Introduction

Modern insurance was first introduced into China during the early nineteenth century. Initially sold by foreigners to foreigners, it was steadily embraced by Chinese businesses in the decades after the First Opium War (1839–1842) forcibly opened China to commerce with Western countries. In China, as in many countries, the industry was dominated by British and American multinational firms who possessed larger pools of capital and more extensive experience in structuring, pricing, and marketing.Footnote 1 This first-mover advantage held until the early twentieth century, when Chinese-owned insurers proliferated and mounted a serious challenge to their foreign competitors, especially in the market for fire insurance. While likening foreign firms operating in China to “presumptuous guests usurping the role of the host,” one Chinese writer looking back at the industry’s history nonetheless declared that Chinese fire insurers were “now standing in the position as masters” of the market.Footnote 2

Perhaps no other firm better exemplified the proliferation of insurance in China and the success of Chinese-owned enterprises than the Tai Ping Insurance Company. Tai Ping—“peace and tranquility” in Chinese—was founded in November 1929 by Zhou Zuomin (Chou Tso-min), president and founder of China’s largest private bank Jincheng (Kincheng). At first glance, Zhou’s entry into a new business seemed inopportune. Long-simmering geopolitical tensions with Japan eventually led to the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). Meanwhile, domestic instability and incessant infighting during the first years of the Republic of China (1912–1949) were only partially ameliorated by the establishment of a new government by the Nationalist Party (1927–1949) under General Chiang Kai-shek. Yet by the mid-1930s, Tai Ping had catapulted itself past more established rivals to become one of the largest Chinese insurance companies. Its spectacular rise impressed observers then and now. From the 1930s to today, Chinese writers and businessmen hailed the company as a pride of the Chinese nation and an exemplar of native entrepreneurship.Footnote 3

How did a company like Tai Ping manage to realize such a remarkable feat? Surveying the history of insurance in China, David Faure and Elisabeth Köll correctly note how the financial product was first “transplanted” from the West and later “indigenized” from the late nineteenth through mid-twentieth centuries as China moved within the ambit of global capitalism.Footnote 4 Tai Ping was certainly both a participant and beneficiary of this indigenization, a fledgling Chinese firm that mastered selling a formerly foreign financial product and managed to win business in a competitive environment. Yet the histories of Tai Ping and the Chinese fire insurance industry also address a research lacuna in the history of insurance more generally. With some exceptions, scholarship on the “internationalization” of insurance beyond the developed markets of Western Europe and North America have typically focused more on the experiences of British and American multinational enterprises and less on that of native companies.Footnote 5 Such an oversight not only misses the storied histories of companies like Tai Ping but also how native firms and consumers themselves adapted to the global spread of insurance.Footnote 6

Chinese scholarship on insurance, for its part, has primarily used the industry’s history as another example of untrammeled foreign imperialism in China before 1949.Footnote 7 The “unequal treaties” (bu pingdeng tiaoyue) China signed in the wake of successive military defeats accorded significant privileges to foreign governments and companies in China, creating “semi-colonial” conditions that protected the first-mover advantages of foreign insurers. While such accounts are not inaccurate, they are nonetheless more concerned with reinforcing nationalistic narratives by portraying the Sino-foreign rivalry as a strictly zero-sum competition that ended only when the People’s Republic was established and foreign firms expelled. Chinese companies like Tai Ping have been celebrated as Chinese success stories, but their actual workings, their larger significance in an intensely competitive industry, and their interactions with foreign firms and ideas remain unexplored.Footnote 8

More broadly, the case of Tai Ping highlights the degree of institutional convergence and divergence between the Chinese insurance industry and its global counterparts. Like insurers elsewhere, Chinese insurers faced challenges in selling insurance, managing risks, and dealing with regulations. Also like insurers elsewhere, Chinese insurers grappled with how to properly assess risks and end ruinous price wars as they tried to forge cartels and control brokers. But despite such parallels, their efforts were still shaped by indigenous traditions and historical experiences. Attention to this history contributes to a more inclusive history of insurance that considers both commonalities and particularities in its global diffusion, thereby offering an overlooked angle to better understand the internationalization of insurance.

This paper traces the development of Tai Ping and the Chinese fire insurance industry from 1928 to 1937, the decade bookended by the founding of the company and the outbreak of war with Japan. Using business archives, press reports, and industry publications, it recounts the drivers behind the proliferation of fire insurance in China and the growth of Tai Ping specifically. This paper argues that Tai Ping’s economies of scale, cross-selling synergies, and tight connections to banking accounted for the company’s success and distinguished it from its peers. To expand its market reach, Tai Ping forged partnerships with other companies and leveraged its relationship with its parent company. To improve its operating environment, it lobbied the Chinese government and played a leading role mobilizing the industry to form a cartel. Besides offering the history of an important firm, this paper also explores the broader context in which fire insurance operated. It examines how the indigenization of insurance in China unfolded, with Chinese companies like Tai Ping mediating the introduction of a new financial product, the transfer of new institutions, and the diffusion of new knowledge.

Fire Insurance in China: Indigenization and Dissemination

In 1929 when Zhou Zuomin entered the insurance business, he was already one of the leading financiers in China (see Figure 1). After stints in the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Communications (Jiaotong yinhang), he founded Jincheng Bank in 1917 and eventually made it the largest and most profitable private bank in north China. Such success made Zhou, according to one historian, “a driving force in the development of modern banking in China.”Footnote 9 A mix of pragmatism and idealism motivated his foray into insurance. At the time, Chinese-owned insurers—insurers with majority ownership by Han Chinese businessmen—were growing in number.Footnote 10 But as a company account later claimed, what companies that existed then were “careless and sloppy in their organization,” seemingly content to “sit by and watch the loss of [China’s] economic gains to foreigners while unable to compete effectively with foreign businesses.” This paucity of well-managed Chinese firms was especially worrisome for Zhou, given the stakes for China: “the insurance industry is related to the security of a nation’s economy and society [and] every country attaches great importance to it.”Footnote 11

Figure 1 Zhou Zuomin, founder of Tai Ping Insurance and Jincheng Bank

Source: Jincheng yinhang chuangli ershi nian jinian kan, 1937.

According to its founder then, Tai Ping was created to benefit from what he believed to be a profitable opportunity in a critical industry for his vulnerable country. Tai Ping supported Jincheng’s broader business but operated as a stand-alone enterprise and became a publicly traded entity. Initially capitalized at half a million yuan, it first sold fire, marine, and automobile insurance before later offering life insurance in 1934. Success came quickly. By 1935, the firm collected the second-most premiums on property insurance among all Chinese insurers. Tai Ping’s sudden growth, in the recollections of one manager, marked “an impressive display of power that made the financial world take notice” of the upstart.Footnote 12

Zhou’s initial assessment of the Chinese insurance industry was accurate but not entirely so. At the dawn of the 1930s, the largest insurance companies in China—measured by total capital, total volume of policies insured, and other metrics—were foreign owned.Footnote 13 The number of Chinese-owned insurers grew steadily but slowly. During the thirty-five years between 1865 to 1899, an estimated nine Chinese insurance companies were established and operating in China. During the following thirty-six years from 1900 to 1935, an estimated seventy-five Chinese insurance companies were established, averaging roughly two per year (see Table 1). Some of these enterprises went out of business almost as soon as they were founded, victims of intense competition or poor management. But by 1935, the number of Chinese firms stood at forty, twenty-five of which specialized in selling property insurance (see Tables 2 and 3). Chinese fire insurers like Tai Ping grabbed an increasing share of the market, and foreign insurers clearly felt the heat from the new market entrants. The British company Phoenix Assurance, a major player in the Chinese fire insurance market since the early nineteenth century, suffered what its corporate historian called “a fatal blow” during the 1930s under the relentless onslaught of native competition.Footnote 14 Sun Fire Insurance, another British company operating in China since the nineteenth century, pointed to “competition of serious Chinese undertakings” as the primary reason for the decline of its own business and that of foreign insurers more generally.Footnote 15

Table 1 Establishment of Chinese insurance companies (1865–1935)

Source: Zhongguo baoxian xuehui, Zhongguo baoxian bao, Zhongguo baoxianye, 27; Zhongguo baoxian nianjian, 1937, shangbian 198.

Table 2 Chinese insurance companies by type (1935)

Source: Zhongguo baoxian nianjian, 1937, shangbian 3.

Table 3 Chinese insurance companies (1935), yuan at current prices

Note: *Converted from Straits dollar (ST$) at ST$1 = CH$1.56336. **Converted from Hong Kong dollar (HK$) at HK$ = CH$1.31847. ***Originally listed as “very many” (shen duo). Estimates derived from counting number of cities with agencies by province.

Source: Zhongguo baoxian nianjian, 1937, shangbian 3-4. Cross rate exchange data calculated from Banking and Monetary Statistics, 667, 672, 679.

One way in which Chinese insurance companies challenged formidable foreign incumbents was through the spread of bancassurance, practice of banks selling insurance to their own clients. Bancassurance flourished during the “golden age” of Chinese banking in the 1920s and 1930s amid the wave of urban industrialization and the widespread embrace of Western-style banking institutions.Footnote 16 From the end of 1920 to 1929, the capital and deposits of Chinese banks increased by 141 percent and 210 percent, respectively. Seven years later in 1936 on the eve of war with Japan, these figures increased yet again by 90 percent and 210 percent, respectively.Footnote 17 Flushed with capital, many Chinese banks turned to insurance as an outlet for investment.Footnote 18 According to contemporary accounts, the rise of bancassurance was critical to the rise of the Chinese fire insurance industry; Chinese firms finally enjoyed sufficient financial backing to ensure that business was not entirely monopolized by foreigners.Footnote 19

Jincheng was a pioneer in the practice of bancassurance. When Tai Ping was founded, according to a company report, “it was not common for banks to concurrently manage insurance companies.”Footnote 20 But Tai Ping’s early success encouraged other banks to follow Jincheng’s example. Some banks like the Bank of China (Zhongguo yinhang) and the Bank of Communications established or spun off their own insurance subsidiaries. Other banks founded their own insurance companies through joint ventures with foreign investors. In 1931, the Shanghai Commercial Savings Bank (Shanghai shangye chuxu gongsi), the Chinese publisher Commercial Press (Shangwu yinshuguan), the Chinese industrialist Rong Zongjing, and the foreign conglomerate Butterfield and Swire (Taigu yanghang) together established China Assurance (Baofeng baoxian gongsi). The following year, a consortium of six Chinese banks together with Asia Life Insurance (Youbang renshou baoxian gongsi), owned by American businessman Cornelius Vander Starr, founded Tai Shan Insurance (Taishan baoxian gongsi) to sell both life and fire insurance.Footnote 21

Other drivers behind the growth of Chinese insurance companies included the growing recognition of risk management and the dissemination of insurance knowledge, both of which made insurance more intellectually acceptable. During the nineteenth century, a few writers introduced to the Chinese public the rudiments of Western insurance and its critical role in supporting long-distance trade.Footnote 22 By the early twentieth century, more writers argued for the importance of insurance to Chinese modernity. American-educated economist Ma Yinchu, who went on to play an important role formulating economic policy for both the Nationalist and Communist governments, popularized this view in a series of magazine articles and public lectures by explaining how insurance companies employed statistics to tame risk through proper calculation, distribution, and pricing.Footnote 23 Writings by Ma and others sought to demystify the logic behind the willingness of companies to shoulder massive risks from the public, thereby assuaging skeptics who likened insurance to gambling. Meanwhile, technical works on insurance— produced by Chinese writers themselves or translated from foreign writers like the American “father of insurance education” Solomon Huebner—were becoming more widely available and accessible. From 1925 to 1937, at least twenty-one titles on insurance were published, providing general surveys of life, marine, and fire insurance with contents ranging from translations of key concepts, to mathematical examples calculating annuities, to Chinese templates of insurance policies originally produced in foreign languages.Footnote 24

Chinese insurers made use of such knowledge and techniques with varying degrees of success. Chinese life insurers still struggled to effectively compete with their foreign counterparts in the absence of adequate Chinese mortality tables and actuarial statistics, even as research and publications on life insurance proliferated.Footnote 25 By contrast, Chinese fire insurers became increasingly adept at assessing fire-related risks. Many Chinese insurers adopted the widely used analytic schedule method (fenxi jisuan fa) pioneered by American insurance executive Albert F. Dean. This method graded properties based on location, function, and construction to assess and price the risk of conflagration. It proved especially attractive to Chinese insurers due to its flexibility and relative ease of use in various Chinese cities.Footnote 26 Rate schedules divided buildings within cities into different categories based on their construction material and function. Generally, they favored Western-style structures by charging lower premiums for modern buildings with four firewalls and higher rates for traditional wooden structures and specialized buildings like factories and theaters at greater risk of conflagration.Footnote 27 Chinese fire insurers thus embraced foreign actuarial techniques in understanding, classifying, and pricing risks and tailored them to suit domestic conditions.

Meanwhile, Chinese insurers became increasingly successful at persuading the public to take out coverage against fire-related risks. As in other parts of the world, consumers in China initially evinced little interest in insurance, either due to fear of courting misfortune by taking out a policy or unwilling to incur upfront costs to guard against an unlikely disaster.Footnote 28 Companies employed different strategies to overcome such resistance. Some relied on traditional promotions like calendar posters, colorful advertisements cheaply sold or freely dispensed by businesses in China to help elevate their brand names.Footnote 29 Others relied on marketing that helped highlight the efficacy of insurance itself. In one corporate publication from the mid-1930s, for instance, the China National Insurance Company (Zhongguo tianyi baoxian gongsi) appealed to customers on the “necessity of insurance” (baoxian zhi biyao) by highlighting the inherent hazards of living in a modern world:

A single spark can set a prairie ablaze.

The dangers of conflagrations are ever present.

Though buildings are sturdy and firefighting is thorough,

Careless electrical fires that could spread to neighbors are truly difficult to guard against.

Therefore, the hazards of fire can be resisted and the protection of property can be ensured,

Only if a fire insurance policy is taken out.Footnote 30

Such appeals proved especially persuasive, because the risk of fire grew with the transformation of Chinese cities. During the early twentieth century, many Chinese municipalities embarked on ambitious urban renewal projects by building new commercial districts (xinxing shangye quyu), demolishing city walls, and widening streets. Yet many more old quarters remained, with their narrow thoroughfares, encroaching stalls and storefronts, and traditional structures that lacked modern firewalls.Footnote 31 At the same time, urban industrialization increased the likelihood of conflagrations. The introduction of everything from volatile chemicals like kerosene, to consumer goods like matchsticks and cigarettes, to manufacturing hazards like electrical fires (zoudian) introduced new fire risks into Chinese cities already among the most populated and most dense in the world.Footnote 32 By the 1930s, many industry observers noted how these new hazards pushed the Chinese public to overcome whatever cultural biases it might have once held against fire insurance. “Owing to the nature of the risk and the serious proportions fires grow to be in the crowded cities,” China Assurance general manager Zhu Rutang (J. T. Chu) declared, “protection against such a risk is more commonly appreciated by the populace than any other class of insurance.”Footnote 33 Other contemporary accounts like the industry publication China Insurance Yearbook (Zhongguo baoxian nianjian) echoed Zhu’s claims on the popular acceptance of fire insurance, noting that among all types of insurance, “fire insurance is fairly developed in our country and is the mainstay of every [insurance] company’s business.”Footnote 34

Testimonies by the insured themselves also helped sway Chinese public opinion on the efficacy of fire insurance. Policyholders whose losses were covered were often required to take out advertisements describing the circumstances of their misfortune and attesting to how insurers made them whole. One such advertisement was placed by Hangzhou merchant Wang Chaozhen after a short circuit from the motor of a silk-weaving machine burned his factory, his inventory, and the buildings of his neighbors. Upon receiving his claims, Wang took out an advertisement on the front page of his local newspaper. It declared how he received CH$950 on a policy with coverage of CH$1,300 and thanked his insurer China Assurance, the company’s two managers, and the acquaintance who originally introduced him to the company: “Your humble servant feels satisfied and indebted enough to rely on [his own funds] to publish this formal expression of gratitude.”Footnote 35 Wang’s advertisement was not unique; other advertisements employed similar boilerplate language.Footnote 36 Such advertisements, though, conveyed to a potentially skeptical Chinese public that fire insurance was reliable, companies were solvent, and losses from calamities could be ameliorated.

Finally, the indigenization of insurance in China and the growth of Chinese-owned insurers during the 1930s coincided with a dramatic transformation of the legal environment. Through the early twentieth century, many insurance companies in China—foreign or Chinese owned—incorporated themselves in the British colony of Hong Kong as joint-stock enterprises, thereby enjoying not only limited liability but also British consular protection.Footnote 37 After coming to power in 1928, the Nationalist government sought to continue efforts by previous regimes to carve out a more assertive role for the state in the economy and roll back the unequal treaties that accorded many privileges for foreign firms—immunity from Chinese laws, regulations, and taxes. Given its perceived importance to China, insurance was a target of this legislative and regulatory effort. Among the spate of new laws drafted was the Insurance Enterprise Law (Baoxianye fa) (1935, revised in 1937), which mandated that all firms register with the government and drastically restricted the scope of operations for foreign insurers by requiring them to confine their operations to treaty ports.Footnote 38 Together with other laws and regulations, the Insurance Enterprise Law mirrored similarly protectionist measures introduced by other governments around the world to exercise greater oversight of foreign insurers and the industry as a whole.Footnote 39 Although their enforcement was ultimately postponed by the outbreak of war with Japan in 1937, new controls in China were part of a global trend of governments grappling with ways to regulate an industry that had encountered few restrictions before the twentieth century.

The Rise of Tai Ping: Fledgling Upstart to Industry Leader

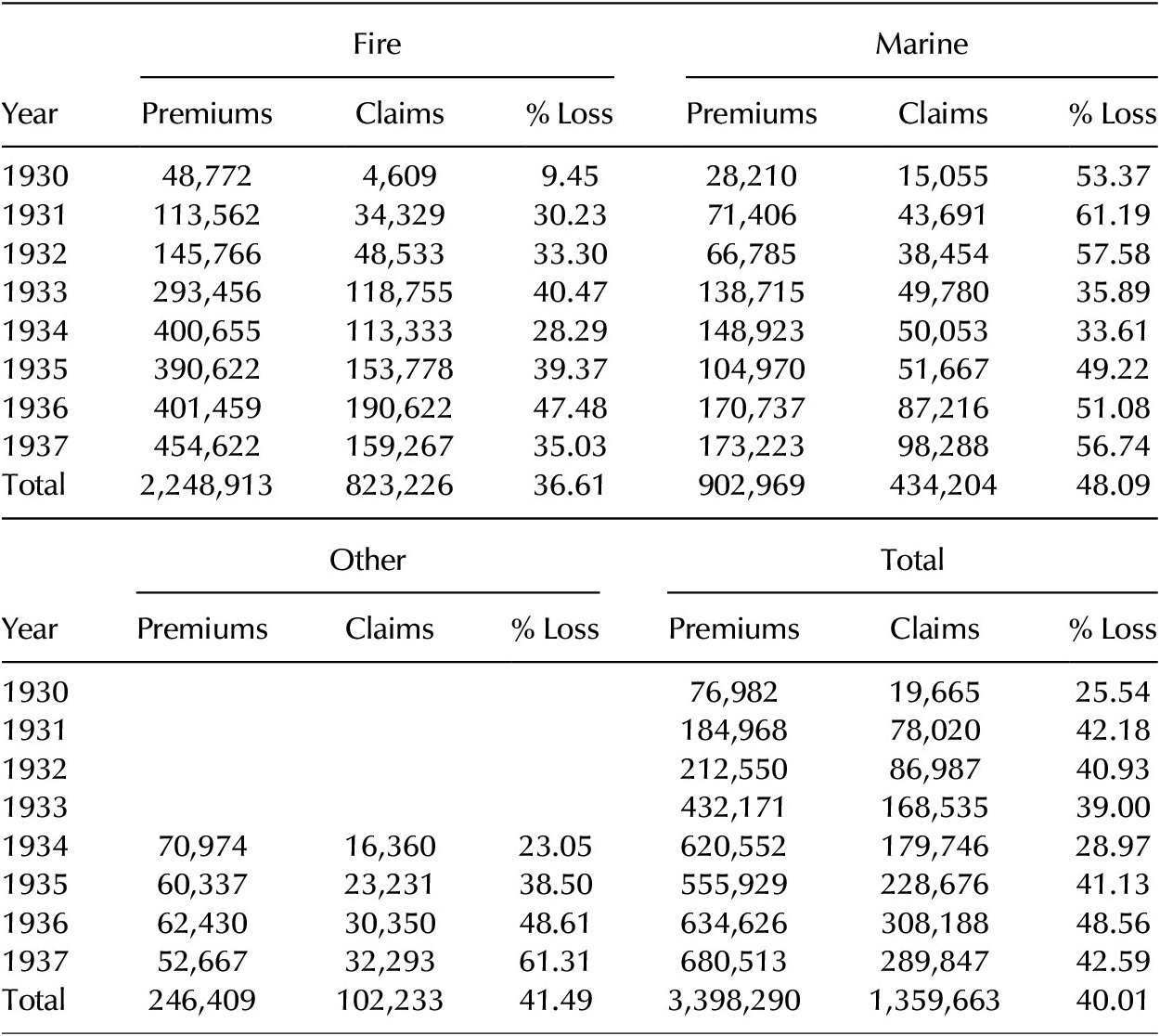

Tai Ping benefited from broader developments that led to the proliferation of Chinese-owned insurers and embrace of insurance in China. Yet it still managed to distinguish itself by achieving fast growth and maintaining low losses. Its net profits rose from CH$57,526 in 1930 during its first full year of operation to CH$149,245 in 1933—a threefold increase in as many years (see Table 4). Its premiums registered even faster growth. In 1930, Tai Ping collected CH$76,982 in premiums from all property insurance, CH$48,772 of which were premiums from fire insurance. Three years later in 1933, those figures jumped to almost fivefold to CH$432,171 and CH$293,456, respectively. Four more years later in 1937, these figures increased yet again, despite the outbreak of war with Japan, to CH$680,513 and CH$454,622, respectively. Throughout the first eight years of its operations, Tai Ping’s actual loss ratios for all property and fire insurance policies—that is, claims paid as a proportion of premiums collected—stood at 40.01 percent and 36.61 percent, respectively (see Table 5).

Table 4 Tai Ping Insurance Company profits and capital (1930-1936), yuan at current prices

Note: *Data include profits from life insurance from 1934. **Tai Ping attracted 2 million in additional capital in September 1933. On a prorated basis—i.e., eight months of capital at 500,000 and four months of capital at 2,500,000—return on capital was 12.24%.

Source: Jincheng yinhang shiliao, 1983, 296–297.

Table 5 Tai Ping Insurance property insurance premiums, claims, and loss ratios (1930–1937), yuan at current prices

Source: Taiping baoxian gongsi, various issues, SHMA, Q334-1-239.

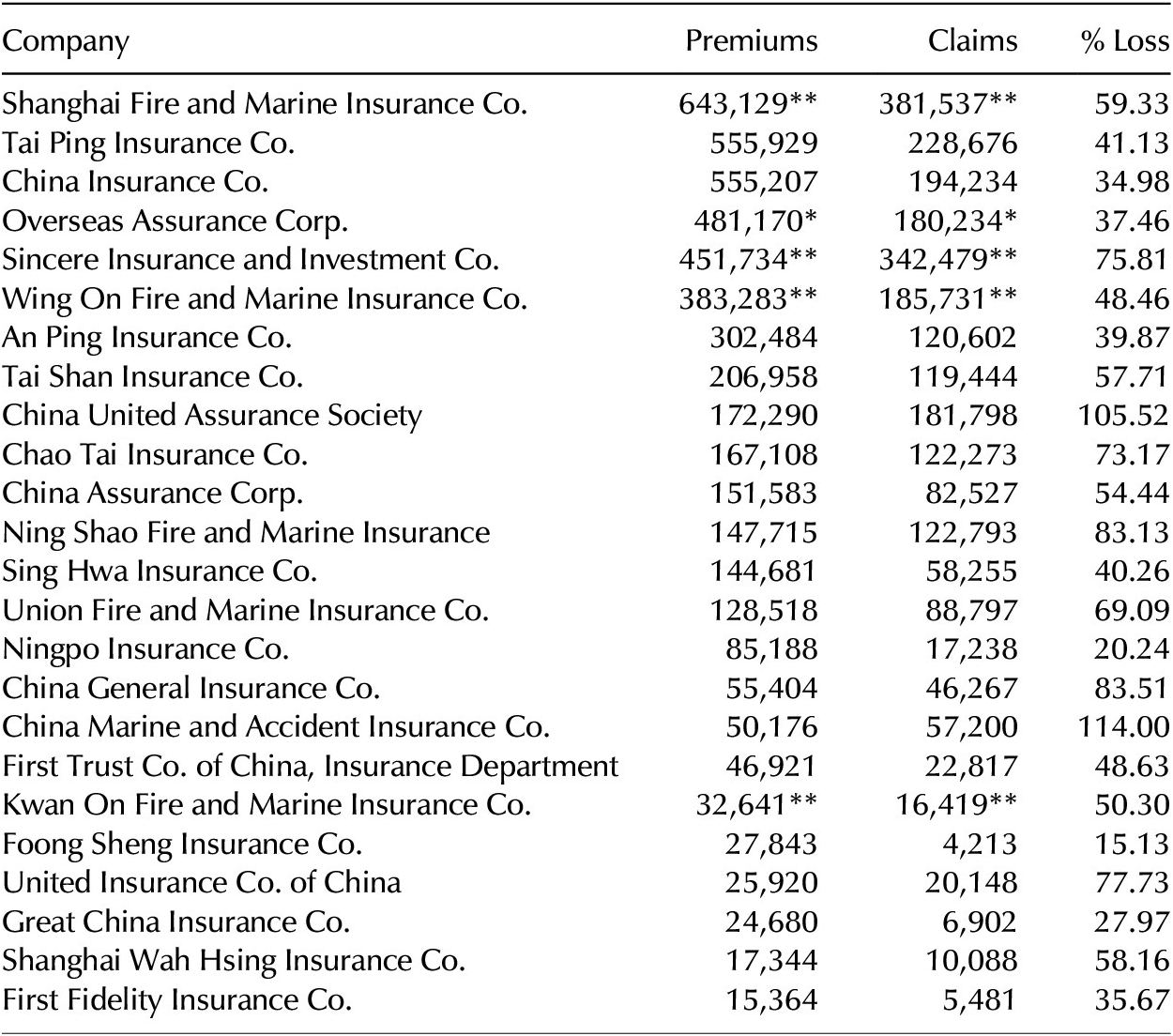

Tai Ping’s financial performance was even more exceptional when placed within the context of the larger industry (see Table 6). In 1935, Tai Ping collected the most property insurance premiums among all Chinese insurers except for Shanghai Fire and Marine Insurance, a more established company founded decades before in 1915.Footnote 40 Its loss ratio of 41.13 percent for all property insurance policies that year was just over three-quarters of the loss ratio of 53.68 percent for the entire industry. While eight other firms enjoyed lower loss ratios than Tai Ping’s loss ratio, all but the state-owned China Insurance Company (Zhongguo baoxian gongsi) were smaller enterprises that collected fewer premiums. Tai Ping, in other words, was not only one of the largest Chinese insurance companies; it was also one of the most efficiently operating Chinese insurance companies, able to minimize losses relative to its peers.

Table 6 Property insurance premiums, claims, and loss ratios (1935), yuan at current prices

Note: *Converted from Straits dollar (ST$) at ST$1 = CH$1.56336. **Converted from Hong Kong dollar (HK$) at HK$1 = CH$1.31847.

Source: Zhongguo baoxian nianjian, 1937, shangbian 204. Cross rate exchange data calculated from Banking and Monetary Statistics, 667, 672, 679.

Tai Ping leveraged this early success to fortify its capital base and expand its market share through acquisitions. In 1933, Zhou invited five major banks—Communications, Dalu, Zhongnan, Guohua, and Donglai—to invest in Tai Ping, increasing the company’s capital sixfold to 3 million yuan.Footnote 41 In late 1933, Tai Ping assumed control over An Ping Insurance (Anping baoxian gongsi) after An Ping’s parent company Donglai Bank became a major investor. A few months later in 1934, Tai Ping snapped up Foong Sheng Insurance (Fengsheng baoxian gongsi) at a bargain price when Foong Sheng Industrial Company (Fengsheng shiye gongsi) sought to dissolve its small subsidiary.Footnote 42 Both An Ping and Foong Sheng maintained relatively low loss ratios and already possessed large retail networks that dwarfed those of larger peers. They also maintained significant presence in the lucrative south China market, thereby complementing Tai Ping’s primary markets in the north.Footnote 43 While Foong Sheng had been a minor player in the industry, An Ping heretofore was one of the largest and most successful Chinese property insurers. The acquisition thus represented a substantial coup for Tai Ping. Before the outbreak of war in 1937, Tai Ping absorbed two more firms: the China National Insurance Company (Zhongguo tianyi baoxian gongsi), a subsidiary of Kenye Bank, and the United Insurance Company of China (Huashang lianhe baoxian gongsi), a joint venture of ten other Chinese insurance firms.Footnote 44

Supervising this growing business empire was a small management team. Throughout the 1930s, Zhou Zuomin served as Tai Ping’s general manager and exercised ultimate authority over the company’s strategic direction. But as he was primarily focused on Jincheng’s business and frequently away in north China, Zhou turned Tai Ping’s day-to-day operations over to two lieutenants. One was Ding Xuenong (H. N. Ting), whose family included prominent members of the Qingdao business community and who had worked at the Bank of Communications and Bank of China before joining Tai Ping in 1929 as first assistant manager.Footnote 45 The other lieutenant was Wang Boheng (K. P. Wong), who worked as secretary for the Beijing Bankers Association for almost a decade before joining Tai Ping in 1933 as second assistant manager. The pair worked together until 1942, and by Wang’s own recollections, the partnership was amicable and productive. “Ding’s personality was stronger, and I proposed an agreement whereby if the two of us could not see eye-to-eye, we would put aside any issue and wait until we were calm to discuss it again. This is how in nine years [we] settled many problems and lived in harmony with each other.”Footnote 46 Ding and Wang served concurrently as assistant managers for Tai Ping, An Ping, Foong Sheng, and other subsidiaries, overseeing a nationwide business divided into six major markets, each carefully monitored by auditors dispatched from shareholding banks.

Given its size and preeminence among Chinese-owned insurance companies, Tai Ping played an important role in further indigenizing and popularizing insurance in China. The company was a critical disseminator of insurance knowledge. It sponsored reference materials like Fire Insurance (Huozai baoxian), a comprehensive textbook authored by company counsel Wang Xiaowen with input from assistant managers Ding Xuenong and Wang Boheng and included as part of the company’s “Series on Insurance” (baoxian congshu).Footnote 47 Tai Ping also published its own magazine, Insurance World Bi-Weekly (Tai An Feng baoxian jie), which featured detailed articles on the workings of insurance alongside general industry and company news. Such articles included “Summary of Insurance Practices” (Baoxian shiwu gaishu), penned by an industry veteran with more than twenty years of experience. The eight-part series was aimed at helping readers still “dumbfounded” (chengmu jieshe) by the actual mechanics of fire insurance and proffering useful advice on every aspect of operations: assessing risk, underwriting policies, investigating fires, settling claims, and so forth.Footnote 48 Other articles such as the twenty four-part series “A Thorough Discussion of Problems with Fire Insurance Investigations” (Huoxian chayan wenti zhi jiantao) or the thirty-part series “Some Key Terms in Fire Insurance” (Huozai baoxian zhong zhi ji ge mingci), were written in the same spirit. They communicated abstract insurance concepts, supplementing them with useful techniques and knowledge from practitioners in the field.Footnote 49

Tai Ping also played an important role in insurance legal reforms. In doing so, it followed the example of its parent company Jincheng, which assumed leadership positions in major banking associations.Footnote 50 Tai Ping was an influential member of the Shanghai Insurance Association (SIA; Shanghai shi baoxianye tongye gonghui), a trade group founded in 1907 and composed of the most prominent Chinese insurance firms. Because it was based in China’s financial center, the association exercised considerable influence nationwide and served as a key intermediary between its members and the government. For instance, the SIA successfully lobbied the Nationalist government to order all government properties and state-owned enterprises to insure themselves with Chinese insurers, rather than with foreign insurers.Footnote 51 During the 1930s, the SIA also advised the government in its efforts to reform insurance laws, convening a dedicated committee to consult with officials. The seven-member committee was led by Tai Ping assistant manager Ding Xuenong with six other Chinese insurance executives and joined by Tai Ping counsel Wang Xiaowen. The committee sought to persuade the government to exempt the industry from certain taxes and modify various pieces of insurance legislation. While unsuccessful in realizing the former aim, it succeeded in realizing the latter. The committee worked closely with officials in the capital and offered recommendations that were eventually ratified as the Revised Insurance Enterprise Law.Footnote 52

Drivers of Success: Economies of Scale and Strategic Partnerships

Business historians have often employed the concept “economies of scale” to describe the efficiencies manufacturers derived from lowering the costs of operation as they increased overall volume of production.Footnote 53 The case of Tai Ping, however, shows how insurers could also achieve similar economies of scale by driving down their own operating expenses even as they increased their underwriting volume. One favored strategy was to forge strategic partnerships and leverage synergies with its subsidiaries and with affiliates of Jincheng. In 1935, Tai Ping joined with An Ping and Foong Sheng to form the Tai-An-Foong General Controlling Office (Tai An Feng zongjingli chu), a partnership that collectively managed the three companies’ businesses and expanded their product offerings and geographic reach. While each company reported its finances separately, the three companies underwrote policies collectively. The Tai-An-Foong partnership sold policies through Tai Ping’s fourteen branches and 788 agencies spread out across 224 cities across China—the largest network among all Chinese-owned insurers (see Table 3). This partnership also marketed bancassurance through branches of Jincheng, Communications, and other partner banks.Footnote 54 Unlike some competitors who did not enjoy tight-knit relationships with banks, Tai Ping’s employed existing bank retail networks as a marketing channel with minimal upfront capital costs and thereby achieved economies of scale.

The Tai-An-Foong partnership created a shared corporate brand that parlayed Tai Ping’s reputation to the benefit of its subsidiaries. Both An Ping and Foong Sheng employed Tai Ping’s catchy slogan that capitalized on the double-meaning of the company’s name: “Tai Ping Insurance ensures peace and tranquility” (Taiping Baoxian, baoxian taiping).Footnote 55 They employed Tai Ping’s distinctive logo, a black-and-white yin-yang symbol (taijitu) based on Daoist traditions and affixed with the declaration: “Chinese insurance company” (Huashang baoxian gongsi) (see Figure 2). Explicitly and implicitly, the company represented itself as a Chinese concern and made national identity a critical selling point. Its marketing mirrored that of many other early twentieth-century Chinese companies in linking Chinese nationalism with everyday consumption.Footnote 56

Figure 2 Tai Ping logo. Tai Ping’s name is encased within the yin-yang symbol from Daoist traditions. The text in the outer circle reads: “Chinese insurance company.” The logo directly communicates to customers the national identity of the company.

Source: Shen Bao, March 4, 1935, 1.

Chinese nationalism also suffused much of its corporate rhetoric. Zhou Zuomin claimed he founded Tai Ping because more Chinese-owned insurers were urgently needed. Assistant manager Wang Boheng boasted that the company never employed foreign consultants, unlike other Chinese-owned firms.Footnote 57 Yet this promotion of Chinese nationalism—undoubtedly sincere—was not the same as the outright rejection of all things foreign. Zhou himself received his formative education in Japan, and his company eagerly sought to participate in the global diffusion of insurance knowledge by sponsoring the translation of foreign texts and dispatching promising employees to study abroad.Footnote 58 Meanwhile, Tai Ping forged working relationships with foreign insurers, especially in the business of reinsurance. Just like insurers elsewhere, insurers in China needed reinsurance to transfer risks and thereby free up capital to underwrite more policies. Although a consortium of Chinese insurers sought to offer reinsurance to its peers, only foreign insurers possessed the necessary capital to provide reinsurance in sufficient volume and at economical rates.Footnote 59 Tai Ping accordingly concluded reinsurance contracts with companies like Swiss Re and Sun Fire Insurance, wielding its growing clout to negotiate for very favorable rates.Footnote 60 In an annual shareholder report, Tai Ping boasted of its “mutually beneficial” (gongtong huhui) agreement with Swiss Re that enabled the company to overcome traditional limits on business from which other Chinese insurers suffered.Footnote 61 A manager later recalled that success in securing favorable reinsurance terms reflected the strong financial health of Tai Ping, propelling it to “become one of the most well-known insurance companies in the world.”Footnote 62

Tai Ping also leveraged its synergies with other companies under Zhou Zuomin’s corporate umbrella, cross-selling different products and inserting itself into everyday business transactions, especially in sectors of the Chinese economy like transportation that required insurance. In the city of Zhengzhou, for instance, Tai Ping dominated the local market by bundling insurance as part of a broader menu of services and products. To cater to merchants in this key railway junction in the Chinese heartland, Tai Ping worked closely with Jincheng Bank and the Tongcheng Company (Tongcheng gongsi), a transportation company owned by Zhou with twenty-eight warehouses across north China. Together, they fielded a full-time staff dedicated to helping clients navigate every step of the shipment process—from dealing with administrative paperwork, to packing, to consignment. They rented out space in a large warehouse near the rail yards to house the shipments. This wide array of offerings helped Tai Ping sell to a more targeted client base, as trains accepted shipments of cotton, peanuts, wool, and other potentially flammable commodities only after they were insured. And because local merchants already relied on Jincheng for financing and Tongcheng for shipment, taking out an insurance policy from Tai Ping was both logical and convenient. Tai Ping enjoyed a strong business selling fire insurance, while Tongcheng earned “large profits” (houli) on rents from its warehouse.Footnote 63 In some cases, Tongcheng simply included a separate charge for insurance as part of its warehouse rental fee and forwarded the proceeds to Tai Ping.Footnote 64 Tai Ping—along with Jincheng, Tongcheng, and partners like Communications Bank—replicated this cross-selling business model along other major railway routes, including the Beijing–Baotou line (Jing-Bao tielu) and the Beijing–Guangzhou line (Jing-Guang tielu) and did “very flourishing business” (yewu hen wei fada) in the recollections of a former employee.Footnote 65

Interfirm cooperation within the Zhou business empire not only facilitated cross-selling but also the sharing of crucial market intelligence. Zhou fully intended Tai Ping to play a key role in supporting the businesses of Jincheng and Tongcheng—and vice versa. The three companies formalized their relationship in a “general plan for mutual assistance” (huzhu dagang) that outlined how they were to cooperate on directing prospective customers of insurance, banking, and transportation (especially for cotton and coal) to one another. The plan even called for each company to select representatives to meet biweekly with their counterparts and exchange views over a meal.Footnote 66 Interfirm cooperation helped Tai Ping deal with the fundamental problem of information asymmetry in insurance that made underwriting difficult. It thus benefited from Jincheng’s and Tongcheng’s intimate knowledge of their clients’ finances and operations, given their respective roles as lender and warehouser. According to investigations by Sun Fire Insurance, tight connections with Jincheng and Tongcheng placed Tai Ping “in a very favorable position to ascertain the financial standing of their insured.”Footnote 67 Such familiarity with the financial standing of their clients, in turn, enabled Tai Ping to properly price policies and thereby minimize the many insurance risks associated with information asymmetry and moral hazard.

Effective cross-selling and coordination gave Tai Ping a competitive edge over its rivals. While this business strategy was seemingly simple, it was not easily replicated—even by firms with redoubtable financial backing. One such firm was China Assurance, the joint venture between Shanghai Commercial Bank and foreign conglomerate Butterfield and Swire. Founded two years after Tai Ping, China Assurance enjoyed similar advantages. It was initially capitalized at half a million yuan and benefited from the widespread uptake of insurance across the country during the 1930s. Like Tai Ping, it also enjoyed a close relationship with its own parent company, the Shanghai Commercial Bank. The Shanghai Commercial Bank required all properties mortgaged as collateral for loans and all goods stored in warehouses to be covered by China Assurance policies, thus giving China Assurance captive customers.Footnote 68 But while China Assurance remained an important player in the property insurance market, it never matched Tai Ping in size. Its own retail network of eleven branches and thirty-nine agencies was the sixth largest among Chinese insurers in 1935. But it was dwarfed by Tai Ping’s network of fourteen branches and 788 agencies—figures that did not even include the networks of subsidiaries like An Ping and Foong Sheng. Furthermore, the premiums China Assurance collected from all property insurance and fire insurance in 1935—CH$151,583 and CH$137,532, respectively—were roughly one-third of the same premiums Tai Ping collected in the same year.Footnote 69

Tai Ping’s competitive advantage over non-banking competitors was even more pronounced. The spread of bancassurance benefited banks that added insurance as an auxiliary business and could thus offer a broader menu of financial products. This worked to the detriment of non-banking enterprises selling insurance as a stand-alone product. One such company was the China General Insurance Company (Da Hua baoxian gongsi), established in 1928 by the industrialist Liu Hongsheng. Liu’s business empire included matches, cement, and wool factories. While China General did receive some seed capital from Shanghai Commercial Bank, it was founded by Liu with the aim of insuring his own industrial enterprises. Liu was especially keen for China General to recoup some of the vast premiums he paid to other insurers, particularly to foreign insurers. He soon discovered, however, the limits of this strategy. As one of Liu’s managers Chen Baoqi recalled: “At first, the properties of the enterprises owned by Liu Hongsheng insured with China General. Nevertheless, they did that less and less frequently. One important reason was that when enterprises borrowed from banks and used their properties or goods as collateral, the mortgaged properties or goods could only be insured with insurance companies assigned by the banks. Consequently, they could not be insured by China General.”Footnote 70 In other words, China General encountered difficulties ensuring affiliated enterprises because of the increasingly interlocking relationships between banking and insurance that companies like Jincheng and Tai Ping enjoyed. As a result, China General remained a small player in the insurance market, collecting CH$55,404 in property insurance premiums in 1935, or less than 10 percent of what Tai Ping collected during the same time.Footnote 71 Even an enterprise backed by one of the most successful businessmen in China could not crack a market increasingly dominated by banks. Tai Ping’s strategic partnerships thus not only provided critical market channels but also constituted formidable barriers to entry.

Retailing Insurance: Controlling Brokers and Attempting Cartelization

The growth of Tai Ping during the 1930s coincided with changes in the retail landscape and tentative steps taken by the fire insurance industry at self-regulation through the formation of cartels. Insurance in China was sold primarily by agents (dailiren) and brokers (jingjiren or qianke). Agents were formal employees of insurance companies who were paid a fixed salary and only sold policies issued by their employers. Brokers, by contrast, were not employed by insurers themselves but worked on behalf of clients to purchase policies from different companies. Just as they did elsewhere, both agents and brokers played a pivotal role in the Chinese insurance industry as middlemen who drummed up sales, interpreted policy provisions, and collected premiums. They effectively conducted much of the necessary footwork connecting companies with prospective customers.Footnote 72

Tai Ping sought to build its own army of professional agents and thereby better control how its policies were marketed, underwritten, and sold. Until the fall of Shanghai to the Japanese in December 1941, it regularly held public examinations to hire college and secondary school graduates and trained them on the fundamentals of insurance. The company’s central office then dispatched trained agents to handle all underwriting-related work in local markets. There, they were paired with “powerful and influential” (chi de kai) notables also recruited by Tai Ping to drum up sales within local business circles.Footnote 73 Because these notables were hired for their personal connections rather than for their technical knowledge of insurance (which could be nil in some cases), trained agents were critical to company efforts to monitor local branches and ensure that they underwrote policies commensurate with the risks assumed. Cultivating and deploying a professional staff represented one strategy Tai Ping pursued to overcome the principal–agent problem that often attenuated central control over local branches.

Despite such efforts, the number of trained agents proved insufficient to staff Tai Ping’s nationwide retail network. Tai Ping—like all other insurers in China—thus relied on independent brokers for much of its business. This reliance could be traced back to the introduction of insurance in China during the early nineteenth century, when foreign firms turned to Chinese intermediaries for their local knowledge to navigate local markets and solicit local businesses. Foreign insurers also turned to independent brokers to minimize operating expenses by extending market reach without the necessary costs of opening and maintaining branch offices in different locales. This practice endured into the twentieth century and was maintained by Chinese insurers themselves, who also sought to minimize operating expenses. While the size of brokerages varied—many brokers worked alone but some operated independent agencies—they all performed mundane but critical roles in selling insurance to the public .Footnote 74 “The vicissitudes of the insurance industry,” declared an article in Bankers Weekly (Yinhang zhoubao), “truly rest in the hands of these people.”Footnote 75

While insurers and brokers had a common interest in maximizing sales, they sometimes worked at cross-purposes. Brokers relied on commissions (yongjin), which were based on a system of rebates whereby they secured discounts off gross rates offered by insurers and sold policies at a higher net rate to customers. The difference between the discounted gross rate and the actual net rate was then pocketed as commission. In the face of intense competition, however, brokers often resorted to rebating the discount to the insured and then demanding additional discounts from the insurer—even as the insurer still assumed the responsibility for paying any claims in full. According to China Assurance general manager Zhu Rutang, discounts off gross rates for fire insurance once hovered around 20 percent, but by the mid-1930s, they had reached 90 percent. The insured effectively paid only 10 percent of the gross rate and “always wanted to bargain for a higher discount on renewal.”Footnote 76 Another foreign insurance executive noted: “Rebating is an accepted thing in Chinese business. I do not think that any business is ever written by Chinese agents without the commission being rebated.”Footnote 77

Despite such declarations, the reliance on brokers and the practice of rebates was actually not unique to China and was quite common in the business of insurance elsewhere.Footnote 78 Still, such arrangements in China exerted considerable downward pressure on rates to the detriment of insurers. Tai Ping’s annual shareholder reports regularly complained of broker discounts driving down fire insurance premiums, which accounted for the bulk of the company’s earnings.Footnote 79 The company also worried that tenuous control over brokers left it financially vulnerable. In an article in Insurance World Bi-Weekly, Tai Ping acknowledged that brokers were adept at selling insurance to many companies and customers. Yet it also warned that their qualifications and knowledge of insurance left much to be desired. Brokers, the article claimed, were only concerned with short-term gains by their maximizing commissions through maximizing sales volume. They offered ruinous discounts to any customer regardless of the actual risks they faced, thereby sowing “confusion” (wenluan) in the market.Footnote 80 Another article lamented that coverage for similarly risky properties charged different rates because of varying discounts offered by brokers, thus leading to mispriced policies and magnifying the potential for losses and even insolvency.Footnote 81

The Chinese public expressed similar misgivings, although their concerns centered less on the profitability of companies and more on the trustworthiness of brokers. Despite their claims that they were on the side of the insured, many brokers were held in low public esteem.Footnote 82 Indeed, given the diverse ranks of brokers—who included everyone from established professionals to fly-by-night operators with more questionable ethics—stories of fraud and other unscrupulous behavior circulated widely and generated considerable suspicion of insurance middlemen. In recounting the numerous cases of insurance premiums being misappropriated instead of being passed on to companies on behalf of policyholders, for instance, one newspaper declared of brokers: “Those who are honest and conscientious are not a few, yet there are others who have never hesitated to defraud either the companies or the insured.”Footnote 83 Putting aside their veracity, such claims reflected a broad distrust of independent brokers. Furthermore, because brokers often served as the face of insurers to the public, their notoriety damaged the public image of the insurance industry as a whole.

To confront the problem of unreliable brokers and relentless price cuts, governments in other countries sought to institute more regulations while insurers formed cartels to regulate brokerage, set rates, and ultimately disperse risk.Footnote 84 Similar efforts unfolded in China during the 1930s, with controls introduced from both the government and the industry. The 1935 Insurance Enterprise Law, for instance, required all brokers to register with the Ministry of Industry or obtain a license before they were permitted to ply their trade. It also stipulated that registered brokers could undertake the business of introducing customers but only for insurance companies that were themselves registered with the government. Such provisions applied to brokers working for any insurance company, foreign or domestic. Violators were fined CH$1,000.Footnote 85

Chinese fire insurers, for their part, took tentative steps at self-regulation by trying to form their own cartels. This required cooperating with an unlikely ally, namely foreign fire insurers, who still maintained a significant share of the market and were similarly hurt by ruinous price wars and unreliable brokers.Footnote 86 In Shanghai, cooperation between the two sides was spearheaded by the SIA and the Shanghai Fire Insurance Association (SFIA; Shanghai huoxian tongyehui), the trade group made up of foreign fire insurance companies. The two associations held intermittent discussions as early as 1928 on ways to raise fire insurance rates and regulate brokers. Together, they even produced a new fire insurance rate schedule in September 1931 that standardized premiums by grading different buildings according to their type and construction within different zones in the city. They also standardized rules for underwriting.Footnote 87 Such reforms were intended to harmonize rates and underwriting procedures among fire insurers, although Chinese and foreign insurer policyholders still paid different rates. The reforms were also intended to promote more price transparency and narrow variances between gross rates and net rates, ultimately limiting the magnitude of discounts brokers could offer.

The industry, however, still lacked provisions governing brokers. According to industry observers, brokers continued offering substantial discounts on gross rates and engaged in what companies considered questionable practices in securing their commissions by any means necessary. To tackle this problem, the SIA in May 1932 elected a special committee—one of whom was once again Tai Ping assistant manager Ding Xuenong—to work closely with the SFIA’s own special committee. Discussions to formulate new rules continued for years between the two associations and were eventually joined by another party—the brokers themselves. While understandably ambivalent about potential restrictions on their activities and limitations on their commissions, brokers hoped to shape new rules to serve their interests. They did so by relaying their concerns to both the SIA and the SFIA and establishing a trade association of their own.Footnote 88 According to the broker Guo Peixuan, new rules were not only necessary for the industry but could even benefit brokers themselves. Unrelenting discounts, Guo observed, left the industry “in a very sorry plight.” Contrary to the claims of companies and the perceptions of the public, commissions from rapidly declining premiums were quite low and subjected the vast majority of brokers to “feel deeply the kind of bitterness that no life can endure.” Furthermore, according to Guo, new rules could require stricter qualifications, thereby excluding less-qualified and less-reputable brokers from the industry. This might eventually raise the public standing of brokers in China to the level of their counterparts in Europe and the Americas. In sum, brokers like Guo believed that a modicum of regulations could bring order to the fire insurance market by stabilizing rates, improving the quality of brokers, and ultimately guaranteeing bigger commissions.Footnote 89

Discussions bore fruit in May 1936 with the publication of Rules for the Regulation and Management of Fire Insurance Brokers (Huoxian jingjiren zhi dengji yu guanli guizhang). The new rules stipulated that all brokers in Shanghai had to register and place a deposit of CH$500 with a joint committee established by the SIA and the SFIA, thereby discouraging brokers lacking sufficient funds or the requisite company sponsorship from formally underwriting insurance. They also limited commissions to 20 percent and capped discounts off gross rates at 85 percent. New rules also included penalties for brokers committing any violation, including a fine of CH$50 or even cancellation of their registrations.Footnote 90 At the same time, both associations agreed to raise fire insurance rates by 50 percent for foreign-style dwellings (zhuzhai), traditional Chinese residences (shikumen), and storefronts (dianpu) to properly adjust for the riskiness of policies formerly sold at steep discounts. As a show of industry unanimity, the SIA and the SFIA jointly issued public notices affirming the new regulations and new rates effective immediately.Footnote 91 Companies that supported the new rules also reinforced this message. Tai Ping, for instance, took out a full front-page advertisement in the Shanghai daily Shen Bao informing policyholders and prospective customers of the new changes adopted by the city’s insurance associations. While expressing gratitude for the public’s support since its founding, Tai Ping declared that new rules would rectify the “numerous and disorderly” (fenluan) discounts on fire insurance that had adversely affected business and assured clients of the company’s continued “faithful service” (zhongcheng fuwu).Footnote 92

Despite such initial fanfare, enforcement of the new rules was disrupted by the outbreak of war with Japan one year later in July 1937. Nonetheless, market observers took heart at a few encouraging developments. Many Shanghai brokers complied with the new rules, as more than three hundred of them submitted to new registration procedures by the end of 1936.Footnote 93 Insurance executives were also initially optimistic. Zhu Rutang, general manager of China Assurance and a member of SIA’s special committee responsible for drafting the rules, declared that reforms had “functioned with fair success [and] attracted the attention of thinking insurance people in all parts of China.”Footnote 94 A foreign executive at Sun Fire Insurance expressed skepticism that the new rules were being universally followed six months after their promulgation but admitted that reforms still “brought a better tariff situation in Shanghai than has existed for many years past.”Footnote 95 Indeed, Shanghai’s announcement served as an example for the entire country, as insurance associations in other commercial centers like Hankou and Tianjin solicited advice from the SIA for their own efforts at regulating local brokers or setting rates.Footnote 96 Although industry leaders like Zhu later lamented that the new rules did not go far enough, their initial optimism on the benefits of joint action and cartelization were still well founded.Footnote 97

Conclusion

Tai Ping’s reputation was forged in the crucible of competition during the early twentieth century. While benefiting from the indigenization of fire insurance that had been unfolding in China for nearly a century, the company distinguished itself by leveraging its tight links with its parent company’s business empire. Other Chinese insurers also enjoyed ties to other banks or even substantial financial backing of their own, but none proved as successful as Tai Ping in exploiting their economies of scale. Tai Ping also played a leading role in making the knowledge and embrace of fire insurance widespread throughout Chinese society and business. To be sure, Tai Ping’s success was not complete. Like other Chinese fire insurers, it could not adequately control brokers to staunch ruinous discounts. But the company spearheaded industry reforms and attempts at cartelization that might have helped ameliorate such problems were they not disrupted by all-out war.

The case of Tai Ping and the Chinese fire insurance industry shows how the indigenization of insurance in China meant more than just the transplantation of a new financial product or its associated institutions.Footnote 98 Moving in tandem with the global spread of capitalism, it also encompassed the translation and acceptance of a new worldview that recognized, financialized, and quantified sources of risks. Indeed, as business historians Philip Scranton and Patrick Fridenson note, reconceptualizing risk as a quantifiable distribution of possible outcomes is a distinctly modern development linked to the growth of insurance.Footnote 99 For Chinese insurers, indigenization was the steady mastery of the insurance business and the widespread adoption of foreign actuarial techniques that were in turn tailored for the Chinese environment by creating new categories of riskiness. It also meant confronting challenges like information asymmetry and the principal–agent problem that are fundamental to the operation of insurance and manifested themselves in everyday business. The indigenization of fire insurance in China thus accords with the contention by scholars like Sherman Cochran that non-Western enterprises did not passively imitate but actively adopted and repurposed Western business practices and organizational structures to suit local conditions.Footnote 100

The history of Tai Ping and the Chinese fire insurance industry more generally offers another example of both institutional convergence and institutional divergence Elisabeth Köll identified as common to the development of other industries in China during the early twentieth century.Footnote 101 On the one hand, Chinese insurance companies demonstrated institutional convergence with their global peers in their business practices, attempts to cooperate, and efforts at controlling brokers. But they also demonstrated institutional divergence owing to their own historical experience, as well as China’s semi-colonial environment that accorded an outsized role for foreign insurers while greatly limiting government efforts to regulate the industry. Focusing primarily on the experiences of Western multinational firms, scholars have concluded that the internationalization of insurance was disrupted or even halted with the outbreak of World War I.Footnote 102 Yet the history of Chinese insurers like Tai Ping and the rise of native competition reveal a broader story that shows how this internationalization continued apace through the early twentieth century, albeit in a different guise and from a different perspective. The indigenization and internationalization of insurance, in other words, were not mutually exclusive processes but unfolded in tandem in “peripheral markets” like China that continued to be drawn into the global economy.

The outbreak of war with Japan in 1937 did not mark the end of Tai Ping’s or Zhou Zuomin’s stories. Both the company and its founder, in fact, would successfully weather the turbulence of early twentieth-century China. Zhou became one of the many “red capitalists” who opted to remain in China after the 1949 Communist Revolution. Despite his suspect class status, he found a comfortable place in the new order, serving as a special deputy (teyao daibiao) to the National People’s Congress shortly before passing away in 1955.Footnote 103 As for Tai Ping, the company managed to remain in business throughout the war but saw its business shrivel with runaway inflation during the 1940s. It was reorganized as a joint state–private enterprise in 1951, becoming a subsidiary of People’s Insurance Company of China (PICC; Zhongguo renmin baoxian gongsi) in 1956 before ceasing operations shortly thereafter. When China embarked on economic reforms in 1979, PICC’s Hong Kong and Macao insurance operations were spun off into an independent company and later rechristened under the Tai Ping name. This new China Taiping—a Chinese state-owned insurance conglomerate based in Hong Kong and member of the Fortune Global 500—has only tenuous connections to its namesake.Footnote 104 Still, even if the original Tai Ping has not survived, its enduring appeal and successful reputation live on.