965).

(6.4) Love and sexuality (11 borrowings, i.e. 3.8%), e.g to yentz, v. (1930); zaftig, adj. (1937); bashert, n. (1975).

(6.5) Communication (25borrowings, i.e. 8.6%), for example, (that's) all one needs, phr. (1965); meh, interjection (1992).

(6.6) Society, human behaviour and characteristics (81 borrowings, i.e. 27.9%), for example, meshuga, adj. (1868); luftmensch/luftmensh, n. (1907); schlump, n. (1948).

20 (i.e. 6.9%) Yiddish borrowings recorded in the OED and in Webster's Unabridged, cannot be clearly categorized into a particular lexical domain. This is valid for tsores, for instance, which was adopted from Yiddish in 1901. It denotes ‘[t]rouble(s), worries’ (OED2), just like the Yiddish source term tsores, the plural of tsore ‘woe’, ‘trouble’, itself derived from Hebrew. According to the OED2, the borrowing is confined to colloquial American English.

The field of language and linguistics encompass the smallest number of Yiddish borrowings. The words Yiddish and mameloshen are typical examples. From Webster's Unabridged it emerges that the former was adapted from the Yiddish yidish in the phrase yidish daytsh, ‘Jewish German’, which ultimately goes back to Middle High German. The borrowing has been documented since 1871 in English. Mameloshen is restricted to Jewish usage, designating ‘a mother tongue’ (OED3), notably Yiddish.Footnote 5 Its earliest recorded usage in the OED3 dates from 1968.

The domain of criminality equally includes a relatively small percentage of adopted lexical items. Most of them are slang terms occurring in American English. This is true for the borrowing ganef, for instance, which was borrowed from Yiddish in circa 1839 as a term for ‘a thief, a rascal’ (Webster's Unabridged). Similarly, the related field of drugs contains various slang terms, such as schmeck, which refers to ‘a drug’ or, in a more specialized sense, to ‘heroin’ (OED2). The item was taken over from the Yiddish schmeck, literally ‘a sniff’, in the earlier decades of the 20th century, i.e. in 1932.

Several Yiddish borrowings which have been assumed into English belong to the area of entertainment and leisure activities. These encompass Yiddish-derived items in ‘music’ (for example, klezmer), ‘hotel business’ (for example, tummler), and ‘sports and games’ (for example, bagel, stuss). According to the OED2, tummler was originally and is mostly used in American English for ‘[s]omeone who acts the clown, a prankster’, or, in a more specific meaning, ‘a professional maker of amusement and jollity at a hotel or the like’, as in:

1977 New Yorker 12 Sept. 86/3 A summer job as part-time social director and tummler at a hotel in Lake Hopatcong, New Jersey. (OED2)

Tummler has been attested since the 1960s in English. Its Yiddish equivalent was formed from the German verb tummeln ‘to stir’ (see OED2). As for bagel, the word was first documented as a sports term some time after its introduction into English. The word was adapted from the Yiddish beygel at the beginning of the 20th century, referring to ‘[a] hard ring-shaped salty roll of bread’ (OED2). Bagel has been attested as a slang term since 1974 for ‘[a] score in a set of six games to love’ (OED2). The borrowing was first used in this sense by Eddie Dibbs, an American tennis player, ‘due to the similarity of the numeral 0 in the scoreline 6-0 to the shape of a bagel’ (OED2), as is corroborated by the following usage example:

1974 Los Angeles Times 20 Sept. iii. 1/1 You see, when you get beat six games to love, it's called ‘The Bagel’ … A bagel has a hole. Zero. (OED2)

Stuss relates to ‘faro in which cards are dealt by hand and the banker takes all bets on splits’ (Webster's Unabridged). It has been documented in English since 1912. The Yiddish associate shtos/stos may correspond to the German Stoß, meaning ‘push’, ‘blow’ (see OED2, Webster's Unabridged).

The field of gastronomy represents the third largest area influenced by Yiddish. Most of the borrowings in this domain refer to dishes. Examples are gefüllte fish, ‘[a] Jewish dish of stewed or baked stuffed fish or fish-cakes, boiled in a fish-or vegetable-broth’ (OED2), matzo brei and its spelling variant matzo brie, designating porridge prepared from matzo, itself a term of Yiddish origin for ‘[a] crisp biscuit or wafer of unleavened bread which is traditionally eaten by Jews during Passover’ (OED3). We also find a number of culinary terms for desserts and items of confectionary among the borrowings under consideration, such as ingberlach, ‘a candy made chiefly of ginger and honey’, and kichel, ‘a semisweet baked product made of eggs, flour, and sugar usually rolled and cut in diamond shape and baked until puffed’ (Webster's Unabridged). Ingberlach constitutes the plural of the Yiddish ingberl ‘small piece of ginger sweet’, a diminutive coined from ingber ‘ginger’. Kichel is derived from the Yiddish kikhel ‘small cake’, the diminutive of kukhen ‘cake’, which ultimately goes back to Old High German. It should be noted that ingberlach and kichel are listed in Webster's Unabridged, but they are not recorded in the OED, which might be due to the fact that their usage is more common in American English. The items are not given a first attested use in Webster's Unabridged.

Faith and religion constitutes the second largest domain influenced by Yiddish over time. A typical feature of this field is the comparatively high proportion of culture-specific terms from Judaism. An example is the adjectival borrowing frum, ‘[d]evoutly observant of Jewish laws; strictly orthodox or religious’ (OED3). The word has been attested in English since 1859. A look at the documentary linguistic evidence in dictionaries such as the OED3 reveals that it is still in use in current English, for example:

2001 P. Marber Howard Katz ii. 98 Lou. (referring to yarmulke) I didn't know you were frum. Katz. Oh yeah, well, I've become frum. (OED3)

The above example contains an additional Yiddish borrowing to do with faith and religion. This is yarmulke, which was introduced into English in 1903 as a term for ‘a skull cap worn especially by Orthodox and Conservative Jewish males in the synagogue, the house, and study halls’ (Webster's Unabridged). Its Yiddish source yarmolke goes back to the Polish jarmulka, meaning ‘cap’. There is also the nominal phrase shalach monos, which can either refer to ‘the exchange of gifts or the sending of gifts to the poor at the time of the Purim festival’, or, in a metonymic sense, to ‘a Purim gift consisting typically of cakes, confections, fruit, wine, or money’ (Webster's Unabridged). Like most of the lexical items in the field of faith and religion, shalach monos belongs to the group of Yiddish borrowings which appear to be unknown to the ‘average’ native speaker of English.

The field of people and everyday life includes the largest proportion of Yiddish borrowings. The domain comprises six subfields, consisting of borrowings to do with clothing and accessories, such as kapote, a type of coat traditionally worn by Jews coming from eastern European countries, and moloker, a variety of hat. It also encompasses Yiddish-derived words referring to means of payment, trade and selling. Examples are finnip, which specifies five pounds or, in American English, a five-dollar note, the verbal borrowing to hondle, meaning ‘to haggle, to bargain’ (OED3) in Jewish usage, and schlockmeister, ‘a purveyor of cheap merchandise, ‘special offers’, and the like’ (OED2). The latter constitutes a compound formed from the Yiddish noun schlock, a colloquial term for ‘[c]heap, shoddy, or defective goods’ (OED2), and meister, which either reflects the Yiddish mayster or the German Meister ‘master’. It seems noteworthy that the more assimilated form schlockmaster, a hybrid compound, is equally recorded in the OED2, as in:

1978 M. Puzo Fools Die xxxiii. 388 He had signed a long-term contract with Tri-Culture and become the ace schlockmaster for Jeff Wagon.

In addition, there are borrowings related to love and sexuality, such as bashert, a term occurring in Jewish usage for ‘a person's predestined romantic partner; a soulmate’ (OED3), the verb to yentz, literally meaning ‘to cheat’, ‘to deceive’ or, in a transferred sense, ‘to fornicate’, and the adjective zaftig, which is used in relation to a woman in the sense of ‘plump, curvaceous, “sexy”’ (OED2). Zaftig falls into the category of Yiddish-derived words which are restricted to colloquial American English, for example:

1981 Gossip (Holiday Special) 11/2 Zaftig Dolly Parton … once described herself as looking like a ‘hooker with a heart of gold’. (OED2)

People and everyday life also encompasses borrowings referring to communication, among them a number of interjections and phrases which may make a speech or a conversation more expressive. The interjection meh and the phrase (that's) all one needs serve as examples. Meh is used to express ‘indifference or lack of enthusiasm’ (OED3), as is illustrated by the following example:

2012 N.Y. Times (National ed.) 1 Nov. b13/1 Who else could they root for? The Chicago Bulls? Impossible. The Boston Celtics? Unconscionable. The team in New Jersey? Meh. (OED3)

According to the OED3, meh might go back to the Yiddish me, literally ‘be as it may’, ‘so-so’. The phrase (that's) all one needs was translated from the Yiddish nor dos feylt mir. The linguistic documentary evidence illustrating the typical use of this phrase in English often reflects an ironic or sarcastic tone of the speaker, as in:

1977 ‘E. Crispin’ Glimpses of Moon xi. 217 ‘My God, it's the pigs,’ said the hunt saboteuse disgustedly. ‘That was all we needed.’ (OED3)

In addition, the domain consists of a substantial proportion of borrowings relating to society, human behaviour and characteristics, including a number of terms for individuals with negative connotations. An example is luftmensch/luftmensh, ‘an impractical contemplative person having no definite trade, business, or income’ (Webster's Unabridged). Its Yiddish source was coined from the German Luft ‘air’ and Mensch ‘individual’, ‘human being’. A characteristic of this field is the comparatively high proportion of borrowings which chiefly occur in colloquial usage, such as schlump, ‘[a] dull-witted, slow, or slovenly person; a slob; a fool’ (1993 OED ADD Series), and meshuga, a slang term commonly used by Jewish speakers in the meaning of ‘mad, crazy; stupid’ (OED3).

Conclusion

This paper shows that a characteristic of the body of lexical borrowings which has been transferred from Yiddish into English over the course of time is its variety. It comprises not only specialized, technical expressions confined to Judaism, but also words which have become fairly common in present-day usage. A typical feature of the Yiddish-derived vocabulary is the considerable number of colloquial terms, which mostly occur in informal usage. The majority of these types of borrowings have meanings and connotations for which no adequate English-translation equivalent exists. One might argue that Yiddish has provided the language with a host of words that seem to be indispensable to ‘modern’ speakers of English.

Figure 1. The proportion of Yiddish borrowings in the different subject areas

JULIA SCHULTZ works as a lecturer in linguistics at the English Department at Heidelberg University. She has authored a number of studies which concentrate on different language contact situations and their linguistic outcomes, such as the impact of Spanish on English since 1801, 19th-century French cuisine terms and their semantic integration into English, and the influence of German on English since 1901. Her research interests focus on language contact and the use of online sources in lexicological research. Email: Evajulia.Schultz@web.de

JULIA SCHULTZ works as a lecturer in linguistics at the English Department at Heidelberg University. She has authored a number of studies which concentrate on different language contact situations and their linguistic outcomes, such as the impact of Spanish on English since 1801, 19th-century French cuisine terms and their semantic integration into English, and the influence of German on English since 1901. Her research interests focus on language contact and the use of online sources in lexicological research. Email: Evajulia.Schultz@web.de