1. Introduction

This empirical study falls under the umbrella of language learning in the “digital wilds,” an emergent subfield in computer-assisted language learning (CALL) that focuses on “[digitally] enhanced out-of-class learning” (Sauro & Zourou, Reference Sauro and Zourou2019: 1). As “non-instructionally oriented contexts [of language learning]” (Thorne, Sauro & Smith, Reference Thorne, Sauro and Smith2015: 225), the language learning characteristics in the digital wilds imply that (1) learning happens in contexts, communities, or networks online, (2) learning is not the primary focus of said contexts, communities, or networks, (3) the learning originates in the learners, and (4) there is no direct mediation by curriculum, educational policy, teacher practice, or norms of evaluation common in educational contexts (Sauro & Zourou, Reference Sauro and Zourou2019). Within this context, this study focuses on an extreme yet sociolinguistically interesting case study of language learning: Traduccions Gaming.cat, an online Catalan-speaking community of gamers who fan translate video games from English into Catalan. Using digital ethnography and various analytical techniques, the study draws on the umbrella concepts of New Literacy Studies (NLS), participatory culture, and affinity spaces online to find out whether and how fan translation contributes to language learning.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1 New Literacy Studies, participatory culture, and affinity spaces online

We draw on the conceptual framework of NLS (Barton & Lee, Reference Barton and Lee2013; Gee, Reference Gee, Rowsell and Pahl2015) to study literacy and language use and development as a sociocultural process. NLS is concerned with forms of textual mediation and meaning making. As vernacular practices become more widely circulated due to digitization and amplified technological affordances, studying new literacies online implies exploring not only literacies and discourse as text – the characteristics of these novel ways of communicating and using language – but also their potential as spaces for reflection upon language, communication, and language learning through social participation, collaboration, and collective identity building in a voluntary, self-generated manner. The sociocultural dimension of learning in informal contexts – drawing on others as resources for learning – is at the center of interest-driven fan practices and spaces online (Ito et al., Reference Ito, Martin, Pfister, Rafalow, Salen and Wortman2019).

In affinity spaces, learning happens because of the establishment of a special type of community of practice around a shared interest. In other words, affinity spaces are the environments where fans socialize their appreciation towards something or someone they are passionate about (Duffett, Reference Duffett2013). Affinity spaces emerged over time in different formats, but with digitization, they have become more accessible and widespread (Gee, Reference Gee, Barton and Tusting2005). Through fan practices, fans appropriate, alter, and challenge traditional conceptions of cultural consumption and production. In this sense, fans exemplify the notion of prosumers (a portmanteau term combining producer and consumer) in the participatory culture (Jenkins, Mizujko & boyd, Reference Jenkins, Mizujko and boyd2015), which favors the distribution of multiple forms of user-generated content.

There is growing interest in applied linguistics, translation, and CALL to study fan practices. For instance, in efforts to organize this emerging subfield, Sauro (Reference Sauro, Dressman and Sadler2019) provides a typology of three categories of fan practices potentially conducive to language learning in the digital wilds: (1) fan practices that celebrate, (2) fan practices that comment, including unique practices like danmaku (on-screen embedded comments on Chinese social network Bilibili; Zhang & Cassany, Reference Zhang and Cassany2019), and (3) fan practices that transform or critique, with fan fiction or fan translation as helpful examples. Historically associated with the structuralist grammar-translation approach in language learning, translation has not always received good press in language education (Pintado Gutiérrez, Reference Pintado Gutiérrez2018), but it seems a naturally occurring communicative activity connected to the affinity of youth; for instance, consuming or producing fan-translated subtitles (Díaz Cintas, Reference Díaz Cintas2018).

2.2 Translation and language learning in affinity spaces

Traditionally, when and if present in language classrooms, translation has been a way to assess language learners’ performance (Laviosa, Reference Laviosa2014: 141). It has not been until recently that research has started to connect translation and multilingualism as two of the main components of real-world communication (Meylaerts, Reference Meylaerts, Gambier and van Doorslaer2011; Muñoz-Basols, Reference Muñoz-Basols2019), emphasizing its mediating value not only between linguistic codes (interlinguistically), variants (intralinguistically), and/or modes (intersemiotically) but also between cultures. The thought of translation as intercultural mediation serves to the purposes of educational trends that position language learners as socially active language brokers:

The user/learner acts as a social agent who creates bridges and helps to construct or convey meaning, sometimes within the same language, sometimes from one language to another (cross-linguistic mediation) … creating the space and conditions for communicating and/or learning, collaborating to construct new meaning, encouraging others to construct or understand new meaning, and passing on new information in an appropriate form. (Council of Europe, 2018: 103).

At the same pace translation is gaining prominence in language education with efforts to organize the ontology of this interdisciplinary field (see Pintado Gutiérrez, Reference Pintado Gutiérrez2018, for a distinction among pedagogical translation, code-switching, and internal translation), translation scholars express interest in exploring the non-professional realities of translation practice. In a literature review, Díaz Cintas (Reference Díaz Cintas2018) highlights the idea that digital media act as a catalyst, which promotes fast and widely circulated popular culture manifestations and social engagement through translation. The author explains the sociocultural drive behind non-professional subtitling communities and types of subtitles. For instance, he mentions guerrilla subtitles – whereby subaltern groups of self-organized subtitlers contest hegemonic cultural practices through subtitling – or the more popular fansubs – fan-made subtitles often produced by organized fan communities (O’Hagan, Reference O’Hagan, Remael, Orero and Carroll2012) who wish to distribute media content or express affection towards popular culture or characters. Both guerrilla subtitles and fansubs can be either genuine (aiming at functional equivalence linguistically, textually, and interculturally) or fake (a humorous, often sarcastic, recreation of the original).

In parallel, there is also the localization of video games, involving the translation of written scripts on the screen, written documents, such as video game instructions, dubbing of soundtracks, and possibly the cultural adaptation of image, color, sound, and other culturally embedded references in the game, both textually and paratextually (Muñoz Sánchez, Reference Muñoz Sánchez2009). Fan translation of games is often referred to as romhacking (O’Hagan, Reference O’Hagan, Remael, Orero and Carroll2012). This formulation emphasizes the “hacking” of games (traditionally retro games from previous decades), meaning the technical manipulation of games to substitute the text in the original language with text in the target language. Studies in this line of research account for the process of translation with a focus on the IT requirements, processes, and skills necessary to hack games or roms (the files containing the games). However, while fan translators of games may also form groups, little is known about how fan-made translation is socioculturally constructed in those groups.

Prior work in applied linguistics shows that second language (L2) socialization in affinity spaces online positively impacts language learning by being exposed to new texts and specialized knowledge (Thorne, Reference Thorne, Kessler, Oskoz and Elola2012), reinforcing learner identities or developing new ones as fans progress online and receive support from fan communities (Thorne et al., Reference Thorne, Sauro and Smith2015; Vazquez-Calvo, García-Roca & López-Báez, Reference Vazquez-Calvo, García-Roca and López-Báez2020). For instance, Shafirova, Cassany and Bach (Reference Shafirova, Cassany and Bach2020) show how bronies – adult male fans of the animated series My Little Pony – gain confidence in interaction and developing larger formulations over time in English as L2 by participating in online forums, discussing related fan art, or portraying alternative masculinities. Another fan who developed her language skills in fan communities is Nanako (Black, Reference Black2007). As a Mandarin Chinese migrant in Canada, Nanako began to write fan fiction on anime series in English. The corrective feedback and celebratory comments she received positively impacted her writing, her willingness to communicate in English, and her overall identity as an L2 speaker.

However, little is known about how gamers and other fans learn and experience language learning by participating in communities where fan translation is central to or part of their objectives. Prior studies explored fan translation as a socioculturally embedded process of language learning negotiation in gaming communities covering major language pairs (English-Spanish) (Vazquez-Calvo, Reference Vazquez-Calvo2018). As Sauro and Zourou (Reference Sauro and Zourou2019) highlight, there is a scarcity of studies in the digital wilds that center their attention on minoritized languages. The current qualitative-interpretative case study deals with a fan translation group that translates from English into Catalan, a minoritized language. It aims to answer three research questions:

RQ1. How and why do Catalan gamers organize themselves to translate video games?

RQ2. What type of fan translation is conducted in Traduccions Gaming.cat, and how is it conducted?

RQ3. To what extent do gamers in Traduccions Gaming.cat learn language through fan translation, and how is language learning happening in this online context?

3. Methodology

This qualitative-interpretative case study adopts a virtual ethnography approach (Hine, Reference Hine2015) and follows online data collection procedures common in computer-mediated discourse analysis (Androutsopoulos, Reference Androutsopoulos, Mallinson, Childs and Van Herk2013). It involved observation of a community of Catalan-speaking gamers who in April 2018 decided to create a Telegram group to produce translations of games in Catalan.

Gaming.cat – an online Catalan-speaking gaming community – was first accessed in April 2018, where the researchers posted a call for participation in a study on gaming communities and language learning. Five gamers showed interest in participating. After an initial screening conversation, one stood out as more interesting to the study: Link (pseudonym), a 28-year-old gamer from Catalonia.

From the call for participation, the researchers were explicit about the scope of the study (language learning, fan literacy practices) for the sake of transparency and to secure participation. However, participants had already established their own linguistic practice and ideology through tradition, routine, schooling, social background, or previous fan translation experience, which lowers the possibility of any participant observation bias.

3.1 Link and the team Traduccions Gaming.cat

Link reported that he had started talking with other gamers to create a team of fan translators. This initiative matched the intended scope of the study, and falls within an “extreme and snowball sampling approach” in naturalistic and ethnographic research (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, Reference Cohen, Manion and Morrison2007: 176). It is extreme, because Link and the team represent an unusual case in the Gaming.cat community for their role as fan translators. It is snowball, because Link was the access point to a subgroup from Gaming.cat who were (or wished to become) fan translators upon Link’s initiative. The team of fan translators was created in April 2018, consisted of six members initially, and in November 2018, numbers reached up to 10 members: nine male, one female. The researchers had closer contact with Link, who was the guide in the “online field” and willing to be interviewed in depth.

3.1.1 Online interviewing

A semi-structed interview with Link was conducted through the Telegram chat (Apr–May 2018). The interview focused on linguistic background, gaming profile, technological and literacy habits, engagement within the community of Catalan-speaking translators, and perceptions regarding fan translation of games. Afterwards, Link was accessible to clarify doubts on the evolution of the team, internal debates, or the translation practices during the online observation.

3.1.2 Online observation

Two types of screenshots were collected: (1) screenshots taken by the researchers and (2) screenshots provided by Link/shared by the team. An annotated diary log with screenshots was kept. The online observation lasted seven months (Apr–Oct 2018). Screenshots included translation segments, doubts, and updates on translation projects. The complete multi-party chat on Telegram was also stored. Table 1 provides an overview of the corpus of data.

Table 1. Corpus of data

3.1.3 Data analysis

First, an inductive analysis and coding of data were conducted (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2015). Following the tenets of NLS and the characteristics of affinity spaces, the analysis of the whole corpus of data resulted in 23 supra-codes and 202 micro-codes or categories related to 219 quotations, and the corresponding classification of the set of 50 screenshots in the corpus according to the supra-codes. Supplementary material illustrates the segmentation and integration processes of the data analysis.

Second, to tackle RQ3, the researchers proposed an adaptation of Benson’s (Reference Benson2015) framework of analysis of YouTube comments. Benson’s proposal was used to analyze YouTube comments and provide evidence of language learning online by commenting on videos. In our analysis, Benson’s framework was adapted to the analysis of Catalan oralized written discourse (Yus, Reference Yus2010).

The oralized written discourse originated around 10 translation tests received from potential new members to the group. Each of these tests incited multi-party written discussion on Telegram during the observation (see section 4.3.3). Each discussion contained exchanges in relation to explicit metalinguistic discussion on the quality of the translation test (the language used/interlinguistic/intercultural transfer in the target text) or miscomprehension of the source text. It is thus reasonable to assume that interaction involving information exchange on the linguistic characteristics of a fan translation may also involve language learning. This assumption is found in Pintado Gutiérrez (Reference Pintado Gutiérrez2018), when she discusses “internal translation” as the onomasiological process of transferring the first language (L1) into L2 or vice versa when learning a language. Each transaction/translation test was also categorized as “accepted” (non-/verbal acceptance by most or some gamers, such as “cap a dins” [lit. “inward”; fig. “get him/her in”]), “not accepted” (rejection), or “undecided” (no explicit decision made by the gamers involved in the online conversation).

At discourse level, our version of Benson’s (Reference Benson2015) framework kept Benson’s proposal of moves (Initiation, Response), adapted his proposal of English informational acts to Catalan (see Supplementary material), and did not include stance markers. Three reasons justified the exclusion of stance markers. First, stance markers, such as those in relation to cognitive activity (cognitive verbs), frequently overlap with informational acts. Second, Benson’s proposal is based on stance markers in English, which greatly differs from Catalan (more prone to ellipsis or prepositional phrases to modulate opinion: per (a) mi [to me] as an equivalent of “I think”), which would merit a separate study. Third, Benson himself acknowledges that “stronger evidence of an orientation to learning arises from coding of interactional acts” (2015: 94).

As part of the internal validity of the data, Link was presented with the latest version of this manuscript on 8 February 2020, before submission. He did not ask for any modification of the data presented here.

4. Findings

4.1 Origin and self-organization of Traduccions Gaming.cat

Traduccions Gaming.cat was created with six foundational members and a specific Telegram conversation group. The initial conversations in the Telegram group were contextual and helped understand the sociocultural organization of the team and fan translation as a distributed and collaborative practice. Team members established roles with their corresponding functions. For instance, Link was the coordinator; he oversaw translation projects and other members expected him to structure projects as he had done fan translation before (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gamer persuading Link to adopt the role of coordinator

Other roles include senior translators (prior experience in fan translation), junior translators (new to the group and fan translation, need to pass a translation test, see section 4.3.3), and promoters (do not translate, do networking, publicize achievements online). The hierarchical conception of roles resembles that of professional settings and is relevant because it affects the way in which language learning happens. For instance, senior members would validate junior members’ linguistic renderings through spell and grammar checking, constructing specialized glossaries for terminological coherence, or taking more difficult segments to translate (see section 4.3.1), whereas junior members frequently shared doubts in the group for peer validation (see section 4.3.2).

4.2 Scope, nature, and type of fan translation in Traduccions Gaming.cat

Team members initially harbored doubts about whether they should produce romhacked translations (non-official, without permission) or official translations (known as crowd translation and outsourced by distributors or developers). Romhacking is an option for minoritized languages and fan communities, because translating into lesser-spoken languages might not be economically viable (Dwyer, Reference Dwyer and Pérez-González2018). Link and other team members had romhacked before. But, on this occasion, they convinced the team against romhacking to produce only “official” crowd translations of popular games, manifesting sociolinguistic and group identity reasons for this decision (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Link arguing against romhacking

The team intended to gain reputation not only for them but also for the Catalan language, so that companies will eventually normalize Catalan as a language choice in their games. Doing only crowd translation limits their translation assignment catalogue to two games: This War of Mine (TWOM) (57% completed) and Playerunknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG) (50% completed). Over time, developers of these games accepted fan-made translations produced on easy-to-use platforms online, such as Babel.

Arguably, producing “official,” fan-made translations had effects on the translation process, the associated language learning, as well as the criteria to accept new members. Implications were found in three stages of the translation process: (1) language learning while translating, (2) language learning through sharing translation doubts in the group, and (3) language learning through commenting on applicants’ translation tests.

4.3 Language learning through fan translation practices online

4.3.1 Language learning while translating

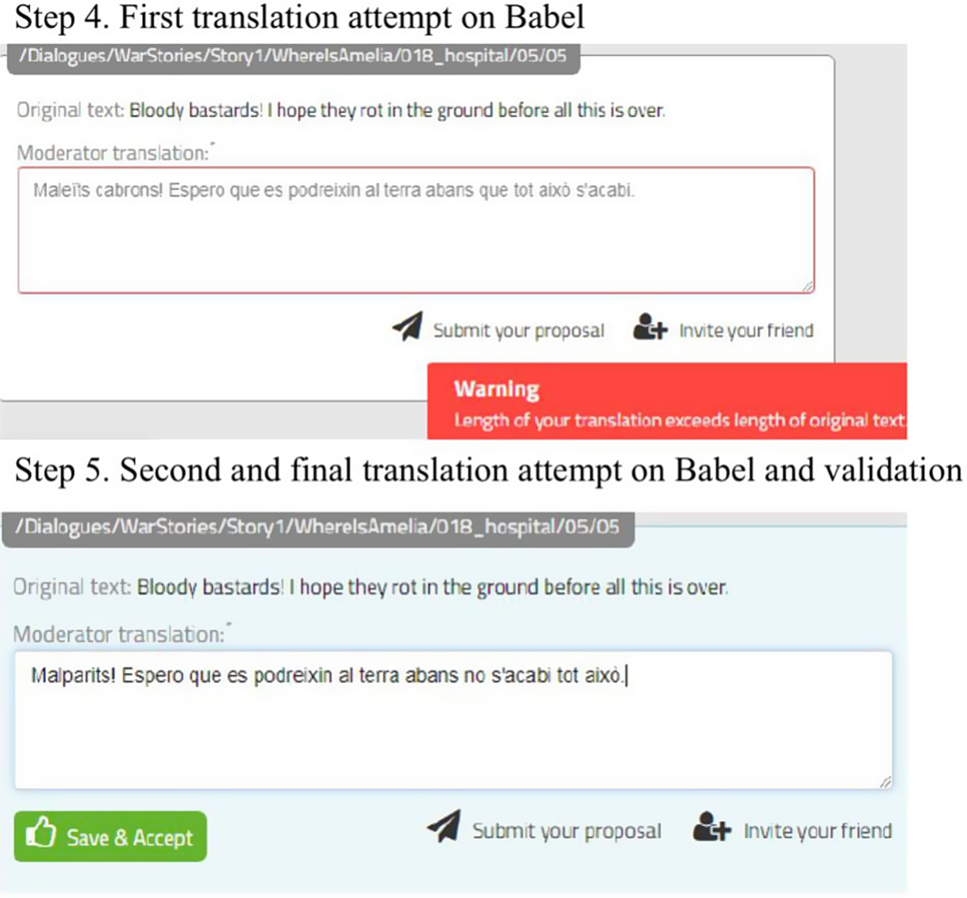

Because translation involves a dialogic process between comprehension of the source text/context (English) and production in the target language/context (Catalan), it might promote linguistic creativity, intercultural learning, and language learning and metalinguistic discussion (Pintado Gutiérrez, Reference Pintado Gutiérrez2018). Two translation events provided by Link (Figures 3 and 4) and Link with another gamer in the group (Figure 5) document the dialogic nature of translation and its potential for language learning in a technologically mediated context: the number of characters for each script translated on crowd translation software for games is limited; if exceeded, the script would be off screen. This adds a technical difficulty to the already cognitively and linguistically demanding process of translation by rephrasing and reformulating between the more synthetical English and the lengthier Catalan.

(a) First translation event. Figures 3 and 4 display a compilation of five screenshots sent by Link when asked if he could provide the translation process of a typical sentence when translating.

Figure 3. Link identifying a comprehension problem and searching and verifying meaning with Google Translate

Figure 4. Link’s attempts to translate and rephrase to fit the screen

Figure 5. Creative adaptation of an English riddle and wordplay made by Link and a gamer from the group

Figure 3 registers the first three steps in the translation process. Link identified a problematic sentence: Bloody bastards! I hope they rot in the ground before all this is over. He was not familiar with the verb “to rot” and decided to consult Google Translate, as per usual. Although in a first attempt Link configured Google Translate to translate into Catalan, his intuition made him believe that s’aturin [verb aturar-se, “to stop”] was not the right translation for “to rot.” He then verified the translation using Spanish as an intermediate language, obtaining se pudran [verb pudrirse, “to rot”], which is the right equivalent in context. This two-phased verification with Google Translate shows some degree of criticality on the part of Link to search for meaning and use language technologies while activating his plurilingual repertoire, common to all fan translators in the group (Catalan, Spanish, English, and an understanding of Aranese [Occitan language]). When fan translators consider that they fully understand a problematic sentence, they then start producing a tentative translation in Catalan.

Figure 4 exemplifies how the character limit on crowd translation software can be linguistically challenging. Link’s first translation attempt gave out a warning that the translation length exceeded the length of the original text. Both the first and the second translation attempts are correct translations meaning wise, but Link skillfully managed to vary the linguistic form and expression in Catalan so that the second translation would fit the screen of the game, through two strategies (see Baker, Reference Baker2011: 23–47, for a classification of translation strategies at word/phrase level):

-

1. Omission and compensation: “Bloody bastards” [Maleïts cabrons] becomes “Bastards” [Malparits]. Link omitted “bloody,” which lowers the illocutionary force of the phrase. However, using only “cabrons” might be perceived as too offensive, so Link decided to balance out the illocutionary force of the English and the Catalan using malparits, which is an equivalent of “bastards.”

-

2. Grammatical choice and modulation: The subordinate clause “before all this is over” is also subject to modification in Link’s second translation attempt. The Catalan formulation abans que tot això s’acabi [“before all this ends”] represents more literally the English meaning, and mirrors the word count and grammatical and syntactical choices. Because of the character limit, Link decided to reduce the expression by using another formulation (less frequent but idiomatic in Romance languages): “abans no s’acabi tot això” [lit.*before (not) ends all this]. Note the verb-subject inversion and the use of the negative particle “no,” with no negative meaning but only as an introductory/reinforcing particle of the subordinate clause (similar uses found in French with the ne explétif or Spanish), with a syntactical function similar to que or “that.”

Link’s word-level proficiency to translate English screen-fitting sentences and carry the meaning and intention of the English text into Catalan supports the idea that fan translation helps develop language at the levels of English comprehension and vocabulary acquisition (at least, familiarity with new words and phrases), and an aware and contrastive mastery of micro-linguistic features between English-(Spanish)-Catalan, with the support of a critical use of language technologies such as Google Translate.

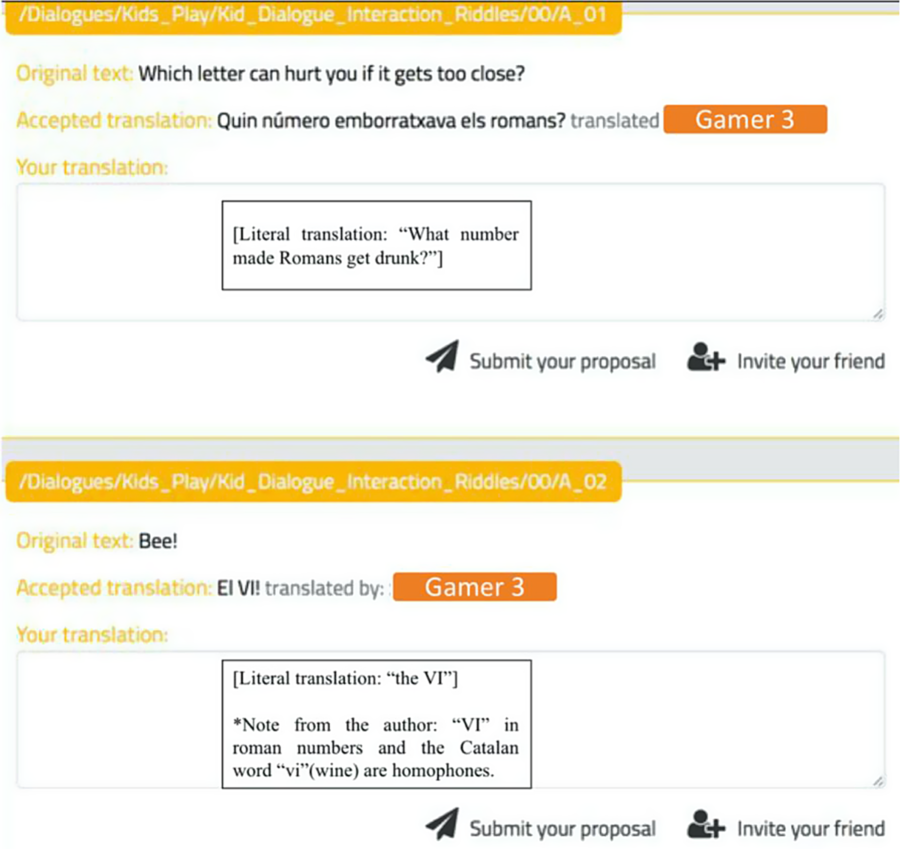

(b) Second translation event. The second translation event is at an above-word level. The screenshot in Figure 5 was shared with Link to prompt a retrospective justification of the translation process of the riddle and wordplay in English: “Which letter can hurt you if it gets too close? Bee.” The jocosity of the riddle lies in the homophonic nature of the letter “b” and the insect bee (both/bē/).

Common translation strategies for riddles include (1) producing a close version of the meaning of the wordplay but losing the humorous effect in the target language (maybe signaling there was a riddle in the original text), or (2) linguistically – and culturally – adapting the wordplay so that it exerts an equivalent pragmatic effect in the potential audience of the target text. Link and the additional gamer who translated the wordplay chose to adapt it with an equivalent wordplay in Catalan. The solution in Catalan partially keeps the homophonic play of the riddle: it uses the homographic VI (ordinal 6 in Latin numbering) and vi (“wine” /bi/), and introduces Latin numbering as well as the idea of wine – cultural traits closer to Catalan and Mediterranean cultures. In Figure 6, Link retrospectively explained the difficulty of translating humor and wordplays, so that he would seek help from colleagues to inspire a creative, pragmatic solution.

Figure 6. Link’s retrospective explanation on the dialogic process to translate creatively

This second example further supports the argument that fan translation produces language learning. In this case, a right interpretation of a wordplay and a creative, purposeful, and culturally adequate adaptation shows an incipient awareness of fan translators about source text and target text reception in their respective audience contexts. In other words, fan translators can identify communicative contexts and linguistically adapt wordplays, riddles, and other humorous phrases that would otherwise be difficult to parse. This capacity resonates with the notion of intercultural and interlinguistic mediation as part of the communicative competence (Council of Europe, 2018).

4.3.2 Language learning through sharing translation doubts in the group

Another way language learning was manifested was by sharing doubts. Junior members of the team shared linguistic doubts on Telegram in hopes of an agreed solution, particularly with the translation of PUBG, which they found challenging to translate.

Doubts included the semantic fields of (1) movement and physical states (standing, [to go] prone, to crouch), (2) domain-specific terminology from health care or the military showing the lexical complexity in games, (3) game terminology (nickname, match, specialized acronyms, game slang, in-game codes), and (4) polysemic phrases/strings with little contexts on the online translation platform.

Over the course of the observation, 23 linguistic doubts were shared. Here is a detailed analysis on four doubts to highlight the lexical complexity in games, the diversity and range of language to which fan translators are exposed, and how sharing doubts contributed to language learning through fan translation.

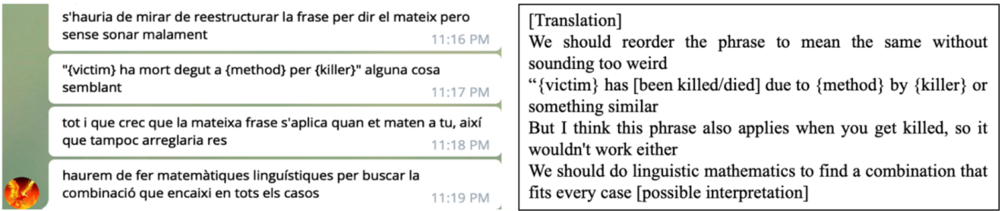

Doubt 1. The apparently easy string to translate “{killer} killed {victim} with {method}” (Figure 7) caused the group to verbalize that they would need to do “linguistic mathematics.” The inflection of verbs in Catalan would render a direct translation of the sentence ungrammatical if the gamers were to use the verb matar algú (“to kill someone”) – there are two possible subjects within the game: a second person (has matat) and a third person (ha matat). They must consider the two possibilities, since the string appears repeatedly with changes in relation to what comes in brackets: the killer, the victim, and the method.

Figure 7. Gamer explaining the difficulty of translating fixed in-game strings given the different linguistic features of English/Catalan

Doubt 2. According to Dictionary.com , “winner winner chicken dinner” is an exclamatory slang phrase used to celebrate a victory, especially in gambling. It is also known as the pop-out text after winning a round of PUBG. Therefore, it has also become an identifiable trait of the game and its English-speaking fandom. Its translation is another example of the linguistically problematic tension between humor and cultural adaptation and localization. Once the doubt was shared, one gamer proposed the following solution: Blat al sac i ben lligat (lit. “Wheat in the bag and tied tightly”). This saying in Catalan is well known across all Catalan-speaking territories (Pàmies i Riudor, Reference Pàmies i Riudor2007), maintains the food reference, and is close meaning wise. In Catalan, blat al sac i ben lligat may be used to celebrate an achievement (wheat in the bag) and warn against being overly optimistic before success is guaranteed (once the bag is securely tied).

Doubts 3 and 4. Specialized terminology is also a source of doubt and learning for fan translators. Depending on genre and topic, each game often provides simulated contexts of situated language use. PUBG is a multiplayer battle royale game, a survival death match where the last player/team alive wins. Terminology is thus warfare related; including weapons or health-care equipment. At times, neighboring concepts and terms pose a problem, as fan translators lack specialized, terminological knowledge. This was the case of “med kit” and “first aid kit.” At first, gamers in the group expressed concerns about the actual differentiation of the two terms:

“No m’acaba de convèncer perquè no veig que hi haja un contrast clar, però tampoc veig el contrast clar en l’original ![]() ” [I am not convinced because I can’t see there is a clear difference, but of course I don’t see the difference in the original (English) either

” [I am not convinced because I can’t see there is a clear difference, but of course I don’t see the difference in the original (English) either ![]() ] (Gamer, Telegram Group, quotation 218)

] (Gamer, Telegram Group, quotation 218)

However, they did know the game, so they could leverage the relevance of how exact a translation must be to affect the overall quality of the translation and a potential impact on the gameplay: “Els med kit són TAAAAN estranys de trobar …” [Med kits are SOOOOO rare to find (in the game) …] (Gamer, Telegram Group, quotation 219). Compensating for a lack of terminological accuracy with gaming expertise leads to pragmatic solutions when dealing with such terms. “Med kit” was translated as farmaciola completa (“complete first aid kit”) and “first aid kit” as farmaciola (“first aid kit”). Although in Catalan the term “equipament mèdic” exists, it relates more to the hypernym of “med kit.”

These doubts show the type of variety of phrases and vocabulary fan translators are faced with, including varying degrees of formality (slang, general, specialized) and mixed domains (military, health care, and virtually any depending on game genre). They illustrate the dialogic how gamers collaboratively solve comprehension problems and hold contrastive discussions on semantic fields and concepts with the objective of maintaining the English meaning and overseeing that Catalan structures and lexical forms are used. As the bulk of doubts and solutions increased, they decided to keep a glossary in the cloud for the sake of terminological coherence of all members’ input to the collective translation (Figure 8). At the time of writing, the glossary featured 39 terms with English-Catalan equivalents with some comments for clarification.

Figure 8. Glossary kept by Traduccions Gaming.cat for terminological coherence

4.3.3 Language learning through commenting on applicants’ translation tests

To be a member of Traduccions Gaming.cat, the founding members agreed that there should be a threshold test to check applicants’ ability to comprehend English, anticipate the communicative context (because strings to translate games in crowd translation software often lack the full context of a given utterance), and translate into Catalan. To investigate whether there is language learning through translation in fan communities online, all exchanges prompted by the 10 tests received from potential applicants and shared in the group during the observation were coded (see section 3.1.3). A total of 171 exchanges were coded (an average of 17 comments per test; max. 28, min. 4). An explanation of all the codes used is available in Supplementary material. Table 2 lists the most frequent primary and secondary acts in the exchanges.

Table 2. Frequency of primary and secondary acts in exchanges about translation tests

Inform is the most frequent informational act (35%), followed by Opine (30%). These two were often complemented by some secondary act such as React (35%) (mostly onomatopoeic expressions, expressive punctuation, or emoticons that help modulate assertive talk on others’ language performance), Quote (test) (17%), which specifically quotes words from applicants’ tests or the original text, Expand (11%), or Qualify (10%), which give more information or verbalize some qualification to the primary act, as well as Preface to introduce the primary act or Alert to call other members’ attention to pronounce themselves on the evaluation of tests.

Out of the 10 applicants/tests, six were accepted into the group, two were not accepted and two were discussed but pending a decision. Tests that were not accepted or those that left the team undecided elicited the most comments and primary informational acts. Test 3 (not accepted) with 60 primary acts and test 5 (not accepted) with 52 primary acts were the ones most discussed. Let us see some exchanges from test 5 when gamers were already reacting to it (R). For instance, in Table 3, the gamer MCH in exchange 2 commented on the calque of “résumé” translated as resum (“summary”) and suggested a plausible translation. The error was then taken up by Gea, who thought making such a comprehension mistake is not acceptable or massa heavy (“too heavy”).

Table 3. Exchanges about an inaccurate translation of “résumé”

Also, concerning test 5, in Table 4 Link and Gea signal the applicant’s possible miscomprehension of the expression and tense of “that won’t work.” The original text shows that the protagonist is being sarcastically pessimistic about not having the chance of being hired by a real estate company, alleging a pretended sheer love of houses. The protagonist ironically confesses that such an argument will not do the trick (“that won’t work”). The author of test 5, however, does not exactly convey the meaning of “that won’t work” in this context because of the tense in Catalan (conditional) – the protagonist’s self-confession is more of an assumption than a hypothesis. The expression No funcionaria is also less idiomatic in Catalan, and the choice of funcionar is more formal than the English version.

Table 4. Exchanges about an inaccurate translation of “that won’t work”

In test 10, the same “That won’t work” expression is a source of peer eulogy, because of the efforts from applicant 10 to provide an idiomatic Catalan expression that respects both the original meaning and tenor. Table 5 shows the first exchanges prompted by this test.

Table 5. Exchanges about a creative translation of “that won’t work”

In test 10, the applicant chose to translate “That won’t work” as Aquesta no cola, which is pragmatically equivalent in meaning and very proximate in terms of informality. Aquesta no cola is close to “They are not going to swallow that (one)” or “They won’t buy it.” Tests offer some opportunity for gamers to expose themselves to multiple translated versions of the same English expression. Translation tests are “activated contexts” where gamers expose themselves to new vocabulary and expressions, in passing a verdict of the acceptability of a translation, they detect novel language, attend to it, and infer meaning from context or with the assistance of other resources and strategies (including collective metalinguistic reflection), a process that resembles the explicit vocabulary learning hypothesis (Ellis, Reference Ellis and Ellis1994: 219). As the group progresses, undertakes new translation assignments, or receives additional tests from applicants, it is expected that there will be an increase in the number of occurrences and level of exposure to common in-game language, linguistic features, and general and specialized language in English that needs translating into Catalan, coupled with reflection and collective discussion.

This micro-level analysis shows that the interaction is relatively complex with several stance takers who take the floor to provide metalinguistic comments on others’ translation abilities, which is a common trait repeated across the data set. In our opinion, this is indicative of learning and active engagement on the part of the group’s members, in a similar fashion to how YouTube users comment on videos (Benson, Reference Benson2015). The number of exchanges and informational acts increased in parallel to the number of linguistic and translation problems shown in translated tests, either because applicants did not adhere to the group’s perceived symbols of norm and language ideals, or because applicants miscomprehended the English text so that, in the group’s eyes, they are not suited to the challenging task of fan translating games in the form the group requires.

The findings show that fan translators strive to offer a normative version of Catalan, arguably triggering monoglot attitudes, as seen in studies on Catalan use and projection in other media (Frekko, Reference Frekko2011), and applying such norm functions as an initiation rite to new members (section 4.3.3). However, in the internal conversations, the intralinguistic, interlinguistic, and intersemiotic variation is prolific. The language exchanged in Table 5 displays a translanguaged, colloquial version of Catalan, with some English mixing (LOL, “final boss”) and a wealth of emoticons in both image (![]()

![]() ) and typed format (x’D, xP, ^^), as well as other oralized traits (expressive punctuation). It is worth mentioning the distinction between the group’s actual talk and the desired language in fan translations, because it denotes gamers’ socio-pragmatic competence to move across linguistic varieties and reminds of the sociolinguistic conflict in Catalonia where language users remain active in language defense and promotion. The perceived threat of language distortion or the accentuation of the minoritized situation of Catalan, which might lead to some examples of linguicism and language purism, is a theme worth exploring further with the same data set.

) and typed format (x’D, xP, ^^), as well as other oralized traits (expressive punctuation). It is worth mentioning the distinction between the group’s actual talk and the desired language in fan translations, because it denotes gamers’ socio-pragmatic competence to move across linguistic varieties and reminds of the sociolinguistic conflict in Catalonia where language users remain active in language defense and promotion. The perceived threat of language distortion or the accentuation of the minoritized situation of Catalan, which might lead to some examples of linguicism and language purism, is a theme worth exploring further with the same data set.

5. Discussion

Digitization has created opportunities for linguistic and intercultural encounters, exchanges, and learning. This study has attempted to detail fan translation as an interest-driven linguistic practice with evidence of not only online community formation of Catalan-speaking Traduccions Gaming.cat, but also micro-analyses of members’ language learning.

Fan translation is a premium literacy practice that flourishes in outside-school contexts (Knobel & Lankshear, Reference Knobel and Lankshear2014) thanks to fan translators – young pro-ams (professional amateurs) who create “all sorts of media, citizen science, and knowledge … via collaborative problem-solving communities on the Internet” (Gee, Reference Gee2013: 60). Out of pro-Catalan sociolinguistic activism and a passionate affinity to gaming, Catalan gamer-translators develop quasi-professional, sophisticated networks of chain fan translation production, with set roles and functions (RQ1). This pro-Catalan defense makes them reject paralegal fan translation activities, favor exclusively the fan production of “official” translations, curate their online identity as a group, and set lofty standards of language quality and stringent entry criteria for potential new members (RQ2). Hence, translators from Traduccions Gaming.cat can be seen as guerrilla fan translators of games, in parallel to what Díaz Cintas (Reference Díaz Cintas2018) labels “guerrilla fansubs.” Their political activism not only shows in their preference for “official” translations (fan-made or otherwise), but also in their linguistic projection and manifestations to the world.

While observing the accurate transfer of the English meaning, their translations encourage language learning (RQ3) through the use of very idiomatic, highly creative Catalan phrases and expressions (Figures 3, 4, 5, and 6), oftentimes emerging because of a limitation in the number of allowed characters, but also because of a will to advocate Catalan language normalization. Fan translation is often met with doubts that are solved through consulting language technologies (Figure 3) or senior members on Telegram (section 4.3.2, Figure 7), with the corresponding abilities to either effectively operate Google Translate with intermediate languages like Spanish or negotiate meaning online with other fan translators prompted by members’ linguistic doubts (section 4.3.2, Doubts 1, 2, 3, and 4) or evaluating applicants’ tests (Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5). Linguistic solutions are often standardized through keeping glossaries and other internal documents (Figure 8).

It is through their rigorous standards on the language they want to see in translations that fan translators provide more evidence of incidental language learning. Each translation test undergoes the scrutiny by all existing members, who dissect the translation informing, opining, evaluating, and reacting to the author’s miscomprehension of English or poorly expressed Catalan to eventually pass an acceptance/rejection verdict. Evidence of language learning include English phraseology, specialized terminology from various fields, in-game terms and phrases, general language, and slang, as well as specific grammatical and syntactical features of Catalan (no expletiu). Paradoxically, fan translators’ talk online is mostly informal with translanguaged segments (including Spanish or English), and a profusion of emoticons and other multimodal semiotic resources – an indication of an interesting intralinguistic variation, awareness, and ability. Fan translating, sharing language doubts in the group, or commenting on applicants’ translation tests activate “subgoals” (consulting language technologies, comprehending texts, metalinguistic discussions, negotiation of meaning) in which “language … becomes the intentional object … in the service of a higher goal” (Lantolf, Thorne & Poehner, Reference Lantolf, Thorne, Poehner, VanPatten and Williams2015: 218), such as English-Catalan fan translation motivating incidental language learning.

Exploratory and descriptive, this study has offered insight into an extreme case of language learning in the digital wilds. Its results are not generalizable but might be used as a source of inspiration for future studies or classroom interventions seeking to incorporate mediation in a manner students can relate to their affinities and communicative practices. Prior studies in TESOL have attempted to stimulate the teaching of various linguistic domains and skills by fan fiction and the characteristics of affinity spaces (Halaczkiewicz, Reference Halaczkiewicz2020) or by promoting fan fiction subgenres and practices for language development (Sauro & Sundmark, Reference Sauro and Sundmark2019). Future studies may adopt an interlinguistic lens to incorporate fan-inspired translation activities if, as with fan translators, language students are seen as potential language brokers or mediators in non-professional settings (Council of Europe, 2018). This case study explored a community whose members learn language (L2-English, L1-Catalan) in an entirely Internet-mediated environment. Efforts were made to provide evidence of incidental language learning online, but we acknowledge the difficulty in such a task. The quantification from metalinguistic comments following Benson (Reference Benson2015) supports the more casuistic instances of language learning through fan translating. In concurrence with Benson, additional methodological approaches, combining quantitative and qualitative methods, may be needed to reinforce the argument that fan practices and translation produce language learning, namely in relation to vicarious spectators online, and not only the more active participants. Hopefully, the limitations in this study will also inspire methodological proposals.

Fan translation may be a practice on the edge of technology-enhanced language learning. However, the sociocultural account of how gamers learn language by fan translating may provide justification to keep pushing the boundaries of CALL to investigating informal contexts of online language learning (Sauro & Zourou, Reference Sauro and Zourou2019). In our opinion, fan translation might be conceived as a very special form of CALL in the digital wilds, as fan translators utilize technologies not only for communicating purposes but also to verify meaning with language resources, to produce translations on software with limitations as per screen characters – stimulating linguistic creativity – or to provoke online, multi-party, metalinguistic discussion and negotiation of meaning, with instances of collective incidental language learning. Besides an inspiration for future studies, intersecting the study of fan practices and language learning may be an innovative pool of exciting research in CALL in the digital wilds as technology-mediated intercultural and interlinguistic exchanges keep proliferating.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S095834402000021X

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported by ForVid: Video as a language learning format in and outside the classroom (RT2018-100790-B-100; 2019–2021), “Research Challenges” R+D+i Projects, Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, Spain.

Ethical statement

Efforts were made to preserve the anonymity, confidentiality, and fair treatment of sensible data of participants during this Internet-based ethnography (Markham & Buchanan, Reference Markham and Buchanan2012). Participants signed a consent form, and the author’s university approved the ethical standards of the project.

About the author

Boris Vazquez-Calvo is an assistant professor in EFL and language education at the Autonomous University of Madrid, Spain. His current research interests touch upon language learning, translation, digital culture, fan practices, identification, and technology-mediated discourse.

Author ORCIDs

Boris Vazquez-Calvo, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8574-7848.