Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 June 2005

This article explores the interconnection between grammar and the performance of preferred and dispreferred responses in Japanese. As is well known, dispreferred format turns are structurally more complex than preferred format turns, regularly delayed, accompanied by prefaces and accounts, mitigated, or made indirect. Owing to the flexibility of Japanese grammar, participants have expanded intra-turn capacity to maximize or minimize compliance with such formats. On one extreme, a dispreferred action can be massively delayed until near the turn-ending through opting for so-called canonical predicate-final word order and minimization of ellipsis. On the other extreme, a preferred action can be expedited to the very opening of a turn through non-canonical predicate-initial word order by taking advantage of word order variability and ellipsis. Such syntactic practices are interactionally managed for calibrating the timing of social action. It emerges that the canonical word order – assumed to be the generically unmarked alternative – is actually optimally tailored for the implementation of marked (dispreferred) responses, as opposed to a non-canonical word order for unmarked (preferred) responses, in the given sequential environment.

Textbooks on Japanese grammar prescribe that the so-called canonical word order in Japanese is Subject-Object-Verb (SOV), or more generally, that the verb or predicate occurs in final position (e.g. Kuno 1973, Shibatani 1990). We might ask, however, what is meant by “canonical”: Is it a matter of how frequently that order is employed, or does it refer to some kind of normative syntax? Such questions arise, for instance, from the fact that even a quick inspection of conversational data indicates that SOV order with an expressed subject is a somewhat rare occurrence. Furthermore, it has been widely noted that deviations from predicate-final word order and ellipsis of sentential constituents are common conversational practices (e.g. Ono & Suzuki 1992, Y. Fujii 1991). In contrast to languages such as English that have comparatively rigid word order, Japanese is notable for the freedom with which the major constituents may be ordered. Nevertheless, relatively little is known about the possible salience of word order in the performance of conversational activities.

Specifically, this article focuses on second parts of paired actions (adjacency pairs), and examines how canonical and non-canonical word orders and ellipsis may be employed for constructing dispreferred and preferred second actions in Japanese interaction. It will be argued that word order and ellipsis are not simply grammatical phenomena, but that they are flexibly implemented as interactional devices for either expediting or delaying the performance of an action within the course of a turn. Thus, in the particular sequential environment of responding to a first action, they turn out to be potent linguistic resources for augmenting the display of affiliation or disaffiliation.

Before proceeding, two caveats pertaining to terminology are in order. First, the expression “canonical word order” is used here to refer to idealized types of word order (epitomized by SOV order, but including others) which linguistic typologists consider to be representative of the Japanese language, originally derived by grammarians based on invented examples. Although utterances conforming to the so-called canonical word order can be found in naturally occurring talk, any assumption that such ordering is necessarily the most basic, standard, acceptable, common, or frequent is bracketed throughout this article.1

%1However, a number of small-scale studies indicate that the predicate-final word order is generally the most frequently observed type of ordering (e.g. Matsumoto 1995; Tanaka 1999a, chap. 3).

In addition to work in conversation analysis (CA) dealing with preference organization (e.g. Davidson 1984, 1990; Drew 1984; Heritage 1984a; Lerner 1996b; Levinson 1983; Pomerantz 1978, 1984a, 1984b; Sacks 1987; Schegloff et al. 1977), this article draws on studies in grammar and interaction, a relatively recent stream of CA which investigates the role of linguistic resources in the performance of interactional activities and the ways in which social activities are shaped by the tools available in different languages (e.g. Couper-Kuhlen & Selting 1996, Ochs et al. 1996, Selting & Couper-Kuhlen 2001). Within this stream, there is a growing body of research on turn construction, projection, and collaborative completions in Japanese conversation. Of particular relevance to this project is research on projectability (Fox et al. 1996; Hayashi 2003; Tanaka 1999a, 2000a, 2001b), adverbials for turn-projection (Tanaka 2001a), co-participant completion (e.g. Hayashi 2001, 2003; Hayashi & Mori 1998; Hayashi et al. 2002), compound turn-constructional units (Hayashi 2003; Lerner & Takagi 1999; Tanaka 1999a), the relation between connectives and agreements/disagreements (Mori 1994, 1999), and strategies for making, accepting, and rejecting invitations (Szatrowski 1993). This article builds on this literature by investigating how diverse linguistic devices such as post-positional particles, adverbials, connectives and compound turn-constructional units are deployed by participants for constructing turns with canonical and non-canonical word order in the contingent achievement of preferred and dispreferred activities.

The data used for this study consist of approximately 5 hours of ordinary conversation and 5 hours of institutional interaction including meetings and telephone conversations.2

I am extremely grateful to Makoto Hayashi, Mihoko Fukushima, Hiroko Fujita, Kana Suzuki, and Yuri Ono for sharing with me some of the Japanese transcripts used in this project.

As a preliminary to addressing the relation between word order and preference organization in Japanese talk-in-interaction, the next section begins to “unpack” the grammatical construct of the so-called canonical word order (e.g. predicate-final order) by examining how it may be linked to the conversation analytic notion of projectability. In particular, this type of word order and the minimization of ellipsis are shown potentially to maximize the projectability properties of a turn, whereas deviations from the canonical word order (i.e. non-canonical word order), together with ellipsis, reduce the degree to which a turn trajectory can be projected. The third section continues to lay the groundwork by reviewing the literature on preference organization of second actions (of adjacency pairs) and by showing how the projectability of an emergent turn can be employed to convert a dispreferred into a preferred action. Based on the observations made in these preparatory sections, the main body of the article argues that a turn-structure deviating from canonical word order (e.g. predicate-initial order), combined with ellipsis, is tailored for expediting the implementation of preferred actions, in contrast to canonical word order and minimization of ellipsis, which are typically reserved for turns directed toward the performance of dispreferred actions. It will further be shown that the projectability properties of turn-shapes conforming to canonical word order are routinely exploited by participants to foreshadow, delay, and minimize the delivery of a dispreferred response, thereby potentially creating an opportunity to convert the emergent dispreferred action into a preferred one.

As the first step toward exploring the role of word order as a resource for constructing preferred and dispreferred second actions, this section examines participant orientation to the two broad types of word order, canonical and non-canonical, and how their respective structures affect the extent to which participants can project their likely trajectories. Projectability is a key feature which can be built into the design of a turn for which there is an interactional motive of facilitating the foreshadowing of its eventual course. It will be shown that the canonical word order has structural aspects that maximize projectability, whereas the non-canonical type minimizes projectability. For reasons that will subsequently become clear, the projectability of canonical word order is an integral property exploited by participants for constructing dispreferred seconds.

To begin with, the structures of turns that approximate the canonical word order will be inspected, followed by a discussion of their projectability properties. To reiterate, grammarians usually characterize Japanese as a verb-final or predicate-final language (Shibatani 1990:259; Kuno 1973:4; Martin 1975:35). More specifically, Japanese is said to follow canonical SOV order for transitive sentences and SV order for intransitive sentences, even though the subject and object may be interchanged through a phenomenon referred to as “scrambling” (Shibatani 1990:259). The following fragments from conversational data exemplify turns that are in conformance with the canonical word order, with an intransitive verb or a transitive verb, and with the subject and object “scrambled”, respectively:

Japanese uses postpositional particles, such as the nominative subject marker ga and accusative object marker o, which can specify the part of speech of the preceding element(s). Thus, the nominative particle ga in fragments (1) and (2) above respectively marks Son'na hito ‘such a person’ and Nakamura as the subjects of the sentences.3

Even though ga is universally described as a nominative case particle, recent research by Ono et al. 2000 demonstrates the primacy of its role as a discourse-pragmatic marker over its function to indicate grammatical relations.

Evidence that participants orient to the predicate-final structure, among other forms, is provided through instances of collaborative completions where a second speaker goes on to offer a rendition of the predicate which could complete the first speaker's turn-beginning, as exemplified below for the word order (Subject – Predicate Adjective) where the subject is marked by the case particle ga. The participants are debating which of the movies Taxi I or Taxi II was better:

In line 1, Eri suggests that Taxi I was better than Taxi II through a qualification: ↑Ii kedo demo nee. (.) ‘Although ((Taxi II)) was good, but you know (.)’, followed by the construction of a subject phrase marked by the nominative ga in line 2:

. ‘One, more than ((II)) was, you know.’ But without waiting for Eri to continue, Yoko begins to speak by first producing a slightly variant repetition of the same subject phrase (line 3), and then proceeding to furnish the type of element (a predicate adjective) deemed appropriate to complete the turn underway (line 4). Importantly, just as Yoko goes on to articulate the predicate adjective (line 4), Eri re-enters simultaneously with another predicate adjective, omoshiroi ‘fun’, thereby, in effect, ratifying Yoko's choice of a predicate adjective as a grammatical item that could potentially complete the subject phrase. It is the emergent grammatical structure that opens a “slot” for others to anticipate the type of grammatical element that could complete a turn, which may be filled through the choice of an item fitted to the context.

The fragment above exemplifies that a turn beginning that happens to conform to the canonical ordering maximizes the projectability of the unfolding trajectory of a turn, not because it might be somehow “standard,” “basic,” or “common,” but because of the resources that it has to enable grammatical projectability. Interestingly, most instances of collaborative completions in Japanese reported elsewhere can be seen to exhibit some version of canonical word order (e.g., examples of collaborative completions cited in Hayashi 2003; Tanaka 1999a, 2001a). Participants display their orientation to that word order, among others, by anticipating the final constituent that would complete an ongoing turn, a phenomenon referred to as “terminal item completion” by Lerner 1996a. Hayashi 2003, moreover, makes the following observation with respect to mono-clausal sentential units:

Since Japanese typically displays predicate-final word order … terminal item completion often takes the form of producing a verb, a predicate adjective, or a predicate noun, that is fitted to the unfolding structure of another's sentential unit. (2003:86)

Further connections between the so-called canonical word order and projectability are examined next.

Shibatani (1990:257) describes Japanese as an “ideal” SOV language in which the “dependent-head” relationship is preserved with all types of constituents. As will be illustrated, this expanded notion of canonical word order would therefore prescribe the following: an adverb precedes the verb that it modifies, as in ex. (5) below; a topic precedes the predicate that it is linked to ex. (6); and a subordinate clause precedes the main clause (7). Although Shibatani bases such “rules” on invented examples, an inspection of naturally occurring utterances beginning with the above types of word order shows that they also allow for a high degree of projectability. Excerpt (5) instantiates the word order in which an adverb precedes the verb it modifies:

In the fragment above, the adverb cha::nto ‘aptly’ (line 2) contributes to projecting an upcoming predicate within the given local context, and it creates a grammatical slot for the subsequent production of the final verb (predicate), as demonstrated by the collaborative completion of the verb expression kaite ari masu yo ↑ne::: ‘are written ((there)) aren't ((they))?’ by a co-participant in line 4 (see Tanaka 2001a).

The next excerpt illustrates the capacity of a topic (a noun phrase marked by the topic particle wa) to project a possible predicate within the local unfolding context. A professional wedding planner is helping a prospective bride and groom prepare for their wedding reception. A few turns before the fragment presented below, the bride-to-be suggested that some people give things like dried bonito and confectionery as presents to the guests:

In line 1, the planner constructs a topic phrase, katsuobushi toka okashi toka wa: ‘As for things like dried bonito and confectionery’, marked postpositionally by the topic particle wa. Having heard the topic, the groom is able to anticipate a predicate that might complete the planner's emergent turn, partly owing to the unfolding context and the projectability properties of the topic particle (see Tanaka 1999a, chap. 5). In other words, the topic in line 1 permits the groom to furnish the anticipated predicate in the grammatical slot (line 2) that is created by the topic particle within the given interactional environment. In line 3, the planner ratifies the groom's candidate predicate.

The next fragment illustrates the canonical word order in which a subordinate clause precedes the main clause. The subordinate clause (preliminary component) is produced by one speaker, Masao, and the main clause (final component) is completed in overlap by both Masao and a co-participant, Naomi:

Masao first produces a subordinate clause in lines 1–3, consisting of the preliminary component of a compound TCU of the form ‘if X + then Y’, which is not only marked by the postpositional conjunctive particle nara ‘if-then’ in clause-final position (Lerner 1991, Lerner & Takagi 1999) but also begins with Moshi: ‘if’. In line 6, the second speaker, Naomi, enters with the expression Soo suru to ‘If ((one)) does that’, which rearticulates the preliminary component uttered by Masao in abbreviated form; she then goes on to produce – in overlap with the first speaker – the main clause tsuman'nai kara ne ‘((it)) would be a shame, you know’, which is a rendition of the second part of the compound TCU. Lerner observes: “During its production, a compound TCU shows that it has a multi-component structure consisting of a least a preliminary and a final component … Because of the in-progress recognizability of the ‘if X + then Y’ structure, both the possible completion of that preliminary component itself and the form of the final component (‘then Y’) can be roughly foreseen” (1996b: 307).

The collaborative completions illustrate that the various types of word ordering considered thus far represent normative structures which are oriented to by speakers of Japanese as potential building blocks of turns. It should be underscored that the myriad resources afforded by such types of word ordering maximize the projectability of the emergent turn trajectory by enlisting the capacity of various case, adverbial, and conjunctive particles and other elements incrementally to project the progress of talk, as witnessed by the possibility of co-completions that they trigger. In sum, a general feature of the canonical type of word order is that it possesses structural characteristics which permit a high degree of projectability.

The excerpts dealt with above all conform to the verb-final or predicate-final structure, both for monoclausal turns and those constructed as compound turn-constructional units. In actual conversation, however, various constituents such as subject, object, and adverb may occur in post-predicate position. Word orders that involve post-predicate additions will be referred to here as “non-canonical.” In practice, word order is resiliently implemented, with the various syntactic constituents appearing in almost any order, as exemplified by the two fragments below:

In the next fragment, Maya and Eri are talking about a French film they saw independently of each other on TV. Maya originally mentioned that it was a shame that the sound was dubbed. Immediately before the extract shown below, Eri retorted that the dubbing of one character's voice was very skillfully executed. To this, Maya admits in lines 1–4 that she had not seen the entire film properly from the beginning.

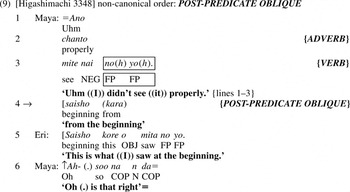

In example(8), Keiko begins with a predicate On'naji yo ‘((It))'s the same’ before going on to furnish a post-predicate subject phrase eri mo ‘the collar too’. Likewise in(9), Maya first produces a complete TCU Ano chanto mite nai no(h) yo(h) ‘Uhm ((I)) didn't see ((it)) properly’ in lines 1–3, which follows predicate-final word order, prior to attaching a post-predicate oblique saisho (kara) ‘from the beginning’ (line 4).

As previously discussed (Tanaka 1999a, chap. 4), these instances, together with those presented earlier, illustrate four significant features of post-predicate additions and, more generally, the structure of turns in Japanese:

See Tanaka (2004) for the role of prosody in marking turn-endings in Japanese.

A critical turn-constructional property of non-canonical word order which can be gathered from the observations above is that deviations from canonical word order (e.g. verb-initial structure) minimize the projectability of the emergent turn-structure. An early production of a predicate component is likely to minimize the occurrence of collaborative completions, since the predicate is typically treated as a possible completion. It should therefore come as no surprise that post-predicate additions are relatively difficult to project.

Many insightful explanations have been offered (e.g. Hinds 1982, Kuno 1973, Ono & Suzuki 1992, Simon 1989) concerning the purpose and motivation for employing post-predicate additions: as an “afterthought” (Shibatani 1990:259); for disambiguating an elliptical referent or for emphasis (Hinds 1982; see also Fujii 1991); “where the speaker asserts first a pragmatically marked part” (Fujii 1991:81); to “defocus” semantically subordinate material (Clancy 1982); and for “further specification, elaboration, clarification, repair” or for emotive purposes (Ono & Suzuki 1992). Moreover, Ono & Suzuki (1992:436) suggest that certain post-predicate forms such as Nani sore ‘What's that?’ produced within a single intonational contour are “in the process of becoming grammaticized.”

In spite of the high interest in this issue, however, there is little conversation analytic work that directly addresses how word order variability and the use/avoidance of ellipsis may be resources for accomplishing interactional tasks. This section has served as a point of departure by drawing attention to the relation between word order and projectability. It was shown that relatively “non-elliptical” turns with predicate-final structure and those conforming to dependent-head word order (i.e. the so-called canonical order) exhibit high projectability. This is so because the various elements preceding a predicate in a predicate-final turn – such as subject, object, adverb, or case particles – contribute to incrementally projecting a forthcoming predicate. Alternatively, owing to the predicate-final orientation in Japanese, a turn with predicate-initial structure renders the turn-trajectory opaque. These observations can be taken a step further toward elucidating the salience of word order for the organization of preference in Japanese. But first, reviewed below are some core features of preference organization and its relation to projectability, which will form a basis for the ensuing discussions.

Past research on preference organization has identified routine methods or designs through which members differentially perform actions (Atkinson & Drew 1979:122; Davidson 1984, 1990; Drew 1984; Heritage 1984a:265–69; Lerner 1996b; Pomerantz 1978, 1984a, 1984b; Sacks 1987; Schegloff et al. 1977). Importantly, preference does not refer to some psychological state of the speaker but to a set of institutionalized methods for producing and designing turns. In particular, when alternative second actions are available as responses to a first pair part of an adjacency pair, some are preferred and others dispreferred, as outlined in Table 1.

Preference format of some selected action types (partially adapted from Heritage 1984a:269.

The two types of seconds have non-equivalent status (Schegloff 1988:456), and can generally be differentiated on the basis of both morphology and timing. The following is a summary of Levinson's (1983:332–39) discussion of preferred and dispreferred format seconds. Preferred actions tend to be structurally simple, “have less material,” are direct, and are delivered without delay, sometimes in partial overlap with the first part. In contrast, dispreferred actions tend to be structurally more complex, are delayed, and exhibit many of the characteristics listed in Table 2.

Features of dispreferred format actions (adapted from Levinson 1983:334).

Heritage provides insights into why preferreds, such as acceptance of an invitation, are delivered straightforwardly whereas dispreferreds, such as a rejection of an offer, have built-in features of delay, avoidance, and accounts:

It will be obvious enough that the preferred format responses to requests, offers, invitations and assessments are uniformally affiliative actions which are supportive of social solidarity, while dispreferred format responses are largely destructive of social solidarity…. (T)he uniform recruitment of specific features of turn design to preferred and dispreferred action types is probably related to their affiliative and disaffiliative characters. (Heritage 1984a:268–69)

Whereas an affiliative or preferred action requires no account of why it is being accomplished, the performance of a dispreferred or disaffiliative action can potentially threaten the face of either the recipient or the first speaker, and even the relationship itself (Heritage 1984a:271–73; Lerner 1996b). In order to resolve such threats, dispreferred seconds may incorporate accounts by “focusing on ‘no fault’ considerations” or may be delayed in order to forestall their occurrence and “to minimize the likelihood of their occurrence” (Heritage 1984a:274–76). Indeed, the very occurrence of delay, hesitations, prefaces, token acceptances/agreements, and the like is interpreted by the first speaker as a prelude to a dispreferred action, and this may prompt the speaker to revise the first action or retract it altogether prior to full articulation of the projected dispreferred action (Davidson 1984, Lerner 1996b). Thus, it can be said that not only the delivery of preferred seconds through the preferred turn-shape but also that of dispreferred seconds through a dispreferred format show sensitivity to issues of social solidarity and avoidance of conflict.

Crucially, the projectability of an unfolding utterance can be used to convert a dispreferred action into a preferred action. Consider the following instance, discussed by Lerner 1996b:

In lines 1–3, Heather speaks on behalf of a co-present participant, Donna: Donna said that that's what she needs to know eventually. But in lines 5–6, Donna begins to refute Heather's statement, saying I don't need to know that, I just think thet, starting to give an alternative answer. In line 8, Heather enters by anticipating the probable trajectory of Donna's turn and completes it by saying students need to know that. To this, Donna agrees in line 9. Therefore, by preempting the continuation of Donna's disagreeing turn, Heather is able to achieve agreement at the end of this sequence. Specifically, it is partly Donna's adoption of the correction format ‘not X + Y’ and the “attribution-type preliminary component”, I just think thet, which recognizably permit Heather to project the possible upshot of Donna's turn. In this sense, the projectability of a dispreferred turn heightens the possibility of converting an incipient disagreement into a collaboratively negotiated agreement, which in turn has implications for the maintenance of face (Lerner 1996b).

Moreover, Lerner (1996b:306) notes that the organization of preference is likely to be context-free, is insensitive to variations in settings (e.g. familial, institutional, or medical), and is found even in languages that are structurally distant from English. In this connection, Mori 1999 has demonstrated that the features of preferred and dispreferred format responses identified for English are also broadly found in Japanese in the case of agreements/disagreements with the proffering of opinions. Hayashi (2003:64–71) shows how the projectability of dispreferred actions in Japanese can be utilized to convert them into preferred actions. Likewise, preliminary studies of second assessments, compliment responses, and responses to self-deprecations in Japanese also suggest a striking similarity to the structure of preferred and dispreferred second actions that has been reported for English, though no attempt will be made here to deal systematically with such similarities. Instead, this article specifically addresses how word order and ellipsis may be implicated in the performance of preferred and dispreferred second actions in Japanese.

As noted above, preferred second actions are typically structurally simple, direct, not accompanied by accounts, and delivered early if not in actual overlap with the ending of the first pair part. The available data indicate that these features are maximized in Japanese through ellipsis and/or the deployment of a turn-structure which accords with some version of non-canonical word order – for instance, predicate-first or predicate-only turns.

In the case of requests, one type of regularly occurring response is an early unvarnished acceptance, via a highly elliptical turn-structure consisting solely of a verb of acceptance, sometimes referred to as “nuclear sentences” (Martin 1975:28). This turn-shape can be observed both in ordinary conversation and in institutional contexts when participants perform unequivocal acceptances. In the following fragment, Ken telephones the house of his older brother to say that he left a newly purchased pair of trousers in his brother's room, and asks Emi (brother's wife) to tell him not to wear them:

In formulating a request to Emi to convey a message to her husband not to wear the newly acquired trousers he had forgotten in the latter's room, Ken starts to burst into laughter toward the end of his turn (lines 5–6). Emi shows affiliation by accepting the invitation to laugh (Jefferson 1979, Jefferson et al. 1987) by proffering laugh tokens shortly after Ken's laughter can be heard and continuing with a “smile voice” (line 7). Emi's lexical acceptance begins early, while Ken's laughter is still in progress, and is completed even before Ken has finished laughing. The grammatical structure of Emi's turn consists of a simple verb in the past tense, wakatta: ‘((I)) gotcha’ – that is, with an elliptical subject. No further elaboration or accounting is seen to be necessary, as demonstrated by her next turn (line 8), in which she moves on to another topic.

A similar grammatical construction can be observed in the next instance, from a service encounter. In this telephone call made to a newspaper sales office, the sales clerk is responding to a request from a customer to stop the newspaper while he goes away:

After the customer builds up a formulation of a request to stop the newspaper delivery (lines 3, 5–6, 8–9), the clerk comes in right away to accept the request (line 11), with a turn structure consisting of the receipt token A ‘Oh’ followed by the verb expression wakari mashita ‘((I)) understand’, which is again a nuclear sentence with no expressed subject. In contrast to (11) in which an informal or plain form of the verb was used, a more formal or polite form of verb-suffix is employed in (12), reflecting the politeness requirements of a service encounter. However, the structure of the turn is essentially the same as that of the previous fragment, with an unexpressed subject and the response constructed solely through a verb expression. After the acceptance, no further accounting is done, and the clerk swiftly moves on to the next relevant order of business.

The two examples above represent perhaps the simplest type of affiliative response to requests. In addition to features such as laughter, this is achieved in two ways: first, by minimizing the amount of material in the response through ellipsis and limiting talk to direct, stated compliance; and second, by leaving the subject unexpressed, the recipient can bring the performance of the acceptance even earlier in time, if only by a split second. In other words, ellipsis of all components, with the exception of the explicit articulation of the acceptance, maximizes the implementation of the preferred format.

Sometimes a preferred response to a first part of an adjacency pair involves more structural complexity than a simple nuclear sentence with the articulation of a verb or predicate – for instance, when other constituents such as subject or object are expressed. Even in such instances, participants can nevertheless show affiliation through expediting the production of a preferred action by exploiting a non-canonical word order, in this case by placing the main verb or predicate constituent at the beginning of the turn, followed by a post-predicate addition which provides further elaboration. The addition can consist of almost any constituent, such as an adverb (13), a subject (14), a topic (15), or a non-finite verb (16).

In (13), Mai and Ami, who are sisters-in-law, have been talking about how big their respective baby sons have become. Just before the segment shown, Mai mentioned that her son has grown as big as his older sister, and that he has a large face.

In this excerpt, Ami sums up the discussion by giving her opinion: Yappa otokonoko tte chigau n da ↑ne: ‘After all, boys are different, aren't ((they))?’ In response, Mai produces an upgraded agreement – ‘N: ↑chigau↓ yo = zenzen ‘Yeah, ((they)) are different, completely’ – by positioning the predicate ↑chigau↓ yo ‘((they)) are different’ before the post-predicate adverb zenzen ‘completely’, thereby making use of a non-canonical word order. Mai's turn maximizes affiliation with Ami's opinion not only by starting in overlap with Ami's turn, but also by delivering the predicate at the earliest possible opportunity. Through this turn shape, Mai first registers an unequivocal stand of agreement before proceeding to intensify the agreement with the adverb. The ellipsis of the subject further expedites the issuing of agreement.

The next fragment, the same as (8), is from a conversation among three women in their forties who are commenting that the fashion trends of their youth have come back. Chikako mentioned that her daughter is currently wearing one of the blouses she had kept from when she was young. In line 1, she goes on to add the opinion Ima no katachi to mattaku on'naji ‘((It))apos;s exactly the same shape as the ones in vogue now’. In line 2, Keiko latches on to the end of Chikako's turn, employing a non-canonical turn-design, beginning immediately with the predicate On'naji yo ‘((It))'s the same’ and initially leaving the subject unexpressed. Only after putting on record this definitive agreement does Keiko continue with the post-predicate addition of the subject phrase eri mo ‘the collar too’:

The ordering of the constituents in line 2 appears to have a subtle bearing on the kind of agreement that is being achieved. Owing to the predicate-final orientation in Japanese, the first part of Keiko's turn in line 2, On'naji yo↓ ‘((It))'s the same’, produced in real time, is already hearable as a complete turn in its own right, as also evidenced by the falling intonation as well as by Emiko's entering with a “change-of-state token” (Heritage 1984b) at the end of this segment. So what kind of action is this segment performing? By Keiko's starting out with the nuclear sentence On'naji yo↓ ‘((It))'s the same’ immediately after Chikako voices her opinion, the yet unexpressed subject of this sentence is hearable as the same subject that Chikako used: the shape of the blouse. Thus, the action performed is an unmitigated agreement or endorsement of Chikako's opinion. Only then does Keiko latch on a subject phrase eri mo ‘the collar too’. By placing this phrase after the immediately preceding endorsement, she cites the shape of the collar as an additional point of similarity. Alternatively, if Keiko had employed the canonical word order eri mo on'naji yo ‘the collar is the same shape as well’, this could have been treated as possibly challenging Chikako's opinion, in the sense that it is not just the shape of the blouse but also the shape of the collar that is the same.

A similar action is performed by the selection of a non-canonical word order in the next fragment. Ray and Joe are engaging in a post-mortem of their trip to the beach the previous day, about which they concurred that they got exhausted by leaving for the beach too early in the morning and then coming home prematurely before the temperature rose in the afternoon. After Ray's first assessment of the day,

, which consists of just a predicate component, Joe proffers a second assessment, constructed as a repetition of Ray's turn followed by the addition of a topic, kinoo wa ‘as for yesterday’. Producing the topic as an appendage to the agreement component frames it as a further elaboration of the already performed clear agreement, rather than in any way contentious toward it. Had he started with kinoo wa ‘as for yesterday’, this could potentially be taken as containing a suggestion that there were other days that were not fiascos, or even as a prelude to a disagreement (as will be shown in (20)–(22) in the next section).

The next excerpt exemplifies the post-predicate adjunction of a non-finite verb. Four alumni of an elementary school are having a reunion in a coffee shop. They are all tasting each others' cakes. In the part shown below, Eri is trying out Hana's piece of cake, voicing alarm that it is disintegrating as she takes a morsel. Hana responds by beginning with the articulation of the predicate with an elliptical subject, again moving forward the thrust of the preferred action to the very beginning of the turn:

Instead of proffering the non-finite verb kowashite ‘to break’ before the predicate as in the canonical word order, the ordering in the example has the effect of bringing the articulation of the reassurance itself to the opening of the turn, Ii yo(h) ‘((It))'s OK’. Once this action is done, only then is it followed by a post-predicate addition kowashite ‘to break’, which specifies what kind of activity is ‘OK’ to do.

The use of a non-canonical sentential word order to produce second parts beginning with a predicate followed by a post-predicate addition can be seen as an ingenious operation on the word order for formulating a second action which takes a definitive affiliative stand at the earliest possible opportunity, prior to reinforcing the affiliation with further actions such as upgrading, providing further grounds for affiliating, or specifying the particulars of the affiliation. The permutation amounts to an operation on the internal structure of a turn to reorder the components to augment the preferred status of the action.

Designing a turn in accordance with a non-canonical word order by producing a main clause before a subordinate clause is another way in which affiliation can be maximized by advancing the action of aligning with the first speaker. This resource can be exploited in a way similar to the cases discussed above, except that the main clause is followed by a subordinate clause which elaborates on the nature of an affiliative action. The background of the next fragment is as follows. Mai regularly obtains her eggs through Eri, who buys them from the wholesaler. In the telephone conversation below, Mai had phoned Eri to ask whether the latter had any eggs that day. However, Eri replied that she intended to go the next day to purchase them, but then went ahead to offer to bring a few eggs to tide Mai over until the next order. Mai accepted the offer. In the portion shown below, Mai promises to “pay back” Eri the next time she purchases eggs from the latter: a statement of indebtedness. To this, Eri proffers a preferred format response, which dismisses Mai's indebtedness:

Eri's response is delivered early, in overlap with Mai's articulation of her indebtedness. The first point to note is that Eri's entire turn entails a non-canonical word order by positioning the main clause in front of the subordinate clause. She begins by emphatically delivering the main clause A i:i yo ‘Oh ((it))’s OK’, employing the turn-initial response token A ‘Oh’. According to Heritage 1998, ‘oh’-prefaced responses to inquiry are regularly used to propose that the inquiry is inapposite or unnecessary. In this context, the main clause is therefore being used to perform a highly affiliative action of categorically dismissing Eri's indebtedness as unfounded. Moreover, by designing the main clause with an unexpressed subject, essentially consisting of the nuclear sentence A i:i yo ‘Oh ((it))’s OK’, she expedites an early, unqualified reassurance, as already discussed. Only then does she go on to produce the subordinate clause, kaesa naku tatte: = son'na no ‘if ((you)) don't return such things', which clarifies more specifically that returning the eggs is unnecessary. But note furthermore that the internal structure of the subordinate clause itself follows a non-canonical word order: The verb component kaesa naku tatte: ‘if ((you)) don't return ((it))’ occurs first, followed by the object son'na no ‘such things' as a post-predicate addition. In this way, Eri further expedites her affiliative action clause-internally by first making light of the act of returning the eggs. Finally, she articulates the object son'na no ‘such things’, a deictic expression which devalues the eggs themselves as trifling. This item, moreover, is delivered in a disparaging tone.

To summarize, Eri employs a multi-clausal unit, which is a type of non-canonical word order, by producing the main clause prior to the subordinate clause; the main clause is constructed as a nuclear sentence with only an expressed predicate; and the subordinate clause itself adopts a non-canonical, predicate-initial structure. Taken as a whole, therefore, Eri operates on the word order to configure her turn so that the response is performed in the following sequence: (a) blanket dismissal of indebtedness; (b) specific dismissal of indebtedness; and (c) treating the objects owed as insignificant. The degree of affiliation in Eri's turn is maximized by managing the temporal organization of the response in order to foreground the action of reassuring by emphasizing that the indebtedness is unwarranted, and by defocusing the object owed (see Clancy 1982 on “defocusing”).

It was shown above that the use of ellipsis and the mobilization of non-canonical word order – for instance, by producing the predicate component first or by positioning the main clause before the subordinate clause – are some methods by which participants can design a preferred format response by maximizing affiliation with a first action. It will be shown below that just the reverse strategy is regularly practiced to produce second actions in the dispreferred format.

To recapitulate, dispreferred format actions routinely display one or more of the following features: delay; structural complexity; prefaced by elements projecting their dispreferred status; delivered with disfluencies such as cutoffs, sound-stretches, laugh tokens, or breathiness; accompanied by accounts; and often contain an indirect or mitigated declination component. It turns out that a less elliptical turn-design and the mobilization of a canonical word order (e.g. verb/predicate-final) are typical techniques through which such features may be incorporated in dispreferred format responses in Japanese.

In contrast to preferred format responses, the data indicate that dispreferred format responses are regularly characterized by a turn-shape which shares many features with canonical word order, in which many of the main grammatical constituents are overtly expressed. Highly expressed dispreferred turns are particularly noticeable in institutional settings where a more formal protocol is often adopted. However, it will be shown that this type of turn-structure is also observed in informal conversation when a dispreferred action is being performed.

Excerpt (18) illustrates an instance of a fairly non-elliptical turn used to perform an implicit rejection of an offer, which conforms to the canonical predicate-final orientation. The fragment is from an informal editorial meeting at a voluntary organization, where the members are discussing who should write an article on a questionnaire which has been administered to clients. The members of the meeting include Professor Kawano and Akira, who was a student of the professor more than 10 years previously. Professor Kawano makes an offer to write the article, claiming that it has many similarities to some work that he is familiar with, but the offer is indirectly declined by Akira through an account for the rejection:

In delivering the indirect rejection of the professor's offer to write the article, Akira employs a canonical word order (predicate-final) construction, building his argument bit by bit: through a connective expression eg to (.) ta(.)da(.) ‘Uhm (.) on(.)ly ((that)) (.)’, a topic sensei wa ‘as far as you are concerned’, a noun-modifying clause nanika betsu no koto o kakareru to iu ‘that ((you)) would be writing something else’, a direct object ketsui hyoomei o ‘a declaration of resolve’, an oblique zuibun mae ni ‘some time ago’, finally ending with the verb expression nasareta hazu desu node ‘you are known to have made’. This is close to a model canonical word order design in which the verb component occurs turn-finally, with many of the pre-verbal constituents such as topic, direct object, and adverbial phrase being expressed. Note that although the subject, sensei ‘you’, is omitted, it is already expressed as the topic. The very presence of the main constituents offers a contrast to the much simpler structures examined for preferred format turns. Moreover, the turn begins with a connective, tada ‘only that’, which potentially provides an early indication that a disagreement may be forthcoming through a formulation of some kind of reservation (see Mori 1999 for a treatment of connectives). Other constituents – such as the topic, adverbial, and object – all contribute to the progressive projection and construction of a dispreferred second (Tanaka 1999a).

Although the main constituents are not always expressed, dispreferred turn formats generally tend to have more overtly articulated constituents than preferred formats have. There are several reasons for this. First, in contrast to preferred seconds – where it was shown that speakers display affiliation by bringing forward the verb/predicate to perform the preferred action – a word order of the canonical variety is a resource that Japanese participants can exploit to displace the declination component to the end of a turn. Given that the declination is often explicitly implemented through the articulation of the predicate, this delaying device may be maximized via taking advantage of the predicate-final structure, which enables the insertion of multiple pre-predicate constituents while simultaneously postponing the delivery of the predicate. Excerpt (19), from a telephone call made by a clerk at a newsagent's to an employee (EMPL in the transcript) at the newspaper office on behalf of a customer, is just such an example:

The newsagent's clerk makes an implicit request to see an advertisement contained in an issue of the magazine Kimono Quarterly (lines 1–3 and 9–10). The newspaper office employee starts to construct a rejection of the request by first delaying the response through a pause (line 12), followed by some appositionals delivered with hesitation (line 13), after which she employs further methods in lines 14–18 (encased in boxes). Included are two instances of the adverb chotto ‘sort of’ (lines 15 and 17) and two noun phrases marked by the topic particle wa (lines 16 and 18), both types of which occur extremely frequently in dispreferred format turns, as illustrated by the fact that most other instances of dispreferred turns introduced here are also marked by at least one or the other. These methods gradually build up a dispreferred format response by temporally and incrementally displacing the explicit articulation of the declination component to the end. The declination component itself – carried within the predicate constituent – is ultimately produced in the last stretch of the turn (line 19), in conformity with the canonical word order.

It was argued in an earlier section (see also Tanaka 1999a, chap. 5, and 2001a) that the topic particle and adverbials, among other constituents, play an important role in projecting an upcoming predicate when a turn is being constructed according to the canonical word order. Therefore, in addition to delaying the occurrence of the declination component (or circumventing it altogether), the various components contribute to projecting the dispreferred action. The specific projectability functions of the various aspects of canonical word order, such as the use of the topic particle and adverbials in the production of dispreferred seconds, will be examined next.

In addition to the common delaying devices found in dispreferred responses, such as pauses, disfluencies, cutoffs, prefaces, and repair initiators, the data indicate that informationally redundant topic noun phrases regularly preface declination components in dispreferred seconds when produced in the canonical word order. Consider the following case of a response to a question/request. Hana, who is Mari's sister-in-law, is ringing Mari to ask if she left her jacket at the latter's house when she recently paid a visit:

After Hana asks whether she has left her jacket at Mari's house (line 5), there are two insertion sequences which initially delay the negative answer (lines 6–10). Then Mari starts to formulate a dispreferred response (unexpected answer) in lines 11–12:

<.hh oite inai to omoi masu ne::.> ‘<As for a jacket, .hh ((it))'s not left ((here)) ((I)) don't think.>’. The turn conforms to a canonical predicate-final order, with two components: a topic noun phrase followed by the predicate constituent (see ex. 6). Note first that the declination component (i.e. the predicate constituent) is delayed by beginning the turn with a topic delivered slowly:

‘<As for a jacket,>’. Given that jyambaa ‘jacket’ had already featured three times in the immediately preceding talk, the production of this term at this location is clearly redundant in terms of semantic content. This point is further reinforced by the fact that the use of the topic particle is exceedingly rare in preferred format responses; if it is used at all, it almost always occurs in a post-predicate position (cf. ex. 15). The early production of a topic can therefore be regarded as a double-barreled technique to foreshadow that a dispreferred response may be in the offing as well as to delay the declination component itself. More evidence for this is provided by instances of anticipatory completions triggered by the use of the topic particle, which displays an understanding that the topic presages a disagreement, to be dealt with next.

The following is the same as ex.(6). To repeat, the bride had earlier raised the point that in some weddings, the guests may be given dried bonito and confectionery as gifts to take home. In response, the planner begins to construct a response in line 1:

The planner marks the subject Katsuobushi toka okashi toka ‘things like dried bonito and confectionery’ with the topic particle wa (line 1), which is treated by the groom as foreshadowing a refutation of the bride's implicit suggestion, as demonstrated by the anticipatory completion in line 2. The planner reinforces the groom's interpretation by ratifying his candidate anticipated rejection (line 3).

In the next instance, from the same meeting, the planner raises the issue of what to do about the place cards for the guests (line 1), and proceeds to offer to prepare them in line 2.

In response to the planner's offer, the bride begins in line 3 with the semantically redundant topic,

‘As for the place cards', and goes on to provide the verb expression rejecting the offer, tsukuroo kana to omotteru n desu kedo ‘to make ((them ourselves)) perhaps is what ((I))’m thinking’ (line 4). Immediately after the topic particle can be heard, the groom comes in simultaneously (line 5) to produce a turn with a very similar design, tsukuroo ka to ‘make ((them ourselves)) perhaps’, which jointly completes the bride's turn-beginning (line 3). The precise timing of the groom's entry for accomplishing a similar action demonstrates that he has analyzed the emergent structure (i.e. the topic noun phrase) as projecting not any kind of predicate, but a rejection. The two instances above suggest the integral role played by the topic particle in designing and foreshadowing dispreferred turns.

Another device that may be directed toward delaying a declination component while projecting a forthcoming dispreferred response is the use of adverbials. As detailed elsewhere, adverbials (and especially adverbs) establish a prospective link with a forthcoming predicate when featured in pre-predicate position (i.e. canonical word order), by creating a grammatical slot for the production of a predicate that is semantically and contextually fitted to the adverbial (Tanaka 2001a). In particular, adverbials can be mobilized for projecting a preferred or dispreferred turn. For instance, some adverbs such as nakanaka ‘rather’/‘however hard one might try’/‘contrary to what might be expected’ or moo ‘by now’/‘already’ may vary in valence (e.g. positive vs. negative), and the particular sense in which they are being occasioned is contingent on the sequential location in which they are employed. Observe the following instance:

Iwao asks if there is some water in line 1, which initiates a “pre-sequence” implicating a request. Mari begins to respond with a collocation of two adverbials – Moo anmari: ‘By now, not ve:ry’ (line 2) –suggesting that there was some water before but that there is not much left. Indeed, although moo ‘by now’ can generally be employed to project either a dispreferred or a preferred action, since moo precedes the adverb anmari ‘not very’, which points to a negative answer, the combination of the two adverbs engenders a prospective link with a negative predicate such as nai ‘not exist’. Iwao himself displays such an understanding by producing the predicate expression, moo nai ka- ‘by now, ((there))'s none left?’, thereby filling in the slot created by the adverbs with the item nai ‘not exist’. In other words, the adverbs produced by Mari are sufficient for Iwao to surmise that a possible rejection is intended, although it ultimately turns out not to have been an outright rejection (line 5). As already seen in lines 15 and 17 of ex.(19), of various possible adverbs used to project dispreferred actions, chotto is found in great preponderance, and it seems to serve a function much like the English well, as a marker of a dispreferred status. An instance of chotto for foreshadowing a dispreferred action is also demonstrated in the next subsection.

The final type of turn design to be examined here is the canonical dependent-head word order consisting of the compound turn-constructional structure: a subordinate clause (preliminary component) preceding a main clause (final component). As discussed previously, this canonical word order is one of the structures that participants orient to in order to project the unfolding trajectory of a turn. In particular, the data suggest that this resource is regularly exploited by speakers to strongly foreshadow the dispreferred status of a response. This is achieved by incrementally projecting a dispreferred second part through prefaces or accounts, while simultaneously displacing the declination component to the end of a turn. Likewise, the same resource provides a means for the recipient to track closely the development of a dispreferred response and to collaboratively complete the final “thrust” or declination component in synchrony with the production of the component by the first speaker.

Before introducing the next example, it is necessary to point out a major difference between the structures of compound turn-constructional units in English and Japanese which may potentially bear on the ease with which a declination component may be delayed in the two languages. Recall that a subordinate clause is typically constructed in Japanese through the postpositional attachment of a conjunctive particle such as -tara ‘if-then’ in clause-final position, instead of putting ‘if’ at the beginning of a subordinate clause as in English, and that one particle tara does the work of both ‘if’ and ‘then’ (see Lerner & Takagi 1999). In other words, the employment of a conjunctive particle at the end of a clause defines the just-produced clause as a subordinate clause while simultaneously projecting a main clause. Moreover, even as the latter (main) clause is being produced, another conjunctive particle may be postpositionally attached clause-finally to convert it retroactively into a further subordinate clause (which would project yet another main clause). Since this procedure can be repeated, there is an expanded capacity in Japanese to string together an indefinite number of subordinate clauses in one TCU without passing through a point of possible completion prior to producing the main clause or final component (see Tanaka 1999a, chap. 5). This phenomenon is schematized below (where A through E are subordinate clauses and F is the main clause/final component):

This structural contrast (pre-positioned conditional particles in English versus postpositional conjunctive particles in Japanese) has implications for the concatenation of clauses to form compound TCUs in the two languages. This feature is exemplified in ex. (24), from a telephone conversation between brothers-in-law Taro and Ikuo, who are in a somewhat tense debate about whether they need to pay tax on a plot of land they own. They have just been talking about having received some confusing advice from Mr. Satoo, an advisor at the tax office. In the extract presented here, Taro suggests talking to someone else to get more accurate information, such as Mr. Yuzawa, another employee of the office (lines 1–2). However, Ikuo begins to reject the suggestion (from line 4), saying that Mr. Yuzawa currently does not have time to talk to them. In doing so, he constructs a string of three subordinate clauses A, B, C, each marked by a conjunctive particle at clause-final position (encased in boxes below), as well as utilizing a range of other measures (also highlighted in boxes) to project the dispreferred status of his turn:

The overall structure of Ikuo's response is designed in accordance with canonical word order, through an expanded compound turn-constructional unit, summarized crudely as follows:

followed by:

There are three subordinate clauses and one main clause in this compound TCU. It can be observed that this multi-part turn structure permits the declination component (the main clause in line 15) to be massively delayed within the turn structure, through the production of prefaces and accounts. First, it allows for the construction of a highly complex turn – inter alia, the insertion of an entire series of prefaces both at the beginning of the preliminary components/subordinate clauses (lines 4, 5, 6, and 8) as well as at the beginning of the final component/main clause (line 14). Among other devices, included in the prefaces are the two types of iconic markers of dispreferred status: the topic particle wa occurring twice – A,

: ‘Oh, as for Mr. Yuzawa’ (line 4),

5Also pertinent to projecting a dispreferred second is the fact that Ikuo enters with an ‘oh’-preface, to propose that Taro's suggestion/question is inapposite (Heritage 1998).

‘at the moment’ (line 5); and the adverb chotto ‘a bit’ also featuring twice (in lines 6 and 14). Second, prior to moving on to the declination component itself, the triple subordinate clause structure builds up multiple accounts for why it may not be possible to accept Taro's suggestion to ask for Mr. Yuzawa's advice:

: ‘because ((it))'s May and so since ((it))'s already a time to settle accounts, and so, since ((it))'s a busy time, so you know’ (lines 8–11). In the formulation of a dispreferred second action, the preliminary components (i.e. subordinate clauses) of compound TCU structures such as ‘because X + Y’ or ‘since X + Y’ can serve as vehicles for supplying accounts prior to an explicit declination component. Indeed, Mori (1999:115) reports that the clause-final connective particle kara ‘because’ – which is a somewhat stronger version of ‘because’ than the particles de ‘because’ or te ‘since’ occurring at the ends of the subordinate clauses in this fragment – is regularly employed to “mark the end of utterances delivering an account for their reluctance to fully agree with the prior speaker.”

All these resources are collectively mobilized as parts of the step-by-step formulation of the dispreferred response and for delaying and projecting the declination component. In other words, the turn structure maximizes the predictability of the declination component, permitting Taro to preempt the “thrust” of the rejection. To wit, shortly after the main clause begins and just as Ikuo moves on to the declination component itself, jikan to↑re nai↓ te yu n da yo ‘((he)) says ((he)) can't take the time’ (line 15), Taro simultaneously enters with his rendition of the declination component A dame na no (ka) ‘Oh, so ((he)) can't’. As mentioned previously, Taro's anticipatory completion converts the incipient dispreferred action (rejection of a suggestion) into a preferred one (an agreement). Taro's completion, moreover, does not start at the beginning of the main clause, but with a slight delay. In this connection, Hayashi notes:

When a co-participant chooses to anticipatorily produce the final component of a multi-clausal unit initiated by another participant, the delivery of the final component is regularly delayed – delayed in the sense that the final component is not initiated immediately on completion of the preliminary component. In other words, we recurrently observe a lapse of time, typically in the form of silence and/or some types of “filled pauses,” between the completion of the preliminary component and the initiation of the final component. (2003:81)

The prefaces N, chotto (0.2) gg ano: ‘Mm, a bit (0.2) gg uh:m’ in line 14 serve a further function of providing an opportunity for the joint production of the final declination component by incorporating the typical time-delay antecedent to co-participant completion. Thus, it is not just the compound TCU structure itself that contributes to the projectability of the final declination component in this fragment, but the mass mobilization of an entire arsenal of resources for foreshadowing the thrust of the dispreferred response. In sum, the canonical word order and incremental projectability through topic and conjunctive particles as well as adverbials heighten the projective capacity of a turn-in-progress, so that “as the turn progresses, even if a final predicate has not yet been produced, the ‘cascade effect’ or accumulation of incremental bits of syntactic binomial projections together with other projectability features of the locally emergent talk can reach a kind of ‘threshold level’, thereby improving the visibility of the possible trajectory of the turn-in-progress” (Tanaka 1999a:181).

In the foregoing, it was argued that the canonical word order is ideally structured for the performance of dispreferred format turns, and conversely that a non-canonical word order is fitted to the performance of preferred seconds. However, this does not mean that dispreferred seconds always follow a canonical word order, nor preferred seconds a non-canonical word order. In this section, examples of two types of deviations from the observed patterns will be examined to gain an appreciation of some of the activities that can be accomplished by such an apparent “mismatch.” The first type involves ostensibly preferred responses which are done through a canonical word order, and the second type consists of dispreferred actions adopting a non-canonical word order or ellipsis.

In ex. (25) below, a canonical word order (verb-final) structure is employed to perform a preferred second. Ami has just mentioned that she intends to come to visit Mai.

In line 1, Ami asks for confirmation that it would be convenient for Mai if Ami comes to visit her the following night. Mai responds in the affirmative in line 2. In contrast to the instances of preferred seconds examined previously, Mai's response utilizes a canonical predicate-final word order even though it is ostensibly performing a preferred second of offering confirmation:

There are at least three indicators that Mai's confirmation is being produced and treated as less than forthright, both in the turn itself and in the way the sequence unfolds. First, Mai employs a repair initiator ↑Ashita? ‘Tomorrow?’ at the beginning of the turn, which serves as a forewarning that a dispreferred response may be in store. Second, Mai's response to the request for confirmation does not directly answer the request, but skirts the issue somewhat by shifting the focus of the confirmation from whether it would be all right to claiming that a precondition (that she would be at home) of complying with Ami's request will be met. Third, instead of treating Mai's confirmation as definitive, Ami goes on to request further confirmation in line 3: Iru? ‘((You))’ll be ((there))?’ Next, a short pause ensues (line 4), which spells a possible problem. Then, Mai offers a token confirmation,‘N ‘Yeah’. However, she goes on to produce a change-of-state token Ah ‘Oh’ (see Heritage 1984b), which finally frames what she is about to say as a “sudden remembering” to mark the transition to a more explicit articulation of a dispreferred response.

This example illustrates that when a canonical word order is used to construct a preferred second, it is not seen as affiliative as a nuclear turn or a predicate-initial structure, and may even be treated as a precursor to a dispreferred response. Although it is not possible to elaborate further, the data show that a canonical word order is regularly employed to structure a token preferred response prior to a subsequent dispreferred action, or in making concessions following a disagreement sequence.

In ex. (26), an ostensibly dispreferred action is performed in an elliptical or verb-initial (non-canonical) word order. This combination can be directed toward engaging in activities that go beyond the relatively straightforward disagreements or rejections examined in the previous section.

Ray (Yuko's husband) is calling from a bar where he is socializing with his friends to let Yuko know that he won't be returning home in time for dinner. Prior to the fragment, Ray had been telling Yuko that even though he wasn't feeling well earlier in the day at work, he started feeling much better after sun-bathing on the roof deck during lunch break. At the end of this topic, Yuko teases him by asking him to return early to look after Yori, their daughter (line 1):

In addition to Yuko's teasing voice quality, she employs a playful diminutive suffix hyan (instead of the usual chan) to refer to her daughter and also uses a markedly abrupt request particle ku↑re at the end of her turn to design her utterance as a humorous tease (lines 1–2). To this, Ray responds with a forthright rejection, ↑Ya da yo hhh ‘Don't wanna hhh’ (line 3). Notice that this turn conforms to a predicate-only, nuclear turn structure with an elliptical subject, even though it is apparently doing a rejection of a request. However, there are several features that make it recognizable as non-serious and non-confrontational. First, he mimics the response of a child to a mother, both in terms of the blatant lexical choice Ya da yo and also through his saccharine voice quality, similar to that of a fawning child. Second, his turn ends with laughter particles, which invite Yuko to laugh along with him (see Jefferson 1979). Yuko accepts the invitation to laugh, and likewise treats the entire sequence as a little joke, as evident from the laughter in both lines 4 and 6. In other words, Ray's naked refusal to look after their daughter (by bringing the predicate to the beginning of the turn) can even be heard as affiliative and in tune with Yuko's equally unrealistic request. Third, Ray's rejection is not treated as reproachable or accountable, as evidenced by their shifting to another topic immediately thereafter (line 7). Even though the exchange takes place within the context of a tease, the very fact that the couple permit each other to deviate from conventional conversational rules (such as adopting a preferred format for rejecting a request) paradoxically frames the relationship between Ray and Yuko as one of intimacy, in which such mutual violations of normal etiquette can be tolerated.6

In this connection, Jefferson et al. state: “It is a convention about interaction that frankness, rudeness, crudeness, profanity, obscenity, etc., are indices of relaxed, unguarded, spontaneous; i.e. intimate interaction. That convention may be utilized by participants. That is, the introduction of such talk can be seen as a display that speaker takes it that the current interaction is one in which he may produce such talk; i.e. is informal/intimate” (1987:160).

Although space limitations preclude further discussion, the available data also indicate that preferred seconds may likewise be performed through a canonical word order in joking or teasing activities, and dispreferred seconds may be performed via a non-canonical word order in outright arguments. Even though such instances are somewhat rare in conversational data, “it is deviance from these institutionalized designs [i.e. preferred actions following the dispreferred format and dispreferred actions following the preferred format] which is the inferentially rich, morally accountable, face-threatening and sanctionable form of action” (Heritage 1984a:268; bracketed text added). A more detailed examination of the data is sure to lead to the discovery of other types of marked preferred and dispreferred actions that may be accomplished through deviation from the typical formats.

The discussion above has attempted to demonstrate that word order and ellipsis are vital resources available to Japanese participants for managing the “timing” of social actions in the realization of preferred and dispreferred responses in Japanese interaction. It was shown that clear preferred seconds following a first part of an adjacency pair (e.g. requests, suggestions, invitations, and offers) are regularly accomplished through a non-canonical (e.g. predicate-initial or predicate-only) word order while leaving unexpressed the subject and/or other constituents. By positioning the predicate at the beginning of a turn, speakers are able to register at the earliest possible opportunity their affiliative response to a first action. Ellipsis of main constituents such as the subject and object contributes to the relatively simple, direct, and unmitigated performance of preferred seconds. When such constituents are expressed, they are typically positioned after the production of the predicate, thereby foregrounding the direct affiliative stance.

In contrast, dispreferred seconds were found to be less elliptical and to conform more closely to the predicate-final canonical word order (e.g. SOV). The canonical word order has built-in features fitted to the accomplishment of dispreferred format responses: (i) The postponement of the predicate to the end of the turn displaces the declination component to the terminal boundary of the turn, since the declination component itself is typically carried by the predicate; and (ii) the positioning of other constituents such as subject, object, topic and adverbials prior to the predicate enhances the projectability of the final declination component. As a consequence, co-participants are able to anticipate if not preempt the performance of a dispreferred and sometimes even to render a dispreferred into a preferred action, in the interest of maintaining social solidarity. In other words, there is a profound interactional rationale for employing a turn-design with maximal projectability features (the so-called canonical word order) for the performance of dispreferred seconds. Among other things, the particular utility of adverbials for projecting the trajectory of a turn is exploited by speakers to foreshadow the imminent thrust of a dispreferred turn. Of the various adverbials and other devices, chotto ‘a bit’ and the topic (a noun phrase followed by the topic particle wa) appear to serve as iconic markers foreshadowing a dispreferred action. It was also argued that the employment of the dependent-head canonical word order consisting of a subordinate clause preceding a main clause (as well as the use of multiple subordinate clauses) enables speakers to maximize compliance with the dispreferred format by allowing them to delay the performance of the dispreferred as well as to incorporate a series of prefaces and accounts prior to the articulation of the main clause containing the thrust of the declination. Moreover, the use of postpositional conjunctive particles to link multiple subordinate clauses permits “maximal loading,” so that many prefaces and accounts can be packed into a single TCU without passing through a possible completion point.

The employment of prefaces and accounts, as well as the compound turn-constructional structure, cumulatively contribute to the incremental projectability of the ultimate thrust, and augment the possibilities for collaborative production of the declination component. It can therefore be concluded that word order variability and degree of ellipsis are two of the prominent grammatical practices that can be put into service for either (i) expediting the direct performance of a preferred action or (ii) delaying the performance of a dispreferred action and incrementally projecting the declination component.

It was nonetheless noted that not all dispreferred actions are produced according to a canonical word order, nor are all preferred seconds designed through a non-canonical word order. When a dispreferred response is accomplished via a non-canonical word order, or a preferred second through a canonical word order, they are typically treated as implicating something interactionally less straightforward than just a preferred or dispreferred response – such as teasing or displaying intimacy. This suggests that word order involves normatively accountable features built into the preference structure of Japanese. Speaking generally about preferred and dispreferred formats, Lerner states:

These built-in preferences provide an interactionally relevant, normative structure for determining how to properly respond to a prior action/turn….When a speaker produces (for example) an acceptance to an invitation but does so with hesitation, accounts, or the like, or produces a rejection to an invitation straightaway without such mitigating elements, they are doing more than merely accepting or declining the invitation. Or when a speaker disagrees straightaway with a prior speaker's assessment, their disagreement may be treated as argumentative rather than a difference of opinion. (One common feature of all-out argument seems to be the structuring of disagreement within a preferred turn shape.) (1996b:305)

As indicated at the outset, the notions of canonical word order and ellipsis are analytical constructs employed by linguists as prescriptive descriptions of syntactic structures in Japanese, and there has been a dearth of research on how they may be employed for interactional purposes. To quote Goodwin, this may be due in part to the traditional lack of interest in how the framework of “time, in the form of sequential projectability” forms a central dimension in the construction of turns at talk:

In formal linguistics the inclusion of such a sequential framework in the basic units used to build utterances has been largely ignored. Such neglect may result in large part from the fact that linguistics has typically focused on units no larger than an individual sentence produced by an idealized, isolated speaker. Within this framework issues of social coordination and the necessity of projectability by participants who are not currently speaking do not arise. (2002:S24)

It is precisely a consideration of the role of timing and projectability in the interactive construction and designing of preferred and dispreferred responses that points to a supreme irony: The type of structure that linguists have long considered to be grammatically unmarked (canonical word order) is actually routinely employed to perform the marked social action of performing dispreferred seconds, and the purportedly marked grammatical structures (i.e. non-canonical word order) are typically enlisted for the unmarked social action of producing preferred seconds in Japanese.7

See Levinson (1983:333) for a discussion of linguistic markedness.

Among other things, the findings reported here have some implications for foreign language instruction. Textbook Japanese primarily introduces “non-elliptical” versions of sentences with expressed major constituents (including the topic particle wa), regardless of the sequential environments in which they may be featured. The discovery that such structures are regularly deployed for the performance of dispreferred seconds underlines the importance of close empirical research to situate language use in context. Although this project has dealt with preferred and dispreferred second actions in general, a more careful examination focusing on specific types of adjacency pairs (e.g. assessment–agreement/disagreement; compliment–acceptance/rejection) would be indispensable for refining the initial observations made here. From the perspective of language typology, it would be of interest to extend the investigation begun here to other languages with varying degrees of rigidity and variability in word order.

Preference format of some selected action types (partially adapted from Heritage 1984a:269.

Features of dispreferred format actions (adapted from Levinson 1983:334).